Declaration

I Laurentiu Marian Popa confirm that this work submitted for assessment is my own and is expressed in my own words. Any use made within it of the works of other authors in any form (ideas, text, illustrations, tables, etc.) is properly acknowledged at the point of use. A list of the references employed is included as part of the work.

Signed: Date: 16.01.2017

Affordable Housing after Communism: Affordable housing for young adults in Ploiesti, Romania

A Dissertation submitted to The University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the Master of Architecture.

By: Laurentiu Marian PopaTutor: Dr Lucy Montague DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE & 3D DESIGN SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN & ARCHITECTURE THE UNIVERSITY OF HUDDERSFIELD 2015 16

The dissertation examines the concept of affordable housing in Romania It defines how the topic is perceived; then it analyses the housing crises and the political, and historical context The literature review shows howthese crises have affected the existing housing situation and a specific population: young adults. Starting from this, the study narrows its focus and aims to answer the question: What issues do young adults in Ploiesti, Romania face in accessing affordable housing? This is done through a desktop analysis of grey literature and a questionnaire. The investigation and the comparison of the collected primary data with the existing knowledge reveal some of the issues: low incomes, high unemployment, high levels of overburden and low access to government housing programmes.

2.1.Defining Affordable Housing 4

2.1.1. Australia 5

2.1.2. United Kingdom 6 2.1.3. USA 6 2.1.4. European Union 6 2.1.5. Romania 7

2.2.The Housing Crisis from Communism to Democracy 8 2.2.1. Communism 8 2.2.2. Democracy 10 2.2.3. Privatisation and Restitution 11 2.3.The Housing Situation Now 13

2.3.1. Housing Costs 15 2.3.2. Overcrowding 16 2.3.3. Housing Quality 17 2.3.4. Home ownership and the house market 19 2.3.5. Social Housing 21 2.4.Summary 23

List of Figures

Figure 1: Agerpress, (n.d). Communist blocks cost a fortune. [Photography]., retrieved from http://media.hotnews.ro/media_server1/image 2008 09 24 4504055 41 incalzirea blocurilor comuniste costa avere.jpg 9

Figure 2: Soaita, A.M. (2014). Dwelling stock by construction periods. [Graph]., retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.960.5957................14

Figure 3: Eurostat, (2014). Overburden Rate. [Graph]., retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics explained/index.php/Housing_statistics 16

Figure 4: Eurostat, (2014). Overcrowding Rate. [Graph]., retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics explained/index.php/Housing_statistics 17

Figure 5: Eurostat, (2014). Severe Housing Deprivation. [Graph]., retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics explained/index.php/Housing_statistics 18

Figure 6: Eurostat, (2014). Distribution of Population by Tenure. [Graph]., retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics explained/index.php/Housing_statistics.............................................................19

Figure 7: Eurostat, (2014). Distribution of Population by Dwelling Type [Graph]., retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics explained/index.php/Housing_statistics. 20

Figure 8: Alpha Media, (2016). ANL Homes. [Photography]., retrieved from http://tvalphamedia.ro la-medgidia-se-depun-dosarele-pentru-locuintele-anl/...27

Figure 9: Employment., [Graph] Own 29

Figure 10: Education Level., [Graph] Own...………………………………......29

Figure 11: Marital Status., [Graph] Own ……………………………………......30

Figure 12: Age., [Graph] Own 30

Figure 13: Income spent on housing costs., [Graph] – Own …………………....31

Figure 14: Income., [Graph] Own 31

Figure 15: Tenure., [Graph] Own……………………………………………….33

Figure 16: Accommodation type., [Graph] Own 33

Figure 17: House owning prospect., [Graph] Own 34

Figure 18: Living with parents., [Graph] Own…………………………………34

1. Introduction

In 1923, in his book Towards a New Architecture, Le Corbusier, the great modernist architect and theorist declares, “The primordial instinct of every human being is to assure himself of a shelter” (Corbusier,1927, p.14) A few years later in 1948, the United Nations General Assembly ratified the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which recognises that the basic needs of humans should be fundamental human rights (United Nations, n.d). It is considered one of the most important document in the history of human rights and it was translated into 500 languages (United Nations, n.d). It promotes the idea of human dignity as a legal concept and establishes that each person has the right to an adequate life standard for him and his family (United Nations, n.d). This includes the access to housing, food, healthcare, clothes, social services as well as security in case of unemployment, ill health, old age, or any other circumstances that are over the individual capacity to control (United Nations, n.d). The 2015 Eurostat housing report shows that Romania's housing situation is in a crisis especially when it comes to a certain group of the population, namely, young adults between 18 and 35 (Housing Europe, 2015). The 2013 Eurostat statistics also suggests this idea and reveal that 60% of young adults live with their parents in overcrowded conditions. (Eurostat, 2013)

Considering these aspects, the aim of the dissertation is to research the issue of affordable housing related to young adults in Ploiesti, Romania. The dissertation first briefly introduces the broader context for affordable housing and the situation in Romania. It then examines secondary and primary data to understand more specifically the issues of affordable housing for young adults in Ploiesti. The first chapter is a literature review. The first section of it focuses on understanding how the concept of affordable housing is perceived around the world and how it compares to the concept in Romania, which narrows the scope of the research. The second section describes the historical context of the housing crisis in Romania, from the communist regime to democracy; to understand any connection with the present housing situation, which is detailed in the third section This literature review establishes the state of existing knowledge related

to affordable housing; the political and economic context in Romania and the housing crisis; and from this, the research question is defined: What issues do young adults in Ploiesti, Romania face in accessing affordable housing? To address this question, the next chapter examines primary and secondary sources. The first section analyses the governmental programmes that aim to solve the problems with housing that young adults in Romania encounter The second section examines the responses of 98 respondents to a questionnaire about the topic. The results aim to quantify the data about how the young adults from Ploiesti interact with the affordability of housing and the housing costs; and examines it in relation to the information from the literature review. Therefore, the dissertation aims to answer the research question and point out some of the issues this particular age group of the population has in accessing affordable housing.

2. Literature Review

The purpose of this literature review is to assess and present the existing knowledge about affordable housing; how it relates to Romania`s historical, political, and economic situation and to the housing crisis. It aims to establish the context of the research and justify the dissertation question. This is done by examining books, journals, reports, statistics, government publications and other official sources.

2.1. Defining Affordable Housing

The aim of this section is to define what the concept of affordable housing means, how it is viewed around the world and how it is perceived in Romania. According to Burnham (1998), the topic of Affordable Housing has been a highly debated one for the last few decades (Burnham, 1998). Because of the high interest on it and the increasing need of affordable housing, many views and definitions on what exactly the terms mean, have been developed. (Burnham, 1998). As Domer (2014) suggests, there has not been a clear international agreement on its definition and this led to many subjective and individual perspectives on it (Domer, 2014) The governments are some of the main participants in developing

affordable housing and they determine it by different levels of eligibility of a household, their income, their social status, and other elements (Susilawati & Armitage, 2010). Thus, this section limits the range of the research to the official definitions from various countries and the European Union. Also, it investigates how the Romanian government defines affordable housing. Therefore, as a foundation for this investigation, it is necessary to understand these different interpretations of the topic and compare it to the one in Romania. This helps to contextualise the study and narrow its focus.

As Vale (2014) implies, the general understanding is that affordable housing refers to the type of housing that is available to households with medium and lower incomes, but which at the same time, is of a fair and satisfactory standard of quality and location (Vale, 2014). In addition, for it to be considered affordable, the housing costs do not have to be over the capabilities of the inhabitants (Vale, 2014). The typology of dwellings varies and can include, subsidised housing, temporary or transitional housing, shelters, mortgage bought or private rented homes (Jones et al, 1997). One of the main reasons for choosing Australia, UK, and USA, is that these countries focus on providing affordable housing and have certain eligibility systems (Domer,2014) Beside this, they are from different areas of the world, but have similar political systems (Tsenkova and Polanska, 2014). The European Union represents the common interests of 28 countries, including Romania. The Union also targets the aspects of housing and affordability and some of these states, such as Poland, The Czech Republic or Bulgaria, have similar political, historical, and social contexts (Tsenkova and Polanska, 2014). Whilst other countries from around the world also have affordable housing policies and schemes, their context may differ from the one in Romania (Domer,2014). That is why, Australia, UK, USA and the EU were chosen 2.1.1. Australia

According to the Centre for Affordable Housing, the expression is sometimes used in connection or mixed with the idea of social housing but they are not synonyms (CAH, 2015). The Australian government states the difference and explains affordable housing as dealing with a bigger range of households than the ones included in social housing: “Households do not have to be eligible for

social housing to apply for affordable housing, though people who are eligible for social housing mayalso be eligible for affordable housing properties”(CAH, 2015, para. 2). This means that the income of a household is still an important aspect for the eligibility but it depends more on the needs of each household

2.1.2.

United Kingdom

In the UK, the line between the two ideas is not very clear. The term affordable housing is explained by the UK government as “social rented, affordable rented and intermediate housing, provided to eligible households whose needs are not met by the market” (Department for Communities, 2012, para.39). Eligibility is determined with regard to local incomes and local house prices; and it is an important focus for the government as it appears 23 times in the National Planning Policy Framework in the UK (National Planning, 2012)

2.1.3.

United States of America

In the USA, the term relates firstly with a certain threshold, which is referred as “affordable rent burden” (U.S Department of Housing, 2016). If a family spends more than 30% of their income on housing, it is considered in need of affordable housing (U.S Department of Housing, 2016). Mortgage and rent are also included in the costs. As in many other countries, the US government only considers middle or low income families as potential users for this type of housing (U.S Department of Housing, 2016). In order to connect the issue to certain situations, a second eligibility level applies and is related to the local median income, which is different in each state. (U.S Department of Housing, 2016)

2.1.4.

European Union

In the European Union, the definition for affordable housing given by Eurostat, the entity responsible with statistical information for the EU, is associated with a household burden of housing costs (Housing Europe, 2015) If more than 40% of a household income is spent on any housing cost, then it is considered overburdened (Pittini, 2012). Although there has been an intention of a unified description of the topic, in their 2015 report, Eurostat concludes that the housing situation is unique to each country and there cannot be a single approach (Housing Europe, 2015) Moreover, the report proves that there are huge

discrepancies even at regional levels as there is higher demand for housing in urban areas and lower in the rural ones (Housing Europe, 2015). This sustains the idea that the problems and solutions for affordable housing are contextual and should be analysed in this manner. Despite this, there have been global events that have affected the affordability of housing at large scales (UN Habitat, 2011) The Housing Europe report also argues that the 2009 Global Economic Crisis hugely affected the European housing industry and especially the affordable sector (Housing Europe, 2015). The report shows that the situation has not improved since then and the effects are: There are more homeless people in Europe today than 2009 and there is a higher demand for affordable homes in the Union than the governments can provide. (Housing Europe, 2015) 2.1.5. Romania

In Romania, the term affordable housing is not a separate topic to social housing. It does not appear in the government official policies and there are not income thresholds relating to what the affordable housing costs should be. According to the National Housing Agency, there are programmes that deal with specific groups of people such as housingfor young adults, young specialists or the Roma communities but they are not defined or included in affordable housing schemes but rather additional social programmes (NHA, 2016) The state owns the entire social housing and is just 2.3% of the housing stock (Valceanu & Suditu, 2015). It is the lowest in the European Union and far from the amount available in more developed countries such as UK, France, or Austria where they range from 10% to 30% (Housing Europe, 2015). This may indicate a certain issue that is contextual to Romania.

In conclusion, Romania does not have an income threshold or policies about affordable housing. The topic cannot be interpreted through the lenses of the policies developed by other governments, because their approach is different to the Romanian one As presented above, among the countries analysed, there is a disparity when talking about the income thresholds that define the need of affordable housing. At the same time, there is a similar approach towards dealing with the possibilities of each household by considering local incomes and house prices The lack of clear policies and thresholds on this issue, makes it difficult to

conclude what would be the limits of the concept of affordable housing in Romania. Moreover, the small extent of the social housing stock in Romania compared with other European countries indicates a unique situation. Therefore, this requires limiting the focus on one of the groups that is affected by the lack of adequate housing (Housing Europe, 2015). In the case of this research it is the young adults between 18 and 35, as the Romanian government defines this age group (Housing Europe, 2015).

2.2. The Housing Crisis from Communism to Democracy

To understand the present conditions of affordable housing in Romania, there is a need to comprehend the historical and cultural context and its influence on the housing situation. The aim of this section is to examine the policies and actions that two political ideologies (communist and democratic) have taken in relation to housing. Between 1945 and 1989 Romania was under a communist regime and after the Revolution from December 1989 has been ruled by democratically elected parties (Tismaneanu, 1998).

2.2.1. Communism

After WWII, a great housing crisis hit the country. Panaitescu (2012) states that this happened because of several different issues, different from other European countries such as Germany, USSR, or Poland (Panaitescu, 2012). He says that Romania was not hugely affected by the destructions of war but the increasing industrialization resulted in a massive migration from rural to urban areas (Panaitescu, 2012). In the first part of the new regime, between 1945 and 1969, private owners built 80% of the housing (NIS, 2010). Drazin (2005) indicates that this was contrary to the aim of the communist party (Drazin ,2005) He suggests that the communist ideology was against the expression of individualism which is linked with owning a home and thus, any official construction of individual housing was discouraged and even banned in the cities Drazin (2005) The actions of the communist government also support this idea From 1970 until 1989, the state constructed 84% of all the new housing (Soaita, 2014) Many of the projects were massive collective housing blocks of flats that still stand today (see Figure 1). Additionally, at the beginning of the regime many private housing owners,

especially the former bourgeoisie, were forced to give their properties to the state to be redistributed by the government (Soaita, 2014)

Iacoboaea (2006) suggests that because the state owned all the housing developments, economic efficiency was the rule and not affordability which would mean balancing needs, quality and efficiency (Iacoboaea, 2006). She implies that this was proved by the small sizes of most of the apartments and the use of the same project typology all over the country in order to lower the costs (Iacoboaea, 2006) Vîrdol et al (2015) also states: “The fever of economies at the beginning of the years 1980 also affected the sector of housing, construction standards and costs of housing erected by the state, being modified. […] It was encouraged the valorisation of all areas” (Vîrdol et al, 2014, p.214). This resulted in low quality apartments and a division of space of just 8 to 10 square meters per person (Soaita, 2014). The space was less than 1/3 of the developed countries that had around 35 square meters per person (UN, 1996) Despite the aggressive attitude of the communists against private housing, a limited number of unofficial, small, and poor quality dwellings were still built by low income families at the outskirts of the cities and in the rural areas, even after 1970 (Panaitescu, 2012). In the 1970s there were some attempts by the Romanian architects to design better housing which would allow the users to reorganize the

space after the apartments were built, despite the strict laws and regulations (Panaitescu, 2012). These types of initiatives may suggest that the ideas of individualism and ownership did not disappear from the Romanian society during the communist regime

The housing crisis attenuated by the mid 1970 but another one started in 1980 and the harsh construction regulations became even worse (Panaitescu, 2012) In the 1980s, the regime was building around 141.000 apartments each year which was close to the average of other European countries (Dan,2003) Dan (2003) points out the aim of the communist party was to move most of the population in the cities and by the 1990 to have 90% of the inhabitants in apartment blocks (Dan, 2003) The communist constitution established that every Romanian should have adequate housing and had to be provided by the government (Tsenkova, 2014). This could be interpreted as a measure to build affordable housing for the majority of the population but Dan (2003) describes the government actions as “bribing the citizens for their obedience” (2003, p.15) Therefore, it could be said that through the housing provision, the government was trying to control the population. The reality, as the research shows, was that what the regime considered adequate was a low standard of quality and small spaces (Soaita, 2014). These actions have had impacts that are still seen today and some of them are, overcrowding, lack of basic utilities, and an excess of housing that cannot be used (Soaita, 2014). These issues will be detailed in section 2.3 The Housing Situation Now.

2.2.2. Democracy

After the regime fell in 1989, the new political leadership had to reorganize and redefine many aspects of the Romanian constitution and laws (Alpopi, 2014). The right to housing was ratified in the Romanian laws in 1996, and in 2002 more regulations were added to fight against and limit social exclusion (Alpopi, 2014). Through these laws the acceptable principles of comfort and quality of life regarding all types of houses, rented, social or private were established (Alpopi, 2014). Thus, the right to housing was recognised in Romania as a human right. Also, as Romania is part of the UN and European Union, it adhered to their processes to fight the crisis housing which affects the entire globe (United

Nations, n.d). One of the reports by the UN Habitat (2011) approximates the number of people living in poor conditions in cities around the world, at around 1.1 billion (UN-Habitat, 2011). The right of housing includes many aspects, not just the right of owning a dwelling. For example, the essential services such as utilities, water, electricity, and safe communities are included (United Nations, n.d) Besides being legislated, it became an official strategic area of national interest and a major political objective (Alpopi, 2014) The housing market during the transition period from communism to democracy was affected by two main policies: privatisation and restitution.

2.2.3. Privatisation and Restitution

The TENLAW (2014) report shows that after 1990 around 2.2 million dwellings were sold to their occupants at very low rates which solved the transition from a nationalised system to a private one (TENLAW, 2014). Privatisation, was at that moment, an affordable solution and it is different to what is happening today with the housing market as there is a clear shortage that affects especially three groups: the population at risk of poverty, young adults, and the mobile population (TENLAW, 2014) The transfer of property from the state to private individuals had negative and positive consequences. From the TENLAW (2014) and Habitat (2015) reports a list of these consequences can be compiled:

The numbers of socialhouses decreased (Habitat, 2015). The government was not able to provide social homes because of the economic transition from state controlled economy to capitalism (Habitat, 2015). The state before the revolution invested 8.7% of the state budget into housing and afterward it was less than 1% (Iacoboaea, 2006). This is linked to what the Habitat for Humanity (2015) report refers as replacement value (Habitat, 2015). This represents the money gained from selling the homes, which is reinvested into building new social or affordable homes and balance the needs of the housing stock (Habitat, 2015). In Romania through privatisation, these costs have never been covered, as it was not intended to have this sustainable aspect (TENLAW, 2014). The ideology behind privatisation was that the users had the right to their homes (TENLAW, 2014).

The new proprietors had to deal with the maintenance of the bought homes The housing was of low quality and people could not afford the housing costs. (Habitat, 2015)

The new buyers were the old tenants and the way they became owners was accessible (TENLAW, 2014). They had to pay 10% of the government appointed price for their accommodation in advance and afterwards several instalments which were loaned by the state (TENLAW, 2014)

The new owners benefited after the rise in inflation in the early 1990s which lowered their loan massively (TENLAW, 2014)

Other effects identified by Dan (2003):

The fast change from one system to another created a vacuum of policies and laws regarding housing standards and maintenance (Dan,2003).

It lowered the availability of inexpensive rent (Dan,2003)

The Habitat for Humanity report concludes that “It was a profitable measure for the tenants at that moment but it created a disadvantage for the next generations” (Habitat, 2015, p. 90). This is also supported by the Eurostat (2013) statistics that show that the young adults and the poor are the most affected by the lack of housing (Housing Europe, 2015). Tsenkova (2014) indicates that at that moment, it was the logical measure in order to promote the economic stability of the individual and of the new capitalist market (Tsenkova, 2014) She also shows that it was a system implemented by most of the former communist countries and on short term, it helped the population survive the transition (Tsenkova, 2014) Beside privatisation Romania also implemented restitution. This gave the former owners, whom the communists confiscated their homes, the right to retake their properties and evacuate the tenants (Tsenkova, 2014) Although it was considered the just measure, it was highly abused of, because of corruption, and many were left without their homes and without any affordable solutions (Tsenkova, 2014).

This section has shown that in the last 80 years Romania has been through several housing crises and that the communist control has had an impact on the housing stock. The methods used by the communist regime to deal with the housing needs, have affected the way Romanians think about housing in general and especially affordability (Panaitescu, 2012). The regime policies and

ideologies have sent the housing market, after the revolution, in a different direction than the one in the western countries. While in the west, the housing market was mainly under the free market system, in Romania, the transition after 1989 has been marked by two main policies, privatisation and restitution, both with negative and positive impacts (Tsenkova and Polanska, 2014). Their effects are still being seen in the housing sector after 25 years and theyhinderthe access to affordable housing, especially for the younger generation (Habitat, 2015)

2.3. The Housing Situation Now

The previous section presents an overview of the housing history in Romania and how two different political ideologies have dealt with the issue of affordable housing. This section focuses on the present situation by examining new and updated statistical data, reports, and journals Firstly, it briefly presents some effects of low quality housing and lack of housing. Secondly, the section analyses Romania`s housing statistics in comparison with other European countries This helps to understand the data and the magnitude of the issues. The section analyses some of the present and past elements that influence the affordability of housing and details the main ones such as the costs, overcrowding, the housing quality, the distribution of ownership, the housing market and social housing.

The Council of Europe development Bank (2016) estimates that around 123 000 young adults under 35 need affordable accommodation in Romania (CEB, 2016). Most of them live with their parents, in overcrowded conditions because their income does not allow them to buy or rent a home (CEB, 2016). Young adults are considered one of the vulnerable groups of people affected by housing exclusion which generates social exclusion and decreases the quality of life (Pittini, 2012). Lack of housing and low quality housing are important factors that affect the health and everyday life of the individuals, and are under the danger of “environmental hazard". (Avramov, 1995, p.68) This environmental hazard causes psychological stress, developing deficiencies, social segregation, physical health issues and sometimes it is associated with the inability of accessing social services such as healthcare, education, or cultural and leisure facilities (Avramov, 1995). Habitat for Humanity (2015) report also mentions the

there are advantages related to an adequate amount of affordable housing which lead to social cohesion and economic progress (Habitat, 2015). Thus, understanding the factors that lead to this housing shortage has many benefits.

The data from the Habitat for Humanity report links the problem of affordability in Romania to two present issues which are: the rising prices for homes and the decrease of social housing construction (Habitat, 2015). The report shows that this results in a large part of the population living in bad housing conditions and deprives them of the ability of providing other necessities such as food, healthcare or even clothes (Habitat, 2015).

The matter is also connected with the past; with the communist legacy and the number of housing that was built between 1945 and 1989. For example, studies show that the housing policies of the communists impact the housing occupancy today (Soaita, 2014). The amount of housing built by the communist regime represents 75% of the entire existing stock ,while only 11% is represented by the post communist housing and 14% by the pre communist (Soaita, 2014). In addition, according to the National Statistics Institute report from 2010 there are 2.7 million flats built by the communist government which are still inhabited and account for 37% of the used housing in Romania (NIS, 2010). After 1989, the rate of housing construction slowed drastically (see Figure 2)

Some other variables have also affected the affordability for young adults (Housing Europe, 2015). One of them has been the value of the Romanian currency, which was very unstable in relation to foreign currencies, such as the Euro or the Swiss franc and increased the costs of the mortgages (Housing

Europe, 2015). This factor has deepened the debt of the younger population and lowered their buying capacity (Housing Europe, 2015)

There are several major issues that influence the affordability of housing in Romania, such as: the housing costs, overcrowding, poor quality dwellings, imbalanced home ownership, the house market, and a low number of social housing. These will be detailed in the next sections.

2.3.1. Housing Costs

Between 1993 and 2007 many people moved to the villages and in the surrounding areas of the cities because of the housing costs (TENLAW,2014). In the EU, the average housing costs between 2004 and 2014 raised by 3.6%, while in Romania, it did by 8.9% (Eurostat, 2015). In the last 10 years, Romania has had a GDP growth of 3.4 percentages and in 2016 it is forecast at 5.2%, which is one of the highest in the EU, the average being 1.7% (Economic and Financial Affairs, 2016). It is possible that this growth and the increasing need of adequate housing (see section 2.3) have led to an increase in housing costs

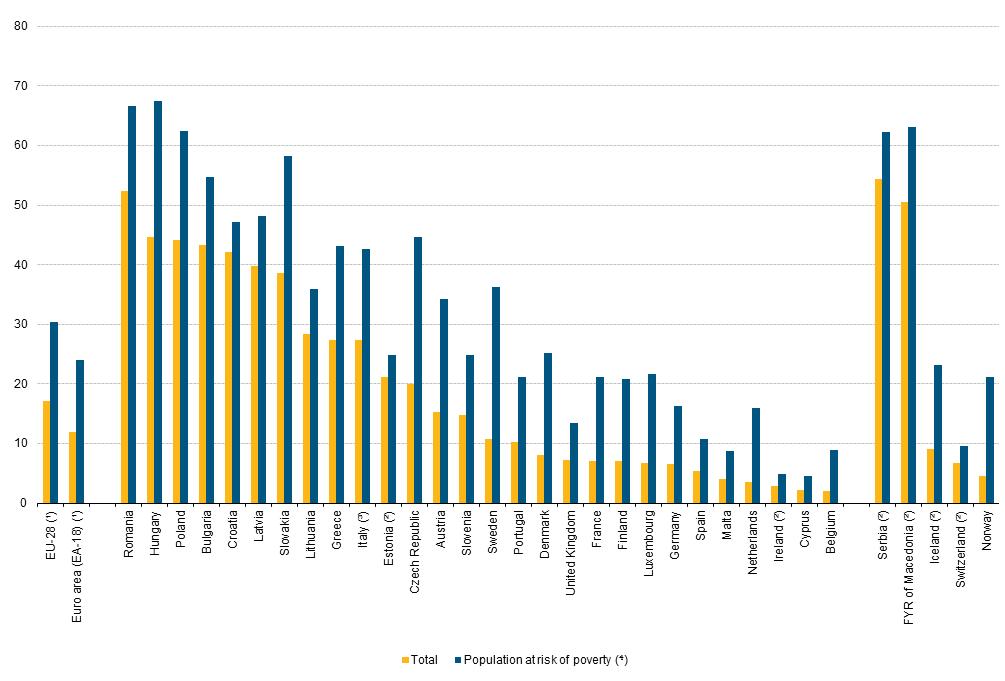

There is a discrepancy found in the data when it comes to the housing costs overburden The data from 2015 shows that the European tenants, who pay the market rent price, are prone to use more than 40% on the housing costs (Ciora, 2015). According to Ciora (2015), 26.2% tenants that rent in EU are affected, whilst only 6.8% of home owners deal with this issues (Ciora, 2015). Taking this in consideration, it would be expected that in Romania because 96.4% of the people own their home (see Figure 6), there would be a low level of housing costs overburden. On the contrary, Romania is in the first 5 countries in the EU as percentage of population being overburden, with 15.1% (see Figure 3) The Eurostat statistics show that 11.2% of the EU population used 40% or more of their disposal income on housing, which is considered overburdened (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Overburden rate Source: Eurostat (2014)

One possible explanation for these results could be the inequality in wealth distribution The Eurostat (2012) data reveals that in Romania the poorest 10% of the population, have an income share of only 1.4%, which is the lowest in the EU, whilst the richest 10% have 20% of the share. (Eurostat, 2012)

2.3.2. Overcrowding

Overcrowding has been observed to be one of the common negative legacies of the regimes in former communist countries (Tsenkova and Polanska, 2014) Romanian housing sector still suffers high levels of overcrowding even after many years from the revolution (Soaita, 2014). As seen in the 2014 Eurostat statistics, Romania has the highest level of overcrowding in the whole European Union with more than 50% of the population having to deal with this issue (Eurostat, 2014) This results in around 10 million people being affected. In addition, if we are to look at the population at risk of poverty, 67% are affected by this phenomenon (see Figure 4). For this specific population, only in Hungary the situation is worse (see Figure 4). A census from 2002 showed that 1/3 of the urban housing stock and 1/4 of the rural stock were overcrowded (National Institute of Statistics, 2002) Around 3 million Romanians use less than 6 m2 of space and another 3 million between 6 and 8 m2 (Soaita, 2014). This is less space than even what the communist regime was providing for to the population (see section 2.2.1).

Figure 4 Overcrowding rate. Source: Eurostat (2014)

The 2011 Population and Housing Census showed that there is a stock of 8,450,942 dwellings and there were 7,086,394 households (NIS, 2011) These results would seem to suggest that there is an oversupply that could be used. Actually, there is an imbalance given by the household’ demands and their geographical distribution (Iacoboaea, 2014). The oversupply consists majorly of unfinished, low quality or inadequate housing (Iacoboaea, 2014). Even more, there is still, even after many years from the end of the Communist regime, an effect on the amount of floor space per person. The NIS 2011 census has revealed that in Romania there are 24.5 m2 per person, which is two thirds of the European average of 38 m2 (TENLAW 2014) The overall conditions in the European Union regarding overcrowding have improved since 2005 but the Eurostat statistics reveal that Romania`s situation has not improved significantly (Housing Europe, 2015).

2.3.3. Housing Quality

The European Commission has declared that lack of housing is the principal root of social exclusion and poverty and that bad quality housing has similar effects (Pittini, 2012). Although the EU has better quality dwellings compared to other

parts of the world, in 2009, around 30 million citizens of the Union were living in inadequate accommodations (Alpopi, 2014) The main elements used to assess the quality of housing are the basic utilities. The households, which do not have running water, central heating, or a bath, are being affected by housing deprivation (Housing Europe, 2015). A household is considered under severe housing deprivation if it is affected by overcrowding and other poor quality utilities (Housing Europe,2015). Severe housing deprivation level in Romania is the worst in the whole EU (see Figure 5). Although it has improved between 2013 and 2014, the difference to the European average is significant (see Figure 5) Around one in four persons in Romania is considered to face severe housing deprivation, while in Finland or the Netherlands, less than 1% of the population has this problem (see Figure 5). The absence of basic utilities is a major issue especially in the villages where 1/3 of the dwellings have no shower or bath, nor indoor toilet (Housing Europe,2015). The 2011 census results found out that only 65.1% of the homes have a sewage system and 66.7% of them have running water (NIS, 2011) In comparison, the average in the EU is that of around 80% of accommodations that have running water and a bath (Iacoboaea,2014) In conclusion, the reports and statistics seem to agree that the housing quality in Romania is of a low standard, at the moment.

2.3.4. Home ownership and the house market

Romania has the highest percentage of population that own their home, 96.4% (see Figure 6) This fact has some unfavourable ramifications as Ciora (2015) mentions: “A higher home ownership is associated with negative effects like: lower labour mobility, longer commutes, and fewer new firms and establishments “ (Ciora, 2015, p.127) According to the National Institute of Statistics, the private rental sector is around 2% of the housing stock but other experts approximate that the real number is around 11 12% of the dwellings (TENLAW 2014). It is believed that this inaccuracy may be caused by those who rent and by the owners, because they do not declare their housing status in order to avoid taxes (TENLAW 2014) Romania`s young adults have a small share of the house stock, which is around 12% (Habitat, 2015). This is in agreement to what was mentioned in section 2.2.3 about the younger generation being disadvantaged in acquiring homes (see section 2.2.3).

The price increase for housing may have also accentuated this imbalance between generations The house prices and the demand highly increased before 2007 EU accession (Eurostat, 2016). After 2009, the economic crisis lowered the property value by 20.62% in the first year but recovered by 2014 (Eurostat, 2016).In the second quarter of 2016 the home prices are rising again by 5,6% (IMF, 2016). It could be possible that the prices will continue to rise as the GDP

is growing (see section 2.3.1). This may accentuate the young adults inability of acquiring new accommodation

A surprising finding is related to the distribution of population by dwelling type. As mentioned in section 2.2.1, the communist regime aimed to move most people in apartments and they built mainly just blocks of flats (see section 2.2.1). Although they had this programme, in 2014, the population distribution reveals that 54% of Romanians live in detached houses (see Figure 7). This could be linked to the quality of the apartments and to the property restitution that happened after the revolution (see section 2.2.3).

It is believed that an element that has slowed the construction industry and housing market, was the steep decrease in population (Habitat, 2015). Between 2004 and 2014, it was down by 7.3% and the main issue has been the migration to other countries but also a low birth rate (Habitat, 2015). Compared to its neighbours it has the highest rate of depopulation (Habitat, 2015). Further in depth governmental research may clarify this situation and the real numbers of the housing market could result in different policies and actions to manage the affordability for young adults.

2.3.5. Social housing

The Romanian government defines social housing, in the Housing Law no. 114/1996 as a dwelling that is assigned by the state to an individual or a household that cannot afford the costs of owning or renting a home (MDRAP, 2016). The social houses are rented by their occupiers who receive financial help from the state (MDRAP, 2016). The rent is much lower than the market value and is calculated at 10% of the yearly household income, and paid monthly (MDRAP, 2016). Local authorities manage all social homes (MDRAP, 2016).

A study from 2005 shows that, in Romania, from 1000 applications for social housing, only 165 are solved. (Constantinescu and Dan, 2005) In Romania, only 2.5% of the population rents subsidized homes, whereas, in the EU the average is around 17% (Constantinescu and Dan, 2005). This results in almost 85% of unresolved cases and shows an inefficiency of the local authorities in dealing with this issue.

Local authorities are the only investors in social housing in Romania (MDRAP, 2016) This is also the case for other European countries such as Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovakia, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia (Tsenkova & Polanska, 2014). All these countries have similar historical context, especially the fact that communist regimes ruled them until 1990 (Tsenkova and Polanska, 2014). This indicates that the way the communist regimes dealt with housing (see section 2.2.1), may have influenced the local authorities in having monopoly over the social housing. This is contrary to other countries from Europe with different historical contexts For example, the Housing Europe Report from 2007 shows that in western European countries, in the 20th century, because of urbanization and changes in the industries, private investors were the main developers of social housing (Housing Europe, 2007). The report indicates that companies and charities tried to provide housing to a large mobile population of workers (Housing Europe, 2007) Habitat for Humanity 2015 study shows that today, there is an increasing number of public-private partnership models related to affordable housing all around the world (Habitat, 2015). These providers are non profit or minimum profit associations that use a different mix of financing methods, such as subsidies, the private market and funds or guaranteed loans (Habitat, 2015).

In Romania, there are not any public private investments in affordable or social housing (Habitat, 2015)

In conclusion, the housing situation now in Romania is in a crisis that affects young adults (section 2.3). Lack of housing and bad quality housing affect the user’s health and development (section 2.3). There are present and past factors that accentuate this crisis, such as: the rising prices of homes and the communist large accommodation stock (section 2.3). Some of the major findings are:

The costs related to housing are increasing and 15.1% of Romanians are overburdened, which is higher than the European average (section 2.3.1)

There are around 10 million Romanians that live in overcrowded conditions, the highest percentage in the EU (section 2.3.2.). There are more than one million unusable dwellings in Romania, due to low quality. Six million people use less than 8 m2 of space compared to the 38 m2 EU average (section 2.3.2.)

Severe house deprivation is the worst in the EU and only 66.7% of homes have running water (section 2.3.3)

The rising house prices have made it more difficult for young adults to buy a home and they have a small share of the housing stock, 12% (section 2.3.4)

The local authorities are inefficient in providing social housing, with 85% of applicants not receiving one. There are not any private investments in affordable or social housing. (section 2.3.5)

2.4. Summary

In conclusion, the literature review sets out the basis for the research. The first section, Defining Affordable Housing reveals a key point:

Romania does not have policies or thresholds regarding affordable housing like other countries have. (section 2 1.5)

The second section, The Housing Crisis from Communism to Democracy points out several important aspects:

The research indicates that the communist regime built a large part of the existing stock but it was of low quality. Economic efficiency was the rule and not affordability, which was seen in the small division of space per person of just 8 to 10 m2. (section 2.2.1)

In democracy, Romania ratified the right to housing and established some principles of comfort and quality of life. (section 2.2.2)

After communism, the government enacted two policies: Privatisation and Restitution. (section 2.2.3)

The reports and statistics suggest that privatisation had negative consequences such as: decrease of social houses, vacuum of policies and laws regarding housing and people could not afford the housing costs (section 2.2.3). This “created a disadvantage for the next generations” (Habitat, 2015, p. 90)

The third section, The Housing Situation Now, examines new statistical data and several findings emerge:

There seems to be a housing crisis that affects young adults in Romania (CEB, 2016). Many live in overcrowded conditions and are in danger of environmental hazard (section 2.3).

The housing costs are increasing and 15.1% of Romanian are overburdened. (section 2 3.1)

There is a high level of severe housing deprivation (section 2.3.3)

The analysis seems to show that young adults are disadvantaged in acquiring new homes (section 2.3.4)

The statistics indicate that the local authorities are not able to provide enough social housing for the demand. (section 2.3.5)

2.5. Research question, aim and objectives

The dissertation seeks to address the issues around affordable housing in Romania in the present day and looking forward. As limited time and resources are available for this research, the scope of the dissertation is limited. It therefore focuses on one city in Romania. Ploiesti is a city of 224 406 inhabitants that since the revolution, according to the UN (2016), has had a continuous decline in population (UN, 2016). According to the Agency for Regional Development (2013) report, its proximity to the capital, the rising home prices and housing costs have led many young adults to move to cheaper areas, in Bucharest or to emigrate to other countries (ARD, 2013) Ploiesti is a typical city, from Romania, that must manage depopulation, especially among the younger generation (ARD, 2013). The focus of the dissertation is on young adults because the literature review reveals that this particular age group in Romania is in need of affordable housing (section 2.3) Thus, the research question that arises is: What issues do young adults in Ploiesti, Romania face in accessing affordable housing ?

The aim of the research is to identify some of the issues related to affordable housing that young adults encounter in Ploiesti, Romania and how their specific situation compares to the national figures. This will be done by completing three objectives:

1. To review the current government programmes aimed at young adults’ access to housing.

2. To gather primary data on young adults in relation to their housing issues in Ploiesti

3. To draw conclusions as to the housing issues young people in Ploiesti face