Metamorphosis

Mission Statement

The magazine provides Upper School students with the ability to share their written, visual, and auditory work with the community at large. We hope to inspire and motivate student artists to create, and we aim to celebrate a broad, diverse range of work in each edition of Pub.

Metamorphosis Pub: 2023 Edition Springside Chestnut Hill Academy 500 W. Willow Grove Avenue Philadelphia, PA 19118 sites.google.com/sch.org/pub pub@sch.org

A Letter from the Editors

Dear Readers,

When deciding our theme for this year’s issue of PUB, we chose the theme of metamorphosis because it represents growth, development through change, and an intrinsic connection to the natural world.

Metamorphosis describes the transformation from one thing to something else completely different; the high school experience is reminiscent of this transformation. You enter high school as a young and impressionable caterpillar and leave as a butterfly, ready to take flight and experience the real world. We wanted to capture the idea of this fundamental growth with the written, visual, and audio pieces published in this year’s issue of PUB.

This year, we had more submissions than ever before, so we want to thank you, the Upper School community, for your creativity and vulnerability in sharing your work for publication. As editors, we love the process of fitting these pieces together and creating something greater to share with the world.

Enjoy! Warmly, Your Editors-in-Chief Table of Contents Written Works Escaped by Sofia Forchetti ..................................................................................... 6 Hidden Bakery by Avi Oliver ................................................................................... 8 Steam by Cameron Harrop ..................................................................................... 9 Man of the Summer by Georgia Barrick .......................................................... 10 The Plane with No Destination by Tara Benning* 12 Gifted Student by Lauren Wilson ....................................................................... 16 Cheating Fire by Griffy Whitman* ...................................................................... 18 Robbed by Anonymous .......................................................................................... 24 You Are What You Eat: A Film by Hans Bode ................................................. 25 A Childish Linger by Ava Szalay 26 Artist Profile: Matt Rizzo ‘24 ................................................................................ 28 i carry your heart with me A Song by Sarah Shoff ...................................... 40 4

*All works labeled with an asterisk won awards at the Scholastic Writing Contest

The Aftermath of Trauma by Gabby Adams .................................................. 42 The Mirror by Anonymous ................................................................................... 43 Spotlight by Agharese Olagunju-McWilliams ................................................ 46 Dad by Mia Santiago ............................................................................................... 47 How to Be a Perfect Daughter by Brielle Attanasio ..................................... 48 Departure by Julien Friedland* .......................................................................... 49 The Fire of Audacity by Griffy Whitman 51 Who am I? by Madeline Bell ................................................................................. 52 From Healing to Healed by Sofia Murray ........................................................ 53 The Golden Haired Girl by Helena Fournaris ................................................. 52 Vocabvore’s Dilemma by Chad Cai .................................................................... 56 Implacable by Kaliyani Wardlaw 59 Possession is Nine-Tenths of the Law by Sage Palmer ............................... 60 The Guys* by Emma Ludwikowski ..................................................................... 61 One Small Horse’s Escapade into Flight* by Naomi Becker ...................... 68 Visual Art Medusa by Cooper Bode ................................................................................. Cover Flowing Stream by Alexandra Cross ................................................... 2-3, 70-71 Metamorphosis Sketches by Cooper Bode ................... 4, 21, 42, Back Cover Forest Friend by Aanika Bhatt ............................................................................... 7 Terrapin Station by Cooper Bode 8 Age by Maia Collins .................................................................................................. 11 Drómos by Nelly Forrest ........................................................................................ 15 Bob Dylan Portrait by Georgia Barrick .............................................................. 17 The Complexity of Pigmented Vision by Leah Schnee ................................. 22 All-Seeing Hand by Katharine Rossman 23 Untitled by Annie Gu ............................................................................................... 24 You Are What You Eat: A Film by Hans Bode ................................................. 25 Untitled Girl by Baylin Manusov ......................................................................... 27 Artist at Work by Hirmand Azimi ...................................................................... 29 Cambiare by Hirmand Azimi ............................................................................... 29 Paintings by Matt Rizzo .................................................................................. 30-35 Collage by Jacob Becker ........................................................................................ 41 Glass Box by Georgia Barrick 45 Skull by Cooper Bode ............................................................................................. 46 Volcano by Griffy Whitman .................................................................................. 51 Second Untitled Girl by Baylin Manusov ......................................................... 55 Wedding Day by Nelly Forrest ........................................................................... 58 Mutual Gaze by Nelly Forrest 60 Nike: The Goddess of Victory by Nelly Forrest ............................................... 67 Pastoral by Cooper Bode ...................................................................................... 69

5

Escaped

Sophia Forchetti ‘23

she escaped to the cave everyday. the cave that no one knew about but her. alone she sat alone the rivers of the sorrowed and the damned flew from her eyes the water planted seeds she watched turn into flowers the weeds grew too tall thorns escaped and blinded her. she bled and she cried help anyone ? no a n s w e r maybe becauseshewas

Alone 6

7

Aanika Bhatt ‘24 | Forest Friend | Photograph

Hidden Bakery

Avi Oliver ‘25

i never realized you were there the ominous feeling, meeting you.

you seemed to interest me. i was ready to show others, your humble appearance always were and always will be, a mystery to me

walking through the busy streets of Chestnut Hill, into the quiet alley

i saw you, standing there waiting for me to come join you, for a cup of tea.

i haven’t spoken to you for a while so i planned to visit walking through the quiet streets, into the even quieter alley and then you were gone.

8

Cooper Bode ‘25 | TerrapinStation | Pen

Steam

Cameron Harrop ‘24

I turned off the water, pulled the curtain back, and stepped out of the shower. My hot wrinkled feet touched the tiled floor and I recoiled from the sudden coldness. Hesitantly, I tiptoed onto the frigid floor, trying not to slip, and silently cursed my dad for washing the floor mat and not putting it back. I glanced up at my indiscernible reflection in the fogged over mirror. The hot steam in the small space was almost suffocating and without clarity, in the mirror, the room almost shrunk in size. As the cold sunk into my toes I moved carefully across the small bathroom to the door where two vaguely damp towels were hung. I grabbed the first one and threw it down so I didn’t have to worry about slipping on the now-soaking, still frigid floor. The other I used to dry myself off and wrap around my waist. Waddling across the floor, dragging the towel with my feet to shield them from the cold, I made my way toward the mirror.

Using my right hand, I swiped across the glass to clear enough mist so I could see my own reflection and confirm my identity as the half-asleep person staring back at me. Distantly through the hot steam, I heard someone trudging up the stairs. Ignoring the distraction from the stairwell, I bent my knees so my hair was perfectly positioned in the small clear space on the mirror. I grabbed my black hair brush and was sorting out the steaming hot web of tangled hair on my head when I heard a knock on the door. Confused and mildly annoyed at someone knocking when I clearly was using the bathroom, I responded hotly with a hasty, “Yes?”. No response came, and the steam slowed its loose dance around the room as if it too were waiting for an answer. A moment later, another knock. The steam settled fully in the air, stopping its dance in the same way nature stops its symphony before a storm.

I made sure my towel was wrapped tightly around my waist before opening the door a crack. The steam flowed slowly out like soldiers on a death march and through the mist, I saw my mom standing expressionless on the other side of the door. I stared at her and for just a moment, so short I could’ve imagined it, she stood there and held a blank face. It could’ve been the solemn steamy haze playing tricks on my eyes but for a moment, everything was fine. Then in the same way a wine glass can shatter when a note is sung just right, I found her eyes through the fog and hit that perfect note. I watched as her face shattered into a million pieces that all fell lost into the mist and I knew what had happened without asking. She pulled me into a wet embrace and cried. I knew no words would help so I did the only thing I could and simply hugged her back as the steam resumed its stifling dance through the air around us.

9

Man of the Summer

Georgia Barrick ‘25

When my mother plans vacations to foreign countries, she never settles for a cookie-cutter, touristy trip. So, when she needed somewhere to stay with me and my sister in Portugal, she looked through a British website that was found in an old book she had. I’m sure it was intimidating for my mother, being alone with my sister and me in Portugal, and the owner of the residence we stayed at, an old fat man called Jean Jacques surely didn’t make it any easier for her. He was a hairy Belgian man with a strong accent who wobbled his way around the farm, yelling things at my mother from time to time. “Yankee Mama!”, he’d call and ask her quite often if she wanted to get dinner with him. She always declined.

This was the second year we stayed at Jean Jacques’ residence, yet it still took us hours to find the way from the airport. When we finally arrived, our car was covered in dusty dirt from the road. The drive was worth it, though, because the residence was beautiful, with a swimming pool and many diverse flowers. Jean Jacques had two dogs, Wolfie and Lobo, lobo meaning wolf in English. My sister and I adored these dogs and would go looking for them throughout the day. They often laid outside the house we stayed in, waiting for our aggressive, but loving pets. The dogs were covered in dirt and bugs, which is most likely where the bed bugs came from. This is only one of the things that eventually went wrong with our stay at Jean Jacques’ residence. The previous year we had stayed there, a group of teenage boys were staying in the house next to us. One morning, Jean Jacques showed us that his truck had crashed into a tree the night before. Regardless of the fact that teenagers were staying at the residence, Jean Jacques truly believed that my mother had crashed his truck. My mom was surprised that he even implied this, wondering why he didn’t just ask the teenage boys.

“Do you know anything about my truck crashing?” he asked.

“No, I don’t know,” my mom replied, starting to realize he thought it was her who did it.

“Are you sure you don’t know anything about this?” His eyes widened, as if implying my mom had done something wrong.

“Are you suggesting that I crashed your truck?”

“Well, did you?”

Although Jean Jacques seemed to have already expressed his feelings about Americans from his assumptions about my mother, he decided to go even further the next year at a dinner he invited my family to. When my dad came to stay at the residence with us for a

10

week, my mom finally accepted Jean Jacques’ request of going to dinner with her. We all piled into his car and set out to an unfamiliar restaurant location. The night started off semi-normal, other than the fact that an old fat Belgian man was driving my family to an unknown bar in a foreign country. When we arrived in town, the restaurant was closed, so we went to a cafe. There, Jean Jacques ordered drinks, and we all sat down to talk. This conversation ended up going wrong very quickly. After many rounds of drinks, some that Jean Jacques snuck to the table, he started to get quite aggressive. Somehow the conversation of politics came up, and Jean Jacques began shouting about his particular views on the American government at the time. My sister started crying, which made me nervous, and for dramatic effect, I started crying too. My parents tried to diffuse the situation and get us all out of the cafe.

“Jean Jacques, you have upset the children. Please stop shouting,” my mom said.

“Oh oh oh oh! I didn’t mean to upset them!” Jean Jacques would say, and then continue to get worked up and shout profanity at my parents.

“I think we need to leave,” my parents eventually said. It took an eternity to get the check, and it was an awkward, silent drive back to the house.

My parents spent the entire next day searching for somewhere to stay, and the next morning we wrote Jean Jacques a note before we left. Although he sure was a pain, we did feel sorry to leave with no warning. He will always have a place in all of our hearts. We left the note in the house and gathered all of our belongings. Then, we drove off into the sunrise, with our own car, regardless of what Jean Jacques believed about my mother stealing and crashing cars. •

11

Maia Collins ‘24 | Age | Pencil

The Plane with No Destination*

Tara Benning ‘23

The cold crisp air makes her throat dry. Her old ears cannot withstand the loud hum. Lee’s skin gets a wave of chills, I don’t remember getting on this plane, nor booking it. Where am I? Where am I going? Where is Art?

A burst of light stings her pupils, and she blinks to ease the pain. Her head gets slammed with an unimaginable ache. The chill over her wrinkled skin is still present, but the loud hum slowly dissipates, where there is no longer a hum, but a subtle rhythmic beeping and clacking of heels.

Her eyes finally adjust to the light and finds herself in a cot, but it’s cold, and the thin sheets keep in zero warmth. The beeping is still there, yet it seems distant. Lee manages to turn her head to the side and is met with a woman laying in a bed adjacent to her. The beeping slowly becomes an annoyance.

“Excuse me. Where are we?” Lee asks, with no response. Is she awake? “Hello? Where is Art?”

With a slight mumble under her breath, her roommate bites back, “We do this every morning, Lee.”

She feels as though she is pestering, so she dials back and sits staring at the bird feeder attached to her window, watching the squirrels make their way up to steal some food.

A woman in purple tagged with the name ABBY approaches her. “Lee, you have visitors again.”

“Is it Art?” She hasn’t seen Art in what seems like months.

A small child skips up to her. She’s very jumpy and energetic, with bright blonde hair, and shoes sparkling each time her feet touch the floor. Behind her are two other girls with darker brown hair. They look like they are slightly older than the blonde girl.

The yellow-haired child shocks Lee with a sudden hug.

Who is this child? Lee thinks with a growing grin. She feels like she has not received a hug since her hair turned gray.

The family with dark hair slowly meets up with the blondehaired girl. The two other girls begin criticizing the blonde child for scaring Lee. “Sophie, you know you’re not supposed to run up like that. It scares her,” one of the older brunette children states.

“No it’s okay, I don’t mind,” Lee answers.

One of the adults makes a gesture for the other to go around back and wheel Lee into a different area. “Come on JR, let’s take her onto the patio for some fresh air.” Lee smiles as she lifts her feet to get

Iris Wilde ‘22 | Untitled | Photograph

12

wheeled away. Not sure who these people are, she is grateful that at least someone acknowledged her. She has a constant overwhelming sense of loneliness, so having company is comforting.

Out on the patio, there is a koi pond. The children run over and begin watching as the koi swim through the vegetation.

The moment sparks something in Lee; it is as though she has seen this before. As the children watch the fish, the two adults accompanying them sit on either side of Lee. One is holding a large book. Lee loves to read but has never seen a novel that huge with such a thick cover.

Somehow it finds itself in Lee’s lap, and she instinctively flips the cover open. Though it’s thick, it is shockingly light. She is met with a page with an array of four photos. All photos are of the three children.

Confused as to why she is looking at these photos, she continues to flip through the pages.

It isn’t until she comes across a photo of herself on her wedding day. Why do these people have this photo of Art and me? She’s overwhelmed with confusion and concern. Who are these people, and how do they know me?

The man takes the book and quickly closes the cover as the children start over.

Bombarding Lee with questions, the three begin looking very familiar to Lee. I remembered three children always coming over to Art’s and my house. Lee thinks, That must have been years ago, I can’t even remember their names.

Lee just sits looking at the children, not registering the vast amount of questions being thrown at her. In one ear, out the other. It isn’t until one-word sticks in her head that takes her aback. “Grandma.”

She hasn’t heard that word in so long, it feels foreign.

Though she stays paused on that one word, the questions don’t stop. The two adults restrain the children from speaking all at once. It doesn’t help, Lee is still pondering the one word. Grandma, who were they calling Grandma? Is it me? Am I Grandma?

The confusion takes over Lee. She’s overcome with fear. She calls for the nurse tagged ABBY.

The two adults take Lee’s hands. They’re cold and trembling. She sees a stranger in the woman, but turning her head to the right, she sees a familiar face.

Art. It is Art.

“Art? Is that really you?” Lee asks as her hands relax.

“No, Mom. It’s me, JR.”

A look of realization comes over Lee. She looks at the man with confusion. “No, it can’t be. JR, you were so young the last time I saw you.”

“When was the last time you remember seeing me, Mom?”

13

“Just a year ago, at your wedding. Your wedding to... to... to her” Lee has a moment of great realization. “Jean, wow how old you’ve gotten.”

“Mom, we’ve been married for twenty years.”

“No that can’t be,” Lee began. “It was just last year.”

The children line up in front of Lee, and she begins to look over them now that they are no longer strangers. “You three. You have gotten so old. I remember when you were just this tall,” holding her hand just above the large wheel of her chair.

They aren’t sure how to properly respond to that answer, so the young girls just look blankly with smiles.

She looks over at the three girls seeing them, but the faces aren’t as she remembers. But they also are no longer strangers, just faint memories.

At the stroke of eleven, it is time for lunch. Lee is wheeled back into the building and brought into the dining room. She has a table to herself, accompanied by the large book of photos, as her grandchildren wave their final goodbyes... until next time.

Lee wonders how she could ever forget such memorable children.

As they walk away, Lee is filled with joy at how someone finally visited her. She always feels alone without Art here. But she wonders, Who was that blonde-haired child?

By dinner time, she’s ready for bed, but she still has the thick book with her. Overcome with boredom, she begins to flip through the pages filled with photos. She makes it to the end of the book, wondering why her family never visits her.

Looking out her window, Lee notices someone has kindly filled her bird feeder, replenishing the bird’s supply for life. She realizes, regardless of how many times the feeder is refilled, eventually the once abundant birdseed will deplete to empty hulls, devoured by the plague of squirrels.

She dozes off to sleep in the dark cold aircraft. The loud hum of the plane sends chills over her skin. Where was she going? Left alone in the stillness of the plane, and the loud humming deafening her thoughts

. • 14

Nelly Forrest ‘23 | Drómos | Photograph 15

Gifted Student

Lauren Wilson ‘26

Congratulations!; you earned a top score; you did fantastic!; I’m so pleased you’re planning to enroll in the geometry course this summer; you did fantastic on our Honors Geometry exam; really? I thought I did badly; you teach yourself that this is how you pass without studying because you never learned how; this is how you leave assignments until the night before they’re due; this is how you feel guilty every second you aren’t working; this is how you tell yourself it’s not that much to do; this is how you tell yourself you have nothing to be upset about; why are you upset; you’re being dramatic; stop crying; it’s not a big deal; you got this; you can do this; you studied for this; except I didn’t study; but you’re still going to pass; you’re going to get an A; you’re going to get 100; you need to get 100; this is how you get 100; this is how you keep from being disappointed if you don’t get 100; this is how you keep from crying if you get below a 90; this is how you keep quiet if you got an 87 but your friend got a 72; then your parents say of course they care about your grade; they would be happy with any grade you get! even if it was an 83!; that’s not funny; then they ask why you didn’t study; I couldn’t, I just couldn’t; why didn’t you start it earlier?; why did you wait until now?; you had time on the weekend; you should’ve done it; you’re in high school now; don’t expect to have time to rest on the weekends; you can’t just sit in your room relaxing all day; the time for relaxing is over; I know that; you can’t make careless mistakes; that’s not something I can control!; what don’t you understand about it?; it’s simple; it’s straightforward; it’s obvious; don’t say that; it really isn’t; but look! on mySCH, your grades came out; I saw; you got all A pluses; that’s amazing; I know; we’re so proud of you; thank you; why aren’t you happy?; why can’t I feel happy?; this is how you just feel relief when you get the 100 instead of feeling joy; this is how you get ignored because you don’t need any help; well you should’ve spoken up for yourself; but everyone talked over you; you didn’t need help anyways; this is how you keep from having a breakdown when you don’t understand the math anymore; this is how you teach it to yourself because you don’t want to ask for help; people make you feel stupid when you ask for help; you didn’t need help anyways; this is how you get unreasonably happy when you finally get it; that took forever; but then you wonder if you’re even good enough to be in that class; you think the tenth graders will hate you; why would they hate you?; they’re older and they’ve worked harder; but I worked hard; you didn’t work hard enough; but you can’t be intimidated by them; this is how you make friends with them; this is how you actually enjoy math class; this

16

is how you get to know all the smart kids; this is how you make a smart friend and this is how you share all this with her and this is how you cope when she leaves; this is how to fake it til you make it; but what if I don’t make it?; you’ve worked too hard to stop now; so this is how you fake a smile; this is how you laugh so you don’t cry; this is how you never give up. •

After Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl”

17

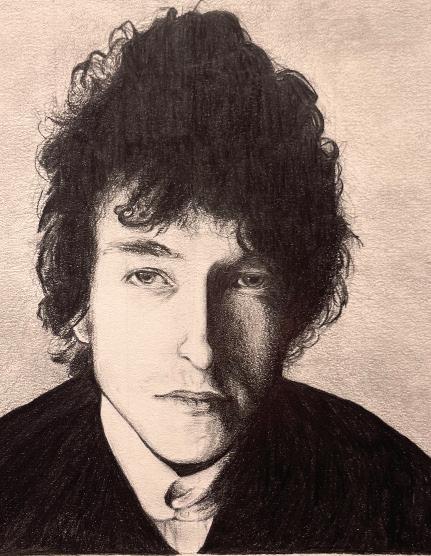

Georgia Barrick ‘25 | Bob Dylan Portrait | Pencil

Cheating Fire*

Griffy Whitman ‘25

“Dude, Mark, why can’t we just do it together like always?” I asked, almost yelling over the incessant combination of the whirring generator and muffled voices. With people on all sides, and backpacks brushing elbows from every direction, it was easy to forget the standard hushed, secluded high-school dialect. It always surprised me that anyone could hear each other at all in there.

“Why can’t you just study like everyone else?” Mark retorted, walking next to me with his hands in his pockets.

“No way, really? You’re the one who doesn’t study like everyone else! You always just know everything. School is so…”

“Okay Joe, fine, just chill out.”

So we got to English and, as usual, Mark and I sat in the back, with him to my left and no one to my right. We always waited ten minutes or so to begin our infallible master plan, even though we knew Ms. Smith didn’t really care.

Ever since sixth grade, Mark has had this mechanical pencil with a huge compartment for the lead. That compartment had more than enough space for all the little pieces of graphite, plus ample room to spare for the only other logical addition: post-it notes.

Mark would finish whatever test it was within those first ten minutes (he always did it fast because he knew everything), while I just looked through the papers pretending to be doing something. Then he’d take out a post-it from the compartment, copy down his answers, and put it back. Mark’s act was the best part. He’d choose between either tying his shoe, dropping his hat, or grabbing something from his backpack, but really he would just put the answer-infused mechanical pencil onto the ground for me to pick up.

After a couple times when we started I bought the same mechanical pencil as him so that we could trade on the floor. That way it looked like Mark still had his pencil even after the charade. I wasn’t stupid. And our plan— flawless. We could never be wrong because Mark never forgot the answers.

But when I received the post-it that day, I was actually a little skeptical. Mark wrote all C’s!

I stared at the identical line of letters, thinking there was no way it could be right. Normal pencils scratched papers, and fluorescent lights hummed, and I wondered if Mark had turned to trickery, attempting to teach me some kind of a lesson because he didn’t want to help me in the first place.

I still duplicated his test, though not without apprehension. I

18

asked him about it when we got back to the hallway.

“Yeah, obviously I know it’s right, and no, I wasn’t messing with you. But I don’t know, Joe. I just don’t feel good about cheating like that now, you know?” Mark fiddled with his pencil as we trudged away from the class.

“What are you talking about? We’ve literally done it forever. I wouldn’t even call it cheating. Cheaters are supposed to get caught.”

“Joe, how are you gonna do the SAT if you don’t know any of the vocab?”

“I don’t know; I’ll figure it out, Mark, it’s fine.” Frustrated by my friend’s ignorance, I turned the other way to go to history: the only class I didn’t have with Mark. Usually I’ll stray from the most convenient route to walk with him, but on that day I just needed a break.

Halfway through a lecture about the French Revolution my cheek melded with the cold desk. The black and white spotted surface provided refuge from my fight with Mark, as well as the wealthseeking French nobility, even though the desk’s legs were wobbly and its underside was riddled with old, dried-up pieces of gum. That bond between my face and the table broke only at the end of the period, when Mr. Henry casually mentioned the fire drill that would take place in fifteen minutes.

I popped up, aware of the now urgent situation. Every fire drill has been a panic since March of first grade. Since what happened. I don’t even have a photographic memory, but I can still picture it vividly.

It’s definitely worse for Mark, but that kind of experience isn’t something anyone forgets, even if it isn’t their loss directly. I remember everything. At least, I think I do. I know sometimes the details get messed up over time.

We were playing with monster trucks on the floor of Mark’s old playroom, on the twelfth story of his old apartment building in the city. The carpet was a speckled mixture of turquoise, red, and royal blue. We both always wanted the cool, blue truck, so we had come up with this agreement where whoever’s house we were playing at would get to have it. Our moms even made a whole contract because we got so mad at each other. We had to sign and everything, so I guess it was actually a violation of the terms when Mark let me have the blue truck that day.

An hour into the playdate, we were both hungry. Mark asked his dad, the only other person home, to make scrambled eggs, specifying that they needed to have cheese. His dad gladly obliged, but told us that he had to shower, so he requested that Mark or I start the process by grabbing the eggs and milk.

Mark, starving by then, decided to not just get the items, but also to put his six-year-old cooking skills to the test, because he “remembered what to do.” No one knew the actual extent of his

19

memory yet.

Leading the initiative, Mark told me to pour the milk into the bowl he had already cracked the eggs into. My first grade cooking apparently wasn’t on par with Mark’s, because I missed a little and spilled a decent amount of milk onto the counter. Mark said it was fine and continued getting everything else ready, but his fatal mistake was turning on the stove.

It was actually all going well at first. Mark added the milk and eggs to the pan, and while getting out the cheese he asked if I could clean up the spill. I listened, of course, because even at that age I wanted to be a nice guest. Obviously neither of us realized the proximity of the milk to the open flame. If we did, I never would have left that paper towel so close. The paper towel that Mark’s innocent arm would knock under the pan.

From there it happened fast, but I froze. Mark ran to bang on the bedroom door and returned with his half-naked dad to find the flame starting to climb upwards. It jumped first to the cabinet above the stove, then to the wall above the microwave, and finally painted the canvas of the pantry door in a terrifying bright orange. Mark’s dad acted fast, too. He seemed to know exactly what to do, insisting that Mark and I leave while he put out the fire.

“D-dad…” Mark stammered.

“I’ll be fine. Just go with Joe. Find a grown-up to call 911,” Mark’s dad replied without hesitation.

So Mark pulled me out the door, young and naive enough to believe his father’s words, telling me again that his dad would “be alright.” Still somewhat paralyzed, I took a final glance back into the kitchen as we left, in time to see the flame leap from wall to table, the table Mark’s dad was standing next to. Then it covered his white New Balance tennis shoe, and, just as it had the cabinet, climbed upwards until it enveloped his left pant leg.

I couldn’t speak. My feet couldn’t move. I think Mark probably dragged me out that door. I know now that he never even looked back. I only told him what I saw when we were all the way on the ground, with everyone else who had been evacuated from the building.

It was one of those images that just never disappears. I was haunted for years, but for Mark, it’s different. Even though he didn’t turn around and can’t picture that culminating flame, he remembers everything else. He told me once that the sounds are the worst. Every single noise from that day. Every feeling, every smell.

We were both excused from fire drills (ironic, right?) because the alarm was a trigger. Now, even though I’m usually alright, I always stay inside to find Mark losing it under the fire extinguisher in Hall-B.

Yeah, I was still technically supposed to be mad at Mark, but I knew he would need me. He needed me way more than I needed an-

20

swers to any future vocab test.

When the alarm went off, I had to walk upstream against a river of people, all moving like zombies towards the same small door. After breaking out of the crowd I rushed to the usual spot, the intersection of tan marble floor and pale blue locker and dotted tile wall. I expected Mark to be sitting down, just trembling, but with every step I heard his heaving, uneven sobs grow louder. Then, as I approached, I realized Mark was stuttering one phrase through his cries.

“I can’t. I can’t. I can’t.” I knelt beside him.

“Mark, you can’t what?”

“I can’t remember.” I was at a loss. Mark always remembered. I didn’t know what to say.

“W-what?”

“M-my dad. His voice, I can hear it when th-the alarm, but…” Mark’s left leg quaked, each movement radiating agony. It was like he thought the memory would come back if his heel could just tap the ground hundreds of thousands more times.

“Do you remember everything else?” There was no right question to ask.

“Yeah, everything else is… But Joe, I still know all the answers, it’s just I-I lost his voice.” Without any particularly reassuring words, I sat down, hoping my presence would suffice as at least some consolation. “W-we can still do our thing on tests Joe, it’s fine.”

As if that’s what I was worried about. I said nothing, because that mattered as much to me now as whose turn it was with a stupid blue monster truck.•

21

22

Leah Schnee ‘24 | The Complexity of Pigmented Vision | Oil

23

Katharine Rossman ‘23 | All-Seeing Hand | Woodcut Print with Ink

Robbed Anonymous

Robbed.

Precious time spent wasting away in front of screens. Desperate attempts to connect, screaming, reaching out for a hand to hold.

Masked emotions, suffocating ourselves in thin pieces of fabric that can barely hide our sorrow.

Six year olds ripping open plastic packages and swabbing themselves like they’ve done it a thousand times before; they have.

Teenagers committing to universities they haven’t even seen yet. Adults becoming lazy and social stamina is at an all time low.

Every little sickness is made ten times worse; you wonder if it will be your last.

Fear looming around every corner, lingering on every surface, hanging in the air like smoke.

Hours spent by the television, listening to the radio, reloading news outlets waiting for developments.

Staring at the world through a window, the loss of rushing of cars and incessant chirping of birds.

When will we learn?

How many more years must we suffer until we run dry, our pockets empty?

The void in your mind isn’t enough to keep you sane, with tears in your eyes you say, “Help.”

Annie Gu ‘23 | Untitled | Mixed Media 24

You Are What You Eat: A Film

Hans Bode ‘23

I’ll call this film “You Are What You Eat”. When thinking about my relationship with food, I couldn’t help but think about its intersectionality with my sexuality. The idea of being feminine or masculine in the gay community has brought a great deal of stress for me. When I eat and work out more, I think I’m becoming a more masculine man, whereas when I eat less and don’t lift as many weights but go for more runs, I feel like I am more of a feminine man. It has to do more with just how I feel, though: when I used to wear crop tops, I would pay a great deal of attention to my waist, and hence eating less would mean I would look better in a crop top. Then on another day, I would see a masculine gay guy dating another masculine gay guy, and I would think about how I wanted to be like them. When I am looking for a relationship, I find myself thinking to myself, does that guy like masculine or feminine guys? No matter how I look, some of the guys I am interested in aren’t going to be attracted to me. I will say I have come a long way from this point and have learned to prioritize myself rather than trying to please other men and simply prioritize being healthy.

The way I try to showcase this in my film is by starting out the morning by looking at the masculine men on my wall. I go downstairs and think about eating a sandwich from Panera and immediately the masculine men from my wall pop into my head; however, after I look up the calories, I think about all of the feminine and thin men I see on social media. The film ends with me deciding to eat an apple, thereby showing that on this morning I decided I wanted to look like a feminine man to keep myself thinner.

The point of this film is to show how food influences the way one looks and how it can feel like more food equals more masculine while less food equals more feminine, and how in the gay community that isn’t as simple as it may be for men and woman deciding whether or not they want to appear masculine or feminine. •

25

A Childish Linger

Ava Szalay ‘24

For all the broken fur on my Promised polished coat

For all the stretchy knuckles

Promised stiff and strict

For all the holidays

Promised bright and holy

For all the dinner plates

Promised royal and rounded So many moments, Promised

Oh poor young child, you never learned that life tends to paint towards disorder,

You cried when your donut fell to the ground

The frosting laid on the ground and stared at you, This was the end of it all

You wondered why adults cried

Why your nose bled during class and on the playground

Oh poor young child, you never learned that Perfection is premeditated, not a natural state of being

Oh how i wished you knew

Before you let the tendencies tend you towards destruction

Before you let the world crush your hopeful meridians, Trash your sturdy crown, Oh how i wish they had warned you, Used promises with honesty and kept you from breaking just as the world does.

26

Baylin Manusov ‘25 | Untitled Girl | Acryllic Paint 27

Artist Profile: Matt Rizzo ‘24

Harry Fifield ‘24

The initial reaction to Matt Rizzo’s studio is that of intoxication. Neon lights and heat lamps buzz quietly in the background. Fermenting cacti stand propped up by dowels and books next to the door, and piles of drop cloths and dried paint brushes crowd any available surface. Adjacent to the door sits a squashed chair with exposed springs and worn fabric, blending perfectly into the Pollock-esque aesthetic of Rizzo’s basement studio.

After clearing the paint-splattered stack of art books on the chair, I sit down and am overwhelmed by the ten-foot goliath of a painting on the wall facing me. Rizzo stands in the corner, filling black ribboned, paint bubble-face-shaped figures with green paint from a palette across the room. The previous sentence is as tedious as it is accurate. The artwork before me opens into the yellow-pocketed fields of Easter Island. The muddled background fades behind striking figures, bending and folding onto each other, stone faces melting into rounded pebbles. Hundreds of previous works sit behind the newest installment, sanded down to a glow of manganese purple and dots of yellow and green. This painting, while so dominated by black, reminds me of sunny pastures and green sublime. It is as if the figures in the image have a saxophone to their lips as Charlie Parker wails into the dark basement. Smaller canvases lie beneath the spotlight. Rizzo’s pieces cast to the side could be nailed into the MET and no passerby would bat an eye. One painting in particular, resembles an ancient cave painting, an onthe-nose comparison. Held inside a brilliant blue is a chiseled hole of black and burning flame. The embers inside glow as if the archeologists were holding their lanterns and torches up to the ash and pigment spread across the cave ceilings.

Rizzo displays a proficiency in art knowledge and technicality that is astonishing for just a second year of painting. His work is exploratory and playful, often recalling the works of New York’s finest expressionists, though Matt would shudder at any comparison. He paints for the sake of the paint. His work is accessible and comforting; he stifles the necessity for interpretation, though it is readily available. Rizzo gives the viewer a spectacle in color and technical ability, leaving the truest meanings behind the eyes of the onlooker.

Harry: Okay, so when did you first start?

Matt: For the first time I ever painted, I think I was like 12 or 13. I was looking at Bob Ross. I thought it was funny. Landscapes and stuff. Like, Interview continued on page 36

28

29

Hirmand Azimi ‘23 | Artist at Work (top); Cambiare (bottom) | Photographs

30

31

32

33

34

35

who would make a career out of something like that?

H: What were your inspirations? When you first started -- ninth-grade tenth-grade. What did you like? What were you looking at?

M: Well, I knew I liked the Renaissance teachers. The DaVincis, the Van Goghs. But in ninth grade, I started looking at the impressionists.

H: Do you think those artists inspired your work?

M: I like their use of color. I wasn’t trying to paint like them. I think the impressionists are what I drew from the most, especially at the beginning.

H: How so?

M: It wasn’t really color theory. I was just looking at the way they use color. It’s not color theory because a lot of the time it’s not color you see in real life. In impressionist paintings, they use manganese purple. I mean, they use an insane amount of it. Almost every color that they put on a canvas. And I just thought that was interesting, because I mean, it’s just this one color, but it’s so soft that if you put a different color into it like green it makes a completely different color that you wouldn’t even attribute to manganese purple.

H: Is that something you tried to simulate?

M: I mean, I played around with it but I don’t really try. I try not to copy. My biggest fear is being derivative. Somebody else’s stuff coming through in my work is something I want to avoid.

H: Who would you say you get the most inspiration from now?

M: Over the past couple of years, I’ve looked at so many paintings that it’s like a filing cabinet in my unconscious. So I have a lot but the ones that I consciously look at right now. you got the Philip Costas, And Ray Smarts. But I’ve seen so much different stuff I don’t even think I find inspiration from specific people. It’s more like themes and schemes that I take in more.

H: Have you varied as time has gone by? Do you think you’ve gotten more and more abstract, have you strayed away from traditional shapes or traditional meanings?

M: I mean, figuration, yes, but I wouldn’t call myself an abstract artist.

36

It’s like Nero. I’m not an abstract expressionist. The New York school back in the 60’s, they didn’t like figuration. They just wanted colors. They wanted to express true colors. But if you look at the layers of Cooney, there’s an element of figuration, like in the biannual book over there, so it’s similar to that. I wouldn’t say I’ve strayed, I think my art has matured. I mean literally, everything has changed, literally everything. I began to experiment more, I brought in my vocabulary. That’s really all it is.

H: Just broadening your landscape and your knowledge?

M: Well, yeah, my knowledge of how things work. Over time my confidence has carried me into more experimental things. Of course, I use inspiration, but a lot of the time my knowledge just helps me inform what I want to express.

H: Do you think you go through conscious collections? Do you create a set of paintings that are similar and move on to something completely new? Or is it evolving over time? Is it sudden or gradual?

M: Well, recently I’ve been doing a series of these kinds of similar pieces. I like to think of it as a bullet. And is passing all this stuff and it keeps going and going and then it hits the target. And then that’s where the series comes in. But I don’t know, my opinions have definitely evolved. As you go through different processes, you find different styles. And that style kind of shows through paintings. And then you fire again and move through new processes until you find something that sticks.

H: Do you ever worry that your work is becoming so abstract? Or you’re losing what you want to express?

M: Not necessarily. I rarely go into it with something to express. I just think the nature of paint is beautiful. That’s really what my paintings are about… Like, when you look at Bob Ross. Is there any deeper symbolism, anything in it? No. It’s just beautiful. A nice landscape. When you go to Longwood Gardens and you look at all the trees and the flowers and stuff, you’re not trying to find some deeper symbolism, and that’s good. Sometimes I get conceptual, but usually, it’s about the paint.

H: Do you ever find you ever finish a painting and find meaning? What’s something specific that you remember?

M: Well, I was doing biology, and there was a pinion there. And I just

37

had painted like this little embryo thing. Things just happen. You know, if you look too closely, trying to find symbolism and stuff, it becomes almost meaningless. At least in my opinion.

H: If someone sees your work and finds meaning? Do you take pride in that? Or do you kind of scoff?

M: I mean, if they find meaning, that’s great, you know, cool. Maybe they figure out how it relates to their life. I don’t know. But I mean, to me, it’s about the process, the paint, and the colors. And I think there’s a greater simplicity of that, and it makes them easier and more accessible.

H: Would you call your work accessible?

M: Yeah. Because when you look at a Renaissance painting, you have to understand the time period, the politics, the people, you know. My paintings, you can just look at, you can feel them. When you go look at a Kooning or a Pollock, you know, you can just look at them. You can see the structure, and the beauty, but you don’t have to bog yourself down in symbolism from the time period. I just think that’s easier. When the painter drops the paintbrush and becomes a psychiatrist, that’s when I think the work suffers.

H: What’s your opinion on someone like Jackson Polluck?

M: Revolutionary, but I think overhyped, in a way. I think there was plenty of that in the New York’s core abstract group. There was a lot of talent that gets overlooked. Also, I think there were other painters that weren’t necessarily involved in that group, that were doing meaningful things at the time. It was just a group of people who were there in New York for a myriad of different reasons. It’s not a baseball team, you know, It’s just a group of people that fed off of each other.

H: Let’s take Rothko, for example. Like when you look at his work, what do you see?

M: Well, he was experimenting, he was listening to Mozart, and he wanted to create that, you know, that kind of emotional resonance. I like when you listen to, Requiem, or a Mozart symphony or something. There’s a flood of emotions that comes through, and he wanted that show that you could sit down and you could look at a painting and you could cry, you know, the painting is a symphony orchestra.

H: Is that someone that you’re inspired by? Do you try to evoke that

38

much feeling?

M: Yeah. And you also think of like, the way he painted he was sitting in like a studio with turpentine fumes going everywhere. I mean, it was like a brutal thing to do. He was going mad. I never try to make people feel things when they look at my paintings but if that’s what happens that’s great.

H: I mean, do you take it seriously? Do you take your work seriously? When it’s finished?

M: I mean it’s serious, but I think the whole idea of being a painter is silly. You know, I can understand that. I don’t have any ego about what I do. This is a silly process.

H: Do you find your work therapeutic?

M: Yeah. Actually, no, no. It’s stressful. And I’ve never been confident, you know. There’s no confidence in a painting. Doubt. I’m very doubtful.

H: But I mean, you’re alone in here. And you’re working on these pieces with just yourself. Do you find peace of mind?

M: I mean, it’s better than being in class.

H: Where are you getting that, like therapy? Where are you getting the enjoyment?

M: Enjoyment? When it’s finished.

H: So when you step back and look at it, that’s where you’re getting your fulfillment?

M: It’s beautiful. you know, when you can look at the greater simplicity, I think that’s so beautiful.

H: That’s really interesting because I feel like, a lot of what you’re saying is to like focus on the process, but it doesn’t even seem like that’s really the part that you enjoy the most.

H: I’ll wrap up. Do you have any closing statements? What are some strong opinions that you have about art in general?

M: Stupid, don’t do it. Don’t make your life into this. Stupid. I’m gonna die penniless and broke. But I’ll have fun. I’ll have fun. •

39

i carry your heart with me*

Sarah Shoff ‘23

I carry your heart with me

I carry it in my heart

I carry your heart with me

I carry it in my heart

I carry your heart with me

And wherever you go, I go, my dear And whatever is done by only me Is your doing, my darling, my love

I fear no fate, for you are my fate

My sweet, I want no world

For beautiful, you are my world, my true And it’s you, it’s you, and it’s you

I carry your heart–

I carry your heart with me

And whatever a sun will sing is you And whatever a moon has always meant Is you, is you, oh it’s you

Here is the secret that nobody knows: Here is the root of the root, and the bud of the bud

Of the sky of the sky, of the tree called Life

Which grows (x6)

Higher than soul can hope or mind can hide

I carry your heart with me

I carry your heart inside

I carry your heart with me

I carry your heart in mine

I carry your heart with me

I carry it in my heart

I carry your heart with me

I carry it in my heart

Oh, you are the wonder that keeps the stars apart

Oh, I carry your heart

40

Oh, you are the wonder that keeps the stars apart

Oh, I carry your heart

I carry your heart, oh

Oh, you are the wonder that keeps the stars apart

Oh, I carry your heart

I carry your heart, oh

*Lyrics adapted from E.E. Cummings’

“[i carry your heart (i carry it in’]”

41

Jacob Becker ‘23 | Collage | mixed media

The Aftermath of Trauma

Gabby Adams ‘23

Gabby Adams ‘23

She turned to others for love

Toxic boys fueling her hurt with compliments

Gossiping girls waiting to hurt her next Unfit family members trying to stop her success

She turned to others for love

People willing to hear her out

People she trusted with the trauma she faced Venting and venting looking for relief

She turned to others for love

To fill the void she never received

To feel loved and appreciated

To have an emotion fulfilled without trauma

She turned to others for love

42

The Mirror Anonymous

Looking in the mirror made me hate myself a little bit more every time, but for some god forsaken reason, I couldn’t stop. A grotesque creature stared back at me with cellulite that felt as big as big as craters and stretchmarks drawn in dark purple sharpie, lifelong and permanent.

Thinking about all the things I wanted to change about myself seemed as easy as taking a breath. I’ve always been aware of how I look, not only to myself but to other people. I’ve always worried about the way I’m perceived, always analyzed social situations and compared myself to my peers. It might be because I was never small, not even growing up. Society told me that bigger equals less: less human, less desirable, less lovable, less worthy. I never had any reason not to agree with society, especially when I constantly felt like the elephant in the room.

As a child, I loved shopping. I would walk around Nordstrom Rack for hours, wandering aisles just for the camaraderie of it all. I loved trying on fancy clothes and the highest of high heels until the days that the harsh fluorescent lighting of the dressing rooms had me focusing on everything but the pursuit I once loved. I would go home and cry, wondering why god put me in a five-foot-eight curvy body at thirteen years old. The feelings of shame and embarrassment were deep within. I was on an iceberg, floating alone in the great vastness of the ocean, just hoping the earth would open up and swallow me whole. My plummeting self esteem and persisting misery was overwhelming but the thought of acting on it was terrifying, until it wasn’t.

The summer going into sophomore year, I got sick. Some stomach infection I guess, but the treatment was metronidazole, a drug notorious for killing an appetite. The perfect storm of a measly appetite and crippling body image issues landed me in CHOP for inpatient eating disorder treatment. During my month of pure and true eating disorder behavior, I thought I felt happy. I was losing weight too fast for my own good, but at least my clothes were baggy. At least my stumpy legs were slimming and my most hated stomach fat was trimming down. At least I could go into the dressing room with harsh fluorescent lighting and not like myself just a little bit less than before.

I was awoken to the door opening and “Good morning, it’s Shelly from the lab” at 5:45, promptly poked with a needle to get what seemed like eighty vials of blood. I opened my eyes to see the rising sun cast a golden honey hue on the beauty that was the CHOP Seashore building. Sun rays filtered through my fourth floor window, shedding

43

light on the yellow and black “get well soon” card, a beautiful bouquet of bright sunflowers and blooming chrysanthemums, the faded green succulent my mom brought from home. Even still, it was just a hospital room. One with a whiteboard telling me who the nurses for the day were and a constantly beeping heart monitor connected to the ECG stickers on my chest.

Everyday during vitals, I was given a scratchy paper gown and told to go to the bathroom and change, and what awaited me in the bathroom but the mirror. The mirror where over the course of nine days, I picked apart every little thing on my body. I noticed everything that changed during those nine days: the stretchmarks that showed up on my hips, my swollen eyes surrounded by deep dark bags, and the small pouch on my lower stomach that I worked so hard to get rid of that reappeared.

I survived the hospital and things were going well until my bad thoughts started to drown out my good ones. I was suffering once more, this time in secret, and the voices telling me that relapsing wasn’t worth it became much too quiet. Once again, the mirror became my frenemy. I gained weight in my short period of recovery; the feelings of disgust and disgrace were stronger than ever. Months were spent in the bathroom, purging every meal, snack, and drink I could. Life was agonizing and terrifying. Purging felt like the only way to take control back. I was atop a mountain, shouting as loud as possible for help to get down from this scary peak, but no one seemed to hear.

My mom caught me one day in my grandparent’s bathroom. The green carpet in front of the toilet had become my friend, a cushion between myself and the ground that kept my knees from hurting. The bottle of mouthwash was always there for me to hide the remnants of what just happened. But I was discovered and now they meant nothing.

Two months later I started an intensive outpatient program. I was depressed and on the verge of going to residential, but IOP changed my life. There was a life waiting for me beyond 3550 Market Street, Boost supplements, and despair. This eating disorder was not a choice I made, it was not something I asked for, and just because I wasn’t skin and bones didn’t mean that I wasn’t struggling.

I haven’t learned to love my body, and I’m not sure I ever will. Maybe I’ll be able to accept it one day, but at least I can say I know how to cope. I still have moments where all I want to do is purge, but my eating disorder voice has quieted down. That voice still scares me sometimes, but I’ve taken back control of my life and what happens next is up to me. My eating disorder taught me to take life one day at a time, and while I still try to avoid flourescent lighting and mirrors, I made it down the mountain safely and my iceberg found its way to the shore. •

44

45

Georgia Barrick ‘25 | Glass Box | Oil Pastel

Agharese Olagunju-McWilliams ‘24

I want to be a star but not for all the fame or glory only for the hearts I hope to finally touch, one day grasping for eyes of a little black child who was just like me with thin locked lips, struggling and drowning in silence but also anger just like I once upon a time. The air pocket I discovered was named the spotlight, however, the spotlight wasn’t a place for me, it shined on my skin differently. Or that is what one told me. Constantly type casted not only in the acting scene but also within my mundane activities, too aggressive to play a soft-spoken character, too rough to play a princess, too much attitude to be in these classes, too loud during a debate, too sensitive to participate in activities where the voice starts to shake. The spotlight was finally my place to speak, my place to express, my place to distress, however, apparently it was not for me? My dreamed about future will never be? Because apparently, I’m not the perfect beauty that they need in movies. I want to be the sun but not for just anyone, I want the sunshine to reach little black kids who were told they would never look just right in the spotlight, however when their skin shines in the starlight and sunshine, they look even more astonishing than any other artificially produced movie. The movies that shuts out people like you and me from the cinematography, all because we glow in the spotlight too beautifully.

Spotlight

46

Cooper Bode ‘25 | Skull | Pen

Dad

Mia Santiago ‘24

My dad tells me

The phone works both ways

Why cant he see He sets my world ablaze

I get easily mad by him But I still love him dearly I want to let him in But sometimes I dont act sincerely

I want him to feel separate

Because that’s what he is But he feels desperate

And I feel guilty because of this

I love my dad

But not being together makes it hard I know if he could have He would stay and heal my heart

47

How to Be a Perfect Daughter

Brielle Attanasio ‘23

You want to know How to be a perfect Daughter?

It starts with being a proper girl

You can’t give boys more ways to look up your skirt

So you always cross your ankles and not your legs when sitting at a table

You sit with your back up straight

Everywhere

Never slouch like a boy

Cross your hands on your lap at most times

When eating, make sure to use the proper utensils

Then cross them amongst your plate when finished

Only eat five bites of each type of food on your plate

You will appear with gluttony and greed if you finish your food

Only drink water with ice and a lemon

You never use dirty language, speak sexually, or look at a man for too long

Be polite, say please, and thank you

You always say sorry, be the one to apologize first

Once you are a good girl

You are ready for the world

Once you can obey your father, your teacher, your brother

You are ready for the world

You can listen to what you’re told?

You are ready for the world

Throw me out into the world!

They will grab you

Bruise You and use you

Throw you against the wall

But I crossed my ankles, Daddy

It was them

How is it my fault

They looked up my skirt

But Daddy still slapped me

See I thought this was the way to be a perfect Daughter

A proper young lady

I will just have to do better now

48

Departure*

Julien Friedland ‘25

Sunlight snuck through the window shutters, gently rousing John from his fitful sleep. He groaned, blinking his eyes slowly, to fight off the drowsiness. His eyes scanned his lonely room. It was unchanged. The same walls plastered with escapist space posters, detailing every possible planet that could be conceived of. The same ugly paper-mache whale he made in the first grade. The same already packed suitcase, gathering dust as it sat untouched. John had packed it over a year ago, with the intent of leaving.

His brothers and father wouldn’t mind if he did, honestly, they would probably be relieved. His brothers, with their dirty, tousled hair and perfect bodies would be able to finally yell and shout, without fear of their big brother’s traumatizing episodes. They wouldn’t have to make excuses for why their twenty-year-old brother couldn’t live by himself and had to be cared for by their parents. Father, with his immaculately tailored blue suit, and a coldness that could only be obtained from working years as a bank teller would finally have a perfect family: two normal sons, who play baseball and talk about the stock market. Father wouldn’t have to spend his hard-earned money on John’s medical bills or have to buy John’s medicine for him. John knew that they didn’t want him in the family, and they knew that he knew.

The only person that stopped him from leaving was his mother. She loved John too much for him to just walk out on her. Despite all his issues and problems, she always stood by him and he couldn’t break her heart. John sighed again and swung his barely functional legs off his bed. He cracked open his door and dragged his broken, useless legs to the stairs. The old floorboards creaked and groaned as his waifish form carefully navigated the harsh terrain that was his house. Instead of hearing the quiet laughter of his brothers and the mellow voices of uncaffeinated parents, there were only the pings of cutlery against scratched, worn plates and the faint sound of chewing. The only voices that John could make out were mumbles and grumbles, far too faint to hear. They were using hushed voices, the way one would use to talk about a taboo subject. Probably him. Down in the kitchen, he was sure his family was reviewing every possible reason he was a burden to them and how the household would be better off without him. John tried to lower his ear to the crack in the closed door to the kitchen. His useless, awful body failed him. Shit. First his pathetically small legs, then his shrimpy arms tumbled down the stairs in a loud Crash and pushed him up against the door, like a limp pretzel. John closed his eyes. He felt the door slowly open behind his back. His mother’s kind hazel eyes gazed

49

down at him. John’s muddy brown eyes gazed back up at her, pathetically. Wordlessly, she helped him up and guided him to the table. Everyone stared as John sat down. He had the feeling that he had just walked into a conversation that didn’t really concern him. Without even looking at his family, John began to shovel food into his mouth. Something wasn’t right. Something definitely wasn’t right. Like usual, John’s father and brothers refused to meet his stare, but now not even his mother was looking at him.

Ah. His mother didn’t want him anymore.

It made sense, why would she? After all the suffering and work he had put his family through, she must have finally realized that he was a drain, a failure to his family. It hurt. It stung. John wanted to cry. Each member of the family kept sneaking tiny glances at him, desperately hoping, wishing that he would say something. Well, what did they want him to say? A painful knot formed in his throat, making it hard to breathe. Hard to think. His grip tightened on the fork, digging painful welts into the tips of his fingers. John mustered the courage to look at his mother. She wore a tight smile, and weary, tired eyes from years of caring for a broken man. Perhaps his mother had finally realized that the family would be better, freer without him. Free from having to hide sharp objects in locked drawers, free from the silent judgment of colleagues that a twenty-year-old man still had to be cared for like a toddler, and free from his constant panic episodes.

She too would finally have a normal family that could go out to dinner, and listen to loud music without the threat of a sensory overload. It was too much.

It was all too much.

John flung his fork against his plate. It hit it with a clatter. He stood up and made his way to the door. The family just stared at him. He managed one glance back and disappeared into his room. Alone in his bedroom, John curled up into a ball and vacillated between crying and laughing bitterly. His mind latched onto one thought - his mother probably never wanted him, she was just better at hiding it than the rest of the family. He lay against the door in his room for a while until the sun began to dip below the horizon and the shadows turned into long, distorted images.

His eyes landed on the dusty, untouched travel bag. Pulling the heavy pack onto his back, he silently slipped out of his room and down the stairs. John felt like a ghost, no longer in control of his legs. He floated through the house silently, approaching the door. A clatter. John’s little brother stood in the doorway, staring at him. John stared back, a flicker of understanding going between them. Without saying a word, his brother slowly slinked away from the door, and John walked out. •

50

The Fire of Audacity

Griffy Whitman ‘25

Summer 2022. Poconos. Overnight camp. 3 am. Everyone was asleep. We had a contraband lighter, and a hose meant to negate all risk. “Guys, what if the fire-marshall dude comes?” And with those words came headlights slicing through the darkness. Everyone bolted, but I stayed to extinguish this now massive bonfire. The car door slammed, and footsteps followed. Then… “Nice fire here, man.”

“Uhh, thanks?”

“Yeah, no big deal if it’s all controlled.” I learned two things that night. One, that Moe, the fire marshall, would attend cop school in Wyoming next fall, but primarily, to always keep things under control.

51

Griffy Whitman ‘25 | Volcano | Acrylic

Who am I?

Madeline Bell ‘26

Who am I?:

A singer?

A writer?

A reader?

A friend?

Or all of the above?

Am I brave?

Am I smart?

Am I beautiful?

Or am I merely a reflection in the mirror?

Is my life a lie?

Sometimes I lie in bed and think, Is this really me?

Sometimes it seems too far-fetched even to be possible.

And yet still, there are others where I lie in bed at my worst, imagining what might be.

Who I really am, I guess I may never know.

But I do know this:

I know what I have made, the good, the bad, and the in between.

I know what I have seen, the truths and lies of this world.

I know what I have heard, the music that will forever be a part of me.

I know enough to say these words.

And that’s fine with me.

52

From Healing to Healed

Sofia Murray ‘23

Dear someone I can’t forget despite your lack of value,

You make me angry

The anger doesn’t let me sit still I can feel the adrenaline course through my blood Ready to burst into screams

You make me down

Curled in a ball in my bed

Twitching and hitting my myself

Trying to bang out the memory

I want to hate you but for some reason I don’t I want to scream and yell that you are evil to the world Yet I can’t speak out

You make me question myself What I did wrong

If I am just thinking wrong

I wish I could have hated you Instead I hated myself

Sincerely, A girl you probably don’t remember

53

The Golden Haired Girl

Helena Fournaris ‘24

The golden-haired girl sits at the back of the class

The school supplies are astray across the desk; ripped crayons

Wide eyes surveilling the depths of the classroom Her fingers run across the edges of the writing instrument

The teacher instructs the class to stand up The golden-haired girl reluctantly grasps the purple crayon

Swaying to her feet, she clutches the colorful stick She watches the other girls narrow their eyes to the object within her hand

She shoots a glare back at the crowd of peers She rolls the shape in between her fingertips; the purple crayon

Snickers erupt in the classroom as they stare “Crayon. Crayon.” The students taunt

The golden-haired girl glances down at the crayon in her hand She throws it on the ground with a thud

She stares at it on the floor of the classroom; broken and deformed. She stomps down on it with her shoe, “Dumb Crayon. Just a dumb Crayon.”

54

Baylin Manusov ‘25 |

Baylin Manusov ‘25 |

55

Second Untitled Girl | Acrylic Paint

The Vocabvore’s Dilemma

Chad Cai ‘23

“By attributing the weather to Louise’s emotion, Chopin adumbrates her fate and augurs the plot of the whole story.”

“Chad, you swap simple words with bigger words and lose clarity.”

That was the thesis statement I wrote for an argumentative essay on “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin, and those were the words of my English teacher, critiquing my word choices.

I had long loved employing big words in my writings; I felt that they made my sentence a beautiful, commendable, and distinctive masterpiece. Say when I wrote, “The tranquilizing zephyr mitigated my dolefulness.”

“10/10,” evaluated my classmate, “loved it”.

My friends admired me as “The Vocabvore”; they motivated me to devour five vocabulary books and keep on my “unique” style of writing. Their commendation made my writings seem impeccable. My teacher’s critique thus stung. I had never considered clarity, which contradicted my creed: “The harder the word, the better it is.” This threatened my reputation and distinctiveness as the Vocabvore.

To solve the problem, I did the “omnipotent” technique from English classes: word-level analysis, aka does the word really serve a purpose. I long just copied, rather than comprehended the words. I barely know what’s under their definition, and my sole purpose for using them was their complexity. This led to my solution: Go back To the Roots, or etymology, of the words. I went beyond the definition of an unfamiliar word, broke it down into its components, and explored exactly how each part of it originated and meant.

This strategy was especially helpful for me to comprehend many words I understood only superficially and to make sure I deployed them right. Take “adumbrate,” the word I thought was the lynchpin of my thesis statement. It is derived from Latin ad-, “to”, and umbrare, “cast a shadow.” Shadows merely outline something vaguely, and that corresponds exactly to what the word means: to indicate faintly. To make my thesis more clear and argumentative, “represent” or “indicate,” both simple, straightforward, and without confusing connotations, would do a much better job.

As I was done with word-level analysis, I decided to Go To the Deeper Roots: why was I so attached to my prodigious vocabulary? The answer was simple: I felt that I was too ordinary, especially when I compared myself to others, and I wanted to be distinctive, but what’s

56

the ultimate source of that thought?

I recounted that in my childhood, since I was talkative and knowledgeable, I was considered very distinctive by everyone around me. My parents always proudly introduced my cleverness, articulateness, and distinctiveness to everyone they met; my teacher created the “Omniscient Prize” specifically for me. With that image of distinction in mind, others required high standards from me, as I did for myself. However, as I grew, reaching those high standards became harder, and I felt my uniqueness, my radiance, was dimming.

While I was in this dilemma, I saw others shine and thrive. Everyone is a sun, a radiant nova, while I was just a mundane, dark planet. I saw a transfer student socialized in the school in mere days; I saw another guy with incredible maturity; yet another wrote dozens of impressive essays; and I saw myself: “I had something; I have nothing.”

I tried to imitate them, working harder and pressuring myself further, hoping to catch them up. Still, no matter how hard I forced and chided myself, I never seemed to reach them, nor that distinctive height.

That’s when I realized why I actually had the Vocabvore’s Dilemma; the knowledge of hard words was a precious proof of distinction which I, intuitively, didn’t want to give up. The word “distinction” dominated my mind; it had become more important than clarity, than communicating complex ideas simply for an informative purpose. I began to see myself from another perspective– as another person in a furious, ambitious race to stand out from the crowd, rather than a crowd member whose contributions can be measured against their impact on their peers. My pursuit of uniqueness, I realized, was in fact the least unique characteristic about me. My friends would say I simply wasn’t seeing myself clearly enough; they would tell me: “You gotta acknowledge your glints, Chad!”

At the end, we write sentences not to show off, but to convey our genuine and entire selves, ideas, and emotions. As I acknowledged and presented both my strengths and my ordinariness, I gained more confidence in writing and everyday life, and am now able to navigate obstacles. Embracing both parts of myself, that’s the true path towards distinctiveness.

So: “In ‘The Story of an Hour,’ Chopin uses pathetic fallacy and weather to represent Louise’s emotions, prefigure the plot, and foreshadow her fate.”

And: “The soft breeze made me smile.” •

57

58

Implacable

Kaliyani Wardlaw ‘23

Most days it felt like I was waiting for a gusting wind

Unable to feel a sort of pull in either direction

To stay or to go, simply unmoved Watching you watching me

Carefully fixated but without uttering a word

We danced around like this for hours

Living in our own little worlds separate but together Silent in that tinderbox of emotion where we lived And then just like that you were gone

Oh what could have been

Now would never be, forever lost And implacable feeling filled the whole you left “Thank god it was over”

And then one day it was all there again

Face to face with you

Yours eyes shiny and fixated

Filled with questions knowing there would be no answer

Silence was our language the only way we spoke

It had always been this way

And seemed that now it would be forever so

The feeling in my chest was implacable

The emptiness that filled my chest after you

Nelly Forrest ‘23 | Wedding Day | Photograph 59

Possession

is Nine-Tenths of the Law

Sage Palmer ‘25

My pink water bottle. Sitting pretty in my boss’s hands. I could’ve gone and grabbed it from him, but something like shame held me glued to the sun-washed concrete. My campers darted sneaky glares of suspicion. They knew, damn; everyone under that pavilion knew it was mine. I just couldn’t own up to losing something as a counselor. Then little six-year-old Alyssa stumbled to her feet, ran over, and grabbed it. She tottered away as if that thing wasn’t larger than half her body. She tottered away as if that bottle was hers. And from that moment on, it was.

|

| Photograph

Nelly Forrest ‘23

Mutual Gaze

60

The Guys*

Emma Ludwikowski ‘25

Her father’s harsh screams jerk her awake. His sobs pierce through the thin walls of the house, shaking the old family portraits and silk-screened paintings of Catholic saints. Her brother is moaning as well. The room he shares with her father is a black hole of noise and misery. Her grandfather hasn’t woken yet. He will soon.

Everything important comes in threes.

Therese drags herself from her bed, leaving her room and entering the kitchen. She stumbles over her brother’s muddy work shoes on her way to the stove. She puts on the pot, idly scraping at the thinned black metal on the bottom. They’ll need a new pot soon.

As the water boils, she grabs foamy white bread slices to toast. She can hear her brother consoling her father. He must have been in the mind of an abuser, again. It always makes his very blood boil, having to spend hours trapped in the minds of some of the vilest people in the world. Her grandfather rolls himself off of his bed, the old wood floor creaking under his weight. She can hear it through the ceiling. They are a house of big men.

When the water boils, she pours it into three mugs and mixes in powdered creamer and instant coffee mix. From the sound of it, the three of them will be up discussing their visions all night.

By the time the toast is done, the men are all downstairs. Her dad gives her a grateful smile when she passes him a mug. Her brother simply takes it with weary eyes. As the youngest, the dreams always affect him the most.

“Everything okay, guys?” she asks.

“Don’t go anywhere March fifth,” her grandfather responds. Her father hits him on the shoulder, lightly enough not to bruise.