3 minute read

The Mobilization of Space as the Mobilization of Memory

1.1 Pilgrimage:

The Mobilization of Space as the Mobilization of Memory

Advertisement

In the case of The Rings of Saturn, the structure of the book takes place, precisely, through a ten-part guided narrative, each named according to the narrator’s pilgrimage route14 . The starting point is inscribed through the time and spatial record – August 1992, when the narrator started walking through Suffolk County, east of England, justifying the pilgrimage as a kind of attempt to escape the void after the conclusion of a long job.15

At the first approach, the question of the walker immediately arises the figure of a central narrator who incorporates this dimension. As the narrative progresses, the above justification takes on other shapes. Still, in this first moment of contact with the narrator – whose name is not identified – there is an important indication: the double perspective of the pilgrimage remembered as a pleasant sense of freedom and a way of contact with horror16 .

The tone assumed by the narrative is, from then on, driven by the pilgrim’s memories in a second moment, when he begins to take notes – mentally – a year after the beginning of the trip, when he is taken to the Norwich hospital in a state of almost total immobility17 . Here, the interaction between mobility and immobility is an important part of the perception of memory. Faced with the horror during the pilgrimage – and, because of it, paralyzed -, the narrator finds himself faced with the journey he has traveled, now even more powerful in the sense of the

14 Like part I (first chapter), names as follows: In the hospital – Obituary – Thomas Browne’s Skull Odyssey – Anatomy class – Levitation – Quincunce – Fable beings – Cremation. 15 “In August 1992, when the heatwave days were over, I started walking through Suffolk County, in the east of England, hoping to escape the void that spreads in me whenever I finish a long job.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 13, own translation) 16 “[...] In the time that followed, I was as much concerned with the memory of the pleasant sense of freedom as with the paralyzing horror that affected me at different times, in the face of the traces of destruction that, even in this distant region, went back to the most distant past.” (Ibid., page 13, own highlights and translation) 17 “[...] exactly one year after the day I started my trip, I was taken in a state of almost total immobility to the hospital in Norwich, the provincial capital, where then, at least in thought, I started writing these pages.” (Ibid., pages 13 and 14, own translation)

mobilization of memory. As he becomes an immobile spectator, he remembers a path that goes from the vastness of the previous summer to a single-blind and deaf spot in the hospital room18 .

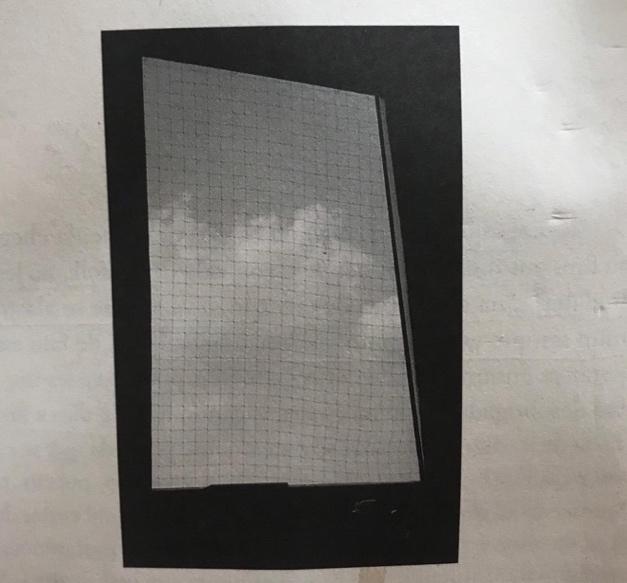

At this point, the narrator introduces an even more efficient visual resource: the photograph of the window of the room in which he was installed, on the eighth floor of the hospital [see Image 1]. The focus is on the absence of a landscape, with the exception of a barely significant section of the sky. From that moment on, the sense of space is strictly inserted as a narrative construction tool. The relationship with memory is an important part of the spatial mapping process identified below.

What can be suggested from the author’s procedure is the idea of pilgrimage as the very notion of memory. In the impossibility of physical pilgrimage, highlighted by the hospital episode, the navigation is established through the multiple spaces of memory. In the spatial notion incorporated by Sebald, both the act of pilgrimage

Image 1: Photograph of the hospital room.

18 “[...] I was overwhelmed by the idea that the expanses that had been covered the previous summer in Suffolk had now shrunk to a single blind and deaf spot.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 14, own translation)