Long Way Home From Mexico

Gambier island

WEST COAST POWER & SAIL

SINCE 1968

Long Way Home From Mexico

Gambier island

WEST COAST POWER & SAIL

SINCE 1968

CARIBBEAN CRUISE

Saint Lucia to Saint George’s HAIDA GWAII

Exploring the Wild Coast

•

•

CHARTER: HAIDA GWAII

Exploring these magical islands aboard a 138-foot catamaran By

Hans Tammemagi

CARIBBEAN CRUISE

Two weeks in the Windward Islands—Saint Lucia to Saint George’s By Peter Lang 40

SAILING THE CLIPPER ROUTE

and daughter’s

Kayleen VanderRee

DOROTHY'S

Dorothy showed off her new life throughout the summer of 2024 for sailors young and old By Marianne Scott

ost people have heard the joke about the two types of boaters. It goes like this: “There are two types of boaters out there, those who have run aground and those who will.” As far as jokes go, it’s pretty accurate. Most boaters I know have hit some under water “thing” at some point in their lives. I won’t go so far as to call it a rite of passage (it really should be avoided at all cost) but I will say that once you do it, you sure try not to do it again.

’m sure most readers are familiar with Lin and Larry Pardey’s famous phrase, “go small, go simple, but go now!” As the owner of a simple, 27-foot sailboat that—while often in need of minor maintenance—is always ready to go, I couldn’t agree more. Small and simple is good. It allows for ease of use and reduces cost. It means small mistakes lead to small lessons and small repair bills. If you’re thinking of getting into boating, go small, but go for it.

penny of that $900.

her, but polishing and varnishing are frivolous extravagances, and if looked at askance, his boat has something of a pirate ship appearance to it.

On the other hand, I recently had the opportunity to live the good life aboard a “big boat” while on a week-long charter in French Polynesia. To anyone who hasn’t chartered a yacht in a tropical place I say, go big and go now!

I don’t mean to make light of the costs. Chartering is not cheap by any means, and it held me back from considering it for many years. But if you’re planning a getaway, the price of a week-long charter is actually in line with many other vacations, especially if you have a crew of friends or family to share the costs.

But those aren’t the only two types of boaters out there. A recent cruise aboard a friend’s 30-foot sailboat got me thinking about this. My friend is the fastidious, cautious type. Our plan was a short sail to Thetis Island for supper at the pub, a night on the dock and pastries at Telegraph Harbour Marina the next morning before returning home. Every detail was meticulously planned well in advance. My friend relies on multiple apps for wind, tide and weather information and utilises multiple systems for navigation. Very little is left to chance. The “over-planner” is a common type of boater and there is nothing at all wrong with that approach.

The article covering my trip will appear in an upcoming issue of Pacific Yachting so I won’t go into too much detail here, but we gathered a crew of eight friends and partners and spent seven days aboard a 40-foot catamaran exploring the crystal blue lagoon of Raiatea and Taha’a. A full cost breakdown will appear in that upcoming article, but the charter itself, for eight people, was less than $900 per person—very reasonable, in my opinion. The trip was worth every

On the other hand, there is the spontaneous “go with the flow-er”—another type of boater who I run into regularly (metaphorically speaking). As we loaded the boat and engaged in final preparations for our one-night cruise to Thetis Island, a dock neighbour stopped by for a chat. “Ol’ Jim” we call him. He’s a regular down at the dock. He keeps his sailboat in working condition and certainly takes pride in

The other factor that originally held me back from chartering was the anxiety around skippering an unknown boat in foreign waters, and in the days leading up the trip there were certainly nerves, but the conveniences of a modern boat make maneuvering relatively easy and the wealth of information online and in books makes navigating and trip planning straightforward. In the end, our trip went smoothly, and the experience gained was invaluable as I consider future trips and charters.

A free spirit like Jim doesn’t need planning or preparation, so when we told him we were headed to Thetis Island later that morning he said, “great, I’ll join you! Let me fill up my fuel tank and I’ll be ready to go.” My friend looked up from his checklist and cocked his eye at me. When it was time to go, I asked Jim if he wanted a hand leaving the dock. “No, no,” he said. “I always singlehand.” Then, “follow me, I know a shortcut.”

In this issue, we’ve included two stories on two very different charter experiences—both positive. The first, on page 26, is a six-day charter to Haida Gwaii. Hans Tammemagi recounts his adventure aboard Cascadia, a 138-foot catamaran, as he discovers Haida history, reconnects with nature and indulges in bountiful West Coast cuisine.

Jim motored out of the dock and had his sails up in short order. We quickly followed suit. Thankfully, Jim’s “shortcut” was already part of the plan and we followed him through easily. He arrived at the marina a few minutes ahead of us and I watched as he jumped off his boat with lines in hand, only slightly bumping the dock as he came to rest. We ate an early supper with Jim and afterward he untied and motored home. “You aren’t going to spend the night?” we asked. “Oh, no. I want to catch the sunset on my way home.”

We’ve also published Peter Lang’s story (page 32) on a two-week charter in the southeast Caribbean, exploring the Windward Islands from Martinique to Grenada. Peter’s trip was highlighted by epic conditions, delicious meals and human connections that are so often found when travelling the world, particularly by boat.

I’d like to think I fall somewhere in between these two types. I do plan my trips in advance using Windy, Navionics and a chart plotter. I want everything to go smoothly, but I am open to changing plans according to wind and whim.

If you’ve considered an overseas charter, but have yet to take the plunge, I hope our chartering issue provides the inspiration required. I can vouch that despite the logistics involved in organizing a trip like this, it’s worth it. So, go big, go now!

—Sam Burkhart

Neither type is right or wrong, but I would suggest that one type is more likely to avoid running aground, at least for a little longer.

—Sam Burkhart

EDITOR Sam Burkhart editor@pacificyachting.com

AFTERGUARD EDITOR Sam Burkhart editor@pacificyachting.com ART DIRECTOR Arran Yates AD COORDINATOR Rob Benac COPY EDITOR Margaux Perrin

DIRECTOR OF SALES Tyrone Stelzenmuller 604-620-0031 tyrones@pacificyachting.com

DIRECTOR OF SALES Tyrone Stelzenmuller 604-620-0031 tyrones@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER (VAN. ISLE) Kathy Moore 250-748-6416 kathy@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER (VAN. ISLE) Kathy Moore 250-748-6416 kathy@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER Meena Mann 604-559-9052 meena@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER Meena Mann 604-559-9052 meena@pacificyachting.com

PUBLISHER / PRESIDENT Mark Yelic

MARKETING MANAGER Desiree Miller

PUBLISHER / PRESIDENT Mark Yelic

GROUP CONTROLLER Anthea Williams

ACCOUNTING Elizabeth Williams

ACCOUNTING

CONSUMER MARKETING Craig Sweetman CIRCULATION & CUSTOMER SERVICE

Roxanne Davies, Lauren Novak, Marissa Miller DIGITAL CONTENT COORDINATOR Mark Lapiy

SUBSCRIPTION HOTLINE 1-800-663-7611

SUBSCRIPTION

SUBSCRIBER ENQUIRIES: subscriptions@opmediagroup.ca SUBSCRIPTION RATES One year Canadian and United States: $48.00 (Prices vary by province). International: $58.00 per year.

SUBSCRIBER ENQUIRIES: subscriptions@opmediagroup.ca

Editorial submissions: Submissions may be

Send your letter, along with your full name, and your boat’s name (if applicable), to editor@pacificyachting.com. Note that letters are selected and edited for brevity and clarity.

My name is Leo Owen Kaake Utzinger. I am 10 years old, and I am sending this through my mom’s email account. Here is my letter to the editor: The last time somebody wrote a letter of my age was back in the first Pacific Yachting catalog. I am 10. Anyway, this letter is about my love for boats. I first started to love boats when I went on my friend’s sailboat when I was five. It all blew up from there. When

I was eight, I got 25 tours of strangers’ boats on Cortez Island. That is when I found out about my grandparents’ boat. I wanted to take it over to our house ever since. My grandparents are happy that somebody wants the boat again, but I am a bit young to drive it over to our house. I live in the Comox Valley and it is all the way in Vancouver. I am trying to save up my money to fix whatever is on this boat that needs to be fixed. It has not moved in

30 years and the tongue of the trailer is sticking out of the doors. My papa had to cut a hole in the wooden doors for the tongue to stick out. I have wanted that boat for so long. It was my favourite boat ever. Until I saw this sailboat. It is a 1983 Storebro Royal. It is a 33-foot boat, and it has one head, two cabins and a galley. I Just hope nobody buys it before I do. I am trying to collect all Pacific Yachting catalogs, and I am really enjoying them so far. I really love James Barber, and I hope he never Stops writing his recipes.

—Leo Utzinger

For a person whose “life on the water” has been limited to rafting on a neighbour’s pond up north in my youth and BC Ferries now, PY takes me to places I never knew existed, nor will otherwise ever see.

Each month PY offers new and/or nostalgic experiences and October’s issue (just received) did not disappoint as my lifelong passion for cemetery exploring was enhanced by Cherie Thiessen’s article, “The Haunted Cruise” featuring six cemeteries in the Salish Sea.

Thank you Cherie Thiessen! Thank you Pacific Yachting! Keep up your good work.

—Mary Daniel

EVEN IN THE OFF SEASON, DON’T LEAVE YOUR BOAT AT THE DOCK WITHOUT THE BEST INSURANCE COVERAGE AVAILABLE!

REQUEST A QUOTE

REQUEST A NAVIS YACHT POLICY QUOTE FOR YOUR MOST VALUED ASSET.

11/2024

This is a local news-driven section. If something catches your attention that would be of interest to local boaters, send it along to editor@pacificyachting.com.

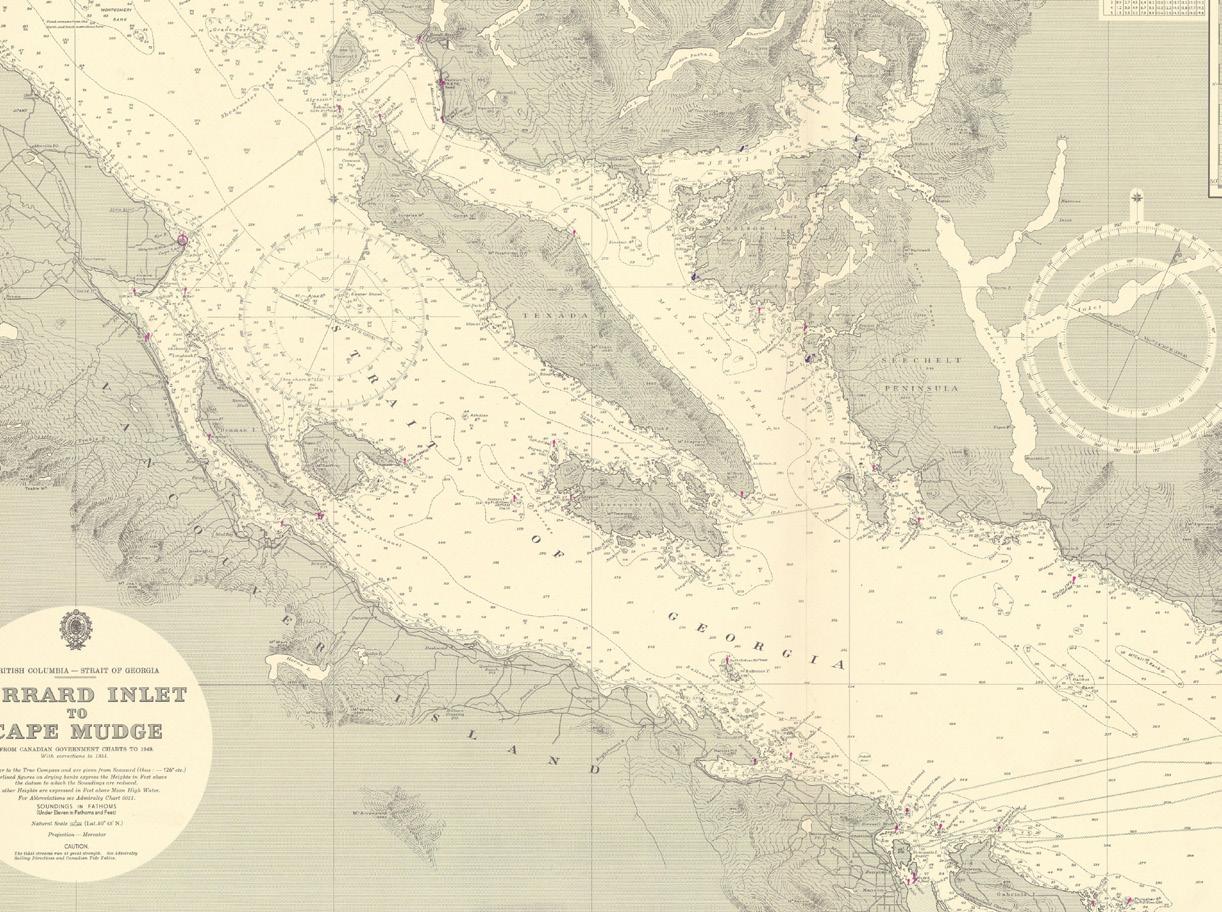

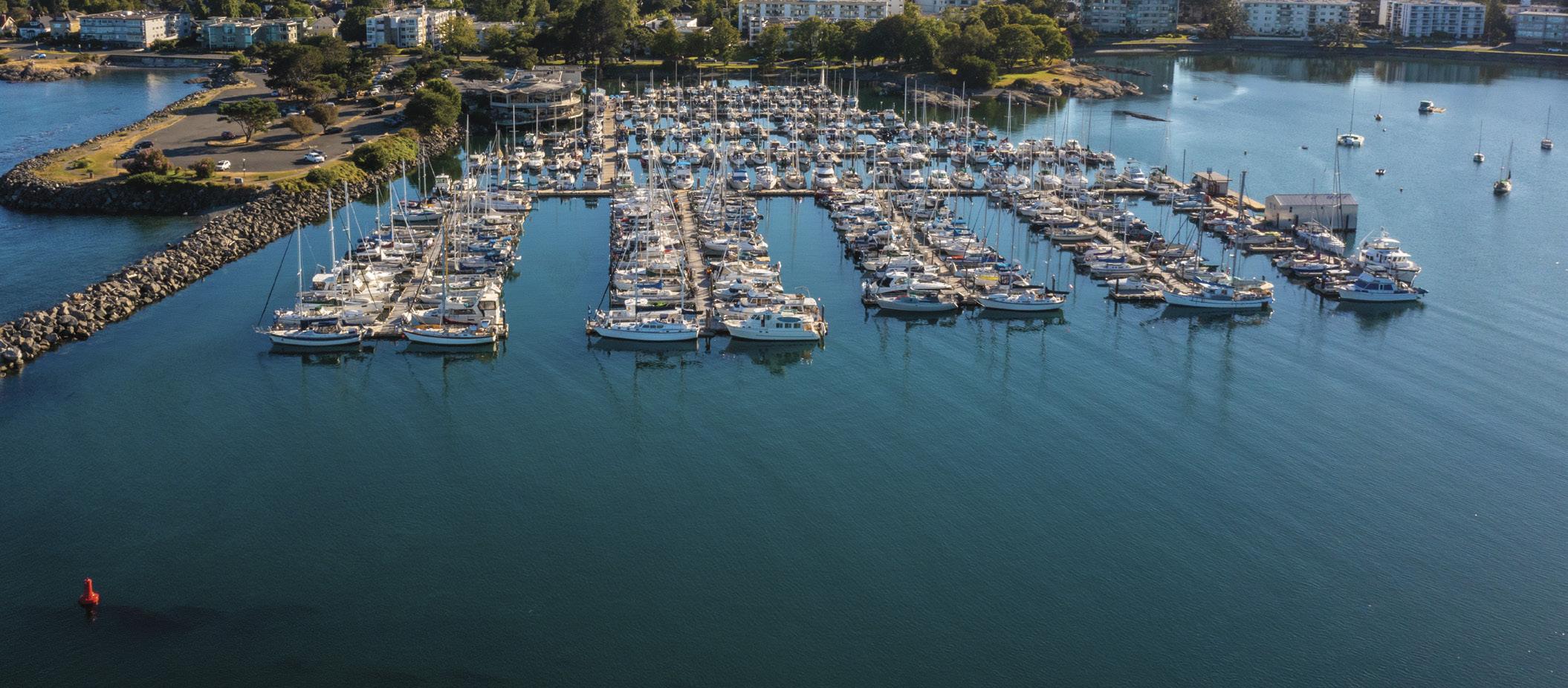

Do you know where this is?

Congratulations to brothers Harry and Theo MacDonald for correctly guessing October’s location as Telegraph Harbour Marina on Thetis Island! Good luck to this month’s guessers.

Deadline: Friday, November 8.

By Nicholas Coghlan, Seaworthy Publications, Melbourne Florida 2024

You can travel to Japan, a journey of approximately 4,300 miles from Vancouver to Tokyo by cruise ships that offer curated expeditions and adventures. But if you have the energy, the personality and the skill, you could sail to Japan instead. The latter promises a bounty of unforgettable adventures. Of the 14,000 islands in Japan, only 260 are inhabited and the ideal way to visit is by boat.

Author Nicholas Coghlan is a career diplomat and skilled blue water sailor. He and his wife, Jenny, have sailed some 70,000 miles offshore. This adventure narrative recounts their 15-month cruise on Bosun Bird, their beloved Vancouver 27. They discovered that the Japanese offshore sailing community is very small, mainly open to the wealthy.

Coghlan is a skilled writer and storyteller who captures the excitement and drama of the land of myths and legends, castles and temples, geishas and sumo wrestlers. For many years Japan was a closed insular society. Coghlan’s professional temperament and Jenny’s

kindness and curiosity helped them navigate the country’s puzzling bureaucracy and social and cultural differences. The Canadians arrived a few weeks after the Fukushima catastrophe and they discovered not an outpouring of grief, just stoical acceptance. Steeped in his soldier-father’s negative opinion of Japan, Coghlan also had candid and surprising conversations around culture and history, especially Japan’s role in the Second World War. Sailing in Japan is not for the faint of heart. Let’s list a few challenges: typhoons, busy shipping lanes, lots of nets and fish farms, and complicated mooring locations. Coghlan’s book addresses all of these challenges and many more.

Like some of the best travelogues, this book can be enjoyed by the armchair traveler who appreciates intriguing stories about Japan, but it’s also perfect for the serious sailor who needs comprehensive cruising notes and tips and lessons on cruising in Japan. So, if you are thinking of sailing to Japan, this book is for you. orders@seaworthy.com

—R.M. Davies

Pacific Yachting’s annual photo contest is back! So get behind the lens while you still can, and start submitting your best boating photos from 2024 for a chance to be featured in Pacific Yachting. Prizes include gear from Mustang and Salus Marine! For contest rules and to enter, visit pacificyachting.com/photo-contest

Deadline: December 15

Calibre Yacht Sales has Announced New Ownership

Calibre Yacht Sales has announced that Nick Scruton has taken over as Owner and CEO as of September 15, 2024.

Founded in 2008 by Richard and Svetlana Evans, Calibre Yachts places values and ethics at the forefront of the business. Richard believes that trust and integrity are integral to securing the best value for his clients. Indeed, Calibre’s motto since day one has been “Trust, Integrity, Lifestyle”.

Starting in Vancouver with a team of two, Richard’s steadfast approach allowed Calibre to grow and prosper into one of the largest brokerage firms in BC. Today, Calibre has 10 brokers and four locations, covering Vancouver and Vancouver Island. Additionally, Calibre enjoys a leadership online position, with its YouTube channel earning over 11 million views and more than 27,000 subscribers. While Richard remains steadfast in his love of all things boating, the time has come to pass along his passion and the culture that epitomizes Calibre.

“We are very happy to have Nick and Iris taking over the company, knowing they will sustain our values and commitment to working hard for clients,” says Richard. Nick has an impressive background in successful national and international business management. Origi-

nally from Vancouver Island, he has traveled extensively abroad and spent several years overseas, most notably in Taiwan, where he met his wife, Iris. Iris and Nick have two young boys, both active sportsmen like their father, and Nick’s parents are also heavily engaged in the marine community. Nick is bringing fresh energy and investment to Calibre’s services and infrastructure, and, for Calibre clients and vendors, it will be business as usual. Richard will continue to lend his expertise and counsel to Calibre and, while stepping down from the rigours of ownership, will continue as a Senior Broker with Calibre for the next few years. For more information go to calibreyachts.com.

River City Marine, an authorized Grady-White dealer, has recently expanded its territory to cover all of British Columbia, including Vancouver Island.

River City Marine is well-positioned to take care of their Grady-White customers in Vancouver and Vancouver Island. As a premier marine dealership, they offer knowledgeable staff across Sales, Financing, Service, and Parts Departments.

You can visit River City Marine at their centrally located facility in Abbotsford. Additionally, mark your calendar for the upcoming Vancouver International Boat Show scheduled from January 29 to February 2, 2025.

Together, Grady-White and River City Marine are committed to providing you with the ultimate boating experience. River City Marine shares a passion for boating and understands that a boater’s priority is getting out on the water! They is excited about the opportunity to enhance your enjoyment as a proud Grady-White owner.

ANCHOR MARINE

Victoria, BC 250-386-8375

COMAR ELECTRIC SERVICES LTD

Port Coquitlam, BC 604-941-7646

ELMAR MARINE ELECTRONICS

North Vancouver, BC 604-986-5582

GLOBAL MARINE EQUIPMENT

Richmond, BC 604-718-2722

MACKAY MARINE

Burnaby, BC 604-435-1455

OCEAN PACIFIC MARINE SUPPLY

Campbell River, BC 250-286-1011

PRIME YACHT SYSTEMS INC

Victoria, BC 250-896-2971

RADIO HOLLAND

Vancouver, BC 604-293-2900

REEDEL MARINE SERVICES

Parksville, BC 250-248-2555

ROTON INDUSTRIES

Vancouver, BC 604-688-2325

SEACOAST MARINE ELECTRONICS LTD Vancouver, BC 604-323-0623

STRYKER ELECTRONICS

Port Hardy, BC 250-949-8022

WESTERN MARINE CO Vancouver, BC 604-253-3322

ZULU ELECTRIC Richmond, BC 604-285-5466

You’re looking at it! Furuno’s award-winning Radar gives you clarity & target separation like no one else. Don’t take our word for it. See for yourself. Scan here, and we’ll show you!

Canada was back at the 2024 America’s Cup for the first time since 1987. The Canadian Team, Concord Pacific Racing, competed with distinction at the Youth and Women’s America’s Cups in Barcelona. With this foundation laid, what comes next?

“The future of competitive sailing is foiling,” believes Stephanie Bacon, past Commodore of Royal Victoria Yacht Club and Canadian team board member. With the Nacra 17 confirmed for the 2028 Olympics and inexpensive and accessible wing foiling under consideration for 2032, she has good reason to think this. Canada’s Youth AC Captain, Andrew Wood, notes that foiling sailing is exciting to watch and “not as different to conventional sailing as people think.” He believes

learning to foil could soon be a followon to entry level learn-to-sail courses. The key is access to boats, says the Canadian team’s leader, Isabella Bertold, who knows the problem first-hand. For budget reasons, the future world champion chartered, rather than owned, a Laser for her first three years of competition. “Be inclusive, not exclusive” she says, “and don’t stream people irrevocably into one class at an early age. The broader your experience the better you are.” Unlike Canada, she notes, most top sailing countries have young sailors who are exposed to many forms of the sport.

With new foiling dinghies like Wasps and Moths costing $20,000 and more, sailing clubs need to be the access points. While some may be deterred by the maintenance needs of more com-

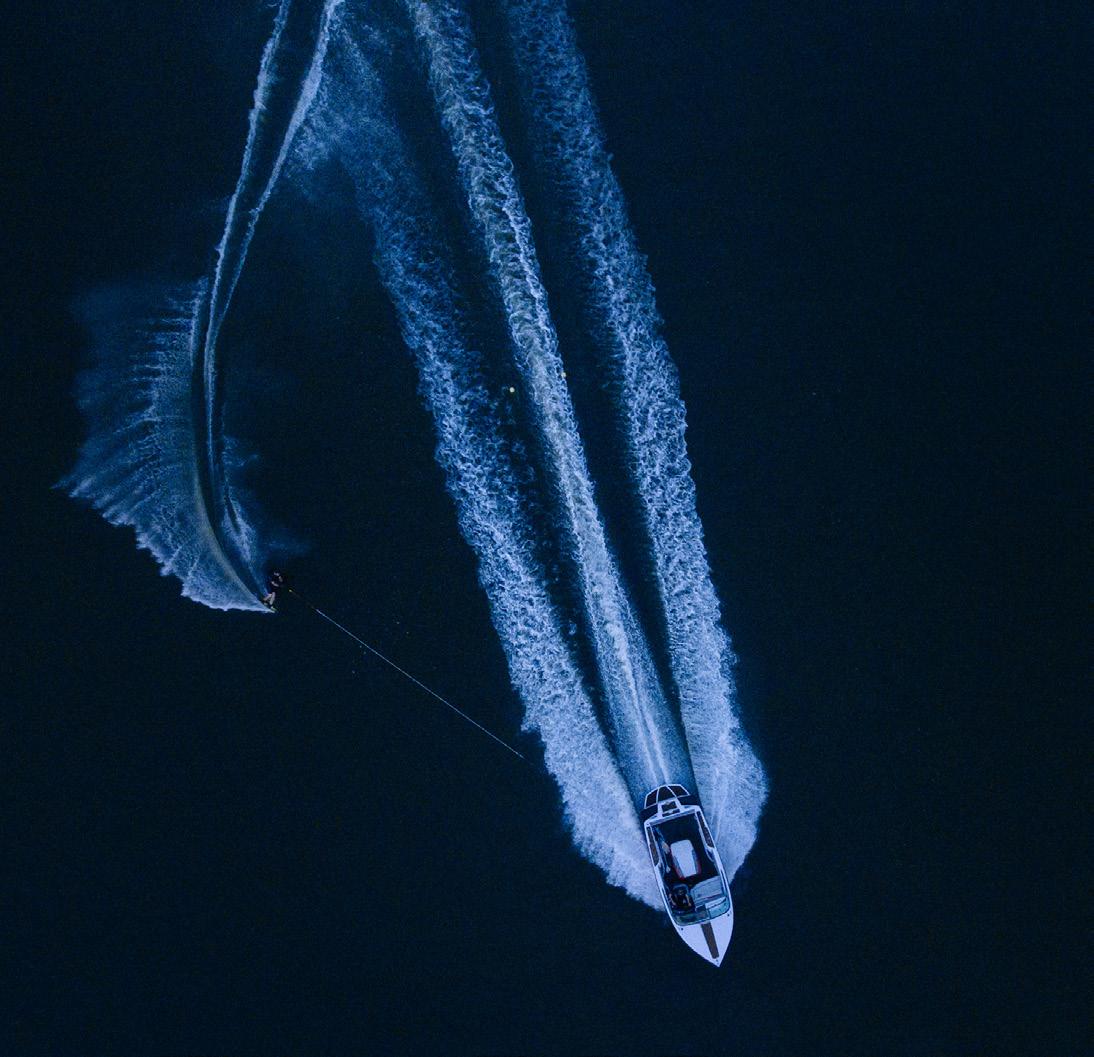

plex foiling boats, Bertold sees a winwin solution in engaging and training the learners in the maintenance as well as operation of the boats. “If it’s a nowind day, it’s a good day to work on the boats,” she says. Wood agrees: “It’s vital, including in pro sailing. It’s a team skill to be able to do whatever needs to be done.” And wing foiling may be the ultimate in accessibility. Not only it is inexpensive, on no-wind days, the apprentice foilers can be towed behind a powerboat.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, boats like the AC40 offer the possibility of differently-abled athletes to compete on even terms at the highest levels of the sport, says Bertold, who foresees para-sailors participating in future America’s Cup campaigns.

—John Thomson

Using a boat ramp can be a daunting task, especially at busy ports of entry where others are waiting and watching. CanBoat offers some useful techniques to make sure your boat launch goes smoothly. For starters, help ease the process by having these things in order before getting to the ramp or while waiting in line:

• Have everything you need ready to go from your vehicle.

• Check and secure the drainage plug.

• Remove all straps and safety chains.

• Unplug the trailer wiring harness.

• Check the bilge for gas vapour and turn on the blower if necessary.

• Give the gas hose a squeeze.

• Check drive belts for correct tension.

• Check oil.

It’s also recommended to make sure your dock lines are well secured to the bow and stern to tie on to either end of the dock. It’s also helpful to have someone with you to hold the lines and tie off the boat once you’ve backed it in to the water. As the driver returns the vehicle, anyone left with the boat should get the boat warmed up and ready to leave swiftly, as this is a ramp not a slip and it’s important to get moving as quickly as possible.

Some other tips while launching your boat include:

• Have your windows rolled down so you can hear the docking crew’s instructions.

• Leave your bow pennant and stern flag poles stored aboard while launching and recovering the boat as they tend to get in the way.

• A spare set of identified keys will be helpful if a crew member parks your vehicle after launching.

If you’re willing to help someone who is launching or retrieving their boat, make sure you follow their instructions, and get approval before touching or using their boat or gear to avoid any unnecessary conflicts.

—Courtesy CanBoat

Like many British Columbians, I have an old picture of a Martin Mars water bomber in my photo album. It was taken while we were camping at Sproat Lake Provincial Park. The quiet had just been shattered by the thunderous roar of aircraft engines, and my husband and I rushed our preschool daughter to the lake’s edge to see the enormous Martin Mars bomber gliding across the serene water. My own parents had taken my sisters and me to see these same planes. I still recall the thrill of hearing them rumble to life and gasping in awe as they skimmed the lake’s surface, scooping up thousands of litres of water before flying off to fight fires. Before that, my grandfather had taken my mum and her siblings to see the mighty planes—

Peter Chance.

my mum still talks about how exciting it was to go on board.

Christened the Martin Mars after the Roman god of war, the plane was originally designed as a long-range bomber but quickly proved more valuable for its transport capabilities. Impressed with the huge seaplane’s ability to fly to Europe and back on a single tank of gas, the US Navy ordered 20 of the craft. They took possession of the Hawaii Mars on July 21, 1945, but less than two weeks later it crashed during the test flight on Chesapeake Bay. The US Navy used the event to reduce its order from 20 planes to 11 and then to five. Over the next year, the Philippine Mars, Hawaii II Mars, Marianas Mars, Marshall Mars, and Caroline Mars were launched.

By 1959, their role was done, and the US Navy sold the four remaining Martin Mars flying boats for scrap.

At this same time, a group of BC lumber companies (MacMillan Bloedel, TimberWest, and Pacific Forest Products) were grappling with how to manage forest fires. Joining forces, they formed Forest Industries Flying Tankers (FIFT) and found the four Martin Mars when they were searching for large flying boats to turn into water bombers. They bought the four aircraft for $25,000 each, and with a stroke of foresight, they also bought every spare part they could find.

The Marianas Mars was the first of the four to be adapted for firefighting. In May 1960, onlookers in Sidney watched as the newly outfitted Mari-

anas flew across the ocean at 120 kilometres per hour, scooped up 27,000 litres of water and dumped it in front of the crowd—demonstrating the capacity to fight fires like never before. Sadly, two of the four aircraft were soon lost: the Marianas in a crash in 1961, taking the lives of all four crew members, and the Caroline Mars was damaged beyond repair during a 1962 storm. Despite the rough start, FIFT pushed on, and the Philippine and Hawaii II were soon cloaked in their distinctive red and white livery and sent into action from their new base at Sproat Lake.

With the forestry industry changing, the Coulson Group acquired the planes in 2007. But the Martin Mars were aging, and those spare parts were beginning to run out. Firefighting tactics had also shifted; the focus became less on dousing a fire completely and instead aimed to contain them and keep them away from structures. The forest was left to burn as it would naturally. When the bombers were needed, the Mars’ incredible size also restricted their operational range; BC doesn’t have enough large lakes in the right places. The province ended its Martin Mars contract with Coulson in 2013.

The final flight of Hawaii Mars was over a year in the making. To get from Sproat Lake to Sidney and the museum, Coulson Aviation enlisted five former maintenance engineers and four flight

crew to complete about 10,000 hours of aircraft preparation and flight retraining over six months.

Wayne Coulson, CEO of the Coulson Group of companies, said in a statement he was pleased to partner with the BC Aviation Museum in the “important endeavour” of preserving the plane. “The Hawaii Martin Mars water bomber is an amazing aircraft,” Coulson said. “You will probably never see one fly again.”

Now, as the Hawaii Mars begins its new chapter at the museum, I can’t help but recall the distinctive sound of her engines as she rumbled overhead, and the relief in knowing she’d come to help. The nostalgia feels bigger than a memory of watching a giant plane scoop up water and take flight—and different than an appreciation for innovation or engineering. It’s more like that sense of affection and connection that we hold for an old sailing ship; the kind we know can weather storms and keep us safe at sea. It’s comforting to know that future generations will have the chance to create their own memories and marvel at this remarkable aircraft, just as we did.

—Diane Selkirk

The Hawaii Mars Exhibit officially opened in September. Visitors to the BC Aviation Museum at 1910 Norseman Rd, North Saanich will be able explore inside the aircraft and even climb four stories above ground to sit in the pilot’s seat.

V10 Verado outboards shift your expectations performance feels like. They come to power, propelling you forward to sensational smooth, quiet and refined, they deliver only Verado outboards can provide.

expectations of what high-horsepower to life with impressively responsive sensational top speeds. Exceptionally deliver an unrivaled driving experience exploring. So are you. Go Boldly.

V10 Verado outboards shift your expectations of what high-horsepower performance feels like. They come to life with impressively responsive power, propelling you forward to sensational top speeds. Exceptionally smooth, quiet and refined, they deliver an unrivaled driving experience only Verado outboards can provide.

Mercury engines are made for exploring. So are you. Go Boldly.

GALLEY

The ultimate comfort food

BY JAMES BARBER

TThe main ingredient for this comfort food is time—time for the long, slow cooking that turns meat into wonderfully scented layers of flavour. If you

have a Dickinson oil stove, that’s no problem—the pot goes on after breakfast and cooks all day until supper. But if you don’t want the propane going all day with a headwind and a quartering sea, the best solution is to make supper at home, before your weekend. Make a big stew, enough for eight or 10 people, and when it’s cooked, freeze it in twopeople portions in resealable bags. Come Friday, put a bag or two in your boat’s icebox (they should keep for up to two days), take them out at lunch-

time and let them defrost in the sink. When the anchor is down, you can have supper (and a warm, wonderfulsmelling boat) in less than 30 minutes.

Beef is the best meat for frozen stew. So let’s put 30 minutes into making it and getting it on the stove, two hours for relaxing while it cooks and 15 minutes to get it into bags. That’s four suppers for two. You’ll need a big pot with a lid.

•4 lbs (2 kg) stewing beef, cubed

•3 tbsp flour mixed with 1/2 tsp pepper and 1 tsp salt

•2 big brown onions, coarsely chopped

•2 cloves garlic, coarsely chopped

•1 bottle red wine

•3 tbsp olive oil

•1 bay leaf

•1 tsp thyme

•Salt & pepper

1. Put flour and seasonings in a plastic bag, add half the beef cubes, toss well and take out the beef, shaking off excess flour. Add the remaining beef and toss well again.

2. Heat the pot over medium heat, add the oil and fry as many of the beef cubes as will possibly go on the bottom of the pan without crowding. Cook two or three minutes until light brown, then turn them over. Cook all sides, take them out and cook the rest. This careful browning is the beginning of developing flavour.

3. Fry onions in the pot, still over medium heat (you may need a little more oil). After two minutes, add the garlic and fry another two minutes, scraping any brown bits of meat from the bottom of the pan for more flavour (adding a glug of wine will help too).

4. Then put the beef back in, add the rest of the wine, the bay leaf (I add bits of orange peel and so should you if you’ve got some), along with the thyme, pepper and salt.

5. Bring to a boil, turn heat as low as it will go and simmer for two hours. Go away, read, take a long bath, sit in a corner and worry about why you worry so much, and just occasionally breathe in through your nose and say, “Stew... stew...”

6. Turn off the heat and let it cool 30 minutes, then put it into four resealable bags, label and freeze.

7. Anytime you want a stew, defrost one bag a bit and put it in a saucepan with a bit more red wine and slowly bring to a boil.

8. Add chunks of potato or carrot if you want a big meal, and in 30 minutes it will be ready. Any leftovers make great soup for the next day—just add a bit of water or wine and some torn-up bread.

•1 can sockeye salmon, tuna or packet of fish filets

•1 onion

•2 tomatoes

•1 clove garlic

•1 head of lettuce

•1/2 cup water

•1 soup cube

•2 tbsp olive oil

•2 oz sherry

•1/2 tsp salt

•1/2 tsp pepper

•1/2 tsp chili flakes or favourite hot sauce

1. On one of those cold winter days, try this 20-minute fisherman’s stew that doesn’t pretend to be a bouillabaisse or a matelote.

2. Chop an onion coarsely and fry it two minutes in two tablespoons olive oil. Add one clove garlic, chopped; a half teaspoon of black pepper; a half teaspoon of salt; a half teaspoon of chili flakes (or hot sauce); and two tomatoes, chopped.

3. Stir it all together for two minutes while you cut a head of lettuce crosswise into halfinch slices.

4. Now add a half cup of water and a soup cube if you have it, cook two minutes and add either a can of sockeye or a can of tuna (or a packet of frozen fish fillets that have thawed a bit while you’re doing everything else).

5. Add two ounces of sherry, cover, cook for four minutes, take off heat, stir once, serve immediately and modestly take bows.

COLUMN GUNKHOLE

MARY ANNE HAJER

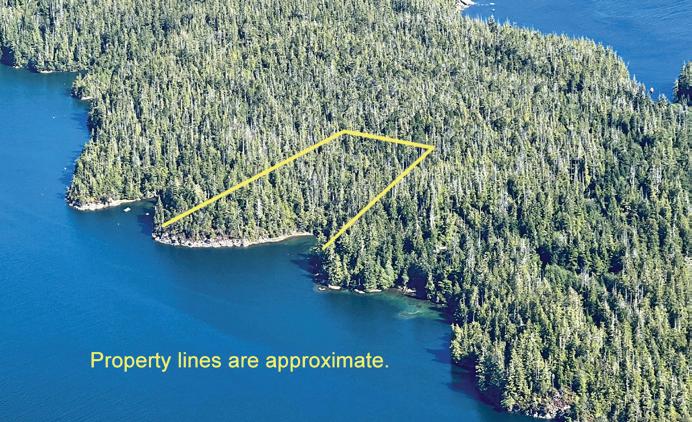

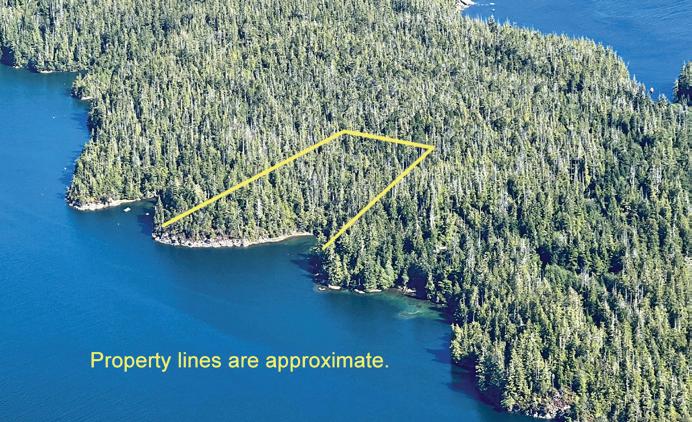

WWhen Frank and I lived in Richmond and our boat was berthed at River Rock Marina, our shake-down cruise each spring was always to Gambier Island in Howe Sound. Gambier is only about 17 miles as the crow flies

from Vancouver, but it is a different world. It has no stores, pubs or hotels, not even a car-ferry connection to the mainland. With a year-round population of about 125 residents (600 in summer), Gambier is the perfect destination for boaters who want to escape the concrete, crowds and bustle of urban life—for a few days anyways. And because of its proximity to the city of Vancouver, it’s the perfect offseason destination for many boaters.

For us, the trip took approximately four hours in our slow boat, which meant despite leaving early, we would

arrive in the afternoon. We always spent the first night at anchor in roomy East Bay, but often on the next day we would head for Centre Bay in hopes of finding our favourite nook empty. It usually was, which meant we could settle in for several days and nights of blissful solitude and peace on the water.

The entrance to the nook, named Sunset Cove by the Yeadon-Joneses in their Dreamspeaker Guide for the area, is located between two concrete pillars a short distance north of Mackenzie Cove on the east side of the

bay. The bottom slopes steeply downwards, so we have to anchor closer to land than we would normally like, but a stern line tied to a tree keeps us in position. A low tide exposes a jumble of boulders so close to our boat that it seems possible to step onto them from our swim grid. It also reveals a wide rocky ledge that is invisible at high water. This cove is sheltered from all winds but is only roomy enough for one boat.

When we want to stretch our legs, we can scramble over the shoreline rocks to a footpath along the water that heads north to an outpost of the West Vancouver Yacht Club and south to Mackenzie Bluff.

On one visit we followed an old logging road inland up a steep hill. At the top we found a meadow where three deer were grazing. It was a peaceful, bucolic setting, and the only sounds were those of nature—bird song and wind whispering in the trees. A short distance further along we came upon a man-made pond that a wooden sign identified as Koi Lake. I’m not sure if there were any koi left in the pond, because we saw heron in the vicinity and a soaring eagle reflected in the lake’s still waters. A wide swath of yellow flag irises swept the shoreline and water lilies dotted the pond’s surface. Then in a nearby tree we spotted the red crest of a pileated woodpecker, a rare treat. For 20 minutes we sat on a nearby wooden bench and absorbed the serenity of this idyllic spot.

On another visit to the nook, we had an experience that was the opposite of serene. In the middle of the night we were jolted out of sleep by frighteningly loud grunts and groans, bellows and growls. We scrambled out of bed, still groggy from being wakened so abruptly, and clutched each other in the darkness. The sounds seemed so close! What could they be? For a few panicky seconds we thought of those drawings of monsters that appeared on medieval maps along with the

words “here be dragons!” warning of danger in the far reaches of the sea. But then the brain fog cleared away and we recognized the unearthly sounds for what they were—the howls of seals! The falling tide must have exposed the rocky ledge next to the boat and the seals had hauled themselves out for a rest. Relieved, and feeling a little foolish at our fancies, we went back to bed. In the morning the tide had risen, and there was no sign of either the ledge or the seals. But we have never forgotten our brush with sea monsters.

Centre Bay is home to outstations for both the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club and the West Vancouver Yacht Club as well as the Centre Bay Yacht Station, which lies at the head of the bay. All of these docks are private but there is good holding along the eastern shore of the bay in both Sunset Cove and Mackenzie Cove. An islet separates the two coves and anchorage can be taken in its lee along a steep

wall between the two coves. There is alternative anchorage in good holding in approximately five metres in the small cove at the southwestern corner of the bay, though stern tying isn’t an option here because of the private docks.

Marina: Union Steamship Marina, Snug Cove unionsteamshipmarina.com

THE R-43 CB THE CUTWATER FLEET INCLUDES THE FOLLOWING MODELS: C-248C, C-288C, C30S, C-30CB, C-32 & C-32CB

THE RANGER TUGS FLEET INCLUDES THE FOLLOWING MODELS: R-23, R-25, R-27, R-29 S, R-29 CB, R-31S, R-31 CB, R-43S & R-43CB

Exploring these magical islands aboard a 138-foot catamaran

BY HANS TAMMEMAGI

OOff the wild coast of northern British Columbia is an archipelago of more than 150 mist-enshrouded islands called Haida Gwaii, a mystical place of legends, spirits and supernatural creatures. I arrive, knowing little about the culture of the Haida or the ecology of the islands.

THE FIRST DAY of our tour is by van; then we will spend six days aboard a large and comfortable catamaran, the MV Cascadia. We start in Old Massett on Graham Island, a town where the Haida Nation regrouped in the late 1800s, having been forced to abandon most of their ancient villages due to small pox and colonization. The population plummeted by about 95 percent. We pass an Anglican church whose spire incongruously shares the sky with a nearby monumental carved pole. Today, there are about 50 poles punctuating the Masset area, with most raised in the past two decades. Jessica, one of our guides, told us, “I’m very proud to be a Haida. Our people are making an amazing comeback. Our strength and resilience are due, in part, to being a matriarchal society.” I’m already starting to get an insight into Haida culture and history.

We drive to the north end of Graham Island where a fleeting mist partially obscures the top of Taaw Tldáaw or Tow Hill, and gather around the 56-foot Solstice Pole at Hl’yaalan (Hiellen). On Indigenous Day, 2017, the pride of the

Right

Haida shone forth with dancing and singing when this pole, the highest on Haida Gwaii, was raised. Next morning, we drive south to the Haida Heritage Centre in Skidegate, which opened in 2008 in an emotional celebration of dances and song with hundreds of Haida wearing button blankets, cedar hats, ceremonial masks and traditional regalia. The Centre, which includes a Performance House, Carving Shed and the Saahlinda Naay Haida Gwaii Museum, faces the ocean and looks like a traditional village. Nikkayla, a young Haida guide, explains the six tall poles full of mythological creatures in front of the Centre. “Being Haida brings pride for we are talented artists and have strong values. Wealth is measured by how much you give away, usually via potlatches, not by how much you accumulate.” I wander among colourful displays in the museum, then sit quietly before three towering totems more than a century old. I wonder about the stories and ghosts they contain. I also wonder about potlatches and “wealth.”

Below

A TENDER SHUTTLES us to the 138-foot, 500ton, Cascadia, which has anchored nearby, and will carry us southward for the next six days. My room is well appointed with a king bed, shower, toilet, desk and large windows looking onto the ocean. Twenty guests are housed in 12 cabins. Captain Jeff guides the catamaran to anchorage on the east edge of Moresby Island. I meet the other guests, all friendly and fascinating, and together we explore the spacious lounge, which has sofa seating, a library and a bar. Deck areas have tables, and the captain’s bridge, where I spend a lot of time, is roomy and loaded with communication and navigation systems.

For dinner, we sit at two long tables decorated with wildflowers and sip an excellent sauvignon blanc while listening to Chef Collin, who promises he will “take us places.” Faithful to his word, he serves marinated sockeye salmon with asparagus, saffron risotto and onion marmalade. Yummy!

IN THE MORNING, we tour Cumshewa village, led by Dee Dee Crosby, our Indigenous interpreter. Her Haida name, Gidin Jaad, means Eagle

Woman. She is of slight build, and a prominent tattoo on her chin shows a raven and an eagle, the two clans of the Haida Nation, back-to-back. “The tat too represents oneness,” she says. “The world needs to be unified.”

She leads us to the vestigial remains of an abandoned and decaying village that once housed 490 people in 19 houses. Moss-covered poles lie on the ground.

Back on Cascadia, we motor south, slowing at Reef Island, which is covered by many dozens of sea lions. They jostle and snort, practically one on top of the other.

The

At Hlk’yah Gaw Ga (Windy Bay), we stand before the Legacy Pole, a tribute to the protesters who halted logging on Athlii Gwaii (Lyell Island), which led to the creation of Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site. The Park, only accessible by boat or floatplane, is protected by Haida Watchmen, who welcome visitors, control access and help preserve the archaeology

at five sites. Instead of being logged, in 1985 Gwaii Haanas became the worldrenowned Haida Heritage Site, then in 1993 a National Park Reserve.

A path leads us through thick ferns into a dark rainforest with moss hanging from branches. I think I glimpse spirits moving in the forest and understand why the Haida believe in supernatural creatures. Approaching an immense old-growth cedar, we are silent, thinking of the countless generations this tree has witnessed. “In our culture, trees like this are revered and respected, not razed in clear cuts,” Dee Dee says quietly.

Back on board, we follow Raj, the chief engineer, into the engine room. Proudly, he describes the shining two 450-horsepower Cummings diesel engines and their fuel-efficiency. Cascadia was purchased from New Zealand, and began service for Maple Leaf Adventures in 2019. When the pandemic halted tourism, Cascadia turned to the

removal of debris, mostly plastics, from the BC coast.

Our next stop is Gandll K’in Gwaay. yaay (Hotspring Island), where we hike to one of the most unique sites in Gwaii Haanas. Three pools are formed from springs at temperatures from 32° to 77° Celsius (89° to 170°F). Under a bright sun, we laze in the thermal pools with a grand view over the ocean, our muscles relaxing in the warmth.

OUR JOURNEY ABOARD continues. “Whales!” Everyone rushes to the deck, binoculars at the ready. We love watching the dorsal fins of orcas rising and falling among the waves. That evening, Scotty, one of the crew, looking at my photos, says, “See the marks on the dorsal fin. That’s T124D and her calf.”

At SGang Gwaay Island, Grace, a friendly and talkative Watchman,

leads us through a verdant forest to the abandoned village of SGang Gwaay Llnagaay, where remnants of longhouses and carved poles still stand as a testament to the powerful artistry and culture of Haida society. Incredibly beautiful and dating from the late 1800s, this is the largest collection of North American monument poles still in their original location, and has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Near Flatrock Island, we see a rare horned puffin racing along the water, working to get its cumbersome body into the air. An eagle perches high in a tree, watching. Two humpback whales parallel the catamaran as we cruise by, their wooshes echoing across the water. One of them, probably a teenager, shows off by breaching repeatedly. Little wonder Haida Gwaii is nicknamed the “Galapagos of the North,” for it is an otherworldly realm, a place to connect with raw nature.

At T’aanu Island, I bow before the modest tombstone of Bill Reid, who is internationally renowned for his jewellery, poles and carvings like the Jade Canoe at YVR. Reid brought back the lost art of canoe-making by building Loo Taas (Wave Eater), an elegant, beautifully painted, 50-foot canoe. Fittingly, Loo Taas carried Reid’s ashes to this quiet resting spot.

At K’uuna Llnagaay (Skedans) on Louise Island, we see the pit and fallen moss-covered posts of Dee Dee’s former home. It is a stark contrast to the 1878 photo in the Haida Gwaii Museum showing 56 mighty poles reaching skyward in a vibrant village.

AS THE CRUISE ends, I am happy. The journey has shown that the Haida are preserving the past, while building a strong future. They are a resilient and strong people.

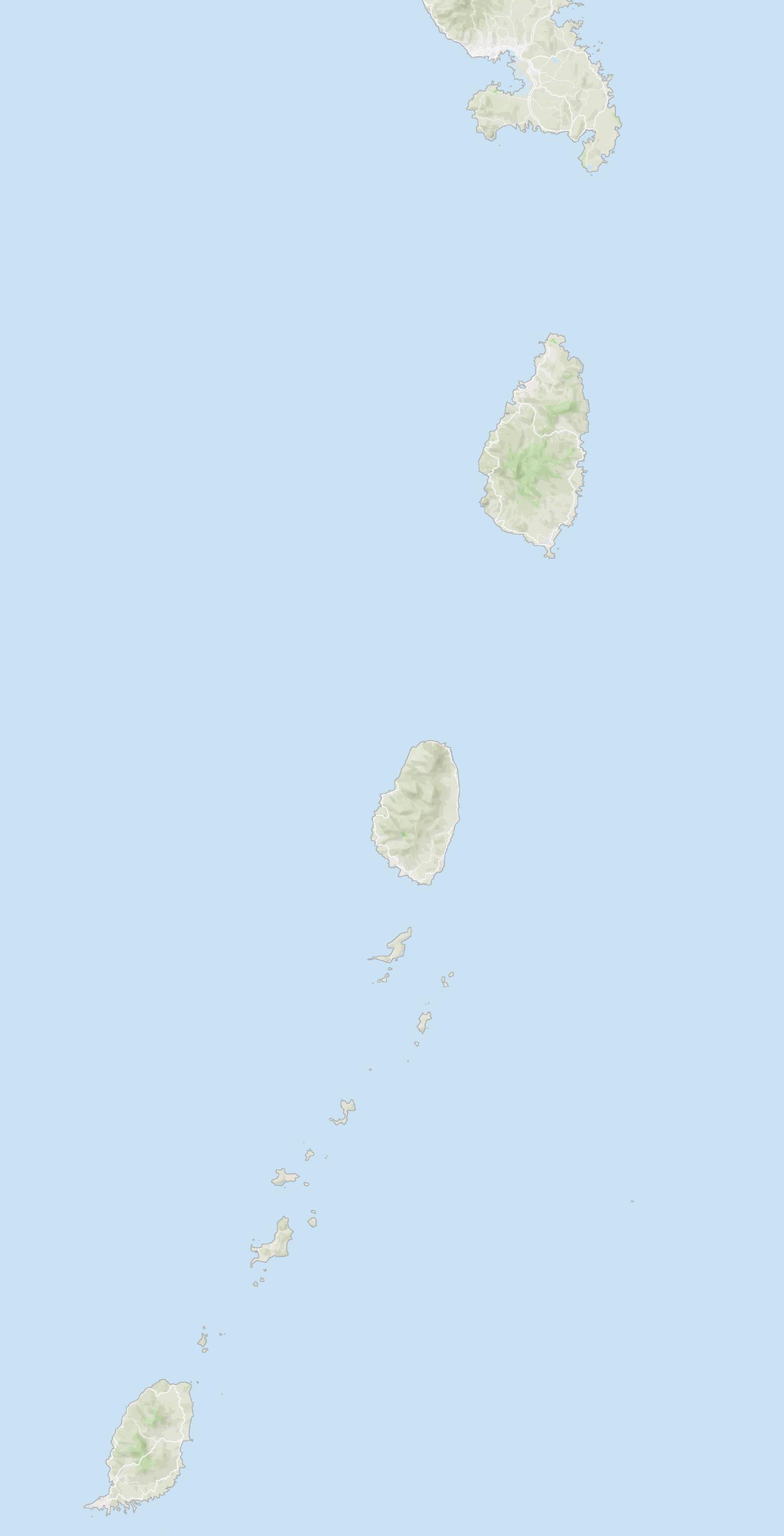

Two weeks in the Windward Islands—Saint Lucia to Saint George’s

AAfter getting married in 1978, Pam and I bought a Crown 18 and sailed from West Vancouver to the Gulf Islands for a week. Over the years, we’ve sailed in different boats from Tacoma, Washington to the top of Vancouver Island. In 2020, when our good friends Janet and Paul from Squamish invited us to sail in the Caribbean for two weeks we jumped at the opportunity. We would start in Rodney Bay, Saint Lucia and sail south to Saint George’s on Grenada.

We were at an Airbnb for a couple of days before boarding our sailboat and part of that time was spent shopping for the provisions and touring around Rodney Bay.

Francis, a well-known local sailor in Rodney Bay, joined us in the cockpit of Turis, the Beneteau Oceanis 41 Paul had chartered. Francis sat with us for a couple of hours to orient us to cruising the islands from Saint Lucia to Grenada,

Paul had a float plan that included Soufriere, Bequai, the Tobago Cays, Union Island and Carriacou, finishing in Saint George’s. When Francis heard we had 14 days he suggested that with that much time we could change the plan a bit and go north to Martinique for two or three days. Paul agreed to change his plan and so instead of sailing south we set our heading northward.

We loaded Turis with enough food and bottled water for at least five or six days. We spent Saturday night on board in the marina and planned to leave for Martinique early Sunday morning.

After morning coffee, excited, we left the marina, turned the corner out of Rodney Bay and headed north for Martinique and Sainte Anne. The crossing was about 21 miles in Saint Lucia Channel, about the same distance as English Bay to Silva Bay across the Salish Sea. The difference though, is that if you did a 90 degree turn from our starboard reach to Sainte Anne and headed due east, your next landfall would be the east coast of Africa across 2,500 miles of Atlantic Ocean.

There was some swell. Boaters in BC can get the same feeling by heading west out Juan De Fuca Strait or circumnavigating Vancouver Island but when we stay south of Port McNeil and north of Victoria, we don’t often get that experience. On this day we had 20 knots of wind on our starboard beam and a six to eight-foot swell. It was wonderful. Turis was solid and powered along at about eight knots, under blue skies and a warm wind!

Sainte Anne is on the south end of Martinique and is a very popular anchorage for cruisers. There was pulsating music coming from the small town on shore. We had a post-anchoring beverage (banana rum became our favourite) and a swim, then we jumped into the dinghy and headed for the beach to register at the customs office.

I’m a fairly sheltered BC boy, so to stumble through the narrow, old streets of Sainte Anne amidst large crowds gathered to celebrate Mardis Gras, was frankly, surreal. Costumes, music (mostly drumming), dancing and frenetic energy made for a powerful cultural experience and we soaked it all in as much as we could.

We wandered around looking for dinner and ended up at a chicken barbecue spot with an outdoor table. Regulars sat around the cook watching the festivities, while we enjoyed local Martinique cuisine.

We spent one more day sailing Martinique’s south shore over to Anse Dufour for our second night, and then headed south again, back to Saint Lucia on the third day.

Day three was a 40-mile sail back to Saint Lucia and Soufriere Harbour on the west side of the island. Soufriere is a popular stopover for cruisers as well as land-based tourists because of its stunning geography and proximity to volcanic mud baths (apparently the mud works miracles on your skin) and a waterfall you can play in. The Pitons are two volcanic spires that rise quickly

from the shoreline to 800 metres.

Paul and Janet were familiar with Caribbean cruising and told us ahead of time about “the boat boys,” locals with small boats who would come to your boat and offer to help you tie onto mooring balls. In some anchorages, they’d taxi you to shore for dinner out or a day’s adventure on land. Nigel and Clyvus (our first “boat boys”) met us 40 minutes away from the anchorage in their beat up 12-foot rib. This took some initiative as it was still gusting to 20 knots with decent sized waves. They made it pretty clear (shouting across the wind and waves) that they’d look after us well in Soufriere. It was a sales pitch we found hard to rebuff.

We secured a mooring ball, had a coconut rum and waited for the guys to come back to take us ashore for a customs check-in and dinner out, saying

Salt Whistle Bay, Mayreau Island.

they’d pick us up after dinner at 20:00. The customs agent recommended “the best dinner in town” so we ate at Waterfront De Belle View. The boat boys took us back to Turis right on schedule.

Nigel and Clyvus showed up the next morning, as planned, at 08:00. Nigel’s ‘cousin,’ Mano, would meet us at the dock with his van and take us to the mud baths and the waterfall, and we’d be back at the dock by 11:00, at which time Nigel and Clyvus would deliver us back to Turis

After a 20-minute trip inland, punctuated by Mano’s commentary on

jungle agriculture (coffee trees, mangos, cinnamon, cocoa) we pulled into a nearly empty parking lot carved out of a hillside. Because we were so early, the tour buses hadn’t arrived yet, so we had the place almost to ourselves. We soaked in hot water from the volcanic outlets, then covered ourselves with a thin mud from the buckets beside the pools. It was delightful, but I’m pretty sure I didn’t look any younger after.

We jumped back in Mano’s van, still sporting a film of dried mud, and he drove us to the waterfall to shower off. Again, we beat the tourists. Mano proved to be a great host and we laughed at his banter and colourful stories.

Unfortunately, Nigel and Clyvus were a bit late for the pick-up in Soufriere, and when they arrived at the dock, it started to rain—monsoon style! The

six of us pulled away from the dock in their dilapidated rib (one side of the pontoon partly detached from the aluminum floor) at full throttle. We held on tight, put our heads down and experienced the most invigorating dinghy trip of our lives. I felt like a kid at Playland going down the roller coaster with my arms in the air, in the pouring rain, except we were hanging on for dear life. Soufriere was an adventure we will never forget.

That afternoon, we slipped off the mooring ball and sailed 12 miles to Vieux Fort on the south end of Saint Lucia, where we anchored for the night.

The following morning, we motored around the southern tip of Saint Lucia and headed south across Saint Vincent Passage, choosing the east side of Saint Vincent, hoping for the more consistent trade wind. The wind was fine but a strong current was against us so on with the motor and that afternoon we arrived at Princess Margaret Beach and Port Elizabeth on Bequai Island.

Port Elizabeth is a large, protected bay and a very cruiser-oriented town with dozens of sailboats at anchor and many great restaurants and small shops. We enjoyed poking around this beachfront town, taking in the local charm and friendly vibe. The next morning, we headed for Friendship Bay on the south end of Bequai.

A day later, we sailed to Paul and Janet’s favourite destination: Mayreau Island and the Tobago Cays Marine Park. Turis pulled into Salt Whistle Bay in the early afternoon. The trade winds moved over a small headland into the bay, surrounded by palm trees and white beaches. Holding was good in sand and the anchored boats were well spaced. We swam over to the beach and walked to the other side of the headland toward Tobago Cays Marine

Park. A dozen boats sat at anchor, their noses pointed in to the wind, looking toward Africa. That’s where we’d spend the next night.

This is an area where locals depend on cruisers for their livelihood. Their main offering is a lobster dinner on shore at one of the many cooking huts set up with outdoor tables, servers and good food. We were approached almost immediately after dropping anchor by a young fellow in a brightly coloured boat who offered to cook us the “best lobster dinner in the area.” But it wasn’t till the third night that we decided on a crew to make us dinner. The first two nights we stayed on board and ate fresh caught Mahi Mahi that Paul and I caught during the sail down to Mayreau.

We spent the following day and night out in the open, on a mooring ball east of Mayreau, sheltered only by the reefs that protected Tobago Cays Marine Park. We snorkeled with turtles and brightly coloured tropical fish and reveled in the beauty of the place.

Several more local boats came to Turis to offer lobster dinner or fresh fish, but one business man from Union Island stood out for us. Sydney made the trip from his home in Clifton to the Cays (about two miles) every morning in a 16-foot boat with an older Yamaha motor. But the trip is across virtually open water so he had to manage pretty big seas most days. As well as T-shirts, he sold fresh baked breads and banana loaf.

We spent the morning enjoying Sydney’s good humour and wonderful smile as he told us about the islands, his work, where we were from, our kids, and how to treat sore backs. We laughed a lot, then bought some bread and shirts and ordered fresh bread for the next morning. Eating warm, coconut bread in Tobago Cays Marine Park is something I won’t ever forget. On the morning of the third day in

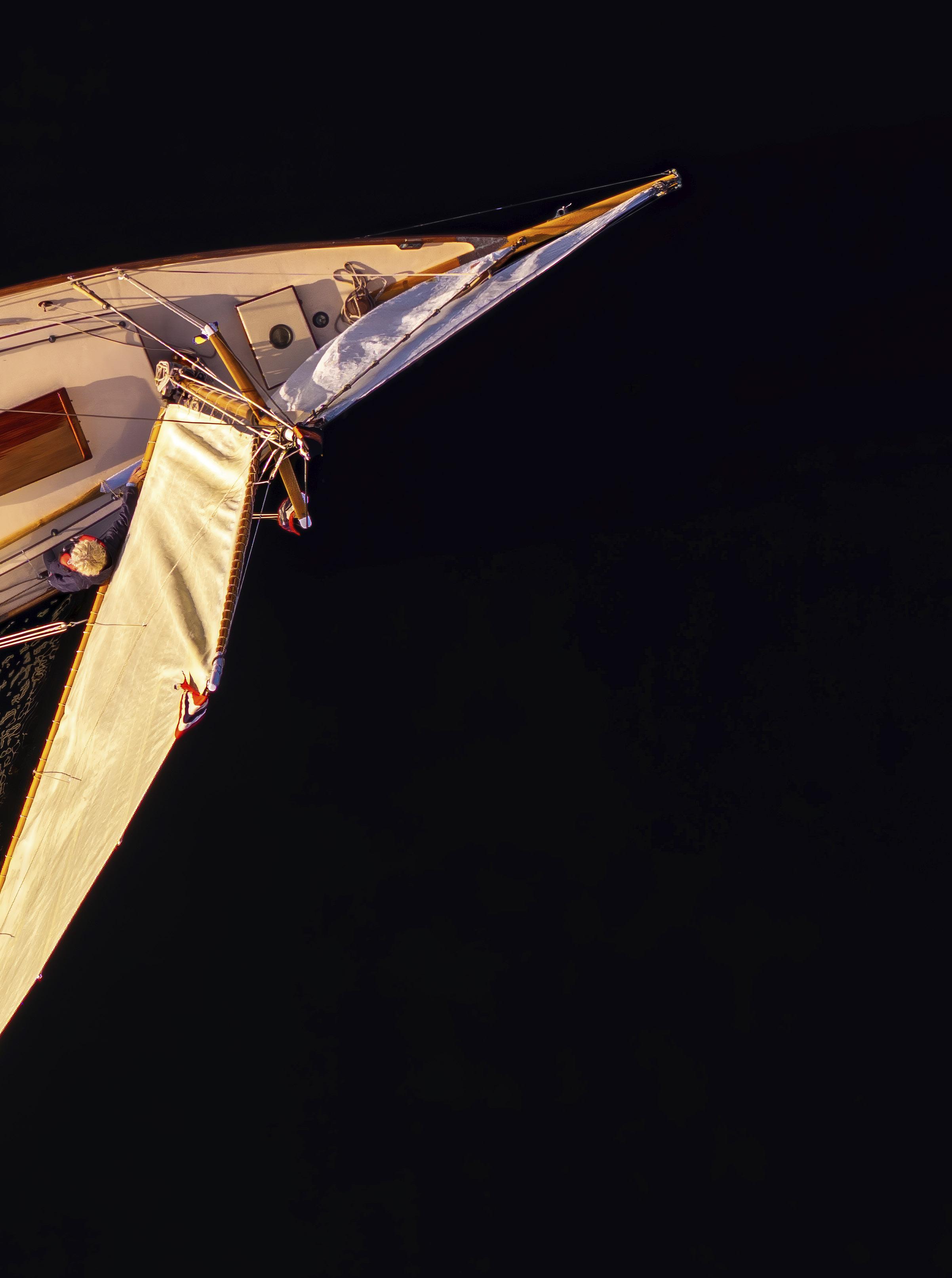

the area, I took a coffee on deck before the sun rose and wandered to the bow of the boat. A warm wind blew and beams of light highlighted the low clouds on the horizon. Across from us, a catamaran swung easily on another mooring ball—their crew enjoying the same beautiful view.

The sun’s first crack on the horizon and slow movement into the sky was almost overwhelming. As it continued its ascent, it was easy to understand why ancient cultures worshiped

the flaming ball. I sat for a long time, leaning against the mast soaking in the warmth and beauty of the new day, the Saint Vincent burgee below the starboard spreader snapping its response to the wind. It was the start of a wonderful day. That evening we went ashore for the famous lobster dinner, the four of us floating amidst the intoxicating rhythm of good food, togetherness, and the beauty of the place.

The next morning, after coffee and warm coconut bread delivered by Sydney, we slipped off the mooring ball and headed south for a short sail to Clifton Harbour, on Union Island. That afternoon, I sat outside a small shop in Clifton with the owner, while she made me a replacement bracelet (small ocean-coloured beads and two each of red, yellow and green) for the one I’d lost in the mud bath on Saint Lucia.

From Union Harbour, we sailed to Tyrell Bay, on the leeward side of Carriacou and once again did the customs dance for Turis and her crew. Paul handled all the documentation and signing-in duties for our trip like a pro. We were now in the country of Grenada, our last stop before the return home.

Over the next few days, we saw a foundering charter boat on a white sand beach on Sandy Island, snorkeled the underwater sculptures at Dragon Bay Marine Park and finally arrived in Saint George’s Harbour at the south end of Grenada. We had sailed roughly 250 miles and were never without a good breeze.

How fortunate to have been in the Caribbean and to have sailed, explored, and felt the wonder of it all with close friends who we now share these memories with.

At 31+ feet long and just under 10 feet at the beam, the Adventure is the biggest, toughest, most capable boat we’ve ever built. The 55° bow entry deadrise keeps you safe as you cut 1462

A father and daughter’s 4,400mile offshore adventure

& PHOTOS BY

Over the last year, my partner and I had sailed our 1981 Tartan 42, Footloose, from BC’s Inside Passage to the alluring waters of Mexico. While many people my age were buying houses and having kids, I was chasing the dream to sail south for a year. We weren’t ready to become lifetime cruisers, but we were ready for a year of adventure. At the risk of over romanticising life on the water, our year consisted of downwind sailing, surfing remote breaks and diving in the rich waters of California and Mexico. We met cruisers who were ready to help us troubleshoot broken water makers and locals who became lifelong friends. But life moves on and as our plans and goals shifted it was time to make a decision. What next?

I BOBBED AT anchor in La Cruz de Haunacaxtle, Banderas Bay, Mexico, taking in the sunset. Many of our friends who I shared the anchorage with were preparing to cross to the South Pacific. It was an alluring op -

tion. Tahiti’s lush green hills and turquoise lagoons sounded ideal. But crossing the equator meant committing to the lifestyle for another year at least.

I sent an inquiry to a company from Europe that ships boats around the world. For $25,000 we could put the old girl on a big ol’ freighter and fly home in first class with no worries to be had. Although possibly a great option for a sailor with a larger budget than ours, I quickly put the freighter option aside.

The simplest option would be to sell the boat right then and there. We sailed south and completed the goal, didn’t we? With a lump in my throat I hung up a for sale sign. The first weekend I showed her to a few people with sparkles in their eyes and dreams of cruising Mexico’s waters. No one was ready to commit and in hindsight, neither was I.

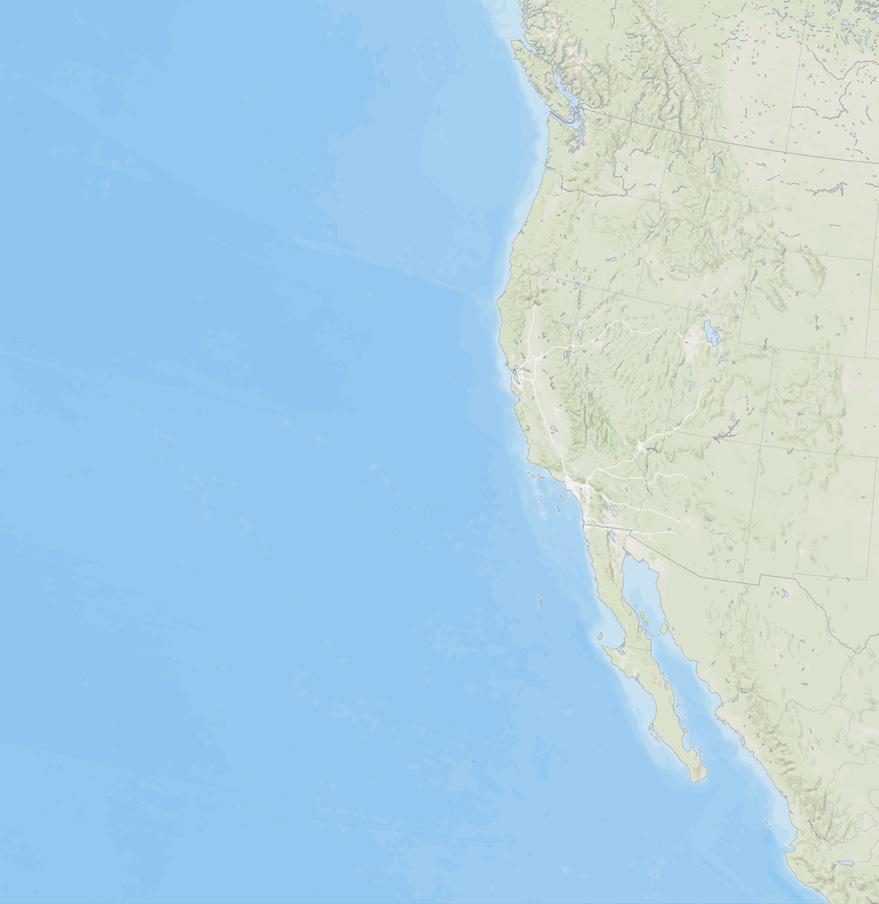

THE NORTH PACIFIC Ocean has a clockwise prevailing current direction. There is a reason people sail south and not north. Not that it can’t be done, but the ocean isn’t as simple as a highway which goes both directions. Sailing the same coastal route home is an option, but it wouldn’t really be sailing. The Baja Bash is what cruisers refer to the trip north. If you’re patient enough you can put the canvas up, but many choose to make the most of their iron genny and take the weather windows when they can from port to port. It would get us home to Canada, but would it be enjoyable?

That left one option. I had plotted our route on a chart that was passed down from my parents who did the same trip south in 2007. The chart had route options marked on it. A faint pink line arcing away from the coast was labelled

“the clipper route. I googled it and didn’t find much info, but I did manage to learn more about the history of the name. My browser tabs were quickly filled with the history of the schooners that used to sail around the world to trade and deliver merchandise, and the clipper races that followed their paths to Hawaii and then Canada. Hawaii didn’t really appeal to me at the time. My dad and I had sailed from Victoria to Hawaii in 2016 and although it was a wonderful trip, I wasn’t interested in adding more miles than needed. Plus, Hawaii is an expensive place for a budget-conscious cruiser. I continued to sail in Mexico and even got confident sailing our boat solo. As my cruiser network grew, I started sharing my intentions of sailing the Clipper Route. I finally came across someone who knew someone who had done this route, twice. Suddenly, this 3,500-mile mission felt feasible. Craig and Vicky’s email was the deciding factor I needed. With purpose and a new sense of vigour, I tackled projects that would turn my ocean capable boat into an ocean crossing boat. The goal was 30 to 40 days at sea. We were told the end of May would give us the best chance of avoiding hurricane season in Mexico and arriving in Canada late enough that the low pressure systems that sit off of Alaska would be diminished.

LIKE IN 2016 when we crossed to Hawaii, my dad and I were to set off on this grand endeavour together, this time with myself as captain. My dad flew down to Mexico and we spent a few days prepping together. I spent hours removing cardboard and making bins of food for each week we were at sea. I made four bins and filled the

rest of the goods into any empty hold I could find. Jerry cans of diesel and our main tank were filled, knowing that we may want to use the motor to find the wind again. The water maker was serviced and our water tanks filled. At last, we checked out of the country and headed into the sunset.

Our first test came early and had the potential to separate us from those whose knowledge is limited to having read Sailing for Dummies. The pinched stern of our ‘80s IOR boat meant that the control line from the windvane to the wheel didn’t have much room to adjust and the line was repeatedly popping off the wheel drum. Our first week kept us on our toes as we modified the setup. Eventually, we used a bin lid with zap straps to prevent the line from jumping off the drum.

The next challenge was spotted on day three. We were approaching Socorro Island when we first noticed the water gauge. Socorro Island is part of the Revillagigedo Archipelago, a Mexican military base which is also known for its incredible diving and a small anchorage off its south side. Our 70-gallon water tank was reading at about half, despite making five gallons of water a day on top of the tank being full when we departed Mexico. We seemed to have a leak. We could put the anchor down for a night to rest before retracing our tracks, but the thought was devastating. A lump built in my throat as we dove into the bilges looking for leaks. Finally, it dawned on my dad that I had worked on the bilge pump the night before leaving and had opened the valves of the tank manifold to get better access. My negligence meant I didn’t close them again and in the lumpy seas the water from the main tank was making its way forward to a

hose that I knew had a leak, typically this valve stays closed for this reason. With relief, we slipped past the Revillagigedo Islands at night, deciding to charge forward while we could and avoid a large high that was threatening us over the next week. I worked hard to double our water production and slowly the tank was brought back to full. The line pulled taut and my heart leaped when I popped my head out of the hatch. A flash of yellow and green signalled I had caught my first dorado. It was small, but the perfect size for the two of us and a big relief for our stomachs. During our first week we had is-

sues with the fridge compressor turning itself off due to overheating when trying to bring all the new provisions to temperature. Luckily, we caught it early, but it was too late to save the meat that wasn’t in the freezer. We reluctantly threw out the dinner I made while being tossed around in the galley that evening and decided to chuck the rest of the sausages that made us almost hurl up said meal. So, fresh Dorado was a huge morale boost.

DECK AND RIGGING inspections were part of my morning routine. Footloose was working hard and we were nearing a year and almost 4,000 miles since having our rigging replaced. It is crucial on a long passage to ensure that chafe points are monitored. So, I crawled along the starboard side, the deck cool under my feet. My eyes scanned the boom vang, up the rig and the sails looking for anything unusual. My fingers brushed over the turnbuckles. I dug my nails into the rigging strands looking for any sign of cracking or movement. My breakfast threatened to come up when I felt a strand ping out from the swage in the lower shroud. I clung to the rigging and yelled to my dad. Tomorrow’s weather was forecasting up to 30 knots; we were crossing into the trade winds that push sailors from California to Hawaii. We assessed the situation. We were 21 days and 1,800 miles into our journey, which had been entirely on a starboard tack. Hawaii lay to port, 800 miles downwind. California was to starboard 1,000 miles upwind. Canada was 1,800 miles off our starboard bow. Realistically we knew that we weren’t halfway. Hot tears fell down my face. I felt as though I had failed as a captain.

Our lower shroud rigging is a beefy 7/16” yet the size is needed as we only have a lower and an upper shroud. The 7/16” of stainless is composed of 19 strands—18 strands wrapping around a single thicker strand. Were the other strands about to break too? I’ve never felt so vulnerable. I suddenly questioned the integrity of the entire rig. Sailing offshore is a dance of trust between you and your boat and just like the strand, the trust was

Catching fish was a great way to supplement our diet, particularly after we had problems with our refrigeration unit.

An at-sea repair of the suspect starboard shroud.

broken at the moment. The large swell coming from the northeast meant that it wasn’t safe to head aloft. We instead lashed the spare forward halyard to the base of the turnbuckle and tightened it up using the main mast winch. It wasn’t a great solution, but it eased my mind a fraction. I adjusted the windvane to hold us at a slight broad reach so the backstay would take more of the strain. We would make more westerly, but it would be a safer ride. My first night shift brought stronger winds, but I felt okay as long as I was monitoring the sails. The forecast was calling for 24 hours of heavy seas and winds. All we had to do was to make it to the other side. I had no choice but to trust Footloose.

We didn’t get much sleep that night. The wind howled and Footloose creaked and groaned as she made her way through each crest and trough. Every slam from the swells hitting our hull had me leaping up in my berth. Anxiety was at an all-time high.

THE FIRST RAYS of sun streamed through the porthole and a wave of relief came over me. It was starting to get easier to manage the anxiety the longer the system rolled through. We told ourselves that we still had 18 strands of metal holding the mast up and we were sailing as conservatively as possible. There was not much else we could do.

Three days later the weather passed. We entered the high. The seas completely flattened over the course of a few hours and the clouds fell behind us. Never had I been more excited to change tacks. But first, we had to come up with a way to tension the starboard rig with a backup shroud. I dug through my spare lines and rigging parts and my dad hauled me up to the spreader. Despite the seemingly calm seas, the boat still lurched back and forth. I clung tightly with my legs, feeling the bruises form on my inner thighs. I ran a dyneema shackle through the upper tang, and back on deck we created a

tensioning system using some stainless rings before running the halyard back to the large cockpit winch. We then seized the rings together at maximum tension. Perhaps it wouldn’t last through a hurricane, but I felt more at ease. In celebration of both our ingenuity and what we decided to be a realistic halfway point, I cooked duck confit on wild rice and we cracked open a beer.

The next week was a new test of patience. The high broke up into pieces as we entered it and we danced between patches of wind. With frustration we turned the engine on and off in hopes that we could reach the next patch of wind—just so we could sail out of it. After all, this is why I had brought so much fuel. Without an autopilot, we sat at the helm and hand steered on and off for a week. It was like a game of tag with the wind. In an effort to save fuel for the entrance into Victoria, we turned the engine off and slept. I ensured the AIS alarm was on and sleep we did.

WE CONTINUED BARRELLING toward Canada, now with more wind than we had hoped for. We contemplated heaving to and waiting for the strong northwest winds to pass, but we worried that it would add another week to our trip, since the wind was forecasted to die. I prepped for this system by taking down the bimini and

the solar panels that were strapped to it. I rolled in the fishing lure and we bundled up in our foul weather gear ready for the cold, wet North Pacific weather.

Breaching humpbacks, sharks and floating kelp marked the end of the system and signalled our crossing the continental shelf. I brought our anchor

on deck and as I was reattaching it I spotted a snowy peak poking from the horizon. Land Ho!

All told, our journey was 44 days, and resulted in the completion of a 4,300-mile loop in the northeast Pacific Ocean. Despite the challenges this route gave us, I couldn’t be prouder of Footloose, my dad, and myself as captain.

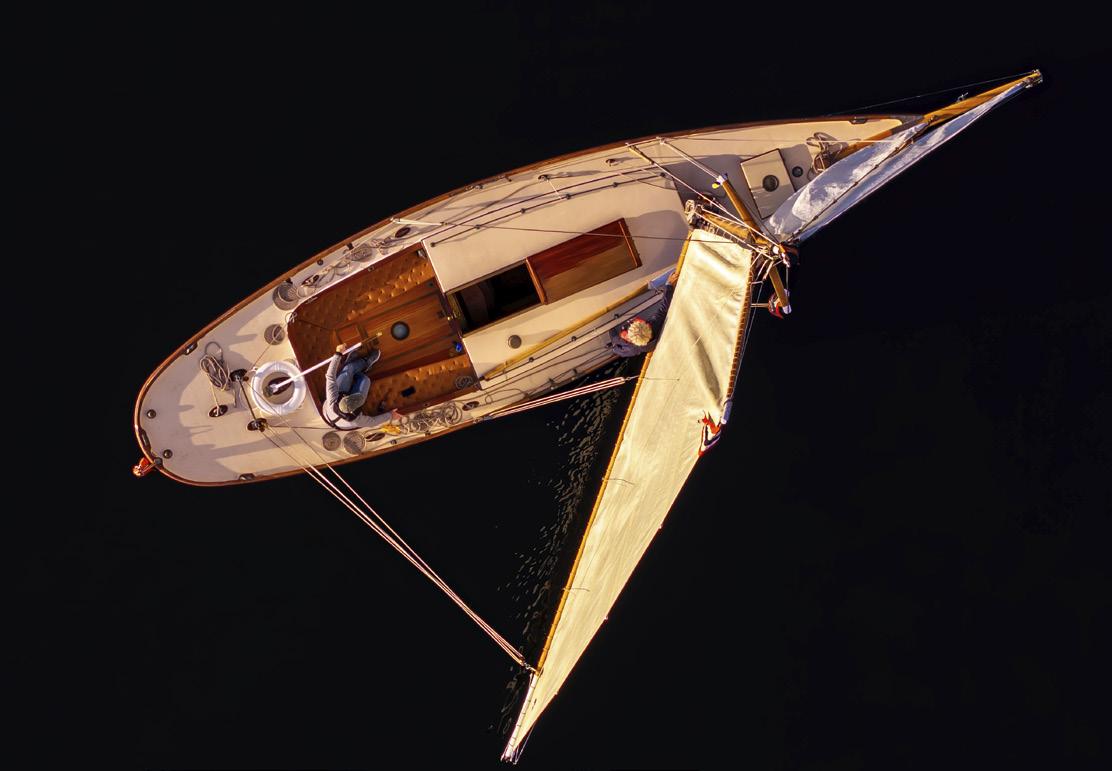

Dorothy showed off her new life throughout the summer of 2024 for sailors young and old

BY MARIANNE SCOTT

SV DOROTHY

IIn 1995, Kim Pullen, then of Port Sidney Marina, donated his beloved sailboat, Dorothy, to the Maritime Museum of British Columbia (MMBC). At nearly a century old, the vessel had developed a series of geriatric problems and for a few years, MMBC stored her in safe places. In the early 2010s, however, the museum decided the iconic yacht with its long local history, had to be preserved and take pride of place in its collection. It took more than a dozen years to restore her former robust structure and elegant demeanor.

The 30-foot carvel-built, gaff-rigged, twin-headsail sloop, designed in 1892 by UK naval architect Linton Hope, was commissioned by barrister and Clerk-of-the-Legislative Assembly William H. Langley and constructed in John J. Robinson’s boatyard in Victoria Harbour. She launched in 1897. Langley kept Dorothy for 47 years, racing and cruising her in the Salish Sea and winning her share of trophies. Thirteen subsequent owners kept her racing and cruising, each adding their own signature to the yacht.

Shipwright/artist Tony Grove was the first to work on Dorothy in his Gabriola workshop, making her structurally sound again. Subsequently, the Ladysmith Maritime Society’s group

of volunteers led by boatwright and Dorothy historian Robert Lawson rendered her into an historically accurate and sail-ready condition and made her sparkle as if newly born. Classic Boat, an internationally renowned British magazine featuring vintage vessels, honoured the meticulous refurbishment with the 2024 Award for “Restored Sailing Vessel of the Year under 40 feet.”

THE MUSEUM THEN pondered how to show off its gleaming, newly seaworthy vessel. “How can Dorothy become a living, purposeful sailboat, part of the marine community and not just a museum piece?” MMBC volunteer board member and activist Angus Matthews had some ideas. He and his spouse, Sandy

and Sandy served as Dorothy’s main ambassadors throughout the summer.

The inclusion of the youth sailing program was another iteration of Angus’ devotion to environmental and marine education. He spearheaded the establishment of the Shaw Ocean Discovery Centre in Sidney, developed the aquarium’s design, supervised its construction, helped raise $5.5 million and became its founding executive director. The centre offers ocean education for youth—and adults—through its displays of numerous marine creatures, its wet labs and microscopes.

LANGLEY KEPT DOROTHY FOR 47 YEARS, RACING AND CRUISING HER IN THE SALISH SEA AND WINNING HER SHARE OF TROPHIES

Matthews, once owned Dorothy. Angus had already served for years as liaison/ ambassador between the museum and the various people leading Dorothy’s resurrection. He’d also been instrumental in fundraising for the project. He thus developed a plan to show Dorothy off this past summer at clubs, regattas and festivals along the coast and to take small groups of kids aboard to experience sailing like their great-great-greatgreat-grandparents once did. Angus

His interest in youth education was reinforced when he joined Metchosinbased Lester Pearson United World College as an administrator. He wrote endless missives to federal and provincial agencies to gain permission to establish the 11 Race Rocks islets, lighthouse and rich flora and fauna as an educational laboratory for Pearson’s international students. Eventually, his persistence paid off and students have provided environmental stewardship on Race Rocks ever since.

DOROTHY’S SUMMER TOUR began with the late April Opening Day Sailpast at the Royal Victoria Yacht Club (RVYC) where she led the fleet. “Between April and September, we covered a lot of Dorothy’s original cruising grounds,” Angus said.

RVYC has a special relationship with Dorothy. After commissioning the yacht, Victoria Yacht Club member William Langley kept her anchored in front of the built-in-1895 clubhouse floating on pontoons in Victoria Harbour (the Club was founded in 1892). Langley also served as commodore for three years—1904, 1905 and 1906—five years before the Club was

granted its royal warrant. In addition, Dorothy is the only vessel dating back to the yacht club’s original fleet. To celebrate that history, Dorothy’s summer tour was sponsored by individual yacht club members who donated $10,000 to cover such operational expenses as insurance, escort vessels, accommodation and temporary wharfage.

The tour was crewed entirely by volunteers. Although a Torqeedo electric motor can be attached to Dorothy to get her out of tight harbours, Angus and Sandy towed Dorothy with their 33-foot powerboat Avanti, to the various events and locations where young sailors could learn from this unique sailing experience. Captain Bill Noon’s MV Messenger III and Trish and Casper Schibli’s MV Westerner also provided some towing.

Dorothy’s second stop took place at the Sidney-North Saanich Yacht Club where she was admired for her longevity and sleek lines. “The weather wasn’t suitable for sailing,” said Angus, “but we had plenty of youngsters closely inspecting the boat. They opened every locker and they all wanted to blow the made-in-1894 bugle.”

Dorothy also visited the BC Boat Show at Port Sidney Marina, not to put up a “for sale” sign, but to show herself off. “One interesting factoid,” said Angus, “is that we allowed all visitors aboard with their shoes on, while all those plastic boats required shoeless entry. Our goal is to show she’s a living boat, not some precious artifact.”

Dorothy experienced a bit of a homecoming at the Ladysmith Yacht Club— it’s the community where the Ladysmith Maritime Society volunteers have toiled so mightily to restore her to her old glory and continue to install further refinements. She proudly led the Opening Day Sailpast fleet.

In mid-July, Dorothy showed up at Cowichan Bay’s 36th Annual Wooden

SV DOROTHY

Boat Festival. “We had some youngsters aboard,” said Angus. “And Robert Lawson and Nick Banks raced her in the Cowichan Bay Regatta. Amazingly, Dorothy won this regatta in 1914 and MMBC has the trophy to prove it.”

“One of our most popular sails was at the Salt Spring Sailing Club,” Angus continued. “We had an enthusiastic crowd on the dock.” The weather was perfect for Dorothy to sail from the dock across Ganges Harbour, with two youths aboard at the time and a total of 18 having a sail. Angus always hands the tiller to one of the young sailors. “Because it’s a sail, not a boat ride,” he said. Thus, he immediately passed the tiller to SSSC member Malikaa Clements, 14. She sailed Dorothy perfectly in the 10-knot winds. Angus told me she

sailed so close to the mark he’d become a bit apprehensive. But she cleared it without issues and he complimented Malikaa on her skilled handling of the boat. She remained silent. “Yeah,” said fellow passenger Aoi Otsu, “she won the Silver Medal at the BC Games this summer in her 420 dinghy.”

“It’s wonderful to see young sailors so confident,” said Angus. “Sailing, whether it’s solo or as a team sport, builds great life skills.”

I spoke with Malikaa afterwards. She’s been sailing for five years, starting when her dad advised her to take a summer class. “Dorothy’s a beautiful yacht,” she said. “So well done, so polished, everything seems so fresh and new.” She was surprised by how much weather helm the yacht exhibited. “Sailing a big boat was so different,” she said. “I really had to focus on sailing her correctly. I think we were moving at about five knots. It was both challenging and great fun.” Her next goal is to try out for the Canada Games. Aoi also com-

mented on his sail: “It was so fun and cool to experience sailing and skippering a 127-year-old sailboat! And I was surprised that Dorothy was still in such good condition.”

Other junior sailors joined Dorothy at the Maple Bay Yacht Club and she exhibited her chic look at the Classic Yacht Association Rendezvous in Ganges.

DOROTHY’S LAST VISIT ended where she began her summer tour: sailing with juniors at the Royal Victoria Yacht Club. From Cadboro Bay she sailed to the MMBC’s Classic Boat Festival held over Labour Day Weekend in Victoria Harbour. Normally, sailboats are required to douse their sails when entering Victoria Harbour as it also serves as one of the busiest airports in Canada. But the harbour master gave one-time permission for Dorothy to enter under sail, so with her 1928 ensign streaming in the wind and the original Victoria Yacht Club burgee with Langley’s colours on a pig stick atop the mast she sailed to her dock.

She attracted numerous visitors during the festival, including artists Liz Charsley, Richard Linzey and Janet Moore, who were part of this year’s Artist Aboard Program. They stood “before the mast” while painting the maritime scene.

During the traditional Sunday Sail Past (which she led) and Sail Race, Dorothy showed off why she won the “Best Restored Sailboat Award” at this year’s festival. She looked sleek and shiny out on the water.

Angus estimates that more than 450 people have been aboard Dorothy for a closer look and that 42 young sailors and one 97-year-old had the opportunity to take the helm under sail. “It’s been a successful summer for our local vintage yacht,” he said. “She continues to live and entice.”

Angus and Sandy have not confined themselves to taking only young people sailing during the summer of 2024—they’ve also accommodated someone at the other end of the age spectrum. Three years ago, Minneapolis-based Dorothy Zimmerman, 97, discovered that her namesake, SV Dorothy, was being reborn. She knew instantly that she had to sail aboard the vintage yacht and made it a priority entry on her bucket-list. She tracked down Angus and they began an animated email correspondence. Plans were hatched and on August 28, Dorothy Jr. as Angus dubbed her, with her ample white curls, puffy pink jacket and twin trekking poles strolled down the mesh dock at the Royal Victoria Yacht Club with two accompanying friends, Mike Sawinski and

Bente Soderlint. Finally, she met her pen pal Angus in person. The sailors promptly donned life jackets, boarded Dorothy and sailed into Cadboro Bay with the sun glinting on the water and a 10-knot zephyr wafting them toward Discovery Island.

“During the sail, the waters were littered with Optis, Lasers, 420s, even some Minis,” Angus said. “Dorothy was in the middle of this chaos with Dorothy Jr. at the helm. The 420s were holding at the race start line and we flew right by them.” The gods certainly smiled on Dorothy and Dorothy “It was euphoric,” Dorothy Jr. told me afterwards. “I thought I’d sail a bit on Dorothy but the additional boat ride and the hospitality were an out-of-body experience. I felt like ‘Queen for a Day.’”

Dorothy aboard Dorothy.

BY ALEX FOX