16 minute read

Sebald’s writing architecture

1.4 Topographic speeches: Sebald’s writing architecture

It is within the scope of moving topography that Sebald arranges the layers of his speech. In the format of the reports that become denser around the narrator’s experience, as preciously mentioned, there is a sense of layers of memory –elaborated from the incessant spatial and time records and their correlations. It is through this almost archeological approach that the narrative is inscribed – with space actively participating in this function.

Advertisement

The main idea in Sebald’s work is an attempt to reconcile memory: because of the little we have managed to retain, an effort is needed to remember what is constantly in the process of being forgotten. In this sense, it is worth rescuing an enlightening passage from Austerlitz’s narrative:

Even today, when I try to remember, when I go back to examining the Breendonk crab plant56 (...), the darkness does not diminish, but thickens, /when I think how little we managed to retain because all things are constantly falling into the oblivion to each life that extinguishes, how much the world empties itself through the history of countless places and objects, in themselves incapable of memory/, never to be heard, never to be shown or transmitted. (SEBALD, 2012a, page 27, own highlights and translation)

Although the displacement goes back to the spatial instance of memory functioning – a thesis elaborated throughout this chapter – what is fundamentally capable of mediating the constant process between memory and forgetfulness is writing. It is at this point that the intention to rescue the ash through literature lies57 , a strategy that will be addressed in the third chapter. Before that, it is necessary to continue exploring the sources used by Sebald in the process of reconciling memory, such as the space category.

56 Military fortification in Belgium visited by the narrator of Austerlitz. 57 Still in Austerlitz, there is a clue to Sebald’s intentions, in accordance with the coincidences that are established between the character’s figure and the writer himself: “[…] because I wanted to put on paper my investigations on history or architecture and civilization, my long-standing intention.” (SEBALD, 2012a, page 112, own highlights and translation)

Upon returning to the pilgrimage in The Rings of Saturn, the narrator’s arrival in the city of Southwold summons a series of sediments from memory brought to the fore in the narrative. While contemplating the North Sea, the pilgrim recalls the episode of the Battle of Sole Bay, fought between England and Holland in 1672. In this passage, Sebald highlights the absurdity of vessels used in conflicts, which use is intended for annihilation58 . Further on, in convergence with the memory of Holland, the narrator’s meditation follows the memory of a previous pilgrimage through The Hague, which includes a small analysis of the painting by Jacob Van Ruisdael, View of Haarlem with Bleaching Fields59 [1665], seen in Mauritshuis. Here, it is relevant to highlight Sebald’s sense of space as an important point of appreciation of the image60 .

In the flow of writing that maps what he sees – and, in accordance with this idea, creates a topographic arrangement -, the author definitely reveals a concern in considering the landmarks of the landscape. This is how the narrator recalls the city of The Hague and the beach of Scheveningen [see Images 8 and 9], memories of previous pilgrimages61 . When approaching them through photographs, Sebald uses reminiscences as images – evocative, in turn, of a sense of dominance of space.

58 “The suffering agony and the whole mechanism of destruction far surpass our power of understanding, just as it is not possible to conceive the monumental effort that it took […] to build and equip vessels, almost all predestined to annihilation.” (SEBALD, 2010, pages 85 and 86, own translation) 59 Amongst the memories of the narrator’s pilgrimage, references are repeated, such as 17th century Dutch paintings, as Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson and Ruisdael’s painting. 60 “The truth is that Ruisdael did not position himself on the dunes to paint, but at an imaginary and artificial point, some distance from the world. Only this way was he able to see everything at the same time, the huge cloudy sky that occupies two-thirds of the painting, the city, which is little more than a fringe of the horizon […].” (SEBALD, 2010, page 90) 61 “[...] so it was impossible for me to believe, sitting on Gunhill in Southwold that night, that exactly a year earlier I had contemplated England from a Dutch beach.” (Ibid., page 88, own translation)

Image 8: Façade of a degraded building found in The Hague.

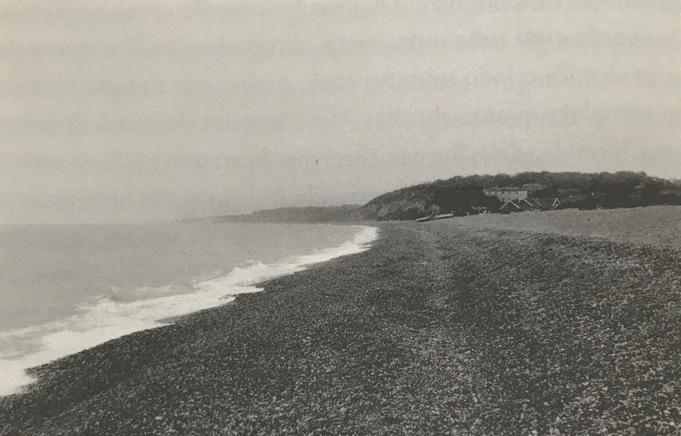

IMAGE 9: Scheveningen beach landscape.

It is also in Southwold that the narrator presents the life trajectories of Roger Casement and Joseph Conrad, both pilgrims par excellence62. The starting point is given by the mention of a documentary about Casement seen at the hotel63 , which is why the narrator seeks to reconstruct the narrative about the encounter between Casement and Conrad – witnesses of the horrors of the colonization of Congo. At this point, Sebald’s account essentially mixes historical sources and travel diaries and soon becomes a tangle of memories and references around the ashes. On the question of space, he inquires about the representation of historical monuments, such as the Lion Monument and the entire memorial of the Battle of Waterloo, rescues from a previous passage by the narrator in Belgium:

What about all the bodies and remains? Are they buried under the monument's obelisk? Are we standing on a mountain of the dead? Is this, after all, our point of observation? Do we really have the infamous historical synopsis to such an extent? (SEBALD, 2010, own highlights and translation, page 130) The experience of architecture, in this case, goes back to the vision of destruction from a historical perspective. In other books, Sebald compiles his strong interest in architectural knowledge, a relevant point of connection to deal with the topic of destruction. In Austerlitz, there are even technical reports in the buildings and images of the architectural designs of military fortifications, a pertinent example within the cluster of the author’s references:

[...] it is often our most ambitious projects that most obviously reveal the level of our insecurity. It can be said that the construction of fortifications [...] shows well how we feel forced to continually surround ourselves with defenses [...]. (SEBALD, 2012a, page 18, own highlights and translation) [...] because in some way we naturally know that the oversized buildings already cast the shadow of their destruction, conceived from the origin

62 During the Belgian colonization project in Congo, the Irishman Roger Casement exercised the function of British consul, reporting the horrors seen in the African country to foreign services. Conrad, for his part, was born in Poland under the context of the Russian occupation and lost his parents prematurely, a fact that led him to live in several cities in Europe. The unusual desire to become a sailor, as Sebald reports, led him to initiate life at sea, even reaching Congo, where travel reports gave origin to the book Heart of Darkness. 63 Until then unknown by the narrator, the figure of Roger Casement emerges with great importance: in addition to being a British consul in Congo, he participated in the Irish independence movement, being executed for high treason in 1916, under the pretext of maintaining homosexual relations.

with a view to a future existence as ruins. (SEBALD, 2012a, pages 22 and 23, own highlights and translation)

When resuming the topographic arrangement provided in The Rings of Saturn, Sebald weaves an intricate network of comments according to the narrator’s pilgrimage situations. This is the case observed in the walk between Southwold and the village of Walberswick, where the pilgrim contemplates the bridge over the River Blyth, naturally in a state of neglect. From this passage, the author mentions a series of passages that recall the decadence of the Empire of China64 . Here, there is one more quote referring to the railways, the original function of the bridge built over the Blyth. Sebald’s obsession around railways remains – a possible emblem of pilgrimage as well.

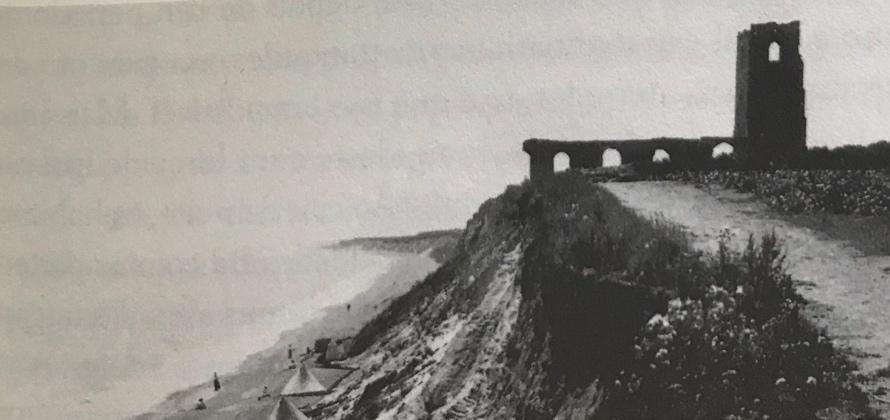

Continuing the narrator’s journey, perhaps the most important spatial record in the entire book is in his passage through Dunwich, a city eroded by the movement of the sea [see Image 10]. To think about the ordered pattern of destruction, Sebald uses the concept of time, a reference always present in the writer’s narratives. For Sebald, the activity of memory is not exactly due to the common sense of returning to the past, but by the negation of the notion of time65, in which memory would be a set of interconnected space66 . Under this perspective, the Dunwich ruins represent Sebald’s maximum effort to associate time with the sense of space [see Images 11 and 12], in which the formalization of destruction is, simultaneously, the maximum perspective of permanence67 . The narrator’s passage through Dunwich is also justified by its importance as a pilgrimage center:

64 “The bridge over Blyth was built in 1875 for a narrow-gauge railway that connected Halesworth to Southwold and which wagons, as several local historians cliam, were originally intended for the Chinese emperor.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 142, own translation) 65 In this passage from The Rings of Saturn, Sebald cites as reference the short story Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, by Jorge Luis Borges: “The denial of time, says the Orbis Tertius writing, is the most important principle of Tlon’s philosophical schools.” (Ibid., page 157, own translation) 66 For this articulation, it is necessary to return to the narrative of Austerlitz: “I don’t think we know the rules that govern the return of the past, but rather I feel more and more that time does not exist, on the contrary, there are several spaces that are interconnected […].” (Id., 2012a, page 168, own translation) 67 “[...] so that the slowly dying city described – let’s say, by reflex – one of the basic movements of human life on Earth.” (Id., 2010, page 161, own translation)

Dunwich, with its towers and several thousand souls, dissolved in water, sand and gravel and in the thin air. When you look at the sea from the top of the hill, in the direction of where the city must have once been, you feel the powerful sip of the void. Perhaps this is why Dunwich became a sort of pilgrimage center for melancholic writers in the Victorian era68 . (SEBALD, 2010, page 162, own highlights and translation)

68 Like Algernon Swinburne, mentioned by Sebald in the Dunwich section, whose reference will be covered in the third chapter.

Image 10: Dunwich Coast.

Image 11: Ruins of All Saints, the only church that lasted in Dunwich. Image 12: Tower of the old Eccles Church Tower.

Although the role of ruin calls for destruction and, of course, ash, Sebald rekindles its relationship with life, by attributing to the tragedy the sense of an ordered pattern and by giving meaning through it69 . In the mapped topography of the book, the movement through space recognizes destruction on several levels70 , namely in the hidden landscapes of the pilgrimage, as the stretch of the walk between Dunwich and the village of Middleton:

Just as forests had once colonized the Earth in random patterns, growing together gradually, so now ash fields devoured the world of green foliage in an equally random way71 . (SEBALD, 2010, page 171, own highlights and translation)

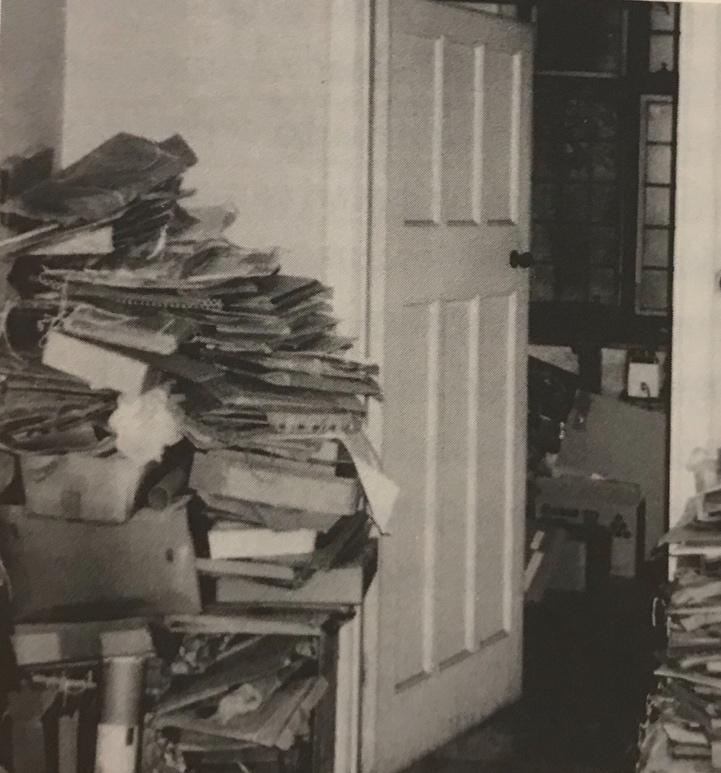

Finally in Middleton, the narrator seeks the home of Michael Hamburger, a writer who lives in the English village. As in the previous procedures, there is an imminent connection between the characters, almost to the point of being explained by the author. Again, in contact with Sebald’s life trajectory, it is possible to understand who Hamburger is: translator and personal friend of the author, whose identification is clear in the introduction written by Hamburger in Unrecounted [2004], Sebald’s work published posthumously.

It is through Hamburger that the narrator openly introduces one of Sebald’s characteristic themes: exile. In the face of the loss burden experienced by Hamburger when he had to leave Berlin as a boy, Sebald explores – repeatedly from the notion of space – erasure images, but also of memory permanence72 . In this record, mappable topography is, above all, a mental topography:

If I look back to Berlin today, writes Michael, I see nothing more than a bluish-black backdrop and a gray stain on it (...). Perhaps this blind

69 “[…] when you’re looking at the past, even if you redesign it in terms of tragedy, because tragedy is still a pattern of order and an attempt to give meaning to something, a life or a series of lives.” (SEBALD, 2007, page 58) 70 “[…] a landscape in constant creation, a landscape whose improbable order is determined by its changeability and precariousness” (DARBY, 2006, page 275) 71 “[...] everything is combustion, and combustion is the most hidden principle of each object we produce.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 172, own translation) 72 “[…] How little has remained in me of my native country, constata o cronista ao repassar as poucas memórias que lhe ficaram, apenas suficientes para um obituário de um garoto desaparecido.” (Ibid., page 178)

spot is also a post-image of the ruins I wandered through in 1947, when I first returned to my hometown to look for clues of the time that had eluded me. (SEBALD, 2010, page 179, own highlights and translation)

It is also due to the link with Hamburger that the importance of the theme of the house in Sebald’s writing is better perceived. When contemplating the spaces of the house in Middleton, the narrator activates a dimension of memory linked, essentially, to identity. The subjective bond with space is evident in this passage and reveals yet another identifying feature between the narrator and Hamburger73 . Ahead, there is a return to the theme of the house, now under the look of ruin. When talking about the stay at the Ashburry family home, reminiscent of a previous pilgrimage through Ireland, it is noticeable the approach of space as a privileged point of connection with memory: from the detailed description of the houses’ decay process, there is evidence of personal decay74 . Here, Sebald’s literary procedure is almost architectural and recalls the words of Manuel António Pina, in How to draw a house:

A house is the ruins of a house, a threatening thing waiting for a word; draws it like someone who holds remorse with some degree of abstraction and without a strict plan. (PINA, 2011, page 9, own highlights and translation)

Images 13 and 14: Photographs of Michael Hamburger’s house.

73 “[...] the idea totally contrary to reason took possession of me, I confess, that these things - the sticks for the fireplace, the envelopes, the preserved fruits, the seashells and the sound of the sea inside them – had survived me and that Michael was leading me through a house where I myself had lived a long time ago.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 185, own translation) 74 “But no one was willing to buy the house, which was increasingly abandoned, and so we were stuck to it like lost souls at their place of torment.” (Ibid., page 220, own translation)

In the remembrance work carried out by Sebald, the intention to map is accentuated by the presence of a map of the Ofordness region [see Image 15], one of the final destinations of the pilgrimage. In addition to placing another record, the map gives a kind of legitimacy to the topographic procedure visualized throughout the book75 . Ahead, and increasingly confused about the weight of the pilgrimage76 , the narrator reflects on the memoirs of the Viscount de Chateaubriand, one of the writers punctuated in the narrative:

The chronicler who was present and remembers what he saw inscribes his experiences, in an act of self-mutilation, in his own body. By writing, he becomes the exemplary martyr of the destiny that Providence has in store for us, and, still in life, already sees himself in the tomb that his memories represent. (SEBALD, 2010, page 254, own highlights and translation)

From the meditation on Chateaubriand, it is possible to extract the idea that the experience of walking inevitably enters the writer’s body. When unveiling the section in question, there is the recognition of life in the ashes77 – here, represented by the notion of memory. Ultimately, Sebald compares pilgrimage to life: it is the various stations of the journey that compose the idea of a journey78 . It is also through Chateaubriand’s memoires that the narrator makes the circular movement so characteristic of the book79 and makes a final record of space: in Ditchingham80 , 10 years ago, under a cedar dated from the beginning of the creation of the park [see Image 16]. The inserted photograph raises one of the

75 “I had been studying the curious formations of the Orford coast on the map and was interested in the so-called extraterritorial land language of Ofordness, which stone by stone, in a period of millennia, had moved from the north towards the mouth of the River Alde, so that in the low tide, known as Ore, it runs for about twenty kilometers just behind the current coastline or in front of the old line.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 232, own translation) 76 “[...] and at the time I knew as little as now whether my lonely journey was more of a pleasure or a torment.” (Ibid., page 239, own translation) 77 MOLDER, Maria Filomena – Um Soluço Ardente. In Rebuçados Venezianos. 78 When referring to Chateaubriand’s memoirs, especially with regards to the Viscount’s travels, the narrator points out: “(…) these are just some of the stations of the journey that now comes to an end.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 255, own translation) 79 “It is there that [Chateaubriand] begins to write his memories, and writes, at the very beginning, of the trees he planted and which he takes care of with his own hands. Now, he writes, they are still so small that I shade them when I stand between them and the sun. But one day, when they grown, they will give me back the shade and protect my old age, just as I protected their youth. I feel attached to the trees, I write sonnets and elegies and odes to them; they are like children, I know them by name and my only wish is to be able to die under them.” (Ibid., page 260) 80 The region in which Chateaubriand lived part of his youth.

uncertainties of the narrative and proposes a connection with the next chapter, dedicated to the topic of the image: could it be Sebald himself?

Image 15: Map that reveals the highlight for the Ofordness extraterritorial land strip.

Image 16: Could the photograph indicated as the last record of space in the book be of Sebald himself?