12 minute read

1.2 The Rings of Saturn Movements as mobilized territories

and the remembrance share the architectural experience and involve the dynamics of space, movement, and narrative19 .

It is possible to justify, in this way, the choice of the narrator as a pilgrim. By making spatial practice viable, Sebald simultaneously enables the emergence of memory. In this double process, it is the itinerary that constructs the meaning and that, in turn, shapes a kind of mapping. In the map established by Sebald, it is essentially the movement that mobilizes the narrator’s crossing points, as will be seen below.

Advertisement

1.2 The Rings of Saturn:

Movements as mobilized territories20

According to the initial presentation conducted around the theme of pilgrimage, the question of the traveler reaches its most potent representation in the work The Rings of Saturn. With the starting point of the book inscribed from the pilgrim’s movement, the itinerary that unfolds here incorporates the mapping recorded by the narrator’s journey. In this sense, it is the formalization of the act of walking that guarantees access to the ash.

In addition to what was outlined previously, there is also a personal configuration in the interest shown by Sebald about the pilgrimage. The access to the vast set of references evoked in his books usually takes place from the perspective of the walk, as we have already mentioned. For the writer, the traveler’s approach –essentially, with regards to the observation of nature – develops a more accurate look, even close to what can be seen in the observation exercise of some

19 “This is how architectural experiences – which involve the dynamics of space, movement and narrative […].” (BRUNO, 2018, page 57, own highlights) 20 Em articulação com o argumento de Giuliana Bruno, professora e investigadora da Universidade de Harvard: “Architectural frames, like filmic frames, are transformed by an open relation of movement to events. Rather than being vectors or directional arrows, these movements are mobilized territories, mappings of practiced places.” (Ibid., page 57)

scientists21 .In this sense, Sebald’s explanation converges with the narrative strategy itself and reveals an affinity for the narrator’s context.

Following the period of immobility in the hospital, previously introduced, the narrator marks another time record, now the definitive point of writing the book22 . It is at this moment that the memory of the figure of Michael Parkinson occurs, a professor who soon presents himself as a structuring character in the context of the narrative. Parkinson is the point of connection between the period when the narrator was in the hospital – and the professor was still alive – and the later period, outlined above. It is due to the discovery of Parkinson’s death that the narrator faces a kind of coming to his senses23, which triggers the reflection that led to death and destruction.

Michael Parkinson is presented as an unusual figure, distinguished by an acute sense of accomplishment of his duties and by a modesty of needs – something that borders on a certain quirkiness24 . Parkinson’s life experience converges with the narrator’s interests: there is a personal approach between them, and the common importance given to the pilgrimage. When mentioning that Parkinson, during the summer holidays, made long trips on foot linked to studies on Ramuz25 ,

21 “The walker’s approach to view nature is a phenomenological one and the scientist’s approach is a much more incisive one, but they all belong together. And in my view, even today it is true that scientists very frequently write better than novelists. So I tend to read scientists by preference almost, and I’ve always found them a great source of inspiration.” (SEBALD, 2007a, page 81) 22 “Now that I start to clean up my notes, more than a year after being discharged from the hospital, it is inevitable to occur to me the thought that, at the time, Michael Parkinson was still alive in his little house on Potersfield Road […].” (Id., 2010, page 15, own translation) 23 “[...] It is a way of making the ‘come to yourself’ come on the scene, which is accomplished by getting used to the image of death. In Greek getting used is meletáw, which also means taking care of; occupy, do, exercise (in the arc, for example). Taking care of this one, who also understands how to fight against forgetfulness, which means that knowledge can abandon us at all times.” (MOLDER, 2017, page 17, own translation) 24 “[…] Michael was in his fifties, he was a bachelor and, I imagine, one of the most innocent people I have ever met. Nothing was as alien to him as selfishness, nothing worried him more than the fulfillment of his duties (…). Most of all, however, he was distinguished by the modesty of his needs, which many claimed to be bordering on eccentricity. At a time when most people have to continually buy to make a living, Michael hardly ever went out to shop.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 16, own translation) 25 Swiss writer who also used the theme of catastrophe.

the narrator again introduces the reference to pilgrimage, essentially as an individual activity linked to a certain sense of search26 .

The news of Michael Parkinson’s unexpected and unexplained death opens the constellation of grief27 characteristic of Sebald’s procedure. In addition to destruction through death, other indications prove to be important reading keys. Regarding space, it is worth mentioning the practice of walking linked to thought – and, more properly, to the literary activity. In relation to the narrative unit, another relevant development is due to the convergence of Parkinson’s biographical information with the author’s life28 . The strategy is repeated in all of Sebald’s books: while the details included by the narrator seem to reveal an autobiographical tone, the reader never gets to the confirmation of this possibility.

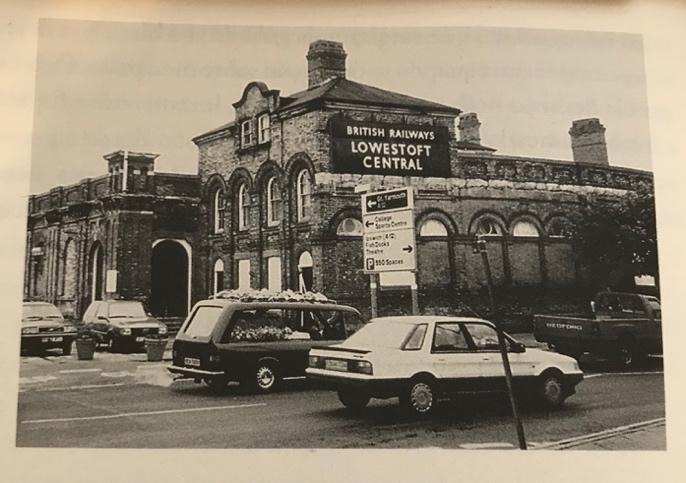

When returning to the narrator’s movement, it is essential to introduce the remembrance of the context of the pilgrimage itself, initiated in the second chapter29 . It is from there that a detailed description of the locomotive’s journey down the east coast of England is recorded. The reference to the train – and also to the train stations – is a constant theme in Sebald’s writing: through it, the author reinforces the notion of crossing and incorporates a powerful symbol. In this perspective, the representation of the railroad ensures not only the displacement of the pilgrim but also introduces a symbolic element that reverberates throughout the text.

In extensive contact with Sebald’s procedure, it is possible to perceive that the repeated reference to the train is a resource that is related, to a greater or lesser

26 “In general, when he returned from one of those trips, or when I admired the seriousness with which he always did his job, it seemed to me that in his own way he had found happiness, in a form of modesty that is barely conceived today.” (SEBALD, 2010, page 16, own translation) 27 “As he searches for patterns in the constellation of grief that his books record […].” (FRANKLIN, 2007, page 126) 28 “Though the narrator identifies both [Michael Parkinson e Janine Dakyns] characters as professor, and people whose names and biographical data match theirs were in fact his colleagues […].” (Id., 2006, page 129) 29 The diesel locomotive – Morton Peto’s palace – Visit to Somerleyton – German cities on fire –Lowestoft’s decline – Kannitverstan – The old spa – Frederick Farrar and the court of Jaime II

degree, to the logic of deportation30 . Marked by the circumstances of World War II – even though he did not directly experience the horrors of the period31 –, the author draws a good part of his intention from the juncture of destruction left by the years of conflict. Given this, exile and displacement are notion close to Sebald and play in the narratives a tool for access to what is formalized as a loss –something that takes form of a vestige.

It is following this idea that the author establishes a kind of mapping writing. As the locomotive advances, the narrator is faced with monotonous and degraded landscapes – which pay attention, essentially, to transience and destruction32 . Along the way, the idea of ash linked to displacement emerges with increasing force. It is in this light that the pilgrim arrives at the Somerleyton mansion, a property that once belonged to the British landed nobility and whose relevance dates back to the Middle Ages. At Somerleyton, the narrator experiences, more properly, the cracks produced by time33 , from the contact with architecture on the verge of dissolution and ruin34 . On the contrary, the report presented also ensures the possibility of the building as retaining fragments of memory35 . It is in this direction that Sebald’s writing moves36 .

The interest in architecture, in the process of destruction, is part of the author’s set of references and can also be observed, in a more evocative way, in

30 “I think that is was a question of trying to find, in a text of this kind, ways of expressing heightened sensations, as it were, in the form of symbols which are perhaps not obvious. But certainly the railway business, for instance. The railway played a very, very prominent part, as one knows, in the whole process of deportation.” (SEBALD, 2007b, and 53, own highlights) 31 Sebald himself, born in 1944, decided to emigrate due to the post-war context. First, he continued his university studies in Manchester, then settled in Norwich, where he taught for over thirty years at the University of East Anglia. 32 “[...] there is nothing to see here but bush and undulating reeds, some dilapidated willows and ruined brick cones, which look like monuments of an extinct civilization, remnants of countless windmills and aeolian bombs […]. When these reflexes paled, in a way the whole region paled with them. Sometimes I imagine, when I observe, that everything is already dead.” (SEBALD, page 40, own translation) 33 “Just a fraction of a second, I usually think, and an entire era passes.” (Ibid., page 41) 34 “And how beautiful the mansion looked to me, now that it was imperceptibly approaching the brink of dissolution and ruin.” (Ibid., page 46, own translation) 35 “Nor can we say at a glance what decade or century we are in, as many ages are overlapping there and coexist.” (Ibid., pages 45 and 46, own translation) 36 Sebald’s literary project points, in a broad sense, to the need for a kind of memorial, as will be highlighted in the third chapter.

Austerlitz’s narrative – especially under the bias of architecture as a testimony. In telling the story of Jacques Austerlitz, whose identity linked to the horrors of war unfolds from the perspective of space37 , Sebald reinforces the articulation between the experience of the place and memory38 . At this point, it is important to bring the reference to architecture as a powerful reflection of reminiscence39: it is through the experience of space that memory opens up.

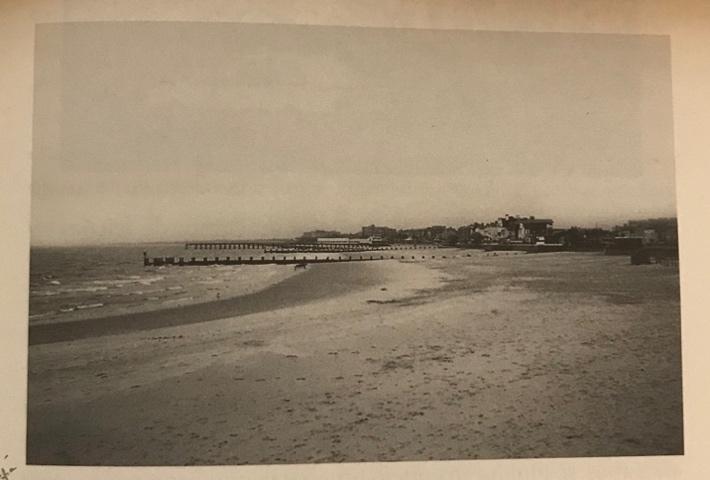

With that in mind, it is possible to return to the pilgrim’s journey in The Rings of Saturn. After Somerleyton’s passing, what happens continuously in Sebald’s procedure is a kind of opening of the triggers of remembrance. First, it inserts a quick mention of the German cities destroyed due to aerial bombing40 – a topic dear to the author – to, soon after, develop the process of resonance of memory through space. When the narrator arrives at Lowestoft, he observes the city’s astonishing decline and launches a series of symbolic references that focus on decay and destruction [see Images 2, 3 and 4].

From that point on, the author’s approach intensifies around the use of indirect references to arrive at the exact measure of horror41 . In the photographs that demonstrate a privileged sense of space, the pilgrim evokes the presence of the dead and the vanished places42 – and, with this, formalizes what is residual. Even

37 The book discusses the life trajectory of Jacques Austerlitz, son of Jews who escaped war as a child due to the well-known Kindertransporte. Adopted by an English Calvinist couple, Austerlitz only really has access to his past when he begins to make a pilgrimage through Prague, his family’s home town. 38 “[…] the idea, ridiculous in itself, that crossed my mind, that that iron pillar to which the scaled surface gave life, could remember me and in a way, said Austerlitz, be a testimony of what I didn’t remember myself.” (SEBALD, 2012a, page 202, own highlights and translation) 39 “[...] I only remember, said Austerlitz, that I went out to the platform to photograph the capital of an iron pillar that awakened in me a reflex of reminiscence.” (Ibid., page 202, own highlights and translation) 40 “When he found out where I was from, [William Hazel, Somerleyon’s gardener] he started telling me that, during his final years of school […], one thing that never left his head was the air war that was going on against Germany form the sixty-seven air bases established in East Anglia after 1940.” (Id., 2010, pages 47 and 48) 41 “And this is why the main scenes of horror are never directly addressed. […]. So the only way in which one can approach these things, in my view, is obliquely, tangentially, by reference rather than by direct confrontation.” (Id., 2007a, page 80, own highlights) 42 “[…] he photographs landscapes, streets, monuments, ticket stubs. Sebald’s books are famously strewn with evocative, gloomy black-and-white photographs that call up the presence of the dead, of vanished places, and also serve as proofs of his passage.” (SCHWARTZ, 2007, page 14)

in the decline an upward movement is noticeable: the focus on displacement, as a possibility of access to the ash, mobilizes the territories crossed by the narrator. From then on, the mapping of practiced places43 is established as an essential trigger for recollection.

Image 2: The narrator’s arrival in Lowestoft – seaside town once marked by growth.

Image 3: At the farewell to Lowestoft, the meeting with the black hearse covered with wreaths. The scene allows the narrator to introduce an account of the funeral procession of an Amsterdam merchant. Image 4: From the hotel’s balcony, the narrator sees the famous Lowestoft pier – a record of the city’s golden times and, therefore, of its transience.

43 Still in articulation with Giuliana Bruno’s argument previously mentioned.