Editor Glyn Bowerman

Photo Editor Jasper Flores

OALA Editorial Board

Saira Abdulrehman

Greg Baskin

Chris Canning

Tracy Cook

Everett DeJong

Ryan De Jong

Mark Hillmer

Helene Iardas

Brad Keeler

Matthew Lundstrom

Sarah MacLean

Sarah Manteuffel

Shahrzad Nezefati

Nadja Pausch

Carol Pietka

Dalia Todary-Michael

Jennifer Wan

Web Editor

Jennifer Foden

Social Media Manager

Jennifer Foden

Art Direction/Design

Noël Nanton/typotherapy www.typotherapy.com

Advertising Inquiries advertising@oala.ca

416.231.4181

Cover Moss. Photo by Matthew Lundstrom. See page 20.

Ground: Landscape Architect Quarterly is published four times a year by Ontario Association of Landscape Architects.

Ontario Association of Landscape Architects

3 Church Street, Suite 506 Toronto, Ontario M5E 1M2

416.231.4181 www.oala.ca info@oala.ca

Copyright © 2023 by Ontario Association of Landscape Architects. Contributors retain copyright of their work. All rights reserved.

ISSN: 0847-3080

Canada Post Sales Product Agreement No. 40026106

See www.groundmag.ca to download articles and share content on social media.

See www.groundmag.ca for a digital, searchable, archival database, listing all articles, authors, subjects, key words, etc. published in Ground over the years.

2022-2023 OALA

Governing Council

President

Steve Barnhart

Vice President

Stefan Fediuk

Treasurer

Cameron Smith

Secretary

Justin Whalen

Past President

Jane Welsh

Councillors

Matthew Campbell

Aaron Hirota

Shawn Watters

Associate Councillor—Senior

Jenny Trinh

Associate Councillor—Junior

Layal Bitar

Lay Councillor

Karen Liu

Appointed Educator

University of Guelph

Nadia Amoroso

Appointed Educator

University of Toronto

Elise Shelley

University of Guelph

Student Representative

Allison Neuhauser

University of Toronto

Student Representative

Emiley Switzer-Martell

OALA Staff

Executive Director

Aina Budrevics

Administrator

Richard Stamper Registrar

Ingrid Little

Coordinator

Sherry Bagnato

Membership Services Administrator

Angie Anselmo

About

Ground: Landscape Architect Quarterly is published by Ontario Association of Landscape Architects and provides an open forum for the exchange of ideas and information related to the profession of landscape architecture. Letters to the editor, article proposals, and feedback are encouraged. For submission guidelines, contact Ground at magazine@oala.ca. Ground reserves the right to edit all submissions. The views expressed in the magazine are those of the writers and not necessarily the views of OALA and its Governing Council.

Upcoming Issues of Ground Ground 62 (Summer)

Democracy

Ground 63 (Fall) Messy

Deadline for advertising space reservations: July 4, 2023

Ground 64 (Winter)

Seen/Unseen

Deadline for editorial proposals July 7, 2023

Deadline for advertising space reservations: October 16, 2023

About OALA

Ontario Association of Landscape Architects works to promote and advance the profession of landscape architecture and maintain standards of professional practice consistent with the public interest. OALA promotes public understanding of the profession and the advancement of the practice of landscape architecture. In support of the improvement and/or conservation of the natural, cultural, social and built environments, OALA undertakes activities including promotion to governments, professionals and developers of the standards and benefits of landscape architecture.

Advisory Panel

Advisory Panel Message and a Call to All for Contributions

In an effort to streamline the editorial process for Ground, and after much deliberation, the Editorial Board has decided to dissolve the Advisory Panel.

Ground would like to express heartfelt thanks to Panel members, past and present, for their contributions to over 50 issues of the magazine.

This was a difficult decision, but one we are confident will maintain the energy and imagination necessary for future issues.

What is needed most, at this time, is a robust and diverse Editorial Board and contributing writers. Anyone interested in joining is encouraged to email magazine@oala.ca, Subject Line: Volunteering.

You do not need to be an OALA member or landscape architect to contribute to either the Editorial Board or the magazine, and anyone who expresses interest will be seriously considered.

Masthead OALA OALA .61 .61

TO VIEW ADDITIONAL CONTENT RELATED TO GROUND ARTICLES, VISIT WWW.GROUNDMAG.CA.

MODERATED BY GLYN BOWERMAN

President’s Message

The legacy of COVID-19 will be how we managed to cope through quiet times, learned about our relationship with the natural world, and stayed alive—physically, emotionally, spiritually, and mentally.

I became OALA President two years ago, in the middle of the pandemic, when being outdoors became vital. In this final message as President, I think on how lucky we are to live in Ontario, where nature is all around.

TEXT BY SHAHRZAD NEZAFATI, OALA AND TRACY COOK

TEXT BY MATTHEW LUNDSTROM

TEXT BY MILLIE KNAPP

TEXT BY JASMINE NIHMEY VASDI

Editor’s Message

TEXT BY RYAN DE JONG

I’m proud to be among professionals who spearhead the creation and design of spaces that provide wellbeing for millions. And to share several of our accomplishments, including the development of the 2022 - 2026 Strategic Plan, built around five strategic intentions considered vital to achieving OALA’s five-year mission. In challenging times, membership has remained constant, which has solidified the financial position of the organization. And we have made important progress towards securing a Landscape Architect Practice Act.

Raising the profile

Since June of 2022, OALA has reached over 19 million Canadians with news and insights into our profession. On a provincial level, landscape architecture was featured in an opinion article, authored by council member Shawn Watters, in the Toronto Star and the Waterloo Region Record. Recently, associate member Gail Shillingford was interviewed on CTV News. We have also been featured in Canadian Architect Magazine, Municipal Word, Y Magazine, Building Magazine, and the Windsor Star.

Advocacy efforts continue to voice our position on issues including Bill 23, the More Homes Built Faster Act, proposed changes to the Greenbelt Plan, and the Ontario Place redevelopment.

Practice Act

We have met with key MPPs, creating momentum in our pursuit of a practice act. By the time you read this, we will have hosted a breakfast at Queen’s Park, creating an opportunity for members to meet MPPs and communicate the value landscape architects deliver to Ontario.

As I transition to the role of Past President, I will remain engaged as we review our bylaws to comply with legislation for non-profit organizations. I look forward working with our new president and a smooth transition of leadership. I am proud to have served as President, and believe together we have elevated the profile of the profession, and hopefully inspired fellow members and others

STEVE BARNHART, OALA, CSLA OALA PRESIDENT PRESIDENT@OALA.CA

Regular Ground readers will be familiar with the Round Table section we include in each issue. It’s a panel discussion on a theme with various experts from landscape architecture and related fields. As editor, I have the pleasure and problem of taking that conversation—usually just shy of an hour in length—and trimming it down for publication. “Pleasure,” because I get the unfiltered thoughts of a variety of very smart, interesting, and innovative people. “Problem,” because it’s often difficult to cut a conversation like that down: even some of the interesting parts have to go.

I’m grateful, then, to be able to share here some parting wisdom from this issue’s Round Table guest Eha Naylor, who said of landscape architects:

“This is the best time we’ve had, honestly. Because the problems that are omnipresent are ones that we can really contribute to, and it’s exciting when you do a good job of it.”

This issue is about taking the new-found appreciation and energy around landscape that resulted from the pandemic, and moving it forward. Even in the face of supply chain issues, inflation, and a quickly-changing legislative landscape in this province.

As well, in these pages you’ll find a list of some particularly resilient native species of both flora and fauna, and some ideas about how to weave mental health and wellbeing into design (especially in the winter months now fairly in our rearview).

You’ll also find Millie Knapp’s column about the beauty found in a little bog, and a dispatch from Bali, Indonesia, about how one landscape legend lives on through his work.

I hope you enjoy our “Stayin’ Alive” issue, and another season of rejuvenation.

And, if you’d like to see your own words in these pages, don’t hesitate to send me your story ideas at the email below. We have some compelling themes for Fall and Winter, and we’re always looking for submissions.

GLYN BOWERMAN EDITOR MAGAZINE@OALA.CA

Contents President’s Message Editor’s Message

03/ Up Front Information on the ground Stayin’ Alive: 08/ Round Table Maintaining Momentum: riding the new wave of landscape appreciation

16/ Mental Health Reflections on Winter and Public Space

20/ Resilient Plants of Ontario A Short list of Hearty Heroes

26/ Grounding The Great Importance of a Little Bog

28/ Letters From... Bali: a Garden Memorial to a Landscaping Legend

32/ Notes A miscellany of news and events 42/ Artifact Through The Cracks

Spring 2023 Issue 61

European buckthorn, Norway maple, emerald ash borer: these are the species we commonly see signs of while walking around natural sites in Ontario. Online videos of people struggling to get rid of spotted lantern flies and spongy moth caterpillars have also been going viral for the last few years. Starting my landscape architecture degree, I remember learning about how many plants were invasive in my plant identification class and wondering why they were so frequently planted. Turns out, invasive species have not been receiving due or effective regulation and management in the province, according to the 2022 Auditor General’s report.

01/ The emerald ash borer is a wood-boring beetle native to Asia.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

02/ Starry Stonewort is a freshwater macroalgae from Europe and Asia that displaces local plants and aquatic animals.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

03/ Seed pods of a dog-strangling vine, also known as European swallow-wort.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

Up Front: Information on the Ground

03 Up Front .61

03 02 01

POLICY invasives

Last November, Ontario Auditor General Bonnie Lyst came out with a series of scathing value-for-money reports on the provincial government’s spending practices and policies, among which was an alarming audit of Ontario’s invasive species management.

According to the report, the Natural Resources Ministry “is not effectively monitoring the introduction and spread of harmful invasive species in Ontario.”

The Ministry, which is the provincial lead in the matter, has demonstrated various inefficiencies in regulating invasive species. Examples include delays in regulation, unregulated, harmful invasive species, ineffective monitoring, and insufficient funding for regulation and collaborative partners.

The inefficiency in dealing with invasive species holds significant consequences for Ontarians, including those in the landscape architecture profession. Invasive species create concerns for agriculture, forestry, tourism, and fisheries, and they impact public health, infrastructure, and the environment. Climate change may also have a hand in accelerating the spread and impact of invasive species because of increasing favourable conditions for some of these species. A Global News article on the report emphasized the gross economic impact of invasive species with a striking headline: “Ontario spends $4 million fighting invasive species, a $3.6 billion problem.”

Dr. Robert Corry, one of my landscape architecture professors at the University of Guelph who holds a doctorate in Natural Resources and the Environment, says that invasive species have always been a problem. Many invasive plants are not listed on municipal noxious weed lists, complicating the process to deal with them and removing the impetus for something to be done. This then allows the species to have more time to spread.

04/ Tree-eating spotted lanternflies, native to Southeast Asia.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

05/ A leaf suffering from “oak wilt,” a disease caused by fungus threatening to spread north from the U.S.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

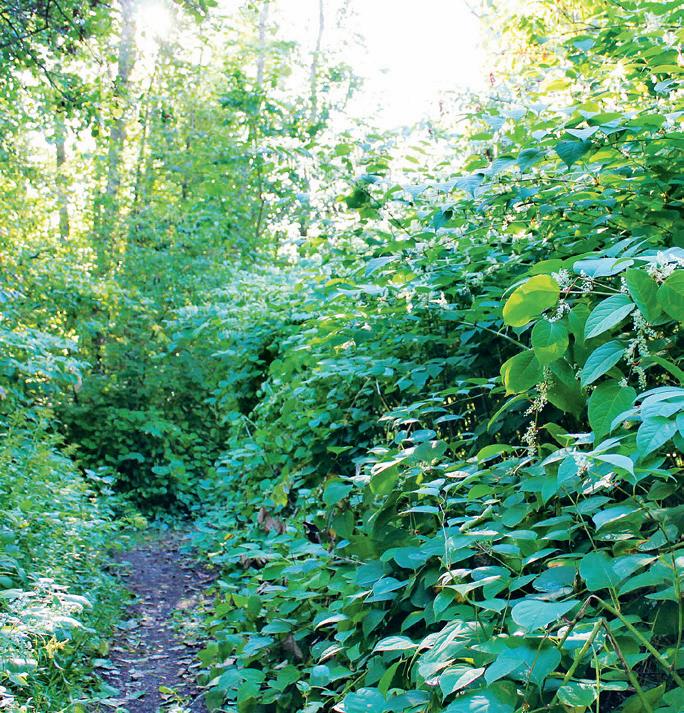

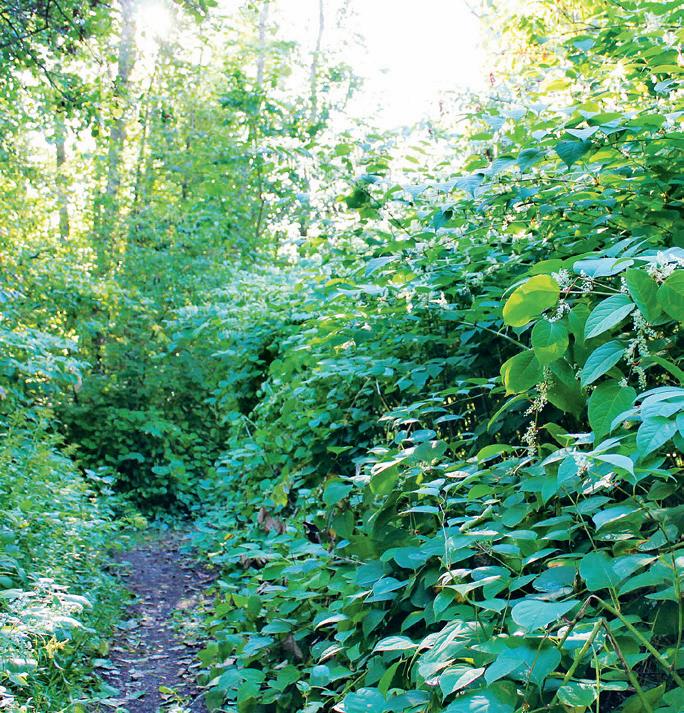

06/ The bamboo-like Japanese knotweed outcompetes native plants.

04/ Tree-eating spotted lanternflies, native to Southeast Asia.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

05/ A leaf suffering from “oak wilt,” a disease caused by fungus threatening to spread north from the U.S.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

06/ The bamboo-like Japanese knotweed outcompetes native plants.

04 Up Front .61

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

05 06 04

When it comes to landscape architecture, specifically, invasive species are a huge challenge for restoration work. In ecological work, Dr. Corry says that due to the lack of budget to do broadscale intensive revegetation of a site, “anything that has a gap in it—meaning bare soil—is the opportunity for those species to spread into these lands.” In addition, when ground is lost to invasive species, they increase, outcompete, and become harder to manage. As a result, restoration work done by conservation authorities require strict sanitary protocols for machinery.

Other landscapes heavily impacted by invasive species are riparian zones and highway corridors, examples Dr. Corry points out are easily invaded. “Partly it is because of the continuous network of the landscape, and partly because they’re just sort of outside of the realm of ordinary kinds of management and maintenance.”

Saltwater from the road creates conditions for salt-tolerant invasive species, while the movement of water and wind across these landscapes helps spread them.

When asked about the potential consequences of inaction regarding invasive species, Dr. Corry said, “The direst consequence is we’ll actually lose loads of [native] species because they can’t compete, which could be a local thing or even more widespread.” The species loss can also have a compounding effect on entire ecosystems. Working against invasive species makes it more difficult to monitor and manage a landscape, and it makes projects more expensive.

How can we, as landscape architects and project managers, help mitigate the spread of invasive species? Many levels of a project, from planting design to maintenance, offer opportunities to introduce or prevent the spreading of invasive species. And, Dr. Corry says, the $3.6 billion-problem only refers to the base level of species; below that, invasive genes in native species are also becoming a problem. “A lot of landscape architecture practitioners, especially restoration-minded ones, are starting to become much more attentive to what the seed supply was or where the genetic material came from.”

07/ Oak wilt-infected bark.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

08/ The egg masses of the spongy moth, whose caterpillars devour foliage.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

05 Up Front .61 TEXT/ JENNIFER WAN IS A SECOND YEAR MASTERS OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STUDENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH AND SITS ON THE EDITORIAL BOARDS OF GROUND AND LANDSCAPES PAYSAGES

08 07

Ontario has a rich orcharding history, with apples being grown in the province since the late 1700s. Unfortunately, many of these small pioneer farms are disappearing, along with the heritage varieties they once grew. But remnants of these orchards can still be seen dotted along hedgerows and woodlots, where apple blossoms and fruit add splashes of colour to the landscape.

In response to the decline of historic orchards and cultivars, the Dr. Brian Husband Lab at the University of Guelph started the Ontario Heritage and Feral

Apple Tree Project in 2020. Research goals were to expand the genetic database library to include more heritage cultivars, and to improve knowledge on the distribution of abandoned orchards, historic trees, and native crabapples. To accomplish this, apple cultivar identification tests were opened to the public, where people with heritage trees could send in samples at a small fee. Such testing has generally only been offered in the U.S or the U.K.

Since then, hundreds of samples have been sent in, giving the research team valuable

06 Up Front .61

09/ A Wolf River apple collected from an abandoned orchard in Guelph, ON.

IMAGE/ Paul Kron

TREES heritage apples 09

data and insights. Discussing the various heritage varieties he has found, Paul Kron, research associate at the lab, notes there are many incredible varieties not sold in grocery stores that he wishes more people could taste. Common cultivars from the tests include the classic Macintosh, but also lesser-known varieties such as duchess, yellow transparent, and Wolf River. The Wolf River cultivar is famous for producing apples so large it has been said you can make a whole pie out of just one.

Research at the lab has also shown when domestic apples (Malus domestica) grow close to the native crabapples (Malus coronaria), many of the seeds produced by the crabapples are hybrids with domestic apples. The lab is now seeking to understand the impact of this hybridization on native populations. It is possible that these feral trees may help maintain native pollinator species, but they might also harbour pests that could damage crops in nearby orchards.

Through working on this project over the years, something Kron has found is that “people love apples.” He notes how small community groups in regions such as St. Joseph’s Island have formed to collect and send in samples. Once their trees are identified, some people have even taken to grafting to keep their old tree cultivar going. (Grafting is a tree propagation technique that is used to ensure that the same tree is cloned, since apple seeds are often hybridized).

Asked what his favourite variety is, Kron takes his time before answering. He loves the classic Macintosh, and charismatic Wolf River, but after some thought, he says it is most likely the yellow transparent, a cultivar that grew in his parent’s backyard in Guelph. The tree was, in fact, a remnant of an old orchard that belonged to his grandparents. He grew up with that tree, and even has one growing in his yard today. He says, “When I eat them, it sends a wave of nostalgia that takes me back to my childhood. When barely ripe, it has a nice and crisp flavour to it, but as soon as it gets fully ripe, it gets all soft and you make applesauce.”

Aside from the genetic value of retaining these heritage cultivars, it is clear that apples have strong cultural value to Ontarians. Through the diligent work of the Husband lab and apple enthusiasts alike, these heritage cultivars will keep on providing.

More info on this project can be found at: https://www.husbandlab.ca/Apples/

07 Up Front .61

10/ A Gideon apple tree found in Elizabethtown, ON.

IMAGE/ Jim Sones

11/ Apple tasting at O’Keefe Grange orchard near Dobbington, ON.

IMAGE/ Paul Kron

11

ON

TEXT/ RYAN DE JONG IS A MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STUDENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH AND GREW

UP WORKING

HIS FAMILY’S NURSERY NEAR VANCOUVER, B.C.

10

riding the new wave of landscape appreciation

MODERATED BY GLYN BOWERMAN

MODERATED BY GLYN BOWERMAN

08 Round Table .61

BIOS/ KEN YEE CHEW, IS A RECENTLY-ELECTED GUELPH CITY COUNCILLOR FOR WARD 6. HE IS AN URBAN DESIGNER WITH A BACHELOR OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH WHO HAS WORKED IN THE PLANNING DEPARTMENT AT THE CITY OF BRAMPTON.

KEN IS AN ASSOCIATE MEMBER OF THE OALA.

EHA NAYLOR, OALA, FCSLA, IS A PARTNER EMERITA IN DILLON CONSULTING LIMITED’S NATIONAL LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND COMMUNITY PLANNING PRACTICE. SHE HAS EARNED AWARDS RECOGNIZING HER EXPERTISE IN URBAN AND ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN AND ADVOCATES FOR LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS, INCLUDING AS PAST CHAIR OF THE OALA PRACTICE LEGISLATION COMMITTEE. SHE WAS NAMED FELLOW OF THE CANADIAN SOCIETY OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS, SELECTED FOR THE OALA PINNACLE AWARD FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT, AWARDED THE CSLA PRESIDENTS AWARD, AND RECEIVED THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO ARBOUR AWARD FOR VOLUNTEER SERVICE. CURRENTLY, SHE SERVES AS THE PRESIDENT OF THE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE CANADA FOUNDATION AND IS APPOINTED TO THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO.

MIKE TOCHER, OALA, RPP, IS A PARTNER WITH THINC DESIGN (TOCHER HEYBLOM DESIGN INC), WHERE HE CO-LEADS A TALENTED TEAM OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS, PLANNERS, AND ARBORISTS UNDERTAKING A DIVERSE RANGE OF PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTOR PROJECTS FROM INITIAL CONCEPT DESIGN THROUGH TO CONSTRUCTION ADMINISTRATION. CURRENTLY, MUCH OF MIKE’S WORK FOCUSES ON PARKS AND RECREATION MASTER PLANS, PARK DESIGN, WATERFRONTS, AND TRAIL PROJECTS THROUGHOUT ONTARIO.

GLYN BOWERMAN IS THE EDITOR OF GROUND MAGAZINE. HE IS A TORONTO-BASED JOURNALIST WHO WRITES PRIMARILY ABOUT CANADIAN URBAN ISSUES AND MUNICIPAL POLITICS. HE ALSO HOSTS THE MONTHLY SPACING RADIO PODCAST, AND A SENIOR EDITOR WITH SPACING MAGAZINE.

Glyn Bowerman: During the pandemic, we had a renewed appreciation for landscape, and a lot was said about the “new normal” and how landscape would play a big part in whatever that ultimately was. Now we’re thinking about post-pandemic life, how do we ensure we remember the lessons we’ve learned in the past few years?

Eha Naylor: The lessons learned during the pandemic—the appreciation of public open space, the importance of accessing it to people’s physical and mental health—that kind of awareness hasn’t changed. People still appreciate it. However, one area that is still a real risk is climate change, and landscape architects are very much in the forefront of that and should continue to be and advocate for that. We should take what we’ve learned during the pandemic and apply it to helping our communities understand what we can do to improve the quality of their life and to improve the physical environment we all share.

GB: Ken, I imagine you are either in the process of or just finished your first budget process at the City of Guelph. In those conversations, was there talk of keeping the momentum around public space and landscape in your community?

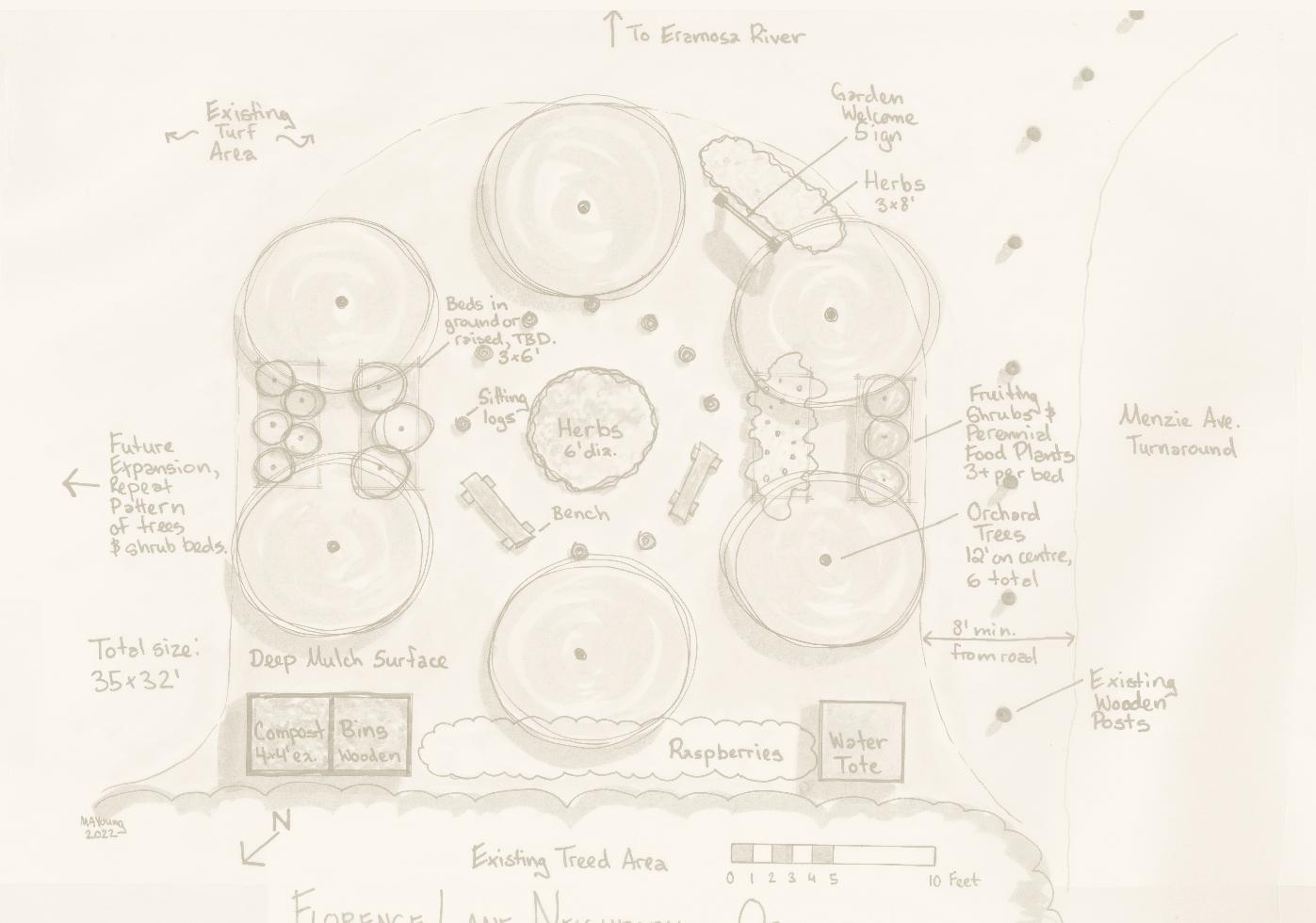

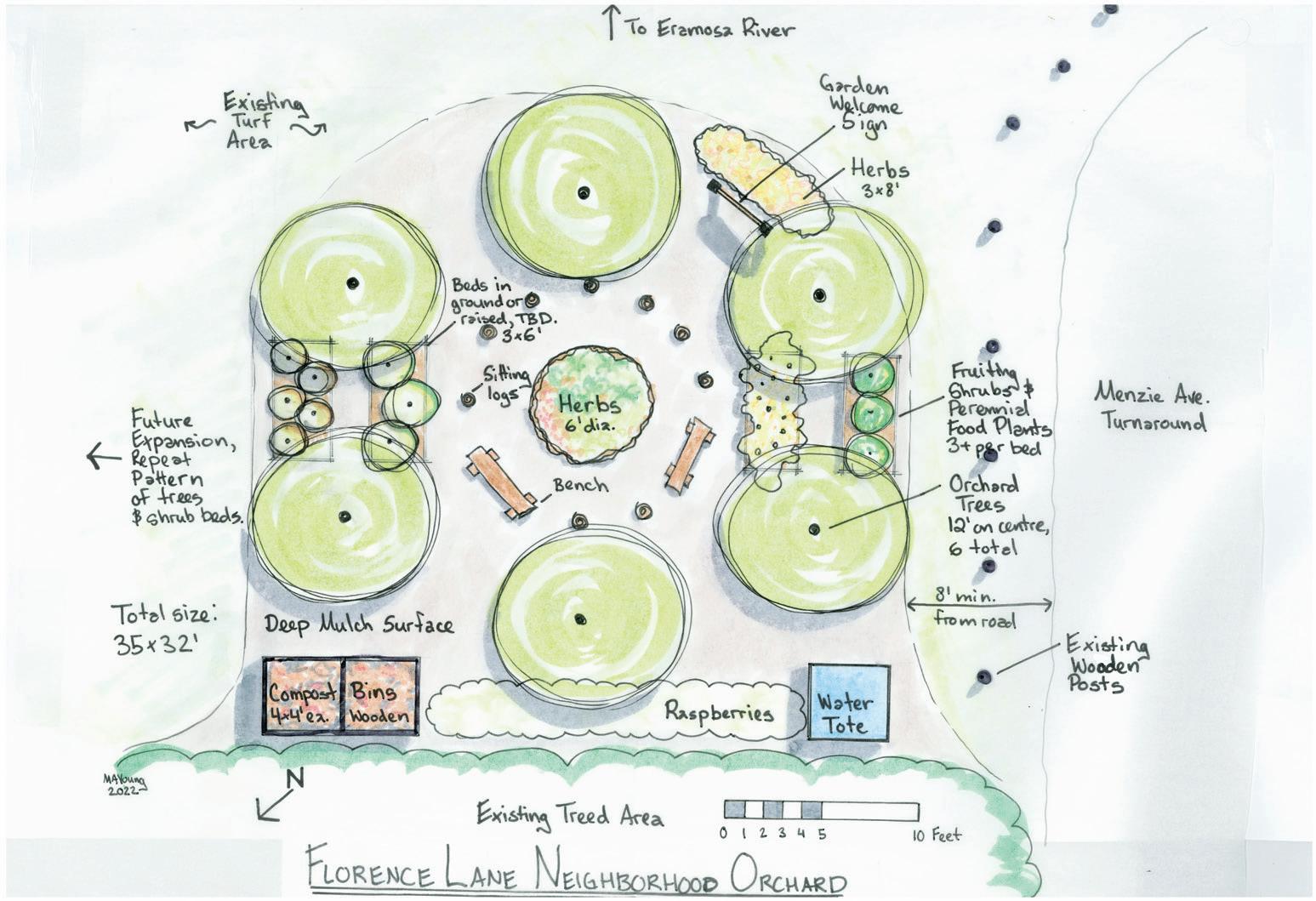

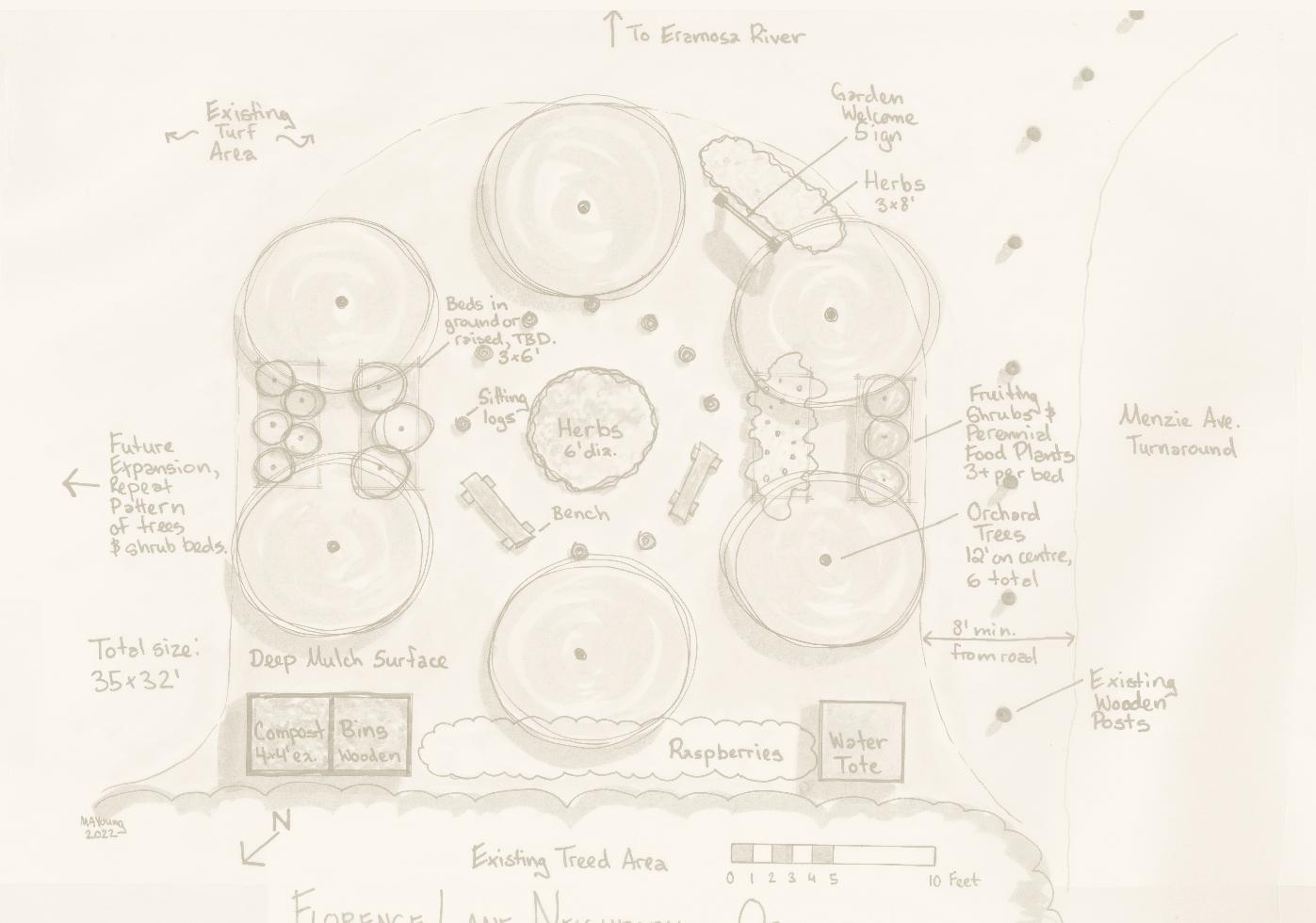

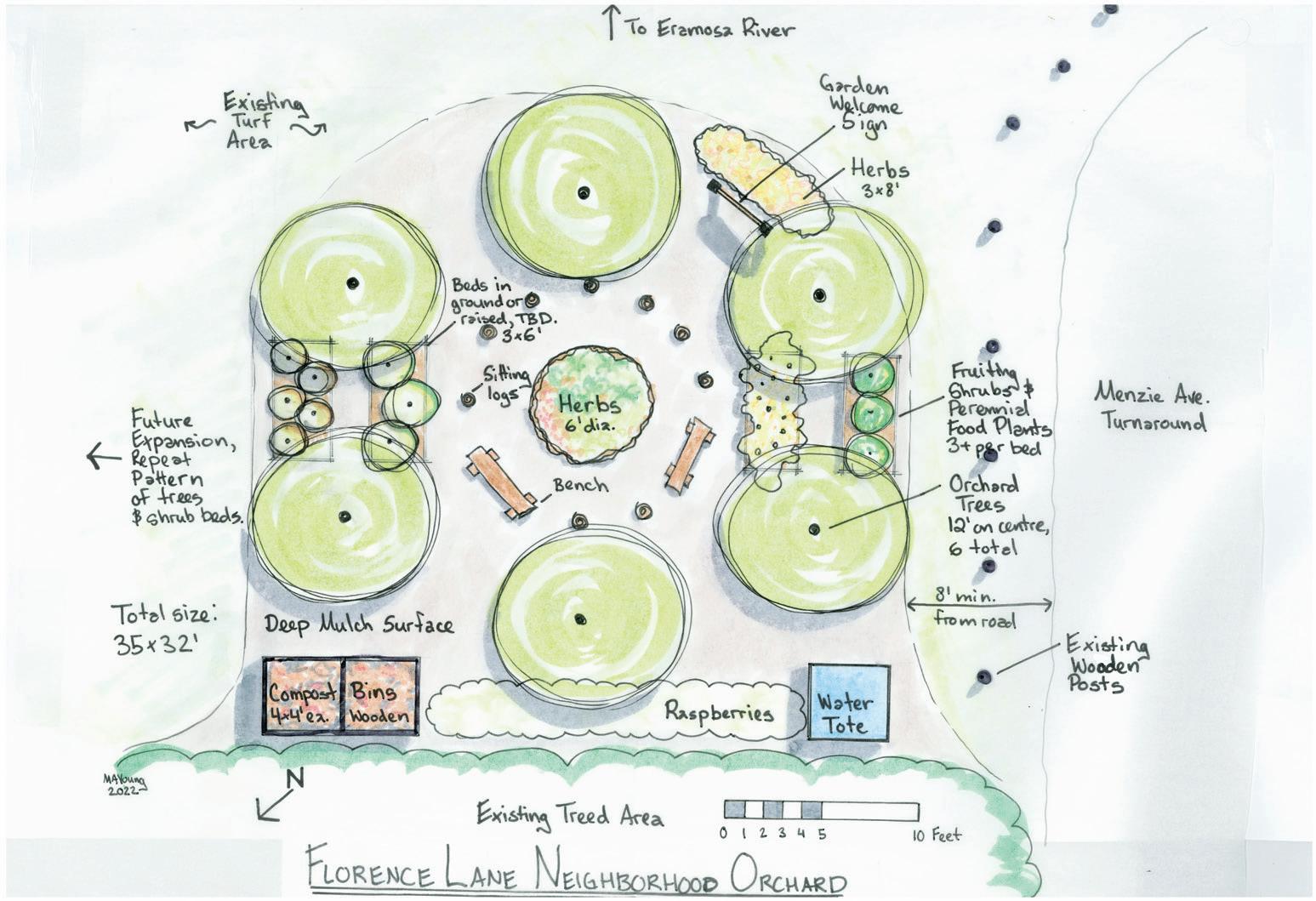

Ken Yee Chew: If I can just reflect on my election, everything I talked about in my platform was prefaced on improving quality of life and seeing how we can talk about design more holistically. Working for a municipality over the last three years, oftentimes it’s easy for us to work in silos. But the pandemic’s shown us we need to broaden our approach for how we define open spaces and we create value and justify funding capital projects—parks projects, for example. Speaking of the budget, City staff did put in funding for new parks and open space. At a micro-scale, there is a community garden we’re proposing at Eramosa River Park, and it’s the kind of small intervention we’re able to advocate for more

easily, without having the public question it, because the pandemic took place. There’s an intrinsic appreciation and value for our open spaces and the microcosms it creates in our environments, stuff we’ve been advocating for in our profession time and again, but it’s really cool to see how the public’s taken interest in projects like these.

Michael Tocher: In our day-to-day work, not much has changed. But, as Ken mentioned, it’s not as difficult now to convince certain members of the public why landscape is important. There has always been a group wondering why you’re spending so much money—on consultants, projects, or initiatives—and now there’s more acceptance that this is as important as roads, or other concerns. Now they understand.

GB: On the flip side, though, what are the current issues Ontario and the profession are facing, and how will these issues influence design and landscape architecture thinking?

EN: One of the issues that’s currently top of mind for everyone is the perception that, in order to have more homes, you have to somehow give up your green space. And what’s really interesting is that the public and a number of the stakeholders are quite unhappy with that choice. Why do we have to give up public lands to meet our housing needs? There are other ways of doing it, why aren’t those being explored? And why is this option being explored when other governments have set these lands aside for public use, or public benefit. That doesn’t seem to be a provincial government priority at the moment. So the value of having a greenbelt and what it takes to protect that is certainly top of mind for a lot of people right now because it’s being eroded. The conversation is a much louder and more informed one than it might have been in the past.

But thats always the risk. We think we’ve been able to move forward with the kind

09 Round Table .61

of policies and guidelines that will benefit the broader population, but they are at risk. We now all recognize that new housing is required. The question is what we, as a community, as a province, are going give up in order to achieve that? And is it just more homes or better communities that we’re really after? I haven’t seen that explained in a way that I think the public agrees with.

MT: This could be an unpopular comment, but I do feel like the development process is broken and there needs to be improvements. But it’s possible to make overcorrections, like with the greenbelt, that confuses the situation. When I read through the legislation and I try to understand what it’s saying, I see some corrections that may be based on feedback from developers, or even municipalities, who are trying to fix things so the development process isn’t so costly and time consuming. But I do feel it is an overcorrection, and it’s probably a ‘too much, too soon’ sort of thing. I can appreciate some of it may be a good idea, but it clouds the whole discussion by throwing everything together in one piece of legislation. And then it also raises the questions, what else is attached to this if you want to build homes faster? Who’s actually going to build the homes? Are there actually enough contractors and builders out there to do what the province wants to do? Or is it just going to be a bunch of land that’s approved and we’ll sit around waiting for someone to show up to move some earth around?

It has to be more comprehensive, and it shouldn’t be all on the development process to fix the problem. But there definitely are some issues there when it takes years and years to get some things approved, or they never get approved. We all know sites that should have had homes long ago, they sit on top of transit stations and it’s been vacant for almost 20 years, only because a developer couldn’t get a couple of extra stories on top to make it work financially. But whether or not this current legislation actually solves that problem, it’s hard to say. It’s not a perfect system by any means and it does need fixing, but this is really messy.

KYC: Also maybe an unpopular opinion, but a silver lining to Bill 23 and Bill 109 impacts that we’re seeing is there’s a real opportunity for us to talk about what really matters and what’s really important. I think, oftentimes, policy does need to be refreshed. And just being in urban design and planning and landscape architecture, it’s easy to be cynical and get frustrated because there’s been a lot of work that’s been put in over the years by planners and policy makers to craft the greenbelt the way it’s been. But, at the same time, we have an opportunity to talk about what really matters to us. And I think there are facets in the development review process that can be improved and done better.

03

IMAGE/ Mary Anne Young, OALA, CSLA

02/ Eramosa Park

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the City of Guelph, ON

03/ New planting by Silvercreek Trail, Guelph.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

04/ The Dairy Bush, University of Guelph.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

01/ Community garden concept design developed with Florence Lance neighbourhood.

10 Round Table .61 04

02 01

Obviously, it seems like there’s been a reactionary approach from the province and one could think it’s shortsighted as well just given that a lot of municipalities across the province haven’t been consulted. When Bill 23 came out, the day after the Guelph election took place, we were slammed with these proposals, and now we’re not quite sure what to make of planning at the moment. We kind of have our hands tied, just waiting to see what the impacts are going to be. The real crux of the matter is how do we actually address housing without compromising quality of life and the quality of our open spaces?

That’s always been an issue in Ontario when we have these kind of planning conversations. Compared to B.C., in Ontario we have a very dispersed land base. The broader public doesn’t necessarily have an understanding of what a wetland is, compared to prime agricultural farmland, or a farmland that’s in a holding pattern

for development. It all seems the same to most people. So I think there’s a public education component that the OALA can continue to advocate for and be a leader for a lot of these issues. There’s an opportunity, as well, for us to simply preface the conversation a bit differently, to funnel public sentiment and distrust into something more productive. We have an opportunity here to do that with the OALA.

GB: Do landscape architects need to develop new skills and knowledge, or build certain relationships, to be better positioned to address these kind of issues in the future?

EN: Yes, absolutely. What we’ve learned through our practice legislation pursuits over the last decade is that, 10 years ago, most people, particularly those in government, didn’t know we existed, other than to do kind of ancillary residential work. That was the impression people had. They didn’t really

05/ Highway 401 in the Greenbelt IMAGE/ Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Highway_401_Greenbelt.jpg

06/ Opponents of Bill 23 and expansion into the Greenbelt.

05/ Highway 401 in the Greenbelt IMAGE/ Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Highway_401_Greenbelt.jpg

06/ Opponents of Bill 23 and expansion into the Greenbelt.

06 11 Round Table .61 05

IMAGE/ Leah Gerber, The Woolwich Observer

understand the full value that our education and experience brings to improving, not only our natural environment, but our cultural heritage—all of those things. And it’s work. Our community of landscape architects has to do a better job of advocating for themselves. Our colleagues have incredible knowledge. They’ve gone through an extensive education. In many cases, they have unique abilities and special skills, and that has to be presented in a bolder and more evident way. So we do have to talk about these issues. We do have to speak out. We have to advocate for ourselves about our knowledge and really grow a voice and a backbone. It’s time that landscape architects actually did step out and help. We have, in the last four or five years, provided advice to this provincial government, whether it was about highways, or signage... there’s been a lot of things landscape architects have been more vocal about and have been at the table with other professionals. That’s something that needs to continue with the next generation of landscape architects, when Mike and I are no longer here, people need to be able to step up and talk about what it is we do that’s valuable, and how we can help. Because there’s no point complaining. You have to find a positive and

constructive way to help this government to move forward. It is incredibly important that we do take our seat at the table and we are able to encourage the government to understand our perspective and why what we can do will be helpful, generally.

MT: From my company’s perspective, we’re always looking for people with different talents, and not just a repeat of the same, which can be a big ask sometimes. As we grow, we’re trying to branch out and become more multidisciplinary. We do planning and landscape architecture. Our planning is mostly parks and rec master planning. But more and more we’re dealing with policy planning, and we don’t have that skill necessarily in house. We’d like to have a policy planner on the team to add that layer. And you can’t always just go outside and hire that consultant, because that’ll cost you a lot more than it would be to have that person internally. It’s the same with environmental engineering. We have people on our team that have experience in naturalization and restoration on staff, and those are people we didn’t have five, six years ago. Because we’re being asked to do so much more. We get what would’ve been a simple proposal or RFP to respond

07 08

07/ Diverse groups collaborate to create a sustainable future as part of the Accelerate Collaborating for Sustainability Conference in Guelph.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of The Natural Step Canada 08/ Highway 6, Guelph.

12 Round Table .61

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

to and write a proposal; 10 years ago, as a landscape architect, you could have just done it yourself, and now they layer in things about climate change or current legislation changes, and then there’s always a bit of engineering in there. So a firm has to be a jack of all trades, though you don’t necessarily have to be an expert in all those things. We always hear that we’re good at a lot of different things and not necessarily an expert in anything. I think that’s more true now than ever just because of how complex and interconnected everything is. That’s why continuing education is so important: to keep you up to speed on that.

KYC: We really have to take on a multidisciplinary approach when we think about design, and even how we can shape our profession from that perspective. I’m still relatively new to the profession. I only graduated three years ago from my BLA, and I found that, at the end of the day, we’re really just communicators and we need to be able to speak to different stakeholders, whether it’s members of the public, clients, development partners, or people within planning that speak policy. It’s important for us to just be that jack of all trades and also hone in your skillset. That’s something I’m continuously trying to get better at. I didn’t expect to go back to school so quickly, but I found it adds value if you can speak policy to folks that come from that kind of mindset, in order to get to an outcome.

It’s becoming harder nowadays, compared to my parents’ generation. My dad is a building designer and he does everything by pen and paper. Now you need a whole bunch of different consultants in order to actually get a project through the door. It’s

not necessarily a bad thing, it just shows how holistic our society’s becoming, how complex we are, and how intentional we are when it comes to getting a product out the door.

EN: Urban design is a place landscape architects need to be. We share that realm with architects on one end, sometimes urban planners on the other. But landscape architects are really important in the whole process of evolving our urban environments. And urban design is a place that landscape architects need to look at more closely.

GB: Are there new designs, processes, approaches, or best practices you feel will be most responsive in solving the issues we’re currently facing?

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

10/

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

11/

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

09 10 11

09/ Tree being moved in downtown Guelph.

Transit station, University of Guelph.

Condo development construction, Guelph.

13 Round Table .61

IMAGE/

14/

IMAGE/

KYC: To expand on the skillset landscape architecture practitioners provide. Being able to practice urban design is extremely important these days. Being able to use 3D visualization skills is extremely valuable. From my time in Brampton, I found if you’re able to draw out or model out something to a big group, it can cut the meeting time virtually in half, because a picture’s worth a thousand words, and oftentimes we want to be able to see the end results before we commit to an outcome. I found that to be extremely useful, and part of the evolution of our practice. We have to be able to pick up these new skills and branch off, and also model how intentional we are to different design disciplines, whether they’re engineers, traffic planners, or policy people. Everyone likes to see how they’re contributing to the end product.

MT: One thing the pandemic did for us is advance the willingness of the general public to embrace the technology that allows for virtual meetings, where you can get a bunch of stakeholders together without being in one room, they can do it from the comfort of their own home. In terms of engagement, you don’t just have to have your regular public meeting, you can engage the public from different angles. That is becoming a best practice: when we do respond to an RFP, we’re approaching it from multiple angles and trying to get as many people involved as possible. People always talked about it and tried to do that before 2020, but it’s a lot easier now. And there’s technology out there that is more accessible for everybody to use. You don’t have to be a big municipality with a

fancy platform. You can rent the platform for the duration of your project, post it on there, work with the community, and wrap it up when the project’s over.

EN: The difference of pre- versus postCOVID is the general ability of everyone to be able to try different things. It’s really important to come together again, but there are some segments of our work, some parts of a design process, that you can actually do more effectively. I personally like the ability to, for example, connect with a client much more frequently for 10 or 15 minutes, to be able to have an ongoing dialogue instead of waiting for a meeting with 30 people sitting around a table to try to explain where you’ve been moving. The ability to do that more effectively, more frequently, and more successfully is something we’ve learned how to do.

It wasn’t like that three years ago, it was awkward. It was having to get in your car and drive to Kingston or wherever, and you’d have the whole day to sit down with somebody for an hour and a half, and now you can sit down with three people at least on a call in that same period of time. That efficiency is good, but I don’t think it should entirely replace face-to-face engagement. Because, as Ken described, if you can be in a room and show someone on a screen and help them understand how design evolves, it’s incredibly powerful.

GB: In terms of maintaining the relevance and importance landscape gained in the pandemic, and ensuring landscape architects are still a big part of the

14 Round Table .61

12/ New tree plantings by Silvercreek Trail, Guelph.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

13/ Tree Planting Initiative sign, Guelph.

Ryan De Jong

Preservation Park, Guelph.

12 13 14

Ryan De Jong

conversation going forward, what are questions they need to ask of themselves in the profession?

KYC: I’m constantly asking myself how I can add value with my education, background, and my experience. The truth is it’s much harder to describe what landscape architecture is to most folks than it is to describe what engineering is. We still need to be able to demonstrate how our value is being added to most members of the public. There’s still an opportunity with our development partners to be able to educate and guide folks from the beginning of the design process to the end. We just have to be creative and evolve.

EN: We have to rise to the challenge. It’s not helpful to do the same things we’ve always done. The assignments are more complex and interdisciplinary. The lines between

what one profession and another does can be blurry at times. We shouldn’t be afraid to take a leadership position in those types of assignments. So to move forward, we have to show our metal, our ability and knowledge, and how we can be inclusive and integrative. These are skills we’ve all learned, whether it’s in university, a design studio, or in the working world. We just have to keep doing it really well. You have to take some measured risks, be collaborative, and take the lead when you see the need.

MT: We lead a lot of projects. When you’re the project lead, it gets pretty exhausting. I’ve almost fantasized at times just providing landscape architecture services. But that’s such a small part of what we do.

And it can be hard to say to an engineer, “Hey, this is important. You should be listening to me even though I’m not an engineer, but this is what I think we should do.” But maybe that’s where we really have to make change.

I don’t have to worry about that as much because usually when I hire an engineer, their scope is pretty defined and they’re happy to stay within those bounds. But very often we’ll get into work that is bordering on engineering and we don’t have an engineer on the team and we’ll have to finesse our way around it so we can do what’s right,

and it’s safe, and we’re not negatively impacting the environment. But it’s still landscape architecture—just at the edges of engineering or whatever other discipline we’re working with.

EN: It really requires you to stay on your game. You have to work with some intensity, you have to have integrity, and you have to try to find the best possible solution. It’s not easy, but it is rewarding when that happens. And it’s important to at least strive to do the best you can, and deliver good quality work. There’s discipline required. I really like working on a big, collaborative, interdisciplinary project because I learn so much.

One of the nice things about being a landscape architect is you have conversations with other professionals and it’s a huge learning curve you can apply to other things.

There are some projects where we can make an unbelievable difference to the outcome, and others where it’s really hard to influence where things go, but we should never stop trying.

15 Round Table .61

15/ Beaumont Park, Toronto.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

16/ Preservation Park, Guelph.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

17/ Speed River, Guelph.

16

15

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

17

THANKS TO SARAH MACLEAN AND HELENE IARDAS, OALA FOR COORDINATING THIS ROUND TABLE.

16 Mental Health Reflections .61 02

TEXT BY SHAHRZAD NEZAFATI, OALA AND TRACY COOK

Designing outdoor spaces for health and healing has often been a specialized part of the landscape architecture profession. Designing specifically for winter cities with consideration for mental health criteria is an emerging area of research. The results of this research were starting to find their way into the design guidelines of different cities, especially those with longer winters and colder climates, pre-COVID.

When COVID descended on the world, Canadians flocked to their outdoor spaces to maintain healthful, safe social contact. Outdoor spaces became meeting places in all kinds of weather.

Many homes were not designed for the modern live-work arrangement, not to mention families spending their days glued to screens in meetings, work, and school. We all found creative ways of using our outdoor spaces to survive these challenging times. If you were lucky enough to have a private outdoor space, it was likely enhanced with furniture, fire pits, and planters for seasonal colour.

Public open spaces became great options for work, exercise, and social engagement for people without access to private space through all four seasons. This experience was the beginning of new park users with different needs, and a critical question emerged along these new experiences: are our local outdoor spaces and parks designed and programmed with flexibility, mental health criteria, and winter in mind?

A recent article in the Guardian suggests “visiting green spaces deters mental health drug use. Visits to parks, community gardens and other urban green spaces may lower city dwellers’ use of drugs for anxiety, insomnia, depression, high blood pressure, and asthma. Moreover, the researchers found the positive effects of visiting green spaces were stronger among those reporting the lowest annual household income. The findings correlate with growing evidence that a lack of access to green spaces is linked to various health problems. Access tends to be unequal, with poorer communities having fewer opportunities to be in nature.”

17 Mental Health Reflections .61

01/ Winter Stations at Woodbine Beach IMAGE/ Mary Crandall / Flickr

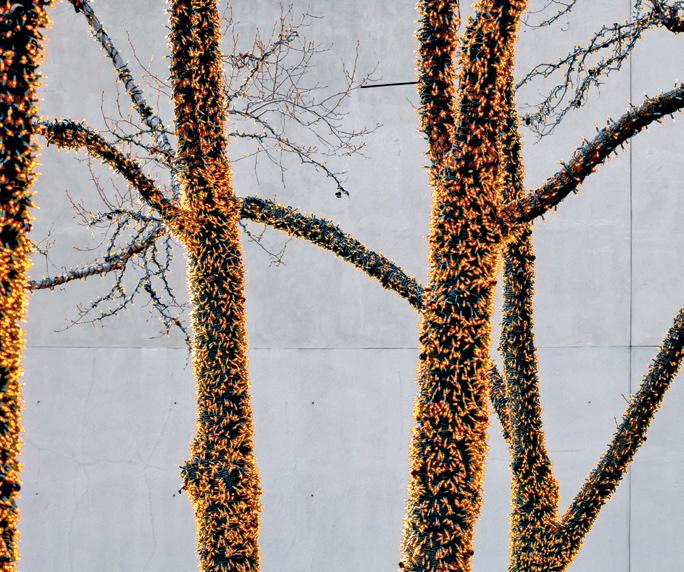

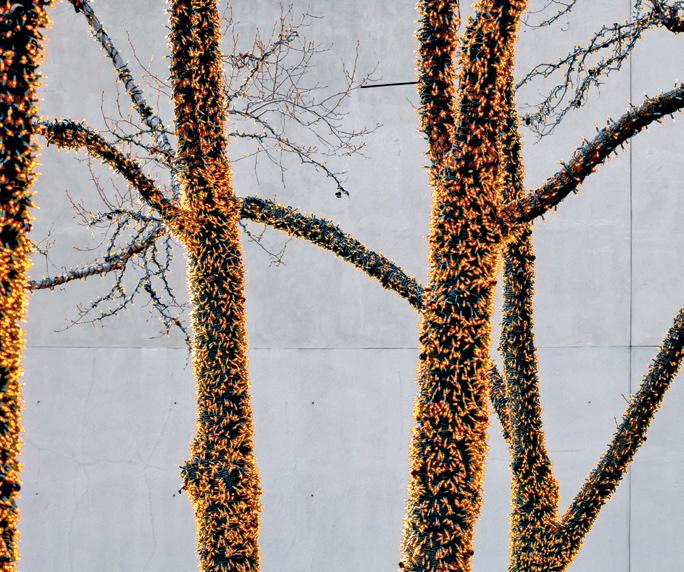

02/ Bare trees in winter covered with string lights IMAGE/ Jo Sullivan / Flickr

03

03/ Skaters on the trail across the rail bridge in the Arctic Glacier Winter Park at The Forks, Winnipeg IMAGE/ Lorie Shaull / Flickr

World Landscape Architecture (WLA) issued an article about how parks are vital to maintaining mental health in March 2020. The article suggests COVID closures (and people’s inability to physically distance) have highlighted the “need for residents to have access to open space within walking distance. Large regional parks often became overcrowded during COVID, highlighting the need for smaller neighborhood parks and even opportunities to gather on streetscapes— either on widened pedestrian areas with incorporated seating or in outdoor cafes. Residents must have access to green space within walking distance.”

While another winter is now behind us, we want to encourage everyone in the Landscape architecture profession to take this current enthusiasm and appreciation for our parks and outdoor spaces, engage the public in design decisions, and conduct surveys to document how people utilized outdoor space during COVID. How can the design of green spaces improve to assist society in this healing process and plan for more vibrant and practical landscapes throughout communities? This could lead

us to quality outdoor spaces designed with criteria and programming focused on mental health in winter cities. Design criteria need to facilitate the creation of safe and comfortable spaces for people to use daily and year-round.

Unique to our Northern climates in the winter is the need to seek the sun and shelter from the wind—quite the opposite of a warm summer day where you may seek shade and a breeze to keep cool. Going back to the basic inventory, opportunities, and constraints bubble diagrams may help us to identify areas of winter activity vs. summer activity. These sun and shade studies can become particularly helpful when considering outdoor spaces on podiums or adjacent to tall buildings. This is essential when we look into sun exposure, its impact on mental health, and the science behind it.

In winter climates, we lose the vibrancy of colour—our trees lose their green leaves, our lawns become brown, and our skies become grey. Colour and its role in creative lighting, paving, and furniture design can be a valuable tool in winter

18 Mental Health Reflections .61

04 05 04/ Toronto’s snow covered Sugar Beach in February IMAGE/ Roozbeh Rokni / Flickr 05/ Colorful outdoor furniture in winter IMAGE/ Sean O’Connor / Flickr

cities that call for more mental health support. There is extensive research on the impacts of colour on human psychology and mood, which should be a permanent part of design criteria in winter cities and approval processes.

Light and heating can play a significant role in making winter spaces accommodating to year-round use. The much shorter days of winter limit the useable time in unlit parks. Park lighting can be playful or utilitarian, temporary or permanent, but adding light to outdoor spaces will allow for extended seasonal use and a sense of safety. Heat is an element that extends our enjoyment of winter parks. Many cultures have a tradition of outdoor fire pits and warming huts—the opportunity for winter festivals and programming which can significantly impact the sense of belonging and inclusion and improve mental health.

Considering these design criteria when we design outdoor spaces for winter cities at the beginning of the process will offer more opportunities to gather, socialize, and connect to nature—all critical elements for maintaining robust mental health.

06/ A skater on the trail in the Arctic Glacier Winter Park at The Forks, Winnipeg

IMAGE/ Lorie Shaull / Flickr

07/ Winter Trails

IMAGE/ Lorie Shaull / Flickr

08/ Skating at frozen Rideau Canal in Ottawa

IMAGE/ Cynthia Zullo / Flickr

This article intends to start a conversation about how COVID naturally created the necessity for designing every outdoor space—not necessarily just hospitals and healing clinics—to help improve mental health, especially in cold climates. We see a significant value in reviewing the basic design criteria with a mental health lens as a starting point for this conversation. The next steps may be looking into design guidelines and approval processes and exploring the best ways to include this essential design consideration in our winter city designs.

BIOS/ TRACY COOK, BLA, ISA, TRAQ, MOM, WORLD TRAVELER, NATURE LOVER, (NOT ALWAYS IN THAT ORDER). SHE IS A MEMBER OF THE GROUND EDITORIAL BOARD.

SHAHRZAD NEZAFATI, BARCH, MLA, OALA, CSLA, IS A LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT WITH A DEMONSTRATED HISTORY OF WORKING IN THE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND ENGINEERING CONSULTING INDUSTRY. SHAHRZAD MAINLY FOCUSED ON BUILDING STRONG CLIENT RELATIONS SKILLS BY UNDERSTANDING USER AND CLIENT NEEDS AND PROVIDING THE BEST SOLUTIONS AT THE BEGINNING OF HER CAREER, AND IS CURRENTLY FOCUSED ON SUSTAINABLE AND INCLUSIVE DESIGN AND RESEARCH. WORKING ON PARKS CANADA PROJECTS AND WITH INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES WITH GREAT INTEREST IN THE ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECT OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE, ACCESSIBILITY, AND USER EXPERIENCE.

19 Mental Health Reflections .61

06 07 08

20 Resilient Plants of Ontario .61 01

A Short list of Hearty Heroes.

For millennia, the plant kingdom has been critical to human survival, offering us the gifts of shelter, food, and medicine. Beyond sustaining human beings, plants play a fundamental role in developing and maintaining complex ecosystems to support life. Today, the Grand Forest and the Carolinian Forest have been modified by colonization to suit the needs of modern life, and many of the native plants, rooted there for centuries, have been displaced. Native plants have been acclimatizing to a changing climate for centuries and continue to support our livelihoods. First Peoples (then and now) and settlers have relied on our native plants to sustain our ecosystems, feed us, grow our communities, and contribute to economic productivity. Let us not forget some of the plants that shape our daily lives, and let us continue to ensure their success across our landscapes.

02 03 04 21 Resilient Plants of Ontario .61

TEXT BY MATTHEW LUNDSTROM

01/ Wild rice

IMAGE/ Courtesy of James Dieme

02/ Moss

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Jennifer Qian

03/ Cedar tree

IMAGE/ Matthew Lundstrom

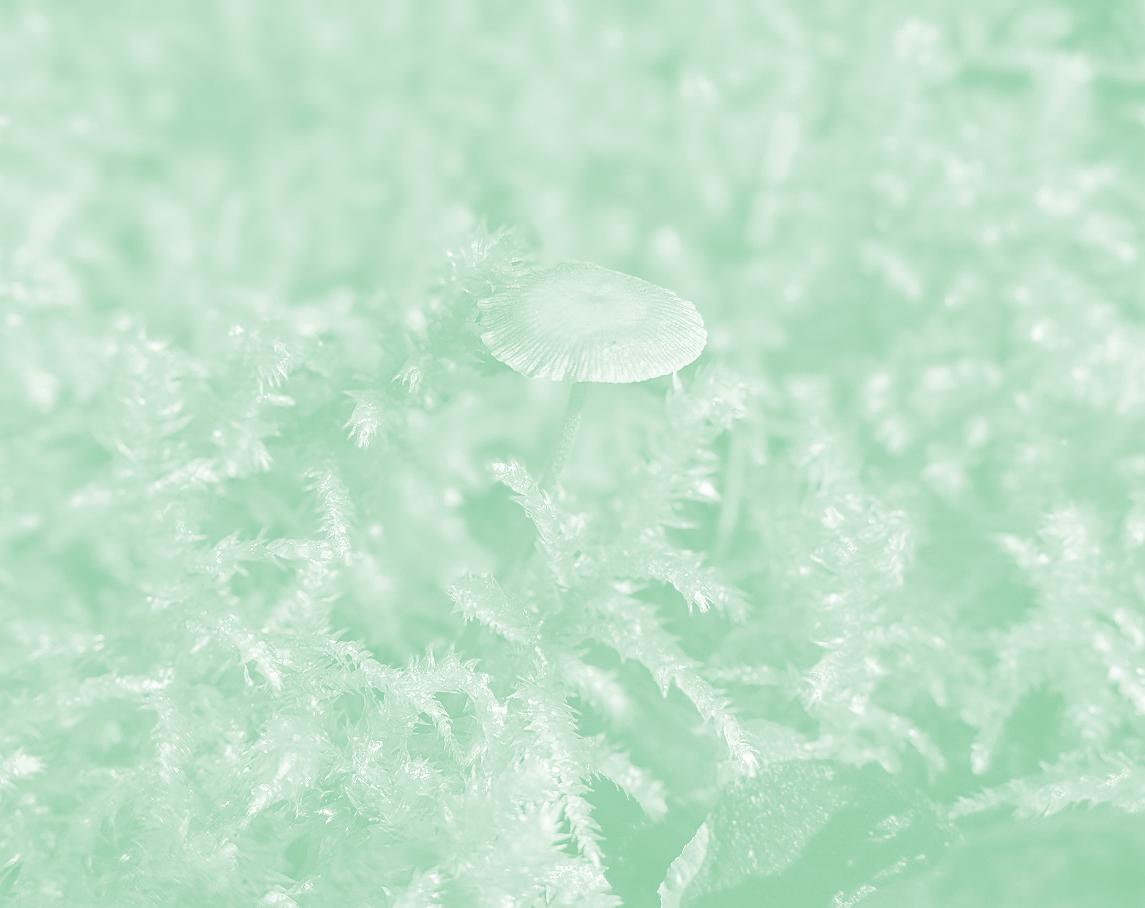

04/ A mushroom growing out of moss.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Jennifer Qian

The genus of moss, has an incredible diversity of species found across the world with many species native to Ontario. Moss is a foundational element for all plant life, and it has been around for millions of years. Surely, we can learn something from an organism this experienced on Earth. Moss works to store water, moderate air temperature, and colonize mineral surfaces, inviting emergent plant life. Canada has an abundance of moss and a rich history of different utilizations—from medicine to pillowcases. Today, moss is an important resource for peat production and climate mitigation. A humid and shady environment is a perfect invitation to cultivate moss on limestone, and other hardscaped surfaces. Moss can make a project looked lived in, cool hot temperatures, and feels great on bare feet.

22 Resilient Plants of Ontario .61

Moss (Sphagnum)

05/ Moss

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Jennifer Qian

06/ A mushroom growing out of moss.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Jennifer Qian

07/ Local fauna, wiggling through the moss.

05 06 07

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Jennifer Qian

Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

Also known as muckode’kanes by the Anishinaabe, this is a tall grass native to Southern Ontario’s landscape. The handsome, upright, blue-green bunch in the summer turns into a rich bronze as fall temperatures creep in. Big bluestem can grow between four and eight feet tall, and its root system can dig down to three meters in depth, storing carbon and improving the soil network. Due to urbanization and agriculture, the tall grass prairie is a fraction of what used to be. Landscape architects can incorporate this tall native grass into planting plans as a drought-tolerant species, with its bronze colour creating winter interest. The grass is also a habitat for many Lepidoptera species (butterflies and moths), and can make a great placement in a pollinator garden. The success of this native grass depends on its continued spread. Think of big bluestem before you plant silvergrass (Miscanthus)

08/ Andropogon Gerardii II

IMAGE/ dogtooth77, https://flic.kr/p/2jyduSd, Some Rights Reserved

09/ Andropogon Gerardii

IMAGE/ Matt Lavin, https://flic.kr/p/y9Mpjr, Some Rights Reserved

10/ Big bluestem on a misty morning.

IMAGE/ Philip Brewer, flickr.com/photos/ bradipo/, Creative Commons Licence

23 Resilient Plants of Ontario .61

09 10 08

Manoomin (Zizania palustris)

Also known as wild rice, this is a native grain-producing grass in Canada’s Great Lakes region that has survived colonization and urbanization. Manoomin is an annual that requires quiet, shallow water to breach the surface and develop its seed head. This seed head, traditionally harvested by canoe, is a local food source and a spiritual plant of the Anishinaabe peoples. Manoomin has many challenges to continued success, as hydroelectric dams and motorized boats threaten the plants lifecycle. Despite these challenges, Indigenous peoples, namely the Anishinaabe, and settler allies are rallying for the protection of the native grain throughout the Great Lakes watershed. The continued spread of Manoomin will provide more food security and habitat for endemic and migratory species throughout the Great Lakes region.

24 Resilient Plants of Ontario .61

11-13/ Wild Rice

11 12 13

IMAGES/ Courtesy of James Diemer

Eastern White Cedar (Thuja Occidentalis)

This is also known as Arborvitae, the “tree of life.” White cedar is a softwood coniferous tree that grows mainly in rocky and wet areas, slowly reaching as tall as 50 feet. These slow-growing natives have also been discovered along the Niagara Escarpment— some as old as 500 years. Cedars are an important forage for wildlife and have high value as lumber. The trees have been cut down for generations and used as building materials due to their lightweight and antimicrobial nature. Due to their slow growth, maintaining cedar populations is a worthy investment to develop wood lots in Southern Ontario. Given the topography, the Canadian Shield provides a unique environment for white cedar to thrive. While the tree has ecological value, the economic value of cedar trees can create financial resilience in our communities.

Sugar Maple (Acer Saccharum)

This is a deciduous tree native to Canada’s eastern hardwood forests. Average heights can reach 100 feet tall, with exceptions growing as high as 150 feet. Sugar maples strengthen plant communities by bringing water from lower soil layers and dissipating it to the upper, dryer layers. This process, known as hydraulic lift, hydrates the tree and the surrounding vegetation. As water scarcity and drought continue to be ecological threats, sugar maples can be a solution to improve hydrology and encourage stronger plant networks. The largest challenge facing sugar maples is their non-native competitor, the Norway maple. Tolerating disturbed soils and producing heavy seed loads makes the prospect of planting a Norway maple a good one. However, this trend threatens the resilience of a culturally significant species.

25 Resilient Plants of Ontario .61

THE

OF

MEMBER.

BIO/ MATTHEW LUNDSTROM IS AN MLA STUDENT AT

UNIVERSITY

GUELPH, AND GROUND EDITORIAL BOARD

17 16 15 14

14-17/ Sugar maple IMAGE/ Matthew Lundstrom

26 Grounding .61 01

On the way up to the Limit in Kitigan Zibi, there’s a little bog by a lake. Medicine plants grow there. Sun, soil, and water create a spot from which staples grow for Catherine Cayer, knowledge keeper, to make mashkiki (or medicine) the Anishinabe way.

“If you notice all the medicines we picked, they all grow together. They reciprocate. They help each other out. They work together,” says Cayer, after our autumnal medicine walk in the little bog. “It seems like every time you need a certain medicine—it’ll be all there—whatever you need for that ingredient for that tea.”

Thirty years of medicine walks with her mother-in-law, her grandfather, and other elders now gone gave Cayer her knowledge.

As our walk starts, Cayer points out an existing scrape on a hemlock tree she made to gather its bark. We step cautiously, hoping not to sink in the marsh. Nearby grows creeping snowberry, Labrador tea, goldthread, wintergreen, and goldenrod.

Creeping snowberry grows close to the hemlock. Cayer makes tea with creeping snowberry and hemlock bark to cleanse the lungs.

She stoops, picks Labrador tea, and makes a bouquet.

“They used to make that a long time ago. Say there is a death in the family, they would make tea to help them relax and help them sleep,” she says. That’s how the remedy was passed down through generations.

Labrador tea and wintergreen work together. The round, waxy leaves of wintergreen taste like peppermint. Anxiety may cause nausea. Labrador tea calms the anxiety, while wintergreen calms the stomach.

Stepping further, Cayer digs a clump of dirt from which the legs of goldthread sprout. Goldthread, an antibiotic, combined with hemlock bark and creeping snowberry, works as a lung medicine.

Goldenrod grows nearby. Mixed together with horsetail, their tea helps bladder or urinary infections. Plants grow together in their ecological niche. The pH balance of soils and water is right for this niche of plants.

Growth in the little bog makes things easier on the gatherer.

“That’s nature’s way of making sure you’re picking what’s needed. If somebody’s sick and somebody has to go get medicine, it’s a matter of time. You have to get something fast to cure them, to help them. You can’t spend a whole day going from one end of the reserve or one end of the forest to the next to gather. It would take you forever to get the medicines,” says Cayer.

Everything is meant that way for a reason because, when making medicine, time is of the essence. It’s all there. A right combination of earth, water, and sunlight make a place to gather plants for many remedies.

When she gathers there, she has purpose.

“I’m thinking of the babies that need it. I’m coming home, I’m going to have medicine for the babies. I’m going to have medicines for the people that have problems with their throat, their sore tooth. I’m thinking of many ways this medicine will be used. It seems to me like what’s all there, the bog, it’s almost everything

that’s necessary for my main staples of medicines,” she says.

The bog is a necessity.

“It’s not just any old plants growing there. It’s only those medicines. They’re all there together. There’s nothing else that you see there—just those,” she says.

In the small bog, the medicine plants and the hemlock trees neighbour each other and, like good neighbours, they work together.

IMAGE/

27 Grounding .61

03/ Near the hemlock tree and creeping snowberry grows Labrador tea which Cayer gathers in a bouquet.

IMAGE/ Millie Knapp

04/ Sunlight showcases creeping snowberry in Cayer’s hand.

03 04 02

Millie Knapp

BIO/ MILLIE KNAPP, ANISHINABE KWE, WRITES ABOUT ARTS, CULTURE, AND MINO PIMADZAWIN, THE GOOD LIFE.

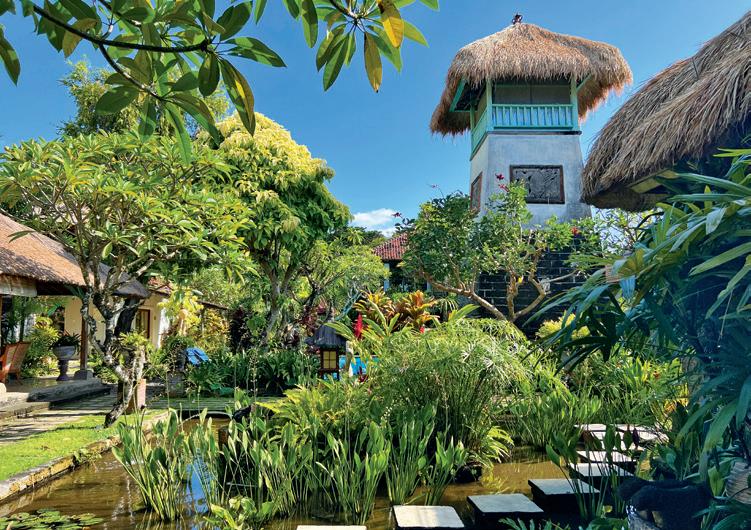

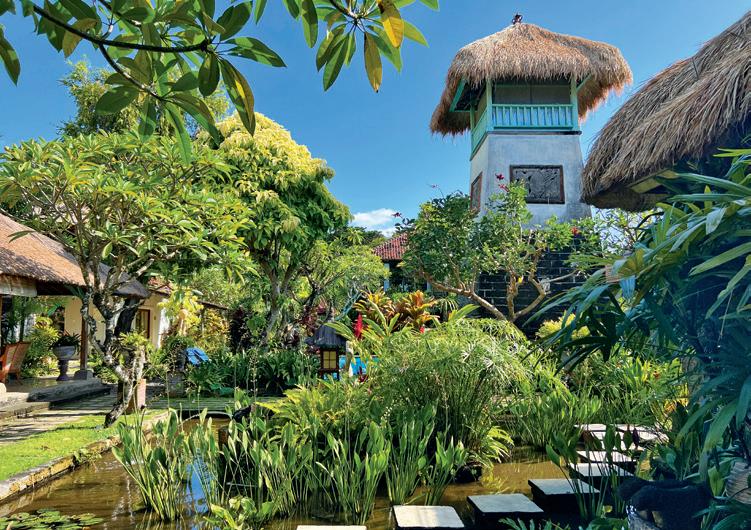

In the early 1970s, Michael White, an outgoing and adventurous Australian tennis player/architecture student made his way across the ocean to a small, magical island known as Bali, and never looked back. Michael networked his way into Balinese society, first in the realm of tennis or English lessons, and eventually found a home within the spiritual design of Balinese gardens. Falling in love with the island and rich culture, he was reborn as Made Wijaya.

It’s early morning at Villa Bebek, the former private home of Made, a safe haven for creatives and garden aficionados tucked away in a quiet corner of the normally bustling town of Sanur. His strong spirit still vibrates through the hidden green

01 02 03 28 Letter from... Bali .61

TEXT BY JASMINE NIHMEY VASDI

corners of the property, even though Made himself unfortunately passed away far too young after a battle with lymphoma in 2016. The private property, converted into guest cottages in recent years, serves as a time capsule for when Villa Bebek was a hotbed for fans and friends of Made Wijaya’s trademark tropical garden designs and flamboyant personality.

Leaving behind a somewhat conservative scene in Australia, Made’s fabulous persona was embraced on the island. His cross-dressing performances of traditional Balinese female dance routines were a hit and he became both a botanical sensation and wellknown personality who started to shake the entertainment world abroad. He flourished in a space with no creative limits and began an intense interest in the curation of tropical gardens, with the addition of Balinese stone sculptures and, often, Hindu shrines or altars. His first commission was for the Hyatt Resort in Sanur, a prized gem of the Sanur Coast. He managed a large team of gardeners and artisans to create a majestic space filled with ponds, flowering tropicals and palms framing the beach views.

The Sanur Hyatt has obviously grown and changed over the years, but the impeccable gardens throughout are something to marvel at. I spent one

01/ Pathway into Made’s office, Villa Bebek.

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

02/ A quiet corner with a water fountain.

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

03/ A garden watchtower.

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

04/ The swimming pool.

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

05/ A Koi pond beside a common garden.

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

06/ Koi pond pathway.

06 04 05 29 Letter from... Bali .61

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

morning enjoying brunch by a koi pond there and toured the property. Nowadays, it’s difficult to discern which designs were made by Made Wijaya and which are new additions, and most of the team who worked with him has moved on from the bygone era. But it is still a tropical paradise: in every corner you can find a perfect spot to hide away with a book or enjoy a bird of paradise fever dream pathway. Made went on to curate gardens at some of the island’s biggest hotels, such as the Amandari, Four Seasons Jimbaran, Oberoi, and more. He brought Balinese gardens into the mainstream, designing gardens around the world for Mick Jagger, David Bowie, and others. He also contributed heavily to the design of Naples Botanical Garden in Florida during its construction. All the while employing a team of highly talented Balinese artisans back on the island and supporting the local culture and community.

30 Letter from... Bali .61

07/ Author’s breakfast view at the Sanur Hyatt.

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

08/ Birds of paradise provide an archway for this path.

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

09/ A palm garden.

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

10/ The Hyatt koi pond.

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

11/ The Hyatt balconies, covered in greenery.

07 08

IMAGE/ Jasmine Nihmey Vasdi

Although those years have long gone— even the concierge at Villa Bebek is unfamiliar with the fame that once held the Villa and its charismatic owner—the lobby walls are still lined with celebratory photos of the botanical patriarch, posing with Balinese celebrities and dear friends. The years since have faded the photographs into a sunwashed sepia, as if looking into the lens of a past life. His office remains untouched at the centre of the property, overlooking the garden as it fills with sunlight every morning. Sifting through the stacks of his books (which are signed and for sale) and various papers there, you can still feel his energy and contagious laughter.

As time went by, Sanur turned into a hotspot for tourists looking to do nothing much besides enjoy the perfect beach and possibly attempt surfing a wave or two. Its boardwalk is lined with hotels, some private homes, and many cafés catering solely to the tourism industry. You can rent a beach chair and relax alongside the colourful traditional Balinese fishing boats lined along the shore, get a massage or a coconut, or browse through stacks of sarongs.

Villa Bebek provides an oasis away from the busy boardwalk, but is just close enough if you care to venture out for a stroll. The gardens themselves thrive with occasional visits from friendly and slightly adopted stray dogs and cats, and content birds who convene, sharing their stories between the frangipani trees every morning. Any fallen frangipani are gathered for ritual offerings, placed carefully in front of the many shrines throughout the guest cottages. Weeping flowers, like the flowering beach spider lilies that were in full force during my visit, provide privacy between ponds. Carefully placed stone paths connect each cottage, in case you want to gossip with your neighbour as the scent of breakfast wafts over from Warung Bebek, the restaurant overlooking the garden/pool. Walking through the Balinese doors that divide the cottages, a warm shiver tickled my shoulders. Possibly a palm frond, or a friendly welcome from a landscaping legend, into a sanctuary of what once was, but still continues to be.

31 Letter from... Bali .61 BIO/ JASMINE

TRAVEL

IN AMSTERDAM

SHE WRITES FOR THE GARDENER, BROCCOLI, AND OTHER PLANT-BASED PUBLICATIONS. YOU CAN READ MORE OF HER WORK ON HER SUBSTACK, GOSSIP AMONGST FRONDS, OR FOLLOW HER TRAVEL ADVENTURES ON MOST SOCIALS @JASMINETHEGARDENER.

NIHMEY VASDI IS A CANADIAN GARDEN

WRITER BASED

(NL).

09 10 11

Notes: A Miscellany of News and Events

awards

On June 8th, from 4-8 p.m., join us at The Loft in the Distillery District for a celebratory event.

Beginning with a walking tour led by David Leinster, OALA, and Michael OrmstonHolloway, OALA, who have been working with the owners of the Distillery District since 2003 helping to create a four-season public realm that seamlessly integrates the new development projects with the existing heritage fabric. This tour will be jointly given by the landscape architects, and joined by Jamie Goad, an owner, architect, citybuilder, and visionary. After the walking tour, we will gather on the outside, for drinks, canapes, and entertainment. We will then move inside for the awards ceremony, and volunteer acknowledgement, followed by entertainment.

The event’s program includes:

• 4:00 pm - 5:15 pm - Walking tour

• 5:30 pm - 6:30 pm - Outside - patio reception with entertainment

• 6:45 pm - 7:15 pm - Inside awards ceremony

• 7:15 pm to 7:45 pm - Entertainment

Tickets for the evening are $25.00, and you can register at: oala.ca/events

books

Pierre Bélanger, OALA, alongside Ghazal Jafari, and Pablo Escudero have published a new book called A Botany of Violence. It is a richly visual book which details the history of the South American cinchona plant, which is used to make the anti-malarial drug quinine. From this starting point, it traces a history of colonialism and resistance that spans 529 years, and touches on communities over the world.

It was recently reviewed in Places Journal, which called it “a gripping, multimodal investigation of six centuries of rapacious environmental imperialism that slaughtered millions and laid vast territories to waste.”

It’s published by Goff Books, and you can find it at: goffbooks.com/products/ botany-of-violence

01

01/ OALA Honours. IMAGE/ Courtesy of OALA 32 Notes .61

Join The Park People Conference, June 21-23, 2023 in Toronto for Canada’s only city parks gathering of community park group leaders, non-profit organizations, government staff and park professionals. It’s a stellar lineup including Akiima Price’s keynote presentation on the success of Friends of Anacostia Park, a National Park with some of the greatest income disparities and health inequalities in the U.S. A panel discussion on the budgetary, political and technical issues behind ambitious downtown park projects like The Bentway, University Park, and Corktown Common. And, a first look at The Port Lands Flood Protection Project creating a new alignment for the mouth of the Don River, including 30 hectares of new parkland and river valley habitat.

Visit parkpeople.ca/conference to see the Conference lineup and register.

new members

Ontario Association of Landscape Architects is proud to recognize and welcome the following new members to the Association:

Kevin Arthur

Nadine Bohner

Hillary DeWildt

Lauren Dickson *

Rachel Fraser *

Reinaldo Jordan

Brennan Guse *

Andrei Micu

Audric Montuno

Raj Patel *

Nicholas Stumpo

Victoria Walsh

Samar Zarifa *

Asterisk (*) denotes Full Members without the use of professional seal.

in memoriam

Barbara Magee Turner, OALA, CSLA

OALA is saddened to announce the passing of Barbara Magee Turner on February 2, 2023. Barb had been a full member of OALA since May 1990. The Association was notified on February 6, 2023.

Barb’s colleagues at the City of Waterloo prepared an announcement highlighting her contributions to the profession:

It is with deep sadness and regret that we learned about the passing of a valued former member of City Staff, Barb Magee Turner.

Barb joined the City of Waterloo in 1991 after working as a landscape architect in the consulting sector. She held various roles with the City over the years, working from both the Service Centre and City Hall. Throughout her 28-year career with the City, she contributed to the Barrel Warehouse Park; The Uptown Public Square; King Street Streetscape; David Johnston Research + Technology Park; Waterloo’s Parkland Strategy; Numerous neighbourhood park designs; and Wonders of Winter, to name a few.

Barb also led the way with the establishment of Waterloo’s “Spruce Up Your City” program, and was recognized for her incredible work by OALA and received the Public Practice Award.

Barb will be missed by her colleagues and landscape architectural community. Barb leaves behind her husband Richard and two children, Andrew, and Courtney.

03 02 04

IMAGE/

03/

IMAGE/

04/

IMAGE/

33 Notes .61

02/

Pharmakina Cinchona Plantation, 2017 (Bukavu, Democratic Republic of Congo).

Abby Ross

Book Cover

OPSYS Media, design

Indigenous Uprising, 12 October 2019 (Quito, Ecuador). IMAGE/ David Diaz Arcos 05/ Barbara Magee Turner.

Courtesy of OALA

conference

05

Create a

Playfulexperience

PAVILIONS | PERGOLAS | SAILS | ARTSHADES TM BUTTERFLY w/ 12’ Wing Span (0334) Elevate your design with iconic shade structures inspired by nature. Spec today at openspacesolutions.com | shadeview.com 519.580.7053 | janet@openspacesolutions.com ® METAL PARK STRUCTURES lu ti in Ontario Representatives

CITIPLEX TAKE IN THE VIEW EBY FARM PLAYGROUND | WATERLOO CITY OF WATERLOO | KELLY HARRINGTON, LANDSCAPE TECHNOLOGIST SNOW LARC LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE LTD. | STEPHANIE SNOW OALA, CSLA GENERAL CONTRACTOR | 39SEVEN INC. PLAYGROUND | OPENSPACE BY JAMBETTE SHADE BUTTERFLIES | OPENSPACE BY SHADEVIEW STRUCTURES for more inspiration, contact: Openspace Solutions Inc. 1.519.580.7053 | 519-699-PLAY janet@openspacesolutions.com www.openspacesolutions.com

It’s Mighty Fun

Distinctly Playful

The Mighty Descent slide is a daring new play experience from Playworld! This massive slide is extra wide and lets many children experience the fun of sliding together. Mighty Descent is the first of its magnitude that’s not solely a hillside slide, although a hillside version is available. Add big fun to your next play space design with Mighty Descent!

Bring authenticity to your playground’s adventures through sculpted play elements! Constructed from glass fiber reinforced polymer, these bold additions are lighter in weight and easier to install than concrete while maintaining the same quality durability, UV-stability, and fade-resistance. Whether they leap with the frogs, soar with the birds, or even pollinate with the butterflies, our sculpted play elements ensure kids can accomplish whatever they set their mind to.

our website for more information:

New World Park Solutions P: 519.750.3322 • F: 519.304.3905 newworldparksolutions.ca • Info@newworldparksolutions.ca

Visit

www.playworld.com

Playworld Systems, Inc. is a PlayPower, Inc. company. © 2021 PlayPower, Inc. All rights reserved. New World Park Solutions P: 519.750.3322 • F: 519.304.3905 newworldparksolutions.ca info@newworldparksolutions.ca Playworld Systems, Inc. is a PlayPower, Inc. company. © 2023 PlayPower, Inc. All rights reserved.

Visit our website for more information: Playworld.com

SHADE REI MAGI NED • Custom Shade Structures • Polycarbonate Roof Panels • Integrated Heating & Lighting • Professionally Engineered • Durable Aluminum Build 800-268-7328 sales@hausersite.com HAUSER SITE FURNITURE www.hausersite.com

Presidio Tunnel Tops Outpost San Francisco, CA Collaboration: Partnership for the Presidio, James Corner Field Operations info@earthscapeplay.com | 1.877.269.2972 earthscapeplay.com PLAY DESIGNED BY NATURE PART OF THE Nueva® Collection Nueva® 150 Wall OAKSpavers.com | 1.800.709.OAKS (6257) Versatility, strength and good looks for your most challenging applications!

Thursday, June 8, 4:00

The Loft18 Tank House Lane, Toronto

01/

IMAGE/

02/

IMAGE/

Such opportunistic plants that grow in nooks and crannies are known as spontaneous vegetation. Some may call them weeds, but public perception is changing. Recent studies have shown an increasing appreciation for a ‘wilder’ aesthetic in built spaces. Specifically, research in France has shown that pavement areas with spontaneous vegetation are preferred over highly managed pavement without vegetation. They are perceived as less kept, but more beautiful and less boring.

nature in everyday urban life, improving the mental health and sense of well-being of communities. Not to mention, there is something subtly inspiring about seeing a plant grow from a small crack in pavement.

In an increasingly urbanized world, these small moments add up. We need more parks and greenspaces, but the small spaces in between matter too. Just let it grow.

BIO/ RYAN DE JONG IS A MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STUDENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH AND GREW UP WORKING ON HIS FAMILY’S NURSERY NEAR VANCOUVER, B.C.

BIO/ RYAN DE JONG IS A MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STUDENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH AND GREW UP WORKING ON HIS FAMILY’S NURSERY NEAR VANCOUVER, B.C.

01 02

Poppies growing in Okanagan Valley, B.C.

Ryan De Jong

Poppies growing through cracks in the concrete.

Ryan De Jong

®

Little Caesars Arena, Detroit, MI SmithGroup Ann Arbor Artline™, Town Hall ®, Umbriano ® - custom colours Contact us for samples, product information and Lunch & Learns. UNILOCK.COM | 1-800-UNILOCK

04/ Tree-eating spotted lanternflies, native to Southeast Asia.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

05/ A leaf suffering from “oak wilt,” a disease caused by fungus threatening to spread north from the U.S.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

06/ The bamboo-like Japanese knotweed outcompetes native plants.

04/ Tree-eating spotted lanternflies, native to Southeast Asia.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

05/ A leaf suffering from “oak wilt,” a disease caused by fungus threatening to spread north from the U.S.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the Invasive Species Centre

06/ The bamboo-like Japanese knotweed outcompetes native plants.

MODERATED BY GLYN BOWERMAN

MODERATED BY GLYN BOWERMAN

BIO/ RYAN DE JONG IS A MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STUDENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH AND GREW UP WORKING ON HIS FAMILY’S NURSERY NEAR VANCOUVER, B.C.

BIO/ RYAN DE JONG IS A MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STUDENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH AND GREW UP WORKING ON HIS FAMILY’S NURSERY NEAR VANCOUVER, B.C.