4 minute read

2. Image 2.1 The itinerary of the image in The Rings of Saturn

2. IMAGE

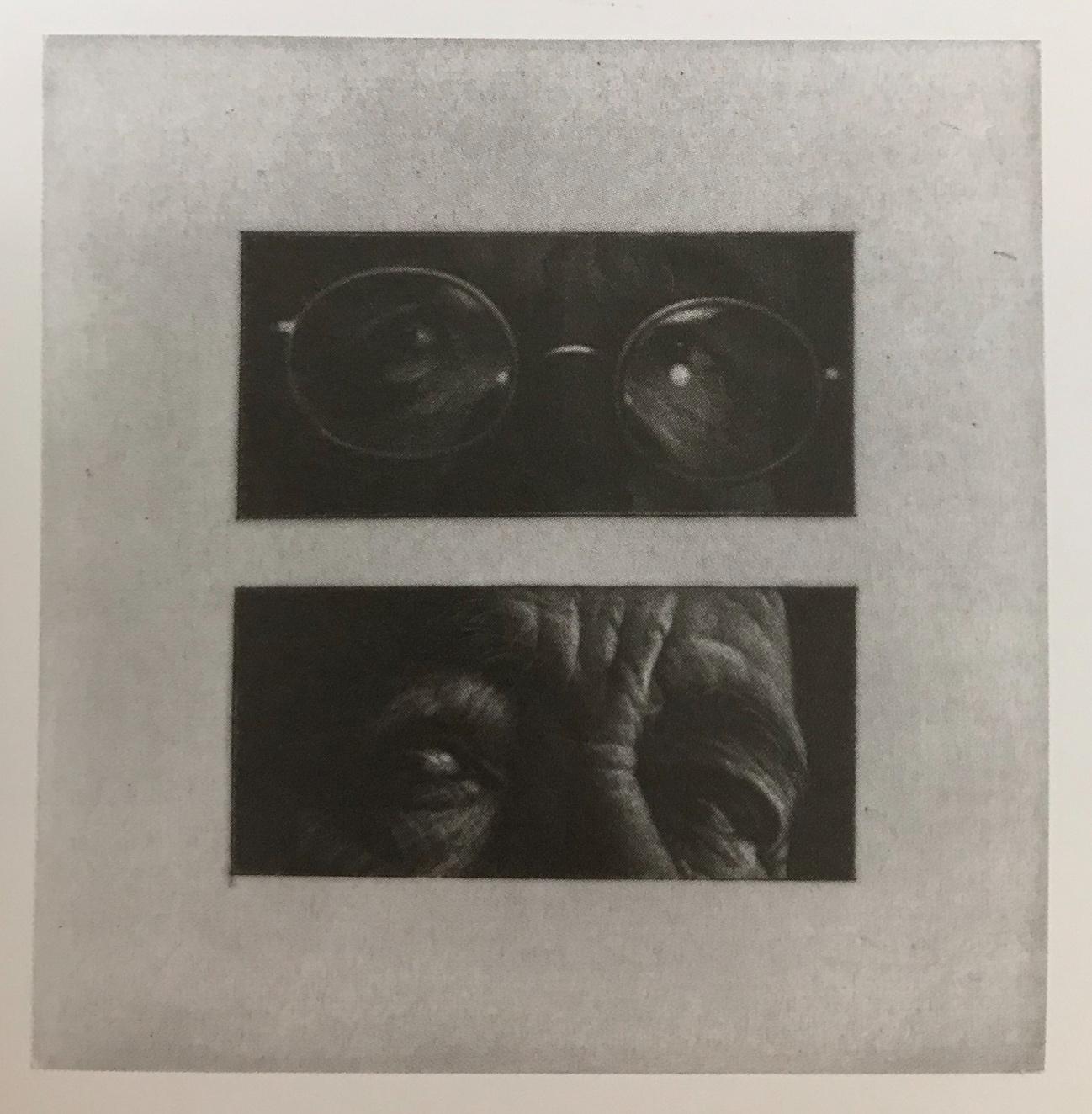

Image 17: Lithography of W. G. Sebald by Jan Peter Tripp.

Advertisement

At the end only so many will remain as can sit round a drum81

81 Poem by W. G. Sebald that accompanies Jan Peter Tripp’s lithography in Unrecounted [2004], translated by Michael Hamburger. The book features a set of thirty-three poems by the author for the selected lithographs by Jan Peter Tripp, Sebald’s longtime friend. In the work, the focus of the lithographs is on the eyes of writers and artists, like Borges and Rembrandt, references of Sebald’s work.

The question posed earlier, about Sebald’s own photographs, proposes an immediate link with the writer’s mediations on the image. There is in the work After Nature82 [1988], Sebald’s first literary publication, a relevant clue: the focus on the figure of the German painter Matthias Grünewald [1470-1528], to whom Sebald devotes particular interest in the explicit relationship that the artist establishes with his own representation in the work of art83 . About Grünewald, the author writes:

[...]. The face of the unknown Grünewald is always appearing in his work, that of the witness in the desert, that of the pious in the Christ Mocked of Munich. […] Always the same Mildness, the same burden of melancholy, the same irregularity of the eyes, veiled, deviated, sunk in solitude. (SEBALD, 2012b, page 11, own highlights and translation)

In the presentation of the figure of Grünewald, it is possible to recognize a kind of self-portrait of Sebald himself84 . As in Jan Peter Tripp’s lithography highlighted above, the writer’s face continually emerges in his work – curiously dissimulated85 . The reference to Grünewald’s veiled gaze is also a characteristic assumed by the writer’s procedure86 , as the work of recalling his narratives takes place, as already mentioned, by the attempt to access what is hidden – again, under the notion of ash.

82 The book is divided into three parts, each dedicated to a specific thematic interest from different historical periods: the first covers the Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald; the second, the 18th -century naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller; the third, in turn, contains elements of Sebald’s own life, which immediately registers an autobiographical dimension of the work. (MÜCKE, 2011) 83 This is the case of the Lindenhardt Altar, in which the face of St. George is, in fact, the face of Grünewald. (KÖHLER, 2004) 84 “One does not need to see the last photographs of W. G. Sebald (…) to recognize a sort of selfportrait in that description; and there is hardly a motif as central to his work as eyes.” (Ibid., page 97) 85 “These are cases of similarity/curiously dissimulated, wrote Fraenger,/ whose books the fascists burned. / Yes, it seems that in the work of art/ men respect each other as brothers,/ build monuments to each other/where their paths cross.” (SEBALD, 2012b, page 12, own translation) 86 “It is with Grünewald’s veiled gaze that the ‘elemental poem’ After Nature […] begins. But the dimming of vision and the penetration of darkness are the key metaphors in all his books for his most intimate concern: the work of remembrance, the work of witness, in the torrential flux of time.” (KÖHLER, 2004,97)

The focus on the issue of gaze is central to Sebald’s procedure and reaches an even more potent force in the last books – Austerlitz and the posthumous Unrecounted. In Austerlitz, the author mentions exactly the exercise of the gaze that manages to penetrate the darkness, specific to certain painters and philosophers87 . It is with this notion that Sebald seeks to build his memorial of images, always guided by the choice of a peripheral vision88 . In this sense, attention is not given to what is evident in the image, but rather to its obscure detail.

87 “[...] and that stare, inquiring that is found in certain painters and philosophers who, using only pure observation and pure thought, seek to penetrate the darkness that surrounds us.” (SEBALD, 2012a, pages 10 and 11, own translation) 88 In articulation with Andrea Köhler’s careful observation in the text Penetrating the Darkness, which is part of the English edition of Unrecounted: “In his last novel, Austerlitz, the narrator tells of a sudden loss of vision in the right eye. It seemed to him then ‘as though at the edge of my field of vision I could see with undiminished clarity, as though I need only to direct my attention to the periphery to put an end to what at first I judged to be a hysterical weakening of my sight.’ This suggests that here the physical change responds to a psychic one, as though the eye had chosen to focus on the peripheral, on those things which the author was so intent on conserving, collecting and archiving.” (KÖHLER, 2004, page 98, own highlights)