DEN SITY STU DIO MON SOON ASIA

Victoria Jane MarshallOp�on

Foreword

The Density Studio was taught in the Master of Landscape Architecture program at the National University of Singapore in semester one (August-November) of 2023. According to the Master of Landscape Architecture handbook, the studio delivers ambitious pedagogical goals. Students choose to work on a range of important landscapes issues in Southeast Asia, especially related to the fast-growing urban agglomerations of the region. In addition the studio teaches students to integrate ecological, social, and economic thinking in the course of generation of designs that form optimistic futures for the region. The Density Studio approached this task through a one-kilometer square, periurban case study site in Monsoon Asia. As seen in the ten individual projects in this report, the Density Studio students demonstrate tangible and creative ideas for hybrid, urban-rural futures.

Students

Guo Zhiyi

Liu Runhan

Long Siyu

Ouyang Luoman

Tang Yanqi

Virginia

Yang Yikai

Zhang Yu

Zou Lipeng

Zou Xiaoqian

Guest Critics

Victoria Jane Marshall (Studio Tutor)

Denise Lee

Dorothy Tang

Evi Syariffudin

Federico Ruberto

Gu Tiantong

Haozhuo Yang

Maxime Decaudin

Tang Wei (Report Design)

Reflection

Projects

Ayur Commons: Botanical Uprising Against Remittance Trap by Guo Zhiyi

A Cultivated Park: For an Open Community by Long Siyu

Co-designing Generative Agriculture by Tang Yanqi

Breathing Anew: Penang as a Template Balancing Air Pollution and Social Injustice by Yang Yikai

Designing a “Survival Model” for Periurban Phnom Penh by Zou Xiaoqian

The Squeezed Land: Determining the New Face of Periurban Areas in Tangerang Regency by Virginia

Hybrid Towns: Exploring Periurban Future by Zhang Yu

Energy Towns: Periurban Energy Activation Landscape by Liu Runhan

Forgotten Corners in the Greater Bay Area by Zou Lipeng

From Remnants to Resonance: Reimagine the Future of Coastal Fishing Villages by Ouyang Luoman

Reflection

Victoria Jane MarshallWhile density is a powerful concept that is regularly used by the state to shape urban form differentially over time, it can be thought of more broadly. If density is presumed to be an open concept, it can hold more than one definition. Thus, it affords the projection of multiple rationales of meaning. For instance, geographer Colin McFarlane (2016) notes that density is both a topographical problem of number and measurement, and a problem of topological politics and space. In response, the Density Studio asked what density-based reasonings might best be used to promote or hinder desirable settlement, and on behalf of whom or what?

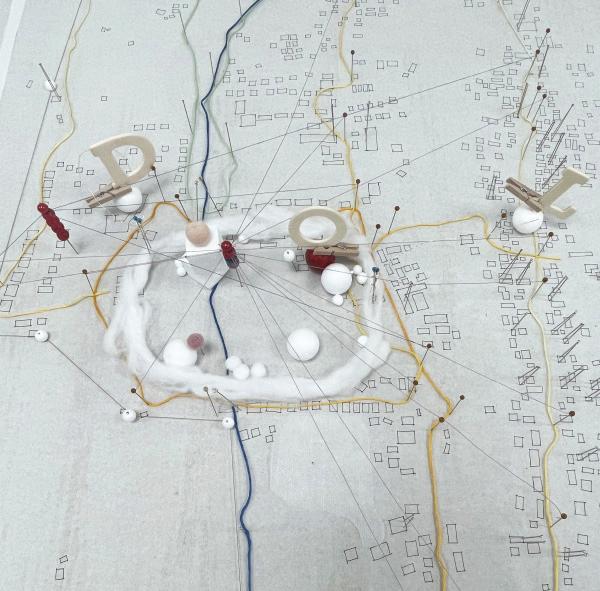

Each student self-selected a one-kilometre square study area as their prompt for inquiry. One parameter for study area selection was guided by the term “ordinary” (Robinson, 2005). The term ordinary here means a settled area where there is no singular big conflict, where power, understood topologically and with nonhumans and their diverse agencies in mind, is diffuse. To demonstrate this concept, the study area selection rationale created by studio critic Victoria Marshall in the book Periurban Cartographies (2024) was used as a guide.

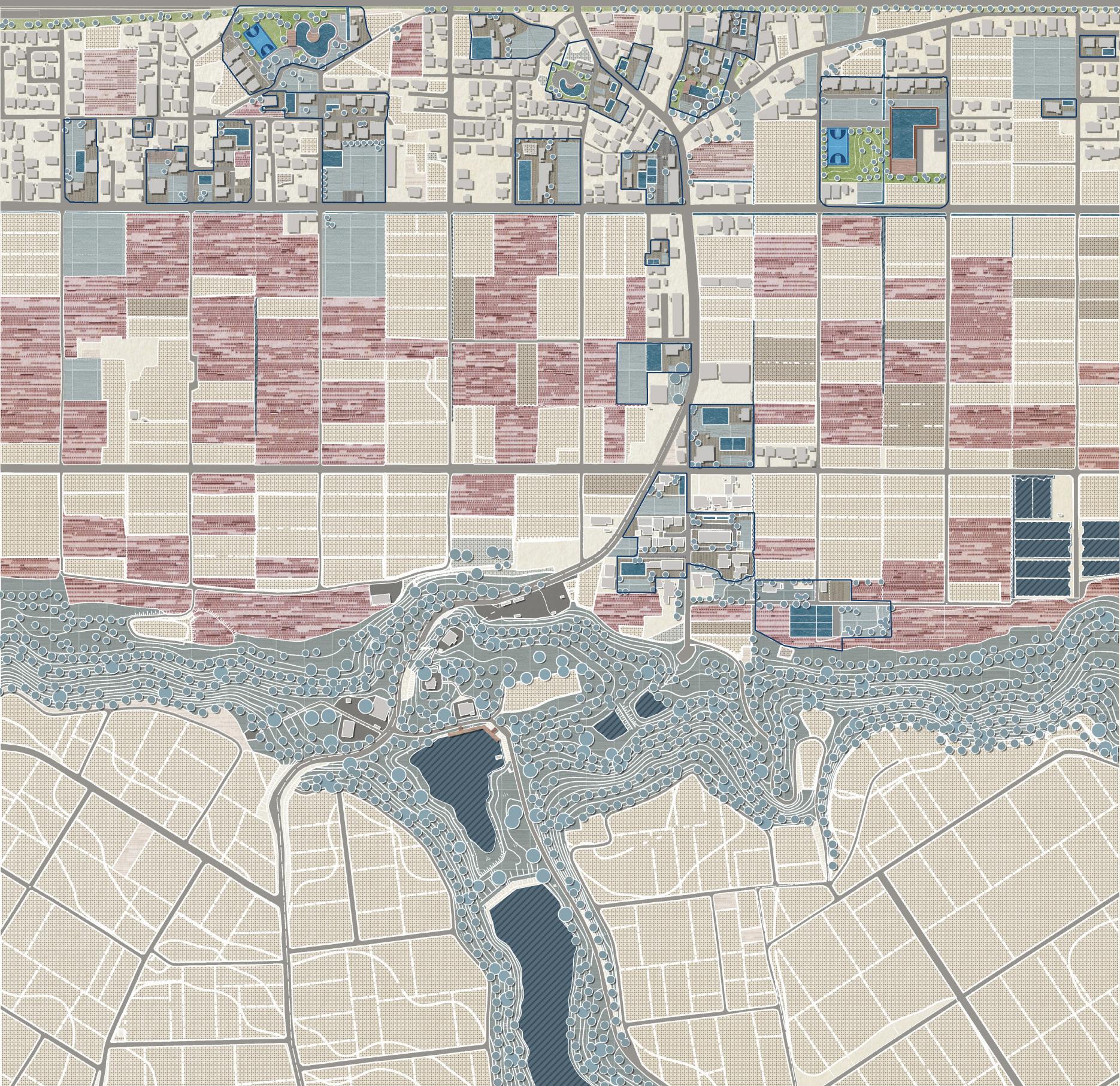

A second parameter for site selection was provided in a map created by the Agropolitan Territories of Monson Asia module (FCL, 2023) at the ETH Singapore, Future Cities Lab. The students selected their ordinary, study areas within the bounded areas shown on the map. The map (page 6-7) highlights areas where selected data intersect and where an “agropolitan outlook” to urbanisation is being researched at the time of writing. An agropolitan outlook foregrounds the inter-dependence of future cities and future agriculture. Over the mid-semester break, the students visited their selected study area in Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia, Indonesia, China, and Japan.

To focus on a re-territorialised Monsoon Asia is creatively productive for both students and periurban residents. This is because the task of imagining a transformation of an urban-rural settlement is to value the settled rural in a projective way. Rather than thinking of periurban teleologically - as the “edge of the city” and as not much more than “becoming urban,” the studio focus was toward “being periurban” anew. This was accomplished through a mix of linear (from rural to urban and urban to rural) and non-linear (from one type of urban edge to another type of urban edge) rationales, as well as an interest non-human agency.

Any task of study area selection is propositional, for it comes with assumptions about what might be possible or impossible in a certain place. Starting with a quick future scenario assignment in the first two weeks of semester, project outcomes slowly emerged from further ideation throughout the semester. Using the tools of drawing and model making the students grasped their found, density puzzle by exploring how density is lived, experienced, and contested, and how alternative forms of compactness might emerge. This iterative design research practice was supported by fieldwork, individual weekly critiques with the studio critic, periodic sharing sessions within the studio, and formal reviews with invited guests. As architect Stefani Ledewitz (1985) points out, the purpose of starting with a proposition, or “beginning backwards” is for students to immediately share the knowledge they have and thus, to see what additional knowledge might be needed.

The final projects illustrated in this report are locality-led proposals for future urban-rural forms implemented incrementally. Meaning, existing and imagined landscape practices are anticipated, and collectively, they are designed to transform land use, land cover, space, and power. All of the projects are multiscalar and most of the projects include the following: a relation to (and interpretation of) everyday life and lived ecologies at a defined scale; an appreciation of non-human agency, however defined or encountered; innovative spatial strategies at the locality level linked with tactics for the equitable rearrangement of power; tangible ideas about the elements and qualities of physical public space; and lastly, the bracketing of a certain time frame for attention and investment in the proposed transformation. The studio outcomes reveal that an emplaced, landscape architecture approach to density can act to untether outdated or irrelevant density narratives while addressing issues of inequality and environment.

Map showing agropolitan territories of Monsoon Asia (white bounded areas) and the location of Density Studio projects (yellow icons). From West to East:

India: Guo Zhiyi

Thailand: Long Siyu

Thailand: Tang Yanqi

Malaysia: Yang Yikai

Cambodia: Zou Xiaoqian

Indonesia: Virginia

Indonesia: Zhang Yu

China: Liu Runhan

China: Zou Lipeng

Japan: Ouyang Luoman

AYUR COMMONS

Botanical Uprising Against Remittance Trap

byGuoZhiyiBackground: Ayur Commons addresses three interconnected factors in peri-urban Thrissur, Kerala, India. Since the 1970s, a substantial migration outflow has led to 46% of income coming from remittances. Originally invested in individual real estate, these remittances have contributed to the decline of local coconut and fish farming. With global uncertainties and natural disasters looming, compounded by unemployment and unfair investments, the remittance trap is predicted to worsen in the area. Secondly, poorly-maintained industrial land and developing personal residential plots, has become a hotspot for waterborne disease viruses following monsoon flooding disasters. Efforts to address diseases, like clean water sources and medical facilities ironically bypass coastal communities affected by floods. The project aims to reorganize development patterns, core industries, and their relation to topography, providing solutions for the remittance trap and monsoon-related malaria outbreaks.

Opportunity: The site offers three opportunities for a herb cultivation-centered landscape project. Firstly, the sacred grove preserves herbal resources, offering low-cost, low-risk medical solutions against post-flood malaria. Secondly, custom Development Agreements enable resource sharing. Thirdly, the Government’s plan for large-scale medicinal plant cultivation is a lever to break the remittance trap, emphasizing terrain maintenance.

Strategy: The project’s initial step is recognizing site and community vulnerability to waterborne diseases and sea-level rise. Private landowners who own uncultivated land on higher ground can choose to enter into a community-based agreement to build “highland shelters”, incorporating space for gathering, rainwater harvesting and gardens for herbal plant cultivation. The second step is more structural than the first, which is emergency-based. In this step three new land development practices that promote resource sharing are imagined here as “rituals”. - kaavumattam (relocate), punaprathishtta (reduce), and ozhippikkal (destroy) - All “rituals” are envisioned to occur simultaneously and incrementally, toward an eventual transformation of the peri-urban shore line resulting in a high-density community for traditional medical practices, a self-sustaining cultivation industry, and a disaster-resilient community.

Kaavumattam introduces three innovative shared housing forms for residents and transfers herbal resources to private gardens for production, education, and medical use. Punaprathishtta, based on residents choosing traditional housing forms, provides a small communal space or herbal resources for public use, connecting with shelters to establish an integrated healthcare system. Ozhippikkal ritual adapts degraded plantations and fishponds affected by sea-level rise, allowing producers 21 days for adaptive herbal intercropping experiments. New cultivation methods alter coconut plantation terrain for rapid drainage during monsoon seasons and revitalize fishponds with aquaponics, serving as a buffer to protect coastal communities.

A CULTIVATED PARK

For an Open Community

byLongSiyuThe construction of the second ring road around Chiang Mai, Thailand has significantly reduced commuting times between the city center and periurban areas. This has attracted a substantial number of middle-class residents to purchase land and property in periurban regions, leading to a socio-spatial-ecological puzzle. That is, the emergence of closed residential estates predominantly inhabited by the middle class , open mixed-use localities characterized by a mix of various social classes, and ongoing rice, fish, fruit, and vegetable cultivation in the peri -urban areas. This mix of open and close communities is occurring in tandem with shifts in land use patterns and resource allocation, causing increased local travel distances and fragmentation amongst open localities, and canal sediment, impacting cultivation practices.

The transformative concept centers on the creation of a park that fostering more highly connected mixed-use localities through the active engagement of all residents, including those who cultivate, those who own local businesses like homestay or food production, those who raise families and create a home, and those who commute.

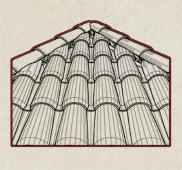

Central to the park design is the practice of rice straw recycling. Home-based rice straw industries linked to common reuse sites have a role to play here, for they utilize rice straw generated from rice cultivation to create rice straw wattles, which are employed in the vicinity of canal embankments to facilitate sediment settlement, filter and slow down the flow of water into canals. Such rice straw elements act to support circulation, for they are also deployed to stabilize muddy ground and create simple pathways that lead residents to and from the park. Establishing rice straw recycling industry, reuse sites, and pathways is linked to existing voluntary commoning with the annual Loi Krathong, which is an organized voluntary community engagement practice in maintaining the canal system for all.

The central park boasts features catering to both locals and attracting visitors. It transforms an otherwise inaccessible space by advocating for the recycling of rice straw as roofing material. Rice cultivation, a major economic crop in Chiang Mai, is prevalent in peri-urban areas. To address direct burning by farmers causing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, we actively promote the recycling of straw. These materials construct unique architectural spaces, providing a distinctive public area for local residents, including food vendors and artisan workshops.

Integrating the canal and on-site banana cultivation creates abundant resources for locals and visitors. These resources are used for celebratory events like the Water Lantern Festival, supplying raw materials and an ideal venue. This comprehensive strategy reduces environmental pollution and fosters sustainable development and shared spaces, enhancing local culture and economy.

Overall, the project supports open communities and agricultural practices amidst the pressures created by the fragmentation of space and the continuous realignment of distance By grounding a park anchored with existing volunteer practices the project is an infrastructure for an even more mixed, mixed-use locality, one that attracts people to stay in place, thus reducing commuting pressures and pollution, and improving local environment and attachment to the rhythms of water and cultivation.

CODESIGNING GENERATIVE AGRICULTURE

Cultivation Type Change in Periurban Bangkok

byTangYanqiMy project creatively adapts changes occurring in and amidst peri-urban orchard plantations on the West Bank of the Chao Phraya River near Bangkok. The project takes a critical stance, pushing back on the existing inequitable land management practices that have led to high orchard production vulnerability to land use conversion. Bang rak noi, is my case study area in Nonthaburi province and it is influenced by the planned Central western Economic Corridor that connects both to Bangkok and the eastern regions, as well as to the Dawei port in Myanmar and brings an city planning, which brings an emphasis on developing high-value hi-tech industry and agro-tourism industry.

Accordingly, my study area has seen significant planned and unplanned settlement practices over the past 20 years. My project reassembles the relations between such peri-urban transformations so that they might be more equitable and ecologically sound. I have entitled this practice generative for my design strategies aim to pull forward existing positive practices and spaces and generate a future from them.

There is a key tension that my project addresses. First, factories that come with the eco-nomic corridor and middle-class housing estate that come with increased highway connectivity to Bangkok are replacing a large area of productive orchard plantations. The orchard plantations are themselves the result of the market. This change is characterized by a shift from hybrid to monoculture, resulting in a strong link to higher dependence on food processing factories. Second, land conversion has brought about environmental pollution such as water contamination and canal degradation further troubling the cultivation of agricultural products.

In response to the tension, this project is for the purpose of distributing reassembles power and encourages farmers to explore a more profitable business model through generative agriculture. There are three stages of spatial tactics. First is the creation of a cluster. The cluster is shaped by five stakeholders and they come together through a common concern, how can agricultural land persist? Second is the action of creating social support network such as connective practices of planting events and training sessions. Such practice happens along important linear spaces like road, canal and bridges. Third, economic corridor industries shift further along the economic corridor and retool to be more eco-friendly as they go, thus opening up space for new commercial enterprises like sales center and agri-food transportation. In parallel, the government will build stakeholdercluster defined basic infrastructure.

In sum, the project reassembles the tension between the economic corridor and the urban periphery. It argues for a community-based land management that both informs and is supported by economic corridor investment.

BREATHING ANEW

Penang as a Template Balancing Air Pollution and Social Injustice

byYangYikaiAir pollution is not just a technical or ecological issue but deeply reflects the challenges of social agency, resource allocation, and community participation. Impoverished and marginalized groups reside in areas with more severe air pollution, while those with ample resources and power bask in cleaner environments. The project’s core concept aims to co-create a more harmonious peri-urban air model in Penang, where every individual collaboratively participates, collectively contributing to a cleaner future. This is not just a material change but a cultural and ethical awakening, urging residents to reimagine relationships with environment, for it is changing. The vision of the project is through collective effort, to foresee and implement a just landscape imaginary, allowing everyone to thrive in a better environment.

The project includes three spatial and material strategies that are imagined occurring sequentially. First is a “Windbreak Forest Plan”. This is a plan created by Penang City Council and adopted by the local municipal government. The plan empowers community residents and factory workers to care for specific trees in their respective areas. These trees act as barriers, capturing and absorbing particulate pollutants from the air, improving the overall environmental quality.

The second strategy addresses an issue of fragmented space, something that occurs frequently in peri-urban areas where all sorts of land use change plot by plot, and appear side by side forming strange neighbors that have yet to find ways to get along with each other or to get around each other. Additionally, in the area, the prevalent use of motorcycles as a primary mode of transportation significantly contributes to air pollution. To address this issue, I imagine a bridge design optimization project funded and overseen by the State Public Works Department or the State Department of Transportation, making it a key linkage to connect various fragmented areas. Not only does it absorb pollutants from the air, but it also serves as a public space for rest and interaction. This strategy is oriented towards improving air quality, fostering peri-urban spatial connectivity, and promoting lowcarbon commuting.

The third strategy focuses on reducing key sources of air pollution, by involving participants or volunteers in collecting straw from farmlands for recycling., which will then be transported to designated spots to be processed into disposable containers, catering to the high demand in Malaysian cities with outdoor-centric lifestyles, like street vendors and food stands. Concurrently, an existing old rice mill will be refurbished to serve as an air monitoring and community center, overseeing the straw recycling and processing, thus establishing a sustainable cycle of usage and environmental stewardship.”

The ‘Clean Air Marathon,’ organized by a network of local running groups with corporate sponsorship, is planned as a recurring event in different locations, symbolizing the success in purifying local air. On event days, roads will be closed to vehicles, transforming it into more than just a sporting event, but a significant environmental advocacy initiative. The project, ‘Breathing Anew’, led potentially by the Society of Landscape Architects Malaysia, redefines, and connects peri-urban spaces. It improves air quality and unites diverse communities into a cohesive peri-urban vision. This initiative goes beyond ecological enhancement to inspire public imagination, encourage collective involvement, and promote resource equity. With ongoing collab-orative efforts and creative methods, it steers Penang towards a sustainable, healthy, and equitable future.

DESIGNING A SURVIVAL MODEL

For Periurban Phnom Penh

by Zou XiaoqianConcept: This project analyzes the waterlogging dynamics in Phnom Penh, focusing on reclaimed lands at the city’s peri-urban area. It examines land reclamation practices for an emerging middleclass, the resultant patterns, which create spatial fragmentation of existing agricultural and periurban settled areas. The project reimagines land reclamation to mitigate waterlogging and provide stability for longtime residents that live in such an unsettled landscape.

Phnom Penh is situated on the banks of the Tonie Sap, Mekong, and Bassac Rivers. These rivers provide freshwater and other natural resources to the city within the city and beyond it are many broad, shallow lakes that act to regulate waterlogging and flooding but are increasingly created as the site for middle-class villas, large housing estates on land created by dredging the river, and the lake. Limited vegetation, agricultural soil erosion, and a lengthy rainy season exacerbate the risks of waterlogging for low-lying existing villages and periurban housing and commercial settlements My study area is located on one such lake, the Boeung Tamok is located north of the city and its size has reduced by 50% on the last 10 years. My project does not reflect such filling, for it is massive and enabled by the powerful state, but rather I reimagine it as a more just and less ecologically destructive practice.

Strategies: Overall, this project shapes a survival model for periurban Phnom Penh using two spatial strategies that run in parallel.The state and locals will collaborate to build a compact water treatment system and a water transportation system around the peri urban Phnom Penh using the “dig-fill” model modification method and the sponge greenland method.

First, the project’s success depends significantly on collaboration between the government and local residents. In the initial testing phase, it’s crucial for the government to allocate funds to excavate a versatile reservoir, meeting the daily needs of suburban Phnom Penh residents. Simultaneously, constructing elevated areas aims to empower locals for independent cultivation and movement. Active community engagement is paramount, establishing a feedback loop for potential strategic adjustments. This prompts the consideration of additional investments and the expansion of construction areas for an effective cut-and-fill model implementation.

Second, when the government attracts some locals from the “bottom” to the “highlands” through negotiation and construction, they can use the water transportation system to get out of the crisis faster in extreme weather. At the same time, local people who choose ordinary living areas will be protected from the threat of waterlogging because of the sponge plots and new canals designed by the government.

Implications: In sum, the collaborative efforts between the government and local residents have given rise to a new “survival model” for peri-urban Phnom Penh. This model ensures that residents have access to water reserves during the dry season and effective waterlogging treatment and transportation services during the rainy season. Significantly, this adaptable “survival model” can be extended to encompass various fragmented peri-urban areas, linking them together to forge a novel approach to peri-urban survival under the lake reclamation policy in Phnom Penh.

THE SQUEEZED LAND

Determining the New Face of Periurban Areas in Tangerang Regency

byVirginiaThis project aims to transform land tenure dynamics in coastal communities through innovative landscape design, fostering economic opportunities and equitable land ownership practices. In Tangerang Regency, Indonesia, master-planned coastal development for commercial and residential purposes has brought about adverse consequences for long-settled fishing villages. The demand for coastal land has increased, causing conflicts between traditional land claims of local communities and land acquisition by external enti-ties, such as property developers. Changes in land cover have raised two significant con-cerns. First, local populations have struggled to adapt their livelihood to shifts in the eco-nomic landscape, resulting in heightened poverty levels. Second, alterations to terrestrial and marine ecosystems have led to issues like erosion, shifting the coastline by up to 1 kilometer inland, resulting in the loss of productive fishponds.

To tackle these challenges, this proposal presents two key strategies that seek to strike a balance between economic development and coastal ecosystem preservation. Simultaneously, it aims to promote more equitable land tenure practices, addressing the root causes of conflict and environmental degradation in the coastal region.

First, the project builds upon an existing network of home-based female entrepreneurs that make and market products like milkfish floss, jelly, sweets, and crafts. The project sup-ports and brings a public face to such activities in the form of a mini-mall on an underused plot of land in the center of the fishing village. With women juggling domestic responsibili-ties and the need to support their families due to aquatic ecosystem degradation impact-ing men’s livelihoods, this concept is designed around profit-sharing. Women become co-owners in collaboration with property developers, leveling the gender playing field and fostering stronger local-resident-developer relationships. This model seeks to break down power imbalances, equalize gender roles, and create a fairer, more sustainable economic environment.

Second, leveraging the mini-mall’s success can catalyze investments in developing a new mangrove area to combat coastal erosion. Mangroves can create economic opportunities, fostering marine habitats for activities like cultivating mangrove crabs. These resources are expected to improve local fishermen’s livelihoods by enabling them to invest in larger boats for deeper water fishing. Over the next decade, the mini-mall concept can be repli-cated in other regions, establishing a novel economic paradigm.

The landscape concept supports the proposed strategies by focusing on key principles. It emphasizes selecting low-maintenance, locally endemic plants for increased productivity. The strategic use of bamboo and cultivation of red seaweed serve both aesthetic and eco-nomic purposes in daily aquaculture activities. Adopting a low-maintenance approach for hardscape minimizes upkeep, while using green mussel shell waste as paving material provides a sustainable solution to village shell waste. Overall, the integrated concepts aim for an aesthetically pleasing, functionally efficient, and sustainable landscape supporting community activities and preserving the local ecosystem.

THE PRODUCTION HOUSE

THE NEW WOMEN HUB

EMPOWER NG EQUAL TY, GN T NG VO CES: A WOMEN'S HUB FOR EQU TY EMERGENCE

THE LAND SQUEEZED

To

THE NEW WOMEN HUB

EMPOWER NG EQUAL TY, GN T NG VO CES: A WOMEN'S HUB FOR EQU TY EMERGENCE

ID NUMBER :

THE PRODUCTION HOUSE

STUDENT NAME/ ID NUMBER : VIRGINIA/A0231294J STUDIO TUTOR : VICTORIA JANE

HYBRID TOWNS

Exploring Periurban Future

byZhangYuThe study focuses on the changes and movements of “density” in the periurban area of the Global South. The project is in Bali province, Indonesia in monsoon Asia. By interpreting the composition of the periurban landscape to understand the life of local people, the economic development model, and the challenges and opportunities faced by the site, my project asks how the town can become a lens for seeing the periurban future.

Through the comparison and analysis of nearly two decades of land use in Ubud, Gianyar Regency, rapid land conversion occurred here, which caused some people and things to leave to make room for new arrivals. Along with the land conversion comes a change in the landscape pattern: the forest land is reduced, the farmland becomes fragmented and patchy, and the linear Balinese village feature is also broken by the influx of foreign capital. To protect natural resources and guide a sustainable periurban territory, I proposed two strategies based on the site context.

First, a community organization is introduced to conduct unified management of land development, transfer, and restoration, serve as a third party to negotiate the development needs of the government, residents, and external capital, and promote a new cooperation model based on consensus on resource protection before development. At the same time, the organization would be encouraged to strengthen the management of land replacement, improve the records of land use changes and transfers, set land density proportion limits, and land compensation systems. The responsible person will provide compensatory measures for changes in protected lands such as forests and rivers to maintain the density balance here.

Second, a large collective of landscape features, “Stone Gardens”, will be encouraged to be established in the intersection between local settlements and capital resorts, which will bring together all the representative site features, and everything that visitors want to explore, such as rice terraces, jungle adventures, art experiences and more. This strategy aims to guide more resources to serve the public through the transformation from uncommon land to common land. That is, serves a wider audience with less investment, and promotes the protection of natural element density and ecological injustice.

The project speaks to situational design thinking, how to match the strategy with the site, and find a combination of strategies with practical significance based on the state power, local economic development model, and people’s living habits, and explore a new hybrid town model in the periurban context.

ENERGY TOWNS

Periurban Energy Activation Landscape

byLiuRunhanChina has a huge energy inequity problem, because energy generation is monopolized by large corporations, and new energy development and testing bases are unevenly distributed, favoring just a few high-tech development areas in China.In response, this project reimagines the renewable energy ecology of peri urban China by proposing a distributed and public interest-oriented approach. I have chosen periurban Hainan Province as my case study area, for the inequity puzzle is evident here.

Based on my research, a distributed and public-interest-oriented approach empowers local people over large corporations and it decenters investment in renewable energy technology development and testing. Hainan Island has sufficient light and wind power resources. In selecting my study area in Longhua district, Hainan Island, I kept these factors in mind. In my study area the local residents are aging, many of the old people can just stay in their own yard and there is no safe pedestrian way and public spaces for relaxing and socializing, and parts of the farmland are facing a portion of desertion. In addition, there is a lack of young laborers and new ways of earning income to activate the current isolated situation. I thus felt that my distributed and public-interest- oriented approach would be a good fit here.

My design proposal has two steps. First, the Chinese government, which already emphasizes the importance of developing Hainan’s environmental resource value, is imagined to provide economic incentives to local residents living in my study area. Such invent is targeted toward the renewable energy elements such as solar panels, wind power turbines. Local residents might choose to integrate and apply them in different ways and forms on different sites, such as rooftops, farmland, and open space besides highway, to create landscapes that support the elderly, young entrepreneurs who want to start a small business.

The electricity produced can meet the daily electricity needs of the residents, and then the excess electricity is sold, which could provide a way of earning money for renovating to improve the living environment of the residents. At the same time, the landscape elements can be combined and recombined as needed. For instance, A photovoltaic farm (a hybrid model of agriculture and solar panels) can attract nearby residents of Haikou city to experience or lease farmland from farmers for experience, promoting the ongoing cultivation of vegetables or other experimental crops. Local villagers can offer classes to teach urban people farming techniques, in which way the two groups of people can engage in activities in public space.

The money earned from energy facilities can be invested together by the community for improving local people’s life quality, such as creating a safe pedestrian road that connects different courtyards along the main axis and creating new public activity spaces for residents, such as small vegetable plots for the elderly to cultivate. Also, improve riverside wetland landscape, to guide a more freeflowing circulation.

In my distributed and public-interest-oriented approach local people generate their own energy and reduce dependence on large energy companies which have rents and transportation costs for selling, the energy generation improves and solves the inequitable distribution of energy. And brings a technologically complex, eco-friendly, and enjoyable mode of living for both local villagers and urban population, and brings the possibility for the younger generation of villagers who come to work in cities to come back to their hometown.

FORGOTTEN CORNERS

In the Greater Bay Area

by Zou LipengIn the rapidly urbanizing context, peri-urban regions often suffer the consequences of economic growth and urban expansion, leading to the marginalization of certain villages. Tonghu Town in Huizhou City, part of the Greater Bay Area, China, represents such a forgotten corner, facing contamination issues in soil and water. This project addresses the challenges by integrating plantbased remediation infrastructure with the public realm.

The primary objective is to introduce open spaces within farmlands, creating recreational and educational areas to reconnect residents with nature and facilitate immersive ecological education. Meanwhile, this project employs phytotechnologies to mitigate soil and water contamination, enhancing environmental quality and promoting resilient agriculture intertwined with sustainable economic output. Community engagement is a driving force in this project, involving close collaboration with residents to design landscapes aligning with their needs and values. By means of post-political methods such as community engagement, sustainability, and cultural preservation, this project seeks to breathe new life into the forgotten corners of Tonghu Town, establishing a multifaceted approach for revitalization and sustainable coexistence between agriculture and the ecosystem.

The first spatial strategy revolves around introducing communal spaces at the village level. These areas offer residents an opportunity to connect with the land and simultaneously act as hubs for ecological education. Initially, “natural classrooms” are set up, offering immersive experiences where both residents and students can delve deep into lessons about ecology, agriculture, and the broader environment. Furthermore, there is a push to intertwine cultural narratives with the land, prompting residents to showcase their bond with the land through artistic expressions, cultural engagements, and age-old crafts, weaving the land seamlessly into community traditions. Lastly, a principle of ‘co-building and co-sharing’ is promoted, encouraging villagers to participate in the planning, construction, and management of these spaces.

The second spatial strategy involves province-level governance and some imagined research institute investment in the technology of phytotechnologies. The initial step in this strategy requires the selection of suitable plants. Depending on the nature and level of soil contamination, plants such as reeds, sunflowers, and Indian goosegrass are preferred, owing to their renowned absorption and enrichment abilities. Next, the strategy introduces microbial remediation, deploying specific microbial communities, including select bacteria and fungi, which can break down or alter soil and water contaminants. The final crucial aspect of this strategy is the consistent observation and supervision of both plant and soil and water health, ensuring the remediation process progresses as intended.

In sum, this project strives to engage the community in a transformative journey and cultivate a peri-urban imaginary in Tonghu, encourage residents to actively participate and reimagine the interplay between humans and their environment based on cleaner soil and water. Through strategic implementations, this project aims to rectify the damages of the past while paving the way for a harmonious future where people, land, and culture coexist in a thriving symbiosis.

FORGOTTEN CORNERS

IN THE GREATER BAY AREA

FROM REMNANTS TO RESONANCE

Reimagine the Future of Coastal Fishing Villages

byOuyangLuomanIn 2011, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant leaked following the Pacific earthquake and tsunami. To avert environmental harm, Japan stored the nuclear wastewater. Recently, due to storage costs, they have opted to release it into the sea. This wastewater could spread globally via ocean currents, impacting areas like Choshi, Japan’s most productive fishing village.

Choshi is also ordinary, in the sense that all fishing villages along the eastern coast of Japan are already facing hardship, they are remnants of their former prosperity with aging population, declining agricultural productivity and fishing catch. Nuclear pollutants can permeate natural habitats and the human body through metabolism. Accordingly, discharge of nuclear wastewater has caused many public protests, including Choshi fishers and residents. My project is located in this peri-urban puzzle and offers another possible future, once that helps the residents transform their shoreline from a remnant to a landscape of resource, for both humans and non-humans.

The project adapts people’s affective density to their home landscape and activist density to the impending pollution as a tool to drive the transformation of the fishing industry. The overall goal is to design a way for people to stay and to refigure the landscape structure with them. The project is mobilized by built elements that improve in production density of fish product and decrease pollutant density.

The project’s initial phase envisions the formation of small inland fishing cooperatives by fishers and residents. They dedicate land to grow new vegetation for land and water remediation, yielding inland fish with improved sales and lower radioactive content. They success attracts more cooperatives. In the second stage, the “Remnant-Revive Collective,” involving fishermen, residents, and Choshi Fishery Cooperative Associations, emerges. They further rehabilitate resources, repurpose abandoned houses for fishponds, and enhance fish production and economic benefits. The parallel step, with government response, more resources are provided for inland fish farming. A comprehensive fishery system, from small to large ponds, is established, using terraced terrain to enhance fish taste. “Choshi fish” certification is obtained, and these fishes are sold to big cities. Fish ponds also serve as multifunctional spaces for elderly residents. As fishing villages thrive, landscapes for the next generation, such as sports fields and amphitheaters, gradually emerge.

In conclusion, the project underscores not only the economic benefits for residents but also the crucial importance of ecological enhancements along the coastal area. In the costal fishing villages in Japan, density will serve as an intangible force driving the evolution , creating a resonance among all these seaside communities in a way that is more than human. It will give rise to a new pattern of density that transcends human boundaries, delving into realms of practice, society, ecology, and landscape.

Fishing Villages

Oyashio Current

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant

Choshi

CHINA is the largest destination for Japanese agricultural, forestry, and fisheries exports

Point of contact between ocean currents Mixed water region/transition domain

The most productive fishing village in Japan

Outflow of peri-urban population

CHANGES IN THE ECONOMY DRIVE CHANGES IN SOCIETY

THE HYBRIDIZATION OF FISH PONDS OF DIFFERENT

896 towns and villages across Japan will no longer be viable

Spread of nuclear contamination

Due to the influence of ocean currents, nuclear wastewater disch from Fukushima will spread throughout the Pacific Ocean and the

By In In Days Years

2040 1200 10

The pollutants will cover almost the whole North Pacific region

The pollutants will cover almost the entire Pacific Ocean

FROM REMNANTS TO RESONANCE:

Reimagine the Future of Coastal Fishing Villages

CHINA is the largest destination for Japanese agricultural, forestry, and fisheries exports

The most productive fishing village in Japan

Outflow of peri-urban population

Kuroshio Current

896 towns and villages across Japan will no longer be viable

Spread of nuclear contamination

Due to the influence of ocean currents, nuclear wastewater discharged from Fukushima will spread throughout the Pacific Ocean and the world.

The pollutants will cover almost the whole North Pacific region.

By In In Days Years

The pollutants will cover almost the entire Pacific Ocean

CHANGES IN THE ECONOMY DRIVE CHANGES IN SOCIETY

LEGEND

Greenlands

Water

Woodlands

Plants that can be used for phytoremediation

Fish Ponds in backyards

Fish Feeding Land in backyards

Fishers and local residents with Affective density and Activist density

Paddy field

Farmland

THE HYBRIDIZATION OF FISH PONDS OF DIFFERENT SCALES

THE HYBRID OF FISHERIES AND LANDSCAPE:Reuse of abondened housing

Edge of the fish pond

Flooring for recreational areas

Reading and Resources

Crang, M. (2010). Visual methods and methodologies. In D. DeLyser, S. Herbert, S. C. Aitken, M. Crang, & L. McDowell, The SAGE handbook of qualitative geography (pp. 208–225). SAGE.

Easterling, K. (2021). Medium Design: Knowing how to work on the world. Verso.

ETH-Singapore Future Cities Lab. (2023). Agropolitan Territories of Monson Asia module. https://fcl.ethz.ch/research/ food-and-territories/agropolitan-territories-of-monsoon-Asia.html

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2016). Commoning as a postcapitalist politics. In A. Amin & P. Howell (Eds.), Releasing the Commons:Rethinking the futures of the commons (pp. 192–212). Routledge.

Girot, C. (1999). Trace concepts in landscape architecture. In J. Corner, Recovering Landscape: Essays in contemporary landscape theory (pp. 58–67). Princeton Architectural Press.

Haarstad, H., Kjærås, K., Røe, P. G., & Tveiten, K. (2023). Diversifying the compact city: A renewed agenda for geographical research. Dialogues in Human Geography, 13(1), 5–24.

Harley, J. B. (1989). Deconstructing the map. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization, 26, 1–20.

Hoey, B. (2014). A Simple Introduction to the Practice of Ethnography and Guide to Ethnographic Fieldnotes [Academic]. Marshall University Digital Scholar. http://works.bepress.com/brian_hoey/12

Kobayashi, A. (2009). Situated knowledge, reflexivity. In Rob. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (pp. 138–143). Elsevier.

Ledewitz, S. (1985). Models of design in studio teaching. Journal of Architectural Education, 38(2), Article 2.

Marshall, V. (2024). Periurban Cartographies: Kolkata’s ecologies and settled ruralities. Oro Editions.

Marshall, V., Cadenasso, M. L., McGrath, B. P., & Pickett, S. T. A. (2020). Patch Atlas: Integrating design practices and ecological knowledge for cities as complex systems. Yale University Press.

McFarlane, C. (2016). The geographies of urban density: Topology, politics and the city. Progress in Human Geography, 40(5), Article 5.

Sze, S. (2018). Sarah Sze: Timekeeper. Gregory R. Miller & Co.

March 2024

Victoria Jane Marshall marshall@nus.edu.sg

ISBN: 978-981-94-0160-4