JANUARY 2023 NAVIGATION: A REFRESHER ON BUOYS GUNKHOLE: LAURA COVE WEST COAST POWER & SAIL SINCE 1968 THE WINTER ISSUE SEE YOU IN SEWARD (ALASKA) 27-FOOTER VS THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE

We developed the brand new MKIV Ocean furler especially for cruisers who would prefer a furler for cruisers. One smooth-rolling enough to make every furl a little less physical, while being bullet proof to stand and deliver for years. Designed especially for intuitive assembly and retrofit, the Ocean furler offers Harken’s most robust capability. Then we add the features cruising sailors have been requesting, at a price that is certainly its most competitive attribute.

The MKIV Ocean furler: built for years of hard work. Which will be nice to watch while not working that hard. WATCH A MKIV OCEAN MAST-UP REPLACEMENT HIGH PERFORMANCE, YES. RACY, ABSOLUTELY NOT.

© Tommy Bombon

JANUARY 2023 - 3

30 SEE YOU IN SEWARD A fantastic boating town tucked into Southcentral Alaska

36 SAILING THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE Remembering Dove III's cruise along the top of the world By

42 THE PISCES VI SUB Touring this locally designed submarine reveals small spaces and big technology By

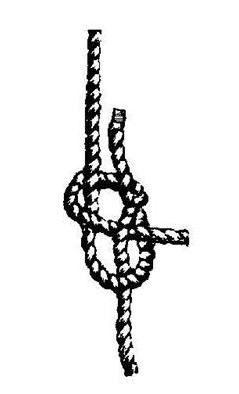

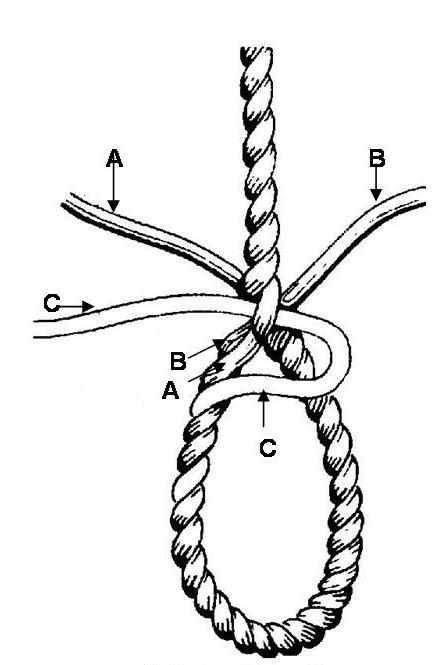

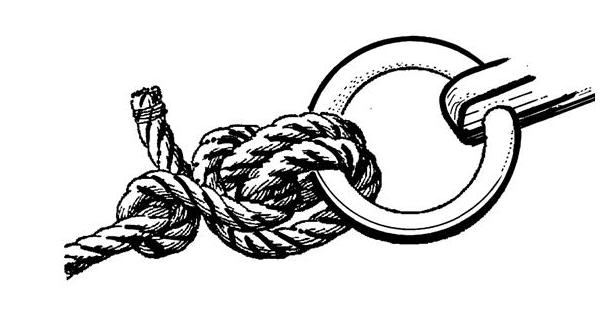

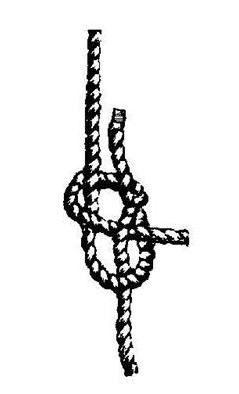

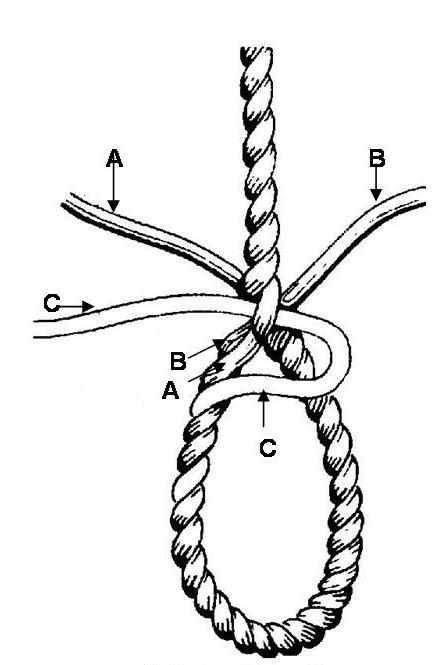

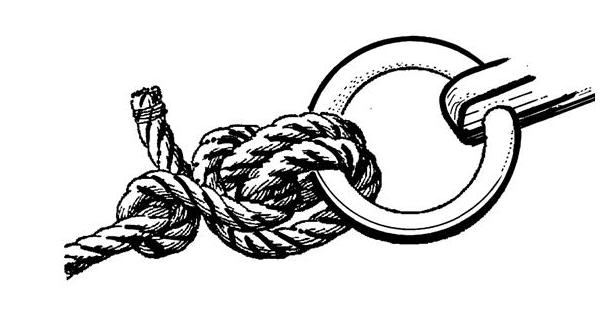

48 MARLINSPIKE SEAMANSHIP Part 2: The essential knots and how to tie them By Martyn

IN EVERY ISSUE 4 PASSAGES By Sam Burkhart 6 LETTERS 8 CURRENTS Canada’s Luxury Tax, marina updates, Sacred Journey exhibit at Science World 18 GALLEY Bulgur Salad By Roxanne Dunn 22 GO BOATING A Requisite Refresher on Buoys By Liza Copeland 26 GUNKHOLE Laura Bay, Broughton Island By Deane Hislop 52 THE FAVOURED TACK San Juan Convergence By Alex Fox 56 THE FISHING FIX 2023 Wish List By Tom Davis 60 ON BOARD POWER Greenline 45 Fly By Peter A. Robson 114 COCKPIT CONFESSION Heavy Weather Sailing By Stephen Gwyn

THE COVER

First 35s5 exploring

FEATURES VOLUME 65 - NUMBER 01 30 60 36

JANUARY

By Norris Comer

Len Sherman

Jonn Braman

Clark

ON

A Beneteau

Kenai Fjords National Park, Alaska Photo: Craig Wolfrom Photography

PASSAGES

THE AFTERGUARD

EDITOR

Sam Burkhart editor@pacificyachting.com

ART DIRECTOR Arran Yates

Cruising Into the New Year

Anew year has us looking ahead. What does 2023 have in store for us? It’s hard to predict the future, but one thing that we know is coming this year is the Vancouver International Boat Show—in person! Yes, after two years of digital, online, virtual “boat shows,” BC Place and the broker docks at Granville Island will once again be open to the boating public from Febru ary 1 to 5. The Pacific Yachting crew will be there with a booth of our own and we hope to see you there!

And let’s not forget the Seattle Boat Show. This will be their second year back after a one-year hiatus. If you didn’t get to go last year, it’s worth the trip (February 3 to 11).

It’s hard to look ahead without com ing up with some goals for the new year. I stop short of calling them resolutions. Instead, I’m inspired by Tom Davis’ “Wish List” on page 56 to create a wish list of my own for the new year. Below are five goals for 2023. I hope I don’t jinx anything.

1.

I hope that 2023 is forest fire-free. We were lucky last year that after a slow start weather wise, the skies on the south coast remained smoke free until the end of the summer and even then, it was nothing compared to previous years.

2. I hope that I am able to spend more days on the water than last year. That’s

not to say I didn’t get out last year, but more time on the water is always better, right? I’m hoping for at least 30 nights on the boat.

3.

I plan to visit at least three new places this year. I don’t think Seward will make the list although Norris Comer’s article on page 30 certainly makes a compelling argument. Instead, I’ll pick some destinations closer to home. Lau ra Bay on Broughton Island (page 26) sounds like a nice spot to drop the hook and spend a leisurely few days watching the wildlife while the prawn pots soak.

4.

I plan to get back into racing. It’s been a few years since I’ve sailed competi tively (racing against unknowing boats in English Bay doesn’t count). I’ll admit I am more of a cruiser these days, but racing is a great way to learn new skills and meet new friends, whether you’re a powerboater or a sailor normally.

5.

I hope to visit Saturna Island for the annual Lamb Barbecue held during the Canada Day long weekend. I had plans to go in 2021, unfortunately it was can celled due to Covid. So, as long as it happens this year, I’ll be there.

No major New Year’s Resolutions for me—just a few easily attainable boat ing goals. I’ll let you know how I made out at the end of the year. Cheers to 2023!

–Sam Burkhart

pacificyachting.com @pacific_yachting pacificyachtingmagazine

ASSISTANT EDITOR Blaine Willick blainew@pacificyachting.com

AD COORDINATOR Summer Konechny

DIRECTOR OF SALES

Tyrone Stelzenmuller 604-620-0031 tyrones@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER (VAN. ISLE) Kathy Moore 250-748-6416 kathy@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER Meena Mann 604-559-9052 meena@pacificyachting.com

PUBLISHER / PRESIDENT Mark Yelic MARKETING MANAGER Desiree Miller GROUP CONTROLLER Anthea Williams ACCOUNTING Angie Danis, Elizabeth Williams CONSUMER MARKETING Craig Sweetman

CIRCULATION & CUSTOMER SERVICE Roxanne Davies, Lauren McCabe, Marissa Miller

SUBSCRIPTION HOTLINE 1-800-663-7611

SUBSCRIBER ENQUIRIES: subscriptions@opmediagroup.ca

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

One year Canadian and United States: $48.00 (Prices vary by province). International: $58.00 per year.

Editorial submissions: Submissions may be sent via email to editor@pacificyachting.com or via mail with a self-addressed, stamped envelope. Queries are preferred. The publisher assumes no responsibility for lost material.

From time to time, we make our subscribers’ names available to reputable companies whose products or services we feel may be of interest. To be excluded from these mailings, just send us your mailing label with a request to delete your name.

Printed in Canada

Return undeliverable Canadian address to Circulation Dept. 802-1166 Alberni Street Vancouver, BC V6E 3Z3 Canada

Contents copyright 2022 by OP Media Group Ltd. All rights reserved.

ISSN 0030-8986 802-1166 Alberni Street Vancouver, BC, Canada V6E 3Z3 Tel: (604) 428-0259 Fax: (604) 620-0245

4 JANUARY 2023

50%

YOUR EXCLUSIVE HAMPTON & ENDURANCE PACIFIC NW DEALER 52’ Sunseeker 2008 4 Stateroom / 6 Head Layout • New 20’ Beam Forward Galley • Aft Deck & Skylounge Day Heads Open Main Level • Full Crew Quarters New Master Double Sink Layout 901 FAIRVIEW AVE N #A150 | SEATTLE, WA 98109 SEATTLE@HAMPTONYACHTGROUP.COM | 206.623.5200 | WWW.HAMPTONYACHTGROUP.COM NEW INVENTORY • AT OUR DOCKS More Listings Available at Our Docks

LETTERS

WE WELCOME YOUR LETTERS

Send your letter, along with your full name, and your boat’s name (if applicable), to editor@pacificyachting.com. Note that letters are selected and edited for brevity and clarity.

AN UNFORGETTABLE KINDNESS

I wanted to write a letter to express my profound gratitude to the captain and crew of the MV Tiger Lilli. I was sailing my 17-foot Albacore off Worlcombe Island in strong winds. I had decided that it was better to go back to shore as the sails were overpowered. While tack ing, my jib sheet caught in the cleat and when I reached over to release it, the wind threw the boat over. I have righted the boat numerous times before by my self, but the wind was especially strong. Tiger Lilli saw the capsize and stopped to help. It was hard to communicate as the wind gusts grew stronger. I asked them to standby in case I could not right the boat. After twice having the boat flip over, I realized my strength was gone and I had been in the cold water some time. I came on board Tiger Lilli and the crew was very helpful as we tried to tow the small boat to the lee of the island so I could try again. Luckily my wife had seen what was happening and asked a neighbour to use their smaller boat to help. I truly appreciate the crew’s will ingness to interrupt their trip to lend me hand—a kindness that I have recounted countless times.

—Chris Ladner

RE: THE CURVE OF TIME

When I moved to British Columbia from Quebec, a friend suggested I read The Curve of Time by Muriel Wylie Blanchet (first published in 1961). Blan chet was born in Montreal. Moving to BC was a big adventure for my Quebec family. I was enchanted by Blanchet’s memoir and travelogue, and through her story I fell in love with our beautiful coastal BC waters.

So, I was delighted to read the De

cember article by the four “Anchor Wenches” who set off to recreate Blan chet’s journey. Reading about their hap less adventures reminded me how brave Blanchet was during her annual summer cruise when she carried her most pre cious cargo—her five children. During her annual voyage even her three-yearold was given a task on board. Every so often I re-read Blanchet’s book. It can encourage parents who sail with their children; for landlubbers the book demonstrates how to face hard times with courage and imagination. I look forward to seeing the upcoming docu mentary “By All Means” chronicling the modern nautical adventure of the four wenches.

—R. M. Davies North Vancouver

GOODBYE GORDON

I saw Gordon’s obituary in the Sun and also your editorial comments about him in the December issue and wanted to say how well you captured his gentle presence at PY. In the time I was at PY I might have exchanged a few dozen words with him, but he was always helpful and patient. Sorry to hear of his passing.

—William Kelly

6 JANUARY 2023

ALASKAN 250 | 270 Quarter-inch-thick hull. Eight-foot-wide bottom. Pair this boat with twin engines, and you have the recipe for safety that professionals and family fisherm 1462 Mustang Place Port Coquitlam, BC V3C 6L2 Phone: 604.461.3434 Open Tuesday-Saturday 9:00AM - 5:30PM Closed Monday& Sunday Sea Runner Pro V

01/2023

CURRENTS

WE ENCOURAGE CURRENTS SUBMISSIONS

This is a local news-driven section. If something catches your attention that would be of interest to local boaters, send it along to blainew@pacificyachting.com.

PY SPECIAL REPORT

Making Sense of Canada’s new Select Luxury Items Tax Act

s boaters—you may have heard of the new Luxury Items Tax. In simple terms, the new tax (which has been enforced since September 1, 2022) applies to cars and private aircraft that cost more than $100,000 and to boats (including power yachts, cruisers, sail boats, deck boats, waterskiing boats and houseboats) with a

cost over $250,000. Products manufactured in 2018 or earlier are exempt, as are boats used for utilitarian purposes only.

The government’s reasoning for the new tax is that it will not only help reduce inequality by distributing wealth but will also discourage the country’s wealthiest from purchasing emis sions-hungry vehicles, thereby protecting the environment.

8 JANUARY 2023

CURRENTS

Mike2focus/Dreamstime

A

SHELTER ISLAND MARINA ON-SITE CONTRACTORS SHELTER ISLAND MARINA & BOATYARD 6911 Graybar Road, Richmond BC, Canada V6W 1H3 Ph: 604-270-6272 | TF: 1-877-270-6272 | infodesk@shelterislandmarina.com SHELTERISLANDMARINA.COM Sharp Marine Restoration & Joinery Legacy Marine Erl Signs Cooper Boating Deep Cove Marine Industries Valet Yacht Services Dames Marine Services Ocean Control Services Inc. Marine Blast RR Yacht Services Moonlight Marine Nordmanner Marine Services SHELTER ISLAND IS CAPABLE OF ACCOMMODATING VESSELS UP TO 150' LONG WITH A BEAM OF 29'! 220T TRAVELIFT 75T TRAVELIFT BRACEWELL MARINE GROUP | COMMODORE’S BOATS | PRODIGY MARINE | BLUEWATER SHELTER ISLAND MARINA & BOATYARD Shelter Island Marina has succeeded in achieving a prestigious 4-ANCHOR RATING under its Clean Marine BC program.

A statement on the Canadian gov ernment website says, “Some Canadians have lost their jobs or small busi nesses [during the pandemic], while some sectors of the economy have flourished. That’s why it is fair today to ask those Canadians who can afford to buy luxury goods to contribute a little bit more.”

By imposing the new tax, the federal government expects to increase federal revenue by $604 million over the first five years—something that falls in line with the current government’s promise to ensure “that all Canadians and busi nesses contribute their fair share to a stronger economic recovery.”

HOW MUCH TAX IS PAID?

The tax payable is 10 percent of the total retail cost, or 20 percent of the amount by which the cost exceeds the price threshold of $250,000, whichever is lower. For ex ample, the tax on a boat priced at $320,000 would be 20 per cent of $70,000 ($14,000), in preference to 10 percent of $320,000 ($32,000).

How this tax will eventually affect the used market isn’t entirely clear for foreign registered boats—but the lan guage does imply it’s for new boats. However, any boat acquired and reg istered in Canada before September 1, 2022 and sold later will be excluded from this new tax, as will any vessel with the luxury tax already paid (i.e. a boat purchased after September 1, 2022 with the luxury tax paid at the time of purchase won’t have the tax added a second time).

WHY IS THE TAX CONTROVERSIAL?

History shows that many customers won’t buy a boat if it is tagged with a luxury tax. New Zealand, Italy, Nor way, Turkey and Spain have at differ

ent times introduced luxury taxes only to later repeal them. In the US, a 10 percent luxury tax was introduced in 1991 and was highlighted as further damaging an already beleaguered in dustry. “Production of $100,000-plus yachts peaked at 16,000 in 1987. But by 1990, yacht output had fallen to 9,100. In 1991, the first year of the luxury tax, it dropped to 4,300; in 1993, 4,250,” a Washington Post story at the time not ed. That tax was ended in 1993.

Mark Delaney, director of sales and marketing at KingFisher Boats in Ver non told CBC the tax will undermine a boom in boat sales that began when people were stuck at home during the COVID-19 lockdowns. He also ques tions why the tax targeted boats but not other recreational vehicles like RVs.

The National Marine Manufacturers Association (NMMA) Canada has also expressed concern about the negative im pact the luxury tax will have on boaters, dealers and small communities with boat ing focused economies. “We are ready to work with the government to find new ways to generate revenue,” said Sara An ghel, NMMA Canada CEO. “But we simply can’t support a new tax that would severely damage the boating industry, put thousands of good jobs at risk and potentially put government finances further into the red.”

The government is betting on Cana dians being willing to help each other out. During a news conference regard ing the tax Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland said, “I think it is entirely reasonable to say to someone who has $100,000 to spend on a car or a plane, or $250,000 to spend on a boat, ‘You need to pay a 10 percent tax to help everybody else.’ It is great for Canadians to be prosperous. I also think that people who are doing really, really well should feel comfort able supporting everybody else.”

—Diane Selkirk

BRITISH

ANCHOR MARINE Victoria, BC 250-386-8375

COMAR ELECTRIC SERVICES LTD Port Coquitlam, BC 604-941-7646

ELMAR MARINE

GLOBAL MARINE EQUIPMENT Richmond, BC 604-718-2722

MACKAY MARINE Burnaby, BC 604-435-1455

PRIME YACHT SYSTEMS INC Victoria, BC 250-896-2971

RADIO HOLLAND Vancouver, BC 604-293-2900

REEDEL MARINE SERVICES Parksville, BC 250-248-2555

ROTON INDUSTRIES Vancouver, BC 604-688-2325

SEACOAST MARINE ELECTRONICS LTD Vancouver, BC 604-323-0623

SEACOM MARINE LTD Campbell River, BC 250-286-3717

STRYKER ELECTRONICS Port Hardy, BC 250-949-8022

TOWNS MARINE SUPPLY Richmond, BC 604-277-3191

WESTERN MARINE CO Vancouver, BC 604-253-3322

10 JANUARY 2023 01/2023

CURRENTS

COLUMBIA

ELECTRONICS North Vancouver, BC 604-986-5582

WWW.FURUNOUSA.COM

Never miss another target, from close-in to the

and

with NXT technology. Get Out. Solid-State Radar that keeps you safe on the water so you can spend more time enjoying the journey. Sees targets farther & clearer than other Radars Rain Mode provides precise detection in any weather Target Analyzer™ alerts you to hazardous targets Displays target speed & course in seconds with Fast Target Tracking Exceptional short-range performance, perfect for tight passages Get the whole story at NavNet.com Go on a power trip with

horizon

beyond,

New Ownership for Race Rock Yacht Services

V Business Group Inc. has announced that on Novem ber 1 it assumed the opera tions of the boatyard located at West Vancouver Marina in Fisherman’s Cove, also known as Race Rock Yacht Services. The previous boatyard owners Jani and Teresa Diener are hap py to retire after many years of whole hearted service to the boating commu nity. Their passionate contribution to

fibreglass and gelcoat repairs, fabrica tion, bottom painting, canvas making and more. SV is looking forward to meeting and welcoming existing and new customers to the Race Rock boatyard.

SV Business Group is a team based in West Vancouver Marina with a goal to promote and develop recreational boat ing in British Columbia. They started in yacht sales and have expanded into

rine infrastructure. SV Business Group is a dealer of Greenline Hybrid Yachts, the only serial production hybrid boat builder in the world. The boats are en vironmentally notable for their dieselelectric motors and solar power. SV

01/2023

NEWS

Generator Sets 4-50kVA Propulsion Engines 10-150 HP Saildrive & Sterndrive Compatible Powered by betamarinecanada.com Our best prices of the year! Large inventory for prompt delivery. See you at the Vancouver Boat Show Feb 1 to 5 Toronto Int. Boat Show Jan 20 to 29

S

February 1 to 5

WESTERN CANADA’S LARGEST boat show is back at BC Place and on-the-water at Gran ville Island Maritime Market & Marina from Wednesday, February 1 to Sunday, February 5.

After a two-year hiatus, this well-loved boating event is returning. This year’s show will feature an incredible display of boats, featuring the latest in power and sail, inflatables, SUPs and more! There will be free interactive seminars and do-it-yourself workshops, as well as enter tainment for the whole family. We can’t wait to see you there!

For more information, a full seminar schedule and to purchase tickets visit vancouverboatshow.ca.

February 3 to 11

START DREAMING AND get your shopping lists ready! The Seattle Boat Show presented by Union Marine and the Port of Seattle is back from Friday, February 3 through Saturday, February 11. It’s the largest show on the West Coast with two locations: indoors at Lumen Field Event Center and on the water at the Port of Seattle’s Bell Harbor Marina.

There are three acres of the latest and greatest gadgets and gear as well as an extensive seminar selection. Twenty-five percent of this year’s semi nars are new and focusing on technology and innovation. The special seminar ticket includes multi-day admission to the show, a boatload of goodies and access to all seminars online, on demand after the show.

If that weren’t enough fun, there are wine and beer nights, a Dogs on Deck promotion and a special Kids AquaZone full of family-friendly ac tivities.

A free shuttle runs continuously between both locations. To find out more go to seattleboatshow.com.

JANUARY 2023 - 13

MARINE 4 PERSON LIFE RAFT • Light & Compact - 19 lbs • Just throw- it automatically inflates • Easy maintenance - lower servicing costs • Thermally insulated & reflective floor For Inshore & Coastal Use • Compact Stowage 20” x 13” x 7” • Very Stable 3 Water Pockets - 165 litres ballast water • Large Sea Anchor 15.8” x 23.6” • Durable 420D Nylon Fabric - PU Laminated rekord-marine.com REKORD MARINE ENTERPRISES Distributed by: 8194 Ontario Street, Vancouver Ph 604 325-5233 Jacket $ 299 Trouser $ 239 • Lightweight Two Layer Fabric • Taped Seams • Mesh Lining • Waterproof & Breathable • High-Vis Hood • Lined Hand Warmer Pockets VIGO Coastal Wet Weather Gear Jacket Available in Men’s & Women’s Models THUNDERBIRD MARINE REKORD MARINE ENTERPRISES Available at: 5776 Marine Drive, West Vancouver Ph 604 921-9011 8194 Ontario Street, Vancouver Ph 604 325-5233 gulnorthamerica.com

Sacred Journey at Science World EVENTS

For thousands of years, the traditional ocean-going canoe (“glwa” in Heiltsuk) was the main means of transportation for Indigenous Peoples in the Pacific Northwest. It was essential for sustenance, transportation and for developing social and ceremonial life for the First Nations Peoples. Told by Indigenous leaders and participants of today’s canoe resurgence for the first time, Science World’s Sacred Jour ney exhibit unveils this story through the Indigenous framework of “nuyum” (traditional nar ratives) expressed through figurative art, immersive audio and extensive interac tive video projections and displays of those who have participated in a Tribal Ca noe Journey.

“Amongst the Heiltsuk Na tion and other Indigenous Peoples, the last 150 years have seen massive societal changes that have had

devastating and detrimental impacts on our people. During this time of sup pression and technology change, the ocean-going canoe, the Glwa, was al most lost. Sacred Journey allows us to share the knowledge and experience of this journey from an Indigenous point of view,” said λáλíyasila, Hereditary Chief Frank Brown, Heiltsuk Nation. In this exhibit, visitors will experi ence stunning art pieces including a monumental canvas canoe with four prominent Heiltsuk clan crests in striking colours painted by Heiltsuk artist K.C. Hall; overarching house posts and paddles to accompany the canoe, carved by Chazz Mack; and an eagle-human mask, located at the entrance to the exhibit, carved by Ian Reid. Renowned Heiltsuk/Tsimshian artist Roy Henry Vickers created a moon and salmon logo for the exhibit and a “Many hands” canoe image. The exhibition will be on display at Science World until February 20, 2023.

THE EVOLUTION PREMIUM PERFORMANCE

Sidney, BC | 250-656-2639

INA MARINE Victoria, BC | 250-474-2448

INLET MARINE Port Moody, BC | 604-936-4602

LA MARINE Port Alberni, BC | 250-723-2522

LUND AUTO & OUTBOARD LTD. Lund, BC | 604-483-4612

MADEIRA MARINE 1980 LTD. Madeira Park, BC | 604-883-2266

M&P MERCURY SALES Burnaby, BC | 604-524-0311

MONTI’S MARINE & MOTOR SPORTS Duncan, BC | 250-748-4451

ROD’S POWER & MARINE LTD. Tofino, BC | 250-725-3735

SEA POWER MARINE CENTRE LTD. Sidney, BC | 250-656-4341

MERCURY 5.7L V10 350 AND 400HP

VECTOR YACHT SERVICES LTD. Sidney, BC | 250-655-3222

V10 Verado outboards shift your expectations performance feels like. They come to power, propelling you forward to sensational smooth, quiet and refined, they deliver only Verado outboards can provide.

Mercury engines are made for exploring.

14 JANUARY 2023 01/2023

CURRENTS

EVOLUTION OF PERFORMANCE

THE EVOLUTION OF PREMIUM PERFORMANCE

400HP VERADO ®

expectations of what high-horsepower to life with impressively responsive sensational top speeds. Exceptionally deliver an unrivaled driving experience

V10 Verado outboards shift your expectations of what high-horsepower performance feels like. They come to life with impressively responsive power, propelling you forward to sensational top speeds. Exceptionally smooth, quiet and refined, they deliver an unrivaled driving experience only Verado outboards can provide.

Mercury engines are made for exploring. So are you. Go Boldly.

exploring. So are you. Go Boldly.

JANUARY 2023 - 15 MercuryMarine.com/V10

MERCURY 5.7L V10 350 AND 400HP VERADO ® MercuryMarine.com/V10

loha! Preliminary planning for the 2024 Vic-Maui In ternational Yacht Race is underway. Interest in the Vic-Maui has been growing from rac ers around the globe—from Cannes, France to Canberra, Australia and be yond. Competitors are already prepar ing for the July 2024 race because it takes time to organize oneself, one’s boat and the crew needed to do this premier world-class ocean race. How does one prepare? Vic-Maui provides exclusive

access to race entrants to select training opportunities throughout the upcom ing 18 months, including World Sailing approved Offshore Personal Survival Courses for which registration always sells out within days. Watch the online page vicmaui.org/courses for the avail able courses.

Still curious but don’t know where to start? We have skilled mentors who have done the race at least once (some as many as 13 times!) and are ready to guide, support and coach skippers and

crew toward race readiness.

This race is best suited for those who love a challenge and an adventure, and most of all understand success comes through teamwork. If this is you, reach out to Event Chair Jim Innes of Royal Vancouver Yacht Club and get on board now! rvyc-chair@vicmaui.org

Want to ‘kick the tires?’ Vic-Maui will hold seminars by knowledgeable and skilful past racers at the Vancouver Inter national Boat Show this February. We’ll also be at the Seattle Boat Show on Feb ruary 3 at the booth of long-time spon sors and supporters Signature Yachts and CSR Marine. Come listen and bring your questions. You’ll find lots of sup port to get you into this adventure of a lifetime. vicmaui.org.

—Charlotte Gann

—Charlotte Gann

16 JANUARY 2023 01/2023

Vic-Maui Race—You Can Do It! A 6771 OLDFIELD ROAD, VICTORIA, BC - TOLL FREE: 1-877-652-6979 - SHERWOODMARINE.COM 6771 OLDFIELD ROAD, VICTORIA, BC - TOLL FREE: 1-877-652-6979 - SHERWOODMARINE.COM Find Us On Facebook Over 36 Years in Business IN STOCK IT’S A BOAT SHOW EVERY DAY AT SHERWOOD MARINE CENTRE! VANCOUVER ISLAND’S LARGEST MARINE DEALER OVER 80 BOATS & 150 INFLATABLES SEE YOU AT THE VANCOUVER BOAT SHOW! FEBRUARY 1 5 6771 OLDFIELD ROAD, VICTORIA, BC - TOLL FREE: 1-877-652-6979 - SHERWOODMARINE.COM Find Us On Facebook Over 36 Years in Business IN STOCK IT’S A BOAT SHOW EVERY DAY AT SHERWOOD MARINE CENTRE! VANCOUVER ISLAND’S LARGEST MARINE DEALER OVER 80 BOATS & 150 INFLATABLES VANCOUVER ISLANDS LARGEST MARINE DEALER Over 40 Years in Business

MARINA NEWS

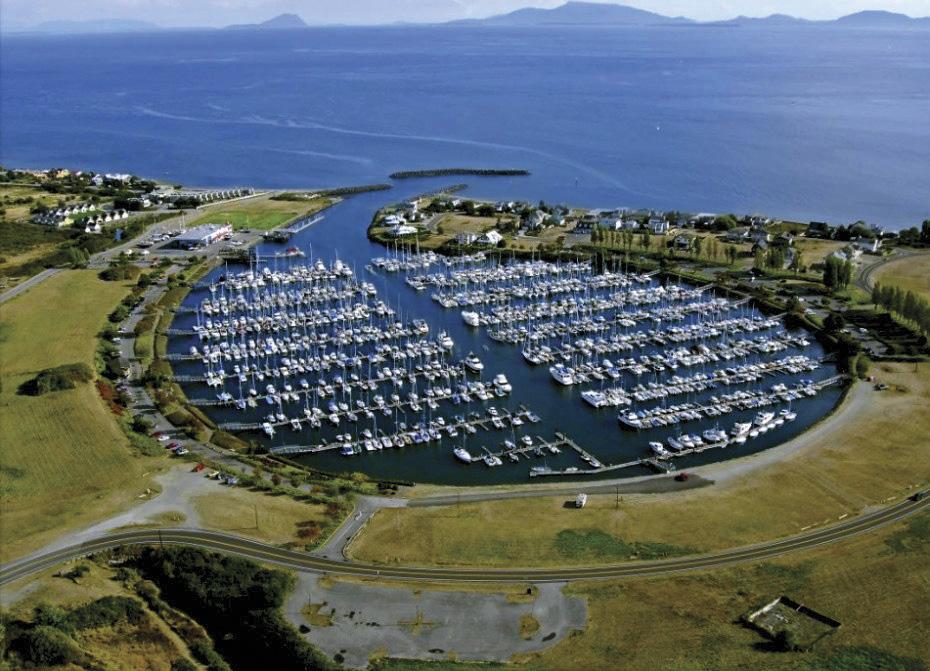

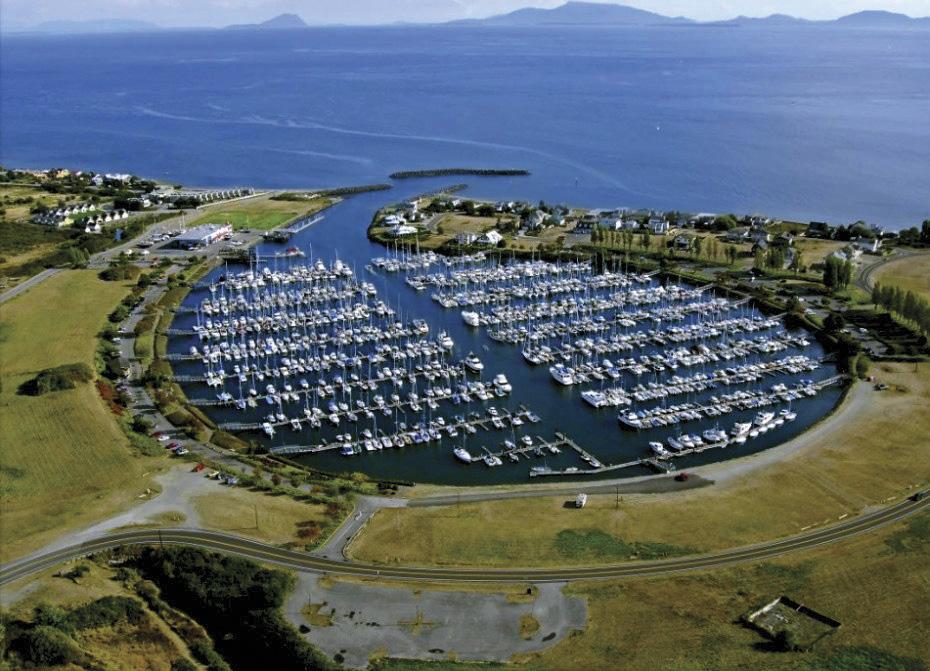

Marina Expansion in Sooke Bay

Sooke Bay Marine Centre, located 55 min utes east of Victoria, has just undergone a major expansion with the addition of a new dock. With the additional dock space they now have over 60 slips available in total and can accommodate vessels up to 60 feet. They have also dredged their marine basin which allows for larger displacement vessels to use the area. The new docks are fully serviced with 30-amp electrical and are well protected with a gated entrance. There is also a 70-ton boat ramp for launching and hauling. Go to sookebaymarine.ca to learn more.

JANUARY 2023 - 17

CRU 660LUX with Merc 250 HP DTS Fiberglass Hull with Towing Setup DTS Controls with Mercury Vessel View Smart Monitoring Hydraulic Steering with SS Wheel Center Console with Front Seat Flip Up Bolster Helm Seat Stern Seat with Storage, Bow Seat Upgraded Marine Sea�ng Top with Rocket Launchers and Setup for Down Riggers Simrad Chart Plo�er with Mul�view Depth Sounder Orca Hypalon Tubes Military Grey Hypalon Handles & Rubbing Strake, GRP Tube Steps Anchor Base with Nav Lights EVA Custom Decking 150 Liter Fuel, 80 Liter Water Tanks Fresh Water Swim Shower Automa�c Electric Bilge Pump Dual Batteries, Boxes and Switch Air Pump, Paddles and Repair Kit Safety Relief Valves Stainless Steel Boarding Ladder Fenders, Dock Lines and Safety Kit MSRP $179,900 Demo Boat, What can we build for you? 604.312.9755 info@mvpmarineltd.com Boats, Built By Boaters For Boaters CRU 660LUX Vancouver Boat Show Booth #274 www.mvpmarineltd.com info@mvpmarineltd.com 604.312.9755 MVP Yacht Seating & T-Tops Custom t enders “Boats built for Boaters by Boaters!”

BY ROXANNE DUNN

Consider the Kernel

Bcould conquer the world, I resolved to make all my meals tasty, nutritious and enjoyable. Who was I kidding? Fortu nately, resolutions are made to be bro ken. Right?

end of a day on the water and heading off to get a bacon cheeseburger with fries is fun, easy and sure to please ev eryone on board.

Buckle up. It’s time for another trip around the sun. Just like that, all of a sudden, we have a brand-new year with a total of 1,095 meals to prepare—at least.

One bright morning last year, when the sun was shining and I felt certain I

So, I decided to make some of them tasty, nutritious and enjoyable. And when I come up with a new recipe, I want it to be quick and easy to make while we’re out cruising.

It’s not the tasty and enjoyable part that’s hard. It’s easy to make things that are fun to eat. S’mores, hot fudge sundaes, peach cobbler and cinnamon rolls come to mind. Tying up at the

Good nutrition is another matter. Even defining good nutrition is diffi cult. If you talk to 10 different people, you’ll get at least 10 opinions about the best type of diet—high protein, low protein, high fat, low fat, high carb, low carb, Mediterranean, vegetarian, vegan; to name a few. If you’re like me, your head starts to spin and you decide to keep on with the same old same old. But no excuses. I already know that

18 JANUARY 2023

Bulgur salad—a tasty, (healthy), cruise-friendly meal

Kim La Fave

COLUMN GALLEY

@VanBoatShow | VancouverBoatShow.ca FEBRUARY 1 - 5, 2023 | BC PLACE & GRANVILLE ISLAND PRESENTS THE BOATING EVENT OF THE YEAR IN WESTERN CANADA!

GALLEY

No-Cook or Quick-Cook Bulgur Salad

VEGETABLE OPTIONS

Prepare 4 to 6 cups of any combination of the following vegetables:

since different foods contain different nutrients, simply increasing the variety of vegetables, fruits, nuts and grains in our daily menu plan is a step toward better nutrition. I know it’s a good idea to avoid highly processed, precooked, prepackaged foods. It’s good to con sume fewer refined carbohydrates, such as white rice, bread and pasta, and eat more complex carbohydrates, such as brown or wild rice and whole-wheat.

If you’re like me, you’ve avoided cook ing grains like farro, quinoa, bulgur, barley, millet and buckwheat because you’re not sure how to use them or whether you or your family would en joy them. There’s one way to find out. This month, I’m going to get acquaint ed with three types of wheat I have rare ly used: bulgur, farro and wheat berries. Bulgur is precooked, cracked wheat kernels. Depending on the coarseness of the grind, it needs little or no cooking.

Farro is uncooked wheat kernels with the hull removed. Removing the hull takes away some of the nutrition, espe cially fibre, but it is still a good choice. It should be cooked for 15 to 30 min utes in boiling water—the same way you cook pasta.

Wheat berries are unprocessed grains of wheat. None of the nutrition has been removed, and since it has not been altered, it must be cooked and takes the longest—about an hour.

Like rice, couscous and quinoa, these wheat derivatives are best stored in airtight containers in a cool place, or if possible, in the freezer, as oxidation makes them rancid.

Because bulgur is quicker to prepare than farro or wheat berries, it’s the easi est to work into a cruising menu plan, so I’m going to start with that.

In eastern Mediterranean countries, bulgur’s nutty flavour, versatility and nutritional value have been highly regarded for centuries. Here, it’s gen erally available in three grinds: fine, medium and coarse. Fine and medium

Note: 1/4 cup dry bulgur makes approximately 3/4 cup soaked.

For six servings

INGREDIENTS

•1 1/2 cups fine or medium-grind bulgur

•1 cup water

•1/4 teaspoon salt

•1/3 cup freshly squeezed lemon juice

NO-COOK BULGUR

1. Mix salt with lemon juice and water.

2. Add the bulgur and stir.

3. Let rest at room temperature 1.5 hours or until liquids are absorbed. Stir occasionally. Add water if necessary, until it has the right “chew.”

4. Add lemon herb dressing and veg etable options (to follow).

QUICK-COOK BULGUR

1. Omit lemon juice and add 1/2 cup vegetable or chicken broth.

2. Mix ingredients.

3. Cover and simmer gently approx. 12 minutes.

4. Drain excess liquid.

5. Fluff with a fork and let cool.

6. Add lemon herb dressing and veg etable options (to follow).

•Cherry tomatoes, halved

•Cucumber, diced

•Sugar snap peas, sliced

•Carrot, coarsely grated

•Green and/or yellow wax beans, blanched and sliced

•Asparagus, blanched and sliced

•Yellow or red bell pepper, diced

•Zucchini, diced

•Scallions, thinly sliced

Lemon Herb Dressing

INGREDIENTS

•1/3 cup extra virgin olive oil

•2 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons fresh lemon juice

•1 teaspoon lemon zest, finely grated, packed

•1/8 teaspoon salt or to taste

•15 to 20 grinds pepper or to taste

•5 to 6 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley or mixed fresh herbs

Optional

•1 small clove garlic, minced or pressed

•2 tablespoons minced shallot

METHOD

1. Toss vegetables with three tablespoons of dressing.

2. Let rest a few minutes, then stir in bulgur.

3. Taste, correct seasonings and add desired amount of dressing.

4. Garnish with toasted, slivered almonds.

grind bulgur can be prepared by soak ing it for about an hour and a half, or by simmering it briefly. On a hot day, in a cramped galley, the ability to prepare it without cooking makes it a godsend, and it’s perfect for tabbouleh and sal ads. Coarsely ground bulgur should be simmered until it is al dente and is often served warm in a pilaf.

Once soaked or cooked, bulgur begs for the addition of flavour and is ame nable to various combinations of spices and herbs, salt and sweet notes. Add

a sprightly dressing, some vegetables with a variety of colours and textures and some nutty crunch. Voilà! You have a delicious dish to set beside grilled chicken, fish, beef, lamb or pork.

Here’s my first step toward keeping at least one of my resolutions: a salad featuring fresh vegetables and my goto lemon herb dressing. Quinoa or wild rice can be substituted in this rec ipe. Cook them according to package directions and adjust the seasonings to taste.

20 JANUARY 2023

COLUMN

Complete inventory of pumps, parts, impellers, & rebuild kits Pump & parts for engines using Sherwood pumps Cummins Cat Universal Crusader Chrysler Onan Perkins & others Quality Volvo Penta diesel replacement parts From Sweden Prices significantly less the Volvo with a 3 year warranty Wema liquid senders Direct replacements for: fuel, potable water, gray & black water senders Superior accuracy Simple installation Great prices -in stock from $43.95 Dealer inquiries welcomed NHK KE+ series of electronic engine controls Over 30 years in the electronic control industry. Thousands of installations Multiple combination's of mechanical and fully electronic systems. Call for a quote today, all units are in stock Complete engine rebuild kits Up to 45% lower cost Oil fuel & air Filters Alternators & Starters Turbos Dealer inquiries welcomed Dealer inquiries welcomed Dealer inquiries welcomed

GO BOATING

BY LIZA COPELAND

A Requisite Refresher on Buoys

Ilia, New Zealand, parts of Africa and most of Asia, when entering a harbour, marks to port are red and marks to starboard are green.

In my last article, ‘Beware the Falling Tide and Be Prepared’ (August, 2022)

I mentioned that the local aids to navi gation are made up of five buoy types: lateral, cardinal, isolated danger, spe cial and safe water marks. These help boaters navigate safely to avoid obsta cles and hazards by indicating where safe water lies. As it may be a while since you referenced them, here is a quick refresher.

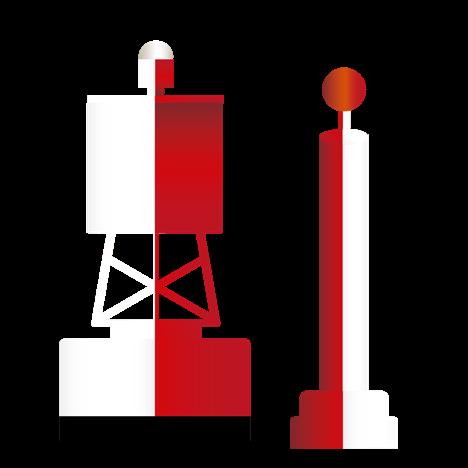

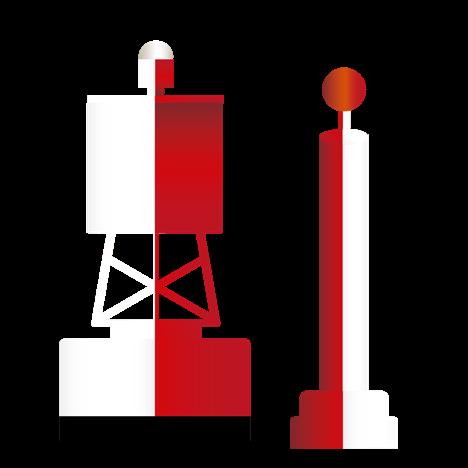

LATERAL BUOYS

Lateral buoys indicate the side on which they may be safely passed. There are five types of lateral buoys: port hand, starboard hand, port bifurca tion, starboard bifurcation, fairway and isolated danger. All of these we will go over in detail.

RED RIGHT RETURNING

In 1982 the disparity of innumerable buoyage systems around the world prompted the International Associa tion of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities (IALA) to implement a standard. The result is two systems worldwide both of which use red and green marks. In region A, which consists of Europe, Austra

In region B, which includes all of North America, Central America and South America, plus the Philippines, Japan and Korea, when entering a har bour, the marks to port are green and marks to starboard are red. Here on the West Coast, RED marks are on the RIGHT side when RETURNING from seaward and heading upstream. Conversely, when leaving harbour or heading downstream the red port mark should be kept on the boat’s port (left) side and the green mark on the vessel’s starboard (right) side. Although this concept is generally

easy to follow, it also depends on your knowledge of the direction of the flood and ebb. This can be confusing when there are many channels and islands around. So a chart should always be referenced in advance, with particular attention paid around the Campbell River region where the flood and ebb tides change direction with the water flowing around the south or north end of Vancouver Island.

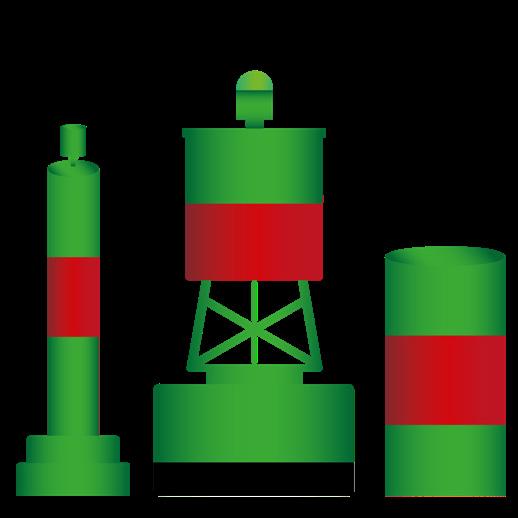

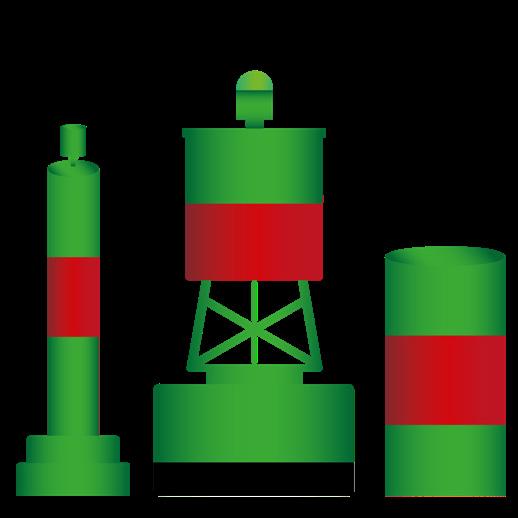

PORT AND STARBOARD BUOYS

Green port hand lateral buoys come in different shapes with differing fea tures. If unlit they will have a flat top (cylinder shaped). The top mark may be a single tall green cylinder. They may have letters, odd numbers and green retroreflective material. Larger pillars may have a green light (Fl) 4s or (Q) 1s. (See legend at the end of article).

Red starboard hand lateral buoys, that mark the starboard or right side of the channel or danger when heading in an upstream direction, have a pointed (conical) top if unlit. Larger red pillars can have a red light (Fl) 4s or (Q) 1s. The topmark is a single red cone, point upward (if equipped). These buoys may have letters and even numbers and red retroreflective material.

BIFURCATION BUOYS

Bifurcation buoys are part of the lat eral system and occur when a channel splits. They have red and green bands with the colour of the top band indi cating the main or preferred channel. A port bifurcation buoy (top green) indicates that the preferred or main

22 JANUARY 2023

When did you last look at the Canadian Aids to Navigation?

COLUMN

Starboard Lateral Buoys

Port Lateral Buoys

channel is on the starboard (right) side of the buoy, with the buoy kept on the vessel’s port (left) side when a vessel is heading upstream. It is mostly green with one red horizontal band and if unlit, it has a flat top. Lights are green, composite group Fl(2+1) 6s or Fl(2+1) 10s. The topmark is a single green cylinder (if equipped). There may be letters but no numbers and green retroreflective material.

A starboard bifurcation buoy (top red) marks the point where a channel divides when heading in the upstream direction when the preferred (main) channel is on port (left) side of the buoy, with the buoy kept on the ves sel’s starboard (right) side. It is mostly red with one green horizontal band and may have a red light, composite group Fl(2+1) 6s or Fl(2+1) 10s unlit, it has a pointed (conical) top. The topmark is a single red cone, point upward (if equipped). It may have let ters but no numbers and red retrore flective material.

JANUARY 2023 - 23

Port Bifurcation Buoy

Repair and Overhaul • Awlgrip™ Refinishing • Fibreglass Repairs • Hard Tops • Seasonal Maintenance • Polishing and Detailing • Experts at gel coat colour matching and repair Yacht Rigging • Inspections • Work Aloft • Splicing and Swagging • Custom Aluminium and Composite Spars • Installations • Architectural rigging • Deck Layout Metal Fabrication • Stainless and Aluminium • Arches • Radar Masts • Davits • Bow and Stern Rails • Bow Rollers • Bimini and Dodger frames • Custom fabrication for all your metal needs Proudly Serving the Boating Community Since 1980 Blackline Marine, 2300 Canoe Cove Road, Sidney, BC www.blacklinemarine.com | info@blacklinemarine.com | 250-656-6616 All available at Marine Stores and Book Stores Our Cruising Guides are your Boating Companions. Visit Marine Stores, Marinas and Pacific Yachting Magazine • Broughton Islands • Desolation Sound • Gulf Islands PETER VASSILOPOULOS Puget Sound, the San Juan Islands, the Gulf Islands, Sunshine Coast, Desolation Sound, West Coast of Vancouver Island, Haida Gwaii and the Inside Passage of British Columbia. Aerial Photographs and Full Colour Diagrams Marinas • Fuel Docks • GPS Waypoints AND This tenth edition of Docks and Destinations has many updates. Its full colour format and layout are designed to provide quick and easy reference to marinas and facilities for mariners boating in the Pacific Northwest. The book covers Puget Sound, the San Juan Islands, the Gulf Islands, the Sunshine Coast, Desolation Sound, the Broughton Islands, Haida Gwaii, the West Coast of Vancouver Island, and the Inside Passage to the southern tip of Alaska. It includes numerous places along the way. The pages take the mariner from one stop to the next in a successive, geographic progression. Like its companion cruising guide Anchorages and Marine Parks, it returns south by way of the west coast of Vancouver Island. The information is provided in a user-friendly format enabling the reader to see at a glance where they have been and where they are going in relation to other stops. Numerous maps and diagrams include clear icons showing the presence of fuel stations and all services for the mariner so that at a glance it is possible to determine what an overnight stay at a marina has to offer Clockwise from above: View of Anacortes marinas in Puget Sound; Crowds converge on the Saturday market at Ganges in the Gulf Islands; Yacht clubs love to gather at Genoa Bay on Vancouver Island. Front cover: Enjoying the atmosphere at Blind Channel en route to the Broughton Islands. Chyna Sea Ventures Ltd. DOCkS DOCkS “We Have found your guides essential reading and enormous ly useful and our holidays have been all the more enjoyable as a result.” – David D. Cotterell .UK. and Printed Canada Peter Vassilopoulos Boating Guide to PNW Guest Moorage docks docks destinations Docks Cover OPTION NEW 2022.indd 2022-03-20 AM • Anchorages • Sunshine Coast • Colour Diagrams • Aerial Views GPS Covering the Coast from the San Juans to Ketchikan Alaska Peter Vassilopoulos and Marine Parks $34.95 Clockwise:At the Bunsby Islands; anchorages anchorages This edition through out the Pacific Northwest. It includes easy references to the Gu National Park Reserve and covers the San Juan Islands, Desolation Sound, Islands and places south to north along the way etween these destinations, as well as the main waterways to Prince Rupert, southern tip of Alaska. Like its companion guide it returns south via the West Coast of Vancouver Island, featuring Quatsino, Kyuquot, Esperanza, and Numerous maps and diagrams include descriptive icons showing th recommended anchorages, coves and bays, so that at glance is possible hook overnight. The information is provided in a user-friendly format, taking the mariner from one anchorage successive, geographic progression. “We have been sailing our 36 ft Catalina in the San Juans, Gulf Islands and Desolation Sound for 25 years. We have used numerous three-dimensional perspective of passages and harbors. The information and the way the book flows and the details that provided de-stresses our journeys and gives us more confidence passages cruising life better !” –Jane Braun, Sunshine Coast. Marine Parks The Guide to Popular Pacific Northwest Destinations PETER VASSILOPOULOS Anchorages and parks in the San Juan and Gulf Islands, Desolation Sound, West Coast of Vancouver Island, Haida Gwaii and the Inside Passage of British Columbia AND Packedwithcolourphotographsandinformation Anchorages Anchorages All available at https://shop.opmediagroup.ca/collections/bookstore

Starboard Bifurcation Buoy

GO BOATING

FAIRWAY BUOYS

A fairway buoy indicates safe water, and all types have red and white verti cal stripes. They are used to mark land falls, channel entrances or the centre of a channel. They may be passed on ei ther side but should be kept to the port (left) when proceeding in either direc tion. They have a white light Mo(A) 6s or (LFl) 10s (if equipped) and if unlit, they may have a spherical top with a single red spherical topmark and letters but no numbers, with white retroreflec tive material.

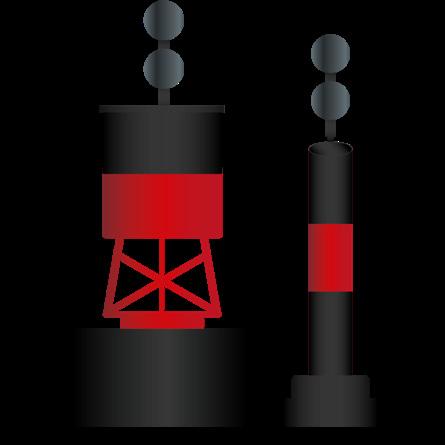

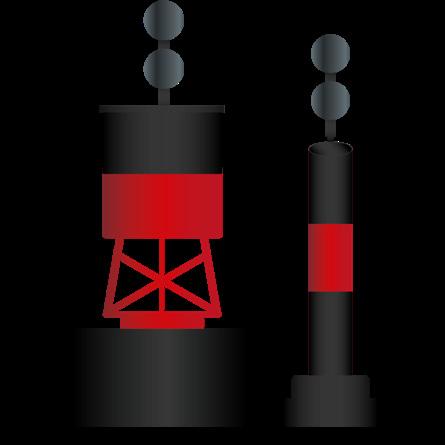

CARDINAL AIDS

Cardinal buoys are black and yellow. They indicate the location of the saf est or deepest water by referencing the cardinal points of the compass. Like the compass, there are four cardinal buoys: north, east, south and west. They display identification letters and may have white retroreflective material. The points of the two topmark cones indicate where to find safe water. Lights are white. If unlit the cardinal buoy will normally be a spar (cylinder) shape al though other shapes may be used.

NORTH CARDINAL BUOY

the safest water exists to the south. It is coloured black and yellow in approxi mately equal areas above the waterline, the top half of the buoy is yellow and the lower half black. If present, the top mark has two black cones, one above the other, pointing downward. If it carries a light, it is a group quick flashing six plus long flash (Q(6)+LFl) 15s or group very quick flashing six plus long flash (VQ(6)+LFl) 10s.

WEST CARDINAL BUOY

ISOLATED DANGER BUOYS

An isolated danger mark buoy is used to indicate a hazard to shipping such as a submerged rock or wreck which has navigable water all around it. It is erected or moored above the hazard so vessels should keep away from the buoy—keep in mind the buoy’s move ment in a strong current. They are black in colour with one red horizontal band and have a white light, group Fl(2) 5s or group Fl(2)10s (if equipped). Oth erwise, they may have topmarks with two black spheres, one above the other, and have letters, but no numbers, and white retroreflective material.

A north cardinal buoy is located where the safest water is to the north. It is co loured black and yellow evenly distrib uted above the waterline, with the top half of the buoy black and the lower half yellow. The light is a quick flash ing (Q) 1s or very quick flashing (VQ) 5s and a topmark may have two black cones, one above the other, pointing upward.

EAST CARDINAL BUOY

An east cardinal buoy has the safest water to the east. It is coloured black with one broad yellow horizontal band and displays identification letters. A topmark may have two black cones, one above the other, base to base. If it carries a light, it will be a group quick flashing three Q(3)10s or a group very quick flashing three VQ(3) 5s

SOUTH CARDINAL BUOY

A south cardinal buoy is located so that

A west cardinal buoy is located so that the safest water exists to the west. It is coloured yellow with one broad black horizontal band. If it carries a topmark, the topmark is two black cones, one above the other, point to point. The light, if carried, is a group quick flashing nine Q(9) 15s light or a group very quick flashing nine VQ(9) 10s

BUOY LIGHTING

Here is a quick legend on buoy lighting abbreviations. These are the ones refer enced in this article, but there are more out there for other specific indications.

Fl: A flashing light.

Fl(x): A group of flashes in a period.

LFl: A long flash (generally two seconds or more).

24 JANUARY 2023

COLUMN

Isolated Danger Buoys

Fairway Buoys

Cardinal Aids

Downstream

Upstream

Fl(x + y): A combo of flashes repeating. For example, Fl(2 + 1): would be a repeating pattern of two flashes followed by one in a given period.

Q: Continuous quick flashes, usually 50 to 60 a minute.

Q(x): A group of quick flashes in a period.

VQ: Continuous very quick flashes, usually 100 to 120 a minute.

VQ(x): A group of very quick flashes in a period.

Mo(x): A combo of flashes and long flashes to represent Morse code.

Mo(A): (a flash followed by a long flash in a period) is often used to show safe water.

These abbreviations are usually followed by Xs, representing the period of time in seconds in which the flash will repeat. For example, Fl(5) 15s means that the buoy will give off five flashes every 15 seconds.

AND THIS IS just the beginning! Spe cial buoys and fixed aids to navigation, such as beacons and ranges, will be cov ered in my next article.

Without knowledge of these systems, entering a harbour can not only be stressful but also dangerous. But while familiarity comes with practise it is al ways prudent to have an aids to naviga tion chart in the cockpit, found in Ca nadian Coast Guard’s quick reference guide 22 in their Aids to Navigation section.

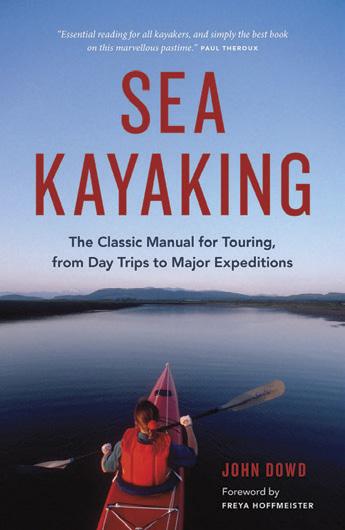

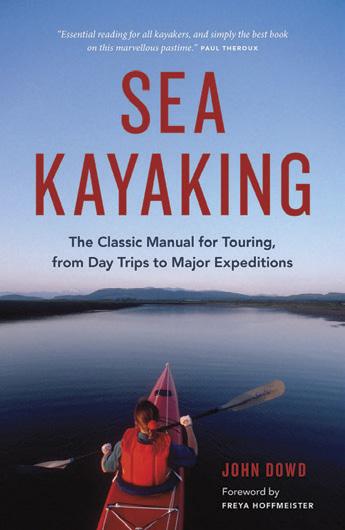

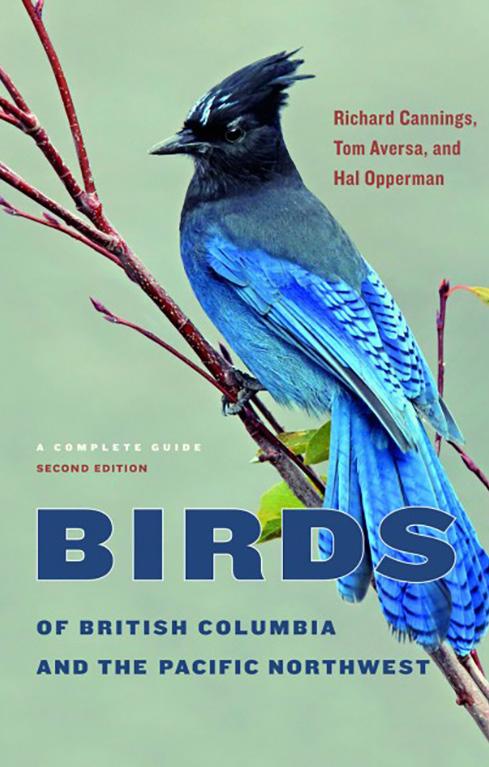

Liza Copeland is the award-winning author of four best-selling books on cruising world wide including a recently updated edition of her and husband Andy’s how-to Cruising for Cowards. Visit her website at aboutcruising.com

JANUARY 2023 - 25

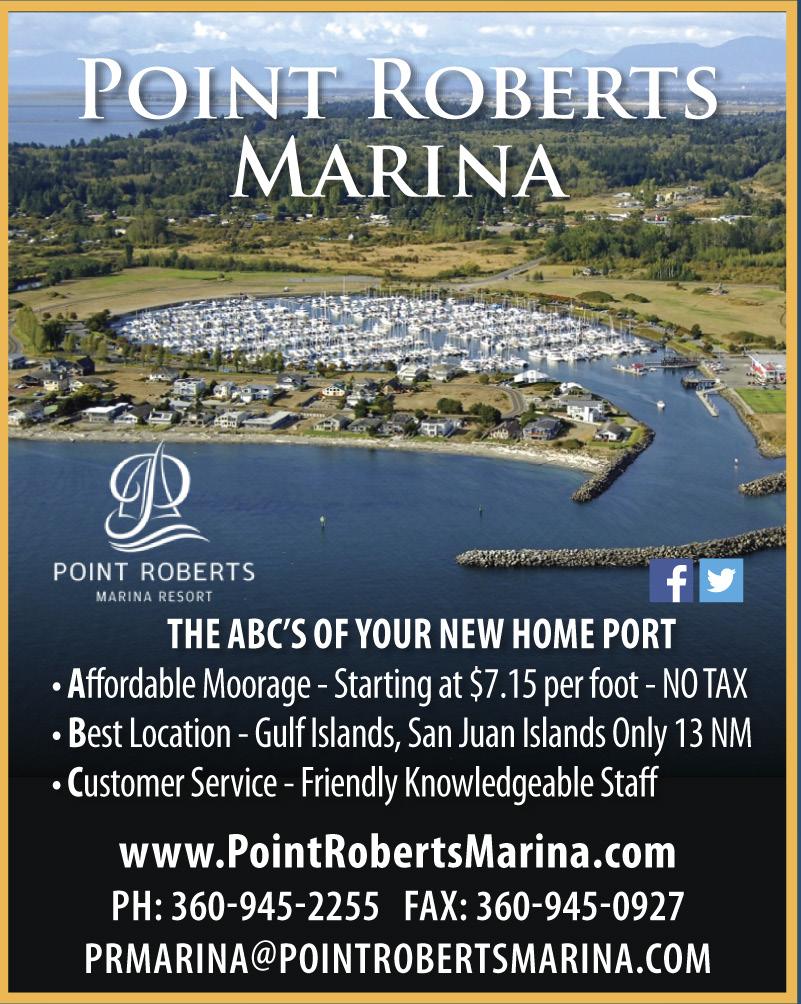

www.PointRobertsMarina.com PH: 360-945-2255 | FAX: 360-945-0927 | PRMARINA@POINTROBERTSMARINA.COM So close you are already there... P oint R oberts M arina Deep Water Entrance • US Fuel Prices • Laundry and Showers Convenience Store • US Customs Clearing • Pet Friendly Over 700 slips available right now MARTIN MARINE Loc ATE d AT 1176 W ELch S TREET, No RT h VAN cou VER , B c 604-985-0911 | Toll Free 1-866-985-0911 | info@martinmarine.ca North Va N cou V er’s FaV ourite Mari N e s tore si N ce 1964 FREE PARKING Be safe in every kind of marine environment. Move freely and comfortably with Personal Flotation Devices that can inflate manually, automatically, or hydrostatically. EVERY COLOUR, EVERY STYLE, MASSIVE INVENTORY! INFLATABLE PFD S

BY DEANE HISLOP

Laura Bay, Broughton Island

A popular anchorage all to ourselves

It had been a few years since we last visited Laura Bay and with the weather forecast for the next couple of days calling for rain, 15 to 20 knots of wind and a day time temperature of 16º C it seemed like a suitable time to take shelter in the protection of this beautiful little anchorage. It would also provide an opportunity to do some prawning, perform some preventive main tenance and get caught up on my reading.

We departed Monday Anchorage, Tracey Island, and set a course east in Misty Passage, then wound our way through Blunden, Cramer and Raleigh passages. Transiting Burden Passage we saw a large pod of whitesided dolphins approaching. I set the rudders straight and throttles at 7.5 knots and we proceeded to watch over 100 of these enchanting mammals jumping, surf ing and playing in our wake for a mile and a half.

26 JANUARY 2023

COLUMN GUNKHOLE

I

Our favourite anchorage is northeast of the unnamed islet.

JANUARY 2023 - 27

ALTHOUGH IT WAS the last week in June, a bit early for returning salmon to show-up in the area, the VHF ra dio was all abuzz about how a few had been recently caught in Cramer Pas sage. As an avid angler, I entered a note in the log for future reference.

As we approached the anchorage we deployed two crab pots. During our visit a few years prior, we were success ful in putting two healthy portions of succulent shrimp and spot prawns on ice, and the anticipation on board was high for more of these delicious crus taceans.

LAURA BAY OFFERS two separate areas as possible anchorage sites. The first is in the mouth of Laura Bay. The area shoals quickly and is a bit exposed, but offers a beautiful view across the passage of Deep Sea Bluff and the Miriam Range.

Our preferred anchorage is to the north in the small cove formed by Broughton and Trivett islands. The cove is surrounded by forest with an unnamed islet in the centre. The islet’s crown of trees reminds us of a castle rising above a moat. Because of the limited swing room, most visitors set their anchor north of the islet and run a stern tie to Broughton Island.

This is a popular small anchorage and we hoped it would have room for us. We were delightfully sur prised to find the anchor age void of other boats—a benefit of the early season visit—and we had it all to ourselves. The anchor was set in 26 feet of water over a good sticky bottom northeast of the islet and Easy Goin’ swung lazily on the hook.

After the pots had soaked for three hours, we weighed anchor and headed out to check them with great anticipa tion. It was a bit disappointing when

28

COLUMN GUNKHOLE

2 3 1

1. “Castle” Islet.

2.

White-sided dolphins playing in our wake.

3.

A tree lies across the shallow channel between Broughton and Trivett islands.

PENPHRASE PASSAGE

LAURA BAY

we only had caught three prawns, but it didn’t discourage us, so we relocated to a promising location nearby and set the pots to soak overnight.

We returned to our private anchor age and reset the hook. I noticed the current in the cove was flowing through the anchorage from the head of the cove, regardless of the tide, so during a sun break I launched the din ghy to investigate. The water was flow ing through the shallow channel be tween Broughton and Trivett islands. We would have explored further, but there were two trees lying across the narrow channel blocking us from tak ing the dinghy through to Penphrase Passage.

Motoring back to Easy Goin’, a hum mingbird attracted to my red PFD buzzed right up to my face. We have hummingbirds at home, but it was the first time I had been eye to eye with one. It must have thought I was a large

flower. A good thing I was wearing my protective eyewear, sunglasses.

It rained on-and-off throughout the day with glorious moments of warm sunshine and the predicted wind was absent in the well protected anchor age. Late in the afternoon we were treated to a beautiful rainbow that terminated in the anchorage. Arlene asked if this was a sign that our prawn ing luck was about to change?

The following day was more of the same, overcast with intermittent rain showers. After breakfast it was time to check for our pot of gold. The haul produced a mixed limit of spot prawns and shrimp. The rainbow the day be fore must have been an indication of things to come. We refreshed the bait and retuned the pots to the bottom in hopes of a second limit.

Back in the anchorage, a young bald eagle who was perched in a tree on the islet watched us clean our catch. We

believe he was looking for a hand-out, but the tails were for us to enjoy and the heads for the crab trap.

The balance of the day was spent re laxing, doing preventive maintenance and waiting for the next pull of the pots.

Dinner was steak and potatoes pre pared on the grill and shrimp cocktails paired with one of our favourite bot tles of wine, making the perfect ending to a beautiful day.

WHE N YO U GO Chart: 3515 Nearest Marina: Echo Bay

JANUARY 2023 - 29

Trivett Island

Broughton Island

Small channel blocked by tree

SEE YOU IN SEWARD

A fantastic boating town tucked into Southcentral Alaska

By Norris Comer

By Norris Comer

Regardless the bearing you cruise— from Prince William Sound to the northeast, Kenai Fjords National Park to the southwest, or from across the Gulf of Alaska to the east—Seward of Southcentral Alaska is a charming coastal town tucked in the beautiful Resurrection Bay fjord. Many of the nearly 3,000 year-round residents make their livelihoods off the water: fisher folk, professional mariners, US Coast Guard servicemembers, seafood indus try workers, marina and fuel dock op erators, ecotourism companies, marine scientists and even Olympic swimmers. Notable Seward resident Lydia Jacoby (18) won two medals (silver and gold) in women’s swimming in the 2020 To kyo Olympics.

Seward’s boat-friendly location makes it a true hub for adventure. The town is connected to Alaska Highway 9 and features a prominent Alaska Railroad station, airport and large cruise ship terminal. Seward’s population swells during the busy summer months. Buzz ing, international crowds roam the downtown drag’s restaurants and bars, souvenir shops and greenspaces, but its Seward’s deep-rooted history that brings depth to this remote place.

BOATER BASICS

Seward is one of the most beautiful boat towns in all of Alaska and the ideal launching point to explore the adjacent Kenai Fjords National Park. I’ve had the pleasure of doing so a few times. It’s a region of the world full of natural wonder and amazing remote anchor

Rages, incredible calving glaciers, feeding whales, raucous seabird rookeries and more. In my estimation, the most fortu nate people alive are those at the helm of a Seward-based boat with a whole summer of cruising ahead of them.

The town is also ideal from a cruising support standpoint with grocery stores, marine suppliers, boatyards and pretty much whatever else you may need. A big bonus is that Seward is connected to greater civilization by road, train and airplane, whereas many similar com munities are not.

But getting to Seward by boat is no simple matter. Located hundreds of miles across the wild Gulf of Alaska from the relative shelter of the Inside Passage, Seward is a goal for true blue water cruisers (unless your noble vessel rides upon a trailer). One could write an entire article with multiple inter views on the ins and outs of crossing the Gulf of Alaska, but suffice it to say that a crossing is a major nautical feat and not to be taken lightly.

As far as Seward itself, the large and centrally located Seward Boat Harbor is your moorage target. The entrance to this public marina is straightfor ward although it can be busy with fish ing charters and tour boats zipping in and out. This full-service marina caters to commercial, recreational and mili tary boats with slips aplenty and sidetie dock space complete with pumpout station, power, restrooms, laundry and fuel docks. A full-service boatyard is also available with 50 and 330-ton boat lifts.

Even during ideal summer weather, a Seward-based boater is operating in the rugged North Pacific. Outside of Res urrection Bay, the breathtaking fjords make landfall an adventure and once ashore you’re on your own. Boaters should be confident in their ability to handle unexpected 50-knot winds and self-sufficiency is a must. Fortunately, there are many moorages if shelter is

32 JANUARY 2023

1 2

needed. I’d strongly recommend identifying specific moorages along your planned cruising routes as Plan Bs for when unexpected weather rolls in.

Local knowledge is priceless in remote areas and buying a local salt a beer at the Breeze Inn—a locals-focused bar near the marina—is highly recommended. Don’t be too pushy though, as for some locals their hard-earned knowledge is not for sharing. But if you pick up the tab and they like you, the odds tend to lean in your favour. As far as my knowledge as a non-local goes, note that rounding exposed Cape Aialik to the southwest is a part of a boater’s journey from Seward to Kenai Fjords National Park. Snotty weather at the Cape is quite often the most harrowing part of such a transit— proceed mindfully.

WALKING AROUND THE TOWN

Part of what makes Seward so great is that a lot of the fun is close at hand and easy to get to. Downtown proper is about a kilometre from the marina and it is a nice walk. During summer, there is a shuttle service between the train station and downtown about every 20 minutes.

For the lovers of ocean life, the Alaska SeaLife Center is a worthy sight. The centre is a combination of an edu cational aquarium, marine research laboratory and wildlife rehabilitation organization with tons of interesting information. It’s all possible thanks to a partnership with the adjacent Uni versity of Alaska Fairbanks—Seward Marine Center. Here you’ll rub elbows with shiny-eyed graduate students in waders releasing sleeper sharks into re habilitation tanks.

1. A hiker at the iconic Exit Glacier.

2. Cruising in Kenai Fjords National Park.

3. A boardwalk with shops and restaurants lines the small boat harbour in Seward.

4. The main underwater tanks at the Alaska SeaLife Center.

JANUARY 2023 - 33

4 3

1. Galyna Andrushko; 2. Craig Wolfrom; 3. Scott Bateman/Dreamstime.com; 4. Norris Comer

A casual walk is my recommended method to enjoy downtown Seward. Lazily connecting the dots between historic markers and the many painted murals adds a bit of structure to your stroll. Naturally, there is a William H. Seward Monument to honour the man who made Alaska part of the US, and it can be found at the intersection of Ad ams Street and 4th Avenue. Mile 0 of the Iditarod is on the south waterfront of downtown near the Alaska SeaLife Center and a Centennial Statue that commemorates the historic trail’s blaz ers, both human and canine.

A big draw of Seward is the people. During the summer there’s usually events or live music to be found around town. I remember lounging in the Yu kon Bar one Thursday night, minding my own business with my whiskey, when suddenly 50 young kayak guides in Hawaiian shirts invaded the place as DJ Handkerchief set up his spin table to throw down the beats. I left several hours later grinning ear-to-ear.

Seward hosts Opening Day festivities, the Seward Mermaid Festival (a hardy lot those Alaskan mermaids), fishing derbies and more. The most iconic of these annual events is probably the Mount Marathon Race. Held during Fourth of July festivities, gluttons for punishment race up and down Mount Marathon, which towers over town. If you get caught up in this event, don’t be surprised if you see dirt, mud, shale and blood. The prevailing cavalier attitude is that if you make it out of the Mount Marathon Race unscathed you should have tried harder.

FOOD SITUATION

The food and drink situation of Seward is excellent. The influx of business from the summer visitors probably helps sus tain the vibrant hospitality scene.

Alaskans are like their Pacific North west neighbours in their love of craft beer and strong coffee. The Seward Brewing Company is a standout local institution with a varied menu and in teresting house brews to try. The nearby

Yukon Bar and Seward Alehouse have more of a local pool table dive flair, but can you really say you visited Seward without at least peeking in? For cof fee, the Resurrect Art Coffee House is a must. This cosy, high quality café features comfy home-style seating and local art for sale.

Another quintessen tial Seward establish ment is the Flamingo Lounge (previously Thorn’s Showcase Lounge), a promi nent bar and restau rant with endearingly garish vintage inte rior styling across the street from Yukon Bar. This place is famous for its Bucket of Butts—essentially a pile of delicious fried halibut (“butt”).

Most other cuisines are represented in town in some delicious form: Thai (Woody’s Thai Kitchen, very good!) and Greek (Apollo Restaurant) being the standouts. Chinooks Seafood & Grill is an upscale on-the-water seafood option right by the marina. It’s a bit of a distance from town, but the Goliath Bar & Grill housed within the Resur rection Roadhouse is a great place to grab a steak on a special occasion if you can figure out how to get a lift out there. Be sure to check before heading out as many of these restaurants are seasonal or have irregular schedules.

The Pacific Mills Pulp and Paper Plant, 1941.

THE GREAT OUTDOORS

Seward is a great town, but what makes it world class is the raw nature in which it is set. The aforementioned Mount Marathon features a steep butt kicker of a trail with great views at the top. The trailhead is not far from downtown, similar to the Lowell Canyon Trailhead. The Lowell Creek Waterfall is a large waterfall thundering just south of the Alaska SeaLife Center and worth a look.

If budgets allow, there is no end to the kayak tours, fishing charters, sea plane adventures and dog sledding ex periences. I worked with the company

34 JANUARY 2023

Norris Comer

Seward

North Pacific Expeditions last summer and they offer upscale, incredible four and five-day trips into Kenai Fjords Na tional Park out of Seward. All of these come down to personal preference, time constraints, budgets and planning. The number of companies is too staggering to list here, but a google search will show you a number of options.

A great natural area near town is the Exit Glacier trail system. These trails cater to all athletic levels and lead to and around Exit Glacier and the Harding Ice Field above. Heads up, when I last tried in June most of the Harding Ice Field trail was snowed in and stopped me. I also stumbled upon a large moose that startled the bejesus out of me. It’s about 19 kilometres out of town, but you can arrange a ride with Exit Glacier Shuttle as I did if you’re without a car. You’ll note a lot of posted information about how far Exit Glacier has retreated over the last few decades. A painted mural titled Remembering Exit Glacier (2007) honours the dying ice giant’s once vast extent down the valley—a sight locals over 50 years old recall vividly.

Seward is beyond the range of all but the most adventurous boaters (unless you put the boat on a trailer and drive north—an adventure in itself) but if you get the chance to cruise here you will find a lively and friendly commu nity and stunning natural beauty.

When You Go

Seward Boat Harbor monitors VHF Channel 17. Office hours are 08:00 to 17:00, Monday through Saturday with sum mer hours being all week. Phone: 907-224-3138.

More info is available online at cityofseward.us.

JANUARY 2023 - 35

Exploring Kenai Fjords National Park.

By Len Sherman

36 JANUARY 2023

III Sails the Northwest Passage Remembering a cruise along the top of the world

Dove

JANUARY 2023 - 37

The skipper with his vessel.

years ago, Winston Bushnell (skipper), George Hone (first mate) and I (artist/ writer) sailed the Northwest Pas sage aboard Dove III. Winston was a well-seasoned mariner, having sailed around the world during the ‘70s with his family aboard the small sailboat, Dove, which was rolled over off South Africa by a 60-foot wave. George was an experienced sailor. Although I was living on a 42-foot ketch, Dreamer II, I was still a novice. Winston built Dove III (Brent Swain design) spe cifically for sailing the Northwest Passage. Only 27 feet long, she was made of steel and had a shallow draft, which would enable her to battle the remorseless ice while tightly hugging the shore.

Winston’s first plan was to sail the Northwest Passage with only one crewmember. I’m not sure why he de cided to take on more crew, especially someone like me, but maybe it’s like he said, “At least you won’t mutiny.” I think that sums it up best.

On May 8, 1995, Dove III left Na naimo, BC in her wake. I remember wondering if we would ever return. As we sailed up the inside passage to Prince Rupert, except for an occasion al squall, the going was very pleasant and relaxing.

AFTER LEAVING PRINCE Rupert, we were soon sailing past Tow Hill on Haida Gwaii, which brought back fond memories of camping at its base. Once land had completely disap peared and only sea and sky remained, the wind reached gale force velocity and the ocean went berserk! Although the boat pitched about like a drunken sailor for a few days, she handled the storm well, which gave me added con fidence as we headed farther and far ther north.

A R C T I C O C E A N

Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands seemed dark and foreboding until we reached the first of several designated destina tions, Dutch Harbor. After being at sea for almost three weeks, it felt great to get in touch with our loved ones back home. We stayed longer than we wanted due to a violent gale blowing across the Bering Sea. Anxious to be on our way, we set sail with high hopes that the wind would die down, but it did just the opposite—it blew harder. We were forced to heave-to in two to

six-metre seas. The fierceness of the storm blew us off course and we drift ed toward the Pribilof Islands. I hadn’t really been worried about our safety until a concerned looking Winston ex claimed before my turn at the wheel, “Keep your eyes peeled Lenny! One of those waves could roll us over!”

A few thoughts crossed my mind: How long would the ferocious weather last? How long before a rogue wave the size of a semi knocked us over? How long would we survive if we lost the boat?

38 JANUARY 2023

25

Nanaimo

Haida Gwaii

Dutch Harbor

Pribilof Is. Nunivak Is.

BERING SEA

Nome

Point Hope Shishmaref

Cape Lisburne

Kasegaluk Lagoon

Akoliakatat Pass

Utqiaġvik

Prudhoe Bay Herschel Is. Tuktoyaktuk

ANCHORAGE GULF OF ALASKA

BAY

BAFFINISLAND

DAVIS STRAI

west” town. Nome was established during a gold rush around 1901. After a few days on land, we headed toward the ice pack and two days later, after crossing the Arctic Circle, we were in the thick of it! Cutting our way through the ice was a little unnerving and we were soon forced to retreat to the village of Shishmaref, located on tiny, banana-shaped Sarichef Island.

Two days later, after the wind and the sea had calmed down considerably, we were back on course and finally dropped the hook in a quiet little bay off Nunivak Island. Now, halfway across the Bering Sea, we were grateful for a few moments of tranquility after that tremendous storm.

I WAS REALLY looking forward to our next destination: Nome, Alaska. En tering the little port was a little tricky (only 1.5 metres at the entrance) but

Winston, with a little advice from the US Coast Guard vessel, Storis, soon had us safely inside the protected moorage and tied to a small dock.

While waiting for the ice to break, I enjoyed strolling around Nome, pho tographing and videoing the sights, which looked much like an old “wild

TWHEN WE MANAGED to reach Point Hope the next day, the first of many curious Inuit hunters arrived. They told us the sea was free of ice all the way to Cape Lisburne. Upon arrival at the US DEW Line aircraft base, established during the Second World War, we were greeted by the overseer. The overseer treated us, like many of the people we met, to a great meal and much needed showers. Our short stay was a little unsettling because only a tiny stream kept the approaching ice away from the hull. When a sudden squall roared in over the mountains and blew the ice away, we left in a hurry. Hoping to es cape its fury, we tucked into Thetis Creek, which almost ended our voyage. The river was very shallow, and we were almost swept onto a sandbar.

Manoeuvring through tight leads (long, narrow gaps in the ice) can be very tricky because they could abruptly end or suddenly snap shut. We took turns up in the ratlines, point ing out the way. And, as luck would have it, we came to a dead end and were forced to tie to a large chunk of ice. When the lead reopened, we almost made it to Kasegaluk Lagoon, before being stopped once again. It seemed

JANUARY 2023 - 39

0 150 300

Nautical Miles

Arctic Circle

Cambridge Bay

Jenny Lind Is. Gjoa Haven

Bellot Strait

Pond Inlet

Clyde River

Pangnirtung

HUDSON

like I’d just crawled into my sleeping bag when Winston hollered, “Time to go boys! A little gust of wind just blew the ice out! Let’s try to get into the la goon before it closes in again!”

It was a good call on Winston’s part because the ice blew in with a ven geance and stacked up on the shore about three to four metres high. If we had stayed, little Dove III would have been knocked over and possibly crushed—a tragic end to our voyage. Over the next few days, we played cat and mouse with the ice, ducking in and out of Kasegaluk Lagoon.

July 8, two months after leaving Na naimo, we reached Akoliakatat Pass, another cut leading into the seemingly endless lagoon. Surrounded by swirl

ing ice at the entrance, George at the bow with a pike pole, I yelled down from the ratlines to Winston at the helm, “Give’er!”

Winston opened the throttle as two huge ice floes rapidly closed our nar row gap to safety. We didn’t quite make it! When the bow rose out of the water and the boat heeled over on its side, I wrapped both arms around the mast and held on for dear life! Fortu nately, the boat slid across the ice and soon righted itself. Even though we were inside the lagoon, it took some time to escape the ice that was flowing in right behind us.

WHEN WE FINALLY bashed through the ice to the bustling town of Bar

row (now known as Utqiaġ vik), we were greeted by a sign: BEWARE OF POLAR BEARS. After picking up some provisions, we set sail for our last American port, Prudhoe Bay. Upon arrival, we weren’t allowed to go ashore, but they did give us enough fuel to reach Herschel Island, Yukon. It felt great to set foot in Canada again and explore the old abandoned whaling station, which had been turned into a tourist museum. As I tromped about the island, I discov ered an old cemetery. Over many win ters, the frost heaves had pushed up a casket and I could see the skull and some bones of a person simply named John—the name had been carved into an old, weathered cross.

40 JANUARY 2023

Toasting King Neptune and staying warm in the cabin of Dove III.

The sea was relatively ice free by the time we reached Tuktoyaktuk and while there, I met some fellow artists who were carving soapstone sculptures. It would have been nice to stay longer, but speed was a priority if we were to get through the Northwest Passage before winter arrived.

Upon arrival at Cambridge Bay, a friend of Winston’s, Chris Strube took us flying in his small plane to check out the ice conditions. The flight was quite exciting, especially when the plane suddenly swooped down over a herd of muskox. Because the ice had yet to break further east, we stayed for five days.

After motoring by Jenny Lind Island, another abandoned DEW Line sta tion, we were forced to motor back. I had a lot of fun exploring the empty buildings and going inside the enor mous parabolic aerial. Unfortunately, while climbing into the dinghy to row back to the boat, I had a misstep, which sent my video camera sliding across the back seat and into the sea! Like losing a lover, it almost broke my heart.

HEADING TOWARDS GJOA Haven, we were surprised by the lack of ice; it seemed to have mysteriously van ished! Once there, I met a renowned Inuit sculptor, Judas Ullulaq. Since he couldn’t speak English, his grandson translated our conversation and I was amazed that he was more interested in showing me his freezer full of frozen fish than talking about his art—such a humble man—a joy to meet.

Shortly after leaving Gjoa Haven we met up with the Croatian Tern, with Mladen Sutej at the helm. We rafted together and learned that they were planning to circumnavigate North and South America, which they even tually did. We were a little worried as we neared the infamous Bellot Strait located at the northern most tip of mainland North America. We mo tored through the narrow passage dur ing slack tide and big bad Bellot Strait

(which runs eight to nine knots and can change direction at any time) was on its best behaviour, so we didn’t have any problems.

ON AUGUST 20, while Dove III sliced through a skim of ice, the realization that winter would soon be arriving began to sink in. And to top it off, we were introduced to a northwest erly full-blown gale reminiscent of the Bering Sea. When we finally reached Pond Inlet, the wind was blowing so hard, we had to bypass it in favour of Albert Harbour. When we were able to return to Pond Inlet, we anchored near a massive iceberg. When the berg began breaking up huge chunks of ice drifted toward our little boat—it was time to leave!

It was a long haul down Davis Strait to Labrador and when the wind

coating of ice when we left two days later. Winter pursued us like a hungry polar bear.

As we continued down Davis Strait, between the fog and stormy condi tions, the situation became more per ilous. Although 80 kilometres out of our way, Winston decided to head for Pangnirtung. Hoping for calmer weather when we returned to Davis Strait, we were instead greeted with the tail end of a hurricane, and with waves occasionally breaking over the entire boat, Winston decided to head back to Pangnirtung and leave Dove III there until spring.

While spending three days win terizing Dove III, we became good friends with Roy Bowket and his Inuit wife Annie. They were won derful hosts who not only gave us an apartment to stay in, but also treated us to some great meals.

I remember, after skid ding Dove III ashore and securely tarping her, I looked back over my shoulder as we left and felt a touch of mel ancholy leaving behind my refuge from so many storms.

picked up (combined with thick fog) the going became very dangerous, es pecially during the night. An iceberg could suddenly pop out of nowhere at any moment! Forced to tuck in at Clyde River, Baffin Island, we made friends with the local RCMP officer Jerry Smith and his wife Sandy who fixed us mouth-watering Belgian waf fles. The boat was covered with a thin

I RECENTLY SAW a photo of Dove III, and after 25 years, she’s look ing just about as beat up and old as me. Winston built another boat and at age 82 is still sailing around the BC Coast in the summers. George just remarried and is planning to get another boat. And me, never much of a sailor, I still have my dinghy from when I lived aboard Dreamer II. Maybe I’ll rig a sail on her and cruise around the nearby lake come summer. If I wait till the lake starts to freeze over, I can shut my eyes and imagine I’m once again aboard Dove III as she crunches through the ice of the Northwest Passage.

JANUARY 2023 - 41

42 JANUARY 2023

PISCES VI

Touring this locally designed submarine reveals small spaces and big technology

By Jonn Braman

By Jonn Braman