8 minute read

Photography as residue

2.2 Ton infix the image in the memory106:

Photograph as residue

Advertisement

Sebald’s writing architecture accommodates, amongst its pillars, a relevant point: the presence of black-and-white photographs, arranged according to the progress of the narratives. As one gets in touch with the author’s work, it is possible to say the use of photography reinforces its peripheral position in dealing with the image: there is often no more significant mention of the origin of the records. Still, in relation to this, it is also worth noting some effort to change the quality of the photographs107 , a strategy that highlights the condition of residue.

It is important to go back, first of all, to the heart of Sebald’s interest in photographs. According to the author, photography is a kind of manifestation of the dead, something that calls for a certain spectral presence108 . Sebald’s point of view relates to a very familiar notion about death, still derived from his postwar experience. However, it is in a text dedicated to the notes on cinema written by Kafka109 that Sebald is closer to what he means by photography. First, the compatibility with Kafka’s view of the progressive annulment110 – or approach of death – made explicit by the photographs. In the text in question, there is an even more conclusive passage:

(...) we can assume that the erotic radiation of these images, of these snapshots (…) is due to their proximity to death. (…) The look that reveals everything, that penetrates everything has the underlying force of repetition. It always wants to make sure it saw what it saw. All that remains is to look, an obsession in which real time is suspended while the dead, the living, and the unborn, as sometimes happens in dreams,

106 Title of a work by the artist Vija Celmins [To Fix the Image in Memory], borrowed here for the similarity with Sebald’s procedure in relation to the use of photographs. 107 “We do also have to know that these seemingly deteriorating and deteriorated pictures are very largely made to be that. He’s fabricating these things.” (RYAN, 2017) 108 “And photographs are for me […] one of the emanations of the dead, especially these older photographs of people no longer with us. Nevertheless, through these pictures, they do have what seems to me some sort of a spectral presence.” (SEBALD, 2007b, page 40) 109 See SEBALD, W. G. – Kafka no cinema. 110 “[...] as so often happens when we look at old photographs, it leaves him terrified [referring to Kafka] with the progressive annulment of his person and the approach of death.” (SEBALD, 2014a, page 149)

all come together on the same plan. (SEBALD, 2014a, page 147, own highlights and translation)

The idea of dissolution denounced by the photographs underlies Sebald’s continued interest in the way of dealing with images. Regarding Kafka’s notion, the progressive annulment, would have its origin in the fact that the copy lasts even after the copied one disappears111 , an astonishment that seems to remain in Sebald’s narratives. On the other hand, the copy sustains the strength of repetition, a process that allows, in Sebald’s understanding, a suspension of time. The getting used to the image of death112 provided by the photographs, therefore, comprises a double perspective: sometimes of astonishment – or even of terror , sometimes of combat against forgetfulness.

As was said in relation to architecture in the process of destruction, Sebald also seems to opt for the retention charge of the photographic image. In addition to the aesthetic sense, a concern confirmed by the writer113 , the use of photography is an attempt to rescue in the uninterrupted flow of things that are constantly falling by the wayside. Once again, there is an ambiguous sense: at the same time that the copy is originally made to last, Sebald recognizes the nomadic aspect of photography - something that is easily lost and has the slightest chance of survival114 .

In effect, the writer is especially attentive to this condition of residue. In Austerlitz, a narrative that Sebald identifies as closest to an elegy115 – coincidentally, the last book published in life – the effort to remove the photographs from oblivion

111 “And since the copy lasted after the copied one disappeared, there was an uncomfortable suspicion that the original, person or nature, has a lower degree of authenticity that the copy, that the copy wore out the original, in the same way that is said that whoever finds their doppelgänger senses their own destruction.” (SEBALD, 2014a, page 148, own translation) 112 Term used by Maria Filomena Molder, quoted previously in reference to the narrator’s coming to his senses. 113 Asked about the use of photographs, Sebald confirms: “There is primarily an aesthetic sense.” (SEBALD, 2014b) 114 “The photograph is meant to get lost somewhere, is a nomadic thing that has a small chance to survive.” (SEBALD, 2014b) 115 “I think this one [Austerlitz] is much more in the form of an elegy, really, a long prose elegy.” (SEBALD, 2007c, page 103)

seems to be even greater. In this perspective, photography comes with the primary function of retaining and rescuing memory:

One has the impression, [...] that something in them moves, as if we catched moans of despair, [...], as if the images have a memory of their own and remember us, the survivors, and remember us who we were and who the others were, those who are no longer with us. (SEBALD, 2012a, page 166, own highlights and translation)

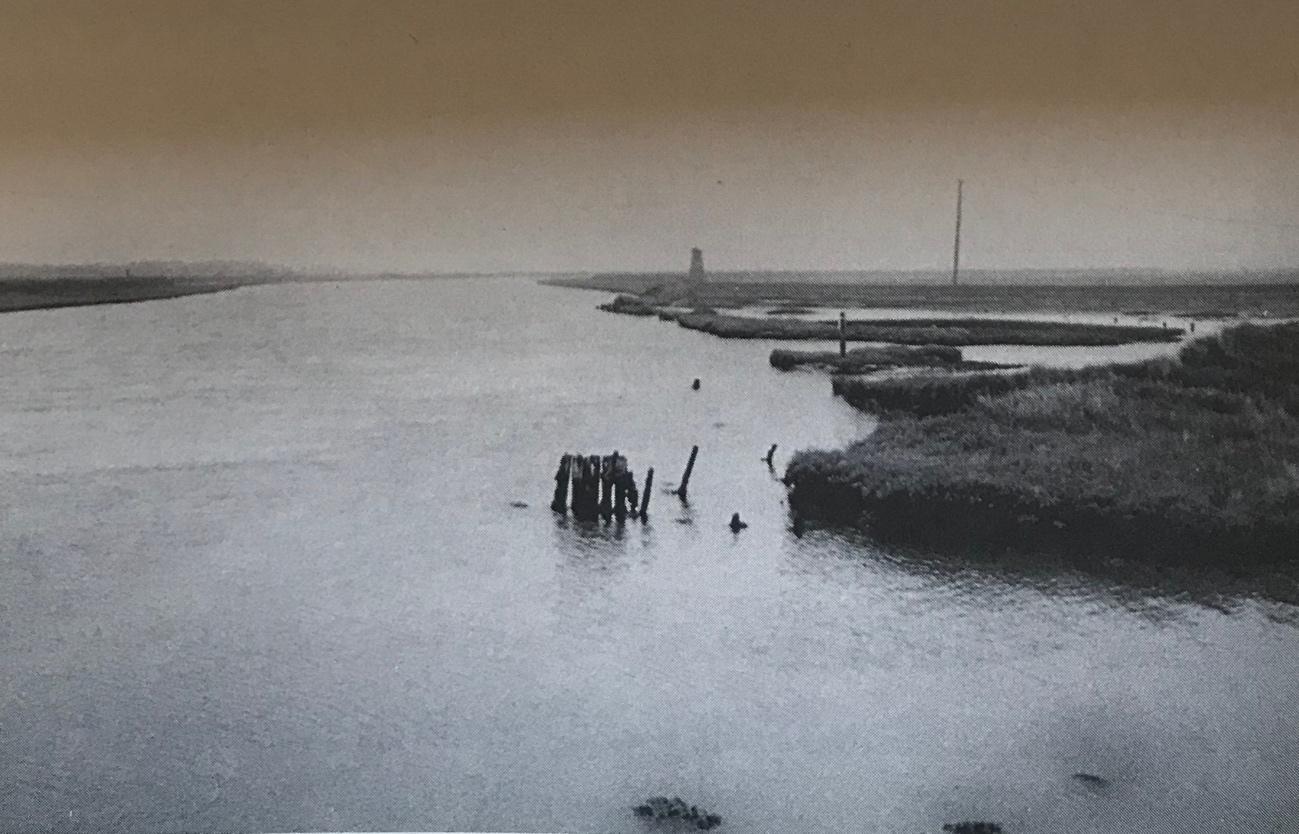

Image 25: Photograph attributed to the character Jacques Austerlitz.

In The Rings of Saturn, on the other hand, the measure of elaboration seems to be different: the idea of retention remains, but the fight against forgetfulness incorporates an even wider scale in terms of destruction and catastrophe. Here, the need to erect a memorial takes on the tone of a compendium, under the warning that in every new form the shadow of destruction already resides116 . If

116 “In a similar way to this continuous process of consuming and being consumed, in Thomas Browne’s view there is nothing left. In each new form the shadow of destruction already resides. It is that the history of each individual, of each society and of the whole world does not describe an arc that expands more and more and gains in beauty, but an orbit that, once reached the meridian, inclines towards the darkness.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 32, own translation)

nothing survives the simultaneous process of creation and destruction, a reflection guided by Thomas Browne, memory would be the vestige itself - or, again, the ash. It is precisely in this direction that the set of photographs in the book focuses

In the context of the narrative, the photographs mainly anchor the pilgrimage path. Amidst the constant references that evoke death, aberration and catastrophe, what seems to stick to memory are the images of abandoned landscapes. For Sebald, it is about witnessing what surpasses us117 – vestiges left by a species that becomes increasingly monstrous in the course of the civilization's progress118 . Amongst newspaper clippings, diverse illustrations and other resources that add to the book, it is the photographs that effectively denote the residue - and that are, as it were, a manifestation of ash [see Images 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31119].

As Sebald rescues via Kafka, “the images are beautiful, we cannot do without them, but they are also a torment.”120 In order to erect a memorial, a greater possibility of combating forgetfulness, it is necessary not only to appeal to the memory of the dead, but to reconstruct the moment of pain121 – an experience that can be translated in the context of the pilgrimage as a whole. In addition to

117 “Because (in principle) things outlast us, they know more about us than we know about them: they carry the experiences they have had with us inside them and are – in fact – the book of our history opened before us.” (Id., 2004, page 86) 118 In a text about Jan Peter Tripp’s work, which actually reflects Sebald’s own position: “The reverse side of this depiction of a species becoming more and more monstrous in the course of a civilization’s progress is the study of the abandoned landscapes and specially the still lifes in which – far beyond the events – only the motionless objects now bear witness to the former presence of a peculiarly rationalistic species.” (Ibid., page 86) 119 Here, similar to the strategy used in the book, the images are displayed without a caption. 120 “My dear, he writes [Kafka] to Felice in a photograph in which she looks at him sadly, ‘the images are beautiful, we cannot do without them, but they are also a torment’.” (Id., 2014a, page 146, own translation) 121 According to Sebald’s article on the German writer and painter Peter Weiss: “[…] the abstract memory of the dead is of little use against the attraction of amnesia if it does not also express sympathy […] in the study and reconstruction of the concrete moment of pain.” (Id., 2014c, page 97, own translation)

the rescue through space and image, the fight against the art of forgetting122 is, eminently, written. It is this last mediation, therefore, that will be examined below.

122 Sebald writes about Weiss: “[...] the struggle against the ‘art of forgetting’ that is as much a part of life as melancholy or death, a struggle that consists in the constant transfer of memory to written characters.” (Id., 2014c, page 97, own translation)