Covering the deeper issues & untold stories that are shaping Maldives

Covering the deeper issues & untold stories that are shaping Maldives

Chief Executive Officer

Akhmeem Abdul Razzaq

Director

Mohamed Khoorsheed

Director

Ibrahim Areef

Chief Operating Officer

Ahmed Nasir

Chief Design Officer

Zaya Ahmed

Art Director

Hamdhoon W.

Chief Commercial Officer

Raaya Abdulla

Chief Editor Nashama M.

Managing Editor

Ibrahim Maiz

Assistant Editor

Maani Mohamed

Multimedia Journalist

Hassan Moosa

Multimedia Journalist

Ahmed Raaif

Multimedia Journalist

Ahmed Shaif

Content Creator

Ali Rishfaan

Office Assistant

Mohammad Ratan

Website orcamedia.group qrco.de/orcamediagroup

Advertising & Sales marketing@orcamedia.group

+960 7984664

Address

Ma. Oliveena, 4th floor, Chaandhanee Magu, 20195, Malé, Maldives

Greetings and welcome to the first issue of MV+ magazine, an annual publication dedicated to shedding light on the deeper issues & untold narratives that are actively shaping the Maldives.

For this year’s issue, the cover report will bring forth three true and personal stories of students who migrated to the capital city Male’ for better education during 90s and 2000s. Their stories bring to light buried customs of servitude and class struggles between raajjetherey meehaa and Male’ meeha — a subject that has not been talked about in detail and the gravity it deserves.

Flipping through the reports published in this edition, readers will recognise a cohesive theme among many of our articles: the right to residency. The right to migration is granted to all Maldivians under the country’s constitution, yet its nuances have escaped the many policies formed by our governments. Some of our articles will also touch on the economy, history, and social issues.

While broader issues such as politics and the economy have become the centre stage in many local media coverages, we believe that exploring these topics through the lens of individual experiences and struggles brings a richer and more relatable perspective to our readers. This sentiment echoes through and drives our media coverage.

This issue will also feature the winners of MV+ Community Impact Awards 2024, an event organised to honour select NGOs and their exemplary community service.

• We Crossed An Ocean To Go To School

• Tourism Workers Run the Economy While Others Reap the Benefits

• The Dark Side of Government Subsidies

• Unfinished Ambitions: The Cost of Stalled Development Projects in the Maldives

• Dredged for Show: The Disappointing Legacy of Land Reclamation in the Maldives

• Mounting Debts and Unpaid Fishermen: The Case for Privatising MIFCO

• Maldives on the Brink of Bankruptcy: Who is Responsible?

• Maldives Economic Landscape in Numbers

• The Great Burden of Retirement Allowances for Judges, Parliamentarians, and Presidents

HISTORY

• Palestine, Israel and the Maldives: A

• Cat Meat Controversy: How Safe Is Your Food?

• Death Penalty — A Symbolic Verdict on Paper

• Obesity Rates Surge in Maldives: Is the Sugar Subsidy to Blame?

• High Stakes: The Gambling Crisis Sweeping Through Maldivian Youth

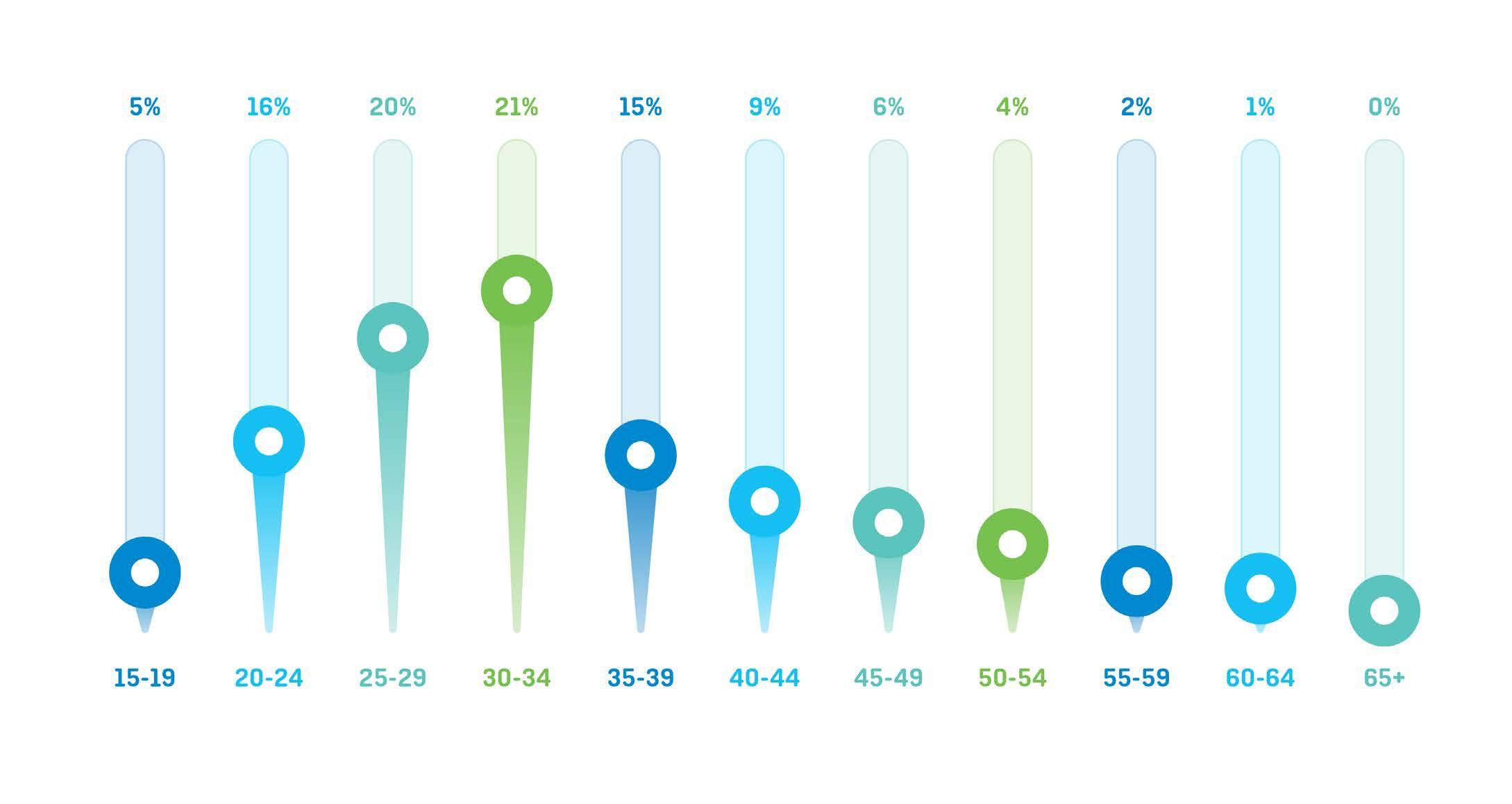

• Social Fabric of Maldivian Society in Numbers

• The Price of Progress in the Capital City

• Meet Soodhaththa, the Oldest Midwife of Hulhumeedhoo, Who Delivered Over 1400 Babies

• Editorial: Permanent Address, Permanent Problem — End Address-Based Discrimination

• Campaigning for Equity: The Case for a Dhaftharu Seat in Parliament

• End Gerrymandering Now: A Call for Fair Representation in the Maldives

Written by — Hassan Moosa

Shiyan* Stumbled Into The Alleyway Behind The House, The Weight Of Exhaustion Pulling Him Down. He Hadn’t Eaten All Day, And After Scrubbing Four Toilets, His Body Could No Longer Keep Up. As He Bent Down To Put Down The Cleaning Supplies, His Legs Gave Out, And He Fell To The Ground, Unconscious. He Regained Consciousness After A Few Minutes, And For A Moment, He Just Lay There, Too Weak To Move. Eventually, He Forced Himself To Stand, Determined To Finally Go Eat. No One Knew He Had Collapsed From Hunger.

This Was Life His Life As A ‘Gengulhey Kujjaa’ In Male’— Where The Hopes Of A Better Education Meant Enduring The Indignity Of Servitude.

The year-end school holidays of 2002 were a turning point for thirteen-year-old Yoosuf Shiyan. Having just completed grade seven, Shiyan was preparing for secondary school on his home island in Haa Dhaalu Atoll. However, the island school only offered commerce streams for secondary grades. His family, relatively well-off for a family living on an island with a population of 1,000 , decided to send him off to stay with a distant relative in the capital, Male’ and study at Majeedhiyya School.

Shiyan, the second oldest in a family of five, had shown great promise—he’d finished seventh grade with top marks and aspired to become a prefect, perhaps even the school captain one day. The prospect of moving to Male’ excited him, as he looked forward to studying at Majeedhiyya School, the top boys› school in the country.

For many families living on remote atolls, sending their young children away for education was a

common practice. Families from smaller islands often sent their children to the best school in the atoll, typically in the atoll capital. Those with means and connections opted to send their most promising children even farther, to the capital, Male’.

By the early 2000 s, the number of schools across the atolls had increased and primary school was widely accessible. But many island schools were just beginning to offer secondary and higher secondary education, leaving Male’ as the only place where quality secondary education was guaranteed. This meant that many children like Shiyan still had to uproot their lives and cross the ocean to attend secondary school.

But the reality of studying in Male’ reveals a darker side of classism, servitude and structural inequalities in Maldivian society.

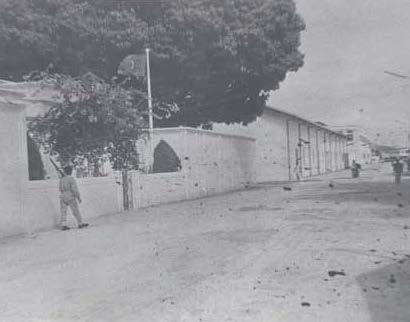

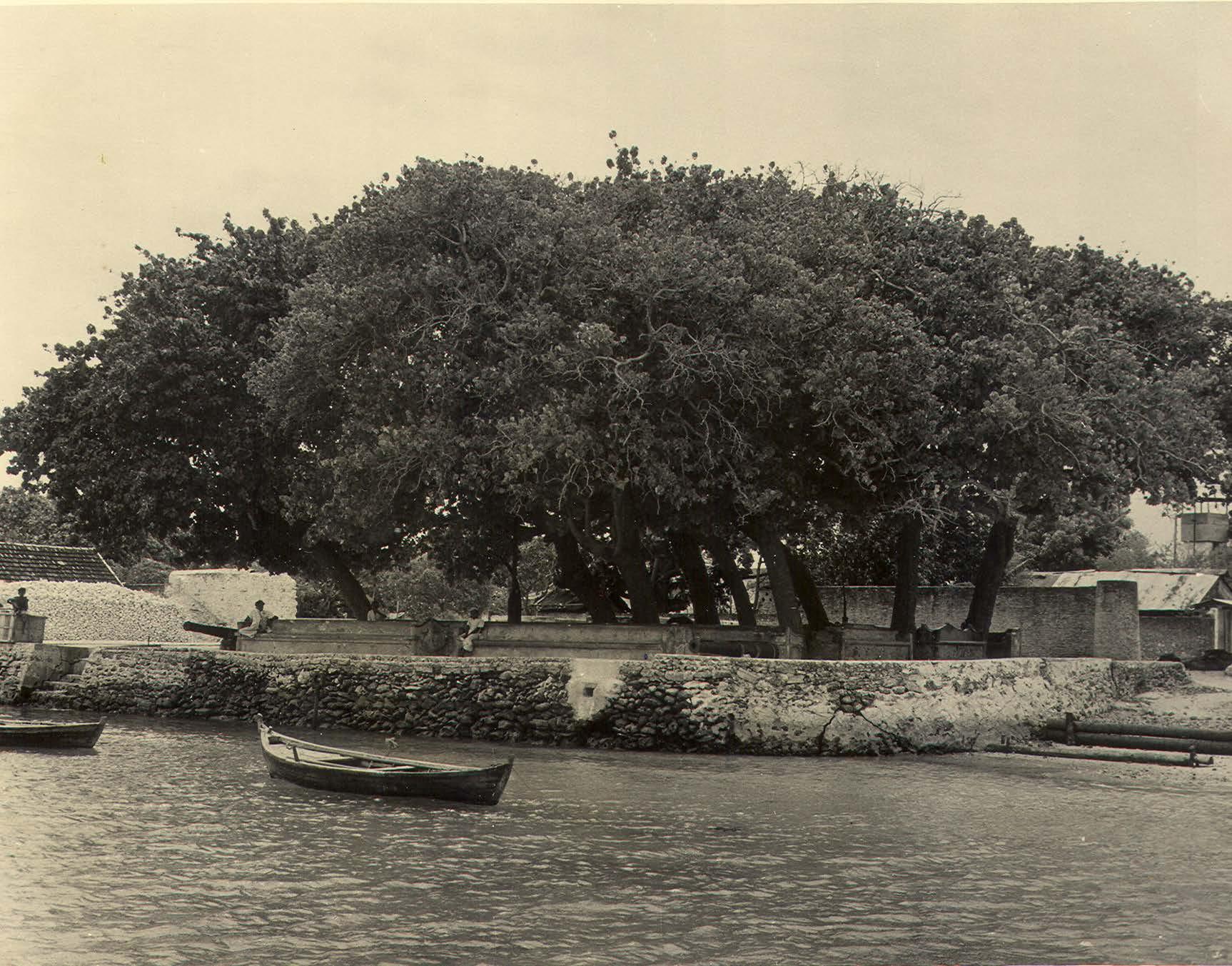

In 2002, Shiyan got on a boat with his father, crossed five atolls and stepped off onto a Male’ on the cusps of change.

President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom was preparing for a referendum to secure his sixth and final term as President. The following year would prove crucial for the burgeoning democratic movement in the capital. Male’ was already bursting at the seams from political tensions, rapid urbanisation, and overcrowding. The resident population of Male’ had reached 100,000, crammed into a land area of barely 2 square kilometres.

Migration trends from that time show a steady influx of people from distant atolls like Addu and Huvadhoo in the south and Thiladhunmathi Atolls in the north. Within the first five years of the 2000s, migrants from Raajjethere (the Atolls) gradually outnumbered the registered Male’ population. A significant portion of these migrants, like Shiyan, were between the ages of 10 and 24, moving to the capital in pursuit of better education.

Photography by — Aishath Layaan

Upon arriving in Male’, Shiyan was taken to his aunt’s house, while his father temporarily slept at the Islamic Centre until the school enrolment was completed. Shiyan sat for the entrance exam to join Majeedhiyya and eagerly awaited the list confirming his enrollment. However, the year 2003 began with the government announcing that students enrolling in Majeedhiyya would be split up, with half allocated to study at Dharumavantha School. Shiyan’s name appeared on the Dharumavantha list.

From the beginning, Shiyan noticed that he was treated differently both at home and at school. He slept on the floor in the boys› room - which housed 6 people - setting up his bed space only after everyone else had gone to bed.

“Looking back, I had it good then. I didn’t have to do much, but I did notice even then that I received different treatment,” he recalls.

For breakfast, he was given two thick pieces of roshi specifically made for him, while everyone else ate regular roshi. He was assigned specific tasks, like putting away the washed laundry, grocery shopping from the nearby shops (“but not the market!”), and taking the lid off the rainwater well on rainy days to prevent it from overflowing onto the terrace. The boys in the house were difficult to get along with, often shooing him away from spare beds when he tried to nap. One boy, in particular, gave him a hard time.

He vividly remembers one night of heavy rain that flooded the room. He woke up to the sound of the boys laughing as his mattress became soaked from the incoming water.

“Every time it rained after that, I woke up with a jolt, almost like a survival instinct,” he says, with a dry laugh. Despite the challenges, Shiyan tried to stay on his best behavior, avoiding confrontation even when provoked.

But it wasn’t just the home where he felt like he didn’t belong.

At school, he was assigned to the science class with all the top students. He felt like an outsider from day one. Almost overnight, he had gone from being the outspoken, popular kid in his island school to the only Raajjethere kid in a class full of students from prominent Male’ families.

He recalls being left out of the honour roll and missing out on becoming a prefect as the batch moved to grade nine.

“All those children from the beyfulhu families, they were all made prefects. But I wasn’t. I think I was good in Dhivehi, so I got to be the house captain for the literary club, but that didn’t make me a prefect.”

This was important to him—a way to show his mother that he was doing well and making her proud.

“It was very demotivating. I think that was one reason I stopped trying so hard,” he says. “I was a very outgoing, popular student in my island school, but after I came here, there was no one I knew, no friends or family members, so it was lonely. It was scary too because there was a lot of bullying. So I had to be loud and act bad, to defend myself.”

He began standing up for other kids who were bullied, often landing him in trouble and leading to fights with other boys. Teachers started profiling him as a troublemaker, penalising him even when Male’ kids could get away with similar behaviour. “They used to tell me ‘kids from the atolls are usually very obedient; they come to study,’ but why are you not like that?” Shiyan recalls. Words like that made him want to rebel. “Heck no, I don’t want to be obedient”

More than anything, he was homesick.

Shiyan describes himself as a “mama’s boy,” who, from a young age, loved spending time at home, studying or reading books with the constant support and pampering of his mother. Moving halfway across the country and realizing for the first time that he had to take care of himself was a hard pill to swallow. But what was even harder was only being able to talk to his mother once a month. Mobile phones were a rarity then, especially if you weren’t middle-class. It was difficult to speak to anyone from the landline at home due to the lack of privacy.

“I remember the first parent-teacher meeting—my father was in Male’ at the time, and all the teachers told him I was a very good student. He rushed out of Dharumavantha and called Mom from the phone booth nearby to tell her all about it. That was a happy day.”

Happy days were far and few for Shiyan during those years, but he managed to complete three years of secondary school and sat for his O’Level examinations in 2006. After his exams he left for his island, hoping that he wouldn’t have to return.

“My brother, who’d moved to male’, was the one who went to pick up my results. I was on my island, I didn’t want to come back. I got pretty good grades, a couple of As and Bs.”

The good results meant that there was an expectation for Shiyan to study Alevels. His brother›s new colleagues asked him to bring Shiyan back to Male’ in exchange for a job while studying.

But as it turned out, his aunt said they couldn’t keep him anymore because there wasn’t enough room in the house. Instead, Shiyan moved to Male’ for his A’Levels to stay at a stranger’s home as a Gengulhey Kujjaa.

Gengulhey Kudhin (servant boys/girls) was a common practice among elite Male’ families dating back to the 1950s. Teenage children from rural islands were employed as servants in exchange for the promise of a good education.

Many people alive today can recall either being a Gengulhey Kujjaa or living in a household that employed one. While the stories range from heartbreaking struggles to mutually beneficial arrangements, a common thread is the dynamic of a patron-servant relationship between the Male’ elite and rural islanders. The general arrangement was that a Raajjethere Kujjaa would be provided food and board in Male’ in exchange for doing household chores. There was also an underlying expectation that the child›s family on the island would keep sending “gifts” of island goodies to the patron family.

The brilliant Maldivian actor and comedian Yoosay captured this reality in one of his Dhiriulhumakee Meebaa episodes in the 1980s. In a 30-minute documentary, Yoosay plays the part of a young man named Muhammaa from Huvadhoo, who arrives in Male’ with his father, hoping for a better education. Instead, Muhammaa is made to do household chores and faces condescending remarks about his rural origins. His father, shocked to find him working instead of studying, decides to take Muhammaa back to their island, recognising the mistreatment rooted in their status as poor islanders.

The practice of Gengulhey Kudhin has now died out but it highlights the enduring culture of beyfulhism (elitism) and class discrimination that still permeates Male’ society today.

Shiyan was among the last generation of Raajjethere kids who worked as a Gengulhey Kujjaa. While studying for the A’Levels at the Centre for Higher Secondary Education (CHSE), he stayed in a house in Villingili, sleeping on a mattress on the floor once again.

“They were a bit more well-off, so at least I got a more comfortable mattress,” Shiyan recalls.

He was also given a bicycle, but it was only because he is expected to carry the trash to the waste center. This was one of the many chores he was expected to do at the house. His daily routine was gruelling:

“After I wake up, I have to clean everyone’s shoes, clean the TVs and CDs. I would finish cleaning around 10:30. I would then have breakfast and go to Villingili School to pick up their little

boy. After that, I would get ready for school and come to Male’ by 12. I would finish school and go home in the evening around 6 pm. I would go home, shower, do homework, and later take out the trash.”

On Fridays, he had to clean all the toilets in the house. One of those Fridays was seared into his mind. That morning, he made the mistake of visiting his cousins in Male’ before cleaning the toilets.

“When I came back, they told me, ‘You left before cleaning the toilets, so you won’t get any food before you clean the toilets.’ “

“So I had to clean the toilets—four toilets. By the time I finished, it was around 2:30 or 3 pm. I hadn’t eaten anything that day.I finished and went to put the cleaning materials in the alleyway behind the house, and I just fainted. I sat down, and I couldn’t get up; I just fell. I regained consciousness a while later, and then I laid there for some time. Then I picked myself up and went and ate. No one knew.”

“I promised myself that day I would spend my entire life working to make sure no other kid would have to go through that again.”

Shiyan says things got even more difficult for him at the house, “They started asking if I was taking things from the shops using their name but I was only getting what their children asked me to get.”

Stealing was one of the things Shiyan’s father had lectured him against when he first moved to Male’. His father drilled into him a deep sense of class consciousness and strong values of honesty and accepting his place in the hierarchy of society.

“He told me many times to never steal, to never eat any food if they didn’t offer it, to never argue. He made me believe that we are poor and lower-class people, so I had to be better. I had to study even if others in the class didn’t study, because they would get land, but I wouldn’t.

“It was my father who gave me that class consciousness I kind of blame him for making me feel that way, that I was lesser and poorer, but it’s true, we are different”

So the false accusation of stealing was the final straw for Shiyan, who called his mother and insisted that he move to

another house on rent. He and his brother then moved to one of the boarding houses that was starting to crop up in Male’. Shiyan is quick to point out that his experience is just one among hundreds. Many people, and especially girls who expected to stay home and do more household chores, face far worse.

“I was the last servant at the house. Before me, there would have been a lot of kids, and I don’t know what they went through. Many kids have faced sexual assault, been raped... I was lucky that I didn’t face any of it. There are a lot of untold stories. How can we know? Kids might even have died... we don’t know.”

“He told me many times to never steal, to never eat any food if they didn’t offer it, to never argue. He made me believe that we are poor and lower-class people, so I had to be better. I had to study even if others in the class didn’t study, because they would get land, but I wouldn’t. “

The founder of Novelty Publishers, Ali Hussain, hit the nail on the head when explaining the historical prejudice held by Male’ people towards atoll islanders in the third book of his Dhuhthanaa Ivunuaduge Handhaanhuri Bai series.

“Even though it has now faded from Maldivian society now due to widespread education and changes to our lifestyle, ethnic prejudice existed among Maldivians just as much as it was present elsewhere in the world. It was stubbornly maintained, starting from the very top of the government. At the time, Raajjetherey Meehun (atoll people) were considered Beerattehin (strangers). If you were born in the atolls, you are a stranger to Male’ people. Male’ people described islanders as people who never got saltwater sand off their feet. And supposedly if you are an islander you have 5 kulhandhu missing”, he wrote.

Fas Kulhandhu Madhuvun - is a derogatory insult historically aimed at people from the atolls. It implies that a part of their brain (kulhandhu is a local measurement equivalent to 25 madhoshi or 5.8 grams, so precisely 29 grams) is missing.

Ali Hussain, himself born in the atolls, describes how societal and legal policies discriminated against atoll islanders. Marriages between Male’ residents and islanders, especially involving a raajjetherey man and a Male’ woman, were frowned upon. There were also distinctions in dress, behavior, and seating between Male’ people and islanders. Additionally, islanders needed a permit to travel to Male’, which involved a complicated process, including obtaining a letter from the atoll chief, temporary registration, and adherence to strict rules about travel and address changes during their stay.

In the book, Ali Hussain explains that most of the atoll people living in Male’ stayed in their handler’s houses as servants. From his memory, he lists some people who worked as Gengulhey Kudhin and went on to study and become notable figures. This includes the writer Madulu Mohamed Waheed and the now famous businessmen and politician Burumaa Gasim Ibrahim

Male’ Privilege & Systemic Inequalities in Education

The practice of Gengulhey Kudhin has now become a thing of the past, but students of all ages migrating to Male’ for education has remained a constant throughout the past two decades.

Education is the top reason for migration to Male’ followed closely by migration to accompany family. A large part of these would account for families who move together to send their kids to school.

Aishath Nadheema’s educational journey began on the island of Naifaru in the 1980s, where she was among the first batch of students at Madhrasathul Ifthithaah, the oldest formal education school in the atolls outside Male’. As a top student, she excelled in her studies, sports, and extracurricular activities.

However, the limitations of the island’s education system soon became apparent. After finishing Grade 7 with top grades, Nadheema was forced to repeat the year because the school could not offer Grade 8. The following year, she was required to complete a “Pre-8” class to progress, only to face another setback when she had to repeat Grade 8 due to the absence of Grade 9. These repeated delays in her education eventually prompted her family to send her to Male’ City to continue her studies.

At the age of 18, Nadheema left her home and family to move to Male’, where she stayed with a family friend. She considers herself fortunate to have been treated like a daughter by her host, avoiding the heavy household chores that many other girls from the atolls had to endure while trying to study. However, her challenges were far from over. Due to her age, she could not enroll in a government school and instead joined the private English Preparatory and Secondary (EPS) school. There, she found herself needing to repeat Grade 9 to catch up on art stream subjects she had not studied on her island. The transition to Male’ was an eye-opener for Nadheema, who realized that students in the capital had a higher standard of English and greater access to books and information. This disparity motivated her to encourage her family to relocate to Male’ so her siblings could benefit from the better educational opportunities available there.

The years of repeating grades in her island school cost her precious years in her education journey. Her higher age was the reason she was not allowed to join one of the government schools. It also meant that she would graduate school much later, putting her at a disadvantage.

According to a study conducted by UNICEF and the Education Ministry in 2015, school principals say that the number of students migrating to Male had increased in the preceding five years. Many students interviewed for the study reported being bullied at school and mentioned issues like favoritism, lack of support from school personnel, and academic difficulties.

If there’s no family or friends in Male’, the remaining option is to stay in the boarding houses operated as businesses. These houses are dedicated to a separate section (kudhin baithibbaadhinun) in online listing websites such as ibay.

Accommodation, laundry and food are covered for a fee ranging MVR 2500 - MVR 3500 per person.

Living conditions in these unregulated houses are often harsh, with six to eight people crammed in tiny rooms, stacked to the ceiling with bunk beds. Many students from the atolls stay in houses like these when studying towards their college degrees at the National University campuses in Male.

Girls have it especially tough, expected to help the host with cleaning, cooking and laundry, in addition to their daily routine that usually involves studying part-time at night and working full-time during the day. The unstable environments in these houses often result in students often moving houses several times during their stay.

Rasheeda, a girl who moved to the capital in 2014 says she stayed in three separate houses during her three year bachelor’s programme. It is not uncommon for others to move even more.

Despite these many obstacles that people born from the islands have to overcome, government policies still prioritise improving the education services in the capital, often at the expense of rural communities.

As the population of Male’ expands and the newly reclaimed artificial islands of Hulhumale’ and Phase 2 gets populated with more people, schools are built in the male’ area at lightning speed, while schools in atolls struggle with getting teachers, computer labs, libraries. Higher secondary courses are only available in 59 out of 212 islands in the Maldives, making it impossible for some adolescents to continue their education unless they too migrate.

The result is a skewed education system that benefits or disadvantages children based on where in the country they are born.

There’s a number of research highlighting this gap. A person living in Male’ is likely to complete three more years of schooling than someone living in the atolls (UN Human Development Report, 2014). The gaps in years of schooling a person receives is the highest contributing factor to inequality.

Education is the best tool to cross across class barriers, but for most people living in the atolls, education is the barrier. People like Shiyan and Nadheema, despite their hard-fought struggles after migration, are now more likely to make it into the middle class. They’re also among the few who come from rural origins with the access and opportunity to occupy policy spaces and influence change.

The political landscape of the Maldives is full of leaders from elite families who had the access to education that many people in the atolls did not have. Seven out of the eight presidents in the Maldives studied at Majeedhiyya School in Male’ (the exception is President Mohamed Amin Didi who, although never a student, was the principal of the school between 1946 and 1953).

The current political elite are also more likely to have the means to send their children to study abroad. For many school graduates from the atolls, the only realistic option for higher education is the national university or local colleges run across the country - which diversified the courses offered in the last decade. Prior to that, many relied on government loans, scholarships, or private wealth to study abroad - chances that were limited to people from the atolls. In instances where people from the atolls did study abroad, there was a similar set-up of gengulhey kujjaa in the houses of Male’ elite living abroad.

Many government offices to this day reject graduates from local colleges in favor of foreign educated graduates. This inevitably means the baton of leadership gets passed on to a generation who - unlike the many graduates from local colleges - have a limited understanding of Maldivian society and the inequalities that exist within.

“I was a mama’s boy growing up , but I’m sad to say I’m no longer close to her,” Shiyan admits, reflecting on the emotional toll of being away from home for so long.

Migration and the struggles faced by Raajjethere students in Male’ create barriers to attaining an education and fractures families and communities, leaving many with a sense of disconnection from their loved ones and homeland.

“I was a mama’s boy growing up , but I’m sad to say I’m no longer close to her,” Shiyan admits, reflecting on the emotional toll of being away from home for so long.

Shiyan is acutely aware of how moving to Male and being separated from family at such a young age has affected him. He notices how the isolation of growing up in a place without loved ones has changed his personality and made it difficult for him to form emotional connections.

This sense of disconnection from family is familiar to many people. Migration to Male’ has isolated and fractured families. Migrants also describe not being able to find a sense of belonging, not in the capital that makes them feel like outsiders, nor in their own communities where that connection has been broken after years of living away.

Aisha Hussain Rasheed captured this deep sense of alienation and loss in her poem (translated) Meedhaa.

Uprooted and taken from the land we grew up in,

Planted here like rootless branches,

No matter how much you water us, we can›t take root in this soil.

We were swimming freely in the open waters around our islands

Until we were scooped up in a net, brought here and put in concrete tanks

Even if you make a hundred artificial beaches, we can›t acclimate to this water

We were running around barefoot in the hot sand,

In the afternoon heat, under the blazing sunlight,

Brought here and forced to walk on the paved roads,

Even in the best quality shoes, our feet still get blistered,

I went back to the island this break, back home, to my island,

Don’t they say an island will give love to its children like a mother loves her own?

But the soil is a thing that buries, not one that remembers,

After years of staying away trying, to seek a higher education, to reach higher positions, to obtain a higher standard of living,

I went back home and that motherland had forgotten me,

The home we grew up in stood derelict, a graveyard of childhood memories

When I went back to my island I realised,

That the island mouse will be stronger in the island.

I came back to Malé and realised

That here, mice are fed rat poison

I am a mouse that belongs neither in the island nor in Malé

This is not our home,

We and this place, this place and us

We are not of one another

We are mice that belong neither on our island nor in Malé

If not that, who are we?

Note: Above are selected excerpts from Aisha’s poem Meedhaa. You can see the full poem performed by Aisha at the Akurufoshi stage at Katti Hivvaru Festival 2016 on Facebook.

During our two hour conversation about his story of migration and education, Shiyan acknowledges it’s uncomfortable to recall these moments of his past.

“Us Maldivians, we have this collective mentality of not speaking about things, and if it’s out of sight, it›s out of mind.. We feel shame talking about the difficult things we go through.. I’m thinking about this after a long time, and if i’m being honest, I don’t want to be talking about this now either”

But, he also recognises how silence and accepting the status quo means things don’t change.

“I would go home to my island on holidays, and on the first night back, i would sit with my mother and tell her everything , but it never gets out.. Mom wouldn›t tell anyone, she wouldn’t want me to get kicked out of the house”

Shiyan feels strongly about breaking this culture of silence and speaking up. Feeling like an outsider during the formative years of his life has profoundly shaped Shiyan’s worldview. It made him more outspoken, and instilled in him a strong sense of justice.

“I shared my story once, on twitter.. I remember specifically some accounts and groups of people bullying me just for telling my story.. So talked to other activists and my friends said to me they don›t deserve to know our stories, they are not even worth it”

But he says it’s important that these stories are told, listened to, and acknowledged. It was one of the issues he felt should have been addressed when the previous government announced the a presidential commission on transition justice.

“I felt that our stories also need to be addressed too, because we had to come and live here like that because of a systematic issue of the state. The first step would be to acknowledge that this was an injustice that a lot of kids had to go through, historically.”

“If we don’t acknowledge it, and refuse to talk about it we are just moving forward with our eyes closed. The rights of a lot of kids are just being lost. Their future is being taken away and they are getting lifelong problems.”

Photography by — Aishath Layaan

Once the backbone of the Maldivian economy, fishing has long been eclipsed by tourism, which now serves as the country›s lifeblood. Tourism is not only the largest tax revenue source for the state and its citizens, but it also provides the active and productive workforce essential to running the nation.

The COVID-19 pandemic starkly highlighted the importance of this sector, demonstrating that tourism workers could sustain the country even

in the absence of many government employees. Tourism is the most sought-after industry after government jobs, particularly in resort employment. This sector has significantly contributed to the circulation of foreign currency within the domestic market, with a substantial number of expatriates also working in the industry. The dedication and sacrifices made by these workers, who often labour long hours away from their families, are vital to the survival and prosperity of the Maldives.

In addition to resort tourism, local tourism has played a crucial role in boosting economic productivity. Islands that had never dreamed of economic growth are now witnessing unprecedented changes. Guest houses, cafés, restaurants, water sports venues, and dive centres have sprung up to cater to tourists, funnelling dollars into the pockets of the local population and providing numerous economic benefits.

Despite their critical contribution to the economy, tourism workers often do not receive the recognition or support they deserve. While they are the primary source of income for the state budget, many are deprived of basic necessities, such as housing.

Tourism Sector Contributions

Overlooked in Government Policies and Benefits

Government housing schemes frequently prioritise employees of ministries and stateowned companies, often overlooking tourism workers. Housing projects, which typically consider the duration of residence in the capital, Male’, tend to exclude those who live and work in resorts, regardless of how long their families have resided in the city.

This lack of support extends beyond housing. Tourism workers are frequently left out of other government benefits, despite repeated promises to improve their opportunities. Meanwhile, many unproductive and underutilised government employees continue to enjoy these perks.

Although the previous government addressed issues like minimum wage and service charges, the solutions offered were insufficient. The state is funded by the taxes generated by the hard work of tourism employees, yet they remain largely invisible in government policies and initiatives. For the Maldives to build a productive and thriving generation, it is crucial to develop and implement policies that prioritise and support the tourism sector. These workers are the engine driving the nation’s economy, and their contributions must be recognised and rewarded accordingly.

MARITAL STATUS OF MALDIVIAN RESORT EMPLOYEES

55

6,639

12,746

1,617 NOT STATED MARRIED WIDOWED NEVER MARRIED DIVORCED

40

We might not think it, but our everyday lives heavily rely on the many subsidies granted by our government. The government spends a huge chunk of state expenditures to ensure our lives are as affordable as possible, whether subsidising healthcare, electricity, or food.

However, the subsidies given to certain sectors have been called into question. Many ask just how much of the benefits of these subsidies actually trickle down to the regular citizen or how much of them benefit the right people who actually need it.

The Problem with Harmonising Subsidies; Everyone Should Not Be Equal

Subsidies given through the national healthcare scheme, or Aasandha, are available to everyone equally; even if you are rich or poor. This is the main criticism of advocates. And it’s not just these voices, but the Aasandha company has previously acknowledged that the current free healthcare system is not financially sustainable. What many do not know is that many of the funds allocated to afford free healthcare go straight to the pockets of rich businesses that sell overpriced medications. Meanwhile, the average citizen walks away with low-quality medication and a free doctor›s appointment.

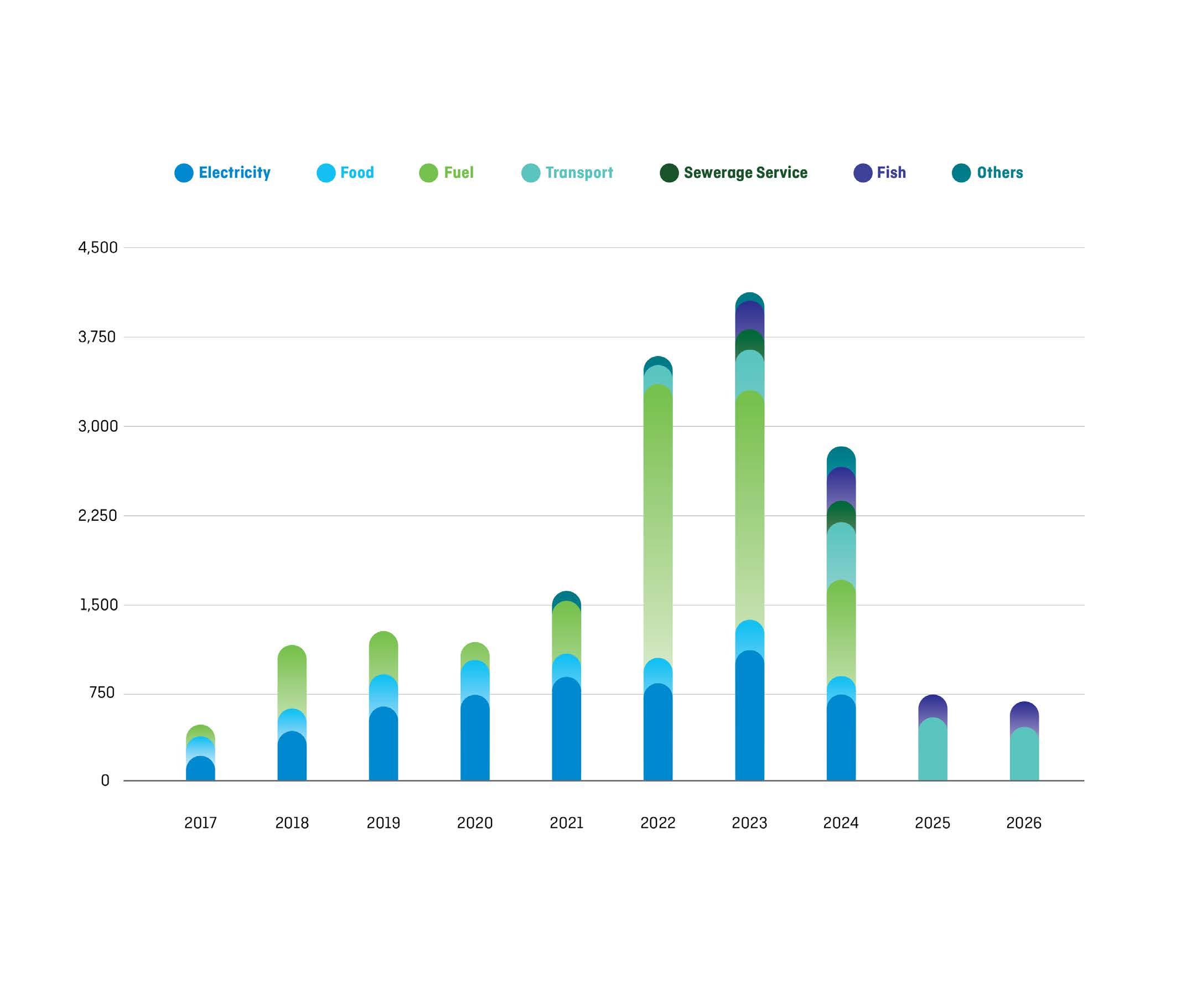

2024 Expenditure on Indirect Subsidies

It’s not just the health sector; the story of subsiding utilities follows a similar plot. The government spends around MVR 100 million a year from state funds to provide affordable electricity to the people. STELCO does not differentiate between the rich and poor when providing these subsidised services.

Barring the tourism industry, the fishing industry in the Maldives is the largest. However, it seems that the government is spending on it a lot more than it’s generating income for the state.

Statistics show that the state spent MVR 215.8 million on fisheries last year, subsidising fuel and buying fish above market prices. The question is, how helpful have these subsidies been?

Gov’t allocates

MVR 215.8 m

in subsidies for fisheries sector in 2023

A big portion of the subsidies goes to businesses.

Boatmen reap the benefits of fuel subsidies. The subsidies given through MIFCO benefit these boatmen as well and only trickle down to some of the fishing crew. However, the truth is that most boats now employ a lot of migrant workers among their crew, funnelling these funds out of the country.

Food subsidies given indiscriminately follow the same storyline as well. The state spends millions on subsidising certain foods to make them affordable. While the state-owned STO takes the majority of these subsidies, the chunk taken by private businesses is not small either. The average citizen takes home the small amounts of subsidies given for staples such as rice, flour, and sugar. Many Maldivians do not consume the subsidised ordinary rice anymore; it is consumed

mostly by the migrant population, which greatly benefits from this particular government subsidy.

Talks of reforming government subsidies to benefit those in need are not new — and not just among disgruntled netizens but also on the floor of the parliament. However, the sad fact is that many parliamentarians are among the rich who are directly benefiting from government subsidies, and it is unlikely that such a reform will take root from the Majlis.

Indiscriminate subsidies are unfair to the many Maldivians already grappling with rising living costs, and subsidy reform should be a priority for a country currently experiencing a financial crisis.

The Maldives is an island nation comprising around two thousand islands in the Maldives; 200 are inhabited, and about 200 are home to resorts. With little to no other resources, tourism is the country’s no.1 industry, generating billions in revenue every year. However, the country’s rapid expansion of tourism has come to a crossroads with environmental conservation, and the future of the remaining 1,500 untouched islands remains uncertain. Will they be protected, or exploited?

The issue is particularly dire in Malé Atoll, where nearly every island, lagoon, and sandbank has been earmarked for industrial purposes, including resort development. The overexploitation has reached a point where local residents have few natural spaces left for recreational activities like picnics.

Ironically, an artificial picnic island for locals had to be created by dredging land.

Sadly, this pattern isn’t unique to Male’ Atoll. Similar situations are unfolding in Lhaviyani, Alif Alif, Alif Dhaal, and Vaavu atolls, where local communities are beginning to question the purported benefits of continuous resort development. The lack of employment opportunities for young people in the atolls and the job scarcity in the tourism industry are emerging as national concerns that demand immediate attention.

In Vaavu Atoll, where local tourism initiatives, including guesthouses, are gaining traction, the sale of islands and lagoons for resort development puts immense pressure on these fledgling businesses. The sale of a key sandbank and lagoon to Kaani Hotels for USD 729,000 (MVR 11.2 million) sparked outrage among local stakeholders. The Vaavu atoll council considers this lagoon crucial for local tourism, as it is one of the few remaining places where guesthouse operators can take tourists on excursions.

Thinadhoo Council President Shifag Hassan expressed his concern on social media, highlighting that this particular lagoon is the only one in the area unaffected by erosion.

He argued that the long-term benefits of protecting the lagoon far outweigh the shortterm financial gains from its sale. Keyodhoo MP Niushad Mohamed also opposed the sale, including many others who took to social media to express dissatisfaction.

Sham’oon Jaleel, a social media activist, echoed these sentiments, stating, “I do not support the conversion of guesthouses and local tourism beaches into resorts in the Atoll. The concerns of the Atoll Council, island councils, and guesthouse business owners should not be overlooked. Resort tourism should not hinder the operations of rural guesthouses. Guesthouse tourism is more closely tied to individual wealth than resort tourism.”

Source: Ministry of Tourism

The tourism sector is now calling for an immediate halt of new resort developments to safeguard Maldives’ vital natural spaces. According to Amjad Thaufeeg, Commercial Director of Kuda Villingili Resort, the Maldives is already developing enough resort beds to meet the demand for the next decade. “We should now focus on increasing resort occupancy and boosting profitability rather than expanding the number of resorts,» he said. Taufeeg also stressed the importance of protecting the natural environment and considering alternative uses for islands, such as education and agriculture.

The Maldives has set an ambitious target of reaching 100,000 beds in the next ten years, which would require attracting at least five million tourists annually. This goal would necessitate

significant infrastructure expansion, including developing new airports, increasing airline routes, and boosting tourism promotion efforts. However, many in the industry argue that these developments must be balanced with the need to preserve the country’s natural beauty.

Industry experts warn that the unplanned allocation of islands for industrial use could irreversibly damage the natural landscapes that draw tourists to the Maldives in the first place. The tourism sector is therefore pleading with the government to halt the construction of resorts on all untouched islands, lagoons, and sandbanks, emphasising that the long-term benefits of preservation far outweigh the immediate financial returns from development.

The Maldives is struggling with debt sustainability. The state budget is severely constrained by the need to service significant loans accrued by previous administrations. In its latest report, the World Bank advised the Maldives to implement spending cuts, reprioritise public spending, and improve revenue mobilisation.

Consequently, the government has suspended projects from the previous administration and decided not to commence any new projects that have not started yet. The Ministry of Construction & Infrastructure has directed the Maldives Transport and Contracting Company (MTCC) to re-prioritise its projects, resulting in 60 projects temporarily suspended and 17 already halted.

Stalled Projects and Economic Burden Financial Losses, Mismanagement, and Increased Cost

The current administration now faces the formidable challenge of either continuing or restarting numerous projects started by its predecessor. However, the Maldives’ current economic situation presents substantial obstacles with rising public debt and the risk of defaulting on loans.

The Maldives is struggling with debt sustainability. The state budget is severely constrained by the need to service significant loans accrued by previous administrations. In its latest report, the World Bank advised the Maldives to implement spending cuts, reprioritise public spending, and improve revenue mobilisation.

Consequently, the government has suspended projects from the previous administration and decided not to commence any new projects that have not started yet. The Ministry of Construction & Infrastructure has directed the Maldives Transport and Contracting Company (MTCC) to re-prioritise its projects, resulting in 60 projects temporarily suspended and 17 already halted.

Aside from delaying development, the suspension of these projects further exacerbates the Maldives current financial situation by incurring additional costs for the state. Extended project timelines increase expenses for all parties involved, including government-owned entities such as MTCC, STELCO, and MWSC.

Significant financial losses will soon follow, and private companies may potentially demand substantial compensation for halted contracts.

Inadequate budgeting and improper planning lie at the root of these delays. Many were announced for political popularity without the necessary resources to complete them, often relying on loans.

Similarly, projects expected to span three years were often only budgeted for the first year, leading to delays once funds were exhausted. For example, several projects entrusted to the RDC experienced significant delays or were halted entirely. Road construction in islands like

Hinnavaru has ceased, with MRDC employees remaining on payroll despite the lack of progress. Additionally, a housing project managed by a private company has stalled due to insufficient funds, exacerbating costs.

Furthermore, several projects were launched without public knowledge. The Parliament›s Finance Committee is reviewing these issues, revealing numerous projects that received significant advance payments but failed to progress. For example, MVR 45 million was spent on constructing a power plant in Kulhudhuhfushi, yet only the structure›s four walls remain, according to Environment Minister Thorig Ibrahim. Additionally, the Finance Committee discovered that former MP Ali Hameed›s company received MVR 44 million in two instalments for a 10-storey building in Hulhumale, which has yet to materialise.

The delays and mismanagement of these projects could cost the state billions. Financing multiple projects through large loans, combined with the failure to pay private contractors, will force the state to deal with significant financial losses.

Many of these projects did not adequately consider the needs of the population, benefiting only a few while neglecting vital infrastructure. As a result, public welfare has suffered, leading to increased migration to urban areas and higher crime rates due to limited opportunities.

The public is left wondering why their needs aren’t being met while the state budget is exploited under various pretexts, burdening the country with debt. If the Maldives truly seeks to resolve these issues, it is essential that future projects are properly planned and focused on genuine public needs. Without better management and transparency, development efforts are proving to be a costly burden rather than a pathway to progress.

Land reclamation in the Maldives has become more than just a construction endeavour; it’s a political statement. For decades, Maldivian leaders have touted these ambitious projects as solutions to housing shortages and economic woes. From the bold moves of former President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom to the continued reclamation under successive administrations, these initiatives were often paraded as evidence of progressive governance. Yet, despite the monumental investments, the real impact on communities and the economy is underwhelming.

The grand vision of these projects was to transform barren stretches into thriving hubs of activity. The reality, however, tells a different story. While areas like Hulhumale have seen some success, many other reclaimed lands remain desolate, with little to show for the billions of Rufiya poured into them.

Construction and Infrastructure Minister Dr Abdulla Muthalib recently exposed a striking fact: of the 190 hectares of reclaimed land, only a tiny fraction is actively used. The city›s council is still drafting a land-use plan—a critical step often overlooked before embarking on such colossal projects. Mutalib›s remarks underscore a recurring flaw: reclamation efforts frequently advance without a clear strategy, leaving vast tracts of land without any immediate use.

This lack of foresight has resulted in abandoned sites littered with construction debris and idle machinery. The promised economic benefits have often failed to materialise due to inadequate infrastructure—basic necessities like electricity and water remain inconsistent or absent.

Critics suggest that these reclamation ventures are driven more by political aspirations than genuine developmental needs. The allure of new land is frequently leveraged as a campaign promise, only for the land to remain vacant once reclaimed. The result? Some plots have stayed empty for up to twenty years, rendering the expenditure a stark waste of public funds.

During discussions on the Infrastructure Planning and Management Bill, Kudahuvadhoo MP Hussain Hameed highlighted a critical issue: the absence of strategic infrastructure planning has exacerbated rural depopulation, pushing more people towards urban areas. Hameed argued that effective development of reclaimed lands could have mitigated this trend, offering a lifeline to struggling rural communities.

In the city, especially during President Abdulla Yameen ’s tenure, large-scale reclamation was intended to relocate industrial activities. Yet, much of this land ended up in private hands, with scant benefit to the public at large.

Recent reclamation projects near Male’ continue to reflect these persistent challenges. Initially meant for housing, much of this land is now being repurposed for commercial ventures like guest houses, deviating significantly from the original intent.

Overall, the billions of Rufiya invested in land reclamation projects have frequently failed to deliver on their promises. These efforts have left many areas barren and underdeveloped without a coherent and effective land-use strategy. The outcome is a sobering reminder of the cost of political theatre—valuable resources squandered and the pressing needs of the Maldivian people left unmet.

Since ancient times, fishing has been the lifeblood of Maldivians. Yet, in recent times, fishermen find themselves struggling to make ends meet. In early June, tensions flared outside Hulhumale’ Kanneli Jetty. Around 50 fishing vessels gathered to protest against unpaid wages, escalating fuel prices, and the government’s plans to issue long-line fishing permits. By this time, fishermen had not been paid for over a month, and delayed payments had accumulated to MVR 80 million (USD 5.2 million).

Protestors voiced their concerns to local media, highlighting their significant hardships. Some fishermen have fallen deeply into debt, unable to repay their loans, while others struggle to meet daily living expenses.

Government Intervention

In efforts to address the unrest, the government reduced diesel prices, but the fishermen’s frustrations ran deeper than the cost of fuel. Their main concern was the inconsistent payment for their hard-earned catches—a lifeline they could no longer count on.

«Whether it›s MVR 20 or 25 per kilogram, it doesn›t matter as much as being paid on time,» said one fisherman. «I haven›t received any payment for three or four months. I would rather receive a lower price regularly than wait indefinitely for a higher one.»

This protest was the second of its kind this year.

Back in February, fishermen in Gaafu Alif atoll

Kooddoo staged a similar demonstration against MIFCO’s non-payment, blocking 15 fishing boats from entering the island’s fish processing factory. According to the government, MVR 190 million was owed to fishermen then.

When Fisheries Minister Ahmed Shiyam visited the island to address the unrest, he promised MVR 280 million in outstanding payments would be cleared by March 5 . But as Ramadan approached, the fishermen were desperate, and despite assurances, many were not paid until July, long after Eid celebrations had come and gone.

MIFCO’s Persistent Debt

At the heart of this issue is the Maldives Industries Fisheries Company (MIFCO), a state-owned company perpetually caught in a cycle of debt. Often unable to pay fishermen on time, MIFCO’s expenses continually outpace its income, pushing it closer to financial ruin. In 2016 , with debts exceeding MVR 300 million, MIFCO was placed under the State Trading Organisation (STO) as a last-ditch effort to stave off bankruptcy. A year later, the government injected a staggering MVR 580 million into the company to cover its debts to fishermen.

However, even with government support, MIFCO’s financial health remains precarious. In 2019 STO reported that MIFCO’s revenue from fisheries had risen slightly to MVR 1.4 billion, a modest 4 % increase from the previous year. Yet, despite receiving government grants exceeding MVR 223 million, the company still reported a loss of MVR 116 million for that year—a slight improvement from the previous year’s loss of nearly MVR 200 million.

The situation only gets worse when you dig into the numbers. The Auditor General ’s Office reported that between 2016 and 2021 , MIFCO racked up a gross loss of USD 16 million and a net loss of USD 65 million. By 2021 , the company had accumulated losses of USD 84 million, with debts far exceeding its assets. Poor fish quality and rejected shipments alone cost MIFCO MVR 48 million annually from 2016 to 2021 , adding up to a total loss of MVR 290 million over five years.

The reasons behind MIFCO’s financial woes are manifold: high machinery costs due to irregular maintenance, excessive overheads from politically motivated recruitment, and inflated market rates for fish have left MIFCO teetering on the edge of bankruptcy time and time again.

As the year 2024 unfolds, the Maldives finds itself teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. Experts have warned the Maldives is at increasing risk of default, sparking a debate on who is responsible for the country’s debt dilemma.

Despite being unprecedented, the ongoing crisis is not unexpected. The Maldives debt struggles stem from decades of unchecked government spending, from former President Maumoon’s era to President Solih’s tenure. Whether the Maldives will go bankrupt is no longer a matter of “if” but “when.”

A Legacy of Growing Debt

When President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom left office in 2008 , the Maldives› debt stood at approximately MVR 9.2 billion. Then came President Mohamed Nasheed and President Mohamed Waheed, who added another MVR 18.5 billion to the tab, bringing the total to MVR 27.7 billion by the end of their terms. By 2018 as President Abdulla Yamee ’s administration neared its conclusion, the debt had soared to a staggering MVR 60 billion.

But the most significant surge came under President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih. By the time his tenure ended, government debt had skyrocketed to MVR 124 billion—an increase averaging MVR 2 billion every month he was in power. Now, with President Mohamed Muizzu at the helm, the nation continues to spend more than it earns. Upon taking office, President Muizzu prioritised securing political support, leading to a surge in State and Deputy Ministers. This bloated bureaucracy has only added to the financial strain, with state-owned enterprises also seeing a spike in employment.

Economists have long warned that continuing to borrow without curbing spending could drive the Maldives into bankruptcy. But the lure of political gain has consistently outweighed fiscal prudence, with successive governments prioritising shortterm wins over long-term sustainability.

The financial outlook for the Maldives is increasingly grim. The government faces a daunting schedule of debt repayments, including USD 50 million in sovereign debt due by the last quarter of 2024 . On top of this, another USD 64 million in public debt looms large. The Sovereign Development Fund, with its USD 65 million, offers some relief, but it›s a drop in the ocean compared to what lies ahead. By 2025 , the Maldives will need to come up with USD 557 million to service its debt—a figure that will surge past USD 1 billion in 2026 , largely due to a massive USD 500 million sukuk.

These obligations are exacerbated by the country›s persistent current account deficit, which reflects the gap between what the Maldives earns from exports and what it spends on imports. As a nation heavily reliant on imports, the Maldives has struggled with chronic shortages of US dollars. This scarcity has further strained the country ’s ability to maintain currency stability and meet its international debt commitments.

Saving the Maldives Requires Reducing Government Expenditure

When President Maumoon left office in 2008 , the Maldives , debt stood at approximately MVR 9.2 billion. Then came President Mohamed Nasheed and President Mohamed Waheed, who added another MVR 18.5 billion to the tab, bringing the total to MVR 27.7 billion by the end of their terms. By 2018 , as President Abdulla Yameen›s administration neared its conclusion, the debt had soared to a staggering MVR 60 billion.

But the most significant surge came under President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih. By the time his tenure ended, government debt had skyrocketed to MVR 124 billion—an increase averaging MVR 2 billion every month he was in power.

Now, with President Mohamed Muizzu at the helm, the nation continues to spend more than it earns. Upon taking office, President Muizzu prioritised securing political support, leading to a surge in State and Deputy Ministers. This bloated bureaucracy has only added to the financial strain, with state-owned enterprises also seeing a spike in employment.

Economists have long warned that continuing to borrow without curbing spending could drive the Maldives into bankruptcy. But the lure of political gain has consistently outweighed fiscal prudence, with successive governments prioritising shortterm wins over long-term sustainability.

Source: Maldives Monetary Authority (MMA)

Maldives State Debt over the Presidencies

Source: Maldives Monetary Authority (MMA)

Gov’t Revenue & Expenditure over the Presidencies

Fish Purchases Over the Years

According to laws crafted by the parliament, any parliament member to complete one term is entitled to receive 30 per cent of their salary once they turn 55 years of age. Taking into account the current salary of parliamentarians, this figure stands at MVR 18K a month. And should they complete two terms, the percentage will reach up to 45% of their salary, which is MVR 27K.

In addition to these allowances, each member receives official perks such as a passport and medical insurance. With every new parliament, the list of entitled members grows, intensifying the burden on state resources.

The current parliament, with 93 members recently elected, ensures future increases in allowance payouts.

Public discontent has grown over the perceived disparity between these allowances and the revenue the state receives. Many call for reforms, urging new members to consider reducing or stabilising these financial benefits. However, such changes require political will.

The question is, can the government, holding an enormous majority in parliament, dare to undertake this to meet the people’s expectations?

Salaries of Presidents and VPs: Burden on State Finances

Adding to the dialogue of retirement allowances are also the discontented voices of those opposing salary increase of Presidents and the Vice Presidents.

Some argue that those who have completed their five-year term — Presidents, VPs, or parliamentarians — should receive retirement allowances like any other position, following the same guidelines.

Source: Ministry of Finance

Currently, the average person receives an MVR 5,000 allowance upon reaching retirement age. This amount does not increase for those who have served longer. Many believe that granting substantial allowances to specific individuals is unfair. Fair Retirement Benefits to Honouring Years of Service

It›s reasonable to provide retirees with allowances that reflect their years of service to the country. However, there are calls for a reduction in allowances for members of parliament and a review of allowances for former judges and presidents. Some argue that while allowances for judges have increased, they may not align with the country ’s economic situation

Concerns have been voiced on social media about the disparity between retirement allowances and the average salaries of working citizens. Critics also highlight the perceived injustice

in differential benefits based on occupation, pointing to disparities in housing, healthcare, and other privileges, particularly for police, military personnel, and judges upon retirement.

Public dissatisfaction extends to benefits afforded to former presidents, whose expenditures are already heavily supported by the state budget. While privileges and security are justified for expresidents, they should not unduly burden the economy or perpetuate inequality. Transparency regarding the expenses of former presidents is

also lacking, raising concerns about fairness. Many view the generous retirement allowances for former presidents, MPs, judges, police, and military personnel as a drain on state resources. Moreover, the ability of retirees to pursue additional employment while enjoying housing and medical benefits further exacerbates public discontent.

When the Maldives gained independence in 1965, Israel was among the first nations to recognise our sovereignty. In return, the Maldives also recognised Israel as an independent state. Today, such strong support for Israel would be unthinkable in the Maldives, given our current awareness of the Israeli occupation of Gaza and the plight of the Palestinian people.

Several factors contributed to this early recognition, but experts agree the primary reason was Israeli support’s crucial role in securing the Maldives’ independence. At the time, India and Sri Lanka were negotiating with the British about potentially incorporating the Maldives into their territories. To ensure full sovereignty, the Maldives struck a covert deal with influential Israeli lobbyists among the British, leveraging their influence to advance Maldivian interests.

Maumoon’s Presidency and the PLO

Maldivian leaders of the era believed that without the Israeli deal, the Maldives might not have achieved independence and could have fallen under Indian or Sri Lankan control.

Ironically, Maumoon ’s regime, not known for its humanitarian values, took a more confrontational approach by severing diplomatic ties with Israel and recognising the Palestinian state.

In July 1984 , Yasser Arafat was welcomed to the Maldives, and soon after, the country indirectly supported PLO activities, including hosting a PLO-operated airline called Maldives Airlines. However, the airline ceased operations after a significant boycott movement in the German press accused the Maldives of promoting antiSemitic tourism to benefit the PLO. Consequently, the Maldives adopted a more moderate policy to safeguard its tourism sector.

Beyond Religion: The Financial Underpinnings of the Israel-Palestine Conflict

Supporting Palestine proves to be challenging, particularly for small island nations like the Maldives, which have limited influence in global affairs. On the other hand, Israel has effectively leveraged financial interests to their advantage for decades.

Recently, the Maldives proposed a ban on Israeli tourists entering the country. Despite strong public support, the ban could potentially damage the country s reputation as a welcoming destination and lead to unwarranted perceptions of antisemitism or religious extremism. The move sparked both praise and backlash from the international community, including a U.S. congressman s proposal to cut off American aid to the Maldives. Nonetheless, the Maldivian public

remains resilient, showing unwavering solidarity with Palestine through fundraising initiatives and planned nationwide rallies.

The ongoing Palestinian conflict extends beyond religious differences and is deeply entangled with economic and strategic interests. The Leviathan gas field, discovered in 2010 and located 130 kilometres west of Haifa, is a major natural resource capable of producing millions of barrels of oil. In 2020 , Israel signed billion-dollar deals with Jordan and Egypt, which have been criticised for diverting revenue from Palestine.

Israel s pursuit of energy dominance has raised questions about the true motives behind its military actions in Gaza, suggesting these actions might be less about defending against Hamas and more about establishing control over the strategically crucial Gaza Strip, which offers direct access to the Mediterranean Sea and holds valuable natural oil reserves.

In today ’s geopolitical landscape, oil and natural gas are central to political alliances and economic interdependence. As trade and bilateral ties develop between Middle Eastern nations and Israel, the Palestinian cause is effectively thrown to the side.

Meanwhile, businessmen are lining their pockets with war profiteering. Stocks of major weapons contractors immediately rose by 7 % after Hamas ’s October 7 attack. Barely two weeks later, during earnings calls, discussions among Wall Street players revolved around the increasing demand for weapons and opportunities for financial gains from the conflict.

The silence of many countries, especially in the Middle East, regarding the Palestinian genocide is perplexing to many Maldivians. What remains alarmingly clear to everyone is the ongoing gross violence against innocent Palestinians. As the international community continues to grapple with this issue, the plight of the Palestinian people remains a stark reminder of the ongoing struggle for justice and self-determination.

The silence of many nations, particularly in the Middle East, reflects the complex interplay of historical animosities, economic interests, and shifting political alliances. In this intricate web of global politics, the call for an independent Palestinian state remains a complicated and very crucial issue.

Over MVR 44 Million Disbursed to Political Parties this Year

Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP)

Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM)

People’s National Congress (PNC)

Jumhooree Party (JP)

Adhaalath Party (AP)

Maldives Development Alliace (MDA)

Source: Elections Commision of Maldives

In late August, social media erupted with allegations against a Bangladeshi man for killing cats and using their meat in various snack products, such as burgers and submarines often sold in local shops. Police arrested the man soon after, and the Ministry of Homeland Security and Technology revealed that efforts were underway to send samples taken from the residence of 32-year-old Arfat Hossain to international laboratories for confirmation. This disturbing incident sparked widespread outrage and left many questioning the safety and origins of their food.

In response to reports, law enforcement and immigration authorities intensified efforts to clamp down on illegal immigrants following several reports of unsanitary food preparation practices. Photographs released by the authorities reveal shocking conditions, with food being prepared in filthy environments—close to toilets, on dirty tiles, and exposed to animals like cats and rodents.

These revelations sparked outrage, but similar concerns have been raised before. Past reports about unsanitary food preparation practices have emerged, but often without any significant action being taken.

There have been allegations that cooking oil and other ingredients are obtained from questionable sources, including beach waste and resort refuse. Despite these troubling claims, authorities have taken little action until now. The current administration›s emphasis on public health has again brought these issues to the forefront, emphasising the need for more effective oversight.

The alleged use of cat meat and reports of other questionable practices—such as using waste oil from beaches and resorts— has left many parents and consumers worried about the safety of popular snacks. These items, often purchased for children to eat during school intervals, are now under scrutiny.

«It s hard to prepare something fresh for my child every morning before work, so I usually buy snacks from a nearby shop. But I stopped buying them when one day, I found insects in the food box,» said a parent living in Male , expressing concern over the cleanliness of local food outlets.

The issue extends beyond street vendors. Many small coffee shops and snack stalls, particularly in areas like Male› and Hulhumale›, are reportedly run by foreigners, some of whom are illegal immigrants. These businesses often cut corners to maximise profits, sometimes at the expense of food safety.

The increasing number of small food businesses run by foreigners, many of whom operate illegally, has raised significant concerns. Reports suggest that some of these vendors may use cat meat to cut costs, further undermining food safety standards.

As these issues come to light, more people are rethinking their reliance on street food and quick snacks. The situation underscores the need for stricter food safety regulations and more vigilant enforcement to protect public health.

This crisis is not a sudden development but the result of years of neglect. The failure of authorities, including the Maldives Food and Drug Authority and the Health Protection Agency, to address these issues has led to the current situation. It also reflects a broader indifference and lack of accountability, both from the agencies responsible for safeguarding public health and from the public itself.

As investigations continue, the public must remain vigilant about the food they consume and demand greater transparency and accountability from those responsible for ensuring food safety in the country.

Capital punishment in the Maldives has had a de facto moratorium for over 60 years, with the last execution taking place in the early 1950s. Despite numerous death sentences issued by the courts since then, none have been carried out. In what seems to be a purely symbolic gesture, individuals convicted of serious crimes, such as violent attacks, have received death sentences, but these were later commuted to 25 years in prison, and they were eventually released.

The debate over the death penalty has reignited following a proposed amendment to the Narcotic Drugs Act. The draft amendment suggests implementing the death penalty for those found guilty of smuggling over 500 grams of drugs into the country to target first-time offences in drug trafficking. This change represents a significant change from the previous maximum penalty of life imprisonment, set at 25 years.

Historically, the death penalty has been a subject of discussion among various Maldivian governments. According to Maldivian law, the government can only enforce the death penalty following a final ruling by the Supreme Court. Despite some prisoners reaching this stage, the government has been reluctant to carry out the sentences.

The death penalty came closest to implementation during former President Abdullah Yameen ’s administration. A 2014 Cabinet meeting outlined steps for implementation, including developing execution procedures and considering lethal injection as the method of execution. His Home Minister, Umar Naseer, championed the death penalty and made substantial preparations for its enforcement. However, these efforts were halted with Naseer›s resignation, and Yameen ’s successor, Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, distanced himself from the death penalty policy.

The current government›s stance on the death penalty remains ambiguous. Nonetheless, in a press conference last year, Minister of Homeland Security and Technology Ali Ihusaan indicated that President Mohamed Muizzu›s government would review the implementation of the death penalty after making necessary considerations.

Currently, the Act lists 139 drugs, but there are concerns about substances not included in this schedule. The draft amendment proposes that smuggling quantities exceeding 500 grams of any drug could warrant the death penalty. Yet, it remains unclear whether the list of controlled substances will be updated accordingly.

Critics of the death penalty have raised significant concerns about the gaps in the judicial system and the risk of wrongful convictions. Human rights groups and the UN Human Rights Committee have expressed opposition to the death penalty, highlighting the dangers of executing individuals under an imperfect judicial system. Notably, few countries actively enforce the death penalty for drug-related offences, with notable exceptions including China, Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Singapore.

The Maldives has considerable public and political discourse on the death penalty, but the practicalities of enforcement remain uncertain. The complexities of the judicial and political landscape suggest that even if the death penalty for drug smugglers is written into law, its actual implementation may remain largely symbolic.

The rising rates of obesity and related health problems among the Maldivian populace are an increasing public health concern. Poor lifestyle choices, including excessive consumption of sugary foods and lack of physical activity, have led to deteriorating mental health and a rise in drug addiction. Despite these alarming trends, the government continues spending hundreds of millions on sugar subsidies yearly, a policy some critics call dangerously misguided.

Research conducted by the Maldives National University (MNU), in collaboration with the Health Protection Agency (HPA) and the World Health Organization (WHO), revealed that by 2022 , over 3,000 individuals aged 39 -15 in the Maldives had dangerously high levels of blood sugar and cholesterol. Health experts attribute these alarming statistics to poor diets and sedentary lifestyles.

Processed sugars are associated with a myriad of health risks, including obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome. High sugar intake is linked to heart disease, elevated cholesterol levels, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Additionally, sugar contributes to dental problems and can exacerbate mental health issues such as depression. There is also evidence suggesting that excessive sugar consumption may increase the risk of cancer by creating an environment conducive to the growth of cancer cells.

Speaking at a panel discussion on the World Bank’s “Scaling Back and Rebuilding Buffers Report”, Senior Economist Hideki Higashi highlighted that the Maldives has the highest proportion of obese individuals in the region. The increasing prevalence of obesity is evident in everyday life and poses a significant national concern.

One of the primary reasons for excessive sugar consumption is its affordability. Sugar is heavily subsidised in the Maldives, sold at just MVR 5 per kilogram, compared to the actual market price of MVR 17 per kilogram. Critics argue that this subsidy, which costs the government MVR 12 per kilogram, should be abolished immediately.

Over the past five years, the government has spent an average of MVR 300 -250 million annually on sugar subsidies. These funds could be redirected to other areas of the economy, particularly healthcare, to mitigate the adverse effects of excessive sugar consumption.

Without immediate action to curb these trends, the Maldives risks becoming a nation plagued by chronic health issues, reliant on foreign intervention to manage and sustain its healthcare system.

Throughout history, societies have encountered crises that threaten their very essence. In the 19th century, the British used opium as a weapon to destabilise China, leading to widespread economic and social turmoil. The stark lesson from this period — the destructive power of addiction — serves as a cautionary tale. Today, the Maldives is grappling with its own form of societal decay, driven by rampant gambling and excessive indulgence among its youth.

According to statistics, 19% of the Maldives’ youth are not engaged in any form of employment. Despite lacking formal employment, many young people flaunt a luxurious lifestyle. Boasting expensive cars, high-end gadgets, and frequent overseas holidays, one can’t help but wonder: how do they afford it?

The combination of limited opportunities and resources in the Maldives, alongside the addictive nature of gambling, has led to a significant rise in its prevalence among the youth. Cafés and social spaces have become hotspots for these activities, where young people spend extensive periods engaging in online casino games and gambling. The economic implications are severe, with some individuals amassing substantial sums through these pursuits, sometimes facilitated by others who manage gambling tables.

Recent revelations have highlighted the extent of this issue, including reports of substantial gambling money found in the accounts of correctional officers, which suggests a broader network facilitating these activities. Meanwhile, the rapid spread of gambling raises concerns about its impact on the country’s workforce and economy.

Gambling addiction does not only affect individuals financially; it also has profound social implications. Relationships are often strained as gambling problems lead to secrecy, dishonesty, and conflicts within families. The social fabric of the community is weakened as gambling becomes more entrenched in the daily lives of young people.

Furthermore, the normalisation of gambling can lead to a shift in societal values. Pursuing quick wealth and the thrill of risk-taking can overshadow the importance of stable employment and responsible behaviour, undermining the work ethic and stability crucial for the country›s long-term prosperity.

The Financial Fallout

The economic impact of gambling is already becoming apparent. Many young people, drawn into the world of online gambling and casino games, experience severe financial strain. The temptation of easy money often leads to substantial losses, resulting in debt and financial instability. The fact that

gambling winnings are frequently used to sustain further gambling adds fuel to the fire, creating a vicious cycle.