7 minute read

Ini’s inspiration

Ini Archibong creates things that last – and his latest venture with the Pavilion of the African Diaspora may be his most ambitious legacy project yet

WORDS BY AIDAN IMANOVA

“The architectural scale is my most natural scale – it’s where I started, and even when I’m making an object, I’m thinking about the space around it,” says American designer Ini Archibong. After dropping out of business school aged 20 (“I was going to be a banker”), Archibong went on to complete a degree in Environmental Design from the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California – where he grew up, raised by Nigerian parents. From there, Archibong moved to Singapore to work at an architectural firm, later relocating to Switzerland where he received a master’s degree in luxury design and craftsmanship from École cantonale d’art de Lausanne. Archibong has lived in Switzerland ever since, and currently resides in the small and picturesque city of Neuchâtel. Between all this, he even dabbled in music – he’s someone who is clearly unafraid to move between boundaries, both literally and symbolically. Perhaps this ease comes with the designer’s intuitive nature, which he pours into the work itself.

The Kadamba Gate in red oak as part of Connected exhibition for the London Design Museum.

The Kadamba Gate in red oak as part of Connected exhibition for the London Design Museum.

Since establishing his own practice, Design by INI, moving across scales has been a comfortable feat for Archibong, who is best known for his ethereal furnishings and objects that are likened to works of art, most of which are handcrafted – something the designer believes carries special value that is both tangible and intangible. Archibong has now expanded upon the comforts of scale, creating installations for galleries, including a permanent collection for the Dallas Museum. More shows are in the pipeline – including for New York’s Friedman Benda gallery as well as a chair for Knoll.

But regardless of scale, what unites Archibong’s works are universal themes such as emotion, spirituality and mythology – all told from a perspective that is rooted in his own cultural heritage of West Africa as well as personal experiences, philosophies around the way we exist in the world – and how we connect to the unknown. Growing up in a religious household, Archibong spent a lot of time reading as an adolescent, poring over religious texts, myths and fantasy stories. This otherworldly quality permeates across his work, being present in the way he controls material, light and form. Archibong works with brands that uphold similar values around craftsmanship, luxury and storytelling. His twopart collection for Sé, Below the Heavens, is created to exist as if on the verge of heaven and earth. The celestial spirit of the collection is embodied in its sensual curves, monumental forms and iridescent colours. His Galop watch for Hermès encapsules similar qualities; while it is smaller in size, the thinking behind the luxury object was expansive.

“The design of the Hermès watch was based on the reflections that the rest of the environment would place on the watch. That’s why it doesn’t have any edges and is completely fluid, so that it can absorb the environment around it more naturally,” he says.

This year is an important one for Archibong, who is on the verge of realising what is perhaps his most ambitious (and largest) project to date – the Pavilion of the African Diaspora for the London Design Biennale 2021 at Somerset House. Talks around the pavilion first began in 2019 with the biennial’s curator, British artist and stage designer, Es Devlin; however, due to necessary funding and later the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, plans were pushed back.

“I didn’t know what was going to happen when I started these projects. It is timely that a lot of these projects are launching now but it isn’t that I’m being very smart; it’s really coincidence that I already had been working on these things. This moment that the world is going through is waking people up to some of the topics

Photography by David Cleveland.

that I always felt should be highlighted,” says Archibong. He does, however, note that the rise of international protests for racial justice, beginning with the Black Lives Matters movement in the US, awakened a sense of responsibility towards his community, making him want to reach back after a long absence.

“Nobody asked me before why I left America in 2012, and never went back, and I didn’t feel the need to stir up any controversy because I had escaped, and I feel safe,” he says. “I think the biggest thing about the Black Lives Matter movement is that it was kind of the first time since I left America where I started to feel a responsibility towards the people that I left behind.

“I think that is probably why I became more vocal – because if it was just about me, I [wouldn’t] have anything to say. I created a situation for myself where I was safe from it; but thinking about the people that I have a responsibility to use my voice for – that made it imperative that I speak up.”

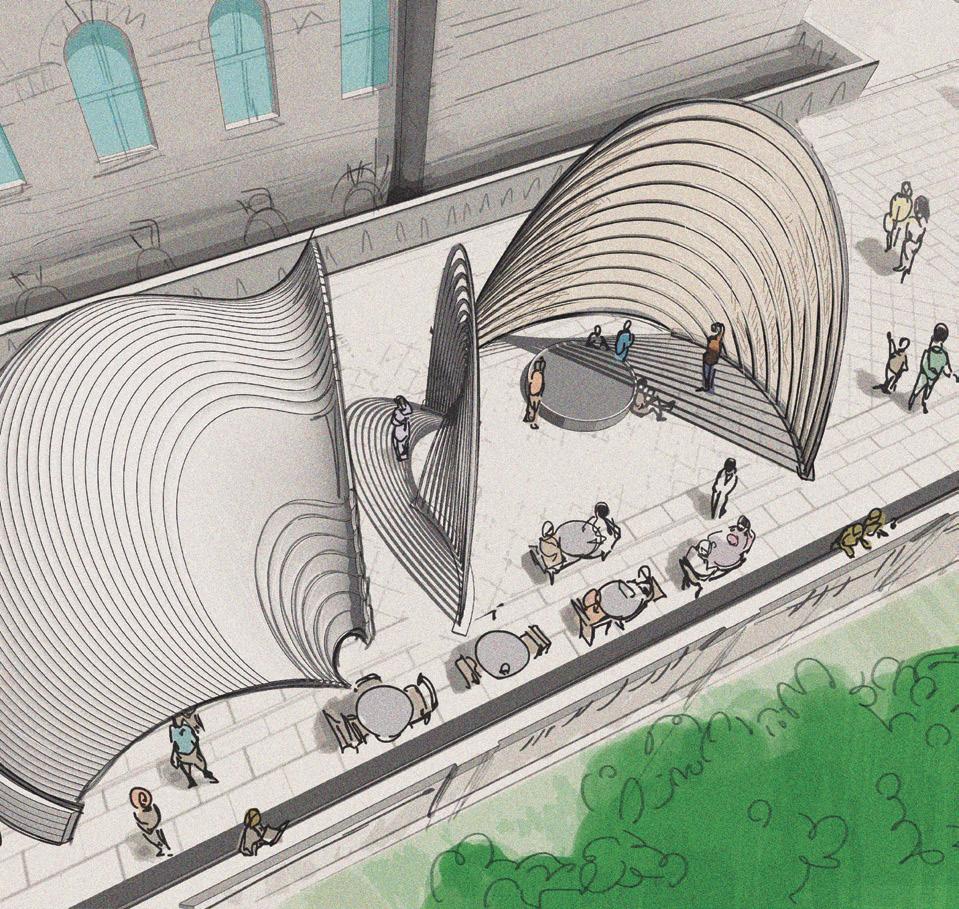

The Pavilion of the African Diaspora will become a place for collaboration, education and dialogue, bringing together people from across the diaspora and highlighting their contributions. The pavilion has been developed with Archibong’s collective studio, LMNO Creative, and comprises three architectural follies “that together represent a trumpet blast going out and the voice of the diaspora carrying a power that resonates and helps guide us into the future,” Archibong explains.

The three sculptural forms include a shell, wave and sail, alluding to a myriad of references, from the transatlantic slave trade to myths shared across the African continent. The Shell, for example, is inspired by cowries and conches that were a form of trade. “It also signifies that there has been a disconnect between the contributions and the economic benefits and distribution of resources when it comes to the people of the African diaspora. So, it really became about having a voice and the ability to finally fit into the economic system where our voices have been so powerful in generating so much wealth worldwide,” he says.

Archibong's collection for furniture brand, Sé.

Photography by Mel Bles.

The Pavilion is planned to comprise a flexible design to allow it to be dismantled and rebuilt in another location, following the biennial. Overseeing the construction is Zena Howard, principal architect and managing partner at Perkins&Will. Preliminary talks are already underway with the Smithsonian Museum for the Pavilion to be added to its permanent collection.

It was also a chance for Archibong to return to his architectural roots. “The design of the three structures was probably one of the most natural and intuitive processes that I have worked on in a while,” he confides. “I don't want to spoil the magic by telling you how quickly it happened, but it wasn’t as labour-intensive as designing a chair, for example. Because for me, [the archiectural scale] is where my creativity was born, so it comes pretty naturally.”

The Pavilion of the African Diaspora is also the first project under the Archibong Heritage Foundation – set up by Ini and his two brothers, who each work across different sectors, ranging from investment banking to creative management. The Foundation’s aim is to create cultural and racial inclusion within the creative sphere by bringing together their creative and financial prowess. “Our goal is to have an economic impact in the creative space for our people,” explains Archibong.

The designer has also recently introduced tech consulting as part of his studio, a strategy to diversify his creative offering. “What I hope designers realise is that we actually have a place in every space. If you are a designer and you train yourself to think and operate in a certain way, then you add value to every industry.” id

A render of the Pavilion of the African Diaspora by LMNO Creative.