Fall/Winter 2022 | Volume 1 | Issue 1

2022-2023 Board of Trustees

Anthony (Tony) R. Sapienza, Chair

Onésimo Almeida, Ph.D.

Thomas Anderson

Paulina Arruda

Christina Bascom

Ricardo Bermudez

Douglas Crocker II

John N. Garfield, Jr.

David Gomes

Vanessa Gralton

Edward M. Howland II

Meg Howland

D.

Robert H. Kelley

Per Lofberg

Lloyd Macdonald

Ralph Martin

Eugene Monteiro

Gilbert Perry

Victoria Pope

Dana Rebeiro

Cathy Roberts

Maria Rosario

Brian Rothschild, Ph.D. Tricia Schade

Christine Schmid

Nancy Shanik

Hardwick Simmons

Bernadette Souza

Carol M. Taylor, Ph.D.

Davis Webb

Alison Wells

Lisa Whitney

Susan M. Wolkoff

David W. Wright

Front Cover Image: Detail of Alison Wells, In the Neighborhood, 2020. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas. Gift of Michael and Michelle Kelly. NBWM# 2021.53.

Back Cover Image: Deborah Smith Taber (1796-1873). Illustrated handkerchief, c. mid-19th century. Fabric, 24 x 24 in. (61 x 61 cm). Gift of Martha Leonard, New Bedford Whaling Museum, TR2022.42.

Vistas: A Journal of Art, History, Science and Culture

Copyright © 2022 New Bedford Whaling Museum

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews and certain other non-commercial used permitted by copyright law.

18 Johnny Cake Hill

New Bedford, MA 02740 www.whalingmuseum.org

President & CEO

Amanda McMullen

Design and Production

Brian Bierig, Graphic Designer

Fall/Winter 2022 | Volume 1 | Issue 1

Publisher

New Bedford Whaling Museum

Consulting Editor

Naomi Slipp

Photography

Melanie Correia

Scholarship & Publications Committee

Michael Moore (Chair)

Mary Jean Blasdale

John Bockstoce

Mary K. Bercaw-Edwards

Tim Evans

Ken Hartnett

Judy Lund

Daniela Melo

David Nelson

Victoria Pope

Editor Michael P. Dyer

Contact mdyer@whalingmuseum.org (508) 717-6837

Brian Rothschild

Tony Sapienza

Jan da Silva

Animals

Exhibit

1 | Fall/Winter 2022 Contents

..........................................................2

............................................3

...........................................................7

....................................15

: Representing

..................................................19 “From

........................................................23 Spreading the Word Digital Engagement Through Primary Source Transcription

Joe

.....................29 Lighting the Way Bringing to Light the Story of Alberta Knox

....................................................33

Foreword

Feature Articles John Jacobs at First Sight By Jonathan Schroeder

A Marriage Ahead of its Time: Robert Swain Gifford and Frances Eliot By Aili Waller

Fresh Perspectives Connection of Art and Culture By Yamilex Ramos Peguero

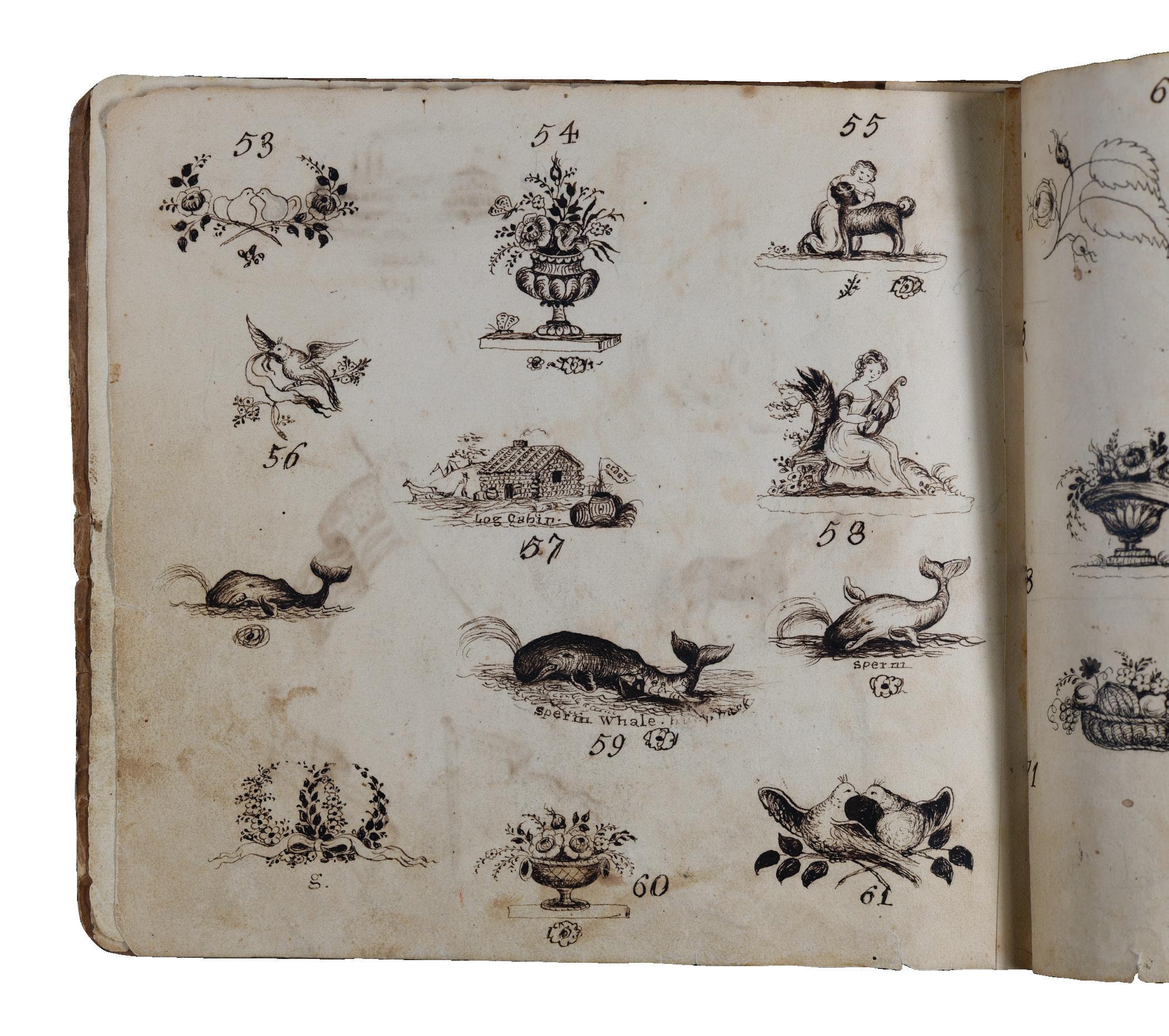

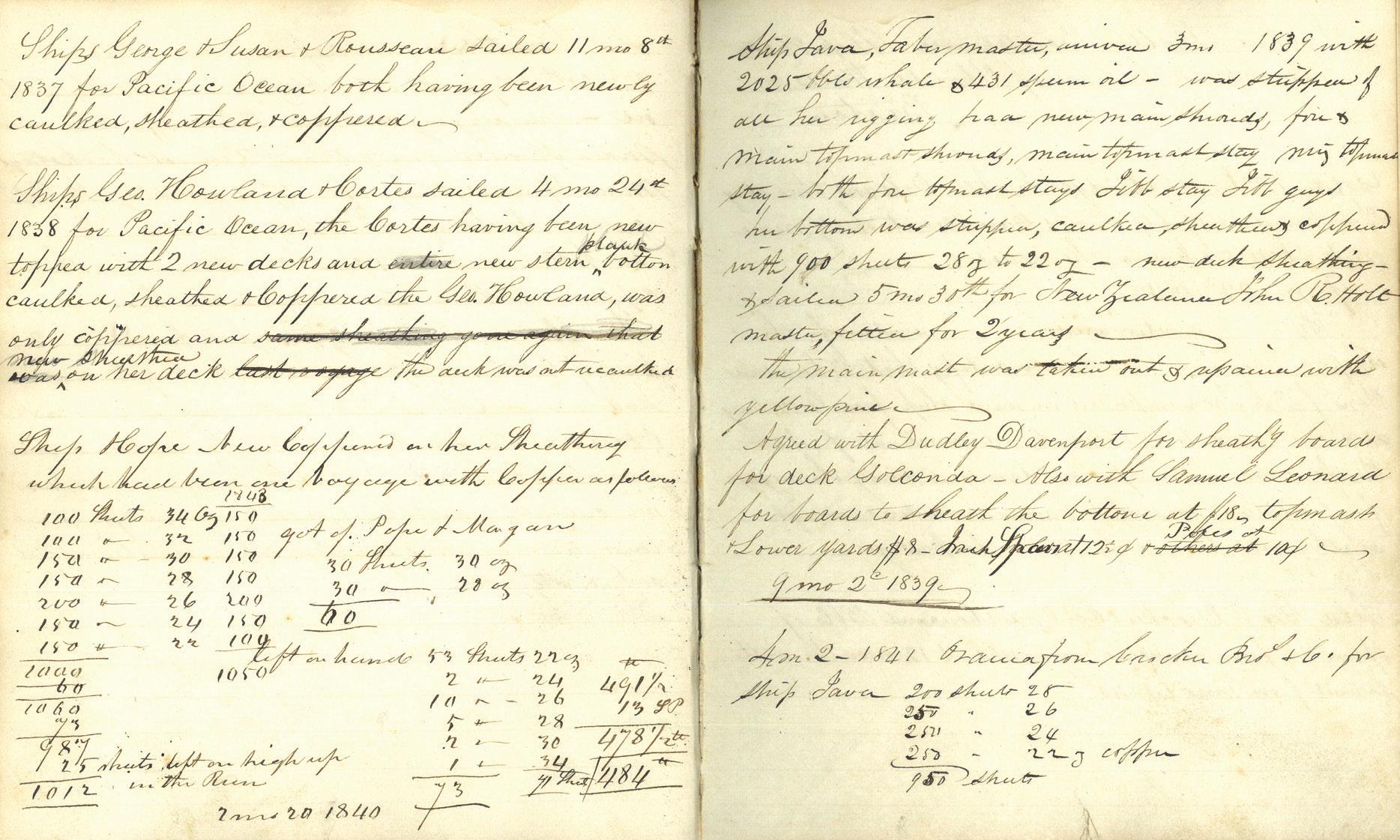

Book Talk George Howland & Sons Vessel Repair Records, 1830-1860 By Mark Procknik..................................................17 From Our Fellows Memento Matamoe

Death in Colonial Tahiti By Sienna Stevens

the Lava Flows of Aetna”: Mount Washington’s Sicilian Glass By Maria Yeye

By Michael Lapides and

Quigley

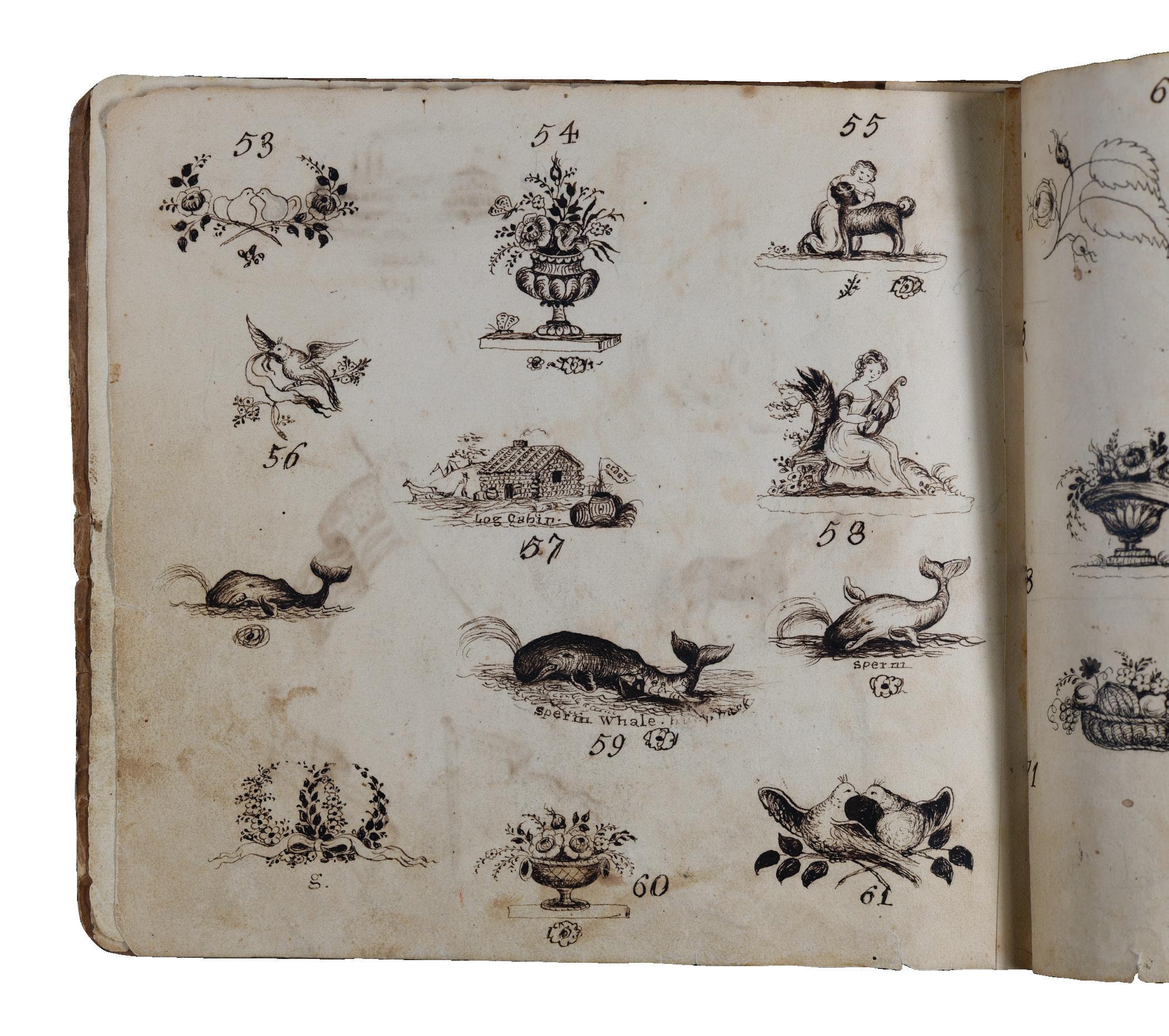

By Cathy Saunders.................................................31 All About Stuff Attribution of a Decorated Handkerchief to Local Artist Deborah Smith Taber By Emma Rocha

and Issues Marine Life in the Grand Panorama By Robert Rocha....................................................37

.................................49

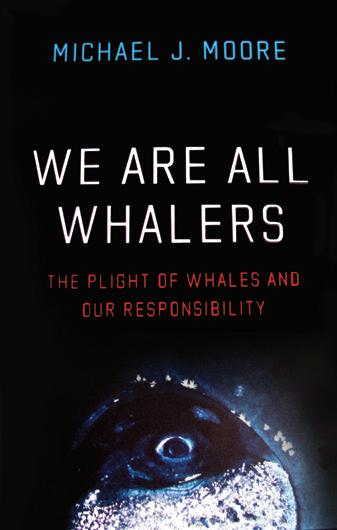

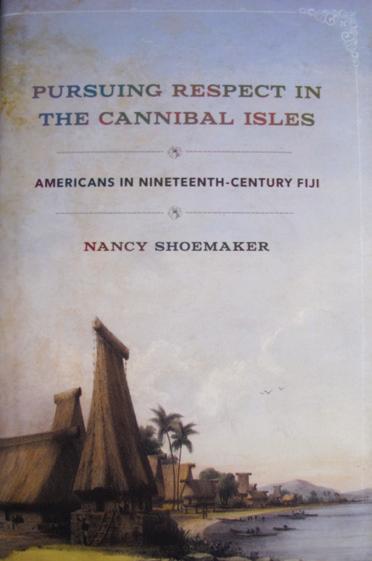

Highlights Sailing to Freedom Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad By Rachel A. Dwyer...............................................41 Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus) and the Arctic Imaginary By Melanie Correia ................................................43 Re/Framing the View: Nineteenth-Century American Landscapes By Traci Calabrese .................................................45 Book Reviews We Are All Whalers: The Plight of Whales and Our Responsibility By Brian Rothschild...............................................47 Pursuing Respect in the Cannibal Isles Americans in Nineteenth-Century Fiji By Mary K. Bercaw Edwards

...............................................50 Looking

.............................................52

2022 | Volume 1 | Issue 1

The First Reconstruction: Black Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War By David R. Nelson

Back

Fall/Winter

Foreword

There is something about having a long view. Knowing immediate steps are always important but taking in a full horizon grants us deeper perspective and balance. With the long view in mind, the New Bedford Whaling Museum has created a new offering for our members. Vistas: A Journal of Art, Science, History and Culture will be a semi-annual publication rich with features, short articles, book reviews, and museum highlights.

Consistent with the Museum’s mission to ignite learning through explorations of art, history, science and culture rooted in the stories of people, the region, and an international seaport, each issue of Vistas will reflect on our purpose and the connection of our programs, exhibitions, collections, and scholarship.

I am particularly pleased that Vistas includes contributions from staff, volunteers and docents in a range of roles at the museum. I hope you enjoy the following pages offering you the long view.

Amanda McMullen President & CEO New Bedford Whaling Museum

Amanda McMullen President & CEO New Bedford Whaling Museum

2

Re/Framing the View: Nineteenth-Century American Landscapes at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, October 28, 2022 – May 14, 2023.

John Jacobs at First Sight

By Jonathan Schroeder, Ph.D. Visiting Professor in American Studies, Brandeis University

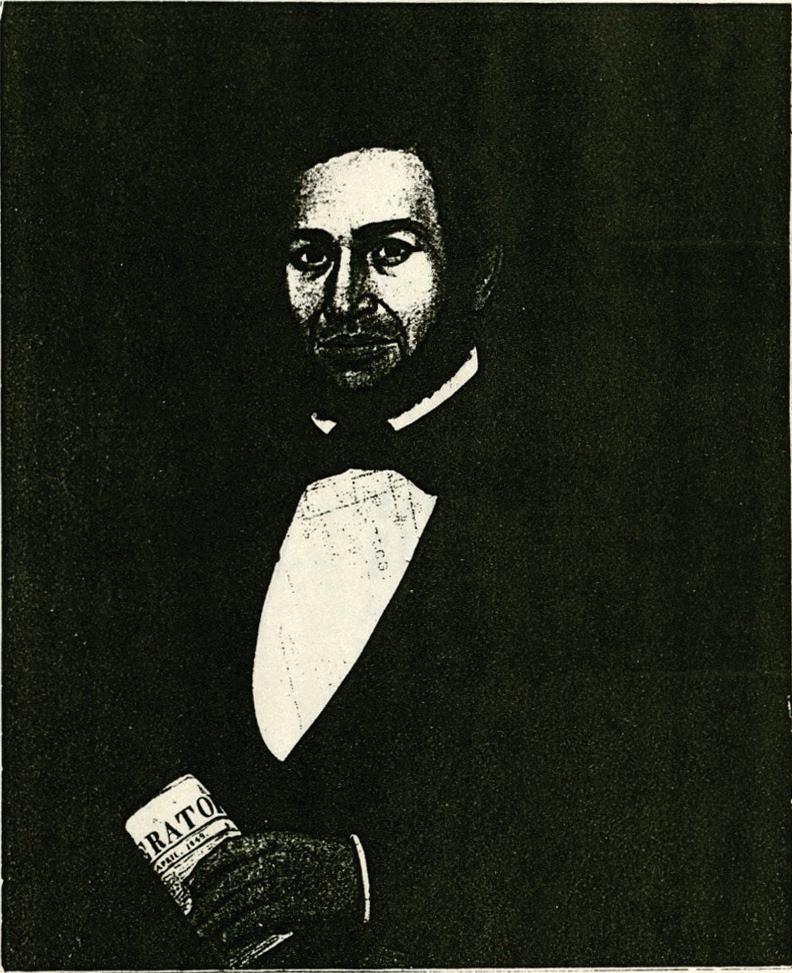

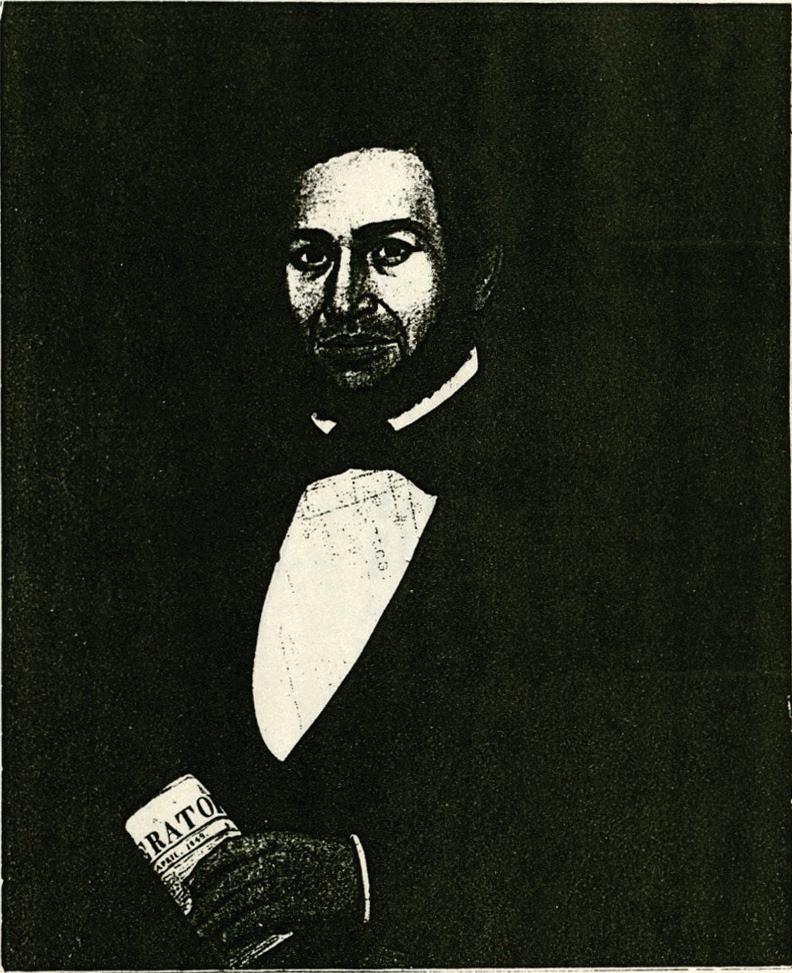

The story of how I located the portrait of John Jacobs is a long one. It begins with meeting Kathryn Grover, who probably knows more about New England African American history than anyone. When I told her I was researching the life of Harriet Jacobs’s brother, she mentioned that she had included a painting in a 1991 exhibition at the New Bedford Whaling Museum that she thought might be of John. Known then as The Man Holding the Liberator, the painting had portrait painter been loaned from the Balch Institute of Ethnic Studies, an institution that no longer exists. I was on the trail. I soon learned that the Balch had merged with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 2002, and, after emailing them, a curator named Sarah Heim sent me scans of their folder on the painting, including my first view: a photocopy of a photocopy of a photo of the painting. The loss of quality of an image between copies is known as “generation loss,” and the loss of detail here was everywhere to be seen; and yet, against the nameless, soggy, boggy, squitchy black mass of a background, John Jacobs’s face peers out, unobscured, with a smile that begets a thousand questions.

From a letter in the folder, I learned that a scholar named Juliette Tomlinson had been researching the painting in 1986-87. As the leading (and quite

possibly only) expert on a prolific nineteenth-century portrait painter named Joseph Whiting Stock, she was invited to Philadelphia and verified the artist of the painting as Stock. When I looked in Tomlinson’s research, I found that her archive is in the Frick Museum Art Reference Library, and includes a folder of documents she’d amassed on the painting. For the better part of a year, I was unable to get a scan. Then the pandemic brought the world to a standstill, closed institutions, and stalled the Frick’s move of their archives to a new building. In September 2021, however, there it was: an email from the Frick with a paperclip next to it. As the pdf and jpegs downloaded at dial-up speed, I held my breath. When I clicked on the first image, I saw a scan of the photo of the painting that was high-res and still frustratingly in black-and-white. Still, I knew I’d gotten closer to where I now knew I needed to go: the painting itself, which I had come to believe was lost somewhere in the off-site storage of the African American Museum

3 | Fall/Winter 2022

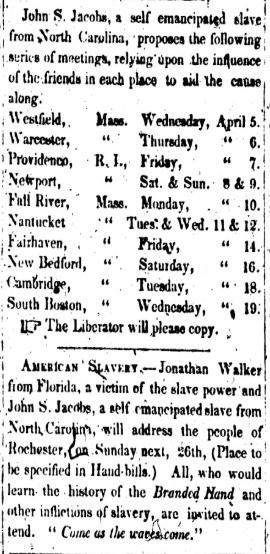

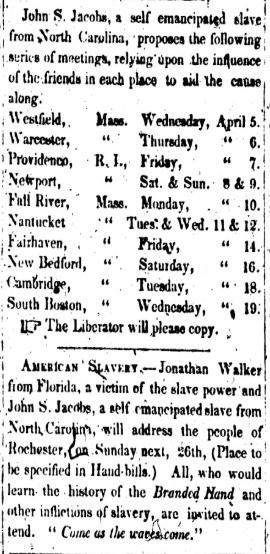

Liberator (March 24, 1848). Ad for Jacobs’s upcoming lecture dates, including his stop in New Bedford on April 16.

Feature Article

The xerox of the painting in the Frick files

of Philadelphia, which had received a donation of all of the Balch and HSP’s African American-related materials after their merger. Faced with another dead end, I looked more closely at the new image I’d just received. The sitter is in a black jacket and tie, his hand grasping an April 1848 copy of the Liberator and resting easily on the arm of a chair, and he is posed against a background with a velvet curtain tied back by a tassel—most likely the props that the artist used to help portray his male sitters as cultivated, refined, professional men—which was a big part of Stock’s stockin-trade.

Tomlinson’s Frick file actually turned out to hold the Balch curator Betty Louchheim’s research memorandum “Search for the artist and the sitter of ‘The Man Holding the Liberator.’” Louchheim had made an expansive search in 1986-1987, contacting an entire page of institutions and experts, from John Hope Franklin to Benjamin Quarles, the Schomburg Center to the National Portrait Gallery, and the Tuskegee Institute to Bowdoin College. Mostly consisting of Louchheim’s correspondence with Tomlinson, the dossier makes clear that the pair did not know very much about African American history, art, or culture. “I really can’t suggest who the subject of the portrait might be,” Tomlinson writes Louchheim, “You mentioned there was a large negro colony in New Bedford at that time so it could be anyone.” The two corresponded regularly in the months before Tomlinson’s visit to Philly, and in another letter Louchheim found it impossible to rule out Frederick Douglass as the sitter, even as she learned that in April 1848 Douglass was already at odds with William Lloyd Garrison and his paper and was already well on his way to becoming the most photographed person of the nineteenth century.

A photograph of the painting taken the moment it was unwrapped after being in storage for 30 years. Photo by Renee Altergott.

compiled a list of nine possible sitters: Henry Bibb, William Wells Brown, Douglass, Richard T. Greener, John Jones, “Leisendorff of San Francisco,” William Cooper Nell, Charles Lenox Remond, and William Whipper. The list is mostly ludicrous: Greener was four-years old in 1848, William Whipper 44 and heavyset, Henry Bibb was a Liberty party supporter and called an “enemy” of the Liberator, John Jones lived in Chicago, and William Leidesdorff in San Francisco, and Charles Lenox Remond was much skinnier, darker, and clearly balding. Douglass had already begun the North Star, which signaled his break from the orthodox principles of Garrisonianism—such as non-violence instead of violence, and moral suasion over political action—and he kept his hair “natural” in the style of Alexandre Dumas, in contrast to the sitter here, whose hair is neatly parted and, though not straightened, neatly coiffed. The scholar Sidney Kaplan’s suggestion of Nell is a good one, but it is unlikely that Nell was in New Bedford in April 1848, the date of the newspaper in the sitters’ hands, because he had moved to Rochester the previous winter and begun editing Douglass’s paper.1 Brown is also a good choice, since he was lecturing in Massachusetts in April 1848, was the highest paid agent of Garrison’s Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, and was lightskinned. However, I have not discovered any document that puts Brown in New Bedford that month and in terms of appearance, Brown does not have a beard in surviving images and was usually portrayed with a widow’s peak. So it’s probably not him.

John Jacobs was also on the payroll of the MA-SS that year. Unlike Brown, he had strong ties to New Bedford, having escaped there in 1839 and worked

From the responses she received, Louchheim

1 Check the Nell letters to see his last known whereabouts.

4

[C. M.] Gilbert Studios. Portrait of Harriet Jacobs, Washington, DC, 1894. Public domain.

on the ship Frances Henrietta of New Bedford, 1839-1843, on a sperm and right whaling voyage to the Pacific Ocean. In April 1848, when Jacobs and Jonathan Walker finished two days of lecturing in Nantucket, they took the morning steamship, Massachusetts, for the mainland. Entering New Bedford, the thirty-sixth destination on a grueling interstate tour, Jacobs must have felt a burst of emotion at the sight of his old city again, and may have even thought of it as a homecoming, since the whaling city had given him some of the protections, employment, and community that make a home possible. John saw the whaling ships, candle and ropeworks, and other markers of industry that he and his ancestors knew well, and that would later become his life. He was delighted by the chance to see old friends, escape from the “mobocratic” spirit of small-town racists, and get away from living and working in such cramped quarters with the cranky, severe Walker. And Boston and a visit to his sister and his niece and nephew were only a few days away.

In good spirits, John likely walked the hilly cobblestone streets of New Bedford’s downtown, passing the Bethel Methodist Episcopal church where Douglass had begun preaching, the signs for William Howland’s free produce store, and the Tabers’ bookstore that had probably sold him the primers and books that he had used to teach himself to read. Perhaps he fantasized while passing that one day Taber’s might sell his book, which he had already begun to work out by performing his life’s story before American audiences. Did he then walk off the street into Stock’s studio?2 When he met Stock, he found the man sitting in a recent invention called a wheelchair, which a Boston doctor had built especially for Stock, who had been paralyzed as a boy when an oxcart fell on him. Jacobs, who had seen the frontispieces of Douglass and Brown, knew the importance of self-portraiture, and perhaps he too wanted a picture that preserved the talents he had worked hard to cultivate and worked even harder to preserve during his slavery days.

The case that the sitter in this painting is John Jacobs is therefore a strong one. But it’s far from airtight and it’s important to recognize why. Most obviously, how can you determine what someone looks like when you’ve never seen them before? When the archives erase or scatter so much information? Is this the man who was described as able to pass for “Italian”? Even after you rule out the options based on pictures of famous African Americans that do survive, all you can really do is make an educated guess. So let’s hope that this is a picture of John Jacobs.

If it is, the story gets even better. A few months after I received the Frick files, I hired a research assistant in Philadelphia and asked her to pay a visit to the AAMP and see what she could turn up. Curators Dejay Duckett and Zindzi Harley found the painting right away—it wasn’t off-site at all, but in the main vault in the building. A few days later, I received high-res color photographs, which revealed details

2 “In May of 1847 Stock was in New Bedford, where he painted Captain Stephen Christian in May of that year, a work he signed and dated. Because there is no listing for him in the 1848 Springfield Directory, it may be assumed that he extended his stay in New Bedford.” Juliette Tomlinson, “A Biographical Note,” in The Paintings and Journal of Joseph Whiting Stock (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1976), xi.

5 | Fall/Winter 2022

about Jacobs and the background that had been all but invisible. A laurel pattern appears on the curtain, the tassel is shown to be tied to a column—perhaps props of Stock’s to suggest higher learning, which in the nineteenth century meant learning the classics. A few days later, I took the train down and saw the painting for myself, not because I really believed I would discover more than what the camera had already revealed, but because I wanted to be in the presence of this object that had come to play such an important part in my life.

This is a remarkable painting of a remarkable individual. John Jacobs was a Black citizen of the world who lived as a slave in North Carolina, an abolitionist in New England, and a sailor in every port of call in the world, from the first time he sailed out of New Bedford to the last voyage he took—

from London to Bangkok—in 1869-70. Jacobs was also the author of not one but two autobiographical slave narratives. Did he want to use this painting as the frontispiece for the autobiography he would later publish in Australia in 1855, The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots? The answer is unknown, but nonetheless, if this is truly John Jacobs, this painting represents one of his greatest achievements. “Negroes can never have impartial portraits at the hands of white artists,” Douglass wrote at the time. “It seems next to impossible for white men to take likenesses of black men, without most grossly exaggerating their distinctive features.”3 And yet somehow Jacobs managed to convince a hostile world to recognize him and give him respect.

6

3 Frederick Douglass, “Negro Portraits,” Liberator (April 20, 1849): 62.

Letter from Betty Louchheim of the Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies to Juliette Tomlinson concerning the identity of the sitter of the painting.

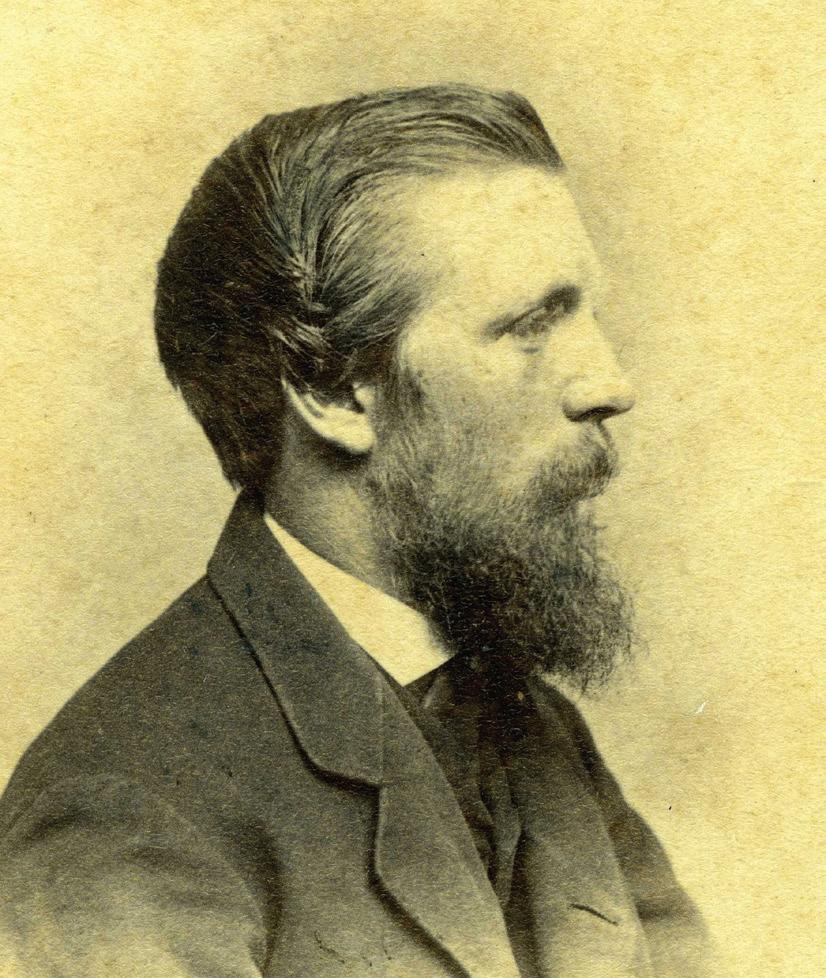

A Marriage Ahead of its Time

Robert Swain Gifford and Frances Eliot

By Aili Waller Wolf Humanities Center Undergraduate Fellow, University of Pennsylvania

Thomas Edward Mulligan White, Frances Eliot Gifford and Robert Swain Gifford painting at easels, wet plate negative, NBWM, 2000.100.3732.1

By Aili Waller Wolf Humanities Center Undergraduate Fellow, University of Pennsylvania

Thomas Edward Mulligan White, Frances Eliot Gifford and Robert Swain Gifford painting at easels, wet plate negative, NBWM, 2000.100.3732.1

Theirs was no usual Victorian marriage. The artists Robert and Fannie Gifford had a dynamic that might seem more familiar today. He was a talented but penniless artist. She was a well-connected aspiring art student. These two young people from New Bedford found each other among the chaos of New York City, developing both a professional and romantic partnership, defined by equality and respect.

Robert Swain Gifford (1840-1905) was born on Nonamesset Island, one of the Elizabeth Islands along Buzzards Bay, to a poor laboring family. His father was a fisherman and boatman along Buzzards Bay and Vineyard Sound. When Robert was three years old, his family moved to Fairhaven, where he spent his childhood. At this time, Fairhaven was home to several important artists, including Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), and William Bradford (18231892). As a teenager, Robert joined this artistic community by studying under another local artist, the local Dutch marine painter, Albert Van Beest (1820-1860).1 In an attempt to establish himself there Gifford accompanied Van Beest to New York but would shortly return to New Bedford striking up a friendship with local sculptor Walton Ricketson (1841-1923). The two would travel together in the summers of 1863 and 1864 gaining inspiration from the wild landscapes of the Adirondacks and the Bay of Fundy. When it came time to strike out on his own, Robert moved to Boston later in 1864. Then two years later, he moved to the even larger and more bustling New York City, joining a generation of upand-coming landscape painters pursuing their artistic aspirations.2

Frances “Fannie” Eliot came from a much more affluent and well-connected background than her future husband. She was born in 1844 to a prominent political family. Her father was a lawyer and congressman, serving in the US House of

1 Letter to Mr. Frothingham, 25 June 1874, folder 5, sub-series 1, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM. Albert Van Beest was an influential character to young artists in the region. In addition to R. Swain Gifford, William Bradford, C.H. Gifford, and Lemuel Eldred, all benefitted from his influence either directly or indirectly.

2 Maria Naylor, The National Academy of Design Exhibition Record, 1861-1900, (New York, New York: Kennedy Galleries, Inc., 1973), 337-340.

Representatives for over a decade.3 She grew up very comfortably in New Bedford, living in a large home with multiple servants. To put into perspective the disparate upbringings of Fannie and Robert, in 1870, the Eliot family reported having $40,000 in personal estate, while the Giffords reported only having $100 to their name.4

Fannie moved to New York City to train as an artist a few years after Robert.5 At this time an art education was one of the few types of higher education open to women. Artistic training became a way for young women to try to improve their prospects by learning skills that could help their families earn a living.6 Fannie, however, held a unique position because she was not painting out of necessity to support her family. During the Victorian era, it was unusual for a woman of Fannie’s status to be pursuing skills and knowledge outside of the home, especially the publicfacing career of an artist. Fortunately, her family’s financial support and encouragement allowed her to pursue these artistic ambitions.

By the mid-nineteenth century being a woman artist was starting to become an acceptable and respectable career aspiration. However, this progress was largely restricted to northeastern cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and New York City. In the areas where women’s art aspirations were taken seriously, the number of women artists was quite considerable. In fact, this career path was becoming so prevalent that by the 1860s, art classes taken at a seminary school or through independent study did not count as artistic training. To be considered a professional

3 “Eliot, Thomas Dawes,” History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/E/ELIOT,Thomas-Dawes-(E000106)/

4 Frances Eliott. United States Census, 1870 : New Bedford Ward 4, Bristol, Massachusetts; Roll: M593_605; p. 172B; Robert S. Gifford. United States Census, 1870 ; Census Place: New Bedford Ward 6, Bristol, Massachusetts; Roll: M593_605; Page: 234A.

5 It is not clear from the Gifford papers which exact year Fannie came to NYC. She was definitely there by 1867 but she could have come in 1866 or even 1865. (The regular Cooper Union curriculum was 4 years but students tended to leave whenever they could start getting steady artistic work)

6 April F. Marsten, Art Work: Women Artists and Democracy in Mid-Nineteenth Century New York, (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 69-70.

8

artist, a woman would need to enroll in classes at a bona fide art school.7 Again, these schools were concentrated in the northeast of the United States, the most prestigious of which being in New York City. Fannie enrolled at Cooper Union, a newly opened NYC design school offering a variety of art classes to young women.8 Her decision to immerse herself in the central, fast-paced, and rigorous New York art scene shows her dedication to becoming a professional artist rather than just a hobbyist or accomplished amateur.

Robert was also in New York, working hard to become a successful professional artist. However, he struggled to adjust to life in the big city. He constantly sent letters back to his family and friends in New Bedford lamenting how homesick he felt. He had few nice things to say about New York City, and complained frequently about how noisy, cold, and bleak, he found it to be. He often wrote of feeling profoundly lonely and lost, as he did not have the same support networks there that Fannie did. She had many well-connected relatives and family friends in the city with whom she could spend time, and she did not have to support herself financially. Robert, lacking these benefits, had to work hard to carve out a place for himself in the city. And although he often felt discouraged, he stayed committed to his career. In one letter home, he wrote:

I…wish New Bedford was a little nearer…I am working steadily in spite of the times being so hard and my reputation as an Artist…is steadily on the increase and my friends all predict for me a “brilliant future” as they are pleased to term it. I do not care particularly for the brilliant future, but I do wish to get money enough together to make mother and father comfortable in their declining years, then I may have some plans for my own comfort.9

Although he missed home, Robert did have one thing in the city to remind him of New Bedford,

7 Ibid., 69-70.

8 Robert Swain Gifford to Lydia Swain, 9 February 1868, folder 5, sub-series 2, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM.

9 Ibid., 26 January 1868.

the admired and talented art student, Fannie Eliot. Having arrived in New York a few seasons after him and being four years younger, she was behind him in her training.10 Their relationship began as a platonic mentorship of sorts as between an older brotherly figure and his young hometown advisee. He would call upon her often to catch up on New Bedford gossip and discuss their artistic ambitions. They became anchors for each other in New York—she possibly more for him than the other way around. In his letters, Robert frequently wrote about how much he enjoyed his visits with her and expressed disappointment when he did not get to see her.11

But Robert did not simply enjoy Fannie’s personal company. He also respected her work as an artist. Although women artists were not an oddity at this time in the mid-nineteenth century, the career path was still new, and male artists could be patronizing, discouraging, or even hostile toward their female colleagues. Robert however truly believed in Fannie’s talent and even took steps to further her career.

By 1869, Fannie had completed her training at Cooper Union and was embarking on her official career as an artist. In New York at the time, the chief means for an artist to prove oneself was to exhibit at an art association. Artists ran such institutions to promote public interest, show their work, receive press, and make professional connections.12 The National Academy of Design had a status higher than other art associations since it tended to set the standards of achievement in art production. The Academy’s exhibitions were considered the most central and prestigious art events of the year. Adding to the prestige was the fact that these exhibitions were juried by a council of academicians and associates.13 This meant that an artist’s work could only be

10 Although Robert’s family moved around the New Bedford area (living in Fairhaven and other neighboring towns at different points), Robert pretty much exclusively refers to New Bedford as his home in his letters.

11 Ibid., 17 November 1867.

12 Marsten, Art Work, 139-140

13 “The National Academy of Design.” National Academy Notes Including the Complete Catalogue of the Spring Exhibition, National Academy of Design, no. 4 (1884): 127–38. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/25608025

9 | Fall/Winter 2022

included in the show if it was deemed worthy by a committee of the most acclaimed and respected artists in New York City.

upon them as for the ones you named…When you are “starting” it is well to get your pictures scattered around people’s houses so that they can be seen, and to do so you have to sell when you get a chance... I don’t think you need have any doubt about their being accepted… I did not see much in them to touch over excepting two or three little places along the edges of the near trees and then your name on the small picture could hardly be seen so I took the liberty of making it more distinct…You must have worked hard to get the large picture done in time— must rest now awhile.15

These words show that Robert’s support of Fannie’s career went far beyond kind encouragement. He actively intervened, tweaking her pictures and marking up her prices. But he did not stop there. A few days later, he wrote again to Fannie:

As a driven young artist, Fannie set her sights on the National Academy of Design’s 1869 spring exhibition. She worked hard creating two pictures to submit, both landscape paintings of Cape Cod. However, before sending her pieces to the Academy, she sent them to Robert, who had been exhibiting his work at the Academy since 1863.14 After receiving her paintings, Robert wrote:

[Your paintings] looked very nice. You have certainly improved very much during the winter. They have been liked by all who have seen them. I did not think the prices too high—in fact not high enough, so I marked the small one $40.00 and the other one $75.00. Here in NY they will sell just as quick for the prices I have put

14 Naylor, Exhibition Record , 336-340.

Your pictures were accepted without any hesitation and they have been very well ‘hung’. A great number of works were rejected. Your largest picture is a little above a level with the eye—they may be put in a still better place in a day or two than is now, although the position it occupies now is good. All this is ‘contraband news’ and you must never let anyone here in New York know that you got such information before the opening of the Exhibition, as it is strictly against the rules of the Academy to let anyone know about the ‘hanging’ before ‘Varnishing day’... I hope now that the ‘ice is broken’ you will paint something for the Academy Exhibition every spring.16

During exhibitions, the walls of the Academy were filled floor to ceiling with paintings. Having one’s work hanging in the right spot could make or break a sale. Artists often complained or consoled each other about a poor placement, always blaming the hanging committee which had complete control over picture placement. Robert had ensured that Fannie’s pictures

15 Robert Swain Gifford to Frances Lincoln Eliot Gifford, 30 March 1869, folder 8, sub-series 2, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM.

16 Ibid., 9 April 1869.

10

Fig. 3. Robert Swain Gifford, Sketch of Aci Castello in a letter to Fannie Eliot, New Bedford Whaling Museum.

were ‘very well hung’. In a letter to his patron, he confided that he had lobbied the committee to hang Fannie’s pictures prominently.17 That Robert would go to such lengths for a young female colleague is astonishing and demonstrates just how much he wanted to help and also impress Fannie.

That said, Robert was not the only one who saw promise in Fannie’s work. Her pictures also received a favorable review in the New-York Tribune

Additionally, even with the art market in a downturn at the time, Fannie actually sold one of her paintings from the exhibition.18 None of this would have likely happened had Robert not ensured that her paintings (and her name) were viewed at eye level.

After this successful spring exhibition, Robert and Fannie grew closer. They began corresponding while they were apart from each other over the summer, something they had not done in previous years. Landscape artists tended to leave the city in the summer. They would go on trips to gather sketches to then bring back to their studios which would later form the basis for finished works. The summer after the 1869 exhibition, Robert traveled west to California. While away, he sent Fannie long letters describing his travels and detailing the landscape. Sometimes, he would even include sketches of the sights for her.19 One cannot help noticing that these letters,

17 Robert Swain Gifford to Lydia Swain, 4 April 1869, folder 8, subseries 2, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM.

18 Christopher Pearse Cranch to Robert Swain Gifford, 15 June 1869, folder 3, sub-series 1, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM, New Bedford, MA.

19 Robert Swain Gifford to Frances Lincoln Eliot Gifford, 10 August 1869, folder 9, sub-series 2, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM, New Bedford, MA.

which included numerous anecdotes making him seem worldly and masculine, are far different than his letters to his parents where he would talk about how sick and lonely he was.

The following summer, in 1870, Robert went abroad for the first time. Still struggling to make his career as an artist, he could not afford such a trip. Rather the voyage was bankrolled by the Tiffany family who were seeking a chaperone for their young, brash son, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933), who was looking to explore the romantically foreign landscapes of Europe and North Africa. Although he wrote many letters back home during this time, the ones for Fannie were more intimate and often include full-blown painted sketches.

In one letter, after recounting the sights, he wrote:

I must say Fannie dear that I have been homesick all day today and am very much so this evening… your photograph comforts me, I have it where I can take it out and look at it a long time before I return for the night. I have taken all the photographs of my friends and put them on the stand beside my bed, and yours is among the number so that Tiffany has no suspicion... He wonders why I can work so hard (I have many more sketches and more carefully done than before). He has never known what is at the bottom of it. He has not known what it is to love a woman…Good night my love—God bless and keep you ever Fannie, Ever yours, Robert.20

By this point it is obvious that Robert and Fannie’s relationship had grown from mutual professional respect into a real romance. However, because of

20 Ibid., 21 August 1870.

11 | Fall/Winter 2022

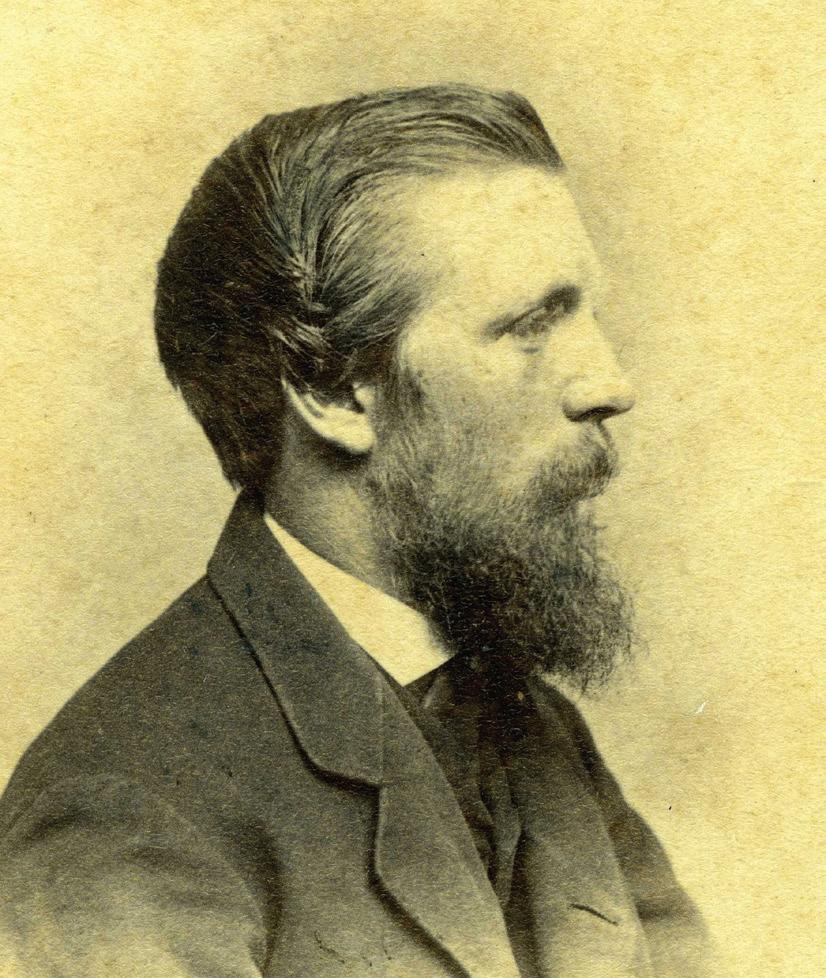

Portrait of Robert Swain Gifford, carte-de-visite. NBWM, 1981.34.23

Victorian social mores, the romance part had to be kept under wraps. They were not yet engaged and at this point could not be. According to Victorian custom, a husband was expected to support his wife’s lifestyle in a manner commensurate with her upbringing. Robert would have felt pressure to be as successful as Fannie’s father, a lawyer and congressman, in order to marry her. Thus, Robert used this trip to produce hundreds of sketches, which he hoped to parlay into more valuable art. North African scenes were unique to American audiences at the time, so they sold quicker and at higher prices.

When Robert returned to the United States, his new paintings drew great attention and success. In fact, his status and stability as an artist rose enough that by the next summer, he was engaged, and by the following summer in 1873, he was married to his love Fannie Eliot.21

At the time of the marriage, Fannie and Robert were older than usual for the time, being twenty-eight and thirtythree years old, respectively. Their union embodied equality, mutual respect, and partnership. In an age defined by the Victorian doctrine of separate spheres, where the ideal was for a wife to remain at home while the husband worked, Robert and Fannie bucked the norm. They both had creative and publicfacing careers. Robert was a staunch advocate of his wife’s work and was her partner in their professional endeavors. They made art in the company of each other, with aligned passions, ambitions, and as their day-to-day activity. Their yearly schedule took on a predictable calendar. During the summer, they would travel out of New York City to create sketches and studies. Then they would return to the city during

the colder months and use their summer portfolios to work on larger art pieces. The spring would be the season for artist receptions and exhibitions, where they could find buyers and make sales. Then this schedule would repeat itself with another set of summer travels. Although the life of a landscape artist required constant hustling and dedication, as a married couple, Robert and Fannie spent their “busyness” together.

Gurney & Son New York, Portrait of Frances Eliot, carte-de-visite, circa 1867. NBWM, 1981.34.5

In 1874 they left the United States and spent the entire year abroad. They traveled through Europe and North Africa, retracing the travels that Robert had taken with Tiffany (who, like Gifford, was now producing Moorish style art inspired from the trip). While enjoying the sights, they also worked on paintings to send back to New York City to be exhibited while they were abroad. 22 As most landscape artists confined their travels to summertime sketching trips within the northeastern United States, Robert and Fannie’s yearlong voyage was exceptional. They were an ocean away from family and friends and experiencing weeks or months’ long delays in news from home.

Fannie and Robert had each other both for company to lean on and the moral support to maintain their chosen course. They relied upon each other to weather concerns and fears about their faraway families and stay dedicated to their painting. Robert especially benefited from the emotional support of Fannie’s companionship. Before they were married, he was often lonely while working, complaining and worrying continuously to his parents. However, on

22

21 “Marriages”, The Boston Globe, June 11, 1873, Newspapers.com.

Robert Swain Gifford to Lydia Swain, 16 December 1874, folder 23, sub-series 2, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM.

12

this trip Robert’s letters home are full of joy and excitement. He wrote about how the foreignness of the sites and lifestyles excited and intrigued him, a far cry from his complaints about the ruralness of North Africa while he traveled with Tiffany.23 Now that he was with Fannie, he had a partner who was on the same path as he was and committed to the same goals.

Upon returning home their idyllic lives changed. They had children. This was a challenge then as it is now. Fannie had her first child in 1875 when she was thirty years old, which was much later than usual in the nineteenth century.24 Marrying late and putting off having children is what allowed Fannie and Robert to initially have such a modern union. But now, while Robert went to New York to paint, exhibit, and sell his art, Fannie remained home in New Bedford with the baby. This lifestyle shift was a serious adjustment for both of them. He missed her immensely and wished he did not have to be alone working to support his family, writing, “I find thoughts wandering off towards home very often now and I wish it were possible to see Fannie and our little one when evening comes.”25

Having a child to care for, Fannie no longer had the same freedom and flexibility that she did as a young working artist. She could not spend all of her time painting at her studio, networking with her artistic colleagues, or going on summer excursions into the wilderness. She now had to dedicate her time to running a household and caring for her young child.

Still, Fannie did not wholly give up her career as an artist. She continued to exhibit at least one of her art pieces at the National Academy of Design for the next couple of years.26 However, with the growing responsibility of more children, Fannie

23 Robert Swain Gifford to Gabriella Frederica Eddy White, 15 December 1874, folder 23, sub-series 2, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM.

24 Annie and Samuel Colman to Robert Swain Gifford and Frances Lincoln Eliot Gifford, 6 October 1875, folder 5, sub-series 1, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM.

25 Robert Swain Gifford to Lydia Swain, 5 December 1875, folder 24, sub-series 2, series A, sub-group 1, Mss 12, NBWM.

26 Naylor, Exhibition Record , 336-337.

simply had less time to paint. During the 1880s, she only exhibited her work twice at the Academy.27 By the end of this decade Fannie had given birth to seven children (tragically only her five daughters lived to adulthood). She did not seem to be resentful about giving up her career. Instead, her priorities had shifted from herself and her art to her family and her children. Even when she had to spend most of her time with domestic duties, she did not completely give up her art. For example, in 1885, she and Robert both contributed to Theodore Roosevelt’s first book, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman. 28 Robert’s illustrations were of western landscapes, while Fannie sketched various kinds of birds, one of her specialties.

Robert and Fannie were married for thirty-two years. He died in 1905, and she died in 1931. Throughout their lives, they remained each other’s anchors, sharing their love of art and their family. Their letters to each other are a lasting legacy of their courtship and marriage. It is particularly fitting that this testament to this union ahead of its time remains in New Bedford, the place that anchored them to each other.

27 Ibid., 336-337.

28 Theodore Roosevelt, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman (New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1885), Bartleby.com, 1998. www. bartleby.com/52/.

13 | Fall/Winter 2022

Fannie and Robert had each other both for company to lean on and the moral support to maintain their chosen course.

14

Robert Swain Gifford and Frances Eliot Gifford on porch of their Nonquitt house with baby, stereograph, NBWM, 2000.100.1592.

Fresh Perspectives

Connection of Art and Culture

By Yamilex Ramos Peguero Visitor Experience Associate, New Bedford Whaling Museum

By Yamilex Ramos Peguero Visitor Experience Associate, New Bedford Whaling Museum

My name is Yamilex Ramos Peguero and I have worked at the New Bedford Whaling Museum since 2014. Throughout the years, I have worked in different departments, participated in a variety of workshops and trainings, and have served on multiple committees. By working with staff members from all departments, I have gained many skills that have made my experience at the museum memorable. I have seen numerous exhibits come and go; some have left a meaningful impact in my life and others have just been one of many. From each exhibit, I have learned something new and valuable. One subject that the museum

has helped me acquire a new appreciation for is art. Two of the artists who have been the most impactful during my time here are Alison Wells and Domingos Rebêlo. In the Neighborhood, an exhibit by Alison Wells continues to be one of my top three favorite exhibits. Alison Wells draws from her Caribbean culture as inspiration for her artwork. Another memorable exhibit is The Azorean Spirit: The Art of Domingos Rebêlo. Rebêlo’s work displays the Azores, its beautiful culture and community.

Being from the Dominican Republic in the Caribbean helped me connect with Alison Wells

15 | Fall/Winter 2022

Domingos Rebêlo, Tryptico Açoriano (estudo)/Azorean Triptych (study), circa 1920s. On loan to The New Bedford Whaling Museum courtesy of a private collector.

from the moment I met her. I remember walking into the Braitmayer Gallery and seeing these beautiful, colorful, and vibrant paintings. I was immediately drawn to them and eager to learn more about them. There was Alison, who was just as eager to talk about them. We talked about how she moved to New Bedford sorely for school, then she ended up falling in love with the city, its culture, and everything about the community. Walking alone into Braitmayer that day, turned into two people talking about, being passionate about their culture and loving their community.

I later had the pleasure of meeting Jorge Rebêlo, guest curator and grandson of the late artist Domingos Rebêlo. Immediately upon meeting he greeted me warmly, as if we had known each other for years. I also found that same sense of familiarity in his grandfather’s art. There are scenes that remind me of my own Dominican culture. His art connected me so deeply with the community of the Azores, in a way that I might not have gotten to experience otherwise.

The two exhibits highlighted above, have been a learning stone for me personally, and I am sure, these have served the same purpose for others. Learning about different cultures through art, gives you a new appreciation for the interpersonal connections that can be made within our community. Art is a medium that breaks down barriers. It allows people to connect with each other, despite gender, race, ethnicity, religion, and age. I am fortune to work for a place that is accessible to the community. The New Bedford Whaling Museum, a place where community members feel represented and are encouraged to explore art, history, science, and culture.

16

Learning about different cultures through art, gives you a new appreciation for the interpersonal connections that can be made within our community.

Alison Wells, In the Neighborhood, 2020. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas. Gift of Michael and Michelle Kelly. NBWM# 2021.53.

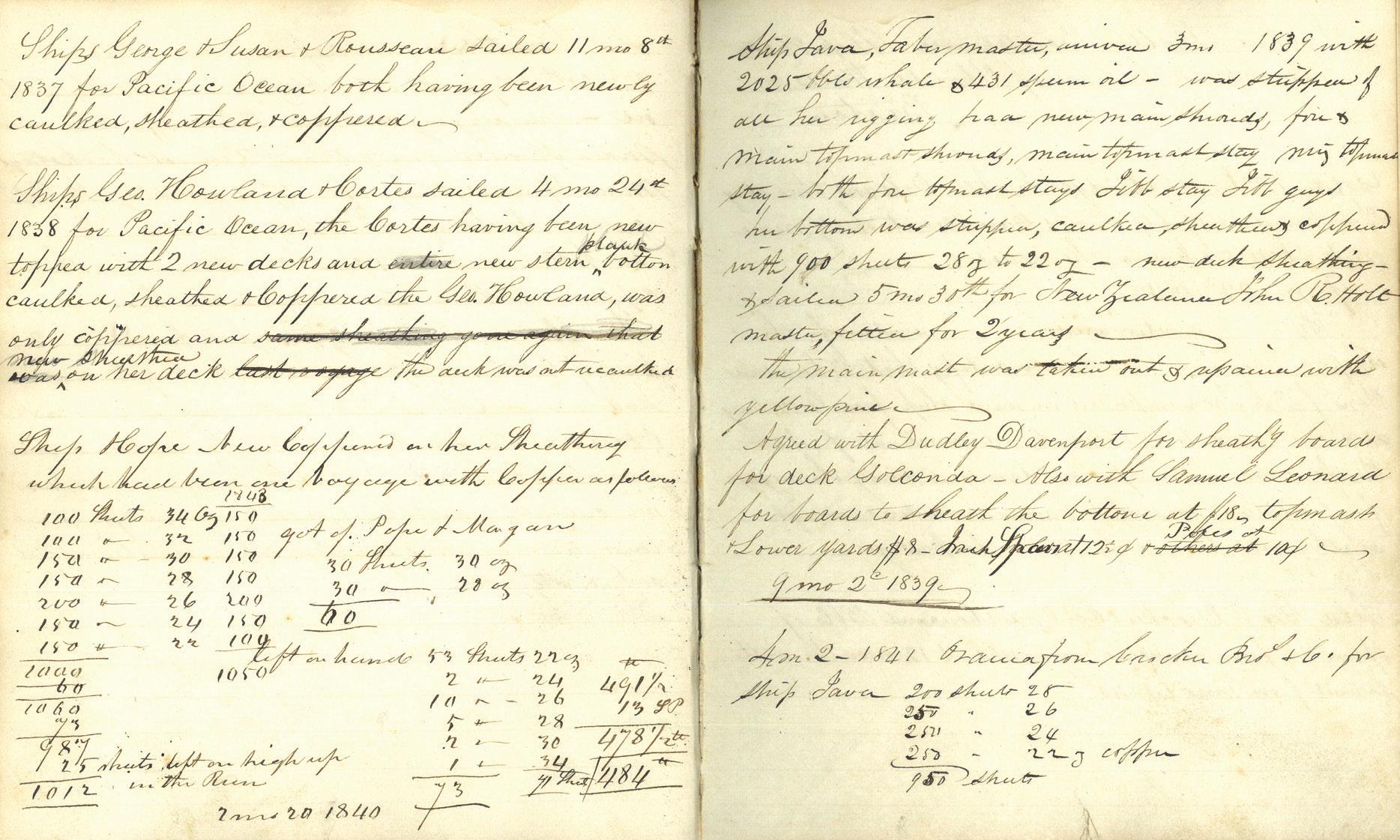

George Howland & Sons

Vessel Repair Records, 1830-1860

By Mark Procknik, Librarian, New Bedford Whaling Museum

The business records of George Howland, Sr., and his sons (1797-1890), clearly demonstrate significant overlaps between the region’s whaling history, and the larger regional history in which the industry flourished. The New Bedford Whaling Museum library holds several collections related to the Howland family, most notably the line sired by George Howland Sr. (1781-1852). Howland, a proud Quaker from Acushnet, MA, with deep family roots in Dartmouth and Westport dating back to the 1670s, began his career in 1797 working in the office of noted whaling merchant William Rotch Jr. (1759-1850). Rotch, whose father William and grandfather, Joseph, pioneered colonial sperm whaling, moved from Nantucket Island to mainland New Bedford in 1787.1 Dealing in products derived from the sperm whale including refined sperm oil and spermaceti candles, William Rotch Jr., brought the knowledge he gained working with his father, to New Bedford where he established his own firm of William Rotch Jr. & Sons with his sons William Rodman (1788-1860), Joseph (1790-1839), and Thomas (1791-1840). All three sons would pursue careers in various aspects of New Bedford’s whaling industry, establishing the firms of William R. Rotch & Company and the Rotch Wharf Company, in addition to the Rotch Candle House and New Bedford Cordage Company.

Howland’s experience gained in the Rotch counting house undoubtedly benefitted him when establishing his own firm, George Howland &

1 Strong relations between the Quaker communities on Cape Cod, Nantucket, and the Old Dartmouth region funneled maritime skills to the dynamic seaports of the whale fishery. Joseph Rotch, along with Joseph Russell of Dartmouth, built the seaport at Bedford Village in 1765 specifically to pursue the whaling industry.

Sons, contemporaneous with the Rotch family dynasty. Unlike the Nantucket-oriented Rotches, who were primarily sperm whalers, the Howlands diversified their business strategy to include whale oil and whale bone as well as sperm oil. This was a hallmark of the most successful New Bedford firms starting in the 1820s and continuing for decades. His sons George Jr. (1806-1892) and Matthew (1814-1884), continued this business model after their father’s death in 1852. The firm owned and managed several famous nineteenth century New Bedford merchant and whaling vessels, including the ships Cortes, George and Susan, George Howland, Hope, Java, Rousseau and Ann Alexander. It was a successful fleet.

The NBWM collection, Mss 7, Business Records of George Howland & Sons, contains many financial accounts, ledgers, and records documenting this fleet. One curious memorandum book dating from 1830 to 1862 identifies brief descriptions of vessel repairs between voyages. Like other such volumes it includes various information such as journal extracts, spar dimensions, and “whales seen and taken” charts. These sorts of books contained the accrued knowledge that whaling agents depended upon in strategizing their voyages. This particular volume is a unique and valuable synopsis of the intervoyage preparations necessary to keep the ships in working trim. Taken in combination with the 18371839 Cash Book – a particularly community-based affair comes into focus including such little-known names as laborers, truckers, night watchmen, and the like. Dozens of people worked on these ships and they all appear by name in the Cash Account Book. In November 1837, for instance, Howland’s account book records that the George and Susan

17 | Fall/Winter 2022

Book Talk

and the Rousseau sailed for the Pacific Ocean after being newly caulked, sheathed, and coppered. This work would have been done at Howland’s wharf, located north of the bridge between Rodman’s and Wilcox’s wharves and the people who did the work were not necessarily specialized craftsmen. Almost all of them appear in the New Bedford City Directories as “laborers”.

Included is a note affirming that Howland purchased copper from the local whaling firm of Pope & Morgan in order to outfit the Hope’s 1840 voyage.2 This suggests that various firms had various business dealings of interest to the maritime community at large. Dealing with intermediaries drove up the costs, but that was the price of doing business. In 1839, Howland likewise describes repairing the Java, recording that the ship was re-rigged, caulked, sheathed, and coppered for a voyage to New Zealand in May. In November similar repairs were made to the Golconda for a December voyage, primarily by sheathing the deck, but the masts received some attention as well.

2 The New Bedford Copper Company incorporated in 1860 would provide the New Bedford whaling fleet directly with sheathing.

While these entries from Howland & Sons’ account books offer a window into the work required to outfit and maintain a fleet of seaworthy vessels, they also provide a glimpse into the business dealings of the nineteenth century New Bedford seaport. While succinctly documenting the necessary outfitting work for his various vessels, also noted are many local businesses and merchants working in New Bedford at the time, including Pope & Morgan, Dudley Davenport, and Samuel Leonard. Pope & Morgan ran a commission merchant business out of Rotch Square. Dudley Davenport ran a housewright business but was also a dealer in lumber and coal out of South Water Street, while Samuel Leonard worked as a lumber and oil dealer out of Rotch’s South Wharf. All three operated on the nineteenth century waterfront and offered valuable services for all New Bedford residents looking for copper, lumber, and coal. George Howland employed the services and wares offered by these local waterfront businesses in order to sustain his growing business as a whaling agent in a growing industry.

George Howland & Sons Memorandum Book, 1830-1861. Mss 7, S-G 1, Ser. A, S-S 5, Vol. 1. NBWM.

18

Memento Matamoe : Representing Death in Colonial Tahiti

By Sienna Stevens 2022 Summer Research and Interpretation Curatorial Fellow, New Bedford Whaling Museum

As the 2022 Research and Interpretation Fellow, I have focused on evolving Western ideas of Oceania, and found, within the great diversity of the Museum’s collection of such materials and objects, pieces that provoked broader questions. One such piece is a print, an engraving, by John Webber (1751-1793), titled The Body of Tee, a Chief, as Preserved after Death, in Otaheite. Webber was the official artist of Captain James Cook’s third voyage to the Pacific and though the print is much older I immediately associated it with Paul Gauguin’s famous 1892 painting Arii Matamoe (The Royal End) held at the Getty Museum.

I felt a connection emerge between these works with their parallel (and sensational) subject matter. Each image captured death in Tahiti in visual vignettes. Gauguin’s painting, created over a century after Webber’s, spoke to death and dying from the vantage point of an artist who occupied a space within the expanded French colonial influence in Tahiti, a space accompanied by a sharp shift in cultural governance. Webber’s print ostensibly served as a documentary illustration from a period of the earliest contact between Western mariners and the peoples of Oceania, long before actual colonial processes overtook the region. Comparing the two art works

19 | Fall/Winter 2022

William Bryne after John Webber, “The Body of Tee, a Chief, as Preserved after Death, in Otaheite,” c. 1784, British engraving, etching and stipple on cream laid paper. NBWM, 00.131.98

From

Our Fellows

offers valuable insights into how Tahitian culture, in this case funerary practices, and perhaps something more, has been perceived, not only by the audiences for the art, but by the artists themselves.

Webber’s Body of Tee emerged in 1777 from Cook’s third and final voyage (1776-1778). It documents the intricate process of preserving the bodies of deceased chiefs in 18th-century Tahiti. One seaman on the voyage wrote:

“The body [of Tee] was entire in every part; putrefaction seemed hardly to be begun: and not the least disagreeable smell proceeded from it; though this is one of the hottest climates, and Tee had been dead above four months…On enquiry [sic] into the method of thus preserving their dead bodies, we were informed, that soon after they are dead, they are disemboweled, by drawing out the intestines and other viscera; after which the whole cavity is stuffed with cloth; that, when any moisture appeared, it was immediately dried up, and the bodies rubbed all over with perfumed coca-nut oil, which, frequently repeated, preserved them several months after which they molder away gradually.”1

Funerary practices vary greatly across cultures. For Western cultures, common interment practices included traditional burials in rural cemeteries, memorial parks, or mausoleums. Far less common was the Tahitian tradition of preserving important bodies for months after death. To the common eighteenth-century viewer of this image, the idea of this level of embalming may have seemed truly alien, and in the case of Webber’s illustration, affected an early influence upon the popular perceptions of Tahitian cultural customs in the West.2

Akin to corpse embalming practiced by the Ancient Egyptians, the intricate process of preparation for a

1Alex Hogg, Complete Narratives of the Following Most Important Journals: A New, Authentic, Entertaining, Instructive, Full, and Complete Historical Account of the Whole of Captain Cook’s First, Second, Third and Last Voyages. (England, 1794), 492.

2 Nineteenth century travelers in the American west made note of a similar use of scaffolds and “burial trees” by the natives of the Great Plains as did observers of Australian Aborigine burial customs.

long-term view of the body was sacred and reserved for those of high status.3 Cook and Chief Tee had actually met in 1773, during Cook’s second voyage on the HMS Resolution. 4 Warmly received by Tee, Cook and his crew created a rapport with the people of Tahiti, wishing to ensure that any return visits to the island would be fruitful and friendly.5

Webber thus captured a moment of funerary reverence, perhaps particularly poignant, given the established relationship between the voyagers and the islanders, with the embalmed corpse respectfully placed within a landscape of verdure.

As decades passed, however, Webber’s sense of documentary wonder with encountering new cultures was replaced with another viewpoint entirely. Paul Gauguin’s (1848-1903) fascination with “primitive” cultures led him to escape the lifestyle of French society in the 1890s for Tahiti.6 While there, he documented his experiences in journals and on canvas, and many art historians have pointed out that much of his writings and scenes seem carefully constructed or even plagiarized.7 He returned to France between the years of 1893 and 1895, venturing back to Tahiti once he had earned the funding for the voyage.8 He would later marry a Tahitian vahine (child bride) named Teha’amana, which benefited him by legitimizing his continued presence in the Pacific.9

Arii Matamoe (The Royal End), is speculated to be an allusion to the death of King Pōmare V (1839-

3 Douglas L. Oliver, “The Individual: From Conception to Afterlife.” in Ancient Tahitian Society. (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1974), 504.

4 Hogg, Complete Narratives, 150.

5 Ibid., 150.

6 Ziva Amishai-Maisels, “Gauguin’s Early Tahitian Idols.”, (The Art Bulletin, vol. 60, no. 2, 1978), 331

7 Ibid, 333.

8 Victoria Charles, Paul Gauguin. (United Kingdom: Parkstone International, 2011), 92.

9 Elizabeth C. Childs, “Taking Back Teha’amana: Feminist Interventions in Gauguin’s Legacy,” in Gauguin’s Challenge: New Perspectives After Postmodernism. (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2018), 232. “Vahine” literally translates to “woman” in Tahitian, however, in discussions of Gauguin’s life there the word is associated with the youth of his wife.

20

1891), the last ruling monarch of Tahiti before the French seized control in 1880.10 Contrary to Gauguin’s depiction, Pōmare had in fact not been beheaded. He had actually died of alcoholism within a decade of ceding his rule. Decapitation was not a Tahitian standard of burial.11 Art historians have instead pointed to the body of Gauguin’s work featuring biblical beheadings, as well as his familiarity with France’s prolific use of the guillotine as capital punishment.12 This completely fabricated scene of a royal death may play instead into the creation of the perceived exoticism of Tahitian mourning rituals, which had served to fascinate European voyagers since the first Cook voyage.

The garish nature of a beheading visualized horrors of the most unimaginable kind. The bright color palette evoking “tropical’’ lighting contrasts with the darkness of skin atop a white pillow in the interior scene. Illuminating the sunshine-yellow of the

10 Scott C. Allen, “A Pretty Piece of Painting’: Gauguin’s “Arii Matamoe.” (Getty Research Journal, no. 4, 2012), 81.

11 Richard R. Bretell, On Modern Beauty: Three Paintings by Manet, Gauguin, and Cézanne. (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2019), 60.

12 Ibid., 69.

outside world, Gauguin’s shadows in muted browns and blacks evoke a sense of day and night. The faint writing of the words Arii (nobility) and Matamoe (“sleeping eyes,” or death) emerges from the wall behind the decapitated head, evoking the pensive saying Et in Arcadia Ego (“Even in peace, there is death”).13

The two scenes share a particular focus on the openair architecture of Oceania. This was of special interest to Europeans, who seemed fascinated by the tropical climate that permitted such a way of life.14 Where Webber’s sweeping survey of a peaceful valley chosen for the purpose of displaying a chief’s corpse highlights the splendor of the natural beauty of Tahiti, Gauguin’s focus features a consideration of appropriate places to mourn and how far Tahitians are removed from Western sensibilities.

Furthermore, the two depictions are a uniquely Western binary commentary on royal or chiefly death, in particular. The death of commoners has

13 Scott C. Allen, “A Pretty Piece of Painting’: Gauguin’s “Arii Matamoe.” (Getty Research Journal, no. 4, 2012), 75.

14 Westenra L. Sambon, “Acclimatization of Europeans in Tropical Lands.” (The Geographical Journal vol. 12, no. 6, 1898), 589.

21 | Fall/Winter 2022

Paul Gauguin (French, 1848-1903), Arii Matamoe (The Royal End), 1892, Tahiti, oil on coarse fabric. Image courtesy of the Getty Center, Los Angeles, California, 2008.5

historically been much more simplistic, although rich traditions of reverence for every social class has been documented.15 Presumably, the death of Tee had been visually recorded as it was witnessed.16 If the crew of the HMS Resolution had stumbled upon a commoner’s death, it may likely have been the scene that was recorded instead. For Gauguin though, an active choice to fabricate a death scenario that never occurred, and alluding to it as being the death of Pōmare predicates an agenda to emphasize perceived ideas of racial and cultural difference between the West and Pacific cultures, Tahiti in particular.

15 Douglas L. Oliver, “The Individual: From Conception to Afterlife.” in Ancient Tahitian Society. (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1974), 507.

16 Ibid., 510.

Reflecting on these disparate images allows viewers to contextualize a complex history. Political and cultural structures of Tahiti changed radically in the century after Cook, as Western influences permeated the entire region of Oceania. Can we quantify just how powerful early imagery of cultural practices was for those who saw it? Is it possible to understand just how impactful late nineteenth-century works were on effecting the actions of governments, and other effectors of change like missionaries, tourists, indeed, people like Gauguin himself? The work of Pacific historians, anthropologists, and cultural practitioners continues to probe at the heart of this conundrum. What spoke to me, in the lines and brushstrokes, was a chance to bridge two centuries and contemplate how imagery can dictate the reception of cultural customs–real or imagined.

22

Funerary practices vary greatly across cultures. For Western cultures, common interment practices included traditional burials in rural cemeteries, memorial parks, or mausoleums.

Far less common was the Tahitian tradition of preserving important bodies for months after death.

“From the Lava Flows of Aetna”

Mount Washington’s Sicilian Glass

By Maria Yeye 2022 Summer Glass Curatorial Fellow New Bedford Whaling Museum

By Maria Yeye 2022 Summer Glass Curatorial Fellow New Bedford Whaling Museum

Mount Washington Glass Company. Sicilian, or Lava glass vase, circa 1878-1880. NBWM collection, 1989.65

Located in New Bedford, Mount Washington Glass Company (1876-1894) is among the most revered manufacturers of “art glass,” a decorated and often highly-colored glass produced during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Sicilian or ‘Lava’ Glass is sometimes identified as Mount Washington’s first art glass. Mount Washington, however, produced other types of decorated wares which preceded their renowned Sicilian glass. The firm’s first foray into art glass included Iridescent or “Rainbow” glass, for which the firm was the first in the U.S. to receive a process patent. Enamel painted Opal glass, typically acid treated to give the surface a matte finish, was another specialized production. The Sicilian glass though, was the first ware produced by the firm to receive a patent by implementing their own experimental techniques. The risks they took in making original wares really came to define Mount Washington as “tastemakers” of the period. Other producers of art glass in the country included the New England Glass Company and the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company.

During the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876, Mount Washington was among the exhibitors. With elaborate, custom created displays, they exhibited their decorative glass wares, cut glass, and their specialty, glass chandeliers. It was likely at this Centennial Exhibition that Frederick S. Shirley (1841-1908), the firm’s superintendent and visionary leader, likely first saw the newly introduced ‘lustered’ glass produced by Austrian firm Lobmeyr.1 Lobmeyr may also have displayed another influential ware. Their “Bronze Glass”, created from a technique popularized from the English firm Thomas Webb and Sons, may well have served as an inspiration for Mount Washington Sicilian glass.2 Two years later, Mount Washington began producing their own version of this glass using green or sometimes blue glass coated with the patented “lustre finish”, advertised as being sold alongside imported bronze glassware. Shirley patented the process for producing a finish called lustered or iridescent and received the patent in 1878. Very few positively identified Mount

1 Lobmyer was a Vienna based firm begun in 1823, and were established leaders in engraved glass and enameled glass.

2 Hajdamach, Charles R. 1993. British glass: 1800-1914. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 116.

Washington wares featuring this finish survive today.

Shortly after the Centennial, on June 18, 1878, Shirley received a patent for his Sicilian glass, which, “relates to an improvement in the manufacture of glass… adding lava, or volcanic slag in suitable proportions, so as to adapt it, especially for the imitation of antique ceramics, and cheap reproductions of the works of ancient masters.”3 The shapes were inspired by ancient wares and supposedly contained volcanic material taken right from the lava flows of Mount Etna. He advertised it as, ‘“the novel Sicilian Ware… from the Lava flows of Aetna.”’4 It was a solid example of marketing, defining the company as tastemakers, as during the 1870’s both the lost city of Troy in Asia Minor, and Mount Etna on the eastern coast of Sicily were being excavated and special attention paid to the newly unearthed artifacts found there. What could be more appealing than taking home an actual piece of flowing lava to display in one’s home? The advertisement for “The New Bronze Glass, in the Original Grotesque Forms” ran from November 21, 1878, to January 2, 1879.5

The inspiration for Sicilian glass, like the majority of art glass that Mount Washington manufactured, came from porcelain and other ceramics. These imitations gave upper-middle-class consumers a way to keep pace with trends of traveling and collecting, even if they didn’t have the means to do so. Various aspects of the Sicilian wares were inspired by ancient decorative objects: the asymmetric pieces of glass that were applied to the outside mimic the ‘spangled’ glass produced by Ancient Romans; the shapes of the vases mimic those amphorae of Greek antiquity. The dark color, while imitating cooled Lava and allowing consumers to supposedly take home a piece of Mount Aetna herself, could have also been a

3 Wilson, Kenneth M. 2005. Mt. Washington and Pairpoint Glass: Encompassing the History of the Mt. Washington Glass Works and Its Successors, the Pairpoint Companies. 1 1. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 111.

4 Ibid., 111

5 Ibid., 111. The advertisement ran in a serial called Crockery and Glass Journal (1875-1961).

24

form of imitation of Attic vases,6 which were coveted, but far too expensive for the typical consumer. The trend for black wares was revived during the late 18th century, when Josiah Wedgewood and Sons produced a black stoneware called Black Basalt Ware in imitation of a newly discovered Roman vase.7

Although Sicilian Glass never reached the success achieved by future art glasses introduced by Mount Washington, like their Rose Amber or Burmese

6 Attic Vases are a style of clay vase originating in Ancient Greece. They typically feature painted red figures on a black background and portray an array of scenes ranging from daily life, important social rituals, and mythology.

7 Revi, Albert Christian. 1967. Nineteenth Century Glass: Its Genesis and Development. Exton Pa: Schiffer, 238.

glass, more patents were filed for it than any other type of glass produced by the firm. Shirley filed three separate patents between 1878 to 1879. The first patent pertained to the chemical make-up for the Lava component, the second to shapes and decoration. None of those listed on the patent have proof of production. The third patent received in 1878 for ‘Lava flanges made in imitation of bamboo or cane,’ were put into production but used Opal glass. Furthermore, as exemplified by the rare Pink Sicilian glass, for reasons unknown, but perhaps in an attempt to reignite interest in the ware, some shades of pink Sicilian glass were produced, a marked deviation from the concept of adding Lava altogether, but resulting in a memorable ware.

25 | Fall/Winter 2022

The inspiration for Sicilian glass, like the majority of art glass that Mount Washington manufactured, came from porcelain and other ceramics. These imitations gave upper-middle-class consumers a way to keep pace with trends of traveling and collecting, even if they didn’t have the means to do so.

26

Mount Washington Glass Company. Pink Sicilian vase, circa 1878-1880. NBWM Collection, 2003.81.

27 | Fall/Winter 2022

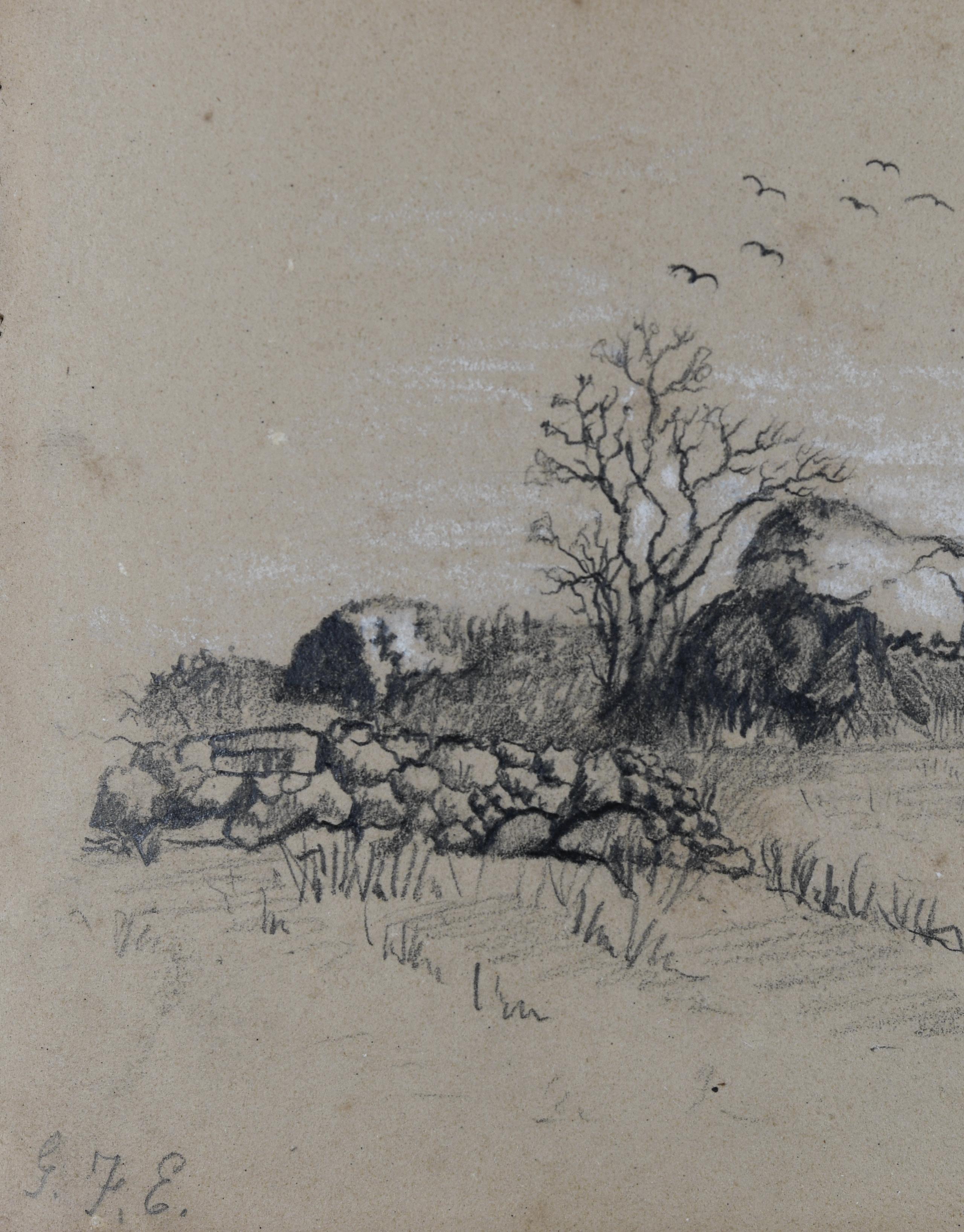

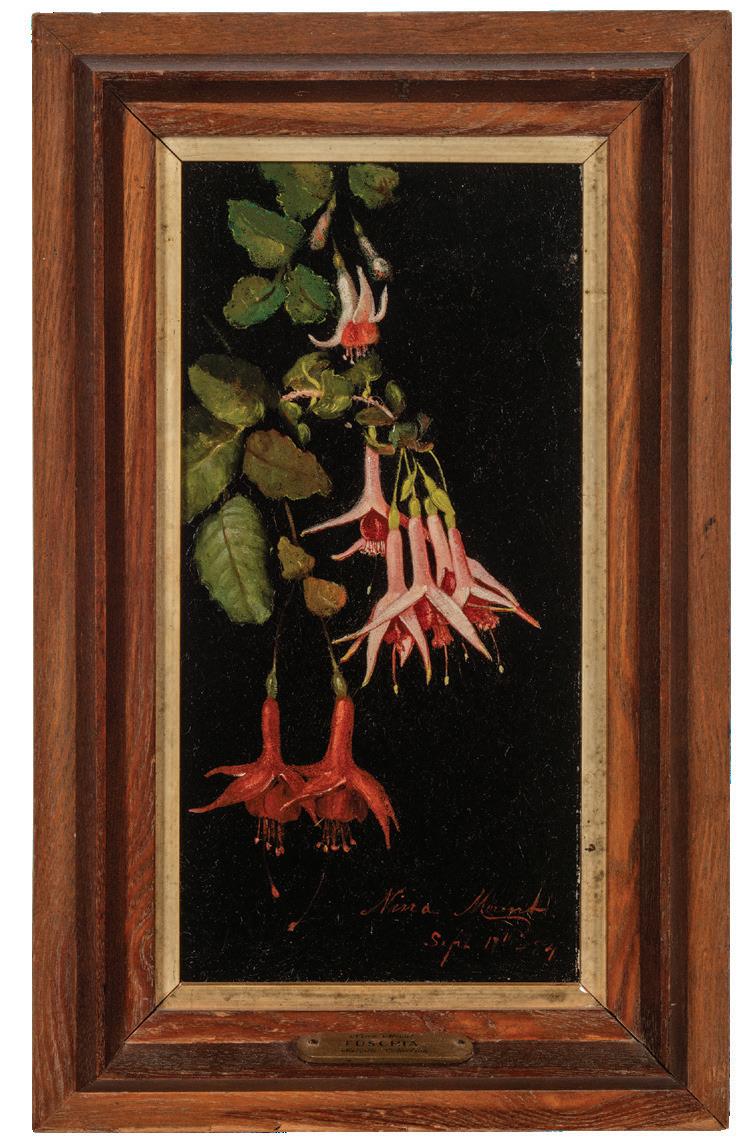

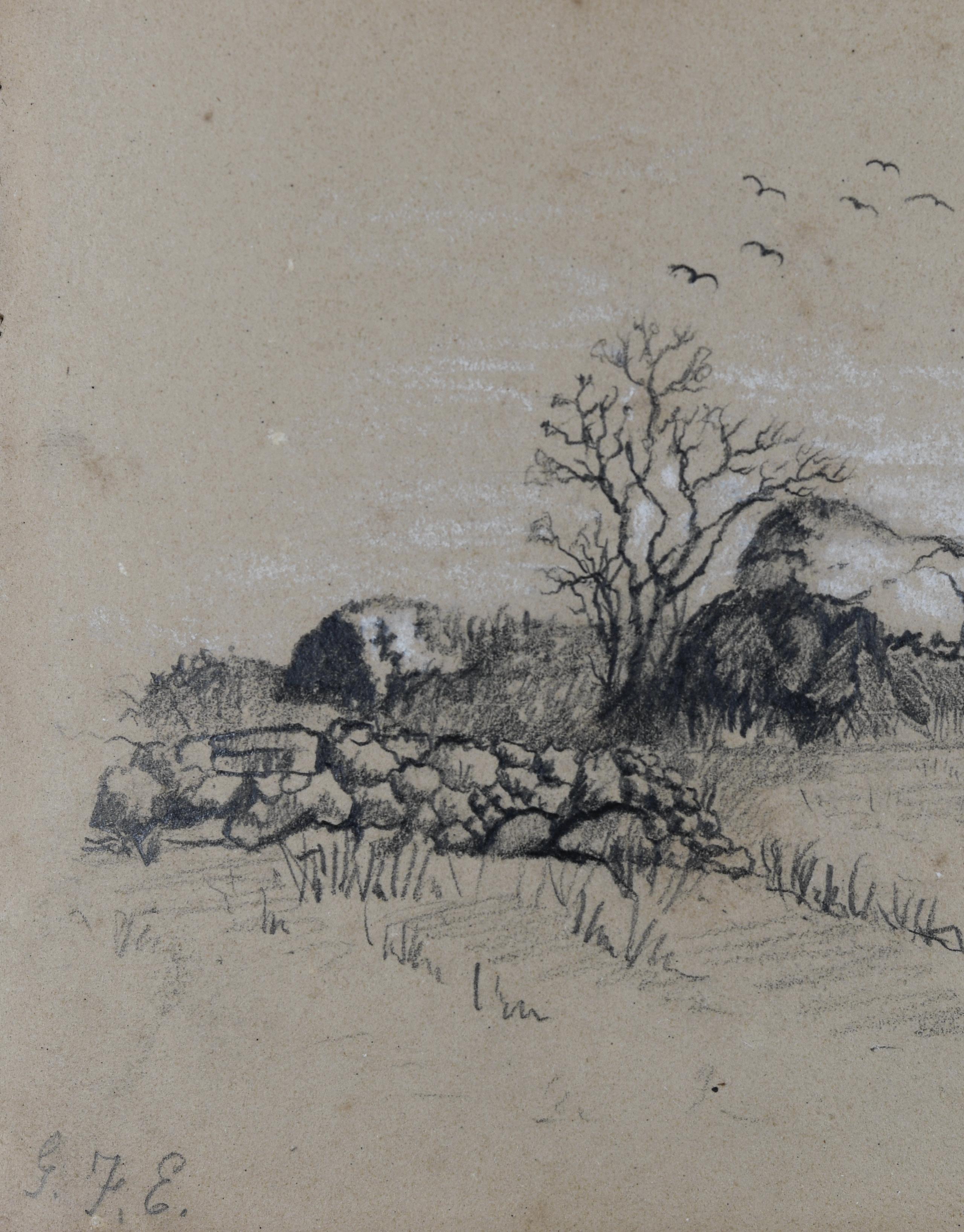

Frances Fannie Eliot Gifford (1844-1931). Untitled landscape. Signed “GFE,” dated May 9, 1869. Pencil on paper. One of 37 drawings in a sketchbook.

28

sketchbook. NBWM 1974.18.35, Gift of Anne R. Dechert.

Spreading the Word

Digital Engagement through Primary Source Transcription

By Michael Lapides, Director of Digital Engagement, New Bedford Whaling Museum Joe Quigley, Museum Volunteer, Transcription Team, New Bedford Whaling Museum

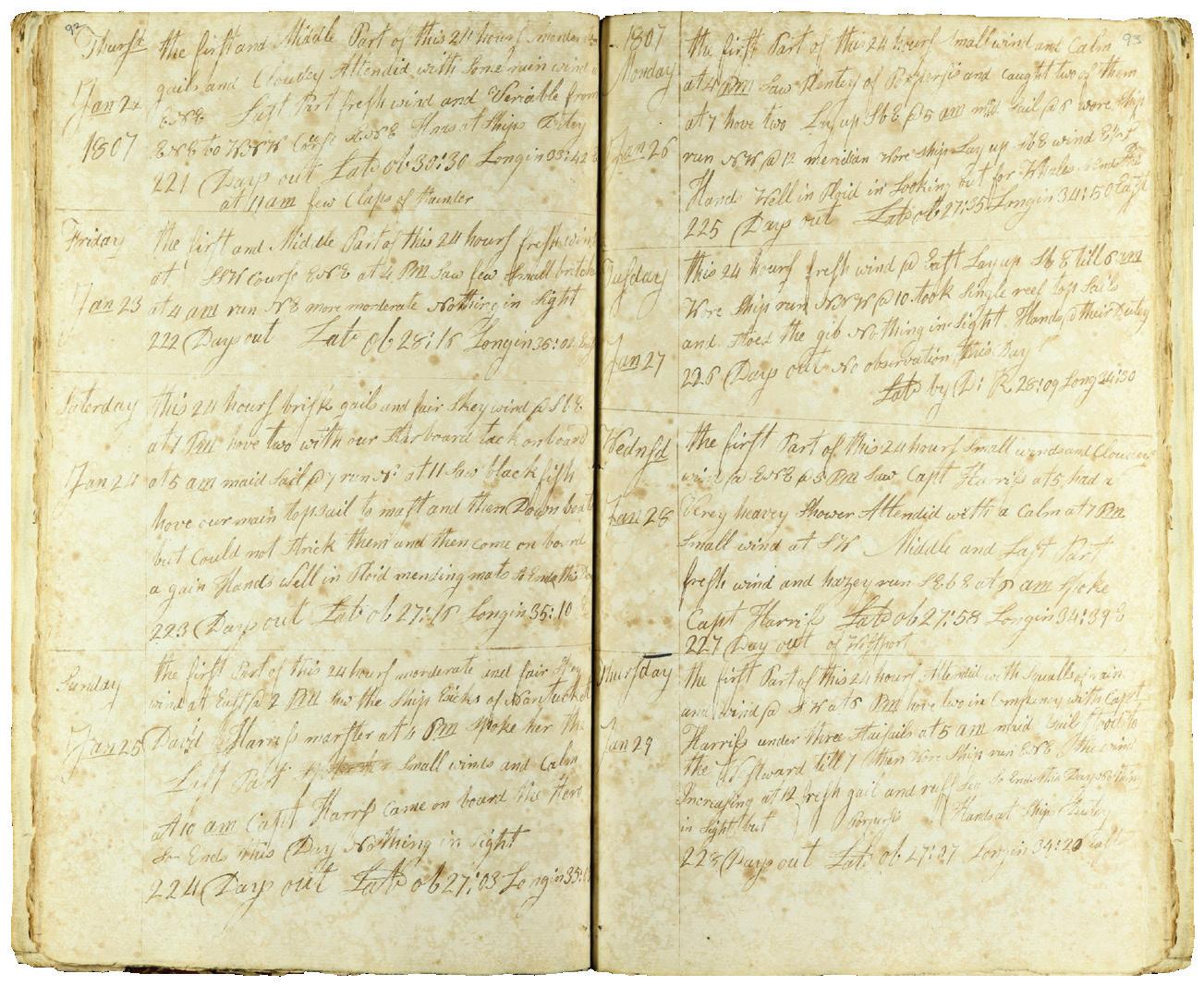

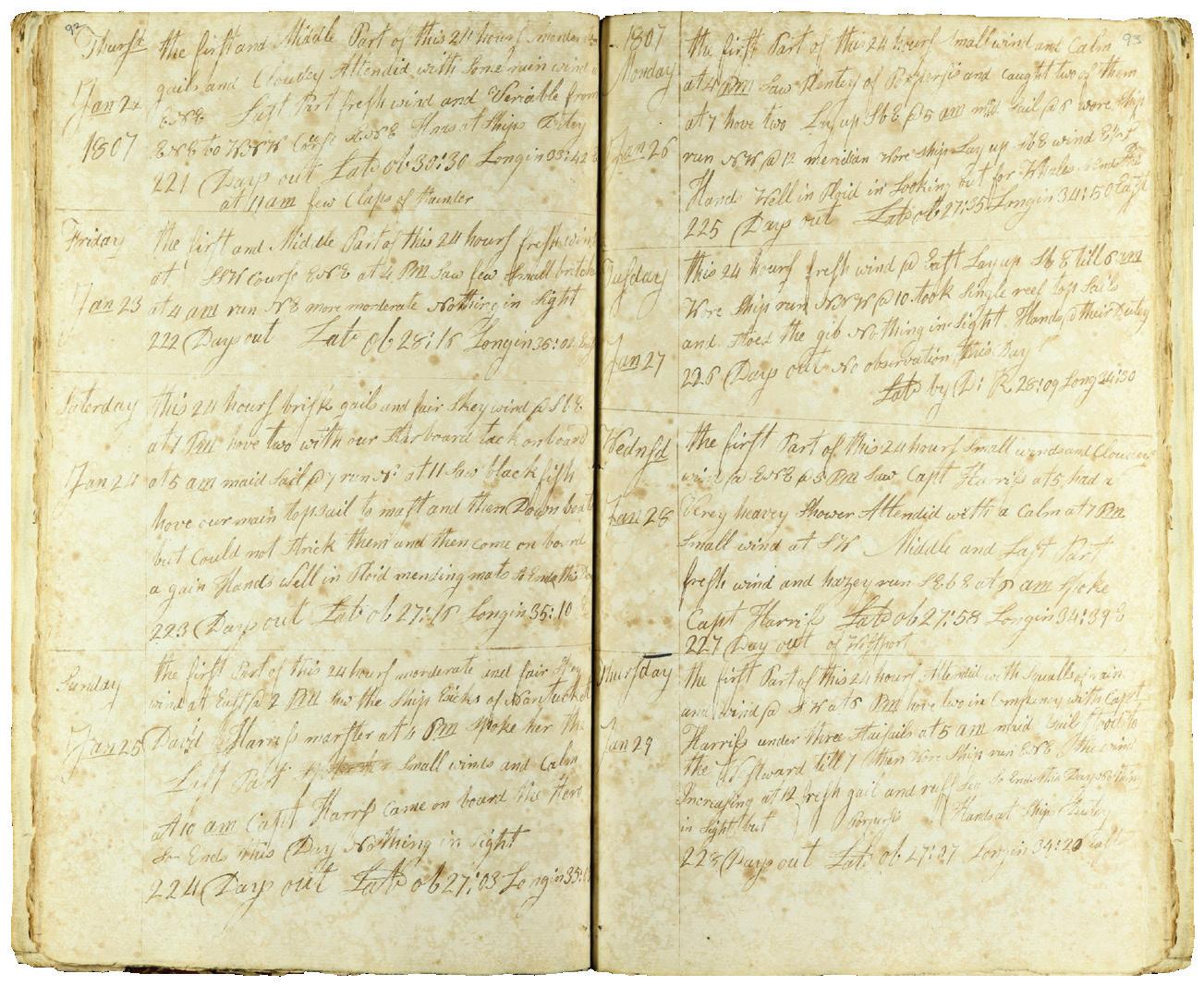

Logbook pages from the bark Hero of Westport, Samuel Tobey, master, sperm whaling just south of the Mozambique Channel on the East Coast of Africa, January 22 – January 29, 1807. On Sunday the 25th, the bark Hero spoke the ship Essex of Nantucket, David Harris, master. Harris and the Essex were right whaling and Harris came onboard the Hero. This was the same ship Essex (238 tons), George Pollard, master, that would be rammed and sunk by a sperm whale on the Off Shore Grounds of the Pacific Ocean fourteen years later. NBW 1438b

The bulk of the Museum’s logbook and journal collection, almost 2,500 volumes, documents both American and international whaling from 1754-1968. It is the largest and finest collection of whaling logbooks and journals in the world. Recently the Museum purchased a significant volume to add to this collection; logbooks of two separate voyages bound together as one volume. The first voyage is the schooner Ranger of Westport, MA, [Jeremiah?] Wainer, master, Raimon Castino, keeper, December 26, 1804-April 3, 1805. This was a trading voyage from Westport, MA to Guadeloupe in the Caribbean. The second is the bark Hero of Westport, MA, Samuel Tobey, master, Paul Wainer, keeper, June 16, 1806-November 20,

1807. It was a right whaling voyage to Delagoa Bay and the Indian Ocean under the ownership of Isaac Cory, Sr., Isaac Cory, Jr., Paul Cuffe, and Thomas Wainer, of Westport, and is an important volume on several levels. The Cuffe/Wainer business and family relationships demonstrate the intersection of African American and Native American regional lineage and their successful maritime commerce. This voyage is also early documentation for a bark rig in the whale fishery, and a very early Westport whaling voyage to the Mozambique Channel.

How does the Museum absorb a logbook like this into its collection, and from the standpoint of Digital

29 | Fall/Winter 2022

Engagement, how do we make such resources available to researchers and the general public? First, the curators and librarian inspect it for authenticity and potential research value. Once they decide to purchase or otherwise accept the volume, it may be assigned as a priority for digitization. From there the volume is added to our running list for digitization and may be further prioritized for transcription. The Ranger/ Hero logbook is in exactly this prioritized category, as the Hero voyage, in particular, documents significant events in the maritime history of the region.

Beginning in 2016, with a backlog of logbooks and whaling crew lists waiting to be transcribed, a core of volunteers was recruited to help with this work and shortly we had a small group working collaboratively. We built a process so they could work from any location, not just our Reading Room; a rigorously managed process based on library and archive best practices. Now, over six years later, we are an active group including fourteen volunteers. To date the team has transcribed hundreds of New Bedford Port District crew lists, and dozens of logbooks, journals, and whaling agent letterbooks. This past summer we moved from Google Workspace to a crowd-source based transcription platform called From the Page. This allows us to continue to transcribe documents from any location, make our transcription projects public, recruit transcribers from the platform’s community of over 3,000 users, and lastly manage our transcription projects more effectively.

Importantly, each transcription we complete and make public in From the Page can be linked to, and eventually embedded within our data-rich website WhalingHistory.org. Moving toward a new and improved collections management system in 2023, with an improved public-facing catalog, each digitized and transcribed logbook will be viewable there. These volumes are, and will continue to be, publicly available on the Internet Archive as well, displayed in their original form, with a side by side word searchable transcription.

Transcriber Joe Quigley describes the work:

We know the names of the members of crews because submitting crew lists to the custom house

had been required at the Federal level since the Act of 28 February 1803. These names, currently numbering 177,261 representing New Bedford, Fall River, and Salem, Massachusetts, and also New London, Connecticut are now all accessible through WhalingHistory.org. From these lists we can learn a bit about each whaleman including their name, place of origin, residence, and personal information such as skin color, hair color and in the case of Black sailors, its texture (wooly).

Of the hundreds of crew lists we transcribed I worked on three where every crew member was identified as Black. I was curious if the master was also Black so I followed to see where this would lead. The master of the Rising States in 1836 was Edward J. Pompey, a leader in the Massachusetts Black Community who worked with William Lloyd Garrison, the prominent American abolitionist. This was not a Black crew under the command of a White man. The entire crew and officers were Black. The first mate for the 1806 voyage of the Hero was William Cuffe, son of Paul Cuffe, who in 1837 moved up to be master of the Rising States. He maintained the all-Black Crew.

The voyage of the Hero, owned by William’s father, Paul, set sail in 1805 before there was a crew list registration requirement. There is no known crew list for this voyage. A crew list may still exist somewhere, or names of the crew may be listed in whole or in part throughout within the log entries. The possibility exists that some young green hand became an important figure later on. It would be interesting to find any connections, and the transcriptions we are working on improve accessibility and enable discoveries of all types.

As a volunteer transcriber following such leads is encouraged and could turn up something that would have otherwise been left in shadows. Each document is a potential lead.

We encourage transcription volunteers to help the Museum improve access to its collections and to share the stories they tell.

30

Lighting the Way

Bringing to Light the Story of Alberta Knox

By Cathy Saunders Coordinator of Lighting the Way: Historic Women of the SouthCoast New Bedford Whaling Museum

By Cathy Saunders Coordinator of Lighting the Way: Historic Women of the SouthCoast New Bedford Whaling Museum

One of the great joys of my role as coordinator of the Whaling Museum’s project Lighting the Way: Historic Women of the SouthCoast is collaborating with colleagues to bring to light the experiences and contributions of local women. Alberta Mae Knox Eatmon (1896-1991) is one such figure.

Alberta Knox was a member of an esteemed New Bedford African American family with roots in the antebellum era. Harriet Jacobs (1813-1897) was her forebear, an ardent abolitionist and author, who wrote a famous autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself (Boston, 1861) Alberta’s brothers were very accomplished; one was an Ambassador to Haiti, another a chemist who worked on the atomic bomb, but her own story, until recently, has been overshadowed.

Knox came to the attention of Lighting the Way through our collaboration with the New Bedford Historical Society. Ivy S. MacMahon, who volunteers for both the Historical Society and Lighting the Way, stepped forward to delve into this story. She began researching Knox during the pandemic, starting with online searches through sites like Ancestry. com and the Amistad Research Center. Locally, she explored Spinner Publications, the New Bedford NAACP’s website, and the Whaling Museum’s online

Portrait of Alberta Knox, Bridgewater State Normal School class photo, circa 1920. NBWM, Mss 203, Knox Family Papers, scrapbook.

collections search. She also corresponded with a descendent. Ivy noted:

Researching the history of women of color is becoming easier with the recent public focus on the history of their struggle for equality and with the increased online availability of research data, e.g., church records, maps, and archives.

“Some teachers are born not made,” begins her portrait of Knox on Lighting the Way, and through the profile we learn that Alberta was salutatorian of the New Bedford High School class of 1913, that she studied at Bridgewater Teacher’s College, and subsequently had a teaching career lasting nearly 50 years. She met Boyd B. Eatmon (1898-1997) while teaching at the Manual Training School of Burlington County, New Jersey, and they married in 1936. They lived in Burlington County, raised a family, and Alberta was always civically engaged. She served as president of the New Bedford Branch of the NAACP in the 1920s, corresponding with such notable civil rights leaders as W.E.B. DuBois (1868-1963), and was active in many community organizations in New Jersey where she eventually lived. Ivy concluded that Alberta Knox was “honored and dearly loved.”

This account of bringing Alberta Knox’s story to light could end there. However, not long after we published her profile on www.HistoricWomenSouthCoast.org, Mike Dyer, Curator of Maritime History, contacted me about an “astonishing” scrapbook, “a thing of