13 minute read

A guide through the obscure detail 2.2 To infix the image in memory

2.1 The itinerary of the image in The Rings of Saturn:

A guide through the obscure detail

Advertisement

As pointed out in the previous chapter, Sebald’s work relentlessly makes use of the visual resource – notably, the black-and-white photographs that illustrate almost all of his books89 . In The Rings of Saturn, the writer makes use of a set of diverse sources to assure the role of the image in the narrative: either from photography, which origin is unknown90 , either from the work of art through illustrations and clippings from the references used by Sebald. There is still the presence of the symbol, an element of strong reverberation in the text.

At first glance, the insertion of the photographs seems to indicate a kind of feasible example of the pilgrim’s experience. As already seen, as the pilgrimage progresses, the photographic record follows the itinerary of the displacement –interspersed, in turn, by the images that are recalled to the narrator’s memory. Despite the autobiographical tone, there is no consistent evidence to prove the link between these records and Sebald’s authorship. In practice, what is noticeable throughout the narrative is a constant attempt to promote a certain ambiguity – centered especially on the narrator’s figure and in the inserted photographs91 .

According to Sebald himself, there are possibly two objectives in the use of the photographs arranged throughout the text: the first is that of verification since the photograph is capable of legitimizing, in principle, the story told by the narrator; the second concerns an effort to apprehend time in the narrative, something that

89 With the exception of the long prose poem After Nature [Nach Der Nature, 1988], mentioned earlier. 90 “The photographs have neither captions nor credits to give a clue to their provenance; the text describes the taking of some of them, while others seem to be more generally illustrative, and still others entirely random.” (FRANKLIN, 2007, page 123) 91 “The conflict between fact and fiction reaches its epitome in the voice that narrates all these stories of loss […]. Yet these details, like the photographs, obscure as much as they reveal.” (Ibid., pages 124 and 125)

brings reading closer to a fruition experience more compatible, for example, with the visual arts. Sebald’s intent with the image, in this sense, would correspond to a form of redemption found, mainly, in the exercise of contemplation92 .

The redemption to which the writer refers is experienced by the reader at the beginning of the narrative, essentially through the work of art. Before going into this aspect more properly, it is necessary to clarify that, for Sebald, there is a comparative factor: while the photographic image tends to a kind of tautology93 ,

Image 18: Photograph inserted as a part of the pilgrimage context.

92“I think they have possibly two purposes in the text. The first and obvious notion is that of verification – we all tend to believe in pictures more than we do in letters. […]. So the photographs allow the narrator, as it were, to legitimize the story that he tells. (…). The other function that I see is possibly that of arresting time. […] And as we all know, this is what we like so much about certain forms of visual art – you stand in a museum and you look at one of those wonderful pictures somebody did in the sixteenth or the eighteenth century. You are taken out of time, and that is in a sense a form of redemption […].” (SEBALD, 2007b, pages 41 and 42) 93 Here, Sebald rescues Susan Sontag’s writings: “The photographic image turns reality into a tautology. When Cartier-Bresson travels to China, Susan Sontag writes, he demonstrates that there are people in China and that these people are Chinese.” (SEBALD, 2004, page 89)

the work of art requires a notion of ambiguity and versatility – something like the resonance of an obscurity that simultaneously generates illumination94 . There is also a distinction regarding the idea of the proximity of life to death: while this would be the very theme of art, Sebald understands it as the addiction to photography. At his point, the author resorts to the understanding of the photographic record as the residue of a life that perpetually vanishes95 , a perspective that clearly relates to the notion of ash and that will be addressed below.

When Sebald reinforces the ambiguity regarding art, he seems to direct this intent also to the photographs in his narratives. It is the sense of versatility highlighted by the author previously that guides his procedure in relation to the image. In the case of The Rings of Saturn, the first most incisive reference to the work of art comes from a conversation between the narrator and Janine Dakyns96 , a character introduced shortly after the mention of Michael Parkinson. Dakyns, also a teacher and a friend of Parkinson’s, presents the notion of the obscure detail –borrowed here by analogy with Sebald’s procedure. In the passage, the narrator alludes to Dürer’s melancholy angel and invokes, through the reference to the work of art, the idea of permanent coexistence that is noticeable in the book:

When I once told her that, sitting amongst her papers, she looked like Dürer’s melancholy angel, immobile amid the tools of destruction, her response was that the apparent disorder of her things actually represented something like a perfect order or that aspired to perfection. (SEBALD, 2010, page 19, own highlights and translation) Interestingly, Dürer’s engraving is not inserted in the body of images of the work. In addition to indicating the possibility of knowledge as a tool for access to

94 Right after the excerpt in which Sebald highlights the thinking of Susan Sontag, referred to earlier: “What may be right for photography, though, is not fitting for art. It needs ambiguity, polyvalence, the resonance of a darkening and illumination, in short, the transcendence of that which in an incontrovertible sentence is the case.” (Ibid., page 89) 95 “Roland Barthes saw in the by now omnipresent man with a camera an agent of death, and in photography something like the residue of a life perpetually perishing. What distinguishes art from such undertaker’s business is that life’s closeness to death is its theme, not its addiction.” (Ibid., page 89) 96 Dakyns succumbs to illness shortly afterward due to the inability to bear the mourning of Michael Parkinson’s death. Under this bias, Sebald incorporates the chain effect of destruction –a significant part of the development of the narrative.

destruction, Sebald seeks to signal the existence of a symbolic charge that runs through the entire text: the image of immobility – an inherent attribute of the melancholic97 – remains in the most varied situations, whether in the period experienced by the narrator in the hospital, or in the analysis of Dakyns workspace98 . It is interesting to note once again, the doble aspect of the narrative, guided simultaneously by the uninterrupted movement of the pilgrimage and the persistence of immobility.

With the mention of Dürer’s work, it is already possible to identify the attempt to access what is hidden – a current procedure in the author’s modus operandi and

Image 19: Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I, 1514. Highlidght to the figure of the immobile angel amid the tools of destruction, as referred by Sebald.

97 “We know that slowness is an attribute of the melancholic.” (DANZINGER, 2007, page 128) 98 “It is interesting to note that all of Sebald’s characters seem to be caught up in a dark thread of meaning that brings them together in near immobility. As much as Janine Dakyns made progress in collecting data that would contribute to Flaubert’s through and exhaustive analysis, the more she seems stuck with her proliferation of papers.” (DANZINGER, 2007, page 131, own translation)

which is unfolded throughout the narrative. In this sense, the ambiguity of the image is its strong point par excellence, something that guarantees the reach of what is not given in an evident way. To resume Dakyn’s words, now directed at the question of the image, only the obscure detail of the artwork is able to guide the look to the notion of ash – here mainly related to the perspective of something covered up, hidden, and, even so, reminiscent.

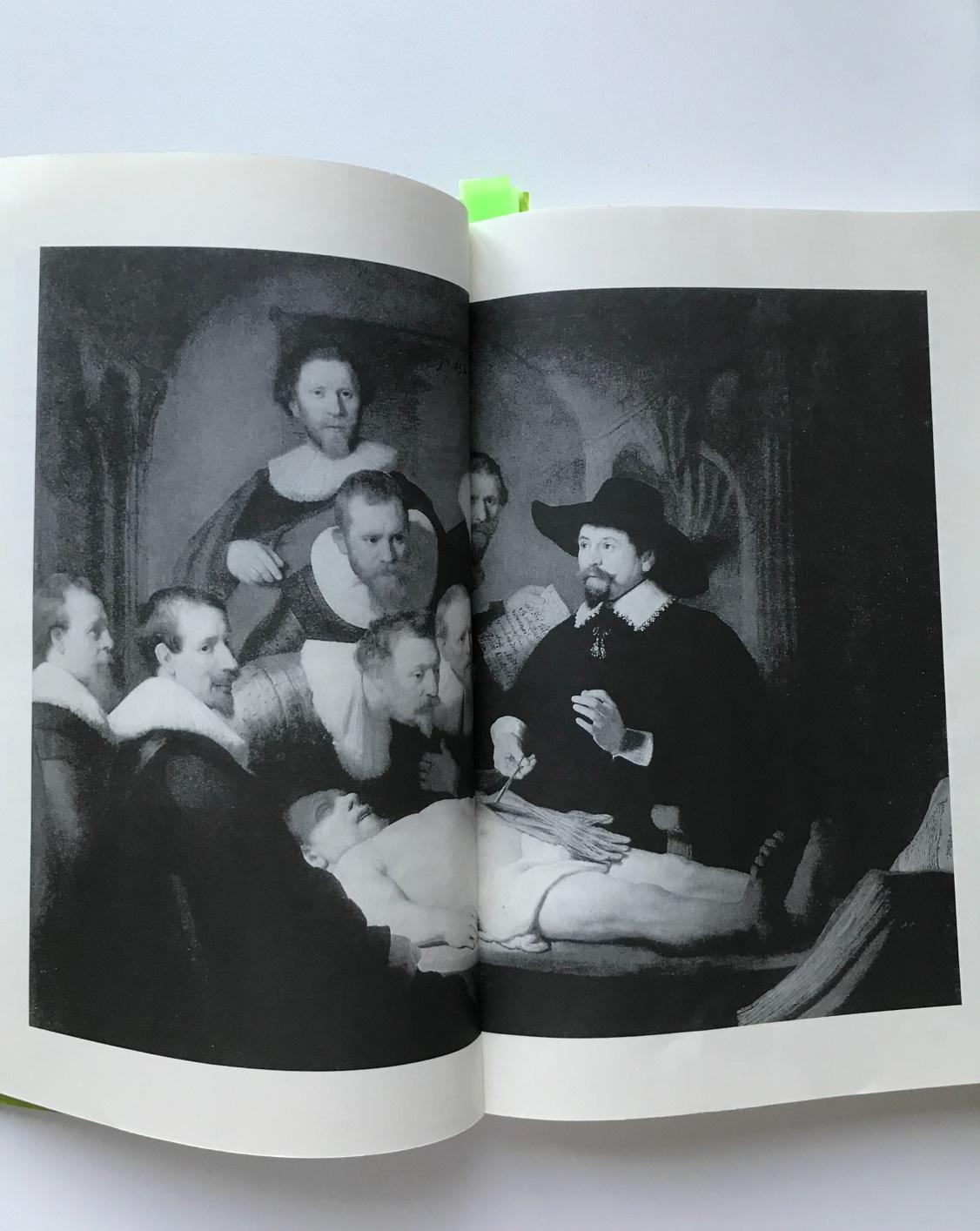

The best example of this procedure is ensured by the narrator’s reference to the Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp, a famous painting by Rembrandt dated 1632. It is through a passage dedicated to the writings of Thomas Browne99 , a possible spectator of the dissection recorded by Rembrandt100 , that Sebald establishes a unique point of convergence and develops a detailed analysis of the work. Here, the author also explores, in a more effective way and through the work of art, the aforementioned experience of redemption. Sebald’s strategy does not only imply the layout of the image but the emphasis given to the scale and detail of the dissected hand executed by Rembrandt [see Images 20 and 21].

Around the analysis of Rembrandt’s painting, a context rich in references emerges: the interest of Browne and the society of the time in the mysteries of the human body, something then deeply obscure; the simultaneous perspective of scientific illumination and the archaic dismemberment ritual; the ceremonial character of the body’s retaliation; and, lastly, Rembrandt’s use of the misrepresentation of the painted hand. This exercise of analyzing the work of art is of an impressive singularity and exposes Sebald’s vast knowledge on painting, especially with regards to the articulation with the theme of destruction through death:

And that hand is a particular case. Not only does it have a grotesque disproportion when compared to the hand closest to the observer, but

99 English doctor who had worked in Norwich in the seventeenth century and writer of profound admiration for Sebald. Browne’s writings will be covered in the later chapter, dedicated to literature. 100 “[...] it is more that likely that Browne did not miss the announcement of this dissection and that he witnessed the spectacular event, recorded by Rembrandt in his portrait of the surgeon guild […].” (SEBALD, 2010, page 21, own highlights and translation)

it also is totally deformed in anatomical terms […]. It is with him, the victim, and not with the guild that commissioned his work, that the painter identifies himself. Only he does not have the rigid Cartesian gaze, only he perceives it, the extinct and greenish body, only he sees the shadow in the half-opened mouth and over the eye of the dead.” (SEBALD, 2010, pages 22 and 26, own highlights and translation)

Image 20: The Anatomy Lesson seen from the narrative of The Rings of Saturn.

Image 21: Emphasis given to the misrepresentation of the hand. Sebald’s effort to bring the obscure detail of Rembrandt’s gesture to the fore shows a kind of compatibility between the two: just as the painter identifies with

the victim, Sebald also opts always for a peripheral position. It is from this choice that his point of analysis results, not only concerning the example in question but in the entire process of recovering memory as ash identified in the narrative. From the approach addressed to the work of art, the writer reveals, especially, his transgressive side.

Sebald’s focus of analysis is more precise around Rembrandt’s painting, but it also includes other significant examples. In the memory of a precious pilgrimage through the Netherlands, as previously mentioned – the same one in which the narrator travels with the almost exclusive intention of seeing The Anatomy Lesson101 –, there is a curious account of Ruisdael’s painting102 , also referred to in the previous chapter [see Image 22]. Sebald’s point here is to draw attention to the artificiality of the so-called birds-eye view – a panoramic view that dominates the pictorial representations seen in the book103 . In this case, there is a choice of an angle usually more totalizing by the artist’s exercise.

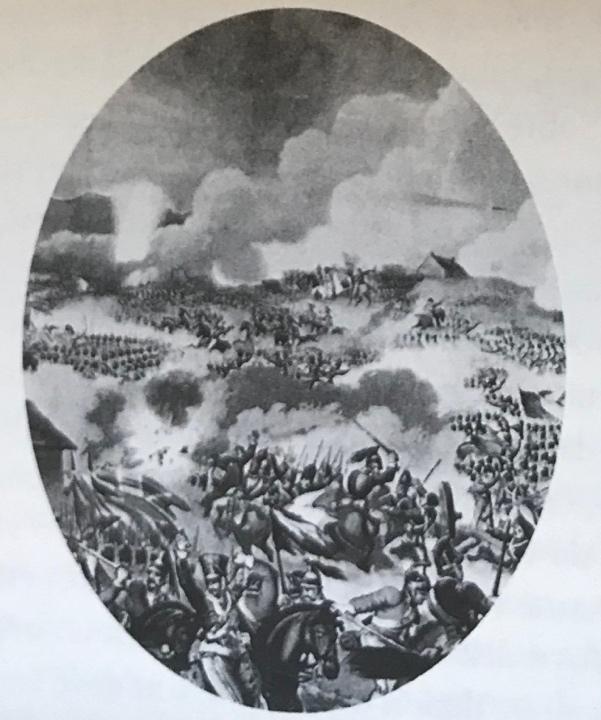

The same notion is applied in other examples of the narrative: case of the Battle of Sole Bay104 , seen by the narrator at the Greenwich Maritime Museum, and of the panorama of Waterloo [1912], seen together with the monument of the Battle of Waterloo, in Belgium [see Images 23 and 24]. Unlike Rembrandt – in which the grotesque error of the hand is associated with the choice of a more peripheral position by the painter -, the posture assumed in these composition is that of a

101 Again, the reference to the Anatomy Lesson, a painting which arouses the narrator’s continued interest: “[…] planted before the group portrait The Anatomy Lesson, with its almost four square meters. Although I went to The Hague especially to see this painting, which would occupy me a lot in the following years […].” (SEBALD, 2010, own highlights and translation, page 90) 102 “The plain that extends to Haarlem is seen from above, from the dunes, as is generally stated, but the impression of an aerial view is so strong that these dunes would have to be true hills, or even low mountains. The truth is that Ruisdael did not position himself on the dunes to paint, but at an imaginary and artificial point, some distance from the world.” (Ibid., page 90, own highlights) 103 According to the speech given by the researcher Judith Ryan at the conference Art, Fiction & History: The Work of W. G. Sebald 104 “[...] the pictorial representations of the great naval clashes are, without exception, pure fictions. Even celebrated naval painters such as Storck, Van der Velde or De Loutherbourg, of whom I have studied closely some versions of the Battle of Sole Bay at the Maritime Museum in Greenwich, are not able to give, despite the recognized realistic purpose, a true impression of how it should have been on board one of those ships […].” (SEBALD, 2010, page 84, own translation)

falsification of perspective105 , associated with the historical component, in which the point of view is sought to be more centralized and homogeneous. However, Sebald’s effort to exhibit what is obscure in the work of art remains – something that translates into the search for its residual, peripheral aspect. To a certain extent, it is also the case of the photographs made available by the narrator, the next point of analysis of the itinerary. In the hybrid reports of the writer, there is, therefore, space for art criticism, similar to the analysis of Rembrandt’s gesture and in agreement with the thought of Maria Filomena Molder:

“What does art criticism consist of? The analytical procedure is not to remove the wrap. The core is not dug up at the expense of anatomy. Depth is obtained by diving into the surface.” (MOLDER, 2016, own highlights and translation)

Image 22: View of Haarlem with quarar fields, Jacob van Ruisdael, 1670-1675. The image is not reproduced in the narrative, but it conditions a curious point of analysis of the narrator about the aerial view performed by the artist.

105 Like what can be seen at Waterloo: “(…) the gaze rises to the horizon, towards the huge circular mural, one hundred and ten meters by twelve, executed by the French marine painter Louis Dumontin in 1912 (…). It is then, one imagines when looking around, the art of representing history. It is based on a falsification of perspective. We, the survivors, see everything from top to bottom, we see everything at once an we still don’t know how it went.” (SEBALD, 2010, own highlights and translation, page 129)

Image 23: Battle of Sole Bay, Willem Van der Velde, 1672. The narrator situates the pictorial representation of the great naval clashes as pure fiction.

Image 24: Small scale snapshot of the Battle of Waterloo panorama, possibly Sebald’s own strategy to make the image more intricate.