urban (inven) tories

Anthropocene / Hinterlands / Planetary

Aburajab Altamimi, Khalid

Cai, Zhilin

Chen, Chengqian

Ding, Jiawei

Dugad, Devendra Hemant

Guo, Senmiao

Lei, Shuyue

Identity Construction: Power Dynamics and Urban Form In Cairo

Always in lines

Folded Right of Urban Residency

Urbanity in Localization of Global Food System

Urban Catalyst: Public Spaces as Parallel Water Management Infrastructures

Upgrading the Chinese Urban Village: Methodological Experiences & Their Impacts

Taikoo Li: A Moveable Feast

Data-Driven Design & Urban Renewal Paradigm in Beijing & Shenzhen

Better Future

Accessible Futures: Speculating Future Realities Through Urban Transit Hubs

Social Urbanism in Refugee Resettlement: Agency and Adaptation of the Existing

Urban Parks as Infrastructure in New York City

Revitalizing Historic Urban Quarters Through Everyday Urbanism

Urban Ecology as Water management

Vargas, Tanner

Cultures, Queerings, Tethers

Computational Urbanism

The Possible Roles of Underutilized Land in the De-industrializing City

The Hidden Landscapes of Conflict

What’s the Role of Government in Singapore’s Urbanization?

Inclusivity of Human-Building Interaction in Urban Design

Parks Under the Perspective of Ecological Urbanism

ACCESSIBILITY

ACUPUNCTURE

ADAPTABILITY

ADAPTATION

AQUIFERS

ARAB URBANISM

BIG DATA

BOTTOM-UP

CLIMATE JUSTICE

COLLECTIVE MEMORY COMMUNITY

COMPUTATIONAL

CONFLICT URBANISM

CONSUMERISM

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

CULTURE CHANGE

DECENTRALIZATION

DESIGN FOR ALL

DIGITAL

DIGITAL PLACEMAKING

EGALITARIAN COMMUNITIES

AGENCY

EMPIRICAL URBANISM

ENERGY FLOW

EQUITABLE

EVERYDAY LIFE

EVERYDAY URBANISM

FLOATING POPULATION

FOOD CRISIS

FOOD PRODUCTION

FORMAL HOUSING

HUMAN-BUILDING

HYDRO-URBAN

IDEALISM

IDENTITY INCLUSIVITY

INDIGENOUS INFORMAL INFORMAL SETTLEMENT

INFRASTRUCTURE

INSTAGRAMMABLE SPOTS

INTEGRATION

INTENSIVE AGRICULTURE

AGRO-INDUSTRY

INTERACTION (HBI)

INTERCHANGE(HUBS)

JUST RESILIENCE

LANDSCAPE URBANISM

MODERN CHINA TEA

MULTIMODAL NETWORKS

OPERATION HISTORIC DISTRICT

URBAN RENEWAL

PARAMETRIC URBANISM

PLANETARY URBANISM

POST-CITY URBANISM

POSTCOLONIAL

POWER

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT

PUBLIC SPACE

PUBLICITY

RE-CONCEPTUALIZE RESILIENCE

REUSE

SMART

SMART CITIES

SOCIAL ECOLOGY

SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE

SOCIAL MEDIA

SOCIAL URBANISM

SOCIO-HYDROLOGICAL

SPACE JUSTICE

SUSTAINABILITY

TECHNOLOGY

TERRAIN VAGUE

THIRD LANDSCAPE

TIKTOK

TOPOLOGICAL TWIST

TRANSPORTATION

UNDERGROUND MILITARY

SHELTER

UNDERUTILIZED LAND UNIFICATION

UPGRADING METHODS

URBAN PARK

URBAN POSSIBILITY

URBAN REGENERATION

URBAN RENEWAL

URBAN SPACE

URBAN VILLAGE

USER EXPERIENCE

VIDEO GAME URBANISM

VULNERABILITY

WATER INFRASTRUCTURE

WILDLIFE

An increasingly urbanized world has presented designers with myriad of challenges. The advent of new technologies, political shifts, climate conditions, economical goals, historical imaginaries, issues of wellbeing and social injustice spurred varying urban responses and approaches forming the modern urban condition.

As urban designers, beyond playing an active role in urban formation, our duty lies in studying, documenting, analyzing, and theorizing these conditions. Additionally, understanding the methods of application and their guiding principles to account for the merits and failures of such conditions is essential to the urban design discourse. What influences the modern city after all? Does the urban form follow a singular set of principles or are we living in confluences of urbanisms?

Looking at urbanism through different lenses, ranging from human focused social urbanism to environmental centered ecological urbanism, the urban condition is evidently a complex and intertwined set of urban phenomena that weave a web of experiences and fields through which the human experience is cultivated.

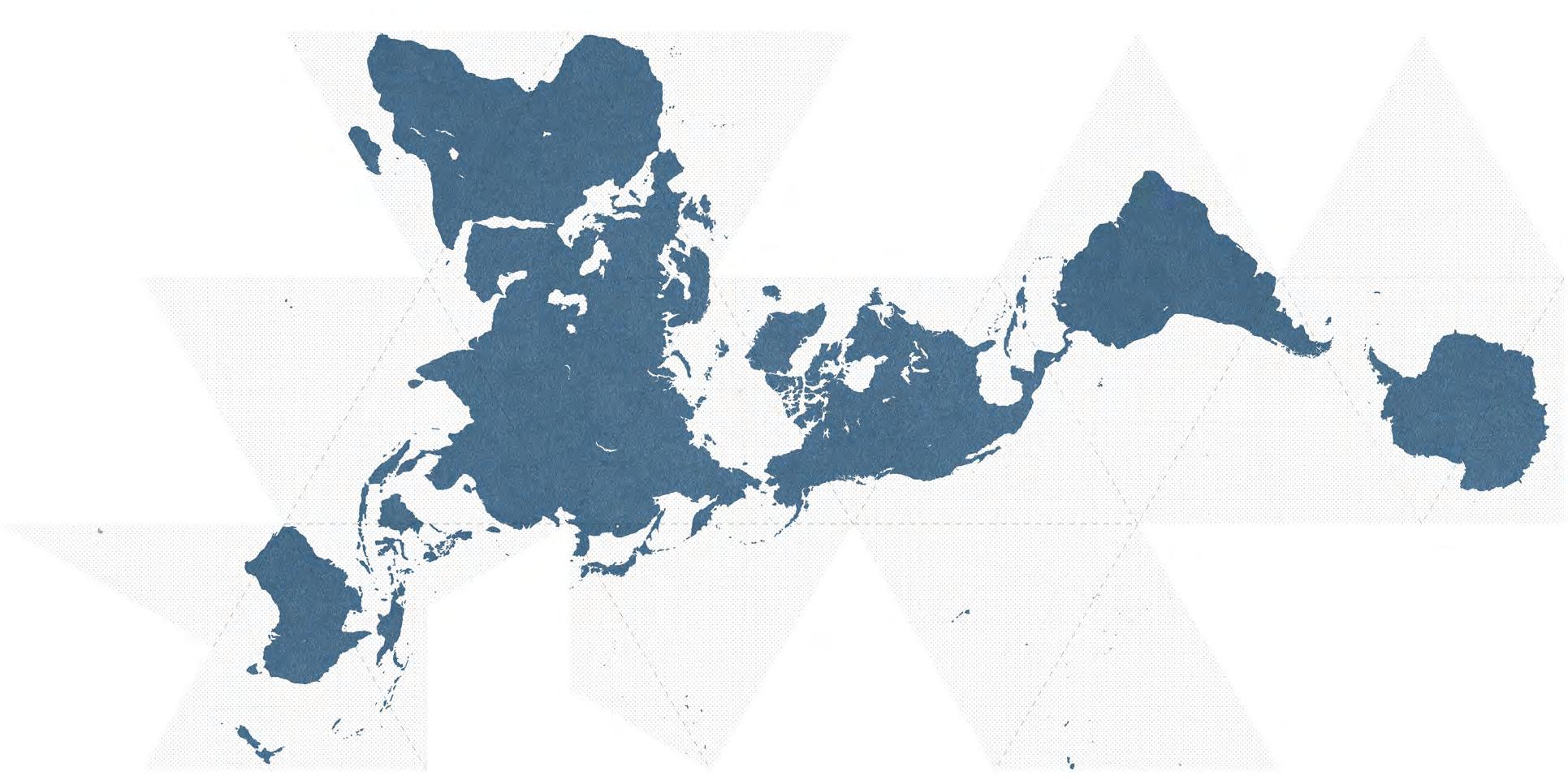

This booklet of abstracts highlights the outcomes of studying what such experiences, and aims to shed light on what constitutes urbanism(s), essentially presenting an inventory of conditions, influences, forms shaping cities across the globe. The abstracts represent a research body of work produced for the Theories & Methods of Urban Design class held at Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan.

Cairo, Egypt

30.0444° N 31.2357° E

Chengdu, China

30.5723° N, 104.0665° E

Chongqing, China

29.5657° N, 106.5512° E

Changsha, China

28.2278° N, 112.9389° E

Gui'an New District, Guizhou, China

26.4688° N 106.4831° E

Guangzhou, China

23.1291° N, 113.2644° E

Jordan, Hong Kong

22.3049° N, 114.1692° E

Singapore

1.3521° N, 103.8198° E

Shenzhen, China

22.5429° N 114.0596° E

Shanghai, China

31.2304° N, 121.4737° E

Tianjin, China

39.0851° N, 117.1994° E

Beijing, China

39.9042° N, 116.4074° E

Susono, Japan

35.1740° N, 138.9066° E

Kartal, Istanbul, Turkey

40.9184° N, 29.2205° E

Campo de Dalías, Almeria, Spain

36.8340° N, 2.4637° W

Copenhagen, Denmark

55.6761° N, 12.5683° E

New York City, New York, USA

40.7128° N, 74.0060° W

Buffalo, New York, USA

42.8864° N, 78.8784° W

San Salvador de Jujuy, Argentina

24.1858° S, 65.2995° W

Mexico City, Mexico

19.4326° N, 99.1332° W

Ecatepec, Mexico

19.6058° N, 99.0365° W

Trenton, Michigan, USA

42.1395° N, 83.1783° W

Detroit, Michigan, USA

42.3314° N, 83.0458° W

Hamtramck, Michigan, USA

42.3928° N, 83.0496° W

Inkster, Michigan, USA

42.2942° N, 83.3099° W

KHALID ABURAJAB ALTAMIMI

KHALID ABURAJAB ALTAMIMI

The expression of cultural identity is one of the key contributions of the urban designer in the transformation of the built environment. Francis Violich illustrates that “in homogeneous cultures, patterns of values and behavior provide established ways of living, well-related to environmental form”.1 As such,The urban environment can and is being used as a tool to reflect, impose or construct an identity

Yet, in the case of the Arab city, the question of identity is further complicated by the complex layered histories that have shaped the built environment over centuries. Navigating the context of Cairo specifically, those layers include a postcolonial legacy still under redefinition. Like in many other Arab cities, the question of Arab Egyptian identity is central to the new physical shifts the city is experiencing. A vision of progress coupled with a desire to attract global investment2 requires a careful reformulation of socio-spatial structures, value systems, and cultural norms.

Through legislation, initiatives, visions and media, the map of Cairo has been evolving and in constant flux between its people and the government, making it a city of dualities and competing identities, especially with the power dynamics reshaping the built form that imply the making of new identities. By tracing the intersecting layers of identity overtime, power relationships are uncovered. The colonial era imported foreign forms of planning and architecture that embraced Western thought superiority-still held to this day.3 The recent refashioning of public spaces, especially liberation square, the center of the 2011 revolution4 is also building new meanings and publics. These can be coupled with the demolition of informal settlements5, a subcultural form that makes up over half of Cairo’s urban environment6, to make way for modern large-scale developments are the tools in the identity [re]construction process resulting from the shifting power dynamics.

Understanding the influence designers exert while shaping future visions of the urban environment is imperative to the profession. Acknowledging this power, and our ability to produce and reproduce urban imaginaries and shape public perception gives us agency in the struggle to retain multicultural, locally grounded interventions. In reshaping Arab and national identities, the production of regionally grounded urban forms becomes central in cultivating meaning and confronting the banality and indifferenciation fueled by global capital.

Postcolonial, Informal, Power, Arab Urbanism, Identity.

Social Urbanism, Everday Urbanism, Informal Urbanism, Postcolonial Urbanism, Postcity Urbanism, Instant Urbanism.

1. Francis Violich, “The Search for Cultural Identity through Urban Design: The Case of Berkeley,” Berkeley Planning Journal 2, no. 1 (July 31, 2012), https://doi.org/10.5070/bp32113202.

2. Marc Angelil et al., Housing Cairo - the Informal Response (Berlin: Ruby Press, 2016).

3. Edward W Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1978).

4. Hamza Hendawi, “Cairo’s Historic Tahrir Square Is Being Transformed” The National, May 15, 2020, https://www.thenationalnews.com/ world/mena/cairo-s-historic-tahrir-square-isbeing-transformed-1.1019375.

5. Egypt Today staff. “136 Families Are Being Moved to Egypt’s Asmarat Alternative Housing Neighborhood.” EgyptToday, January 12, 2021. https://www.egypttoday.com/ Article/1/96344/136-families-are-being-movedto-Egypt-s-Asmarat-alternative.

6. Marc Angelil et al., Housing Cairo - the Informal Response (Berlin: Ruby Press, 2016).

With the prevalence of social media, the majority of people prefer to dine at a remote but instagrammable enough restaurant rather than a nearby but not instagrammable enough one. In instagrammable spots, users focus more on the shareability of the experience in the online space shaped by social media, rather than the experience of the space itself.1 On one hand, instagrammable spots often attract excess consumers or visitors. Due to the limit of internal space, excess visitors are forced to occupy public spaces for waiting, most often street spaces. They not only limit the right of local residents to use public spaces but also affect their daily experience. This has led to a debate about the occupation of public space by private commercial space. On the other hand, instagrammable spots shape consumption behaviors that actually stifle the creative use of public space by the masses.2 They are usually purposeful and singleminded, known as the “ Visit-Share-Leave” mode.3 They do not pay attention to the urban environment around instagrammable spots and ignore the various daily activities that are constantly taking place there. This has to a certain extent exacerbated the problem of uneven use of spatial resources.4

Based on this urban phenomenon, this paper will take Modern China Tea (hereinafter referred to as MCT), one of the most typical instagrammable spots in China, as the research object, and take Wuyi Square in Changsha City as the research area, and conduct an in-depth analysis in three parts. First, this paper will explain the phenomenon through the theoretical knowledge of Lefebvre’s critique of everyday life, Debord’s The Society of the spectacle, everyday urbanism, and digital urbanism. Secondly, this essay will analyze the spatial patterns of MCT and instagrammable consumer behavior patterns, simulating the impact of tourists on the public space in MCT at different times. Thirdly, this essay will combine two case studies, Superwenheyou in Changsha and Unhashtag Movement in Vienna, to propose some optimization strategies for this phenomenon through an urban design lens.

In the age of social media, the appearance of instagrammable spaces often signals the success of an urban design project.5 However, it is essential for urban designers to be aware of the advantages and limitations of instagrammable spaces. Through a specific instagrammable phenomenon, this paper attempts to reveal the possibilities of such advantages and limitations from theory to practice, providing a strong reference for current and future urban design practice.

Instagrammable Spots, Mordern China Tea, Social Media, Public Space.

Digital Urbanism, Everyday Urbanism.

1. Irma Arts, ANke Fischer, The Instagrammable outdoors – Investigating the sharing of nature experiences through visual social media, 2021,https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/ doi/full/10.1002/pan3.10239

2. Yibin Zhang, Criticism of daily life and revolution of daily life -- similarities and differences between Lefebvre and Debo’s critical theory of daily life, 2020 https://ptext.nju.edu.cn/ a0/51/c13367a499793/page.htm

3. Kai Zhou, Haitao Zhang, Yining Xia, Chong Li, Urban Consumer Space Under the Influence of Social Media: take Xiaohongshu in Changsha as an example, Modern Urban Studies (2021): 20-27

4. Seunghun Shin, Zheng Xiang, Social MediaInduced Tourism: A Conceptual Framework, e-Review of Tourism Resear, Vol. 17 No.4, 2019

5. Fabiola Fiocco, Giulia Pistone, Good Content vs Good Architecture: Where Does ‘Instagrammability’ Take Us? 2020 https://www. archdaily.com/941351/good-content-vs-goodarchitecture-where-does-instagrammability-takeus?ad_medium=widget&ad_name=relatedarticle&ad_content=954080

ALWAYS IN LINES: HOW THE INSTAGRAMMABLE “ MORDEN CHINA TEA” PLUNDER PUBLIC SPACE IN WUYI SQUARE, CHANGSHA

ZHILIN CAI

Beginning in 2010, Beijing began a decade-long state-led campaign to “Shu Jie” or decongest so-called “low-end” population from informal settlements.1 The policy aimed to eliminate potential security and fire hazards and preserve the capital’s international image by shifting this population and industry to distant suburbs, neighboring cities, or relatively underdeveloped areas. The evacuation of informal settlements in the Sanhuan Xincheng (Third Ring New Town) was completed in 2012 as a demonstration project involving the establishment of a new high-speed railway station in the vicinity. More than 2,000 residents were evacuated during the project implementation.2

This paper introduces Beijing as a global capital and point out its specificity as a postsocialist center. In terms of research methodology, this paper will adopt a topological perspective and use “folding”3 as a key analytical concept to study the changes in urban density, intensity, and height in the ring of new cities, The goal is to reveal the topological relations of state power in urban space and environment through maps of population and urban form changes, and settlement profiles, and the impact and disruption of this urban spatial change on the everyday lives of informal dwellers in local communities.

Taking the settlement removal in the Third Ring New Town as the object of study, this paper illustrates the top-down political power reshaping Chinese cities through urban renewal4 and the bottom-up networks tracking the identities and everyday lives of informal dwellers displaced in the process. The research rethink the common urban meritocracy and even anti-urbanism in China’s urban governance from the perspective of everyday urbanism.5 Through examples and critical reflections on the case of the Sweet Potato Community, we will conceive alternative ways to achieve urban spatial justice.

In the concluding section, this paper explores the agency of urban designer to delay or block this exclusionary process, through two alternative approaches: one is influencing the value judgment of the public and policy makers from the bottom up through urbanism as a tool of ideological production; the other is through opportunistic appropriation of the infrastructure improvements of as an opportunity to deliver social resources and economic benefits towards the vulnerable groups.

Floating Population, Informal Settlement, Topological Twist, Space Justice.

URBANISMS

Critical Urbanism, Everyday Urbanism, Anti-Urbanism.

1. Beijing Municipal Commission of Planning and Natural Resources. The Beijing City Master Plan 2004-2020. Beijing Planning Review, February 2005. http://ghzrzyw.beijing.gov. cn/zhengwuxinxi/zxzt/bjcsztgh2004/202201/ t20220110_2587452.html

2. Tingting Li, “Underground space cleared of 120,000 occupants in 3 years.“ The Beijing News, February 08, 2015. http://epaper.bjnews. com.cn/html/2015-02/08/content_561650. htm?div=-1.

3. Allen, John. “Topological Twists.” Dialogues in Human Geography 1, no. 3 (2011): 283–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820611421546.

4. Rowland, Nicholas J. “Infrastructural Lives: Urban Infrastructure in Context.” Science & Technology Studies 28, no. 3 (2015): 125–27. https://doi.org/10.23987/sts.55346.

5. Luca Lazzarini. “The Everyday (in) Urbanism: What’s New on the Spot.” Sociology Study 6, no. 4 (2016). https://doi.org/10.17265/21595526/2016.04.005.

JIAWEI DING

Behind the food we consume every day is a system based on global engaged production and consumption. Due to the uneven distribution of resources around the world, differences in climate conditions, and labor costs, the progressive industrialization of agriculture has crops cultivated and transported around the world. While the resulting global food system ensures an adequate supply of food in most parts of the world and maintains a degree of food diversity.

However, a closer look reveals its unsustainable nature. Maintaining a global food supply chain relies on distribution, storage, and refrigeration facilities, which cause large greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, the current pandemic has proven the limitations of a system that is not resilient and flexible enough in the face of global crises. Since some countries depend on food imports from other countries, global geopolitical crises can directly affect one or more links in the supply system. For instance, the Russian armed invasion of Ukraine has brought turmoil to the global supply of wheat and sunflower oil. On the other hand, climate change is disrupting farming practices around the world and global population growth poses new challenges to feeding populations in less fertile geographies1.

This research explores the organizational logic of an internalized system based on localized food production. It is an extension of the existing system to eliminate the uncertainty of externalities and make it more flexible and resilient. This research takes the agricultural phenomenon of Campo de Dalías Area in Almeria as an object of study, the unique spatial relationships between intensively farmed land and urban areas here2, and the model of industrial-agricultural integration can guide the construction of localized agricultural production systems3. It will be presented from the following aspect: the intensive agricultural system, agricultural network, and agro-industrial model. In the end, the research will discuss the possibility of a broader application of such an intensive agricultural urbanity in terms of productive urbanism and hinterland urbanism.

Food Production, Food Crisis, Intensive Agriculture, Agro-industry.

Productive Urbanism

Hinterland Urbanism

1. Melanie Sommerville, Jamey Essex & Philippe Le Billon (2014) The‘Global Food Crisis’ and the Geopolitics of Food Security, Geopolitics, 19:2, 239-265, DOI:10.1080/14650045.2013.811641

2. Wolosin, Robert Tyrell, “El Milagro De Almería, Espana: A Political Ecology of Landscape Change and Greenhouse Agriculture” (2008). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 366.

3. Egea, Francisco & Torrente, Roberto & Aguilar, Alfredo. (2017). An efficient agroindustrial complex in Almería (Spain): Towards an integrated and sustainable bioeconomy model. New Biotechnology. 40. 10.1016/j. nbt.2017.06.009.

Water, a vital [re]source for human life, has been impacted by the rapid urbanization of metropolitan regions worldwide. Urban infrastructures and governing institutions have proven vastly inadequate to support the coexistance of healthy water systems with ever growing human populations, thus raising the question of the sustenance of life under these circumstances.1

Cities in the developing world are sites of acute asymmetries in the access to clean water, and proper infrastructure of sanitation. The Mexico City Metropolitan Area (MCMA) exemplifies these problems. The historical source of water, the aquifer, has come under tremendous stress in recent times, leading to large-scale land subsidence.2 The city brings in drinking water from very distant basins through a 120 km-long infrastructural network requiring constant investment and expansive repairs.3 These difficulties, combined with inadequate hazardous waste management, leave the aquifer and the water distribution system vulnerable to contamination with consequent risks to public health.

The project investigates the mechanisms in which urban design can contribute to increased access to water quality, less dependance on outdated critical infrastructure and groundwater overexploitation, and increased social cohesion through sociohydrological resilience.4 The project delves into an approach to landscape and ecological urbanism to discuss alternate, sustainable, and decentralized water management systems based on hydro-urban acupuncture to address the issue of water management locally.

Using the five-fold strategy of ‘Delay, Retain, Store, Reuse and only Drain when necessary’ first proposed by De Urbanisten (Netherlands)5, the investigation looks at how social infrastructure can help develop localized water management strategies. Studying proposed and under-construction case studies in East Mexico City, the investigation discusses how Texcoco Lake Ecological Park, La Quebradora Hydraulic Park, and Lacustrine Pavilion act as urban catalysts addressing water infrastructure justice. Can other cities worldwide facing water management challenges learn from these context and scale-specific design strategies?

Aquifers, Water Infrastructure, Decentralization, Hydro-urban Acupuncture, Socio-hydrological Resilience

Landscape Urbanism, Ecological Urbanism.

1. Tiboris, Michael, “Threats to Supply Chain in the Developing World,” The Chicago Council on Global Affairs. April 01, 2016

2. National Research Council, “Mexico City’s Water Supply – Improving the Outlook for Sustainability” The National Academies Press, 1995.

3. Mccord, Hayley, “A Sinking Thirsty City: Water Crisis in Mexico City,” Latin America Reports, September 11, 2021. https://latinamericareports. com/a-sinking-thirsty-city-the-water-crisis-inmexico-city/6075/

4. ARUP, “City Characterisation Report Mexico City,” The Resilience Shift, April 2019. https://www.resilienceshift.org/wp-content/ uploads/2019/04/CWRA_CCR_MexicoCity.pdf

5. De Urbanisten, “Towards a Water Sensitive Mexico City - Public Space as a Rain Management Strategy,” De Urbanisten & Deltares. July 2016

URBAN CATALYST: PUBLIC SPACES AS PARALLEL WATER MANAGEMENT INFRASTRUCTURES

After the 1980s, China’s rapid urbanization process led to the outward urban expansion and the encirclement of former suburban villages, giving rise to the development of a new spatial category – the urban village.1 Due to China’s dualistic urban-rural and Hukou policy2 urban villages are not integrated into cities’ overall planning and management.3 These villages are often crowded, lack proper infrastructure and are portrayed as chaotic. At the same time, their affordable rents provide a transition area for newcomers to integrate into the city, and their thrivinginformal economy also provides jobs and opportunities for social integration. Appropriate interventions and transformation practices rely on adequate analysis and understanding of urban villages’ spatial patterns and social structures.4 Lacking proper studies, interventions can disrupt the balance of the social structure and cause displacement of urban villagers.5

This investigation consists of three aspects. Firstly, it elaborates on the changes and development policies in Chinese urban villages from a historical perspective, summarizing the timeline and typical renewal patterns from the early renovations to today’s systematic and comprehensive urban renewal process.

The second part takes Luntou Village in Guangzhou and Shuiwei Village in Shenzhen as examples of informaland social urbanisms, analyzing the architectural and spatial environment, community culture, economic structure, ecological environment, social organization structure, community management, and upgrading and transformation policies through the approach of empirical urbanism. Shenzhen’s upgrading policy in Shuiwei Village is a successful attempt to transform an urban village into a talent apartment. Guangzhou optimized its policy based on Shuiwei’s case by transforming Luntou Village into long-term rental apartments with makers as the primary target group.

The third part provides a comparative summary, analyzing the status before and after the renovation and exploring the differences arising from different models and policies. The focus of the study is to explore how to engage multiple agencies, such as urban designers, the public, and the government, more effectively in order to generate more appropriate upgrading methods.

Urban Village, Empirical Urbanism, Upgrading methods, Social Urbanism, Urban regeneration URBANISMS

Informal Urbanism, Social Urbanism, Empirical Urbanism.

1. Wu, Fulong, Fangzhu Zhang, and Chris Webster. “Informality and the development and demolition of urban villages in the Chinese periurban area.” Urban studies 50, no. 10 (2013): 1919-1934.

2. China classifies household registration attributes into agricultural and non-agricultural hukou based on geography and family member relationships. Agricultural hukou can obtain land use rights in the rural areas where they are located, but cannot enjoy several policies in the cities

3. Xuejiao Li.Reflections on urban village transformation and planning. Building Materials Development Orientation, (2022) 102–104.

4. López, Oscar Sosa, Raúl Santiago Bartolomei, and Deepak Lamba-Nieves. “Urban Informality: International Trends and Policies to Address Land Tenure and Informal Settlements.” (2019)

5. Kamalipour, Hesam. “Improvising places: The fluidity of space in informal settlements.” Sustainability 12, no. 6 (2020): 2293, 22-27

Taikoo Li, Chengdu’s most recent landmark, symbolizes the unique identity of this city: a fashionable, diverse, complex and high-end commercial hub. As human creativity and consumption has become a more crucial resource for a city in modern society1 The success of Taikoo Li continues to attract more and more young talents to work and settle in Chengdu.

With the popularity of social media like Tiktok and Instagram, urban space holds a double nature, one in the physical world and the other in the digital one. Taikoo Li is one of the most popular Instagrammable places in China with its unique neotraditional architectural forms and diverse ephemeral cultural activities. Most of the programs are organized by the developer, together with the exclusive commercial tenants, mainly focusing on art exhibitions and fashion shopping. This robust programming and the sophisticated use of media targeting a particular user type, enrich the culture of the TaiKoo Li neighborhood and create a more diverse and creative atmosphere for consumers2

Taikoo Li used to be the largest low-lying shantytown in Chengdu. However, the construction of Taikoo Li demolished most of the previous buildings, diminishing the memories of this neighborhood and destroying the local identity to some extent. When the memory of past experiences and the relation to its surroundings is deminished, the identity of the place is also lost3. This approach to redevelopment erases existing networks and retains the power from the professional experts instead of partnering with ordinary people to retain the meaning of everyday life4

This essay will use the lens of Everyday Urbanism to challenge the commercial success of Taikoo Li and critique the consumerism-orientated urban renewal model. By using the empirical methods to record and analyze the everyday activities in Chengdu, trying to find the lost experiences and identities of this place. Based on the empirical analysis of everyday life, it offers possible redesign ideas for Taikoo Li, through which the importance of everyday life can be emphasized. Overall, the reflection and redesign of Taikoo Li aim to provide an illuminating sample for the many consumerist-oriented urban renewal projects in China, which aims to discover the immense human wealth that the humblest facts of everyday life contain5.

Digital, Tiktok, Urban Renewal, Consumerism, Everday Life.

Ephemeral Urbanism, Everyday Urbanism, Empirical Urbanism, Digital Urbanism.

1. Charles Landry, The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators (London: Earthscan, 2009).

2. Bin Liu and Zhongnuan Chen, “Power, Capital and Space-Production of Urban Consumption Space Based on the Transformation of Historical Street Area: A Case Study of Sino-Ocean Taikoo Li in Chengdu,” Urban Planning International 33, no. 1 (2018): pp. 75-80, https://doi. org/10.22217/upi.2016.265.

3. Kenneth Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge, MA: MIT Pr., 1979).

4. John Chase, Margaret Crawford, and John Kaliski, Everyday Urbanism (New York: Monacelli, 2009).

5. Henri Lefebvre et al., Critique of Everyday Life (London: Verso, 2014).

In the context of the era of big data-driven design, what is the role of an urban designer in an urban renewal project? An architect, an implementer of flashy projects, or a social engineer? What means should governments and planners take to promote a paradigm shift in urban regeneration? Ultimately, it is not a question of whether a programmer or an urbanist is best suited to design cities1, but rather who can provide citizens with the right to the city through design and reshape the concept of urbanism while striving to establish some ethics in terms of data.

This paper will introduce the urban indicators of Beijing and Shenzhen, the history of their development, the need for urban renewal in Beijing and how these renewal projects affect local residents, examine the timeline of theoretical development of urban renewal in China, and at the same time, introduce case presentations, the microrenewal of the Shuangjing community in Beijing2, the social incubator in Shuewei Village in Shenzhen3, and the redevelopment of the cultural and creative town of Xidian Village in Beijing4, discusses the paradigm shift of urban renewal and the use of smart urban approaches in urban renewal, and examines how the government and urban designers use smart platforms to coordinate residents’ opinions and help them develop planning and renovation plans under different perspectives of renewal strategies, how to create affordable housing and shared spaces for young people in urban villages by means of design, and how to activate urban brownfields through landscape and ecological restoration to activate urban brownfields, attract popularity, and rebuild the relationship between people and nature.

Through theoretical studies and case studies, we can draw the results of the discussion. In a data-driven era, we still need urban planners and urban designers. The technological tools of smart cities are only one of the ways we can achieve a paradigm shift in urban renewal; digital tools are only the bricks of our time, and we still need people who can lay them. Notably, we need to ensure that these tools are open to citizens and not become a way for governments or powerful stakeholders to exert control and increase profits, and that urbanites can enrich their toolbox by adding evidence-based, socially engaged design approaches that better serve city residents. Urban designers should consider and analyze urban data and use information tools and platforms in the design process and be aware that big data has spatial implications, balance existing power relations, and be able to shape spaces and activities.

Big data, Urban Renewal, Informal, Smart Cities, Public Engagement.

Smart Urbanism, Informal Urbanism, Landscape Urbanism.

1. Data-driven urbanism: Do we still need planners? (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/VaggyGeorgali-2/publication/316460418

2. UrbanXYZ. “Urban Governance Laboratory of Shuangjing Street Based on New Urban Science.” UrbanXYZ, 2019. http://urbanxyz.com/ sj/1-zhuye/xc46d4a7b.html.

3. Social incubation in the urban village -. World. (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https:// www.world-architects.com/en/architecturenews/reviews/social-incubation-in-the-urbanvillage

4. Beijing Xidian Fanshi iTOWN / Change Studio. Gooood Design Network. (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.gooood.cn/beijingxidian-funs-itown-by-change-studio.htm

Along the Detroit River, risks associated with climate change within the different cities vary greatly. Poor communities of color are more exposed and vulnerable to the risks and have less adaptive capacities.(1)

It is hence, essential to question to what extent have our design professions learned from the negative impacts of urban renewal policy decisions to “clean blight” and displace poor people of color in the past? Could climate adaptation be creating new waves of displacement and exclusion? How will our contributions as designers prioritize the needs of the underserved communities this time? What partnerships and coalitions can help co-produce more just urban futures? (2)

Rendering visible the socio-environmental vulnerabilities that communities of color face along the Detroit River, this paper studies the consequences of legal decision-making concerning environmental justice in Michigan.(3) Referring to the consequences of climate-related displacement in Boynton, White Pine, and Flint, it delves into the patterns of migration and injustice to suggest just solutions.(4) It carefully analyzes pollution through mapping, data analysis, and critical thinking. The research challenges the traditional model of large-scale master planning as adequate for tackling urban climate adaptation in the region. Instead, the research aims to learn from the racist policy making that supports these injustices and suggest implementable strategies. By addressing social and crisis urbanism at different scales of vulnerability, the industrially polluted Detroit is studied to promote techniques that must be implemented to address the coexistence with the environment.

The paper is a generative, system-based proposal designed specifically to operate within the patterns, structures, and dynamics of the urban crises facing the communities of color along the Detroit River. It imagines reorganizing these systems toward more socially productive ends, mobilizing legal decision-making to rescript the social and institutional processes through which the urban might be designed.(5)

Climate Justice, Equitable, Vulnerability, Adaptation, Just Resilience.

URBANISMS

Social Urbanism, Crisis Urbanism.

1. Niloofar Mohtat, Luna Khirfan, The climate justice pillars vis-à-vis urban form adaptation to climate change: A review, Urban Climate, Volume 39, 2021

2. Benz, Terressa A. “Toxic Cities: Neoliberalism and Environmental Racism.” Critical Sociology 45, no. 1 (2017): 49–62. https://doi. org/10.1177/0896920517708339.

3. Taylor, DE (2014) Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility. New York, NY: New York University Press.

4. “Environmental Justice Case Study: Solution Mining in White Pine, Mi and the Bad River Reservation.” University of Michigan. Accessed April 27, 2022. http://websites.umich. edu/~snre492/pmaj.html.

5. Tuning Up the City: Cedric Price’s Detroit Think Grid, Kathy Velikov, 2015

Who is a refugee? On account of events falling under the lens of political conflict, refugees are individuals compelled to flee their country and find asylum in new territories. War, climate change and religious conflict are some of the leading causes driving the current global refugee crisis. To become a refugee, these individuals have to prove they are subject to unconceivable hardship in their countries of origin including exposure to violence in many instances. In the process, they undergo unique experiences - confronting sudden shifts in their lifestyles. While the process to become a refugee varies from country to country, the resettlement process generally follows a similar pattern. Refugees are first situated in temporary camps, from where they are transported to new housing locations after their refugee status is approved in the host country. In reality, however, many refugees end up spending their entire lives in these ‘temporary’ camps and have limited access to resources like education, access to jobs, and adequate housing and infrastructure.

In A Refugee Camp Is a City, Ana Asensio states that “a refugee camp is an ephemeral city whose inhabitants have been placed there like pieces in a puzzle, a stand-by city that architecture has not embraced.” As designers, we are confronted with two questions: (1) How can the refugees’ housing needs be attained within a framework that accepts their past lifestyles and experiences and helps them adapt to their new environment?; and

(2) What opportunities emerge from these new settlements that mutually benefit the refugees and their host cities?

The U.S. is seeing a sudden influx of refugees from Afghanistan and Ukraine at a time of divided politics and constrained resources and insufficient infrastructure to support this large scale immigration. Following a structured analysis of case studies - from the Kakuma Camp in Kenya at a global scale, to resettlement typologies in Hamtramck and Buffalo in the U.S., this research discusses the different approach to refugee camps and integrated communities, and determine which aspects can be potentially incorporated into inexorable future models to improve the refugee resettlement process.

Adaptability, Culture Change, Integration, Accessibility, Unification.

Crisis/Emergency/Conflict Urbanism, Social Urbanism.

1. “What Is a Refugee? Definition and Meaning: USA for UNHCR.” USA for UNHCR. https://www. unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/what-is-a-refugee/.

2. U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Refugees,” USCIS, 2022, https://www.uscis.gov/ humanitarian/refugees-and-asylum/refugees

3. Ana Asensio, “A Refugee Camp Is a City,” aaaa magazine, 2014, https://theaaaamagazine. wordpress.com/2014/02/18/a-refugee-campis-a-city/.

4. Elizabeth Cullen Dunn, “The Failure of Refugee Camps”, Boston Review, 2015, https:// bostonreview.net/articles/elizabeth-dunn-failurerefugee-camps/

5. Detroit Public TV, PBS, “Northern U.S. border experiences alarming influx of refugee crossings”, 2022, https://www.pbs. org/newshour/show/northern-u-s-borderexperiences-alarming-influx-of-refugeecrossings

6. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Urban Refugees,” UNHCR, 2018, https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/refugees.html

THE ADAPTATION COMPLEX: SHIFTS IN LOCATION, CULTURE AND IDENTITY

Accessibility plays a vital role in our daily lives, becoming a defining factor of urban life impacting cultural, economic, social, and political aspects. The multimodal hub has become more than a transportation node to introduce new community centers, event, commercial, and retail space, establishing itself as an imperative part of the urban fabric.1 Metro regions recognize the importance of such hubs in a fast-changing landscape, making it necessary for the implementation of flexible and anticipatory transit infrastructure within the urban region. Such infrastructure is necessary in providing a sustained, uninterrupted accessibility by integrating multiple modalities into regional public transit systems of highly congested urban areas.2

While the technological advances driving more efficient and reliable future transit systems are here, cities are challenged to adjust fast enough. The outdated and inadequate infrastructures systems leave cities questioning how to transform or update their current transit systems or alternatively how to plan for an entirely new transit framework. Multimodal hubs can act as nodes within the greater urban and mobility ecosystem by facilitating regeneration, economic viability, and social mobility, ultimately becoming drivers for inclusive and sustainable urban growth.3 In the case of Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Station, and Mexico City’s Ciudad Azteca Multimodal Transfer Station, both transit hubs not only work toward seamless accessibility but also ensure a strong relationship to the periphery region and the hinterland’s operational landscapes. Both cases demonstrate that urban accessibility entails the integration of many different interrelated elements in the urban type of the transportation hub.4 This investigation uses four indicators to assess their main characteristics and performance: urban connectivity, operational agents, socio-economic development, and urban quality.

The uncertain futures our society faces calls for designers to look at intermodal hubs through a visionary lens, reconceptualizing future realities, while keeping in mind the importance of infrastructure as the main driver of urban transformation and overall growth. Tracing the relationships established between the hub region’s infrastructural agents and the surrounding site’s pre- and post-infrastructure application is essential to identifying the prospects and limitations for alternative methods to intervene. The transit systems of the future are likely to be very different from what exists in most of the world today.5 How can we design for unanticipated changes through models of flexibility and resilience?6

Multimodal, Interchange(hubs), Infrastructure, Re-Conceptualize, Accessibility.

Network Urbanism, Infrastructure Urbanism, Visionary Urbanism.

1. ARUP. “Svensk Forskning För Hållbar Tillväxt| Rise.” Accessed April 6, 2022. https://www.ri.se/ sites/default/files/2020-12/RISE-Arup_Mobility_ hubs_report_FINAL.pdf

2. Pitsiava-Latinopoulou, Magda, and Panagiotis Iordanopoulos. “Intermodal Passengers Terminals: Design Standards for Better Level of Service.”

3. “Future of Stations.” Arup Foresight, December 3, 2020. https://foresight.arup.com/ publications/future-of-stations/.

4. “Improving Quality of Life through Transit Hubs.” Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www. arcadis.com/-/media/project/arcadiscom/com/ perspectives/global/2018

5. “The Future of Mobility ,” October 2016. https://data.bloomberglp.com/bnef/ sites/14/2016/10/BNEF_McKinsey_The-Futureof-Mobility_11-10-16.pdf.

6. O’Sullivan, Feargus. “Planning the Transit Hubs of the Future.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, July 10, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/ news/articles/2017-07-10/how-to-future-proofa-transit-hub.

Conflicts on antagonistic political claims over the geographical space cause unrest leading to war and crisis, leaving long-term tangible and intangible scars. As citizens in those regions try to escape seeking safety from persecution and political upheaval, a second crisis unfolds, the emergence of the refugee. Growing through a lengthy process to achieve this status, refugees embark on a journey that may leave them in refugee camps for many years1 while they wait to be transferred to the final destination through the refugee resettlement program2.

While many US cities view refugees as an opportunity rather than a burden3, it is the refugees who face many challenges in integrating into the host society. In the US, the challenges depend on their migration experience, their resources to function in unfamiliar environments, and the receptiveness of the receiving cities4. With these challenges in mind, host cities are expected to create an environment that adapts and responds to the needs of incoming refugees, allowing them to integrate into a new urban environment. How can designers help create more adaptive and resilient urban environments for refugee populations while also serving the needs of the current residents?’

Many US cities recognize refugees’ potential to reactivate their economies and social fabric in urban areas struggling with population loss. Southeast Michigan, for instance, is home to about half of all the refugees resettled in Michigan over the past ten years 5 and the local economic impacts of the refugees on their communities are widely felt6. Further raising the productivity of the city, they access the job market, stimulate returns and investment, boost innovation, and grow the local enterprise7. Yet, refugees face many challenges and require a solid social network of support. . The research studies the city of Inkster in Michigan as new grounds for accepting refugees through the lens of social urbanism - mapping the social structure, ecology, and infrastructure that exists. Counteracting the trauma induced by war and ensuring a dignified, equitable life for refugees of all backgrounds seeking asylum in new territories should be a priority for urban designers. With the world facing an unprecedented refugee crisis, helping cities become safe heavens is imperative for their resiliency. Therefore, through the social urbanism lens, this research questions agency of refugees and the role of social infrastructure in aiding the regeneration and anchoring of the communities? This research shows how urban designers can contribute to the co-creation of socio-spatial frameworks that provide resilience through social infrastructure.

Social Infrastructure, Social Ecology, Egalitarian Communities, Agency URBANISMS

Social Urbanism, Crisis Urbanism.

1. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Resettlement,” UNHCR, 2018,

2. “The U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program – an Overview,” www.acf.hhs.gov, n.d.

3. Philippe Legrain, “Refugees Are Not a Burden but an Opportunity - OECD,” www.oecd.org, 2016.

4. Uma A Segal and Nazneen S Mayadas, “Assessment of Issues Facing Immigrant and Refugee Families,” 2005.

5. “Economic Impact of Refugees in Southeast Michigan Immigration Research Library,” www. immigrationresearch.org.

6. “Economic Impact of Refugees in Southeast Michigan the Background 4,” n.d.,

7. Philippe Legrain, “Refugees Are Not a Burden but an Opportunity - OECD,” www.oecd.org, 2016.

What is an urban park? In Basies Landscape Architecture, park, in urban terms, is an often green and pleasantly landscaped area of land set aside for public use, in particular sports, recreation and relaxation, and also valuable for its ecological functions.”1 The main feature being its public nature, urban parks represent equity. As spaces that everyone can enter and use without additional conditions. Ownership and management considerations are critical in the sustainability of urban parks. When public, the government manages and operates them, but many privately owned park are also publicly accessible. Urban parks are critical infrastructures providing a wide range of social, ecological and cultural services for all citizens. More and more private capital pumped for enter the construction and operation of the parks.2 The relationship between the park and the city is starting develop a new dynamics that may challenge their public nature, and as such, the notion of the park as an open and egalitarian urban space. So how can we reveal this dynamic relationship between the production of public assets and the aggressive logics of private capital fueling urban development? What kind of future may this render and how can the urban designer take part on it?

This research focuses on the production of urban parks in New York City and uses the lens of landscape and empirical urbanisms in its development. The research develops a taxonomy of urban parks and maps and analyzes their key features. 3 4 Six types of urban parks include: the extra-large carpet, the waterfront theme, the infrastructure ground, the community commons, the pocket node, and the plaza. The analysis of elements includes: edge, size, program, ownership, access, management and operation. Thorough an in-depth analysis of Brooklyn Bridge Park and Bryant Park address the key factors of its formation, the main spatial types, and the relationship between private capital and public interests. As popular public spaces, urban parks are not only a place for outdoor activities, and entertainment, but also a habitat for a host of ecologies to thrive. Good design should integrate people and wildlife and consider the role of parks facing a changing climate in our cities. The layers of management and operation of such space resources is central to make them an important space asset for cities. Urban designers can contribute beyond space design integrating life cycles and programmatic and management regimes in their design for the parks in the city.5

Urban Parks, Infrastructure, Landscape Urbanism, Publicity, Operation

Landscape Urbansim, Empirical Urbanism.

1. Waterman, Tim, and Ed Wall. Essay. In Basics Landscape Architecture 01: Urban Design, 170. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2017

2. KAYDEN, Jerold S. Privately Owned Public Space. The New York City Experience. Toronto, John & Wiley & Sons, 2000.

3. Cranz, Galen. The Politics of Park Design: A History of Urban Parks in America. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989.

4. “OneNYC 2050: Building a strong and Fair City.” 2019. #OneNYC. https://onenyc. cityofnewyork.us/.

5. Low, Setha M., Dana Taplin, and Suzanne Scheld. Rethinking Urban Parks: Public Space and Cultural Diversity. University of Texas Press, 2006.

In recent decades, the rehabilitation of old urban areas has been more popular worldwide as many cities aim to present themselves as rich multicultural destinations. Many elements of tangible and intangible history,1 such as planning patterns, historic structures, social networks, lifestyles, and traditional crafts, are preserved in historic districts. These come together to generate a unique arrangement that expresses the city’s identity and collective memory.2 There is an emerging consensus that historic districts can greatly benefit cities.3 However, with the rapid expansion of cities and the ensuing urban transformation, these areas tend to experience severe deterioration. The slow pace of development causes the loss of high- income local residents, which leads to a decline in economic vitality and a general deterioration of their living environment. Located in central city areas and facing mounting real estate pressures, these areas have been the focus of many interventions and formal planning processes in most countries of the world.4 Initially, some initiatives were primarily targeted towards conserving historical landmarks.5 However, urban conservation should not be restricted to preserving physical structures; it should also contribute to the long-term viability of social patterns. Thus, it is important to incorporate everyday urbanism strategies into the planning and design process, to consider how to keep cultural traditions alive and assist citizens in thriving under changing circumstances.

This research deals with examples of urban interventions in the historic districts in China, including the Nantou Old Town in Shenzhen and Tianzifang in Shanghai. I will scrutinize these projects from the lens of everyday urbanism to illustrate how spaces and social networks are intertwined in the production of urban life. When considering upgrading and other interventionist methods, how can the majority of residents effectively participate in the redevelopment process? How can these groups of residents be empowered, and how can community services be supported to meet their basic needs on the one hand while integrating with and enhancing their historic environment on the other? How can residents be protected from the side effects of regeneration? Through the study of the projects, this research discusses everyday urbanism as a possibility to enhance the local communities and the prospect of placing using traditional culture and everyday life as a catalyst for regeneration in historic districts.

Historic District, Urban Renewal, Cultural Landscape, Everyday Urbanism, Community

Everyday Urbanism.

1. El-Basha, Mona Saleh. “Urban Interventions In Historic Districts As An Approach To Upgrade The Local Communities”. HBRC Journal 17 (1): 329-364. 2021

2. Ibid

3. Larry Ford, “Historic Districts and Urban Design,” Environmental Review 4, no. 2. 1980

4. Steven Tiesdell, Taner Oc, Tim Heat, “Revitalizing Historic Urban Quarters”, Architectural Press, 1996

5. Ken Bernstein, “Top Ten Myths - Home | Los Angeles City Planning,” The Top Ten Myths About Historic Preservation, https://planning.lacity.org/ odocument/e315c7f3-e066-470d-be31bb05a01b0f42/Top%20Ten%20Myths_0.pdf.

In February 2008, the Stratigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of London declared an end to the Holocene epoch and effectively announced the beginning of the next geological period, the Anthropocene.1 This brings a close to a period of environmental and climate stability and ushers in an age of unpredictable environmental instability accentuated by human development. As a response, ecological sustainability has emerged as the prevailing response to the destabilizing effects of short term-planning when addressing climate change and rising water levels in urban areas. Urban water management poses an immense challenge in many cities where outdated or insufficient infrastructure is not equipped to deal with these changes. As global temperatures get warmer, water levels will rise because of the melting ice caps and increased amounts of precipitation. Currently, stormwater infrastructure mainly contains engineered gray solutions which, although effective to some extent, are expensive to maintain, unequally distributed, and disrupt the natural ecosystems.

With the rise of sustainability as a viable solution to environmental issues, this paper investigates the ecological concept of “Sponge City” as an alternative utilizing green and blue methods opposed to gray infrastructure.3 Originating in China, this strategy seeks to address urban flooding through the use of an environmentally conscious urban model. The basis of this paper will seek to build a strong theoretical understanding of Sponge Cities by examining the agents involved, the underpinnings, and the method when designing these ecological models. This investigation traces how these strategies are funded and implemented, their ecological performance and effectiveness, and their viability as infrastructure in the contemporary urban context.

To research the ecological relationships within the Sponge City framework, this paper looks at the overall systems of the city and then, on a more micro-level, selects a specific instance within the city to further examine. The area of study will be the Gui’an New District, a relatively new city area and part of the first batch of Sponge Cities created. The study delves deeper on its unique geographical location, rainwater and flood systems, and governing/financing policies.5 Findings from this research can show how strategies can be adapted in similar cities and thus scale down gray infrastructure. This paper aims to situate urban design practice within the discourse of ecological design to create a symbiotic relationship between the human and the natural. How can we, as designers, further be critical of the impacts of infrastructure on the urban landscape?

Geology, Anthropocene, Climate, Ecology, Sponge City.

URBANISMS

Ecological Urbanism

1. National Geographic Society. (2019, June 5). Anthropocene. National Geographic Society. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https:// www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/ anthropocene/

2. Wong, T. (2021, November 11). The man turning cities into giant sponges to embrace floods. BBC News. Retrieved March 31, 2022

3. Yin, D., Chen, Y., Jia, H., Wang, Q., Chen, Z., Xu, C., Li, Q., Wang, W., Yang, Y., Fu, G., & Chen, A. S. (2020, November 5). Sponge City Practice in China: A review of construction, assessment, operational and maintenance.

4. Bélanger, Pierre. “Landscape As Infrastructure.” Landscape Journal 28, no. 1 (2009): 79–95.

5. Urban Water Cycle, Sponge City, Flooding, Water Management,Resilience

“El Cantri,” as the indigenous Organización Barrial de Túpac Amaru calls it [1], is a radical social housing project on the outskirts of San Salvador in the northern province of Jujuy, Argentina. What began as an ambitious, self-organized response to economic crises soon became a sociopolitical force of indigenous idealism and economic exception that advocated for expanded labor rights, increased social mobility, and sustainable economic status. [2] The project grew in scope during a period of “consolidation” from 2003 to 2016, after which its hyper-centralized leadership and organization were criminalized [3] and the sustaining government funding frozen. [4]

This essay explores the outside tethers of economics, politics, and social cultures governing the onset and outcomes of the Tupac Amaru development. [5] The research utilizes an interdisciplinary approach to outline the organizational crucial moments and actors that aided in maintaining their initial success. By investigating the project’s negotiation of social, queer, and visionary urbanisms, this paper expands upon the unique aspects of Tupac Amaru towards new ground in urban theory. The paper (1) reconsiders what it means to build and nurture indigenous communities today, (2) unpack the effects of queering normative development mechanisms as that multiplicitous identity, and (3) speculate upon the potential benefits of socially-driven design frameworks that foster slower, self-reliant cultures of care.

This paper argues for engaged methods of making which construct and maintain cultural and architectural relationships in parallel. It hypothesizes that similarly “othered” communities can make infrastructure adjustments—co-produced with designers, planners—so as to better prepare for the antagonistic manipulations of outside tethers. Focus will be placed on the role of designers in cultivating cultures of care that, over time, foster resilient sociocultural connections and promote diverse practices of embodied knowledge and methods of making. By working to expand notions of design agency, co-production of space, and queering of practice, the allied design disciplines might work to advocate for contemporary communities at similar risk of oppression. This paper argues that the current trajectory of “El Cantri” cannot be separated from the movement’s intersectional identities of “otherness” along queer, black, poor, and indigenous identities, [6] and that urban designers might co-produce independent urban frameworks that maintain bottom-up practices of community building while preparing for hostile tethers.

Indigenous, Idealism, Housing, Bottom-up, Identity.

Social Urbanism, Queer Urbanism, Infrastructural Urbanism.

1. Justin McGuirk, Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture (Brooklyn: Verso: 2014).

2. Melina Gaona, “Experience, city & identity around the neighborhood organization Tupac Amaru,” Doctorate, Faculty of Journalism Social Communication (January 4, 2017).

3. Melina Gaona, “Condiciones y características del surgimiento y desarrollo de la organización Tupac Amaru en Argentina,” Rev. Rupturas 8, no. 2: Costa Rica (2018).

4. Lawrence Blair, “Argentina’s Milagro Sala: Criminal, or ‘Political Prisoner?’” Americas Quarterly September 11, 2017.

5. Fernanda Valeria Torres, “Territorialization process of the Tupac Amaru Neighborhood Organization,” UNICEN: Estudios Socioterritoriales (2018).

6. Costanza Tabbush and Mariana Caminotti, “Gender Equality & Social Movements in Postneoliberal Argentina: The Organización Barrial Tupac Amaru,” Latinoamericano 23, no. 46 (2015). 147-171.

CULTURES,

KEJIE WANG

KEJIE WANG

The 1950s saw the introduction of computers to the world, and 50 years later, with the explosion of Internet technology, electronic devices were further popularized. Modern society is today inseparable from computers and other technological gadgets. The development of electronic technology, such as online shopping, Google Maps, monitoring equipment, has also greatly changed the way cities operate. With the continuous improvement of computer technology, various high-end technologies have emerged to help urban designers and scholars push the boundaries of their thinking1. This paper focuses on urbanism in the context of computer technology, and attempts to answer these questions: Why is computer science important for urban design? How can computational urbanism improve the quality of human life? How can computational urbanism help the urban design field of practice understand cities better? How does computational urbanism implement in practice? What are the limitations and drawbacks of computational urbanism?

This paper is divided into three parts. The first part introduces the background knowledge of computing and introduces the relevant connections with urban design. In the second part, I delve into parametric and videogame urbanism through case studies.

ZHA’s Kartal Masterplan2, offers a glimpse on the earlier generation of parametric urbanism designs. I will explore how it responds to the current situation of the site, what are the characteristics of the architectural form in the parametric context, and what are the shortcomings of such an approach3. Block’hood4 and Common’hood by Jose Sanchezis a city-making videogame offering new design methods that inform the discussion on how Videogame Urbanism can offer new approaches to urban design and inform theory; Subculture city by Bartlett school of UCL explores how different types of subcultural spatial elements can change when combined together. Non-Fungible life in the Metaverse by Bartlett school of UCL provides a platform for people to test the viability of the metaverse. Through these two perspective of computational urbanism, this investigation sheds light on the ways computer science can inform new urban design methods while remaining attentive to the shortcomings of embracing technology without a critical gaze5.

Computational Technology, Parametric Urbanism, Video Game Urbanism, Urban Possibility, Future

Parametric Urbanism, Videogame Urbanism.

1. Fusero, Paolo, Lorenzo Massimiano, Arturo Tedeschi, and Sara Lepidi. 2013. “Parametric Urbanism: A New Frontier for Smart Cities.” The Journal of Urbanism 2/2013, no. 2013 (II Semester): 5.

2. Hadid, Zaha. n.d. “Kartal Masterplan – Zaha Hadid Architects.” Zaha Hadid Architects. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://www.zaha-hadid. com/masterplans/kartal-pendik-masterplan/.

3. Erlendsson, Gudjon. 2020. “15 Basic parameters in urban design Thor Architects - Blog.” THOR Architects. https://www. thorarchitects.com/15-parameters-urbandesign/.

4. Sanchez, Jose. n.d. “Block’hood — Plethora Project.” Plethora Project. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://www.plethora-project.com/blockhood.

5.Zuckerberg, Mark. 2021. “Welcome to Meta | Meta.” Meta. https://about.facebook.com/meta/.

This research emphasizes the multiple values of the underutilized and neglected land present in de-industrializing regions. While often described as unproductive and polluted, their economic value is only one of the many attributes these spaces posses, with other including ecological and cultural values to local residents and often overlooked. This research discusses the boundless possibilities of these lands and their vital role in increasing biodiversity, telling history, and revealing important intangible values.

In this research, I discuss the prospects for underutilized lands in deindustrializing urban regions and engage the concepts of Terrain Vague,1 Drosscape,2 and the Third Landscape.3 These commonly neglected areas can be “seen as a biological necessity that influences the future of living things and modifies our interpretation of the territory.”4 The essays begin by discussing the importance, necessity, and benefit of these three lenses for a new land stewardship paradigm combined with the case study of each related project. The investigation uses a an approach through the lenses of ecological, planetary5, and post-industrial urbanism. I then use the case of the Detroit River shorelands and the many abandoned, vacant, industrial and polluted properties as a case to consider the potential of this approach. I look at these formerly industrial landscapes in the city of Trenton. In this process, I claim that urban designers can help reimagine these inaccessible properties as spaces of opportunity for the coexistence of multiple species, a kind of wildlife sanctuary, bringing them back to productive lands in a time of climate uncertainty.

Third Landscape, Terrain Vague, Underutilized Land, Post-city Urbanism, Planetary Urbanism.

Post-city Urbanism, Planetary Urbanism, Landscape Urbanism.

1. de Sola-Morales, Ignasi. 1955. Terrain Vague. Ebook.

2. Berger, Alan. “Drosscape : Wasting Land in Urban America.” Book. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006.

3. Rocca, Alessandro. “Planetary Gardens : The Landscape Architecture of Gilles Clément.” Book. Basel Boston: Birkhäuser, 2008.

4. Clément, Gilles, and Tiberghien, Gilles A. “The Planetary Garden and Other Writings.” Book. Penn Studies in Landscape Architecture. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

5. Brenner, Neil. “The Hinterland Urbanised?” Architectural Design. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, n.d. doi:10.1002/ad.2077.

OTHER WAYS POSSIBLE: THE POSSIBLE ROLES OF UNDERUTILIZED LAND IN THE DE-INDUSTRIALIZING CITY

Both World War II and the subsequent Cold War changed the subterranean urban landscape worldwide, especially with the emergence of numerous underground military infrastructures.1 As the main space for emergency response in wartime, underground military shelters protect the citizens’ lives and national assets. While the possibility of re-emerging armed conflict still exists, these hidden infrasructures have been reused to other ends over the years. In light of the reconfiguration of the national defense model, a large number of military spaces have been abandoned or decommissioned. As creations of human civilization, they constitute an important legacy that need to be preserved and reintroduced into “civil use.” The reuse of underground military spaces does not necessarily mean that their history is discarded or forgotten. Underground military heritage is a unique cultural resource that contributes to individual and collective identity and reflection on history.2 At the same time, continuous urban expansion and environmental degradation have brought attention to underutilized and abandoned spaces within the city. In this context, underground military infrastructure is an urban space with hidden opportunities.

The study begins with a global perspective on the value of underground military infrastructure, the challenges, and opportunities for reuse.3 It explores underground military legacy redevelopment trends with global cases studies and examines the transfer of property, and the impact of ownership on redevelopment. In particular, the study focuses on the underground shelter system in the Chinese city of Chongqing and explores the current reuse of shelters from the perspective of historical, spatial, economical, environmental, and social characteristics.4 Last, the research explores how these spaces representing war violence can be integrated into the contemporary urban fabric from the perspective of conflict and everyday urbanism theories.5 Then discusses the roles of government, designers, and citizens in the projects, how it responds to conflict and collective memory, and opportunities for replicability in other territories.

Underground Military Shelter, Collective Memory, Reuse, Conflict Urbanism, Everyday Urbanism.

Conflict Urbanism, Everyday Urbanism.

1. Yun, Jieheerah. “Bunkers as Difficult Heritage: Imagining Future for Underground Spaces in Seoul.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1 080/13467581.2021.1941980.

2. Paola Gatti, Maria. “Military Buildings: From Being Abandoned to Reuse.” Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.witpress.com/Secure/ elibrary/papers/DSHF14/DSHF14002FU1.pdf.

3. Bowles, Kasey Ryan. “Obstacles in the Reuse of Closed ... University of Georgia.” Accessed March 30, 2022. https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/ bowles_kasey_r_201208_mepd.pdf.

4. Wu, Hao. “Mountainous Shelter Space Versatile Utilization Study” Master Diss. Chongqing University, 2013

5. Lei, Lei. “Research on Urban Spontaneous Renewal Space-A Case Study in Chongqing” Master Diss. Chongqing University, 2010

Singapore was a nation island under colonial rule until 1965, when it became an independent and sovereign nation. In less than sixty years, the process of rapid and efficient urbanization has been nothing short of a miracle. The birth of the Republic of Singapore faced similar urbanization challenges than developing regions are facing today: overcrowding, slums, traffic congestion, environmental pollution, flooding, and water scarcity.1 Nevertheless, with effective governance and visionary integrated planning, Singapore has achieved a stable long-term dynamic balance between economic, social, and environmental goals in its urban-national territory.2

What has been the role of the government in Singapore’s outstanding urbanization? How are citizens, businesses, and other organizations involved in the making of a cleaner, smarter, and more sustainable city? This paper discusses these questions through a case study approach. In the Four National Water Taps, I use the lens of infrastructure urbanism, to shed light on how the government acted as initiator, investor, and mediator to address the problem of freshwater scarcity in Singapore by combining the technological capacity of private enterprises and social organizations with national policies and public-private partnerships. In the Garden City Vision, I use landscape urbanism lens to assess the role of the government as decision-maker, legislator, and supervisor in the green urban movement, and to explore how pragmatism is manifested through the three milestones. Lastly, I use the smart city urbanism lens to discuss the way in which the government plays as the instructor, builder, and operator of a smart nation in the digital transformation of Singapore. Open-source databases provide a platform for creative initiatives for businesses and citizens, while also allowing for brainstorming and full social participation in smart cities. Besides the formal urbanization, the Singapore government also plays as the supporter, protector, and manager to make contributions to the regeneration and redevelopment of informal settlements by advancing the Public Housing.

Singapore’s visionary government is committed to long-term thinking and efficient implementation in partnership with the market and citizens to brainstorm solutions to urban challenges. But highly centralized, vocal governments also risk leading to authoritarianism. In the case of garden cities, environmental authoritarianism may exclude social and environmental organizations from the urban green movement. And in the case of smart cities, the government may impose digital technologies despite residents’ concerns about digital divide and data insecurity. Urban design is a means of mediating between government policy and concrete implementation, seeking to protect the interests of all parties. In Singapore, due to limited and state-owned land and other natural resources, urban design is highly controlled by the government, but urban designers such as Grant Associates still created an extraordinary balance among landscape design, smart technologies and sustainable development sought by the national general plan.

Formal, Infrastructure, Sustainability, Smart, Informal.

Infrastructure Urbanism, Landscape Urbanism, Smart Urbanism.

1. TAY, JAMES. “Leveraging Singapore’s Urban Development Success.” World Bank Blogs. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://blogs. worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/leveragingsingapores-urban-development-success.

2. “Voluntary National Review Sustainable Development Goals Progress Report at the High Level Political Forum / Singapore.” United Nations. United Nations. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://digitallibrary.un.org/ record/3866731.

WHAT’S THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT IN SINGAPORE’S URBANIZATION?

Our world is increasingly filled with interactive, digitized devices in buildings and urban spaces. [1] Their presence impacts our experience of the built environment and shapes our daily life. [2] When cities turn to technology to build more livable environments, a digital divide emerges between different population segments, which might unintentionally leave some communities behind. The assimilation of buildings and urban spaces as interactive objects has become a new research domain, HumanBuilding Interaction (HBI), a domain within Human-Computer Interaction that specifically studies its relation to Architecture and Urban Design.[3] It is characterized in terms of dimensions representing the interaction space and modalities that can be invoked to enhance interactions.[4] Lim and Rogers’s study concludes that interactive technologies in public spaces effectively impact people’s emotions.[5] Yet the impact of both physical space and social context on how people engage with a public interactive display has rarely been studied.[6] Although interaction design brings people convenience, the transformation of the built under the impact of digital devices indeed excludes some public. Digital placemaking connects people with place. It is the augmentation of physical places with location-specific digital services, products, or experiences to create more meaningful destinations for all. Digital placemaking can be used to support citizens to shape public spaces, develop urban spaces, etc.

The interaction between physical objects and outdoor public spaces is a big focus of this research project since social activities are an integral part of the interplay.[7] How can urban designers bring more inclusive interactive environments? Methodologically, I will review literature related to past HBI experiences and summarize three main aspects that neglected a certain group of people during the urban evolution. Then, I will learn from two cases to demonstrate how these principles are being considered or applied. Finally, this study reflects the design principles and strategies for better inclusivity of the HBI in urban design, thus meeting people’s needs in the digital environment. The more seamless integration of environment and technology can ease human interaction.

Human-Building Interaction (HBI), Urban Space, Inclusivity, Design For All, User Experience, Digital PlaceMaking

URBANISMS

Digital Urbanism, Smart Urbanism.

1. Nembrini and Lalanne, “Human-Building Interaction.”

2. “Future of Human-Building Interaction Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems.”

3. Alavi et al., “Introduction to Human-Building Interaction (HBI).”

4. Nembrini and Lalanne.

5. “Designing to Distract: Can Interactive Technologies Reduce Visitor Anxiety in a Children’s Hospital Setting?: ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction: Vol 26, No 2.”

6. “Exploring the Effects of Space and Place on Engagement with an Interactive Installation Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.”

7. Gehl, Life Between Buildings.

ZHAOQI ZHU

The impact of industrialization and urbanization on humans and the environment is manifests in various ways, from challenges to access clean air and water, and curb waste and pollution.1 The current efforts to reestablish urban ecologies is centered on the synthesis of people, society, and nature, with a strong focus on sustainability.2 Along with acknowledging the deterioration of the environment and citizens’ desire to reconnect with nature, the paper focuses on the role of urbanf parks in bringing ecological benefits to the city.

China’s modernization has brought economic and technological progress along with environmental degradation. When surface water is depleted and groundwater is contaminated, how to restore once healthy soil and water conditions with the help of the latest science and technology? This paper examine the relationship between urban development and ecological systems through two case studies Freshkills Park in New York State with the Beach Restoration project in Qinhuangdao, China. Both projects areprevious landfills that have been transformed into parks for urban dwellers and wildlife. Since human civilization is part of the overall natural resources, all forms of life on earth are dependent on.3 The article will look at the impact on soil and renovation in Freshkills Park and on the city limits, and the treatment of waste piles in Tianjin South Cuiping Park and explore the connections between people and ecology, plants and ecology in order to summarize and organize the material flow in the area, and how the role of humans in this process has changed.

Ecosystems have a strong capacity for self-recovery and reverse succession mechanisms, however, today’s environment is subject to natural disturbances in addition to drastic anthropogenic factors”. Designers are increasingly confronted with seemingly worthless abandoned sites, landfills or other damaged areas, restoring the surface of the site in a landscape manner to promote the benign development of the site system. The renovated park creates open spaces between building blocks that provide spaces for the exchange of materials, energy, and information between people and nature. By exporting the energy flow, spatial form, ecology, and compatibility of parks in the city in terms of how contemporary parks develop as urban fabric, not just as urban infrastructure, functional or zoned areas4 By looking at the relationship between urbanism and the functioning of natural systems in parks of different scales, the restoration of the damaged urban fabric, and the integration of new parks into the urban fabric, the research explores the possibilities of park development from an ecological perspective5.