THIS PAST MAY long weekend, my wife and I took our kids out for our first backcountry adventure of the year. Our plan was to do a quick overnighter out to Indian Arm from Squamish to shake the cobwebs out before heading off on longer adventures this summer. This has been our traditional “quick backcountry trip” spot for years, and we’ve never been disappointed. We packed everything up and hit the road by 9:00 am on Saturday and made it to gravel by 10:30 am, expecting to plunge ourselves into the wilderness of the Indian River Forest Service Road and find an open spot to camp for the night. Instead, we were greeted by flagging tape and signs on a well-graded road, and a Fortis BC employee in a pickup truck who turned us back the way we came. It turns out that the Indian River FSR is now closed to recreational users as part of the Eagle Mountain to Woodfibre Gas Pipeline Project, and isn’t expected to fully open again for another two to four years. Now those in more remote parts of BC may be thinking, big deal, industry must go on and there’s plenty of other routes to take, but unfortunately for adventurers in the Vancouver area, this is yet another restriction on our ability to access backcountry areas within a few hours of the city.

Already in the past decade we have lost access to Britannia Mines permanently, parts of the Upper Elaho and Squamish FSRs, several hot springs, Joffre Lakes for selected periods, not to mention the majority of FSRs on Vancouver Island and the mandatory online booking for backcountry campsites in Garibaldi and EC Manning Park. I’m sure I’m missing lots of other examples.

Some of these closures are because of resource extraction companies putting up gates to protect their equipment, some are for First Nations cultural reasons, and others are because of the increased threat of wildfire and overcrowding, which are

all valid reasons. However, it seems like since Covid the default response to challenges is to close-down access rather than compromise or solve the issue at hand.

This also leads to me ask what the end state looks like for access to the backcountry in BC, and if this the canary in the coalmine.

If all roads accessing industrial activities are gated and closed, which ones will remain for us to access the land that we all pay taxes for maintaining? The same goes for forests in general and forest fires, and land with significance to First Nations.

And what are the future plans for the online booking system for backcountry areas: is the government going to increase the number of areas and campsites so we no longer need the system, or are they simply going to expand the online booking program to more spots in BC. I think we all know the answer to that.

Call me cynical if you’d like, but I can see a future where all land that isn’t bookable through a paid, online reservation system is simply off-limits to people looking for an adventure. It’s especially frustrating that the current process is already broken, with sites booked out within minutes of opening day, with people desperately hoping to get any spot available months in advance.

Certainly there’s a need to protect our backcountry areas from abuse and overcrowding, but as I’ve said on these pages before, I don’t think the answer lies in simply decreasing access to the outdoors. I guess we’ll see what the future holds.

It’s that time of year again, to take your best shot and send us your favourite pictures from the past year. Entries are open at bcmag.ca/photo-contest until July 22, so don’t forget to submit!

Dale Miller

Linda Gabris has been venturing into the outdoors to harvest wild edibles for over 60 years. The lessons taught to her by her grandparents, of responsibility, sustainability and a connection to the land are as important today as they were then. This book shares those lessons as well as tips and practical advice in a personal, easy-to-read style. Combined with a scientific field guide, Wild Harvest BC is the perfect companion book to take with you on your outdoor adventures.

has been venturing into the outdoors to edibles for over 60 years. The lessons taught grandparents, of responsibility, sustainabiliconnection to the land are as important today as then. This book shares those lessons as well as practical advice in a personal, easy-to-read style. with a scientific field guide, Wild Harvest BC companion book to take with you on your adventures. Over 70 recipes ranging from Wild Asparagus Soup to Hazel’s Hazelnut Brittle turn your foraging finds into delicious, So get out there and enjoy the bounty of Nature.

www.opmediagroup.ca

$24 95 SHOP NOW

I was born in Bralorne! My dad worked as a mining engineer in Pioneer Mines in the late ’30s and early ’40s.

Some years ago, a late friend of mine and I drove up to Bralorne to see what was left there.

From Bralorne we drove the rough, bumpy road to the remnants of Pioneer where my dad had laboured years before.

You pass right through Bradian on the way to Pioneer. We stopped to talk to a fellow named Louie who offered to sell us one of the deserted buildings for a couple hundred dollars (wonder what they want for them today?)

Also, houses in Bralorne went for $4,000 to $5,000—again what are they worth today?

I thoroughly agree with the editor—private property should be respected, watch for no trespassing and private property signs, and of course no vandalism.

Before my legs gave out, I’m 82, one of my favourite hobbies was exploring old building ruins of all kinds, I even wrote a short history of my favourite site—Swanson Bay, BC’s first operating pulp mill. However, I found myself scratching my head over Debby Demare’s letter on the mailbox page. What was the whining on about?

No lookie lous?! Well I remember this sign at certain garage sales, although I’ve never figured out exactly how one can find something to buy at a garage sale without first becoming a lookie lou?

Demare’s letter has all the feeling of this: we own it all and you can’t come near it. You can’t take any pictures. You can’t even look at it!

Some ranch around here, I don’t remember which, had a lake where it was traditional for anglers to go to fish for many years. The new owner—a rich American—cut the road off thus banning the frustrated anglers. When the matter

went to court the judge in his wisdom sided with the new owner. Why worry about the angling privileges of a few Canadian bums?!

The attitude of Debby Demare’s letter appears to be a combination of medieval feudalism and ultra-capitalism. It’s mine, mine, mine, all mine I won’t share it with anyone! Not a good attitude to have.

Dennis Peacock, Clearwater, BC

I read your editor’s note “The Concept of Private Property” and also the Mailbox “Lack of Respect from Visitors,” in the Spring 2024 issue. A pleasant thank you for Debbie’s note.

I found “Ready for Ts’zil” very interesting as well. My dad had moved his family to Pemberton in September 1959. He’d rented a home a few miles up the valley, so I’ve seen Mt. Currie for many years from different places in the Pemberton Valley and area.

The photo on page 56 which is Talon Pascal on his way down the slope, shows the airport it was in 1979 when I learned to fly on the grass runway.

I don’t explore the internet, but in the 1970s a ball team in Pemberton had driven Hurley pass to play ball in Bralorne. Many changes over the years.

Susan Cosalich, Boston Bar, BC

A thoughtful Canadian friend arranged for me to regularly receive your magazine. It is excellent, contains modern and historic information, amazing pictures and interesting articles. After me, many others enjoy it too.

All of our trips to BC were wonderful, made more so by the welcome of friends with whom we stayed. Sadly, many have died, as has my dear husband Doug. Aged

85, I retain clear memories of our BC holidays, often sparked by your magazine.

One such was opening the front door, rudely ignoring the postman, mesmerized by a hummingbird visiting the hanging basket nearby. I had never seen one before. Magic moment.

My late husband was a referee for the UK London Society of Rugby Referees. Stepping in from the touchline watching a game on the University of British Columbia grounds, he took over the remainder of that match when the referee broke his leg. In borrowed boots and shirt, all went well. I remember he was impressed by the fitness of both teams. Later comes a telephone call “Can he do so again on Saturday, how about Wednesday, and attend our referee’s society meeting Tuesday evening?” “Where is the meeting?” “Molson’s Brewery” Ha! Where else?

At home comes a thank you Christmas gift for Doug: a Fraser Valley Referee Society tie. He treasured that. At that time in the 1980s there was a serious shortage of qualified rugby referees. Happy memories. All good wishes to you and everyone who contributes to the magazine. Keep up the good work.

Joan Morgan, Surrey, UK

Send email to mailbox@bcmag.ca or write to British Columbia Magazine, 1166 Alberni Street, Suite 802, Vancouver, BC, V6E 3Z3. Letters must include your name and address, and may be edited and condensed for publication. Please indicate “not for publication” if you do not wish to have your letter considered for our Mailbox.

OSOYOOS IS A bit of a paradox. It’s one of the fastest-growing communities in the south Okanagan, but it still has plenty of rolling green hills covered in grape vines. It’s home to both Canada’s warmest lake and its only living desert. It has a smalltown feel, but it boasts a world-class cultural centre and a whole lot more.

Before you arrive, perhaps you “spotted it” from the viewpoint off Highway 3 just northeast of Osoyoos. Now you can get up close and learn about Spotted Lake from an elder who will tell you that “Kliluk” or Kłlil’xᵂ, as it was called by Okanagan First Nations for thousands of years, is a sacred site that has been considered a revered place of healing for centuries. During the summer most of the mineralrich lake evaporates leaving large, colourful spots ranging from blue to green to yellow, depending on the mineral makeup of each individual spot. According to a New York Times article back in 2016, Kliluk has a spot for each day of the year, but others estimate around 400 briny pools rich in sulfates, magnesium, titanium, sodium and other minerals adorn this lake in the summer.

Jump on the 8:30 am bus at Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre, located on the eastern side of Osoyoos Lake, for the Spotted Lake Tour. After that, you’re back at the centre in time for a guided walk and a “snakes alive” show. By now it’s lunchtime. Fancy fish & chips? From the Cultural Centre, a 20-minute walk along a sage-lined trail takes you to the Nk’Mip RV park and campground Footprints Bar & Grill on Spirit Ridge’s exclusive section of beach on Osoyoos Lake. Or get into the laid-back vibe at Spirit Beach Cantina, just behind Footprints and attached to the Nk’Mip Convenience Store. This outdoor beachfront patio features

fresh tacos. In the evening it’s a fun hangout to rub shoulders with the locals, enjoy live music and margaritas.

Besides the Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre, the Osoyoos Indian Band owns the Nk’Mip Canyon Desert Golf Course, Spirit Ridge Resort and Nk’Mip Cellars, which is the first Indigenous owned and operated winery in Canada. On its website, the winery says succinctly: “We are inspired to capture time in a bottle.” And their wine has received many awards. On another patio, Nk’Mip (pronounced ‘Ink-a-meep’) Cellars includes a restaurant serving fresh farm-to-table fare on its outdoor terrace, with superb views of the lake and surrounding hills.

We checked into dog-friendly Watermark Resort and within minutes strolled its sandy beachfront before going for a swim at the nearby doggy beach. With Watermark’s “Sip & Stay” package, guests receive a tasting passport, featuring larger signature wineries along with smaller artisanal options. (It’s advisable to make reservations at the tasting rooms.) Particularly with record wildfire seasons and last year’s devastating cold snap, winemakers and wineries across the Okanagan need our support. As well, initiatives like the #OkanagansGotIt campaign welcome guests to their tasting rooms. Videos on social media show warehouses filled with barrels and cases of wine with tag lines “We’ve got what you need,” “We’ve got wine,” “We’re open, come visit us.” Watermark’s 15 Park restaurant may also have what you’re craving. Chef Jeffery Young’s new

menu features exciting local ingredients. Or DYI at one of the poolside barbecues.

Miradoro Restaurant at Tinhorn Creek in neighbouring Oliver welcomes dogs—and with a glass of wine they will happily serve takeout. Chef Jeff Van Geest suggests picnicking at the Tinhorn Creek amphitheatre or the demonstration vineyard with duck liver pate on grilled sourdough with hazelnut and fig compote, followed by pork cutlet with blue heritage corn polenta with crispy bright salad. Maybe bring your doggo’s dinner to curtail drooling, or a safer bet—and easier to carry—is pizza from Miradoro’s wood-fired oven paired with a Tinhorn rose.

Not to be confused with the cultural centre, the Osoyoos Desert Centre is a 27-hectare preserve of dry scrub, including sage, antelope brush and prickly-pear cactus. Yes, we really have a desert in Canada—it’s the northern tip of the Sonora Desert that ends in Mexico. We opted for a guided tour because there is so much to see and learn from interpretive guides about the local fauna and flora along its 1.5 kilometre boardwalk, and much can be missed if you go it alone. Plan on spending at least two hours on the trail and visit the interpretive building with hands-on, interactive exhibits and a native plant demonstration garden showcasing desert plants.

Osoyoos Lake is a 23-kilometre-long watersports playground and brag-worthy, being the warmest lake in Canada. With three locations on the lake, Wakepilot makes it easy to enjoy water sports experiences such as paddleboarding (with the dogs) to sea-doos to kayaks. If you’re daredevil adventurous, rent an E-foil, which (I’m told) is basically a surfboard with a mast and wing (hydrofoil) that generates lift as the electric motor pushes the foil forward—the

battery allows for about an hour of flight time. I’ll stick with the paddleboard.

If you happen to be in Osoyoos on July 1 and you’re ready to party, the Osoyoos Festival Society is celebrating Canada Day with its 74th annual Cherry Fiesta, an all-day event starting with a pancake breakfast at Town Square followed by a parade down Main Street and family fun at Gyro Beach Park. It culminates with live music and fireworks. My dog’s favourite store has to be Osoyoos Home Hardware, stuffed with all things canines love and staff who are obvious animal lovers. And check out Elvis’s Fine Jewellery and Music Room on the corner of Main Street and Spartan Drive. It’s a hoot, and the owners are clearly having fun.

The Okanagan is filled with local fruit and vegetable stands that showcase the local harvest. Driving between Oliver and Osoyoos, be sure to stop and grab freshly picked vegetables and fruits, perhaps to chuck on the pool-side barbecue.

Osoyoos Desert Centre desert.org

miradoro.ca Wakepilot Locations: Desert Sunrise Marina, Spirit Ridge Beachfront (in Nk’Mip RV Park), and at Walnut Beach Resort. wakepilot.com Watermark Beach Resort watermarkbeachresort. com

BOOK REVIEWS

JUST 25 YEARS is all it took for what is now British Columbia to transform from being Indigenous land to a Canadian province. It almost didn’t happen that way and it had a lot to do with greed, furs and the Hudson Bay Company. It seems that the land we now know as British Columbia

was teetering in the balance, close to becoming ‘American Columbia’ instead. If it hadn’t joined the Canadian Confederation as a province, it could easily have been absorbed into the United States. So how did it happen?

Exploring colonial politics by examining James Douglas’s governance and communications with London’s Colonial office and delving deeply into private correspondence that only recently became accessible, Barman has woven this period of the province’s tenuous and complex history into a complete tapestry, a colourful work you never tire of looking at. Best yet, she is still top of her game in her ability to meticulously blend research with accessible and interesting writing.

Europe and the American fur traders were almost exclusively male. Some sent home for their wives or sweethearts but the wise married the women who knew and loved the country where they were born. Indigenous women helped their partners in every way: they were strong and could paddle well, they knew how to obtain and to store food, they understood their land and its moods and they could survive in harsh conditions. Thus happily paired, the men were more likely to stay in the area and to raise hardy children.

An interesting read that leaves us better informed about the history of the country we call home. What’s not to love?

illustrated by Lyn Alice Harbour Publishing, 120pp, $19.95

A good friend came over the other night, looked at the book sitting on my coffee table and exclaimed: “Oh! Can I borrow that? Jean Barman has the most amazing ability to make history so fascinating. I took her course at UVic and the whole class was mesmerized.” He didn’t get the book as I wasn’t finished, but what he said was exactly what I had thought after reading the first few chapters.

Known for her extensive primary research and her copious use of extracts and texts, which add credibility and life to the narration, Barman has also devoted one of the book’s eight chapters to Indigenous women and the role they played in BC’s mid-19th Century history. The gold seekers, the settlers, the immigrants from Britain and

I HAVE ALWAYS gathered nettle and dandelion greens and flowers in spring and rosehips and hawthorn berries in fall; Jason and Adams, however, have rocked my world. Who knew there was so much more out there patiently awaiting recognition? While my bookshelf contains many books on herbs and their benefits, none are anything like this handy little compendium. These two authors have managed to pack a whale of succinct information on 47 healing perennials into a minnow of a book that can happily nestle into a wide pocket. The watercolour illustrations by Lyn Alice, who also successfully collaborated with the artists in an earlier publication, contribute hugely to the book’s appeal as well. She tells me she’s inspired by nature and loves to create

botanical watercolours for clients throughout the world. That passion shows in the freshness and vibrancy of her art.

Some of the perennials listed are familiar friends, like arnica and fennel, dandelion and echinacea, but many are new to me and even some of the familiar herbs like lavender turn out to be more than just a pretty scent. Along with the benefits each herb offers, the authors give the when and wheres of planting it along with its care and often even a little of its use through history.

Both authors are well positioned to champion these modest and unassuming medicinal perennials. Jason, a Salt Spring Islander who founded Salt Spring Seeds, a mail-order seed company, is also the author of several popular books on seeds and organic foods and Adams runs his own medicinal herb business, growing

his products at a community farm in Agassiz.

From stimulating the immune system to aiding relaxation and sleep, soothing a sore throat to healing injuries, lowering blood pressure to relieving headaches, herbs are nature’s gifts and she offers them to us for free. How ironical that in return people strive to eradicate many of them as weeds!

Medicinal perennials should go mainstream.

— Cherie ThiessenFor more Local authors & local topics visit: thebookshack.ca

THERE IS NO denying that British Columbia has earned the epithet ‘beautiful.’ The province offers a bounty of aesthetic attractions for residents and tourists alike.

BC’s ocean, mountains, forests, deserts, rivers and lakes have inspired countless artists.

One of BC’s top tourist attractions is the assembly of totem poles in Stanley Park. Written language did not exist for many Indigenous people and the totem pole was a way to pass on stories. Today, there are artists who use their talent and curiosity to tell their own stories, to capture the history, geography and character of the part of BC they call home or to express their heart’s desire. Some artists draw energy from the hustle and bustle of city streets, others look to the animal kingdom, while others still seek divine inspiration to support their supernatural creativity.

Here is a variety of BC artists and their art, sure to entice and appeal to every discerning art lover.

Olga Sugden, and her Whimsical Creations

Sugden was born in 1962 in Ukraine, completing her art education in Europe with a focus on textile arts and later

book illustration. She is fortunate to have had her education in Europe, and her influences include such illustrators as Beatrix Potter, Gennadiy Spirin and James Christiansen. She attempts to maintain the original “old-timer” quality approach to her work. She splits her time between Vancouver and Roberts Creek.

There is an innocent poetry to her whimsical artworks. They can tell tales, or they can leave the storytelling up to the viewer. People see themselves in her work, or they may see the faces of friends and relatives. Either way, whimsical art delights and enchants, weaving a charming and spirited path through our imaginations. Drawing sketches—most of the time anywhere she finds herself—a lot of her ideas

come straight from her imagination, quite often inspired by life and the people around her. Her delightful painting of a woman catching words in a butterfly net recall her early days in Canada when she was learning English.

After sketching and finding interesting characters, she transfers the ideas onto watercolour paper or linen canvas, starting with graphite pencil, and then working with acrylic washes or watercolour paints. She tries to keep the beautiful texture of linen untouched, concentrating on the detail and the character. She uses a variety of surfaces, which include linen, wood, paper, metallics and stone.

Humour and whimsy capture Olga Sugden’s attention when she is creating her work. Sugden often can be found selling her delightful artwork in the Granville Island Market. goldeneggstudio.com

Charles van Sandwyk, a

Childhood experiences on his uncle’s South African farm coloured and shaped van Sandwyk’s life and his art. For as long as he can remember he was attracted to the vibrant colours and vitality of African creatures. He retained his love of nature and it grew after his family emigrated to Canada in 1977. He graduated from art school at Capilano College (now Capilano University) and was mentored by teachers who saw his potential.

One of his childhood heroes was Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island, and the outcome was that he too fell in love with a remote island and its inhabitants.

Van Sandwyk now divides his time between BC and Fiji where his simple grass hut, just steps away from the beach,

was constructed for him by the villagers who have adopted him as one of their own. Like the French artist Paul Gaugin who left Paris for the adventure and romance of Tahiti, van Sandwyk finds inspiration for his work in his beloved Fiji, but he returns to his charming cottage studio in Deep Cove to complete the paintings.

“By far my greatest source of inspiration is my lovely Fiji. I don’t mean the constant deriving of imagery from Fiji, but rather the joy of being there, and taking the time to develop ideas for paintings and stories—the freedom to be alone with one’s self. I love to embellish with borders and decorations. I am often, and quite accurately, accused of over-romanticizing my subjects.”

He recently opened a cozy little shop in Gastown which is filled with his artwork and where he will make visitors a

cup of tea while they browse among the many offerings.

One day a girl came into the shop and asked, “Did you get permission from his grandchildren?” she innocently inquired believing the artist was dead. “Oh yes,” he said. Finally, he told her the truth and she burst into tears, saying she had one of his books since childhood.

Van Sandwyk is a steward of beauty in everything he creates. His unique approach to both life and art is what makes his art his own and that is what collectors all over the world prize.

charlesvansandwykfinearts. com

Serhii Kolodka, Iconographer-in-Residence

Ukrainian artist and iconographer Serhii Kolodka is one of the approximately 185,000 Ukrainians who have arrived in Canada since the war

started in February 2022. A modern-day Michelangelo, he has perched precariously on scaffolding to paint giant icons on church ceilings in Ukraine. He was working on a big art project for a BC cathedral when the war began and he went back home to fetch his three young children. His wife, a doctor, remained in Ukraine for a time to offer her help.

The Kolodka family is lucky to be together now. Adult men between 18 and 60 had been banned from leaving Ukraine, but exceptions were made for those with three or more children.

Holy Eucharist Cathedral, a rather modest structure from the outside, houses an astonishing array of colourful icons on every wall, on the altar and even the ceiling. The golden age of Byzantine art flourished after 300 years of Christian persecution when artists turned away from the Greco-Roman style to develop an entirely new style. Laura Grady, organizer of the Annual New Westminster Art Walk, described this Ukrainian church as, “a hidden gem.” She was happy to include the Cathedral on the art tour.

“Each icon I create is a spiritual endeavour,” Kolodka explains, “blending realism that I so passionately love with the profound symbolism inherent in Eastern icons. This unique combination brings each piece to life, inviting viewers into a deep contemplation of the divine.”

All proceeds from the sale of prints are being donated to the Ukrainian army for drones and medical supplies.

Kolodka accepts contracts for portraits and he also offers a range of art courses from beginner to advanced levels focusing on the techniques and theology of iconography. serhiikolodka.com

The history of biennales was popularized by the Venice Biennale first held in 1895, but the concept of a large-scale intentionally international event goes back to the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, England.

This modern BC bi-annual public art exhibition brings sculpture, new media and performance work by celebrated

and emerging talent.

Prominent art dealer and art advocate Barrie Mowatt founded the Vancouver Biennale in 2002.

“During the 1986 Vancouver World Fair, we were selling ourselves as a world-class city. My objectives were to use significant art installations by renowned artists and to install these works in public spaces, directly on the grass and sandy beach where people

could actually engage in the artworks and discover works not easily visible because of the limitations of art galleries and museums.”

The Vancouver Biennale is unique among the 270 active biennales around the world, not only in the length, which often ranges between 18 and 24 months, but also in that its primary focus is on accessibility, engagement and installations that reimagine public space where people live, work, play and transit. The Vancouver Biennale’s objective is always to be ahead of the curve and

the need to reimagine the very definition of public space itself. There are three beloved art installations that have become a part of the Vancouver art ecosystem. Every city needs art and it has to be in the middle of the people.

A-maze-ing Laughter in English Bay, artist Yue Minjun used his own features to create the 14 cast-bronze figures. His intention was to use art to touch the heart of each visitor so they can enjoy what art brings to them. They were presented as a gift to Vancouver, thanks to a donation by Chip and Shannon Wilson.

Engagement located in Sunset Beach Park was created by American artist Dennis Oppenheim. Inspired by traditional engagement rings, the art installation coincided with the same-sex marriage debates taking place in Canada.

Osgemeos, six giants up in the sky, were conceived in the minds and hearts of Brazilian twin brother street artists, Gustavo and Otavio Pandolfo. It took a while to find the ideal location for their 70 foot (21.3 metre) murals. The unique spot turned out to be in the midst of the Heidelberg Materials cement plant on Granville Island.

The next biennale is slated for Spring 2026 through to 2028 and the focus will return to the original vision of the biennale, namely, Open Borders, Crossroads, Vancouver and the theme will be developed in conversations with the international curators and local indigenous leadership.

For self-directed Vancouver Biennale tours follow the cheerful yellow and pink signage vancouverbiennale.com/ exhibition-map/

to a bigger campus on Great Northern way.

Carr University, Discover the next Picasso or Van Gogh

Emily Carr University of Art and Design, formerly known as the Vancouver School of Applied and Decorative Arts, was officially established on October 1, 1925, solely dedicated to education and research in the creative fields. Once located on Granville Island, the university moved

Many graduating students who have shown in the yearend exhibition over the years have gone on to become renowned international artists. Douglas Coupland, Molly Lamb Bobak and Attila Richard Lukacs are just a few of the notable alumni. In fact, visitors are heartily invited to attend the year-end student exhibition to see if they can discover the next Picasso or Van Gogh! ecuad.ca

From Sunset Beach to Vanier Park, discover the sights and sounds surrounding Vancouver’s False Creek

BY DESIREE MILLERWWithin minutes of hitting the False Creek seawall you’re on a pathway to infinite exploration. You could cover this eight-kilometre, ocean-side pathway in a brisk two hour walk and enjoy stunning skylines, greenspaces and landmarks along the way. Or, make an adventure of it, and engage in the many different neighbourhoods that make False Creek such a popular destination. From Sunset beach in the West End to Vanier Park in Kitsilano, there is no shortage of options for rest or play.

VANIER PARK

Starting at the welcoming structure by Alan Chung Hung named “Gate to the Northwest Passage” Vanier Park has lots to enjoy in and around the area. Overlooking English Bay and West Vancouver, this knoll is known for its wind and is one of Vancouver’s most popular spots for kite flying. Around the corner is Hadden Beach, a small, quiet and dog friendly spot on the seawall. It’s also in close proximity to the Vancouver Maritime Museum, the H.R. MacMillan Space Sciences Centre and the Museum of Vancouver. The later two share the same building, designed by local architect Gerald Hamilton. Take note of the roof

design, which is inspired by traditional woven-basket headwear worn by the Squamish Nation. Bike lovers can deviate off the seawall just west of the Burrard Bridge to test out a hidden gem at the Vanier Park Bike Skills Track, a small bowl-style pump track for bikes.

This park was once the location of Senakw, a Squamish village that was seized by the federal government with its inhabitants relocated to Burrard Inlet at the turn of the 20th century. This action against the Squamish was later found to be illegal in the courts, and in 2001 an agreement was made to return five hectares of land back to the Squamish Nation, who is now developing the land next to the Burrard Bridge with several new condo towers totally 6,000 units.

One of the most popular beaches in Vancouver, Kits Beach is just around the corner from Vanier Park. Spend the day on a sandy beach, with gorgeous views of North Shore mountains and English Bay. Also available during summer months is Kitsilano Pool, a historic outdoor saltwater pool dating back nearly 100 years. The beach itself has basketball, volleyball and tennis courts, and a massive playground for kids. Across the street is a selection of coffee shops, restaurants, ice cream parlors and other goodies including the busy patio at Local.

From Vanier, keep walking east on the seawall toward Fisherman’s Wharf, an active commercial fishing hub, where you can purchase freshly caught seafood from local fishermen. Check falsecreek. com/fish-for-sale for the various dealers, and seasons to coordinate. Move onward to visit one of the most famous markets in Canada.

Located under the south end of Granville Street Bridge, the world famous Granville Island is a centre of activity. For waterplay, rent SUPs, kayaks, boats and other watercraft. It’s also a place to

Explore the thriving ecosystem of Habitat Island—also a great spot to enjoy the sunset.

Yaletown.

spend hours enjoying the public market for fresh produce, meat, cheese, baked goods, as well as shops featuring art, imports and homemade artisan products.

This is also a thriving core for the performing arts. Home to the Arts Club Theatre, catch improv, plays and live music all year long. The Carousel Theatre features awesome plays for kids of all ages, and Granville Island holds the campus for Arts Umbrella, a non-profit school for the arts, with classes in art and design, dance and theatre, music and film. This artistic influence is felt throughout the isand.

The Kids Market is a must if you have little ones or are young at heart. Crouch through the mini door on Cartwright Street, and enter into a playland of fun. The owner at Clowning Around Magic Shop is always up for a magic trick, and it’s impossible to leave without a gag or new trick in your pocket.

Onward toward Cambie Bridge is a three-kilometre stretch of luscious greenery, parks, playgrounds, community gardens and marinas. The walkway itself is a mix of concrete and cobblestones. Passing by an area known as Stamps Landing, stop at Mahoney & Sons or the Wicklow Pub for their awesome waterfront patios overlooking the city and inlet.

Keep going on the seawall and you’ll enter one of the most interactive sections of the seawall. The Olympic Village walk has mini bridges, three-person lounge chairs, benches, logs, grassy knolls and marshes that are all inviting to sit and hang for a while. Habitat Island is a popular spot for exploration. This urban sanctuary is a short hop from the main path. During high tide, it’s surrounded by water and is home to various native small animals, insects, crabs, starfish, barnacles and other animals. Trees, shrubs, flowers and grasses have albeen planted to make for a thriving little ecosystem.

Olympic Village itself is a great place to refuel with various restaurants, bakeries and stores. Visit the Tap & Barrel patio for views of Science World and BC Place, or grab a coffee and sourdough at Terra Breads before walking to the iconic geo -

desic dome built for Expo 86 that is now the home of Science World. This part of the seawall is one of the best places to catch a sunset with westward views of False Creek in its entirety.

Take a stroll off the seawall south of Cambie into the eclectic and everevolving area of Mount Pleasant. A 10-minute walk will transport you to a mix of heritage homes, warehouses, animation studios, tech centres, artisan work spaces, funky eateries and more. This unassuming area is tucked away with gorgeous views of the city, North Shore mountains and murals painted on buildings all over. As a brewery hub, there are at least 10 solid breweries all within a 10-block radius of each other, each with a unique feel and flavour. Some notables include 33 Acres, Brassneck, R&B, Electric Bicycle Brewing and tons more. visit bcaletrail.ca for a list to enjoy. For a different vibe, La Fabrique St-George is an urban winery with charcuterie-inspired finger food or Please! Beverage Co., a local distillery making refreshing cocktails and tonics.

Rounding the eastern tip of False Creek, you’ll cross over to the north side of the seawall. Here, Concord Community Pop-Up Park is a coveted greenspace that has become a local’s favourite spot to relax outside. With a mix of options, there’s basketball hoops, volleyball nets and lounge chairs sprinkled throughout the park. Ample tables make it a popular picnic and barbecue spot, especially when the patio lights go on at dusk, creating an intimate urban playground. Classic Vancouver venues appear on the horizon. Rogers Arena is home to the Vancouver Canucks and BC Place is where teams like Vancouver Whitecaps, BC Lions and Canada Sevens of World Rugby Seven Series can be seen through the year. It also houses the BC Sports Hall of Fame, which offers an insiders’

look to some of BC’s sporting legends. Check your schedule to see what event is taking place during your stay in this entertainment district.

Back on the seawall, refresh at Batch, a funky container-made-into-wateringhole at the Plaza of Nations. Perfect for grabbing a beverage on a hot summer day, Batch also attracts many during the winter months when the fire-pits are turned on. This midway stop is just under three kilometres to the end of the trek and makes you feel like you’re hanging in Vancouver’s backyard.

Beautiful parks line the path as you walk toward the roundabout at the base of Davie Street. Walking up Davie, you can explore the heart of Yaletown, an area that was warehouses and wasteland a mere 40 years ago, but is now one of Vancouver’s most trendy neighbourhoods. Mainland and Hamilton streets are the most popular for neat shops, eateries, coffee stops, boutiques and more. A mix of heritage buildings, revamped warehouse space and interesting architecture with patios on cobblestone streets makes this hood feel like a modern take on old Vancouver.

Vancouver’s historic Chinatown was a flourishing hub in the 1880s and 1890s, when Chinese immigrants flocked to the region to work in mines, farms and logging camps. A magnificent gate on Pender Street and welcomes you to a neighbourhood that has gone through some tough transitions over the years. New initiatives to revitalize the look and feel of Chinatown and inject some new energy are underway.

Some notable mentions include the Chinese Canadian Museum, authentic steamed buns at New Town Bakery or traditional dim sum at Jade Dynasty. Dr. Sen Yet Sen Classical Chinese Garden is also a beautiful escape into well-tended grounds, with koi ponds, pagodas and manicured gardens.

The stretch around David Lam Park and George Wainborn Park offers many opportunities to enjoy the scenery, either near the water’s edge or in the greenspace and parks along the way. When you’re under the Granville

Street Bridge, look for the Spinning Chandelier by Robert Graham, an art installation that got a lot of press for its $4.8 million price tag. However, when it lights up and spins at 12:00 pm, 4:00 pm and 9:00 pm, there are no shortage of observers taking in the show. (Note, from here look across the way to see Granville Island from a new vantage point, including The Giants, a public art installation on the concrete silos at Heidelberg Materials).

Vancouver House is a complex right under the Granville Bridge that features

The giant Inukshuk at English Bay Beach.

several great restaurants including Autostrada Osteria, a perfect pit stop for rustic Italian and the Milan inspired burger bar, Monzo burger.

As you pass under the Burrard Bridge and walk alongside Vancouver’s Aquatic Centre you’ll soon reach Sunset Beach. This charming beach is directly across from Vanier Park and at the entrance to False Creek, so it is a fantastic spot to sit and watch the boats coming in and out of the creek and English Bay. Enjoy gorgeous views of Kitsilano and Point Grey in the distance, and step up to Denman Street to explore the funky and historical West End neighbourhood.

If you’re inspired to keep going, you can stay on seawall and walk to English Bay Beach, which is the last beach before you enter Stanley Park. This beach is home to the annual Polar Bear Swim and a favourite vantage point for the Celebration of Lights fireworks festival. Here you’ll see the famous Inukshuk sculpture by Alvin Kanak, standing at six metres tall. A plaque near the work reads: “This ancient symbol of the Inuit culture is tradi-

tionally used as a landmark and navigational aid and also represents northern hospitality and friendship.”

Cut your walk in half and get a unique view of the city from the water via the Aqua Bus or False Creek Ferry. With stops at various landings around the seawall you can hop on or off at any of the neighbouring communities.

Or, all three of the bridges across False Creek to the other are walkable, with lovely walking paths to and from each (although Granville is currently under construction). Crossing the bridges offers a completely different perspective of the area.

During an expedition in the late 1980s, Captain George Henry Richards, a hydrographer of British Columbia’s coast was travelling through the south side of Burrard Inlet. Confusing his location as a creek, he soon realized it wasn’t a creek at all, but rather an inlet—and thus the inspiration for the name False Creek.

Stay

Downtown Vancouver has a wide range of accommodation options in all price ranges and styles. For closer proximity these are within minutes from the seawall:

Granville Island Hotel granvilleislandhotel.com

Opus Hotel—Yaletown opushotel.com

JW Marriott Parq Vancouver— False Creek North marriott.com

Eat

It’s impossible to list every special place to eat or drink in the diverse neighbourhoods of False Creek, but here are some honourable mentions:

Bao Bei bao-bei.ca

New Town Bakery newtownbakery.ca

Tap and Barrel Craft tapandbarrel.com

Terra Breads terrabreads.com

Honey Salt parqvancouver.com/food-drink/ honey-salt

Batch batchvancouver.com

Autostrada autostradahospitality.ca

Play

Science World scienceworld.ca

Vancouver Maritime Museum vanmaritime.com

HR Macmillan Space Centre spacecentre.ca

Museum of Vancouver museumofvancouver.ca

Granville Island Kids Market kidsmarket.ca

Seaplane Charters to Anywhere on the British Columbia Coast

Unique Experiences in Amazing Places

SCHEDULED

Up to 32 Flights Daily to Nanaimo and the Gulf Islands from Vancouver

A natural (unpainted) wicker basket is the best choice for gathering mushrooms. It allows them to breathe, which keeps them fresh until they arrive home in the kitchen. Plastic causes sweating and they can draw a “tinny” taste from metal.

IIf you love spending time outdoors and you’re looking for a fun activity the whole family can enjoy from spring through fall, I assure you there’s nothing more gratifying than foraging for edible

wild mushrooms in our province’s beautiful, diverse woodlands.

Going “mushrooming,” as grandma called it when I was kid, dishes up a whole lot of good eating. But before arming your loved ones with baskets and taking off into the wilderness on a mushroom hunting frenzy, it’s important to remember there are a number of species ranging from mildly to deadly poisonous.

The safest way to become a mycophagist (mushroom eater) is to hunt down an experienced mushroom forager whom you can learn from at first hand as I did with grandma. Not only will they introduce you to the edible picks but also, and even more importantly, they’ll steer you clear of the poisonous ones which grandma called “toadstools.” But don’t despair if you can’t find a knowledgeable picker to partner up

with. A finely-illustrated mushroom field-guide book is the next best thing for learning important details about appearance, season, habitat, distribution and other characteristics that will help you make positive identification before eating—which is the number one forager’s rule!

Mushrooms are the fruiting body of a fungus reproduced by spores. One mature mushroom on the verge of expiring can disperse billions (or in the case of puffballs, trillions) of minuscule spores but only a small percentage will germinate, due to unsuitable growing conditions. Spores that do not germinate can lay dormant for very long periods of time, even years, until the mycelia (known as the threads of life) are spurred into action.

Mushrooms thrive on a wide variety of living and dead organic matter such as leaf litter, trees, logs, stumps, shredded evergreen needles, moss, manure and so forth. Thus, areas rich in host materials are the most prospective places to begin your search. And, as I learned from grandma, the best time to go mushrooming is “the morning after a rain…”

So now it’s time to basket up! I recommend the top five mushrooms here for novice foragers to break ground on as they are commonly found and the easiest to positively identify—and most wild mushroom connoisseurs, including myself, sing the highest praises to these chosen few.

In recent years, morels have become a specialty item in supermarkets across the country while in season. So, if you’ve never seen one before, simply pop into the store and feast your eyes before heading into the field as commercial and wild are one and the same.

There are 18 species of morels and all are edible and delicious. The most commonly found and sought after are the Morchella esculenta (common morel), the Morchella

elata (black morel) and the Morchella semilibera (half-free, meaning its cap is not hemmed to the stalk as are other one-piece morels but rather flares out like an umbrella when mature). In the field, each species has a scientific name which you can learn to identify by using your guidebook. But in the kitchen, they are all morels!

The caps can be conical, egg-shaped, elongated with a rounded top or spherical, and range from black to various

Be aware of the Gyromitra mushroom (also known as “brain” or “false morel”). As the name implies, these mushrooms are brain-shaped and have rusty to dark brown irregular caps hanging free from the stalk.

shades of browns, grays and yellows. They have honeycomb-like surfaces with darker ridges and lighter pits. Morel season begins in later parts of April to early May and runs on into early parts of August, depending on weather and region which, naturally, applies to all mushrooms. Look for them on recently burned grounds, in rich moist leaf litter, on evergreen forest floors and along the edges of woodland trails and streams.

•Make a habit of only gathering young mushrooms in prime condition. Leave the old “fungi” undisturbed and they will repay you the following season with another bountiful crop.

•Practice good foraging ethics. Never strip a woodland patch of mushrooms bare, for if you do, your basket will come home empty the following season! As grandma used to say, “a special treat is just enough to eat…”

•Remember you cannot enter private land, First Nations traditional territories or reserves without receiving permission first.

•Use a knife or gently twist and break the mushroom off at the bottom of the stalk, leaving the base standing in the soil. This keeps dirt out of the basket and leaves spores behind for reproducing.

Even though they go under the name of giant puffballs, not all puffballs are gigantic. They can range in size from marbles and golf balls to baseballs and even soccer balls, with world record-breakers tipping the scales at around 50 pounds!

Puffballs are an excellent mushroom for beginner foragers to go after. Their round, plump snowy bodies are easy to spot growing in pasturelands, grassy meadows, clover fields and just about anywhere where there’s open ground to take a stand on, including lawns and gardens. Their season runs from early to mid-summer all the way through fall. At its prime for eating, a puffball has a beautiful white, smooth interior with a marshmallowlike texture. Overripe puffballs, those with pigmented (grayish to green) interiors and those which have turned “dusty” on the inside are long past their due date and are not fit for the table—but they are fun to step on! Stepping

on them prompts the mature puffball to expel its spores into a puff of gray smoke, spreading them far and wide which, so grandma used to say, ensures a bountiful crop the following season! Of course, before popping a puffball, you’ll want to close your eyes and cast a wish upon the wind…

In Latin the name means “good to eat,” and as an example of just how good they are, in France, chanterelles are made into a very exotic ice cream which is said (as I have not had the pleasure of sampling) to resemble the taste and aroma of fresh apricots.

I have been an avid gold prospector for many years (almost as long as I’ve been a mushroom forager) and I must admit, coming across a wood-

land patch of bright golden yellow chanterelles is every bit as thrilling as striking gold! And when the chanterelle patch is bountiful as they often are, I give thanks while cashing in on nature’s finest “motherlode.”

Chanterelles are commonly nicknamed “trumpet” mushrooms because they have a solid, one-piece funnel-shaped body which, upon maturing, resembles a trumpet. The cap is smooth and dry and slightly depressed in the

centre when young. They have wavy margins with thick, blunt gill-like folds extending down their lanky solid stalks. They range in colour from egg yolk yellow to pumpkin orange.

The most bountiful patches are usually found in deeper, darker, moister woodlands growing in leaf litter, amongst tree roots and near stumps and rotting logs. Their season runs from midsummer to later parts of the fall.

If you’re finicky about find-

•Wash mushrooms well under cold running water to remove sand and woodland debris. Pat dry with paper towels. Firm bodied, meatier mushrooms with their robust flavours (morels, chanterelles, boletes) can be used in place of store-bought mushrooms in almost any recipe— steak and pizza toppers, omelets, quiches, stir-fries, soups, stews and any other creation that needs a touch of woodland mushroom magic.

•Puffballs, with their mild flavour and smooth texture, are wonderful in omelets, cream soups and sauces. Shaggy manes,

ing worms in your wilderness gatherings, you’ll be happy to discover chanterelles are never, or should I say, seldom ever infested with bugs or worms as there’s no place on these beautiful one-piece mushrooms for creepy crawlers to hide!

Caution—be aware of Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca, also known as false chanterelles, which have hollow, flimsy smooth stalks and, unlike chanterelles, they glow in the dark.

containing a lot of moisture and very delicate flesh, do not stand up well in the skillet and thus are best-suited for soup and sauce making.

•Firm bodied mushrooms can be dried in a food dehydrator according to your machine’s manual or strung and hung, which was grandma’s old-fashioned method, in a warm place until moisture is gone. Once dry, unstring and store in a paper bag on the pantry shelf where they will keep indefinitely. Use dried wild mushrooms instead of store-bought dried shiitake, porcini or other dried mushrooms in all your favourite recipes.

(Coprinus comatus)

In Latin, the name means “with dense hair” which is why shaggy manes are often dubbed “lawyer’s wigs” since they resemble the fanciful wigs worn by lawyers in British courthouses. They are also known as “inky caps” because, upon expiring, shaggy manes leave an inky splat on the ground.

The mushrooms have egg-shaped white caps with a scale-like appearance and, when mature, they are about the size of a hen’s egg, which they resemble standing on end in the grass. They have hollow white stalks, which run from the base up through the entire body. The mushrooms are at their prime for picking when the caps are still egg-shaped, firm and white. Once the caps flare out, umbrella-fashion, and show signs of inky discolouration, they are no longer edible.

Their season begins in the middle to later parts of summer and runs onward into late fall. Look for shaggy manes marching along the shoulders of gravely backroads, growing in small groups on sandy grounds, in grassy fields, pastures, meadowlands and, yes, even in yards and gardens.

(Boletus)

Europe, especially in Italy where they are known as ing “little piggy” referring to their plump, chubby bodies, smooth skin and meaty texture.

The caps are convex when young and take on the traditional mushroom shape upon maturing. They are smooth and range from yellow and orange to tan and dark brown. The pores on the underside of the caps are tiny, round sponge-like structures (which is why they are often dubbed “sponge-caps”) and range from creamy to pale yellow. Stalks are white to cream with a bulbous base.

patches appearing after an autumn rain. down-side to boletes—mature specimens are often wormy. But, I’ve been told that bed of ice, the cold will draw the worms on the efficacity of this technique, I have a better solution; only gather young boletes which are usually worm-free and leave the mature mushrooms to feed the woodland nibblers.

CAUTION

The most prospective places to hunt for boletes are under conifer trees, on sandy grounds, in gravel pits and on mossy, spongy woodland floors. Boletes begin to appear in summer and continue to grow through fall with the most profuse

Avoid all species which have reddish pores, as well as those with flesh that turns blue when bruised as these are toxic.

Helmcken Falls in Wells Gray Provincial Park.

Helmcken Falls in Wells Gray Provincial Park.

TThe 340 kilometres of paved highway from Kamloops to Tête Jaune Cache follows the route of the Overlanders of 1862, the first survey route for the Canadian Pacific Railway, and the present

path of the Canadian National Railway. For most of its length, it follows the North Thompson River Valley with climatic zones varying from semi-desert at Kamloops to one of the province’s heaviest snowfall areas at Blue River. Traffic is generally much lighter than on the Trans-Canada Highway and the grades are less steep, making recreational vehicle travel less demanding on horsepower and nerves.

FIRST NATIONS TRADING CENTRE

Kamloops, the western junction of

Yellowhead Highway 5 and the TransCanada Highway, has been the centre of trade in the Interior of British Columbia for more than 30 centuries. The Shuswap group of the Interior Salish peoples found the climate mild and the food plentiful. The characteristic depressions of their long-abandoned homes can still be seen in many places near Kamloops. When traders from John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company discovered the First Nations settlement late in 1812, they were welcomed into the community. The Astorians established the first

and only American fur trading post on what is now British Columbia soil. The American presence was short-lived, however, and the post was soon sold to the Montreal-based Northwest Fur Company, which later merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Today, Kamloops is a modern sprawling city of close to 110,000 people. The fur trade has long slipped into oblivion, but remnants of the past cultures can still be found on display in the Kamloops Museum. Generally regarded as one of the best community museums

in western Canada, the Kamloops Museum houses a superb collection of Salish baskets and artifacts, plus reminders of the people who followed the original fur traders into the Thompson district.

Kamloops is also the transportation hub with highways coming into it from all directions. From the junction of Yellowhead Highway 5 and the Trans-Canada Highway at what was once the east side of the city, the Yellowhead passes under the morning shadow of Mount Paul, and

then heads north through the suburb centres of Rayleigh and Heffley Creek.

Heffley Creek is also the junction point for a highway leading eastward to several popular fishing and boating lakes and the Sun Peaks Resort area. Heffley Lake and Little Heffley Lake are near the road, while side roads lead into several other interesting lakes. Sun Peaks, 45 minutes from the Kamloops city centre, is one of the most accessible major ski resorts in Canada. It boasts of a

convivial atmosphere, ample accommodation, and a multitude of downhill ski runs to suit every taste and ability.

North Thompson River crossings are limited north of the bridges in Kamloops. The McLure Ferry, 43 kilometres north of the city, is one of BC’s fleet of free inland ferries. It can carry two vehicles and a dozen passengers and operates on-demand between 7:00 am and 6:20 pm, with a lunch break from noon to 1:00 pm. If you are interested in doing a bit of exploring, you could cross on the ferry and return to Kamloops or continue north to Barrière on the west side of the river.

Louis Creek, 14 kilometres north of McLure, is the gateway to Adams Lake and the network of big lakes that lie snuggled up against the Monashee Mountains. Agate Bay Road to Adams Lake is paved, but the rest of the roads in the area are busy gravel logging roads. There are several BC recreation sites on Adams Lake.

While snow may be the source of gold “in them ‘thar’ hills” today, many historians suggest that it was the discovery of gold in the tributaries of the Thompson River that triggered the rush that swept through southern British Columbia in the 1850s. Although not as rich as the bars of the Cariboo, the North Thompson and its tributaries did cause some excitement. While “Doc” Keithley was taking $75 pans out of a Cariboo creek that bears his name, François Lavieur and his compatriots were working the Barrière River, 65 kilometres north of Kamloops and making $50 per day. Gold was worth about $16 per ounce then, but with the present prices reaching 125 times that amount, it could make panning for the gold that Lavieur overlooked worthwhile.

It is the rainbow trout, rather than the

Gearing up for a fishing trip at the

gold at the end of the rainbow, that interests many of today’s vacationing travellers as the Barrière area offers ample fishing opportunities. Gravel roads lead east into the headwaters of the Barrière River and the North, East and South Barrière lakes. British Columbia recreational campsites are located at all three lakes and privately operated fishing camps are located on East and North Barrière Lakes.

The Yellowhead Highway crosses to the west side of the North Thompson, just north of Barrière. If you prefer to explore the backcountry, you could wind through town and follow Dunn Lake Road north to Little Fort or Clearwater along the east side of the North Thompson.

To the west of the town of Barrière lies the Bonaparte plateau with dozens of fine fishing lakes, several of which have public camping facilities.

Little Fort, 29 kilometres north of Barrière, is named so because it served as a Hudson’s Bay Company outpost for the fur trade from 1850 to 1852. It is the junction of Yellowhead Highway 5 and

98-kilometre-long Highway 24, linking the North Thompson Valley with the Cariboo Highway at 93 Mile House. It passes through a recreational area well worth visiting. Dozens of campsites and fishing camps located on cool, clear plateau lakes await those who are willing to venture off the main highways in the summer. In the winter, many of the same fishing camps open their lodges to crosscountry skiers, snowmobilers and icefishers. Lac des Roches and Bridge Lake are two of the larger lakes in the area, while Mahood Lake and the westernmost portion of Wells Gray Provincial Park are also accessible off Highway 24.

Little Fort is also the site of one of British Columbia’s few remaining currentpowered river ferries. The Little Fort ferry also operates from 7:00 am to 6:20 pm, serving the needs of local ranchers and providing access to some excellent fishing holes on the east side of the river.

Thirty kilometres north of Little Fort, the Yellowhead Highway 5 passes through the village of Clearwater. If you are looking for a break, there is a BC Parks campground near the North

Thompson River just south of Clearwater and a commercial campground at nearby Dutch Lake, just west of the main crossroads.

If you are interested in exploring the backroads, Clearwater River Road follows the Clearwater River upstream along the bottom of the canyon. Landslides have limited access, but if you don’t mind getting a bit damp, Interior Whitewater Expeditions offers a variety of trips on the Clearwater River.

At the time of writing, the only traffic circle on the Yellowhead Highway was at the north end of Clearwater. The road to the right heads to a school and shopping centre. Clearwater Valley Road heads left (north) to the main entrance of Wells Gray Provincial Park.

The Clearwater Visitor Centre, just north of the junction, is a good place to stop for maps and advice before heading into the wilderness. It is worth noting that the service stations near the junction are your last chances to fuel up.

Distance: 125 km

Duration: 1 Day

Off the Beaten

Track Rating:

Backroads Mapbook: Thompson Okanagan BC

Wells Gray Park is the ideal vacationland for the camper, hiker, backpacker and canoeist who wants to enjoy the wilderness atmosphere without chartering a safari to Africa or the Arctic tundra. Although there are fully serviced campsites, motels and hotels in and near Clearwater and along Clearwater Valley Road, a.k.a. Wells Gray Road, the BC Parks campsites in Wells Gray Park and North Thompson Park are not equipped with RV hookups. Instead, each unit has a parking spur, tenting space, fireplace and access to water, wood and a community outhouse. Reservations are accepted online for a number of the campsites.

BC Parks: bcparks.ca

BC Recreation Sites & Trails: sitesandtrailsbc.ca

Clearwater Lake Tours: clearwaterlaketours.com

Interior Whitewater Expeditions: interiorwhitewater.com

Wells Gray Park is truly a waterfall park. Helmcken Falls, which drops more than 140 metres in a single plunge, is the star attraction of the park. For diversity, the 541,500-hectare park also contains five major lakes; two large river systems; numerous small lakes, streams and waterways; plus a multitude of waterfalls, cataracts and rapids. It also contains young volcanic lava beds, unnamed glaciers and snow-capped mountain peaks, mineral springs and plenty of well-marked trails—used in the summer by hikers and in the winter by crosscountry skiers.

If you aren’t up to serious canoeing or kayaking, Clearwater Lake Tours offers boat tours on Clearwater and Azure lakes during the summer months. They have a base at the Clearwater Lake campsite, 68 kilometres north of Yellowhead Highway 5.

A point well worth mentioning is that the rivers of the area are wild and treacherous and are best observed from a firm footing on the shore. They have claimed many lives, as have the larger lakes, and should be treated with respect.

Get your copy of Road Trips 2024: Volume 6 from our online bookstore: thebookshack.ca

HOW OKANAGAN FARMERS ONCE HAD A REPUTATION AS LAWBREAKERS

BY DIANE SELKIRK

sign we’d reached the Okanagan was the lineup of roadside fruit stands clustered along Highway 3, just on the outskirts of Keremeos. These vibrant shops, offering a full range of fresh, dried, pickled and preserved vegetables and fruit, have long been considered a staple of this agricultural region. They seem so ubiquitous that they appear to have always been part of the rural landscape. However, a chance bit of reading had taught me otherwise. And a long weekend road trip to Penticton felt like the perfect time to share the little-known and somewhat nefarious history of the Okanagan Fruit Stand with my captive family.

BEFORE DIVING INTO the story, I thought we needed some sustenance. So, we pulled over at one of the colourfully decorated shops, this one adorned with a dozen or so paintings of giant fruit and bright displays of freshly picked produce. After a bit of contemplation, we selected a handful of plums and a basket of peaches (one of the crops that made the area famous). Settled back in the car, I take my first juicy bite. Savouring the flavour that only comes with the freshest fruit, I explained that just over 75 years ago, simply buying these roadside peaches would have fallen into a legal grey area. Neither selling nor buying them on the side of the road was completely legal.

The story of Okanagan holiday-makers turned degenerate fruitleggers dates back to the 1930s. This is when the region’s orchardists were struggling to get their produce to market. The solution turned out to be a mandatory system where farmers pooled all the fruit grown across the region’s rolling, lakeside farmlands and sold it through a marketing system called the British Columbia Fruit

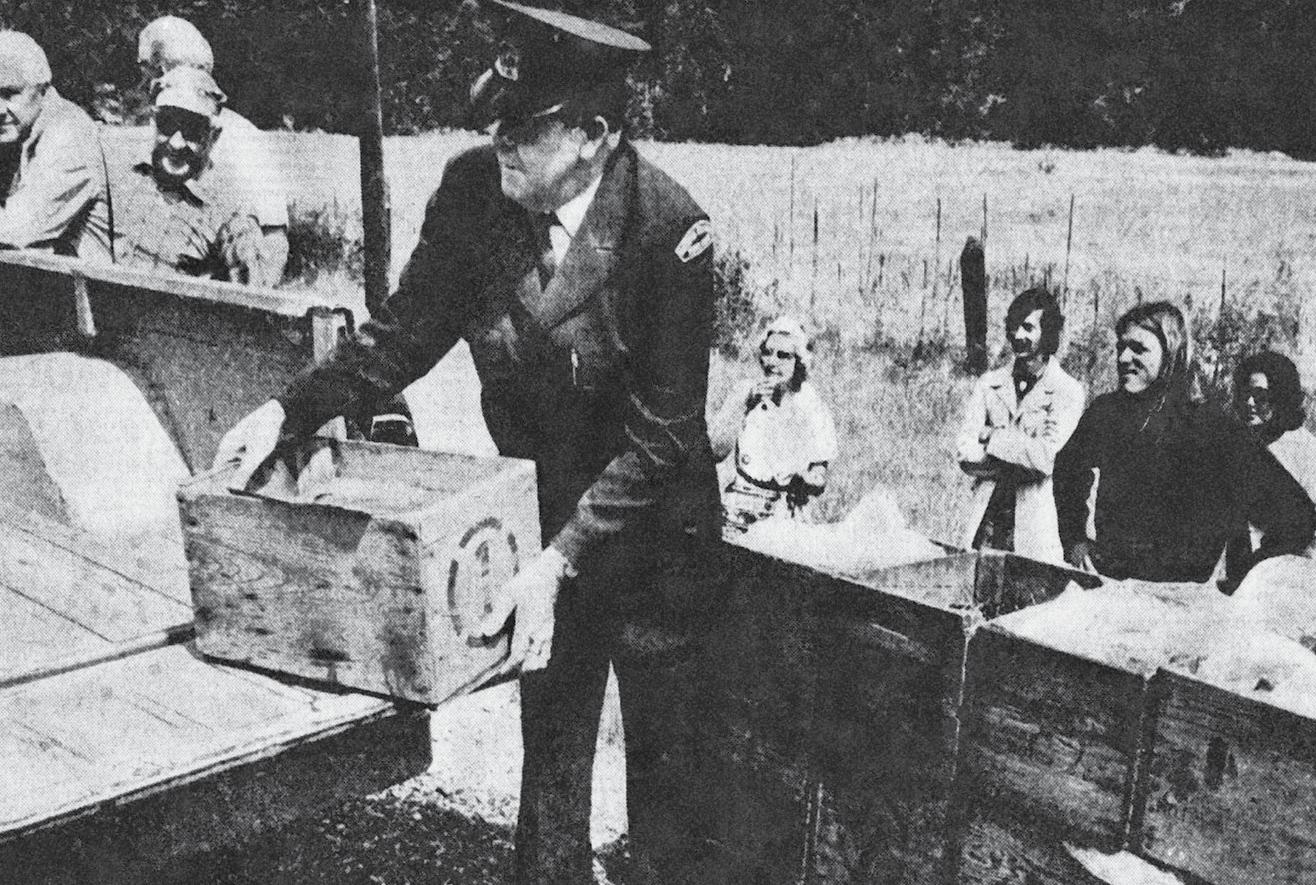

This looks like an innocent enough scene, but pre 1974, this would have been an illegal fruit stand, with violators facing fines and possibly jail time.

Board—a program not unlike the one dairy farmers use today. While the BC Fruit Board helped stabilize the market, not every farmer felt it was fair. So, when Highway 3 opened in late 1949, offering the first road link between Vancouver and the southern Interior, the first roadside fruit stands opened for cash sales— violating the rules of the Fruit Board.

As the landscape outside our window shifted from arid fields to abundant orchards, I told Maia and Evan that thanks to long-ago tourists like us, these illegal fruit stands quickly grew from a handful in 1949, to 200 in 1953, and to about 350 by 1957. Unable to keep up or control the growth, the Fruit Board added rules. You could buy fruit—but only

enough for personal consumption. So, in the mid-1950s, if we had loaded up the car with more than the regulated five boxes of fruit, we would have been considered not road trippers but smugglers, subject to fines or even jail time.

Peach, apple and cherry orchards (and more than a few vineyards) stretched ahead of us as my family reacted similar-

ly to those long-ago fruit buyers: by suggesting ways to hide excess fruit. Pretty soon, loading the kids, pets and luggage into the family car and heading to the lakes for Okanagan summer fun had become a popular summer ritual—and returning home with a car filled with illicit boxes of fruit was an important part of the tradition.

Luckily the days of fruit inspectors are long gone so we can all enjoy fresh produce, purchased directly from the farmer.

TURNING OFF OF Highway 3, we left the Similkameen Valley and headed north into Penticton. Set between the Okanagan and Skaha lakes, the area was once known a snpintktn by the syilx Okanagan people, a word that means, “A place where people have always been all year long.” Sunny and warm and fringed with gentle beaches, the area became filled with camp grounds, cozy hotels and kitschy (by modern standards) amusements. It was easy to see why the small town became so popular with families.

Checking into the Penticton Lakeside Resort, the three of us marveled at the sunset view of Okanagan Lake. The cloudless sky was tinged with pink, and the lake had turned a deep midnight blue. The hills appeared rusty and

“ The inspectors, known for their inconsistency and rudeness, would often seize excess fruit from unsuspecting tourists & destroy it.

parched from the summer heat, yet the vineyards on the Naramata Bench were lush and productive. Walking along the flower-lined boardwalk, we started looking for a place to have dinner.

Penticton retains much of the oldschool charm from its early days as a tourist hotspot. Yet, among the small-

town restaurants, there are also sophisticated dining options ranging from fine dining at the nearby Poplar Grove Winery, one of the original five wineries on the Naramata Bench, to Turkishinspired Elma, a bright, airy establishment featuring Turkish cuisine with an Okanagan twist.

The next morning, we headed to the Penticton Farmers’ Market—the perfect spot to pick up fresh baked goods for breakfast and dive back into the region’s fruit-filled history. Nowadays, some 80 vendors make, bake or grow items sold to the up to 8,000 visitors who stroll through the market on any given Saturday. As we admired heritage apples, sampled juicy plums and chatted with farmers, only a few could recall the days of the Fruit Board’s reign.

Diane SelkirkFILLING OUR SHOPPING bags, I realized the old rules would probably have excluded many of the boutique farmers whose diverse crops have become such an important part of the Okanagan’s flavour landscape. Initially, only farms fronting an arterial road could obtain a farm stand license—an option that also encouraged orchardists to grow a wider range of crops for their in-person sales. Farmers ineligible for roadside stands began to push back against this limitation. But it wasn’t until home canners also raised a fuss that the fruit limit was increased to 10 boxes (though only two boxes of cherries were allowed) and rules started to change regarding who could set up a farm stand.

With community members and fruit stand owners continuing to argue that allowing visitors to bring back fruit for friends and family could boost demand for BC orchard products, the limit was raised again to 20 boxes in 1960. However, this still didn’t stop the station wagon smugglers. So, the fruit board beefed up its force of inspectors, established a telephone tip line, and set up roadblocks and checkpoints on the highways leading out of the Okanagan.

AFTER OUR MORNING at the market, we had lunch at Bench 1775 on the Naramata Bench. Sampling the wines, one of the staff recalled that her father had once smuggled fruit out of the valley, dodging roadblocks and the highway-patrolling inspectors known for driving Volkswagen Bugs. It seems the appeal of buying fresh fruit directly from the farmer was something the Fruit Board hadn’t anticipated. But as we looked over the vines, sipping our favourite wines, I realized those long-ago fruit stands likely paved the way for this exact kind of farm-based agritourism. From the vineyard, we headed to the family-owned La Petite Abeille Cidery, where we toured the beautiful orchard and learned about the apple varieties from co-owner Kimberly Wish. After the tour, we found a shady spot on the cidery’s deck for some sampling. Overlooking the orchard and lake, I reflected on the role that fruitlegging must have

In

played in the development of highlights like this in the Okanagan.

Hiking, biking, paddling and dining are key to what makes a visit to the region special. But what I’ve grown to love about the area is that you can drive down almost any side road and discover another opportunity to visit a farm, vineyard or orchard, and meet the people who invest their hearts and souls into cultivating our food. And while the Fruit Board was initially established to support farmers and ensure their products reached our kitchens, they couldn’t have envisioned this more intimate future.

AS WE SET out on a lakeside drive, past stands leading to Summerland and Peachland, I shared with my family that it took an event known as the Fruit Wars to end the checkpoints, car chases, citizen-smugglers and occasional violence.

By 1970, farmers were frustrated with the stringent regulations and communities were concerned about the impact on tourism. The inspectors, known for their inconsistency and rudeness,

Dawson Falls, Wells Gray Park.

would often seize excess fruit from unsuspecting tourists and destroy it. Travel writers from the Vancouver Sun and Calgary Herald repeatedly warned potential Okanagan tourists about the risk of being “shaken down by the RCMP” for their fruit purchases.

So, on July 7, 1973, dozens of cherry farmers formed a large convoy and headed to what they advertised as a farmer’s market in Vancouver’s Gastown. Some drove straight through the checkpoints without stopping. Others stopped to collect fines, tickets and jail time—so they could contest them in court.

The battle lasted all summer, with outlaw convoys breaking through blockades to Calgary, Edmonton, Nanaimo and Prince George. “Vans and light cargo trucks could be found at viewpoints and picnic sites along major highways and in suburban parking lots and service stations, with hand-painted signs advertising Okanagan fruit for sale,” wrote Bradley and Hadlaw in a paper titled “Fruitleggers, Fruit Police and British Columbia’s Black Market.” By 1974, the Fruit Board relented,

"No we don't have 20 cases of fruit...

STAY

Penticton Lakeside Resort 21 Lakeshore Drive West pentictonlakesideresort.com

EAT

Elma 994 Lakeshore Drive West eatatelma.com

The Restaurant at Poplar Grove Winery 425 Middle Bench Road North poplargrove.ca

DO La Petite Abeille Cidery 1085 Fleet Rd Penticton lpacider.com

and the checkpoints were dismantled. It was no longer mandatory for commercial orchard fruit to be marketed through BC Tree Fruits—unless it was for export.

OUR FAMILY GETAWAY to Penticton ended too soon. After a final walk along the waterfront and a promise to do the Lake-to-Lake tube float on the canal running through town on our next visit, we packed up our produce, cider and wine.

We still had one last stop—I wanted to visit an old roadside fruit stand, one of the originals. Arriving at a stand piled high with fruit, we selected our boxes of peaches and plums. Waiting in line to pay, I tried to imagine a time when owning a fruit stand was an act of resistance—and shopping at one was a crime.

THE ALPINE CLUB of Canada is a venerable institution. Founded in 1906, it has grown to be the definitive association for those aspiring to climb sizeable mountains, with 24 regional sections spread across the country. While there are many excellent hiking and walking clubs in Canada, and many locally based rock climbing clubs, if you are serious about rock or ice climbing, or tackling big summits, the ACC is the place people gravitate toward. With its many alpine huts, its subsidized training programs and busy outdoor schedules, it’s where active and

motivated people meet.

Early on in the club’s history, the national office offered week long camps in the backcountry, usually in the Rockies, for members to attend. There, they would live under canvas and spend time socializing while being guided up surrounding summits by certified Canadian mountain guides. Over the ensuing century, those summer camps have been the source of many first ascents of unclimbed peaks, as well as the training ground for many famous mountaineers who later made history around the world.

Over the years, a number of the regional sections have copied the national model by hosting week long summer camps for their section members, as well as inviting neighbouring sections to attend, when spaces allowed.

And this is where our story starts. On this particular summer, our section (who will remain nameless, to protect

There, they would live under canvas while being guided up surrounding summits

the innocent) hosted a three week summer camp. As fate would have it, we were on the third week.

Being on the last week has its pluses and minuses. On the one hand, we benefit from flying into a camp that is already well established. On the other hand, it will be our job to close it down on the final Sunday morning, and leave the site so clean and reclaimed that others passing that way in years to come will never know that three different groups of 15 people have camped there.

THE WEEK BEGINS It’s late July and the time to prepare has arrived. It’s never easy packing for an alpine trip when the temperature on the coast is hovering close to 30°C and all you can think of are T-shirts and shorts. Somehow you

have to remember those cold times in the alpine, even in mid-summer. Fleece top, fleece pants, puffy jacket and, contrary to the past two months of blazing heat, a rain jacket.

We meet at the Pony Restaurant in Pemberton for a final meal, and to meet the new faces. Instead of the usual 15, we’re only 13 this week. Is that unlucky? We’re not a full complement, but that makes the helicopter weight issue less of a worry.

Then we’re off to the staging ground, a large open area in a forest previously used by log sorting equipment. We pitch tents, swat the few itinerant horseflies, and turn in, expectant as always of what tomorrow and the ensuing week will bring.

What it brings is a helicopter right on time, and a hail of flying bark chips and gravel. When the rotors cease to whirl, we emerge from behind the gear piles.

Jock has a brae Scots accent and will be our pilot today. The usual safety talk follows, before we pack what we can into the A-Star’s generous storage areas. Then four of us are off, rising up the valley in a spiraling arc as the blades sweep overhead and the treetops skim just out of reach below.

Why do pilots hug the slope like that?

Jock explains it’s a safety thing. Contrary to logic, being close to one valley side means that, if things suddenly go wrong, he has the full width of the valley in which to do something— such as aiming for a tree on the other side.

We burst over a rise before having time to think this through. Below are two orange domes next to a lake. The elevation is 6,400 feet (1,950 metres) on the helicopter’s altimeter. The domes will be our kitchen and mess tents for the week. A bunch of coloured ants are scurrying around, jumping on boxes to hold the

gear down. The dust cloud settles, the turbine eases and we step out into cool air and friendly handshakes. Week Two is all packed and ready to go home. The handover begins.

In an hour, the personnel exchange is over and silence returns to the alpine. A light wind disturbs the lake as we take stock of our surroundings. Sites are examined, sleeping tents are pitched and it’s time to take in some of the territory and put some of that rushed advice from Week Two into practice. We head through meadows of the upper valley, bound for the lake which, because it’s Sunday today, becomes known as Sunday Lake. All of us tag along, while we look up left and right at the steep slopes of heather and granite bluffs that hem us in.