15 minute read

Literary references in W. G. Sebald

Literary references in W. G. Sebald

Advertisement

The mediation between memory and forgetfulness through the word is shown right at the beginning of the narrative of The Rings of Saturn: immobilized in the hospital, the narrator feels the urgency to take notes - at least, mentally - of the entire journey of the pilgrimage. Attached to the cutout image of the hospital window, as pointed out in the chapter on Space, what happens is a kind of comparison with Gregor Samsa133 , famous character of Kafka - a constant literary reference in Sebald's work. It is noticeable, since the beginning, that kind of attraction of the written word that frequently emerges in the passages of the book.

It is in the record of the final point of writing by the narrator – one year after being discharged from the hospital, as already mentioned – that the references are inserted even more actively in the narrative. When evoking the figure of Michael Parkinson, whose trace of compatibility with Sebald himself gives evidence of the book's autobiographical tone134 a mention is made of Ramuz, also a writer. Here, it is important to return to the notion of the practice of walking linked to the literary activity, persistent evidence in Sebald's prose. In this sense, the author seems to follow the idea defended by Thomas Bernhard135 – another writer of his deep admiration: there is a permanent relationship between the act of walking and thinking136 .

132 The title in question was taken from the narrative of The Rings of Saturn (SEBALD, 2010, page (101). 133 “In the contorted posture of a creature that stood upright for the first time, I was leaning against the glass and involuntarily thinking about the scene in which poor Gregor Samsa, his trembling legs, climbs the chair and looks out of the room, with an indistinct memory, so he says, of the feeling of freedom that before allowed him to look out the window.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 15, (own translation) 134 Parkinson, like Sebald, was a professor of literature at the University of East Anglia. 135 Openly, a reference to Sebald, as can be extracted from the author’s interviews. In addition, Bernhard’s writings are the subject of analysis in the book The Description of Unhappiness, originally written by Sebald in 1985. 136 Bernhard writes in Walking [1971]: “Walking and thinking are in a perpetual relationship that is based on trust. Cit. by POPOVA, Maria – Thomas Bernhard on Walking, Thinking and the Paradox of Self-Reflection.

The mention of Parkinson is followed, shortly after, by the passage of Janine Dakyns, also a professor of literature and a staunch scholar of the work of Gustave Flaubert. In addition to the emphasis given to the obscure detail mentioned earlier, Janine's interest in investigating the fear of the false137 in Flaubert's writing draws attention. The difficulty that led him to not write for weeks or even months on end is explained as a response by the writer to the inevitable advance of stupidity138 . In addition to the literary reflection, it is important to highlight the allusion to sand, a relevant detail of the passage in question: for Flaubert, the attempt to write was close to the idea of sinking into the sand. The metaphor is a key point in Sebald's procedure, since the sand appears under the symbol of ephemerality and residue139 – something that refers to forgetfulness, but that resists140 .

Dakyns' character is also established as the link found to launch the next point of analysis141: the writings of the English doctor Thomas Browne. It is in this respect that the author's set of literary references around the ashes are actually configured. In Browne's case, the theme of the treatise on the practice of cremation and funerary urns, extensively addressed by Sebald, and the story described about Browne's lost skull142 closely corresponds with the author's intentions.

137 “[...] took a great personal interest in investigating the scruples that marked Flaubert’s writing, that fear of the false that, as she said, sometimes confined him to the couch for weeks or months on end […].” (SEBALD, 2010, page 17, own highlights and translation) 138 “Janine maintained that Flaubert’s scruples went back to the ineluctable advance of stupidity that he observed everywhere and, as he imagined, had already spread in his head. It was like, so they say he said once, as if the person sank in the sand. Perhaps for this reason, said Janine, sand was so important in her work. The sand conquered everything.” (Ibid., page 17, own translation). 139 ”Sand is one of the elements of Vanitas, dead-nature in which objects laden with symbolic values warn against the precariousness of human life [...]. […] Vanitas’ theme is constant throughout Sebald’s book, notable in the description of so many and so many sparkles of the past that have become opaque today.” (DANZINGER, 2017, page 133, own translation) 140 There is also the idea of return in the symbol of the sand: “Shifting and penetrable, sand adopts the shapes of the bodies resting in it and in this respect is a womb symbol.” (CHEVALIER; GHEERBRANT, page 825, own highlights) 141 “It was also Janine who indicated surgeon Anthony Batty Shaw to me, […] when, shortly after I was discharged from the hospital, I started my research on Thomas Browne, […] who had left a series of writings that barely allow comparison.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 19, own translation) 142 “Browne himself, in his famous treatise (half archeological, half metaphysical), on the practice of cremation and the funerary urns, offers the best comment about the later odyssey of his skull, when he writes that being scraped out of the grave was an abominable tragedy. But who knows,

When investigating in depth the records left by Browne - in particular, the archaeological perspective, so to speak, of the English doctor's treatise143 –, the narrator reveals perhaps the most significant vision of what can be understood as ash confirming the often pointed out residual character. What is shown throughout the entire book is the compatibility with Browne's explicit vision144 , the point of unfolding the entire narrative:

The invisibility and intangibility of what moves us, this remained a mystery also to Thomas Browne, who saw our world as the shadow of another world. [...] all knowledge is surrounded by impenetrable darkness. What we perceive are only isolated lights in the abyss of ignorance, in the building of the world immersed in deep shadows. (SEBALD, 2010, pages 27 and 28, own highlights and translation)

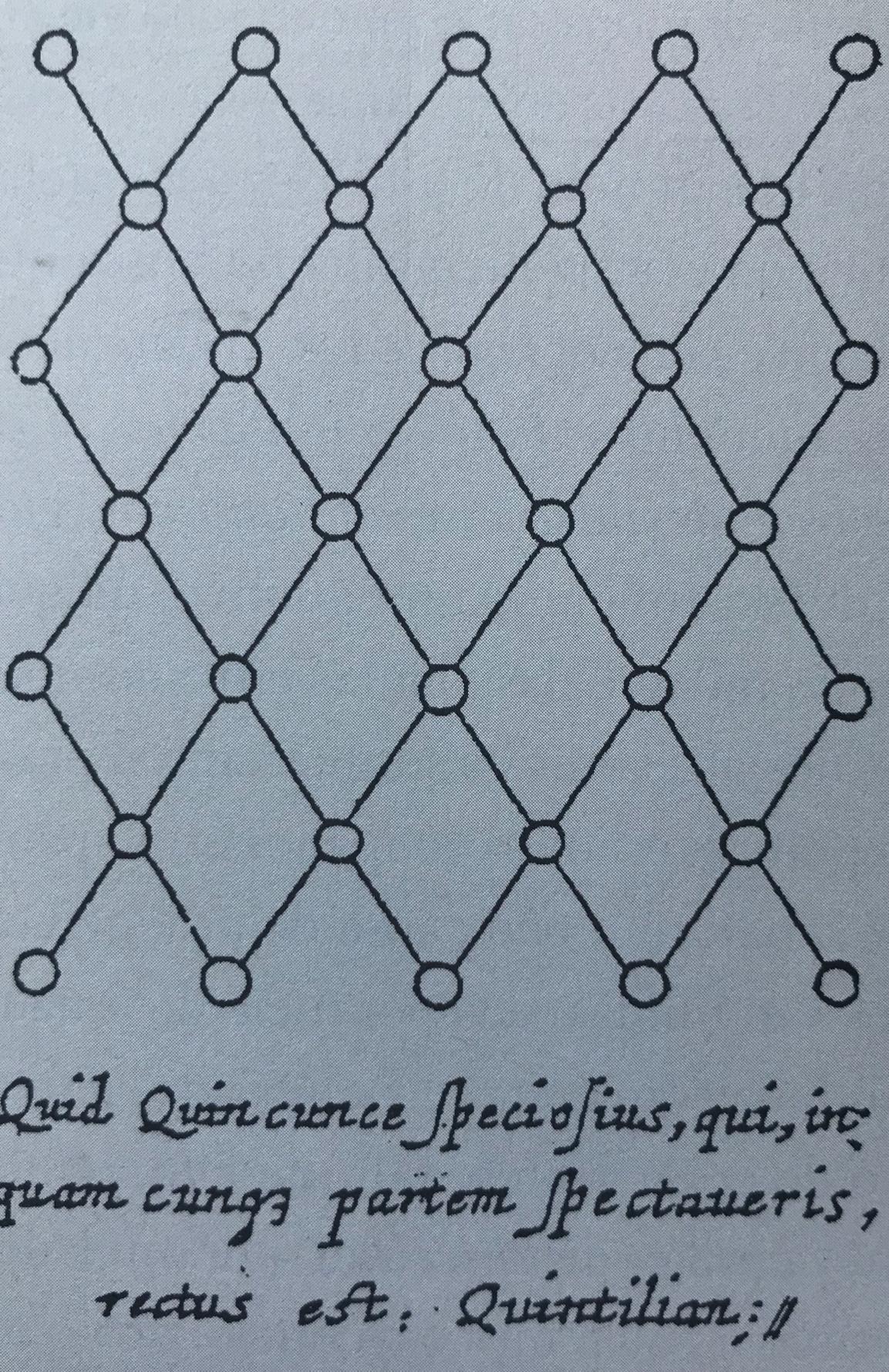

Still looking at the writings of the English doctor, Sebald rescues the essay on the Garden of Cyrus, in which Browne discovers a geometric structure - the quincunce145 [see Image 32] – found everywhere, whether in living or dead matter, and even in the works of art. Browne's intent recorded by the narrator, from this perspective, is to expose “patterns always recurring in the seemingly infinite diversity of forms”146 – or even, the idea that eternity resides in the reflection of the transitory nature.

he adds, the fate of his bones and how many times he will be buried?” (Ibid., page 20, own highlights and translation) 143 “[Browne’s] considerations are constantly returning to what came to light in the excavations field near Walsingham. It is amazing, says Browne, that the clay urns with such thin walls have been preserved unscathed for so long, half a meter from the surface, while plows and wars passed over them and large buildings […] crumbled and collapsed.” (Ibid., page 34, own translation) 144 It is important to point out the similarity between the narrative strategies of Browne and Sebald: “[…] Browne always boasts all his erudition […], working with metaphors and analogies of vast scope and constructing labyrinthine phrases, which sometimes extend for one or two pages, similar to processions or funeral processions in their pure prodigality.” (Ibid., page 28, own ihghlights and translation) 145 “Browne discovers this structure everywhere, in living and dead matter, in certain crystal forms, in starfish and sea urchins, in the vertebrae of mammals, in the backbone of birds and fish […] and in the works of art of man, in the pyramids of Egypt and in the mausoleum of Augustus, as well as in the garden of King Solomon […].” (Ibid., page 29, own highlights and translation) 146 “We study the order of things, but what is behind it, says Browne, eludes us. For this reason, it is appropriate to write our philosophy in lowercase, using the abbreviations and stenograms of the transitory nature, which exclusively reflect the reflection of eternity. True to the percept, Browne records the patterns that always recur in the seemingly infinite diversity of forms.” (Ibid., page 28, own highlights and translation)

Image 32: The quincune structure discovered by Thomas Browne.

In articulation with this idea, there is a kind of explanation of destruction as a process inherent in everything that exists, albeit under the bias of permanence again, a substantial view of what can be understood as ash. It is the clue left by Browne that opens up the possibilities explored throughout the book and introduces the symbol of the moth, constantly evoked in Sebald's narratives and which will be mentioned later:

And as the heaviest stone of melancholy is the inescapable anguish of our nature, Browne searches among what escaped annihilation147 for the traces of the mysterious transmigration capacity that he has observed so often in caterpillars and moths. (SEBALD, 2010, page 35, own highlights and translation)

The study of Browne's work also leads the narrator to introduce a reference to Libro de los seres imaginarios [1967], by Jorge Luis Borges. In the same way that the investigation of the patterns of nature fascinated the English doctor, the idea of the infinite mutations is also highlighted in Browne's descriptions. The trigger used by Sebald to establish the affinity between the two texts - by Browne and

147 It goes back to Browne’s writing about the funeral urns found in Walsingham, as already mentioned.

by Borges - is the attraction around the “chimeras born in our thought”148 . The two literary references persist in the narrative, which indicates Sebald's approach to the fantastic and the hidden senses149 .

In the context of the pilgrimage, the narrator focuses once again on Borges' writing – more precisely, on the short story Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius [1940]. Faced with the experience of visualizing a kind of “sea monster”, a delusion that came to the fore in the constant contact with horror, the pilgrim speaks of “our attempts to invent second or even third-degree worlds”150 . The short story to which it refers deals with a conversation between Borges' narrator and the writer Bioy Casares, in which they talk about the possibility of writing a novel – "that would challenge tangible facts and incur in several contradictions151 . Thus, few readers would be able to unveil the hidden reality of the narrative.

With reference to the short story, Sebald also suggests that he is not so committed to the real, despite the successive evidences shown in the book. There is an attempt by the narrator to document each step, but the attentive reader, as Sebald expects, is able to realize that there is something beyond that. In this sense, it is possible to fall into two perspectives: at first, the function of the imaginary as a way of transfiguring horror; in addition, the idea of fantasy as a component of memory152 – and therefore a central element to the writer's work.

148 “[...] in his compendium Pseudodoxia Epidemica, […], [Browne] deals with all kinds of beings, both real and imaginary […]. In any case, it follows from Browne’s descriptions that the idea of the infinite mutations of nature, which surpass all limits of reason, or the chimeras born in our thought were as fascinating to him as, three hundred years later, to Jorge Luis Borges, editor of Lo libro de los seres imaginarios […].” (SEBALD , 2010, page 31, own translation) 149 “[…] but the amazing monsters that we know exist in reality make us somehow suppose that the animals invented by us are not merely the fruit of imagination.” (Ibid., page 31) 150 “The memory of the uncertainty that I felt then brings me back to the aforementioned Uruguayan tale, which deals essentially with our attempts to invent second or even third worlds.” (Ibid., page 78, own highlights and translation) 151 “[...] the two had lingered in a conversation about writing a novel that would challenge the tangible facts and incur several contradictions, in such a way that few readers – very few readers – would be able to unveil the reality hidden in the narrative, an atrocious reality, but at the same time totally meaningless.” (Ibid., page 78, own highlights and translation) 152 According to Pascal Quignard (2018, page 63): “Thus, it is necessary to list at least three memories: the memory of what has never been (the fantasy); the memory of what was (the truth); the memory of what could not be received (the reality). […]. It is the strange bed of memory of the triple past: whether it has never been, whether it has been or has been refused.”

Borges' story also refers to the prospect of disappearance, by mentioning Tlön's labyrinthine construction153 . Still in relation to the possibility of accessing a hidden reality through the narrative, the pilgrim adds in his report that Tlön's project "intended to achieve, in the course of time, a new reality through the unreal”154 . It is precisely at this point in the book that Sebald's mapping strategy takes on a dubious characteristic: hitherto feasible, the places of pilgrimage seem to indicate a broader meaning. Later on, and perhaps as an answer, Sebald continues to weave his set of references and persists in the notion of ambiguity between destruction and ash, namely when articulating Borges and Browne:

The world will be Tlön. But I ignore it, concludes the narrator [by Borges], in the serene leisure of my country house, I continue to revise an indecisive translation, chosen in Quevedo, of Urn Burial155 , by Thomas Browne (which I do not intend to publish). (SEBALD, 2010, page 80, own highlights and translation)

In the manner of a weaver, Sebald allows the experience of the narrator to mix with the various accounts displayed in the book, as in the elaboration of a web. In addition to the prospect of exploring the layers of memory, referred to in the first chapter, the author comments on the need to create a type of periscopic narrative156 , in which the narrator constantly incorporates other people's narratives. For Sebald, the act of writing essentially consists of incessant

153 “Töln’s labyrinthine construction [...] is on the verge of extinguishing the known world.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 80, own highlights and translation) 154 “It remains unclear, therefore, whether Uqbar once existed or whether the description of this unknown country is not a case similar to that of Tlön, the encyclopedist’s project to which the main part of the story in question is dedicated and which he intended to achieve, over the course of time, a new reality through the unreal.” (Ibid. page 80, own highlights and translations) 155 Again, Browne’s text on the discovery of the funerary urns. 156 In an interview, Sebald refers to the influence of Thomas Bernhard’s writing: “He only tells you in his books what he heard from others. So he invented, as it were, a kind of periscopic narrative. […]. So Bernhard, single-handedly I think, invented a new form of narrating which appealed to me from the start.” (Id., 2007a, page 83 own highlights and translation)

elaboration157 . Somehow, this narrative strategy leads to an intertwining of the themes158 and points, mainly, to the author's continuous effort to retain.

It is in the pilgrim's passage through the Sailor’s Reading Room159 , a kind of maritime museum dedicated to the activity of sailors, that the possibility of literature is best seen as retention - and, evidently, as ash. When considering the “mysterious survival of the written word”160, the narrator identifies literature as a tool for accessing the traces161 . Here, the narrator's gesture seems to allude to the idea that “writing is hearing the lost voice”162 . It is also under this perspective that Sebald uses memoirs, the next point of appreciation. From the point of view of his own procedure163 , the author writes:

[...] But if I see the ribs from the past life, I always think: this has to do with the truth. The brain works continuously on the traces [...] [...] How far do we have to go back to find the beginning? (SEBALD, 2012b, page 79, own highlights and translation)

157 “Writing and creating something is about elaboration. You have a few elements. You build something. You elaborate until you have something that looks like something. […]. But the degree of elaboration is absolutely fantastical. It goes on and on and on and on.” (Id., 2007, page 114, own highlights) 158 “And I’ve always found that quite a good measure – that once things are going in a certain way that you can trust, the even in the writing process itself, things happen. […]. I think it’s the whole business of coincidence, which is very prominent in my writing. […] it seems to me simply an instance that illustrates that we somehow need to make sense of our nonsensical existence.” (SEBALD, 2007, page 96) 159 “There is in Southwold [...] the so-called Sailor’s Reading Room, an establishment of public utility that, being the sailors in danger of extinction, serves mainly as a kind of maritime museum, where all kinds of things related to the sea and marine life.” (Id., 2010, page 99, own translation) 160 “That morning, when I carefully closed the marble cover of the logbook, pondering the mysterious survival of the written word […].” (Ibid., page 101, own highlights and translation) 161 “First, [...] I flipped through the Southwold logbook, a patrol ship anchored in front of the pier since the fall of 1914. […] Each time I decipher one of these notes, I am amazed that a trace long gone in the air or in the water remains visible here on paper.” (Id., 2010, pages 100 and 101) 162 “To write is to hear the lost voice. It is taking the time to find the word of the enigma, to prepare your answer. It is looking for language in lost language.” (QUIGNARD, 2018, page 87, own highlights and transaltion) 163 Extract from the autobiographical part of the book After Nature.