IN SEARCH OF ALDUS PIUS MANUTIUS

M M X V I I I

Revised: November 1, 2024

© Damocle Edizioni

Tutti i diritti riservati

Cover: Aldine Device No. 1, first appeared January 1501

ISBN 978-88-943223-2-3

M M X V I I I

Revised: November 1, 2024

© Damocle Edizioni

Tutti i diritti riservati

Cover: Aldine Device No. 1, first appeared January 1501

ISBN 978-88-943223-2-3

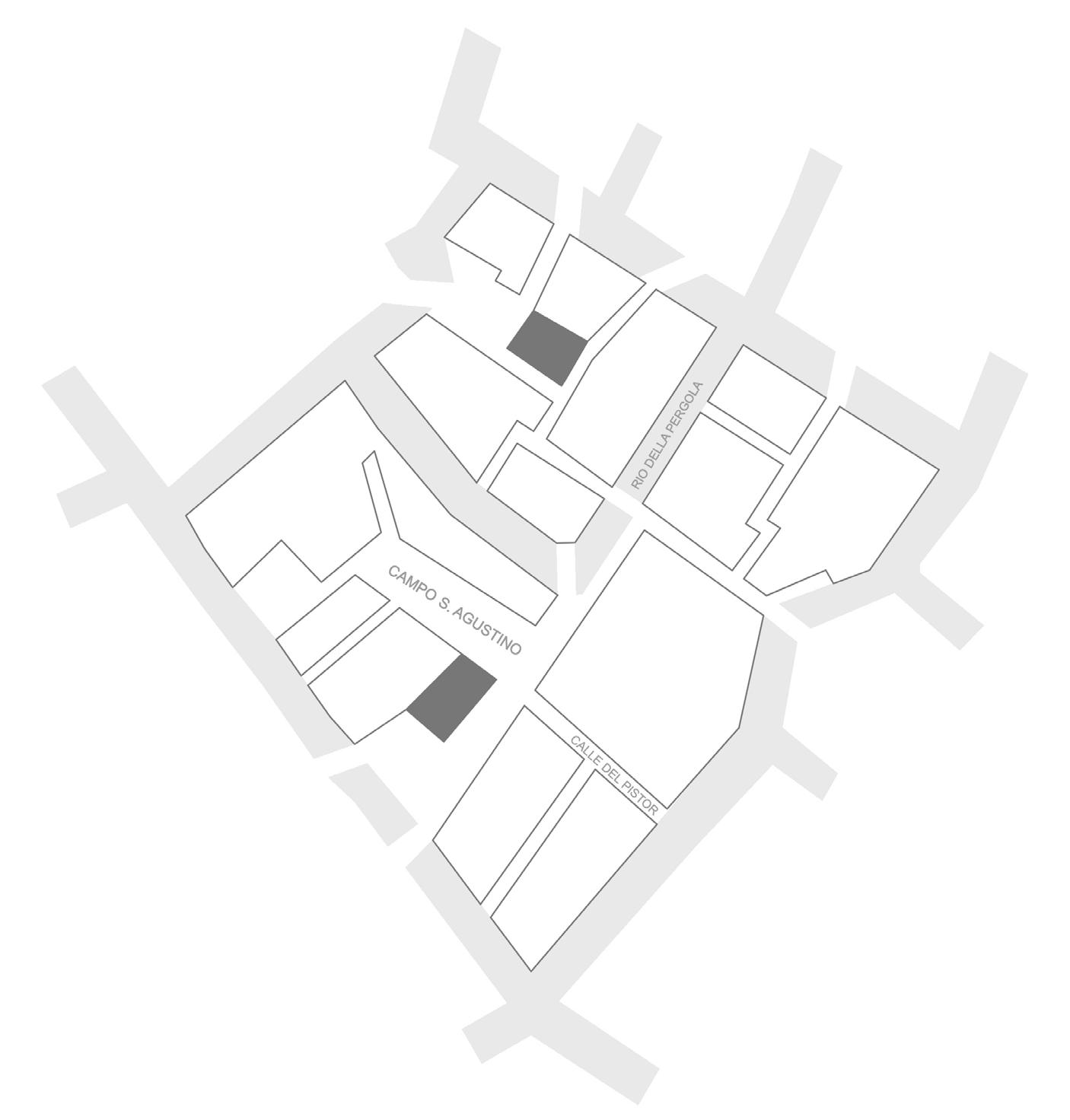

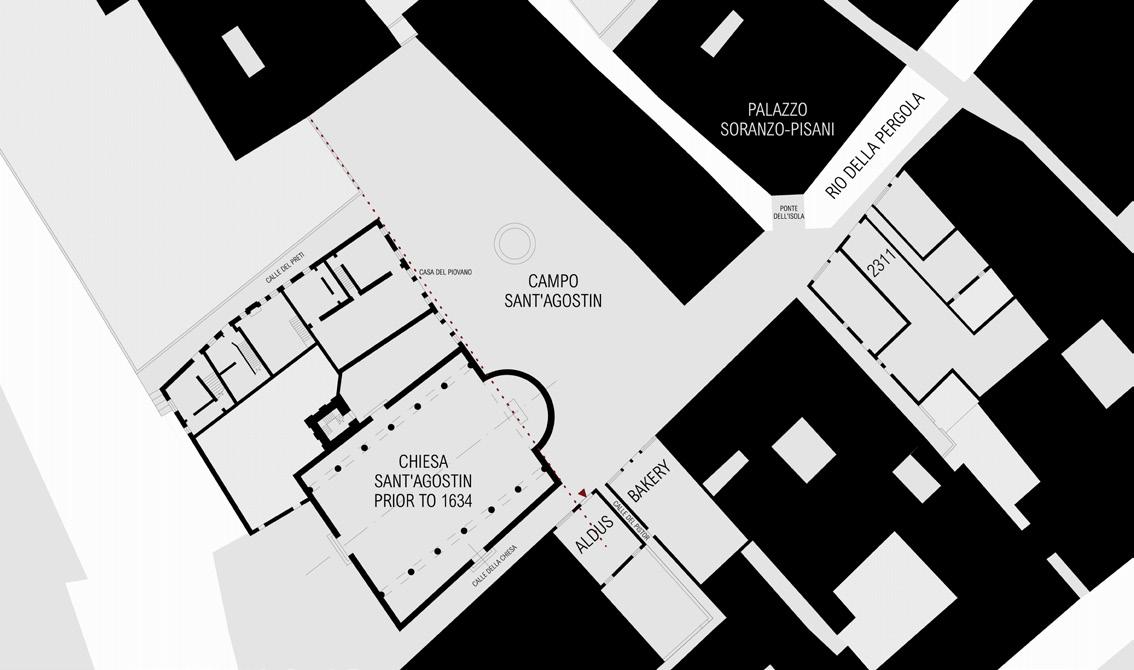

campo Sant’Agostin

Johannes M. P. Knoops, Professor

Fashion Institute of Technology/State University of New York FAAR, BF

2311 refers to civico numero #2311 San Polo on the Rio Terà Secondo, 2343 refers to civico numero #2343 San Polo on the Calle della Chiesa.

Sant’Agostin

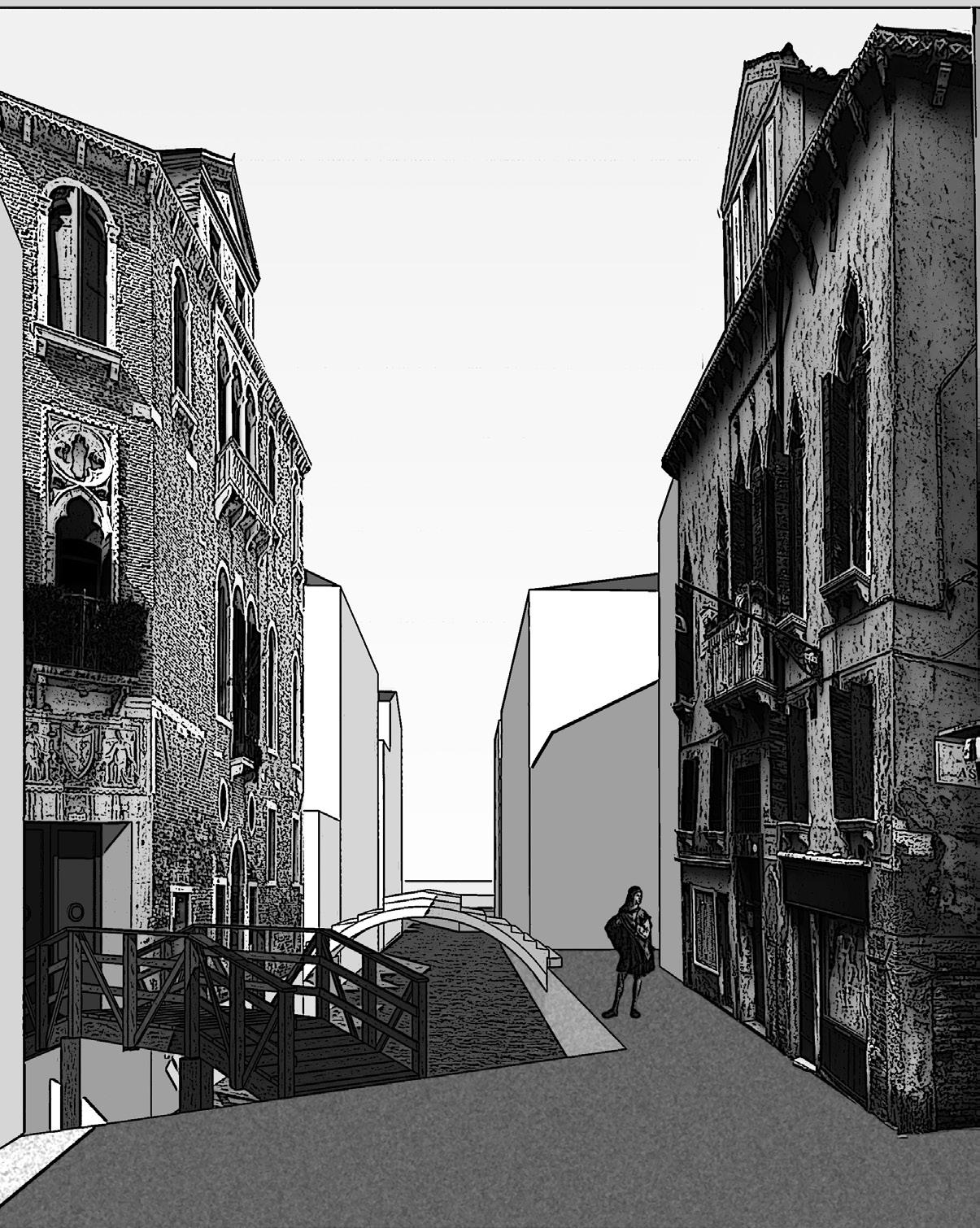

Ponte Natale

The erroneous location of the Aldine Press Palazzo Soranzo-Pisani

The ancient bakery

The true location of the Aldine Press

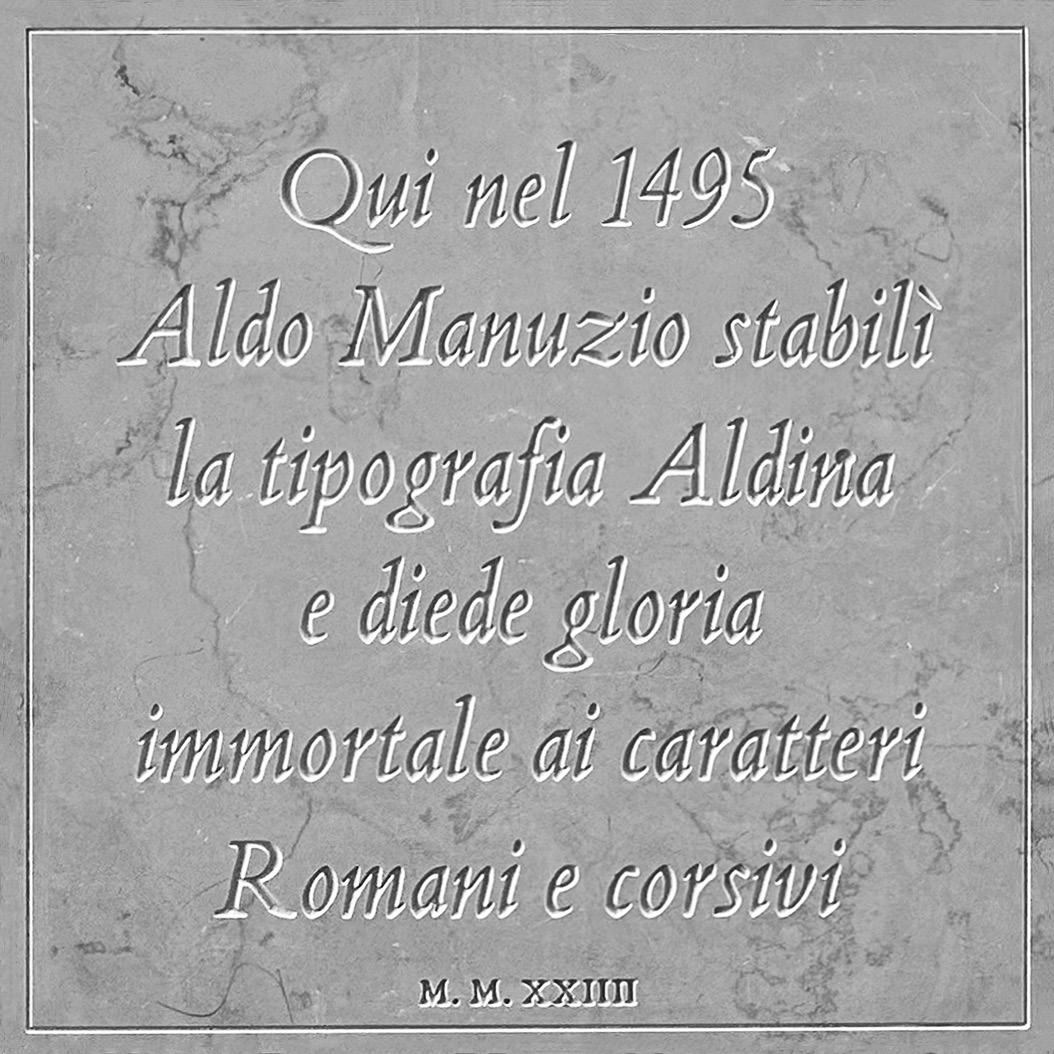

At no. 2311, a few yards along on the right-hand side, stands a small Gothic palace with a pleasant balcony round the three central windows on the second floor. This was the home of one of the great printing presses of the Renaissance.

By the end of the fifteenth century, Venice’s two hundred printers had issued more works than Rome, Florence, and Milan put together. Although the press here was not entirely free, it was at least protected from the worst of the Church’s meddling. Most famous of the Venetian presses was that of Aldus Manutius. Under the imprint of the dolphin and anchor, it quickly became known for its fine editions of the classics.

Ian Littlewood, ALiteraryCompanionToVenice, New York 1995

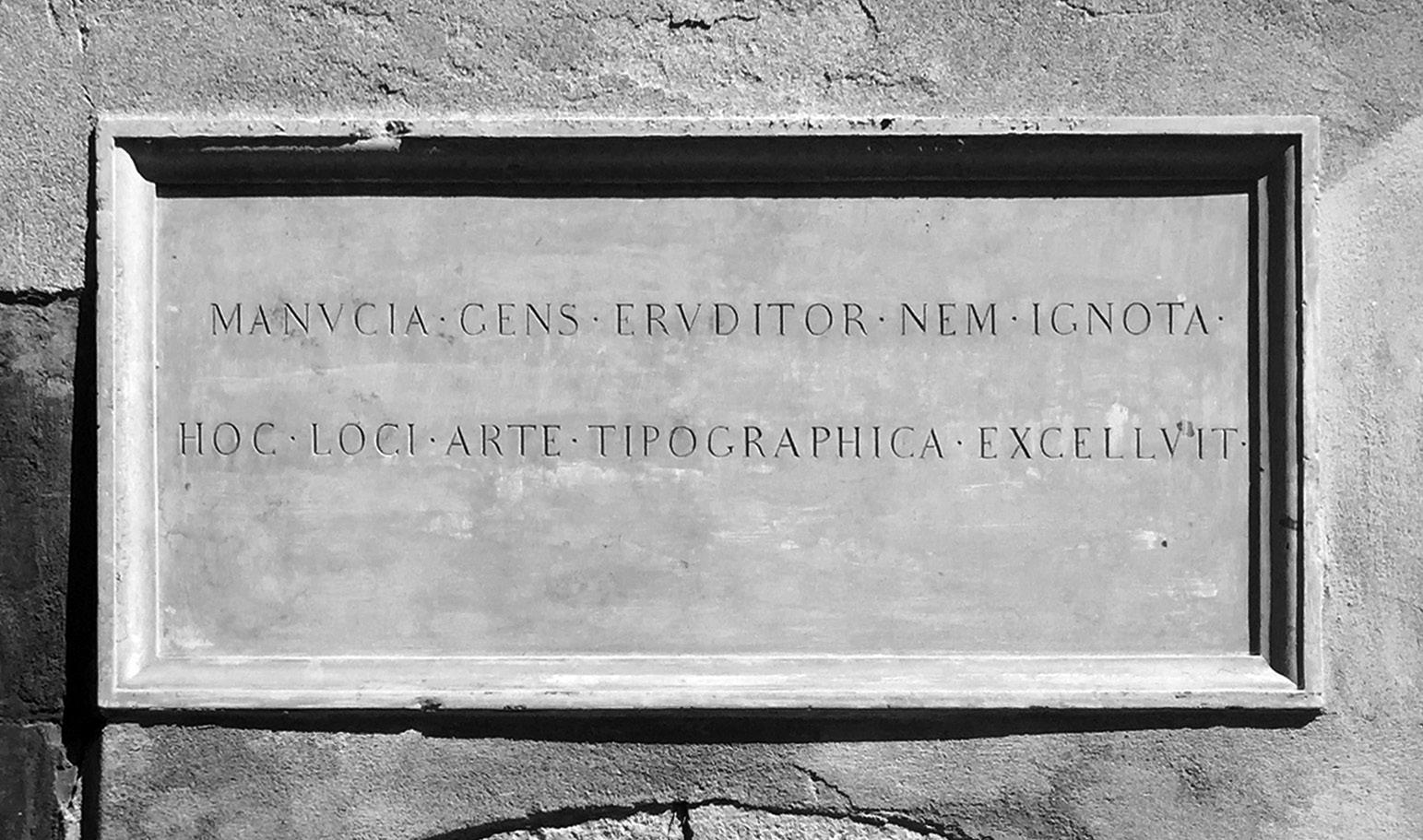

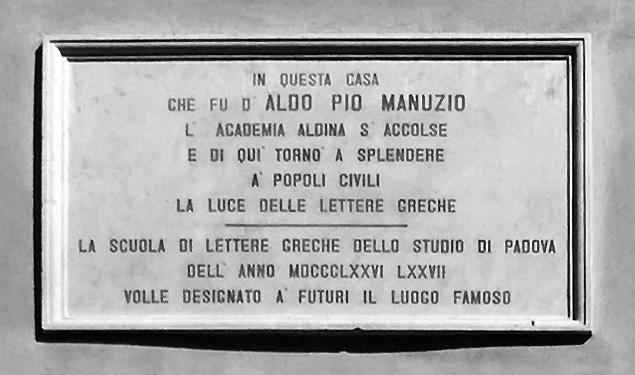

...allorquando nel 1877 gli studenti di lettere greche nello studio di Padova vollero donare a Venezia una nuova lapide in onore del Manuzio, collocossi anche questa, non senza l’intervento di dotti personaggi, vicino a quella dello Zenier, sanzionando così il pristino errore.

Giuseppe Tassini, CuriositàVeneziane, Venezia 1887

1877 plaque placed by students from the School of Greek letters at the University of Padua, class of 1876-77

avendo recapito presso S. Agostino

Alessandro Sarti, Ferrara 1498 March 14

Venetiis, in casa de M. Aldo, apresso santo Agostino dove se stampa

Marcus Musurus at Carpi to John Gregoropoulos (1500) March 14

Venetiis. In casa de messer Aldo, appresso sant’Agostino

Marcus Musurus at Carpi to John Gregoropoulos (1500) April 4

A la stampa de miser Aldo Romano, sul campo de Santo Agustino, accante el Pestore. In Venesia

Zacharias Callierges to John Gregoropoulos (1500) August 22

Venetiis in casa de meesser Aldo, apresso sancto Augustino dove se stampa

Marcus Musurus at Carpi to John Gregoropoulos (1500) September 20

Messire aldo Imprimeur demourant a Venise davant

St. Augustin, ou les bailler en la botique de livres a lenseigne de la tour, pres de pont Rialto

Jean Chapelain at Buda to Aldus (1502) December 19

Venetias a sancto Agostino

Scipione Forteguerri a t Rome to Aldus

1504 December 11

Santo Agostino

Scipione Forteguerri at Rome to Aldus

1505 January 13

Scipione Forteguerri at Rome to Aldus

1505 December 19

All known descriptions of the Aldine Press’s first location in San Polo based on H. George Fletcher III’s NewAldineStudies, San Francisco 1988

The erroneous location 2311

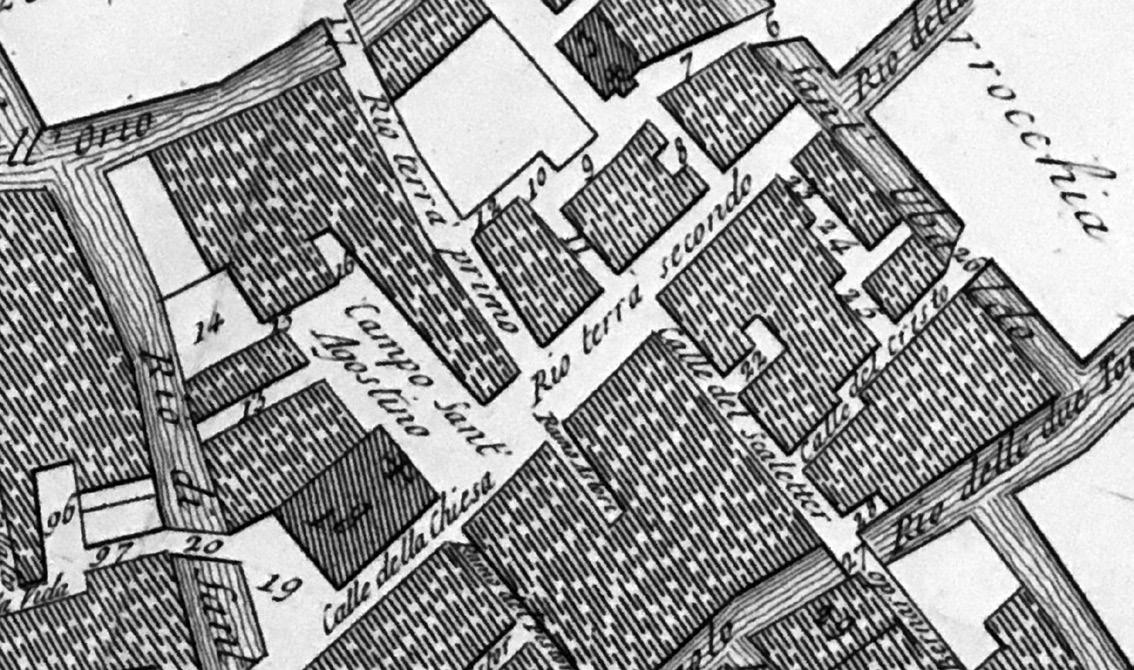

Numerous maps prior to 1821 illustrate how 2311 had been situated on a conspicuous canal, the Rio della Pergola. Since the fondamenta in front of 2311 was so narrow, it would have been impossible not to mention the canal when discussing this location. Prior to 1808, the Rio della Pergola was filled in from Rio di San Giacomo dall’Orio to the corner of the Palazzo Soranzo-Pisani. Then after 1816 the Rio della Pergola had been filled in further to the Ponte Natale, and then for a third and final time from the Ponte Natale to the Rio di San Boldo prior to 1821. So when Abbot Zenier placed his plaque in 1828, the rio fronting 2311 had been turned into a rio terà. The street is now known as Rio Terà Secondo.

Approximately 1798 “Venezia. Ks Lodovico Ughi delint.” by Teodoro Viero. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

1821 from “Iconografia delle trenta Parrocchie di Venezia” by Giovanni Battista Paganuzzi. Cini Foundation.

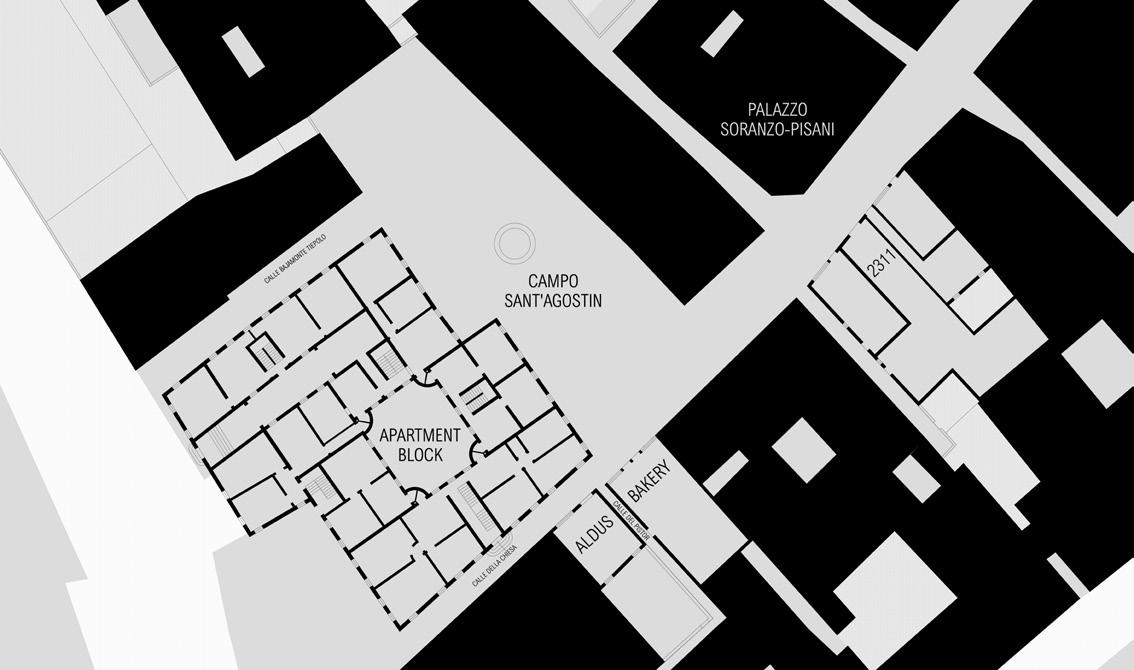

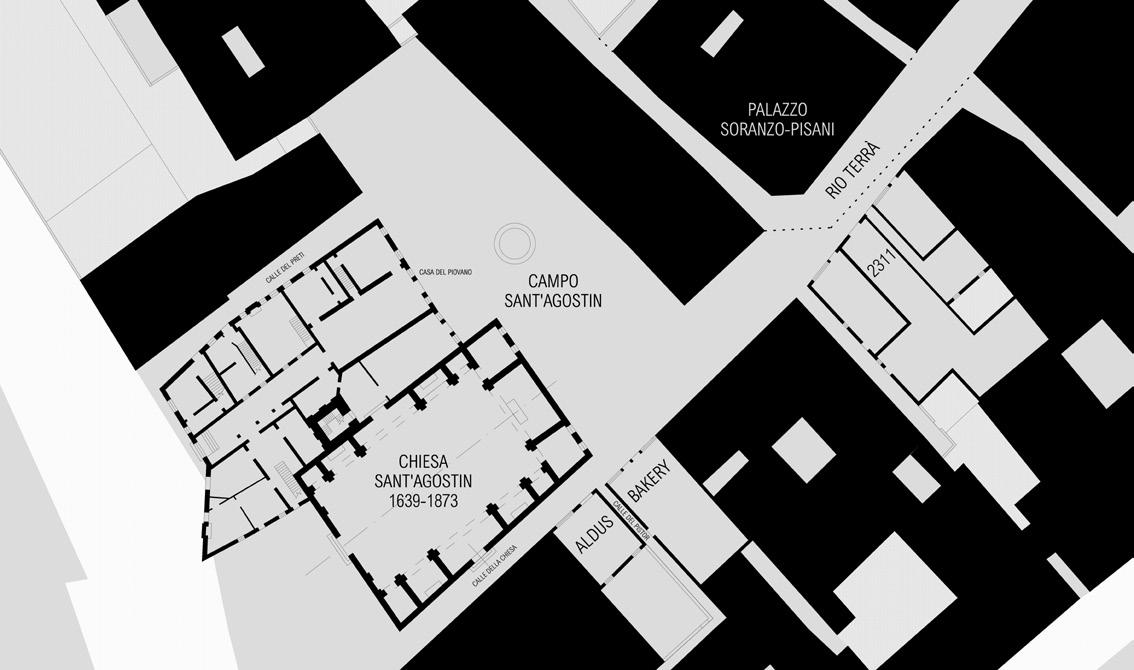

Prior to Aldus’s move to San Paterniano, we have nine written directions from letters addressed to Aldus which clearly describe his stamperia to be on the campo Sant’Agostin. Today 2343 is on the calle della Chiesa facing the campo only tangentially. Currently an apartment building facing 2343 segregates it from being directly on the campo. But back in 1500 things were different, specificly the church.

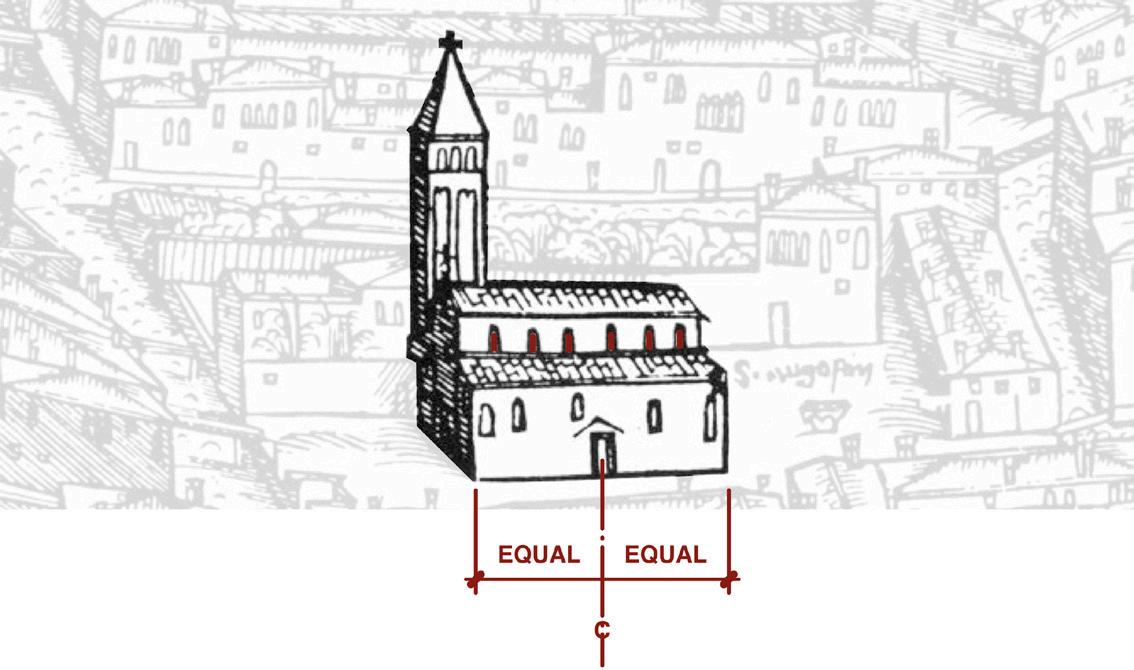

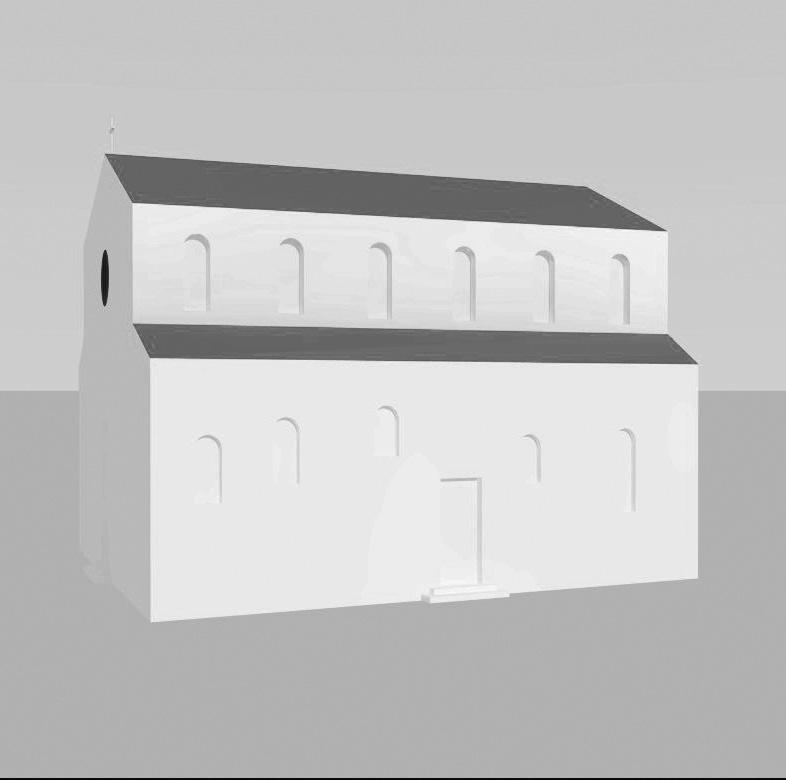

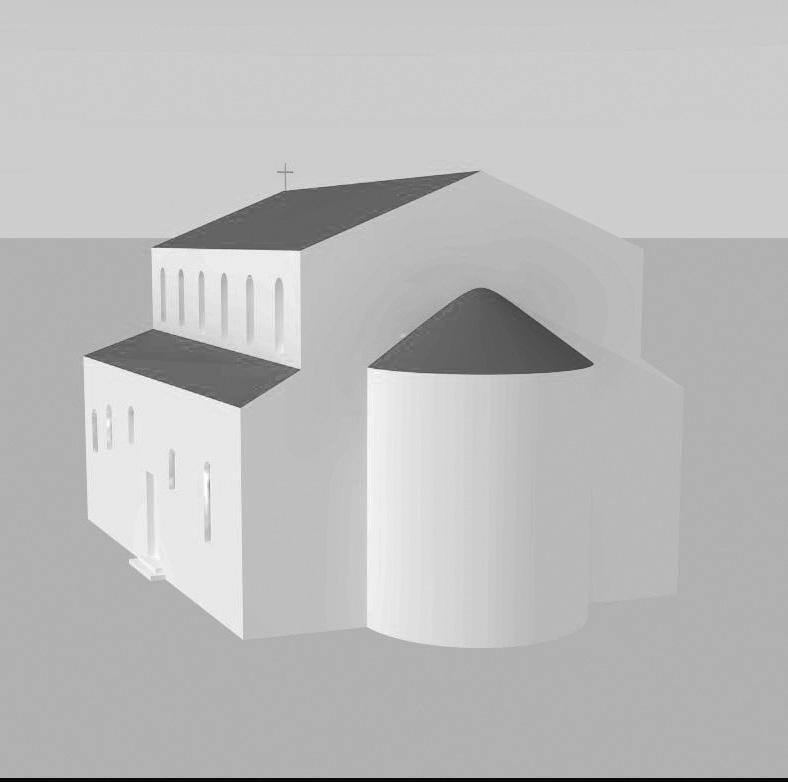

Founded in the late 10th century, the Chiesa Sant’Agostin is first mentioned in a document dated 1081. Destroyed by fire in 1105 and then again 1149, Elena Bassi notes in her article La Chiesa di Sant’AgostinodiVenezia 1992, the church was reconstructed as depicted in Jacopo de’ Barbari’s 1500 view of Venice... facing the Rio di San Polo with its apse letting in light from the campo. Umberto Franzoi and Dina di Stefano in Le Chiese di Venezia 1976, tell us it was a basilica-type church with a nave and two side aisles of Byzantine-Ravenna derivation. Again destroyed by fire in 1634 it was rebuilt by the architect Francesco Contin and finished in 1639. As Bassi points out, Contin most likely kept to the previous church’s overall dimensions. In Delle iscrizioni di Venezia 1824, Emanuele Cicogna describes it as being more akin to the style of architects Bartolomeo Manopola and Baldassare Longhena. In this transformation to the Baroque, we can speculate that the apse was squared off in order to shed its Byzantine form as chapels took the place of aisles.

Much later, after the fall of the Republic, the French government closed numerous churches. The parish of Sant’Agostin was suppressed and incorporated into the parish San Stin in 1808. The building was then closed in 1810 and turned into a mill in 1813. Its valuables were moved and auctioned off, including many paintings, statues and marbles. The building survived and under the second Austrian

domination served as a storage facility for salvaged building materials until 1839, and then finally for storing timber until 1872. The building suffered from extreme neglect and in 1867, shortly after the Austrians departed, the MunicipiodiVenezia determined that it was best to demolish the church along with its bell tower and consturct workers housing. As share holders, the Sindaco (Mayor), the Prefetto (Prefect) and a two Assessore (Councilors) personally profited. The church was demolished in 1873 and the construction of the new apartments finished 18 months later.

1871 document indicating the demolition of the church (solid black) and the construction of the new apartment block, Archivo di Stato di Venezia, published by Adolfo Bernardello 1992

Francesco Contin’s 1639 church based on the 1871 construction document

The centered side door and the six column bays conform to de’ Barbari’s depiction in 1500

Approximating de’ Barbari’s perspective we can note that a Byzantine apse would not be visible in his view

Using the overall dimensions of Contin’s floor plan and his column lines, a Byzantine basilica apse and aisles are substituted

Here the apse projects into the campo, as is the norm for so many churches in Venice, we now see that the stamperia of Aldus Manutius was directly on the campo as described in the contemporaneous letters

E poiché nella soprascritta della lettera del Calergi leggonsi quelle due parole: el pestore, precedute da altra parola, che, non potendosi forse rilevare nel manoscritto, venne sostituita da puntini, ma che potrebbe essere stata un di sopra, oppure un presso, le lapidi suindicate si trasferiscano sopra, o vicino la pistoria, che appunto è aperta in quel sito, e la cui esistenza è tanto antica da trovarsi fino nel catasto del 1661 una prossima strada contraddistinta, al pari di adesso, col nome di Ramo del Pistor.

Giuseppe Tassini, CuriositàVeneziane, Venezia 1887

Il ch. sig abate don Vincenzo Zenier rettore della chiesa di s. Tommaso Apostolo di Venezia, il quale, come abbiam detto altra volta, va dissotterando la memoria de’ più illustri nostri cittadini, onorandola di analoghe inscrizioni, ha fatto porre nel maggio 1828 la presente lapide poco lungi dal campo di s. Agostino su una vecchia casa segnata col num. 2013 .

Che Aldo Manuzio il Vecchio avesse la sua stamperia in questa contrada, non v’ è dubbio; che poi questa propriamente al n 2013 sia la casa ove l’aveva, come sembra che indichino le parole HOC LOCI, io non posso affermarlo che cou autorità stessa di chi fece porre l’epigrafe, il quale avrà certissimi documenti per tenere che quella, e non altra, in questa contrada è la casa dove la Manvccia Genie, o a più propriamente parlare aldo il Vecchio imprimeva . Che se poi l’HOC LOCI vuol significare in questo contorno, allora non v’ è più dubbio sulla verità della cosa.

Del resto vedremo nei seguenti cenni biografici sugli Aldi, che Aldo Manuccio il vecchio riceveva lettere da Marco Musuro colla direzione seguente: appresso sancto Augustin dove se stampa. Anche Apostolo Zeno in una lettera al Fontanini in data 26 marzo 1735 confermava che Aldo vecchio stava di casa a s. Agostino (Lett. vol. V. 100).

Emmanuele Antonio Cigogna, Dellainscrizionivenezianeraccolte edillustrate, Venezia 1830

Qui pero noteremo col Cicogna, sapersi di certo che Aldo Manuzio il vecchio teneva la propria stamperia a S. Agostino

Giuseppe Tassini, CuriositàVeneziane, Venezia 1863

Ecco dunque provato che essa Stamperia non esisteva ove scorgesi l’epigrafe, ma bensì in Campo di S. Agostino

Giuseppe Tassini, CuriositàVeneziane, Venezia 1887

...e, in generale, per tutti gli altri indirizzi è indubitato che la casa stave in angolo tra il campo Sant’ Agostino e la via che è tuttora detta “Calle del Pistore;” a quivi appunto tuttavia sorge una casa, segnata col numero 2343, già 2038, che conserva, massime nella porta, il carattere architettonica del tempo, e che tuttavia ha dirimpetto una bottega di pistore o fornaio. E questa senza dubbio è la casa che Aldo abitò, la casa dov’ egli esercitò la tipografia insino ai primi anni del secolo XVI, e che fu per alcun tempo la sede dell’Accademia fondata da lui.

Carlo Castellani, La stampainVeneziadallasuaorigineallamortediAldo Manuziosenior, Venezia 1889

…at this time he was probably living at St. Agostino, not in the house which at present bears the tablet recording his residence there, but in one of the small houses in the Calle del Pistor, which opens on to the Campo St. Agostino

Horatio F. Brown, TheVenetianPrintingPress, London & New York 1891

... la struttura in piedi all’angolo del Campo di San Agostin, la Calle del Pistor e la Calle della Chiesa, con numero civico 2343

Ester Pastorello, Di Aldo Pio Manuzio: Testimonianze e Documenti, Firenze 1965

…there is convincing evidence it is on the campo itself

Sir John Julius Norwich, AHistoryof Venice, London 1982

The Thermae of Aldus the Roman? The house at c.n. 2343

H. George Fletcher III, New AldineStudies, San Francisco 1988

Nel Calle della Chiesa avava tenuto per anni la sua stamperia

Aldo Manuzio il vecchio

Elena Bassi, LaChiesadiSant’AgostinodiVenezia, Venice 1992

It was located on the square at Sant’ Agostino, at the corner of the Calle del Pistor. If this was the structure at San Polo 2343, it still may be viewed

H. George Fletcher III, Inpraiseof AldusManutius, New York 1995

Guidebooks cite 2311 as the site of the Aldine Press, but no historian has ever defended it with any evidence other than the existence of the two plaques.

By the time Abbot Vincenzo Zenier placed his plaque in 1828, it was over 320 years since the Aldine Press had moved to San Paternian in 1506. The Abbot was not an art historian, but he was immensely proud of his city and ardently commemorated numerous locations such as the sites of Antonio Canova, Carlo Goldini, Marco Polo, etc. 2311’s frontage is wide and its entry quite grand. On its high pianonobile, there are beautiful Gothic lancet arch windows and a balcony. Although the details at 2343 are characteristic of the 15th century, by comparison it has little ornament. In hindsight the Abbot chose a more noble-looking structure, rather than the more likely commercial structure.

2311 now has shops at the ground level and apartments above

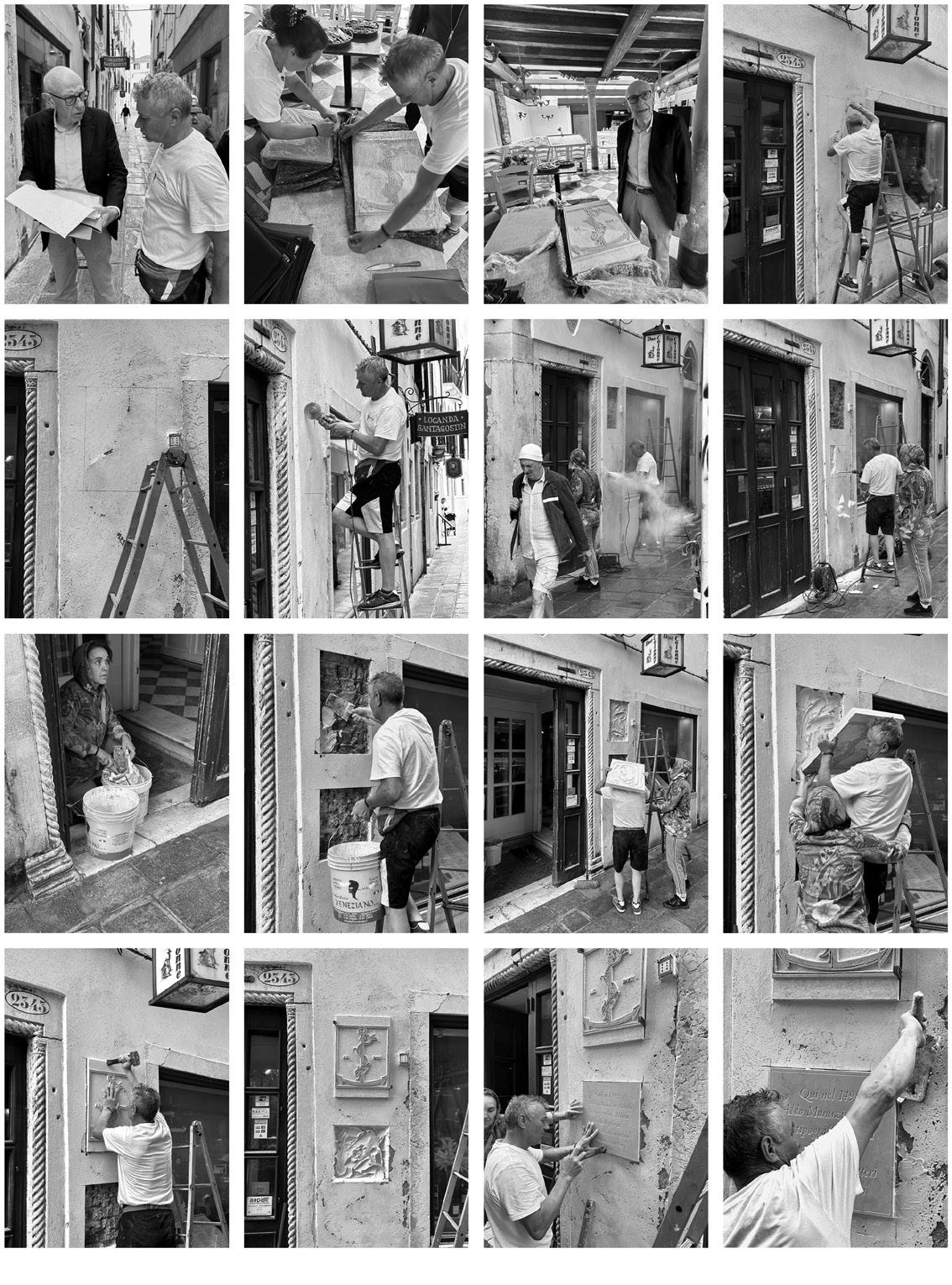

2343 now has the restaruant Due Colonne at the ground level and the Locanda Sant’Agostin above

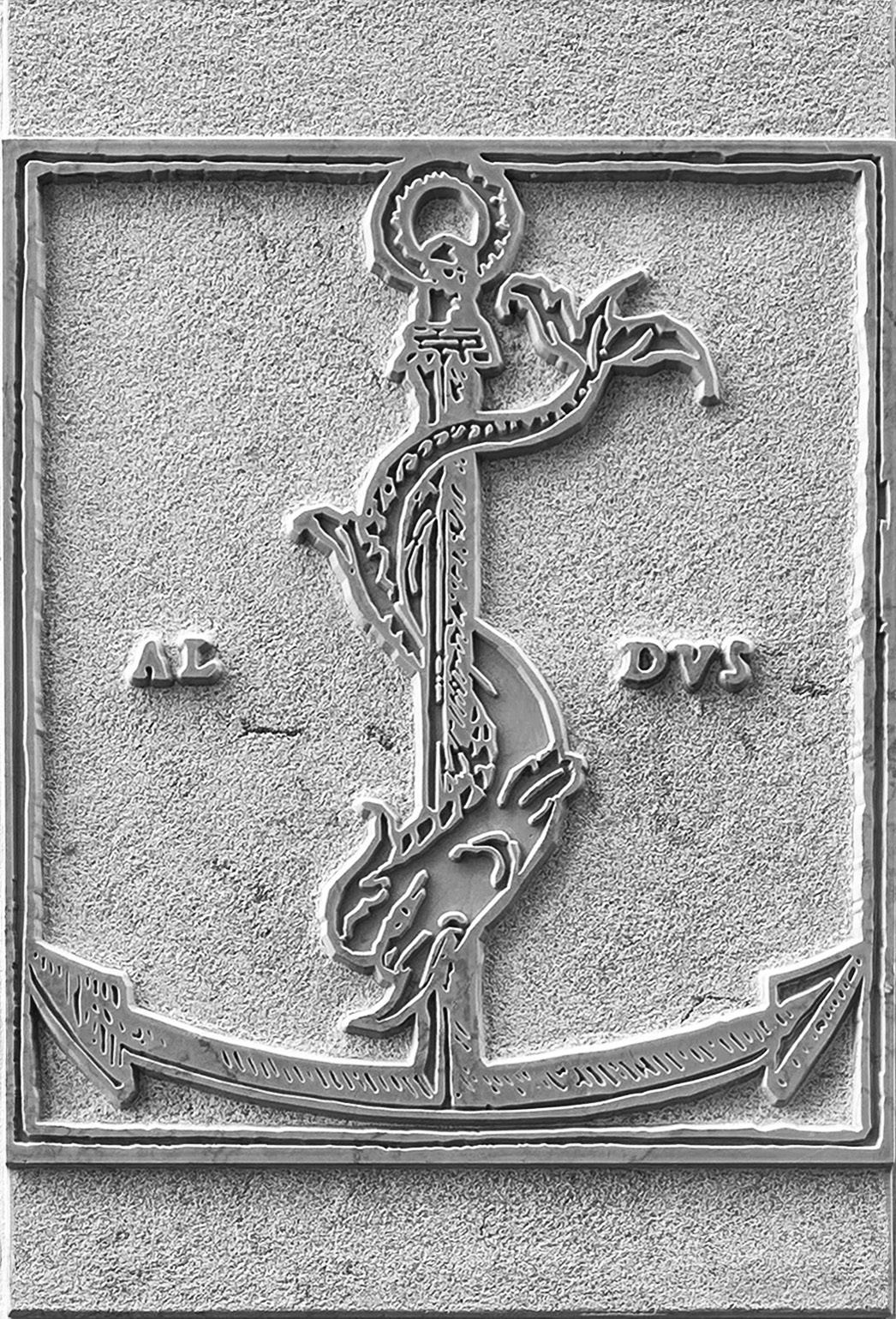

If this building were home to the Aldine Press, its stemma would have most likely been present. Having taken the anchor and dolphin from an ancient coin, Aldus had given the emblem of his Aldine Press much consideration. When Aldus moved his press to San Paternian in 1506 upon his marriage to Torresani, one can imagine that Aldus himself desired its removal to avoid any confusion with his new location. In fact, we know that shortly after his death in 1515, his father-in-law sold books of the Aldine Press “At the Sign of the Anchor” as described in a letter from John Watson at Cambridge to Erasmus 1516 ca. August 13.

The Aldine anchor is perhaps the most celebrated of all printers’ marks. It is singularly graceful in design, eminently characteristic of the distinguished scholar who first adopted it, and is affixed to a series of works, which contributed more than those of any single printer or family of printers to the progress of learning and literature in Europe.

R. C. Christie, SelectedEssaysandPapersof RichardCopley Christie, London 1902

Note: Early in his life, Aldus tutored Princes Alberto III and Leonello Pio, sons of the Duke of Carpi. Alberto and Aldus formed a lifelong friendship, where Alberto assisted in funding the start up of the Aldine Press. Though Aldus was not born of noble lineage, he was adopted by AlbertusPiusdeCarpi, hence Aldus adopted the name Pius. By implication, this may have permitted him the right to royal heraldry.

June 3, 2024

June 5, 2024

Jennifer Schuessler

H. George Fletcher III

Henry Martin

The Emily Harvey Foundation

The Cini Foundation

The Fashion Institute of Technology / SUNY

Sandro Berra

Alessandro Marzo Magno

Philip Tabor

Gillian Crampton Smith

Ilenia Maschietto

Andrea Bizio Gradenigo “Giandri”

Tiziana Plebani

Pierpaolo Pregnolato

www.insearchofaldus.org www.knoops.us