Natural justice

There are two arms to the principles of natural justice. The first is that no one can be the judge of their own case. The second is the right to a fair hearing. Not judging one’s own case seems self-evident but does need to be fully appreciated when dealing with clients who have legitimate complaints. Complainants must be assured that if their complaint escalates to a dispute, then there are independent authorities to which they may appeal for justice and who will adopt an impartial view of the issues (Robson and Page, 2020).

The right to a fair hearing requires some greater explanation. In the first instance appropriate and timely notice must be given of the time and place for such a hearing. This should allow the parties to properly prepare their positions. The hearing must give the defendant the opportunity to hear the case being made against them, consider the evidence presented by the complainant, and to the prepare a statement in rebuttal, challenging any or all of the evidence or offering an explanation of their conduct and any extenuating circumstances. Full disclosure of all relevant facts is a requirement of a hearing, and the ability of the defendant to face their accuser. Those hearing the evidence and making a judgement on whether breaches have occurred must not only be open-minded and unbiased in their considerations, but they must also be seen to be so.

For professional bodies, involving competent people who have no interest in the profession, or the individuals concerned in the dispute, is essential. Members of other professions usually make useful and desirable candidates for a hearings panel. In the end, decisions on breaches of professional ethical codes must be based on logical and rational evidence and made by impartial judges.

Conclusion

Professional ethics distinguish members of a profession from the rest of society. Compliance with the ethical code, when combined with technical competence, brings with it rights and responsibilities. The rights include personal status and reputation, and above average income. The responsibilities include being trustworthy, impartial, rational and responsible.

In order for an occupation to be granted the status of a profession, its requirements must include an ethical code. That code must be in the public domain, it must specify the manner of accepting complaints about breaches to that code, and must indicate the nature of penalties that will be applied should a member of that profession be found in breach of the code, that is, of being guilty of unprofessional conduct. The professional body must have empowered itself to enforce the penalties for such breaches.

While ethics and morals are closely linked, they are separate and distinct. Morals are a personal set of beliefs in appropriate behaviour, while ethics are a code of behaviour or practice that is defined by an external body. In some cases, an individual’s moral code will include those same or similar standards as a code of ethics. The effective difference is that a breach of an ethical code when detected, will have consequences with respect to the promulgator of the code, whereas breaches of one’s own moral code will not, other than one’s own conscience.

Finally, ethics cannot be left at the workplace––they pervade the life of a member of a profession. When a member of a profession departs from their workplace, or is outside the generally agreed working hours, the ethical standards remain with them. Ethics are about reputation. Reputation is hard won, but easily lost. Such loss of reputation may involve matters outside the normal conduct of business; ethics are, in fact, a way of life.

References

Carr-Saunders, A. M., & Wilson., P. A. (1933). The Professions: Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

Coutts, B. J. (2017). The Influence of Technology on the Land Surveying Profession. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Otago.

Flexner, Abraham. (1915). Is Social Work a Profession? Paper presented to the National Conference of Charities and Corrections at the Forty-Second annual session, Baltimore, Maryland.

International Ethical Standards Coalition. (2016). Accessed 20 January 2021. https://ricstest.files. wordpress.com/2016/12/international-ethics-standards-final.pdf

O’Day, Rosemary. (2000). The Professions in Early Modern England, 1450-1800: Servants of the Commonweal. Harlow, England: Longman. An imprint of Pearson Education.

Pearsall, Judy. (Ed). (1998). The New Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England.

Robson, W.A. and Page, E.C. (Accessed 25 June 2020) Britannica www.britannica.com/topic/administrative-law/The-ombudsman#ref36925.

Demand for, supply of, and diversity among surveyors: Fear and loathing in Alberta

Brian Ballantyne1 & Ceilidh Ballantyne

Abstract

The Alberta Land Surveyors Association (ALSA) fears its professional governance mandate is eroding. In furtherance of its mandate, ALSA posed three questions in 2022: How many ALSs are needed by 2033, can this need be met, will ALSA be diverse? Our answers were that 575 ALSs will be needed, conventional supply cannot meet demand, and ALSA is not diverse. We set out five strategies:

• Change the narrative to surveyors solving problems and addressing issues.

• Engage with Grade 9 and Grade 12 students to market surveying as a career.

• Liaise with post-secondary schools to support surveying as a career.

• Attract foreign-trained land surveyors (FTLS).

• Reform the articling process to retain more Articling Pupils.

The 15 recommendations will bear fruit by 2028, when 34 new ALSs will be supplied annually from six sources, resulting in a cumulative imbalance of 0 ALSs by 2033. At its April 2023 AGM, ALSA adopted the three best recommendations, which include hiring staff: One to focus on young students, another to focus on Articling Pupils and FTLS.

Abbreviations used in this article

AAIP Alberta Advantage Immigration Program

ALSA Alberta Land Surveyors Association

AOLS Association of Ontario Land Surveyors

ABCLS Association of British Columbia Land Surveyors

AGM Annual General Meeting

APT Articling Pupil Tutoring

APEGA Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of Alberta

ATP Accelerated Technical Pathway

BCIT British Columbia Institute of Technology

BCLS British Columbia Land Surveyor

BIPOC Black Indigenous and People of Colour

CPD Continuing Professional Development

CBEPS Canadian Board of Examiners for Professional Surveyors

CSLB New Zealand Cadastral Surveyors Licensing Board

FTLS Foreign Trained Land Surveyors

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GFCF Gross Fixed Capital Formation

GoA Government of Alberta

GPS Global Positioning System

LCS Licensed Cadastral Surveyor

LSA Law Society of Alberta

NAIT Northern Alberta Institute of Technology

OLS Ontario Land Surveyor

RPA Robotic Process Automation

RPR Real Property Report

SAIT Southern Alberta Institute of Technology

SLS Sakatchewan Land Surveyor

UC University of Calgary

UNB University of New Brunswick

UAV Unmanned Automated Vehicle

Introduction

We were somewhere around a breakthrough, in the midst of the second draft, when the doubts started to take hold.2 To wit, this is about surveyors in Alberta, whereas the audience is primarily surveyors in New Zealand. Nevertheless, this should resonate. After all, the same demand/supply/diversity issues plague both surveying professions.

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

ALSA retained us in September 2022 to answer three questions:

• How many Alberta Land Surveyors (ALSs) are needed by 2033?

ALSA retained us in September 2022 to answer three questions:

• Can post-secondary schools meet this need for ALSs? If not, then how can barriers be overcome to meet this need?

• Will ALSs represent the diversity of Alberta?

- How many Alberta Land Surveyors (ALSs) are needed by 2033?

This article sets out our findings, forecasts, strategies, and recommendations;3 and concludes with ALSA’s responses to the study since April 2023.

- Can post-secondary schools meet this need for ALSs? If not, then how can barriers be overcome to meet this need?

- Will ALSs represent the diversity of Alberta?

Context 1: Relevance to New Zealand surveyors

4

This article sets out our findings, forecasts, strategies, and recommendations;3 and concludes with ALSA’s responses to the study since April 2023. Context 1: Relevance to New Zealand surveyors4

Alberta has a similar population to New Zealand (4.6 M for AB and 5.1 M for NZ - Figure 1), supported by a variant of the same legal system and boundary principles, and with similar settlement, urbanization, demographics, and economic reliance on primary resources.

Alberta has a similar population to New Zealand (4.6 M for AB and 5.1 M for NZ - Figure 1), supported by a variant of the same legal system and boundary principles, and with similar settlement, urbanization, demographics, and economic reliance on primary resources.

6,000,000

2,500,000 3,375,000 4,250,000 5,125,000

AB pop NZ pop

Figure 1: Alberta & New Zealand population trends (1996-2020).

There are some discrepancies between the two jurisdictions, including the numbers of surveyors and the type of development. New Zealand has 707 LCSs, whereas Alberta has 404 ALSs. Since 1996, Alberta has built many more multi-residential dwellings than New Zealand, which require less survey effort than single-family subdivisions (Figure 2). Thus, New Zealand employs more surveyors per dwelling unit than Alberta.5

There are some discrepancies between the two jurisdictions, including the numbers of surveyors and the type of development. New Zealand has 707 LCSs, whereas Alberta has 404 ALSs. Since 1996, Alberta has built many more multi-residential dwellings than New Zealand, which require less survey effort than single-family subdivisions (Figure 2). Thus, New Zealand employs more surveyors per dwelling unit than Alberta.5

3 Ballantyne. Demand for, supply of, and diversity among AlberTa Land Surveyors to 2023. Report to ALSA. 86pp. February 5, 2023. We also looked into the distribution of ALSs, and the demand/supply/diversity of technicians. 4 Sue Hanham of Waimate focused on the lessons from New Zealand.

Figure 1: Alberta & New Zealand population trends (1996-2020).

Nevertheless, New Zealand and Alberta surveyors have similar laments, focusing on low supply and poor diversity. Over two-years (2019-2021), the New Zealand Cadastral Surveyors Licensing Board (CSLB), licensed 75 Licenced Cadastral Surveyors (LCSs), from three sources: 53 recent university graduates; 9 FTLS immigrants; 13 reinstated. Despite this intake, the total number of LCSs only increased by 20 (from 687 to 707); 55 LCSs did not renew their licenses. The CSLB acknowledged the tension. On the one hand, “there continues to be a demand for … surveyors to meet the needs of land development.” On the other hand, this demand raises the issue of “how to attract more students to the BSurv course, who then feed into our future LCSs.”6

This tension is made starker over a longer term. Since 2010, there have been significant increases in real GDP (41%), in population (19%), and in real GDP per capita (15%) in New Zealand.7 Yet, over that same period, the number of LCSs has declined from 727 to 707 (-3%),8 suggesting that supply is not meeting demand. As you know, various strategies are being employed (or discussed) to address these laments, but this article will not be carrying coals to Newcastle.9

Nevertheless, New Zealand and Alberta surveyors have similar laments, focusing on low supply and poor diversity. Over two-years (2019-2021), the New Zealand Cadastral Surveyors Licensing Board (CSLB), licensed 75 Licenced Cadastral Surveyors (LCSs), from three sources: 53 recent university graduates; 9 FTLS immigrants; 13 reinstated. Despite this intake, the total number of LCSs only increased by 20 (from 687 to 707); 55 LCSs did not renew their licenses. The CSLB acknowledged the tension. On the one hand, “there continues to be a demand for … surveyors to meet the needs of land development.” On the other hand, this demand raises the issue of “how to attract more students to the BSurv course, who then feed into our future LCSs.”6

Context 2: Professional governance

This tension is made starker over a longer term. Since 2010, there have been significant increases in real GDP (41%), in population (19%), and in real GDP per capita (15%) in New Zealand.7 Yet, over that same period, the number of LCSs has declined from 727 to 707 (-3%),8 suggesting that supply is not meeting demand. As you know, various strategies are being employed (or discussed) to address these laments, but this article will not be carrying coals to Newcastle.9

ALSA is the professional regulatory organization responsible for regulating surveying, and it is in the public interest that the number, competency, and diversity of ALSs are sufficient to serve Albertans. This means ensuring that the needs/demands of the public for surveying services is met (supply), while reflecting the characteristics and aspirations of Albertans (diversity). Indeed, maintaining the two links, between postsecondary education and surveying capacity, and between surveying capacity and the public’s needs/demands, is a major part of the ALSA 2022-23 Strategic Plan

Context 2: Professional governance

6 CSLB. Annual Report 2020-21

7 Statistics New Zealand. Tables DPE058AA and SNE004AA.

8 Although the five-year trend (2016-2021) shows an increase from 676 to 707 LCSs. CSLB Bulletins

9 S+SNZ Stakeholder Workshop. November 2019.

ALSA is the professional regulatory organization responsible for regulating surveying, and it is in the public interest that the number, competency, and diversity of ALSs are sufficient to serve Albertans. This means ensuring that the needs/demands of the public for surveying services is met (supply), while reflecting the characteristics and aspirations of Albertans (diversity). Indeed, maintaining the two links, between post-secondary education and surveying capacity, and between surveying capacity and the public’s needs/demands, is a major part of the ALSA 2022-23 Strategic Plan.

Figure 2: Alberta & New Zealand housing starts.

Figure 2: Alberta & New Zealand housing starts.

ALSA’s role is heightened owing to changes in how Alberta professional associations are to be regulated by Bill 23––Professional Governance Act, introduced in 2022. As a professional regulatory organization established under the Land Surveyors Act, ALSA is “to protect and serve the public interest and the interest of public safety by safeguarding life, health and the environment and the property and economic interests of the public.”10 This means that ALSA “administers affairs and regulates its registrants in a manner that protects the public interest and the interest of public safety.”11

In November 2022, the Mandate Letter to the Minister of Skilled Trades and Professions directed him to: “Implement the Professional Governance Act to ensure the adoption of a uniform governance framework for all professional regulatory organizations.”12 Since the provincial election in May 2023, however, little has been heard of Bill 23. The Ministry of Skilled Trades and Professions was supplanted by the Ministry of Jobs, Economy and Trade, whose Mandate Letter to the Minister made no mention of professional governance.13 Apparently, the Alberta government “remains committed to progressing the Bill 23 through the legislative process.”14 We suspect that Bill 23 is merely dormant, given the tendency in Alberta and other jurisdictions, such as British Columbia,15 to oversee the professions more closely in the public interest.

This legislative oversight is feared and loathed by ALSA. At its April 2023 Annual General Meeting (AGM), the President admitted that he was “nervous,” not least because Bill 23 allows ALSA to be replaced if it is not acting in the public interest or “is not viable in the long term economically.”16 This concern speaks directly to the supply and diversity of ALSs. At the same AGM, a former President railed that Bill 23 is merely creating “more red tape” and “does not make much sense,” because it lumps disparate professions and trades together. He promised that “he will do anything he can to ensure that it is not reintroduced.”17 The perceived threat posed by Bill 23 inspired ALSA to commission the study for which we were retained.

Context 3: ALSA baseline data

After peaking at 470 in 2015, the number of ALSs declined to 423 in 2021 and to 404 by September 2022, owing to weak economic activity and demographic aging (Figure 7). The pandemic hastened this diminution, with record levels of ALSs retiring in 2020. Of the 404 ALSs as of 2022, 32 are women (7.9%). In 2016, 24 of the 333 ALSs were women (7.2%). There are 41 Articling Pupils, so the ratio of Articling Pupils to ALSs is 10%. This is the lowest ratio since at least 1996; it has tended to be 25% (Figure 3).

10%. This is the lowest ratio since at least 1996; it has tended to be 25% (Figure 3).

10%. This is the lowest ratio since at least 1996; it has tended to be 25% (Figure 3).

3:

The median age of ALSs is 45 (Figure 4). The average age at retirement is falling. In 2016, the average age was 66; in 2019, it was 63; in 2021-22, it was 55. Although this is another disquieting trend, it does mean that there are youngish ex-ALSs who might be enticed back to ALSA as the economy soars.18

The median age of ALSs is 45 (Figure 4). The average age at retirement is falling. In 2016, the average age was 66; in 2019, it was 63; in 2021-22, it was 55. Although this is another disquieting trend, it does mean that there are youngish ex-ALSs who might be enticed back to ALSA as the economy soars.18

The median age of ALSs is 45 (Figure 4). The average age at retirement is falling. In 2016, the average age was 66; in 2019, it was 63; in 2021-22, it was 55. Although this is another disquieting trend, it does mean that there are youngish ex-ALSs who might be enticed back to ALSA as the economy soars.18

15 23

Figure 4: Age distribution for ALSs (as of 2022).

Almost 80% of ALSs graduated from four post-secondary schools – University of Calgary (UC), University of New Brunswick (UNB), Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) and Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT) (Figure 5). The origins of the remaining 20% are distributed evenly among overseas and Canadian post-secondary schools.19 Since 1996, ALSA has welcomed 36 ALSs from non-articling sources: ALSs who un-retired (4), and surveyors from other jurisdictions through interprovincial mobility (32).20 This works out to two ALSs per year, on average.

18 Dramatic foreshadowing; see the supply analysis.

19 We have such data for 385 of the 404 ALSs.

Almost 80% of ALSs graduated from four post-secondary schools – University of Calgary (UC), University of New Brunswick (UNB), Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) and Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT) (Figure 5). The origins of the remaining 20% are distributed evenly among overseas and Canadian post-secondary schools.19 Since 1996, ALSA has welcomed 36 ALSs from non-articling sources: ALSs who un-retired (4), and surveyors from other jurisdictions through interprovincial mobility (32).20 This works out to two ALSs per year, on average.

20 ALSA. Executive Director. December 14, 2022.

18 Dramatic foreshadowing; see the supply analysis.

19 We have such data for 385 of the 404 ALSs. 20 ALSA. Executive Director. December 14, 2022.

Almost 80% of ALSs graduated from four post-secondary schools––University of Calgary (UC), University of New Brunswick (UNB), Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) and Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT) (Figure 5). The origins of the remaining 20% are distributed evenly among overseas and Canadian post-secondary schools.19 Since 1996, ALSA has welcomed 36 ALSs from non-articling sources: ALSs who un-retired (4), and surveyors from other jurisdictions through inter-provincial mobility (32).20 This works out to two ALSs per year, on average.

Figure

Ratio of Articling Pupils to ALSs, 1996 to 2023.

Figure 4: Age distribution for ALSs (as of 2022).

Figure 3: Ratio of Articling Pupils to ALSs, 1996 to 2023.

Figure 3: Ratio of Articling Pupils to ALSs, 1996 to 2023.

Figure 4: Age distribution for ALSs (as of 2022).

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

of

Overseas

COGS

U of A College

BCIT

Other unIv

Univ - Geomatics

Ont College CONA

Figure 5: Most ALSs are graduates of only four post-secondary schools (as of 2022).

Figure 5: Most ALSs are graduates of only four post-secondary schools (as of 2022).

Figure 5: Most ALSs are graduates of only four post-secondary schools (as of 2022).

ALSs are distributed across 42 communities, with 171 based in Calgary, 71 based in Edmonton, 40 based in communities with populations greater than 50K (Red Deer, Lethbridge, Airdrie, Fort McMurray, Medicine Hat, Grande Prairie), and 56 based in smaller communities throughout Alberta (Figure 6).

ALSs are distributed across 42 communities, with 171 based in Calgary, 71 based in Edmonton, 40 based in communities with populations greater than 50K (Red Deer, Lethbridge, Airdrie, Fort McMurray, Medicine Hat, Grande Prairie), and 56 based in smaller communities throughout Alberta (Figure 6). Figure

ALSs are distributed across 42 communities, with 171 based in Calgary, 71 based in Edmonton, 40 based in communities with populations greater than 50K (Red Deer, Lethbridge, Airdrie, Fort McMurray, Medicine Hat, Grande Prairie), and 56 based in smaller communities throughout Alberta (Figure 6).

Figure 6: ALSs capture 75% of Alberta by area (within 160 km of 41 offices).

Figure 6: ALSs capture 75% of Alberta by area (within 160 km of 41 offices).

Of are employed in the private sector in Alberta.21 The remainder – 66 ALSs – work in government (provincial and municipal), at NAIT or for ALSA; are functionally retired or unemployed; work exclusively in non-cadastral disciplines (e.g. construction); or live outside Alberta.22 Of the 338 ALSs in the private

Of the 404 ALSs, 338 ALSs are employed in the private sector in Alberta.21 The remainder – 66 ALSs – work in government (provincial and municipal), at NAIT or for ALSA; are functionally retired or unemployed; work exclusively in non-cadastral disciplines (e.g. construction); or live outside Alberta.22 Of the 338 ALSs in the private

21 ALSA. Roll of members. January 1, 2022.

22 Six ALSs work exclusively in non-cadastral surveying, 14 ALSs work for government/NAIT/ALSA, and 27 ALSs live/work outside Alberta.

21 ALSA. Roll of members. January 1, 2022.

22 Six ALSs work exclusively in non-cadastral surveying, 14 ALSs work for government/NAIT/ALSA, and 27 ALSs live/work outside Alberta.

Of the 404 ALSs, 338 ALSs are employed in the private sector in Alberta.21 The remainder––66 ALSs––work in government (provincial and municipal), at NAIT or for ALSA; are functionally retired or unemployed; work exclusively in non-cadastral disciplines (e.g. construction); or live outside Alberta.22 Of the 338 ALSs in the private sector, 67 work in management, cost estimating or business development, “dealing with clients on contracts and rates, and reviewing major proposals”23

sector, 67 work in management, cost estimating or business development, “dealing with clients on contracts and rates, and reviewing major proposals”23

The result is that 271 ALSs author products (i.e. sign plans and other survey documents) across two distinct types of survey. The best estimate is that 55% of ALSs work in municipal development (N = 149 ALSs), and 45% of ALSs work in resource extraction or construction (N = 122 ALSs).24 There is little overlap.

The result is that 271 ALSs author products (i.e. sign plans and other survey documents) across two distinct types of survey. The best estimate is that 55% of ALSs work in municipal development (N = 149 ALSs), and 45% of ALSs work in resource extraction or construction (N = 122 ALSs).24 There is little overlap.

Methodology

Methodology

What we did not do

What we did not do

We did not link the ALS demand forecast solely to Alberta population projections (Figure 7). When ALSA started in 1911, there was one ALS per 5,100 people. Since 1996, the per capita rate has varied from one ALS per 9,000 people to one ALS per 11,500 people. Population is integrated with economic activity and is part of the demand analysis (inherent in the economic framework and linked to housing starts).

We did not link the ALS demand forecast solely to Alberta population projections (Figure 7). When ALSA started in 1911, there was one ALS per 5,100 people. Since 1996, the per capita rate has varied from one ALS per 9,000 people to one ALS per 11,500 people. Population is integrated with economic activity and is part of the demand analysis (inherent in the economic framework and linked to housing starts).

AB pop (millions), left ALSs, right

Figure 7: Tenuous relationship between Alberta population and number of ALSs (1996-2022).

What we did do

What we did do

We divided the ALS analysis according to demand (which focused on economic indicators and forecasts) and supply (which also dealt with diversity and distribution issues). Both analyses began with the same membership, received from ALSA:

We divided the ALS analysis according to demand (which focused on economic indicators and forecasts) and supply (which also dealt with diversity and distribution issues). Both analyses began with the same membership, received from ALSA:

- The number of ALSs from 1996 to September 2022.

- The number of Articling Pupils from 1996 to September 2022.

• The number of ALSs from 1996 to September 2022.

- An anonymized list of ALSs for 2016-2022, including gender, age, postsecondary school, year of commission, year of subtraction, and place of work.

• The number of Articling Pupils from 1996 to September 2022.

23 Interview. January 4, 2023.

24 ALSA. Director of Practice Review. October 19, 2022.

• An anonymized list of ALSs for 2016-2022, including gender, age, postsecondary school, year of commission, year of subtraction, and place of work.

Figure 7: Tenuous relationship between Alberta population and number of ALSs (1996-2022).

The demand methodology relied on macro-economic modelling and municipal insights:

• Forecasts and empirical models from the governments of Alberta and Canada, primarily through the Census, Statistics Canada, and other bodies.

• Interviews of nine Alberta municipalities and a review of their land use planning forecasts, to get a sense of municipal development.

The supply/diversity/distribution analysis relied on four sources:

• Interviewing 35 ALSs, teachers, administrators, and others; cited here by Interview Date. We posed 4-6 questions to each person.

• Canvassing ALSs using GoogleForms to ensure anonymity; cited here by Response to Question. We posed 35 questions; we received 50 responses.

• Studies from ALSA, Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of Alberta (APEGA), Law Society of Alberta (LSA), other professional regulators.

• The wisdom of 25 surveyors from other jurisdictions––Ontario, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and New Zealand.25

Assumptions

First, we are cognizant of the short-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2022) when forecasting demand, and when assessing ALS retirements and post-secondary school enrollments. Real economic activity contracted by 8.0% in 2020, the greatest contraction ever, something that historical time-series analysis cannot capture.

Second, we recognize that the 50 responses to the GoogleForms questionnaire are not representative of ALSA members, given self-selection and survivorship bias.26 Nevertheless, we use the responses to corroborate findings gleaned from other sources. Moreover, the response rate of 12% was excellent compared to recent studies on diversity/inclusion within other professions:

• APEGA accepted a response rate of 3%.27

• The Federation of Law Societies of Canada accepted a response rate of 5%.28

• The Australian geospatial community accepted a response rate of 5%.29

Third, we assume that there is currently not a surplus of ALSs nor of Articling Pupils. Rather, either demand/supply are in equilibrium, or demand is subtly exceeding supply. The assumption is supported by the variety of jobs that are consistently advertised in the ALSA weekly notices, and by the respondents, 86% of whom believe that the ideal number of ALSs to serve Albertans is at/above the current number (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Responses to Question 30.

8: Responses to Question 30.

Demand analysis

Demand analysis

Methodology for analyzing demand

Methodology for analyzing demand

Demand analysis

Methodology for analyzing demand

Alberta’s real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has tracked closely with the number of ALSs since at least 1996 (Figure 9). This is intuitive; demand for surveying is a function economic activity, linked to the drivers of Alberta’s economy: energy investment, engineering construction, and residential and non-residential construction. Excepting 2008 downturn, Alberta’s economy steadily grew from 1996-2014. The number of ALSs mirrored this trend. With stagnant economic growth since 2015, demand for surveying has waned, and this is reflected in the declining numbers of ALSs. Thus, the means of predicting future demand is predicting economic activity. 9: Real GDP (Alberta) and number of ALSs (indexed to 1996).

Alberta’s real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has tracked closely with the number of ALSs since at least 1996 (Figure 9). This is intuitive; demand for surveying is a function of economic activity, linked to the drivers of Alberta’s economy: energy investment, engineering construction, and residential and non-residential construction. Excepting the 2008 downturn, Alberta’s economy steadily grew from 1996-2014. The number of ALSs mirrored this trend. With stagnant economic growth since 2015, demand for surveying has waned, and this is reflected in the declining numbers of ALSs. Thus, the best means of predicting future demand is predicting economic activity.

Alberta’s real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has tracked closely with the number of ALSs since at least 1996 (Figure 9). This is intuitive; demand for surveying is a function of economic activity, linked to the drivers of Alberta’s economy: energy investment, engineering construction, and residential and non-residential construction. Excepting the 2008 downturn, Alberta’s economy steadily grew from 1996-2014. The number of ALSs mirrored this trend. With stagnant economic growth since 2015, demand for surveying has waned, and this is reflected in the declining numbers of ALSs. Thus, the best means of predicting future demand is predicting economic activity.

Figure 9: Real GDP (Alberta) and number of ALSs (indexed to 1996).

To forecast GDP for the 2023-2026 period, we consulted private and publicsector forecasts,30 analyzed the expenditure components of GDP (consumer spending, Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), investment, and net exports), and applied expert judgement. For the 2026-2033 period, we applied long-term

Figure 8: Responses to Question 30.

Figure 9: Real GDP (Alberta) and number of ALSs (indexed to 1996).

growth rates during similar prospective cyclical stages, focusing on population, employment, and long-term investment trends. Then, we broke down Alberta surveying activity into the three categories that align with GDP: residential, energy, and non-energy construction.

Population

Alberta’s population growth has long ebbed and flowed on Alberta’s overall economic tide. There is not much variation in natural increase, but international and interprovincial net migration are both responsive to Alberta’s economic climate. Interprovincial net migration was largely negative from 2015-2021 and international net migration ceased during the pandemic. These trends reversed course in 2022, spurring remarkable population growth. Following strong gains in the second quarter, Alberta added 58,203 residents in the third quarter (Q3) of 2022, posting the highest single quarter growth rate in over 40 years.

By 2026, Alberta’s population will grow by 324,000 (+7.2%). Much of this growth will be concentrated in Calgary (+8.3%) and Edmonton (8.2%), while Fort McMurray, Grande Prairie, and Red Deer will also experience notable growth. In 2033, Alberta’s population is expected to reach 5.4 M (an increase of at least 860,000). Again, Edmonton and Calgary will drive the growth (with over 21% growth for each).31

Residential construction sector

We concorded residential surveying activity to the two ubiquitous economic indicators of housing starts32 and residential construction investment.33 These feed into the broader residential structures GFCF, a key component in expenditure-based GDP.34 Alberta’s housing starts are widely forecasted by private and public-sector institutions. As indicators, they are connected to the economic fundamentals of employment, earnings, and population growth, which are other indicators that are widely forecasted. This allowed for robust comparison when projecting housing starts, residential construction investment, and demand for ALSs involved in large and small municipal development.

Spurred on by low inventories, a solid resale market, and high in-migration, housing starts are going to remain very strong in the medium term. We expect starts to average over 35,000 for 2023, 2024, 2025, and 2026. An aging housing stock will drive more infill development; this densification has been targeted in many of the municipal plans. Multi-unit starts should drive the trend, but singledetached starts will remain prevalent. After strong short-to-medium term growth, housing starts will likely ease off but remain around 33,000 per year,35 higher than any level between 2015 and 2020 (Figure 10).

Multi-unit starts should drive the trend, but single-detached starts will remain prevalent. After strong short-to-medium term growth, housing starts will likely ease off but remain around 33,000 per year,35 higher than any level between 2015 and 2020 (Figure 10).

Energy sector

For the energy sector, the primary indicators examined were prices (West Texas Intermediate – WTI, Western Canadian Select – WCS, Alberta Energy Company –AECO), and production of crude oil, crude bitumen, and natural gas. The production forecasts from the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER), the Canada Energy Regulator (CER), and the Province of Alberta provided a comprehensive snapshot of sector activity over the next 10 years. The breakdown by new, expansion, and existing projects allowed a forecast of demand for ALSs working on well sites and pipelines. Activity in this sector (as it relates to surveying) accounts for a portion of the GDP by expenditure category, GFCF in non-residential structures.

Crude oil production is expected to peak in 2025 at 520 thousand barrels per day (bpd),36 which is 19% higher than 2019, before gradually declining. Crude bitumen production is forecasted to grow throughout the 10-year period with overall bitumen production slated to peak in 2032.37 Relative to 2021, production is estimated to be up

For the energy sector, the primary indicators examined were prices (West Texas Intermediate––WTI, Western Canadian Select––WCS, Alberta Energy Company––AECO), and production of crude oil, crude bitumen, and natural gas. The production forecasts from the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER), the Canada Energy Regulator (CER), and the Province of Alberta provided a comprehensive snapshot of sector activity over the next 10 years. The breakdown by new, expansion, and existing projects allowed a forecast of demand for ALSs working on well sites and pipelines. Activity in this sector (as it relates to surveying) accounts for a portion of the GDP by expenditure category, GFCF in non-residential structures.

14% in 2026 to approximately 3.7 M bpd, and up 26% by 2031 to 4.1 M bpd. New projects and the expansion of existing projects, particularly for in-situ, will contribute to this increase in bitumen production (Figure 11).

Crude oil production is expected to peak in 2025 at 520 thousand barrels per day (bpd),36 which is 19% higher than 2019, before gradually declining. Crude bitumen production is forecasted to grow throughout the 10-year period with overall bitumen production slated to peak in 2032.37 Relative to 2021, production is estimated to be up 14% in 2026 to approximately 3.7 M bpd, and up 26% by 2031 to 4.1 M bpd. New projects and the expansion of existing projects, particularly for in-situ, will contribute to this increase in bitumen production

35 There are risks inherent to this housing starts forecast, which include supply chain issues and heightened input costs, elevated interest rates, stagnant wage growth, and employment shortages (e.g. current demand for framers).

36 “ST98.” 2022. Alberta Energy Regulator. May 30, 2022.

37 Government of Canada, Canada Energy Regulator. 2022. “CER – Welcome to Canada’s Energy Future 2021.”

Figure 10: Alberta housing starts to 2033.

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

Forecast of ALS demand

Figure 11: Energy sector forecast to 2031 (AER).

Figure 11: Energy sector forecast to 2031 (AER).

Forecast of ALS demand

Forecast of ALS demand

Figure 11: Energy sector forecast to 2031 (AER).

Forecasted demand is expected to jump 23% to 496 ALSs in 2026. This reflects the strong growth in residential building construction, non-energy construction, and sustained activity in the energy sector. This demand surge is jarring when juxtaposed with the current number of ALSs, requiring a sharp uptick after 2022 (Figure 12). This sharp uptick is largely caused by the declining employment trend of 2015-2022.

Forecasted demand is expected to jump 23% to 496 ALSs in 2026. This reflects the strong growth in residential building construction, non-energy construction, and sustained activity in the energy sector. This demand surge is jarring when juxtaposed with the current number of ALSs, requiring a sharp uptick after 2022 (Figure 12). This sharp uptick is largely caused by the declining employment trend of 2015-2022.

Forecasted demand is expected to jump 23% to 496 ALSs in 2026. This reflects the strong growth in residential building construction, non-energy construction, and sustained activity in the energy sector. This demand surge is jarring when juxtaposed with the current number of ALSs, requiring a sharp uptick after 2022 (Figure 12). This sharp uptick is largely caused by the declining employment trend of 2015-2022.

Figure 12: Number of ALSs (1996-2022) and forecast of ALS demand (2023-2033).

19961998200020022004200620082010201220142016201820202022e2024f2026f2028f2030f2032f Actuals Demand forecast

Figure 12: Number of ALSs (1996-2022) and forecast of ALS demand (2023-2033).

Demand for ALSs will be sustained from 2026-2033 but at a more measured rate of change. Forecasted demand is expected to jump 43% to 575 ALSs in 2033. This reflects Alberta’s strong economic fundamentals and overall growth (Figure 13).

Figure 12: Number of ALSs (1996-2022) and forecast of ALS demand (2023-2033).

Demand for ALSs will be sustained from 2026-2033 but at a more measured rate of change. Forecasted demand is expected to jump 43% to 575 ALSs in 2033. This reflects Alberta’s strong economic fundamentals and overall growth (Figure 13).

Demand for ALSs will be sustained from 2026-2033 but at a more measured rate of change. Forecasted demand is expected to jump 43% to 575 ALSs in 2033. This reflects Alberta’s strong economic fundamentals and overall growth (Figure 13).

13: Forecast of ALS demand and real GDP to 2033 (indexed to 1996).

Technology will likely not impact ALS demand. Just as total stations became the norm in the 1980s and GPS became the norm in the 2000s, advances in technology will continue within surveying. It’s a mixed blessing – although drone scanning offers benefits, Chat GPT is rubbish. We posed 52 questions about Alberta water boundary principles and practices, and 41 answers were wrong, both factually and legally.38 ChatGPT invented the names and citations of 10 court decisions, and it invented six journal articles (including the author, title, journal, and date).39 Thus, we expect that technology advances will not cause labour productivity growth rates to deviate from the historical norm nor will they reduce demand for ALSs. The interviews concurred: “I can’t see any change in technology that had the impact of GPS” on survey field time.40

Technology will likely not impact ALS demand. Just as total stations became the norm in the 1980s and GPS became the norm in the 2000s, advances in technology will continue within surveying. It’s a mixed blessing––although drone scanning offers benefits, Chat GPT is rubbish. We posed 52 questions about Alberta water boundary principles and practices, and 41 answers were wrong, both factually and legally.38 ChatGPT invented the names and citations of 10 court decisions, and it invented six journal articles (including the author, title, journal, and date).39 Thus, we expect that technology advances will not cause labour productivity growth rates to deviate from the historical norm nor will they reduce demand for ALSs. The interviews concurred: “I can’t see any change in technology that had the impact of GPS” on survey field time.40

The effect of using coordinates (not monuments) as boundary evidence will have one significant effect. There will be less need to set monuments for new boundaries, shifting effort from field to office, but not affecting the demand for ALSs. Coordinates will have no effect on searching for thousands of existing monuments41 nor for other evidence (e.g. nothing changes for riparian boundaries), nor on assessing encroachments across boundaries (e.g. lasting improvements). The interviews agreed that coordinates will change little in terms of ALS demand to 2033, because “in today’s highly computerized and digital world, the industry is using coordinates all the time in survey operations.”42 Our forecasts were corroborated through the interviews and responses. One ALS observed that “the demand for services is increasing as energy prices recover.”43 Another ALS noted that any reduction in demand from the resource extraction sector by

38 This is known as “hallucinating” in the ChatGPT world.

39 “There’s something scary about stupidity made coherent.” Stoppard. The Real Thing 2014.

40 Interview. October 10, 2022.

The effect of using coordinates (not monuments) as boundary evidence will have one significant effect. There will be less need to set monuments for new boundaries, shifting effort from field to office, but not affecting the demand for ALSs. Coordinates will have no effect on searching for thousands of existing monuments41 nor for other evidence (e.g. nothing changes for riparian boundaries), nor on assessing encroachments across boundaries (e.g. lasting improvements). The interviews agreed that coordinates will change little in terms of ALS demand to 2033, because “in today’s highly computerized and digital world, the industry is using coordinates all the time in survey operations.”42

41 Some of which date to the DLS township system of the 1870s.

42 Interview. December 16, 2022.

43 Response 17 to Question 35.

Our forecasts were corroborated through the interviews and responses. One ALS observed that “the demand for services is increasing as energy prices recover.”43 Another ALS noted that any reduction in demand from the resource extraction sector by 2033 will be offset by increased demand from alternative energy resources. The effect will be to “change the type of work that surveyors are completing,” from large projects with many crews to multiple smaller projects with only a few crews per ALS.44

Figure 13: Forecast of ALS demand and real GDP to 2033 (indexed to 1996).

Real GDP ALS, actuals ALS

Figure

Supply analysis

2033 will be offset by increased demand from alternative energy resources. The effect will be to “change the type of work that surveyors are completing,” from large projects with many crews to multiple smaller projects with only a few crews per ALS.44

Supply

analysis

Methodology for analyzing supply

Methodology for analyzing supply

Using ALSA retirement data from 1996, and the ages of ALSs from 20162022, we forecast retirements based on the current age profile. The number of people retiring should come down from its current elevated levels. Since 1996, 304 ALSs have retired, for a median of eight retirements/year. Thus, we forecast that eight ALSs will retire annually after 2026 (Figure 14). Also, there is the potential for some people to return to ALSA, if their departures were influenced by the pandemic.

Using ALSA retirement data from 1996, and the ages of ALSs from 2016-2022, we forecast retirements based on the current age profile. The number of people retiring should come down from its current elevated levels. Since 1996, 304 ALSs have retired, for a median of eight retirements/year. Thus, we forecast that eight ALSs will retire annually after 2026 (Figure 14). Also, there is the potential for some people to return to ALSA, if their departures were influenced by the pandemic.

The supply of ALSs is a function of Articling Pupils being commissioned as ALSs, migration from overseas, inter-provincial mobility, reinstatements, and retirements. We bifurcate the supply analysis into two phases: 2023-2027 and 2028-2033, because ALSA’s recruitment strategies are limited in the short-term given the lengthy education and articling process. Thus, our two supply forecasts to 2027 are conservative; they rely on the inventory of 41 Articling Pupils and the average articling time of five years.

After 2027, both supply forecasts are more optimistic (i.e. less conservative), but our positive supply forecast diverges from our neutral supply forecast. Our Recommendations will start to bear fruit after 2027 for the positive supply forecast.

The supply of ALSs is a function of Articling Pupils being commissioned as ALSs, migration from overseas, inter-provincial mobility, reinstatements, and retirements. We bifurcate the supply analysis into two phases: 2023-2027 and 2028-2033, because ALSA’s recruitment strategies are limited in the short-term given the lengthy education and articling process. Thus, our two supply forecasts to 2027 are conservative; they rely on the inventory of 41 Articling Pupils and the average articling time of five years.

After 2027, both supply forecasts are more optimistic (i.e. less conservative), but our positive supply forecast diverges from our neutral supply forecast. Our Recommendations will start to bear fruit after 2027 for the positive supply forecast.

Interview. October 11, 2022.

Figure 14: Forecast of ALS retirements to 2033.

Figure 14: Forecast of ALS retirements to 2033.

Neutral supply forecast

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

The neutral forecast is based on ALSA doing-nothing (by relying on existing inventory and historic trends, and by rejecting the Recommendations). It assumes: Existing inventory to 2027:

• 38 Articling Pupils are commissioned as ALSs.45

The neutral forecast is based on ALSA doing-nothing (by relying on existing inventory and historic trends, and by rejecting the Recommendations). It assumes:

• Two ALSs/year come from outside the articling process (i.e. inter-provincial mobility and reinstatement) based on historic rates. By 2027, there are: 48 new ALSs, a net loss of four ALSs, and 398 ALSs in toto.

- Existing inventory to 2027:

o 38 Articling Pupils are commissioned as ALSs.45

After 2027, we forecast that:

• Retirements level off to historic rates = 8/year.

o Two ALSs/year come from outside the articling process (i.e. interprovincial mobility and reinstatement) based on historic rates.

- By 2027, there are: 48 new ALSs, a net loss of four ALSs, and 398 ALSs in toto.

• Newly commissioned ALSs rebound to historic rates = 22/year.46

- After 2027, we forecast that:

• Two ALSs/year come from inter-provincial mobility and reinstatement. By 2033, there are: 132 new ALSs, a net loss of 78 ALSs, and 482 ALSs in toto.

o Retirements level off to historic rates = 8/year.

o Newly commissioned ALSs rebound to historic rates = 22/year.46

o Two ALSs/year come from inter-provincial mobility and reinstatement.

The greatest risk of neutrality is that ALSA suffers a cumulative imbalance of 101 ALSs by 2026 and 93 ALSs by 2033 (Figure 15), meaning that it will not be regulating in the public interest. Interviews elaborated on the risks:

- By 2033, there are: 132 new ALSs, a net loss of 78 ALSs, and 482 ALSs in toto.

The greatest risk of neutrality is that ALSA suffers a cumulative imbalance of 101 ALSs by 2026 and 93 ALSs by 2033 (Figure 15), meaning that it will not be regulating in the public interest. Interviews elaborated on the risks:

• There are not “enough ALSs … with enough experience to do the job well.”47

- There are not “enough ALSs … with enough experience to do the job well.”47

- “Will letting market forces thin out the herd end up in an overall death spiral?”48

• “Will letting market forces thin out the herd end up in an overall death spiral?”48

15: Neutral supply of ALSs; cumulative imbalance = 93 ALSs by 2033.

Figure 15: Neutral supply of ALSs; cumulative imbalance = 93 ALSs by 2033.

Positive supply forecast

The Recommendations eliminate the cumulative imbalance by 2033, assuming:

Positive supply forecast

- Existing inventory to 2027:

o 38 Articling Pupils are commissioned as ALSs by 2027.

The Recommendations eliminate the cumulative imbalance by 2033, assuming: Existing inventory to 2027: 38 Articling Pupils are commissioned as ALSs by 2027.

45 Historically, 22% of Articled Pupils have not been commissioned as ALSs.

46 Given the average number of newly commissioned ALSs/year from 2009 to 2019.

• Six ALSs/year come from outside the articling process, four from interprovincial mobility and two from reinstatement.

47 Interview. October 11, 2022 48 Interview. October 17, 2022.

Figure

By 2027, there are: 68 new ALSs, a net gain of 14 ALSs, and 418 ALSs in toto.

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

After 2027, we forecast that:

• Retirements level off to historic rates = 8/year.

o Six ALSs/year come from outside the articling process, four from interprovincial mobility and two from reinstatement.

- By 2027, there are: 68 new ALSs, a net gain of 14 ALSs, and 418 ALSs in toto.

- After 2027, we forecast that:

o Retirements level off to historic rates = 8/year.

• Newly commissioned ALSs = 34/year, which is within the realm of the possible49 owing to ALS strategies: Recruiting at junior/senior high schools, liaising with post-secondary schools, welcoming FTLS, reducing articling leakage to 10%.

• Six ALSs/year come from inter-provincial mobility and from reinstatement. By 2033, there are: 270 new ALSs, a net gain of 168 ALSs and 572 ALSs in toto.

o Newly commissioned ALSs = 34/year, which is within the realm of the possible49 owing to ALS strategies: Recruiting at junior/senior high schools, liaising with post-secondary schools, welcoming FTLS, reducing articling leakage to 10%.

o Six ALSs/year come from inter-provincial mobility and from reinstatement.

The positive forecast has the benefit of reducing the cumulative imbalance to 0 by 2033,50 meaning that ALSA will continue to regulate in the public interest (Figure 16).

- By 2033, there are: 270 new ALSs, a net gain of 168 ALSs and 572 ALSs in toto.

The positive forecast has the benefit of reducing the cumulative imbalance to 0 by 2033,50 meaning that ALSA will continue to regulate in the public interest (Figure 16).

16: Positive supply of ALSs; cumulative imbalance = 0 ALSs by 2033.

Conventional supply

Conventional supply

To elaborate on the positive supply forecast, we do not anticipate that post-secondary schools (focusing on UC and UNB, who supply almost 60% of all ALSs) will meet the demand for ALSs by 2033.51 UC and UNB each have the capacity to enroll 60 geomatics engineering students annually, for a total across the two schools of 120 new students each year. This means that the two schools might supply 34 ALSs annually after 2033, if ALSA marketing efforts succeed with junior/senior high school students and if the schools – particularly UC – are receptive.

Before 2033, UC and UNB are unlikely to enroll and thus graduate sufficient numbers of students, owing to time delays and competition. On average, it takes 12-years for a

49 In 2009, the ratio of 30 new/existing ALSs = 8.2% and in 2028, the ratio of 34 new/existing ALSs = 7.5%.

To elaborate on the positive supply forecast, we do not anticipate that postsecondary schools (focusing on UC and UNB, who supply almost 60% of all ALSs) will meet the demand for ALSs by 2033.51 UC and UNB each have the capacity to enroll 60 geomatics engineering students annually, for a total across the two schools of 120 new students each year. This means that the two schools might supply 34 ALSs annually after 2033, if ALSA marketing efforts succeed with junior/senior high school students and if the schools––particularly UC––are receptive.

50 Actually, to within three ALSs of the demand forecast of 575 ALSs (within 0.05%) which is in keeping with generally accepted economic forecasting principles (GAEFP).

51 BCIT supplies few ALSs, focuses on supplying graduates to British Columbia, and did not respond to our queries.

Before 2033, UC and UNB are unlikely to enroll and thus graduate sufficient numbers of students, owing to time delays and competition. On average, it takes 12-years for a Grade 9 student to be commissioned as an ALS, and nine years for a Grade 12 student to be commissioned as an ALS. Also, there is much

Figure 16: Positive supply of ALSs; cumulative imbalance = 0 ALSs by 2033.

Figure

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

competition for graduates. Other jurisdictions within Canada aggressively vie for UNB graduates. Other geomatics disciplines (e.g. positioning/navigation) vie for UC graduates.

Grade 9 student to be commissioned as an ALS, and nine years for a Grade 12 student to be commissioned as an ALS. Also, there is much competition for graduates. Other jurisdictions within Canada aggressively vie for UNB graduates. Other geomatics disciplines (e.g. positioning/navigation) vie for UC graduates.

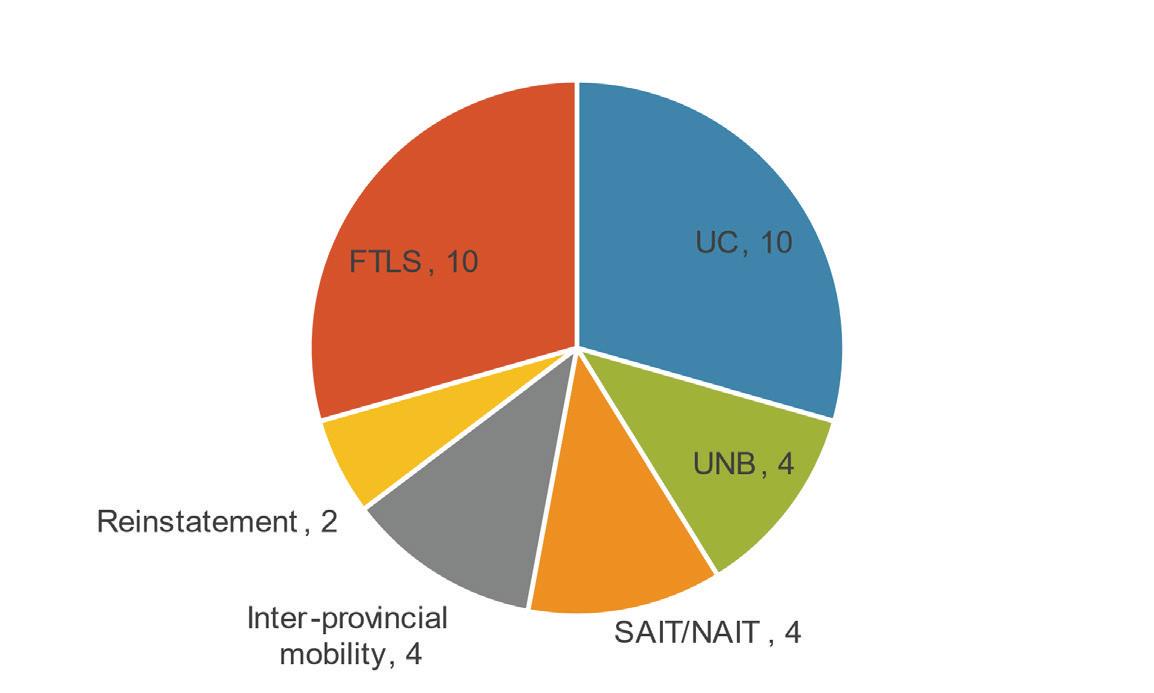

We forecast that, from 2028 to 2033, 34 new ALSs will be supplied annually from six sources––with Canadian post-secondary schools supplying 53% of ALSA demand and foreign-trained land surveyors (FTLS) supplying 29% of ALSA demand (Figure 17):

We forecast that, from 2028 to 2033, 34 new ALSs will be supplied annually from six sources – with Canadian post-secondary schools supplying 53% of ALSA demand and foreign-trained land surveyors (FTLS) supplying 29% of ALSA demand (Figure 17):

• 10 from UC.

- 10 from UC.

• 4 from UNB.

- 4 from UNB.

- 4 from other post-secondary schools (NAIT, SAIT, BCIT, other).

• 4 from other post-secondary schools (NAIT, SAIT, BCIT, other).

- 4 from inter-provincial mobility.

• 4 from inter-provincial mobility.

- 2 from reinstatement.

• 2 from reinstatement.

- 10 from overseas, as FTLS.

• 10 from overseas, as FTLS.

Strategies

ALSA mandate

The following five strategies, for eliminating by 2033 the cumulative imbalance between demand and supply, are fully within ALSA’s mandate as a professional regulator. ALSA has a responsibility to ensure that there are a sufficient number of ALSs to meet public demand, that education is sufficient to provide a rigorous level of service to the public, and that ALSs represent the diversity of Alberta. Indeed, the Independent Regulatory Review of ALSA concluded that offering professional development programs and engaging in or sponsoring research “does not undermine the ALSA’s public protection mandate and may in fact enhance it.”52

18

Figure 17: The six sources of 34 ALSs/year after 2027.

Figure 17: The six sources of 34 ALSs/year after 2027.

certainly the consensus of respondents: 80% believe that ALSA must “actively surveying as an interesting, important, lucrative, respected profession” so as to ALSA demand by 2033. This does not mean marketing surveying services or products; it does mean marketing surveying as a career. The message to be amplified the strategies is: Become an ALS; it is a worthy career.

Strategy 1: Change the narrative

That is certainly the consensus of respondents: 80% believe that ALSA must “actively market surveying as an interesting, important, lucrative, respected profession” so as to meet ALSA demand by 2033. This does not mean marketing surveying services or products; it does mean marketing surveying as a career. The message to be amplified through the strategies is: Become an ALS; it is a worthy career.

ubiquitous surveying narrative combines two tropes: That surveyors are “good at enjoy the outdoors, and don’t mind solo work in nature” and that technology is “Hello, drones! Pardon me, UAVs/RPAs.”53 The irony is that few ALSs actually outside; 85% of respondents spend less than 1/3 of their time at the job site 18). Somewhat wistfully, one respondent wished that: “I would like to see many ALS members, with much more of a presence in the field.”54

Strategy 1: Change the narrative

The ubiquitous surveying narrative combines two tropes: That surveyors are “good at math, enjoy the outdoors, and don’t mind solo work in nature” and that technology is cool––“Hello, drones! Pardon me, UAVs/RPAs.”53 The irony is that few ALSs actually work outside; 85% of respondents spend less than 1/3 of their time at the job site (Figure 18). Somewhat wistfully, one respondent wished that: “I would like to see many more ALS members, with much more of a

Responses to Question 13.

Figure 18: Responses to Question 13. A common theme from the interviews and the responses was that this surveying narrative must change:

Independent regulatory review. p49. September 2020. Masikewich. Help wanted: Advocacy required. PSC Magazine v2-n2. pp7-10. Fall 2022. Response 14 to Question 35.

• “If the narrative stays the same,” that surveying is represented by a ScottishCanadian man standing behind a tripod on the 19th century frontier, then surveying will continue to struggle to attract young people.55 Such a narrative, while clear and iconic, is inaccurate in 2023, let alone in 2033 (Figure 19).56

• The virtues of choosing a career that involves working outside are oversold. Such a motif suggests toughness and a frontier mentality, turns off some people, and is belied by respondents.57

• Surveying is more than proficiency in mathematics and science; focusing on those skills tends to discount problem-solving, analyzing and communicating.58

• “Traditions and history are good, but also give the impression of land surveying being an Old Boys Club … Members need to recognize that

- Surveying is more than proficiency in mathematics and science; focusing on those skills tends to discount problem-solving, analyzing and communicating.58

- “Traditions and history are good, but also give the impression of land surveying being an Old Boys Club Members need to recognize that changes in society are coming fast (e.g. coordinates as monuments) and position themselves accordingly as experts.”59

changes in society are coming fast (e.g. coordinates as monuments) and position themselves accordingly as experts.”59

55 Interview. December 20, 2022.

56 To be fair, much of the content of the book is excellent – entertaining and inspiring.

57 Interview. December 17, 2022.

58 Interview. December 23, 2022.

59 Response 2 to Question 35.

20 and is belied by respondents.57

The narrative must position surveying “in a very different light”60––one of analyzing, solving problems, resolving disputes, confronting issues, and addressing societal needs.61 According to an interview: “The most valuable technical staff are the most versatile. The most desirable skills are not … focused on the technology alone, but rather on problem-solving and self-learning skills, built on fundamental knowledge.”62

Technology should only be extolled as a means to an end. And the end is a holistic view of “looking beyond being experts at measuring coordinates and to the broader role as part of the infrastructure development process.”63 This includes sustainable development, alternative energy production, climate change, land tenure reform, and so on. The new narrative also must target diversity, moving away from the common narrative of “the pale male fellow making an observation using a total station” to a narrative of “a professional providing a boundary opinion on the extent of ownership and how it protects the public, creates social harmony and drives economic development.”64

Changing the narrative is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition. The if-webuild-it-he-will-come tactic might be effective in conjuring a baseball player,65 but it is ineffective on its own in addressing the cumulative imbalance. The narrative must be supplemented by discrete actions, as captured by the remaining four Strategies.

Figure 11: An iconic, yet inaccurate narrative.

Figure 19: An iconic, yet inaccurate narrative.

Changing the narrative is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition. The if-we-build-ithe-will-come tactic might be effective in conjuring a baseball player,65 but it is ineffective on its own in addressing the cumulative imbalance. The narrative must be supplemented by discrete actions, as captured by the remaining four Strategies.

Strategy 2: Liaise with post-secondary schools

Strategy 2: Liaise with post-secondary schools

The relationship between ALSA and the post-secondary schools that offer surveying/geomatics engineering is critical to ensuring the viability of both. We focus in this Strategy on UC and UNB because they have supplied 55% of current ALSs (Figure 20). So, ALSA must “prioritize the … relationships with the educational institutions that provide the supply of new professionals” and those same schools must “prioritize … relationships with professional associations which can provide it with a look forward to the types of skills that graduates need.”66

The relationship between ALSA and the post-secondary schools that offer surveying/geomatics engineering is critical to ensuring the viability of both. We focus in this Strategy on UC and UNB because they have supplied 55% of current ALSs (Figure 20). So, ALSA must “prioritize the … relationships with the educational institutions that provide the supply of new professionals” and those same schools must “prioritize relationships with professional associations which can provide it with a look forward to the types of skills that graduates need.”66

Figure 20: Most ALSs have graduated from four post-secondary schools; annual ratios since 2016.

Figure 20: Most ALSs have graduated from four post-secondary schools; annual ratios since 2016.

60 Interview. December 20, 2022.

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

61 As reflected in a recent article: Thompson. True lines. PSC Magazine v2-n2. P11. Fall 2022.

62 Interview. October 7, 2022.

63 Interview. January 5, 2023.

64 Interview. November 4, 2022.

65 Field of Dreams film. 1989.

66 Interview. January 5, 2023.

It is a two-way street. Reject the opinion that it is not the university’s role to market the surveying/geomatics engineering degree, that it is only ALSA’s role to market the university programme.67 Rather, mutual marketing is required, because “if we don’t increase the number of trained students coming from post secondary the system will crumble for lack of personnel.”68 Both UNB and UC recognize that recruiting students is critical; that the goal is bums-on-seats (Figure 21).

It is a two-way street. Reject the opinion that it is not the university’s role to market the surveying/geomatics engineering degree, that it is only ALSA’s role to market the university programme.67 Rather, mutual marketing is required, because “if we don’t increase the number of trained students coming from post secondary … the system will crumble for lack of personnel.”68 Both UNB and UC recognize that recruiting students is critical; that the goal is bums-on-seats (Figure 21).

Figure 21: Google counts of "bums on seats" per publication. The first use was in 1970; usage peaked in 2013.

UC had 193 geomatics engineering graduates in the past seven academic years (2016 to 2022), of whom 73 (38%) concentrated on cadastral surveying. UNB had 119 graduates in geomatics engineering in the past four academic years (since 2019-20), of whom 102 (86%) concentrated on cadastral surveying.69 By way of comparison:

University Mean no. of cadastral grads (annual) Proportion of total grads

UC

UC had 193 geomatics engineering graduates in the past seven academic years (2016 to 2022), of whom 73 (38%) concentrated on cadastral surveying. UNB had 119 graduates in geomatics engineering in the past four academic years (since 2019-20), of whom 102 (86%) concentrated on cadastral surveying.69 By way of comparison:

The short-term (to 2026) outlook is not rosy. UNB anticipates that student enrollment will decline in the next three years. The main source of students are colleges offering

Figure 21: Google counts of "bums on seats" per publication. The first use was in 1970; usage peaked in 2013.

The short-term (to 2026) outlook is not rosy. UNB anticipates that student enrollment will decline in the next three years. The main source of students are colleges offering two-year diplomas in geomatics engineering (e,g. NAIT, SAIT, College of Geographic Sciences and College of the North Atlantic), graduates from which are entering the workforce directly “due to the abundance of highpaying jobs.”70

UC now relies on sessional instructors to teach surveying (e.g. survey law, land use planning). Also, it anticipates continuing to struggle to entice first year engineering students into geomatics engineering in general, and into cadastral surveying in particular, for four reasons:

• The appeal of the four engineering minors that the Faculty introduced in 2020.

• The appeal of the software minor that the Department introduced in 2022.

• First year students have little exposure to surveying (Appendix 1).

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

• First year students are “guaranteed placement in their first choice of program.”71

The outlook to 2033 is rosier if both schools grasp the nettle. UNB promises to introduce variety into its curriculum, and to offer hybrid learning platforms. UC promises to offer a cadastral minor (to compete with the other minors now available), to redouble its recruitment efforts, and to work with the Dean to hire a surveying professor. An interview suggested that a post-graduate diploma in “cadastral law makes the most sense,” to better prepare Articling Pupils.72

- First year students are “guaranteed placement in their first choice of program.”71

The outlook to 2033 is rosier if both schools grasp the nettle. UNB promises to introduce variety into its curriculum, and to offer hybrid learning platforms. UC promises to offer a cadastral minor (to compete with the other minors now available), to redouble its recruitment efforts, and to work with the Dean to hire a surveying professor. An interview suggested that a post-graduate diploma in “cadastral law makes the most sense,” to better prepare Articling Pupils.72

It was moved at the 2022 ALSA AGM that “ALSA should consider fully sponsoring the U of C cadastral chair for the next 10 years.”73 This is not one of our Strategies, and it is not one of our Recommendations. The numbers of UC geomatics engineering graduates and cadastral concentration graduates have varied widely since 2012, trends that have been immune to Chair funding (Figure 22).

It was moved at the 2022 ALSA AGM that “ALSA should consider fully sponsoring the U of C cadastral chair for the next 10 years.”73 This is not one of our Strategies, and it is not one of our Recommendations. The numbers of UC geomatics engineering graduates and cadastral concentration graduates have varied widely since 2012, trends that have been immune to Chair funding (Figure 22).

Total grads Cadastral grads

22: Wide variance in UC graduate numbers since 2012.

Funding a Chair’s salary does not survive a cost-benefit analysis, where the benefit is future ALSs. Only 39% of respondents are in favour of financially supporting schools to meet the demand for ALSs (Figure 23). Moreover, the experiences with post-secondary schools in Ontario (University of Toronto, York University, Toronto Metropolitan University and Sir Sandford Fleming College) are that salary funding is not linked to

Figure 22: Wide variance in UC graduate numbers since 2012.

Figure

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

Funding a Chair’s salary does not survive a cost-benefit analysis, where the benefit is future ALSs. Only 39% of respondents are in favour of financially supporting schools to meet the demand for ALSs (Figure 23). Moreover, the experiences with post-secondary schools in Ontario (University of Toronto, York University, Toronto Metropolitan University and Sir Sandford Fleming College) are that salary funding is not linked to robust student enrollment. The recent AOLS offer to help fund the York programme was rebuffed owing to low student numbers, and the current AOLS offer to fund part of the Fleming programme can only be justified by student enrollment.

Figure 23: Responses to Question 34.

Figure 23: Responses to Question 34.

Strategy 3: Engage with junior/senior high school students

Figure 23: Responses to Question 34.

Strategy 3: Engage with junior/senior high school students

Strategy 3: Engage with junior/senior high school students

As a means for recruiting people into surveying, 32% of the cross-Canada respondents believed that raising public awareness of surveying must focus on junior/senior high school students, and 26% of the cross-Canada respondents decided to become surveyors while in high school.74 This school influence was higher in Alberta. A school/vocational counsellor was the single largest influence on respondents becoming ALSs; 37% were exposed to surveying as a career by a counsellor (Figure 24).

As a means for recruiting people into surveying, 32% of the cross-Canada respondents believed that raising public awareness of surveying must focus on junior/senior high school students, and 26% of the cross-Canada respondents decided to become surveyors while in high school.74 This school influence was higher in Alberta. A school/vocational counsellor was the single largest influence on respondents becoming ALSs; 37% were exposed to surveying as a career by a counsellor (Figure 24).

As a means for recruiting people into surveying, 32% of the cross-Canada respondents believed that raising public awareness of surveying must focus on junior/senior high school students, and 26% of the cross-Canada respondents decided to become surveyors while in high school.74 This school influence was higher in Alberta. A school/vocational counsellor was the single largest influence on respondents becoming ALSs; 37% were exposed to surveying as a career by a counsellor (Figure 24).

Figure 24: Responses to Question 3.

Figure 24: Responses to Question 3.

74 AOLS. New member and articling student survey January 2023.

Engaging with junior/senior high school students was widely supported:

74 AOLS. New member and articling student survey. January 2023.

Engaging with junior/senior high school students was widely supported:

• “ALSA must get out there and explain to would-be surveyors what we do––why not visit the High Schools?”75

• “Our focus on universities/colleges comes too late … We would recruit far more young people to our profession if they were only made aware that we exist.”76

In Edmonton and Calgary, there are 225 schools that offer Grade 9, and 76 schools that offer Grade 12, in the public and separate school authorities. This is an enormous audience that is keen to hear about surveying as a career; it is also an audience that is refreshed annually. There are 68 more public, separate and charter school authorities across the province, most of which offer Grade 9 and Grade 12. Thus, we suspect that there are another 300 schools offering Grade 9 or 12, for a total of 600 schools.

The actions for implementing this strategy are set out in the Recommendations. Suffice to say that engaging with junior/senior high school students is best left to an ALSA career practitioner, to whom the students can relate. ALSs should not be visiting schools to entice students into surveying, for a couple of reasons. First, ALSs are not trained as presenters nor advocates for surveying as a career; they have other skills. Second, this is a critical strategy that cannot be left to volunteers.

Strategy 4: Welcome Foreign-Trained Land Surveyors (FTLSs)

By 2046, the Alberta population is forecast to be 6.4 M. We realize that this window is greater than the 10-years to 2033, yet it is instructive. The 2022-2046 population will increase by some 1.8 M, over half of which (55%) will come from international migration. This means that some 1 M new Albertans will have been born outside Alberta; Alberta will “become increasingly diverse.”77

There is “a whole world of people with credentials,”78 that has been little tapped by ALSA. Only 4% of ALSs were trained overseas. Within this ratio, however, there is a trend, because 80% of the FTLS became ALSs since 2009. This must trend upwards. The 1M new Albertans can contain many FTLS if ALSA is aggressive, given the experience with Ontario (28% of recent OLSs started as FTLS).

Immigration to Alberta is facilitated by the Alberta Advantage Immigration Program (AAIP) through the Express Entry Stream (EES). The EES favours immigrants under NAICS Code 5413, which captures architecture, engineering, and related services. Surveying and mapping––which includes land surveying services––falls within NAICS Code 5413 as Code 541370. This is good news for FTLS. However, the EES also has an Accelerated Technical Pathway (ATP) that favours immigrants captured by 38 National Occupational Classification (NOC) Codes. The Codes assess the level of training, formal education and experience required by a profession, and the responsibilities of such a professional. Land surveying is now NOC 21203, and this is not one of the 38 favoured codes under

the ATP. If Alberta can be persuaded to include NOC 21203 within the ATP, then it will be easier to attract FTLS.

Submitted to New Zealand Surveyor – October 29, 2023

not one of the 38 favoured codes under the ATP. If Alberta can be persuaded to include NOC 21203 within the ATP, then it will be easier to attract FTLS.

This strategy is in keeping with the ALSA’s efforts to exempt FTLS from articling, ensuring that qualified individuals entering regulated professions do not face unfair processes or barriers. It is also in keeping with the efforts of the Canadian Board of Examiners for Professional Surveyors (CBEPS), which has a review process to evaluate the education and credentials of FTLSs. CBEPS has processed 33 applications from FTLS, 13 of whom have been assigned a learning plan to meet the Canadian requirements, and five of whom have received Certificates of Completion.79 The strategy of aggressively welcoming FTLS to Alberta simply carries ALSA’s efforts and CBEPS’ processes to the next level.

This strategy is in keeping with the ALSA’s efforts to exempt FTLS from articling, ensuring that qualified individuals entering regulated professions do not face unfair processes or barriers. It is also in keeping with the efforts of the Canadian Board of Examiners for Professional Surveyors (CBEPS), which has a review process to evaluate the education and credentials of FTLSs. CBEPS has processed 33 applications from FTLS, 13 of whom have been assigned a learning plan to meet the Canadian requirements, and five of whom have received Certificates of Completion.79 The strategy of aggressively welcoming FTLS to Alberta simply carries ALSA’s efforts and CBEPS’ processes to the next level.

Strategy 5: Plug the leaky articling pipeline

Strategy 5: Plug the leaky articling pipeline

Since 1996, 522 people entered articles through ALSA, 116 of whom did not complete articles, because they were laid off, left Alberta, or left the surveying profession (Figure 25).80 This leakage rate of 22% is too high on the face of it, and is significantly higher than rates in other jurisdictions where “they generally all get through, given enough time.”81 In 2021 alone, more Articling Pupils (seven) had their articles terminated than were commissioned as ALSs (six).82