Finding the right balance of editorial content is what makes putting this magazine together such a joy: Powerboats and sailboats, big boats and small boats, local anchorages and distant destinations. With so many types of boaters out there it’s a challenge to please everyone, but it’s a challenge we are happy to undertake.

During the Vancouver Boat Show we put up an ideas board where readers could share their thoughts with us. At the end of the show two of the comments were: “You should cover more local areas, not everyone is cruising to Alaska.” And, “You should write about more remote places, we’ve been to all the local destinations.” Since we heard both, I’d like to think we are at least close to striking that balance, but both are fair points. A lifelong Gulf Islands boater who’s looking to push a little further might be tired of reading about Montague Harbour, for instance. While a new boater who’s leaving the dock for the first time might get little value from reading about Calvert Island on the Central Coast. On the other hand, places are always changing, with new amenities like restaurants or rental shops, or changes to dock layouts or moorage rates. And even though that new boater might not be heading north this summer or next, there’s no reason not to plant the seed and start thinking about the possibilities. It’s always fun to dream. In this issue we have the best of both

worlds. Long-time PY contributor Deane Hislop, who’s cruised up and down the West Coast, has revisited some of his favourite Gulf Islands destinations in the beautiful Gulf Islands National Park Reserve (page 38). For novice boaters and old salts alike, these are must-visit destinations. We’ve included a handy graphic showing the number of mooring buoys at each location, as well as anchorage and dock availability.

We have also published a roundup of favourite anchorages near famed Johnstone Strait (page 26), including places to duck into if wind and waves start kicking up in the strait. Anne Vipond and Bill Kelly have written books on the area and their local knowledge is valuable for any boater heading north of Desolation Sound this summer.

Finally, I’ve been perusing charts of the West Coast for most of my life, from Puget Sound north to Alaska, and while I would never claim to know every island on the coast (especially the further north you go), I thought I was familiar with most of the Gulf Islands and San Juans. That said, I had never heard of, or even noticed, slender Spieden Island until Annie Means sent me a pitch for an article on the “Safari Island of the San Juans” (page 32). Unfortunately, Spieden is a private island, but the next time you find yourself cruising through the San Juans see if you can spot any wildlife roaming the shoreline—if you see anything, let us know.

Happy Cruising!

Sam Burkhart

DIRECTOR OF SALES Tyrone Stelzenmuller 604-620-0031 tyrones@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER (VAN. ISLE) Kathy Moore 250-748-6416 kathy@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER Meena Mann 604-559-9052 meena@pacificyachting.com

PUBLISHER / PRESIDENT Mark Yelic MARKETING MANAGER Desiree Miller GROUP CONTROLLER Anthea Williams

ACCOUNTING Elizabeth Williams

CONSUMER MARKETING Craig Sweetman CIRCULATION & CUSTOMER SERVICE

Roxanne Davies, Lauren Novak, Marissa Miller DIGITAL CONTENT COORDINATOR Mark Lapiy

SUBSCRIPTION

SUBSCRIBER

WE WELCOME YOUR LETTERS

Send your letter, along with your full name, and your boat’s name (if applicable), to editor@pacificyachting.com. Note that letters are selected and edited for brevity and clarity.

For over 50 years, a beautiful, sturdy 119-year-old boat named Four Winds and I have had many adventures on the high seas. Together, we discovered the underwater world of whales. These amazing and complex creatures have much to teach us mere mortals. In the early ‘70s, my team of researchers was one of the first to discover orcas in Robson Bight and communicate with them using modern sonic equipment and an almost mystic approach to the whales.

The ‘Project Apex’ crew are credited with being the first to create an interspecies ‘orcastra’ soundtrack coupled with film containing the first underwater footage of free orca. The film ‘Orca’ premiered at Vancouver’s Queen Elizabeth Theatre in 1973.

To my way of thinking, no one really owns a dog or a boat. We are merely caretakers. So, it was time to find a young mariner to take on the responsibility for this classic wooden vessel. Four Winds has changed hands from me to a young sailor who has taken up the challenge to maintain the legacy of this wonderful boat. I am teaching him everything I know about maintaining a vintage wooden sailing ship.

The first time my dog Rusty and I sailed Four Winds, her main and jib were hoisted as the best gusts of the day whistled over the Sooke Hills, stiffening her sails taking us forward with acceleration and speed, when from beneath the vessel a pod of orca

burst out of the water taking a position at the bow leading us onward into the wide-open Juan de Fuca Strait. I felt like our allies welcomed us to a new life at sea.

Last week, Dwight had his first sail aboard Four Winds. No sooner had he cleared Lund’s Finn Bay into the open water a pod of orca seemingly out of the blue surfaced right alongside just as he was reaching for his phone with me at the end of the line. What a good omen!

—Bruce BottI read with interest Kayleen VandeRee’s article in the May issue about her involvement with the underwater clean-up of Pendrell Sound. Here on Quadra Island, a small group of locals volunteer our time every Wednesday (or more frequently) from January till June when we will have bins from the Comox Valley Regional district waste management and also from Ocean Legacy Foundation. We survive with near zero funding and often spend our own money for vehicle and boat fuel. I know that the federal government has water lot leases in place for all aquaculture operations and marinas.

Why is there no ongoing annual inspections of these operations? The temptation to get rid of unwanted materials the easy way versus the right way, is often taken. Sometimes accidental, many times preventable.

This January I created an artistic display roughly based on Leonardo DaVinci’s last supper painting. Completely made from marine debris collected on Quadra Island’s beaches.

“The Final Supper” showcases some of the smaller pollution that comes to our shores.

Please view the Final Supper, on our Facebook page (Quadra Island Beach Clean Dream Team) or on YouTube @ quadrabeachclean

I hope that all boaters can help fight pollution wherever they find it, in BC’s waters and shores. Bring it out.

—Nevil and Heather Hand

Repair and Overhaul

• Awlgrip™ Refinishing • Fibreglass Repairs

• Hard Tops • Seasonal Maintenance

• Polishing and Detailing

Experts at gel coat colour matching and repair

Yacht Rigging

• Inspections • Work Aloft • Splicing and Swagging

• Custom Aluminium and Composite Spars • Installations • Architectural rigging • Deck Layout Metal Fabrication • Stainless and Aluminium • Arches • Radar Masts • Davits • Bow and Stern Rails • Bow Rollers • Bimini and Dodger frames • Custom fabrication for all your metal needs

07/2024

This is a local news-driven section. If something catches your attention that would be of interest to local boaters, send it along to editor@pacificyachting.com.

Do you know where this is?

Our monthly Geo Guesser feature continues to be popular among readers and last month may have been our most popular yet. Clearly, many of you have visited Pirates Cove on DeCourcy Island. After a random draw, we have selected Jenny Ferris as the winner of the June contest. This month’s location may be more of a challenge. Send your guesses to editor@pacificyaciting.com for your chance to win a PY drink koozie. Good luck!

At 31+ feet long and just under 10 feet at the beam, the Adventure is the biggest, toughest, most capable boat we’ve ever built. The 55° bow entry deadrise keeps you safe as you cut

Pacific Yachting’s annual photo contest is back! Don’t forget to get behind the lens this cruising season, and start submitting your best boating photos from 2024 for a chance to be featured in Pacific Yachting. Prizes will be announced in the next issue of Pacific Yachting! For contest rules and to enter, visit pacificyachting.com/photo-contest

Deadline: December 15

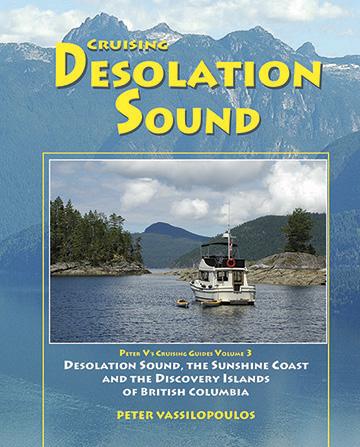

Guides’ New Revised Fifth Edition of The Gulf Islands and Vancouver Island

Volume I covers the Gulf Islands and Vancouver Island from Sooke and Victoria to Nanaimo. The Gulf Islands lie sheltered just off southeast Vancouver Island’s mountainous backbone. This closely connected group of islands border the southern Strait of Georgia, offering protected waters and one of the most temperate climates in Canada.

Visitors will be charmed by each island’s distinctive character and lured by clean, sandy beaches, cosy bays, hideaway anchorages and spectacular sunsets. In addition, the area’s marine parks are unique

to British Columbia’s coast and often only accessible by water. Most of the Gulf Islands offer full-service marinas and boating facilities while managing to retain their relaxed charm.

With over 100 hand-drawn charts and up-to-date information alongside stunning colour photographs, this completely revised edition provides detailed knowledge of each anchorage and marina, including the latest advice about fuel docks and available services, as well as marine parks to explore and much more.

Call

The summer is in full swing, but it’s not too early to start submitting content for PY’s annual Summer Cruising Roundup. Our roundup of summer boat gatherings will be published in the December issue and we’d love to hear how you and your friends made the most of the cruising season. Information on rendezvous and boat meetups, along with photos can be sent to editor@pacificyachting.com

Deadline: October 15

BOOKS

BOOKS

The popular folk meaning for posh claims it is an acronym for port out, starboard home, describing the cooler cabins taken by most rich passengers travelling from Britain to India and back.

Perhaps this is legend, but there’s no denying posh is used to describe a person who fits in or behaves as if they belong to the upper classes.

A fresh start from England’s stifling class system is what 20-year-old shop girl and war bride Molly desires, when she marries the dashing, but flawed Canadian Sargeant, Mike Stanford.

Molly was one of the 48,000 Canadian war brides who traded a Europe of rationing and bombing for a better life in Canada. Or at least that is what she hoped for. What Molly got is a fisherman husband with a murky past who takes her to the remote West Coast village of Bamfield.

Imagine if you will, English writer Jane Austen and Canadian writer and environmentalist Farly Mowatt collaborating on a story, with a dash of sexual sizzle provided by Fear of Fly-

ing author Erica Jong. There was fear in the Bamfield of 1944, where nightly blackouts hid the West Coast town from possible bombing raids.

As writer Druehl writes, “It’s incredible how a tiny village of less than 200 can be so complex, so web-like, that everything impacts so many others.”

Sailors, fishers, telegraph operators, displaced persons, hippies, Indigenous people, and a few sexy neighbours make up the cast of characters. The ebb and flow of life mirrors the inexorable tide that touches the shores of Bamfield before a 1963 road would connect it to the rest of the world.

Although the narrative sometimes stretches credulity, even for fiction, the story chugs away like a sturdy, reliable fishing boat that plies the coastal inlets of this sleepy backwater.

Author Druehl has been a Bamfield resident since the 1960s. He is Professor Emeritus at Simon Fraser University and an expert in kelp species. This story evolved after many chats with his neighbour Eileen Scott who experienced the London Blitz.

A rollicking good yarn, perfect for reading while waiting for a ferry.

—RM Davies

Sidney, BC | 250-656-2639

Verado

expectations of what high-horsepower to life with impressively responsive sensational top speeds. Exceptionally deliver an unrivaled driving experience

What if every journey began with the push of a button? Where would you go? With the Mercury Avator 7.5e electric outboard, all you need is a destination. Its portable design and quick-connect battery will have you ready for the water, no matter where adventure takes you. Avator is intelligent, all-electric propulsion, designed to make exploring effortless.

Let your journey begin with Mercury Avator.

exploring. So are you. Go Boldly.

Jon Taylor, a retired fisherman who’s resided in Sointula on Malcolm Island since 1976, is a poet, musician and a keen observer of humanity. For him, the island is home despite its never-ending rain and dampness, because, he writes, “If the island wants you, it gets you.” In this humorous collection of tales and reminiscences, Taylor explains “the island” is made of sand and gravel dumped by a glacier, lacks good harbours or fertile soil and that its

residents have survived for decades by fishing, logging and drinking. The Kwakwaka’wakw used it for its resources. The island was named for Sir Pulteney Malcolm, another British admiral who never sailed in BC. A group of socialist-minded Finns arrived in the early 20th century to establish an ideal commune where full equality would reign. They founded a small town, “Sointula,” Finnish for a “Place of Harmony.” The sense of unity didn’t exactly pan out, but Taylor writes, for

those who remained, the island “seems to inspire stubbornness and give rise to abnormal levels of individuality.”

The stories introduce us to his fellow Malcolmites and his eclectic, sometimes bizarre, colleagues in the fishing industry. His descriptions of fishermen, their fondness of booze, their competition to get to the right fishing spots for the “big set” even if it means entangling their gear with that of other boats, are hilarious, and carry a good dose of truth. His tales also reveal that more recent environmental rules about the disposal of fossil fuels and waste into the sea were sorely needed.

When Taylor arrived in Sointula at age 32, he had sailing and boating experience but had never fished commercially. He put up a sign “wants to crew” and got hired on a seine boat because he could cook. Subsequently, he worked on a variety of boats, including seiners, gillnetters and trollers, eventually owning his own troller.

He displays a mordant wit when describing how a “done-for” but wily old logger managed to get his derelict, filthy floating camp/home towed to Port Hardy, landing it on the beach. While visiting the welfare people, he declared vigorously he’d never go to an old-folks home, hoping his intransigence would goad the bureaucracy to force him into one. It went exactly as he’d planned.

Taylor graphically describes a sexcrazed fisherman, how a telephone repairman climbed a pole to spy on topless women, how the slime on fish waterproofs them and sticks to everything on a boat like crazy glue. As do fish scales.

This is a delightful book you can read in an afternoon or savour one story at a time before you fall into the arms of Morpheus. It makes you wish for more such tales.

—Marianne Scott

anmar Marine International (YMI) has announced a new strategic partnership with Aspen Power Catamarans which will see Yanmar’s engine fitted on board Aspen’s C100 model.

The collaboration introduces the Yanmar 4LV250 engine to Aspen’s C100 which boasts remarkable improvements, achieving 4.1 mpg at 18 mph—a 32 percent increase in efficiency. Notably, the Yanmar engine is

Peter Chance.

praised for its solid diesel engineering, lightweight build, smooth operation, and quiet performance.

Aspen Power Catamarans, founded in 2008, is renowned for its innovative approach to power catamaran design. With a commitment to excellence and a passion for pushing boundaries, Aspen delivers power catamarans that redefine efficiency, performance, and comfort on the water. aspenpowercatamarans.com

ANCHOR MARINE

Victoria, BC 250-386-8375

COMAR ELECTRIC SERVICES LTD Port Coquitlam, BC 604-941-7646

ELMAR MARINE ELECTRONICS North Vancouver, BC 604-986-5582

GLOBAL MARINE EQUIPMENT Richmond, BC 604-718-2722

MACKAY MARINE Burnaby, BC 604-435-1455

OCEAN PACIFIC MARINE SUPPLY Campbell River, BC 250-286-1011

PRIME YACHT SYSTEMS INC Victoria, BC 250-896-2971

RADIO HOLLAND Vancouver, BC 604-293-2900

REEDEL MARINE SERVICES Parksville, BC 250-248-2555

ROTON INDUSTRIES Vancouver, BC 604-688-2325

SEACOAST MARINE ELECTRONICS LTD Vancouver, BC 604-323-0623

STRYKER ELECTRONICS Port Hardy, BC 250-949-8022

WESTERN MARINE CO Vancouver, BC 604-253-3322

ZULU ELECTRIC Richmond, BC 604-285-5466

You want easy?

You want AI Routing! Let TZ MAPS with AI Routing make route planning a snap. Don’t take our word for it. Scan here to see for yourself how easy it is!

Concord Green Energy, along with lead sponsors RBC and TELUS, has unveiled the Concord Pacific Racing squad for Canada’s first-ever campaign at the historic Women’s America’s Cup and Youth America’s Cup, set to take place in Barcelona later this year.

Supported by official sponsor Dilawri Group and the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club, the Concord Pacific Racing squad features top talent from across Canada including decorated Olympians and SailGP athletes.

The team has now relocated to Barcelona, immersing themselves in the local sailing scene, acclimatising to the

challenging conditions and surveying the race course in preparation for the upcoming regattas.

The Youth regatta starts in Barcelona on September 17 with the final scheduled for September 26. The Women’s regatta starts racing on October 5 with the final to be staged amid the AC75 America’s Cup racing program on October 13.

The two Canadian teams will compete against Spain, New Zealand, Australia, the UK, Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, USA and France. You can follow all the action of Concord Pacific Racing on Instagram or at concordpacificracing.com.

Isabella Bertold (Royal Vancouver Yacht Club, Captain)

Ali Ten Hove (Kingston Yacht Club)

Maggie Drinkwater (Royal Vancouver Yacht Club)

Mariah Millen (Royal Canadian Yacht Club)

Maura Dewey (Royal Victoria Yacht Club)

Andrew Wood (Royal Vancouver Yacht Club, Captain)

Andre Van Dam (Royal Vancouver Yacht Club)

Jack Gogan (Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Club / Northern Yacht Club)

Galen Richardson (Royal Canadian Yacht Club)

Georgia Lewin-LaFrance (Chester Yacht Club / Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron)

September 28 to October 5

The event’s debut in the Pacific Northwest will pair world class racing with one of the most unique and popular sailing venues in North America. In addition to racing, the event will include a number of Northwest themed Australia, and Asia in addition to the

quarters,

II have friends who live full-time on a powerless junk with kerosene stove and lamps—no motor, no electricity and no fridge. They sail it on and off the mooring and eat what’s in season (Christmas dinner was oysters). They buy beer and wine, but they make their own bread from flour they grind on board with a hand-cranked grinder (whole grains keep better than flour). They even have a barbecue that burns

driftwood. And every morning they both row ashore to go to work.

This is sailing at its most basic, and they don’t do it just for day tripping— they’ve been around Vancouver Island twice. It may sound pretty grim to anybody with even a minimally equipped boat, but they enjoy it. And, surprisingly, they eat well. He says that good bread and salt pork used to be enough for any non-deep sea trip. Which makes sense. It was enough for the Vikings and the Portuguese, the Basques and the Bretons, and all those early chartless adventuring sailors, some of whose recipes still survive in much of their original form. Think of chowder, pork and clam stew, even the Japanese nabeyaki udon. They’re all basically the same—meat, fish, starch

and water, and if you can cook one, you can cook all the others. North Americans have decided that chowder means clams. Fresh clams are great if you can find them, but canned work well. So do mussels and cubes of frozen fish. Most chowder recipes call for potatoes, but if you haven’t got them, cubes of stale fried bread are fine. That’s the starch. Not many of us pack salt pork around, so use bacon. That’s the meat. Some put tomatoes in chowder, some don’t. Some finish it off with cream, some don’t. The Portuguese put olives in their fish stews, as do Italians. The Japanese and Chinese add ginger, noodles and seaweed. The Spanish and Hungarians use paprika, the French use butter. All use onions and garlic. A good fish stew recipe

is infinitely variable. Just remember the word “chowder” comes from the Breton chaudiere, which means cooking pot.

•4 slices side bacon cut into thin strips

•1 large potato, diced or a slice of stale bread, cubed

•1 cup water or beer

•1 can clams or frozen or fresh fish

•1 onion, sliced thin

•1 clove garlic, peeled and chopped

•2 tbsp water

•1 tbsp olive oil

1. Put four slices of bacon in a saucepan over medium heat and cook three minutes until it crisps a bit. Add the onion, garlic, two tablespoons of water and olive oil. Cook, stirring continuously, until the water disappears and the onion is limp.

2. Stir in either the potato or bread, and a cup of water or beer. Cover and cook five minutes. This is where you can start to improvise by adding just about anything, as well as enough extra liquid to make it a soup. Rest assured that whatever you or the kids suggest (except for maybe Smarties), it will taste wonderful. Stalks of thin-sliced celery are good; so are diced carrots. Canned tomatoes, chopped red peppers or sliced mushrooms are nice. Also try tomato paste or any of the aforementioned national flavourings. Use lots of pepper, and dill if you’ve got it (you can also use thyme or rosemary). Restaurants stretch and enrich their chowders with chicken stock cubes, and so can you.

3. Now add either a can of clams or some frozen or fresh fish (cubed), or chopped weiners, thin-sliced salami, even cubes of leftover cooked pork or cold chicken. Cook five minutes, taste for salt and eat. Your saucepan or frypan has become a chaudiere. It should be different each and every time. Like the weather and making love.

BY LIZA COPELAND

BY LIZA COPELAND

LLike many words in the English language the word ‘knot’ has multiple meanings. The Merriam Webster dictionary lists eight, of which two are commonly used in the nautical domain. We are all familiar with the tying of a line into a specialised knot every time we go boating, whether attaching the boat to the dock or connecting two lines together, and we are also aware of the importance of using the right kind of knot for safety and security. The second ‘knot’ we use, that relates to speed, appears to be more of an unknown, although marine weather charts show wind strength in knots, and boat speed and currents are also measured in knots. What actually is this knot and what is its significance in marine and air navigation?

THE ORIGINS OF a knot that measures speed dates back to the 17th century, when sailors measured the speed of their ships with the use of a device called a “common log.” This was a coil of rope with uniformly spaced knots attached to a piece of wood shaped like a slice of pie. The line was allowed to pay out freely from the coil at the back of the boat for a specific amount of time. When the specified time had passed, the line was pulled in and

A chip log, also called common log, or ship log, is a navigation tool used by mariners to estimate the speed of a vessel through water. The name of the unit knot, for nautical mile per hour, was derived from this method of measurement. A chip log consists of a wooden board attached to a line (the log-line). The log-line has a number of knots tied in it at uniform spacings. The log-line is wound on a reel to allow it to be paid out easily. Originally, the distance between marks was seven fathoms or 42 feet used with a sandglass with a 30 second running time. Later refinements in the length of the nautical mile caused the distance between knots to be changed. Eventually, the distance was set to 47 feet, three inches for a standard glass of 28 seconds.

the number of knots on the rope between the ship and the wood were counted. The speed of the ship was reckoned to be the number of knots counted (i.e. distance sailed) during the specified time.

Eventually these knots were standardized using nautical miles with one knot of speed equaling one nautical mile an hour. The nautical mile (NM) was officially set at exactly 1.852 kilometres (1.1508 statute miles) in 1929 by what is now known as the International Hydrographic Organization. The US adopted the international nautical mile in 1954 and the UK in 1970. The internationally recognized symbol for knot by the ISO and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers is kn.

The reason for this particular standard is its relationship to earth’s longitude and latitude coordinates, with one nautical mile equaling one minute of latitude. One minute is equal to 1/60th of a degree. The distance from the equator to the pole is 90 degrees latitude, which is the same as 60x90 = 5,400 minutes = 5,400 NM. So, calculating a route using a lati-

Sailing instriments have enabled the modern sailor to have more information at their fingertips. At a glance, this unit is showing BSPD (boat speed), TWD (true wind direction, TWS (true wind speed) and TWA (true wind angle).

tude and longitude position is easier and more practical for long-distance travel where the curvature of the earth becomes a factor in accurate measurement and as nautical charts use latitude and longitude. That this unit is

standardized internationally is also a benefit. With boat speed calculated in knots it became the custom to also measure wind strength and current speed in knots.

Although there were aids to calculating one’s position such as RDF and Loran (that used radio waves and frequencies), as well as radar and early satellite Satnav (when you were lucky to achieve a good fix), until the early 1990s and the introduction of GPS, mariners mostly relied on dead reckoning (DR). This is the process of calculating one’s present DR position from a previously determined position by using estimates of one’s speed, elapsed time, (an accurate time piece is essential) and heading (direction or course). Instruments with a trip log make DR calculations quicker by providing the first two requirements, with distance equaling speed and time. Set and drift, the currents direction and speed, and leeway from sideways drift caused by the wind are also taken into consideration.

TODAY, THERE ARE ever more sophisticated instruments that give us increased information. We have the knotmeter and knotlog records for speed; wind instruments that give true and apparent wind and are fine tuned for shifts and close-hauled sailing; depth units for piloting and anchoring, (with fish finders showing the composition of the ocean floor), along with water temperature that is useful for anglers and divers. These come as stand alone, as systems with identical displays or in multifunction units. They also come in a variety of sizes to suit placement on the boat and can be wired or wireless and may still need a transducer through the hull.

Since the early ‘90s when GPS had not only been released for civilian use but had become more affordable, the world changed for cruisers. (Note: when we installed our first GPS in late 1990 it still was not available 24 hours a day). Now we knew where we were, could plan in advance of landfall and could measure our speed in a different way, by speed over ground (SOG), which unlike an impeller log, which is speed through the water, is unaffected by other conditions. By comparing logged speed and SOG, current can be calculated. GPS instruments can show your velocity made good (VMG), i.e. your true speed toward a waypoint. If you’re heading directly at the destination, your SOG and VMG will match, but when traveling off-course your VMG will be lower. Although useful for all boaters it is especially useful for sailors going upwind. Maybe you can point a little lower, but travel through the water faster, and increase your VMG and comfort. Overlaying radar on GPS charts raises the level of information further.

WE ARE INCREDIBLY fortunate today in that one of the biggest hurdles to cruising, knowing where we are and the hazards ahead of us has been vir-

tually solved with not only detailed charts for most of the world, but also visually knowing where we are in relation to them. There are two caveats, the first is that the GPS may be more accurate than the charted positions, and secondly that electronics can fail, especially in a marine environment, and one should always be able to return to basics.

During our early ocean passages in the ‘80s, before GPS, we always plotted our DR position on paper charts and wrote in the logbook hourly taking any pertinent conditions of drift and leeway into consideration. If we hadn’t had any fixes from the Satnav for several days, in good weather the sextant would be brought out for confirmation. Generally, our DR calculations worked well for the next landfall. We also tried to arrive during daylight hours, had a searchlight at hand if not, and if there was any confusion, the hand bearing compass was put to good use to establish our actual position before entering the wrong bay!

Note: Pacific Yachting has always used the term “miles” when referring to nautical miles. You will not see the term nautical miles in the magazine. We use kilometres when referring to distances on land.

Liza Copeland is the author of three successful cruising narratives and a how-to text with husband Andy. She writes for a variety of magazines and gives cruising and travel talks worldwide. See her website aboutcruising.com

Revisiting our favourite places to drop the hook

By Anne Vipond & William Kelly

BBoaters seeking shelter near Johnstone Strait soon learn to choose their anchorages carefully. Summer northwesterlies can blow strongly in the strait, sometimes reaching gale force strength. These winds funnel the length of this 54-mile-long channel and seek out even the most protected anchorages. But there are a few sheltered places, and at the east end of Johnstone Strait, where it connects with Discovery Passage, there is a road less travelled leading to one of our favourite anchorages. Read on to discover.

Of all the forest-fringed anchorages lying north of Desolation Sound, the one we most often visit is Handfield Bay on Sonora Island. And each time we approach this anchorage along Nodales Channel, the sight of distant Estero Peak rising above forested mountainsides is a welcome and timeless greeting.

The first time we pulled into Handfield Bay, which lies on the north side of Cameleon Harbour and is part of Thurston Bay Marine Park, it was a warm June day back in the 1980s. This was the furthest north we had then been in our boat and we were slightly disappointed to find several other boats already there. Two rafted sailboats were anchored off the east side of the large islet, called Tully Island, their occupants enjoying happy hour in the cockpit. Further into the anchorage was an old wooden sloop anchored close to the smaller islet where an elderly man was hanging laundry on a line strung between two trees.

We dropped anchor near the bay’s head, aware we would have barely enough depth under our keel at low water, and sat down to supper in the cockpit. Halfway through our meal,

the man we had spotted on the islet came rowing toward us in a large fisherman’s dinghy, the kind in which the oarsman stands up and faces the bow while pushing on the oars.

“Evening, folks,” he said cheerfully as he drew close. “You know, you’re sitting in pretty shallow water that’s going to get more shallow.” He pointed to the small islet behind us and suggested we’d be more comfortable anchored closer to it, where the water was deeper.

His name was Don Godkin and he was a wealth of local knowledge, having once homesteaded on the south shore of the harbour. After discussing our various anchoring options with Don, we raised anchor and under his watchful eye we re-anchored off the north side of the small islet and tied a stern line to shore. He nodded his ap -

proval from the deck of his sloop and we all slept soundly that night.

The next morning, Anne rowed our Scottish terrier ashore, landing the dinghy on Tully Island. As Tuck scampered through the tall grass, past clusters of pink-blossomed nodding onion, the morning peacefulness of the anchorage was suddenly shattered by the hair-raising squeals of two terriers exchanging opinions. A cairn terrier off one of the rafted sailboats had also arrived for her morning walk and she was giving our Scottie, 10 years her junior, a piece of her mind. A more friendly exchange took place between Anne and the other dog owner, who also proved to be a wealth of local knowledge. Fred lived on Quadra Island and said he had been concerned about where we first dropped anchor the previous afternoon until he saw

Don row over to us. It seemed everyone knew each other around here. When we departed Handfield Bay, waving farewell to Don, we never expected to see any of these people again. Yet, when we returned a few years later, there was Fred’s sailboat once again anchored near Tully Island. Chance encounters with other boaters can quickly blossom into friendships and by sundown that day we had become friends with Fred and his wife Rita, staying in touch for years afterward.

On hot summer days, when Handfield Bay is a millpond, the water is warm enough for swimming. However, the inner part of the bay is not a good place to be if a strong northwesterly is blowing and gusts are blasting through the anchorage. That’s when we stay outside the entrance to the inner bay and drop anchor south of Tully Island in the lee of Bruce Peninsula.

When we raise anchor and leave Handfield Bay, the conditions in Johnstone Strait will determine our next destination. And it doesn’t take long to find out what those conditions are once we’ve sailed past the lighthouse at Chatham Point to begin our transit of the strait. If a brisk westerly is blowing against an ebb current, the seas will be choppy off the Walkem Islands. This is where we have decided more than once to turn off the strait into the calmer waters of Mayne Passage. This passage leads to Cordero Channel and the ‘back route’ of passes. It also runs past the Blind Channel Resort on West Thurlow Island and, much as we enjoy anchoring, this is a resort we often stopped at.

The once-bustling site of a shingle mill and cannery, Blind Channel had been reduced to a few tumbledown shacks when Edgar and Annemarie

Richter motored up to the small fuel dock in the summer of 1969 and noticed the “For Sale” sign. They were cruising with their children in a 30-foot boat Edgar had built after emigrating from Germany to start a new life in Canada. Settling in Vancouver to be close to the fjords that had drawn them to the West Coast, the Richter family made another big move when they sold their suburban home and moved to Blind Channel. Years of hard work followed, in which they transformed the derelict settlement into a thriving marine resort. Edgar designed and built everything, and Annemarie provided the decorative touches with her colourful artwork.

Over the years we got to know Edgar and Annemarie, always enjoying our

visits to their resort and the long chats we shared in the comfort of their airy restaurant overlooking the floats. But it wasn’t just their warm hospitality that prompted us to pull into Blind Channel on a regular basis. Adjacent to the resort property is a network of hiking trails, first developed in 1988 when the forestry company that owned the tree-farm licence on West Thurlow Island was encouraged by the Richters to create a buffer strip between its logging operations and the resort. Since then, many a visiting boater has enjoyed hiking these beautiful interconnecting trails beneath the calmness of a forest canopy.

If you prefer to anchor, there is a decent anchorage opposite Blind Channel in Charles Bay. We have anchored north of Eclipse Islet in soft mud in two fathoms.

Leaving Blind Channel, we often proceed north along the back channels leading to Forward Harbour, especially if there’s a strong headwind to be avoided in Johnstone Strait. This is a large harbour with a distinctive, snowcapped peak rising above the other mainland mountains stretching across the inlet’s eastern horizon. It’s possible

to anchor almost anywhere in Forward Harbour, but the Douglas Bay anchorage—nestled along the harbour’s west shore—provides the best shelter from westerlies. There seems to be a constant circular slow-moving current in the bay, so we give ourselves lots of room from other boats.

A clean pebble beach borders the anchorage and a forest trail meanders across a neck of land to Bessborough Bay on the other side of Thynne Peninsula. The first time we anchored in Douglas Bay on a calm summer’s day, a woman on another boat caused a dinner-hour stir in the anchorage when

she shouted to everyone that there was a bear on shore. We were relaxing in our cockpit at the time, enjoying a glass of wine, when we turned to look. But we were too late, for the embarrassed bear had already slipped back into the forest.

Black bears are common at many northern anchorages, as is the sight of boaters hurrying to their beached dinghies and frantically pushing off from shore after spotting a black bear at the forest’s edge.

When our 14-year-old son took his terrier ashore at the anchorage in Port

Neville, he wondered why his normally energetic dog didn’t want to scamper along the foreshore. John tried to coax her out of the dinghy, but she refused to budge. It wasn’t until John was pulling away from shore that a black bear emerged from the woods and he then realized a dog’s sense of smell should never be questioned.

The anchorage lying along the west side of the inlet is encumbered with kelp and current, but the holding ground is good. From here you can watch the flow of commercial vessels in Johnstone Strait, including passing cruise ships.

On the opposite shore is the Port Neville public float. This historic settlement was once a bustling community centre for the inlet’s loggers and farmers, but its heyday was long over by the time we began stopping here. During fishery openings the dock would fill at night with commercial fishing boats rafted two or three abreast, but more often we shared dock space with fellow pleasure boaters.

It was at Port Neville that we met up again with Don Godkin, his sloop

tied to a private float beside the main dock. He invited us aboard to view various beachcombing items he had collected over the years. The cabin was lined with wooden shelves packed with odds and ends, including plants growing from coffee tins, and his clothesline was strung on deck with socks and rags hung out to dry. Don brewed us some herbal tea and shared his thoughts on city folk. He wondered why we seem to be in such a hurry, arriving late in the day at an anchorage, then leaving first thing the next morning without having a good look around.

Since then, we have spent time in many a forest-fringed northern anchorage, listening to the sounds of nature, and felt like we were occupying the most beautiful spot on Earth. Don was right—we should linger at places of beauty, and the BC Coast has many. As the poet John Clare observed about the rolling hills near Cambridge, whoever looks round sees eternity there.

WWhen people think of San Juan Island boating, the phrases, “exotic game hunt,” “Safari,” and “John Wayne” aren’t typical word associations. At first glance, such unlikely imagery would seem to be an odd fit in Washington State’s most beloved cruising grounds.

Yet, one of the great beauties of voyaging in the Pacific Northwest is that nearly every island and every gunkhole is laden with some tidbit of strange and engaging history. Spieden Island, formerly referred to as the “Safari Island of the San Juans,” is one such example.

Staring out through the rims of my well-worn binoculars, the inkydark eyes of a Japanese Sika deer gaze back at me. I’m just north of San Juan Island’s Roche Harbor, bobbing at sea as I peer at the southern shore of Spieden Island. Amidst the isle’s swaying verdant slopes stands a mismatched assembly of foreign ungulates.

The herd resembles something akin to the eccentric friend group from The Breakfast Club. Big horned Sheep from the Middle East graze alongside Fallow deer from Europe. Japanese Sika schmooze amongst them, nipping at local vegetation.

This seemingly random cast of characters hails from a bygone era when Spieden Island was once more robustly stocked as a private hunting park.

While the animal rights movement was kicking off broadly in the 1970s and 1980s, Spieden’s “Safari Island” marched to the beat of a different drum. Rumors about the isolated rock abound. Giraffes

and rhinos could once be seen walking the shores. Big executives could pay to fly in, make a trophy of an exotic beast, and then fly out all within a weekend. John Wayne, himself a lover of Pacific Northwest cruising, was rumored to have hunted there, though whether he did so in his iconic cowboy hat, none can say.

Because Spieden Island has always been notoriously private, and still is today—it’s currently owned by the cofounder of Oakley Sunglasses—it’s difficult to substantiate much of the lore surrounding the 516-acre landmass.

What we can say for sure, however, is that archival stories from a local periodical, the Anacortes American, report that the island was purchased in 1969 by a Seattle-based taxidermy and game guide service. The Waggoner Cruising Guide names this group as The Spie-

den Development Corporation, now defunct.

And, like any elite hunting experience, the isle likewise required posh accommodation. In an effort to reproduce an African game hunting experience, visiting guests were hosted in a lodge complete with an impressive fireplace and swimming pool. After all, while stalking prey, the hunters may have even had to walk the entirety of the three-mileby-one-mile island. Surely, such extensive exertion would require a cold gin and tonic and a dip in the pool.

Though rumors of big exotic game may seem fantastical, those legends may not actually be so far-fetched. A 1976 edition of the Anacortes American claims that the island wasn’t just filled with exotic deer and fowl, but with much larger and more dangerous beasts. The periodical recounts the

As you cruise by Spieden Island, train your binoculars on shore. You never know what you might see.

story of a local Anacortes man who described how he was hired to transport both a leopard and a group of apes to the island.

The paper reads, “Del Kahn said he helped unload a leopard, which was to be kept in an enclosure near the lodge, and a group of large apes, which were turned loose in the open.” Despite such impressive prey, the game farm wasn’t all that successful. Part of the reason why this Safari Island was so short-lived is that there really wasn’t much sport in it. Anyone sailing past the stretched shores of Spieden Island can plainly see that there are few places for wildlife to hide from a hunter’s prying eyes or bullets. The southern part of the island is a large, exposed grassy knoll, while a thin strip of evergreen forest covers the northern portion of the rock. Surrounding the island sits Spieden

EXPLORING LIBERTY

Epitomizing the spirit of adventure and discovery, the Azimut Magellano Series is a timeless yet modern-day milestone of innovation conceived for long cruises. As the first nautical crossover ever designed, it offers true sea connoisseurs safe and tranquil journeys limiting fuel consumption combined with abundant storage space for extended stays on board in full comfort.

AZIMUT. DARE TO AMAZE.

OFFICIAL DEALERS

USA: Alexander Marine USA, alexandermarineusa.com

Canada: Fraser Yacht Sales, fraseryachtsales.com

Channel, where tides have been known to rip, making it a challenge for prey to swim to safety.

All of these factors make for a lackluster chase. Hunting, it turns out, is a lot less fun when the animals you’re stalking have nowhere to run. Local San Juan residents also reported complaints about stray bullets reaching their island to the south. Maybe those elite hunters weren’t so elite after all.

In November of 1970, to further sour public opinion of Safari Island, CBS Evening News Anchor Walter Cronkite aired a less than flattering report on the Spieden Development Corporation’s day-to-day operations. Three Washington state legislators were so moved by the piece that they filed a bill to end the hunting of captive animals, largely in an effort to stifle Safari Island’s business model. And so, amidst bad press

and poor hunting, the Safari Island of the San Juans shut down a little less than a year after it was opened. In the nearly 55 years since its big game days, Spieden Island has changed hands several times. The big animals have been sold off, and the isle remains isolated. In 2024, all that lingers of the Icarian game farm are the foreign four-legged misfits that greet passing boaters.

These days, the only shooting that takes place near the isle comes from a camera lens. Though you can’t step ashore as the island is privately held, you can still participate in a safari of your own, from behind your personal set of well-worn binoculars. Next time you pass by, join in, look up, and wave hello to the living antiques from one of the strangest bits of San Juan history.

Nearest Marina: Roche Harbor Resort San Juan Island rocheharbor.com marina@rocheharbor.com

WANDERING THROUGH THE MOSAIC OF LANDS, WATER AND HISTORY

BY DEANE HISLOP

TThe summer sun is beating down on a deliriously lovely tongue of white sand making it warm as it massages our bare feet. My wife and I are walking a onemile-long, half-moon shaped beach, the turquoise waters rolling ashore at a relaxing rhythm. It is easy to imagine Arlene and I are visiting an atoll somewhere in the South Pacific, but no. We are strolling along Sidney Spit in the Gulf Islands. The spit is one of many

parcels that make up the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve in the heart of the Salish Sea.

This magnificent park reserve with its plentiful wildlife, scenic views and historic sites is in the Southern Gulf Islands—a popular area for both Canadian and American boaters—and during our last cruise through the islands we visited many of the park’s locations. Twenty years ago, the cruising viability of the area wasn’t guaranteed, as prior to the park’s establishment in 2003, many of the islands and marine ecosystems were in danger of being lost to development and unmanaged use.

The Gulf Islands National Park Reserve of Canada (pc.gc.ca) is composed of a patchwork of small preserves, un-

developed islands and donated properties. It’s spread across 15 islands, numerous islets and reefs totaling 36 square kilometres of land and 26 square kilometres of underwater preserves. Not all sites have been acquired for recreational boaters. Some have been preserved to protect land and marine ecosystems unique to the Southern Gulf Islands. Parks Canada also ensures the protection of the islands’ cultural assets. Along with recognizing the importance of the islands to the Salish First Nations, Parks Canada protects the buildings and artifacts of the early Kanaka (Hawaiian) and Chinese settlers, using the resources to bring island history to life.

Fragmented as the park may be, it’s easy to experience much of the park by boat.

IT IS EASY TO IMAGINE ARLENE AND I ARE VISITING AN ATOLL SOMEWHERE IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC

Our first stop on this visit was Beaumont Park on South Pender Island (PY May, 2024), where we moored Easy Goin’ to one of the many park mooring buoys available. Visitors can beach their dinghies or kayaks to enjoy this popular picnic and hiking spot.

Here is where you will find the highest point on South Pender Island, Mount Norman. A 2.4-kilometre switchback trail from the beach leads to the top of the 244-metre pinnacle revealing sensational vistas across the San Juans and Gulf Islands to Vancouver Island. It’s a steep, well maintained trail and the one hour hike up is well worth the effort. We launched the dinghy and headed southwest to Poets Cove Resort & Spa. After a wonderful lunch we made the short walk to pristine Greenburn Lake,

a portion of the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve. It was covered in lily pads about to bloom and surrounded with wild yellow irises. The lake is a wonder as natural lakes are rare in the semi-desert Gulf Islands.

Our next destination was Otter Bay and Roesland on the west side of North Pender Island. We set the anchor in good holding and took the dinghy to the park’s dinghy dock. At the head of the ramp, we discovered a former 1908 farmhouse that now serves as the Pender Island Museum and offers a glimpse into the island’s past. This is also the location of Parks Canada’s field office. We walk to the end of Roe Islet to take in the view of Swanson Channel and Salt Spring and Vancouver islands.

Then it was back along the islet and up Shingle Bay Road to the Roe Lake trail head and through the forest of mostly second growth to beautiful Roe Lake. If you’re looking for a full day of hiking and exploring, this is a terrific location for that. There is a 1.7-kilometre trail that circumnavigates the lake.

The following morning, we weighed anchor and set a course for James Bay at the north tip of Prevost Island, which has national park reserve lands on both the north and south shores. Visiting boaters tend to favour James Bay and Selby Cove located at the northern tip of the island where park lands form a narrow point adjacent to a deep cove with a varied shoreline that include steep rock faces, gentle rising rock

shelves, gravel beaches and 10 campsites. We spent the day wandering the shoreline and uplands, where we discovered evidence of old homesteads including split cedar fences and the remains of fruit orchards.

We also took the trail that follows the north side of James Bay leading to Peile Point. The 30-minute hike was a bit strenuous (maybe our age catching up with us), nevertheless it was a good

Our journey continued the next day as we headed to our next destination. At the mouth of Salt Spring Island’s Fulford Harbour, Russell Island is blessed with many natural features typical of the southern Gulf Islands. Open meadows of native grasses host yearly bursts of camas lilies and a variety of other wildflowers. The shell midden beaches are a testament to its first inhabitants, the First Nations that date back 3,000 years. There is a short 1.2-kilometre loop trail to stretch your sea legs.

Visitors anchor on the northwest side of the island over good holding, where the view is dominated by the Salt

Spring Island mountains rising above the harbour.

During the fur trade, the Hudson’s Bay Company hired several hundred Hawaiians as labourers. After their contract expired, some decided not to return to their homeland and many settled in the area. Russell Island was settled by William Haumea and inherited from him in 1902 by Maria Mahoi. Both were of Hawaiian ancestry. A house, an orchard and remnants of what were once flourishing vegetable gardens prove that Maria and her family lived an almost self-sufficient life. A forested trail takes you to the homestead.

Next on the float plan was Portland Island where we spent two days anchored in Princess Bay on the southern side of the island. On previous visits we have anchored in Royal Cove on the island’s northwest side.

Portland Island (also known as Princes Margaret Marine Park) was presented as a gift to Princess Margaret in 1959. She returned the island to British Columbia in 1967. The island features an abundance of wildlife, cliffs, protected coves and sand beaches, and it has long been used by First Nations people, whose shell beaches are the most visible remainder of their presence. The fruit trees, roses and garden plants also found on the island testify to the more recent settlement by Hawaiian (Kanaka) immigrants in the 1880s.

Cruising south, the next stop is small Isle-de-Lis, also known as Rum Island, a favourite retreat for kayakers offering a gravel beach to land a dinghy or kayak and three campsites. This small island is covered with a Douglas fir and arbutus forest. The narrow isthmus connects Rum Island to neighbouring, privately owned, Gooch Island. We anchored on the

GULF ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK RESERVE Russell Island Prevost Is. Roesland Isle-de-Lis (Rum Island) Portland Is. Cabbage Is. Tumbo Is. Narvaez Bay Winter Cove Sidney Spit D’Arcy Island Greenburn Lake S. Pender Is. N. Pender Is.

north side of the island over a sand bottom for protection from a southern breeze.

The final destination of our exploration cruise was Sidney Spit, what we consider the gem of the Gulf Islands. Located at the north end of Sidney Island, Sidney Spit is a popular cruising destination. Its sand bluffs, tidal flats and salt marshes teem with birds and marine life and provide hours of entertainment.

While roaming the trails of the island we discovered the remnants of various settlements, sites of First Nations cultural and spiritual significance and evidence of an abandoned brick factory. There are interpretive signs along the way with historical information and photos. The spit is in the Pacific Flyway,

so it attracts a large numbers of shore birds, and other marine life.

We enjoyed our cruise through the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve and found that it has something for every crew member.

Due to time restrictions and prior commitments, we were unable to visit all the park sites, most of which we have visited on prior trips to the area.

With striking views of the Gulf Islands, numerous small coves, cobble beaches and seven backcountry campsites, D’Arcy Island is a haven for Kayakers. The island has a unique history. From 1891 to 1924 members of Victoria’s Chinese community affected with leprosy were exiled to the island to live out

the remainder of their lives. The inhabitants were fed, clothed and housed, but received no medical attention. An orchard and the disintegrating remains of a few buildings are the legacy of this sad chapter of Canada’s history.

Surrounded by forested uplands, open meadows and salt marshes is Winter Cove on Saturna Island. Visitors can enjoy a picnic area and easily accessible walking trails. There is a 1.2-kilometre trail that leads to Boat Pass with a spectacular view across the Strait of Georgia. A strong tidal current rushes through Boat Passage at the east side of the cove, and can be viewed close-up from a viewpoint. The cove itself is an excellent sheltered anchorage and a dinghy dock provides easy access ashore. Winter cove is the location of the annual Canada Day Saturna Island Lamb Barbecue. Everyone is welcome to enjoy the country fair style picnic.

Narvaez Bay, another park site on the southern end of Saturna Island, is one of the most beautiful and undisturbed bays in the southern Gulf Islands. The dark green of a regenerating Douglas fir forest is punctuated with the contrasting lime green and copper colours of Magnolia trees. The bay also offers seven campsites.

Cabbage and Tumbo are nesting sites for oystercatchers and bald eagles and provide some of the most magnificent sunsets in the Gulf Islands. The park offers 10 mooring buoys, five campsites and five kilometres of hiking trails. This is also a suitable location to set the hook over a good holding bottom, soak the crab trap overnight and fish around the outer reef at the entrance of the harbour.

REQUEST A QUOTE

IIn 1932 the Thermopylae Club was formed in Victoria, BC. The organization named itself after the Thermopylae, the superfast clipper ship—sometimes called the queen of the seas—that had been based in Victoria in the 1890s. The club’s motto is, “Fostering an Interest in Ships and the Sea.”

No founding member of the club survives today. Nor do we have an exact idea how the organization started. We know that Captain Alexander McDonald, the first master, and author/historian Major FV Longstaff, a retired British army officer, were both instrumental in launching the organization.

In my mind’s eye, I’ve pictured how these gentlemen could’ve launched this group of ancient mariners. I see McDonald and Longstaff in the early 1930s, each taking a walk near Victoria Harbour on a wintery day. McDonald, looking at Longstaff and tipping his cap, asked, “Did you sail on the clipper Thermopylae? I think we might have met somewhere.”

“No, but I know some men who served on her,” was the response.

“But did you ever sail out of Victoria?”

The two men began comparing their dates of service and asking about other shipmates. Soon, one suggested getting a coffee to get out of the cold wind. Having so much joint history, they met again to discuss their maritime adventures. A friendship blossomed. They then invited other mariners “who loved old ships” to these encounters. By 1932, 20-odd men created an official club, naming itself after the iconic clipper and adopting the flag of Thermopylae’s builder, the Aberdeen-based White Star Lines, as their own. They decided to meet once a month, with an annual dinner, and share their tales of derring-do.

The club has maintained logs of every meeting since, welcomes all ranks and annually holds elections for the master, purser, supercargo, first mate, second mate and directors. The master appoints the cook.

The Thermopylae Club has had a close relationship with the Maritime museum of BC. For decades, club members convened at the museum’s premises until the building was closed. The Museum’s present location is small and therefore limits the number of people who can attend the club’s meetings.

IN APRIL 2024, I attended the Club’s 900th meeting and annual dinner at the Royal Victoria Yacht Club. The menu harked back to earlier days and included salt horse (corned beef), dogfish (salmon), boiled cabbage, spuds, plum duff with ambrosia sauce, and, to prevent scurvy, a ration of lime juice. Not a weevil in sight.

Each month since its founding, the Thermopylae Club has invited a member, or another mariner, to speak about their seafaring life. The 2024 dinner speaker was Captain Rich Marriott, recently reaching ancient mariner status. For 35 years he served on fishboats,

THERMOPYLAE

tugs and government ships, rising up the hawsepipe to become the master of CCGS Sir Wilfred Laurier. He spent time in Antarctica “mentoring the Royal Navy in ice operations.” Marriott thus joined a long line of storytellers.

Many past storytellers also put pen to paper and described their most memorable experiences. These yarns were recorded in the club’s logs and were stored until the 1960s when the Club chose to make the stories better known. Historian and writer Ursula Jupp was a natural choice and with slight edits and essays providing context, published two volumes of these recollections. The first, Home Port: Victoria was published in 1967; the second, Deep Sea Stories, arrived in bookstores in 1971. Her books bring to the public true and widely varied stories of seamanship and

survival during the transition from sail to fossil fuel.

Jupp was born in the Scilly Isles, and she and her family emigrated to a Canadian prairie farm. The draw of the sea, however, was too strong and they moved to Victoria a few steps from the sea. She was the first woman to join the club’s ranks with full membership in 1954, decades before other men-only organizations opened their doors to women. The 272 yarns included in these two volumes offer a snapshot of maritime history and customs of the era between around 1880 and 1930 and reveal just how hazardous marine professions can be.

IN DEEP SEA Stories’ first tale, Captain Alexander McDonald narrates how he witnessed a highly inebriated sailor

being shanghaied onto the St. Paul, a downeaster whose San Francisco departure had been delayed by a one-crew shortage. McDonald describes how, in 1890, he observed two men fighting near the ship: “Hansen continually edged the man toward the face of the dock. At its base a boatman had backed in close, and when Hansen let the drunk have one under the chin, over the dock he went and square into the boat... [At the ship] they pulled the drunk up in a bowline…” The St. Paul left soon afterwards.

Ships still wreck and sink today, but serious mishaps during the age of sail were even more frequent. McDonald described some hazards he experienced or observed. In 1883, at age seven, he fell from the top of the companionway and was knocked out. At Cape Leeuwin, he saw an apprentice fall overboard while

furling a mizzen royal. A two-hour search found nothing. In 1891, another apprentice fell into the sea while trying to set the main topmast staysail in a fierce gale and high seas. “Impossible to attempt any rescue,” McDonald writes.

One long hilarious tale uncovers the travails of “a third cook in a third-class galley” for 300 steerage passengers travelling from UK’s Tilbury to Sydney, Australia. Fred Kemp worked for a vitriolic, profane chef. His main task was to peel potatoes in conditions that would

never pass BC WorkSafe standards. Mishap follows mishap below deck.

In another tale, Frank Wilson revealed the hard truths (inappropriately worded for today) of about 500 “coolies” who were transported on the Latona from the East to the West Indies. They slept on a “tween deck of soft lumber.”

A cyclone caused the ship to leak severely and when the crew couldn’t keep the pumps going, some “passengers” were enlisted. These men frequently deserted the job. Eventually, they were plied with bamboo stimulants and they took to their pumping task. A good thing too according to Wilson, because if the ship had sunk, the derelict lifeboats wouldn’t have held 15 percent of them.

Other yarns also portray the past marine industry on our coast. Several tales remind us how active whaling

once was in BC and describe the whale rendering camps. Schooners were built in Victoria to hunt fur seals in the Bering Strait after sea otter overharvesting eradicated them from BC waters.

Not all stories come from logs and books. Jamie Webb, MMBC’s president, told me about his grandfather, Francis Webb, born in England in 1878 and arriving in Victoria in 1889. He then served aboard a UK-flagged sealing schooner near the Pribilof Islands, where northern fur seals were captured in great numbers. “My dad told me the Russians monopolized the fur hunt, arrested the trespassers and his father spent time in a Petropavlovsk prison,” Jamie said. “At age 14! He was released after a sealing treaty was signed.” Francis joined one more voyage from Victoria to China, delivering lumber and bringing back a cargo of rice. That was enough, he decided—he retired from his marine career at 16 and turned his hand to house building and carpentry. But not forgetting his seafaring, he joined the Thermopylae Club in 1948.

Thermopylae loading at Brunette Sawmill in Sapperton, New Westminster on March 27, 1894. Note the size of the timber in the photo.

Grandson Jamie, who never got to meet his ancestor, joined in 1984. “I like the family tradition and really value the diversity of experiences these professional mariners and offshore sailors bring,” he said. “It’s a very welcoming group. Not at all stuffy.”

THE THERMOPYLAE CLUB doesn’t just entice members who’ve been at sea: it introduces them. Graphic artist Denton Pendergast, who developed the Victoria Harbour website and its 450 stories, joined the Club in 1996 without having been a mariner. “I arrived in town from Ontario,” he said, “and the first person I met was the then head of the Salts sail-training program, Martyn Clark, who was building the schooner Pacific Grace. I visited the yard often and also got to know the late John West,

who, deeply involved with the MMBC and maritime ventures, took me out on the water. As my grandfather had been a tugboat engineer, I had some fascination with boats. Both John and Martyn were Thermopylae Club members so I joined too. The members were so welcoming and helped feed my curiosity about nautical topics—leading me to the creation of that website and local lore.”

TONY GOOCH AND his wife Coryn have been high-latitude sailors and have covered tens of thousands of miles. Tony also completed a solo, non-stop circumnavigation in 270 days from Victoria to Victoria. He served as the Thermopylae Club Master for 13 years. He views the organization fulfilling a vital social role. “Members come together in a relaxed atmosphere,” he said. “They enjoy the company of fellow mariners and the storytelling. Some drove tugs alone or worked solo in the engine room. These fellows were isolated, often away from home for

long stretches. The club cements the fabric of their lives and creates a sense of belonging.”

The club also represents Victoria’s long tradition as a maritime port,” he continued. “And our funny little club maintains these traditions.”

Part of these traditions include service to the community. The club sponsored the restoration of the Tillicum, the Indigenous canoe turned sailboat by Captain John Voss, who leaving Victoria, partially circled the globe.

She’s part of the MMBC collection. A small group of members built a large model of the Thermopylae. And, each year, along with BC Ferries, the organization presents its Watchkeeping Mate Award to the Camosun College School of Trades and Technology to the student earning the highest marks on Transport Canada’s examinations.

OVER THE LAST few decades the Thermopylae Club has placed a group of plaques on the “Parade of Ships” wall around Victoria Harbour, part of the 162 bronzes that “commemorate famous vessels in the history of Victoria.” They include such famous sailor/circumnavigators as John Guzzwell in Trekka, Tony Gooch in Taonui, and Beryl and Miles Smeeton in Tzu Hang. And of course, Thermopylae herself, the inspiration for the 92-year-

DESPITE HER BEING one of the fastest clipper ships of her era, Thermopylae was on the cusp of being obsolete by the time she was registered in Victoria as her homeport. Built by the Aberdeen White Star Line in 1868, she was a 1,300-ton composite ship with a teak hull above the waterline, elm below and supported by wrought iron frames. The metal frames increased cargo

space and kept her from hogging. To obtain the highest price for a cargo of new tea, a highly prized luxury item, she set a record sailing from Shanghai to England. Other ship builders took note and built similar clippers, including the Cutty Sark, which gave Thermopylae a run for her money. The completion of the Suez Canal in 1869, however, first diminished, then

stopped the clippers’ viability as coal-fired steamships were able to match or surpass the clippers’ speed in delivering goods from Asia to Europe. The Thermopylae switched from the tea trade to transporting wool from Australia, again setting records.

In a later chapter, Montrealbased Mount Royal Rice Milling & Manufacturing Co. bought the Thermopylae in

1890 for the Asian trade and made Victoria her homebase. A year later, she delivered rice from Rangoon (Yangon today in Myanmar) to the warehouses on Store Street. Usually, when returning to Asia, she carried lumber. She ended her tenure as a training ship for the Portuguese Navy, but eventually she was declared derelict and torpedoes sunk her off Lisbon in 1912.

LLike flares and lifejackets, emergency bilge pumps are a safety investment that boat owners hope they’ll never need. They can provide extra time when taking on water—time that can be spent searching for and repairing a leak, donning a life jacket or making a distress call. Here’s some common-sense advice on emergency bilge pump options, installation and maintenance.

There are a number of choices when it comes to emergency pumps, from engine driven units to manual pumps, however electric powered centrifugal pumps are probably the most common and are the focus of this article. They pump a lot of water, are relatively inexpensive and are designed to operate while completely submerged.

They also have large internal tolerances and can pass small amounts of debris (a plus for emergency pumps), however this also makes them highly sensitive to vertical or static head—in other words, the higher they have to push water vertically, the less effective they become.

In addition to electrical pumps, you may also want to consider having a large capacity manual pump on board. Though useful as backups, keep in mind they’re powered by elbow grease and even the fittest crewmember will have a hard time keeping up with them after a while—assuming you can spare a member of the crew to man the pump in an emergency situation.

Engine-driven emergency pumps allow you to harness the tremendous

Static Head, the distance the pump needs to lift the water. A three-foot static head equals a 30 percent loss, so a 500 GPH pump will be pumping at 350 GPH. 3ft.

power of the engine in the event of hull breach. They can be powered off the crankshaft pulley (using a manual or electric clutch assembly) or drive train.

The Fast Flow Emergency Bilge pump for example, mounts directly to the engine shaft and as long as it’s turning, the pump is operating and starts working automatically in the event of an emergency. The smallest Fast Flow pump (the two-inch model) can pump 18,000 litres (4,800 gallons) per hour at a shaft RPM of 800 and a whopping 91,000 litres (24,000 gallons) at a shaft RPM of 2,000.

Another option is installing a suction takeoff from the engine’s raw water pump. Just remember that running the engine pump dry will damage the impeller, and that the intake connection should be in front of the sea strainer (so you don’t suck bilge debris into the engine). This is a proven and accepted pumping method, but know

Above: Emergency take off from engine. Below: Fast Flow Emergency Bilge Pump installation.

what you’re doing before you do it— otherwise you can seriously damage your engine.

Emergency pumps should be securely mounted and configured to automatically turn on when bilge water level reaches a predetermined height above the cut on point for the primary pump (typically three to four inches, but low enough to prevent

water from overflowing the bilge and damaging furnishings or equipment).

This lets the smaller primary pump take care of normal bilge water accumulation (with less battery drain) and leaves the larger pump to kick in only when needed. It also keeps the emergency or backup pump from resting in the normal accumulation of bilge water, where it can become clogged with sludge and debris or seized from disuse.

Discharge thru-hulls for your emergency pump should be situated well above the waterline to prevent water from siphoning back into the bilge. Siphon breaks and riser loops are also recommended. Ensure they reach at least 18 inches above static waterline where possible.

Use marine grade hose for pump discharge runs and double clamp all bilge pump hoses at each end with marine grade stainless where possible. Make sure all pumps, float switches and strainers are easily accessible, something essential for routine maintenance, emergency repairs and to free the intake should it become clogged. Install “manual on” switches for each pump in addition to any automatic float switches that may be installed. This allows you to operate the pump

should the float switch fail.

Provide appropriate circuit protection for each pump and ensure all electrical connections are located well above normal bilge water levels (to reduce corrosion issues) and properly terminated with marine grade connectors—preferably those featuring heat shrink.

Finally, it’s always a good idea to include a visual/audible high-water bilge alarm as part of your emergency dewatering strategy. Alarms must be loud enough to be heard over engine noise while under way and ideally by passersby or marina personnel when docked.

Installing a visual “pump on” indicator at the helm for each electric bilge pump is also a good idea, one that can provide even earlier indications that something is amiss.

Haul out (30 to 130ft)

Custom stainless steel

Blasting, painting, coatings

Mechanical, plumbing

Pneumatics, hydraulics

Steel & aluminum welding

Custom woodwork & decking

Engine repower & retrofit

Steering controls, rudders

Shafts, propellers, zincs

Electrical repair & retrofit

SSailboat racing is all about skill and gear development, combined with proper application and execution. It’s knowing

your boat, understanding the game and perhaps most importantly, having faith in your decision-making process—as success in any sporting competition is born from clarity and confidence. Let’s take a look at this through the lens of a sailing crew or team. This should be fun. Sailboat racing is unique in sport, due to the tremendous range in boat types, crew sizes and racecourse format or “playing field.” While recognizing this

diversity, there are constants that can be applied on board any boat, at any time, in every kind of sailing competition! Let’s begin with a basic premise that I would propose is foundational in sailboat racing, and that is to sail fast, with efficiency and purpose! Accepting these touchstones is important as these are the primary threads that tie together a successful race, regatta or long-term program. Let’s begin with the sail fast

Thomas Hawkerpart, which sounds like such a simple and obvious goal, yet every sailor appreciates just how many small details combine to achieve the very best straight-line boat speed. There’s below the waterline preparation, we’ll leave that for now. Next is rig tune, an ongoing science project of refinement that includes such things as rake (forestay length primarily), shroud tension (uppers, intermediates and lowers) and prebend (mast chocking at the deck, mast step position). Then, there’s the marriage between the rig set up and the sails, arguably the most important speed producing element, with an infinite number of subtleties! The challenge for a race team then, is to hone in on the fastest settings throughout the wind and sea state range and consistently extract the potential out of the sail plan. In practical terms, this means diligent trimming, relating to halyard, backstay, outhaul, sheet tension, lead position, both fore and aft/inboard and outboard. All the while there will be deference given to heading, helm movement, balance, along with immediate goals and big picture strategy. Coordination between helm, strategist, trimmers and each crew member will only become clear with one final piece of the puzzle: good communication!

THIS LEADS US right into the realm of sailing efficiency, including crew mechanics and positioning, boat balance, sail changes, maneuvers, tacking, gybing and hoisting and dousing sails. Crew dynamics are so important while performing each of these tasks, not just in terms of who does what, but how everything meshes. That’s why, in my experience, it’s important for every crew member to understand every job on board. That shared knowledge and level of engagement gets the whole team on the same page thinking about small tweaks (sometimes big tweaks) and encourages ongoing development and progress. Small improvements in efficiency may not be obvious at first, but through practice and repetition,

improvements in process will show up in the long game, especially when put under pressure.

BACK TO THE word engagement for a second. I think it’s the glue that holds the crew together. The commitment to give your best, from before the starting gun, through to the finish line and beyond, that’s the shared common

ground. Sailboat racing is of course a physical sport, but just as importantly it’s a mental challenge. We’re all motivated by different things, but I think anyone who races is driven by that competition and loves the feeling when it all comes together in a good result. This is what I mean by sailing with purpose. I can think of several other words that also relate here: Awareness, focus,

Transient Moorage May to September 30/15amp Power, Wifi & Garbage with Moorage Gasoline and Diesel RESERVATIONS HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

GENERAL STORE & MARKET

Coffee Shop, Ice Cream, Produce, Meat, Seafood, Fishing Gear, Bait, Ice, Books, Clothing & Gifts

Donate your boat in support of our

Donate your boat in support of our local community of sailors with disabilities and receive a tax receipt for its

We call that a win-win.

We call that a win-win.