MĀORI LAND SURVEYS

DIGITISATION OF THE CADASTRAL SYSTEM

CADASTRAL SURVEY OF THE YEAR

DIGITISATION OF THE CADASTRAL SYSTEM

CADASTRAL SURVEY OF THE YEAR

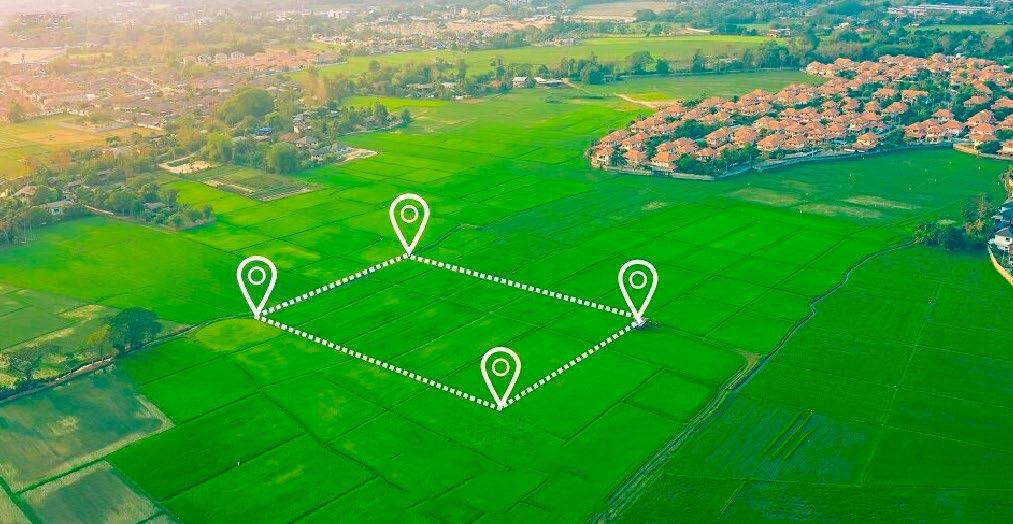

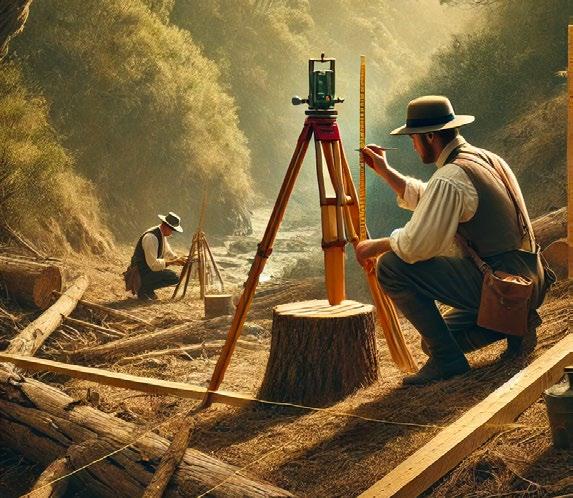

Cadastral surveyors have played an integral part in Aotearoa’s early land development from the days of the new colony when many of our provinces, counties, and townships were divided by royal charter in 1840.

New Zealand has come a long way since the days of labouring bush and steep terrain to divide land blocks. Cadastral surveying today has significantly advanced with the advent of satellite, drone and GPS technologies that ensure greater accuracy and application.

Innovations have most certainly led the way for New Zealand’s cadastral sector as they look to support many of our environmental and land development challenges that lay ahead in the future.

This edition we’re focussing on all things cadastral, featuring cadastral updates, achievements and special projects and that are making their mark and shaping the future of New Zealand’s cadastral sector.

In this edition, Kevin Taylor examines the historical background, legalities and unique attributes of Māori Land Surveys, with several interesting case studies from the Tairāwhiti Region, where many Māori landowners and shareholders are returning home to reconnect with whānau.

New Zealand Surveyor-General Anselm Haanen takes a look at the development of the digital cadastral system, from the

introduction of digitally mapping cadastre to digital cadastral survey datasets and major milestones with Landonline and eSurvey lodgement.

S+SNZ Cadastral Stream Executive Members Rita Clark and Andrew Blackman detail this year’s Cadastral Survey of the Year Awards and award winner Mark Geddes gives his account of the Blueskin Road Legalisation Survey – SO 571293, a unique road legalisation survey which uncovered approved plan conflicts and unearthed answers hidden for decades.

Following the recent awards ceremony, we showcase the winners of the 2024 Spatial Excellence Awards.

And finally, a very big thank you to all our contributors and readers throughout 2024 from S+S NZ, as we wish everyone a happy and prosperous year ahead in 2025. •

TĀTAI WHENUA

SURVEYING+SPATIAL

ISSUE 118 SUMMER 2024

A publication of Survey and Spatial New Zealand, Tātai Whenua. ISSN 2382-1604

www.surveyspatialnz.org

EDITOR

Rachel Harris

surveyingspatial@gmail.com

All rights reserved. Abstracts and brief quotations may be made, providing reference is credited to Surveying +Spatial. Complete papers or large extracts of text may not be printed or reproduced without the permission of the editor.

Correspondence relating to literary items in Surveying+Spatial may be addressed to the editor. Papers, articles and letters to the editor, suitable for publication, are welcome. Papers published in Surveying+Spatial are not refereed. All correspondence relating to business aspects, including subscriptions, should be addressed to:

The Chief Executive

Survey and Spatial New Zealand PO Box 5304

Lambton Quay Wellington 6140

New Zealand

Phone: 04 471 1774

Fax: 04 471 1907

Web address: www.surveyspatialnz.org

Email: admin@surveyspatialnz.org

Distributed free to members of S+SNZ. Published in March, June, September and December by S+SNZ.

DESIGN & PRINT MANAGEMENT

GOODHERE – www.goodhere.nz hello@goodhere.nz TO ADVERTISE

Email: admin@surveyspatialnz.org or contact Tara Ranchhod

+64 4 471 1774

Summer Edition 2024-25

Kevin Taylor, Registered Professional Surveyor

My involvement with Māori Land (ML) surveys first began after moving to Gisborne in November 1987. My first ML survey involved a partition survey to rectify the legal boundaries surrounding a marae at Hicks Bay, near East Cape, which also incorporated several surrounding blocks. Since this time, I have been involved with countless other ML surveys, mostly within the Tairāwhiti Māori Land Court (TMLC) District.

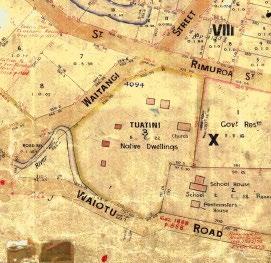

At the beginning of the 19th century, the whole of Aotearoa New Zealand was held by Māori tribal (iwi) and sub-tribal groups (hapū) according to clearly defined areas of possession with recognised, and generally accepted, rights of occupation.

Although the exact customs relating to land tenure varied in different parts of the country, there were basic principles on which there was general agreement. During these early years, it was accepted that a Māori title was communal and that any tribal rights might be classed firstly as the territory that had been in possession of the tribe for several generations and secondly the territory acquired by conquests, occupation or gift.

The purchase of land by Europeans extended between 1814 and 1840, with the majority being purchased between 1837 and 1839. Most of the larger speculative purchases were made in 1839, when Aotearoa New Zealand was first being colonised.

It was not until 1862 that the General Assembly passed the Native Land Act. The object of this Act was to make provision for a Native Land Court to decide the ownership of Māori lands. However, this Act never became fully effective and was replaced by the Native Land Act 1865.

Subsequently, there have been extensive changes and updates within the ML Court over the course of history with the scope and nature of its functions and jurisdiction to

investigate, determine and record titles of Māori customary land. It is interesting that the Native Land Act 1894 is said to have restored faith and trust of Māori people in the ML Court. The ML Court was seen in a parental role, protecting the people against the unwished loss of land. At this point, the usual formality of the European law court was not strictly observed, and the ML Court became known as a ‘people’s court’.

The ML Court is Aotearoa New Zealand’s oldest and longest established specialist court. It is a unique institution and the only indigenous land court in the world.

The Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993 (TTWMA) governs the present constitution and jurisdiction for the ML Court with seven Māori land districts.

For many Māori, occupying or building on their whenua/ land is one of the most common ways that enables a whānau to connect with an area of land in which they hold shares in.

The most common type of ML surveys applied for through the ML Court relate to partitions. Simply, a partition of Māori land is the subdividing of undefined shares in a title into two or more new titles as approved by a ML Court Order and recorded in the court minutes.

Generally, the licensed cadastral surveyor may already be engaged by the person who wants the work to be undertaken. The minutes for the Partition Order often stipulate a nominated licensed cadastral surveyor to carry out that ML survey. Costs are normally met by the shareholder who is partitioning the block.

When one, or a group, of shareholders in a title wishes to separate from the remaining shareholders and establish their own title for a defined area, they first must prepare and make a formal application to partition with the ML Court. The following supporting documentation must be

attached to that application:

For non-hapū partitions, a preliminary plan approved by the territorial authority under Part X of the Resource Management Act 1991.

For hapū partitions, a preliminary plan only.

A valuation of the land.

A list of owners of the parent title.

Consent of the shareholders to the proposed partition. Partitions are classified as either hapū or non-hapū. However, many partition surveys tend to be hapū partitions with minimal to no involvement needed from the territorial authority, and the requirements at this stage otherwise imposed by the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) to apply for consent to subdivide are also waived.

There have been instances also where the new blocks being surveyed using the ML Partition process have been below the minimum area normally permitted in the territorial authority’s District Plan. However, rules involving the need to service these new blocks are generally not required until those new partitioned blocks are developed, normally at building consent stage.

Unlike hapū partitions mentioned above, non-hapū partitions are however deemed to be a subdivision under the RMA in which the District Plan rules will apply.

When the ML Court is considering a partition application for a block, the applicant will have most often already obtained consent from the other shareholders involved. The ML Court will convene a hearing whereby the applicant can present their application to the court judge. There is also an opportunity for other shareholders to support or oppose as the case may be. At least 80 per cent of the main shareholders need to be supportive of the application to enable the court judge to reach a decision and grant a partition application. However, applications are considered on a case-by-case basis.

Once an application to partition a block of land has been granted by the ML Court, the nominated licensed cadastral surveyor is instructed by the ML Court to carry out the survey component within a specified timeframe, however extensions can be applied for in certain circumstances. This involves carrying out the survey in accordance with the Cadastral Survey Rules 2021 and lodging the digital dataset with Land Information

NZ (LINZ) for processing and ‘approval as to survey’. Once the digital dataset has been approved, the ML Court’s legal team is responsible for obtaining new Records of Title for the new blocks surveyed.

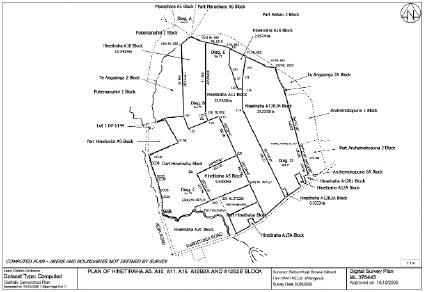

Prior to the introduction of Landonline, numerous ML Court Orders had been issued for the partitioning of Māori blocks. However, due to the prohibitive costs, mainly for Māori shareholders, to undertake the final surveying component, a large number of these blocks were never actually surveyed and monumented in terms of the cadastral survey rules at that time. As a result, this meant that these unsurveyed blocks were not initially able to be recorded in LINZ’s spatial cadastre and consequently were not visible as part of the spatial view that would otherwise show the property boundaries in Landonline.

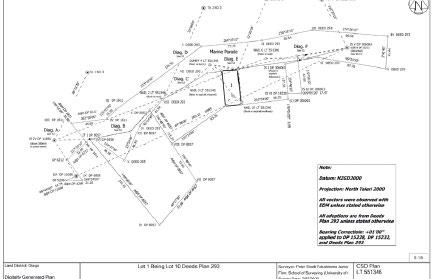

However, as a result of an initiative, a joint project called the Māori Freehold Land Registration Project (MFLRP) was undertaken between LINZ and the ML Court between September 2006 and May 2010 to try to rectify this. The Surveyor-General at the time issued the LINZS10000 Interim Standard for Computed Cadastral Survey Datasets for Māori Freehold Land, otherwise known as the Computed Plan Standard. This exercise effectively allowed for unsurveyed partition boundaries to be depicted on computed CSDs, based on descriptions prescribed in the court minutes. Unfortunately, these particular CSDs were not of a sufficient standard to enable the issue of guaranteed titles under the Land Transfer Act 1952. Subsequently they were registered as ‘computer interest registers’ in the Provisional Register. Computed CSDs have caused numerous problems for both the Māori shareholders and local surveyors. Often

shareholders will request that the boundary positions relating to these computed CSDs be identified. They may not understand that these particular ML blocks have not previously been monumented on the ground. Consequently, a simple boundary definition survey is out of the question and a full-blown ML survey often needs to be recommended. This also applies to potential new applications to partition.

Neither is it uncommon for disputes to arise between adjoining Māori blocks, especially where existing fence lines pre-date the time of the granting of the original Partition Court Orders. Had there been sufficient funding resources and a willingness to initiate a full survey, with respected topographic features at that point of time, it may well have avoided issues now that often occur.

Recently I had a situation arise whereby I was obliged to effectively move an unsurveyed legal boundary by approximately 10 metres. This adjustment was necessary so the subject legal boundary coincided with an existing old fence line that was clearly always considered as the occupation boundary between the two adjoining ML blocks. To rectify the situation, dialogue with the ML Court was required. Consequently, this scenario had a knock-on effect with adjoining ML blocks.

Prior to the introduction of Landonline, it used to be mandatory to show all topographic and occupation details on ML survey plans. In my experience the older survey plans showing these topographic and occupation details, such as urupa sites, have proved to be immensely valuable when analysing data from a historical perspective. However, with modern surveys, many of these types of occupational details are now no longer required to be collected and documented, even on occupation diagrams.

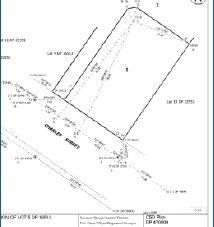

Another example is when the initial scope of our services was to re-survey and monument one of these computed CSDs which comprises a marae and other associated structures. During the initial assessment it was discovered that one of the unsurveyed legal boundaries depicted on that computed CSD plan runs through the marae meeting house (see Figure 3).

Subsequently, we are now looking at the option to rectify the situation by means of potentially undertaking a re-partition survey. This matter has been referred back to the marae trustees. There are at least three other adjoining ML blocks affected whose shareholders will need to be consulted. This issue has resulted in a convoluted process for all parties involved to work through. The final approval, however, will still need to be put through and obtained from the ML Court. This also raises issues in respect to costs, and who pays to rectify the situation. Unfortunately, situations like this are reasonably common.

In conclusion, a boundary reinstatement survey for any ML blocks shown on computed CSDs should not be undertaken unless those ML blocks have previously been officially monumented on the ground. Rule 114(1)(c) of the Cadastral Survey Rules 2021 states that a boundary reinstatement survey must not be used if the boundary point being reinstated is on a Māori land CSD that is annotated ‘computed plan – areas and boundaries not defined by survey’. The MFLRP unsurveyed boundaries are indicative only and must not be relied upon as authoritative boundaries. Another word of caution relates to checking the wording on the title for the ML block where the memorial says will not be finally constituted a folium of the register until a plan has been deposited pursuant to section 167(5) Land Transfer Act 1952.

Since Covid-19, many Māori landowners/shareholders have returned home and reconnected with their whānau and whenua. The recent 2023 census for the Tairāwhiti region showed that more than half the population are of Māori descent, increasing from 51.6 per cent in 2018 to 56 per cent in 2023.

A growing and more affordable trend nowadays for shareholders is to apply to the ML Court for a ‘licence to occupy’. This mechanism is generally a more cost-effective exercise than a full-blown ML partition survey.

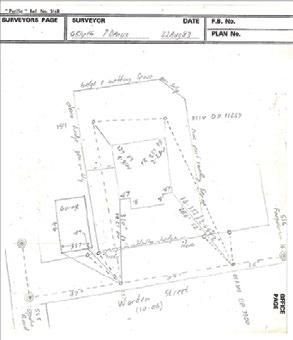

A site plan showing an area within a ML block in which one or more of the shareholders within that ML block wish to occupy is prepared by a licensed cadastral surveyor in order to support an application for a ‘licence to occupy’ to the ML Court. The site plan prepared needs to clearly illustrate the extent of the area to be occupied and should be dimensioned and referenced to adjoining or nearby legal boundaries. The extent of the area to be occupied does not necessarily need to be physically monumented. Some of these ‘licence to occupy’ applications are registered on the Records of Title; however, many are not. This can potentially be an issue for future shareholders who wish to establish an adjoining new ‘licence to occupy’.

Papakāinga housing refers to the development of housing on Māori whenua (land). This provides the ability for Māori to live on their traditional whenua, maintain and enhance their culture and traditions, as well as providing for traditional patterns of housing and use of Māori whenua.

Since Covid-19, many Māori landowners/shareholders have returned home and reconnected with their whānau and whenua. The recent 2023 census for the Tairāwhiti region showed that more than half the population are of Māori descent, increasing from 51.6 per cent in 2018 to 56 per cent in 2023. This is the highest proportion nationally. This has therefore further increased the demand for housing in this region.

There are several successful Māori lead initiatives in place locally and nationally which are providing pathways for eligible applicants into papakāinga and other housing.

In most cases my professional surveying services are required to set out the positions for any new houses (generally relocatable houses) on Māori-owned land, some of which are within pre-determined designed ‘licence to

occupy’ areas, based on approved building consents. Most areas for papakāinga housing in the Tairāwhiti Region are generally in rural areas.

In other cases, I can often be involved in consultation during the early stages, most often directly with shareholders in the Māori blocks, or representatives of their incorporations.

We are currently working with a client who is clearly having difficulty interpreting the rule requirements of the local territorial authority’s District Plan for papakāinga housing. Their organisation may still be required to obtain ‘land use’ and other consents under the RMA. Although it is possible that, in this instance, the need for ‘land use’ consent can likely be avoided, it is critical that the proposed layout for the papakāinga housing is carefully planned.

A little used but important provision allowed for in the TTWMA, is for the setting aside of land as Māori reservation for communal purposes. Section 338(1) of the TTWMA allows the ML Court to make an order to set apart as Māori reservation any Māori freehold land, or any general land, for a number of purposes. These include the more common communal purposes such as for marae and burial grounds (urupa) or a waahi tapu site that has special significance to tikanga Māori.

As with partition surveys, an application needs to be compiled and lodged with the ML Court for consideration before a Court Order can be issued. These surveys are generally depicted as non-primary parcels on a digital survey plan and are not required to be monumented in accordance with the Cadastral Survey Rules 2021. They are carried out in terms of Rule 6 of the ‘Interim Guideline to Aspects of Survey Requirements Applicable to Māori Land Surveys’, dated 24 January 2014. These non-primary parcels are usually given a unique name such as Parihimanihi Urupa Reservation, as shown in Figure 4.

I am currently dealing with another situation whereby various buildings located on a marae have been constructed over the legal boundary with an adjoining Māori block. As the encroachment in this case is significant, I have

suggested the mechanism described above as an option to protect their assets that lie within the adjoining Māori block. This particular application is yet to be considered and authorised by the ML Court.

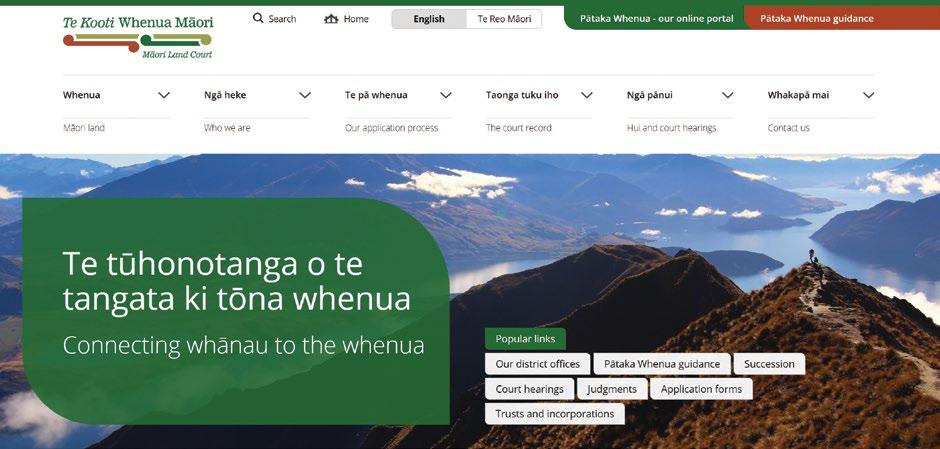

Pātaka Whenua is the new online portal that provides the ability to search and access electronic records for ML information, minutes and orders. It is also used by clients to lodge their own applications including ML Partitions and Occupation Orders.

Like most new systems, the changes with the recent implementation of the new ML computer system have come with challenges that have unfortunately created a backlog. However, moving forward, this new Māori Online Portal will hopefully become a useful resource for anybody involved with ML surveys.

Pātaka Whenua online portal will enable registered users to create and submit applications online, pay submission fees, track and receive notifications on those

applications. In addition, registered users can submit inquiries and request information on ML Court records such as Partition Orders.

There are other aspects relating to the surveying of Māori land that have not been covered in this article. However, it is clear that undertaking ML surveys are somewhat unique but similar to, or the same, as other types of cadastral surveys.

The vast majority of Māori-owned land is held in multiple ownership. Consequently, the ML Court was set up in the mid-1800s to oversee the jurisdiction to determine and record titles of Māori customary land. The ML Court is Aotearoa New Zealand’s oldest and longest established specialist court. It is a unique institution and the only indigenous land court in the world.

In my view there are aspects of undertaking ML surveys that could be improved on. For example, ‘licence to occupy’ areas should be captured and depicted on survey plans and recorded on the appropriate Records of Title. However, there are also the implications of additional costs of undertaking such measures.

Computed CSD plans prepared between September 2006 and May 2010 to effectively allow for unsurveyed partition boundaries to be depicted and shown on Landonline have caused numerous problems and confusion for both Māori shareholders and local surveyors.

The majority of the Tairāwhiti region still has a considerable area that is held in Māori ownership. Since Covid-19 and Cyclone Gabrielle, there has been an increase in Māori returning home and reconnecting with their whānau and whenua. As a result, we are going through an interesting time with an uptake in the development of Māori land and undertaking related ML surveys. •

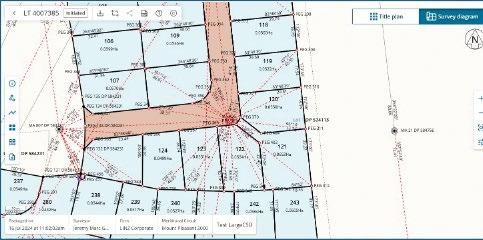

Anselm Haanen, Surveyor-General

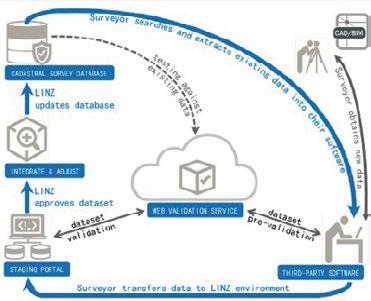

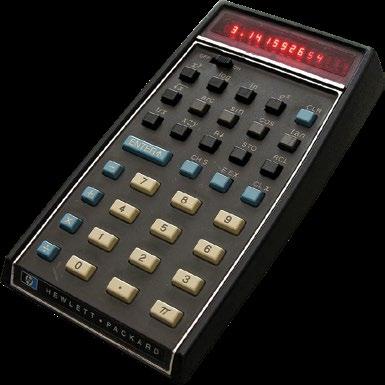

Digitisation has been the major driver in the recent evolution of New Zealand’s cadastral survey system and surveying practices. This article traces the development of the digital cadastral system, from the early introduction of digitally mapping the cadastre through to digital cadastral survey datasets. Highlighting key milestones, such as the implementation of the Landonline system in the early 2000s and mandatory eSurvey lodgement.

We explore the benefits of digitisation, including increased accuracy and efficiency of cadastral surveys, as well as the ready accessibility of spatially accurate cadastral information. And look to the future and further opportunities for digitisation of the cadastral system and its supply chain.

Lands and Survey Department offices in each land district had been maintaining thousands of record maps by adding new parcels and recording the location of new survey plans.

The first major step towards digitising the cadastre was the digitisation of these hard copy record maps in the 1980s. These were hand-digitised to create a seamless parcel fabric for reach land district, based on the new NZ Map Grid projection. By the time the Digital Cadastral Database (DCDB) was completed in 1996, all maintenance was being undertaken digitally and the record maps were decommissioned.

Copies of the DCDB were used by councils and utility companies which had typically been recording the loca-

tion of utility assets in relation to parcel boundaries on their copies of the record maps. The DCDB was also used by government agencies and some private sector organisations, although this was constrained by its cost – about $300,000 for the national dataset – and strict licensing arrangements.

The spatial accuracy of the parcels in the fabric was primarily determined by the scale of the record maps from which the parcels were captured. Users soon reported that the parcel fabric was not well aligned with physical features when overlaid with aerial imagery. Differences of 20m to 50m were not uncommon in rural areas, while in urban areas, differences of greater than 1m were also common. It was (and still is) difficult to explain to users that their property, which appears to be occupied

by a neighbour was most likely not correct due to inaccurate mapping – especially when in some cases the mapping was actually correct!

Inaccurate mapping of the parcel boundaries or occupation over the boundaries?

With the establishment of Land Information NZ in 1996 came the government mandate to automate the survey and title system. This new system, which became known as Landonline, consisted of a single national seamless database built by progressively adding data from each land district. This started with Otago in the year 2000 and consisted of:

Loading the DCDB, including its transformation to the new New Zealand Geodetic Datum 2000.

Scanning the microfilms of 1.2 million survey plans as well as some of the original colour plans.

Capturing current boundary data from the digital survey plans, as well as connections to fifth-order geodetic control marks, many of which had been surveyed specifically to support the project. Data was captured for 1.4 million parcels, mainly in urban areas.

Adjusting the captured data against the survey control network to generate survey-accurate (SDC) coordinates and an associated order.

In the captured areas, the parcel fabric effectively became spatially accurate to the benefit of GIS applications. However, the primary justification for capturing the survey data and generating survey-accurate coordinates was to enable the validation of new cadastral survey datasets, by comparing their bearings and distances with the vectors and coordinates recorded in the cadastre.

A major benefit of this digitisation of the system was that surveyors were able to access survey information and plans from their offices and not have to visit LINZ’s offices. Other benefits included better ability for LINZ to manage the work and its allocation to staff, improved processing times, enhanced IT resilience and disaster recovery, and reduced physical space required for storage and offices.

A core purpose of the original Landonline programme was to enable the lodgement of digital cadastral survey datasets. Landonline was built with functionality for surveyors to capture survey data as an eSurvey along with associated functionality to generate a ‘fixed image’ survey plan from the captured data.

This strategic goal was embedded in the 2002 Cadastral Survey Act which refers to ‘cadastral survey dataset’ (CSD) rather than ‘survey plan’. However, the Rules for Cadastral Survey at that time, as well as the 2010 Rules, continued to require surveyors to produce a survey plan. While this is still used today as the authoritative record of the survey, the Rules have also included requirements for the CSD to include most of the data in digital form which is integrated into the digital cadastre once approved. While Landonline included functionality for capturing the data required in the CSD, surveyors were increasingly

utilising digital technologies in the field and had been using survey software to undertake their calculations since the 1980s. LINZ joined in the development of the fledgling LandXML to include cadastral data to enable that data to be digitally transferred into the eSurvey. With the support of survey software vendors, surveyors were able to export most of the data from their survey package and load it into Landonline, saving the manual entry of that data. Missing elements were able to be added using the Landonline application. Once most surveyors were using the eSurvey capability, LINZ made digital lodgement of 2D CSDs mandatory in 2007.

The digitisation of the preparation and lodgement of CSDs drove efficiency and quality into the supply chain. Surveyors were able to validate their CSDs using the Landonline business rules, as were LINZ validation staff prior to approving the CSD.

Landonline was specifically designed to test new CSDs against those already digitally recorded. When the underlying record is already ‘survey accurate’ such as that resulting from an eSurvey, this significantly improves the confidence of the tests and reduces the validation effort.

However where the underlying data is poor, and particularly where that data was only derived from the original DCDB capture, the testing of new CSDs against that record has limited value. Surveyors were also able to download LandXML data from Landonline as a starting point for a new cadastral survey. With the data in the cadastre becoming increasingly ‘survey accurate’, this enabled survey marks to be more easily located in the field, particularly using GNSS positioning technology, and also enabled survey-

ors to undertake ‘pre-calcs’ to expedite the field work before leaving the office.

Successive Rules have increasingly required surveys to connect to the cadastral survey network, being marks of order 6 and higher. As a result, virtually all modern CSDs produce ‘survey-accurate’ coordinates once they are integrated into the network following approval. This process, using least squares adjustment, means that most new boundaries in the parcel fabric are also survey accurate. This is particularly beneficial in rural areas where the parcel fabric is relatively inaccurate. Not only does this improve the accuracy of the new parcels, but also improves the accuracy of the surrounding parcels which are included in the adjustment.

Prior to digitisation, if people wanted to locate a cadastral boundary, they would have to either find the boundary marks or engage a surveyor to physically mark the boundary. That field survey might be marked up on a suitable diagram or aerial image.

Nowadays, and increasingly in the future, existing boundaries can be located to varying degrees of accuracy using the digital representation of the parcel fabric. With datasets all being referenced to the same official national datum, the parcel boundaries can be easily overlaid with aerial imagery to illustrate the relationship between the legal boundary and occupation. For many uses, that level of accuracy is sufficient.

Similarly, SLAM (Simultaneous Location and Mapping) technology can enable a non-expert user to establish their position in relation to a road boundary or parcel on the ground. This combines GNSS positioning technology, now available on mobile phones and in vehicles, with the coordinated positions of boundaries from Landonline to place that ‘blue dot’ against the

Duplication of a CSD information presentation.

The benefits of an accurate parcel fabric are exemplified in the extensive work that the NZ Transport Agency has commissioned to capture cadastral survey data to improve the accuracy of boundaries around highways. When these parcels are overlaid with other spatial information, users are able to confidently relate the physical road with the legal road as well as determine the relationships between the roads and surrounding parcels.

The current regime still requires surveyors to submit a fixed image ‘survey plan’. That plan does not provide the benefits obtained through digital processes, as indicated above. The parallel representation of the information in digital form seems an unnecessary duplication of effort and data.

The current LINZ proposal to move to Digitally Visualised Survey Plans is aligned with the broader goal of having fully digital cadastral datasets submitted by surveyors, as envisioned in the 2002 Cadastral Survey Act. Under this regime, the rendering of the dataset into a form that is interpretable by the user would be provided by software without intervention or effort by the surveyor. This shift would mean surveyors would no longer be responsible for generating the plans and this requirement would shift to LINZ. Surveyors would however be responsible for the provision of the digital datasets which would be the authoritative record in the cadastre. Before this new approach is implemented, further work will be undertaken to prove it works for all parties and uses, and particularly to ensure that the digital CSDs certified by the surveyor persist forever in the cadastre. This regime will likely see

A Digitally Visualised Survey Plan. digital map.

the visualisation of the survey aspects of the CSD (the survey plan) sharply focused on surveyors’ needs. Having the rich dataset in digital form will provide the opportunity to develop products customised to meet the needs of specific other users, especially solicitors and Territorial Authorities who require the equivalent of the Title Plan. Property owners, real estate agents, architects, engineers and other users could also have products tailored for their particular applications, incorporating other information such as ownership, registered interests and aerial imagery.

Having the CSD in digital form enables further improvements to be made in the quality of the cadastre and the efficiency of its processes. Ideally the business rules would be more granular than those currently in Landonline and be presented through web-based services (including APIs) so that surveyors could validate their CSD directly from their survey software and from Landonline before certification, while LINZ would use the same tests as part of its validation prior to CSD approval. Ultimately any resultant improvements in the quality of lodged data should enable improved LINZ approval times, particularly for non-complex surveys.

Validation in the digital cadastral survey data cycle.

While New Zealand has been remarkably successful in digitising surveys recorded in the horizontal, significant work is required to make progress on digitising CSDs and the cadastre in the third dimension. Even though much of the process is increasingly completed using digital processes, CSDs of Unit Titles and Strata Surveys continue to be presented only as survey plans with very little digital representation of the height data.

One of the foundations for digitising 3D surveys has been laid with the 2024 amendment to the Rules that requires all heights in CSDs be in terms of the national height datum, NZ Vertical Datum 2016. Use of this datum is a prerequisite to digitally recording 3D CSDs in the cadastre, which would be unable to manage the representation of digital CSDs expressed in terms of different height datums (such as the previous Local Vertical Datums).

Foundational work has also been completed to model how 2D and 3D digital cadastral data can be represented and exchanged between survey software and land administration agencies throughout Australia and New Zealand. This new regime is likely to use JSON as the mechanism for transferring cadastral survey data, including 3D elements that LandXML cannot currently support.

If the current proposals for digitally visualised survey plans is implemented and proven, LINZ will be looking to enable surveyors to also lodge digital 3D CSDs. Those CSDs will also need to be integrated into the parcel fabric and be suitably visualised using enhanced CSD viewer capability.

Like digital 2D CSDs, digital 3D CSDs will offer significant benefits of efficiency and accuracy to the

cadastral survey system. Surveyors would be able to prepare the 3D CSD in their software and submit it to LINZ. It is unlikely that Landonline would include capture capability for 3D. The CSD would be able to be validated for polyhedron closure, 3D overlaps, fit with the underlying parcel, etc.

It is also likely that Unit Title and strata parcels already recorded in the cadastre would need to be digitally back-captured to fully populate the 3D parcel fabric.

In a similar manner to the way that the 2D parcel fabric is overlain with aerial imagery, in the future 3D parcels would be able to be ‘overlain’ with 3D representation of the physical environment, including basic landforms, buildings and utilities.

This overview underscores the importance of continuous innovation in maintaining a robust and reliable cadastral infrastructure for New Zealand. Digitisation and the associated automation have yielded major benefits to the overall cadastral system and its users. Further significant opportunities and benefits remain to be realised.

The technologies that now pervade the survey supply chain will inevitably lead to fully digitally CSDs, their automatic rendering as visualised plans, and the generation of multiple plan and data products tailored for specific user groups.

While the technology to enable the 3D cadastre already exists, significant work is required to ensure that the future solutions are robust and enduring, and consistent with the 2D solutions.

There will be increasing demand for the cadastre and its parcel fabric to more accurately reflect the extents of rights and interests, including roads, to be able to respond to future needs including climate change. •

Richard Hemi, Senior Professional Practice Fellow, School of Surveying | Te Kura Kairuri

The teaching of cadastral studies has inevitably evolved and been updated as new technologies, new digital tools and new practice methods have become commonplace. However, the learning of the ‘art’ that is good boundary definition still remains, and must continue to be an integral part of any teaching in cadastral studies. The final-year student cadastral project has been an important part of the Bachelor of Surveying programme for more than 50 years and has been one of the main sources of definition practice.

Changes have recently taken place in the School of Surveying bachelor of surveying degree course curriculum and specifically in the papers concerning cadastral studies. In 2023, a revised curriculum began for the new intake of first year students, with a new paper –SURV130 People, Place and the Built environment. Part of this curriculum change is a reconfiguration of cadastral and land tenure papers with the introductory cadastral paper SURV207 being removed, but with the bulk of its content being placed in other existing papers. This leaves SURV307 and SURV457 as dedicated cadastral papers but with the co-requisite of land tenure papers SURV206 and SURV306

alongside them. While SURV457 is not a compulsory paper, it remains a requirement of the CSLB and by default, a very popular paper with almost all BSurv students taking it. The cadastral dataset project is a significant part of the final-year paper where students, working in pairs, carry out a full survey project from start to finish. This aligns with the School’s teaching strategy to allow final-year students greater freedom and ownership of larger, self-driven project work. In this case, students must manage their own time to deliver a completed CSD, having gone through the entire process, both in the field and office. Comments submitted by students in their final reports often talk about how the project brings together different skills learnt at the School, and of being very challenging

but enjoyable. The benefit and satisfaction of having been given free rein over the whole CSD is also a common reflection.

Allan Blaikie first created the project in his teaching of cadastral papers c.1970. He felt the course was very light on cadastral studies at that time particularly from the point of view of practical work, and there was no cadastral content in the field camps. While the full process of the survey was largely the same as it is now – searching, field survey, computations and plans – things were very different in terms of technology. In those early days, students would have to walk down to the Exchange in central Dunedin to request manual copies of plans and titles from the local offices of Lands and Survey, and DLR. Students were typically required to find an

appropriate property for a redefinition survey, most commonly their own flat, and this would be approved by Mr Blaikie if the site was considered to have a reasonable degree of difficulty.

When I took over the teaching of this paper from Don McKinnon, Survey School staff were finding the project sites for the class and allocating them to student pairs. Don had various groups from which he sourced these properties, such as the staff of different departments within the university. This essentially resulted in real clients and real sites scattered far and wide around Ōtepoti/Dunedin, and sometimes well beyond to Waihola, Karitane etc. However, one of the weaknesses of using such a mixture of properties was the variation in difficulty. Some were relatively easy, while others ranged up to very difficult because of limited titles, conflicts or encroachments. This did however provide a number of very good case study examples, some of which are now used in lecture notes and class tutorials. Dunedin is still a good provider of complex cadastral situations.

In the early 2000s, LINZ worked closely with the School to enable student use of Landonline and so began a new era of cadastral teaching. Don McKinnon created a range of new teaching material to support the use of Landonline, and now, by the time

A very tidy field note diagram from a 1983 student redefinition survey in Opoho.

students reach their final-year paper they are capable of creating complete CSDs in the system. LINZ has continued to support the School during the recent transition to the new and upgraded Landonline platform.

One of the benefits, or challenges, of giving students freedom and responsibility out in the real streets and neighbourhoods of Ōtepoti/Dunedin is their encounters with neighbours and members of the public. This can lead to positive outcomes in the development of their professional communication skills, such as dealing with questions about what they are doing and why. However, there is still the possibility of staff receiving an irate phone call from an unhappy neighbour regarding a trimmed hedge, or an unhappy dog etc, both of which I have received. In the most part, students learn to communicate and negotiate some real life situations, hopefully increasing their confidence and better preparing them for future professional work. Other teaching outcomes, which are not specifically technical cadastral ones, can also be gained from the project, such as time and project management skills and teamwork. The project demands a good amount of CSD supporting documentation, survey reporting and personal reports, and students often find this takes much longer than many initially anticipate. In 2020, the Waka Kotahi – NZTA requirements for obtaining an STMS traffic management qualification were

revised and it became particularly difficult and expensive to obtain, and as a result, it was decided that this could not be expected of students. Up until this point, at least one of the student pair needed to obtain this senior traffic qualification to prepare the traffic management plan and supervise its installation on site. This allowed students to undertake survey work on roads without staff supervision and in their own time. This change became the main catalyst in 2021 for moving the project from individual boundary reinstatement surveys to nominated Dunedin parks and undertaking a full LT subdivision. Currently seven parks are used in and around Ōtepoti with 30plus different scheme plans, and each with an associated resource consent ensuring that all student groups end up with independent surveys. One of the benefits of undertaking a subdivision is putting into practice prior teaching about the subdivision process with students needing to address the conditions of their consent and requesting a theoretical S.223 approval. Furthermore, all of the CSDs now include secondary parcels in the form of proposed easements or covenant areas. Other benefits for school staff in using these parks include the ability to return each year to the same site and data, and not have to find 30 fresh sites each year. As it turns out, the parks we have chosen also tend to have a good number of ‘findable’ buried marks. From this, students learn to go

through a process of firstly identifying these marks from the old survey plans (as many are pre-Landonline traverse marks and not available in a data extraction file), plan their traverse in order to connect to these marks and then use them effectively in their definition. While many of the earlier redefinition sites may have been considered to be harder, being limited titles or old deed parcels, they often didn’t have old ‘witness’ or old pegs to find and relied heavily on standard survey offsets and calculations. I really believe at this level of study that digging up old marks and using them in a definition, and possibly also in bearing correction calculations, is a critical practical skill that we want young surveyors to learn, and does not change even as new technologies and data availability make other elements of the survey easier.

Technological advances since the 1970s, such as GNSS and robotic total stations, have certainly changed the survey methods used. GNSS is particularly important for these projects

An example of a 2-lot subdivision dataset from the SURV457 class of 2023, located at St Leonards Park.

given the sites are typically larger and require connection to survey control that can be some distance away. However, all surveys must use both forms of instruments and students are typically required to ‘peg’ boundaries using total station. This reinforces the teaching of methods to ensure consistent orientation to all vectors, and good survey practice around backsights etc. But what of the next changes? The likely shift by LINZ to digitally visualised survey plans will reduce the overall workload of the project (as it may do for practising surveyors) but it may also hinder some student learning. While many may believe this is a good thing, the plan draughting process can be a useful learning step in understanding good survey capture and compliance of cadastral data.

The advancements in data access and visualisation tools also raise the question as to how modern surveyors will approach a new cadastral survey. Pre-calculations or downloaded coordinate data are very useful in the field but can an over-reliance on pre-determined positions create the potential to undermine the accurate determination of boundaries? How do we adjust the placement of pegs on an existing boundary if I find the old pegs are in a slightly different but possibly acceptable, position? By the time students reach SURV457 they have learnt to pre-calc field data and have

practised using this to locate marks and take initial observations, typically with GNSS. It can therefore be tempting for trainee surveyors to rely on predetermined coordinates for boundary definition above old marks as found in the field. This is a particularly important for the School of Surveying as we attempt to instil best-practice survey habits into undergraduate surveyors, and to continue to demand that surveyors ‘follow in the footsteps’. The final-year cadastral student dataset has remained a significant capstone project for more than 50 years and continues to stand the test of time. Modifications have inevitably been required in light of changes in equipment, digital data and even health and safety requirements, but I am sure my former teachers, mentors and colleagues would agree that best survey practice and correct boundary definition must remain at the core of cadastral teaching. •

I wish to express my gratitude to Allan Blaikie and Don McKinnon for their assistance in writing this article. I also wish to remember a good friend and classmate, Trevor Gerrish, who worked at the School and briefly taught cadastral studies, but sadly passed away in 2001 at the age of 35.

Rita Clark and Andrew Blackman S+SNZ Cadastral Stream Executive Members

The Cadastral Survey of the Year Award was first awarded in 2015. After a hiatus, it was revived in 2021 and has been awarded every year since. One reason for this renewed enthusiasm is the growing success of the awards night held at the S+SNZ annual conference. This event has increasingly become a highly anticipated part of the conference, drawing attention not only to the awards, but also to the broader achievements being celebrated within the surveying and spatial community. As a result, we believe the prestige of the cadastral award has been amplified, attracting more attention and participation in recent years.

As evidenced by beautiful, old coloured survey plans, cadastral surveying is really an art, and a qual-

ity survey plan is a thing of beauty.

The Cadastral Survey of the Year Award was created to celebrate excellence in cadastral surveying, recognising those that go above and beyond. There is much discussion of requisitions and problems with cadastral surveys, so it is great to see and to celebrate excellence. By highlighting successes, the award not only acknowledges those who contribute positively, but also inspires others to strive for similar levels of achievement.

In recent years, there has been a healthy number of entries

for the award, with five strong submissions in each of the past two years. The quality of these entries has been consistently high, showcasing impressive work and raising the bar for the competition. This increase in both the number and calibre of submissions has presented a unique challenge for the judges, who have had to make difficult decisions in selecting a winner. However, this is a positive sign, as it reflects the quality of cadastral surveys being completed and also the growing interest in the recognition of excellence within cadastral surveying.

Judging will always involve a certain level of subjectivity, however, with experience, judges develop an instinctive sense of

what constitutes exceptional work. To ensure fairness and balance in the evaluation, multiple judges are involved, bringing diverse viewpoints to the table. This balance has been further enhanced in the past two years by the inclusion of some additional well-respected surveyors as guest judges. Their experience and knowledge of cadastral surveying have given a welcome boost to the judging panel.

In recent years, the award has been proudly sponsored by the surveyor-general, a significant

endorsement that underscores the importance and prestige of the award. This sponsorship is a clear indication of the high regard in which the surveyor-general holds the award and its role in promoting excellence within the field. The sponsorship not only enhances the award's visibility, but also solidifies its standing as an important and respected accolade in the surveying and spatial calendar. We are hopeful that the current trend of strong participation continues in

the coming years, with a healthy number of entries that maintain the high standard we've seen recently. It’s always rewarding to showcase some of the excellent work being done across the country, offering well-deserved recognition to those who are making significant contributions. By highlighting these successes, we aim not only to celebrate individual achievements, but to inspire others to pursue similar levels of excellence. The visibility that this award provides

encourages a culture of continuous improvement, where more professionals feel motivated to innovate and push the boundaries of what is possible.

The winner of this year’s award was Mark Geddes, of TL Survey Services in Dunedin, for the Blueskin Road Legalisation Survey – SO 571293. This was a unique road legalisation survey which discovered numerous conflicts with approved plans and the gathering of evidence unearthed answers hidden for decades.

Mark has provided his own perspective on the award and tells us what drives him to strive for excellence in his work:

Why enter and what is the benefit?

Recently, I was asked why I submitted an entry for the Cadastral Survey of the Year Award. However, it wasn’t the first time I had submitted an entry. I entered in 2015 and

while I wasn’t placed, I was asked to present the survey as a guest lecture for final-year survey school students. Also, I was asked to write an article for the Survey Quarterly. I submitted another survey in 2023 and won the silver award and also presented that survey at a workshop.

Since winning the award this year, we have had our company on the front page of the Otago Daily Times.

I have also written a piece for a local real estate newsletter, been asked to do an educational presentation on surveying to another group of real estate agents and have been asked to write two further items for publications. There is also the opportunity to advise your clients through newsletters and social media. The benefits are obvious! It provides additional exposure for cadastral surveying and, from a business perspective, it is the closest thing to free marketing that we have experienced.

So, how can you enhance your chances in such a competition? Well, the difficult surveys don’t come through the door every day, but something with a point of difference in terms of the scope of the job or one that uses different techniques or unusual forms of evidence is a good place to start. It never hurts to look into the little things too, such as the good survey practice elements. This is not something that has a single definition, but it is the surveying

equivalent of the Force in Star Wars! That power for good which only enhances the final outcomes. Lastly, training. Graduates do a lot of the fieldwork in many firms and often by themselves these days. People so often learn from older experienced people, so don’t succumb to the pattern of sending new graduates out by themselves in the early weeks and months of their training. Too much evidence is missed, and opportunities are squandered if young surveyors don’t keep their eyes open, or know what to look for.

The requirements for submissions for the award aren’t arduous. Many of the documents required will have already been prepared as part of your dataset. An additional report (that follows the awards brief) is required but this is also beneficial for refreshing the finer points of the job that can become lost with the passage of time, as well as reminding yourself about options that might exist for jobs currently on your desk.

So, to summarise, a lot can be gained from entering your best work, or being placed in the Cadastral Survey of the Year Award, but ultimately everyone wins. To enter, you will undoubtedly be proud of your own submission and the quality of it, which means that we as surveyors, and also the public, benefit from the quality of your contribution to our collective cadastre. •

Mark Geddes, Manager and Licensed Cadastral Surveyor, TL Survey Services

Large rural limited titles aren’t unusual for our firm, and miscloses in the metres or definition issues are no strangers in our land district, but this job was born out of a limited title that struck more unusual issues than what we consider the norm.

LT 540170 is the ‘sister-plan’ to SO 571293 and a comprehensive data-search and subsequent calculations in the early stages of the limited titles subdivision showed numerous anomalies. The plot thickened when we commenced the fieldwork. All of this lay on part of a scenic road between Port Chalmers, Dunedin, and what is

now the Orokonui Ecosanctuary, from near the Scott Memorial to Reynoldstown Road.

After much investigation and correspondence with Toitū Te Whenua/LINZ, it was concluded that the land that the road formation was on from as early as the 1860s was in private ownership and the plan that showed the ‘road corridor’ first was not deemed to have been legalised as it had neither a licensed surveyor or chief surveyor’s signature. No additional legalisation notes were present on the plan for this specific corridor either. This meant that the land parcels

in our limited titles plan had no legal frontage, which was an issue for the resource consent process. In addition, there was conflicting information about the width of the corridor that earlier surveyors had shown abutting their plans. This appeared to be an issue but later conclusions lessened the need for a definitive interpretation of the road width.

Occupation on plans and occupation diagrams suggested that while fencelines had been the defining points of the first definition in the area, other plans missed occupational clues. Or at least that is what our first day of fieldwork showed. All too frequently older vegetation is not considered occupation. It was a mere tree stump that first got us questioning the quality of some of the definitions but that was only one piece of a much bigger occupational pattern that became apparent in the blocks surrounding the subject parcels in both our legalisation and limited titles surveys.

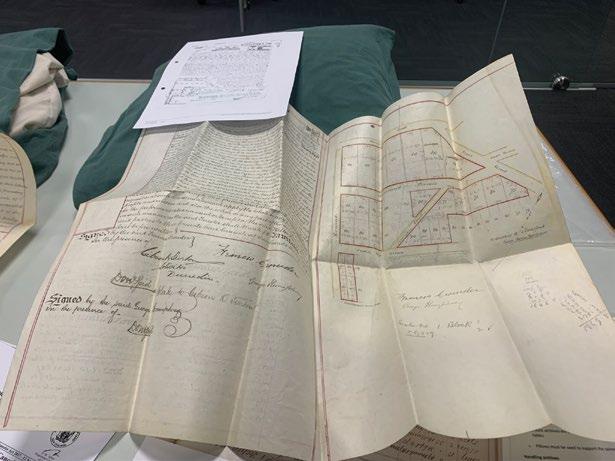

The initial research into the legality of the road corridor was detailed in terms of researching old plans, titles and deeds. The search that subsequently took place to determine the current ownership of those same parcels of land was even more detailed. The determination of who owned the land had an influence on what legal processes could be used

for certain parcels.

The Deeds Index is a system that is quite different to the Land Transfer system and searching it is somewhat of an art. Fortunately, our senior surveyor, who trained under Lands and Survey and DOSLI, had a working knowledge of the system that went beyond what the rest of us usually search for at Archives NZ.

What we also needed to prove was that the land hadn’t been sold or transferred to the Crown for roading purposes or other purposes. Our searches started bringing up deeds references, appellations and names of interest but following the clues to unpick the metaphorical lock with the quality of the documents we had was difficult.

A number of leads were not fruitful but two names that we had come upon appeared to hold the key.

William Mansford and Francis Crowder were individuals that we looked into further. Mansford emigrated to New Zealand in 1862 from England and was the owner of the Crown Grant for the area around Port Chalmers. We had confirmation of his ownership. We also had deeds showing Crowder as an owner but what appeared to be missing was the link, or links, between Mansford’s ownership and Crowder. When we thought we had exhausted our leads, we had a conversation about the applications

that happened under the deeds system that recorded the transfers. These could be additional documents that held clues, if they still existed.

We mentioned this to the staff member at the counter and while we were having that conversation, another staff member came up and overheard our comments about applications and said there was a box of old documents in the back room that had been found when the furniture had been moved and the walls were exposed in the decrepit, old Otago Early Settlers’ Museum when it was being renovated to become Toitū Otago Settlers Museum.

Five minutes later after, noting the details we provided, he returned with the very deed that showed the first transfer from Mansford to Crowder of part of the Crown Grant land. This was a breakthrough and later went on to prove that the land was still technically in private ownership and much of it held in deceased estates.

The survey definition was also influenced by historical titles that had their origins in the deeds. Toitū Te Whenua/ LINZ did not want any titles completely extinguished by a new legal road corridor and given the location of the road formation relative to those titles, any road taking would be on the eastern side of the road. This was complicated by a relatively recent survey to the east that had caught our

attention earlier.

Our approach seemed simple but differed from those other surveys since the occupation-based definition of 1967. They had all taken their survey origins from plans that relied on the 1967 plan. That plan resected to local trigs to bring in bearing control, so the traverse bearings were sound but the boundary bearings were determined from fencing and were shown as +26’.

This larger-than-normal bearing correction raised our interest as other surveys in the area were only finding +1’ to +1’30” corrections to old cadastral work. Of particular interest was a comparison we found with an old fenceline across Blueskin Rd from the survey that made the +26’ correction. We found the comparison to be -26’ from that fenceline, a difference of 52’ of arc. We came off an independent origin and also looked for other historical marks that the others hadn’t found or even searched for.

We had success in our search and found an 1884 stone peg from SO 14752 on a critical boundary line and also an iron bolt from 1895 on the perpendicular intersection of the old section boundary. The stone peg and bolt were also on the same alignment and helped anchor our definition to the south and through the old bolt, to the north as well. We used both GNSS and conventional theodolite methods

to connect these marks to those marks from the newer surveys to the north-east of the formation that was subject to our legalisation survey.

This ‘whole to the part’ control connection gave us the opportunity to make comparisons and connections to other surveys we had undertaken in the wider area that had also picked up old occupation. It also gave us the ability to further test approved survey definitions that we were questioning. When looking further afield for evidence, we stumbled across DP 1058 in Sawyers Bay that the surveyor had tied to an old fenceline on the Sec 4/5 boundary Block II Lower Harbour West SD. The long-time owner of the land had also showed us a ridge in one of his paddocks where he had removed this fence some years prior.

When the ties to this ridge were compared with the old bolt position on the southern boundary, we had very good agreement.

Our calculations showed that differences of more than 4 metres existed between the positions we determined from the historical marks that we’d found to the newer plan to the east across the road formation. We approached Toitū Te Whenua/LINZ about our concerns and we were told that the need for compelling evidence to prove a survey error was relevant in this case. The Crown’s current definition of compelling evidence has

its roots in the Hosjaard v LINZ 2019 Court of Appeal case where the judge stated that compelling evidence is required to prove a survey error. It was the role of the surveyor-general to determine what met the threshold of compelling evidence.

Toitū Te Whenua/LINZ staff said that in our case because neither the other survey or ourselves found the specific boundary pegs in question that compelling evidence of an error wasn’t present. While we were not comfortable with this approach, we had to accept it and went into further discussions on the best approach to create a legal road corridor while respecting recent definitions.

We continued with the fieldwork and this too was difficult given the terrain. The corridor has a steep drop-off to one side and a steep bank on the other. There were significant health and safety concerns and we were granted the right to peg one side only. We used repeated passes with a vehicle-mounted GNSS receiver to measure the generalised centrelines of the lanes on the formation. On the uphill side, we still had to cut lines for the pegging.

Shortly after we had pegged the job, our clients, Dunedin City Council, changed its Crown-accredited agent and with that came a different approach to the way the legal actions at the end of the process would be

undertaken. Initially, it was going to be entirely under the Public Works Act but this changed to the Government Roading Powers Act 1989 where the principle of implied dedication would be employed for the land in the deceased estates and a single Public Works Act action would take place for the one parcel of land that would lose area that had a live owner. The implied dedication based on the formation influenced the road width and the peg positions compared with the previous approach and hence we had to return to the site to peg the new scheme. Our evidence-finding exercise widened and soon we were looking at other surveys of ours in the Careys Bay area to see if any old occupation matched our other findings. Sure enough, there was a close compar-

ison with the old occupation found on the northern side of the original deeds plan that laid down Careys Bay. A fortuitous boundary identification exercise for another client also provided us with another piece of this same fenceline.

When the alignment of these isolated portions of fence were compared, there was a remarkable agreement with our developing definition theory. It even became apparent that the original deeds plan may have been incorrectly defined in the first instance! Older surveys found old pegs from Deeds Plan 57 that were offset from the framework set by Crown surveys on the SE boundary of Block II Lower Harbour West SD. This revelation fits well with the old fence on the

north-west boundary that we have found. It became a case of ‘the more you look, the more you find’. All of this began with our original fieldwork that found an old stump with some wire through it that didn’t fit with recent surveys – the same surveys that said that there was no occupation. Additionally, our work with the historical deeds also proved Landonline to be incorrectly showing a portion of road to be closed immediately to the north of our LT survey that connected to the parcels we were in the process of legalising. This has since been corrected.

As for what the status of the road is at this point in time, the application for legalisation of part of Blueskin Road has been submitted to the Ministry of Transport for consideration under section 43(1) of the Government Roading Powers Act 1989. Ironically, of the eight surveys we thought were out of position, the earliest was at Deeds Plan 57 and was signed by a man named Mansford. The lock had been unpicked and shortly, the road will be a road in all senses of the word. It’s amazing how many poorly defined parcels of land exist so close to a major city like Dunedin. As the population grows, developers will look more and more to these areas. We, as surveyors, need to keep our eyes open and look for those telling clues that may help to unpick the next lock. •

Last year the Board farewelled some long-serving members and welcomed a few new faces to the table. The present Board comprises Neale Faulkner (returning Chair), Anselm Haanen (Surveyor-General), Craig McInnes (returning), Clare Tolan (new), Laura Coll McLaughlin (new), and Pengbo Jiang (new lay member). In addition, Colin McElwain was reappointed as substitute member and Sundeep Daggubati appointed as the new lay substitute member. Phil Napper continues to serve as Secretary and is the acting Examinations Coordinator.

The Board has a statutory obligation to maintain the integrity of the cadastre thereby safeguarding the public interest regarding land tenure. To achieve this, the Board follows a rigorous process around licensing and complaints and ensures the high level of competency standards continue. With this in mind, the Board is in the process of developing a new replacement competency assessment framework for applicants seeking an initial annual licence to practise as a cadastral surveyor. This stemmed from

a review of the existing longstanding process by Dr Don Grant, which was followed by a series of workshops with key stakeholders and consultation with the wider profession. As a result, the following framework has been adopted by the Board.

Having a sequential process means graduates will build upon the foundation they obtained at university by getting real-world experience on surveying projects. Once they have an acceptable portfolio of experience to demonstrate their skills, they sit a professional challenge to test what they have learnt. Once they pass this, they progress to a professional interview to confirm their competence.

The Board's current focus is on the new competency assessment framework. The Board appointed Synapsys Ltd as its key partner to implement the new framework. Synapsys is a Wellington-based firm specialising in people and process challenges. Its mission is to bring clarity, certainty

and confidence. Synapsis Ltd has 20 years’ experience across nearly every sector in New Zealand.

There are two key streams of work for the framework where Synapsys is involved. Firstly, the competencies were refined into measurable achievement standards applicable for those seeking a first-time licence. These were then aligned with the appropriate stage of the framework where they could best be assessed.

A User Requirements document has been developed which sets out what each group of people will need from the system.

Secondly, Synapsys is working to deliver the new assessment framework via an online platform. It has recommended a platform called Moodle which is widely recognised and used by a number of organisations and tertiary educators in New Zealand.

The Board regularly publishes updates on the CSLB website around the progress of the assessment framework and other matters.

Candidates and their supervising surveyors are strongly encouraged to

engage with the new process, and candidates should register with the Boards Examinations Coordinator.

The Board receives notifications from the Surveyor-General of significant failures by cadastral surveyors to comply with the standards together with the occasional correction survey. These are seen as a warning sign that a surveyor may not be as diligent in the process of conducting a cadastral survey as they should be and are duly investigated. Subject to the outcome of that investigation, the surveyor’s performance is monitored by the Board for a period of time to ensure that any failures are unlikely

to reoccur. The Board treats these notifications using the analogy of the ‘ambulance at the top of the cliff’ with the view of helping surveyors to recognise their shortcomings and eliminate the possibility of any recurrence.

In addition, the Board receives occasional complaints of professional misconduct, primarily from the Surveyor-General, but also the public and professionals. These are taken very seriously by the Board and often result in a hearing with various consequences which can include supervision by another licensed cadastral surveyor, the suspension of a licence, or in the worst-case scenario, the cancellation of a licence as a last resort.

Often failures result from

poor-quality assurance processes at all stages of the cadastral survey process. It is vitally important that a good quality assurance process is adopted and applied from the commencement of the survey right through to the end when the cadastral survey dataset is lodged with Land Information New Zealand. In this way, the possibility of errors and failures will be minimised and ideally eliminated. A good tool in this regard is to review and learn from all requisitions received from Land Information NZ, together with those from your colleagues. Upon request, Land Information will provide any licensed cadastral surveyor with a summary of requisitions over a period of time which highlights in graphical form specific areas where its requisitions are commonly occurring. First-

ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION

FOUNDATION FOR COMPETENCE

ó Four-year tertiary qualification in surveying from NZ or Australia

ó Equivalent surveying qualification from outside NZ or Australia as assessed by BAOQ

ó Potential for undergraduate degree + additional study approved by CSLB

PORTFOLIO OF EXPERIENCE

DEMONSTRATE COMPETENCE

ó Summary of work experience

ó Documented work projects undertaken aligned with the list of competencies

ó Covering report

ó Signed declaration

ó Attestation from supervising LCS

ó Portfolio to be assessed and accepted by Assessment Panel

PROFESSIONAL CHALLENGES

TEST COMPETENCE

ó Time-bound challenges accessible to applicants held at least once/year

ó Challenges is set, marked, and moderated by Assessment Panel

ó Grounded in real-world scenarios

ó Tests applicant’s abilities, and understanding of competencies, incl. cadastral laws, SG Rules

ó Must be passed

PROFESSIONAL INTERVIEW

CONFIRMS COMPETENCE

ó In person interviews held at least once/ year by Assessment Panel

ó Reviews earlier assessment Panel

ó Reviews earlier assessment stages, confirms applicant is proficient in the competencies

ó Interview Panel covers the competency areas

ó Remedial work may be identified before pass can be granted.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

The number of surveyors renewing their annual licence this year was 726 compared with 723 last year.

The current (October 2024) number of licensed cadastral surveyors is 731.

10% of licensed cadastral surveyors are female.

This year the Board saw a small increase in applications from graduates (31 compared with 29 in 2023).

The vast majority of new licenses issued continue to be to New Zealand survey graduates from the School of Surveying at the University of Otago.

The younger (20-39) age group represents 32% of the total number of licensed cadastral surveyors.

The current oldest licensed cadastral surveyor is 90 years of age and was first granted registration in 1958.

Last year a surveyor, who registered in 1951, decided it was time to ‘hang up the chain’ and not renew his annual licence at the age of 97.

time compliance should always be the goal as it has many benefits.

It is encouraging that the number of significant failure notifications to the Board has reduced over the past three years from 5 per year to 3 per year, as have the number of complaints of professional misconduct, from 3 in 2020 to 1 in 2023.

The Cadastral Survey Act 2002 makes it clear that a licensed cadastral surveyor is responsible for a survey conducted by a person acting under their direction [s47(3)].

In accordance with s73 of the Cadastral Survey Rules 2021, a cadastral survey dataset must be certified by the licensed cadastral surveyor as follows:

I [name], being a licensed cadastral surveyor, certify that— (a) this dataset provided by me and its related survey are accurate, correct, and in accordance with the Cadastral Survey Act 2002 and the Cadastral Survey Rules 2021; and (b) the survey was undertaken by me or under my personal direction. Failure to personally direct the cadastral survey and the related field operations can lead to a complaint of professional misconduct (s1(b), Schedule 2).

A licensed cadastral surveyor is guilty of professional misconduct if the cadastral surveyor is found in any proceedings or appeal under Part 4 to have certified to the accuracy of any cadastral survey or cadastral survey dataset without having personally carried out or directed the cadastral survey and the related field operations.

The Board is aware that with modern survey technology and changes in practice that some surveyors may not be adequately meeting their responsibilities in this regard. Furthermore, the Board has observed that a few licensed cadastral surveyors are certifying a high number of surveys each year, in some cases, this equates to 2-3 per week over a prolonged period of time.

Don Grant (former surveyor-general) published an excellent article entitled ‘Directing and certifying cadastral surveys’ which the Board encourages all licensed cadastral surveyors to read and reflect upon on a regular basis. A copy of this article is available under the ‘About –News and Publications’ tab on the CSLB website. •

Nick Stillwell is Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand’s Sector Engagement Relationship Partner working with surveyors. We asked Nick for his reflections on the development of the new Landonline as the switch-off date for the legacy Landonline looms closer (early 2025).

By Nick Stillwell

In October 2017, I joined the programme to replace Landonline as the representative for surveyors. Back then, it was called ASaTS (Advanced Survey and Title Services), and the team was focused on getting government approval to rebuild the system. The idea behind ASaTS was to buy a land administration service ‘off the shelf’, enhance it and use it to replace Landonline.

I was employed by Survey and Spatial New Zealand and my role was funded by the programme. The world was a different place back then. Microsoft Teams didn’t exist. And working remotely wasn’t really a thing. I was based in Hawke’s Bay but spent my week working in the LINZ office in Wellington.

It was a fascinating change going from working as a surveyor in the private sector, to being embedded in an enormous IT project. I didn’t know which way was up or down for the first few months. Over time I came to terms with the programme cadences and key differences you find working in the public sector. And over time, thanks to COVID, working remotely has become much more normalised. Surveyors were, and still are, represented at various levels in the programme. I was working at the coal face with the technologists and analysts trying to understand what surveyors needed from a system. We also set up the Survey Working Group of about 10 respected professional surveyors from around the country. They came to Wellington every three months to provide rigour and help debate technical matters. They complemented the long-established Land Lawyer Group and the combined Stakeholder Forum. The Stakeholder Forum has higher level discussions and provides governance and important input into the longer-term direction for the whole ecosystem. This forum has elected members from Survey and Spatial New Zealand, the NZ Law Society, the Law Association, Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand and the Māori Land Court. During the early phases of the programme, I visited all the Survey and Spatial New Zealand branches around the country and held many brainstorming sessions. I was there with my Vivid pen and big bits of paper, as we identified:

the good things about Landonline that we didn’t want to lose

the things that were really painful about Landonline that we wanted addressed

the key shifts and step changes we wanted to see in the future system.

Using feedback from these sessions, the Survey Working

Group and I identified important issues and changes required for the new system. We generated a series of themes identifying the most important shifts that surveyors wanted to see in the system and presented these at branch meetings. From this feedback, we successfully managed to get many changes incorporated into the ASaTS system requirement documents (a set of documents detailing how the new system must work). However, the ASaTS approach never eventuated as the approach of LINZ setting up an in-house development team to replace legacy Landonline rapidly gained traction.