VERLAND O

WE ARE ADVENTURERS Constantly traveling. Testing and using gear in real-world situations. Gaining experience, which we readily share.

OUR RESUME

7 continents | 161 countries | 496 years combined experience

WE ONLY KNOW THINGS WHEN WE LIVE THEM

PUBLISHER AND CHAIRMAN Scott Brady

PRESIDENT AND DIRECTOR OF DESIGN Stephanie Brady

CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Christian Pelletier

CHIEF BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT OFFICER Brian McVickers

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Andre Racine

DIRECTOR OF EUROPEAN OPERATIONS Michael Brailey

EDITOR, OVERLAND JOURNAL Tena Overacker

CONSERVATION EDITOR Åsa Björklund

MEDICAL EDITOR Dr. Jon Solberg, MD, FAWM

ARCHAEOLOGY SENIOR EDITOR Bryon Bass, PhD

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Graeme Bell, Chris Cordes, S.K. Davis, Rocky Donati, Susan Dragoo, Ferenc Elekes, Nicolas Genoud, Richard Giordano, Thomas Henson, Lisa Thomas, Jaclyn Trop, Karin Marijke-Vis, Austin Vince

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER Bruce Dorn

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Eric Adams, Shirli Jade

Carswell, Nicolas Genoud, Richard Giordano, Simon Thomas, Coen Wubbels

COPY EDITOR Jacques Laliberté

TECHNICAL EDITOR Chris Ramm

CARTOGRAPHER David Medeiros

CONTACT

Overland Journal, 3035 N Tarra Ave, #1, Prescott, AZ 86301 service@overlandjournal.com, editor@overlandjournal.com, advertising@overlandjournal.com, 928-777-8567

MOVING?

Send address changes to service@overlandjournal.com. Include complete old address as well as new address. Allow two to four weeks for the change to become effective.

Overland Journal is not forwarded by the US Postal Service. It is the subscriber’s responsibility to inform Overland Journal of an address change.

Overland Journal is a trademark of Overland International, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Overland Journal is a wholly owned subsidiary of Overland International.

We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.

ROW 1

@wheretowillie

Don’t worry, everything is fine.

@danielm4wd

Classified Ad: Like new camper awning for sale, adaptable to any vehicle model. Other camping accessories are also available. #CampingRoom

@wolfpac_outdoors

Found this gem. It’s crazy to see in real life; the detail in @robinwilliams face is astounding.

ROW 2

@bikeexif

Dirty deeds done cheap: @purpose_built_moto just proved you don’t need to spend a fortune to build a fun scrambler. Keep an eye out for this cheeky little @sol_invictus_moto, [it’s the] nemesis in the upcoming @wideofthemarkmovie.

@benyamin_senkal

Our next trip will hopefully start in 12 days.

@utahjeeptrails

Took a quick trip to the moon the other day.

ROW 3

@cruiserrehab

Fun meetup with 40 friends and more at Catalina Coffee; went to my favorite photo spot.

@goldgravelandtravel

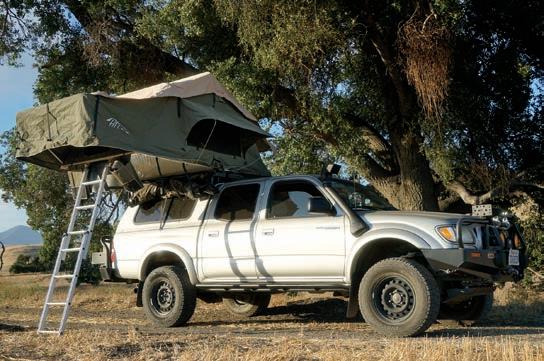

Every morning you wake to a beautiful sunrise. The warmth of the sun, birds singing, and aroma of pine trees tingle your senses. You are filled with joy, knowing that no mosquitos, ants, or spiders [are lying in wait]. It only rains lightly at bedtime and stops as soon as you enter dreamland. The mattress feels like a cloud, and it only gets cold and snows on Christmas. This, my friends, is rooftop tent living.

@busters_dad_ Helping daddy organize.

I found [the Summer 2020 issue in] my mailbox today. Why did it take 14 pages of ads to get to something interesting? I know advertising pays the bills, but I don’t have super deep pockets to afford nearly all of what you promote. The 500K vehicles can’t go where my humble 1982 Land Cruiser can go. Your publication has been interesting through the years, but I can’t see reading any more ads.

James Bingham

1982 Land Cruiser

RESPONSE FROM THE EDITOR:

In recent issues, we allowed for an increase in advertising due to demand. But we are also working at increasing content to offset it. The transition has not been as seamless as intended, but the difference should already be evident. Thank you for voicing your concerns.

I’m a charter member of your magazine and have enjoyed it since Spring 2007. You featured a camp pillow in the magazine, which I can’t seem to find. Said it was a staff favorite, partially inflatable. Can you point me to the specific magazine issue and page? [Sea to Summit Aeros Premium Pillow, page 109, Spring 2020] Thank you for producing such an awesome magazine. I have lived vicariously through you for years.

Ted Jones

1990 D90 by Arkonik 1997 Land Cruiser 1977 FJ40

LOOKING FORWARD

Overland Journal is, by far, my favorite magazine in the history of the world. [I’m a] longtime subscriber—love the summer isNOT

sue, read cover to cover in one day already. Keep doing what you’re doing because when the world opens back up, it’s going to need it.

Greg Clement from OutRise 2018 KTM 450

SHARE

Use #overlandjournal on Instagram or Facebook.

WHERE HAS YOUR OVERLAND JOURNAL BEEN?

Send us a photo, along with your name, the location, make/year of your vehicle, and a brief description. editor@overlandjournal.com

Jaclyn Trop is an award-winning journalist and automotive reporter, deciphering the world of sheet metal for the masses. She divides her time among Los Angeles, Detroit, and New York. She was awarded a KnightBagehot fellowship in business and economics reporting from Columbia University, where she also earned a master’s degree in journalism. Her byline has appeared in the New York Times, the New Yorker, Fortune, Vogue, Glamour, Newsweek, Fast Company, Forbes, Marie Claire, Men’s Health, Entrepreneur, Rolling Stone, Robb Report, Town & Country, U.S. News & World Report, and Refinery 29 among others. Jaclyn has reported from five continents and eaten ice cream in more than 50 countries. She serves as a US juror to the World Car Awards.

Shedding light on the obscure, especially at the juxtaposition of man and nature, drives Susan Dragoo to explore the historical treasures of the American Southwest. On wheels or afoot, an old trail and a camera are her key ingredients for a fulfilling adventure. A writer, photographer, and student of history since youth, Dragoo’s work is found in motorcycling, 4WD, hiking, and other travel publications, and her scenic photography in state park lodges and cabins in her home state of Oklahoma. Gallivanting in their Toyota “Tacoma GS” is a favorite pastime for Susan and husband, Bill, when they are not at home in Norman, Oklahoma, enjoying their family and running Dragoo Adventure Rider Training (DART).

Nicolas Genoud has always nourished a deep love for adventure, exploration, and wilderness, from descending the Yukon River in a kayak to multiple crossings of the Sahara. Born and raised in Switzerland, as a photographer, he first traveled the planet and shared his love for unspoiled nature through numerous publications and projects. Nicolas is the founder and managing director of Geko Expeditions, a company offering guided and self-drive 4x4 exploration trips to destinations such as Russia, Iceland, Africa, Mongolia, and Madagascar. Nicolas has set up and guided numerous expeditions since 2003, always with a mix of poetry and a touch of Swiss precision.

Originally a lawyer, Ferenc has lived in 7 different countries and traveled through 10 times more than that. Recently having left the corporate world in the City of London, during the last few years, he has been focusing on overlanding, where he can combine the two things he is most passionate about: vehicles and travel. Ferenc’s experience in overlanding comes from extensive trips on three different continents, with the latest being from Budapest to Singapore with a Land Cruiser 120 and a rooftop tent. He is blogging about his trips extensively. When not on the road, Ferenc lives with his travel companion, Evelin, in Budapest, Hungary.

Richard Giordano completed a 48,800kilometer overland journey from Vancouver, Canada, to Ushuaia, Argentina, with his wife, Ashley, in their well-loved but antiquated 1990 Toyota Pickup. On the zig-zag route south, they hiked craggy peaks in the Andes, discovered diverse cultures in 15 different countries, and filled their tummies with spicy ceviche, Baja fish tacos, and Argentinian Malbec. That trip catapulted Richard into a career as a freelance video producer, photographer, and writer. He has created commercials for Toyota Canada, is the lead photographer for Expedition Overland, and is always itching to hit the road and share his adventures. If you see Richard out in the wild, he’ll most likely have a coffee in one hand and a camera in the other.

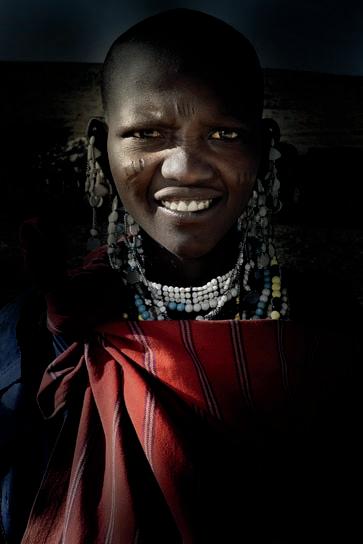

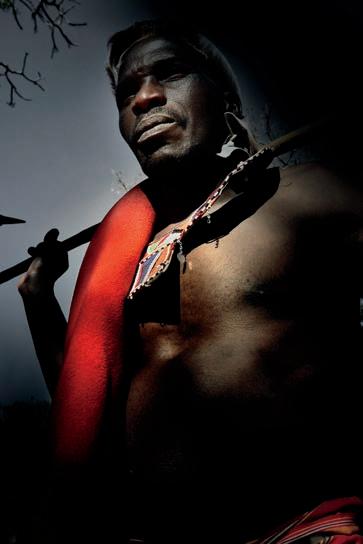

Born in South Africa, Shirli’s career and passion revolve around the African continent and its wildlife and cultures. She cut her teeth on advertising after art school and eventually moved into photography. She periodically packs her 2004 Defender, known affectionately as Tintin, and heads out to some remote locale to capture a library of images for her fine art portfolio. Recognized for her wildlife and landscape photography, Shirli is a driven conservationist and steward of Africa. She co-authored the book Africa’s Ultimate Safaris, an extraordinary photo journey through the continent, showcasing some of its most beautiful and wild destinations. She is currently working on a series of books that will take her into Africa once again, as well as Europe and the United States.

Rocky has a quirky sense of humor, the mouth of a sarcastic sailor, and talks supersonic fast. Her insatiable drive and knack for creative problem-solving meant a decade of spearheading high-level business strategies for the outdoor industry. Now she manages her own consulting firm, Donati Agency, but more often than not, elects to play hooky with her partner in crime and two Aussie pups. From wheeling to jet-setting out of a remote Park City chalet at 8,000 feet, she and her husband are constantly in search of the perfect pocket water for fly fishing. This decade, she’s embracing the hermit lifestyle, writing gibberish for hire, and renting out the adventurous getaway of your childhood dreams, The Treehouse Utah, on Airbnb.

Steven is a Utah native who, aside from riding motorbikes, runs a small business and raises a family just north of Salt Lake City. After living in the Middle East, Europe, Canada, and Colorado, he returned to Utah to put down roots. Both his fiction and non-fiction have been published in magazines and online, and he just released his adventure/crime novel, Big Hat, No Cattle, available in print or e-formats. When asked about his odd and magnetic sense of humor, he only replied, “I want to be the eccentric billionaire without the money.” Currently, Steven rides his R 1200 GS anywhere he can—and a lot of places where he shouldn’t.

I was born in London in 1965, saw Evel Knievel jump (and crash) at Wembley Stadium in 1975, and first heard “Strychnine,” by the Sonics, in 1985. I have been promoting DIY adventure and lo-fi fun ever since. As the digital age has dawned, fabulous tech has enabled us to record amazing audio, generate graphics, edit films, and expect all information to be at our fingertips. We are the last generation that will remember analogue, its failings, limitations, and its epic strengths. Our soul is lifted by knowing how to actually do something, rather than having a device that does it for us. Go far, go light, use maps.

Freelance writer Karin-Marijke Vis, along with her partner, photographer Coen Wubbels, combine their love for adventure with work they enjoy. Sometimes described as being the “slowest overlanders in the world,” they believe in making connections and staying in a place long enough to do so. In 2003, the couple purchased an antique BJ45 Land Cruiser and began a three-year trip from their home in the Netherlands to Asia. Terminally infected by the overland bug, they traveled in South America for nine years, and in Japan and South Korea for two years. They are currently making their way through Russia and Central Asia. They’ve been published in magazines around the world, and in 2013, Expedition Portal awarded the pair the coveted Overlander of the Year award.

Chris was born and raised outside of Dallas, Texas, and didn’t receive a real taste of the outdoors until moving to Arizona in 2009. It was there that he fell in love with four-wheeldrive vehicles and the great outdoors, quite literally altering the path of his life. Instead of pursuing his planned career in aviation, Chris accepted a position with Overland Journal and Expedition Portal, where he would hone his skills in writing, photography, and off-pavement driving. Over the years, he has lived full time on the road, mapped trails from the Arctic Circle to Mexico, driven across Australia, and backpacked the Himalayas. He is currently an Airstream Ambassador and works for onX Off-road, managing their Trail Guide community.

Graeme Bell is a full-time overlander and author. He was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, but considers Europe home when not traveling the planet with his wife, Luisa, and two children, Keelan and Jessica, in a Land Rover Defender 130 (affectionately known as Mafuta). To date, the Bell family and Mafuta have over a period of seven years toured Southern and East Africa, circumnavigated South America, and driven from Argentina to Alaska before traversing the US from coast to coast. In December 2016, Graeme personally transformed their Defender from a standard double cab into a camper with through access, a pop-top, and sleeping for four in anticipation of their current adventure: driving from Europe to Southern Africa.

Lisa and Simon Thomas of 2RidetheWorld are considered by many to be the world’s foremost adventure motorcyclists. With more real-world experience than anyone on the road today, they have ridden their way into a life that most of us can only imagine. Since setting out on their journey in 2003, the duo has amassed an insane half-a-million miles on their ride, through 80 countries, across six continents. Along the way, they’ve traversed 36 deserts, survived a broken neck in the Amazon Jungle, cheated death, and have become explorers, authors, photographers, and celebrated public speakers. Remarkably, they’re still going strong today. It’s easy to say that Lisa and Simon inspired and ultimately helped define what we all now call adventure riding.

Thomas Henson is an educator and writer based in the UK. A former military police officer and ex-bodyguard, he has lived and worked in a variety of countries, including Sudan, Tunisia, Poland, and Israel. When he’s not teaching, Thomas is on a mission to track down the most interesting places, people, and stories. A fan of ancient mythology, his next big idea is to explore Scandinavia, to track down the locations that inspired Nordic folklore. Thomas is married to the creative and talented Emily, and a proud dog-dad to two Nova Scotia duck tolling retrievers. He also has two cats, who do not earn their keep.

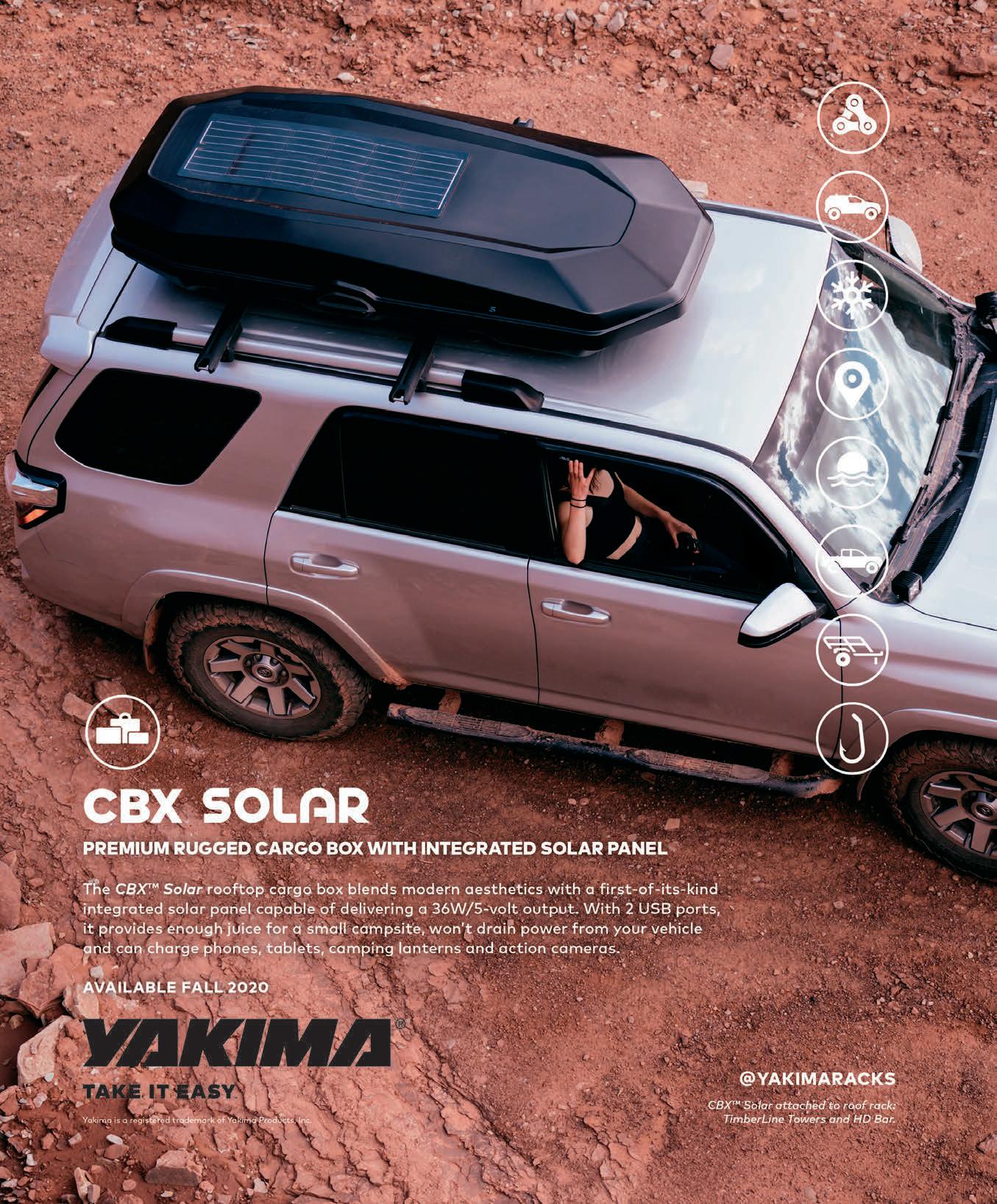

Elemental protection in a smart package.

The current iteration of Klim’s Latitude suit for men and Altitude suit for women tackles most road and dirt conditions. They accommodate varying abilities, riding styles, and trip profiles. The original Latitude/Altitude targeted the ADV and dual-sport/enduro crowd, but Klim saw touring riders favoring it, too. It handled dust, rain, and abrasions, and with its stylish looks, the jacket could also withstand beer gardens and dinner reservations. Klim eventually hit the drawing board to refine the Latitude/Altitude for touring, after filling the ADV/enduro niches with dedicated designs. However, the latest iterations are just as multifaceted as the original versions. They are a true go-to for dust-laden Baja rides, variable weather explorations on unimproved Balkan roads, or that 100-percent tarmac road trip up California’s Highway 1.

The latest iterations are a true go-to for dust-laden Baja rides, variable weather explorations on unimproved Balkan roads, or that 100-percent tarmac road trip up California’s Highway 1.

An Alpha-Bet soup of specialized Gore-Tex, abrasive resistant fabrics, zippers, reflective materials, and armor indicates these suits mean business. While men’s and women’s variants have different colors, vent locations, and physique-specific cuts, they do have similar construction and materials. Key refinements include an offset neck tension cord (helps prevent ponytail snags), and goat hide on the elbow and upper arm for sudden mishaps, as well as at the lower inner thigh area to mitigate wear. External pockets and zippers on the jacket and pants are placed in intuitive and useful locations. Jackets have various pockets on the left and right interior, along with a few hidden ones. Along with abrasionresistant materials, D3O inserts provide Level 1 crash protection. Useful Klim intel here: North American users who want increased impact protection can up-armor to Level 2 Conformité Européene (CE) European standards, as all slots accept inserts from either specification.

Motorcycle garment breathability and crash protection are frequently at odds. To this point, jacket ventilation on both models is adequate, with lower arm, chest, and back vent options helping to control the flow. Unzipping the hip gussets increases circulation, and in hot weather, I slightly open the Velcro cuffs for maximum airflow. My three-season gloves can manipulate the zipper pulls. Both pants vent even better when riders stand up on the pegs. A phone/device jack port is provided on the left-inside chest pocket, and the medical ID card/key stash is on the lower left sleeve. Having these options on both sides would be welcomed.

Gina De Pasquale, an ADV motorcycling instructor at Rawhyde who works in various sectors of the industry, reports that the updated women’s Altitude has good complementary airflow through the

Klim’s Latitude/Altitude suits for men and women provide great all-around comfort and protection for multi-season touring, dual-sport, and ADV riders. Design nuances include an offset neck tension cord to keep hair out of the mix, hooked tabs to hold open the lapels, waterproof zippers, and refined ventilation/gussets in key locations.

chest vents and out the back. The feminine cut, two-tone colors, and subtle yet attractive graphics provide style. She often utilizes the neck tabs, which can hook open for maximum ventilation. Emanating from an adventure bike and dual-sport background, yet with updated travel-oriented refinements, the Latitude/Altitude suits are at home anywhere. They could easily be the only jacket/pant combo you need.

$650/JACKET, $500/PANT (LATITUDE); $600/JACKET, $500/PANT (ALTITUDE) | KLIM.COM

Built to impress, and made to last.

Shovels have become a hot commodity in the overland marketplace. You can buy them pointed, square or round, ultralight or tactical, and even carbon-fiber models with titanium blades. At times, the designs and price tags can seem a little absurd.

Let’s be honest, though, the reason people are willing to buy expensive shovels isn’t that they’ve become fascinated with digging—it’s because they look cool. But RoamBuilt’s V-nose combines good looks with practicality. The laser-etched logo stands proud along the handle, a serrated edge runs the length of the blade, and a sharp nose looks poised to destroy any dirt that has the gall to stand in your way. At first glance, experts might say the blade would be inefficient for moving large quantities of soil, and they’re right. However, the pointed shape is excellent at breaking through the first layer of ground, and that’s where we spend the majority of our time digging. After all, catholes are 6-8 inches deep, and we aren’t usually digging deep trenches for recoveries. If you do find yourself needing to dig one, fear not, this shovel is up to the task. It’s fully welded to eliminate any movement or wobble and features a flat footpad and solid T-grip for leverage and stability. The blade is made from a strong-formed 5052 aluminum alloy, and the whole shovel is sealed with a heavy-duty powder coating for corrosion resistance. Despite this hardy construction, total weight comes in at just 3 pounds, making it a breeze to handle.

It’s fully welded to eliminate any movement or wobble and features a flat footpad and solid T-grip for leverage and stability.

The size is ideal for most overland tasks: small enough to maneuver beneath the chassis for clearing mud, sand, or snow from a high-centered vehicle; large enough to put your back into big jobs when needed. I do wish the blade angle was greater for easier scooping, as the current one makes it difficult to pull large quantities of sediment out from the side of the vehicle.

Other redeeming design elements include the T-grip made from solid 6061 aluminum, which allows it to be used as a hammer, and the bottle opener cut into the blade for cracking open a cold drink when the work is done. The only feature I could live without is the shovel’s serrated edge, since it is too dull to be usable.

The V-nose isn’t the cheapest shovel on the market; it’s also far from the most expensive. It’s well-built, lightweight, looks great, and has performed flawlessly in every challenge I’ve put to it.

$75 | ROAMBUILT.COM

Expanding on the foundation of getting unstuck.

There is a sinking feeling with getting stuck, both literally and intellectually. Once stuck, our options dwindle, and the potential consequences mount. Additional damage is likely, as is being stranded, or worse, losing the vehicle to the rising tide. As a result, there are fundamental tools that belong in every overlanders’ recovery kit. It certainly includes the basics like gloves, a good shovel, and a set of traction boards, but it should also include a means of conducting powered self-recovery or a vehicle-to-vehicle pull.

MaxTrax has redefined self-recovery with the invention of its reinforced nylon recovery tracks. Owner Brad McCarthy also recognized the opportunity to improve powered recovery or vehicle-to-vehicle extraction, and started a new line of accessories that have been optimized for light weight, performance, and safety. Last year, I had the opportunity to use prototype versions of these new tools along the Great Australian Bight, during an

adventure I was undertaking with friends from Hema Maps. Brad was along, and he quite nearly risked life and limb, demonstrating the capabilities of these tools. It all started with a high-speed roll of a Polaris RZR in the dunes lining the Indian Ocean.

With a vehicle rolled, out came the tools to right the machine safely. The first new product is a precision-machined Hitch 50, specifically designed to work with a soft shackle. It’s relevant, as many vehicles only have a receiver hitch for a rear recovery point, and it is difficult to use a soft shackle without causing damage from the receiver’s sharp metal surface. The 6061 billet aluminum Hitch 50 is CNC machined with a large radius and locating profile to best support a soft shackle in either a vertical or horizontal axis. The working load limit (WLL) is 19,400 pounds, and it has a minimum breaking strength (MBS) of 97,000 pounds. To ensure quality, each hitch is x-rayed for inclusions. It’s a highly specialized tool, which is its greatest strength, but also its limitation since a traditional screw-pin metal shackle cannot be used.

These winch rings have become extremely popular due to their lower storage weight and reduction of the overall mass of the winch rigging.

Additionally, MaxTrax also released a Winch Ring 120, which was designed to reduce the overall weight of a double-line winch pull and to minimize point-loading and heat by machining in a large internal diameter radius. The ring has a WLL of 27,000 pounds, and an MBS of 137,000 pounds. These winch rings have become extremely popular due to their lower storage weight and reduction of the overall mass of the winch rigging. It is important to note that these rings are only ideal for static winching operations, not dynamic driving/winching conditions. To complement the ring and the hitch, they offer a Core soft shackle with an MBS of 30,000 pounds, and a Fuse soft shackle with an MBS of 15,000 pounds. These are unique offerings, with an intentional fusible link incorporated into the rigging. The Core and the Fuse both utilize wear/heat sleeves to improve durability with the winch ring and other connection points. MaxTrax continues to expand its recovery offerings with quality components, which bodes well for the future of overlanders beating the rising tides.

$250/HITCH 50, $200/WINCH RING, $49/CORE, $39/FUSE | MAXTRAX.COM.AU

The Hitch 50 is one of the first soft-shackle-specific connection points on the market. The primary advantage of a recovery ring is reduced weight for storage and as mass within the rigging system.

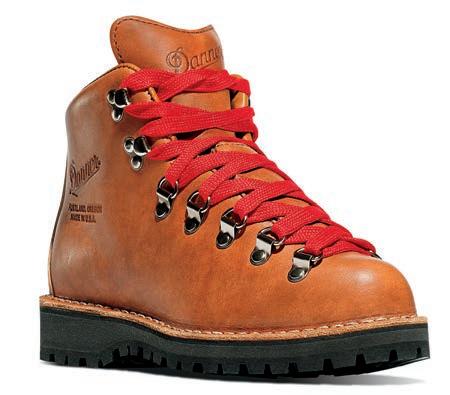

Recognized from their starring role on Reese Witherspoon’s feet in Wild, but remembered for their all-around perfection.

Leather boots require serious commitment, and there’s no secret sauce to bypassing the inevitable pain while they mold to your feet. But when it comes to my essential choice for work boots during spring, fall, and winter seasons, the pain is so worth it. Unlike most traditional leather hiking boots, the Mountain Light Cascade feels extremely light. It’s an excellent choice for quick errands when there’s slippery snowfall, in addition to its original functionality, most at home during long outdoor treks. This element is especially key for me, a SoCal girl who despises wearing anything more than a sandal; I don’t mind sporting these because nothing feels clunky.

Designed and manufactured in Portland, Oregon, Danner spares no expense. These full-grain, single-piece, all-leather upper boots with Vibram Kletterlift outsoles are specifically created for comfort and durability. They feature a 100-percent-waterproof and breathable Gore-Tex liner, engineered to keep your feet dry and comfortable. In warmer temps, you’re likely to be a little more sweaty in the foot department due to this combo, though. Their handcrafted stitch-down construction makes them re-craftable and easy to resole, i.e., these boots will literally last forever, so ignore the price tag. The wider platform increases stability underfoot, and the support is further unrivaled thanks to the unique heel shape that provides superb shock absorption. In the end, I never seem to mind the ogling onlookers when I step out in these bad girls.

$360 | DANNER.COM

Probably the most boring thing to read about in this magazine, but a 100-percent game changer.

Remember when I said there’s no secret sauce to bypassing the inevitable pain while leather boots mold to your feet? I sort of (unintentionally) fibbed. There is, in fact, a fairly magical solution that is not only incredibly cheap and easy to use but also extremely effective. Whenever I pick up a new pair of leather boots, I grimace, not at the price tag, but at the thought of my poor feet, grossly bubbling and bleeding while I walk on eggshells for weeks, praying that the devil boots will eventually stop mutilating me. Socks never seem to do the trick. Deodorant is a disgusting old wives’ tale. And whoever said we should grin and bear it should shove it.

Fortunately, Band-Aid developed these sweet little bandage cushions that provide preventative protection and future relief from

blisters, the red-headed stepsister of the dreaded paper cut. After application, a white bubble forms to cradle the wound. The hydrocolloid bandage (fancy word for moisture-retentive dressing) keeps dirt, water, and germs away for multiple days, even through soapy showers, which allows your body to heal faster in an optimally sterile environment. I tried my best to make this review exciting, but the reality is, just go buy some at your local everything store and know that your life will be forever changed.

$6 | BAND-AID.COM

This four-season tent will keep you high and dry.

Based in Central California, Hinterland Industries Tents (HiTents) designs classically styled rooftop tents (RTTs). I obtained their Rincon from company owner, Graham Holloway, for a multi-month field test, and mounted it to a Front Runner Slimline II roof rack on a Toyota Tacoma.

The Rincon sleeps three (more with the included annex) and is designed as a four-season RTT. With a time-honored appearance, it’s reminiscent of Howling Moon or Eezi-Awn tents from South Africa. The tent weighs 150 pounds and has a heavyweight 400g ripstop breathable poly-cotton canvas tent body with impregnated waterproof coating. The body material is UV and mold resistant, as are the rainfly and travel cover. Quality dual-stitched and heat-taped seams keep water out. The rainfly is elevated (when the spring steel rods are inserted) and made from 420D polyester oxford fabric. The tent base has an aluminum frame, honeycomb core,

and custom-thickness diamond plate exterior. The travel cover is rugged 1200D PVC. I found it difficult to zip closed on occasion; other times, it zipped easily. This seemed somewhat dependent on how well the folds were tucked in upon closure, but the fact is, all PVC covers are problematic to close.

The comfortable, high-density, 3-inch-thick foam mattress comes with a washable cover. The tent interior seals like a tomb and makes for dark sleeping quarters. In high winds, I didn’t detect air ingress. Interior gear pockets are located at both ends, where your head would rest, facilitating numerous sleeping arrangements. When opened, small ridge vents allow air circulation. Two shoe bags hang outside the tent entrance. The ladder length can be slightly adjusted for varying ground conditions, and the rungs aren’t overly angular, so they’re easy on bare feet.

The comfortable, highdensity, 3-inch-thick foam mattress comes with a washable cover. The tent interior seals like a tomb and makes for dark sleeping quarters.

Clamshell tent setups are inherently faster with two people, and the ease with which tie-down straps, zippers, and guide rods are accessed varies. Likewise, the amount of kit that requires loosening can add minutes to solo person tent deployment. With the travel cover installed, it usually took one person about five minutes to get the tent sleep-ready, and consistently around the 10-minute mark to have all the spring steel rods and rainfly secured. Takedown to road-ready (including travel cover) typically required approximately 12 minutes.

The overall build quality is excellent, although we did not test the included annex. The 1-inch interior poles are fabric wrapped, the hinges and hardware are stainless steel, and the ladder mounting brackets are TIG welded stainless. Zipper sizes on the fly screens and canvas flaps seem adequate and don’t require undue finesse. I favor this RTT style when the truck is in place for a few days at a time, mainly because of the setup/takedown time. When deployed, it protects and shades better than hardshell pop-ups.

$2,475 | HITENTS.COM

Clockwise from top: The Rincon, deployed for a good night’s sleep. Exterior shoe bags at the entrance keep footwear at the ready. Cabin Fever can creep in when sheltering for extended periods from Mother Nature. During inclement weather, the Rincon’s interior was accommodating enough for lengthy daytime hanging out (reading and working on reports), with ample provisions for ventilation and views. Stainless steel hardware and hinges, and a diamond plate exterior should allow many years of use. At 150 pounds, the Rincon isn’t lightweight. Assess the rooftop load rating, and include the mounting rack and any attached gear in those calculations. On some smaller trucks, mounting over the bed might a better solution.

A powered high-volume purification system.

Sustained remote travel typically requires a means of resupplying water stores, with vehicle-based camping, bathing, cooking, and drinking. Why leave that idyllic mountain stream campsite when all you need is a proper volume filter to supply 2-3 gallons per day, per person?

Enter Guzzle H2O, a company founded by two professional sailors.

A few things stand out—the first being the durability of the box, a Pelican-style case complete with a lid seal and robust ribbing. All components are visible, including the Flojet pump, UV module, and high-quality, screw-top filter assembly. Quick-connects allow the inlet and outlet hoses to be easily attached, and the push of a button starts the process at 1.1 gallons per minute, powered by the built-in battery. The serviceability of the system also makes owner repair a real possibility.

The filtering process includes a 99.99 percent LED UV pass that kills bacteria, protozoa, and viruses. Then, the carbon block filter removes solids, microplastics, VOCs, and heavy metals. The pump is noticeably quick and pulled a draft from several feet. There are two lengths of outlet hose provided, and hoses are clearly identified to limit cross-contamination. The battery did come unstuck from the side of the case, easily fixed with a mounting bracket or strap (adhesive has since been improved based on our feedback). Some may find the price a bit steep, but it reflects the quality of the filter and components.

$950 | GUZZLEH2O.COM

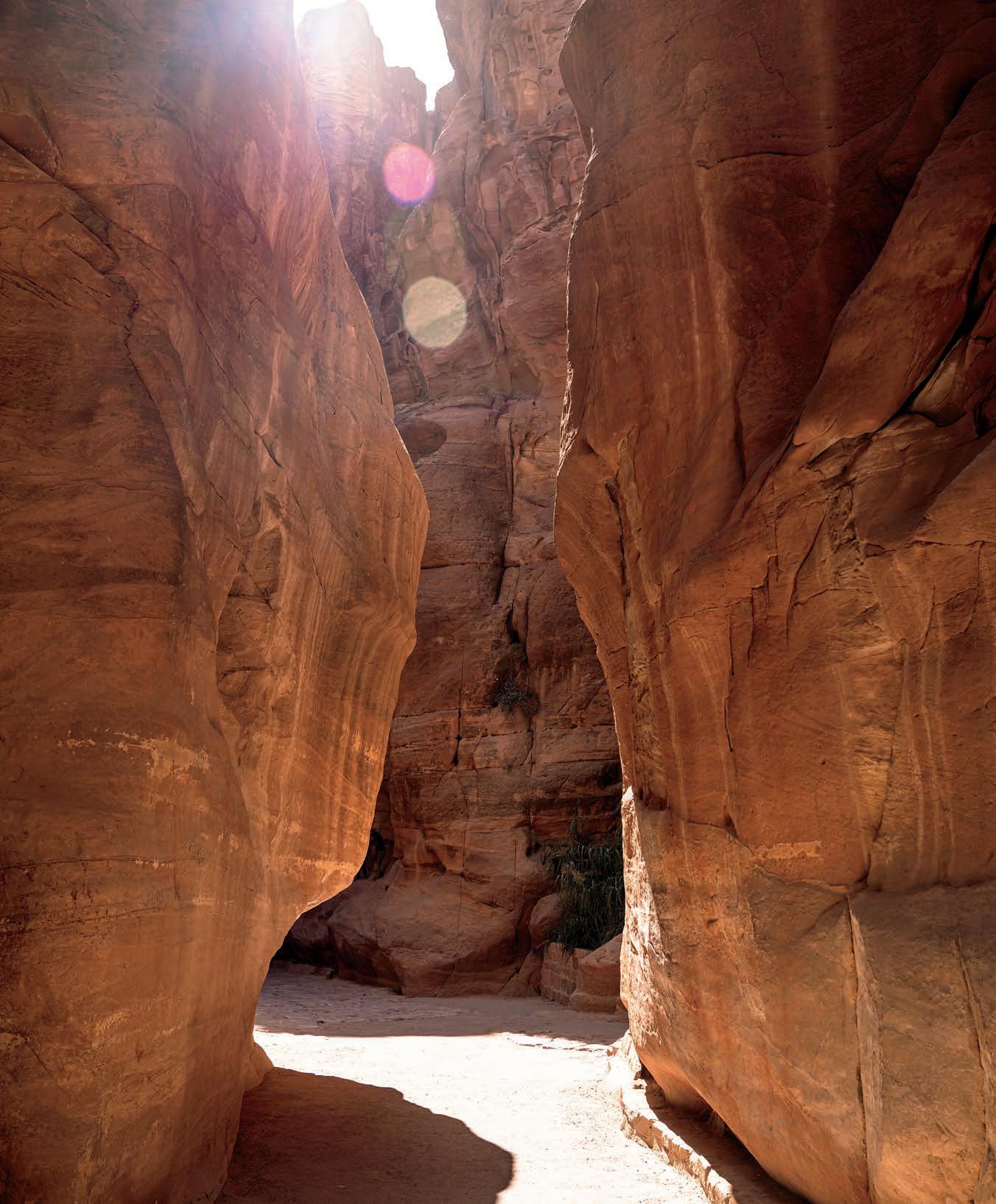

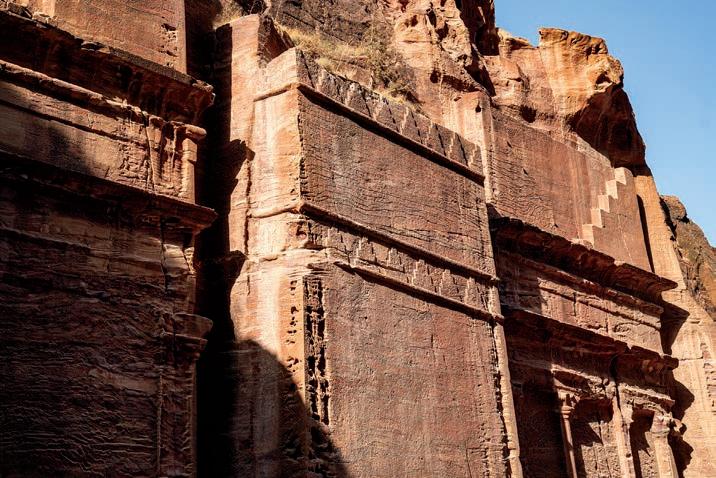

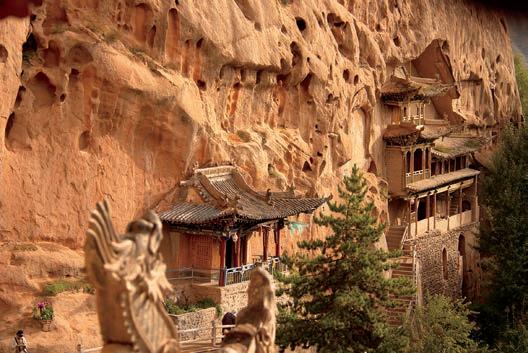

Archaeologists use satellite and drone remote sensing technology to reveal further wonders at Petra.

By Jaclyn Trop

Racingthe sun to reach the Seven Pillars of Wisdom before dark, our cavalcade of SUVs bumps along the red sands of Jordan’s Wadi Rum desert as we gun it toward the horizon. We reach the base and tumble out of our trucks with minutes to spare. Named for T.E. Lawrence’s memoir, the heptahedron rock looms large with historical significance.

The man known as “Lawrence of Arabia” for his role in the First World War’s Arab Revolt trod this land just more than a century ago. As liaison to the British military, Lawrence traveled the desert’s rolling red sand dunes and sweeping sandstone valleys to relay intelligence that helped defend the area from the Turks.

But that’s all recent history. The striated rocks around us hint at natural forces at work eons before Lawrence arrived. To the untrained eye, the reddish, otherworldly landscape may as well look like Mars (and did serve as Mars during the filming of The Martian with Matt Damon). In fact, Wadi Rum has been described as anything but Earthlike; its name translates as Valley of the Moon for its dwarfing rock formations. The topography testifies to the geological evolution of our planet, but until not long ago, what lies beneath has remained mostly a mystery.

Fortunately, we are traveling with a gaggle of archaeologists who can decode the landscape’s layers of sandstone, granite, and shale for us on our overland drive from the Dead Sea to Petra.

“We know more about Mars than we know about Earth,” says Scott Nowicki, an Albuquerque-based scientist and one of the world’s leaders in remote sensing, a technique that uses drones and satellites to learn more about the earth’s natural features.

Wadi Rum may resemble the Red Planet, but this land is steeped in its own saga, recounting the origins of humankind.

We arrived in the Middle East days earlier as part of a 30th birthday celebration for Infiniti, Nissan’s upscale sister brand. For its pearl anniversary, the Japanese carmaker put a team of scientists and journalists into its latest SUVs to travel part of Jordan’s King’s Highway, an early trade route, and trawl ancient settlements.

Three decades after launching in the US, Infiniti is highlighting an ethos of exploration, using new technology to push boundaries. Through a partnership with the Explorers Club, the carmaker supports expeditions that pioneer new tools to learn more about the planet.

The scientists seated alongside us for the journey are early adopters of satellite technology, breaking new ground to understand the past while revolutionizing the future of archaeology. The images captured by satellites and drones can construct an aerial view that helps them detect the outlines of ancient structures. Then they can home in on specific locations and compare other discoveries in the area to gain a broader understanding of the landscape’s past.

Clockwise from top right: In its heyday two millennia ago, Petra was a thriving city of 30,000 with a sophisticated network of hydraulic systems. Wadi Rum’s geology is rich in sandstone, granite, and shale. Archaeologists discovered this ancient site near Petra’s city center using satellite technology. It is believed to be a Nabataean ceremonial platform. Known for its sweeping curves and switchbacks, the Namla road runs from Aqaba in southern Jordan to Petra. The Treasury, a 130-foot-tall temple carved out of sandstone, is Petra’s most photographed feature. Opposite: Infiniti brought a team of archaeologists to Jordan to explore ruins using satellite technology. Opening spread: Jordan’s Wadi Rum desert is called Valley of the Moon for its jutting rock formations and rich geology.

Our expedition’s guest of honor is Sarah Parcak, an archaeologist who won the esteemed TED Prize in 2016. An expert Egyptologist, Parcak serves as a professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and authored a 2019 book about her adventures in the field, Archaeology from Space: How the Future Shapes Our Past.

As a leader in remote sensing technology, Parcak uses infrared satellite imagery to scour sites from her desk in Alabama. This innovation cuts the time and money required to make discoveries, allowing archaeologists to survey regions in months instead of decades.

Remote sensing has already helped Parcak locate 17 possible pyramids, 1,000 tombs, and 3,100 forgotten settlements in Egypt.

Parcak is already making an impact. Our drive through Wadi Rum will eventually lead us to Petra, where she and her team unveiled an ancient site in 2016. Satellite and drone remote sensing technology helped the archaeologists achieve what few have done since Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt rediscovered the lost city of Petra in 1812: make a major discovery near the historic city center.

Some of this was accomplished at her desk in Alabama, using satellite and drone imagery to pinpoint the structure buried half a mile south of the city’s center. The site, which measures about 160 feet by 330 feet, could date back two millennia.

The tools will help scientists uncover ruins in Petra and other locations. These technological advancements have given rise to Parcak’s goal: to map the entire world in the next 10 years.

Remote sensing has already helped Parcak locate 17 possible pyramids, 1,000 tombs, and 3,100 forgotten settlements in Egypt. But that barely begins to fulfill the potential satellite technology brings to the field. “I mean, we have discovered less than 1 percent of ancient Egypt,” she says.

She used her $1 million TED Prize money to launch GlobalXplorer, a crowd-sourcing platform that pioneers a new way to uncover archaeological sites. The website enlists volunteers to analyze satellite images previously available only to scientists.

Volunteers complete a tutorial and receive a selection of satellite images to pore over. If they spot a potential site and scientists confirm it, the app’s users can follow the excavation via live streaming.

Harnessing armchair hobbyists helps increase the impact exponentially. So far, Parcak has amassed 90,000 volunteers who trawl the images for signs of ancient settlements. “There’s this idea of, ‘How much is there to find?’” Parcak says. “But you can’t possibly predict what you don’t know. It’s like asking how long is a piece of string.”

We decamped for the night to Memories Aicha, a warren of air-conditioned yurts in Wadi Rum. The constellation of metallic blue geodesic domes springs up from the red sands like a Martian

mining settlement. The labyrinthine network of winding wooden sidewalks connecting the bubble tents creates the feel of living in a neighborhood in a cartoon universe.

Over beers, Parcak tells us about her personal journey, starting with Indiana Jones, a looming figure in the world of archaeology and Parcak’s life. “I watched him with reverence,” she says of the faux-1930’s pop culture icon played by Harrison Ford. The 1980’s movie franchise about an archaeologist battling looters inspired a generation of archaeologists currently in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.

But Jones’ hunt for the Lost Ark has taken on new relevance, especially in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. The looting of valuable artifacts from archaeological sites is on the rise. It’s not unusual for an antiquity taken from a site to end up on the Sotheby’s auction block for $3 million, Parcak says.

Political instability, coupled with high resale values, incentivizes theft and destruction. Professional looters from Iraq are coming into Syria now, Parcak says. It’s not uncommon for farmers with intimate knowledge of local excavations to tip off the professionals or become professional looters themselves.

Satellite technology can help identify looting areas and shed light on the black market, according to Parcak. The data could provide insight into the networks that move artifacts from historical sites to Western markets. “We have to be a lot more honest about what we don’t know,” she says.

So far, Global Xplorer has mapped more than 200,000 looting sites in six months using tens of thousands of satellite images. (To avoid tipping off looters, Global Xplorer provides users with a general location but not GPS coordinates.) This information can also help governments protect their valuable antiquities and create databases of their cultural treasures.

Parcak says she hopes that looting antiquities may one day fall out of fashion, like raising public awareness did for wearing animal fur. “I wish I could stop the looting,” Parcak says. “I wish I had the Harry Potter magic wand.”

On the final morning of our expedition, we arrive in Petra, home to Jordan’s most striking monuments and oldest history. The city was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985 and voted one of the “New Seven Wonders of the World” in 2007. More than a million visitors arrive annually to gawk at the striking spectrum of reds, oranges, and pinks embedded in the striated sandstone that gives Petra its nickname: the Rose City.

It’s also known as the Lost City, abandoned by the Romans after the 8th century AD. Its pink-hued temples and tombs remained largely out of public consciousness until Burckhardt happened upon Petra a millennium later.

On the morning we arrive, flocks of tourists descend upon Petra in barely controlled chaos under the sweltering September sun. They snap photos in an effort to capture the sunlight on the striated sandstone while narrowly avoiding the horse carts that hurry down the path at an alarming speed. The journey into the city’s center begins on the Siq, a 3/4-mile track that winds downhill to open into the Treasury, Petra’s most iconic monument. The 130-

Clockwise from top left: Jerash, 30 miles north of Jordan’s capital city Amman, is one of the best-preserved ancient Roman cities. Built between 150 and 170 AD, the Corinthian columns of the Temple of Artemis in Jerash still stand. The road to Petra, which sees more than a million visitors annually. The earliest evidence of settlement in Jerash is in a Neolithic site dating to around 7500 BC. Most of Petra’s famous monuments were built between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD. Our drive through Wadi Rum will eventually lead us to Petra, where Parcak and her team unveiled an ancient site in 2016. Off-duty camels on reprieve in Petra.

foot, pillared temple carved into a sandstone rock face is Petra’s most photographed feature.

Most of Petra’s iconic monuments were built between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD. In its heyday, it was a thriving city of 30,000 with a sophisticated network of hydraulic systems.

But there’s evidence of Neolithic villages in the hinterlands dating 7,000 years prior. The nomadic Nabataean tribe, skilled merchants who established trade routes to Africa and the Middle East, arrived in the 6th century BC. The city survived Roman rule and two devastating earthquakes. Today it’s still home to many Bedouin, who sell trinkets and serve tea to tourists along the Siq.

Over the years, archaeologists have come to Petra to unearth tombs and temples, slowly threading the past to the present. Parcak and her team have made the most recent major discovery here: a Nabataean ceremonial platform “with no known parallels to any other structure in Petra.”

After marveling at the Treasury, we head south and embark upon a half-hour hike, not for the faint of heart. We pass a freestanding amphitheater made of

rock as well as several elaborate caves, which we’re told may have served as someone’s living room thousands of years ago.

The path to Parcak’s site gets steeper and twistier as we climb. Finally, we reach the top, where Parcak says her discovery “had been hiding in plain sight.” To the nonarchaeologists among us, it’s just a wide plateau on the mountain, dusty with sand and pebbles. To Parcak, it’s a potential ritual location dating to the mid-2nd century BC.

sit on the ground,

Satellite and drone remote sensing technology revealed the possible monumental structure, but the equipment has become so sophisticated that it can now be seen on Google Earth. The platform most likely served as a public ceremonial site, especially since it’s located up high, similar to Petra’s other historical places of worship. Overall, the area measures about half a football field or double an Olympic swimming pool.

There is also evidence of a possible altar on a smaller platform originally paved with flagstones and a row of columns that may have topped a staircase. Measuring about 184 feet by 161 feet, the discovery could prove the second-largest elevated religious site uncovered in Petra after the Monastery, an iconic Nabataean tomb

built in the 3rd century BC in the hills high above the Treasury.

Parcak hopes it can be excavated within the next few years. Shards of pottery found on the surface suggest construction began more than 2,000 years ago during the Nabataeans’ initial building boom.

We sit on the ground, enjoying the view below while running our hands over the sand to unearth small tiles and pottery pieces. The scientists among us eyeball the finds to determine whether they’re historical relics or modern detritus. It is difficult to tell.

We take a swig from our water bottles and begin to trudge back down the mountain, clambering over rocks and slippery patches. Parcak appears flush with excitement from visiting the site; she knows she has only scratched the surface.

Once we reach a footpath, we see an elderly woman behind a makeshift table selling what Parcak thinks are looted artifacts. She hands the woman money but refuses to take a trinket. “Maybe in 20 years, it won’t be cool to loot sites,” she says. “We can ‘cancel’ Indiana Jones.”

We test the best navigation and planning apps for overland travel.

By Scott Brady

Astravelers, we embrace the serendipity and randomness of travel, the paper map unfurled on a dusty hood, each direction yielding a wonder. There are also times when we get two flats in one day and just really, really want to find a campsite. Planning and technology can complement adventure, even if our romantic ideals of exploration spurns visions of the Luddite’s journey. There are tools available today that make overlanding safer and more connected than ever before, allowing us to plug in while we unplug. In the end, these apps are tools, and we can always eschew those conveniences if we choose.

The most useful of the programs are navigation applications, which allow physical progress (via GPS) to be rendered over a map layer, shown alongside XML data like waypoints, tracks, and POIs. What started as simple topographical applications that displayed 7.5-minute scanned and rastered paper maps on an iPhone 10 years ago (Topo Maps app) has now grown to feature-rich navigation and planning tools with base layers from both open and curated sources. Most importantly, they have started to become reliable for track recording, which, in our experience, has been buggy at best, or an utter failure at worst. As a result, we still bring a traditional Garmin GPS to ensure our route is securely saved.

THE JUGGERNAUTS It is easy to dismiss the most popular (and even native) applications like Google Maps, Google Earth, Apple Maps, and Waze, but they are widely used for compelling reasons. Most notably, their access to user data that helps indicate traffic patterns, closed roads, or the newest routes.

The most useful of all of these is Google Maps, as favorites can be shared across devices and, critically, it allows for the downloading of off-line map data from anywhere in the world. Search for a place, click on the place name, then select the three dots on the top right. “Download Off-line Map” will be an option, and store the data locally on the phone for one year. Waze’s usefulness depends on what city has largely adopted it, but the tool can be a big help when bypassing traffic jams or local demonstrations.

The next most valuable navigation tools are backcountry-specification applications such as Gaia, onX, Hema, Tracks4Africa, Rever, and others. Their greatest strength is access to topographical map layers, off-line satellite images, and user-contributed routes and data points. The best maps have organizational-validated tracks, which are either done with 100 percent ground truthing by mapping professionals (Hema Maps in Australia), or by aggregating user-contributed data to improve accuracy (Tracks4Africa).

Additional features can include land designation, and route types (e.g., 50-inch or motorcycle-only trails on onX). These apps should also include reliable tracking of routes for future sharing and reference of GPX or KML files.

SUPPORT APPLICATIONS Support applications like iOverlander are relevant for the traveler and will help solve that 2:00 a.m. campsite problem. But with great power comes great responsibility. Try to avoid using these popular and overused campsites, if possible, to distribute impact. And if you do stay at one, ensure that the campsite is a legal place to crash for the night, and do everything possible to clean up all trash (even trash left by those before you). These user-curated sharing apps are among the most significant developments in vehicle-based travel in the last decade, as they provide key insights into finding water, laundry, or that specialized Syncro Westfalia mechanic.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Support applications like iOverlander require a degree of user responsibility, including minimizing the overuse of wild campsites. As these apps have become more popular, it has resulted in significant problems, including campsite closures, agitated locals, and piles of trash and human waste. These apps should be considered travel aids, not guidebooks. As responsible travelers, we should make every effort to distribute impact to other locations, and ultimately, leave the place we stay better than we found it.

Apps like Gaia and Hema Explorer allow for planning and navigation in areas with little base map data, like the frozen MacKenzie River delta feeding out into the Arctic Ocean. We also used the apps to record tracks and share position data with other groups of logistics partners, as with this screen capture along the shoreline of Antarctica. Opening page: Applications have significantly improved confidence while exploring remote and unfamiliar corners of the globe. During my time navigating an exit glacier of the Greenland ice sheet, I watched our position as we moved between crevasse and water traps covered with a thin veil of ice and snow.

Itseems as if every solution has its stalwart, and Gaia GPS is the overlanders’ map for the 21st century. Gaia GPS (not to be confused with the Gaia alternative media site for people traveling to, well, conspiracy land) has been around since 2008 and has weathered the software application minefield to become a popular and reliable tool for backcountry travel. The company was founded by Anna and Andrew Johnson and remains independent and employee-owned to this day.

The crucial deliverable of the Gaia app is reliability—dead-nuts dependability of both tracking and off-line maps. While it might seem surprising, recording a reliable track without crashing or producing erroneous data appears to be a challenge in the space. Yet Gaia seems to have figured it out. I have countless tracks, waypoints, and routes saved to the app, and they all sync flawlessly across devices and the desktop browser. For the remote and international traveler, it is necessary to be able to upload track data as a breadcrumb or save a completed track as a GPX for future reference and sharing. I still remember getting hopelessly lost in a labyrinth of small streets in a Moroccan city, only to reverse my way out thanks to a reliable breadcrumb track.

The reliable recording of a track is one of the hallmarks of a properly designed app. These tracks are essential for sharing route information, or even backtracking when lost. Gaia has one of the most reliable tracking functions of any app we tested. Gaia is a robust app with multiple base map options, including historic topo maps of areas like Prescott, Arizona. Historic maps provide interesting context to the trip, and hidden gems like old mines and townsites. Through the saved track function, it is possible to reload previous tracks into the active maps, which is helpful for finding the route back to that perfect campsite or fishing spot.

Bells and whistles are good, but a reliable map and track is the DNA of good navigation.

The Gaia app is feature-rich, but it (thankfully) does not look like it. The main screen is taken up almost entirely by the map, and there are a few small and recognizable buttons and pages that are easily accessible. Along the top, there is a search function (which has improved markedly in recent versions), and full-screen, current location, add, and map layer buttons. The map layer button is where the magic happens, allowing adjustments to the map overlay and which base map renders on the screen. The layers are extensive, but critically includes USGS Topo, satellite, and several land-use overlays. International sources are primarily OpenStreetMap and satellite, which is more than sufficient and generally reliable. All of these maps can be saved for off-line use, and there is even a 1900 historic topo layer which sent my explorer vibes into the stratosphere. My complaints with the application are minimal, as recent updates have greatly improved stability. Apple CarPlay is available but rudimentary, and getting the full benefits of the app does require a $40 per year investment. My wish list includes a paid option to access the National Geographic Adventure Maps (like Baja) as a map layer.

$40/PREMIUM, ANNUALLY | GAIAGPS.COM

Everygrowing industry breeds a disruptor, a company that uses a rapidly expanding market to slingshot innovation and user adoption by a factor of 10 times. And onX has become that influencer within the overland mapping segment, launching a rapid-fire release of new features. The company was started by Eric Siegfried, a hunter and overlander that noted the need for clear land designation while driving in the backcountry. The company also recently hired one of our longtime team members to manage their growing ground-truthed track dataset.

For overland travel, knowing the land designation is critical, since trespassing is just as problematic as crossing State Trust Land without a permit. The company uses a topo or satellite hybrid base map and then overlays with land designation and track data to present an up-to-date accessibility profile. State Trust, BLM, NFS, and private lands are clearly defined by both name and colored map tiles. It is important to note that these features are only usable in North America.

The app is thoroughly modern, with clean icons and minimalist menus. The top of the screen is oc-

The onX app is packed with useful data sets and information layers, including selecting the type of terrain or vehicle. This turns on or off trails that afford the level of difficulty or restrictions beneficial for good route planning. The killer app for onX is all of the land use and ownership data that can be presented on the map. This helps the US traveler to avoid crossing private land, or getting a hefty fine for entering State Trust Lands without a permit. There are multiple map layers, including the all-important topographical and satellite base maps. Then all of the land use and trail data points are overlaid on the screen, greatly improving navigation efficiency and route finding.

cupied by a drop-down menu on the left, which accesses account information, sharing, and version data. On the right is a search icon that has proven to be adequate in use, but needs better filtering to improve efficiency (for example, a long list of churches generates when searching for Valley of the Gods in Utah).

On the map, there is a toggle button for switching between a topo layer, satellite layer, and hybrid option. This is a quick and convenient feature that improves user efficiency. Below that is a locate button that quickly anchors the center of the map to your current location. At the base of the map are a few thoughtful touches, including a weather icon (which will expand to show a detailed weather forecast). Most notable is the brilliant and compact display of distance scale, current latitude/longitude, and elevation. The bottom menu accesses trail type, saving off-line maps, my content (tracks, waypoints, etc.), map tools, and the tracker. My problems with the app are entirely directed to the tracking feature, which has proven both unreliable and buggy. The tracking will stop randomly, and it will log erroneous track points, such as in the Atlantic Ocean, near the border of Senegal. However, I suspect this will be resolved quickly, and the rest of the app and rapidly expanding trail inventory makes it all worthwhile.

$30, ANNUALLY | ONXMAPS.COM

EDITOR’S NOTE: While onX recently hired one of our former editors, Chris Cordes, Overland Journal has no commercial association with the company.

Africais a glorious continent, and it requires a good map. That is what prompted T4A founders to start their mapping empire in 2003, providing paper maps, GPS data cards, and now mobile applications for the backcountry explorer. The amount of ground-truthed data is expansive and represents nearly two decades of user-contributed tracks. Their app has improved considerably in recent years and now provides a reliable tool for exploring trails and remote regions of the bushveld.

In use, the application is extremely rudimentary but is at least reliable and accurate. There is no tracking

Reverwas cofounded by Justin Bradshaw of Backcountry Discovery Routes (BDR) fame. Justin has traveled large swaths of the world by overland vehicle, and that is reflected in the user experience. The base app has several useful features, but the value proposition dramatically improves with the Pro version (paid). Pro activates the LiveRide function, providing active ride updates via a link you can share, and also active SMS updates to your desired contacts that receive notifications of your location (uses cellular data).

The overall look and feel of the app are perhaps the most attractive in the segment, but the free version

function, and each country or regional map must be purchased for a reasonable fee ranging from $3 to $13. Nearly the entire screen is dedicated to the map, with a top bar including an add map icon, a search bar, and filtering function. The best feature is the results icon, which will display selected POIs on the map overlay, including attractions, parks, and campsites. Despite no tracking function, the app has everything else you need.

$3-$13, DEPENDING ON THE MAP | TRACKS4AFRICA.CO.ZA

does hit you with ads and a fairly heavy push toward the Pro version. Essentially, the free version is a liability for most travelers, as you cannot export GPX data or download off-line maps, so either pay for the Pro version or stay away. The app also has an emphasis on the community aspect, with a social media undertone of challenges, shared rides, friends’ rides, and upcoming meetups. Tracking has been reliable, and the LiveRide feature and Butler Map BDR tracks are worth the price of admission.

$48/PRO, ANNUALLY | REVER.CO

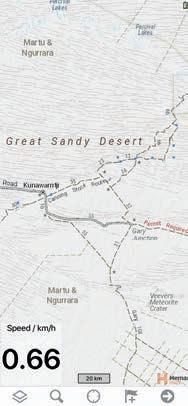

(AUSTRALIA ONLY)

Whentraveling in Australia, the only serious mapping tool is Hema, and their best offering is their 4WD Maps app, which provides complete off-line maps of the country. I have used it to cross Australia from coast to coast a few times, and though somewhat primitive as an application, you are buying the data, which is the most accurate and validated for this region of the world. The app includes 1.5 gigabytes of off-line data, including dozens of detailed base maps.

All of these maps render precise overland track routes, campsites, watering holes, and significant POIs. The main screen has only a few icons along the bottom,

including a maps menu, search function (effective), locate button, add waypoint, and toggle to the tracking/ settings screen. Tracking has proven to be reliable. The detailed maps include trail names, distances between junctions, and anticipated difficulty as represented by line thickness and dashes. Campgrounds and other services are also shown. There are a few limitations, as the maps do not allow for turn-by-turn, and additional layers come at a fee. However, there is also nothing else like it for exploring the Land Down Under.

$70/ANDROID, $100/APPLE ITUNES | HEMAMAPS.COM

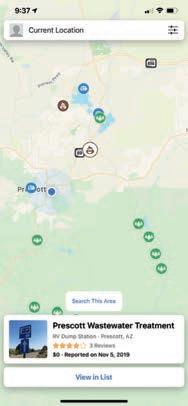

Few apps have resulted in such rapid and broad adoption as iOverlander. The app provides a collection of user-contributed campsites, campgrounds, wild sites, and traveler services. It was started as a not-for-profit by Sam Christiansen and Jessica Mans, and there are no costs associated with its use (although you can donate).

The application is intentionally simple, but admittedly buggy, including frequent crashes. However, it is difficult to complain about free, and it just takes some patience to glean the most useful data. The main map screen is where all the magic happens, and its most

Ifyou are living on the road in North America, Campendium is another useful tool for finding a place to boondock, stealth camp, or resupply. The app is well-curated and free, but it does feature both ads and paid content. The data favors RVers and trailer campers but does filter for dispersed camping.

There are several features I like about Campendium, mostly related to the user reviews of various sites and the cell coverage reports (for those of us that work remotely). Each entry has the provision for photographs and additional information like vehicle size restrictions and amenities. All of the functionality feeds

powerful feature is the filtering menu, which allows for the display of only the service or campsite type you are looking for. I have used this to find wild camping areas throughout North America, although I rarely camp at the exact spot shown (with a few notable exceptions). Other useful features are the amenity icons, which indicate if cellular data is available, etc. It also shows details on the contributor, including the date the site was last visited. This app remains one of the most useful tools for domestic and international travelers.

FREE | IOVERLANDER.COM

off the main map, with only a search bar along the top and filter icon. The filters are effective, but I would like for it to include a “cell coverage” selection in amenities. The map is easy to navigate, and the campsite or service icons are easy to distinguish for planning, including water and dumpsites. Once an icon is selected, a detail window opens at the bottom of the map with more information, including user ranking, cost, and when it was added to the database. While not specifically for the overlander, it is free and serves as another data source for planning.

FREE | CAMPENDIUM.COM

While there may no longer be blank stops on the map, there are certainly places humans rarely, if ever, visit. For those places, this is where Google Earth shines, as it allows for detailed and efficient route planning using satellite data. This is particularly useful when crossing large dune fields, or traveling in countries with poor base map data. Even on the phone (the desktop version is better for route planning), the app allows for quick pin drops, distance measurements, and, most importantly, highly detailed satellite overlays. It’s as close to ground truthing you can get without boots on terra firma.

As an app, it is both interactive and dynamic and even allows for a wonderful surprise or two. There is a

randomized POI icon called “Feeling Lucky” that flies you to an obscure and fascinating location on the planet (the last one I checked being Lake Rusanda in Serbia). To get the best from the app for route planning your next crossing of the Sahara, start in the Chrome version and build a travel project. It is far more powerful than can be described here, but it allows everything from route creation to importing images to displaying POIs. Then it all syncs across your devices. In addition, it is worth checking out Google My Maps for creating detailed route files, importing and aggregating GPX tracks, and sharing these with other travelers.

FREE | EARTH.GOOGLE.COM

Exploring Baja California, one Spanish mission at a time.

By Susan Dragoo

Clockwise from top right: The church at San José de Comondú was once the largest of all the Baja California missions, but only this side chapel remains today. Seaweed radiates an unearthly light against the black gravel beach on the Bahía de los Ángeles. Our camp at Playa La Gringa provided a satisfying sense of isolation. Spare hardware and a Hi-Lift jack always come in handy when overlanding, especially when helping another traveler. Late afternoon sun casts long shadows over tinajas, or water pockets, emphasizing Arroyo La Presa’s lunar look. Opening page: Cirios plants, also known as boojum trees, provide fascinating roadside entertainment in Baja’s Valle de los Cirios protected area. Legend has it they inspired some of Dr. Seuss’ comical characters.

Do you feel safe down there?” It’s the question we hear most often from fellow Americans regarding our travels in Baja California, and the answer is, “As safe as anywhere else.” But, really, there’s more to the story.

A tunnel of cactus constricts the dusty one-lane road leading from San Luis Gonzaga into the desert of Baja California Sur. We slow our Toyota Tacoma to a stop when the stationary rear end of a red pickup truck appears around the bend, blocking the narrow path. Three men are standing outside the vehicle. Driving around them, through thickets of thorns and needles, is unthinkable if not impossible. With no other option, we stop.

A travel alert issued by the US State Department the day before pops into my head. “Exercise increased caution in Mexico due to crime...Violent crime, such as homicide, kidnapping, carjacking, and robbery is widespread.”

The men huddle around the front of the late ’90s Chevrolet, its axle drooping on the right. My husband, Bill, walks ahead to investigate. I watch from the truck, my hand on our SPOT device, prepared to hit the SOS button. Soon Bill walks back for his toolbox, and I relax. Smelling a photo op, I grab my camera and join him at the breakdown.

“Cerveza?” One of the men offers a Tecate as I walk up.

“No, gracias,” I say. It’s early afternoon, hours before I usually imbibe. Besides, the beer is probably warm. So Rodrigo, as it turns out he is called, hands the can to a stout fellow in a red checkered shirt and brown felt cowboy hat. Jovial and gregarious, the Tecate recipient is Ricardo, and he is clearly the leader of the pack. He is also the only one who speaks any English. Rodrigo and his buddy Luis seem mostly responsible for distributing beers and otherwise following Ricardo’s instructions.

Their dirty truck has a lifted suspension and has been, as we say back in Oklahoma, “rode hard.” It now has a broken ball joint. Getting it out of the way means getting it rolling— somehow. Bill has magical mechanical skills and carries a nearly bottomless set of tools. He puts both a Hi-Lift jack and the Tacoma’s factory jack to work raising the truck. All three Mexicans drink beer as they work under the truck, seemingly oblivious to the danger. I find myself thinking of OSHA and blurting out “Cuidado” a time or two as I watch. Bill keeps an eye, and a hand, on the Hi-Lift as he offers Ricardo tools and mechanical advice, which makes me feel better.

Ricardo’s English is good but limited, and my Spanish is bad and very limited, but we manage to carry on a conversation. He says he’s been out buying horses for a rancho, but I later speculate the trio might have just gone to town for cerveza.

I tell Ricardo we are out exploring Spanish missions, revealing my interest in history, and soon he pulls out a large point knapped from local stone, which he says he found while running in the mountains. It is 5 or 6 inches long and in pristine condition. I admire it, curious about its age and origins and a little dubious. I show him our intended route on the map, east through the desert to San Evaristo, a fishing village on the Sea of Cortez, from which we will launch our southbound leg toward La Paz. “Go see my friend Lupe Sierra. He has a restau-

rant in San Evaristo,” Ricardo says. We promise to do so.

After about an hour working in the sun and several Tecates, the hombres get the vehicle rolling. Ricardo and the boys head off down the trail into the desert. Bill and I aren’t far behind, followed by a family in a small, white pickup who has been stranded behind us. About a mile farther, our friends’ red truck reappears. The repair failed, and they need a ride. At least they got the truck out of the road.

“Can you take us to Las Tinajitas?” asks Ricardo.

“Of course,” says Bill. There’s no room in our back seat because it has been removed and replaced with toolboxes and an air compressor, and is otherwise filled with luggage. So Ricardo, Luis, and Rodrigo climb atop our truck-top tent, mounted over the bed of our Tacoma. They leave everything behind in their pickup, except for a #3 washtub full of Tecate and ice, covered with an old canvas, which they squeeze beneath their feet atop the water tank in the truck bed. The beer is cold, after all.

Like a homecoming queen and her court on the back of a red convertible they ride, three abreast. Ricardo (who acknowledges his speedy driving contributed to the truck’s demise) actually shouts, “Andale.” Bill finds a radio station playing mariachi music and turns up the volume, adding to the cacophony of yelling Mexicans and road noise.

Before we reach Las Tinajitas, we stop at a rancho where Ricardo thinks he might get help. Luis and Rodrigo haul out the beer tub and stand next to it in the shade, having another Tecate while Ricardo checks on things. It’s a no-go here, so the amigos load up the washtub and themselves again, and we continue on to Las Tinajitas. Bill is in the spirit of things as he drifts around tight turns in the dust and bumps over the rocky roads. I hope the boys won’t fall off. They keep up a constant string of loud chatting and shouting, so it’s hard to tell whether they are happy or distressed.

For the last month, weʼd been camping along the Sea of Cortez—waves lapping, sometimes crashing, a few feet from our camp. Sunrises were so intense I would lie awake and wait for them.

At Las Tinajitas, Luis and Rodrigo wait to unload the washtub, but Ricardo confirms he can get a ride from there; they pull their precious cargo out of its slot. Our new friend reminds us to look up Lupe Sierra when we get to San Evaristo. Bill and I hug all three and wave as we drive off, hoping Ricardo receives the help he needs, already feeling parental toward the young men.

Bill and I had been exploring back roads for nearly a month in Baja, a place almost entirely new to us, camping along the Sea of Cortez—waves lapping, sometimes crashing, a few feet from our camp. Sunrises were so intense I would lie awake and wait for them.

We had escaped Oklahoma right after Christmas, bringing maps, GPS, guidebooks, and sound advice from knowledgeable friends, but consciously avoided making an itinerary. There was no scrimping on the truck, however. It was already fit for rough off-pavement use, and Bill had spent weeks modifying it further

for this trip. He’d added a 30-gallon water tank and onboard hot shower, obviating my usual need to find a hotel after a couple of days of camping. My mother said the truck was turning into a motorhome, with its shower, rooftop tent, and refrigerator. I suggested we not say that to Bill.

Bill and I had crossed the border in Mexicali, driving south on Highway 5 with the general intention of traveling along the Sea of Cortez. The peninsula of Baja California protrudes nearly 800 miles into the Pacific Ocean south of the US state of California and west of mainland Mexico. Between Baja and the mainland, the Sea of Cortez, commonly known as the Gulf of California, is 150 miles across at its widest point. Its beaches are rumored to be warmer than those on the Pacific side, an attractive proposition for us.

With any journey, a direction of travel and goal of some sort must emerge. On our third day in Mexico, we met with a Bajasavvy fellow overlander, also a history buff, who recommended a couple of backcountry tours to Spanish missions.

Twenty-seven Catholic missions were founded by the Spanish along the length of the peninsula of Baja California, between 1697 and 1834. The state of these buildings today varies greatly. Some are well preserved and still in use as churches;

others have altogether disappeared into the rugged landscape. Many are somewhere in the middle.

By the time we reached San Luis Gonzaga, we had done the “easy” mission tour, first visiting San Borja, the northernmost stone mission church on the peninsula. There, we toured the beautiful structure, completed around 1801, with Angel, a member of the family who takes care of the historical site, and saw the ruins of the original adobe brick church, circa 1768. We slept in a palapa in San Javier, a mountain village anchored by Misión San Francisco Javier de Viggé-Biaundó, completed in 1758. This one is Baja’s best-preserved original mission and continues to function as a church. And, we’d made a brief stop at the remains of San José de Comondú, founded in 1708 and eventually built into a massive cut-stone church complex at its

Clockwise from right: Angel, our guide at Misión San Borja, greets visitors at the entry portal to the church’s sanctuary. A maze of sand on the Pacific Coast in Baja Sur turns our Tacoma into an amusement park ride. Misión San Francisco Javier de Viggé-Biaundó, built from 1744 to 1758 of cut volcanic rock, is still a thriving part of the community it anchors. Opposite: A cut-stone spiral staircase at Misión San Borja, completed in 1801, leads from the vestibule to the choir loft.

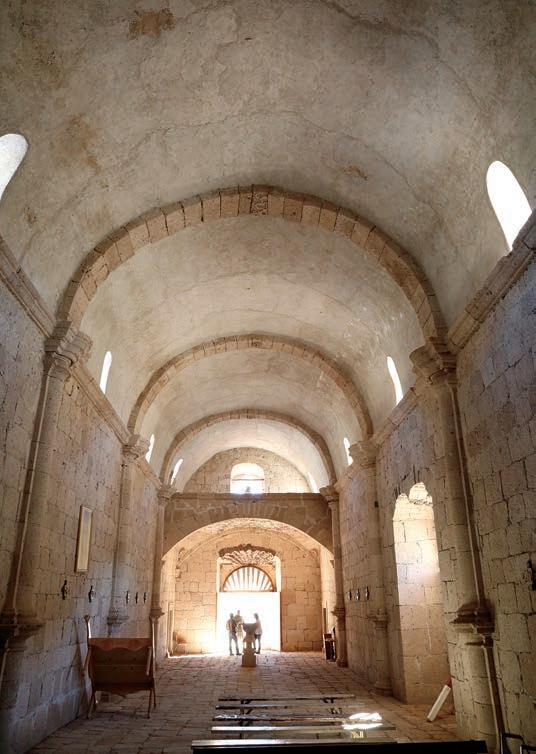

Clockwise from top right: Just when we think we’re completely alone in the middle of the desert, a group of singing vaqueros rides by on their evening commute. A broken chalice and dusty crucifix suggest Misión San Luis Gonzaga has seen better days. A butte near Arroyo La Presa dominates the landscape. Roofless walls of the priests’ quarters and a mission annex stand adjacent to Misión San Luis Gonzaga. Humble wooden pews still serve villagers who worship beneath the barrel-vaulted ceiling of Misión San Luis Gonzaga, completed in 1758. Opposite: Our little Tacoma is the perfect pack mule, allowing backcountry access on the most challenging trails.

final location. It was the largest mission church in all of California but fell into ruin and was demolished in 1936. A side chapel to the main building was preserved and is all that remains. None of these were difficult to reach.

Today, we began a more challenging route, starting in San Luis Gonzaga, which is not much more than a dusty street running alongside a handful of impressive buildings—out of place and now abandoned—and a neglected church still in use. Misión San Luis Gonzaga was the last mission founded in the southern half of the Baja peninsula. The stone church, completed in 1758, remains intact.

I photographed the church after lunching on papaya we’d picked up in Ciudad Insurgentes a few miles back on Highway 1, and Bill chatted with two motorcyclists from the States. They were also passing through, before continuing into the desert toward the Sea of Cortez.

Up and over the coastal mountains, we ascend to a spectacular view of the Sea of Cortez before creeping down a track so steep, rough, and rocky we bet no other motorized vehicle had used it in months.

After the encounter with Ricardo’s bunch, we begin a campsite search as the sun winds down. A promising side road leads us to the bank of Arroyo La Presa, a mostly dry streambed of gray stone punctured by tinajas, or cavities holding water, making the terrain look oddly lunar.

The singing vaqueros are a complete surprise, but pleasant as surprises go. As Bill and I are cooking dinner at dusk, melodic voices arise in the distance. The music floats closer, backed by a clip-clop percussion, and soon three cowboys on horseback appear on a trail we hadn’t noticed. We wave nervously, concerned we might be trespassing. The vaqueros wave back and continue on their path. Headed home, we surmise, from the day’s work at a nearby rancho.

Cowbells clunk gently all night, confirming the proximity of bovines. At sunrise, the vaqueros pass by again, going in the opposite direction. Soon, a young man on foot stops on his way. He speaks no English. We offer him coffee, which he accepts, but when we can offer no leche or azucar (milk or sugar, we drink it black), he smiles and hands it back. A third fellow rides by on a small horse, also stopping to say hola. The trail, invisible to us, has turned out to be a major thoroughfare.