Vagabonds

YETI Ambassador Rafa Ortiz

YETI Ambassador Rafa Ortiz

YETI Ambassador Rafa Ortiz

YETI Ambassador Rafa Ortiz

WHEN

Taking the ultralight platform we’ve built with our Exos/Eja thru-hiking backpacks and going even lighter, the new Exos/Eja Pro relies on featherweight NanoFly™ fabric and an essentialist approach to features to deliver a remarkably comfortable, durable and capable pack that weighs in just under one kilogram.

AVAILABLE AT:

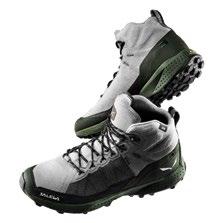

PEDROC PRO MID POWERTEX BOOT

PEDROC PRO MID POWERTEX BOOT

On or off duty, Monika of Squamish Search & Rescue is drawn to the mountain. She knows she needs the right gear, knowledge, and community to get the most from the outdoors.

ON THE COVER "When I first started as an adventure photographer, I thought it was all about the action—those big, explosive moments. As I've progressed, I've begun to realize that yes, the action is important, but shots of the people, culture, and those short in-between moments also truly strike a chord with me and stand the test of time. Here, rider Uwe Homm soaks in the moment between action shots as we wait for the sun to drop a few more degrees."

BEN HAGGAR

BEN HAGGAR

P.45

PUBLISHERS

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

EDITOR

Feet Banks feetbanks@mountainlifemedia.ca

CREATIVE & PRODUCTION DIRECTOR, DESIGNER

Amélie Légaré amelie@mountainlifemedia.ca

MANAGING EDITOR

Susan Butler susan@mountainlifemedia.ca

WEB EDITOR

Ned Morgan ned@mountainlifemedia.ca

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING, DIGITAL & SOCIAL

Sarah Bulford sarah@mountainlifemedia.ca

FINANCIAL CONTROLLER

Krista Currie krista@mountainlifemedia.ca

CONTRIBUTORS

Simon Bedford, Cami Benchley, Agathe Bernard, Kieran Brownie, Thomas Burden, Peter Chrzanowski, Dave Clarke, Joanna Croston, Nikkey Dawn, Diamond Head Development, Lindsay Donovan, Andrew Findlay, Ben Haggar, Megan Hocken-Bennett, Brian Hockenstein, John Hooper, Lani Imre, Justa Jeskova, Yan Kaczynski, Asta Kovanen, Carmen Kuntz, Todd Lawson, Riley Leboe, Ace MacKay-Smith, Stu MacKay-Smith, Jarred Martin, Jimmy Martinello, Mason Mashon, Greg Maurer, Wade McKoy, Susan Musgrave, Alana Paterson, Bart Ross, Steve Shannon, Kaili Smith, Tempei Takeuchi, Brett Tippie, America Tordoya, Linda Truman, Jon Turk, Sandy Ward, Steve Woods, Kaz Yamamura.

SALES & MARKETING

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

Published by Mountain Life Media, Copyright ©2023. All rights reserved. Publications Mail Agreement Number 40026703.

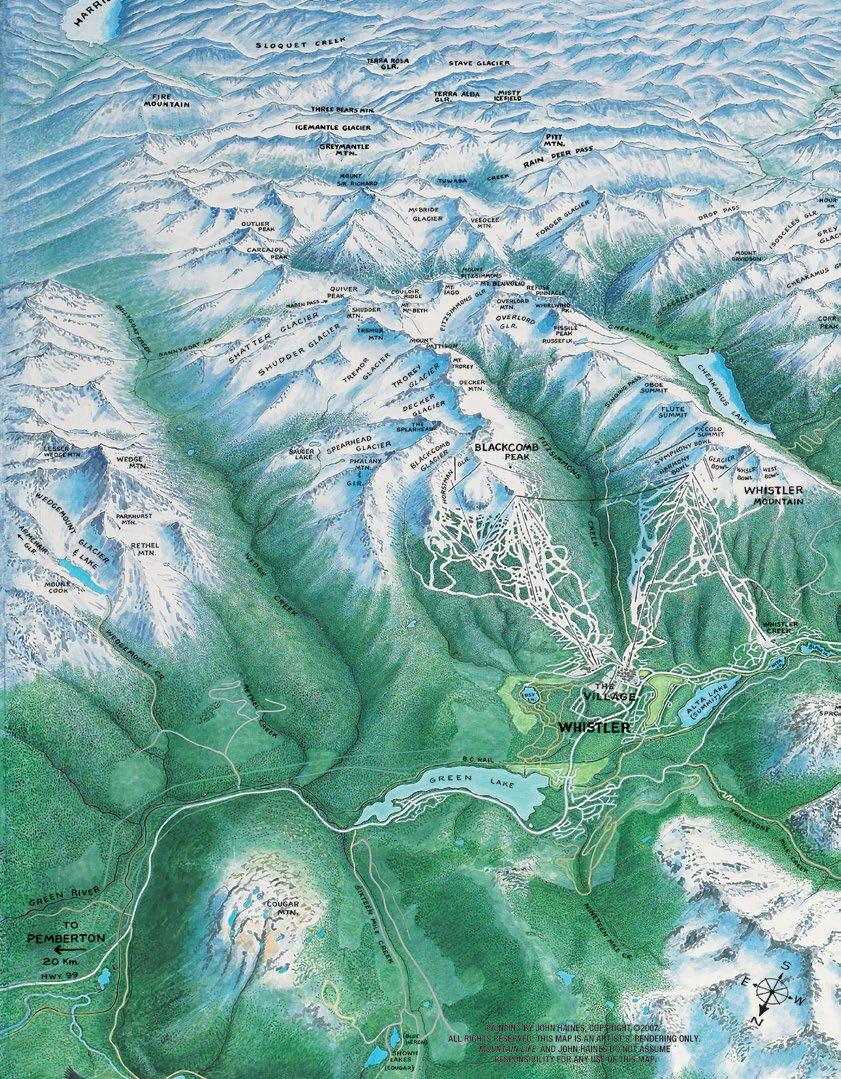

Tel: 604 815 1900. To send feedback or for contributors guidelines email feet@mountainlifemedia.ca. Mountain Life Coast Mountains is published every February, June and November and circulated throughout Whistler and the Sea to Sky corridor from Pemberton to Vancouver. Reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. Views expressed herein are those of the author exclusively. To learn more about Mountain Life visit mountainlifemedia.ca. To distribute Mountain Life in your store please call 604 815 1900.

Mountain Life is printed on paper that is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is an international, membership-based, non-profit organization that supports environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the world’s forests. Mountain Life is PrintReleaf certified. It measures paper consumption over time automatically reforested at planting sites in Canada.

“The decision to flee came suddenly. Or maybe not. Maybe I’d planned it all along—subconsciously waiting for the right moment.” – Hunter S. Thompson, 1971

Not that long ago, most of us were living in caves and getting out to roam around was the only way we were gonna make it. Even after the introduction of agriculture—when we began clustering together for stability, safety, and community—much of human history was made by those willing push the edge and peek around the corners of life.

Times have changed. Mindless convenience is king, spoon-fed comfort is expected (or you’ll hear about in the comments section), and we’re being beaten into idle submission by the dark spectre of liability. Stagnation is imminent…

But not for everyone. There are still those who step over the line. Those who will seize that single tendril of possibility when it twists up from our subconscious and pulls us towards the door, the road, the anywhere-but-here.

They say narrow minds dislike open spaces—all that room for error, or for something difficult to sneak in from any side. But this magazine is for those who see open spaces as open opportunities—to just go, be, do.

The distance isn’t important, nor the duration, the regions, the reasons…It doesn’t matter if you’re alone with a canoe or sardine-packed into the backseat of a ’79 Bronco with two friends and three dogs—the decision is the magic: that single instant when your whole body knows it’s time to pull the chute, hitch a ride on the wind, and carpe diem yourself to parts unknown.

This issue is about that moment of commitment, and those who make it. It’s for all the idle roamers and the hard-driving trailblazers; the artists, the explorers, and the rockers of the boat. It’s for anyone who’s ever felt the pull to disrupt stagnation with abrupt relocation: the nomads, the wanderers…the vagabonds. –Feet Banks

The all-day wind blowing off ice-filled Disko Bay was chilly, but it developed an extra bite as the sun dipped behind the fog bank hanging a few miles offshore. Let’s be honest, it’s freezing, but sometimes I can’t help myself: “You up for one more, Ryan?”

I feel a little brazen asking the question after the insane images we’ve already captured on the rough trails above the Ilulissat Icefjord in Western Greenland. Perfect light, the fjord spilling over with colossal icebergs backlit by a slow Arctic

sunset lasting for hours. It’s nearly 10:00 p.m. but Ryan stiffly obliges, and I point out the shot I have in mind.

Separated by hundreds of metres, we communicate via inReach satellite devices as he moves into position. And, as I’d hoped, the sun unexpectedly breaks free of the fog bank and lights up the sky for a few brief moments. Ryan scrambles to ride the slab a few times in different directions as the light dwindles, but the riding images seem contrived—a little too cute. As he shifts the bike for one last shivering descent, I click the shutter and that’s the moment.

There are times, many times, where my ideas don’t pan out. Other times I get lucky… but we never succeed if we don’t get out there and try. Go.

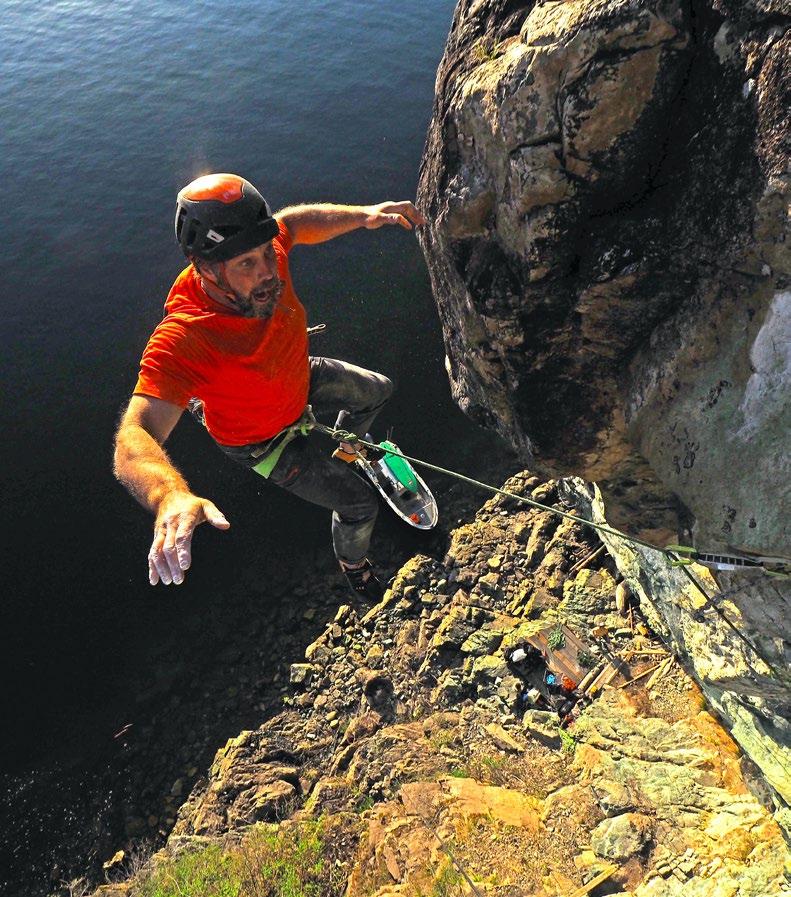

It is all about the beast of fear.

Cauterizing terror that strips all dross away and leaves you vivid. Where each inhalation and out-breath is a miracle. Texture of rock between left thumb and two fingers, the pinch, exquisite in its lucidity. Wire six feet below you, a so-so flared placement, shallow cam very far below that. Fifteen metres to the deck, up-pointing shards of slate. Test the crimps up and right, smooth the rock with tips. Gamble on gear at the next break. There might be a slot but you can’t be sure. Poor foothold, kneeheight, a coin-width overlap, raise your toes gently, a last intake of oxygen and cast your weight and now you can’t reverse and you can’t get off, no one can help you, no one can drop a rope, you are on lead and your mind is one hundred per cent gripped and your body is incandescent with life.

And therein lies the beauty.

–Sarah-Jane DobnerCelebrating 25 years of honouring the spirit of the land by maintaining public and private spaces on the unceeded territory of the Lil̓wat7úl and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh nations.

We make beer in a small town with incredible wildlife

Tasting room and patio open every day

Beer-To-Go Sales

Serving pizza, charcuterie, snacks

Kid friendly and pet friendly

lillooetbeer.ca l 236-417-1133

104 Main St., downtown Lillooet

In the ‘90s, I was cruising around British Columbia like a vagabond, just camping anywhere I could and searching for epic steep lines to pioneer on mountain bikes. I found some in the majestic Farwell Canyon, east of Williams Lake, and did a first descent there while filming for the freeride movie Kranked 2

I didn’t smooth out the outrun or do anything other than hike-a-bike up the side of the slope and drop in. Then I hiked it several more times and dropped a bunch of different lines down it. I was super happy to get some legitimate carves in a new zone, that’s what I was really into doing in those days…and I still am!

It’s always nerve wracking to do something for the first time, but I knew I could do it. I was at the top, ready to go, and I saw Kranked filmmaker Christian Begin hiking around at the bottom in search of the perfect camera angle. But I saw a large black creature following him, stalking him, and getting closer and closer while Christian fiddled with his tripod.

I yelled on the radio, “Christian! There’s a bear chasing you! Go for the river! Go for the river!” He proceeded to sprint to the river and jump right in. The black creature chased him as far as the beach, then stopped. Looking down, I then saw Christian climb out of the water and go pet the creature on its head.

“Tippie, you frickin’ idiot,” the radio crackled,”…that is my dog!”

Oops, sorry buddy! I was honestly trying to save his life. Strange things can happen out on the fringes of civilization. That’s why we go!

Ethnobotanist Leigh Joseph discusses her first book, Held by the Land

Leigh Joseph has collected her fair share of books, which as an ethnobotanist is not surprising. She has books that tell the Latin names of plants, books on their scientific order, books on where to find them and books on ways to use them. But a few years ago, Joseph noticed something critical—too few included relationship building with plants from an Indigenous perspective.

As an Indigenous woman, mother, and entrepreneur whose

business relies on plants, that relationship is something Leigh thinks about, a lot. So, when a publisher approached her to write her own book, she knew it was an opportunity to help fill that gap.

Held by the Land is an invitation to develop a deeper relationship with plants and become a respectful and mindful harvester. On a sunny, spring afternoon, I reach Joseph via video chat at her Sḵwálwen Botanicals office in Squamish. The first thing I notice are the rows and rows of grey bins behind her labeled with different plant names. It feels fitting that plants are present for our conversation.

Mountain Life: The structure of this book is unique. You share advice on relationship building and principals for respectful harvesting through a personal narrative before moving onto plant identification. Was this an intentional way of helping people learn reciprocity before giving them harvesting information?

Leigh Joseph: I appreciate hearing that. Stories are the way I learned, so as opposed to telling the reader what to do, I wanted to always come back to a place of sharing stories in hopes that people will pick up the intended messages and takeaways. I believe there’s a large percentage of people who have an interest [in harvesting] but have not considered or learned reciprocity yet.

In my teachings, we think about a plant as a relative, and the relationship is one you would have with a respected relative. So, you have to ask yourself, “What are the pillars of that relationship?” And the answer is usually respect and reciprocity.

ML: It’s like the expression, “you don’t know what you don’t know.” Did you have to put a lot of trust in the book’s readers, knowing that many of them would not have the same cultural teachings as you?

Joseph: It was a big consideration. One of my research mentors once stated the obvious to me, that whenever you publish something you lose control of where it ends up. So, it’s a worthwhile exercise to ask myself, “Okay, if this landed in the hands of somebody who has the opposite approach or is looking for an opportunity to exploit, how do you write around that?”

If there’s ever a question around culturally-sensitive material, my answer is don’t include it because that information should be only for community use. I didn’t put anyone’s knowledge in the book without their permission.

That’s why it also always made sense for me to bring it back to my personal story and keep it through a Skwxwú7mesh lens, even though the plants themselves span much farther across the diversity of territories. And then, I have a lot of reminders throughout the book that these plants can be grown.

ML: We don’t necessarily think to plant species such as camas and stinging nettle in our edible gardens because we are replicating what we see in the grocery store. Do you find the experience of gardening and harvesting very different?

Joseph: Definitely. I feel like the experience itself, from a cultural standpoint of going out onto the land and reconnecting or surveying different areas to see where we might harvest next or check on how the plants are doing. That’s a whole process in itself that I really treasure and cherish. But I remember realizing I could plant Springbank clover, rice, or bulb species and started putting them in my beds, it brought me so much joy to see those plants coming up. There’s definitely a different feel to each. I really love both.

ML: What made now the time to write Held by the Land?

Joseph: I was about halfway through my PhD and I had already heard from a lot of people in my community and other Indigenous communities that they really wanted resources to learn from. Even though the book is written from a Skwxwú7mesh perspective, my hope was that other Indigenous communities could pick it up and see themselves in it.

I’ve had teachers in Skwxwú7mesh, my Auntie Joy and an elder, Ronald Newman, who taught me not only about plant medicines but also responsibility and that when I go out and gather this knowledge through my academic learning, I also need to come home and to share it within community. That was a big part of the motivation for this book.

ML: What will you be harvesting when this issue comes out in May?

Joseph:Let’s see… in May there will probably still be some conifer tips, maybe even salmon berries. Thimble berry shoots might even still be around!

Learn more about Leigh Joseph’s work and her book Held by the Land at leighjoseph.com

Yeah, that’s pretty good, but one time in Chamonix in 1977, Peter Chrzanowski and his buddy ripped the spoke off a bicycle tire and stuck it into a pay phone to activate the coin sensor mechanism into thinking it was getting money. Then he jammed the end of a spoon into the one-franc slot and called the K2 factory in Washington State, U.S., and convinced them to courier two sets of their newest speed skis direct to France.

“I guess they were impressed by the long-distance call,” Chrzanowski says. “Before I knew it, we had two custom-made pairs of downhill skis with the name of U.S. Olympian Phil Mahre on them.”

Even better, Chrzanowski was in the midst of three months of skiing for free in Switzerland using a fake press pass he’d made from Letraset, a sheet of official-looking black letters one could rub/transfer onto anything.

“I made myself a journalist for the official Penthouse Guide to Après Skiing,” Chrzanowski recalls, “and booked an appointment with the CEO of the ski resort. I think he knew what I was up to, but my story amused him, and he gave us the passes and had his groomers make a special speed skiing run for us between Val D’Isere and Tignes.”

And this is essentially how Chrzanowski has lived life—part vagabond, part romantic artist, all dirtbag, and constantly pushing up against the edge.

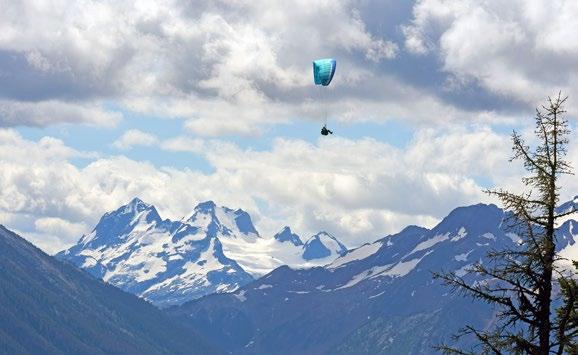

Along the way he’s directed or produced 19 ski/paraglide/ action sport documentaries, visited 57 countries, slept with 57 women (as a lifelong bachelor he seems inclined to keep track), and knocked off at least 18 first ski descents around the world, including on some iconic Coast Mountain classics such as Wedge, Mount Currie, Atwell, Serratus, and Mount Waddington.

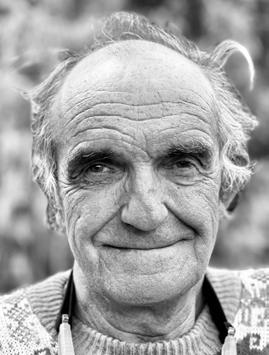

Sea to Sky filmmaker/ adventurer Peter Chrzanowski has always done things his own way—for better or for worse.words :: Feet Banks

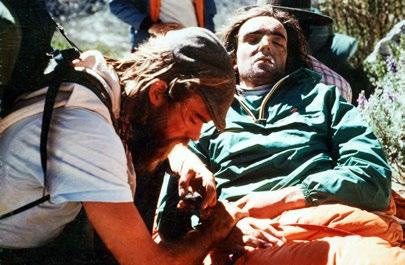

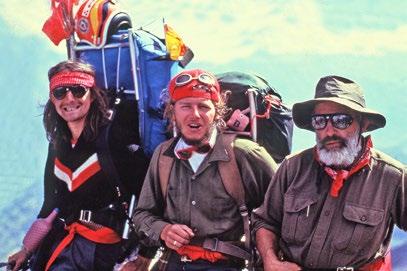

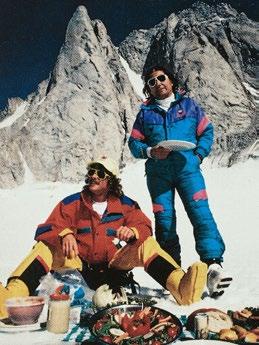

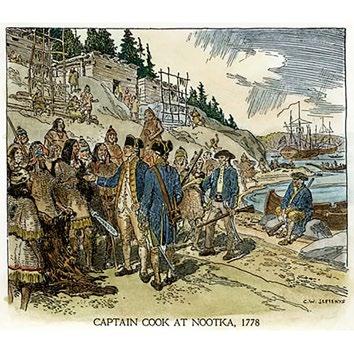

“The greatest trick the devil ever pulled, was convincing the world he didn’t exist.” – Keyser SözeABOVE Chrzanowski with Huascarán in behind. Peru, 1978. DAVE CLARKE. RIGHT PAGE, TOP RIGHT Peter (right) being tended to after his major fall on Ranrapalca, Peru. 1977. AMERICO TORDOYA. MIDDLE Eric Pehota ascends (and then skis) the much-coveted "summit knob" of Mount Waddington. Peter captured it on film for the 1989 film Reel Radical GREG MAURER. BOTTOM Straight outta New Brunswick, the 1978 Huascaran team. (Left to Right) Chrzanowski, Photographer Dave Clarke, Ski Peru producer. JOHN HOOPER

At the same time, Chrzanowski is known as much for his misadventures, injuries, and misfortunes (a friend fell and died on the first descent of the West Couloir of Wedge Mountain in Whistler), as for his accomplishments or total dedication to the mountain lifestyle. He’s broken his legs and ankles almost more

Chrzanowski’s advice for young ski bums: “Take time off and decide what you want to do. Follow your passion for a year or two. Decide what you love and enjoy it while you are young an strong. You can always sign up for a job you’ll come to hate tomorrow, or the next day.”

times than he can remember, and crashed his paraglider into most of the things one could crash into (including live electrical wires). He’s rolled vans, torn ACLs, been dragged hundreds of metres behind a snowmobile with a fractured leg, and tumbled down mountains on at least three continents, starting with a 700-metre doozy that deposited him into a crevasse while attempting to ski off the summit of Ranrapalca (6,162 metres /20,217 feet) in Peru way back in 1977.

“As I tumbled, I just relaxed, let go, and thought…oh well Peter, say goodbye to the world. This is it—the ‘land of the blue lights.’”

It wasn’t it. Chrzanowski crawled out of the crevasse (barefoot—both his light ski mountaineering boots had been torn off in the fall) and made it to basecamp and eventual rescue. Now 65 years old, and still going, Chrzanowski has spent the past three years pecking away at a 400-plus page autobiography fittingly titled, I Survived Myself.

A pioneer in both the Canadian ski mountaineering and action sport filmmaking communities, Chrzanowski’s life journeys include a rogues’ gallery of mountain legends such as Trevor Petersen, Eric Pehota, Sylvain Saudan, Steve Smaridge, Troy Jungen, Patrick Vallençant, Jim Orava, Johnny Thrash, Bob Dufour, and Beat Steiner. But also the Dalai Lama, Pope Jean Paul II, Pierre Trudeau, Wade Davis, Jimmy Hendrix’s brother (offering free music for a film!), a pair of Peruvian twins named Letty and Charo, and no shortage of pissed off ski patrollers and general figures of authority.

In perfect Chrzanowski style, Peter wrote the book in English, had it translated to Polish for publication in his country of birth, and is now spending the first part of this summer re-translating that version back to English (it’s a roundabout method, but will save thousands of dollars in editing costs).

In late April, Mountain Life caught up with Chrzanowski at his home in Pemberton to rehash some of the highs, lows, and wild times of a true mountain survivor.

“He had very poor decision making, but a lot of the stuff that happened wasn’t Peter’s fault…none of us knew any better. That was my excuse at least—I’d shown up the winter before in blue jeans with a pair of 190s. There we no transceivers in 1980, we didn’t have probes and shovels. No safety equipment, no idea. We were bootpacking under seracs on Overlord or dodging incoming avy bombs while poaching Whistler Peak. I figured out pretty early that he’s my friend, but I am not hanging out with this guy on these kinds of things anymore. I’m a resort skier.” –

Scott “Scooby” Paxton, Whistler iconBorn in communist Poland in 1957 to adventurous parents who kayaked, ski toured, and rock climbed, Peter—an only child—learned to ski from his grandfather and carried that passion with him when his family relocated to New Brunswick, Canada in the mid-1960s. As a teen, Peter took to the manoeuvers of freestyle skiing at his local hill, Crabbe Mountain (two rope tows and 1,000 feet of vert) while simultaneously pining for the big mountain antics of European skiers like Patrick Vallençant, Jean-Marc Boivin, and the Swiss master Sylvain Saudan, who pioneered skiing steep, 55-degree slopes in the Alps.

“Extreme skiing had a certain draw for me,” Chrzanowski says, “because only you are responsible for your actions. You could use and harness your fear to perfect your style.”

Exposed to the big mountains of Peru, Chile, Argentina, British Columbia, and Alaska on holidays with his parents—a geologist and a survey engineer—Chrzanowski ended up in Peru at age 17, working with his father for a Canadian mining company.

“The work base itself was over 4,000 metres in elevation,” he says. “So I’d climb and ski the surrounding glaciers on my time off. My first ski descents of the Andes started there, in 1976. I liked being in a state of fear which the high alpine generated for me. I found I skied better—more precisely and technically— when I was being terrorized by, and in awe of, the terrain around me.”

Chrzanowski on regrets: “Maybe I let a few ladies go along the way without really taking the time. Maybe some would have stuck around if I wasn’t always going forward so much. There was one especially…”

After a slight mishap with the Columbian authorities while vacationing in the port city of Leticia, one of the most dangerous cities in South America at the time (“The coffee in the jail was great—Columbian black coffee. Still, I was scared. I was 17 years old.”), Peter spent the next winter shipped off to the “safety” of Europe. This led to the infamous “Penthouse Guide to Après Ski” hustle while he skied some first descents in the Alps and enjoyed the party/sex/ski lifestyle of ‘70s Euro ski culture.

By 1978, however, he was back in Peru combining ski alpinism with filmmaking on a quest to ski, and document, the first descent of Huascarán, Peru’s highest peak (6,768 metres/22,205 feet) with a couple Canadian friends and a barebones (and inexperienced) film crew. A team of experienced French skiers, racing to ski the peak first, caught up to the Canadians.

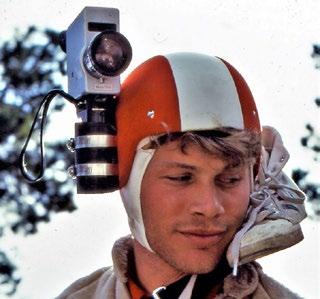

“We had to take a look at Peter’s gear. He had a diver’s knife that weighed over a kilo; it said everything about his lack of experience. He was also carrying two cameras. One he could attach to his helmet, the other, incredulously, had a mount for ski shoes. We understood why we had caught him so quickly. On the plus side, an amazing amount of high-altitude food and an isolated tent. In exchange for his gite and food we agreed to carry a camera to the summit and to help Peter on the climb.” – from the Journals of Patrick Vallençant, French extreme ski pioneer

The rest of his crew had to turn back, but Chrzanowski made it to 6,200 metres with Vallençant before handing the French team a camera to get him footage off the summit. The subsequent film, Ski Peru, won a few festival prizes, and by the time Chrzanowski showed up in Whistler that autumn he had two things locked down: a dream to use film to continue pursuing a life in the mountains, and a new nickname: Peter Peru.

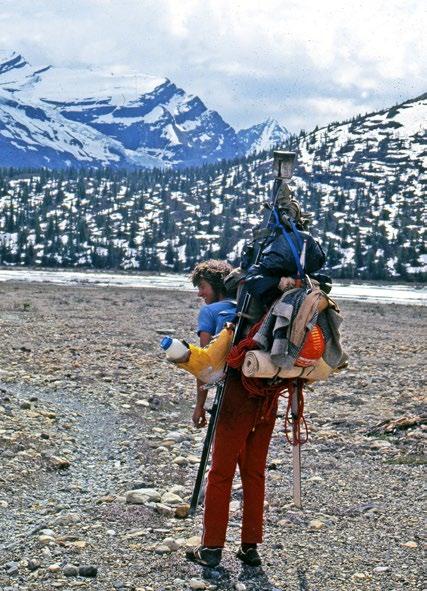

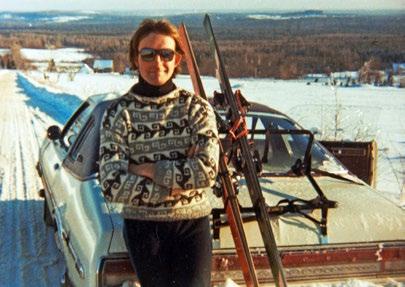

TOP LEFT Straight Outta New Brunswick...Peter Peru, one of the most infamous skiers of his era. CHRZANOWSKI ARCHIVES. MIDDLE Bart Ross on the approach to Mount Robson, 1981. CHRZANOWSKI ARCHIVES. BOTTOM Summer fun on the Phoenix Glacier, Garibaldi Park, 1981. (Left to Right): Nigel Protter, Chrzanowski, Steve Smaridge, John Reed. CHRZANOWSKI ARCHIVES

TOP LEFT Straight Outta New Brunswick...Peter Peru, one of the most infamous skiers of his era. CHRZANOWSKI ARCHIVES. MIDDLE Bart Ross on the approach to Mount Robson, 1981. CHRZANOWSKI ARCHIVES. BOTTOM Summer fun on the Phoenix Glacier, Garibaldi Park, 1981. (Left to Right): Nigel Protter, Chrzanowski, Steve Smaridge, John Reed. CHRZANOWSKI ARCHIVES

“Peru has never been interested in the technical quality of his movies, that is not why he’s doing it. He cares what is happening in the movie more than the movie itself. – Beat Steiner, skier, filmmaker, heli-lodge entrepreneur

Steiner met Peter Peru at a student rental house in Vancouver. “He came in talking about skiing and making movies and I said, “I’m in,” Steiner recalls. “That was how I got into skiing stuff that had never been skied. People around here weren’t looking at the mountains with that mindset and Peter had been so influenced by the Europeans.”

Throughout the early ‘80s Steiner would ski a number of notable lines with Chrzanowski, including on Serratus, Atwell, and the Diagonal chute on Mount Currie in 1985 (accessed by hiking straight up the face). Steiner also joined Chrzanowski as a skier/filmmaker on a number of his more infamous film expedition attempts to ski Mount Waddington (the highest in the Coast Mountains) and the north face of Mount Robson, the highest point in the Canadian Rockies.

“Not many people remember, but the word ‘extreme’ as it relates to skiing came from the book Ski Extreme, by Patrick Vallençant,” Chrzanowski explains. “So I will say, smugly, that I was instrumental in bringing that word to North America in 1982 when we formed the Extreme Explorations film company.”

Enrolled in the film department at Simon Fraser University while recovering from a torn ACL, and with the Ski Peru film already on his resume, Chrzanowski found himself faced with two potential life paths. “The first was to have a normal life, maybe including a family and kids,” he says. “The second was to take the often-cursed, wild ride of underfunded adventure documentary filmmaking; a life of continuous travel, difficult productions, and long hours editing to make the films. I chose the latter and chose never to look back.”

Extreme Exploration’s first film, In Search of the Ultimate Run, saw Chrzanowski and Steiner take $1,000 from the SFU film program and another $500 from a sports producer at the Canadian Broadcasting Company. Chrzanowski, Steiner and six friends loaded into two vehicles and headed for Mexico to ski Popocatépetl, the famous 5,426 metre (17,802 foot) dormant volcano outside Mexico City.

PELVIC FLOOR PHYSIOTHERAPY & REHABILITATION

SPORTS INJURIES & ORTHOPAEDICS • MANUAL THERAPY CRANIOSACRAL THERAPY • VISCERAL MANIPULATION EXERCISE PRESCRIPTION • CLINICAL PILATES

Treatments are conducted in a private clinic setting, with one-to-one attention from our well-trained and attentive physiotherapist.

T: 604 849-4688 | E: kar@evergreenphysio.ca | Book online at evergreenphysio.ca | Location:1385 Depot Road, Brackendale Parking is available on the street.

booking@whistlerpaintball.ca

604-932-3524 whistlerpaintball.ca

OPENING JUNE 3RD 2023 book now

Base of Wedge Mountain

The trip was a success and included all sorts of party antics and tangential booze (and worse)-fueled adventures. They even crashed Keith Richards’ wedding by climbing a fence in Cabo San Lucas. “Several of our crew ended up spending the night in a Mexican jail but I got away,” Chrzanowski recalls. “I returned to SFU two weeks late for classes. The head of the film department shunned me, but we produced a half hour film—shot on Super 8 and extreme in every way. I was proud of it.”

“How does a 21-year-old with no money, resources, or experience even consider making ski movies, on film?” Steiner asks. “But that didn’t stop him. He had rampant optimism—just do what you can and do it anyways. The end goal didn’t matter as much as that it was fun to try. And I got sucked into that for a few years.”

Waddington Now became another example of Chrzanowski’s ability to piece together a film on a shoestring budget. He and Steiner interviewed iconic mountaineer Phyllis Munday, who had spotted the “mystery mountain” in 1925 and spent the next 30 years trying to summit it with her husband Don. He also traded the rights to his uncompleted movie to the Whyte Museum in Banff in exchange for historical Waddington mountaineering footage. In the end, it took two attempts to get the film in the can. But in 1985 Chrzanowski, Trevor Petersen, Steve Smaridge and Beat Steiner skied the first descent of the Angel Glacier from just below Waddington’s summit knob. (Eric Pehota would later ski that same exceedingly-steep summit knob for the 1990 film Reel Radicial, Chrzanowski’s last collaboration with Steiner and Jacques Roiseux, who both branched away from Extreme Explorations to form AdventureScope films and look towards the “new” sport of snowboarding.)

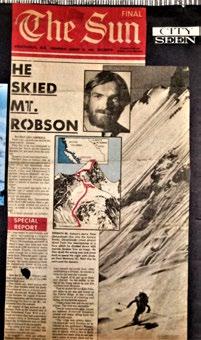

It was Mount Robson however, that became Chrzanowski’s cinematic raison d’être, his “rosebud.” After seven years of

repeated failed attempts to ski (or even access) and film the north face of the mountain, Chrzanowski finally combined all his and Steiner’s footage with that of Dave Frazee to produce The North Face, Seven Years on Mt Robson, released in 1988.

“We had made several trips to the mountain in between planning the first fiasco in 1980, my own successful descent in 1983 and finishing the Mount Robson film in 1987,” Chrzanowski says. “It became my most successful film but also, we had huge bureaucratic problems with BC Parks and our permits. At one point, I had to go, last minute, to the Ministry of Tourism which held more clout than Parks. Eventually I got a call saying, ‘It wouldn’t be right to give you the permit but just go do your trip, we’ll look the other way.’ From then on, I knew, there’s always a way to beat the bureaucrats at their own games.”

And that now-infamous 1981 footage of Chrzanowski lowering utterly unqualified ski alpinist Jacques Thibault off the summit of Robson on yellow polypropylene “Canadian Tire” rope? This scene has long been used to criticize Chrzanowski’s experience and safety levels, but, according to him, it was all just movie magic.

“We had to do something,” he explains. “Our promotor Chuck Hammond, if that’s even his real name, had 48 reporters and three helicopters filming us and we couldn’t access the face. I unravelled that rope in order to make a show of things for the media. Creativity was required! Jacques was thrashing around, and I basically ran out of cord so the mountain guides and I all had to drag him back up for the cameras. That fiasco was embarrassing, Chuck was a crook and Jacques was not a mountain guide. I got sucked in because I had a bit of a reputation and was too gullible to properly check everyone was who they said they were. I went back to Whistler embarrassed by the whole ordeal.”

But at least he caught it on film.

LEFT Legends of the sport. Eric Pehota (left) and Sylvain Saudan on Mount Waddington for the film Reel Radical, 1989. GREG MAURER. MIDDLE With celebrated extreme skier Kristen Ulmer en route to Columbia. 1998. CHRZANOWSKI ARCHIVES. RIGHT: Chrzanowski on a summer ski tour of the Ipsoot Glacier, Pemberton. 1981. BART ROSS

“Safety is not the top box on Peru’s checklist. His conception of what to do or what is acceptable is not the same as most people’s. I was there for some of the chaos and it’s outrageous the number of times he almost killed himself and didn’t. Especially when he started flying paragliders.” – Beat Steiner

“Ask him about paragliding off Blackcomb Peak…No, ask him about trying to launch down the upper Christmas Chute. Yeah, ask him about that.” –Eric Pehota, ski mountaineer

Steiner witnessed the Christmas Chute fiasco.

“This is like, 1986,” he recalls. “There was no one paragliding, no one to teach us, and I remember Peru trying to take off from the top of Christmas Couloir on Whistler and he wanted me to film it. He takes off and the wind slams him into the cliff, then he crashes back to the ground. He grabs his stuff and goes back up and tries again…Same thing happens. Goes back up, tries, slams again a third time. I stopped filming. Another time he was flying off Whistler Peak towards Cheakamus Lake, spiralling out of control into the forest. We were supposed to pick him up in Function Junction and he comes out of the woods unscathed saying, ‘I just picked a tree that looked easy to climb out of.’ He crashed into the tree, through the tree, and landed on the ground unhurt.”

Paragliding off the ski hill was strictly forbidden in those days. Which didn’t deter Chrzanowski, of course, and he remembers that fated Cheakamus Lake flight well. “I was flying alright when one of my brake lines snapped. I could still steer with the back risers, but you lose a lot of altitude doing

this and before I knew it, I was skimming the tops of 150-foot tall cedar trees, until I finally hit one. I had my skis on though, and was able to lean forward and get my skis below me. They broke the branches and slowed me down, and somehow I landed on the ground. I’d sheered branches off a whole side of the tree and my paraglider followed me down without getting caught up. So, I packed up and skied the rest of the way.”

Nowadays, paragliders ride thermals, updrafts of warm air, to gain elevation. Chrzanowski himself has used thermals to fly 112 kilometres from Golden, B.C. to Invermere, but this practice (and the equipment to do it) wasn’t common until about 1999.

“I’d ridden warm air upwards before but hadn’t really understood the atmospheric mechanics of the process,” Chrzanowski says. “I shot way up off the top of Black Tusk once, because of the black volcanic rock drawing the heat, and crashed on the Helm Glacier on my butt. Another time in Pemberton I experienced what paragliders call ‘sudden sink’ and knew I wasn’t going to make it to my landing. I panicked a bit, and trying to make it to a large horse corral, I smashed into

the dormer window of someone’s house and fell about 30 feet to the ground. Turns out it was my buddy George, who came out with his three-year-old daughter. He handed her the phone and said, ‘This is how you call 911.’ I ended up with two broken legs, a broken arm, a couple lost teeth, and very bruised ego.”

In the early 2000s, paragliding was a relatively small sport with a tightknit community dedicated to progression and good times (not all that different from the early extreme skiers of Chrzanowski’s youth). For him, it was a new way to experience the mountains, push his own limits, and inspire more global travel, new films, and new events. In 2006, Chrzanowski organized the world’s first ever paraplegic FLY IN in the tiny B.C. community of Hedley. He began flying in Mexico and Europe, and in 2007, paragliding brought him back to Peru, a country he hadn’t visited in almost 40 years.

After Canadian bureaucracy, this time at the hands of our immigration service, foiled Peter’s ambitions with Jenny, a Peruvian journalist who may have been the love of his life, in 2008 he ran with the idea that the best way to find a “soul mate who could paraglide” was to make a film about his search for one, and the result was Paracinderella, which was still in production when Chrzanowski crashed hard flying in Peru and broke a femur and cracked his pelvis. On the bright side, he got some great footage on the ambulance plane back to Lima that made it into the film

By 2013, cheap digital cameras and internet video sharing technology was making it increasingly difficult to fund or make a living off films. But on a para-trip in Malinalco, Mexico, Chrzanowski encountered his next big thing. “It was truly ingenious,” he says. “An event—a relay race—featuring segments of running, paragliding and mountain biking. A friend I had met in Mexico, Pablo Lopez, had invented it—he called it the Aerothlon.”

With big plans to bring the Aerothlon format to his hometown of Pemberton—a mountain bike and fitness epicentre with a paraglide launch right above town, Chrzanowski crashed into one of his most immovable objects yet again: Canadian bureaucracy.

“I wanted the event to start right in downtown Pemberton to really involve the community,” Chrzanowski explains. “Canada’s love affair with litigation makes that a non-starter. I found out the flag people I’d need at every intersection and side street would eat up more than half my budget. I guess Pemberton is ready for big corporate events like the Ironman races, but for a homegrown thing there is no support. There are people whose job it is to help support these kinds of things, but as far as I can tell they meet once a year for pizza to pat each other on the back and that is the end of it. It’s a joke.”

He did manage to pull off a successful Pemberton Aerothlon in 2018, and twice more since then, but he’s found the level of support is much more robust in other countries. He recently staged one in Poland in late May.

After more than 30 years of flying—and numerous injuries and close calls—Chrzanowski’s reputation in certain paraglide circles is reminiscent of how people used to view his ski mountaineering exploits. The phrases “brain damaged” and “sociopath with a death wish” have been tossed in his direction, with campaigns organized to prevent him from ever flying again— sometimes at launches he himself helped establish. The animosity stings; it’s visibly obvious when he talks about it, but Chrzanowski also points out that his most vocal critics almost always have competing financial interests.

“The best way I can describe paragliding is that it’s dangerously easy,” he says. “It requires a lot of skill and patience, waiting for the right winds and weather. Mistakes and poor decisions can result in death or severe injury. I have four major accidents under my belt, but each one has a reasonable explanation, including my own pilot errors. I know I am not always the most careful person when I practice paragliding or skiing, this is why I don’t do tandem flights or take passengers flying. I have no kids or family and my risks are mine alone. It’s not for society to dictate how we should lead our lives. If I am to return to the ‘land of blue lights’ I would rather do it as a result of my own choosing, rather than dying of boredom at some old-age home.”

didn’t know. The Pope said he’d enjoyed my film about Trevor (The Spirit, 1997) and was blessing me. That Pope was a skier, and Polish—he had come from my hometown.”

Through his films, his adventures, and his ski bum antics (every year, the Whistler squatters used to find out what colour the backgrounds were on the season pass pictures and recreate a backdrop of construction paper to hold a “pass photo” party for their forgeries), his love for the mountains, and the culture of those drawn to them, has always been the driving force.

“It’s getting worse over my lifetime,” he laments. “The bureaucracy, the corporations…It’s more homogenized. The kids are still fighting the good fight for these kinds of lifestyles, but don’t have much of a chance. They can’t sleep in their vans in Whistler. They can’t build a cabin in the woods, but also, we have so much room here—just push deeper.”

“For me,” Chrzanowski continues, “I’ve always enjoyed the quiet and the solitude in the mountains. Skiing and paragliding gave me the connection I was looking for. For my first film, I found an old Chinese proverb: ‘The body roams the mountains, and the spirit is set free.’ That also reminds me of something mountaineer, Polish mountaineer, Jerzy Kukuczka once wrote in his journals: ‘After every safe return there is always such a sense of euphoria and accomplishment. We always come back wiser from the experience.’”

Kukuczka, who summitted all 14 of the world’s 8,000-metre peaks, may as well have the last word on Peter Chrzanowski as well:

After the tragic death of his friend and film subject Trevor Petersen in a 1996 avalanche in Chamonix, Chrzanowski began to dig deeper into what the mountains mean to the people who spend their lives in them.

“I reached out to both the Dalai Lama and the Pope trying to get an idea about the universal spirituality that one experiences in the mountains,” he says. “The Dalai Lama responded that he

This piece only barely scratched the surface of Chzranowski’s wild tales. Look for I Survived…Myself in bookstores this fall and at peterperu.ca

“The human organism is a lot stronger than we might anticipate.”TOP LEFT Peter Peru, still surviving.... SIMON BEDFORD. BELOW Enjoying another fine day in the Blackcomb backcountry. SIMON BEDFORD

In the forest at dusk, the trees have eyes

words & photography :: Ben HaggarThere are few things I love more than an evening in the woods just after the sun slips behind the mountains. As the oppressive heat of the day subsides into cool comfort, the ambient light reflecting off clouds trades harsh shadows for soft orange hues that darken into the deep greens of moss and saplings. The forest becomes still, humid, and peaceful, but with that tranquility comes a heightened alertness—every sound becomes more audible, but so does a sudden lack of sound. At dusk, when the forest goes still, a sneaking paranoia sets in. Is someone, or something, watching?

On an annual maintenance mission to the popular bike trail Dark Crystal on Blackcomb Mountain, Scott Veach and I had spent the afternoon splitting cedar slats and nailing stringers together to create two small bridges. Scott’s dog Zephyr, the deaf Arctic Dingo and our constant trail companion, has a tendency to lay right where we’re digging, but this particular day kept even more underfoot than usual.

With sun well below the horizon, we’d packed up the tools, and were enjoying the “builder’s special”—river-chilled beers—when blood-curdling screams abruptly broke the evening silence. They sounded to have come a few hundred metres down the trail, and tailed off almost as quickly as they’d arrived.

An ex-Californian, Scott was immediately on edge: “Sounds like tweakers living in the woods.”

To me, it sounded more like the stick-sword fight battles from my pre-teen days of forest adventures, but we were a bit far from any houses, and it was getting late for kids to be out this deep.

In the dim evening light, we waited for any other sound or clue to what had occurred. The forest answered with only a deep silence… too silent. We stashed our tools just where we left them. Chugging the last of our beers—with a side of apprehension—we started the ride out with Zephyr in the lead.

Enjoying a freshly-manicured section—a set of new corners completed the day prior—I began to forget the strange screams in the woods and enjoyed the flow of a familiar trail in prime condition… until Scott uncharacteristically skidded to a stop: “Look…”

Chills sped down my spine and muscles tensed with an unconscious primordial instinct as my gaze turned upwards to discover—just a dozen or so metres away—a large male cougar clinging to a cedar tree directly beside the trail. My first reaction— suppressed, but noticeable—was an urge to giggle, to fill in the nervous, silent, stifling space as the cougar stared at us and we stared back. I can’t imagine a more powerful looking animal. Long and sleek, the massive cat’s biceps and shoulder muscles dwarfed

its comparatively small head while a long, elegant tail flicked in… agitation? Curiosity? Impending doom?

My instincts took over. “Don’t move,” I told Scott while slowly digging into my pack for the only camera I had—a compact Canon G7X. My movements, though subtle, caused the cougar to begin climbing down the tree. To flee? To attack? Its eyes never left us. But then Zephyr, who had remained rigid and silent, barked aggressively and sent the cat back up the tree.

Gripped with fear and urgency (or was it urgency and fear?), I snapped two blurry photos in the fading light. Despite my training as a professional photographer, my frozen brain had seemingly lost the cognitive skills needed to adjust my camera settings, but the cat remained still long enough for me to take a deep breath, steady myself, and finally create a sharp photo at 1/6th of a second.

Mission accomplished. Let’s go.

But do we bushwhack around the beast, hauling bikes through thick brush, or ride directly underneath it as quickly as possible? For whatever reason, we chose the latter and rode straight past the treed cat—Scott leading, Zephyr in the middle, and me in the back. With a short run in, gaining speed on the flat rough trail felt like riding in quicksand, and we probably could have reached up and touched the cougar’s tail as we hammered past in a frantic blur racing for the adjacent hilltop.

Safely there, I looked back in time to see the cougar jump down and disappear into the bush in a single fluid movement.

We’d pushed our luck far enough to consider lingering longer. Flush with adrenaline, hands death-gripped onto the handlebars, Scott and I rode faster and sloppier than ever before, until we ran into two female acquaintances of mine—Lauren and Stacey, who were running down the trail with equal parts expedience and grace.

It turns out they were the ones yelling earlier. The cougar had boldly stalked to within three metres of them, very interested in their leashed dog, Daisy. It took a lot of yelling, posturing, and stick throwing for the cougar to back down. I can only imagine how intense it must have been for them to, at some point, turn their backs to the cat and flee on foot. Scott and I—on bikes, with a medium size dog, and the cougar in a tree—had both nearly peed our pants.

We rode short sections of the trail, then waited for the girls, always keeping everyone within sight while night swiftly took hold. As we gained distance from danger, euphoria flooded my system at surviving such a close encounter with a powerful predator, but I also got shivers of trepidation wondering how long we’d worked away in blissful ignorance while the cougar surveyed our position and, more closely, our deaf companion Zephyr. I thought about the hundreds of hours I’ve spent in the forest—happily building trails or riding them—while yellow eyes watched silently from the shadows.

My first reaction—suppressed, but noticeable—was an urge to giggle, to fill in the nervous, silent, stifling space as the cougar stared at us and we stared back.With innumerable rocky cliffs, caves, and crevices, Blackcomb Mountain's old growth could be home to anything... Rob Burns isn't waiting around to find out.

Nic’s burst of positive energy, attention to details on introduction to the gears and safety measures, and general rock etiquette. It was so encouraging! Highly recommended.

Dramatic natural landscapes, stunning views and wildlife are signatures of the Robert Trent Jones Jr. designed, Audubon certified Fairmont Chateau Whistler Golf Club. Top it off with unmatched course-side dining at the Clubhouse and you are in for for the ultimate day of golf in Whistler.

SCAN TO BOOK OR CALL 604 938 8000

P: BRAD KASSELMAN PHOTOGRAPHY

P: BRAD KASSELMAN PHOTOGRAPHY

As an earth scientist and photographer, one thing has always struck me—the more you look, the more surprising things you see. If we look at something that hasn’t been observed much, everything will be unexpected. And sometimes we catch a glimpse of something that changes how we see everything. And other times, we hear it.

In 1970, Roger Payne led a team that released a five-track, 34-minute album called Songs of the Humpback Whale. To everyone’s surprise, it sold over 125,000 copies, making it the most popular nature recording ever.

In that same year, 323,661 whales were slaughtered. Payne was confident that if people heard the songs, they would think differently about whales. They would care.

Greenpeace boats drove between harpooners and whales and played Roger’s album. Public pressure began to mount. And in 1972, the United States passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act prohibiting the killing and hunting of whales in the U.S. waters. Roger had used the songs’ beauty to save the whales, appealing not to our reason but to our emotions and empathy. Although whaling continued in other parts of the world, Roger gave the whales a voice. This one individual is a huge reason why there are still whales in North American waters today.

These days, many whale populations are recovering, but there are new dangers beyond the whaling industry. Some whales washed up on shore so full of heavy metals they are treated as toxic waste. Others have giant plastic floats in their stomachs. Some have clearly been hit by boats or fatally

caught in fishing nets. Industry that operates underwater, such as offshore fracking or drilling, can be fatal for cetaceans. A sonar pulse is like a sound bomb, sometimes causing mass strandings of hundreds of

Humans have hunted blue whales until just 0.1 per cent of their population remains. That would be like killing every human on Earth except for the people of B.C.

animals. Noise pollution can also scare and disorient whales until they beach and die.

In 2020, just as the COVID pandemic arrived, I followed my curiosity after a few decades of landlocked living and moved to the ocean. I’d heard the whales had begun

When Nasa launched their Golden Record aboard the Voyager spacecraft in 1977, one of Payne’s songs was included along with Bach, Mozart and Louis Armstrong. Then, in 1979, an extract from the album was sent to all of National Geographic’s 10.5 million subscribers. This made it the most extensive single pressing in recording history – a record it holds to this day.

chatting with each other in an unprecedented way. Why? Perhaps because most of the marine traffic had stopped—suddenly there were no cruise ships, the shipping routes were drastically reduced, and oceanic background noise levels had dropped by about six to eight decibels, which is immense on a logarithmic scale. For the first time since the industrial revolution, the whales had a chance to communicate without constant interruption.

I had so many questions, which led me to some exciting facts. Like finding out that blue whales are the second loudest animal on Earth, Belugas call each other by unique names, humpbacks in different areas “tune-up” their songs throughout a breeding season—by the end, they are all singing a single coherent song.

I wondered what they were telling each other after decades of extreme noise pollution, so I purchased my own hydrophone and sailed into Blackfish Sound off the northeast coast of Vancouver Island. Located within the territory of the Na̱mǥis First Nations, Blackfish Sound consists of countless islands and inlets offering beautiful natural scenery in sheltered and tranquil waters. Blackney Pass connects Queen Charlotte Strait with Johnstone Strait, where the strong currents churn up nutrients from deep below, feeding everything from small herring to the 40-tonne humpback whales. A perfect place to plunge my hydrophone down and indulge in the dreamy universe of whale songs.

Through (probably annoyingly too frequent) communication with the cetacean team at Raincoast Conservation, I began to learn about what I was hearing. The three main types of sounds made by whales are clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls. Clicks are believed to be for navigation and identifying physical surroundings. I learned that Orca travel in pods and that the three southern resident pods share some calls, but also have unique calls. Together, these three pods form a clan, J-Clan. Clans do not share calls with other clans, so the northern resident orcas and the southern resident clan have their

own unique calls. The whales use dialects as acoustic indicators of group identity and membership, which might preserve the integrity and cohesiveness of the social unit.

In human evolution, speaking the same language as someone else helped us know who to trust and who to support. Suppose these whales transmit their learned behaviours and pooled knowledge to only specific species members. Can we say they have cultures? And if so, how much of it was lost during those decades of whale hunting and slaughter? How much is at risk today due to noise, chemical, and other pollutants? In human history we know culture loss occurs before extinction, but we also know culture can be saved.

Fortunately, conservation groups are showing up. In Blackfish Sound, Orca Lab has recorded whale sounds for over 60 years, showcasing the unique cetacean culture. MERS (The Marine Education Research Society) is working at reducing threats to marine wildlife by responding to reports of entanglement, vessel strikes and other human-caused incidents. Raincoast Conservation is working to form a coalition of individual hydrophone operators to create an

effective long-term system that can monitor and reduce underwater noise impacts on marine organisms on the BC coast, including species at risk. Connecting the sounds will be a significant first step toward creating more understanding of the issue.

With the Canadian government’s goal of conserving 30 percent of the country’s land and water by 2030, there is hope for more quiet areas designated to give whales a sonic break. The more we learn about other animals and discover evidence of their capacities, the more we care, and this alters how we treat them. As the songs of whales change every

year, our culture is changing too.

Roger Payne was right—we will conserve what we love. We will love only what we understand. We will understand only what we are taught.

Sailing is still scary to me. Often, I have knots in my stomach, but on days when the fog sets, the wind dies, and the only stimulus comes from my hydrophone, time stops. Those are the moments I come into my awareness. I am connecting—to myself, my surroundings, and to the whales. I am learning about them from them. I am being taught.

Heli-accessed lodge // guided hiking trips // whitecapalpine.ca

@whitecap

@whitecap

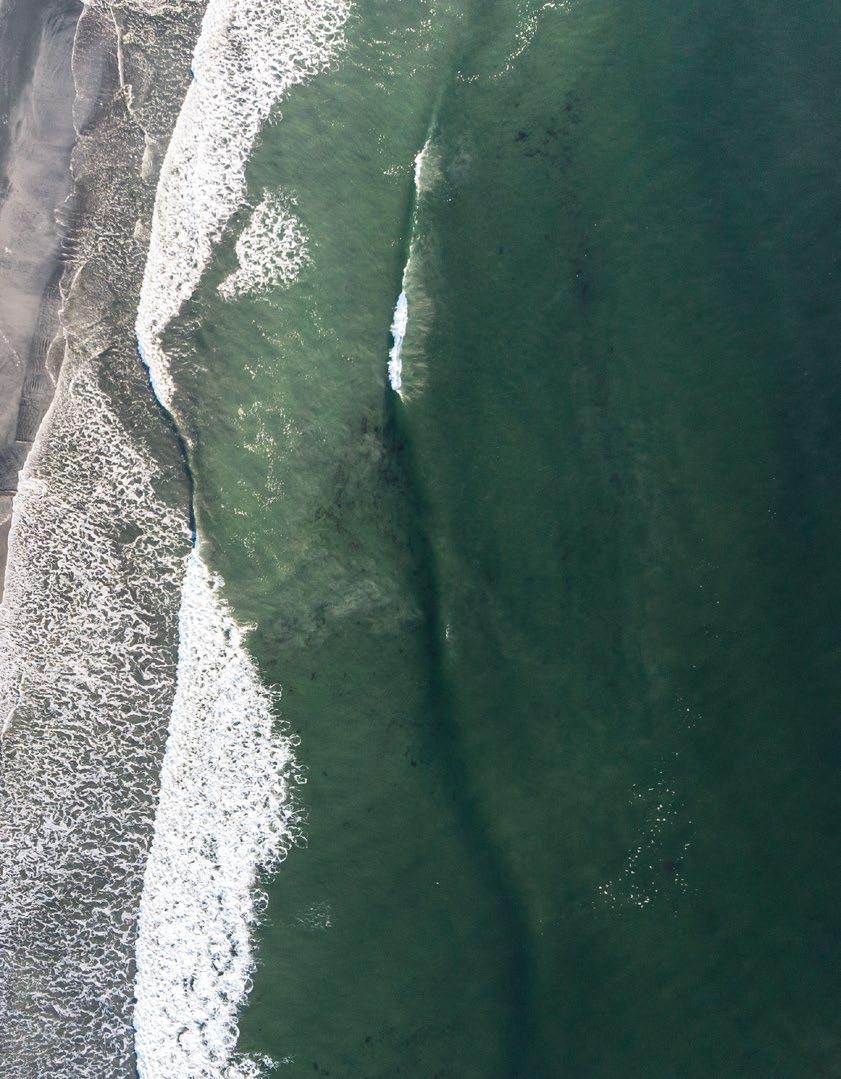

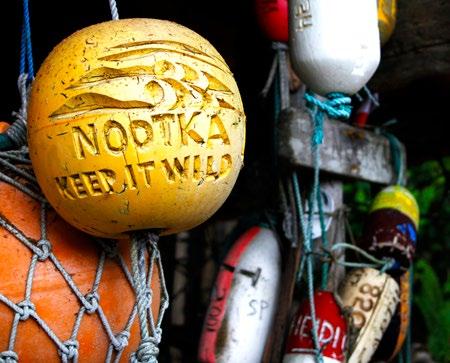

Given space and time, the planet doesn’t require human intervention to heal itself. For evidence, look no further than the Hada River watershed, located deep in the fjords of Kwakwaka’wakw Territory, now known as the Broughton Archipelago.

For more than 30 years, the route for wild salmon to leave and return to the Hada has been obstructed by open-pen salmon farms. But in 2022, the first generation of wild salmon returned to their spawning grounds on the Hada without exposure to the fish farms, thanks to a protracted and contentious campaign by local Indigenous groups. By the end of 2023, the Canadian government will have removed all 17 farms in the area.

For the fish, the results have been remarkable. Hinted at by the thousands of ripples and splashes on the river surface, what lies beneath this remote river is a true testament to the resilience of the natural world in the face of colonial resource extraction and the adjacent ethos that humankind takes priority over all living and nonliving entities.

“For 25 years, the tiny Hada pink salmon fry have been forced to swim through underwater clouds of pathogens pouring out of salmon farms,” explains biologist Alexandra Morton, often referred to as the

Jane Goodall of Canada. “In some years, very few pink salmon made it to sea unscathed by lice.”

In 2020, the last time the two-year cycle of pink salmon brought them into the Hada, the number recorded had dropped from a historic high of 50,000 down to just a few hundred. The fry of that spawn went to sea in the spring of 2021, however, after the two closest salmon farms had been shut down by local First Nations. When this generation returned to the Hada in 2022, researchers counted more than 15,500 fish.

“That return was over ten times stronger,” Morton says, “in just one generation.”

And I was there, watching as the sun lit up the riverbed, the water alive with a teeming mass of pink salmon, their shimmering bodies packed from bank to bank as they prepared to lay their precious eggs. One of the most amazing natural wonders of the world,

“For 25 years, the tiny Hada pink salmon fry have been forced to swim through underwater clouds of pathogens pouring out of salmon farms.”

–Alexandra MortonHome sweet home. Salmon returns in the Hada River are on the rise. MEGAN HOCKEN-BENNETT

the salmon spawn is poignant reminder of the inescapable cycle of life, death, and rebirth that guides all beings, and of our own responsibility to leave a meaningful legacy for the generations yet to come.

“Salmon are literally the blood stream of this coast,” Morton explains. “As they die and decompose, salmon nutrients flow down the mountainsides feeding the trees. With the loss of salmon, the coast would become less resilient in the face of the changing climate. We would all be forever altered without salmon.”

Considering that salmon spawn in rivers that lead deep into the heart of British Columbia, a win for coastal salmon is a win for the entire province.

“I think it’s huge,” says Kwakwabalas Ernest Alfred, ‘Namgis hereditary chief. “Seeing and documenting what happens when you remove the [open net fish] farms, I think it is going to be the hard

evidence that we need, and that the government needs, to say with confidence that the problem [with the decline of wild salmon] was with the farms.”

Alfred has proven he will work, and sacrifice, for his territory and the salmon within it. In 2017, he and countless other tireless land defenders staged a 284-day occupation of several fish farms in the area. It was a bold move, and one that would ultimately prove instrumental in forcing the government’s hand to take action on the controversial fish farm issue. And while the fight to remove harmful foreign-owned, open-net fish farms from B.C. waters is far from over, courageous examples like these continue to inspire a new generation of activists and advocates to fight for these precious coastal ecosystems and communities

After the initial excitement surrounding the triumphant return of 2022’s pink salmon, attention has now focused on the continued revival of all the other species of salmon and wildlife in the area. The first generations of coho and sockeye salmon that passed through the Broughton after the farms were removed are set to return to the area this summer. Earlier in the year, the area saw a robust spawning season for another key indicator species, the Pacific herring.

“These little fish return and they let us know what’s coming,” Alfred says. “And they did that just last week outside of Port McNeill, right on our shores. The entire beach was turquoise; bright, bright colors. It was a stunning sight to see. This summer, we’re going to monitor and observe and document the salmon’s return. I hope to see the grizzly bears feeding and feasting like they used to. I hope to see wolves and I hope to see eagles and orca in big numbers. I think a lot of celebrating is to be expected.”

There could be many arguments made for the best word to describe the Full-10 Spherical: Speed. Style. Ventilation. Performance. All would be appropriate.

Since the Full-10 was developed from a half century of lessons learned pushing the limits in downhill competition and on rocky, rooty, rowdy trails the world over, we’ve chosen our own word: Descendant.

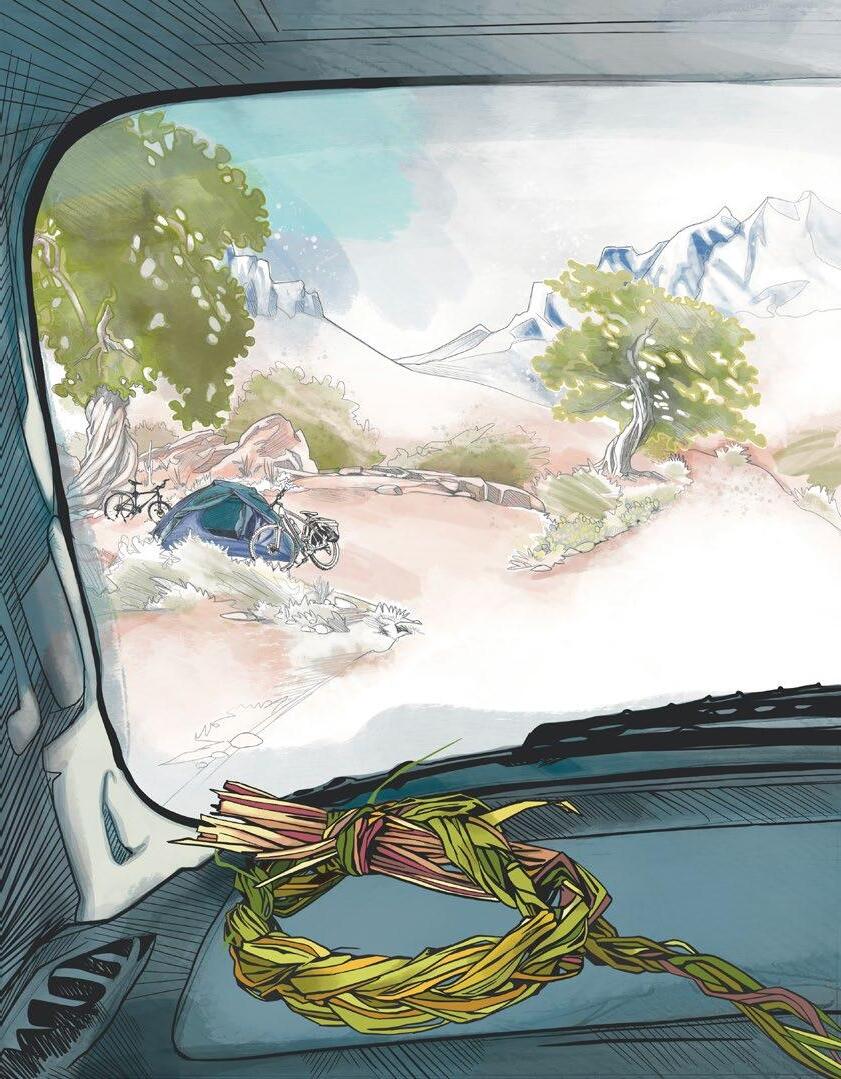

What does mountain biking mean to me? A simple question that has a crazy difficult and long response. Mountain bikes are my world in the summer, but it wasn’t always so. Just four years ago, I actually despised mountain biking. A friend gave me a bike to try out. I didn’t love it. I was only doing it so that I could eventually teach and run programs for the Indigenous Life Sport Academy. I wanted the kids to have access to this sport, but I didn’t actually like it. It scared me.

Looking back, I know why. I was pushed—too hard, too quickly— in an attempt to keep up with my friends. It was by no means a slow progression. I went from absolute beginner to riding double blacks. Inevitably, Injuries happened.

Fast forward to today. What’s changed? I now realize I can use my bike to access some very beautiful places, connecting to the landscape in a new and exciting way. Indigenous people all over Canada have always had a strong connection to our lands and everything on it. We see that everything has a spirit and must be respected. Every rock, tree, plant, and animal. We must never disrespect or shame these beings as we are also a part of them. The land and the people are together as one.

Nowadays on my bike, when I get to the top of a climb I love to sit and enjoy the views, maybe crack a can, but most importantly, feel that connection with the land and with the people I am with. I

wonder sometimes how far my bike will take me…

When I got a call to go explore the backcountry on the traditional territory of the Nxwisten people, I didn’t hesitate. I put my rig on the tailgate, grabbed all my biking essentials, and jumped on the road. Amidst all this excitement, I didn’t give much thought to actually preparing for a three-day camping trip… but the weather was supposed to be decent and—worst case—I got a tarp! If it’s too comfortable, is it still an adventure?

Agathe and I decided to embrace spontaneity and it all as a discovery experience. We had no idea what waited for us at the top of this insane climb. Peddling, pushing, portaging and bush whacking our way to the alpine. At the top, time stops. I let myself be filled with emotions, the beauty of the landscape and the feeling of accomplishment. And then…the exhilaration of the downhill, followed by a crisp dip in the lake, some good chats around the bonfire, and sliding into the sleeping bag next to my bike, under the stars. (With my bear spray handy though, I remembered that!)

For me, the contentment of an adventure pulled off beats the routine of comfort any day. Through riding my bike, I’ve learned to let go of the daily routine and go with the flow. I’ve connected to new territory and rediscovered new parts of my own home. I encourage you all to go on at least one crazy adventure this summer. You never know where you will end up, who you will meet and what you will learn about yourself.

RIDE FARTHER. RIDE FASTER. RIDE FREE.

After a long, hard day in the saddle, all we want to do is to pitch our tent within the grassy compound of a random farmyard, but our host is having none of that.

“This my house!” says Krystof in broken English, pointing proudly his rusty pitchfork at a stout-yet-nondescript red brick house behind us. “You stay here this night.”

We leave the cool, pure Polish country air and step inside, where the dank stench of mold literally stops us in our tracks. The smell triggers memories of my Polish grandparent’s basement from the ‘70s, a root cellar permeated with aromas of potatoes and dirt. I hated going down there as a child.

And Krystof’s kitchen is even worse. It reeks like old cheese, his tiny bathroom contains a sink the crusty shade of brown camouflage and a toilet that likely hasn’t felt the bristles of a brush in years (we’d

most definitely be hovering above that thing). The look on Christina’s face says it all—we don’t want to stay here, but being rude to a host would be worse. “Oh, thank you so much Krystof,” she says. “This is great…” The front lawn seems so peaceful, and suddenly so far away.

We’re in eastern Poland, five months into our year-long adventure, and Krystof has spent his entire 65-year existence on this hay and cattle farm along with his 87-year-old mother. A few minutes ago, when we arrived and kindly asked (via Google Translate) if we could spend the night on his farm, his face lit up.

“I cannot believe this!” he says, speaking into our magic translator box. “I would have expected a UFO to land here before a family of three Canadians on motorcycles.”

Christina and I have travelled through 69 countries together on motorcycles and randomly asking strangers if we can camp

on their property has always served us well. It allows for complete cultural immersion and has led to many lasting friendships, unique food experiences such as eating fried grasshoppers in Swaziland or barbecued iguana in Mexico—and, like in this instance, some definitely awkward and uncomfortable situations. However, when a stranger offers a place to stay, we simply cannot and do not refuse. Even though the state of this farmhouse makes us want to run for the hills, it’s being given to us with kindness, and it’s real and true to this place...

Krystof shows us around the house while his mom makes a cup of tea in her own separate (but equally dirty) kitchen. We follow him outside to start unpacking the bikes. Seanna grabs one of their many pitchforks and starts helping out, stabbing at a fresh bale of hay to take inside the barn to feed the cows. Since one of the goals of our journey is to retrace the footprints of our ancestors, I know

my Polish grandparents would be proud. And, watching our daughter independently pitching in to return a stranger’s kindness, Christina and I feel it too. This encounter—dank, moldy stench and all—is the exact kind of life-enriching experience we want for our ten-year-old daughter Seanna on her first global moto adventure.

After working hard until well after dark, Krystof shows up in the kitchen with a basket full of warm beer and a bottle of schnapps, wanting nothing more than to connect with his newfound friends. In the morning, every morsel of food he owns is laid out on the kitchen table but nothing looks enticing enough to eat. He sends us off with a loaf of stale bread, a warm handshake and a connection we’ll remember for a long time.

"The initial grand plan was to ship our two motorcycles to Ireland, and ride all the way to India over the course of a year. "LEFT TO RIGHT Rare slice of tranquillity. Kurnool, India. Breakdowns are part of the game. Verdon Gorge, France. The threedom salute. St. Raphael, France.

reach far-off, epic landscapes and discover diverse cultures. supported by 240 mm of high-end wp xplor suspension, the new norden 901 expedition has all the features you need to travel further.

all it takes is a turn of the wheels and whole new worlds are within reach.

There are many parents out there who believe travelling stops after you have a kid, or at the very least suffers dramatically. For Christina and I, the idea of a child affecting our plans and passion for travel was never an issue. If anything, we’d always hoped sharing the world with Seanna through our ground-level, nomad-on-wheels lifestyle would bring even more adventure and purpose to our adventures. Now we’re all truly finding out for ourselves.

The initial grand plan was to ship our two motorcycles (a 2021 Royal Enfield HIMALAYAN and a 2021 URAL Gear-Up) to Ireland, and ride all the way to India over the course of a year. We’d call it THREEDOM. We put a bunch of red dots on our paper map and went for it. Riding motorcycles (plus one sidecar, affectionately dubbed “the Mule”) with everything we’d need crammed into a few saddlebags would fuel the first flames of the sort of wild, selfsufficient lifestyle we love, and choose to introduce our daughter to. At age ten she’d be old enough to remember everything, yet still young enough to happily spend time with us every day.

Being gone for that long meant fully tapping into an elevated level of the art form known as dirtbaggery. We’d be cooking over open flame (saves fuel), cooking in hotel rooms instead of eating out (saves money), washing our clothes and dishes in hotel sinks and showers, eating cheap cheese-and-bread picnics alongside the road, wild camping under the stars, and staying with random people like Krystof along the way. As adventurous “moto” parents, we wanted to keep riding the road of raw and real exploration, in line with my late brother Sean’s favourite Metallica song: “Anywhere I roam, where I lay my head is home.”

Christina, Seanna, and I have succeeded in riding this rugged line on a few different levels; freezing hands and cold nights sleeping roadside on mountain passes in the Alps, hunkering down in abandoned barns to avoid menacing rainstorms, or getting lost on remote gravel roads in the middle of a deadly European heat wave. And sometimes we’ve failed miserably as dirtbags, and fled to civilization; laying our heads on pillows in expensive hotels with swimming pools, dining at seaside restaurants, taking hot showers and binging Netflix on unlimited wifi. That’s okay too; taking it easy and enjoying the pace.

Unlimited mobility. Unbridled freedom. That’s why we live behind the handlebars of a motorcycle. But by switching from holding handlebars to holding a paddle, we’d no longer be relegated to land-based adventure. We’d be in amphibian mode. With two inflatable SUPs strapped to our sidecar bike, the search for lakes, rivers, lagoons, seas and oceans opens the gates to countless new adventures and redefines our journey. Bikes and boards, surf and turf, the best of both worlds.

Venturing south we began checking red dots off our map—from the wild Atlantic Way in Ireland, to Croatia’s clear-water Adriatic Sea coastline. Finding and paddling new waterways allowed us to frequently escape the rigours of the moto travel routine; the packing, unpacking, setting up, planning, organizing, navigating, shopping and completing the everyday errands that start to take their toll after many days on the road. Paddling would also help us escape one another. When you’re with each other 24/7/365, things are bound to go sideways.

A colleague of mine summed it up best: “I refuse to allow school to get in the way of my child’s education.”

Seanna’s version of school would be two-fold: that of complete cultural immersion, of learning new languages, bartering in market stalls with different currencies, communicating with random strangers, reading books while riding, shooting photos and video, studying geography, caring for animals, creating art

Over two decades of moto trips around the globe I’ve learned that if one spends any real time on the road, something always happens. Sometimes it’s a serendipitous encounter so rich and awesome it embeds in your memory forever—the golden moments of life’s exceptionalism. But sometimes, other times, serendipity smells like shit…or at least a blown piston. That’s when our original plan to ride overland from Turkey to Pakistan and India via Iran comes grinding to a screeching halt.

A very expensive wrench has just been thrown into our spokes— our trusty sidecar is toast. Frustration rears its ugly head and no matter how hard we try there is no silver lining to be found. What the heck do we do now? Rent a campervan and continue the journey on four wheels? Sure. We call her ‘Lemonade’, and all we have to do is throw our gear from the bikes into the van and keep on cruising through and around Turkey, which we do for one mind-altering month.

Shit is also hitting the fan in Iran and it’ll be almost impossible for us to get a visa, let alone have “the Mule” ready before our Turkish visa expires. We don’t want to let the dream of India die, so we book tickets to Kathmandu (a necessary step to obtain our Indian visas) where we find the mother of all silver linings—trekking in the mighty Himalaya.

in her volume of sketchbooks, learning about the intricacies of nature, and a million other things. She’d also be connected with B.C.’s school curriculum through an online education program called SelfDesign, where she could file reports on the things and places she had experienced such as visits to national parks or UNESCO World Heritage Sites, of which there were many.

After all, our child’s education was crucial and important to us and sometimes that required staying put and connecting to the world in a different way, electronically, which in this day and age is hard to escape.

It all served to bring us closer together as a unit. Homeschooling, or ‘roadschooling’ as we prefer to call it, is a tough gig for both parent and kid. Arguments, resistance and expectations oftentimes weighed heavily on the experience and the only thing we ended up learning is how hard we can be on each other. Probably the most important lesson we learned is that she’d learn the most when we’re not trying to teach her anything.

"Seanna’s version of 'roadschooling' would be that of complete cultural immersion paired digitally with B.C.'s curriculum."Leysin, Switzerland.

There’s no place like Whistler and no better way to experience it than from the air! Fly into breathtaking perspectives of rugged mountain peaks, sweeping valleys and majestic glaciers on one of our spectacular scenic tours. Plus, take the real sea-to-sky ride and hop aboard one of our scheduled flights connecting Whistler to 12 scheduled locations across B.C. and Seattle!

Race & Company LLP has been proudly serving the Sea to Sky and our worldwide clientele with local knowledge and proven integrity since 1973. Our 35+ lawyers and staff are dedicated members of the community, providing volunteer time and expertise to a variety of local charities and organizations.

Injury Claims: Minor/Major Injuries

Slip and Falls

Wrongful Death Claims

Business & Personal Law: Immigration Incorporations

Real Estate Development

Buying/Selling a Property

Buying/Selling a Business

Wills & Estates

Family Law

Amongst these iconic peaks, connections really begin to flourish; Seanna holding the hands of elderly Nepalese women as I shoot intimate portraits, helping locals haul firewood in their woven “doko” baskets, and learning how to make Tibetan bread in the smoky kitchens of various tea houses along the way. They remind us of the connection we made with Krystof the Polish farmer—little communication, big meaning. We’re free from the worries of the motorcycles and all our gear, untethered to a schedule, no need to try to connect the little red dots that by now mean nothing. Walking “vistari, vistari” (slowly, slowly) throughout some of the world’s most stunning scenery adds a welcome layer of calm and peace to the journey.

And then, India hits us with all her might. As we make our way south from a small (and almost unbelievably quiet) farm near Hyderabad on rented Royal Enfields, there is no escaping the trafficinsanity, horns-a-blazin’, cow-dodging, masala-flavoured everything everywhere, onslaught of people (and pollution) in the world’s mostpopulous country.

“Sir, what is your native country?”

“Ma’am please take one selfie please?”

“What is your good name sir?”

During our 4,100 kilometre southern India loop, respite from

the madness only comes after we close the zippers of our tent and shut out what could be described as insanity in motion. Finding a way to connect with it all is the fun part, like “playing” in the exuberant Holi Festival, flinging colored powder at boisterous crowds of happy people and having raw eggs smashed on our heads, all to celebrate the triumph of good over evil.

Looking back on it all, we now realize that our journey has been all about connections: from friends we haven’t seen in years to many new friends we’ll have forever. Being outside in the elements almost every day has brought us closer to nature, more connected to Earth. And being together as a family for so many days on end has created a bond that time itself will never break.

After 365 days of travel, our bikes have now taken us safely across the landscape of 30 countries and three continents, and we’ve travelled by moto, ferry, boat, bus, taxi, tuk tuk, bicycle, plane, train and on foot for more than 50,000+ kilometres. The whole journey has been an education in and of itself—a lesson in humanity, geography, adaptation, resilience, compassion, and what true adventure can teach one’s soul. Our young daughter will have this trip in her back pocket for the rest of her life, and we can ask for nothing more.

By the time you read this, we may or may not be home yet. Depends if any more wrenches get thrown into our spokes—or whether we go back and help Krystof clean his farmhouse.

words :: Riley Leboe

words :: Riley Leboe

Tents, sleeping bags, outerwear, safety equipment, ropes, satellite messenger, cookstove, fuel, food rations, booze rations, shotgun… gear is everywhere, spread across the grass of a small property in the Bella Coola Valley while we frantically pack by headlamp with our 4:00 a.m. launch time rapidly approaching.

The “alpine start” reminds me of spending time with Kye Petersen in Haines, Alaska. On this trip however, instead of deep snow or steep spines, we’re chasing steelhead.

Known as “the fish of a thousand casts”, the elusive steelhead is considered the pinnacle of freshwater fish; they grow large and fight hard. So hard, that experienced fly fishers have a saying: “The tug is the drug,” and by all accounts, the aerobatics of a steelhead on your line creates one of the ultimate highs fishing can provide. We cram

the final pieces of equipment into our waterproof bags just as the clock hits four. We head for the marina in a truck stuffed with gear and anticipation.

It was Kye’s idea: a self-supported DIY trip to Dean River, a corner of British Columbia few people know about, and even fewer have visited. I was excited to visit one of fly fishing’s most hallowed waterways, but also wary about trekking into a remote place on our own. I couldn’t say no, even knowing that steelheading is often a suffer-fest, and even with perfect conditions, there would be few fishy rewards. It’s a small cohort that find joy in such missions, but for those who do, a bond is forged. With fellow river junkie Jarred Martin joining as our third, we had our band.

By the time the rays of the rising sun first hit the deck of Night Moves, the turquoise painted fishing troller we chartered in Bella Coola, we are well into the nine-hour journey to Dean River. Warm and

dry on deck, Jarred and I stare down at Kye riding his Sea-Doo along our port side. His determination to make the journey as DYI as possible is a testament to his ski-mountaineering ethos and cowboy personality.