Chapter 3: Methodology

3.1 case study

This paper aims to show the development of conservation planning in Singapore and the public’s perceptions of conservation by examining the evolutionofabuildingtype.Therefore,thestudyobjectshouldbeabuilding with a long history and a high degree of public recognition. However, the architecture in Singapore is complex and it is not isolated from other countries (Wong, 2022). As early nautical maps indicate, Singapore is a countrywhich isactivein tradeand portactivities. Asaresult,peoplefrom variouscountrieshavecometotheislandalongwiththeircultures.Therefore, Singapore’scurrentarchitecturereflectsthetracesofsettlerswhocamehere fromallover theworldin variousperiods.Forexample, manyarchitectural stylescanbeobserved:thebuildingsofMalay(e.g.Malaykamponghouses), Chinese architecture (e.g. Mun San Fook Tuck Chee), Indian and European architecture(e.g.oldParliamenthouse),andtheworksofSingapore'snative architects.Overtime,however,theseimportedculturesbegantobemerged and lead to Singapore’s complex styles of architecture with indigenous elements. As Walter (1999) states, the hybridization feature of Singapore’s architectureisnottheexceptionbutthenorm.Mixed-usebuildingtypessuch asshophousesdevelopedrapidlyinSingaporeinthe19thcentury.Although their origins can be traced elsewhere, thesebuilding typeshave undergone

significantlocaladaptations and modifications, becomeSingapore's earliest architecturalinnovationsandexports,andmarktheevolutionofanationand itsidentity.

Thefacadesofthesebuildingsshedlightonthecharacteristicsofthebuilding ownersandeventheirethnicroots.Basedontheinfluenceofthecolonizers in different periods, three main ethnic influences are identified: European classical style, Chinese style, and Malay style. In addition, there are decorations inspired byPeranakan, Indian, andArab. For example, theLate Shophousestyleiscalled Shophouse'smostprosperousperiodbecauseitis known for its rich and colorful details with a unique mix of architectural expressionsandmaterialsfromdifferentpartsofAsiaandEurope(Liu,2017).

Thearchitecturalstyleof Rococo is formed bytheincorporation of Chinese decorativeelementssuchasflowersandtheChinesezodiac.Thisstylecovers the facade with as many decorations as possible and has inclusive and sophisticatedstyles.TheEuropeaninfluenceisreflectedfirstandforemostin theclassicalformofthecolumns,theDoricpilastersatthebottom,theIonic pilasters atthetop, and theCorinthian pilastersatthetop (Davison, 2010).

Diverse materials have been used: apart from the usual lime and timber, hand-carvedwoodworkandNyonya-styleglazedceramictilesareemployed.

The superb craftsmanship adds to the architecture’s uniqueness. These ethnicallyinspiredarchitecturalelementsdecoratethebuildingswhichhelp

present a lively street that combines the creativity of different colonial periodsandcontainstheaspirationsandideasofdifferentperiods.

The study of shophouses, therefore, can offer valuable information on not only the evolution of conservation practices over time but also Singapore's architecture under the multi-ethnic influence. The information for the shophouseswasobtainedfromsecondaryresearchsourcesbasedononline resources and printed publications. Specifically, the information was collected and critically analyzed to help understand the importance of shophouses to heritage conservation and the evolution of conservation practicesinSingapore.

3.2

Interviews

3.2.1. Purpose of the interview

Theinterviews aim to gather thepublic’sandprofessionals’opinionsofthe current conservation system in Singapore. Examining their conversations allows me to identify various aspects of perceptions that encourage or discourage such a conservation system based on their backgrounds and experiences.

3.2.2. The design of interviews

Togatherinterviewdata,purposivesamplingwasadoptedtoobtainin-depth information from those who are able to provide and elaborate on the information (Cohen et al., 2002). To collect data relevant to the research objectives,theintervieweeswereselectedbysettingthefollowingstandards: (1)peoplewhoarefamiliarwithshophouses(e.g.,havingparticipatedinthe renovationoftheshophouseorhavingstudiedtheshophouseacademically, or having rented or being rented a shophouse) (2) people who own a shophouse.

Basedonthesecriteria,Irecruited2tourists,2owners,1tenant,1architect, 1designer,1architecturestudent,and1artist.Theywereinvitedbyemailor randomlyaskedonthestreet.Individualinterviewswereconductedsothat people feel freer and more openly to discuss and express their opinions (Cohenetal.,2002).Ingeneral,apartfromthebasicbackgroundinformation questions, some questions were asked to guide the interviewees to share their views onshophouses. Moreover, to furtherdelve into the inquiryinto interviewees’ opinions of shophouses, all interviews conducted were semistructured:theorderoftopicscouldbechangedbasedontheirresponsesand a wider range of information could be obtained (Gray, 2004; Robson & McCartan,2016).

The public, such as residents and tourists, are more concerned with what convenience the buildings may bring to their lives. For example, they favor the functionality and convenience of shophouses. The interviews with architects, designers, and architecture students focused on the potential benefits and challenges that the conservation system could have in real projects. This group of interviewees was purposefully selected from those whose work or experience is related to shophouses. These interviewees highlightedmoreprofessionalpracticalissuessuchascostsandconstraints, andtheconflictsandbalancebetweenmodernarchitectureandoldbuilding conservation.Duringtheinterviews,intervieweesalsoofferedtheirinsights intosomeofthechallengesfacedbyvernaculararchitectureinrelationtothe high-tech and sustainable topics of modern architecture. Both types of interviewersofferedinsightsfromdifferentperspectives.

Chapter 4: Finding

This chapter presents findings according to the research questions. Section 4.1 first shows how shophouses were introduced in Singapore and underwent localized changes before being incorporated into national planning and conservation. Following this, section 4.2 presents specific conservation measures for the country, the street (district), and the individualbuildings.Section4.3isadiscussionofthesubsequentchallenges regarding the reuse and contemporary value of shophouses when the conservationrangeisextended.

4.1 localization of Shophouse

Shophouses, a form of vernacular architecture, are common in Singapore nowadaysaswellasinsomeothercitiesinSoutheastAsia.Itsorigincanbe tracedbacktotheQingDynastywhenChinaopenedfiveportsofcommerce. AstheQinggovernmentlifteditsseabanpolicy,agreatnumberofpeoplein China's coastal cities started to go abroad. These include many traditional famous craftsmen from southern Chinese cities, and they have brought traditional building materials and techniques abroad and built buildings featuringtraditionalChinesearchitecturalcultureintradingportcitiessuch as Malacca, Penang, and Singapore (Tian, 2018). With regard to how

vernacular architecture and conservation approaches have been updated over time, this chapter examines and discusses a study of shophouses’ developmentinSingaporeinthelocalcontext,abriefhistoryofshophouses, andtheirlocalizedresponsestoclimateanduse.

4.1.1 Response to climate - change of building form

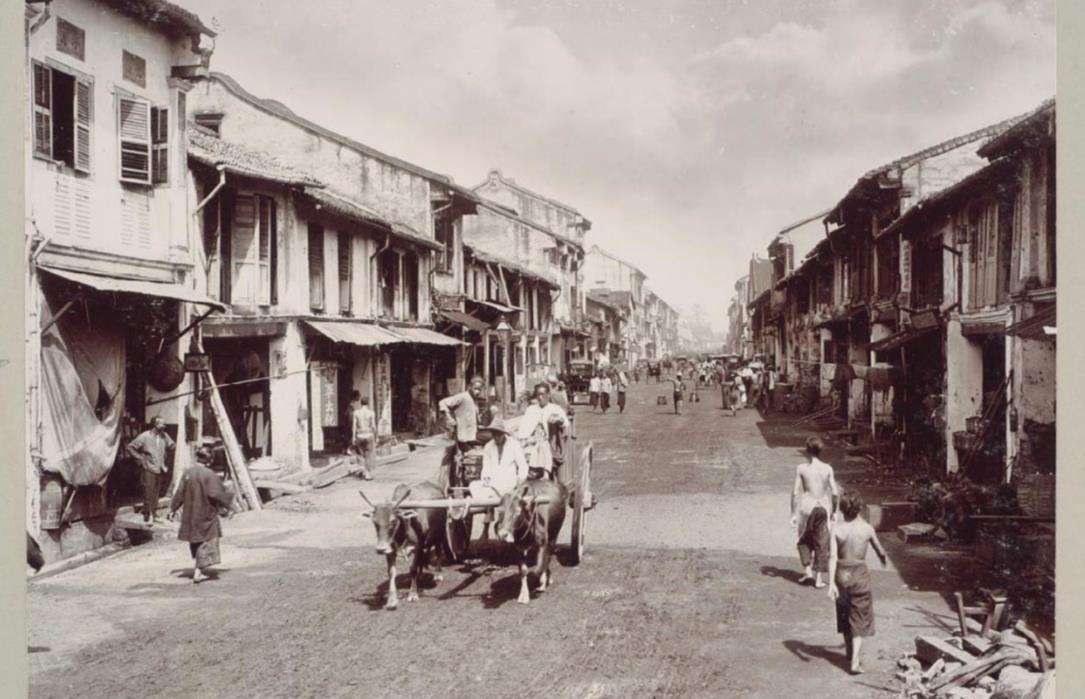

In terms of the early individual Shophouse buildings, their façade is simple and similar. That is, they are pre-industrial mass-built residential and commercial buildings without significant architectural and artistic value in today's heritage conservation field (see Figure 1). An important breakthroughintheevolutionofShophouse'slocalizationisthesearchforthe development of a vernacular form of architecture which is suitable for Singapore's tropical climate. Although today's modern buildings are almost formally independent of climatic conditions due to the superiority of technologyandenvironmentalcontrolsystems,vernaculararchitectureisan exception,anditisconstructedtosuitthelocalclimate(Sayigh,2019).

1: Old photographs showing the early shophouses in Hokkien Street in the 1890s.

Specifically, uniformchanges weremadebyRaffles to theShophouseinthe earliest urban plans, and continuous five-foot paths were created to withstandtheintenseyear-roundsunexposureinSoutheastAsia.Thepaths soonbecameanimportantfeatureofSingapore'suniqueshophouses.There werealsoalterationstopartssuchasdoors.AsDavison(2010)describes,to allowthemaindoortostayopenduringtheday,somestoresusedapairof half-length doors, also referred to as pintu pagar, to close the lower partof the doorway. This change helps promote natural ventilation in the house whileensuringtheprivacyoftheresidents.Shophousewindowsareusually fitted with a tie rod panel on the lower part of the window. These panels’ functionissimilartopintupagar,providingprivacywhileallowingairtoflow

Figure

through the interior of thehouse (Davison, 2010). In Singapore with a wet climate,theroofisangledmoresharplytoresistrainwaterfromenteringthe houseandaccumulatingontheroof.Thisarchitecturaldesignalsocreatesa higher ceiling height in the interior, enhancing internal airflow. The roof is supported by both walls. Because of the narrow and long character of the shophouse,thereisusuallynoneedforanymiddleverticalsupport.Mostof thewallspaceisreplacedbycolumnsorpilasters,whichreduceswallspace. Inthepast,becausetherewerenouniformstandardstoguidethemonhow to remodel buildings, early Shophouses were often remodeled at the homeowner'sownwill.ThismeansthattheearlyShophouseshadaflexible architectural form and building structures were allowed to be reinforced, shifted, or replaced. Timber supports and brickwork walls rather than concrete buildings as in modern architecture could be used. The flexibility andadaptabilityofthebuildingitselfisalsothereasonwhypeopleareable to change architecturally so that it can respond quickly to the weather. By contrast,Le(2010)pointsoutthatmoderninteriorspaceshavebecomemore separated and specialized according to functionalzoning in modern houses andthatthehousehaslostitsflexibility(seeFigure2).

Figure 2: Key element of a typical shophouses.

4.1.2

Response to Climate - Application of Materials

Theinitialconstruction of theshophouses in the18th centuryin Singapore wasmainlybyChinesecontractors,andthusthearchitecturalstyle,materials, and constructionmethodstend to bethosepopular in China(Chang,2009).

Rather than using formally educated architects, ordinary artisans’ design skillsandtraditionswereadopted.However,thematerialsusedinvernacular architecture should be sustainable and local materials and local craftsmen shouldbeusedtothefullestextentsothatthebuildingscanbewelladapted to the local environmental conditions. The roofs were first made of locally producedclaytiles.Thefloorsandfive-footwaywerethenpavedwithlocally made floor tiles set in a lime mortar that allowed the damp earth below to

evaporateandthegroundfloorroomstobecooledintheprocess(Davison, 2010).InordertoadapttotheclimateofSoutheastAsia,airbrickswhichhave better insulation properties were used for the exterior of shophouses (Davison, 2010). Moreover, indoor items such as bamboo curtains and bamboostoolsareselectedfrommaterialsthataresustainableandtolerant of the local environment. Today, Singapore's shophouses shed light on Singapore'shistoryandareexamplesofvernaculararchitectureresponding to thetimes.Italsotosomeextentproves thatadoptingbuildings basedon localcontextscanbeeffectiveandfruitful.

4.1.3 Summary

As Posener suggested at a 1953 conference on the history of tropical architectureinEngland,itisnothowabuildinglookslikebuthowitproperly functions in the tropics that makes it a meaningful building. "Formally, vernaculararchitectureadaptstolocalarchitecturalandculturaltraditions; conceptually, modern architecture adapts to local climatic conditions and living patterns". This sustainable development process is well reflected in Singapore.VernaculararchitectureinSingaporewasgivenvalueatthisstage because of the shift towards localization, and the idea of architectural conservation and maintenance began to emerge during this period. From a conservation perspective, the Raffles plan also proposes 20-foot protected

alley every 200 feet, with an emphasis on fire protection. From an urban planningpointofview,itisimportanttoensuresufficientinteriorspacewhile ensuring the unity and uniqueness of the building's front façade. This was Raffles'earlyplanning thought, andtheoveralluniformityof Shophouses is thekeyandprovidesthebasisforfuturethinkingofconservation.

4.2 Study of Singapore conservation with shophouses

Thispartillustratesthebeginninganddevelopmentofconservationon shophousesandopportunitiesandchallengesinrelationtocitystreets.

4.2.1 Dividing conservation districts - the beginning and development of conservation

Intheearlyyearsofindependence,rentcontrolwasintroducedinSingapore due to a severe shortage of housing (Khublall and Yuen, 1991). The governmentemphasized issuesof inflation, economicsurvival, and housing supplyratherthanhousingmaintenance.Asaresult,manyshophouseswere dilapidated. The views about redevelopment and conservation at that time werefirstobservedinstatementsdeliveredbyAlanChoe,thefirstdirectorof theUrbanRedevelopmentAuthority.Initially,Singaporeconsideredheritage conservation to be secondary, something that could be prioritized by

developed countries. At this time, Singapore's master plan prioritized the development and believed that only after the country achieved economic stabilitycouldtheauthoritiesbegintofocusonconservationissues(Yeohand Huang, 1996). Mostof thesedilapidated shophouses in the central districts were considered to be slums and were demolished to make way for urban redevelopmentandpublichousingprograms(Sim,1996).Itwasnotuntilthe formalestablishmentoftheMonumentConservationCommitteen1971and theURAin1974thattheneedforconservation andrenewalworkbegan to berecognized.TheURArecognizedthatthepreservationofhistoricdistricts adds diversity to the landscape of Singapore (Lee, 1996) and therefore recommended thatlocalculturaland historicalvalues should bepreserved. Moreover, the URA admitted that the demolishment of many historic buildings in the past resulted in the loss of important heritage and culture (KongandYuen,1994).AsLichfield(1998)speculates,conservationrequires carefulconsiderationofboththepaceofdevelopmentandtheconservation ofhistoricallysignificantbuildings.

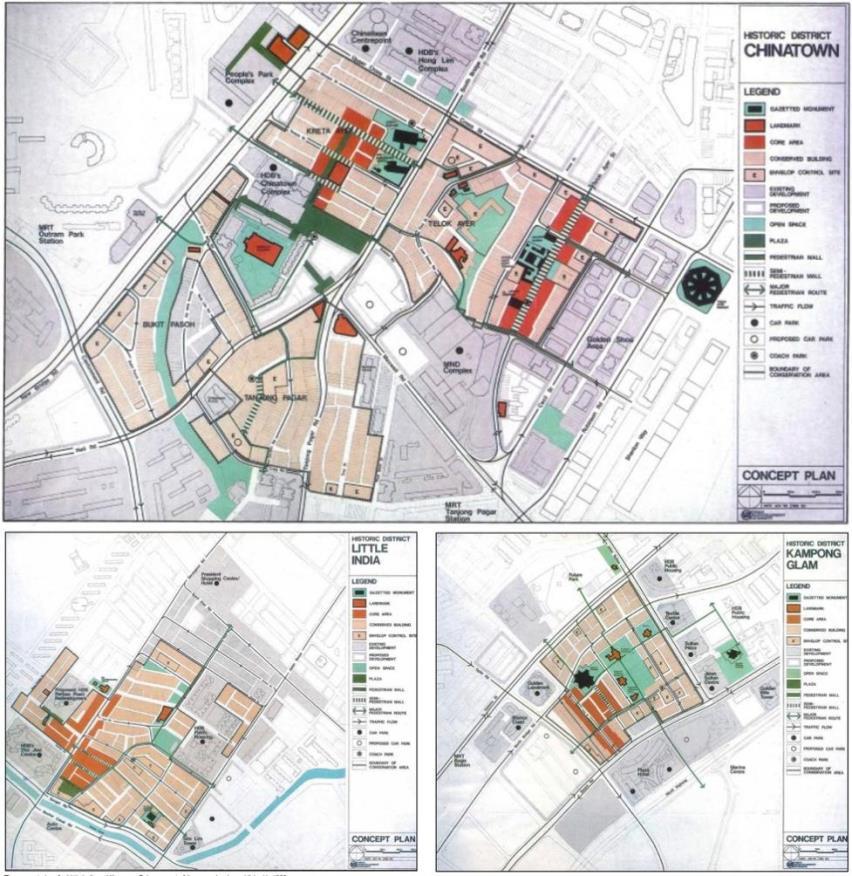

Asaresultoftheincreasingawarenessofthesignificanceofconservationin 1988, Singapore launched a conservation master plan and 10 conservation areasinthehistoricdistrictssuchasChinatown,KampongGlam,LittleIndia and Singapore River were declared as conservation areas. The most importantofthemaretheoldshophousesinChinatown,KampongGlamand

Little India (see Figure 3). These areas have been further expanded as Singapore's urban development strategy has shifted from the initial literal designationofhistoricconservationareastoallareasthathelppromotethe local culture of the city. In particular, shophouses have been viewed as vernacularbuildingsthatdeservetobeconservedduetotheirhistoricaland culturalsignificance.Theyareauniquearchitecturalformwhichisdifferent fromthehomogenizationofhigh-densityarchitectureintheurbanjungle,and they"createahumanscale,rhythm,andcharm"thatdoesnotexistintoday's architecturaldesign(URA,1985).

Figure 3: Conservation plans for three historic districts launched in 1998.

4.2.2 City Streets - Opportunities and Challenges

Asstatedinthepreviousliteraturereview, identityisanimportantelement that distinguishes a city from others. As UNESCO (1996) states, urban heritage provides valuable information on the history of a city, its neighborhoods,anditsinhabitants.Asatypeofurbanheritage,streetsserve notonlyasfunctionalcirculationchannelsforthecitybutalsoreflectthelife of thecity. As Jacob(1993)says, citystreets are thearteries to theheartof thecity.Inadditiontothephysicalcharacteristicsofpublicspace,streetsshed light on the political, social, and cultural phenomena underlying urban life. Eveninidenticalresidentialareaswithhigh-risebuildings,shophousestreets bringstothecitymorecreativityandpersonality.AsURA(1985)states,the facade of shophouses in Singapore demonstrates a creative approach to multiculturalism and the colorful combination becomes one of the city's symbols.Itisalsoanimportantchannelforexpressingacommunity'sidentity, ideas,andaspirations.

TheshophousesonsecondarystreetssuchasJooChaitRoad,HajiLanewere built in different periods, but they are within the same street block, which formsacolorfulpicture(seeFigure4).Thisrhythmisalsoattributedtothe visualandtactiletexturesbroughtbycolumns,pilasters,curtains,balconies, and decorative objects. Since the first shophouse was built, it has gone throughatleastfourdifferentphasesofconservationanddifferentbuilding

heights,roofshapes,windowtreatments,anddecorationswereincorporated (Lee,2003).Inthelate1980s,however,whenmostoftheshophouseswere listed as historic buildings and divided into conservation areas, their authenticity was rather undermined. To protect the authenticity of shophouses and encourage the expression of its individuality, since 2000, rules have been relaxed and developers are given more flexibility in modifyingexteriorcolorsandfaçadedetails.AsAkagawa(2016)argues,both tangible and intangible heritage are equally important; attributes such as authenticity and sensation are not easily applied practically but are still importantindicatorsoftheidentityandattractivenessofaplace.

Figure 4: This charming Joo Chait Road is rich with Peranakan culture and architectural heritage.

4.2.3 Single building -Detailed shophouse conservation process

TheregulatoryrestorationoftheshophousesbeganwithURA'spilotprojects forshophousesinKampongGlamandLittleIndia.Intherestorationofthese shophouses,atop-downapproachfromtheroof,upperfloor,lowerfloor,and floortotheexteriorwallswasused.Beforeinitiatinganyconservationwork, thebuildingsbeingconservedarethoroughlyresearchedanddocumentedto ensuretheeffectiveimplementationoftheconservation.

Thefirststepistherestorationoftheroofandupperfloors.Theroofisusually a pitched structure over a timber frame, and it is usually covered with natural-colored, unglazed V-profile terracotta roof tiles (see Figure 5). However,mostoftheterracottatilesofthistraditionalroofareeasytocrack. Moreover, they must be replaced to prevent them from falling off when repairingthestorefront.Replacementshouldbedonewithuniformlycolored V-shaped terracotta roof tiles or unglazed flat-interlocking tiles (i.e., "Marseille" tiles) (see Figure 6). These tiles became popular in the 20th century and their use aims to ensure the uniformity of color. The latest method is to lay a new metal plate on the timber structure of the roof beforehand,whichismoreinlinewiththeV-shaped profileof thetiles (see Figure7,8).Thismethodenhancesshophouses’safetyandwaterresistance andeffectivelyprotectsthetimberstructureundertheroof.Aftertheroofis repaired, the focus is put on the upper space. First, the upper wood floor

shouldberemovedtochecktheconditionoftheentiretimberjoist.Ifitisin good condition, the floor should be put back in. In case of decay, the entire timberjoistcanbefirstremovedfromoneofthewallswithnomorethantwo joistsremovedatatimeforhorizontalstability.Therestofthestructurecan then be easily repaired accordingly. For example, cracks, tilting, and plant growththataffectthesafetyofthestructureonthewallshouldbedealtwith in a timely manner (see Figure 9). Moreover, the same elements should be usedforreplacement.Forexample,thebrickmaterialshouldbesimilartothe originalbrickintermsofshapeandcolor.Therestorationofstructuresand partscanbecarriedoutsmoothlyaslongastheURAguideisfollowed,which meanselement-basedreplacementcanalsobecarriedoutandnewmaterials canbeblendedintotheoriginalstructure.

Figure 5: V-profile terracotta roof tiles

Figure 6: "Marseille" tiles

However, most new shophouses have performed more than the simple residential function of the original. For example, new buildings need to consider loads and fire safety regulations. By adding fireproof insulation underneath the upper floor or fire retardant treatment of timber, the requirementsoffiresafetycanbemet.Someshophouseshavechosentoadd

Figure 7&8: Laying new tiles on metal deck.

Figure 9: Wall damaged by plant growth.

aspiralstaircasetotheirbackyardstomeetfireescaperequirementswithout destroying the interior space (see Figure 10). In order to meet the loadbearingcapacityrequiredforthenewcommercialandofficeuses,additional structural support is also required for the upper floors. The method is to strengthenthejoistsbywideningthetimberjoistsontheupperfloorsorby adding joistsbetween existing structuralelements. However, in theprocess ofrepairingandstrengtheningbuildings,itissufficienttominimizemodern interventionandmaintaintheoriginalforcebalanceandstructure.

The ground floor space is the last part to be repaired in the top-down approachadoptedbytheURAintherestorationofshophouses.Thespaceis alsothemostseverelydamagedspaceduetonaturalreasonsandhumanuse.

Figure 10: Baba house's spiral staircase.

Itcanbebetterrestoredthroughanin-depthunderstandingandanalysisof theenvironmentandtheinherentcharacteristicsofthematerialsusedinthis shophouse.Forexample,brickwallsthatareindirectcontactwiththeground needtoconsiderissuessuchaswaterpenetrationandsettlement(seeFigure 11). Moistureis the core cause for brick and timber damage such as cracks andcorrodedtimberbecausemoistureisnotonlypresentintheairbutcan also seep into the walls from the ground. If the surface of a brick wall is covered with concrete or other impermeable material, the moisture inside the brick wall will be prevented from exiting the wall and finding another outlet such as timber (see Figure 12). Therefore, lime-based plasters and porouscoatingsareusedintherestorationofthewallstogiveflexibility,and allowbetterevaporationofthewaterthatpenetratesthewalls.Timberisalso susceptibleto pests such as termites when wet. For thosealreadysuffering fromfungalandinsectdamage,chemicaltreatmentscanbeusedtoenhance thestabilityandresistanceofthetimbertopests.Intermsofthehandwood carvings that decorate the facade, the beauty of the storefront and its weatheringcharacteristicsareretainedeventhoughmostoftheirstructures havedeteriorated after being exposedtothenaturalenvironment.Itcan be coated with an anti-decayagentto enhanceits abilityto resistdecayandto ensureventilationanddryness.

11&12: Diagram of the effect of moisture on walls.

In summary, Singapore attempted to preserve and restore all original structuralandarchitecturalelements.Anyreplacementofpartsandupgrades should use the original methods and materials whenever possible. Rather than simply replacing them with modern materials, traditional materials werekeptinshophousesduetotheireffectiveness.Notonlyshophousesbut also other conserved buildings should be repaired according to the 3R guidelines. That is, maximum Retention, sensitive Restoration, and careful Repair regardless of their size and complexity. This is Singapore's conservationapproachwhichincorporatesitsownregulationsbasedonthe internationally recognized conservation principle of authenticity. The restoration of these shophouses demonstrates the responsiveness of vernacular architecture to maintenance and new technology. Overall, it is shown that thecombination of existing and newskills, past knowledge and currenttechnologyensurestheeffectiveimplementationoftheconservation.

Figure

4.2.4 Interviews

The majority of interviewees were selected from groups with direct or indirectcontactwithshophouses.Someofthesepeoplelivedandgrewupin shophouses and were directly affected by urban regeneration. Some interviewees were randomly selected tourists. I conducted a one-to-one interviewwiththemforabout20minutesandconcludedtheirideasrelevant to this paper. The interview questions were raised around the topic of shophouses including their views on conservation, urban regeneration, and whetherthereusednewfunctionswereintegratedintothelocalcommunity. Overall, their authentic views on the conservation of shophouses were gatheredwithoutbeingoverlyledbytheinterviewer. Theopinionsgatheredininterviewswithresidentsaregreatlydifferentfrom theviewsoftourists.Residentscomplainedaboutthelossoftheirlivingspace, especially those living in the historic district. They further mentioned that their living space was already occupied by tourists, especially before the Covid19.Forthem,thesebuildingsarenotsimplyarchitecturebutthebasis oftheirsocialrelationshipsandidentity.AstheresidentTanfromChinatown said, mostof theshophouseshaveto bereconstructed becauseof their bad state and the renovation has helped to improve the quality of the neighbourhood.Someresidentsmentionedthatsomeshophousesthathave been properly conserved have also become more valuable and have contributed to the economic growth of thesurrounding area. However, the

urbanregenerationhasaffectedtheoriginalcommunitystructureandsome residents aredissatisfied withsomeofthegovernment's commercialization of the conservation. As the resident Tan complained: “it used to be a residentialareaand nowit's acommercialarea”. Moreover,dueto thehigh rent,manyresidentsrentoutroomsinashophousetodifferentpeople.The landlordof ashophouseinJoo Chiatrecalled thatin thepastthestreetwas morecrowdedandlivelyasresidentsalwaysgatheredforsomeactivities.The landlordaddedthathenolongerlivedhereandtheplacecouldnotbringthe homelyatmosphereforhimasitoncedid.Althoughthegovernmenthasmade someeffortstoinviteartgroups(suchastheKatongJooChaitArtCircuit)to perform,accordingtothislandlord,thosearteventsareheldfortouristsand caterforyoungpeople’stastesandthuspeopleofhisagecannotappreciate their performance. But tourists were delighted with the way the historic buildingshadbeenrestoredduetotheirnewfunctionsandartisticactivities introduced. For example, the touristCui commented that thebuildings that areingoodconditionmakethestreetslookclean.TouristsMaxsaidthatthe functionality of the interior of buildings and the services offered were importantbecausetheycametheretoeatorconsumeratherthanlearnabout storiesbehindthebuildingsandhowtheoldbuildingswereadapted.Instead, itistheartisticatmosphereandanumberofartisticeventsthatattractthem to revisit the area. These different perspectives reflect different groups'

feelingsofbelongingtotheshophousesandthehistoricenvironmentaswell asdifferentperceptionsofchangesinthecityasawhole.

Thegroupofarchitects,designers,andarchitecturestudentsinterviewedare relativelyyoungandnotawareofhowtheshophousesarechanged.Buttheir expertiseinarchitectureenablesmetoexplorethedetailsoftheconservation and reuse of Singapore’s shophouses as well as their contemporary value beyond their role as the architectural heritage from a more professional perspective.Forexample,aninteriordesignermentionedthatadaptivereuse designs for shophouses are relatively complex as the design of conserved buildings is often restricted by strict regulations. For instance, they cannot randomlydividetheinteriorofashophouseeitherverticallyorhorizontally. This is because according to the law, in areas, especially those that are the historic cores of the conservation, shop signs, air conditioning units, back alleysandsofortharenotallowedtobemodified.Inaddition,theinteriorof shophousesisdesignedaccordingtotheirowners’will.Therefore,evenifthe designer suggests a theme that fits the design of historic buildings, some owners may decline the suggestion due to the consideration of costeffectiveness. Moreover, most of the shophouses have been resold several timesandhavelonglosttheiroriginalstoriesandhistoricalconnotations.

Regardingthedesigner'sviewonstrictregulations,onearchitecturestudent expressedsupport,sayingthatsafetyshouldbeprioritizedandalonger-term view should be taken whether in renovation or conservation work. Furthermore, she mentioned that only a limited number of students now devote themselves to designs with conservation and emotional values and that many architectures focus more on advanced technology and the presentation of cooler architectural effects. That said, when I asked the architect about his views on traditional buildings such as shophouses and whethertheyhaveanycontemporarysignificancebeyondtheirconservation value, one of the architects, Chen, mentioned that they study vernacular architecturefor inspiration whendesigning buildings, especiallyresidential projects. This is because vernacular architecture’s adaptation to tropical climatesbringslong-termbenefitstotheenvironment,particularlyinterms ofenergysavingsandcarbonemissionreduction.Itisalsomuchhealthierto use natural ventilation than mechanical ventilation, which concerns the heatedtopicofgreenandsustainablebuildingsinSingapore.

In general, the majority of interviewees demonstrate a positive attitude towards the conservation of single shophouses and the conservation of heritage in the urban context. Although some complained that their old lifestyleshavedisappeared,theyadmittedthattheycouldbenefitmorefrom the new development of the city. For example, the conserved shophouses

havebecomeanationalsymbol, which makes them beproud.Asoneof the artist interviewee indicates, she wished to promote the attractiveness and culturalvaluesof traditionalarchitecturein publicthroughherpaintingsof Singaporean architecture. In the Singapore context, the expansion of the conservation programme not only preserves Singapore’s cultural diversity but also increases residents’ and tourists’ awareness of the values of the various aspects of the buildings as the historic districts comprising the conservedbuildingsbecomeanintegralpartofSingapore'stourismindustry.

4.2.5 Summary

Fromtheoverallurbanplanningtothecontrolofstreetstotheconservation of single buildings, it can be seen that shophouses occupy an important position.Theapproachtoconservationisadaptedtothecontextofthetime inwhichittakesplace,asconservationencompassestheprincipleofchange and progress towards a better and evolving environment, not just the maintenance of old buildings (Kong and Yeoh, 1994). In the historic conservation district, weshouldavoid bigdemolition and construction, and instead adhere to the concept of people-oriented, respecting the cultural heritage,returningtolife,andstimulatingvalues.Conservationofimportant buildingswhilepreservingplacesofmonumentalsignificance,characteristic spatial patterns, street scale, community atmosphere, etc. On the basis of

guardingthecorevaluesandlocalcharacteristicsofthecity,innovativeurban space is created with dynamic development and refined creation. Give the community some power, as businesses can draw inspiration from some cultural connection to the local community (Santagata, 2002). Despite the government's successful conservation efforts, Kong and Yeoh (1994) argue that further policies and initiatives are needed to preserve the intangible aspectsofthesebuildingsinadditiontotheconservationofthetangibleones.

4.3 Learning from Shophouse

Afterstudyingandevaluatingthenewandoldpartsofurbanplanning,Prof. BenoitandDr.ElenafromFranceindicatethatwhethertraditionalbuildings returntothecityareworthwhile,theyhavethepotentialtoinformusofhow tobuildourbigcitiesnowadays.

There are harmonies and challenges in terms of the relationship between modern technology and tradition. The values of traditional architecture as well as modern architecture are recognized by many people. For example, traditional architecture can be designed in a modern way by using appropriatemoderntechnology.Buttherearealsochallengesthatarisefrom the need for a higher living environment and quality of life as well as the processofbalancingadvancedideaswithlocalortraditionalaspectsfromthe

ancestors(Abusafieh,2019).Therefore,acrystallizedaestheticthatispassed down from generation to generation without changes is argued against by Wright (2003) and vernacular architecture is updated to suit the changing needsandtimes.

4.3.1 Adaptive reuse of Shophouse

Thephrases“newusesneedoldbuildings”(Chang,2016)and“oldbuildings requirenewuses”(Jacobs,1993)highlighttherelationshipbetweenhistoric buildingsandtheirnewuseinthecityandhowtheyreinforceeachother.In the urban renewal process, there are some challenges. For example, the traditional trades and activities that used to occupy old buildings are not always viable due to changing market demands. The commercialization of shophousespromotesanewlifestyleandthereforenewactivitiesareneeded inthesebuildings.Inthiscontext,thetopicofadaptivereuseofshophouses, whichisapragmaticapproachtoconservationandallowstheexistenceofold andnewelements,becomesrelevantandsignificant. Fewplacescanresistthemonetarylureoftourismintheprocessofeconomic development. Therefore, it is understandable that the country creates elaborateimagesandformulatesmarketingstrategiestoattractvisitorsand meet their needs (Chang, 2016). To be specific, many shophouses in

Singaporehavebeen reused in theprocess forpurposes such as hotels and restaurants.Moreover,weshouldnotethatshophouseswhichareattherisk of losing their historic values in the midst of rapid development are not a unique phenomenon in Singapore. For example, in the Wan Chai district of Hong Kong, efforts to preserve the historic district have been initiated by residents with the help of the media and local architects (Youngs, 2006). Residents prepared a development plan, and it was submitted to the governmentasanalternativetodemolition.Althoughtheplanwasofficially rejected,someofitselementswereadoptedbytheauthorities.Forexample, sometraditionalTongLauwerepreservedasspacesforculturalandcreative industries in tourist attractions with the themes of medicine and tea. As opposedtocreatinganewindustrialdistrict,inthiscase,localarchitectureis considered most durable because traditional practices are combined with newforms,resources,andtechnologiessoastobebothenvironmentallyand culturallysustainableforfuturearchitecture(Vellinga,2006).Additionally,in Georgetown, Malaysia, the most densely populated shophouse in Southeast Asiacanbefound,whichretainingitsoriginalelementsandusingnewforms to provide many convincing examples. Because of the understanding and long-termplanningofconservationbygovernmentandprivatesectorefforts, local NGOs such as the Penang Heritage Trust, Nanyang Folk Culture Association, and the media are all working for the conservation of heritage (Tan, 2016). There are also some unsuccessful attempts to conserve the

urban vernacular in different countries and they are documented in The Disappearing 'Asian' City byLogan(2002).Thefailuremaybebecausethese countriesfailtoconsiderlocalcommunitiesasnecessaryandusefulinlongtermplanningandarelostinrapiddevelopment.

PrivateownersandpropertydevelopersinSingaporearealsoencouragedto restore their own buildings under the Conservation Initiated by Private Owners' scheme (1989). This program is in turn regulated by the URA Conservation Guidelines, which guide owners, architects, and engineers in making independent and appropriate restorations. In other words, all structuralchanges,includingstorefrontinteriorandexteriorwindowfixtures, building colors, awning use, and lighting, must be approved by the URA. In addition to being in charge of the regulations, the URA believes that shophouseshaveanideologicalandeducationalrole,althoughnotallofthem adequately perform these roles. The government still argues that historic buildings help strengthen Singaporeans’ sense of national identity and belongingbecauseof"anappreciationofourheritage"(MICA,2000).Inother words,Singaporeans’ nationalidentityis strengthened becauseofthevalue oftheirheritageandtheyrecognizetheirnationalidentityinthediverseand modernurbandevelopment.

4.3.2

Application of vernacular language in modern architecture

The housing in Singapore has evolved from the early vernacular low-rise villagestothemodernisthigh-riseresidentialareastoday.Todate,over80% ofSingaporeresidentsliveinhigh-riseresidentialcomplexes.Moreover,the youngergenerationcurrentlylivesandgrowsupinthesehigh-risebuildings and they may become the new vernacular of Singapore. As the transition betweentheoldandnewaccelerates,theever-changingenvironmentposes a challenge for architects to identify suitable architectural language to represent the nation’s identity. They need to ensure that local, urban, and internationalinteractions can berepresented inaspecifichistoricalcontext (Su, 2009). They also need to consider how modernist techniques can be combined with a specific culture and context to create a new architectural languageratherthanpurelyatraditionalvernacularstyle.

The design of buildings that suit the tropical climate has been a feature of shophouses, but the use of technology enables architects to be less constrainedbytropicalconditions.AsTzeLingLi(2007)illustrates,theuse of air conditioning has greatly reduced the use of shophouse doors and windows to 4.7%. On the other hand, in relation to modern architectural design strategies, experiences can bedrawnfrom traditionalshophousesto cope with thehot andhumid climate in Southeast Asia. For example, in the design of contemporarygreen buildings in Singapore, verticalventilation is

often provided through vertical spaces such as atria, shafts, and stairwells. Additionally,thehugeverticalpatiointhemiddleofSkyville'sbuilding,which is similar to the concept of a traditional shophouse patio, helps create a chimney effect that promotes vertical airflow. The manager of the Housing DevelopmentBoardBuildingResearchalsoindicatesthatinteriorcourtyardstyleblocklayoutscanalsobeseenintownssuchasBishanorTampines,and this design layout is adapted from the interior courtyard of vernacular shophousestoensuregoodnaturallightingandnaturalventilation.Thereare alsoopen corridors alongeach floorof theHDBflats, which areinspired by the five-foot way, enhance natural ventilation, and provide shade for the corridor units. In addition, the applications of the traditional roof language canstillbeobservedinanumberofmodernlow-risebuildingswithextended sloping or flat roofs which performs the functions of shading and rain protection. Moreover, some traditional building techniques are now modernized but their design purposeremains thesame. For example, onekeypurposeis to maximizethelevelofcomfortforresidentsbyprovidingnaturalventilation, shade, and light. Taking materials, for example, Singapore's vernacular architecturemostlyusesnaturalorganicmaterialssuchaswoodandbamboo to makebreathablepartssuchasbamboocurtains andgrilles,andeven the flooring is made of bamboo and wood with multiple gaps. This traditional

porous natural material is used to build open and ventilated vernacular buildings in hot and humid tropical climates. However, these materials are difficult to be reused in most contemporary buildings. That said, modern materials(e.g.,perforatedmetalpanels)thatarebreathablecanbeused.As inthecaseofTanQueeLanSuitesbyWOHA,aconservedmixed-useproject, the design of the building façade has a strong connection to the traditional shophouselife.Aftertheadaptivereuseofthesixshophousesinthefrontrow, thebackrowisdeveloped.Theuseofstructuralframingofaluminumpanels emphasizes the vertical profile of the facade, and this metallic material reflects the influence of modern architectural styles. However, when the metal panel windows are opened, they resemble in form the shutters of traditionalshophouses,whichpresentsavisuallinkbetweenthenewandthe old. This application of principles from vernacular architecture shows that vernaculardesignprinciplesarestillusefulandfeasibleinamoderncontext. Inotherwords,traditionalarchitecturecanbeadoptedandadaptedforuse inamoderncontext.

Chapter 5: Conclusion

In terms of research findings, based on previous research and interview data, several conclusions in relation to the conversation values of the shophouses can be drawn.

5.1 The conversation values of the shophouses

Architecture is representative in nature and is a source of the public’s imagination and depiction of ethnicity (Lim, 2013). The vernacular architectureof theshophousesnowforms animportantpartofSingapore's architectural heritage and is representative of its multi-ethnic culture. The diversity of values exhibited by shophouses has led it to be officially conserved. Their value is seen by awider rangeof people in theprocess of heritagization. Therearefour main values: architectural, aesthetic, cultural, andeconomicvalue.

The architectural value is reflected in shophouses’ structural integrity and their wise use of traditional techniques such as the expression of the architectural language of the vernacular architecture that copes with the tropicalclimate.Tobespecific,shophousesarevaluablebecausetheyfitthe needs of people living in a tropical climate and thus are truly local architecture.Inthisregard,shophousesofferuniqueknowledgeforthestudy

of architecture. In terms of aesthetic value, it is also demonstrated in the constant evolution of their physical or intrinsic properties such as their inherent aesthetic qualities and their history. As mentioned earlier, the aestheticvalueisshowninthevibrantcoloursanddelicatefacadesofthese shophouses from the city streets. The aesthetic features distinguish Singaporefromothercitiesandelicitpeople’spleasureinthecontextofthe rapiddevelopmentofahigh-risecityscape.Theculturalvalueisreflectedin thefactthattheculturalpotentialofshophouses,asarichlyevolvedtypology, allows them to reflect the memoryof thepast. In other words, shophouses reflect different ethnic identities whether they are modern or indigenous, colonial or post-colonial. They are the best expression of the diversity and integration of Singapore's multiculturalism, which tends to be neglected by many contemporary architectural works. Concerning economic values, shophouses have great tourism values. In a broader sense, the economic valuesofshophousesarenotonlyinthebuildingsthemselvesbutalsointheir roleasananchorforthecontinueddevelopmentofthecityduetoeconomic commercial trade-offs, cultural ethnic integration, or the reliance on the practicalityofexistingfunctions.Thesevariousaspectsofvaluesarewhythe authoritiesandinstitutionsformulateandimplementconservationplans.

5.2 The Necessity of Conserving Intangible Heritage

Intangible heritage should be adequately preserved. The importance of preservingthelifeofstreetsintheprocessofconservationisemphasizedby Victor Savic. Yeoh (1994)alsostates thatpeopleshouldstressthesoftware aspect of conservation, that is, theresidents, theusers, and other people in relationtobuildings.First,thecity'saestheticvaluecomesnotonlyfromthe architectureoftheoldbuildingsbutalsofromthecolors,smells,andsightsof the neighborhood. The shophouse residential, which presents the unique characterofthecity,isalsoalivelycommunity.Itshouldbepreservedfirstto maintain its historical and ethnic authenticity. Intangible heritage also consistsof thediversityof thepopulation such as themixof theyoung and old. According to the "Old-fashioned Community Figures and Yuppies, Fashion Models and 'Bag Ladies'" (Florida, 2002), all people should have equal rights as long as they are residents living in an area. Since the authenticity of the city also comes from the mix of high and low cultures, characters such as hawkers also add color and vitality to thestreets. These daily life situations are more spontaneous rather than planned by the authorities. Moreover, intangible heritage involves stores such as coffee shops and folk pharmacies that satisfy residents’ living needs. If only tourist stores are available in an area, it will lose its sense of place and culture. According to

Yeoh(1994),thebanonroadsideactivitiesandstallsrestrictssomeoftheir originaluses; businessessuchas carsales, repair stores, andmachineparts are also banned. This is because the government has developed a list of desirablenewusesfortheseblocksandthelistinvolvesprohibitedactivities. Butthefactisthatthevernacularappeals totourists andothermembersof the cultural industry. They are intrigued by the authentic flavor and atmosphere of these places. More importantly, they are the economic lifebloodoflocalcommunitiesandthesafeguardoflocalcrafttraditions.The preservation of tangibleheritagemeans thatthe authenticity and character ofthecitysuchassomelocalformsandfunctionsshouldberetained,andthat people’s urban experience entails authentic architecture, authentic people, and authentic history (Winter et al, 2008). In addition, it is important to ensurepeople'ssafetyandraisetheirawarenessofconservation.Inaddition to maintaining a beautiful storefront, other aspects of the conserved area need to be considered. For example, the government should consider the maintenanceofpedestrianpathsandbackalleys,whichhelpsthemperform theirfunctionsandissafeguardthesafetyoftheresidents.

5.3 The Future Prospect of Shophouses

In response to the third research question, the issue of adaptive reuse of shophousesandfurtherpossibilitiesareexplored.Inamodern,fast-growing

citysuchasSingapore,itsarchitecturetendstobecontemporaryandreflects a clean minimalist form and a material modernist aesthetic that is highly differentfromtraditionalvernaculararchitecture.Thenewandtheoldinthe city appear to be contradictory, but this does not mean that they are completelyunrelated.Inthefaceofsustainablebuildingdesigninthefuture, weshouldnotrelyonnewmaterialsandtechnologies,traditionaltechniques andconstructionwisdomneedtoberevisitedandarchitecturalconceptsthat have a close relationship with their users should be used. For example, the conservation and adaptive reuse of shophouses contribute to the cultural richnessofSingapore'sarchitecture.Additionally,peopleshouldrealizethat advances in technology should be considered to tackle the limitations of currentdesignratherthanseeknewidentitysymbols.

The search for appropriate architectural expressions between old and new buildings demonstrates the uniqueness and commonality of values, the dynamic interplay of local, regional and international components, forces and developments in various historical contexts (Bolzano and Trento, 2018).

Bibliography

Hardy,D.(1988).Historicalgeographyandheritagestudies. Area,333-338.

CollierP.,&HoefflerA.(2007).HandbookofDefenseEconomics:Chapter23 CivilWar.Elsevier.

Melic,K.(2019).Past,present,andfuture:conservingthenation’sbuilt heritage.CentreForLiveableCities.

Glendinning,M.(2013). The conservation movement: a history of architectural preservation: antiquity to modernity.Routledge.

ChenXi.(2019).“建筑遗产修复的演变及本土化研究 [Theevolutionand localizationofthetheoryofrestorationofarchitecturalheritage]”.In China

Academic Journal,17-23.

Jokilehto,J.(2017). A history of architectural conservation.Routledge.

Laitin,D.(2002).Cultureandnationalidentity:'TheEast'andEuropean integration. West European Politics, 25(2),55-80. Pendlebury,J.(2008). Conservation in the Age of Consensus.Routledge.

Fong,K.L.,Winter,T.,Rii,H.U.,Khanjanusthiti,P.,&Tandon,A.(2012).

‘Samesamebutdifferent?’:aroundtablediscussiononthephilosophies, methodologies,andpracticalitiesofconservingculturalheritageinAsia. In Routledge Handbook of Heritage in Asia (pp.52-67).Routledge.

LIMSW,W.(1993).Contemporaryculture+heritage=localism.

Lowenthal,D.1994.‘Identity,HeritageandHistory’,In Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity.Princeton:PrincetonUniversityPress,41–57.

Taylor,J.(2015).Embodimentunbound:Movingbeyonddivisionsinthe understandingandpracticeofheritageconservation. Studies in conservation, 60(1),65-77.

Akagawa,N.(2016).Rethinkingtheglobalheritagediscourse–overcoming ‘East’and‘West’?.InternationalJournalofHeritageStudies,22(1),14-25. Liang,Sicheng.(2007).“闲话文物建筑的重修与维护 [Discussingthe RestorationandMaintenanceofHeritageBuildings].”In 梁思成全集

(五)[Liang Sicheng Complete Works, Volume 5],editedbyZuoChuan,440447.Beijing,ChinaConstructionIndustryPress.

Stokes-Rees,E.(2008,July).‘Weneedsomethingofourown’:Representing Ethnicity;Diversityand‘NationalHeritage’inSingapore.In National museums in a global world. NaMu III; Department of culture studies and oriental languages; University of Oslo; Norway; 19-21 November 2007 (No. 031,pp.21-37).LinköpingUniversityElectronicPress.

Smith,R.A.(1988). The Role of Tourism in Urban Conservation:TheCaseof Singapore.Cities,5(3),245-259.

Treiber,D.(2005). Norman Foster.Taylor&Francis.

Rudofsky,B.(1987). Architecture without architects: a short introduction to non-pedigreed architecture.UNMPress.

Aboulnaga,M.,&Mostafa,M.(2019).SustainabilityPrinciplesandFeatures

LearnedfromVernacularArchitecture:GuidelinesforFutureDevelopments

GloballyandinEgypt. Sustainable Vernacular Architecture,293-356.

Simões,R.N.,Cabral,I.,Barros,F.C.,Carlos,G.,Correia,M.,Marques,B.,& Guedes,M.C.(2019).VernaculararchitectureinPortugal:Regional variations.In Sustainable Vernacular Architecture (pp.55-91).Springer, Cham.

Yuen,B.(2006).ReclaimingCulturalHeritageinSingapore.UrbanAffairs Review,41,830–856.

Wolters,O.W.(1999). History, culture, and region in Southeast Asian perspectives (No.26).SEAPPublications.

SereneTng,Tan,I.,Eveland,J.,&Zhuang,J.(2020). 30 years of conservation in Singapore since 1989 : 30 personal reflections and stories.Urban RedevelopmentAuthority.

Davison,J.,&LucaInvernizzi.(2010). Singapore shophouse.Talisman.

Cohen,L.,Manion,L.,&Morrison,K.(2002). Research methods in education Routledge.

Gray,D.E.(2004). Doing research in the real world.Sage.

Robson,C.,&McCartan,K.(2016). Real world research: A resource for users of social research methods in applied settings.Wiley.

TianYuan.(2018). 新加坡马来西亚华侨建筑研究现状初探 [Apreliminary studyonthepresentsituationofoverseasChinesearchitectureinMalaysia, Singapore].Doctoraldissertation,HuaqiaoUniversity.

Sayigh,A.(Ed.).(2019). Sustainable vernacular architecture: how the past can enrich the future.Springer.

LeHtun,W.(2010).Aginggracefully:effectsoftime,growthandchangein architecture.ScholarBank@NUS.

Chang,T.C.,&Teo,P.(2009).Theshophousehotel:Vernacularheritageina creativecity. Urban Studies, 46(2),341-367.

Khublall,N.,&Yuen,B.(1991). Development Control and Planning Law: Singapore.LongmanSingapore.

Yeoh,B.andHuang,S.(1996).TheConservation-redevelopmentDilemmain Singapore:TheCaseoftheKampongGlamHistoricDistrict. Cities,13(6), 411-422.

Lee,S.L.(1996).UrbanConservationPolicyandthePreservationof HistoricalandCulturalHeritage:TheCaseofSingapore. Cities,13(6),399409.

Kong,L.andYeoh,B.S.(1994).UrbanConservationinSingapore:ASurvey ofStatePoliciesandPopularAttitudes. Urban Studies,31(2),247-265.

Lichfield,N.,Barbanente,A.,Borri,D.,Khakee,A.,&Prat,A.(Eds.). (1998). Evaluation in planning: facing the challenge of complexity (Vol.47). SpringerScience&BusinessMedia.

UrbanRedevelopmentAuthority.(1985). Annual Reports.Singapore:URA

Jacobs,J.(1993).TheDeathandLifeofGreatAmericanCities(Modern LibraryEditionedn.

Akagawa,N.(2016).Rethinkingtheglobalheritagediscourse–overcoming ‘East’and‘West’?. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 22(1),14-25. UrbanRedevelopmentAuthority.(n.d.). Best Practices. Retrievedfrom https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Guidelines/Conservation/BestPractices

UrbanRedevelopmentAuthority.(n.d.). The Shophouse. Retrievedfrom https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Get-Involved/Conserve-BuiltHeritage/Explore-Our-Built-Heritage/The-Shophouse

Santagata,W.(2002).Culturaldistricts,propertyrightsandsustainable economicgrowth. International journal of urban and regional research, 26(1),9-23.

Beckers,B.,&Garcia-Nevado,E.(2019).Urbanplanningenrichedbyits representations,fromperspectivetothermography.In Sustainable Vernacular Architecture (pp.165-180).Springer,Cham.

Abusafieh,S.(2019).FromGeniusLocitoSustainability:Conciliating

BetweentheSpiritofPlaceandtheSpiritofTime ACaseStudyontheOld CityofAl-Salt.In Sustainable Vernacular Architecture (pp.141-163). Springer,Cham.

Wright,G.(2003)OnmodernvernacularsandJ.B.Jackson,in:C.Wilsonand P.Groth(Eds) Everyday America: Cultural Landscape Studies after J. B. Jackson,pp.163–177.Berkeley,CA:UniversityofCaliforniaPress.

Chang,T.C.(2016).‘Newusesneedoldbuildings’:Gentrificationaesthetics andtheartsinSingapore. Urban studies, 53(3),524-539.

Youngs,T.(2006)WanChai:urbanrenewalandcommunityaction, Heritage Asia,3,pp.20–26.

Vellinga,M.(2006).Engagingthefuture:Vernaculararchitecturestudiesin thetwenty-firstcentury.In Vernacular Architecture in the 21st Century (pp. 99-112).Taylor&Francis.

Logan,W.S.(2002). The disappearing'Asian'city: protecting Asia's urban heritage in a globalizing world.OxfordUniversityPress.

Peck,J.(2005).Strugglingwiththecreativeclass. International journal of urban and regional research, 29(4),740-770.

Mei,S.Z.(2009).Conceptsofdetails:theexpressionoffaçadedetailin Singapore.ScholarBank@NUS.

Li,T.L.(2007).Astudyofethnicinfluenceonthefacadesofcolonial shophousesinSingapore:acasestudyofTelokAyerinChinatown. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 6(1),41-48.

WOHA.(n.d.). Tan Quee Lan Suites. Retrievedfrom https://woha.net/project/tan-quee-lan-suites/

Hong,L.J.(2013).Influenceofauthorityandagencyonshophousesin Singaporethrough‘Heritageisation’.ScholarBank@NUS.

Florida,R.(2003).Citiesandthecreativeclass. City & community, 2(1),3-19.

Winter,T.,Teo,P.,&Chang,T.C.(Eds.).(2008). Asia on tour: Exploring the rise of Asian tourism.Routledge.

Image source

[Fig1]OldphotographsshowingtheearlyshophousesinHokkienStreetin the1890s:https://www.nhb.gov.sg/nationalmuseum//media/nms2017/documents/school-programmes/teachers-hi-resourceunit-2-colonial-singapore.ashx?la=en

[Fig2]Keyelementofatypicalshophouses:https://www.ura.gov.sg//media/Corporate/Get-Involved/Conserve-BuiltHeritage/conservation08.png

[Fig3]Conservationplansforthreehistoricdistrictslaunchedin1998: https://www.ura.gov.sg/uol/Corporate/Resources/Ideas-andTrends/Making-the-Case

[Fig4]ThischarmingJooChaitRoadisrichwithPeranakancultureand architecturalheritage:https://www.timeout.com/singapore/things-todo/the-ultimate-guide-to-joo-chiat-katong

[Fig5]V-profileterracottarooftiles:https://www.ura.gov.sg//media/Corporate/Guidelines/Conservation/Best-Practices/Volume-2Roofs.pdf

[Fig6]"Marseille"tiles:https://www.ura.gov.sg/-

/media/Corporate/Guidelines/Conservation/Best-Practices/Volume-2Roofs.pdf

[Fig7]Layingnewtilesonmetaldeck:https://www.ura.gov.sg/-

/media/Corporate/Guidelines/Conservation/Best-Practices/Volume-2Roofs.pdf

[Fig8]Layingnewtilesonmetaldeck:https://www.ura.gov.sg/-

/media/Corporate/Guidelines/Conservation/Best-Practices/Volume-2Roofs.pdf

[Fig9]Walldamagedbyplantgrowth:ByAuthor

[Fig10]Babahouse'sspiralstaircase:https://wisata.app/enus/diary/instagramable-stairs-on-bugis-street

[Fig11]Diagramoftheeffectofmoistureonwalls:ByAuthor

[Fig12]Diagramoftheeffectofmoistureonwalls:ByAuthor