Full Plagiarism Report

By Izzah Sarah Binte Omer Ali Saifudeen (A0289543N)

For NUS MAArC Program AC5007 Semester 2 AY 2024/2025

Supervised By: Dr Johannes Widodo

ExploringtheMaritimeHeritageofSingapore:B...

By:IzzahSarahBinteOmerAliSaifudeen

Asof:Nov10,202411:31:36PM

10,857words-65matches-36sources

sources:

131words/1%-Internetfrom20-Aug-202212:00AM www.clc.gov.sg

27words/<1%match-from19-Jul-202412:00AM www.clc.gov.sg

44words/<1%match-from06-Sep-202412:00AM www.straitstimes.com

26words/<1%match-from02-Nov-202312:00AM www.straitstimes.com

57words/<1%match-Internetfrom15-Nov-202112:00AM uni-tuebingen.de

53words/<1%match-from26-May-202412:00AM biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg

41words/<1%match-from12-Jul-202412:00AM WWW.coursehero.com

8words/<1%match-from05-Nov-202412:00AM www.coursehero.com

41words/<1%match-from03-Nov-202412:00AM www.languagecouncils.sg

35words/<1%match-Internetfrom15-Mar-202212:00AM open-education-repository.ucl.ac.uk

17words/<1%match-Internetfrom08-Dec-202012:00AM ir.unimas.my

14words/<1%match-Internet SitiNoorhidayu,BintiIbrahim."PreliminarystudyofMorphologicalandGeneticDiversityonAsianGreenMussel (Pernaviridis)inSantubong,Sarawak",UniversitiMalaysiaSarawak,(UNIMAS),2014

30words/<1%match-from30-Jul-202412:00AM www.dyslexia.com

24words/<1%match-from26-Jun-202412:00AM ijsshr.in

23words/<1%match-Internetfrom14-Mar-202112:00AM www.researchcatalogue.net

21words/<1%match-from06-Aug-202412:00AM doczz.net

12words/<1%match-from27-Jul-202412:00AM wikimili.com

9words/<1%match-from19-Dec-202312:00AM wikimili.com

20words/<1%match-Crossref MelissaLiowLiSa,SamChoon-Yin."SustainableUrbanDevelopmentinSingapore",SpringerScienceandBusiness MediaLLC,2023

20words/<1%match-Internetfrom09-May-202012:00AM www.nlb.gov.sg

18words/<1%match-YourIndexedDocuments Dessertation_Final_LongSiyu-0422.docx

From:22-Apr-202412:43PM

18words/<1%match-from20-Sep-202412:00AM clovedental.in

18words/<1%match-Internetfrom19-Nov-202012:00AM

in.pinterest.com

17words/<1%match-from10-Sep-202412:00AM www.mdpi.com

15words/<1%match-from09-Sep-202412:00AM repository.uantwerpen.be

14words/<1%match-ProQuest Schuller,Ethan."FacingForward,LookingBack:TransmissionofChineseCultureinSingaporeThroughMusic", WesternIllinoisUniversity,2024

13words/<1%match-Crossref AngeliaPoon."Chapter6TappingintoWeird:ContemporarySingaporeShortFictionbyAmandaLeeKoeandNgYiSheng",SpringerScienceandBusinessMediaLLC,2024

12words/<1%match-Internetfrom19-Jan-202312:00AM popgeogresearch.files.wordpress.com

12words/<1%match-from04-Nov-202412:00AM www.scape.sg

11words/<1%match-Internetfrom19-Oct-202012:00AM rgs-ibg.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

10words/<1%match-from19-May-202412:00AM docslib.org

10words/<1%match-from23-Dec-202312:00AM tnp.straitstimes.com

9words/<1%match-Internet lrd.yahooapis.com

8words/<1%match-from11-Jul-202412:00AM amt-lab.org

8words/<1%match-Internetfrom15-Jan-202312:00AM dspace.unive.it

7words/<1%match-Crossref

HenryJohnson."Islandsofdesign:Reshapingland,seaandspace",Area,2018

papertext:

ExploringtheMaritimeHeritageofSingapore:BridgingHeritageandModernisationByIzzahSarahBinteOmerAli SaifudeenA0289543NForNUSMAArCProgramAC5007Semester2AY2024/2025SupervisedBy:DrJohannes WidodoAbstractSingaporeowesmuchofitsprosperitytoitsmaritimeroots,havinggrownfromahumblefishing villageintotheentrepotitistoday.However,Singapore’sconservationeffortshavepredominantlyfocusedononlythe urbanheritage,leavinghistoricaljetties,piers,harbours,andothermaritimeheritageareasatriskofneglector redevelopment.Thisthesisthusexaminesthesemaritimeheritagespaces’historical,cultural,andcommunalsignificance. Theresearchaimstodrawattentiontothevalueofthesespacesandadvocateformoreinclusiveconservationeffortsthat recognisetheirimportance.Theresearchhighlightsgapsinpolicyandpublicengagementwithmaritimeheritagethrough ethnographicanalysis.ThecasestudieschosenincludeCliffordPier,SembawangJetty,KeppelHarbour,andKelongs. TheresultsshowthatwhilemostSingaporeansrecognisethenation’sislandstatus,theirunderstandingcentresaroundthe urbandevelopmentofSingaporeratherthanitsmaritimelegacy.Asaresult,theproposalintroduceseducationaltoolslike digitalexhibitsandphysicalfocalpointsdesignedtofosterpublicengagementandbalancedevelopmentwith conservation.Literaturereviewsfurthersupplementinvestigations.Mostreviewedworksaresecondarysources,suchas analysesof‘islandness’,conservationpolicies,andmapsofSingapore’shistoricalmaritimeroutes.Unfortunately,the dominanceofEurocentricprinciplesinthereviewedworksoftenoverlooksSingapore’suniquemulticulturalheritage. Moreover,Singapore’sneedformodernisationheavilyinfluencesthespacesprioritisedunderthenation’sconservation policies.Thus,maritimeheritageareasareoftenexcludedinexistingscholarshipandpolicyframeworks.Assuch, primarysourcesareneeded.Byemployingamixedmethodologythatincludesinterviews,siteobservations,andsurveys, thisstudyultimatelyproposesasustainablemaritimeheritageconservationframework.Thisframeworkensuresthese spacesremainsignificantinSingapore’snationalidentityevenasSingaporeevolves.TableofContentsIntroduction BackgroundObjectivesPlaceTimeOverviewofWorksHypothesesSummaryofMethodologyQuantitativeQualitative LiteratureReviewI.TextsaboutIslandnessandContextinSingaporeIslandsofDesignUrbanHeritageinSingapore UtilitarianHeritageII.PoliciesaboutConservationinSingaporePreservationofMonumentsActSixCriteriafor ConservationHeritageBandingFrameworkHistoricalValueAesthetic/ArchitecturalValueCommunal/SocialValue Group/SettingValueIII.MapsGeographicalContextSingaporegrowingHazardsUrbanandConservationPlanning OverallAnalysisMainCausesMethodologyEthnographicFrameworksSpradley’s9dimensionsAEIOUFramework POSTASotirinFrameworkResearchQuestionsInterviewsandSiteVisitsCasualInterviews7

14 14141517191921222223232425252628303637383838434445464848SiteObservationsSurveysResults InterviewResultsSiteObservationResultsSurveyResultsDiscussionMaritimeHeritageastheNationalIdentityNew FrameworkComponentsConclusion50525353545656565758609997wordsIntroductionBackgroundMeowblub-a-bulb.Thatisadesperatematingcryfromacatfish.Canyouguesswhatisconsideredacatfish?TheMerlion,

Singapore’smostfamoushybridiconthatsymbolisestheisland’sfishingrootsandloftyambitions.In1964,thedesign fortheMerlioncamebymergingtwothemes:thelionheadtorepresentSingapura,akathelioncity,andthefishbodyto representthehumbleoriginsofthelittlereddotasafishingvillagecalledTemasek.Temasekwastheprecursorto Singapore’ssuccessasanentrepôt,boastingarichseafaringcultureandastrategiclocation.[1]Yet,Singaporeonly presentsitselfasanultra-modernmetropolis,quietlysidesteppingitsdeeperidentityasanislandnation.Afterall,how elsecanSingaporebagglobalsuperpowersandpowerhouses?AlthoughSingapore’sglobalstandingisprimarilydefined byland-basedarchitectureandtechnology,itshistoricalconnectiontothesearunsfardeeper.Sadly,thisisanoverlooked connectioninfavourofimprovingthecountry’sfacades.However,whatifthenaturalidentitycouldbethenational identity?ObjectivesNationalidentity,oftendefinedasasharedsenseofbelonginganduniqueculturalunderstanding amongstcitizens,isarecurringthemeinthisdissertation.Naturalidentityissupposedtobepartofthisnationalidentity, asnaturalidentitywillencompassuniqueenvironmentalcharacteristicsthathavehistoricallydefinedanation’swayof life.Uponlookingathowthenationalidentityhasevolved,thecoreproblemwiththenaturalidentitybecomes increasinglyapparent.ThereisaweakenedconnectionbetweenSingaporeasanationanditsnaturalmaritime7heritage, withtheonlylinktoasharedpastfueledbynostalgiaduetotherelentlesspursuitofacity-centricidentity.Suchageneric focushasresultedinculturalerosion.Crucialsitesincludejetties,piers,kelongs,andharbours.Literatureonthe conservationeffortsinSingaporeforgeneralbuildingssuggeststhisdisconnectionisnotuniquebutispartofbroader regionalandglobaltrendsfocusingonstructuresthateithershowamoreglamorousnationalityorpromoteefficiencyon landonly.Nowimagineifthisissueisnotresolvedbasedonanalysingzoningandurbantypologieswithinthecountry.In thatcase,futuregenerationswillbecomeevenmoredetached,andSingapore’shistoricalsignificanceasanislandnation willfadeintoagenericcity-stateidentity.Thus,thisresearchdivesintothemaritimeundercurrentsbeneathSingapore’s urbansheenthroughtwoprimarylenses:placeandtime.PlaceForplace-framing,specificarchitecturalfeaturesrelatedto maritimecultureareused.Thisincludesharboursandjetties’traderoutes,markets,ships,andwaterfrontactivities. Specificcasestudies,suchasthekelongs,CliffordPier,andSembawangJetty,willbehighlightedtoshowthebroader maritimelandscape.TimeSecondly,thetimeframegivenisbasedonthelayeringofhistoricalmapsthatillustrate Singapore’slong-standingroleasacriticalglobalport.Crucialmomentsexaminedwillbereputationadvancements, wars,andshiftsinlanduse.AlthoughtheresearchisrelevantforallSingaporeans,particularattentioninthisresearch timelineisgiventotheyoungergenerationsasgroupsarguablythemostdisconnectedfromthecountry’smaritime heritage.Suchlossentailstheir8diminishedconnectiontotheseabeingreplacedwithfasterandmoreaccessiblelandbasedmodesoftransport,areductioninhistoricalknowledge,andashiftinSingapore’sidentityfromanislandnationto acity-state.Theroleofmaritimeheritageas“anchorsofmemory”remainsvital,allowingtangiblesiteslikethese harboursandjettiestosupportcyclesofreinterpretationacrossgenerations.Thisthesiscanthenaddressfundamental researchquestionsonpolicy,engagement,andconservationchallengespresentedlaterinthemethodology.Overviewof WorksInordertofullydigestthesedynamics,acomprehensivereviewofrelevantmapsisneededtounderstandthe historicallayers,includingthelayoutofSingaporeandhowmaritimefeatureshavetransformedthroughoutthedecades, withparticularattentiontoshiftsinlanduse,tradepatterns,andarchitecturaltransformationssincethe1500s.Policy documentsareadditionaltoolstogatherinsightsontheperceivedvalueandrelevanceofmaritimeheritageinSingapore, thusassessingtheextentofculturalerosionandidentifyingpotentialavenuesforconservationwithinthelocalcontext. AsnotedbyBrendaYeoh,LilyKongandLukYingXian,Singapore’sheritageconservationfieldfollowsaWesterncentrictrendthatoverlookslocalhistoricalcontextsandprioritisesurbanstructuresoverlessglamorousmaritimespaces. Lastly,itiscrucialtoestablishacleardefinitionofwhatconstitutesanisland.Shouldtheperceivedimportanceofthese maritimesitesgrowovertime,theselocationsmayevenbecomecentraltoshapingSingapore’snationalidentity, reconnectingfuturegenerationswiththeisland’smaritimepast.HypothesesWithafocusonconservation,therearethen severalassumptionstoguidethisresearch,namelyrelatedtothedemographicandarchitecturalfeaturesatrisk.Young Singaporeansarethemostcrucialgroupfortheconservationofmaritimeheritage.Asfuturecustodians,their understandingandengagementwithmaritimeculturewilldirectlyinfluencehowitispassedtofuturegenerations. Moreover,GenerationZ(GenZ)inparticularisconsideredthemostdigitallyliteratedemographic.Theyarethefirst socialgenerationtohavegrownupwithaccesstotheInternetfromayoungage.However,achievingabetter understandingofsuchanintangibleconceptishardbeyondthetextbooks.Whilepersonalanecdotesfromparentsor grandparentscontributetomaritimeknowledge,theymaynotbesufficienttosustainlastingengagementamongst youngergenerations.ModerndevelopmentsanddigitallifestyleshavedistancedtheseSingaporeansfromreal-life maritimesitessuchasLimChuKangJetty,wherebyyoungerpeoplefavourfictionalcounterpartslikeLiyueHarbour fromGenshinImpact.Additionally,economicdevelopmentandshiftsinlandusehaveledtotheerosionofmaritime featuressuchasjetties,kelongs,andpiers.Thisstudypositsthat,withoutintervention,thesemaritimefeatureswill remainundervalued.ThisundervaluationwillfurtherweakenSingapore’smaritimeheritage.ForSingapore,the conservationofmaritimeheritageservesnotonlytoconservehistoricalnarrativesbutalsotoengageanincreasingly vocalbutdisconnectedgeneration,therebyaddressingthepotentialforcommunicationofthebroadernational significanceofmaritimeheritagetothiscurrentgenerationofSingaporeansandbeyond.10SummaryofMethodology Figure1:TheIshikawaDiagram(ByAuthor)ThefishpartoftheMerlion,representingmaritimeorigins,offersalens thatorganisesthelayeredcomplexitiesofmaritimeheritageerosion.TheIshikawaorfishbonediagram(seeninFigure1) dissectsthecausesbehindthedeclineinconservationforthemaritimeheritagescene.Assuch,thethesisflowwillbe followingthisstructure.First,thisintroductionisplacedatthefish’sheadandhasalreadyhelpedtoidentifythemain issue.IfSingapore’smaritimeheritageareasaresocentraltoitsdevelopmentasamaritimehub,whyhastherebeena declineintheconservationofthesesites,particularlyconcerningengagementbySingaporeans?Fromthere,each‘bone’ ofthediagramleadstoadetailedanalysis.Assuch,theresearchmethodologyadoptsbothqualitativeandquantitative

approachestothesecausesandeffectsoutlinedinthefishbonediagram.QuantitativeQuantitativeanalysis,including historicaldataandexaminingconservationpolicydocuments,identifyeconomictrendsandderivegaps.TheMainCause sectionwillinvestigatetheoverarchingcausesfoundfromtheLiteratureReview.Thisincludestheshifttoland-based development,policygaps,andgenerationaland/orculturaldisengagement.Followingthis,severalprimarygapscanbe pinpointed.GapsinthiscaserefertothespacesofresearchleftunaddressedbytheconservationeffortsinSingapore, suchasthelackofattentiontoeducatingthecitizensaboutmaritimeheritage.Thesegapsthenhighlightthechanging significanceofmaritimefeaturesconcerningevolvingbusinessmodels,policies,andsocietalroles.Bysystematically breakingdowntheproblem,Singaporecangobeyonditsmissingrootswithmaritimeheritageerosionandpropose meaningfulinterventions.QualitativeFromthemorequantitativemethods,keyresearchquestionscanbeformulatedand askedinthequalitativetasksthatwilldeepentheunderstandingofsocialvisionsandgenerationalimpacts.Therefore, thisthesisstudiesthehistoricalsignificanceofSingapore’smaritimeheritagespaceslikejetties,harbours,piersand kelongsascasestudies.Thisworkwilldemonstratehowtheconservationofmaritimeheritageisincreasinglyvitalto understandingnationalidentity.Whilecurrentconservationeffortsprimarilyfocusonbuildingsandurbandevelopment,a morecomprehensiveandinclusivestrategythatemphasisestheconnectionbetweenSingaporeansandmaritimehistoryis essentialforfosteringanauthenticappreciationofSingapore’srootsasanislandnation.Thisthesisthuswillhelp conserveSingapore’smaritimeheritagebeyondactsofnostalgiaandrathermoreascriticalstrategiesforreclaimingthe island’snationalidentity.LiteratureReviewTheliteraturereviewismadeupoftypesofreadingsratherthanthematic categories,aseachtypeoffersdistinctyetinterconnectedperspectivesrelevanttothethesis;(I)TextsaboutIslandness andContextinSingapore,(II)PoliciesaboutconservationinSingaporeand(III)MapsofSingapore’smaritimehistory.I. TextsaboutIslandnessandContextinSingaporeIslandsofDesignIslandsaremultidimensionalspacesbuttheirsizemay notbeenoughtoaccommodateresourcesandfosterdevelopmentsunlesstheyexpandtheirurbanareasbeyondhorizontal expansions[2].In‘

Islandsofdesign:Reshapingland,seaandspace’(HenryJohnson,2018),theauthor forarguesthatthereshapingofislandscanreflecthumanity'sinfluenceongeographyandculturalboundaries,whichalso underscoreshowhumaninterventioncaneithertransformislandsintodynamicspacesorasstaticresources.Thedatais qualitativelyanalysedthroughacriticalcomparativeframework,focusingonanthropogenicchangestoislandlandscape, includinginward,upwardanddownwarddynamics.Thisinvolvesexaminingarangeoftransformationssuchasland reclamation,urbanexpansion,physicaldivisionofislands,andenvironmentallevelling.Theanalysisincludesacritical reviewofrelevantcasestudies,includingManhattanIsland,HongKongInternationalAirport,andvolcanicislandsin Japan,tounderstand theshiftingphysicalityofislandspaceand itsimplicationofislandness.Manhattaninparticularhasexpandedvialandreclamation,anditsurbanlandscapehas grownverticallyduetopopulationdensityandlimitedlandarea.Moreover,thereareextensivebridgesandcanals.Thus, humanactivityhastransformeditsoriginal14islandgeographybutinawaytostillseethemaritimeareas.The explorationofurbanislanddynamicsprovidesacruciallensforunderstandingtheshiftingfocusofislandspaceinthe research.ThisperspectiveenablesthisstudytoproposenewfocalpointsforconservingSingapore'smaritimeculture, emphasisingtheneedtoreframeconservationeffortsinlightofhowanthropogenicchangesarereshapingbothlandand seadynamics.However,whilethetextdiscussesvariousdimensionsofislandreshaping,itprimarilyaddressesthese changesinurbanisation,landreclamation,andenvironmentalimpacts.Thisthesishowevercentresontheculturalerosion ofmaritimeheritageduetheshitsinland-baseddevelopmentinSingapore.Suchagaphighlightstheneedforresearch thatconnectsthesereshapingdynamicsdirectlytotheculturalandhistoricalimpactsonmaritimeheritage,ratherthan focusingsolelyonphysicalandeconomicaspectsofislandtransformations.UrbanHeritageinSingaporePoliciesto people.Policiestoplaces.PoliciestoponderonasseeninLilyKong’sexplorationin‘ ConservingthePast,CreatingtheFuture:UrbanHeritageinSingapore’.Inparticular,Singapore ’spoliciesareaimedtoconservethehistoricallyrelevantstructuresbyadaptingthemforcontemporaryuse,which enhancesthecity’sappealasaglobalhubfortourismandinvestment.Thisapproachbalancesconservationwhile ensuringthecityremainscompetitiveintheglobaleconomy.[3]Thecentralargumentshepresentsishowconservation wouldmaintainthecity’sidentityviaconservinglandmarksthatreflectSingapore’smulticulturalheritageandhistory Thereadingpositionsconservationasacollaborativeeffortinvolvingbothpublicandprivatesectors,withstrong governmentleadershipdrivingthisbalance.Byretainingiconicstructuresandspaces,Singaporestrengthensasenseof continuityandplacewhichnotonlyreinforcesitsnationalidentityasacity,butalsoenhancesthecity’sattractivenesson theglobalstage.Asaresult,Singaporehassuccessfullyconservedmorethan7000buildings,blendingconservation effortswithlarge-scaleredevelopmentprojects.Theworkshowsthesesuccessesbyelaboratingontheseveralphasesof Singapore’sconservationjourney.Thewholeprocessstartedin1954,whereconservationplansweresupposedtobepart ofadraftoftheMasterPlanofficialisedin1958.However,theseplanswereside-linedwhenPAP(People’sActions Party)wontheelectionin1959.PAPwaspro-redevelopmentandintensifieditsstanceasSingaporebecameindependent. Itwasonlyin1963thatconservationwasmentionedaspartofurbanplanningdiscussionsinSingaporewithaUnited Nationsreport.Thismarksthefirstrecordedconsiderationofheritagepreservationyetagainplanswerederaileduntilthe establishmentof thePreservationofMonumentsBoard(PMB)in1971throughanActof Parliament.Thisboardwouldofficiallybegineffortstopreservehistoricallyandarchitecturallysignificantbuildings. Thisincludedtherehabilitationof30state-ownedshophousesonMurrayStreetandTudorCourt.Fromthe1980s onwardsthoughwastheriseofUrbanRedevelopmentAuthority(URA)thatwouldreviewthecitycentreand recommendtheconservationof7key

historicdistricts;BoatQuay,Cairnhill,Chinatown,ClarkeQuay,EmeraldHill,LittleIndiaandKampongGlam .Moreevidenceincludestheirprojectsliketherestorationofshophouses,publicconsultations,privatesector engagement,andtheURAconservationmasterplanfinallyresultedinagreatformofrecognition. TheUrbanLandInstituteGlobalAwardsforExcellencein2006recognisedthe UrbanRedevelopmentAuthority’s16(URA)achievementsinurbanplanning,highlightingtheimpactofagovernment agencyreceivingstaterecognitionforitsefforts.[4]Andthisistheproblemwiththecurrentstrategies.Conservationis onlyaconcernifitistheconservationofatangibleshowofagovernment’ssuccess.Thisskewedfocushasneglectedthe lessvisibleformsofheritageinmaritimestructuresdespitehowtheyhaveshapedthenationalidentity.Kong’searlier workalongwithBrendaYeohexemplifythisissuein UrbanConservationinSingapore:ASurveyofStatePoliciesandPopularAttitudes (1994).Theyhighlighttheresultsofasurveywhere33.7%ofrespondentsarguedlifestylesandactivitiesshouldremain centraltoconservationefforts.Yet,theURAsimplyoptedtoretainthetraditionalactivitiesandintroducenewactivities withoutpropermergerofthetwo.Whileconservationpoliciesmayaimtosatisfyconservationexpertsandmodern developers,theyoftenfailtofullyaddresstheneedsofanygroupandonlythegovernment’sgoals.Thethesisthusneeds tocounterthisgapbyemphasisingtheneedforamoreinclusivestrategythatrecognisesandconservesallaspectsof Singapore’smaritimeheritage,ratherthanlimitingconservationtotheprominentinlandlandmarks.UtilitarianHeritage SomemightblamethiskindofgovernanceduetotheveryforceSingaporeworkedsohardtobreakfreefrom:TheWest. [5]ThereisnodoubthowdominanttheWesternparadigmsareinthefieldofheritageconservation,withalotof emphasisonaestheticsandhistoricalageasprimarymarkersofculturalsignificance.ThisEurocentriclenscannot accountfortheuniquedynamicsfoundinSingapore.However,theseaspectsareoftenoverlookedinfavourofthemore prominentarchitecturalorurbanlandmarks.Inherwork,UtilitarianHeritage:ThePanopticonofNarrativesbehind IndustrialHeritageConservationinSingapore,LukYingXiandiscussesthisbiasformaterialityinrelationtoSingapore’s industrialconservationscene.Thisemphasisestheneedtorethinkwhatconstitutesculturalsignificancebeyondmere physicalattributes.InSingapore,industrialheritagehasbeenovershadowedbythefocusoncolonialandethnicheritage. QuitebizarreconsideringhowtheindustrialheritageofSingaporehasplayedsignificantrolesinformingthesecultures. Singapore’sindustriallandscape,characterisedbyfactories,shipyardsandwarehouses,isdominatedbyseveral communities.ThisisseeninseveralcasestudiessuchastheoneonJurongTownHall(JTH).Localresidents intermingledwithemployeesandworkersinsmallandmedium-sizedenterpriseshousedinJTH,especiallyduringits timeastheiHubandnowtheTradeAssociationHub(TAHub).However,withthegovernment’stop-downapproachin Singapore,JTHwasupgradedtobecomeanationalmonumentinlieuoftheSG50initiative.JTHwouldthenbe primarilyhighlightedasamilestoneundertheleadershipofSingapore’sfoundingfigures.Thisapproachmayrisk overshadowingthecontributionsandexperiencesofthelabourerswhowerepartofJTH’shistory.Insteadofsolely focusingonauthorisednationalnarratives,theremaybevalueingivingspacetothesesmallerstoriestoprovideamore inclusiveviewofSingapore’sheritage.Byincorporatingthevoicesofthesecommunities,amoreholisticviewof heritagecouldhavebeendevelopedtoresonatewithothersandshapeSingapore’suniqueidentity Thus,theauthorcalls uponembracingalternativeframeworksthatreflectlocalculturalsignificancearenecessaryratherthanmerelyfollowing orcopyingWesternmodelsthatfollowsuchanoutdatedhierarchy Thiscallforabroaderdefinitionofcultural significancebeyondphysicalattributesandtopauthorityfiguressupportsthis18thesis’argumentthatcurrent conservationeffortsoftenoverlooktheculturalnarrativesandsocialbondstiedtomaritimeheritage,therebyleadingto lessgenuineappreciationofSingapore’sroots.However,thisreadingdiscussesmostlymaterialityandculturalnarratives, lackingafocusonthechangestobothlandandseadynamicsinthearea.Therefore,thispaperaimstoconnectthese physicaltransformationstotheculturalandhistoricalimpactsonmaritimeheritagetoaddressthiscriticalgap.II.Policies aboutConservationinSingaporeConservinghistoricbuildingsisamultifacetedendeavourthatextendsbeyondmere conservingarchitecture.Whiletherehavebeenseveralkeybodiesintroducedwithinthetextsforislandnessandcontext inSingapore,themethodsemployedaretobeexaminedaswellsincenotonlyaretherestrategiesproposedtohelpwith conservation,butthefuturesoftheseeffortsarediscussedforbetterassessmentofchoosingsuchstrategies. PreservationofMonumentsActThePreservationofMonuments Actistiedtonationalidentity.[6]ThenationalauthorityisthePSM(PreservationofSitesandMonuments)underNHB. Theboard'smainfunctionsunderthisactincludeidentifyingmonumentsofhistorical,cultural,archaeological, architectural,artisticorsymbolicsignificance.SuchresponsibilitiesgainedimportanceduetoSingapore’srelianceon foreignexperts.Hence,localsmadewayformonumentsaround1973asseveralwereannounced. Eightculturallyrepresentativebuildingsweremarkedforconservation

Theseinclude;

1)CathedraloftheGoodShepherd192)ArmenianChurch3)St.Andrew’sCathedral4)HajjahFatimahMosque5)Telok AyerMarket6)ThongChaiMedicalInstitution7)ThianHockKengTemple8)SriMariammanTemple

However,uponcriticalexamination,onewouldnoticemostofthebuildingswerewell-establishedonesandrichwith fundssotherewasnorelianceongovernmentmoney.

CathedraloftheGoodShepherdforexampleistheoldestCatholicchurchinSingapore andwhilethereisnofixedcommunityforthebuilding,manycommunitymembersparticipateinvolunteerworkssuchas liturgicalandoutreachministriesandofcourse,donateextensivelyandthusprovidegoodfinancialsupportforthe Cathedral.Furthermore,thesemonumentsarealreadylinkedtothevariousfaithsinSingaporethatwouldreinforceour nationalidentityasasocially-stable,multiculturalcity Assuch,thisactoverlookssmaller,lessprominentsites,including themaritimeheritagespaces.Thus,thisthesiswillneedmoreinclusiveconservationpoliciesthatemphasisethe importanceofmaritimeheritagespaces.SixCriteriaforConservationFigure2:TheSixCriteriaforConservation[7]The

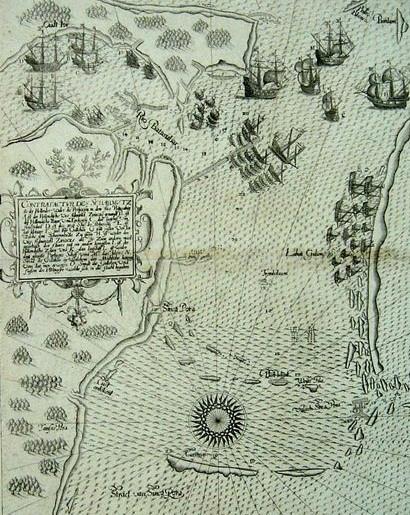

SixCriteriaforConservationbyURA(seeFigure2)isaframeworkthatassesseswhetherabuildingqualifiesfor conservation.Thisstructureismeantforconservinginthefirststagesofabuilding’srenewedlife.Furthermore,thevalue ofthebuildingsbeingcalledtoquestionextendsbeyondtheirarchitecturalvalue.Theseedificesoftenplaypivotalroles inecosystemsandserveasintegralcomponentsofthesocietalfabric,furtherunderliningtheimportanceoftheir conservation.Theframeworkthususesthefollowingcriteria;1)EconomicContribution2)ArchitecturalMerit3)Rarity 4)Contributiontotheenvironment5)Identity6)Cultural,social,religious,andhistoricalsignificanceThisalignswith thethesisbyseeingthedeeperconnectiontonationalidentity.Inthecaseofthemaritimeheritagespaces,thesespaces aretiedtonationalidentityjustlikethebuildingsassessedunderthisframework.Yet,thisframeworkhasnotbeenused onthesemaritimeheritageareasbecausetheyarenotbuildings.Thus,thethesisneedstoincorporatethesevaluesintoa newframework.HeritageBandingFrameworkTheHeritageBandingFrameworkbyNUS[8]providesapolicylensfor evaluatingheritagesitesbyassigningvaluetokeyaspects:historical,architectural/aesthetic,communal/social,and group/settingvalues.Thisguidecanshowhowsitesshouldbeconservedasthevaluesareexaminedbelow;Historical ValueHistoricalvalueisrelatedtohowthesiteisvitaltoanimportantevent,historicalfigure,phaseoractivity.Some relationsinclude;-RepresentativesbuiltworksofSingapore’surbantransformationandplanningmilestones,orof historical,political,cultural,economicphasesortrends–forexamplenationalbuildingprograms–thatformspartofthe relevantthematicnarratives.-Developmentwithreachandimplicationand/oraccolades/recognition.-Associationwith significantpersonalities/organisations/eventsofsignificance.Aesthetic/ArchitecturalValueTheaestheticand architecturalqualitiesgeneratedbythedesignofabuildingstructurearealsoexamined.Thestrengthofthevaluesis dependentassuchontheform,proportions,massing,vistas,materials,craftsmanshipandhowinnovativethedesignis. Theseincludethefollowing;-Representativeofadevelopment/planning/architecturaltypology,aesthetic,styleand/or trendthatformspartofthethematicnarratives.-Representativeofbuildingtechnology,materialityand/or craftsmanship/execution.-Representationalworkofsignificantbuilder,architect,planner,engineer,developerDevelopmenthasbeenconferredaccolades/recognition,especiallyforitsbuilding/architecturalachievements.-Variety andrangeofbuildingsintermsoffunction,typology,design,hierarchy,phases-Keybuiltstructures/architectural attributesremainintact/legible.Communal/SocialValueCommunalandsocialvaluesareabouttheassociationsthe buildinghaswithothersasasourceofidentity,distinctiveness,everydaylifeandcoherence.-Symbolicvalue,for exampleasarepositoryofcollectivememoryorasreferencepoint/markerofidentity,tothecommunity.-Testimonytoa particularwayoflife,cultureorpractice–abrick-and-mortar/spatialrepositoryofcustoms/socialrituals/habits/social organisationwithinaparticularhistoricmilieu.-Developmentthatisdesignedtopromotesocialcohesion,orthat engenderstructuredcommunities,orthatgenerallyfacilitatessocialconnection,networksandotherrelations.-Continued socialandcommunalrole,initscurrentuseinrelationtoitshistoricprogramme,and/orconnectiontothecommunity. Group/SettingValueFinally,groupandsettinghastobeconsideredintermsofhowabuildingand/orsitehasrelatable featurestotheirorganisationsandthegroupvalueofacluster,andinterrelationbetweensitefeatures/buildingstructures andtothewiderorextendedsetting/context/ecosystemsbeyondthecluster-Representativeshowcaseofsite organisation,groupvalueandinterrelationbetweenstructuresorsitefeatures(masterplan/urbandesign,site layout/configuration)thatarekeysiteattributesofthecluster/subcluster,andcontributestoitslegibility,appreciation,and heritagepresentation.-Thecluster’s/subcluster’sroleinandinterconnectionwithitsextendedsurroundingcontext (beyondthecluster/subclusterboundary)intermsofwiderurbansystems,strategicsiting,planning,developmenthistory. -Naturalenvironmentorurban/manmadesettingthatcontributestothecluster’s/sub-cluster’slegibility,historic function/operation,character,andconnectivitytoothernaturalecosystemsormanmadenetworks.-Historicgroupand settingattributesremainintact/legible.Thisproposedframeworkarguesthatheritageconservationmustmovebeyondthe physicalformofthebuilding.Withaholisticapproach,heritagesitescanstillretaintheirrelevanceandmeaningwithin theevolvingurbanlandscape.Assuch,thisframeworksupportsthisthesisbyshowingthatconservingmaritimeheritage requiresmorethanarchitecturalconservation.Thesocialandcommunalrolesofthemaritimeheritageareasaswellas theirhistoricalconnectionstoSingaporearevitaltounderstandingtheirintangiblevalue.However,connectionsitselfis anissuehere.Specifically,connectionswiththeyoungergenerationofSingaporeans.Thereistheassumptionthat communityinvolvementissufficientforsustainingheritage,ignoringtheneedfortargetedoutreachtoconnectyounger generationsmeaningfullywiththesesites.Therefore,thethesiswouldneedtoproposeamoreinteractiveapproachto maritimeheritageconservation,leveragingcurrenttechnologytomakehistoricalsitesandnarrativesaccessibleand engagingforyoungpeople.III.MapsHistoricalcartographyprovidescriticalinsightsintoSingapore’maritimeheritage, revealingitsstrategicimportanceinglobaltradeandSoutheastAsianmaritimenetworks.Theanalysisofcartographic sourceswillrevealSingapore’sstrategicsignificanceandevolutionofitsroleinglobaltrade.Mainmapsincludethe mapsof1502,1513,1548,1570,1599-1628,1604,1650,1822,1964,1989,and2020.GeographicalContextTheMalay PeninsulaisalargepeninsulainSoutheastAsiathatextendssouthwardfromtheAsianMainland.Itseparatesthe AndamanSea tothewestfromtheSouthChinaSeatotheeastandis borderedbyThailandtothenorthandSingaporetothesouth.SingaporespecificallysitsjustoffthecoastoftheMalay Peninsula,separatedbyJohorStraitandalongtheStrait ofMalacca,whichisoneofthe25busiestshippinglanesintheworld.[9]This positionmakesSingaporeacriticaltransitpointforglobaltrade betweentheIndianOceanandtheSouthChinaSea.Singapore growingHowever,suchsignificancewasnotimmediatelytransparenttoPortugueseandotherEuropeancartographers documentingtheirexplorationsinAsia.[10]CantinoChartfrom1502InthePortugueseseachartof1502,thereisno explicitmentionof‘Cingaporla’or‘Cingatola’whichweretheearliesttranscriptionsofSingapura.1513Mapfrom

MartinWaldseemullerInfact,theMalayPeninsulaitselfwasonlylabelledas‘AureaChersones’(GoldenChersonese)by the1513mapfromMartinWaldseemuller ThisisanindicatorofEuropeanignoranceofthecomplexcoastalregionsand individualsettlementswithinthearea.Itwasonlyby1548thattherewasashifttowardsmorepreciserepresentations. GiacomoGastaldi’s1548map“IndiaTerceraNovaTabula ”showsCCincaPula(CapeofSingapore).Thisisamongstthefirstrecordedinstancesofadistinctreferenceto Singapore,thoughframedmoreasacoastallandmarkthanasignificanttradinghub.

AbrahamOrtelius’smapofSoutheastAsia“Indiaeorientalisinsularumqueadiacientiumtypus”of1570 buildsonthisgrowingrecognition,listingSingaporeasCincapura.Thischangeinnamereflectsanincreasingawareness ofthelocation’sidentity,transitioningfromameregeographicmarkertoaregionwithrecognisedsignificancewithin SoutheastAsia.Finally,CornelisClaeszandTheodordeBry’sMap(1599-1628)demonstrateshowEuropeaninterestin SoutheastAsia’smaritimeroutesmatured.271599-1628ThepairachievedthismapviatracingDutchcolonialvoyages topinpointcriticaltradingpoints.ThisshowshowSingaporeemergedasacrucialnodeintheDutchspicetradenetwork. Assuch,Singaporehasshiftedfromavaguelydefinedwaypointtoacriticaleconomicasset.HazardsWhileearlymaps ofthe1500srevealthegradualrecognitionofSingapore,themapsoftheearly17thcenturybegantocapturethegrowing complexitiesofnavigationandgeopoliticaltensionintheregion.ThisdynamicchangereflectshowSingapore’smaritime heritagewouldhavetoencompassthehazardsandsocialtensionamongstinvolvedgroups.[11]1607The1607mapofde BrystandsoutfordepictingnotonlythegeographicallayoutofSingaporeStraitbutalsonavigationalhazardsand politicalconflicts.Theinclusionoffeatureslike‘ SincaPora(i.e.Singapore),“StraetvanSincaPore(StraitsofSingapore)andValschSincaPore(FalseStraitsof Singapore )reflectsthecomplexityofnavigatingthesewaters.Moreover, themapdepictstheDutch-PortuguesenavalconfrontationinOctober1603 ,markingasignificanteventinSoutheastAsianmaritimehistory Thisconfrontationhighlightstheregion’sstrategic importanceasabattlegroundforcolonialpowers,withSingaporeandJohorLamaservingascriticalnodesinregional alliances.Themap’sshowcaseofthenavalvessels,navigationaldepthsandenvironmentalhazardsillustratesthe29 technicalprecisionneededbytheseshipstonavigatethewaters.ThisoffersearlyevidenceofSingapore’ssignificance, notjustintraderoutesbutasapoliticalflashpointinEuropeancolonialrivalries.StraatSincapuraMapStraatSincapura Map(c.1650)furtheremphasisestheenvironmentalchangesinthestraitbyfocusingonenvironmentalandbathymetric datatoshowgeographicalchallengesandnavigationalroutes.Together,thesemapsdemonstratehowSingapore’s maritimerelevanceextendedbeyondtradebyshowingthetechnical,environmental,andgeopoliticaldynamicsthat shapeditsdevelopment.UrbanandConservationPlanningBythe19thcentury,asEuropeandominancesolidified, attentionshiftedfromnavigatingtheseastocontrollingland-basedresources.Thistransitionwouldnotonlymarktherise andfallofBritishinfluencebutalsohowsuchchangeswouldshowthepoweroflandoversea.WhilethelegendofSang NilaUtamaprovidesanearlyindigenous(albeitmythical)narrativeaboutSingapore’sorigins,colonialhistoriography haveshapedthenation’splanning,withthemostwell-knownfigurebeingSirStamfordRafflesandtheJacksonPlanof 1822[12].Asaproposedscheme,themainaimoftheplanwastomaintaintheorderofSingaporeasacolonyfoundedin 1819.Unfortunately,thisplanwasneverexecutedproperlybutitservedandshowedusaguideforhowSingaporewas supposedtobedeveloped,includinginconservationeffortstoday.Additionally,theinfrastructureformaritimeactivities, includingtheharbours,riversandpiersespecially,wereestablishedwithdirectconnectionstoethnicenclaveslikethe Johnston’sPier(predecessortoCliffordPieranddemolishedin1970)wassituatedintheheartofChinatownandcatered toChinesetradingactivities.WorldWarIIwasarguablytheturningpointforland-baseddominance.Notonlyintermsof howspaceswereutilisedbutalsodeterminingwhocontrolledtheland.ThefallofSingaporein1942putthe vulnerabilitiesoftheisland’scoastaldefencesonfulldisplay.ThisincludedtheBritishdestroyingtheJohor-Singapore Causeway,31whichmadetheJapanesenavigatetheJohorStraitusingmakeshiftmethods,includingsmalljettieslikethe SembawangJettyandswiftlyfocusonadvancingthroughthejungleterrain.Thistargetonland-basedtransportation systemswasespeciallyevidentinthe1942TokyoNichinichiShimbunshamap.[13]Themapdoeshighlightmaritime areaslikethenavalbasesinSembawangandminefieldsinnearbywaters.However,thelargestareamarkedinred belongstothetransportationnetworksliketherailwaylinefromMalaysia.Eventheforestsandhillsthatusedtocover Singaporewereclearlydepictedwithdifferenttreesymbols.IfterrainandinfrastructureinfluencedJapanesemilitary strategy,theirdominanceinSingaporewouldalsohavetobebasedonland.Maritimespaceswereusedtacticallyrather thanstrategically,diminishingtheirlong-termsignificanceinfavourofland-basedsystems.Landtookonevenmore economicalprominenceovertheseawiththeyear1964.[14]Notonlywasthattheyearbeforeindependencefrom Malaysia,but theSingaporeTouristPromotionBoard(STPB)neededtopromoteSingaporeasatouristdestination tosetitselfapartfromthecountryitwasgoingtoleave.Thismarkedthebeginningofanofficialshifttowardsviewing heritageasacommoditytoattractglobaltourists.Figure3:1965MapsbySTPBforTours[15]By1984,theTourism TaskForcehadbeensetup tolookintohowtoboosttourisminSingapore .Assuch,tourismsolidifieditspositionasaproduct/commodityby1986 withthedevelopmentoftheTourismProductDevelopmentPlan aimedatrevitalisinghistoricdistricts.Thus,aCivicandCulturalDistrictMasterPlanExhibitionwasheldtobringout thedistinctivehistoricalqualitiesoftheareaandenhanceitsrelationshipwithOrchardRoad,MarinaBayandthe SingaporeRiver

by1989.OrchardRoadinparticularnaturallytransformedintoacommercialareaasitwasalreadysurroundedbyseveral businessesthatwouldbenefitmassivelyfromthebuildingoftheNorth-SouthMRTlinestations(Orchard,Somerset,and DhobyGhautstations).Unfortunately,theSingaporeRiverandMarinaBayhadtobereimaginednotashubsoftradebut ascuratedtouristattractions.Sincetheriverclean-upcampaignin1983,bumboats[16]thatwereonceessentialfor transportinggoodsarenowferryingpassengersalongtheSingaporeRiverforsightseeingandpleasurerides.Thismere delegationtoriver-taxisbylicensedoperatorswhopickupanddisembarkatBoatQuayandClarkeQuayreflectsthe transitionofaworkingwaterwayintoaleisure-orientedexperience.Meanwhileasseeninthe1988map,landareaswere carefullyplanned.ThisincludestheriseoftheMRTstationsin1987[17]thatsoonbecameessentialtransportation systemstonavigatearoundthecountryasseenintheexpandingnetworks.Thus,waterspacesareretainedonlyinsofaras theycomplementedtheurbandevelopment.Figure4:1988MapofSingaporewiththenewMRTStations[18]Overall AnalysisHence,thesemapsstressonSingapore’sgeographicpositionbeingessentialtomaritimenavigationandglobal trade.Thissignificanceisreflectednotonlyincolonialambitionsbutalsointhetechnicalandenvironmentalaspects crucialfornavigation.ThemapssupportthethesisbydemonstratingSingapore’historicmaritimerole,justifyingthe needformaritimeheritageconservation.TheyshowthatSingapore’sdevelopmentwasdirectlytiedtoitsstrategic locationinmaritimeroutes.Conservationeffortsthereforeshouldmakeuseofthisnavigationaldataandinfrastructure thatformedthefoundationofSingapore’sidentityasamajorport.However,thesemapsreflectcolonialandEurocentric perspectives,focusingonEuropeantradeambitionsandnavigationalneedswhilesideliningindigenousmaritime practices.Thedocumentationisthuslimitedinacknowledginglocalcontributionstomaritimehistory Thethesisthus emphasisesamoreinclusiveconservationstrategytorecognisebothcolonialandlocalnarratives.Additionally,thethesis willincludetheconservationofintangibleheritage(navigationalknowledge)alongsidephysicalinfrastructure,bridging thegapbetweentraditionalpracticesandmodernconservation.MainCausesTheshifttowardsland-baseddevelopment inSingaporereflectstheprioritisationofurbangrowthovertheconservationofmaritimeheritage.Thishasledtopolicy gapsthatneglecttheintegrationofmaritimespacesintocontemporaryconservationstrategies.Additionally,thereisa significantgenerationalandculturaldisengagementfrommaritimeheritagesitesandinthepolicies.Theassumptionthat communityinvolvementaloneissufficientforsustainingheritageoverlookstheneedfortargetedoutreachandeducation initiativestofosteradeeperappreciationforSingapore’maritimehistory Together,thesefactorsuncoveredviathis literaturereview underscoretheurgentneedforamoreinclusiveandholisticapproachto maritimeheritageconservation.MethodologyEthnographicFrameworksHavingidentifiedthemainpotentialcauses,the methodologyneedstogobeyondtheliteraturereviewwithkeyresearchquestionsbasedonresearchgaps.Hence,these researchgapsarederivedfromseveralethnographicframeworksandhighlightedincorrespondingcolourswithinTable A.Bylinkinganyinformationdeemedinadequateormissingtotheissues,eachresearchquestioncanthenberootedin specificareasthatneedtobeaddressed.KeyframeworksincludeSpradley’s9dimensions,AEIOU,Sotirin,andPOSTA. Spradley’s9dimensionsSpradley’s9dimensionsisaframeworkusedtoanalyseandunderstandculturalsettings.These dimensionscanprovideastructuredwaytobreakdownandinterpretvariousaspectsofhumaninteractionandbehaviour withinthemaritimespacesasshownbelow;1)Space:Thephysicallayoutorsettingwhereculturalactivitiestakeplace. KeyplacesincludethefollowinghighlightedinblueandshowninTableA.2)Actors:Thepeopleinvolvedinthe maritimespaces.

Singaporehastwomaincommercialportterminaloperators,namelyPSACorporationLimitedandJurongPort

PSACorporationLimitedmanagesthemajorshareofcontainerhandlinginSingaporewhileJurongPortPteLtdis Singapore’smainbulkandconventionalcargoterminaloperator.Mostof theusersofthespacesarevariedsoitwouldbegoodtocapturetheminsiteobservations.[23]383)Activities:Mostof theseareasareabletosupportawiderangeofactivitiestobestudiedinsiteobservations.Thisincludestransport, shipping,recreationalboating,andfishing.Inparticular,themodernrecreationaluseslikeleisureboatingandfinedining arehighlightingtheshiftfrompurelyindustrialusetomixed-useareas.Sembawang/MataJettyhastobehighlightedhere asthejettyillustratesandreflectsthenaturalabundanceofwildlifeintheareathroughitssimplelayout,fostering connectionsamongvariousfishinggroupsandhobbyistsduringcommunalactivitieslikecrabbingandfishing.Other historicallysignificantmaritimesiteslikeLimChuKangPierhavebeenabandonedandfencedoffduetonotbeingas accessibleasSembawangJetty.Thisdualroleasanaturalsiteandarecreationalhubhighlightsitscontinuedrelevancein modernSingapore,bridgingthepastandpresentthroughasharedappreciationofhistoryandthenaturalenvironment acrossgenerations.However,itshistoricalareasliketheBeaulieuHouse[24]aremostlyknownonlyforitsadaptivereuse asarestaurant.4)Objects:Mostmaritimespacescanaccommodatevarioustypesofvessels,withharboursinparticular beingonalargeenoughscaletotake containerships,bulkcarriers,cargofreighters,coastersandlighters

Additionally,therearevariousphysicalitemsthatsignifytheculturalandhistoricalsignificanceoftheseareas.Notable relicsincludetheiconicredlampsatCliffordPier[25].Infact,duetohowmanysymbolsarepresentatthesite,Clifford Pierhasbeenchosenasoneofthesitestoinvestigate.Thisblendoffunctionalandsymbolicobjectsshowhow intertwinedthecommunity’sidentityiswiththemaritimelandscape.5)Acts:Thesmallerunitsofactivitiesorindividual actions.Everydayactsincludeloadingandunloadingcargo,maintainingvessels,fishing,andrecreationalactivities.6) Events:Pertinenteventsinthesespacesincludetheirestablishmentandcontinuousexpansionorclosure.Basedonthe literaturereview,thedevelopmentofKeppelHarbourinthe19thcenturyisanotableeventtobeinvestigated.7)Goals: TheprimarygoalsofSingapore’smaritimesectorincludesmaintainingitsstatusasaleadingglobalport,promoting sustainabilityinmaritimeactivitiesandintegratingheritageconservationwithmoderneconomicneeds.Onacultural

levelthough,Singaporeonlyseesthebuildingsmostrelatedtothecountryand/orcanpromotetourism.8)Feelings:The emotionalresponsespeoplehavetowardspaceandtheirexperiences.However,thesefeelingsneedtobebetter articulatedandhencecheckedintotoseehowtoelaborateonpeople’sexperienceswithmaritimeheritagespaces.9) Time:Timeofcourseinfluencesthespaceasseenwiththeevolutionofnotjustthemapbutalsotheconservationpolicies thatcontinuedtoonlyfocusonspecificphysicalstructuresmeanttopromoteSingapore.AEIOUFrameworkTheAEIOU frameworkcomplementsSpradley’s9dimensions,wherewefocusontheinteractionsandenvironmenttraitsdescribedas theactivities,usersandobjectshavebeencoveredalready.1)Environment:Theenvironmentsurroundingthesemaritime spacesplays acrucialroleinshapinguserexperiencesandinteractions.InSingapore,theretentionof theislandtypologyisincreasinglychallengingasthenation’sfocusshiftstowardsland-basedtechnological advancementsthataremoreeasilyaccessibletothegeneralpublic.Allbecauseoftheprivatisationofland.Privatisation cancreateascenariowherecommercialintereststakeprecedenceoverheritageconsiderations,thustransformingspaces likeCliffordPierintotheFullertonHotel[25]asanexclusivediningandleisuredestinationthatcatermoretotourists thantolocalcommunities.Incontrastthough,shophousesinlandaremoreaccessibletothepublic,withthefive-footway beinganarcadedcoveredwalkthatrunsalongthefrontofalmostallcommercialshophouses,evenofferingshelterfrom theeffectsoftheweather.[26]Thedifferenceinthesezonesaddtoagrowingdisconnect,unlesssimilarfocalpointsare addedtodrawmorepublicattentiontothemaritimeareas.Moreover,thesetypesofstructuresareunderthreatdueto constantexposuretowavesandstormscausingerosionandstructuraldamages,aswellasrisingsealevelsduetoglobal warmingandpollutionmakingtheseenvironmentslessfriendly.2)Interactions:Theblendofhistoricalcontinuityand modernadaptationwithinmaritimespacesissomethingtobeobservedmore.SembawangJettypreservesitssocialrole asafishingspotandmaritimeviewpoint,continuingitsusesincethe1900s.POSTAThethirdframeworkisPOSTA whichhelpsorganiseobservationsindesignfields.TheacronymstandsforPeople,Objects,Situation,Time,and Activities.Here,thisstudyfocusesonSituationspecifically.1)Situation:Thiscomponentreferstothecontextorsetting inwhichcertainbehaviours,actionsorpracticestakeplace.InthecaseofSingapore’smaritimeheritage,thisrefersto bothphysicalspacesandsocial-culturalelementswherethisheritagemanifests.IncontemporarySingapore,young Singaporeansneedtangible,accessiblefocalpointstoconnectwiththehistoricalmaritimenarrative.Yet,manyexisting culturalanchors,likeplaquesormaritimerelics,areeitherignoredbythepublicorplacedinareasthatarenotconducive toengagement.Traditionalkelongs,whicharewoodenoffshorefishingplatforms,couldhaveservedasonesuchfocal point.KelongsrepresentadirectconnectiontoSingapore’sfishingpast.However,mostkelongstodayareeitherprivately owned,inaccessible,orhavefallenintodisuse.AcompellingexampleisthekelongownedbyTimothyNg,locatedoff PulauUbin.[22]PulauUbinisconsideredout-of-the-wayfortheaverageSingaporean,beinganislandnortheastofthe mainland.Withthelackofaccessibilityanddecreasingneedforthekelongsasfishinggrounds,thekelongisgoingto ceaseoperationsduetofinancialdifficulties.TheSingaporeHeritageSociety(SHS)isactivelypetitioningtoretainthe kelongsasaneducationalandcommunalspacebutafeasibilitystudyisneededtodeterminethecostandinfrastructure neededforconservation.IfkelongslikeTimothyNg’scouldbeconservedandrepurposedassustainabletourismor publiceducationspaces,therecouldbeatangibleconnectionintothefishingpracticesandcommunallifethatwasonce integraltoSingapore’sidentityasanislandnation.Alreadykelongsusedtobepartoflearningjourneysbutmostschools havestoppedgoingthereduetohowfarawaythekelongsare.SotirinFrameworkFinally,theSotirinframeworkin particularisaimedatuncoveringthecomplexitiesandrichnessofhumanexperiencesandrelationships.Keyaspects includeTerritory,People,StuffandTalk.Inthiscase,SotirinmakesuseoftheTerritoryandTalkdimensions.Singapore’s maritimespaceshavelongbeendividedalongbothphysicalandsociallines.TheSingaporeRiveritselfwassegmented intodifferentterritories,withtheHokkiensneartherivermouthatBoatQuayandtheTeochewssettlingfurtherupstream nearColemanBridge.Theseterritorialdivisionswerenotjustgeographicinnaturebutalsorepresentedeconomicand socialdistinctionwithintherivercommunities.Wealthiermerchantsandtraderscontrolledthemoreprofitableand accessiblepartsoftheriverwhilethepoorerlabourerslivedandworkedinovercrowdedandoftenhazardousconditions furtherupstreamoronthefringesoftheback.Yet,thesedialectgroupsintermingledinriversideconversationsabout tradeandcommerceduringcommunalactivities,albeitindirectly Thehighersocialstratawouldnegotiatedealsandthe workerclasswouldgossiponthesetrades.Culturaltransmissionsincludedstorytellerswhowouldreciteoralhistory And then,imaginemoredisplacementswiththe1983RiverClean-Upcampaign.Silencereplacedtheinformaltalks,andeven theboatswerechangedtotouristones.Adaptivereusewasthemainconservationstrategytoproducedozensofcafesand restaurants.Whiletherearesomeheritagetoursthatgoaroundtheriver,thesetoursarestillprimarilyforforeignersand notsomethingtheaverageSingaporeanwouldwanttogoon.[27]ResearchQuestionsAfteranalysingtheframeworks, thefollowingresearchquestionswereformed;●RESEARCHQUESTION1(Evaluative)(Spradley'sFeelings;Goals;All Framework’sActivities):HowshouldeducationalinstitutionsinSingaporeincorporatemorecomprehensivemaritime historyprogramstoenhanceSingaporeans’understandingofthesespacesinthenation'sheritage?Thecomparison betweentheframeworkssuggestsaneducationalgap,wherecurrentprogramsmaynotadequatelyaddresstheimportance ofmaritimeheritage,particularlyconcerningyoungerSingaporeans.Certainhistoricalfactsareknownbutthereisno emotionalconnectionreinforcedinsuchactivities.Thereisaneedforresearchonhowtointegratemaritimehistorymore fullyintoeducationalcurriculatobridgethisgap.●RESEARCHQUESTION2(Testing)(Spradley'sGoals,Actors): ShouldSingapore’sgovernmentimplementstricterregulationsontheredevelopmentofhistoricaljettiesandharboursto balanceeconomicgrowthwiththeconservationofmaritimeheritage?Thereisatensionbetweentheneedtoconserve historicaljettiesandharboursandthepressuretoredeveloptheseareasforcommercialpurposes.Thistensionreflectsa broadergapinpolicyandplanning,wherethebalancebetweenheritageconservationandeconomicdevelopmenthasyet tobeclearlydefined.●RESEARCHQUESTION3(Main)(Spradley’sActivities;AEIOUUser,Interactions;Sotirin’s

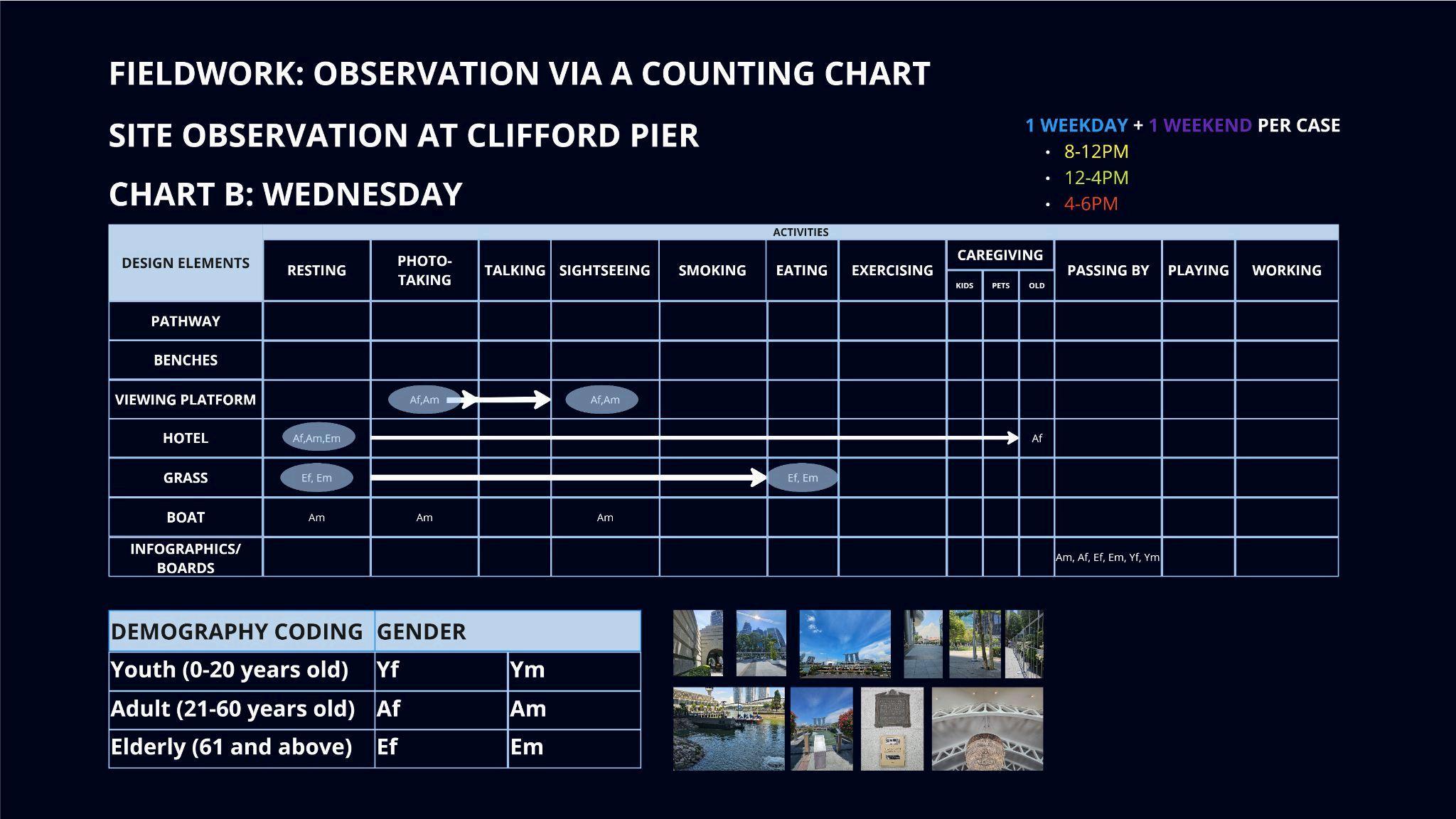

Talk):Thisthenleadsustoourmainresearchquestion:Singapore'sharboursandjettieswerecentraltoitsdevelopment asamaritimehub.Why,despiteextensiveconservationinitiatives,hastherebeenadeclineintheconservationofthese sitessincethe1990s,particularlyconcerningengagementbySingaporeans?Thecross-examinationamongstthe frameworkshighlightthelackofengagementandawarenessamongSingaporeansaboutthesignificanceofjettiesand harbours,despiteconservationefforts.Thespecificactivitiesandinteractions(heritagewalks,workshops,etc.)are mentioned,butthereisagapinunderstandingwhytheseeffortshavenotfullyreachedorimpactedSingaporeans, includinghowwell-knowntheyare.InterviewsandSiteVisitsInordertoaddresstheseresearchquestions,amixedmethodapproachwasemployed.CasualInterviewsWhilecasual,theinterviewswereeffectiveinsupplementingthe observationsofthemindsetsoftheusersofthemaritimespace.Participantswereencouragedtosharetheirthoughtson Singaporeandlostactivities.Specificobjectivesincluded;-FindindingouthowmuchofanislandSingaporeisto everyone:WhatdoyouthinkSingaporeisintermsofgeography?-Gatherallmaritimefeaturesthoughtof(ifany)and anylostactivities:WhatdoyouthinkSingaporehasinitsmaritimespaces?VSWhatdoyouthinkSingaporehasinits architecture?-Chartandseehowoftentheoverlapsare:IdentifyingpatternsandtrendsacrossindividualresponsesTogo beyondthenotesistodrawmeaningfulinsights.Theprocessbeganbygatheringrawdatafromthevariousactivitieslike notes,photosandobservationuseractivities.Inthiscase,rawdataisfrombehaviouraldatawiththeobservationofusers inthemaritimespaceandparticipatorydesigndatawiththeinterviewresponses.Thisrawdataisthentranscribedand organisedinavisualformasseenbelowinFigure5;Figure5:AnalysingParticipatoryData(Author’sownreferenced fromFrog[28])Next,dataisgroupedbasedonindividualparticipants.Eachparticipant’sthoughtsandfeedbackare clusteredtoseecommonthemesorrecurringobservations.Fromtheseclusters,thenextstepistoidentifythe ‘opportunityclusters’.Theserepresentareaswhereuniqueinsightsorpotentialopportunitieslie.Patternswithinthe clustersarethenidentified.Thishelpsinunderstandingoverarchingtrendsorcommonviewpoints.Finally,theinsights areanalysedbasedonasetofcriteria.Here,itisthefocusareas,designideas,designprinciplesandarchetypes.Thisis thestagewheretodecidehowparticipants’perceptionsalignwiththeproject’sgoal.SiteObservationsAlongwiththe interviewscamesiteobservations,particularlyatCliffordPier,KeppelHarbour(viewedfromVivoCityasunableto cross)andSembawangJettyviacountingcharts.Countingchartswouldprovideanorganisedmeansoftrackingpublic behaviourandinteractionswiththedesignelementsfeaturedinthesespaces.Theuseofdemographiccodingand timeframesallowsforadetailedunderstandingofsiteusagepatterns.Furthermore,therearearrowstoshowrelations betweentheobserveddemographicsandtheirinteractions.Therearevariousdemographicgroups,categorisedby presumedageandgender;-Youth(0-20yearsold):Yf(female)andYm(male)-Adult(21-60yearsold):Af(female)and Am(male)-Elderly(61andabove):Ef(female)andEm(male)Designelementsrefertothevariousphysicalelements. Commononesinclude;1)Pathway2)Benches3)ViewingPlatforms4)Hotels/Residences5)Grass6)Boat7) Infographics/BoardsActivitiesmostnotablyobservedinthesespaceswouldbe;1)Resting2)Photo-taking3)Talking4) Sightseeing5)Smoking6)Eating7)Exercising488)Caregiving(forkids,pets,elderly)9)Passingby10)Playing11) WorkingObservationswereconductedovertwotimeperiods:oneweekdayandoneweekendacrossthreetimeslots;8:00AM-12:00PM-12:00PM-4:00PM-4:00PM-6:00PM

Therefore,therecanbebetterunderstandingofhowthesespacesfunctionandthediversewaystheyareutilisedbythe public.SurveysAfterconductingtheinterviewsaswellasperformingsiteanalysis,asurveywasdonetoevaluatethe hypothesesand/orsolutions.Essentially,thesurveyhasthefollowingaims;-Findoutwhichfeaturesimpedethefeelings ofislandnessevenintheharbours/jetties-FindoutwhytheycontinuetocomeThesurveyfollowsamultiple-choice structurewithoptionsderivedfromresearchandinterviewandsomeopen-endedquestionstobediscussedintheresults sectionlater Thesurveyhastogatherafewdescriptiveinsightswithintheopen-endedquestions,thusgeneratingaword cloudofthedifferentanswerstowardsthequestion.ResultsInterviewResultsTeninterviewswereperformed.Lookingat theresponseswillgiveabasicbackgroundintermsofwhatextentisSingaporeanislandandhowuniqueitis.This allowsatabletobeplottedthatcandetermineifthereisacorrelationbetweentheconceptof‘islandness’and ‘uniqueness’.Throughaccounts,intervieweesdescribedtheirexperiencesoflifeinSingapore,withmostchoosingto strikeabalancebysayingSingaporeisanisland-city.However,whenaskedtoelaborate,moreurbantermspoppedup andweremorerelatedtolandformsfoundinSingapore.Thisincludedfindingoutwhatarchitecturalfeaturesin Singaporecometomind,likeshophousesandHDBs.Eventhemostmarine-relatedspaceswereabouttheglitzyMarina Bay.Moreover,mostdonotfeellikethereisadifferencebetweenthemarinespacesinSingaporewhenpromptedto thinkmoreaboutthejettiesandharbours,deemingthemboringandnotasoutstandingastheotherformsofarchitecture. Whenitcametotalkingaboutthenaturalenvironmenthowever,theinterviewee’sappreciationforwildlifeinparticular wasprominent,mostcitingtheseaviewandbreezeandhowmanyfishestheycouldcatch.SembawangJettyinparticular waslaudedforthevariousspeciesfoundinitswaters,includinggroupers.Assuch,theseclusterswereformed;●Nature: Appreciationofwildlife●City:Appreciationofthecity●Residential:HDBsandotherspaces●Heritage(Land-based): Shophouses,monuments,etc.●Heritage(Maritime-based):Piers,jetties,etc.Fromtheseresponses,itisclearthatmost oftheurbandevelopmentsthatarrestattentionarestrikingfocalpointsthatstandoutduetoscaleandforms.Any perceptionof‘islandness’tendstobedilutedbythesedevelopmentsbutthiscouldbeanopportunitytomakesimilar attractionsthatwoulddirectthefocustomaritimeareas.Assuch,agreatopportunityclusterscomesfromblending architecturalhighlightswithmarine-basedattractions.Someparticipantsconsistentlydownplaytheuniquenessofmarine spacesbutemphasisetheirappreciationfortheseaview Thisindicatesasecondopportunityclusterforenhancingthe visibilityofmaritimespacesviamorecompellingandfocusedattractions.Theoverallpatternisabouteaseofviewing whichthenmeansthefocusareawouldbetoprioritisemarine-basedspaceswithclearvisibilityandaccessibilityto historicalandstrikingelements.Designideascouldbeopenspaceswithprinciplesrootedinnatureandthebuilt environment.Thisapproachnotonlystrengthensthevisibilityofmaritimeheritageintheseareasbutalsotransforms

themintodynamicfocalpointsthatcelebratethecityanditshistoricaldepths.SiteObservationResultsItisnotedthat arguablythemostpopularandcommonactivityinthesesitesonbothdayswascaregiving.Mostwerespeakingintheir nativetonguesforthelocals,especiallyforthosemindingtheelderlyduetotheirelderspreferringtospeakintheir respectivedialects.Itisnotedthatthevisibilityofcertainactivitiesliketalkingweresignificantlylessforprivacyreasons butthiscausedtheoverallareastobeextremelyquietonweekdaysespecially Weekendsnaturallysawmorefamilies comingtotheareasbutforthemaritimeareaslocatedinthecitylikeCliffordPierespecially,mostofthesegroupswould bepassingbytheareaorjusttakingpictures.NobodyevenbotheredtolookatthetinyplaquerightattheFullerton Hotel’sentrance.Havingrefinedtheunderstandingoftheproblemtoahigherdegreeofclaritywiththeseobservations, theproblemisnowspecifictohowSingapore’sidentityasanislandnationcanbeconservedandrevitalisedviathe designofthemaritimespacesandinformationhubsthatengagethepublic.Theseobservationshelpchecksomeaspects and/orproposedsolutionswithintheanswersforthesurvey.SurveyResultsThesamplesizewaseleven.Most respondentswere25-44yearsold(45.5%)andarestudents(45.5%).Participants’choicesonwhatruinsthe‘islandness’ ofaplaceindicatecommonbeliefsonwhatdifferentiatesanisland.Theseincludelimitedseaviews,absenceofmaritime elementsandpollutionbeingfrequentresponses.Highratingsonnatureandaccessibilityreinforcethesetraitsarevalued forenhancingconnectiontomaritimeheritagesites.Acommonwordchosentodescribemostmaritimeheritageareas wouldbe‘Serene’.Thisisinlinewiththeirreasonsforvisitingmaritimeheritagespacestorelaxinvariouswayslike withphotography.Anyfutureengagementactivitiesthusaresimilarinnatureandareconnectedtonature.Ifso,any designsolutionstoimproveawarenessoftheheritagevalueofthesesitesmustbeconnectedtonature.Already,thereis anoverwhelminglackofinitiativesrelatedtomaritimeheritageaccordingtothesurvey,with72.7%notencounteringany programsthatteachthemaboutSingapore’smaritimeheritage.Overall,thesurveyresultssuggestthatastronger connectionbetweenthecity’snatureanditsmaritimeheritagecouldredefinehowSingaporeansengagewithitscoastal spaces,increasingvisibilityofthesespacesandbeingpartofeducationalefforts.DiscussionMaritimeHeritageasthe NationalIdentityTheprocessofheritageinvolvestherecognitionofthesites.Inthecontextofmaritimeheritage,that wouldinvolvesignificantmaritimelandscapes,structuresandtraditions.Alloftheseaspectsmustthenfitintoabroad conservationframework.Keyenablerstothisactincludegovernmentalpoliciesandlocalcommunitieswhoadvocateor makeupthemaritimeheritagesceneinSingapore.Meanwhile,driverswouldbetheincreasingrecognitionofthe importanceofnationalidentitywiththesemaritimeheritageareas.Thus,thetoolsandprocessesemployedinheritagemakingassolutionswouldbeeducationalinitiatives,designelementsforcomfort,andtechnologiesthatenablebetter visualisationoftheaffectedareas.NewFrameworkandSolutionsThereshouldbeasingularframeworkfocusedsolely onmaritimeheritagethatconsolidatesthecurrentfragmentedapproachesusedforconservation,education,and redevelopment.ThisframeworkcancomefromthemergeroftheSixCriteriaforConservationandtheHeritageBanding Framework.Withintheframework,therewillalsobesolutionstoboostwhatevervalueorfeatureisconsideredlackingif thesitewantstobeconsideredasrelevanttomaritimeheritage.1)PolicyandLegislationwithHistoricValue-The surveydatasuggeststhatrespondentsvaluehistoricalsignificance/communityrolesofmaritimeheritage.Thereisalso greaterdesireformoreinformativeheritageprogrammesandnoted54theimportanceofmaintainingelementslike kelongs.Hence,therecouldbespecificzonestoregulateheritageprogrammingandensurethearearemainsauthentic withitselements.-Thesespecificmaritimezoneswillcomefromassessingthehistoricvaluetothesitesconnectedto significantevents,individuals,andgroups.(eg.,Cashinfamily’sroleatLimChuKangPier)2)Marine-SpecificCriteria withAestheticsvalue-Participantsforboththeinterviewandthesurveymentionedthatthelackofmaritimeelements likefishingboatsasfactorsthatdefractfromthesenseofauthenticmaritimeatmosphereandiftheyonlyseecity-based elements.-Todrawappreciationtowardstheseseeminglymundanestructures,therecanbegamifiedmobileappswith thetaskstoguidethroughtheseaspectssuchasHiddenSGcreatingaself-guidedoutdoorgamethat usessimpleWhatsAppmessagesandanartificialintelligencechatbottohelppeoplefindthemorehole-in-the -wallplaces.Figure8:HiddenSG’screatorLimYeeHung[29]3)ActivitiesforSocialandCommunalValue-Thereisa needtocapturehowcertaincommunitieslikefishinggroups,boaters,andlocalresidentsinteractwithandusethesesites asplacesofidentity,culture,andpractices(eg.,tradepracticesatKeppelHarbour)-Thesespacescanremainrelevant andaccessiblebydesigninginteractiveprogramsthatfosterengagementsuchasstudentprojectsandstorytelling initiativesbytheelderly.4)MaritimeSurroundingsforGroupandSettingValue56-Assessingmaritimeheritagewithin clusterslikeconnectingjettiestolargerecosystemssuchasfishingroutescanbedoneviaarchitecturalethnographic participatorydrawings.-Severalrespondentsnotedtheirexperienceofsereneatmospheressosomethingnotintrusive likevirtualtourscanmaintainthisserenitysincetherewillbenoneedforspeaking.-Aseachpersoncontributesa drawingorrecallsaspottobeadded,theinterrelationsbetweenlandandwater-basedfeatureswillbemoreobviousas peoplewillactivelyhavetorecallimportantpartsoftheroutes.ConclusionInconclusion,thisthesishasdemonstrated thatconservingSingapore’smaritimeheritagespacesisaboutreinterpretingthenation’snaturalidentity.Byexamining variousjetties,harbours,piers,andkelongs,thisworkhasunderscoredthevalueofaconservationapproachthatgoes beyondnostalgicacts.Throughamoreinclusivestrategy,theresearchinvitescommunities,educatorsandpolicymakers toreclaimthemaritimeidentity.Whiletheworkislimitedduetothesmallsamplesizeoflessthantwenty,futureworks shouldfigureoutspecificformsthedesignelementsmusttaketonaturallyframethemaritimespacesthatwould encouragelearningabouttheheritageoftheseareas.LikehowthemerlionwillbeundergoingcleaninginDecember 2024,Singaporeneedstoremembertokeepthemaritimeelementsintactasournationalandnaturalpride.

AcknowledgementsIwouldliketoexpressmyheartfeltgratitudetowardseveryonewhohasaidedmeinmyjourneyin theMastersofArtsinArchitecturalConservationProgrammeinNUS.ToDrJohannesWidodo,thankyouforyour invaluableguidance.Yourinsightshavebeeninstrumentalinshapingmyacademicandprofessionalgrowth.ToDrNikhil JoshiandDrHOPuayPeng,thankyouforinstillingfoundationalknowledgesothatthisthesiscanhaveasoundbasis.

ToLukYingXian,adedicatedPhDstudentandteachingassistant,thankyouforyourendlessfeedbackforthedrafts. Yourinsightshavebeenamassiveboontothiswork.Lastbutnotleast,thankyoutomymum,dadandfurrybrother Loganforallthesupportrenderedthroughoutuniversity.Mymummightaswellbetheco-author.ListofImagesand TablesFigure1:TheIshikawaDiagram(page11)Figure2:TheSixCriteriaforConservation(page20)Figure3:1965 MapsbySTPBfortours(page29)Figure4:1988MapofSingaporewiththenewMRTstation(page31)Figure5: AnalysingParticipatoryData(page44)Figure6:AnexampleoftheInterviewChart(page48)Figure7:Anexampleof theCountingChart(page50)Figure7:AnexampleoftheCountingChart(Source:Author)Figure8:HiddenSG’screator LimYeeHung(page52)TableA:TheDifferentTypesofMaritimeheritagespacesobserved(page35)Listof Appendices1)Jetties:Harbours:Piers:Others:AstructurethatShelteredbodyofAraisedplatformWhatotherwater extendsintothewaterwhereshipsbuiltoverwater,bodiesmakeupwater,providingaandboatscantypicallyusedfor themaritimelandingplaceforanchorsafely,dockingboats,heritageboatsandofferingoftenequippedrecreational protectionfromwithfacilitiesforactivities,andwavesandloading,sometimesasacurrents[19]unloadings,andfishing spot[21]servicingvessels[20]-BedokJetty-Keppel-Clifford-Singapore-ChangiHarborPier:RiverPointFerryTanjongOccupying-Kelongs:TerminalPagartheformerOffshore(ChangiHarborlandingpalisadeJetty)-Serangoon pointoffishtraps-FormerHarborSingapore’sthatonceRoyal-Sembawanforefathers"wereonceMalaysiang Shipyard:acommonNavyDockyardsightin(RMN)forsecuritySingapore’sJetty/andUSwatersWoodlandswarships untiltheyWaterfrontvsthestartedtoJettycommercial dieoutin-Labradorthe1960sJettybecauseof-LimChudecliningKangJettyfishstocks-PulauUbinand,later,Jetty theadvent-Punggolofsea-PointJettybased -Sembawanaquaculturg/MataefarmsinJettythe1980s.".[22]Therearesomeplanstoturnthemintochalets/ed ucationalcentresTableA:TheDifferentTypesofMaritimeheritagespacesobservedBibliography[1]:_People:Yong, ChunYuan& NationalLibraryBoardSingapore.(n.d .).Merlion. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=f9c0fd6c-acfa-4eb0-8585-2aa155c1d74d [2]:

Johnson,H.(2018).Islandsofdesign:Reshapingland,seaandspace.Area,52(1),23–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12477 [3]:

Kong,L.(2011).Conservingthepast,creatingthefuture:UrbanheritageinSingapore .URA,1. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research /2287/[4]:CLC.( 2016.).UrbanRedevelopment:FromUrbanSqualortoGlobalCity (pp110).RetrievedMarch15,2024,fromhttps:// www.clc.gov.sg/research-publications/publications/urban-systems-studies/view/urban-redevelopment-from-urbansqualor-to-global-city [5]:Luk,YingXian.(2021).UtilitarianHeritage:ThePanopticonofNarrativesbehindIndustrialHeritageConservation inSingapore.[6]:CLC.( 2016.).UrbanRedevelopment:FromUrbanSqualortoGlobalCity (pp108-109).RetrievedMarch15,2024,fromhttps:// www.clc.gov.sg/research-publications/publications/urban-systems-studies/view/urban-redevelopment-from-urbansqualor-to-global-city [7]: CLC.(2019).Past,PresentandFuture:ConservingtheNation’sBuiltHeritage .RetrievedMarch15,2024,from https://www.clc.gov.sg/research-publications/publications/urban-systems-studies/view/conserving-the-nations-builtheritage [8]:Idon’tknowhowtociteit,butit’sfromNUSDrPuayPeng’sAC5002slides[9]:SitiNoorhidayu,B.I.( 2014).PreliminarystudyofMorphologicalandGeneticDiversityonAsianGreenMussel(Pernaviridis)inSantubong, Sarawak .https://core.ac.uk/download/301744603.pdf[10]:SearchingforSingaporeinOldMapsandSeaCharts.(n.d.).https:// biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-11/issue-1/apr-jun-2015/search-sg -old-map/[11]:EarlyMapsofSingapore.(n.d.). https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-3/issue2/jul -2007/early-map-singapore/[12]:Tan,B.(n.d.).RafflesTownPlan(JacksonPlan). https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=ed0c1981-882f-42c2-9acf-e5dae577a3ba [13]:JapaneseMapofSingapore|ChangiChapelandMuseum.(n.d.). https://www.nhb.gov.sg/changichapelmuseum/collection/artefact-highlights/japanese-map-of-singapore[14]:CLC.( 2016.).UrbanRedevelopment:FromUrbanSqualortoGlobalCity (pp107).RetrievedMarch15,2024,fromhttps:// www.clc.gov.sg/research-publications/publications/urban-systems-studies/view/urban-redevelopment-from-urbansqualor-to-global-city [15]:SingaporeTourismBoard(1965).{MapofSingapore:1stedition].Omega[16]:_People:Cornelius,Vernon&

NationalLibraryBoardSingapore.(n.d .).Bumboats.

https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid =6d2b5d54-beeb-4c12-9e2b-a261a251dfc9[17]:_People:Ho,Stephanie& NationalLibraryBoardSingapore.(n.d .).MassRapidTransit(MRT)system. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid =319cadae-e684-41bc-b7b6-3bd4b06437d2[18]:Singapore,O.(n.d.).OneMap|HistoricalMapGallery. https://www.onemap.gov.sg/historicalmaps/#[19]: Dictionary.com|Meanings&DefinitionsofEnglishWords.(2021).InDictionary.com. https://www.dictionary.com/browse /jetty#google_vignette[20]: Dictionary.com|Meanings&DefinitionsofEnglishWords.(2021b).InDictionary.com. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/harbor[21]:Dictionary.com|Meanings&DefinitionsofEnglishWords.(2021a).In Dictionary.com.https://www.dictionary.com/browse /pier[22]:Gene,N.K.(2024,September1).

FateofoneofSingapore’slastkelongshangsinthebalance.TheStraitsTimes .https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/ fate-of-one-of-singapore-s-last-kelongs-hangs-in-the-balance [23]:Terminals.(n.d.).Maritime& PortAuthorityofSingapore(MPA).https://www.mpa.gov.sg/port-marine-ops/operations/port-infrastructure /terminals[24]:BeaulieuHouse.(n.d.).

https://www.roots.gov.sg/places/places-landing/Places/landmarks/Sembawang-Heritage-Trail /Beaulieu-House[25]:

TransformingCliffordPierBuildingandCustomsHouse:TheFullertonHeritage .(n.d.).

https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/transforming-clifford-pier-building-and-customs-house-the-fullertonheritage/story [26]:The“five-footway”ofashophouse.(n.d.). https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing /1015185[27]:_

People:Cornelius,Vernon&NationalLibraryBoardSingapore.(n.d.-b).SingaporeRiver communities.

https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid =b821c72a-9035-49e8-bcb7-a95bbd9443c9[28]:Frog.(2014,March6).

BringingUsersintoYourProcessThroughParticipatoryDesign[Slideshow].SlideShare.https://www.slideshare.net /slideshow/bringing-users-into-your-process-through-participatory-design /31975488#71[29]:Lim,J.(2023,October24).

NewWhatsApp-basedgamehighlightsSingapore’shiddengems.TheStraitsTimes .https://www.straitstimes.com/ singapore/new-whatsapp-based-game-highlights-singapore-s-hidden-gems 12345691112131517202122232426283032333435363739

58596061626364656667

Exploring the Maritime Heritage of Singapore: Bridging Heritage and

Modernisation

By Izzah Sarah Binte Omer Ali Saifudeen (A0289543N)

For NUS MAArC Program AC5007 Semester 2 AY 2024/2025

Supervised By: Dr Johannes Widodo

Abstract

Singapore owes much of its prosperity to its maritime roots, having grown from a humble fishing village into the entrepôt it is today However, Singapore’s conservation efforts have predominantly focused on only the urban heritage, leaving historical jetties, piers, harbours, and other maritime heritage areas at risk of neglect or redevelopment. This thesis thus examines these maritime heritage spaces’ historical, cultural, and communal significance. The research aims to draw attention to the value of these spaces and advocate for more inclusive conservation efforts that recognise their importance.

The research highlights gaps in policy and public engagement with maritime heritage through ethnographic analysis. The case studies chosen include Clifford Pier, Sembawang Jetty, Keppel Harbour, and Kelongs. The results show that while most Singaporeans recognise the nation’s island status, their understanding centres around the urban development of Singapore rather than its maritime legacy. As a result, the proposal introduces educational tools like digital exhibits and physical focal points designed to foster public engagement and balance development with conservation.

Literature reviews further supplement investigations. Most works are secondary sources, such as analyses of ‘islandness’, conservation policies, and maps of Singapore’s historical maritime routes. Unfortunately, the dominance of Eurocentric principles in the reviewed works often overlooks Singapore’s unique multicultural heritage. Moreover, Singapore’s need for modernisation heavily influences the spaces prioritised under the nation’s conservation policies. Thus,

maritime heritage areas are often excluded from existing scholarship and policy frameworks. As such, primary sources are needed. By employing a mixed methodology that includes interviews, site observations, and surveys, this study ultimately proposes a sustainable maritime heritage conservation framework. This framework ensures these spaces remain significant in Singapore’s national identity even as Singapore evolves.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude towards everyone who has aided me in my journey in the Masters of Arts in Architectural Conservation Programme in NUS.

To Dr Johannes Widodo, thank you for your invaluable guidance. Your insights have been instrumental in shaping my academic and professional growth.

To Dr Nikhil Joshi and Dr HO Puay Peng, thank you for instilling foundational knowledge so that this thesis can have a sound basis.

To Luk Ying Xian, a dedicated PhD student and teaching assistant, thank you for your endless feedback on the drafts. Your insights have been a massive boon to this work.

Last but not least, thank you to my mum, dad and furry brother Logan for all the support rendered throughout university My mum might as well be the co-author

List of Images and Tables

Figure 1: The Ishikawa Diagram (page 11)

Figure 2: The Six Criteria for Conservation (page 21)

Figure 3: Cantino Chart from 1502 (page 26)

Figure 4: 1513 Map from Martin Waldseemuller (page 27)

Figure 5: 1599-1628 Map (page 28)

Figure 6: 1607 Map (page 29)

Figure 7: Straat Sincapura Map in 1650 (page 30)

Figure 8: Raffles Town Plan (page 31)

Figure 9: Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbunsha Map (page 32)

Figure 10: 1965 Maps by STPB for Tours (page 34)

Figure 11: Bumboats (page 35)

Figure 12: 1988 Map of Singapore with the new MRT Stations (page 36)

Figure 13: Analysing Participatory Data (page 47)

Figure 14: Word Cloud (page 54)

Table A: The Different Types of Maritime heritage spaces observed (page 64)

Chapter 1: Introduction

Meow-blub-a-bulb. That is a catfish's desperate mating cry. Can you guess what is considered a catfish? The Merlion, Singapore’s most famous hybrid icon that symbolises the island’s fishing roots and lofty ambitions. In 1964, the design for the Merlion came by merging two themes: the lion head to represent Singapura, aka the lion city, and the fish body to represent the humble origins of the little red dot as a fishing village called Temasek. Temasek was the precursor to Singapore’s success as an entrepôt, boasting a rich seafaring culture and a strategic location.1Yet, Singapore only presents itself as an ultra-modern metropolis, quietly sidestepping its deeper identity as an island nation. After all, how else can Singapore bag global superpowers and powerhouses? Although Singapore’s global standing is primarily defined by land-based architecture and technology, its historical connection to the sea runs far deeper Sadly, this is an overlooked connection in favour of improving the country’s facades. However, what if the natural identity could be the national identity?

Chapter 1.1: Objectives

National identity, often defined as a shared sense of belonging and unique cultural understanding amongst citizens, is a recurring theme in this dissertation. Natural identity is supposed to be part of this national identity, as natural identity will encompass unique environmental characteristics (including the built environment) that have historically defined a nation’s way of life. Upon looking at how the national identity has evolved, the core problem with the natural identity becomes increasingly apparent. There is a weakened connection between Singapore as a

1 Yong, Chun Yuan (2016) Merlion National Library Board Singapore https://wwwnlb govsg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=f9c0fd6c-acfa-4eb0-8585-2aa155c1d74d

nation and its natural maritime heritage, with the only link to a shared past being nostalgia due to the relentless pursuit of a city-centric identity. Such a generic focus has resulted in cultural erosion. Crucial sites include jetties, piers, kelongs, and harbours. Literature on the conservation efforts in Singapore for general buildings suggests this disconnection is not unique but is part of broader regional and global trends focusing on structures that either show a more glamorous nationality or promote efficiency on land only. Now, imagine if this issue is not resolved based on analysing zoning and urban typologies within the country In that case, future generations will become even more detached, and Singapore’s historical significance as an island nation will fade into a generic city-state identity Thus, this research dives into the maritime undercurrents beneath Singapore’s urban sheen through two primary lenses: place and time.

Place

For place-framing, specific architectural features related to maritime culture are used. This includes harbours and jetties’ trade routes, markets, ships, and waterfront activities. Specific case studies, such as the kelongs, Clifford Pier, and Sembawang Jetty, will be highlighted to show the broader maritime landscape.

Time

Secondly, the timeframe given is based on the layering of historical maps that illustrate Singapore’s long-standing role as a critical global port Crucial moments examined will be reputation advancements, wars, and shifts in land use. Although the research is relevant for all Singaporeans, particular attention in this research timeline is given to the younger generations as groups arguably the most

disconnected from the country’s maritime heritage. Such loss entails their diminished connection to the sea being replaced with faster and more accessible land-based modes of transport, a reduction in historical knowledge, and a shift in Singapore’s identity from an island nation to a city-state. The role of maritime heritage as “anchors of memory ” remains vital, allowing tangible sites like these harbours and jetties to support cycles of reinterpretation across generations. This thesis can then address fundamental research questions on policy, engagement, and conservation challenges presented later in the methodology

Chapter 1.2: Overview of Works

In order to fully digest these dynamics, a comprehensive review of relevant maps is needed to understand the historical layers, including the layout of Singapore and how maritime features have transformed throughout the decades, with particular attention to shifts in land use, trade patterns, and architectural transformations since the 1500s. Policy documents are additional tools to gather insights on the perceived value and relevance of maritime heritage in Singapore, thus assessing the extent of cultural erosion and identifying potential avenues for conservation within the local context. As noted by Brenda Yeoh, Lily Kong, and Luk Ying Xian, Singapore’s heritage conservation field follows a Western-centric trend that overlooks local historical contexts and prioritises urban structures over humble maritime spaces. Lastly, it is crucial to establish a clear definition of what constitutes an island. Should the perceived importance of these maritime sites grow over time, these locations may even become central to shaping Singapore’s national identity, reconnecting future generations with the island’s maritime past.

Chapter 1.3: Hypotheses

With a focus on conservation, there are then several assumptions to guide this research, namely related to the demographic and architectural features at risk. Young Singaporeans are the most crucial group for the conservation of maritime heritage. As future custodians, their understanding and engagement with maritime culture will directly influence how it is passed to future generations. Moreover, Generation Z in particular is considered the most digitally literate demographic2 . They are the first social generation to have grown up with access to the Internet from a young age. However, achieving a better understanding of such an intangible concept is hard beyond the textbooks. While personal anecdotes from parents or grandparents contribute to maritime knowledge, they may not be sufficient to sustain lasting engagement amongst younger generations. Modern developments and digital lifestyles have distanced these Singaporeans from real-life maritime sites such as Lim Chu Kang Jetty, whereby youth favour fictional counterparts like Liyue Harbour from Genshin Impact