A report into the first 1000 days of life in marginalised groups in the United Kingdom

April 2022

Introduction

Dame Lorna Muirhead, Commission ChairPoverty and its dire effects prevents people from having the life many of us take for granted, and those wide ranging detrimental effects are well documented in this report.

Since we are all born unknowing, we rely totally on those who care for us to feed, love and nurture us; to keep us safe, to educate us and give us aspirations for the future so that we have a chance of becoming thriving citizens. If those caring things had not been done, we may have been prevented from reaching our potential. In turn, we may have children of our own and raise them as we have been raised so, whether positive or negative, the cycle is repeated. Any one of us could have been born into poverty to parents whose energy is largely subsumed with just keeping their head above water and not able to pay attention to child development. There is great need to break this cycle by parenting the parent.

Nonetheless, things are not all bleak. We live in a society which gives attention to such matters, however inadequate those efforts are. Hopefully, reports like this give policy makers a steer to the way forward.

Commissioners were indebted to those who need the assistance of the services provided, who took the time to tell us about their lives. They were also greatly impressed by the enthusiasm and commitment which resource-starved professionals demonstrated in their endeavour to do their best for those families for whom they are responsible. The do have a sense of frustration about lack of staff and money, but as the poet William Morris writes, they are not ''beaten by the muddle". The service users are also thanked for their faceto-face contribution in helping us compile this report.

Acknowledgements

Liverpool John Moores University thanks wholeheartedly all of the commissioners, who with an already busy workload, contributed their time and effort so generously.

We also offer our thanks to everyone who came forward to provide evidence for us. Some informants were well prepared in advance, others heard about us through publicity on local radio and television and others still just dropped in to see what was going on. We appreciate the health and social care staff as well as those from the third sector, who took some time out from busy jobs to tell us what was happening on the ground. Special thanks are offered to the service users who described some very difficult personal situations for themselves, in the hope of making things better for others in similar conditions. We hope we have been able to represent your voices well. and we are happy to donate 50% FOC, so £27.50 per unit for half of

Executive summary

Liverpool Health Commission had its genesis in autumn 2018 as a tool to help implement the university’s strategic vision of being a pioneering, modern civic university delivering solutions to the challenges of the 21st century. The Liverpool Health Commission’s aims were to conduct an independent investigation and critical analysis of current experiences in the first 1000 days of life in marginalised groups and to make grounded contributions to debates at national level that will seek to assist policymakers at all levels who are searching for meaningful, practical solutions to the problems and challenges facing the population and health sector across the UK in the 21st century. We established that the main focus of the commission would be on poverty as it is that which underpins many of the disadvantaged groups we discussed The commission consisted of 12 commissioners, as well as a chair and an academic lead. It was formally launched in May 2019. with hearings initially in six locations around the UK, each of which had high levels of child poverty from November 2019, until September 2020. As well as ensuring a geographic spread the commission chose to avoid places which had been the subject of other recent major inquiries.

The final choices therefore were:

Morecambe, a former seaside resort in north-west England; Middlesbrough in north-east England, a previously heavily industrialised town, was a centre for iron and steel works and shipbuilding; Clacton-on Sea, in south-east England, originally a stone age settlement and a popular seaside resort in the early 20th century Derry/Londonderry, the second largest city in Northern Ireland that lies very close to the border with the Republic of Ireland; Neath/Port Talbot in south Wales located about 10 miles to the east of Swansea with an industrial past is similar to that of Middlesbrough, but economically it also has a large rural population stretching up a number of valleys; Lanarkshire in south-west Scotland comprising north and south Lanarkshire counties is an inland area which was dominated by coal mining and associated iron and steel works until the 1980s; Merseyside was the final area to be considered, after all other evidence had been collected because it was the “home” of the commission.

Located in north-west England, it is a port area which was extensively bombed in World War II. It has subsequently been amongst the most impoverished areas of England. Its health outcomes and life expectancy are significantly worse than the whole of England.

The main report was drafted in February 2021 and findings from around the UK were used to inform the final week of evidence gathering in the Merseyside area in September 2021.

A critical overview of the existing literature was conducted to inform the commission’s approach drawing on relevant reports from all four UK countries as well as international agencies such as those of the United Nations. Initial contact was made with each area through the local council offices where officers responsible for child health services in the area agreed to support the project by assisting with provision of venues and providing further contacts in the health and council services as well as voluntary sectors and service user groups. We did not attempt to speak to managers but rather we chose to engage with people providing the hands-on services as well as those receiving them.

Findings

• Finance:

o Difficulties have been experienced by people who are not made aware of eligibility for certain benefit and who are struggling to make ends meet.

o The introduction of universal credit and subsequent changes to it have caused considerable confusion amongst both service providers and users.

• Housing

o Homelessness, housing provision and temporary accommodation are often inadequate for families with children in the first 1000 days of life

o Landlords are frequently not held accountable for their actions

• Local service provision

o Families struggle to maintain a good diet because of a lack of nearby providers of nutritious and affordable food.

o The reduction in Children’s Centres has led to social isolation as many families cannot afford the cost of public transport to their nearest centres

o Public transport is often inadequate especially in, though not limited to, rural areas

• Mental health

o Intergenerational cycles of poor mental health are being perpetuated

o Mothers suffering from mental health problems face difficulties in seeking help to reach out for help and there are insufficient trained carers to meet their needs

o Early detection and prompt management of infant mental health problems is rarely possible

• Infant nutrition

o As well as cultural resistance to breastfeeding public attitudes prevent some women from trying to breastfeed their babies

o Inaccurate information is often spread about breastfeeding on social media sites and bottle feeding still advertised on television

• Particular vulnerable groups

o Refugees and other migrants are frequently separated from their cultural groups and are unable to communicate and so obtain essential services.

o Babies who have been hospitalised do not always receive follow up services

• Overall

o Families who are drug/alcohol dependent are not always recognised and appropriate action taken in regard to their babies

o Domestic abuse is widespread with affected families not always able to remove themselves from danger

o Conflicting advice is often received from different agencies

o The involvement of multiple professionals can preclude the establishment of trusting relationships between service users and providers

Recommendations

1. Noting the often repeated mismatch between the wishes of professionals to use education to improve families’ circumstances and the ability of the families to respond, further exploration of more effective interventions is merited;

2. Community participation, and involvement of voluntary agencies should be maximised to tailor support and services around the individual needs of families.

3. Joint agency working remains a significant challenge to achieve and should be addressed as a matter of urgency to improve support for service users and outcomes.

4. Communication methods between staff and service users should be reviewed to ensure they are empathetic, effective and appropriate to meet needs.

5. Mobile services such as those provided in some rural areas bring services to the more remote communities. They could be used in urban areas where transport and access are barriers to service users.

6. Family focused approaches would ensure that awareness of the needs in the first 1000 days is not simply the responsibility of the mother. Families and extended families could be included in being supported to care for the baby

7. Policy changes are required to offer universal, long-term, appropriate support to families in need in the first 1000 days.

Conclusion

By interviewing front-line staff and service users the commission was able to understand their actual lived experiences. Many of the findings reflected failings that had been perpetuated over many years, which have been reported in a number of earlier reports and academic articles. However, the commission also found largely unreported successes throughout the country, which merit inter regional-sharing and adaptation to different settings and which are discussed later in this report. It is encouraging to see such initiatives, which, with sufficient and sustainable funding and support can benefit the future

generations. Although across the UK there is a policy commitment to improve child health outcomes it is evident that urgent action is needed to reduce poverty with much more investment and service development to achieve the desired goals.

A view from a community leader

Les Nicoll BEM Essex Fire and Rescue Service

I am a Community Builder for Essex Fire and rescue service (ECFRS), serving over 50 years as a firefighter and community worker.

Last Sunday I had a weekend with my children and grandchildren celebrating my 70th Birthday. Most of my time was spent being a Pirate, a ghost, a monster, a bank robber, a wrestler and a trampoline for my four beautiful boisterous Granddaughters. exaggerating my skills, making them scream and squeal, feeding their varied imaginations. Each of them healthy, well educated, able to relate to each other and enjoy adult company. Each of them, planned, anticipated, conceived out of love to parents who whilst not rich certainly all had jobs owned nice houses in good parts of the town. From conception each of these girls had all received good quality food, fresh vegetables, were not allowed sweets sugary drinks or exposure to cigarette smoke. Parents paid for them to go to nursery school, meeting and interacting with other children. Spending much happy time with loving adult family members.

My Role in the ECFRS involves me working in a very different environment. I spend a great deal of time working in Britain’s most deprived town. In an area of around 1,000 homes each tiny ex holiday lets, creating a shanty town, with more that 60% of its population receiving benefits. There is no heart to the village, Schools are a bus ride away, likewise Doctors, the nearest large supermarket is over 3 miles away, no football teams, no clubs, very large dependency on alcohol, drugs, foodbank donations, derelict buildings, rubbish strewn streets, running with vermin, slum landlords. Poor infrastructure, third and fourth generation poverty and unemployment. Two or three underfunded charities working incredibly hard swimming against the tide trying to make a difference. No money, no food, no help no opportunity, no way out. We continue to watch TV documentaries about this and other poor areas, read countless articles, with a not in my backyard amusement and interest, like the people Visiting Bedlam in the 19th century.

Would my/our grandchildren growing up in this environment thrive? Would they be as healthy? Would their imagination and social skills be as developed? Would their education offer limitless opportunities? We all know the answer.

Those of us reading this report are either already or are potentially people in power, with intelligence, influence people living my life and even better.

Will you nod your head and agree with some of the conclusions in this large and very well researched report? Will you quote some of the statements in your speeches, use them in your newspaper, working reports, university dissertation? We could of course use our privilege, our power, our time, and intelligence to make a difference? BUT WILL WE?

Chapter One: Liverpool Health Commission

Introduction

Liverpool Health Commission had its genesis in autumn 2018 as a tool to help implement the university’s strategic vision of being “a pioneering, modern civic university delivering solutions to the challenges of the 21st century” and its stated belief “in the power of sharing expertise, and of people coming together with a common purpose” (Liverpool John Moores University 2017) The Liverpool Health Commission was to be tasked with carrying out an independent investigation and analysis of particular public health or health care policy issues with the goal of making practical and realistic recommendations. Its broader aim was to make grounded contributions to debates at national level that will assist policymakers at all levels, who are seeking meaningful solutions to the harsh challenges facing public health and health care in the UK in the 21st Century.

The topic of marginalised women and children in the first 1,000 days of life (the time from conception to the end of the second year of infancy) was selected as the first commission by the executive leadership team Although there has been attention focused on the first 1000 days for several years by policy makers, we were concerned to explore not only what problems existed in this period of life but how those marginalised people had benefitted from some of the policy changes in recent years. Not only was this considered appropriate for the City of Liverpool due to its high levels of deprivation, but was also considered to be of wider national interest because its consequences are known to impact negatively on human growth and development at the crucial stages of early life.

Commission focus

As stated above, the first commission focuses on the topic of marginalised women and children in the first 1,000 days of life. In present times, taking this period to start from conception may be controversial, but by so doing it presents a unique window of opportunity. It is during the approximately 270 days from conception to birth that foundations for optimum health, growth, and neurodevelopment across the lifespan are established (United Nations 2017) Despite the majority of pregnant women in the UK seeking advice in the first trimester of pregnancy, it is often women from the many marginalised groups in our society who cannot or do not seek antenatal care or advice, and whose children may not benefit from the most optimal start in life

Large regional variations of poverty and infant morbidity and mortality exist within the UK. A recent KPMG report for the Liverpool Health Partnership

highlighted the harsh differences between the north and south of England and a recommendation was made for urgent academic work in four key areas, the leading one of which was identified as maternal and child health (Liverpool Health Partners 2017) Similar disparities are also found across Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Maternal and child health concerns are therefore a key priority at different levels of health and social care across the UK. The causes and effects of the disparities are manifold and likely to vary across different parts of the country. They may include alcohol and drug dependency, a disproportionate number of migrants, people who only have a basic level of the English language or an above average teenage pregnancy rate. Such a list is not exhaustive but a catalyst for the start of the commission’s working life. Thus the Liverpool Health Commission focuses on this important area which has profound relevance regionally and nationally. Additionally, it addresses the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 1-5, all of which are directly related to women and children’s health, bringing this topic into the dimension of global good health and the right to health (United Nations 2015).

Commission aims

The aims of the Liverpool Health Commission were:

• to conduct an independent investigation and critical analysis of current experiences in the first 1000 days of life in marginalised groups;

• to make grounded contributions to debates at national level that will seek to assist policymakers at all levels who are searching for meaningful, practical solutions to the problems and challenges facing the population and health sector across the UK in the 21st century.

Commission structure

The commission consisted of 12 commissioners, as well as a chair and an academic lead. The 12 commissioners were appointed by the LJMU ViceChancellor and all have held executive-level roles in public or professional bodies or come from a relevant professional or academic field (see Appendix 1)

Inquiry timeline

The commission was formally launched in May 2019. The opening hearing took place in November 2019, with the others (see chapter 3) following fairly quickly thereafter. The penultimate hearing was due to take place in April 2020 but was postponed because of Covid-19 and was finally held in September 2020 via Microsoft Teams. More information on the gathering of evidence and its analysis may be found in Chapter Three. The main report was drafted in

February 2021 and findings from around the UK were used to inform the final questions used to gather evidence in the Merseyside area in September 2021.

Inquiry report

This chapter has introduced the report. Chapter Two outlines key literature which has underpinned the commission’s work and places a strong emphasis on grey literature primarily from the UK, but also from international reports such as those issued by UN agencies and major charities. Chapter Three provides a detailed overview of how the commission collected its evidence and fulfilled its aims as well as outlining some of the limitations. Chapters Four –Nine synthesise findings from each locality visited by the commission and Chapter Ten offers concluding remarks. Appendix 2 reports on the schedule of visits.

Chapter Two: context of the commission

Introduction

A critical overview of the existing literature was conducted to inform the commission’s approach. It is beyond the scope of this report to synthesise and critically evaluate the numerous academic articles on the first 1,000 days of life published in peer reviewed journals. Instead, key reports from the United Nations, which have shaped initiatives in the UK, were reviewed as well as UK specific reports from a range of sources and are discussed in relation to the work of the commission.

United Nations reports

The United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals were launched in 2015, following approval by the UN General Assembly (A/RES/70/1a). This collection of 17 goals are intended to be a global blueprint to be achieved by 2030 (United Nations 2015). While most could be considered by the commission, goal number 10 which aims to eliminate inequalities, is the most relevant to this commission’s work.

Before the term “first 1,000 (1,001) days” became popularised, the World Health Organisation (WHO) published a comprehensive report on essential nutrients for the developing child (World Health Organisation 2013). It highlighted interventions for pregnant women such as daily supplementation with iron and folic acid, intermittent iron and folic acid supplementation, vitamin A and calcium supplementation and reaching optimal iodine nutrition for non-anaemic pregnant women. Aimed at the global community, these recommendations apply to UK based pregnant women, particularly those disadvantaged by a sub optimal diet. The report discusses nutritional care and support for pregnant women during emergencies, a topic that has re-emerged during the Covid-19 pandemic. It also discusses nutrition of children in the first six months of extrauterine life and, drawing on evidence from several systematic reviews and previous UN reports, promotes a policy of six months exclusive breastfeeding. This remains an area in which the UK’s performance is poor and has been discussed at all commission hearings.

Launched in January 2017, the UNICEF publication “Early moments matter” catalysed the “first 1,000 days” initiatives throughout the world (United Nations 2017). Like the above WHO report, it focused on breastfeeding. However it also highlighted issues such as paid parental leave, high quality, accessible child services and grants for all families with children i.e. family friendly policies. Different countries have used this report as a springboard for developing their own policies in different ways. The UK’s response mainly

focused around the “Baby Friendly Initiative” which, since 1994, has been promoting breastfeeding in an effort to increase the currently poor rates throughout the country (UNICEF United Kingdom 2021).

This initiative works with public services to provide families with effective infant feeding support, enabling them to make an informed choice about feeding, get breastfeeding off to a good start, overcome challenges and feed their babies responsively. It includes giving information about skin- to-skin contact, understanding their babies’ cues, how to respond to them and implementing safe sleeping practices.

However, UNICEF UK cautions that offering effective support to parents is only possible when practitioners have sufficient knowledge and skills. When practitioners lack this knowledge and offer conflicting information, they can discourage mothers so undermining confidence in their parenting decisions. Research has found gaps in knowledge, skills and attitudes of health practitioners, resulting in poor provision of information and support to mothers (Maxwell 2019).

As well as knowledge about breastfeeding, UNICEF UK authors report that health professionals need the skills to communicate with mothers in unambiguous, beneficial, appropriate and non-judgemental ways.

A study on access and barriers to provision of maternal health published by the European Parliament (European Parliament 2019) suggested that the major barriers to provision of sexual and reproductive health services are (pp. 33-37):

• language and communication with health professionals;

• health professionals’ lack of experience in dealing with ‘difference’;

• structural inequalities;

• organisational barriers;

• culture and faith;

• mental health,

• fear and social stigma.

While this study refers to the EU Member States, including the UK at that time, in their totality, the same barriers are still to be seen in the UK and have been to the fore during the commission’s lifespan.

Reports from the UK

Turning to relevant reports from the UK, the devolution of various responsibilities from the Westminster parliament to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales means many health -related reports discussed are specific to one of the four nations. The Rowntree Reports on poverty are an exception and will now be considered in detail before moving on to other relevant reports.

The (Joseph Rowntree Foundations 2017) detailed report on poverty in the UK showed that consistent poverty rates are highest among families with young children (p. 3). A third of children lived in poverty from the beginning of the 21st century, falling by 15% from the period between 1994/95 and 2004/05 to 28% of children. The child poverty level fell to its lowest (27%) in 2011/12 but began to rise again after that, reaching 30% in 2015/16.

The 2021 report (Joseph Rowntree Foundation 2021) states that 14.5 million people in the UK were living below the poverty line before the onset of coronavirus, equating to more than one in five people. They provide details of overall trends in the different countries (p. 18):

• England: poverty levels have worsened, raising from 21.3% in 2011/122013/14 to 22.3%. Within England, London has the highest poverty rate, which is broadly stable over time. All other regions show a flat or worsening position except the East Midlands.

• Wales: poverty levels have experienced very little change, albeit rising marginally from 22.7% in 2011–12 - 2013/14 to 22.8%.

• Scotland: lower levels of poverty (currently 19.2%) worsening from 17.8% in 2011/12 to 2013/14).

• Northern Ireland: poverty levels have improved, lowering from 20.8% in 2011–12 - 2013/14 to 19%.

While the 2021 report primarily focused on “in-work poverty”, this undoubtedly affects children. The authors note the steady increase in child poverty, with children constituting a vulnerable group disproportionately likely to be pulled into poverty. The authors continue by observing that vulnerable groups already struggling to stay afloat have borne the brunt of COVID-19’s economic and health impacts. Particularly relevant to the commission’s work, these include:

• part-time workers, low-paid workers and workers in sectors such as accommodation and food services where there are much higher rates of inwork poverty;

• Black, Asian and minority ethnic households;

• lone parents – mostly women, many of whom work in hard-hit sectors –who are more reliant on local jobs and more likely to have struggled with childcare during lockdown.

Low-income families with children have been particularly affected by COVID19. Research carried out on behalf of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and Save the Children (Maddison 2020) found that six in ten families with children in receipt of either Universal Credit or Child Tax Credit have had to borrow money since the beginning of the pandemic. Many of these families have relied on not only on formal lending such as credit cards, loans or overdrafts

but also payday loans. According to (Porter 2020), families who receive benefits are twice as likely to have borrowed money from family and friends as families who do not.

Lone parents continue to have the highest in-work poverty level of all family types and are disproportionately affected by barriers that prevent them escaping in-work poverty. They are more likely to be women, working in a lowwage sector, working fewer hours, and restricted by childcare and transport. The pandemic is likely to have had a big impact on people in this group because of the sectors in which they work, and their ability to work depends on childcare, which may have been unavailable during the national pandemic restrictions In-work poverty is also higher for black, Asian and minority ethnic workers than white workers, and is highest for Pakistani and Bangladeshi workers (Joseph Rowntree Foundation 2021). Consequently, ethnic minority families have also been hit hard by COVID-19. Compared with white families, they are more likely to have experienced an income loss and to have cut back on essential spending (Maddison 2020).

Another relevant recent UK wide initiative is that of the Royal Foundation. The Foundation commissioned a large study in 2019 to investigate attitudes surrounding child-rearing from conception to five years in all four UK nations. It comprised a “face to face” study of 3733 parents followed by two online surveys, a qualitative study of a sub-sample of 40 parents drawn from the face to face survey and an ethnographic report of 12 families and four community leaders. Their main conclusions are clustered into three key areas (p. 47):

1. The importance of promoting education and dissemination of evidence on the primacy of the early years to parents, parents of the future and the whole of society.

2. The need to cultivate and sustain more support networks for parents to enhance their mental health and wellbeing.

3. The need to encourage society as a whole to be more supportive of parents, carers and families in the early years.

Perhaps the most significant finding - related to the first of these themes - was that very few participants recognised or understood the importance of the brain’s development in the first 1,000 days and the impact this would have on the whole life of the child. The need for trust to be established between parents and service providers was a further key finding, one of relevance to the present commission’s work (The Royal Foundation 2020).

Another UK wide charity, the WAVE Trust, focuses on tackling the root causes of trauma related to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which are endemic in society. WAVE’s most recent report (WAVE Trust 2018) reviews global

systemic and methodological approaches taken to protect children from the threat of severe and multiple disadvantages caused by ACEs. While targeting the age group from 2-18, rather than the first 1000 days, some of their seven key messages are relevant to the present commission’s work as these identify the systems which are most likely to bring about improvements in the services for the most disadvantaged children and young people. One of these key messages states “parental dysfunction is a major cause of childhood ACEs; levels of youth and adult dysfunction are higher in the UK than other western European countries” (p. 16). It particularly targets teenage parents and recommends that services focus efforts on the disadvantaged wards that have ten times the levels of teen births found in the non-disadvantaged.

The final key message from the Trust states that “a national shift to a userfocused, trauma-informed care system characterised by ACE-awareness, followed by adoption of a pedagogical approach across all aspects of children and family services, would protect against severe, multiple disadvantage” (p. 5). WAVE recommend flat organisational structures such as already implemented in parts of Wales and Scotland as they have been effective in improving inter-agency collaboration, streamlining and simplifying working and reporting methods and replacing traditional silo cultures with effective approaches.

England

In 2009, the Government launched the Healthy Child Programme (HCP), with the aim of improving outcomes and reducing inequalities through a combination of universal provision and targeted support. The HCP is central to the delivery of preventative and early intervention services for children and families in England. Since its inception, there have been several key reports that directly address its work. The Marmot review (Marmot 2010), which focuses on reducing health inequalities in England, reported that its centre point was a “life course perspective” noting that “disadvantage starts before birth and accumulates throughout life” (p. 20). Drawing on evidence from previous reports, academic papers, statistical data and interviews, the review urged that action to reduce health inequalities had to start before birth and be followed throughout the child’s lifetime, as that is the only way in which the close links between early disadvantage and poor outcomes are able to be broken. For this reason, the committee recommended that giving every child the best start in life be its highest priority recommendation. A follow up was published in 2019, in which the recommendations for the best start in life were very similar ie:

• Increase levels of spending on early years and as a minimum meet the OECD average and ensure allocation of funding is proportionately higher for more deprived areas.

• Reduce levels of child poverty to 10 percent – level with the lowest rates in Europe.

• Improve availability and quality of early years services, including Children’s Centres, in all regions of England.

• Increase pay and qualification requirements for the childcare workforce (Institue for Health Equity 2019)

The Marmot review set in train a series of actions and has formed the basis for subsequent reviews of the first 1,000 days, all of which acknowledge the critical importance of this time. The major examples are presented below.

In 2014 a cross party manifesto (Leadsom, Field et al. 2014) stated that:

“[pregnancy] can also be a chance to affect great change, as pregnancy and the birth of a baby is a critical ‘window of opportunity’ when parents are especially receptive to offers of advice and support” (p. 5).

The manifesto noted that maternal stress is likely to affect the fetus or baby negatively, therefore, ensuring that the brain achieves its optimum development and nurturing during the peak period of growth in the first 1,001 days is crucially important and enables babies to achieve the best start in life. They further note the vital need for good bonding that will lead to better and longer lasting attachment between the baby and its primary caregiver(s). Since Bowlby’s work in the 1960s on attachment (Bowlby 1969), successive studies have shown that a baby’s social and emotional development is strongly affected by the quality of the attachment (Zeanah, Berlin et al. 2011)

At the time of the report’s publication, Leadsom et al noted that babies are disproportionately vulnerable to abuse and neglect than older children. They estimated that 26% of babies (198,000) in the UK were living within complex family situations of heightened risk where there are problems such as substance misuse, mental illness or domestic violence, with 36% of serious case reviews involving a baby under one.

The report’s main recommendation was that the best chance to turn the effects of negative factors around occurs during the first 1,001 critical days. They stated that every child deserves an equal opportunity to lead a healthy and fulfilling life, and with the right kind of early intervention there is every opportunity for secure parent infant attachments to be developed. They further noted that, in accordance with attachment theory, at least one loving, sensitive and responsive relationship between a baby and an adult caregiver teaches the baby to believe that the world is a good place and reduces the risk of them facing disruptive issues in later life. The final recommendation of the

manifesto states that, it is imperative that how children are raised is guided and influenced by the attachment principle and its evidence. However, attachment was a theme that informed the work of (The All Party Parliamentary Group for Conception to Age 2 2015) Their report states that groundwork for good citizenship occurs in the first 1,001 days as “ A society which fails to deliver it generates enormous problems” (p. 3). Its main focus is perinatal mental health and it notes that the cost of omitting to deal adequately with perinatal mental health and child maltreatment are high, closely linked and largely avoidable. Furthermore, the authors also stress the vicious circle where one generation of drug abusers, for example, passes the problem to the next generation, meaning the resultant social disruption, inequality, mental and physical health problems and cost perpetuate and multiply.

The report outlines two main aims:

1. Creating children who at the end of their first 1,001 days have the social and emotional resources which constitute a strong foundation for good citizenship.

2. Preventing high intergenerational transmission of disadvantage, inequality, dysfunction and child maltreatment.

It then outlines nine recommendations with potential approaches that could be taken to achieve them emphasising the importance of an inter-agency working and a national strategy, under the supervision of a Minister for Families and the Best Start in Life:

A more recent cross-party report led by Sarah Wollaston (Committee 2019) focused specifically on the first 1,000 days of life. Its data were collected in 2018 and comprised 86 written submissions, 80 posts on an onIine forum, three sessions of oral evidence taking, three focus groups and a one site visit to Blackpool. Both the written submissions and oral evidence were provided from health service providers and third sector organisations. The organisation chosen for the online forum was Mumsnet, a popular choice for mothers experiencing difficulties, from which the commission heard directly from parents about their experiences of pregnancy and early parenthood, as well as the services they used during this time. While aims of this commission were broadly similar to that of the present one, our focus has been more aimed at collecting evidence from the people providing hands on services and those who receive them.

As well as acknowledging the first 1,000 days of life as a critical phase during which the foundations of a child’s development are laid, the cross-party report

(Committee 2019) noted that exposure to stresses or adversity during this period can result in a child falling behind their peers developmentally. Thus, they conclude that intervening more actively in the first 1,000 days of a child’s life can improve children’s health, development, life chances and make a fairer, more prosperous society.

The committee focused on a broad definition of health, noting that enhancing the ability of services to support and empower parents and families to take care of themselves and their children is vital, but not sufficient. Other stressors such as poverty, poor housing and unstable employment also act against the ability of parents and families to create a safe, healthy and nurturing environment for their children. Its findings noted significant variations in the way local areas prioritise and support families in the first 1,000 days. Similarly, it found significant variation in staffing numbers, skills and the level of contact with families within the health services.

The committee also pointed out that improvements in service provision will only provide a ‘sticking plaster’ if they are not targeting the conditions in which some of this country’s poorest children live. As with previous reports, the government was urged “to lead by developing a long-term, cross-government strategy for the first 1,000 days of life, setting demanding goals to reduce adverse childhood experiences, improve school readiness and reduce infant mortality and child poverty” (p. 3) They expand on this by saying that the government should “coordinate the work of multiple departments and agencies; provide strategic direction to local areas and hold them to account; and ensure the issue remains a priority and continues to attract resources” (p. 27). They go even further by recommending that the Minister for the Cabinet Office should be given responsibility to lead the strategy’s development and implementation across government, with the support of a small centralised delivery team thereby placing it at the highest level of government.

Ten years after its inception, the committee called for the Healthy Child Programme to be revised, improved and given greater impetus, recommending that it begin before conception to come into line with the first 1,000 days initiatives. This would involve extending home visits by Health Visitors beyond the age of 2½ years, becoming more family focused, and ensuring that children, parents and families experience continuity of care during this critical period. Such an approach would also identify children and families who need targeted support earlier. In many cases women seek help during pregnancy even if they are not registered with a GP, so this time may offer such an opportunity.

The most recent report comes from the UK government’s commission, chaired by Andrea Leadsom, into the first 1001 days. The aim of the review was “to

improve the health and development of babies in England” (H.M. Government 2021) p. 7. The review comprised a questionnaire, to which there were 3,614 responses and virtual visits to London, Essex, Devon, Leeds, Manchester and Newcastle on Tyne. Additional information was collected through engaging with the online platform “Mumsnet” and a twitter feed.

1. The major focus of the review was to ascertain how families could be better supported. Two major themes were identified: each with three action areas. Ensuring families have access to the services they need comprised: Seamless support for families: a coherent joined up Start for Life offer available to all families, a welcoming hub for families: Family Hubs as a place for families to access

2. Start for Life services and the information families need when they need it: designing digital, virtual and telephone offers around the needs of the family. Ensuring the Start for Life system is working together to give families the support they need included: an empowered Start for Life workforce: developing a modern skilled workforce to meet the changing needs of families, continually improving the Start for Life offer: improving data, evaluation, outcomes and proportionate inspection and leadership for change: ensuring local and national accountability and building the economic case.

Scotland

The Scottish government’s “early years framework” (Scottish Government 2009) drew on evidence from several relevant disciplines to inform its policy of giving all children the best start in life. The framework defined early years as pre-birth to the eighth birthday. The report acknowledged that while early intervention has relevance to a wide range of social policies, it is in the earliest years that the best opportunities often arise. The four principles of early intervention the authors identified were:

1. all children should have the same outcomes and the same opportunities;

2. children at risk of not achieving those outcomes should be identified and steps taken to prevent that risk materialising;

3. where the risk has materialised, effective action must be taken;

4. the government’s agencies should work to help parents, families and communities to develop their own solutions, using accessible, high quality public services when required.

The report acknowledged that its ambitions could not be achieved without change and identified 10 elements of transformational change, all of which are relevant to the present commission’s work. The authors also put a renewed

focus on zero to three as the period of a child's development that shapes future outcomes.

A secondary analysis of data from the Scottish Household Survey (Barens and Lord 2012) used seven key indicators to define disadvantage as experiencing low income, “worklessness”, no educational qualifications, overcrowding, ill health, mental health problems and a poor neighbourhood. These criteria are of interest to the present commission. This report indicated that at the time of reporting there were approximately 24,000 households with children who had four or more of the seven listed disadvantages, the majority being in the south-west of the country.

A follow up report published by the government in 2019 formed phase one of the wider study ‘Scottish Study of Early Learning and Childcare’ (Scottish Government 2020). This report investigates whether increasing the hours of government funded early learning and childcare for children aged three to five (and some eligible two-year-olds) improves outcomes for children and parents, particularly those who at risk of disadvantage. The data showed that a majority of two-year-old children attending day-care did not have the crucial life skills and qualities they need if they are to grow up being healthy and valued members of society.

Other reports in Scotland mainly focus on regional initiatives but the maternalinfant survey (Scottish Government, 2017) investigated Scotland’s position in relation to achieving optimal health and nutrition for mothers and infants prior to, during and after birth. The report acknowledged that the diet and nutritional status of mothers before and during pregnancy and the subsequent nourishment received by infants is associated with the long-term health of the population. It additionally recognised the increasing importance of maternal preconception health and the influence this has on the likelihood of an infant later developing chronic diseases later in life. The survey was carried out at approximately 20 weeks of pregnancy, at eight-12 weeks and eight-12 months after giving birth. Its aims were primarily to investigate the adjustments women made to their diet prior to and during pregnancy, their plans for infant feeding and how they actually fed them. Additionally, they were asked about the “Healthy Start” programme and how they would use their vouchers. As each time point surveyed involved a different cohort of women it was not possible to form a longitudinal picture.

Wales

A national consultation by the Welsh Assembly on the first 1,000 days took place from 2016-2017. Several of the submissions made to the inquiry provide a wide ranging picture of the situation. Both NHS Confederation (Welsh NHS

Confederation 2016) and Public Health Wales (Public Health Wales 2016) note the inequalities throughout the country and the difference in outcomes for babies born in the highest and lowest social classes.

The NHS Confederation report particularly comments on the effectiveness of the “Flying Start” programme in the health boards where it is available. Conversely, Public Health Wales takes a broader approach, highlighting the prevention of adverse childhood experiences through provision of universally accessible preventative health services. In terms of possible solutions, it referenced the “triple p”, (Positive Parenting Programme) in Ireland that is delivered to three to seven year olds with good results, and recommended that the evaluation tools used could be replicated in areas of Wales which have adopted the Flying Start and/or Families First programmes.

Wales has had a focus on early years policy for many years and revised its Healthy Child programme in recent years (Welsh Government 2020). This programme has three levels of health prevention activity for the first 1000 days of life: universal, enhanced and intensive. The key health professional is the Health Visitor who interacts with the family from early pregnancy until the child is of school age at whatever level is necessary.

The current programme of the Welsh Government (Welsh Government 2021) highlights substantial work on improving services for children especially those that are ‘looked after’. It includes funding childcare for more families where parents are in education and training, continuing to support the flagship Flying Start programmes, preventing families breaking up by funding advocacy services for parents whose children are at risk of coming into care. They also seek to provide additional specialist support for children with complex needs who may be on the edge of care, explore radical reform of current services for looked after children and care leavers, eliminate private profit from the care of looked after children, fund regional residential services for children with complex needs ensuring their needs are met as close to home as possible and in Wales wherever practicable and strengthen public bodies in their role as ‘corporate parent’.

Northern Ireland

Amongst the recommendations from a 2013 research based paper (Perry 2013) two are of immediate relevance to the present commission:

• The fragmentation of responsibility for early years provision and childcare across departments and arm’s-length bodies;

• Areas of overlap in Learning to Learn and Towards a Childcare Strategy and the extent of joint working on these policies.

A later briefing paper emphasises the need for improved maternal health as well child health services (Perry 2016).

The current “Sure Start” programme offered in 38 localities of Northern Ireland supports children in disadvantaged areas from pre- birth until four. Since its inception in 2016, three national evaluations have taken place, the most recent in 2020. The latest review initially asked for areas to nominate themselves on the basis of their positive outcomes and, from the nominations, selected projects representative of a cross section of geographical areas, size and range of lead and accountable bodies and Child Care Partnerships for inclusion. A small inspection team then visited the sites and identified strengths and weaknesses of each site (Education and Training Inspectorate (Northern Ireland 2020).

Relevant key strengths were identified as a more consistent and effective culture of reflection and self-evaluation, the positive impact of the services and programmes, the highly effective practitioners, from varying professional disciplines and effective inter-disciplinary team collaboration and sharing of information to identify and follow up on the needs of families and children at the earliest stage.

A well-established charity, “Early Years”, is also active in the country, promoting high quality care for children up to 18 years. Their 2019 annual report show the charity, as well as being active in providing early childhood education, has a strong advocacy and lobbying role, with its basis in the UN Charter for the Rights of the Child. It acts as the lead partner in six of the Sure Start Programmes ensuring a link between education and health (Early Years 2019).

Conclusion

In an area where there have been many active partners involved with service delivery as well as numerous academic researchers at work, there are a plethora of publications. We have chosen to give some background from those we consider to be most relevant in informing the approach adopted by the present commission.

Chapter Three: The Liverpool Health Commission’s approach

Introduction

Informed by the numerous reports on the first 1001 days, the Liverpool Health Commission set out to explore current experiences in local areas to inform decision makers locally and nationally.

Refining the topic of investigation

After discussion by the Commissioners, it was agreed that we could never have an exhaustive list of marginalised groups, so we decided to leave the question open as to what constituted “disadvantage”. We concluded that the main focus of the commission would be on poverty as it is that which underpins many of the disadvantaged groups we discussed (Joseph Rowntree Foundations 2017). Following these discussions, as stated in chapter 1 the aims are:

• To conduct an independent investigation and critical analysis of the significant health area of the first 1000 days of life in marginalised groups;

• To make grounded contributions to debates at national level that will seek to assist policymakers at all levels who are searching for meaningful, practical solutions to the harsh problems and challenges facing the health sector across the UK in the 21st century.

Locations for collection of evidence

The areas of multiple deprivation in the UK and areas with high levels of child poverty were sought using data from the Child Poverty Map of the UK report (End Child Poverty, 2016). The most recent map is shown in Fig 1 below showing that areas which the commission visited are still amongst those most deprived in the UK.

Note: After housing costs. Map and data use 2019 local authority boundaries. Reprinted from UK Poverty 2022. By Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2022. Copyright 2022 by Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Reprinted with permission.

Other factors to be taken into consideration were to have sites have a geographic spread and to avoid places which had been the subject of other recent major inquiries. The final choices therefore were:

• Morecambe, a former seaside resort in north-west England which catered mainly to families from Yorkshire, who took advantage of the rail links

developed in the mid 19th century to link the county with the new harbour. Its decline as a holiday destination began in the late 20th century when its two piers were damaged and demolished and new attractions failed due to poor financial planning. Its current population of about 35,000 comprises mainly retired people and young families approximately 15% of whom are considered to be living in poverty. It is a predominantly white town with only 5% of the population being of black or other minority ethnic groups. A few services for women, children and families are provided in the town of Morecambe for its residents and those of nearby villages but the majority of them are based in the nearby county town of Lancaster. An ambitious plan for regeneration of the area primarily through tourism but including digital health and liveability plans was launched in 2017, but due to Covid, much of it is currently on hold. Maternal and child health services are provided by Morecambe Bay NHS Trust, which was subject to an inquiry into maternity services in 2016 and continues to be under CQC scrutiny.

Figure 2 Morecambe Bay Action Plan

Reprinted from Costal Community team draft 2017-22(Morecambe Bay Coastal Community Team 2017)

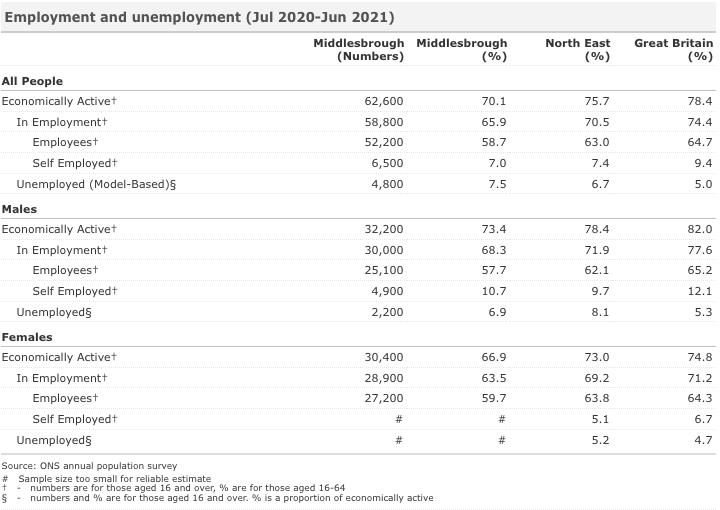

• Middlesbrough in north-east England, a previously heavily industrialised town, was a centre for iron and steel works and shipbuilding. As such it was an attractive area for inward migration, mostly from elsewhere in the UK, seeking manual work. In the second half of the 20th century most of this work disappeared, leaving an above average unemployment particularly amongst second and third generations descended from these immigrants. The main employers now are the James Cook University NHS Trust and Teesside University. Despite these two large employers, figure 3 depicts high numbers of unemployment and low numbers of employment in Middlesbrough from July 2020-June 2021 thus indicating high levels of income deprivation.

Employment and Unemployment (Jul 2020-Jun 2021)

Note: For Middlesbrough. Reprinted from Labour Market Profile- Middlesbrough. By nomis Official Labour Market Statistics, n.d, www.nomisweb.co.uk/reports/lmp/la/1946157060/report.aspx#tabempunemp Copyright n.d. by Crown Copyright Reprinted with permission.

• Clacton-on Sea, in south-east England, was originally a stone age settlement and continued to thrive in Roman and medieval times. It became a popular

seaside resort in the early 20th century as it was in easy commuting distance from London by rail. It reached its peak in the decade following World War II. Now it remains popular for day visitors. Figure 4 indicates the positive economic impact tourism has had on the district of Tendring and the number of full time jobs tourism has brought to the area. Despite this, Clacton-on Sea is still considered a deprived area, and Jaywick which lies on Clacton-on Sea’s outskirts is consistently ranked one of the most deprived areas of the UK. It has a small maternity unit and many community services delivered jointly by the Tendring District Council, Essex County Council and Colchester NHS Trust.

Note: Reprinted from Tourism Strategy for Tendring 2021-2026 . By Tendring District Council, n.d. https://tdcdemocracy.tendringdc.gov.uk/documents/s33219A8%20Appendix%20Draft%20Tourism %20Strategy%202021%202026.pdf. Copyright 2022 by Tendring District Council. Reprinted with permission.

• Derry/Londonderry lies in the west of Northern Ireland and is its second largest city. It lies very close to the border with the Republic of Ireland. Its strategic location has seen its continued use as a port for several centuries. It was also a major centre for textile manufacturing until the 1970s and a small remnant of this remains. The “Troubles” of the late 20th century are thought to have originated here with widespread violence from the 1970s until the 1990s. Even after the Good Friday agreement some sectarian violence lingered but with

considerable investment by local, national and UK governments and international companies leading to employment it is considered a safe and stable place. Despite this, figure 5 outlines that there were low employment rates in the Derry City and Strabane District council from 2009-2018. Thus, indicating high levels of income deprivation. It has a major maternity unit at Altnagelvin NHS Trust and provides services to the surrounding communities.

Note: DCSDC is an abbreviation of Derry City and Strabane District Council Reprinted from Employment. By Derry City and Strabane District Council, n.d.

https://www.derrystrabane.com/getmedia/99ea2a21-86a1-4e4a -bc6a -0e006dc5bb4a/AEmployment-280619.pdf

• Neath/Port Talbot is an area in south Wales located about 10 miles to the east of Swansea and stretches from the south coast to the border of the Brecon Beacons national park in the hills. Its industrial past is similar to that of Middlesbrough, but economically it also has a large rural population stretching up a number of valleys. Its main employer remains the steel works although the workforce now numbers less than 50% of what it was in its heyday. The town houses a small maternity unit, with the main university hospital located in Swansea. A large number of community services are provided for the rural population. One such service is the Flying Start Health Visitors. Figure 6 outlines the number Flying Start Health Visitors allocated to under fours in Neath Port Talbot. It also indicates the high number of under fours that cannot access this service because of where they reside, despite living in income deprivation.

Note: Reprinted from Y 1000 Diwrnod Cyntaf yng Nghastell-nedd Port Talbot/The First 1000 Days in Neath Port Talbot By CymruWellWales, 2017. https://www.derrystrabane.com/getmedia/99ea2a2186a1-4e4a -bc6a-0e006dc5bb4a/A-Employment-280619.pdf

• Lanarkshire is located in south-west Scotland with the health board providing services for both the north and south Lanarkshire counties. It is an inland area which was dominated by coal mining and associated iron and steel works until the 1980s, with the major steel works at Ravenscraig closing in the early 1990s with approximately 10,000 job losses. Unemployment is still high in both North and South Lanarkshire, as depicted in figures 7 and 8 The University of the West of Scotland has one campus in the area. The major maternity and child services are located at Wishaw General Hospital, though the Lanarkshire Area Health Board have satellite services at its other hospitals and a large community-based service.

7

Percentage of Unemployed Individuals in South Lanarkshire

Note: Individuals aged 16-74 in 2011. Reprinted from South Lanarkshire: 2011 overview. By Scotland’s Census, https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/search-the-census#/explore/snapshot Copyright n.d by Crown

Copyright. Reprinted with permission.

8

Percentage of Unemployed individuals in North Lanarkshire

Note: Individuals aged 16-74 in 2011. Reprinted from North Lanarkshire: 2011 overview. By Scotland’s Census, https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/search-the-census#/explore/snapshot Copyright n.d by Crown

Copyright. Reprinted with permission.

• Merseyside was the final area to be considered because it was the “home” of the commission. Located in north-west England, it is a port area which was extensively bombed in World War II. It has subsequently been amongst the most impoverished areas of England. Its health outcomes and life expectancy are significantly worse than the whole of England as depicted in figure 9.

Women and children’s health services are provided by several maternity hospitals of which Liverpool Women’s Hospital is the largest with approximately 9,000 births per year and offering many specialist services. The main children’s hospital, Alder Hey, is a regional trauma centre with in-patient facilities for 300 children. Many community and third sector services are also found in the region.

Note: Liverpool 2019, Reprinted from Liverpool, Local Authority Health Profile 2019 By Public Health England, 2020. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/static-reports/health-profiles/2019/e08000012.html?area-name=liverpool. Copyright n.d. by Crown Copyright Reprinted with permission.

Collecting evidence

Initial contact was made with each area through the local council offices where officers responsible for child health services in the area agreed to support the project by assisting with provision of venues and providing further contacts in the health and council services as well as voluntary sectors and service user groups. There was no initial attempt made to seek out specific organisations, rather to see who would come forward and from there to use a snowball technique to gain further participants. A complete list of participants and organisations providing evidence is located in Appendix 3.

Each visit lasted from between 1.5-2.5 days and sessions with individuals lasted from 20 minutes to 1.5 hours. An open process was initially adopted where those giving evidence were asked to talk about the strengths and weaknesses of the service they provided or received. By the third session an outline of questions used to frame semi-structured interviews was generated from the initial sessions. When the final focus groups were held in Liverpool the questions were very targeted having been generated from the commission’s earlier findings (see Appendices 4 & 5). Publicity was given to the project via local and regional radio and television networks in all locations.

Analysis

As the participants in each venue varied, there has been no attempt to quantify responses. Rather, we have undertaken a qualitative, thematic analysis using an inductive approach (Braun and Clark 2013). All analysis was undertaken manually. Each transcript was read and main themes highlighted. Themes from individuals were then compared within each visit and commissioners who had been involved asked to review and amend them if necessary. Finally, the themes were merged from each site and integrated into one common whole. This inevitably means that something that is particularly important in one single area has been omitted from the data synthesis chapter.

Chapter Four: Findings

This chapter together with those immediately following it takes the reader through the main findings of the commission. Each of these chapters presents some quotes to illustrate the breadth of evidence gathered. The subthemes in each chapter provide some insight into both positive and negative iniatives reported to commissioners. Recommendations are made at the conclusion of each chapter.

Finance

This chapter discusses the financial issues that were raised by staff as significant issues for service users. These factors include Universal Credit, service user budgeting capacity, benefits eligibility awareness, working culture and the perpetuation of a benefits culture.

Universal Credit

Respondents suggested that Universal Credit has been a “nightmare” as "There's a six-week wait." So, if you're a family that's relying on money and have a six-week wait, what are they meant to do for six weeks?” A recent survey of universal credit claimants supports this statement as figure 10 indicates that the majority of claimants surveyed on the Trade Union Congress website were unable to cope with a five week wait.

10

Universal Credit Claimants – Were You Able to Cope With the Five-Week Wait?

Note: Online Survey on the Trade Union Congress website from 19th May-20th of June 2020, Reprinted from Universal Credit and the impact of the five week wait for payment, By Trade Union Congress, 2020, https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/202011/Universal%20credit%20and%20the%20five%20week%20wait%202020.pdf. Copyright 2022 by Trade Union Congress. Reprinted with permission.

Furthermore, increases in service user employment impacts their Universal Credit. For example, a health visitor reports: “I visited somebody this morning who’s had their Universal Credit cut by half because it’s been deemed that

Figure 12: Universal Credit claimants – Were you able to come with the five-week wait? (Trade Union Congress, 2020, p.8).

she’s fit enough to work and her money wasn’t great as it was and it’s gone down to like just under, well around £400 a month and it’s her and a baby. I mean, that is horrendous isn’t it” 1. In this circumstance staff explain that “It’s that fine balance of upskilling parents to a certain level but then not impacting on the money they’ve actually got to spend on their families” 2 .

Budgeting

Respondents highlighted how extreme family poverty is sometimes influenced by service user struggles with personal budgeting: “I've got one mum and she just lives on benefits, but she budgets it so well. You know, she just can do it, where other families just can't” 3. Issues with how professionals saw service user as managing their limited finances were also presented: Despite Family Solutions “going in to help them with budgeting and help them with bills and time to manage. She’s coming to us on a regular basis saying, “I haven’t got any money for food. I can’t feed my kids. So it’s really difficult because we can educate and educate and educate, actually unless they want to participate in that, it’s really hard”. She expressed concern that this is linked to a dependency culture. For example, regarding foodbanks she says we are “creating an issue because then you’re providing food for somebody on a regular basis”, however “We’ve had to do that because there’s a huge need for it” 4

Eligibility unawareness

A further problem is that service users are often unaware of the full extent of financial supports for which they are eligible or are prevented from applying due to psychological barriers of mental ill health. For example someone had “bailiffs banging on his door. He had a young child. And he’d gone into a spiral of depression, because he didn’t think he could get out of that” however “he had such bad anxiety that he had only ever applied for the housing benefit and one of his benefits he had not applied for” because it involved going in person to the job centre. With Home Start help this service user greatly improved in his mental health and gained about “£80 more to live on” and now has “the

1 Neath, fi3d3d14

2 Middlesbrough, fia7cc1e

3 Morecambe, fi03e99c

4 Clacton, fi2b104e

benefits he should have had, but he would never have had if we hadn’t have gone in” 5 .

Benefits’ culture

Problems of Universal Credit, budgeting, and eligibility unawareness feed into the perpetuation of pre-existing benefits’ cultures within communities. Confusion over what service users are entitled to is not restricted to service users themselves, but also staff, unable to keep track of all the changes may give wrong advice.

Respondents acknowledge the existence of a benefits, non-working culture which has been cyclically passed down through families across the generations. Individuals who have had a negative “experience at school, bullying problems, mental health problems” then “leave school early or with no qualifications and very much a low self-esteem or mental health problems. Then obviously they become parents and they've got no confidence in the workplace or no aspirations to work” 6. A voluntary worker says “We need to get the kids to aspire to move away, even if they move away a mile” however “what we're up against is, of course, that mum and dad are partying every weekend…The kids get dragged into this, so then we have children of eight and nine smoking, of 10 and 11 drinking alcohol, sexually active around 13 and 14, and that's because they're just following this trait” 7. This respondent felt that such examples within these communities influences young people’s educational attainment, teenage pregnancy, ill health, personal aspirations and ultimately financial hardship and dependency upon benefits, creating a cycle of generational poverty.

Working poverty

Hard working families often live in poverty because the government provision of 30-hours free childcare a week is determined by the availability offered by childcare providers. This may not match the hours of the mother’s job, so mothers “want to work these hours, but they can't fit the childcare in these hours and it just doesn't work. So, then they'll end up giving up work” 8. Some respondents argued that irrespective of whether one parent is working, both parents work or neither are working, they may be in equal need of financial

5 Clacton, fi07d21c

6 Morecambe, fie072b4

7 Clacton, fief656b

8 Morecambe, fi03e99c

support due to the combination of high childcare costs and low wages. The most likely scenario is “that there's only one parent that's there and they're trying to work. Then, actually, the local economy around here can be quite grey. It's not all payroll orientated” 9. This creates the situation where “We’ve got quite a few parents who are so proud, going out and doing work, but would be far better off, in some instances, on benefits and universal credit” 10, and the realities of working poverty deter many families from working.

Community participation

Recognising the extreme financial deprivation where “poor people don't buy clothes in the charity shop because they can't afford them” 11 but faced with a complete lack of funding respondents have found ways to help with little or no funding. These endeavours acknowledge that people within the community want to help and local charitable or health organisations want to offer support. “With the little charities that I run, I am never short of volunteers. I have loads of people” and “There are loads of these organisations around that are really working hard for the community, and they're run by absolutely wonderful people. Lovely people” 12. Social media was also highlighted as a tool for spreading the word about charitable ventures across the local community, saying “That's my tool. Facebook, by keeping it friendly, people help. If you're not slagging people off, if you're not complaining, if you use Facebook for the tool that it is, it's amazing” 13 .

Income maximisation and staff financial education

A pilot project in which Health Visitors were given additional skills to equip them to discuss financial situations was very successful in maximising serviceuser income and has received national recognition alongside increasing staff confidence in having difficult financial conversations. “Traditionally, health visitors always thought finances weren’t really in our bag” however by incorporating financial questions into health visitor assessments, supporting staff through this development and linking it to a Money Matters pathway, “in the first year of that programme in the first pilot working with 20 families, and in that partnership we managed to secure £100,000 for those 20 families”.

9 Morecambe, fie072b4

10 Middlesbrough, fia7cc1e

11 Liverpool group discussion

12 Clacton fief656b

13 Derry, fi4eb3d5

Such positive results were repeated a second year, showing this is a successful method for “maximising income and lifting some of these families out of poverty” 14 .

Recommendations

• Build on the strengths of community members by involving them in whatever activities possible;

• Ensure programmes are in place to keep health and social care professionals up to date with latest policies to help their clients;

• Have sufficient professional and voluntary help in place to assist community members to manage their financial situation.

Chapter Five: Housing

This chapter discusses a range of issues related to public and private accommodation - noted by stakeholders to have a negative impact upon the health of women and babies during the first 1,000 days - before outlining suggested solutions. Problems present in relation to home conditions, homelessness and inappropriate temporary accommodation, migration and statutory rehousing.

Home conditions

Home conditions drive many mental and physical health determinants seen across the seven localities, with some areas reporting people living in static caravans, chalets, wood houses or beach huts, some of appalling quality. It was reported that landlords buy properties cheaply and place tenants in them without maintaining them to liveable, safe standards. The huts, for example, are extremely small and draughty as they were built only for use as summer holiday homes. These have been noted as negatively impacting on infant development as they are damp, mouldy and “tiny, tiny, little places that they live in. So the amount of time that a child could even have the opportunity to crawl” 15 is very limited. Figure 11 displays the physical and social impact of poor home conditions on individuals/households and neighbourhoods.

Note: Reprinted from Housing and Public Health. By M. Shaw, 2004, Annual Review of Public Health 2004, 25, 397-418. Copyright 2022 by Annual Reviews Reprinted with permission.

Furthermore, tenants are often concerned about raising issues with landlords because “they don’t know how that’s going to affect their tenancy, whether that’s going to cause them to be evicted” 16. Indeed, a voluntary worker describes some tenants being frightened of private landlords as bullies who frighten their tenants. He reports that “there's one landlord who has 160 houses. He rules it with a rod of iron.” 17 . While poor home conditions do impact upon an infant’s development, social services sometimes receive inappropriate referrals for home conditions from health staff who do not understand the extreme poverty of the areas in which they work. One respondent noted that one particular family “are absolutely amazing, they meet all the needs of these children, but, health were complaining because of the conditions of the home. I can’t change that home and it’s because of poverty. It is. She works, she’s on maternity leave at the moment. He works intermittently, with an agency. They’re trying. They’re really trying” 18 .

Homelessness and temporary accommodation

Women and their babies may become homeless and require temporary accommodation due to circumstances such as eviction, poor mental health, fleeing domestic violence or being put out of their family home for becoming pregnant. Figure 12 displays the scale of the issue in England. As clarified by mental health nurses and health visitors, homelessness has a significant antenatal impact upon baby health due to “the stress, the impact of stress in pregnancy and the kind of baby genetics around that…and it is a really unsettling time where they don't know where they’re going to be living”. They say “there should be no rough sleeping at all, everyone should be accommodated. But the reality very often is some of the accommodation that people are offered, they don’t want to take up, and you can understand why”. Much of the accommodation offered is completely unsuitable, and “can be a roof over their head, but very often it’s not much of a home, it’s very cold, money’s tight, it does affect their nutrition” 19 .

16 Clacton, fi73d00d

17 Clacton, fief656b

18 Neath, fi7d080d

19 Lanarkshire, fi870adb

12

Homeless 0-2year Olds

Note: England 2014, Reprinted from An unstable start, all babies count, a spotlight on homelessness, NSPCC. By S. Hogg, A. Haynes, T. Baradon, C. Cuthbert, 2015, https://library.nspcc.org.uk/HeritageScripts/Hapi.dll/filetransfer/2015AnUnstableStartAllBabiesCountsp otlightOnHomelessness.pdf?filename=AA58F75CEDE68892A73FB681FE246B8371684F102152F0AA780A 14959D3BCE5767137B3B2A935011CBAEC3068664FF681AA6D2524E357BAB96C006752CCD756759AD7 7BD1E389823A55CFAAE74B2EE64F46C611AD1724BE1AC500B025490CCB1CD8D9D26B00674E723A731 951BB13FBE2976B714838E6BBB09A9FD539E6F7F27DD3EA0DC4386C6EDAC8F0E252527FCA6955013E8 6EE573EFCAE62FF1D24E6212CD57816E591540239CFA9857B1A6F20F4769801F7402B79F462D525C870 AD9350EF414632F9EE98FD015&DataSetName=LIVEDATA Copyright 2015, by NSPCC. Reprinted with permission.

Mothers with young babies can be placed into temporary accommodation without good health and social supports around them, miles from where their other children go to school. Regardless, they will be “expected to literally walk three miles. If you’ve got, say, a baby and a child at school, it’s just not… Most of us wouldn’t be able to sustain it or do it” and receive criticism when they do

not manage to get there. This results in service users avoiding the services, “because they’re just finding it a real struggle because of all the judgemental attitudes that they’re getting from a range of professionals, really: health, education” 20

Migration and statutory rehousing