5 minute read

Unemployment in 1921

By Jeremy Knight, Curator, Horsham Museum & Art Gallery

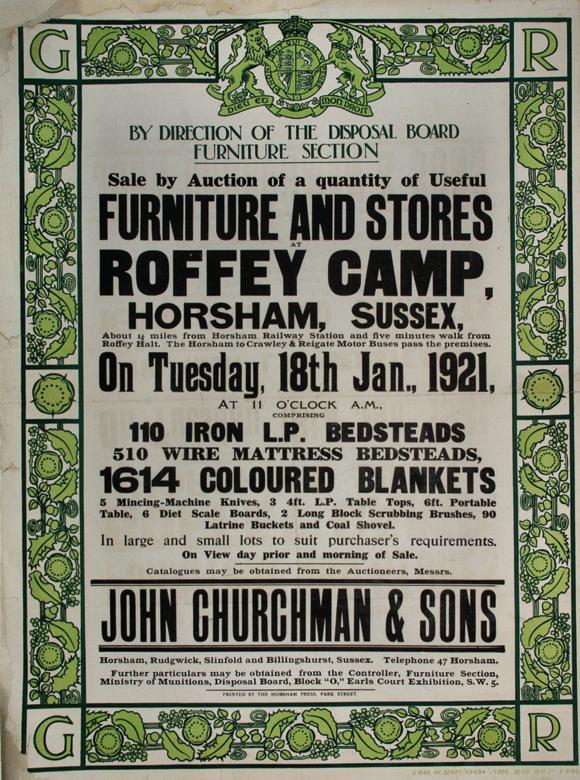

Advertisement

We are currently seeing a rise in unemployment caused by the impact of COVID-19. Interestingly, 100 years ago, the impact of Spanish Flu and the post-war depression had a similar effect. In the 1920s the Urban District Council, which was a lot smaller back then, focused its efforts on what it could do rather than try to address issues beyond its control. Therefore, the Council focused its attention on the unemployed. Until that time there were no real structures or policies in place to deal with the issue of unemployment. If the unemployed were paupers they would have turned to the workhouse, but there was no support for the able bodied looking for work, or for ex-soldiers. To address this the Council set up a committee to look into the issue of unemployment and find work for those affected.

The first meeting of the committee took place on 3 January 1921. At the meeting a letter was read from the Government’s Unemployment Grants Committee Privy Council referring to provision of funds to assisting Local Authorities in creating work that could be done by the unemployed. Unfortunately the town was ill prepared for this and so the matter was adjourned. That didn’t mean that there was no work or schemes available but that the suggestions put forward by the Special Unemployment Committee were too small-scale in approach and direction. For example, one suggested scheme was the cleaning and puddling of the river and stream, as well as clearing the underwood at the farm in High Wood. The cleaning of the river and stream would have taken 3 or 4 men some time with the cost being offset by selling the timber, and clearing the wood could have provided employment for 8 or 10 men for 3 months and considerable revenue would have been raised by sale of underwood. The unemployed would have been paid the same rate as general labourers, or the rate set for farm workers by the Agricultural Board. This programme of works for Horsham’s unemployed would culminate 13 years later with the opening of the town swimming pool. From now on virtually any scheme of work identified by the Council would include the provision of manual labouring work for unemployed people.

This focus on employment carried itself through to the Census of 1921 as reported on in The County Times below:

“The main changes (to the census) are the dropping of questions as to blindness, deafness, dumbness, and lunacy, and the addition of questions relating to employment. In the coming census it will not be enough to state the occupation, but particulars will be required of the kind of work done, of material worked in, and of articles made or

dealt in, and also the place of work. Employees are asked to give the names of their present employers. It also asked whether persons are occupied in either full-time or parttime attendance at an educational institution.”

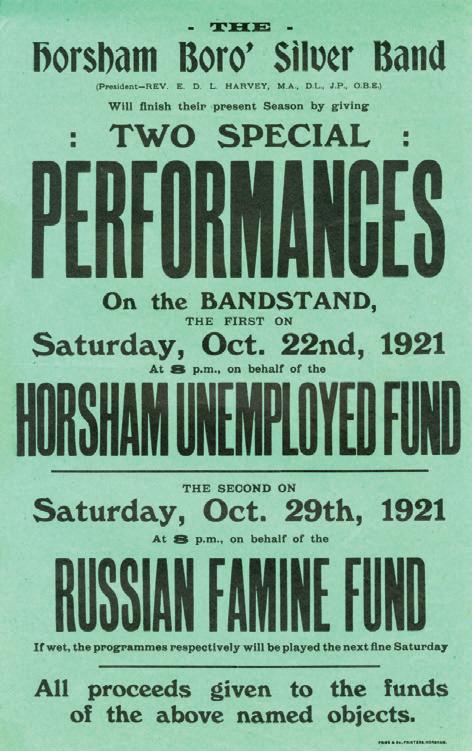

The town suffered a further blow when, in October 1921, it was reported that the Ministry of Health had sent round a circular stating how the government’s financial proposals to reduce unemployment would work. The town had to have a certain number in order to attract the financial support and Horsham, after submitting its application, was told it failed to qualify for a certificate stating that it had “serious unemployment in the urban area”. As a result Horsham had to finance its own unemployment schemes. The town’s charities went to work to support their neighbours. One example was the Borough Band who held a fund raising concert, as shown in the poster from Horsham Museum’s collections. The concert was followed by the Horsham Unemployed Relief Committee’s Flag Day on 5 November. Flag days were a popular form of fund raising. People bought a flag to visibly show support for the cause and contribute to the fund. The newly formed poppy appeal followed the same principle. The town used the very same methods that they had used to raise funds to fight the war to fight unemployment.

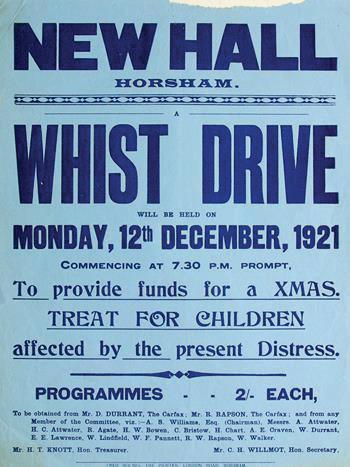

The eventful year of 1921 also saw two events that bookended the remembrance of the war. In January 1921 there was a great sale of military hardware from Roffey Camp, as illustrated in the attached poster. Then, on 11 November 1921, the town held the unveiling of the War Memorial. The monument had split the town over the decision whether to list the names of the fallen. It was unveiled with full military reference and captured on film that was later shown at a local cinema. However, as shown in the third poster, the town were not just concerned about commemorating the Great War. They were also concerned about others in distress, including those affected by the Russian Famine, one of the great disasters caused by natural causes but exacerbated by inept government. We can be confident that the support was ongoing as, a year later, the town would open a famine kitchen in Russia.

The sense of the community and doing things for those less fortunate showed itself again on 12 December when a Whist Drive, arranged by the great and good of the District including Scawen Blunt, was held to raise money for Christmas treats for children in distress. On 17 December another event was arranged for the 86 widows and 146 children of the men who died in the war. Each widow was given team and a jar of honey, and each child received a parcel containing slippers or stockings, chocolate, an orange and a bag of sweets provided by Springfield Park School. These gifts were funded by various donations including £30 11s 9d that raised at a nighttime concert by Horsham Town Band and a Boxing Morning football match.

In 1921 the community effort was all important to support the people of the town. Today there is support through central Government for people in desperate financial straits, but the importance of community is still apparent 100 years on. We may not do Flag Days or Whist Drives but community groups and the local Council are still supporting the vulnerable today. Perhaps the historians in 2121 will be able to show this when they look at us 100 years hence. Jeremy Knight (Pictures courtesy of Horsham Museum & Art Gallery)