8 minute read

This Year, Next Year, Sometime Never?

Geoff Royston

The kwik brown foks jumpd ovr the lazee dog. That could be correct spelling - if the forecasts made at the dawn of the twentieth century by the engineer John Elfreth Watkins had been right. In 1900 he made a number of predictions, including that by the 2000s, English language will be condensed, with “no C, X, or Q in our everyday alphabet.”

We will come back later to foxes and dogs (or rather, hedgehogs), and indeed to John Watkins’ forecasts. Meantime, let’s look at problems of prediction.

CRYSTAL BALLS? There is no shortage of forecasts that have been spectacularly wrong. Take for example, the world of information technology. In 1943 the president of IBM predicted a world market "for maybe five computers"; in 1977 the head of the DEC (Digital Equipment Corporation) said “there is no reason why anyone would want a computer in their home”; and in 2007 the CEO of Microsoft said “there’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share”.

So, is forecasting just a load of crystal balls? Before looking into some empirical evidence, let’s consider first why prediction is difficult. Apart from the obvious factor of ignorance – lack of knowledge or understanding of (or disregard for) crucial elements of a situation - two key factors are time and complexity. Our ability to see into the future is generally less the further ahead we are trying to look and the greater the complexity of the system we are considering. Some real-world systems obey simple laws and are highly predictable – for example Edmund Halley in 1705 accurately foretold the return 53 years later of the comet that accordingly now bears his name. Many others however (not least those where human behaviour is involved – Newton, who lost a fortune in the South Sea Bubble of 1720, is quoted as saying that “I can calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people”) feature important non-linearities, e.g. from feedback effects, where initially imperceptible fluctuations can quickly amplify over time and introduce ever-growing errors into forecasts; the so-called butterfly effect. However precise our current knowledge of such complex dynamic systems, these compounding errors will eventually swamp our ability to predict their future.

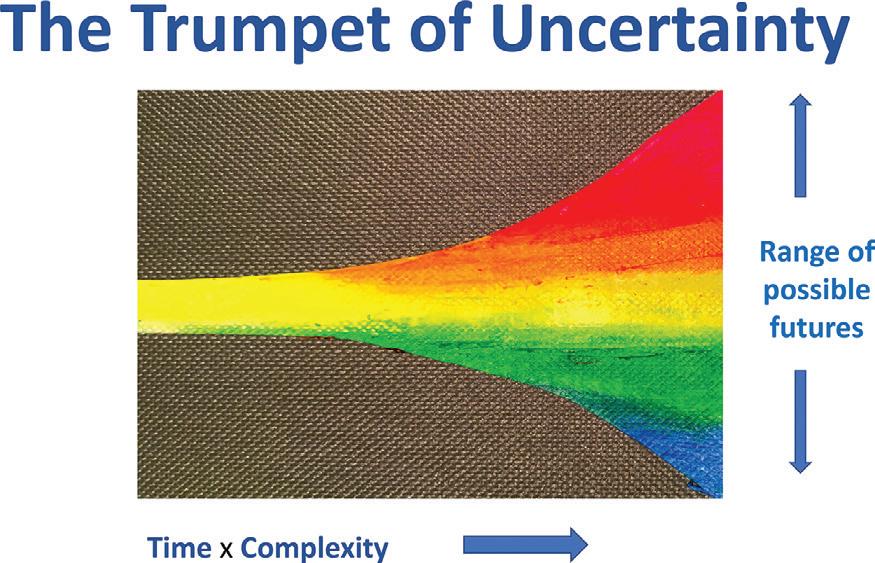

THE TRUMPET OF UNCERTAINTY This problem can be viewed as the trumpet of uncertainty, see Figure 1, where uncertainty is visualised as proportional to the product of time and complexity. The trumpet is narrow for the highly predictable (e.g. clocks, planetary motions, tomorrow’s weather), wide for the highly unpredictable (e.g. the weather in a month’s time, stock market fluctuations, revolutions) and in between for things in the middle (e.g. UK birth rate ten years from now, the rise and fall of an epidemic, the extent of climate change).

FIGURE 1 THE TRUMPET OF UNCERTAINTY © Geoff Royston

Can we learn to blow the trumpet of uncertainty? That could be the leitmotif for a widely praised book; Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, written by Philip Tetlock with co-author Dan Gardner.

FOXES AND HEDGEHOGS Tetlock wanted to test the accuracy of experts’ predictions. So he asked several hundred of them to make forecasts in areas like elections, the economy and so on and then looked (over a period of 20 years!) at the results. The experts on average scored about as well as would a dart throwing chimpanzee!

So, forecasting in such areas is for the deluded, case closed? Far from it. First, many of the predictions requested were near, or even in, the zone of the unpredictable, at least for far ahead. Second, note the word “average”; experts’ forecasting skills were not all the same. Tetlock found two groups in particular, which he termed “hedgehogs” and “foxes”, (after the words of the Greek poet Archilocus, “the fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing”). Tetlock’s hedgehogs were the one-track thinkers who tried to fit facts to their preconceptions; his foxes were those who used a range of analytical approaches, considered matters from several different perspectives and used a variety of sources of information. Hedgehogs were confident in their forecasts - but their performance was (slightly) worse than random guessing! Foxes were less sure of themselves but they beat the hedgehogs, scoring (a bit) above chance levels.

Tetlock then followed up his original experiment with an even larger one involving 20,000 interested members of the public making forecasts. He found that the predictions of his volunteers were better – and with practice, became increasingly so - than those of control groups of experts. And some forecasters did much, much, better than average (and this was not a fluke – their performance was sustained); these were the superforecasters. They could forecast 300 days ahead as successfully as the other volunteers managed in looking ahead just 100 days.

SUPERTHINKING Tetlock found that his superforecasters used ways of thinking that built on the “fox-like” attributes mentioned above. His book lists ten of these; here are my summaries of three of them.

Triage. Decide if the question is in the highly predictable, highly unpredictable or in-between region, and devote most of your forecasting efforts to ones in that middle

“Goldilocks” zone.

“Fermi-ise”. (After the “back-of-the envelope” estimation approach of the nuclear physicist Enrico Fermi.)

Break down difficult forecasting questions into their determining components, think about these separately and then put that all back together to produce a combined result.

Think Bayesian. (Following the statistical philosophy of the Rev Thomas Bayes.) The basic approach is the same,

whether or not Bayes’ equations are deployed; start with a sensible baseline forecast (for example “no change” is generally a good starting point for predicting tomorrow’s weather). Adjust this – but not too much - for each piece of new evidence. These all seem sound advice to me – indeed I have discussed the last two, in different contexts, in previous articles in Impact. I would, however, add a couple of caveats to the recommendation on triage. First, many “highly predictable” forecasting questions, that yield to maths and modelling, need and are worth spending time on – else insurance analysts and actuaries would be out of a job. Second, while “highly unpredictable” forecasting questions take us into areas where trying to guess what will happen may be only for the brave or foolhardy, thinking about what could happen is always valuable – and is the realm where scenario thinking comes into its own - and can take us beyond forecasting: as Abraham Lincoln said, the best way of predicting the future is to create it!

SWALLOWS AND SWANS Tetlock’s advice prompts me to mention another renowned name in the forecasting world, Nate Silver, and his acclaimed (and recently updated) book on the art and science of prediction, The Signal and the Noise. In a world of ever-increasing amounts of data, much of which is irrelevant (or wrong), distinguishing the key information (the signal) from the rest (the noise) gets ever harder. (A positive diagnostic test has low predictive value if the true results are swamped in a sea of false positives.) A central theme of Silver’s book is the need to take a Bayesian perspective in forecasting, considering each piece of additional information within the wider context of the past evidence and understanding you already have about a situation. This reduces the risk of taking noise to be signal and overweighting a single piece of new evidence - one swallow does not make a summer.

However, an eye also needs to be kept out for abnormally strong evidence, especially in situations where past experience may not provide a good baseline for the future – the first sight of just one black swan did prove that not all swans are white. “The Signal and the Noise” notes that some of the worst forecasting errors, such as failures to anticipate the Pearl Harbour attack in 1941 and the New York Trade Centre bombings in 2001, came from not even considering some of the possibilities (Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns”,

or maybe “known unknowns” – possibilities we do not want to consider.)

NOT SO KWRKEE? I promised to return to John Watkins, to whom I rather dismissively referred earlier. To be fair, around half of the predictions he made back in 1900 for the 20th century were remarkably near the mark – for instance he foresaw live TV news, real-time whole-body medical imaging - and home delivery of ready-to-eat meals. And even his quirky alphabetic prophecy looks less off-target if you look at the condensed wording; 2NITE, GR8, WYSIWYG, …. often used in mobile phone text messaging. Maybe not quite as impressive a record as that of Edmund Halley, but then he was operating at the near-opposite end of the predictability spectrum. Watkins and Halley were clearly proficient players of the trumpet of uncertainty, but as Tetlock’s and Silver’s books indicate, all of us can improve our performance.

© Reproduced by permission of The Random House Group Ltd/Penguin Books Ltd.

Dr Geoff Royston is a former president of the OR Society and a former chair of the UK Government Operational Research Service. He was head of strategic analysis and operational research in the Department of Health for England, where for almost two decades he was the professional lead for a large group of health analysts.

© Crown Publishing Group/Penguin Random House