Learn more at high5health.com PROMOTING EXCELLENCE IN ENDODONTICS Communicating periodontal issues across dental implant platforms Drs. Stuart Segelnick and Mea A. Weinberg Dental infections, part 2 — prophylaxis: help avoid antimicrobial resistance Wiyanna K. Bruck, PharmD, and Jessica Price

Dr. Jason Putnam: owning his future Winter 2022 Vol 15 No 4 endopracticeus.com Implant & Endo Connection n 4 CE Credits Available in This Issue* Judy McIntyre, DMD, MS

You’re passionate about teeth. We’re passionate about payroll, recruiting, and human resources. HighFive is your expert team at wrangling all those business necessities before they consume your practice.

Practice spotlight

Winter 2022 n Volume 15 Number 4

Editorial Advisors

Dennis G. Brave, DDS

David C. Brown, BDS, MDS, MSD

L. Stephen Buchanan, DDS, FICD, FACD

Gary B. Carr, DDS

Arnaldo Castellucci, MD, DDS

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD

Stephen Cohen, MS, DDS, FACD, FICD

Samuel O. Dorn, DDS

Josef Dovgan, DDS, MS

Luiz R. Fava, DDS

Robert Fleisher, DMD

Marcela Fridland, DDS

Gerald N. Glickman, DDS, MS

Jeffrey W Hutter, DMD, MEd

Syngcuk Kim, DDS, PhD

Kenneth A. Koch, DMD

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS, MAGD, FPFA, FACD, DICOI

Joshua Moshonov, DMD

Richard Mounce, DDS

Yosef Nahmias, DDS, MS

David L. Pitts, DDS, MDSD

Louis E. Rossman, DMD

Stephen F. Schwartz, DDS, MS

Ken Serota, DDS, MMSc

E Steve Senia, DDS, MS, BS

Michael Tagger, DMD, MS

Martin Trope, BDS, DMD

Peter Velvart, DMD

Rick Walton, DMD, MS

John West, DDS, MSD

CE Quality Assurance Board

Bradford N. Edgren, DDS, MS, FACD

Fred Stewart Feld, DMD

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS, MAGD, FPFA, FACD, FADI, DICOI, DADIA

Justin D. Moody, DDS, DABOI, DICOI

Lisa Moler (Publisher)

Mali Schantz-Feld, MA, CDE (Managing Editor)

Lou Shuman, DMD, CAGS

© MedMark, LLC 2022. All rights reserved. The publisher’s written consent must be obtained before any part of this publication may be reproduced in any form whatsoever, including photocopies and information retrieval systems. While every care has been taken in the preparation of this magazine, the publisher cannot be held responsible for the accuracy of the information printed herein, or in any consequence arising from it. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the opinion of either Endodontic Practice US or the publisher.

number 2372-6245

INTRODUCTION

Asking for insights leads to good decisions

As endodontists, keeping up with the latest advancements in technology is simply part of the job. As we endeavor to provide our patients with the best possible care, it’s our responsibility to ensure we’re up-to-date on the best possible tools and technologies to help us provide that care. It’s what our patients deserve and what our profession promises. But amidst our long hours and packed waiting rooms, how can we use our limited capacity to separate the gimmicks from the legitimately important advancements in our profession? In a world of finite resources, how do we ensure we’re investing our time, effort, and money on things that will actually improve our patients’ lives as well as our own?

I remember when I finally decided to take the leap and invest in cone beam computed tomography. It wasn’t an easy decision. Navigating how to incorporate this new technology, as well as the financial investment of the CBCT equipment and the financial impact on patients, was a challenge. And then there’s simply the resistance to change. So many aspects of endodontics are tried and true. We all become proficient in a certain way of doing things and become hesitant to anything new that deviates from that trusted path. But next to the microscope, the use of CBCT imaging has become the most important development in endodontics. It has increased our ability to diagnose and treat pathology efficiently and correctly. The switch wasn’t easy, but the long-term positive impact for my patients and my practice has been worth the effort.

But how did I come to that decision? Of course, I stayed current on the latest literature and attended continuing education courses. But more than anything, I relied on what I consider to be the most important tool in any endodontist’s arsenal — my colleagues.

No advancement, no new piece of technology, no exciting new technique will ever be more valuable than the minds, experience, insight, and fellowship of our fellow endodontists. Being a partner with HighFive Healthcare, I have access to a network of brilliant, hardworking, and generous people who all bring their own unique perspectives, knowledge, and history to the table and whose advice and guidance I can rely on when faced with challenging decisions. I didn’t just read articles about the CBCT; I asked my colleagues. I got their first-hand experiences. I learned the ups and the downs, the pros and the cons. I had people I trusted to help me make that important decision and help make it the right one.

Technology is always changing. There’s always some new thing on the horizon that claims to change the way we practice for the better. And some of them actually will. But nothing will ever be more important than the relationships we build with each other. And anything that allows us, as endodontists, to increase those connections, to improve our communications, to bring us closer together in order to share our expertise with one another, that is the most important innovation possible.

Kristy Goff Jones, DMD, graduated Millsaps College in 2003 with a BS in Biology and then attended the University of Mississippi School of Dentistry. After receiving her DMD in 2007, she started the postgraduate program in endodontics at Tufts University School of Dental Medicine in Boston, Massachusetts. In 2009, she began practicing with Endodontic Associates where she currently works alongside Dr. Jeffery Pride in three locations in Ridgeland, Brandon, and Vicksburg, Mississippi. You can reach out to Dr. Jones at https://endoofms.com/.

1 endopracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4

ISSN

Kristy Goff Jones, DMD

2 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS TECHNIQUE Negative and positive pressure irrigation: all-in-one! Dr. Allen Ali Nasseh explores whether the positive and negative pressure needs of clinicians can be met with a simple and inexpensive device

PERSPECTIVE Telling the world about you

Founder/CEO, MedMark Media............................... 6 CLINICAL Internal root resorption: morphological aspects and clinical management

Fernando Goldberg, Denise Alfie, Juan Pablo Miraglia, Carlos Cantarini,

Gonzalo

discuss treatment for

inflammatory condition ..............18 TECHNIQUE Rotary negotiation as first file to length Drs. L. Stephen Buchanan and Christophe L.M. Verbanck discuss a modern answer to

age-old issue .............................. 24 SERVICE PROFILE US Endo Partners Building culture delivers financial returns .............................................. 28 CONTINUING EDUCATION Communicating periodontal issues across dental implant platforms Drs. Stuart Segelnick and Mea A. Weinberg review typical challenges and management at the dental implant-abutment connection ...................................... 30 8 12

STORY

McIntyre, DMD, MS

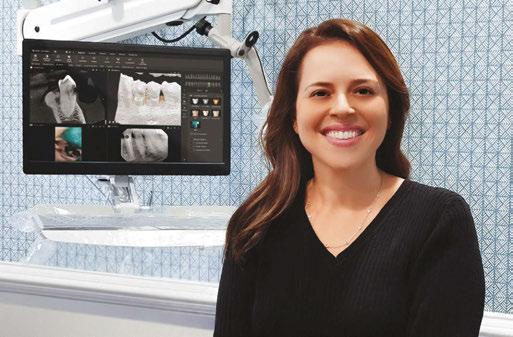

image of Dr. McIntyre courtesy of DEXIS.

PUBLISHER’S

Lisa Moler,

Drs.

and

Garcia

an

an

COVER

Judy

Cover

2023 YOUR MAKE

your practice growing strongly and more profitable than ever. Enjoy productive stress-free scheduling driven by incredible teamwork and efficiency. Improve referrals and patient flow with powerful strategies for engaging GP relationships.

one year, the Endo Mastery team can help you transform your practice and transform your life. Pay off debt fast, eradicate financial stress, empower personal and family goals, and love your practice like never before. Learn more about Endo Mastery’s coaching programs and why our clients love us. BEST YEAR! 1-800-482-7563 info@endomastery.com

Imagine

In

CONTINUING EDUCATION

Dental infections, part 2 — prophylaxis: help avoid antimicrobial resistance

Wiyanna K. Bruck, PharmD, and Jessica Price continue their discussion of concepts surrounding antibiotic prophylaxis in dentistry ............. 35

TECHNOLOGY

Healing and longterm results with the GentleWave® Procedure

Dr. Scott K. Hetz illustrates minimally invasive endodontic treatment with predictable results 40

PRODUCT PROFILE

Sealing the deal with a bioceramic root canal sealer

CeraSeal from Meta Biomed provides antimicrobial properties, high biocompatibility, and a hermetic seal 44

PRODUCT SPOTLIGHT

Optimizing surgical visualization with the ZEISS EXTARO® 300

Dr. Jon Irelan discusses innovations in endodontic microsurgery 46

LEGAL MATTERS

Implications of the False Claims Act

Kerry Cahill, Esq., discusses how practitioners need to protect themselves even in altruistic circumstances

PRACTICE MANAGEMENT

Life sentence practice or lifestyle practice?

Dr. Albert (Ace) Goerig describes the foundation to his philosophy and vision...................................... 54

SMALL TALK

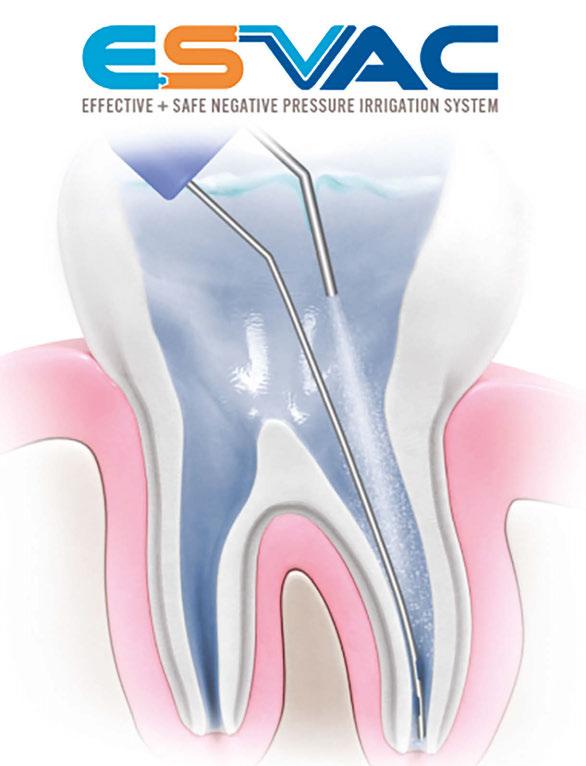

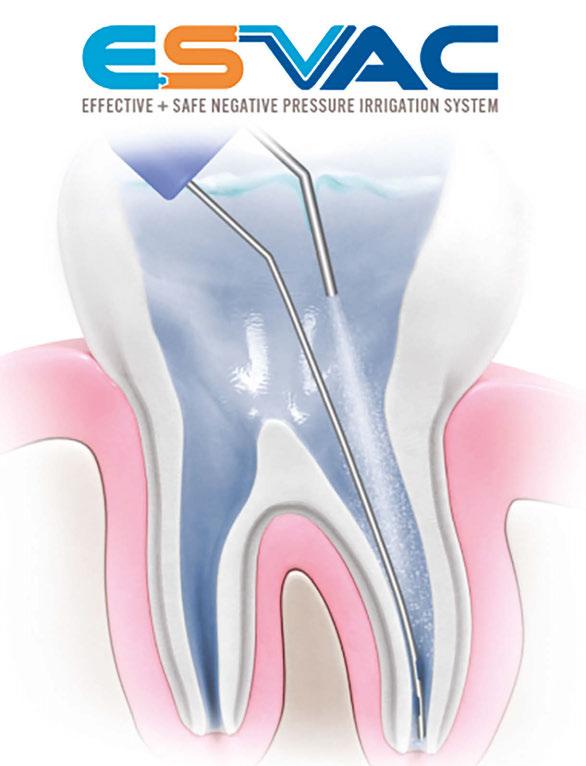

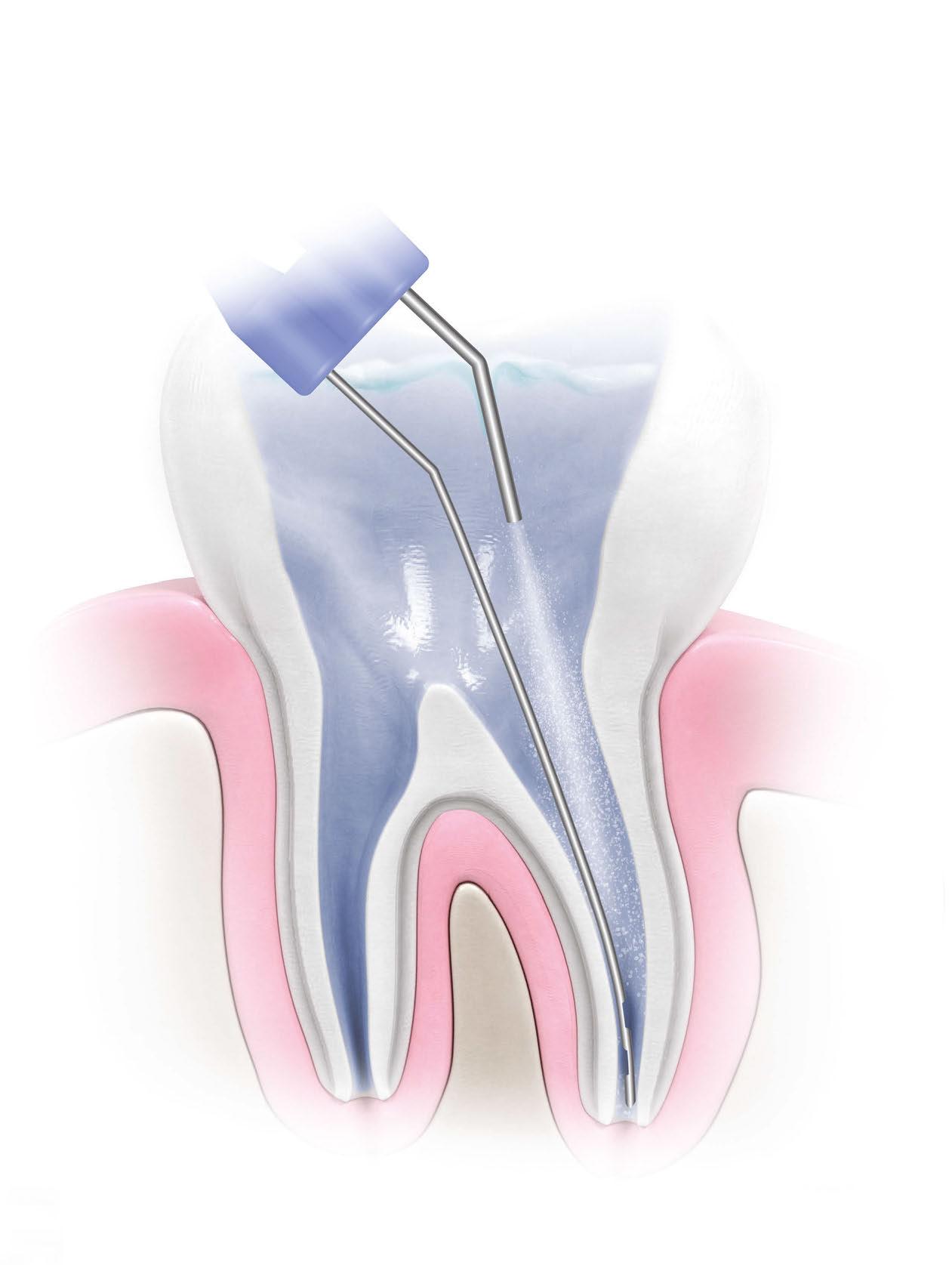

PRODUCT PROFILE ES Vac ES Vac is changing irrigation! ... 48

LEGAL MATTERS Navigating dental malpractice lawsuits

Kristin Tauras, JD, guides dental specialists through the legal elements

50

Thoughts on why we lose staff

Drs. Joel C. Small and Edwin McDonald discuss the rewards of appreciating your team 55

PRACTICE PROFILE Dr. Jason Putnam: owning his future

4 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS

......................................

............................ 52

.........................................................

Connect. Be Seen. Grow. Succeed. | www.medmarkmedia.com READ the latest industry news and business WATCH DocTalk Dental video interviews with KOLs LEARN through live and archived webinars RECEIVE news and event updates in your inbox by registering for our eNewsletter CONNECT with us on social media www.endopracticeus.com *Paid subscribers can earn 4 continuing education credits per issue by passing the 2 CE article quizzes online at https://endopracticeus.com/category/continuing-education/

56

You handle the teeth.

At HighFive Healthcare, we’re passionate about the business of endodontics. That’s why we partner with Endodontists who are equally passionate about helping their patients. Our family of experts handle just about everything outside of root canals, so you can focus on what you love and create your own tomorrow.

Learn more at high5health.com

Telling the world about you

Published by

Our worlds are so busy with our time consumed with improving clinically, professionally, and personally. We work hard and hopefully find the time to play hard. From my view as a publisher of four and soonto-be five dental publications, I see and hear about so much innovation going on in the dental community. Dentists are showing patients that dental health means better overall health, and there are so many ways to add technology, expand clinical options, and create your own new protocols and inventions that can change the face of your specialties. My team at MedMark is always searching for your stories — for your journeys, your successes, and even your speed bumps along the way. Entrepreneur Gary Vaynerchuk said, “Regardless of what you are trying to accomplish, you’ve got to tell the world about it.” I wholeheartedly agree. And that’s what we at MedMark Media have been doing over the past 17 years. We’ve been telling the world about you.

Publisher

Lisa Moler lmoler@medmarkmedia.com

Managing Editor

Mali Schantz-Feld, MA, CDE mali@medmarkmedia.com Tel: (727) 515-5118

Moler Founder/Publisher, MedMark Media

All of the new advancements in dental specialty fields are amazing — artificial intelligence (AI), virtual reality, 3D printing, robotics, the field of dental sleep medicine, braces and aligners that move teeth faster and more efficiently, and imaging in 2D and 3D that makes diagnostics more precise. Advances in endodontic materials such as bioceramics contribute significantly to that specialty’s incredible growth. Let’s not forget implants — according to iData Research, over 3 million dental implants are placed each year in the United States, and the U.S. market is expected to exceed $1.5 billion in 2027.

Here’s more good news! Our Cover Story is a conversation with Dr. Judy McIntyre, who talks about how DEXIS™ CBCT imaging helps her to confidently offer a realistic prognosis and gives her essential information for treatment planning. Our CE article by Drs. Stuart Segelnick and Mea Weinberg, titled “Communicating periodontal issues across dental implant platforms,” explores common problems and management at the dental implant-abutment connection. For our Technique column, Dr. Allen Ali Nasseh tells how the TotalVac Irrigation System allows for both positive and negative pressure application of the multiple liquids necessary for the root canal process. Drs. L. Stephen Buchanan and Christophe L.M. Verbanck discuss rotary negotiation as the first files to length and the progress that has been made by different files over the years.

Back to you — how can we help you tell the world about your innovations, techniques, and life-changing treatments? Our articles and advertisers show you what is possible and practice changing, and promises to help differentiate you from the rest. To change Gary Vaynerchuk’s quote just a bit: Regardless of what you are trying to accomplish, MedMark is here to help you tell the world about it.

To your best success,

Assistant Editor Elizabeth Romanek betty@medmarkmedia.com

National Account Manager Adrienne Good agood@medmarkmedia.com Tel: (623) 340-4373

Sales Assistant & Client Services Melissa Minnick melissa@medmarkmedia.com

Creative Director/Production Manager Amanda Culver amanda@medmarkmedia.com

Marketing & Digital Strategy Amzi Koury amzi@medmarkmedia.com

eMedia Coordinator Michelle Britzius emedia@medmarkmedia.com

Social Media Manager April Gutierrez socialmedia@medmarkmedia.com

Digital Marketing Assistant Hana Kahn support@medmarkmedia.com

Website Support Eileen Kane webmaster@medmarkmedia.com

MedMark, LLC 15720 N. Greenway-Hayden Loop #9 Scottsdale, AZ 85260

Lisa

Moler Founder/Publisher MedMark Media

Tel: (480) 621-8955 Toll-free: (866) 579-9496 www.medmarkmedia.com

www.endopracticeus.com

Subscription Rate

1 year (4 issues) $149 https://endopracticeus.com/subscribe/

6 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 PUBLISHER’S PERSPECTIVE

Lisa

two

help patients

You proactively recommend the CareCredit credit card to patients. Have patients scan your custom link QR code where they can privately see if they prequalify, apply and pay with CareCredit. #1: #2: It’s financing simplified. Get everything you need with the Contactless Financing Kit — Scan this QR code, or visit carecredit.com/contactless-kit. MM2SQ4DA Data fees may apply. Not yet enrolled with CareCredit? Call 800.300.3046 (option 5).

It takes

steps to

get care

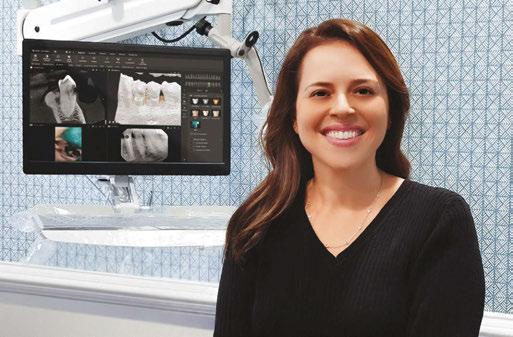

Judy McIntyre, DMD, MS

Why did you become an endodontist?

I always knew I wanted to be a dentist. As a child, I had a traumatic dental injury, and I had positive experiences with my dentist; I wanted to be able to provide the same kind of care to others. I’ve always enjoyed working with my hands, and endodontics suited my skill set and personality.

During my residency at the Adams School of Dentistry (UNC-Chapel Hill), I was fortunate to have great mentors and was exposed to many dental trauma cases. In my practice, Hopkinton Endodontics, I treat pediatric and adult patients with dental trauma as well as my traditional endodontic patients, so I can combine both passions. It’s the perfect fit.

What is the most rewarding aspect of your practice?

I find it incredibly rewarding to save teeth and relieve patients’ pain. Being able to put patients at ease and give them their smiles and confidence back is very gratifying. Our pediatric patients are surprisingly good; typically they have fewer past dental experiences, and with the right approach, they turn out to be very cooperative with local anesthesia alone! The parents are so appreciative, especially when they’ve previously been told that nothing can be done for their children/tooth. My young patients with dental trauma have a lot on the line — trying to save a tooth in a growing patient. Treating kids is extremely rewarding.

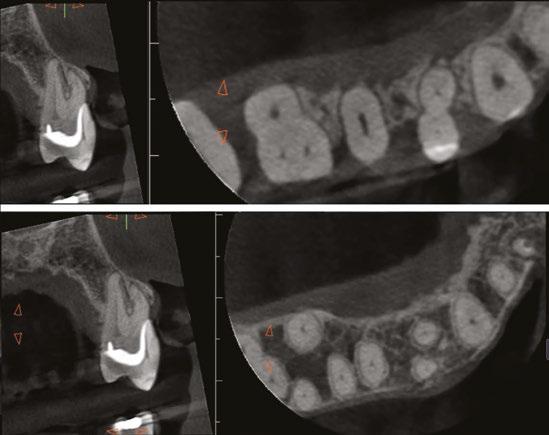

I also find current technology such as CBCT imaging helps to identify the cause of patients’ pain and to treat issues that have been missed or misdiagnosed. Often, patients have seen other practitioners and have been told that everything appears normal. It makes my day when I’m able to reveal the cause of their pain and problems, to show them on their 3D scan that they were correct in thinking something was not quite right, and then correct and treat the issue. The patients are extremely grateful and relieved. My CBCT unit plays a key role in that.

As endodontists, our priority is to save teeth whenever possible. Sometimes we forget that; we’re doing more than just a root canal procedure — we’re preventing or treating apical periodontitis — we are saving teeth! CBCT enables me to save more teeth and do it more predictably; patients appreciate when they can avoid losing the tooth.

When did you start using CBCT in your practice?

I was first introduced to cone beam technology during my endodontics residency. UNC had a CBCT unit and was one of only a few institutions in the country that did almost 20 years ago. At the time, the technology was new, and we didn’t use it often. Reflecting back, I wish we had used it

8 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 COVER STORY

Judy McIntyre, DMD, MS

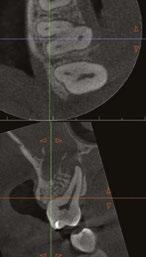

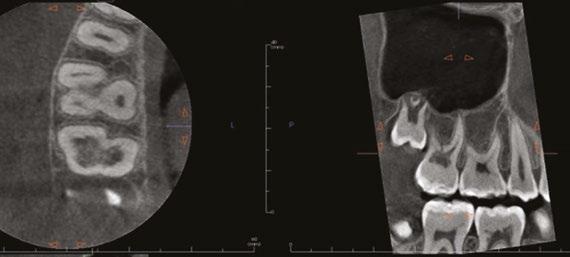

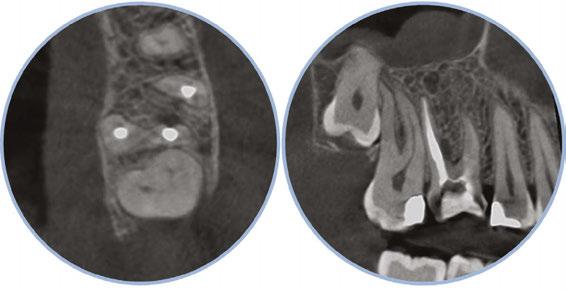

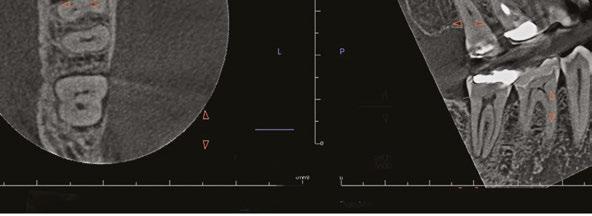

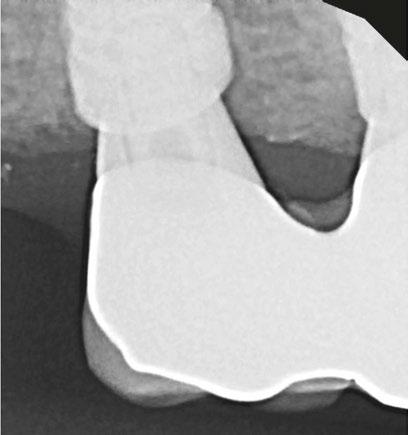

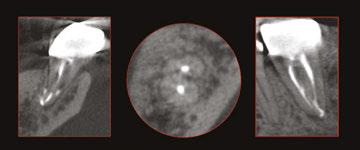

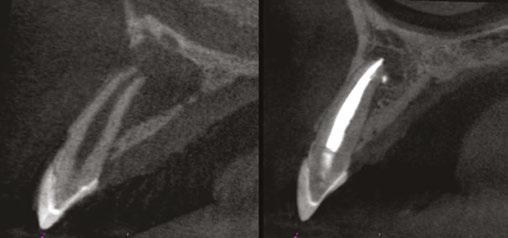

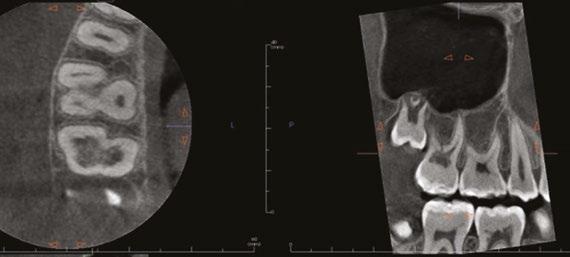

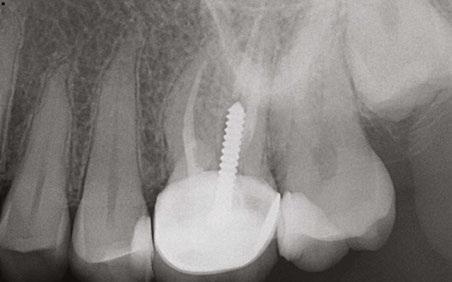

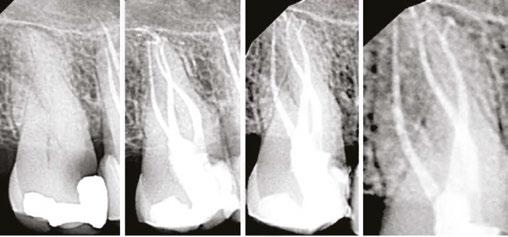

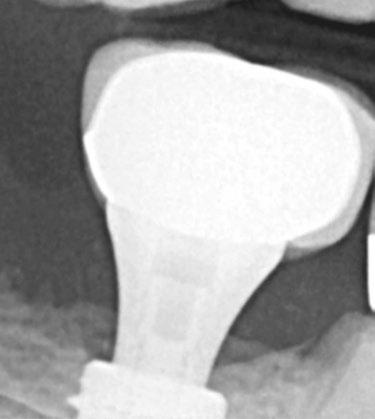

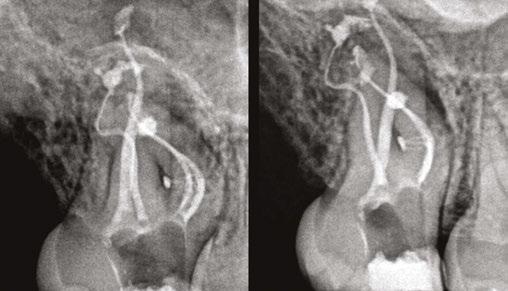

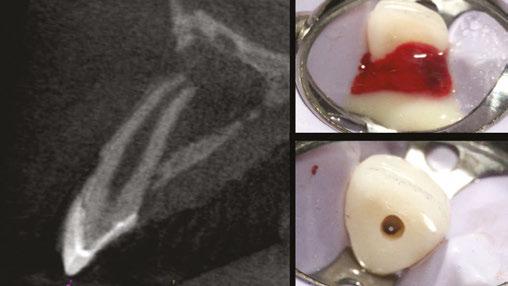

Figure 1: Acutely curved and calcified buccal canal right under upper left premolar crown margin; valuable information for access and management. No. 9 also has a PARL, which was only incidentally captured

Figure 2: Large PARL with destruction of the maxillary sinus floor and sinusitis as a result

more. In residency, I planned an autotransplantation on a patient in her early 20s whose lower left first molar had to be extracted. My plan was to move her upper right third molar to the extracted tooth’s position. I measured for this using a panoramic x-ray unit and ended up being far off — even after calculating for the known magnification of the pan. I published a paper about this case. Although it was successful, I could’ve done it better had I used the CBCT with more accurate information while I was planning. That was my first of many aha moments that has helped to shape my current imaging protocols.

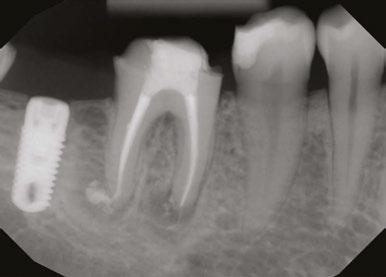

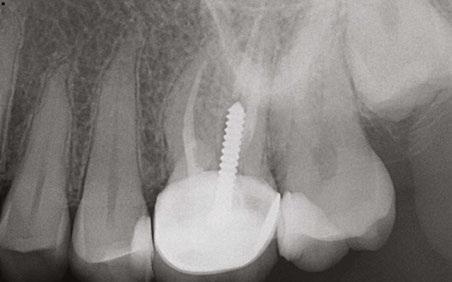

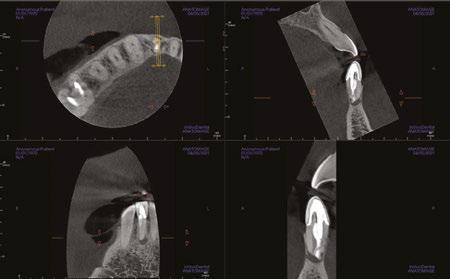

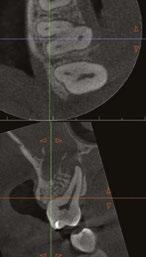

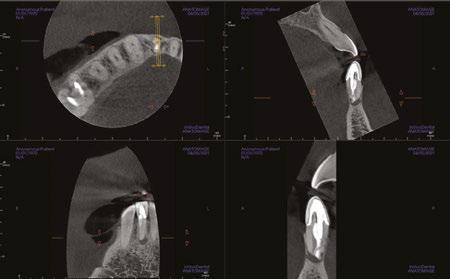

About 10 years after completing residency, I opened my own practice and invested in a DEXIS CBCT. Initially, I only used it for apicoectomies and retreatments. In time, I began to realize how helpful it was for all my cases. With the 3D-scan information (Figure 1), I could have saved myself some humbling experiences and surprises. Endodontists hate surprises, and we really hate failures! Once I started using my CBCT more frequently, I was able to appreciate things that would have otherwise been intra-op surprises and plan for them prior to starting the procedure. The 3D data allows me to properly assess prognosis, determine the best course of treatment, and plan that treatment with a level of precision that is impossible otherwise.

CBCT also allows me to capture issues I might have previously missed, whether related or solely incidental findings. Practitioners can visualize pathology/issues even when a patient is completely asymptomatic. I had a patient referred to me with an issue on one tooth. Cone beam revealed the patient had four teeth that unfortunately needed extractions, and all previous imaging gave no indication of this. Another patient presented for one tooth, but the CBCT showed several cracked molars and a perforated post. I was able to properly diagnose those problems as well. Sadly, those couldn’t be saved with endodontics, but knowing that up front saved time, unnecessary treatment, and resources for the patient.

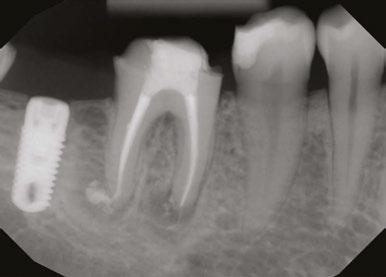

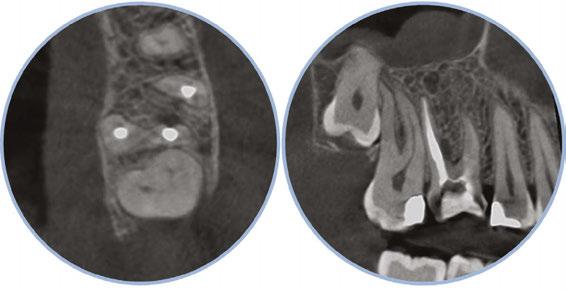

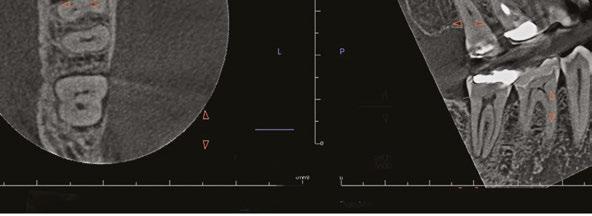

On a recent second molar case where I did not take a 3D scan prior to root canal treatment, the patient returned several days later still in pain! I took a scan and appreciated their deep split, forked in the last 5 mms of the distal canal (Figure 8). Without a CBCT scan, it’s easy to miss — I did! CBCT helps prevent this from happening by catching those variants and hard-to-find issues, which are not as rare as we think. This was another case that helped shape my current imaging protocol, so that now I scan nearly all of my patients. I honestly can’t imagine practicing without my CBCT unit — similar to when the microscope was introduced to endodontics.

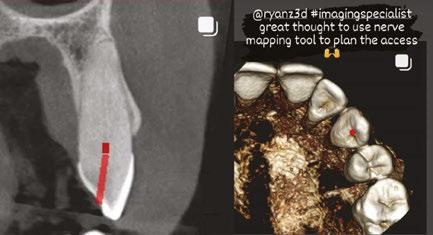

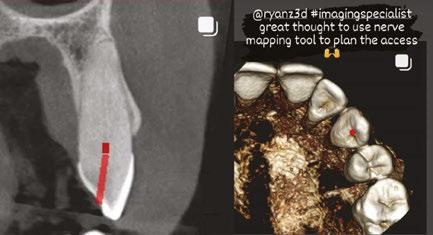

As I did not train with CBCT in residency, I really did have to “invest” the time into improving my interpretation with it. I purchased a CBCT/endodontics book, attended every webinar and lecture I could, began working more closely with oral radiologists, and did more training with my DEXIS Imaging Specialist, Ryan Zager. All of these were really worthwhile, and I’m still learning, but now I can better distinguish a true crack from beam hardening, etc. I feel way more confident in my interpretation. I have

to thank DEXIS mainly for that. Their technology and support is unparalleled.

How has CBCT affected your patient experience and outcomes?

CBCT has greatly improved the patient experience. As an endodontist, a good portion of the teeth I’m treating have already had endodontic treatment. CBCT allows me to figure out why the root canal didn’t work the first time: Sometimes there is a missed canal or a fracture. If something is failing, I need to know why it is failing in order to plan my treatment appropriately and to give the patient the best chance of saving the tooth, as well as

9 endopracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4 COVER

STORY

Figure 3: Second maxillary molar with external root resorption (ERR) with incidentally captured ERR on the lower mandibular first molar as well. When there is one tooth with resorption, be suspicious of other teeth with resorption, especially on younger patients

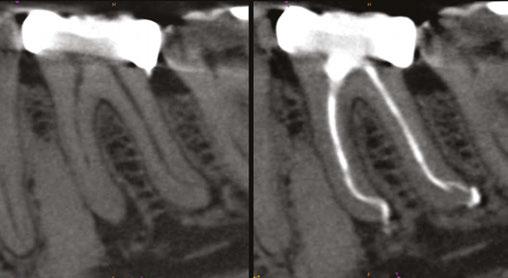

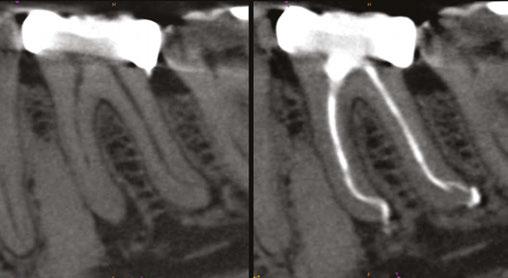

Figure 6: No PARL on PA film. Clear PARL on scan taken with medicament

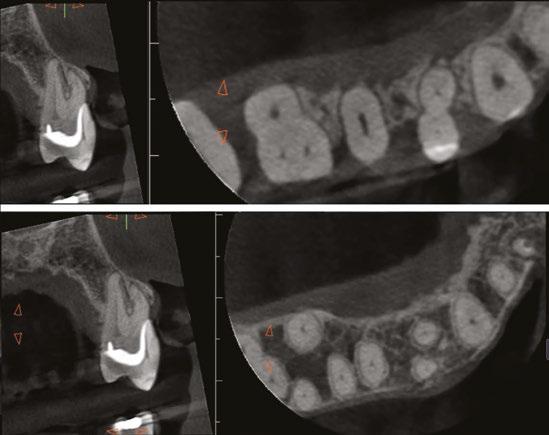

Figures 4 and 5: 4. Mandibular molar with a J-shaped lesion due to endo — not a vertical root fracture. Path of least resistance happens to be through a distal perio pocket, but this is an endo-perio lesion and not a VRF. Incidentally, a mucous retention cyst was captured in the sinus. 5. Healing after bridge removal and retreatment

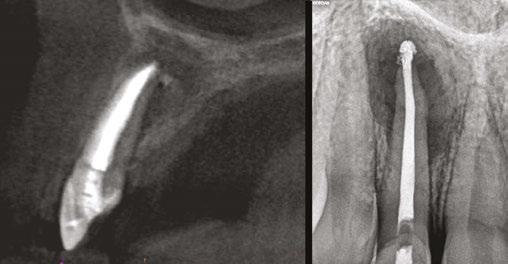

a realistic prognosis. Unfortunately, not all teeth can be saved. Some are not candidates for retreatment (Figure 11). Without a CBCT scan, it would be easy to attempt these retreatments only to discover the true problem mid-treatment, or worse — to think I had caused one (Figures 10 and 11). This added information not only helps the practitioner, but also provides patients a higher level of confidence and trust in you.

With retreatments, maybe the root canal looks completely fine on a PA or panoramic x-ray, but the patient says that it just doesn’t feel right. A cone beam can often reveal the cause of the patient’s discomfort. This could be that the tooth was perforated, cracked or has an unfilled canal, and the patient is totally justified in feeling like something’s wrong. Or sometimes the scan will show that there is another issue on an adjacent tooth or in the patient’s sinuses (causing their discomfort). When patients sense a problem but are told that there is not one (usually based on 2D radiographs), that’s not a great feeling. Being able to show the patient the CBCT scan and say, “You were right, and here’s the issue,” improves the patient experience.

I also find with 2D radiographs, patients don’t always understand what we’re trying to share with them in the image, even when they say they do. However, I’ve noticed when I review a 3D scan with patients, their eyes widen and they start nodding, especially when reviewing their volume rendering; it’s definitely helped with patient education and case acceptance. They see their teeth, their jaw, the infection in their bone (as a hole), and they understand this since they recognize themselves in 3D. This better understanding makes them more likely to accept the recommended treatment plan, leading to better outcomes. Ultimately, the patient is glad we took the CBCT scan. They’re thankful to have that information.

I also see a good amount of resorption cases. Without the scan, I can’t determine how large or destructive the lesion is. I cannot accurately determine the best course for these resorptive cases without knowing what they look like in 3D (Figure 3). I might approach it surgically without endo, or I might plan only for the endo and monitor it after. And, some cases need both at

the same time, or closely planned together, or a resorptive defect could be taken care of internally with the endo — all of that thought and planning comes from the scan; usually not possible with 2D imaging alone.

How has CBCT changed your treatment approach?

CBCT has transformed the way I treat patients in many ways. First, with cone beam, I can confidently offer a realistic prognosis on a tooth. Sometimes this means no treatment, saving me — and the patient — the time of pursuing a treatment that may not work, or has a poor prognosis.

The 3D scan also provides essential information to better treatment planning. Sometimes, this means knowing exactly the number of canals in a tooth, instead of hunting and based on

10 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 COVER STORY

Figure 7: Planned-for access with the scan info on this extremely calcified canine

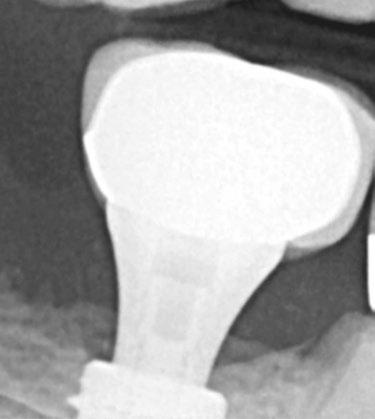

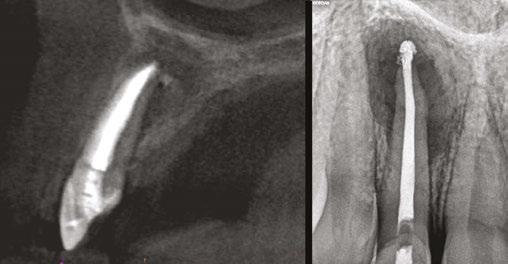

Figures 8 and 9: 8. Deep distal split with PARL. 9. Missed buccal canal; history of previous RCT, post, crown and apico

Figure 10: Retreatment consultation. PA from GD

Figure 11: Scan images show a previously existing strip perforation

what the literature suggests. And, when I know how many and where the canals are (Figure 13), I can take measurements on the scan and work more efficiently — measuring my working lengths of each canal, appreciating severe curves or calcifications, and knowing where canals can be expected to be located, again, rather than removing unnecessary tooth structure to find if it is there, or not!

As an endodontist, I often treat heavily restored teeth. I am often planning my accesses based on the scan’s information. This saves time and conserves more tooth structure. I’m not looking for canals that may or may not be there, and I’m looking for canals under the targeted/planned access — with the scan, I have an actual map (Figure 7)! CBCT directs me where to go and where to end. It reveals anomalies, which are more common than we think, so I can avoid iatrogenic incidents and provide less invasive treatments. Lower second molars with only two canals occur — often!

I’m also changing my treatment plans based on the data from my CBCT. Sometimes I look at a root canal treated PA and presume I know what I will do: a retreatment or an apico. Another recent, poignant case: a lower incisor with a previous RCT and a previous apico (Figure 9). Usually, once a tooth has had an apico, there may not be much left to offer and most of the time, the default is another apico, especially as there was very little room for an implant on the lower anteriors. I scanned the tooth and saw that a whole canal had been missed — twice! The RCT and the apico had left the buccal canal completely untouched. I changed my treatment plan based on this information!

Cracked teeth are also quite prevalent (Figure 12). Of course, I can suspect them clinically and with transillumination and other tests, I’m fairly confident in my diagnosis. Thankfully, the 3D scan proves it and shows the depth of these cracks and the angular defect. Without a CBCT, sometimes these cases are started unnecessarily.

Lastly, using CBCT also allows me to find issues that should be evaluated by another specialist. For example, when I capture incidental sinusitis, I can inform my patient to see an MD or ENT and can provide the 3D images to share with their physicians; or, to involve another dental specialist. (Figures 2, 4, 6, and 11 show incidental sinus findings.)

What advice would you give to your younger self?

I would tell my younger self that CBCT is as important of a tool for endodontics as a microscope and that I should get proficient with it early. I wish I had started using cone beam technology a lot earlier, on a lot more cases. Thankfully, I had tremendous support from DEXIS to help with my 3D-learning curve, but I wish I had become better with it earlier so that I could have used it to its potential even earlier.

What does the future of endodontics look like?

I would say that the impact of COVID will shape the future of endodontics. Many people delayed dental care during the pandemic, and now that they’re coming back into our practice, we’re seeing more complex cases and bigger problems. We’re seeing a phenomenal number of cases with cracked teeth, for example. Patients are stressed and anxious. All of this can be harder to manage and more challenging to treat.

We need to adapt to this new reality by staying calm, reassuring patients, and having empathy. We should also be taking advantage of all the technological advancements available to us — such as the OP 3D CBCT system from DEXIS — to support better diagnosis, treatment, and patient outcomes for these complex cases. When we have more confidence in our work, patients have more confidence in us. EP

11 endopracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4

COVER STORY

Figure 12: Cracked tooth

Figure 13: Five canaled maxillary molar with five portals of exit

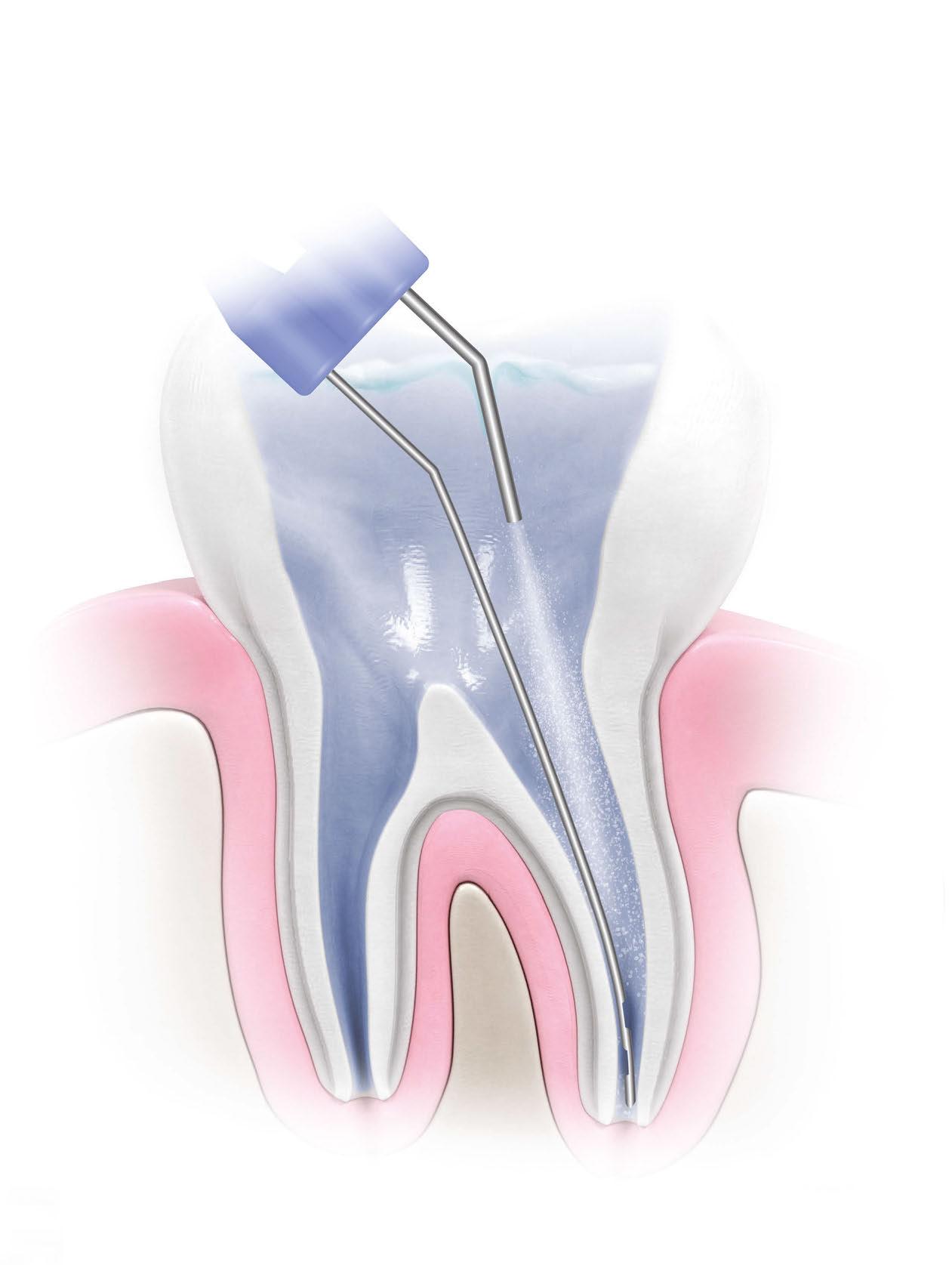

Negative and positive pressure irrigation: all-in-one!

Dr. Allen Ali Nasseh explores whether the positive and negative pressure needs of clinicians can be met with a simple and inexpensive device

During a conventional root canal procedure, the operator must manage the multiple liquids used to facilitate the access, chemomechanical instrumentation, and final obturation steps of the procedure. These liquids are used at each phase of the procedure and have specific functions.1 The access preparation phase requires water coolant spray from high- speed handpieces. Chemomechanical instrumentation requires positive pressure irrigation of disinfectants and chelators in the coronal and apical segments of the root canal, and finally, a bout of negative pressure irrigation is used by some clinicians to safely run a high-volume of disinfectant and chelating agents at the end of the procedure for enhanced apical cleaning prior to obturation.1-3 During each phase, multiple solutions including water, sodium hypochlorite, chelators, and lubricants help facilitate the process of root canal therapy and allow us to get rid of the infected pulp and biofilm, clear dentinal debris, and prepare a clean root canal surface ready for obturation.2

To manage these fluids, suction (negative pressure) is required to clear excess fluids and macro debris from the area. The operator, generally aided by a dental assistant, starts the procedure by a sequence of high-speed evacuation to remove the water coolant from the area after it is expressed from the handpiece, then switch to surgical suction to manage the debris and added irrigants during root canal instrumentation, and finally switch to another device for negative pressure suction at the end of

Allen Ali Nasseh, DDS, MMSc, received his dental degree from Northwestern University Dental School in Chicago, Illinois, in 1994 and completed his postdoctoral endodontic training at Harvard School of Dental Medicine in 1997, where he also received a Master of Medical Sciences (MMSc) degree in the area of bone physiology. He has been a clinical instructor and lecturer in the postdoctoral endodontic program at Harvard School of Dental Medicine since 1997 and the Alumni Editor of Harvard Dental Bulletin. Dr. Nasseh is the endodontic advisor to several educational groups and study clubs and is endodontic editor to several peer-reviewed journals and periodicals. He has published numerous articles and lectures extensively both nationally and internationally in surgical and nonsurgical endodontic topics. Dr. Nasseh is in solo private practice (MSEndo.com) in downtown Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Nasseh is the President and Chief Executive Officer for the endodontic education company Real World Endo® (RealWorldEndo.com).

Disclosure: Dr. Nasseh is a speaker and key opinion leader for Brasseler USA® and has received compensation for lecture presentations showcasing the company’s bioceramics.

Figure 1: The TotalVac Irrigation System showing its three main components: 1) The High-Speed Evacuation tip. 2) The Surgical Suction Adaptor. 3) The Negative Pressure Tubing

Figure 2: The high-volume evacuation tip is used during access and high-volume needs of cleaning and shaping procedure

instrumentation.3 These three phases often require three separate HVE suction outlets from the operatory unit with three separate components and a complicated workflow.

Recently, a novel modular device has been developed by the author that may help address the clinical needs for positive and negative pressure irrigation during these three phases of treatment through the application of a single system. The TotalVac Irrigation System (Brasseler USA®, Savannah, Georgia) is a disposable kit that allows the operator to use the aforementioned positive and negative pressure application of fluids during the root canal procedure through modular use of its components (Figure 1). The kit consists of three main parts:

1. High-Speed Evacuation Tip

2. The Surgical Suction Adaptor

3. The Negative Pressure Tubing

High-Volume Evacuation

This is the most intuitive component of the system. It duplicates the conventional high-volume evacuation; however, the nozzle size is in-between a large high-volume evacuation tip and a surgical suction tip. Therefore, this tip can generally be used for both applications during access preparation and normal evacuation of fluids during instrumentation. This item requires a single suction inlet from the operatory unit (Figure 2).

12 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 TECHNIQUE

Order online at Shop.BrasselerUSA.com

our

at

order

diameters to suit your specific needs Retail: $200.00 Special: $163.00 Kit includes: 25 high volume evacuation and surgical suction adaptors, 25 TotalVac tubings, 25 plastic suction tips, 25 25ga short delivery tips, and 25 30ga side vented long delivery tips *While supplies last. Offer subject to change. Promotion expires January 31, 2023. Invoice or statement prices may reflect or be subjected to a bundled discount or rebate pursuant to purchase offer, promotion, or discount program. You must fully and accurately report to Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare and/or any other

program,

such program, the discounted price(s) or net price(s) for each invoiced item, after giving effect to any applicable discounts or rebates, which price(s) may differ from the extended prices

and

information for your records.

your responsibility to review any agreements or other documents, including offers or promotions,

discount or rebate.

discounts must

calculated pursuant to the terms of the

purchase offer, promotion, or discount

B-5699-EP-12.22 ©2022 Brasseler USA. All rights reserved. Visit

website

BrasselerUSADental.com To

call 800.841.4522 or fax 888.610.1937.

federal or State

upon request by

set forth on your invoice. Accordingly, you should retain your invoice

all relevant

It is

applicable to the invoiced products/prices to determine if your purchase(s) are subject to a bundled

Any such

be

applicable

program. Participation in a promotional discount program is only permissible in accordance with discount program rules. By participation in such program, you agree that, to your knowledge, your practice complies with the discount program requirements.

TECHNIQUE

Surgical Suction Adaptor

If more precise suction application is needed than that provided by the High-Volume Evacuator, a Surgical Suction Adaptor can be fitted to the High-Volume Evacuator Tip, transforming it into a surgical suction (Figure 3). This allows an efficient conversion of high-speed evacuation to surgical suction, and vice versa. The dental assistant can merely take on-and-off this adaptor to switch between two types of suction instead of replacing the entire suction tip or requiring two separate HVE inlets with two separate suction tips on the operatory unit.

Negative Pressure Tubing

While high-volume evacuator and surgical suction are used by all clinicians doing endodontic therapy, applying suction capability closer to the treatment site without the aid of an assistant may be necessary in some clinical settings where a dental assistant may not be available during this phase of the procedure. This is common in dental school/residency and some private practice settings. Furthermore, some astute clinicians prefer using a large volume of irrigation inside the root canal with the safety of negative pressure techniques instead of mere positive pressure irrigation at the end of instrumentation.3 The purpose of the TotalVac Tubing is to address both of these needs through its modular design (Figure 4). The HVE fitting end of the tubing can be connected directly to an available HVE inlet in the operatory, or if an extra inlet is not available, the HVE fitting can be attached directly to the Surgical Suction Adaptor and connected to the High-Speed Evacuation Tip. This gives the operator the option of using only a single HVE inlet for all the various phases and applications of this device from access to obturation by using different configurations of tips in a modular manner. However, direct connection of the HVE connection into an available HVE inlet in the operatory is generally the most convenient configuration of this tubing according to the author.

The TotalVac Tubing bifurcates in two separate suction tubes. One end of tubing is connected to the manifold, a sleeve that houses a short Luer Lock needle that connects to the irrigation syringe for delivery of irrigation solution with simultaneous suction of excess fluid (Figure 5). The other end accommodates a handpiece that can be fitted with conventional Luer Lock delivery tips or needles to allow suction inside the root canal (Figure 6). The kit is supplied with a flexible plastic suction tip for average-size canals and a 30 gauge close-ended, side-vented needle that can be used for thinner canals. The same 30 gauge needle can also be used for positive pressure irrigation in combination with the plastic manifold at the other end of the TotalVac Tubing (Figure 7).

However, in negative pressure applications, it’s important to recognize that the use of this macro and micro level of suction deep in the root canal should really be limited to the end of instrumentation and after all the large pulp and dentinal debris have been removed from the canal to avoid clogging of the applicators tips.

The TotalVac Tubing assembly can operate under four distinct modes of operation. These modes are used based on the

Figure 3: The Surgical Suction Adaptor is connected to the High-Volume Evacuation Tip converting it into a surgical suction in a reversible manner

Figure 4: The bifurcated TotalVac Suction Tubing has an HVE connection end and two separate ends with a handpiece and a manifold for irrigation and suction

Figure 5: The TotalVac Manifold can accommodate various Luer Lock needles. In the kit, this is pre-fitted with a removable short needle that connects to an irrigation syringe

Figure 6: The Handpiece end of the suction tubing can accommodate the Plastic Suction Tip for macro suction or the 30 gauge needle for micro suction deep in the canal

Figure 7: The 30 gauge needle can also be used through the manifold to achieve deep positive pressure irrigation

stage of chemomechanical instrumentation (early or late) or the need for negative or positive pressure during irrigation (operator preference). Not all four modes are required during a single procedure, and the modularity of this device makes it possible for each operator to choose the modes he/she prefers for positive or negative pressure irrigation throughout the procedure.

14 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4

TECHNIQUE

The four possible modes of application consist of two positive pressure (irrigation) modes and two negative pressure (suction) modes.

Coronal Irrigation (Mode 1)

The short needle in the manifold is connected to your irrigation solution of choice, and irrigation is deposited into the chamber while excess is suctioned up through the manifold (Figure 8). This allows single-handed operation of the syringe combining irrigation with suction. The manifold suction assembly should be kept very close to the cavosurface area of the access to allow suctioning of the excess fluid. (Note: The use of a caulking material to achieve secondary isolation of a fluid tight seal around the rubber dam is generally recommended prior to all root canal therapy.) Since the manifold needle is short and does not reach in the depths of the canal, this form of irrigation allows effective irrigation in only the coronal half of the root canal. This mode can be combined with the handpiece applicator to achieve high-volume negative pressure toward the end of the procedure (Modes 3 and 4).

Apical Irrigation (Mode 2)

To achieve deeper irrigation using this one-handed technique, the short needle can be removed from the manifold and replaced with the 30 gauge needle. After threading the needle through the manifold, the tip can be bent 90 degrees for better access to the canal orifice (Figure 9). The needle can protrude up to 17 mm from the manifold reaching deep in the root canal. Longer needles are available for longer roots if deeper insertion is desired. Since the manifold has to be close to the cavosurface area of the access to achieve effective suction of excess fluids in the canal, it’s recommended to continue to use the Coronal Irrigation needle (Mode 1) until working length has been established and confirmed, and the canal has been enlarged adequately to accommodate the 30 gauge needle to a depth of 17 mm. Otherwise, inadequate insertion depth will not allow the simultaneous suction through the manifold as the suction nozzle won’t be close enough to the cavosurface area to capture the fluids. Establishing working length and some initial enlargement first also allows the operator to avoid accidental insertion of the tip beyond the apex.

Macro Suction (Mode 3)

After instrumentation is complete using positive pressure irrigation and all macro debris is removed, the canal is ready for obturation. At this point, many operators may elect to run a high-volume of disinfectant safely in the canal to remove any remnant tissue at the apical third of the canal.3 Here, the goal is to place a suction tube deep in the canal while irrigation solution is added coronally (Figure 10). The negative pressure created apically by suction will pull the coronally deposited fluids apically toward the suction tip and clear up the suction. This allows a large volume to flow through the canal without the risk of extru-

Figure 8: During Coronal Irrigation (Mode 1), the short needle deposits the solution inside the access preparation, and the suction through the manifold will capture the excess overflow. It’s important to keep the manifold as close to the cavosurface margin of the access for effective suction

Figure 9: During Apical Irrigation (Mode 2), the short needle in the manifold is replaced with the long 30 gauge needle allowing positive pressure irrigation up to 17 mm deep with simultaneous suction. This is used later in instrumentation after 17 mm depth can be achieved with the 30 gauge needle

Figure 10: Macro Suction (Mode 3) is the simultaneous use of coronal irrigation (Mode 1) with plastic suction tip inserted deep in the canal

Figure 11: Micro Suction (Mode 4) is the simultaneous use of coronal irrigation (Mode 1) with the 30 gauge needle on the suction handpiece inserted deep in the canal

sion. In this mode, the operator may insert the plastic dispensing tip on the handpiece to achieve suction deep in the canal while the assistant is depositing the irrigant on top with the aid of the coronal suction assembly (Mode 1). Therefore, Mode 3 can be summarized with the simultaneous use of the plastic suction tip on the handpiece with Mode 1. It’s important to use this mode toward the end of instrumentation to avoid clogging of the tip of the plastic suction tip with large tissue and debris remaining in the canal.

Micro Suction (Mode 4)

This mode of operation is identical to the Macro Suction (Mode 3), except that instead of using the plastic suction tip on the handpiece, the thinner 30 gauge needle is used on the handpiece in order to achieve an even deeper depth of insertion in thinner canals (Figure 11). The insertion depth is limited to inside the root canal and should only be used at the very end of the procedure after all large pulp debris and dentinal chips have already been removed to avoid clogging of the small needle port with large debris in this negative pressure mode.

15 endopracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4

Clinical Adaptation

TECHNIQUE

TotalVac is a modular irrigation device that has been designed to address the positive pressure and negative pressure irrigation needs of clinicians during root canal therapy.

Most clinicians will find their own preference for the combined use of positive or negative pressure irrigation when using this device. Most people will use the high-speed evacuation and adaptor for most suction needs and use the 30 gauge needle for conventional positive pressure irrigation on a syringe while using the plastic suction tip and the short needle on the manifold (as preassembled in the kit) for negative pressure irrigation toward the end of the procedure prior to obturation. Furthermore, having the plastic tip available during the procedure helps manage the fluid levels in the chamber and dry the canal from fluid during apex location stage for a more accurate measurement or drying the canals just prior to obturation.

The most practical clinical tip for using this system involves connecting the negative pressure tubing to a separate HVE inlet and resting the coronal suction manifold and short dispensing needle along with the handpiece and the plastic dispensing tip on a waterproof apron or tray on or near the patient’s chest for quick access. Then use the system for positive pressure irrigation at the beginning of the procedure and negative pressure at the end of the procedure. The plastic suction tubing can be used throughout the procedure to control the fluids in the chamber and canal with precision.

Limitations

Like every clinical device, this device has its limitations too. The depth of insertion of needle in Mode 1 is limited to the coronal area of the root and chamber or to 17 mm at the longest end in combination with the 30 gauge needle (Mode 2). Even though most clinicians limit their needle insertion in the canal to these same average depths, some operators may prefer needle insertion down to 1 mm short of the apex. In longer roots, a different length needle should then be used than that which is provided in the kit. Alternatively, normal positive irrigation with the 30 gauge needle and conventional syringe can be used, and this device’s use could be limited to its negative pressure and micro suction applications throughout the procedure. Another challenge is the use of multiple syringes with different solutions during Modes 1 and 2, which would require removing and reconnecting different solution syringes to the manifold using the same syringe tip, which may feel cumbersome if repeated multiple times.4 The most practical solution is combining TotalVac with and all-in-one irrigation solution such as Triton™ (Brasseler USA®, Savannah, Georgia) that can bypass the need for multiple syringes by combining all required solutions in one syringe. Triton contains sodium hypochlorite, chelating agents as well as surfactants and lubricants, all in a single syringe and can provide additional efficiency of using a

single syringe of solution from the beginning to the end of the procedure in conjunction with this device.5

Advantages

The most important advantage of this system is that it’s more versatile than other similar negative pressure devices in the past and can achieve the same negative pressure principles plus additional modes — all at a much lower cost than alternative options on the market. The system allows each operator to use it based on his/her own needs and priorities. Some operators may use all four modes, some may only use it for modes 1 and 2, and others may just apply deep negative pressure disinfection prior to obturation. Lastly, some may only want to use the plastic dispensing tip to manage the level of fluids in the canal with precision during chemomechanical instrumentation, apex location, and obturation while using conventional syringe irrigation.

Conclusion

TotalVac is a modular irrigation device that has been designed to address the positive pressure and negative pressure irrigation needs of clinicians during root canal therapy. This system can be customized based on each operator’s preference for positive or negative pressure irrigation at different phases of treatment through four modes of operation. Each clinician will find the optimum workflow that works best for him/her after understanding the various applications of this device.

While the system has some limitations, its relatively low cost and versatility can make it a practical solution for most irrigation needs chairside.

REFERENCES

1. Konstantinidi E, Psimma Z, Chávez de Paz LE, Boutsioukis C. Apical negative pressure irrigation versus syringe irrigation: a systematic review of cleaning and disinfection of the root canal system. Int Endod J. 2017;50(11):1034-1054.

2. Basrani, B. And Haapasalo, M. Update on Endodontic Irrigating Solutions. Endod Topics. 2012,27(1):74-102.

3. Kungwani ML, Prasad KP, Khiyani TS. Comparison of the cleaning efficacy of EndoVac with conventional irrigation needles in debris removal from root canal. An in-vivo study. J Conserve Dent. 2014;17(4):374-378.

4. Grawehr M, Sener B, Waltimo T, Zehnder M. Interactions of Ethylenediamine Tetraacetic Acid with Sodium Hypochlorite in aqueous solution. Int Endod J. 2003; 36(6):411-415.

5. Nasseh AA. Streamlining Effective Irrigation. Endodontic Practice US. 2022;15:(3) 10-12.

16 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4

EP

Lorem ipsum

Lorem ipsum

Internal root resorption: morphological aspects and clinical management

Drs. Fernando Goldberg, Denise Alfie, Juan Pablo Miraglia, Carlos Cantarini, and Gonzalo Garcia discuss treatment for

an inflammatory condition

Introduction

According to the American Association of Endodontists,1 internal root resorption (IRR) is a unique entity, unlike external root resorption, which can take different shapes. For IRR to occur, a damage or loss of the predentin and odontoblast layer must precede it, leaving the mineralized dentin wall exposed.2,3 A chronic pulpal inflammation is an additional factor needed to activate the action of the clastic cells on the dentin wall triggering its resorption. For the IRR to start, part of the pulp tissue must be vital to provide the clastic cells responsible for the resorption (active resorption).

This chronic inflammatory condition progresses until the pulp is removed or becomes totally necrotic, and at that point, the resorption ceases (inactive resorption). Haapasalo and Endal3 reported that the progress of internal root resorption is dependent on two things: 1) the pulp tissue at the resorption area must be vital, and 2) the pulp coronal to the resorption must be partially or completely necrotic, allowing bacterial infection and microbial antigens to enter the root canal. If the progression of the infection is slow and the necrosis of the whole pulp takes time, the IRR can continue and create a communication between the root canal and the surrounding periodontium, complicating the treatment with a poor prognosis. The IRR can be very small and radiographically not visible or produce a noticeable cavity of different shapes and sizes, generally with symmetrical walls, which appears as a radiolucent area that deforms the dentin wall.

In the radiographic image, the internal resorption cavity continues with the walls of the root canal. In contrast, in the case of an external resorption, the original shape of the canal remains radiographically intact because the resorption only projects over the root canal. The prevalence of IRR is very low. Haapasalo

Dr. Fernando Goldberg is from the Department of Endodontics, School of Dentistry, University del Salvador-AOA, Argentina.

Dr. Denise Alfie is in private practice.

Dr. Gonzalo Garcia is from the Department of Endodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Dr. Carlos Cantarini is from the Department of Endodontics, School of Dentistry, University del Salvador-AOA, Argentina.

Dr. Juan Pablo Miragila is a professor of Master of Endodontics at the Rey Juan Carlos University, Madrid, Spain.

Disclosure: The authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

and Endal3 suggest that this prevalence is between 0.01% and 1%, and it can be in any third of the root canal. Patel, et al.,4 detail several etiological factors proposed as antecedents of IRR: trauma, caries, periodontal infections, excessive heat generated during restorative procedures on vital teeth, orthodontic treatment, etc.

There is always a determining factor that is the reason for its initiation. However, the advancement of internal root resorption depends on bacterial stimulation. Patel, et al.,4 emphasize that without this stimulation, the resorption will be self-limiting.

Wedenberg and Lindskog5 divide IRR into two types: transient and progressive. The authors mention that the transient type develops in the absence of pulpal infection, while the progressive type requires continuous stimulation by bacterial inflammation.

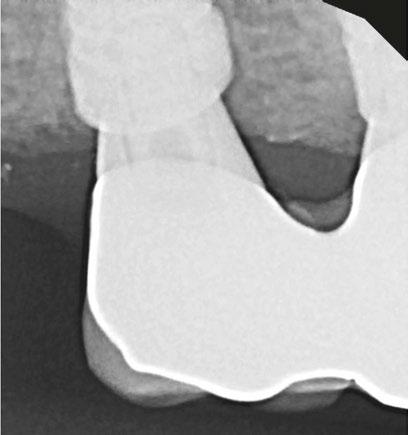

Many lesions are found accidentally during routine checkup radiographs, as teeth with internal resorption are typically symptom- free, and in cases of doubt, the CBCT can be of great help to clarify the diagnosis.6,7

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to analyze morphological and therapeutic aspects of IRR in different clinical situations.

Materials and methods

This study was performed with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Department of Coordination of General Research of the Argentinian Dental Association (resolution number 0422). The STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist and statement were followed.

18 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 CLINICAL

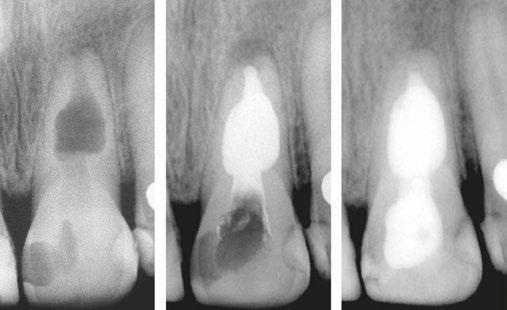

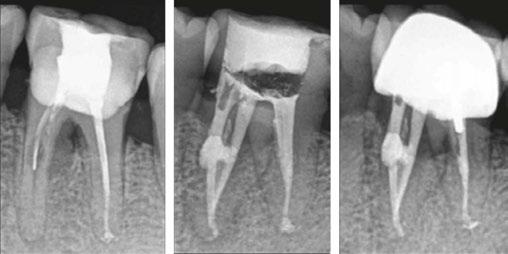

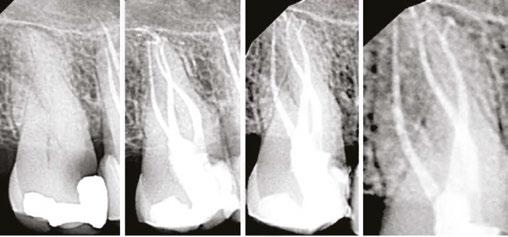

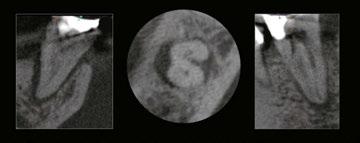

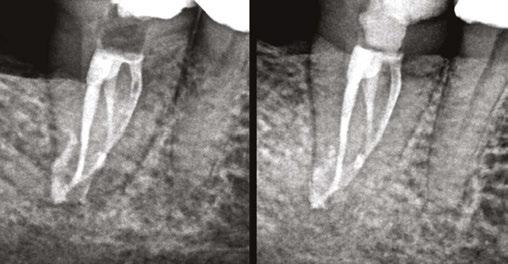

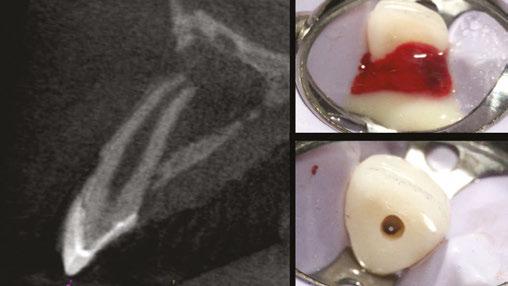

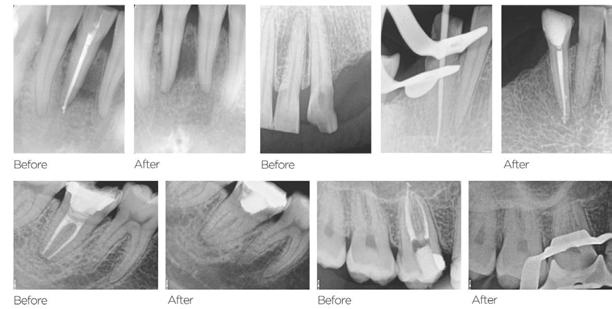

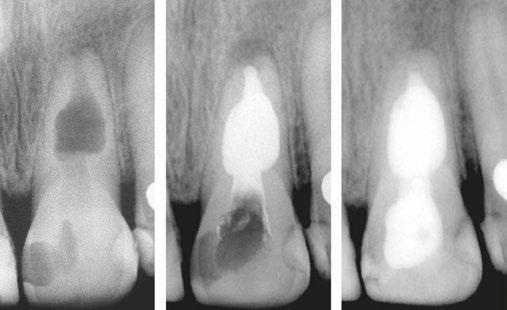

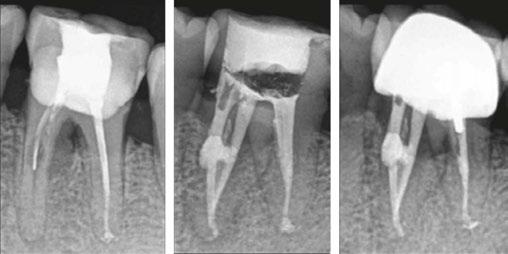

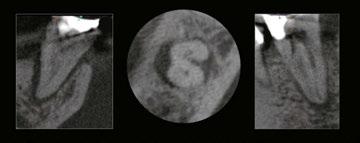

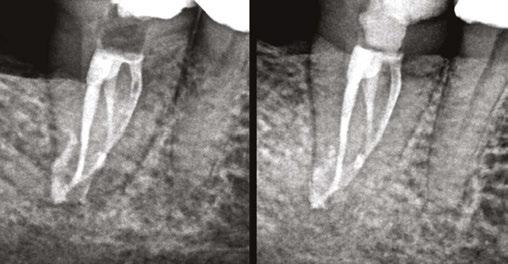

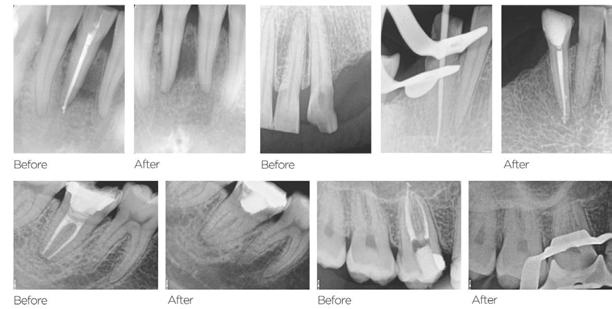

Figures 1A-1C: 1A. Preoperative X-ray. 1B. Immediate postoperative X-ray. 1C. Follow-up after 9 years and 10 months

Periapical radiographs and medical records corresponding to 48 teeth with IRR were collected from five different dental offices. The following aspects of the IRR were then analyzed: number of tooth in which it was found, location, presence or absence of periapical radiolucency, shape of the affected dentin walls, type of treatment performed, filling technique used, degree of adaptation of the filling to the resorption, presence of perforation communicating with the periodontium. Of the 48 cases diagnosed with IRR, all have been endodontically treated, and 29 of them have received initial treatments and 19 retreatments. Of the total number of cases, 29 had long-term follow-ups, while 19 do not have them.

The observations of the different aspects analyzed were carried out by five specialists in endodontics, and data were tabulated.

Results

The results of the items proposed in materials and methods are described in Tables 1 and 2.

Of the total, 29 had long-term radiographic follow-ups that ranged from a minimum of 6 months to a maximum of 25 years, with an average of 5 years, 4 months. Of the cases with radiographic follow-ups, 28 were considered successful and one failure (Table 2). Of the successful cases, 17 corresponded to treatments and 11 to retreatments (Figures 1A, 1B, 1C, and 2A, 2B, 2C). The tooth considered failed was a retreatment.

Discussion

IRR is a disease of the dental pulp that affects the dentin wall, which is reabsorbed by clastic action. It can occur in any tooth, although its presence is more frequent in those more susceptible to different kind of trauma. According to what was observed in this study, the upper incisors and the lower first molars are the most likely to present IRR, and this could be since the former are the ones that often suffer traumatic injuries, while the lower molars suffer more the action of orthodontic forces (Figures 3A, 3B, 3C).

The results of the present retrospective study are consistent with previous findings.8 Çaliişkan and Türkün8 reported that the most affected teeth with IRR were the upper incisors and agreed that the middle-third of the root was the area where it was located most frequently after an evaluation of 28 cases.

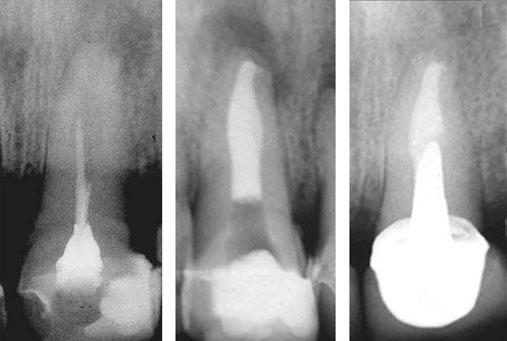

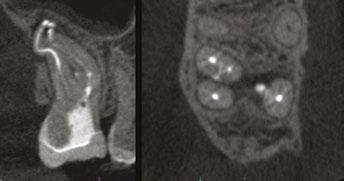

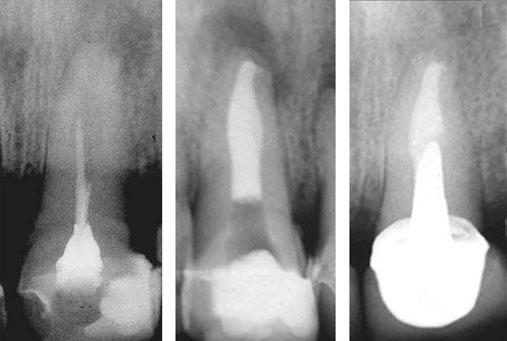

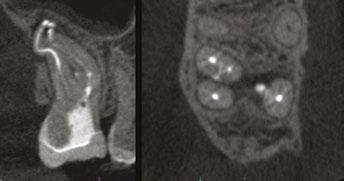

The radiographic appearances that generates the IRR are varied. The most common one observed in the present study was a circular shape with regular and symmetrical walls specially in single-rooted teeth (Figure 4A), although there were also some

Figures 2A-2C: 2A. Preoperative X-ray. 2B. Immediate postoperative X-ray. 2C. Follow-up after 18 years and 6 months

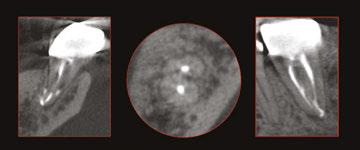

Figures 3A-3C: 3A. Preoperative X-ray. 3B. Immediate postoperative X-ray. 3C. Follow-up after 4 years

irregular ones with asymmetrical walls (Figure 4B). In molars, when resorption affects the pulp chamber, it was commonly seen as an irregularly shaped radiolucent cavity2 (Figure 4C).

Most of the IRR develop without clinical symptoms, although as they progress, necrosis of the pulpal tissue may progress, and pulpal symptoms become noticeable.3

When the IRR is diagnosed, root canal treatment is the treatment of choice. The prognosis is, in general, very good except when the resorption has perforated the dentin wall connecting the root canal with the periodontium.3,4,8 In many cases, this communication can’t be observed radiographically. Before performing endodontic therapy, it is always important to evaluate if the tooth is deemed restorable and what kind of reconstruction is needed. Properly cleaning and shaping the area of resorption may be very challenging because in many cases, it presents a complex access.

20 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4

CLINICAL

2: Treatments and results

29From 6 months to 25 years Successes 28Treatments 17 Retreatments 11 Failures 1 Retreatment

Characteristics

the IRR

Max. Cl (17) Max. LI (9) and 1st MM (9) Others (13)

middle third (19), apical (16), coronal (13)

regular 31, irregular 17

radiolucencyYes 36, No 12

29, Retreatment 19

technique Thermoplasticized gutta-percha 45, Others 3

Very

43, Poor 5

Table

Follow-ups

Table 1:

of

Teeth

Location

Shapes

Periapical

Treatment performedTreatment

Obturation

Filling adaptation

good

42

Periodontal communicationYes 6, No

Different strategies have been proposed for instrumentation, such as use of sonic and ultrasonic activation of sodium hypochlorite,9,10 activation with the XP-Endo® Finisher file10 (FKG, Dentaire SA, La Chaux de Fonds, Switzerland), the use of precurved files in the RDI area,11 multiple visits using calcium hydroxide as intracanal medication, and sodium hypochlorite as irrigant in order to improve the disinfection of areas that are difficult to access.3,4

In the present study, calcium hydroxide was used as intracanal medication in only three of the 48 cases, while in 45 cases, the treatment was carried out in one single visit. However, complete removal of the calcium hydroxide used as temporary medication can be difficult in canals with normal morphology,12-14 so the situation would be aggravated in teeth with IRR given the difficulty of removing it from the retentive cavity of the resorption. Topçuoğlu, et al.15 and Marques-da-Silva, et al.16 used different irrigation techniques in simulated IRR, observing that none of them completely removed the calcium hydroxide from the resorptive cavities.

Regarding the obturation, the best results were observed with the use of thermoplasticized gutta-percha injection techniques.3,4,8,17-20 In this study, a thermofluid gutta-percha technique was used in 45 teeth, presenting adequate filling adaptation to the dentin walls in 43 of those cases. It is important to high-

light the studies by Ulusoy, et al.,21 who mention that the ex vivo use of System B™ and Obtura II in IRR fillings produced a temperature increase above the critical limit. In any case, these authors consider that the few seconds of thermal increase and the cooling action of the periodontium ligament in vivo would be a barrier to avoid thermal damage.

When the IRR communicates with the periodontium area, MTA, Biodentine® (Septodont USA) or similar product is the filling of choice,3,4 (Figures 5A, 5B, 5C).

Conclusions

The prevalence of IRR was higher in the upper incisors and lower molars, being located predominantly in the middle and apical thirds of the root canal. Its walls are generally regular and continuous. The use of thermoplasticized gutta-percha techniques allowed the adequate filling of the IRR cavities. Root canal treatment and retreatment provided adequate conditions to achieve a successful outcome.

REFERENCES

1. American Association of Endodontists, Communique, By Blicher B. Differentiating resorption January 2021;5:1-5.

2. Tronstad L. Root resorption-etiology, terminology, and clinical manifestations. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1988;4:241-252

3. Haapasalo M, Endal U. Internal inflammatory root resorption: the unknown resorption of the teeth. Endod Topics. 2006;14:60-79.

4. Patel S, Ricucci D, Durak C, Tay F. Internal root resorption: a review. J Endod. 2010;(36)7:1107-1121.

5. Wedenberg C, Lindskog S. Experimental internal resorption in monkey teeth. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1985;1:221-227.

6. Patel S, Dawood A, Wilson R, Horner K, Mannocci F. The detection and management of root resorption lesions using intraoral radiography and cone beam computed tomography: an in vivo investigation. Int Endod J. 2009;42(9):831-838

7. Kamburoğlu K, Kurşun Ş, Yüksel S, Öztaş B. Observer ability to detect ex vivo simulated internal or external cervical root resorption. J Endod. 2011;37(2):168-175.

8. Çaliişkan MK, Türkün M. Prognosis of permanent teeth with internal resorption: a clinical review. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1997;13(2):75-81.

9. Stamos DE, Stamos DG. A new treatment modality for internal resorption. J Endod. 1986;12(7):315-319.

10. Hernandez Restrepo C, García G, Alfie D, Oyhanart SR, Goldberg F. Efficacy of different procedures in removing radiopaque organic material from simulated internal root resorption cavities: an ex vivo study. Endod Practice US. 2020;13:24-27.

11. Manzur E. Evaluación in vitro de diferentes técnicas para la instrumentación de reabsorciones dentinarias internas simuladas. Rev Asoc Odontol Argent. 2003;63(5-6):107-111.

Figure 4A-4C: 4A. Maxillary lateral incisor with an internal resorption at the coronal third. 4B. Mandibular canine with an internal resorption in the middle-apical area. 4C. Mandibular molar with an irregular internal resorption in the coronal portion Figures 5A-5C:

12. Wiseman A, Cox TC, Paranjpe A, et al. Efficacy of Sonic and Ultrasonic Activation for Removal of Calcium Hydroxide from Mesial Canals of Mandibular Molars: A Microtomographic Study. J Endod. 2011;37(2):235-28.

13. Alturaiki S, Lamphon H, Edrees H, Ahlquist M. Efficacy of 3 different irrigation systems on removal of calcium hydroxide from the root canal: a scanning electron microscopic study. J Endod. 2015;41:97-101.

14. Zorzin J, WieBner J, WieBner T, et al. Removal of radioactively marked calcium hydroxide from the root canal: influence of volume of irrigation and activation. J Endod. 2016;42(4):637-40.

15. Topçuoğlu HS, Düzgün S, Ceyhanlı KT, et al. Efficacy of different irrigation techniques in the removal of calcium hydroxide from simulated internal root resorption cavity. Int Endod J. 2015;48:309-16.

16. Marques-da-Silva B, Alberton CS, Tomazinho FSF, et al. Effectiveness of five instruments when removing calcium hydroxide paste from simulated internal root resorption cavities in extracted maxillary central incisors. Int Endod J. 2020;53(3):366-375.

17. Goldberg F, Massone EJ, Esmoris M, Alfie D. Comparison of different techniques for obturating experimental internal resorptive cavities. Endod Dent Traumatol. 2000;16(1):116-1121.

18. Goldberg F, Manzur E, Mignanelli ME. Estudio comparativo entre diferentes técnicas para la obturación de reabsorciones internas creadas artificialmente. Rev Asoc Odontol Argent. 2001;89:125-1259.

19. Gencoglu N, Yildirim T, Garip Y, Karagenc B, Yilmaz H. Effectiveness of different gutta-percha techniques when filling experimental internal resorptive cavities. Int Endod J. 2008;41(10):836-842.

20. Keles A, Ahmetoglu F, Uzun I. Quality of different gutta-percha techniques when filling experimental internal resorptive cavities: A micro-computed tomography study. Aust Endod J. 2013;40:131-135.

21. Ulusoy ÖI, Yilmazoglu Z, Görgül. Effect of several thermoplastic canal filling techniques on surface temperature rise on roots with simulated internal resorption cavities: an infrared thermographic analysis. Int Endod J. 2015,48(2):171-176.

22 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4

CLINICAL

5A. Preoperative X-ray. 5B. Immediate postoperative X-ray. 5C. Follow-up after 1 year and 9 months EP

YOU’LL BE SMILING... KNOWING WE ARE THE ONLY

solely focusing on the “practice” part of your endodontic practice. We partner with endodontists

to empower them

that, while

you to

your

Partners

partners

administrative

Endodontic Partnership led by Endodontists. Our family of brands 305-206-7388 I Endo1partners.com

Imagine

nationwide

to do just

helping

achieve

goals. Endo1

supports our endodontic

by implementing business best practices to reduce

burden, increase efficiency, and prioritize growth.

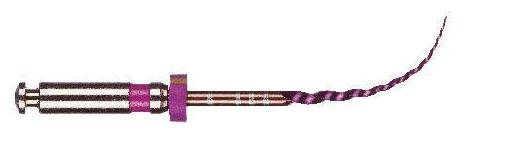

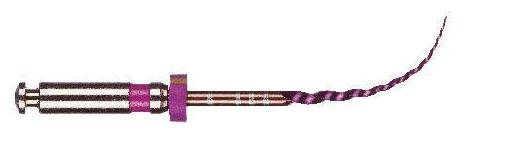

Rotary negotiation as first file to length

Drs. L. Stephen Buchanan and Christophe L.M. Verbanck discuss a modern

answer to an age-old issue

Functional characteristics of file geometry and metallurgy

The rotary file rule

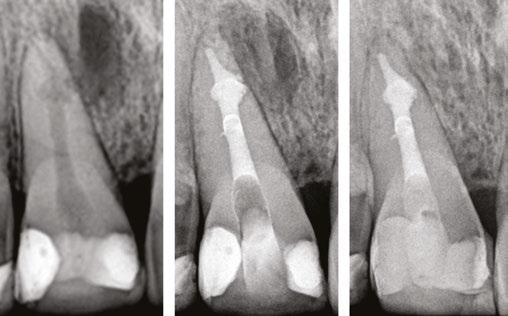

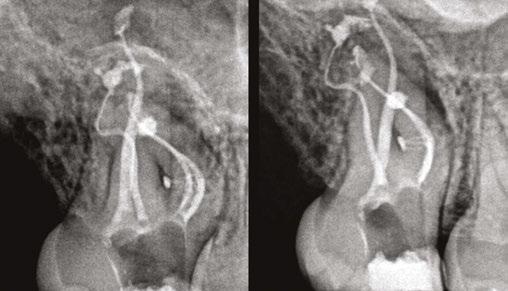

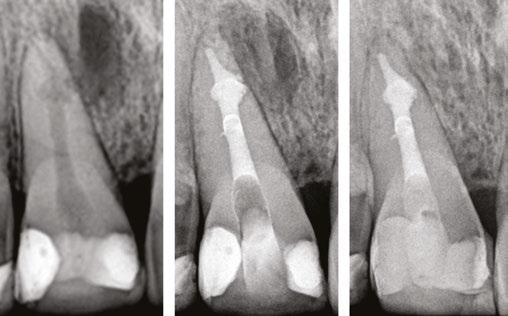

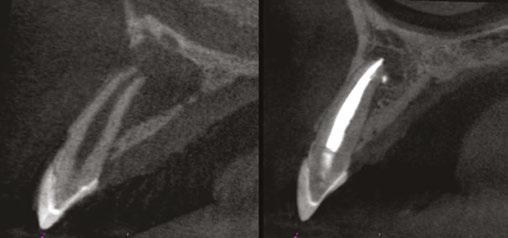

Since the beginning of the nickel-titanium (NiTi) rotary file revolution, we have been nearsighted in our expectations of what is possible. For the 30-plus years we have had them in our arsenal (Haapasalo and Shen, 2013), our wonder over what mechanized instrumentation could do for us was limited by the instruments we had at the time, by our conceptual misunderstanding of what is really going on when we use hand files to negotiate small complex canal forms, and by our fear of damaging patient’s teeth. This is completely understandable considering the hidden and tortuous canal paths we encounter when we thread the first file to length (Figure 1). For these reasons, endodontic educators and clinicians came to believe that rotary files should only be used for shaping after a glide path to the terminus has been secured with hand-operated K-files. The realistic concerns were that rotary files would break if used as first file to length; that rotary files used this way would block, ledge, or lacerate apical anatomy; and that rotary files would resist advancing through apical curvatures or beyond apical impediments.

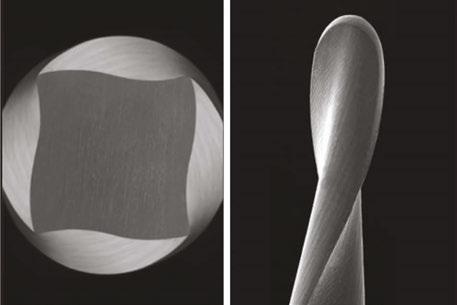

Figure 1: This CT reconstruction of the apical third of a premolar root shows the challenge we often encounter when negotiating root canals to their terminal lengths. In just these two canals, there are five potential impediments to passage of the first negotiating file to length

At the advent of the rotary file revolution, before heat treatment was used to reduce the shape memory of NiTi alloy, file breakage was a serious problem that was mostly resolved by procedural workarounds such as crown-down shaping (using a big-to-small file order) to reduce torsional stresses delivered to the smallest files (Peters, 2004). This has changed radically as today’s heat-treated rotary files have the ability to unravel and wind up backwards before coming apart under stress (Peters, et al., 2012; Santos, et al., 2013); so for the first time, they can be used as first file to length (FFL) before any coronal shape has been cut (Buchanan, 2019). Conversely, without heat-treated NiTi files, rotary negotiation as FFL is untenable.

L. Stephen Buchanan, DDS, FICD, FACD, Dipl. ABE, has been lecturing and teaching hands-on endodontic continuing education courses for over 30 years, both in his state-of-the-art training facility in Santa Barbara, California, as well as in dental schools and at meetings around the world. He currently serves as a part-time faculty member in the endodontic departments at the University of the Pacific’s Arthur Dugoni School of Dentistry and the University of California at Los Angeles as well as being the Endodontic Advisory Board Member to the Academy of General Dentistry. Dr. Buchanan is nationally and internationally known for his 50-plus endodontic procedural articles as well as his expertise in the research and development of new endodontic technology, instruments, and techniques. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontists, a Fellow of the International and American College of Dentists. Dr. Buchanan also maintains a private practice limited to Endodontics in Santa Barbara, California.

Christophe L.M. Verbanck, DDS, MSc, obtained his Master of Dentistry at Gent University in 2009. He specialized in endodontics, graduating after a 3-year postgraduate training program from the same university. Since 2010 he has worked in several multi-disciplinary and endodontic referral practices all over Flanders. In January 2016, together with his wife, he started his own referral practice for Endodontics, Lovendo, in Lovendegem (Belgium). He regularly teaches endodontics to general dentists and holds workshops on the application of endodontic techniques.

Disclosures: Dr. L. Stephen Buchanan is a co-founder of PlanB Dental.

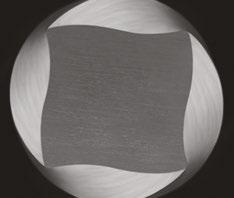

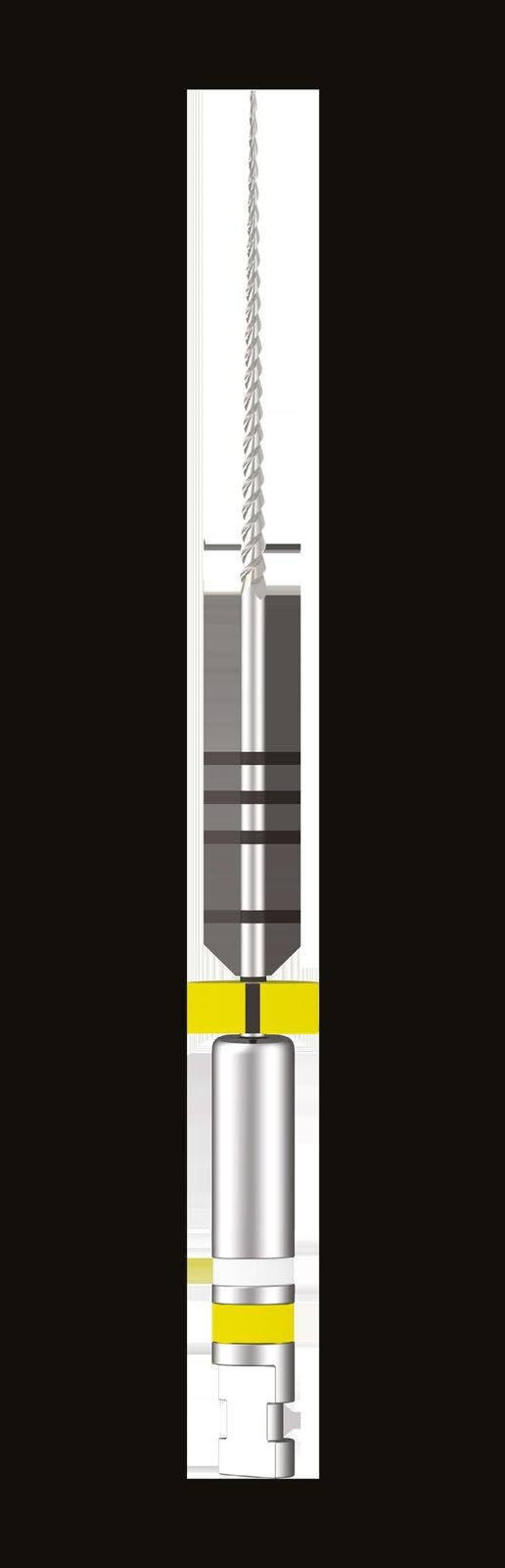

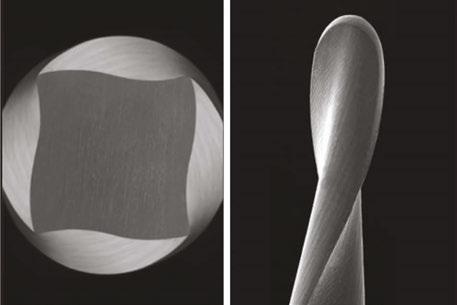

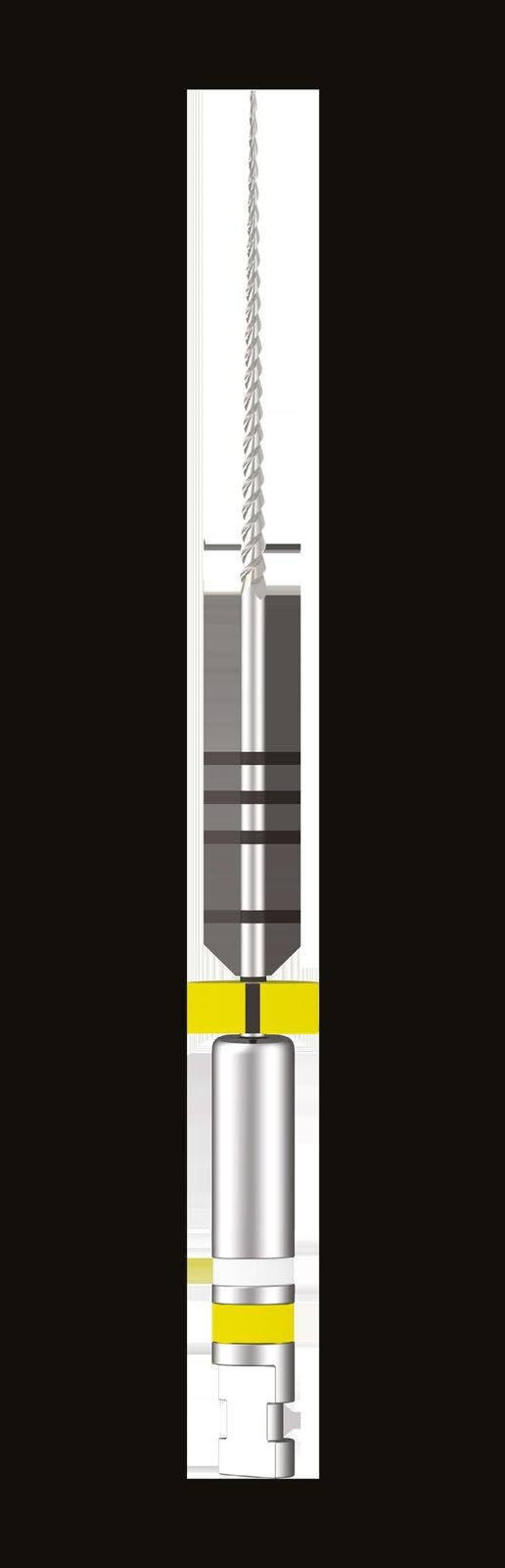

The other technological advances in rotary file manufacturing have been achieved through improved flute angles, file tip geometry, and cross-sectional core strength (Figure 2). Typical tapered-file flute geometry has flute angles that are tighter at the shank end and more open near the file tip, which contributes to files threading into canals when their shank end flutes approach the orifice level. When that happens, file tips are propelled into the canal; and if they have lesser flute angles, they are more likely to hang an edge, a major cause of file separation. Files with consistent flute angles have greater tip flexibility and strength, while their shank end flutes resist threading and cut more effectively. This flute-angle geometry is imperative when using rotary instruments as FFL (Buchanan, 2019). Without it, breakage too easily occurs, even when using a light touch and a low-torque limit. Adequate core strength is also critical in these narrowest of files; miniKUT Rotary Files have different cross-sectional geometries, depending on their purpose — just two flutes for the larger shaping files to aid cutting function, and four flutes for the smaller EZP rotary negotiating files to add torsional strength (Oh, et al., 2010).

With these engineered solutions that minimize breakage, the only remaining concern about using rotary negotiation as FFL is the possibility of rotary file tips blocking, ledging, or perforating the often tortuous apical regions of canals. This is why file tips on these rotary negotiators are fully radiused. This extremely passive tip geometry not only prevents ledging and perforation, but also actually causes these rotary files to kind of “bump” around impediments that would absolutely be engaged by an unbent hand file. While blockage is always a concern when advancing a file into apical regions of vital canals during negotiation procedures, it turns out that the way hand files function when used in a watch-wind, push-pull manner is actually the cause of most apical blockage.

24 Endodontic Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 TECHNIQUE

“If you obey all the rules, you miss all the fun” — Katharine Hepburn

TECHNIQUE

Deconstructing hand file negotiation, learning to love motor-driven negotiating files

Before we move on, it’s important to thoroughly understand what happens in apical regions when hand K-files are used as first file to length during negotiation. It’s not quite what you think. Hand K-files are used in many ways, including watchwind, push-pull, 1/4 turn-pull, and the Balanced Force method.

Forty-seven years ago, 1/4 turn-pull was shown to ledge curved canals, so that’s out (Weine, et al., 1975). The Balanced Force (Roane, et al., 1985) manner of cutting with K-files, while the most effective way to move a hand-operated K-file through dentin, is not a good technique when using files smaller than a No. 15 K-file. That leaves us with watch-wind, push-pull.

Watch-wind, Push-Pull (WWPP) filing action is accomplished by inserting the file into the canal (with a lubricant filling the access cavity) until it binds. Apical pressure is applied to the file and it is then rotated back and forth (watch-winding), limiting the movements to a 1/4 turn in either direction, wherein the file usually moves apically and tightens in the canal. The file is then used in three to four push-pull filing motions to loosen it at that position in the canal. After that, apical pressure is reapplied to the file; it is again watch-wound to advance it further in the canal, followed by push-pull filing to advance again. Rinse and repeat until the file does not advance during watch-winding with moderate apical pressure.

What actually happens near the canal terminus during apical advancement with this method? As the first file progresses to length in these small canals, it pierces and macerates pulp tissue, then leaves it in the apical third, risking compaction by the next larger file used. That is why we need to use lubricants and patency files during this procedure to avoid apical blockage by pulp remnants or, when it occurs, to pick a hole through the apically compacted debris, break it loose, irrigate it out of the canal, and then run another cutting cycle. Reciprocating motor-driven files cut and move even more debris in an apical direction in less time than a hand file when used with the WWPP technique, so it is too dangerous to use for rotary negotiation. In the authors’ opinion, reciprocating handpieces are a step backward in apical function.

The only motion that won’t work at all with hand K-files is continuous rotational cutting by hand. When small K-files are in use, continuous rotation in the same clockwise direction threads the file into the canal until its tip binds canal walls; whereafter, if CW rotation is continued, the file shank is literally twisted off the bound-up file tip. Constant rotary file rotation works because of a) the torsional strength of NiTi, and b) the centripetal force provided by the file spinning at 500 rpm (8 times a second), which bangs the flutes against the dentin, cutting it with a fraction of the torsional stresses delivered by hand files continuously rotating in a CW direction.

In fact, one of the greatest, but least appreciated, advantages of even the earliest rotary files was that for the first time, these rotary files removed the debris cut from the canal — carried in its flute spaces — instead of leaving cut debris in place to cause trouble. This functional characteristic of rotary files once again comes to play a major role when they are used as FFL.

During the development of rotary negotiation files, the overriding concern was preventing file breakage and avoiding apical blockage, ledging, and perforation (Plotino, et al., 2020). Surprisingly, the outcome was not a technique just as safe as hand-driven K-files. The outcome was a technique that is faster, easier, better, and safer than hand file manipulation.

Figure 2: PlanB’s 15-.03 miniKUT EZP Rotary Negotiation File. Note the square cross section and the aggressive rake angles of the four flutes, providing torsional strength with cutting efficiency (middle). The completely passive “duckbill” file tip geometry eliminates the chance of ledging curved canals during rotary negotiation as FFL (right). The side view shows flute angles that are consistent from tip to shank, preventing file threading and tip breakage (left)

No.

EZP

With rotary negotiation, patency is not an issue because pulp tissue is broached out of the canal and augured into the pulp chamber by the constantly spinning file (Ha, et al., 2016). Conversely, hand K-files used with WWPP motions encourage apical blockage and tend to engage the smallest canalar impediments rather than glance by them as rotary negotiation files do.

The simple fact is that rotary negotiation as FFL is superior to hand file negotiation (Figures 3,4 and 6).

Handpiece + EAL = Smart Handpiece + EAL + Rotary Negotiation = Genius