Finding his true

PHARMACEUTICALS, SURGICAL SUPPLIES, GRAFTING & EXCEPTIONAL SAVINGS

PROMOTING EXCELLENCE IN IMPLANTOLOGY FAQs Special Section n 4 CE Credits Available in This Issue* Winter

implantpracticeus.com

calling Dr. Alex Bachoura and his dental journey

2022 Vol 15 No 4

Communicating periodontal issues across dental implant platforms Drs. Stuart Segelnick and Mea A. Weinberg

Dental infections, part 2 — prophylaxis: help avoid antimicrobial resistance Wiyanna K. Bruck, PharmD, and Jessica Price Creating a memorable patient experience JoAn Majors

The leading Oral Surgery partnership group Our family of brands OS1partners.com I 305-206-7388 At OS1, we provide the resources needed to help you grow your practice. Our support will take the stress of practice management off your plate so you can focus on providing high-quality care to patients.

Editorial Advisors

Jeffrey Ganeles, DMD, FACD

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS

Jonathan Lack, DDS, CertPerio, FCDS

Samuel Lee, DDS

David Little, DDS

Ara Nazarian, DDS

Jay B. Reznick, DMD, MD

Steven Vorholt, DDS, FAAID, DABOI

Brian T. Young, DDS, MS

CE Quality Assurance Board

Bradford N. Edgren, DDS, MS, FACD

Fred Stewart Feld, DMD

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS, MAGD, FPFA, FACD, FADI, DICOI, DADIA

Justin D. Moody, DDS, DABOI, DICOI

Lisa Moler (Publisher)

Mali Schantz-Feld, MA, CDE (Managing Editor)

Lou Shuman, DMD, CAGS

© MedMark, LLC 2022. All rights reserved. The publisher’s written consent must be obtained before any part of this publication may be reproduced in any form whatsoever, including photocopies and information retrieval systems. While every care has been taken in the preparation of this magazine, the publisher cannot be held responsible for the accuracy of the information printed herein, or in any consequence arising from it. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the opinion of either Endodontic Practice US or the publisher.

ISSN number 2372-6245

The perfect smile

The first work by Leonardo Da Vinci that caught my attention was “The Skull c. 1489,” a sketch of the human skull. Frontal facing, sectioned in the midline with the left half showing the complete three-dimensional view and the right side showing a coronal section at the level of the mental foramen — the attention to detail is astonishing. The maxillary tooth in the coronal section is multirooted; the mandible is correctly sketched with an outer solid layer of cortical bone, while the inner layer is cavernous to depict medullary bone. The maxillary and frontal sinuses are accurately depicted. Its anatomical detail has withstood the test of time.

It’s as if Da Vinci were looking at a CBCT of a person and sketching the image on paper. But he wasn’t. In fact, his sketch predates CBCT technology by 500 years. So how did he do it? Was he merely a gifted artist? After all, his painting “The Mona Lisa” has been attributed the world’s most recognized smile.

Da Vinci was a gifted artist, but his true gifts surpassed taking pencil or brush to paper or canvas. His true gifts were rooted in his ability to observe his surroundings and develop a deep understanding of why things occur. Years of dissecting cadaver heads in the middle of the night in hospital basements deepened Da Vinci’s understanding of bony anatomy as well as inserting and attaching locations of facial muscles used in the process of smiling. His greatest gift, in my opinion, was his relentless pursuit of improvement. While there is no exact time frame for how long the “Mona Lisa” took to complete, in the biography, Leonardo Da Vinci, author Walter Isaacson states Da Vinci worked off and on this painting from 1503 to 1517 — 14 years for one work. A master unwilling to call his own work complete until he deems it perfect.

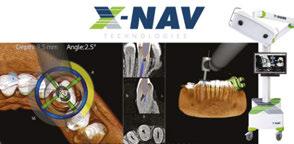

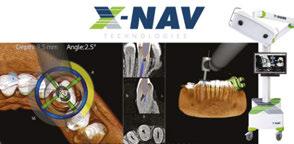

Observe. Innovate. Improve. As an oral surgeon committed to delivering optimal implant results to my patients, I use these three ideals to guide the continual evolution of my practice. Members of a patient’s dental implant team (restoring doctor, implant surgeon, dental laboratory technician) cannot be stagnant and unwilling to embrace at least some of the digital technology, which allows us to communicate more effectively, diagnose more completely, plan more precisely, and execute a treatment plan more accurately.

Da Vinci lived during the Renaissance, a period that saw a cultural rebirth of artistic, political, and economic ideals. Aren’t we, as oral health providers, living through a “Dental Renaissance”— a period when advancements in image acquisition (intraoral scanning, CBCT, digital photography, photogrammetry, facial scanning) and dental implant guided surgery (static guided surgery, dynamic navigation, robotic surgery) are allowing us to perform more complex dental implant procedures in a minimally invasive surgical manner to achieve more predictable, esthetic results than in any other time?

Leonardo Da Vinci would not recognize the world will live in today. Even with his fantastical imagination, he would probably not believe most of the creature comforts we have at our disposal. But what he would recognize and understand, what has not changed, and what should never change, is our pursuit of achieving the perfect smile for our patients.

Michael J. Hartman, DMD, MD

Michael J. Hartman, DMD, MD, completed his residency training in oral and maxillofacial surgery at the University of Maryland Medical Center in 2008. Dr. Hartman’s private practice — Hartman Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery — focuses on using cutting-edge technology to improve patient outcomes. He is also the president of Digital Provisionalization Technologies, specializing in provisional components using X-Guide® dental implant procedures.

1 implantpracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4

Winter

n Volume 15 Number

INTRODUCTION

2022

4

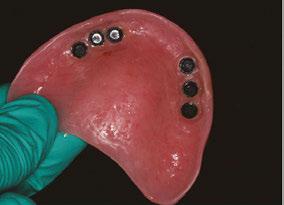

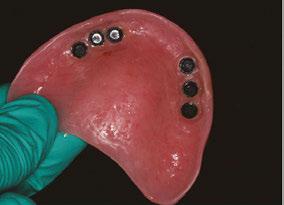

2 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS CASE REPORT LOCATOR FIXED™ Attachment System

Xavier

Saab explains a new way to deliver fixed full-arch restorations utilizing traditional locator abutments and a new fixed attachment system

PERSPECTIVE Telling the world about you

Media 6 TECHNIQUE The benefits of “sticky” bone grafting with PRP

Garg

Gustavo

new formulation to predictably regenerate bone ......................... 15

Full-arch treatment using reverse concave neck implants to preserve crestal bone plus virtual planning through final prosthetics Drs.

achieving osseocompression and improving bone density during implant procedures .................... 18 FAQs SPECIAL SECTION Why are Boyd implant surgery chairs, carts, and cabinetry better than the competition? ........................................................ 24

FIXED™ Changing the edentulous landscape with LOCATOR FIXED ........................................................ 25 8 12 COVER STORY Finding his true calling

Dr.

E.

PUBLISHER’S

Lisa Moler, Founder/CEO, MedMark

Drs. Arun K.

and

Mugnolo discuss a

TECHNIQUE

Filip Ambrosio and Gregori M. Kurtzman discuss

LOCATOR

Renee Knight writes about Dr. Alex Bachoura and his dental journey Cover image of Dr. Alex Bachoura courtesy of PuraGraft.

4 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS

EDUCATION Dental infections, part 2 — prophylaxis: help avoid antimicrobial resistance

their discussion of concepts surrounding antibiotic prophylaxis

dentistry 31

DEVELOPMENT Creating a memorable patient experience JoAn

discusses working

a team toward case acceptance...................................... 36 EVENT RECAP Panthera Dental 10th Anniversary Celebration Adrienne Good, National Account Manager for Implant Practice US, recaps Panthera’s memorable event .................................................. 38 PRACTICE MANAGEMENT When medical insurance covers implant services Rose Nierman and Courtney Snow discuss common scenarios for medical reimbursement for implants ........................................... 40 Connect. Be Seen. Grow. Succeed. | www.medmarkmedia.com READ the latest industry news and business WATCH DocTalk Dental video interviews with KOLs LEARN through live and archived webinars RECEIVE news and event updates in your inbox by registering for our eNewsletter CONNECT with us on social media www.implantpracticeus.com 26 CONTINUING EDUCATION Communicating periodontal issues across dental implant platforms Drs. Stuart Segelnick and Mea A. Weinberg review typical challenges and management at the dental implant-abutment connection *Paid subscribers can earn 4 continuing education credits per issue by passing the 2 CE article quizzes online at https://implantpracticeus.com/category/continuing-education/

CONTINUING

Wiyanna K. Bruck, PharmD, and Jessica Price continue

in

PRACTICE

Majors

as

BONE GRAFTING PUTTY OSTEOSTIMULATIVE

NovaBone® is 100% synthetic, fully resorbable, and bioactive. Disposable uni-dose cartridges simplify dispensing of the graft, especially in hard-to-reach areas, thus facilitating minimally invasive techniques like ridge preservation and crestal-approach sinus lifts.

▼ NovaBone’s unique cartridge delivery system makes it an ideal choice for crestal sinus elevation. The 2.8 mm cannula attached to the cartridge is designed to fit directly into osteotomy. The hydraulic pressure created when the putty is being delivered to the site safely lifts the Schneiderian membrane.

Case

Step 1: An osteotomy is prepared to less than 1 mm from the sinus floor.

Step 2: An osteotome is then used to gently fracture the bone at the apex of the osteotomy.

Step 3: The cannula from the cartridge tip can be pressed against the surface of the bone, and the putty can then be injected into the area, resulting in membrane elevation with hydraulic pressure from the putty.

Step 4: An implant may then be placed in the augmented area.

To order, call

or go to osteogenics.com/NovaBone

1.888.796.1923

image courtesy of Dr. Philip M. Walton

1. Kotsakis GA, Mazor Z. A Simplified Approach to the Minimally Invasive Antral Membrane Elevation Technique Utilizing a Viscoelastic Medium for Hydraulic Sinus Floor Elevation. Oral

2. Mazor Z, Ioannou A, Venkataraman N, Kotsakis G, Kher U. Minimally Invasive Crestal Approach Technique for Sinus Elevation Utilizing

Cartridge Delivery

3. Mazor Z, Ioannou A, Venkataraman N, Kotsakis G. A

Sinus

Minimally Invasive Transcrestal Sinus Augmentation with

Cartridge System1,2,3

Kotsak

Maxillofac Surg. 2015 Mar;19(1):97-101.

a

System. Implant Practice. 2013;6(4):20-24.

Minimally Invasive

Augmentation Technique using a Novel Bone Graft Delivery System. Int J Oral Implantol Clin Res 2013;4(2):78-82.

NovaBone®

Impl

Telling the world about you

Our worlds are so busy with our time consumed with improving clinically, professionally, and personally. We work hard and hopefully find the time to play hard. From my view as a publisher of four and soon-to-be five dental publications, I see and hear about so much inno vation going on in the dental community. Dentists are show ing patients that dental health means better overall health, and there are so many ways to add technology, expand clinical options, and create your own new protocols and inventions that can change the face of your specialties. My team at MedMark is always searching for your stories — for your journeys, your successes, and even your speed bumps along the way. Entrepreneur Gary Vaynerchuk said, “Regard less of what you are trying to accomplish, you’ve got to tell the world about it.” I wholeheartedly agree. And that’s what we at MedMark Media have been doing over the past 17 years. We’ve been telling the world about you.

Published by Publisher

Lisa Moler lmoler@medmarkmedia.com

Managing Editor

Mali Schantz-Feld, MA, CDE mali@medmarkmedia.com Tel: (727) 515-5118

Assistant Editor

Moler Founder/Publisher, MedMark Media

Elizabeth Romanek betty@medmarkmedia.com

National Account Manager Adrienne Good agood@medmarkmedia.com Tel: (623) 340-4373

All of the new advancements in dental specialty fields are amazing — artificial intelligence (AI), virtual reality, 3D printing, robotics, the field of dental sleep medi cine, braces and aligners that move teeth faster and more efficiently, and imaging in 2D and 3D that makes diagnostics more precise. Advances in endodontic materials such as bioceramics contribute significantly to that specialty’s incredible growth. Let’s not forget implants — according to iData Research, over 3 million dental implants are placed each year in the United States, and the U.S. market is expected to exceed $1.5 billion in 2027.

Here’s more good news. In this issue of Implant Practice US, our Cover Story features Dr. Alex Bachoura, who operates five offices in the greater Houston area. With that many practices, he and his colleagues don’t have time for supply-chain constraints, so with PuraGraft as his distributor, he knows that he will be able to access all of the supplies that he needs to perform oral surgery. Our CE, written by Drs. Stuart Segelnick and Mea Weinberg, titled “Communicating periodontal issues across dental implant platforms,” explores common problems and manage ment at the dental implant-abutment connection. Part 2 of the CE by Wiyanna Bruck and Jessica Price titled “Dental infections, part 2 — prophylaxis: help avoid antimicrobial resistance” provides an overview of the cautious use of antibiotics in the dental office.

Back to you — how can we help you tell the world about your innovations, techniques, and life-changing treatments? Our articles and advertisers show you what is possible and practice changing, and promises to help differentiate you from the rest. To change Gary Vaynerchuk’s quote just a bit: Regardless of what you are trying to accomplish, MedMark is here to help you tell the world about it.

To your best success,

Lisa

Moler

Founder/Publisher

MedMark

Media

Sales Assistant & Client Services Melissa Minnick melissa@medmarkmedia.com

Creative Director/Production Manager

Amanda Culver amanda@medmarkmedia.com

Marketing & Digital Strategy Amzi Koury amzi@medmarkmedia.com

eMedia Coordinator Michelle Britzius emedia@medmarkmedia.com

Social Media Manager April Gutierrez socialmedia@medmarkmedia.com

Digital Marketing Assistant Hana Kahn support@medmarkmedia.com

Website Support Eileen Kane webmaster@medmarkmedia.com

MedMark, LLC

15720 N. Greenway-Hayden Loop #9 Scottsdale, AZ 85260

Tel: (480) 621-8955 Toll-free: (866) 579-9496 www.medmarkmedia.com

www.implantpracticeus.com

Subscription Rate

1 year (4 issues) $149 https://implantpracticeus.com/subscribe/

6 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 PUBLISHER’S PERSPECTIVE

Lisa

How to submit an article to Implant Practice US

Implant Practice US is a peer-reviewed, quarterly publication containing articles by leading authors from around the world. Implant Practice US is designed to be read by specialists in Periodontics, Oral Surgery, and Prosthodontics.

Submitting articles

Implant Practice US requires original, unpublished article submissions on implant topics, multidisciplinary dentistry, clinical cases, practice man agement, technology, clinical updates, literature reviews, and continuing education.

Typically, clinical articles and case studies range between 1,500 and 2,400 words. Authors can include up to 15 illustrations. Manuscripts should be double-spaced, and all pages should be numbered. Implant Practice US reserves the right to edit articles for clarity and style as well as for the limitations of space available.

Articles are classified as either clinical, continuing education, tech nology, or research reports. Clinical articles and continuing education arti cles typically include case presentations, technique reports, or literature reviews on a clinical topic. Research reports state the problem and the objective, describe the materials and methods (so they can be duplicated and their validity judged), report the results accurately and concisely, pro vide discussion of the findings, and offer conclusions that can be drawn from the research. Under a separate heading, research reports provide a statement of the research’s clinical implications and relevance to implant dentistry. Clinical and continuing education articles include an abstract of up to 250 words. Continuing education articles also include three to four educational aims and objectives, a short “expected outcomes” para graph, and a 10-question, multiple-choice quiz with the correct answers indicated. Questions and answers should be in the order of appearance in the text, and verbatim. Product trade names cited in the text must be accompanied by a generic term and include the manufacturer, city, and country in parentheses.

Additional items to include:

• Include full name, academic degrees, and institutional affiliations and locations

• If presented as part of a meeting, please state the name, date, and location of the meeting

• Sources of support in the form of grants, equipment, products, or drugs must be disclosed

• Full contact details for the corresponding author must be included

• Short author bio

• Author headshot

Pictures/images

Illustrations should be clearly identified, numbered in sequential order, and accompanied by a caption. Digital images must be high resolution, 300 dpi minimum, and at least 90 mm wide. We can accept digital images in all image formats (preferring .tif or jpeg).

Tables

Ensure that each table is cited in the text. Number tables consecutively, and provide a brief title and caption (if appropriate) for each.

References

References must appear in the text as numbered superscripts (not foot notes) and should be listed at the end of the article in their order of appear

ance in the text. The majority of references should be less than 10 years old. Provide inclusive page numbers, volume and issue numbers, date of publication, and all authors’ names. References should be submitted in American Medical Association style. For example:

Journals: (Print)

White LW. Pearls from Dr. Larry White. Int J Orthod Milwaukee. 2016;27(1):7-8. (Online)

Author(s). Article title. Journal Name. Year; vol(issue#):inclusive pages. URL. Accessed [date].

Or in the case of a book: Pedetta F. New Straight Wire. Quintessence Publishing; 2017.

Website:

Author or name of organization if no author is listed. Title or name of the organization if no title is provided. Name of website. URL. Accessed Month Day, Year. Example of Date: Accessed June 12, 2011.

Author’s name: (Single) (Multiple) Doe JF Doe JF, Roe JP

Permissions

Written permission must be obtained by the author for material that has been published in copyrighted material; this includes tables, figures, pictures, and quoted text that exceeds 150 words. Signed release forms are required for photographs of identifiable persons.

Disclosure of financial interest

Authors must disclose any financial interest they (or family members) have in products mentioned in their articles. They must also disclose any developmental or research relationships with companies that manufacture products by signing a “Conflict of Interest Declaration” form after their article is accepted. Any commercial or financial interest will be acknowl edged in the article.

Manuscript review

All clinical and continuing education manuscripts are peer-reviewed and accepted, accepted with modification, or rejected at the discretion of the editorial review board. Authors are responsible for meeting review board requirements for final approval and publication of manuscripts.

Proofing

Page proofs will be supplied to authors for corrections and/or final sign off. Changes should be limited to those that are essential for correctness and clarity.

Articles should be submitted to:

Mali Schantz-Feld, managing editor, at mali@medmarkmedia.com

Reprints/Extra issues

If reprints or additional issues are desired, they must be ordered from the publisher when the page proofs are reviewed by the authors. The pub lisher does not stock reprints; however, back issues can be purchased.

7 implantpracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4 AUTHOR

GUIDELINES

Finding his true calling

Renee Knight writes about Dr. Alex Bachoura and his dental journey

Dr. Alex Bachoura is part of a successful oral and maxillofacial surgery group located in the greater Houston area. Here’s a look at his love for implant dentistry and how his group of five practices has over come the supply chain constraints that have impacted just about every industry over the past few years.

As a young high school student, Dr. Bachoura initially wanted to pursue a career as an aerospace engineer. Both his parents were engineers, so it just seemed natural to follow a similar path. He had an engineering mindset and an interest in the field, but the now oral surgeon dis covered he had a passion for dentistry at an unexpected place — the local jewelry store where he worked as a diamond setter.

His boss at the time, who didn’t have a background in dentistry, noticed Dr. Bachoura had a special talent. The high schooler not only loved working with his hands, but also clearly had an exceptional talent along with an impressive attention to detail. The jeweler suggested he look into dentistry as a career option rather than pursu ing aerospace engineering. So Dr. Bachoura did — and decided his boss was right — it became clear he was meant to take a different career path.

Dr. Bachoura found he loved the mechanical aspect of dentistry and knew he had the skills required to be suc cessful. “Believe it or not, there’s a lot of mechanics in the things we do. Like when we fix a jaw, it involves placing plates and screws. You have to understand the mechan ical aspects. It’s the same with placing dental implants,” Dr. Bachoura said. “For me, dentistry became a natural transition that allowed me to combine two things I really enjoy — mechanics and science. And there’s also the artistic element. You have to be good with your hands and know how to work with the materials. So, it all just came together.”

The road to oral surgery

Once he finished high school, Dr. Bachoura headed to the University of Southern California (USC) to earn his bachelor’s degree. He then went on to the USC School of Dentistry to obtain his DDS. That’s where Dr. Bachoura was first introduced to oral and maxillofacial surgery.

The school’s curriculum had a monthlong segment on oral surgery, and Dr. Bachoura was impressed with what he saw. He remembers watching the oral surgery team at USC repairing a jaw fracture using titanium plates and screws and knowing that was what he wanted to do. He

8 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 COVER STORY

Dr. Alex

practice by the numbers: 5 offices in the greater Houston area 7 full-time surgeons 60 employees 8,000 patients a year

Bachoura’s

picked it up quickly and decided his next step was to get the training he needed to practice oral surgery.

“I love the combination of the medical science and the mechanical/engineering aspect of what we do,” he said. “This is especially true when it comes to dental implants.”

After receiving his DDS in 2003, Dr. Bachoura moved on to the University of Texas Houston Medical School, graduating in 2007. He also completed an internship in General Surgery in Medicine and completed a 4-year oral and maxillofacial sur gery residency at the same institution as part of his training. He finished his residency in 2009 and has been a practicing oral surgeon ever since.

A look at his practice today

Dr. Bachoura is part of a five-office oral surgery group that has seven full-time surgeons and 60 employees. The practice serves more than 8,000 patients a year, both young and old, throughout the greater Houston area. The practices are full scope, with Dr. Bachoura and his colleagues performing wis dom teeth extractions, bone grafting procedures, facial trauma reconstructions, facial/dental tumor removal, and dental implant placement. His primary areas of interest include pathology, dentoalveolar surgery, dental implants, and maxillofacial trauma.

“I truly believe putting people out of pain and getting them back to productivity and normal, healthy lives are important,” Dr. Bachoura said. “I see patients from 2 years old all the way to 90-plus; at some point, every single human being will need some kind of oral surgical procedure. I feel like we are experts in the field of oral dental surgery.”

A focus on implants

Implant dentistry makes up 30% to 40% of the group’s busi ness, Dr. Bachoura said, and is one of the procedures he enjoys

performing most. He, of course, appreciates the mechanical aspect of surgically placing implants, as well as the challenges the cases present.

“For the most part, everything goes right, but when things go wrong, it can be pretty destructive. You really need to understand not just the surgical implant dentistry part, but how to salvage things when there’s an infection or another problem,” he said. “A lot of being an oral surgeon is having the capacity to deal with complex issues and bigger problems. I really enjoy the challenge of that.”

Over the years, Dr. Bachoura has seen a bit of a shift in implant dentistry, and one that’s for the better. General dentists who once restored only implants are now gaining the training and confi dence they need to start placing them, which has resulted in a boost for his practices.

“It means there’s a lot more awareness in the dental community of the benefit of implants,” he said. “They’re keeping more straightforward cases but sending the more complex cases they don’t have the skill set or knowledge to handle to oral surgeons, which has helped our business over the past few years.”

Overcoming supply chain issues

Like just about every business, dental practices have had to contend with supply chain constraints over the past few years, causing extra stress on doctors and their teams. That hasn’t been an issue for Dr. Bachoura and his colleagues, as the distributor they work with, PuraGraft, has done its part to ensure they have the products they need when they need them. PuraGraft carries a full line of grafting materials, pharmaceuticals, and all supplies necessary to perform oral surgery.

Get the details

To learn more about the PuraGraft products, including grafting materials, pharmaceuticals, and oral surgery sup plies, visit puragraft.com.

9 implantpracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4 COVER STORY

Dr. Alex Bachoura treating a patient

Over the 8 years Dr. Bachoura and his team have worked with PuraGraft, they’ve gotten to know the team pretty well, espe cially their rep Drew Bailey, who Dr. Bachoura describes as personable and someone who really cares about his clients’ success. If he knows a product the offices use regularly will be on back order, he gives them a heads-up, so they can prepare. Unlike other practitioners he’s talked with, Dr. Bachoura and his colleagues are never left scrambling to find drugs or other products they need for surgery.

I love the fact that we have a personal relationship with them and can always pick up the phone and talk with a familiar person. If you need something, they go out of their way to make sure you get it. That’s why

had a long-lasting relationship.”

“They can foresee issues with supply chain interruptions, so we can stock up,” Dr. Bachoura said. “They’ll also give us alternatives; if they can’t get a particular drug we’ve been using, they’ll suggest another that does the same thing.”

Bailey and the team at PuraGraft not only have helped Dr. Bachoura navigate through supply chain interruptions, serving as a “crucial partner,” but also have offered exceptional customer service. And it helps that the company is local to Houston.

“When we order something, we get it the next day,” Dr. Bachoura said. “I love the fact that we have a personal relation ship with them and can always pick up the phone and talk with a familiar person. If you need something, they go out of their way to make sure you get it. That’s why we’ve had a long-lasting relationship.”

Pricing is also competitive, Dr. Bachoura said. Any time they find drugs from another source that are a little cheaper, PuraGraft almost always price matches.

Dr. Bachoura also appreciates the breadth of products the company offers; he said that the practice gets most everything they use on their patients from PuraGraft, including local anesthetics, IV drugs and antibiotics, bone-grafting materials, and biologic membranes. This makes purchas ing inventory more convenient, especially when you know the company will do what

it takes to ensure that you have access to the products you need. Certain IV antibiotics and biologic-grafting materials are among the products that have been difficult to find lately, Dr. Bachoura said, but the team at PuraGraft have worked their magic to deliver them.

“They’re very reliable,” he said. “We have never had any issues. And reliability is crucial in a world full of supply constraints.”

Life outside of dentistry

When Dr. Bachoura isn’t in the operatory performing complex surgeries, he likes to stay active. He spends a lot of time skiing, hiking, and running, and has even completed the Houston marathon several times. One of his favorite ways to spend his free time is restoring old vehicles, which is no surprise considering his interest in all things mechanical. He also recently started racing cars, a hobby that has helped him become an even better clinician.

“I love mechanical things,” he said. “I feel like racing cars gives me the opportunity to sharpen my skills and stay focused during operations.” IP

10 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 COVER STORY

Dr. Alex Bachoura getting ready for a race

we’ve

When quality and selection is what matters most, PuraGraft is the first choice for your oral surgery practice’s needs. Pharmaceuticals | Grafting | Surgical Supplies UNMATCHED SELECTION UNPARALLELED SERVICE SCAN HERE to download our catalog and order today PERSONALIZED SERVICE Receive an Account Manager and personalized shopping cart FREE, FAST DELIVERY Items shipped same day— no freight charges ONE-STOP SHOPPING Multiple product options to suit your needs and preferences www.puragraft.com I 877-540-3258

LOCATOR FIXED ™ Attachment System

Dr. Xavier E. Saab explains a new way to deliver fixed full-arch restorations utilizing traditional LOCATOR® abutments and a new fixed attachment system

Introduction

The treatment of edentulous arches with full-arch fixed dental prosthetics is the oldest form of restorations placed on root form endosseous implants as presented by Brånemark, et al., in 1977.1 Many different tech niques and philosophies of fixed full-arch restorations have been developed and described in the past 55 years, which include, but are not limited to, different types of restorative materials, implant numbers and angulations, management of the restorative space, healing protocols, and analog or digital workflows. Even though some of these variations of full-arch therapy may be clinically simpler to perform than others, the final prostheses usually require final insertion with prosthetic screws that make the prosthetic material easier to fracture and create the necessity to utilize materials to seal screw access holes. These issues increase the maintenance times and the potential for prosthetic complications throughout the life of the prostheses.

A.

Figures 1A and 1B: 1A. Pre-extraction records. Patient presented with periodontal con cerns and extensive decay. 1B. Six LOCATOR® Implants (Zest Dental Solutions) were placed in strategic positions for a future fixed-prosthesis option

A.

Imagine being able to design and build an FP-3 fullarch (fixed-detachable hybrid) prosthesis, utilizing the current techniques used to make a simple denture or overdenture. Imagine being able to deliver these pros theses with a single snap and perform maintenance and repair appointments without having to drill screw access covers, removing screws, choosing new screws, torqu ing the prosthesis, and resealing it after the required procedure.

B. B.

Figures 2A and 2B: 2A. A conventional prosthesis was fabricated with the intention to convert to a fixed prosthesis. 2B. LOCATOR FIXED housings were attached using intraoral pickup method and CHAIRSIDE Attachment Processing Material (Zest Dental Solutions)

This article presents a new, innovative, and simple technique to deliver fixed full-arch prostheses utilizing a proven and well-

Xavier E. Saab, DDS, MS, completed his residency and specialty training in Prosthodontics at The University of Texas Houston Health Science Center Dental Branch, where he received his Master of Science degree. Dr. Saab also completed residency rotation in the MD Anderson Cancer Center Department of Head and Neck Surgery. He serves as a Clinical Assistant Professor in the graduate program of the UTHHSC Dental Branch Department of Restorative Dentistry. Dr. Saab is highly renowned for lecturing and teaching continuing education to dentists around the world in Implant Dentistry and Prosthodontics.

Dr. Saab hails from a family of dental specialists and grew up assisting his father, a Periodontist. He completed his doctorate at the University of Guayaquil, Ecuador, as the valedictorian of his class and Magna Cum Laude graduate. Dr. Saab is an active member of the American College of Prosthodontists. He also trained at the Dawson Center for Advanced Dental Study. He enjoys treating senior patients, doing complete makeovers, and most of all, giving his patients their smiles back. In his free time, Dr. Saab enjoys reading and sculpting. Dr. Saab’s practice, Houston Prosthodontic Specialists, is located in the Memorial area of Houston, Texas.

Disclosure: Dr. Xavier Saab is a speaker and key opinion leader for Zest Dental Solutions.

known removable overdenture abutment (Zest LOCATOR®), with a new FDA-approved fixed prosthetic attachment (LOCA TOR FIXED™ Attachment System), while using traditional den ture fabrication procedures.

Patient background

Our patient presented with maxillary and mandibular ter minal dentitions. Different options were discussed with him for the replacement of his teeth, which included complete dentures, implant-retained overdentures, and fixed prostheses on implants. After considering the costs and benefits of each alternative, the patient decided to have all his remaining teeth removed and replaced with maxillary and mandibular implant-retained overdentures.

Initial treatment plan

Interim dentures were fabricated prior to the extractions. All remaining teeth were removed, alveoloplasty performed, and implants placed at the same appointment. The interim dentures were inserted immediately after surgery with a tissue-condi tioning reline material. The patient was allowed to heal for 4 months, then the implants were successfully tested for osse ointegration. LOCATOR abutments were selected and torqued as

12 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 CASE REPORT

recommended by the manufacturer prior to beginning the definitive prosthetic treatment. Maxillary and man dibular implant-retained overdentures were fabricated using traditional indirect techniques. Both prostheses included metal frameworks for strength and long-term survival, and the LOCATOR housing was picked up chairside at the time of delivery.

Our patient reported to be very pleased with his new smile at the time of delivery. But after several adjustment appointments, he reported constant prob lems with his maxillary overdenture causing gagging and nausea after 1 or 2 hours of wearing his prosthesis. For over 1 year, he only wore his denture a few hours per day and at mealtimes, and he felt his quality of life had not improved since the time of extractions.

Revised treatment plan

We discussed the possibility of changing the type of prosthesis on the maxilla from removable to fixed. We explained to the patient the availability of a novel attachment system utilizing his existing LOCATOR abut ments, and he expressed excitement about the possibil ity. A new maxillary complete denture was fabricated around the LOCATOR abutment utilizing the indirect technique and conventional procedures. This time the denture did not have a metal-reinforcing framework since it will be converted into a fixed prosthesis.

Summary

Figures 3A and 3B: 3A. The prosthesis was trimmed and adjusted to eliminate the palate and flanges to convert into a fixed prosthesis. 3B. Processing inserts were replaced with LOCATOR FIXED (Zest Dental Solutions) inserts

For over 4 decades, the delivery of full-arch implant pros thetics has been a convoluted series of clinical and laboratory procedures that have made it challenging for the general prac titioner to make this therapy easily accessible to a great num ber of patients in need. The use of the traditional LOCATOR abutment with the LOCATOR FIXED Attachment System and

B. B. Implant Practice US 1 year $149 / 1 year digital only $79

Figures 4A and 4B: 4A. Before extractions and implants. 4B. After surgical procedures and prosthetic conversion into a fixed full-arch prosthesis

simple removable prosthetic techniques will make full-arch implant rehabilitation a more predictable and economical way to reach many underserved patients. It will allow more general dentists to grow personally and professionally. And it will make the hygiene, maintenance, and repair appointments simpler and more efficient for the general dental practice.

IP

REFERENCE

1. Brånemark PI, Hansson BO, Adell R, et al. Osseointegrated implants in the treatment of the edentulous jaw. Experience from a 10-year period. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Suppl.1977;16:1-132.

14 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 CASE REPORT

A. A. 3 REASONS TO SUBSCRIBE • 16 CE credits available per year • 1 subscription, 2 formats – print and digital • 4 high-quality, clinically focused issues per year 3 SIMPLE WAYS TO SUBSCRIBE • Visit www.implantpracticeus.com • Email subscriptions@medmarkmedia.com • Call 1-866-579-9496

The benefits of “sticky” bone grafting with PRP

Drs.

Arun K. Garg

and

Gustavo Mugnolo

discuss a new formulation to predictably regenerate bone

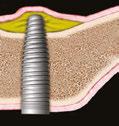

It has been more than 20 years since Drs. Arun Garg and Robert Marx developed the original formula for platelet-rich plasma (PRP), a vital wound-healing and regenerative agent that today is used by doctors in virtually every field of dentistry and medicine. In dentistry, the biologic assistance provided by PRP can facilitate bone healing under a range of implant-related procedures involving autogenous bone, allogeneic bone, syn thetic bone, and bone graft composites. This article describes a technique for using PRP in a unique formulation developed more recently by the authors to predictably regenerate bone and support implant placement without the need for autoge nous bone.

Sinus elevation bone grafting is a commonly performed pro cedure to increase maxillary bone height and width from the alveolar crest to the sinus floor for the support of one or more implants. Because of its osteogenic properties, autogenous bone remains the gold standard for this procedure and is the grafting material of choice for many surgeons.1,2 However, patients are often unwilling to accept this treatment method because of the added morbidity and potential complications associated with a second surgical procedure.

Bone allografts are obtained from human donors through tissue banks, accredited by the American Association of Tissue Banks, which screen, process, and store them under complete sterility.3,4 Allografts offer many advantages over autogenous bone grafts, including ready availability, avoidance of the need for a patient donor site, reduced time under anesthesia and in surgery, decreased blood loss, and fewer complications. Fresh allografts can be highly antigenic and generally are no longer used, but freezing or freeze-drying (lyophilizing) the bone sig nificantly reduces the antigenicity.5

The adjunctive use of liquid PRP to promote healing and increase bone volume has become a standard part of many

Arun K. Garg, DMD, completed his engineering and dental degrees at the University of Florida and completed his residency at the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital. Dr. Garg served as a full-time Professor of Surgery in the Division of Oral/Maxillofacial Surgery at the University Residency of Training Miami School of Medicine and as Director of the Program for 18 years.

Gustavo Mugnolo, DMD, PhD, MS, is a Board-certified oral surgeon who graduated first in his class from Cordoba National University in Argentina in 1990. In 1992, he completed a residency program in oral surgery at the Deutsche Clinic in Santiago, Chile. With a private practice limited to oral surgery and implant dentistry, he is regarded as a prominent oral surgeon in Argentina with a subspecialty in implants and related bone grafting

dental surgeons’ bone-grafting protocols, regardless of the graft ing material used. PRP contains growth factors that are believed to facilitate osteogenesis as well as cell adhesion molecules that enhance osteoconduction.6 A more recent application of PRP has been developed to exploit these benefits in a configuration that also takes advantage of the scaffolding properties of PRP’s fibrin component, which serves as a kind of intercellular high way that platelets creep along to form bone.

15 implantpracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4 TECHNIQUE

Figure 1: Full-thickness flap raised to gain access to the lateral wall of the sinus (Two-stage sinus augmentation procedure using Garg sticky bone™)

Figure 2: The sinus membrane is detached to proper height from the medial wall of the sinus (Two-stage sinus augmentation procedure using Garg sticky bone™)

TECHNIQUE

This newer configuration, known variously as “Garg sticky bone™,” “sticky bone,” or “gummy bone,” is made by collecting the patient’s whole blood in a glass test tube and spinning it for an abbreviated cycle (about 3-4 minutes) to allow the com ponents to separate but not to fully clot. The result is a middle layer of concentrated platelets, leukocytes, and fibrin that is then used to hydrate particulated bone, in this case freeze-dried bone allograft (FDBA). After about 15 minutes, clotting will be com plete, and the result is “sticky bone.”

Excellent handling is the hallmark of Garg sticky bone™. Because it has the consistency of gummy bear candy, it can be easily molded into a surgical site and adapted to the shape of the bony defect. Furthermore, it maintains its 3D shape even after closure. The potency of sticky bone is excellent, providing approximately 5 times the baseline concentration of growth fac tors contained in whole blood.

Figure 4: The sinus cavity is completely grafted with Garg sticky bone until the material is flush with the level of the original lateral wall (Two-stage sinus augmentation procedure using Garg sticky bone™)

Garg sticky bone™ can be used effectively in place of liq uid PRP in sinus grafting, as shown in Figures 1 to 5. In this procedure, the lateral sinus wall is exposed via a broad-based, full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap, extending from the maxil lary tuberosity to a releasing incision in the canine fossa region. The flap should extend superiorly to just below the infraorbital foramen to provide access to the lateral wall of the sinus. A large oval finishing bur or diamond bur is used to create an oval hole in the lateral cortical bone for access to the sinus membrane. To preserve its integrity, the sinus membrane is directly reflected in a series of stages, beginning at the sinus floor — superiorly, anteriorly, and posteriorly around the edges of the oval entry — until the sinus membrane is completely elevated posteriorly to the tuberosity. PRP sticky bone is intro duced into the sinus to augment the alveolar ridge height. Note its excellent handling qualities. A PRP membrane can be used to close the oval window of the lateral sinus wall once the graft is in place.6

PRP’s growth factors enable the healing action of the end osteal osteoblasts and marrow stem cells that migrate from the bony sinus walls, while the allogeneic bone particles are bound by fibrin, fibronectin, and vitronectin, facilitating cell migration and bone regeneration. Using sticky bone in place of a standard bone graft makes this procedure easier and more predictable with accelerated healing.

IP

REFERENCES

1. Marx RE, Garg AK. Bone structure, metabolism, and physiology: its impact on denta limplantology. Implant Dent. 1998;7(4):267-276.

2. Marx RE, Armentano L, Olavarria A, Samaniego J. rhBMP-2/ACS grafts versus autogenous cancellous marrow grafts in large vertical defects of the maxilla: An unsponsored randomized open-label clinical trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2013;28(5):e243-e251.

3. Malinin T, Temple HT. Comparison of frozen and freeze-dried particulate bone allografts. Cryobiology. 2007;55(2):167-170.

4. Malinin TI, Carpenter EM, Temple HT. Particulate bone allograft incorporation in regen eration of osseous defects; importance of particle sizes. Open Orthop J. 2007;1:19-24.

Figure 5: The flap is then repositioned in place by means of tension-free single interrupted sutures (Two-stage sinus augmentation procedure using Garg sticky bone™)

5. Sheikh Z, Hamdan N, Ikeda Y, et al. Natural graft tissues and synthetic biomaterials for periodontal and alveolar bone reconstructive applications: a review. Biomater Res. 2017;21:9.

6. Garg AK. Autologous Blood Concentrates. 2nd ed. Quintessence Publishing; 2021.

16 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4

Figure 3: The particulated FDBA graft material (OsteoLife Biomedical) is mixed with PRP to make Garg sticky bone (Two-stage sinus augmentation procedure using Garg sticky bone™)

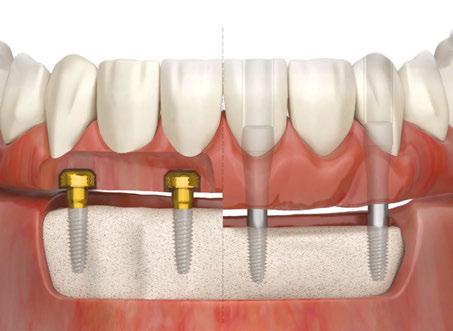

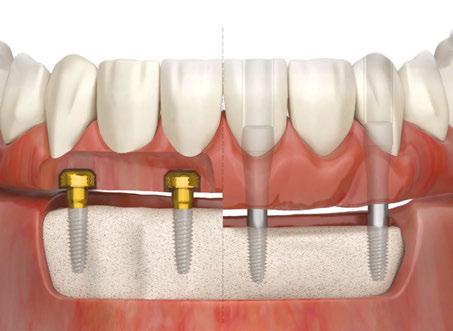

Full-arch treatment using reverse concave neck implants to preserve crestal bone plus virtual planning through final prosthetics

Drs.

Filip Ambrosio and Gregori M. Kurtzman

discuss achieving osseocompression and improving bone density during implant procedures

Introduction

Full-arch implant prosthetics, referred to as “All-on-X,” have become a common option for treating either the edentulous arch or an arch that will be edentulous due to a failing remaining dentition. The goal typically is immediate provisionalization of the implants to provide a stable prosthesis during the integration phase and to not require the patient to wear a removal denture that may have minimal retention. With that in mind, selection of the implant would ideally utilize a design with deep aggressive threads. This will help to achieve osseocompression, thereby improving bone density around the implants when utilized in the less dense bone found in the maxilla. When employed in

Filip Ambrosio, DDS, MS, grew up in Rochester, New York, and attended college at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Next, he attended dental school at the University of Detroit, Mercy, completing his DDS degree in 2010. Dr. Ambrosio completed his education by earning a Master’s degree and Periodontal Surgery Certificate in 2017. Dr. Ambrosio is Board-certified with the American Board of Periodontics. He is also a member of the American Academy of Periodontology, the American Dental Association, the Seventh District Dental Society, and the New York State Dental Association’s peer review and quality assurance council. He has multiple publications in peer-reviewed journals and received the award for the most downloaded publication in 2018-2019 from the journal Clinical Advances in Periodontology.

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS, MAGD, FPFA, FACD, FIADFE, DICOI, DADIA, DIDIA, is in private general dental practice in Silver Spring, Maryland. He is a former Assistant Clinical Professor at University of Maryland in the department of Restorative Dentistry and Endodontics and a former AAID Implant Maxi-Course assistant program director at Howard University College of Dentistry. Dr. Kurtzman has lectured internationally on the topics of restorative dentistry, endodontics and implant surgery and prosthetics, removable and fixed prosthetics, and periodontics. Dr. Kurtzman has published over 800 articles globally, several ebooks, and textbook chapters. He has earned Fellowship in the AGD, American College of Dentists (ACD), International Congress of Oral Implantology (ICOI), Pierre Fauchard, ADI, Mastership in the AGD and ICOI and Diplomat status in the ICOI, American Dental Implant Association (ADIA), and International Dental Implant Association (IDIA). Dr. Kurtzman is a consultant and evaluator for multiple dental companies. He has been honored to be included in the “Top Leaders in Continuing Education” by Dentistry Today annually since 2006. Dr. Kurtzman can be reached at jdr_kurtzman@maryland-implants.com.

Disclosure: Drs. Ambrosio and Kurtzman report no financial interest in any of the companies mentioned in this article.

B A

1A. 1B. 2.

Figures 1A–2: 1A. The DSST generate a gentle and progressive vertical and horizontal bone compaction that enhances initial implant stability regardless of the bone type or quality. This preserves the vascularity of the osteotomy while maintaining the peri-implant marginal bone and soft-tissue. 1B. The ULT implant RCN (A) preserves a ring of marginal bone reducing stress on the crestal cortical bone. This prevents undesired vascular compression while preserving the peri-implant soft tissue. The platform switching (B), has a smaller diameter implant-abutment connection. This leaves space for the biologic width that limits bone resorption while stabilizing the soft tissue that ensures excellent papillary esthetics. The micro-grooves (A) provide mechan ical stimulus that helps preserve marginal bone, increase the surface area of the implant and the ability of an implant to resist axial loads. 2. The ULT implant bone platform switching preserves a ring of marginal bone reducing stress on the crestal cortical bone. This prevents undesired vascular compres sion while preserving the peri-implant soft tissue

the more dense bone of the mandible, the aggressive threads of the implant create a self-tapping effect, making insertion into the osteotomy easier. It is commonly accepted and supported by the literature that when insertion torque of 35 Ncm or greater is achieved, implants can be immediately loaded with a provi sional hybrid prosthesis during the initial healing and osseointe gration phase of treatment.1

A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical success when higher insertion torque can be achieved showed no del eterious effect on implant survival rate or marginal bone loss.2 Overall implant survival has been reported up to 98% when the critical minimum insertion torque is achieved when immedi ately loading the provisional prosthetics.3,4 When four to eight implants are immediately loaded in the arch, and the accepted minimum insertion torque is achievable, a very high-clinical success has been reported.5,6

18 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 TECHNIQUE

TECHNIQUE

Selection of the implant

Selection of the implant may have an effect on the overall clinical success, especially when immediate loading is required. As previously mentioned, thread design on the implant has an effect on initial stability and is correlated to bone density at time of placement. The Ditron Ultimate Precision Implant (ULT™) is designed with double stressless sharp threads (DSST), which gen erate gentle progressive vertical and horizontal bone compaction upon insertion into the osteotomy (Figure 1A). This enhances initial implant stability regardless of the quality of bone present while preserving the bone vascularity.7

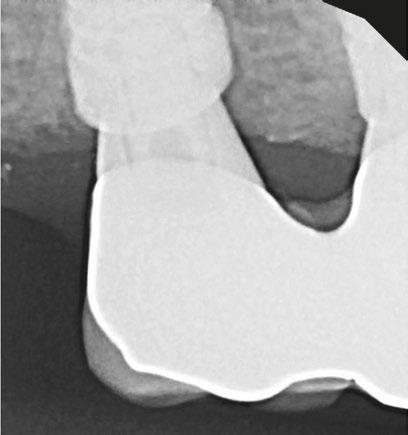

The authors recommend in lower density maxilla that the osteotomy diameter be underprepared so that the implant cre ates osseocompression, thereby densifying adjacent bone. For example, when the planned implant is 4.2 mm in diameter in Type III or IV bone (D3 or D4), the final drill diameter will be 3.2 mm drilled to the prescribed depth of the implant being placed. In Type I or II bone (D1 or D2), the final drill diameter utilized will be 3.8 mm In some instances, based on the bone type, the final drill may not go to depth. Additionally, the api cal aspect of the implant plays a factor on how the subsequent threads interact with the bone as the implant is threaded into the osteotomy. Helical apico-coronal slots (HACS) are present along

the length of the implant from below the micro-grooves to the apex. These slots help reduce resistance with the osseous walls of the osteotomy during insertion, allowing for collection of blood and bone chips from the osteotomy. These are drawn up, coating the surface of the implant, thereby creating a scaffold or matrix to accelerate osteoconduction during the initial phase of heal ing. The ULT implant has a cutting apex edge with progressive thread and sharp apical blades. Depending on the bone type and quality, this will act as a self-drilling, self-tapping feature to the implant design. The rounded apex itself improves ease of insertion, allowing mild directional refinement during the initial insertion of the implant into the osteotomy.

Maintenance of the crestal bone is important to the long-term success of the implant. Under function, the majority of loading occurs at the crestal portion of the implant.8 So, the thicker this bone is around the implant, the better the load handling and preservation of this critical bone over time. Frequently, the thin buccal crestal aspect of bone adjacent to the implant resorbs, which may contribute to soft tissue recession and resultant esthetic compromise. Given time, this may progress to peri-im plantitis and compromise the health of the implant. So, the thicker the bone is at crest on the buccal/palatal dimension and between implants or the implant and adjacent natural teeth, the easier it is to preserve that critical crestal bone long-term.9

With this in mind, the ULT implant is designed with a slight platform switch at bone level or slightly subcrestal upon place ment. But in addition, the reverse concave neck (RCN) provides what has been termed bone platform switching,10 a narrowed concave neck strategy to preserve additional marginal bone beyond the platform switch (Figure 1B). Enhanced bone volume at the cervical not only helps provide for greater resistance to bone resorption, but also reduces overall stress on the crestal cortex (Figure 2). Less titanium at the crest also helps to prevent removal of delicate marginal and subpapillary bone, providing the vascularity necessary for preservation of the peri-implant soft tissue.10

The combined strategy of platform switch and platform bone switch optimizes resistance to bone resorption, thereby stabiliz ing both hard and soft tissue elements.

Interestingly, the addition of microgrooves within the reverse concave neck provide a third bone preservation strategy, even

19 implantpracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4

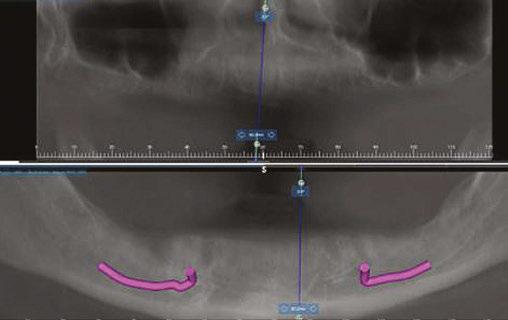

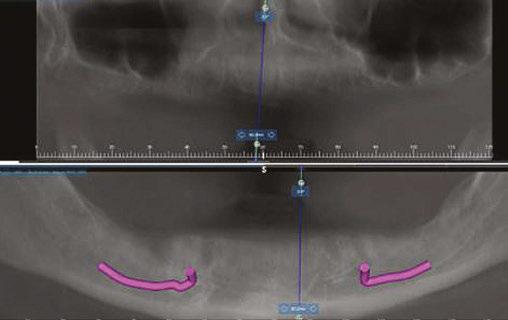

Figure 3: Preoperative panographic view of the maxillary and mandibular arches from the CBCT scan demonstrating anatomy that will impact implant placement

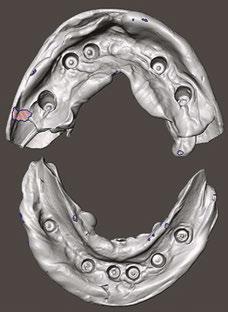

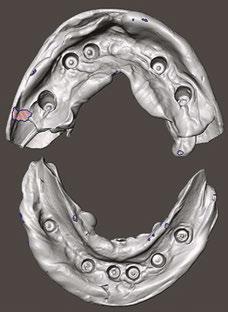

Figure 4: Extraoral scan of the full maxillary and man dibular dentures that patient presented with, which she was unable to wear due to a significant gag reflex

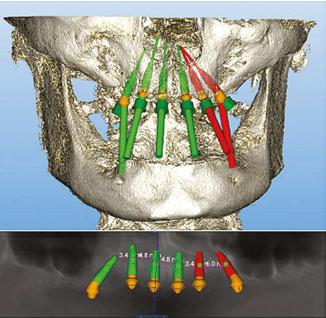

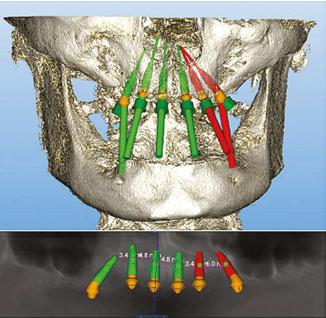

Figures 5A and 5B: Virtual planning of implant placement in the maxillary arch

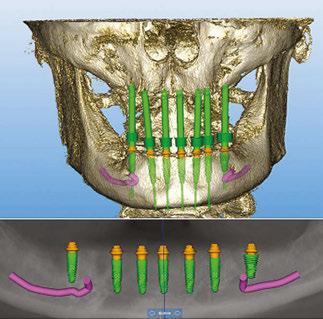

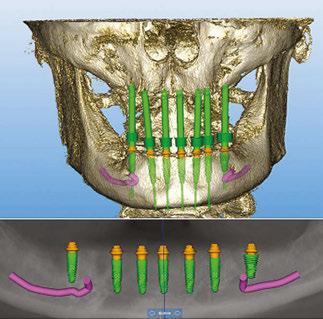

Figures 6A and 6B: Virtual planning of implant placement in the mandibular arch

TECHNIQUE

as it serves a favorable biome chanical purpose to increase implant surface area to reduce stress and promote maintenance of crestal bone under functional loading.11

Case report

A 49-year-old female patient presented with the chief complaint of her inabil ity to wear her current full maxillary and mandibular dentures due to a significant gagging reflex, indicating the dentures were delivered 2 years previously. She also expressed dissatisfaction with the current esthetics of the prosthesis and her smile. The patient’s general dentist had referred her for an implant consul tation. Her medical history was reviewed, and no significant health issues were disclosed.

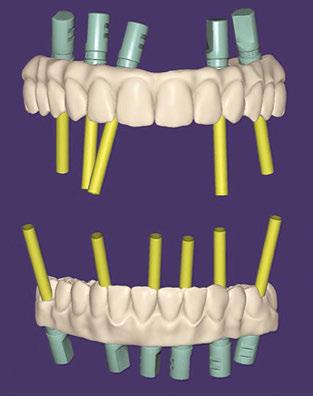

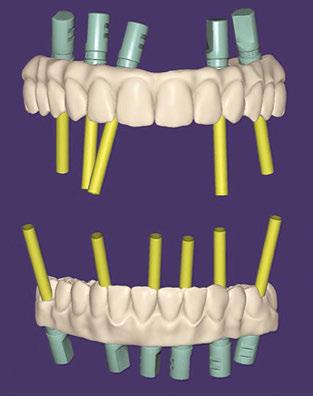

Figures 7–9: 7. A printed replica of the scanned maxillary denture was fabricated as a surgical guide and a channel created to aid in placement in the arch. 8. White caps were placed in the implants and an impression taken of each arch using the patient’s current full dentures to get a rough VDO of the patient which were then scanned. 9. The virtual arches with white caps on the arches based on the scan of the implant impressions of the white caps utilizing the patient’s dentures as custom impression trays

x 11.5 mm), No. 11 (3.75 x 11.5 mm), and No. 14 (3.75 x 11.5 mm) (Figure 5B).

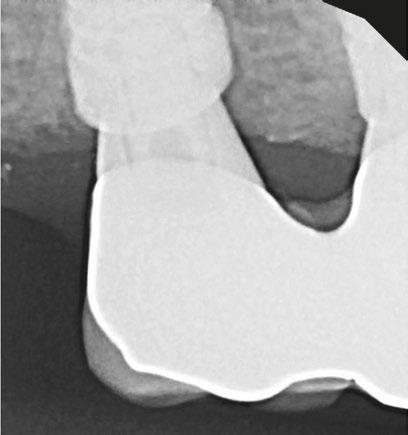

A CBCT scan was taken and panoramic views of the maxilla and mandible evaluated (Figure 3). Bilateral pneumatization of the maxillary sinus was noted, but adequate bone height was present between the premolars for implant placement to support an All-on-X hybrid prosthesis. In the mandibular arch, sufficient height was available between the mental foramen bilaterally and over the inferior alveolar nerve for implant placement to also sup port an All-on-X fixed hybrid prosthesis. A discussion was held with the patient that implants could be placed in both arches that would allow restoration with fixed prosthetics. Should sufficient insertion torque be achieved at the time of implant placement, a screw-retained hybrid provisional prosthesis would be placed and worn for several months during healing after which a final prosthesis would be fabricated. The patient would also be able to do a “trial-run” of the esthetics with the provisional prosthesis, with any requested modifications made when the final prosthesis was designed and fabricated. The treatment plan included six implants in each arch to support the planned hybrid prosthe ses. The patient was informed that reduction of the crestal bone would be required to achieve a flat ridge for adaptation of the prosthesis to the ridge as well as to provide adequate interarch space for the final prosthesis. The patient accepted the treatment plan. An intraoral scan of the arches was performed with Medit i500 (Medit Corp, Seoul, Korea) as well as the current complete arch maxillary and mandibular dentures (Figure 4). The patient was dismissed and scheduled for the surgical appointment.

The scans were imported into the planning software (Real GUIDE™, Allston, Massachusetts) and merged with the CBCT scan to allow implant planning. The maxillary arch was planned for implants at six sites, including tilted implants mesial to the maxillary sinus bilaterally to avoid the need for sinus augmen tation and allow more distal placement of the implant platform for a better anterior/posterior (A-P) spread (Figure 5A). ULT implants were planned as follows: No. 3 (3.75 x 11.5 mm), No. 6 (3.75 x 11.5 mm), No. 8 (3.75 x 11.5 mm), No. 9 (3.75

The mandibular arch was then planned for seven possi ble implants with the extra implant beyond what was initially planned should the short posterior implant on the patient’s left have less than ideal initial stability to provide better stability of the provisional prosthesis (Figure 6A). Ditron Dental ULT implants were planned as follows: No. 19 (3.75 x 11.5 mm), No. 20 (3.75 x 11.5 mm), No. 22 (3.75 x 11.5 mm), No. 24 (3.75 x 11.5 mm), No. 25 (3.75 x 11.5 mm), No. 27 (3.75 mm x 10 mm), and No. 30 (3.75 x 11.5 mm) (Figure 6B). A replica of the current dentures was fabricated to be used as a surgical guide, and the center of the replica was removed with a lab bur to create a zone for the implants to emerge to ensure they would be within the proper prosthetic zone (Figure 7).

The patient presented for surgery, and the consent form was reviewed and signed. IV sedation was initiated, and local anes thetic (2% Lidocaine with 1:100,000 epi) was administered in both arches. A crestal incision was made in the maxillary arch midcrest, and a full thickness flap was elevated to expose the buccal and palatal aspects of the ridge. Evaluation of the osseous ridge noted it was fairly flat, and reduction was deemed to be not necessary. The surgical guide was inserted and utilized to guide the location of the osteotomies. ULT implants were placed at the six planned sites: No. 3 (3.75 mm x 13 mm), No. 6 (3.75 mm x 10 mm), No. 8 (3.75 mm x 10 mm), No. 9 (3.75 mm x 11.5 mm), No. 11 (3.75 mm x 10 mm) and No. 14 (3.75 mm x 13 mm). Insertion torque of greater than 40 Ncm was achievable at five of the sites with site No. 10 being less than 30 Ncm and insuf ficient to support an immediate load. As sufficient A-P distance and adequate insertion torque was present utilizing the five other maxillary implants, it was decided to place an immediate provi sional hybrid prosthesis. Multi-unit abutments (MUAs) with the following angulations were placed: (No. 3 = 30 degrees, No. 6= 17 degrees, No. 8= 0 degrees, 11 = 17 degrees, and No. 14 = 30 degrees). The soft tissue was repositioned around the MUAs, and primary closure was achieved utilizing a continuous polylactic acid (PLA) suture.

20 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4

TECHNIQUE

Figures 11 and 12: 11. Articulated virtual maxillary and mandibular provisional prostheses. 12. Panoramic view following implant placement, MUA attachment, and insertion of the provisional hybrid prostheses to document the initial clinical presence

A scalpel was then utilized to create a crestal incision in the mandible from the approximate first molar on the right to the approximate first molar on the left, and a full thickness flap was ele vated with identification of the mental nerve and its foramen bilaterally. As with the maxillary arch, the mandibular crestal bone was fairly flat, and ridge reduction was not needed. The surgical guide was inserted in the mandible and utilized to guide the location of the osteotomies. ULT implants were placed at six sites as: No. 20 (3.75 mm x 10mm), No. 22 (3.75 mm x 10m m), No. 24 (3.75 mm x 11.5 mm), No. 25 (3.75 mm x11.5 mm), No. 27 (3.75 mm x 10 mm) and No. 30 (3.75 mm x 10 mm). Insertion torque of greater than 40 Ncm was achievable at all of the sites. As sufficient adequate insertion torque was present, placement of an immediate provisional hybrid prosthesis was planned. MUAs with the following angulations were placed (No. 20 = 30 degrees, No. 22 = 0 degrees, No. 24 = 0 degrees, No. 25 = 0 degrees, No 27 = 0 degrees, and No. 30 = 0 degrees). The soft tissue was repositioned around the MUAs, and white protective caps were placed onto the MUAs. Primary closure was achieved, and a continuous PLA suture placed. The patients’ dentures were relieved to seat over the white caps, and a reline impression was taken with the two arches in occlusion to allow use of the current vertical dimension of occlusion (VDO) in the planned fabrication of the provisional hybrid restorations. The patient was dismissed and scheduled for postoperative check and suture removal in 2 weeks.

13 and 14: 13.

esthetics. 14. The maxillary

(Figure 10). The planned provisional hybrid prostheses were evaluated for esthetics and alignment of the midline in relation to the arches. The flange area was modified to convert the virtual prosthesis from a denture to a hybrid prosthesis (Figure 11). The virtual designed provisional hybrid prostheses were printed uti lizing Flexcera™ Smile resin (Desktop Health™, Newport Beach, California) with the EnvisionOne 3D printer (Desktop Health™).

The patient returned 2 weeks later to evaluate healing and for suture removal. She indicated general comfort during the initial healing period. Sutures were removed with slight bleeding noted related to the sutures, and soft tissue did not present with any significant inflammation. The printed immediate provisional prostheses were placed onto each arch and secured with the prosthetic screws to fixate them to the MUAs, and a panoramic radiograph was taken to verify seating of the prostheses and document the implants in relation to the anatomy (Figure 12). The occlusion on the provisional prostheses was checked and minor adjustments made intraorally for a more even occlusion upon occluding the arches. The patient was shown her provi sional smile and indicated that she was satisfied with the initial esthetics (Figure 13).

The tissue side of the impressions was scanned (Figure 8). The scan data was imported into the software (exocad), while the patient remained in the treatment operatory (Figure 9). Utilizing the planned implant positions, the information was merged, and analogs were added to the virtual models of the white protective cap scans. The scans of the current dentures with modifications to increase the VDO were added as well as projections for emergence of the screw access channels through the virtual prosthesis. The model was then removed virtually

The patient presented after 12 months of integration to initi ate fabrication of the final prostheses. A discussion occurred with the patient regarding the unloaded implant at site No. 10, where she expressed her anxiety regarding further surgery and asked if the case could be finalized on just the five implants in the arch as it “seemed” to be working with the provisional restoration. As the provisional was stable on the five implants and taking into account the patient’s desire not to have additional surgery to uncover the buried implant, the plan was modified to fabricate the prosthesis on the currently loaded implants in the maxilla. During further discussions with the patient regarding the esthet

21 implantpracticeus.com Volume 15 Number 4

Figures

View of the provisional hybrid prostheses inserted intraorally demonstrating natural

arch following removal of the provisional hybrid prosthesis

Figure 10: Virtual design of the provisional hybrid prostheses with the projection of the prosthetic screw access channels.

Figures 15-17: 15. The mandibular arch following removal of the provisional hybrid prosthesis. 16. The maxillary arch following insertion of the final monolithic zirconia hybrid prosthesis and sealing of the prosthetic screw access holes. 17. The mandibular arch following insertion of the final monolithic zirconia hybrid prosthesis and sealing of the screw access holes

ics of the provisional pros theses, she expressed that she wanted larger anterior teeth and that the current tooth shape was too rounded for her. She requested that a more square-shaped anterior tooth be used. That informa tion was communicated with the lab to modify the final prostheses. The lab modified the design virturally in the software and then milled the final monolithic zirconia hybrid prostheses for both arches.

Figures 18 and 19: 18. The patient smiling with the full-arch monolithic zirconia hybrid prostheses on the maxillary and mandibular arches. 19. Panorex of the final monolithic zirconia hybrid prostheses on the maxillary and mandibular arches

The patient returned for insertion of the final monolithic zirconia hybrid prostheses. The provisional restorations were removed, and minimal superficial inflammation was noted at the crestal top, which was felt to be due to the patient’s home care (Figures 14 and 15). Additional instruction on homecare under the prostheses would be given the patient at the end of the appointment after the final prostheses were inserted. The final monolithis zirconia hybrid prostheses were inserted, and the MUA prosthetic screws were hand tightened. A piece of teflon tape was placed into each screw access hole, and the hole was sealed with flowable composite (Figures 16 and 17). Occlusion was checked, and no adjustments were noted to be needed. After the patient was shown her teeth in a mirror, she expressed that she was more satisfied with the smile on the final prostheses. She said her smile appeared the way she remembered before the loss of her natural dentition (Figure 18). A panoramic radiograph was taken to document the final clinical results and verify com plete seating of the prostheses on the implants in both arches (Figure 19).

Conclusion

Implant treatment of the edentulous arch has challenges. Ide ally the plan is to immediately load the implant, which requires achieving implant insertion torque that is at or greater than the accepted value of 35 Ncm. Selection of the implant being uti lized plays a factor in achieving that desired insertion torque. The selected implant needs to have an aggressive thread to better engage the bony walls of the osteotomy and create osseocom pression in less dense bone to improve bone-to-implant contact (BIC) and initial implant stability.7 The platform switch and bone platform switching achieved with the reverse concave neck of

the Ditron Dental Ultimate Precision Implant permits added bone volume at the crestal aspect which is critical to maintain marginal bone, vascularity, and support for the peri-implant soft tissue under functional loading.

IP

REFERENCES

1. Alfadda SA, Chvartszaid D, Tulbah HI, Finer Y. Immediate versus conventional load ing of mandibular implant-supported fixed prostheses in edentulous patients: 10-year report of a randomised controlled trial. Int J Oral Implantol (Berl). 2019;12(4):431-446.

2. Lemos CAA, Verri FR, de Oliveira Neto OB, et al. Clinical effect of the high insertion torque on dental implants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;126(4):490-496.

3. Eckert SE, Hueler G, Sandler N, Elkattah R, McNeil DC. Immediately Loaded Fixed Full-Arch Implant-Retained Prosthesis: Clinical Analysis When Using a Moderate Inser tion Torque. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2019;34(3):737-744.

4. Caramês JMM, Marques DNDS, Caramês GB, Francisco HCO, Vieira FA. Implant Survival in Immediately Loaded Full-Arch Rehabilitations Following an Anatomical Classification System — A Retrospective Study in 1200 Edentulous Jaws. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):5167.

5. Meloni SM, Tallarico M, Pisano M, Xhanari E, Canullo L. Immediate Loading of Fixed Complete Denture Prosthesis Supported by 4-8 Implants Placed Using Guided Surgery: A 5-Year Prospective Study on 66 Patients with 356 Implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2017;19(1):195-206.

6. Slutzkey GS, Cohen O, Chaushu L, et al. Immediate Maxillary Full-Arch Rehabilita tion of Periodontal Patients with Terminal Dentition Using Tilted Implants and Bone Augmentation: A 5-Year Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(10):2902.

7. Greenberg A, Romanos GE. Effect of primary stability on short vs. conventional Ditron implants, Dept. of Perio Stony Brook University Poster Presentation AO; 2022

8. Oliveira H, Brizuela Velasco A, Ríos-Santos JV, et al. Effect of Different Implant Designs on Strain and Stress Distribution under Non-Axial Loading: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4738.

9. Patil SM, Deshpande AS, Bhalerao RR, Metkari SB, Patil PM. A three-dimensional finite element analysis of the influence of varying implant crest module designs on the stress distribution to the bone. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2019;16(3):145-152.

10. Carinci F, Brunelli G, Danza M. Platform Switching and Bone Platform Switching. J Oral Implant. 2009;35(5):245-250.

11. Yalçın M, Kaya B, Laçin N, Arı E. Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis of the Effect of Endosteal Implants with Different Macro Designs on Stress Distribution in Different Bone Qualities. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2019;34(3):e43–e50.

22 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4

TECHNIQUE

RESORBABLE PERICARDIUM MEMBRANE

HIGHLY FLEXIBLE PROLONGED RESORPTION REMARKABLY

DURABLE

Exceptional Handling Properties

The OsteoFlex™ is easy to place and reposition. It has no memory and becomes highly flexible when hydrated. The membrane can adapt over grafted defect sites and be secured using our TriStar® screw system.

Can Be Stretched and Sutured

The OsteoFlex™ has a high tensile strength yielding a membrane with excellent resistance to suture pullout. Membrane can be used with our TriStar® tenting screw system to establish increased ridge height and width.

Naturally Extended Resorption

The OsteoFlex™ membrane achieves prolonged barrier function (over three months) while maintaining a naturally microporous collagen structure without any chemical crosslinkers ensuring optimal tissue integration.

www.impladentltd.com

Cross-Section View Surface View

Scan for references Remarkably Durable Highly Flexible

Call 800-526-9343 or Order Online at

FA Q SPECIAL SECTION

Why are Boyd implant surgery chairs, carts, and cabinetry better than the competition?

As the market leader for oral and dental implant surgery chairs and tables, Boyd equipment is best known for its ideal design combined with proven quality and reliability. The com pany’s dental surgery chairs are the industry standard for oral surgery, having been time tested over the company’s history during millions of surgical procedures.

To complement Boyd’s line of oral surgery chairs, the com pany offers a wide variety of mobile operatory carts designed to organize and store surgical items and devices. The carts are lightweight, easy to disinfect, and lockable with ergonomic handles to move between surgical suites.

Boyd designs and fabricates the widest variety of cabine try options to fit both the size, functionality, and style of your clinic. The cabinetry line of standard and custom designs sets the company apart from others in the dental implant industry. The company’s designers can adapt standard configurations or design cabinetry completely unique.

Do Boyd products meet all FDA and regulatory requirements?

Yes, our equipment meets all required regulatory standards for compliance. These include IEC 60601 safety standard for medical/dental devices, CSA for Canadian and CE for European.

As an internationally certified, ISO 13485:2016 company, Boyd goes through annual independent audits by British Stan dards Institute to assure it meets FDA, ISO, and all other regu latory standards.

What makes Boyd unique for Implant specialists?

We pride ourselves on providing our customers with the latest technology and innovations in Implant Dentistry. Our treatment chairs are ergonomically designed for dental implant procedures and can be configured specifically to the surgeons’ specifications.

Interested

Does Boyd offer financing options?

Boyd has a very competitive program for recent residency graduates and separating military members offering them signif icant product discounts or favorable payment terms.

What is the lead time for receiving Boyd equipment once I place an order?

Despite the volatility of today’s global supply chain, Boyd has been able to better manage its lead times because of the company’s U.S.-based factory and North American supply base. Boyd’s factory fabricates steel, plastic, upholstered wood, and many other components used in its products. The capability to directly manage much of the product content internally has allowed the company to maintain lead times to under 8 weeks.

Where can I see Boyd equipment on display?

Boyd attends industry trade shows to display and demon strate equipment. In addition to trade shows, Boyd has a prod uct showroom at our headquarters in Clearwater, Florida.

24 Implant Practice US Volume 15 Number 4 SPECIAL SECTION

in learning more? Please call our sales team at 727-471-5072, email us at sales@boydind.com for details, or scan the QR code.

LOCATOR FIXED

Changing the edentulous landscape with LOCATOR FIXED

Dr. John P. Poovey, DMD, DICOI, FADIA, FAAIP, is an early adopter of the LOCATOR FIXED full-arch solution from Zest Dental Solutions, the creator of the tried-and-true LOCATOR® attachment system. Having participated in the limited launch phases of the product rollout, Dr. Poovey has now focused on incorporating it into his daily patient treatment offerings.

Dr. Poovey addresses some key questions that clinicians are asking about the LOCATOR FIXED system from Zest.

How has LOCATOR FIXED changed your full arch patient offering?

Dr. Poovey: The biggest thing is that it creates a good middle ground where you have patients who have existing snap-ons, or you have patients who are interested in doing something fixed, but really are unable to come up with the price structure of a traditional fixed hybrid. So, what you are doing is capturing an untapped market of patients who really do not want to do a removable but cannot afford that pricier traditional fixed solu tion, or people who are in traditional snap-on overdentures and would like an alternative without starting from scratch.

Full-arch fixed prosthetics historically require more bone reduction and more complexity. In fact, prior to the introduc tion of LOCATOR FIXED, doctors who placed dental implants for overdentures with minimally invasive bone reduction were limited to overdentures, and if clinicians wanted to switch a patient from overdenture to fixed, they would essentially need to start all over again. LOCATOR FIXED has changed this paradigm.

When we talk with patients about snap-in overdentures, we explain to them that while it holds the denture in, it does not really change it from being a denture — it still walks and talks more like a denture. When we do a FIXED solution, they can experience a solution most like the teeth they used to have.

In fact, LOCATOR FIXED does not replace the traditional fixed hybrid screw-retained bridge; it is an additional offering that allows us to grow our practice by bringing in an untapped patient segment. At the end of the day, with LOCATOR FIXED, we are getting a higher level of case acceptance.

How can you use LOCATOR to build a full-arch practice and offer staged treatment planning?