VERLAND O

WE ARE ADVENTURERS Constantly traveling. Testing and using gear in real-world situations. Gaining experience, which we readily share.

OUR RESUME

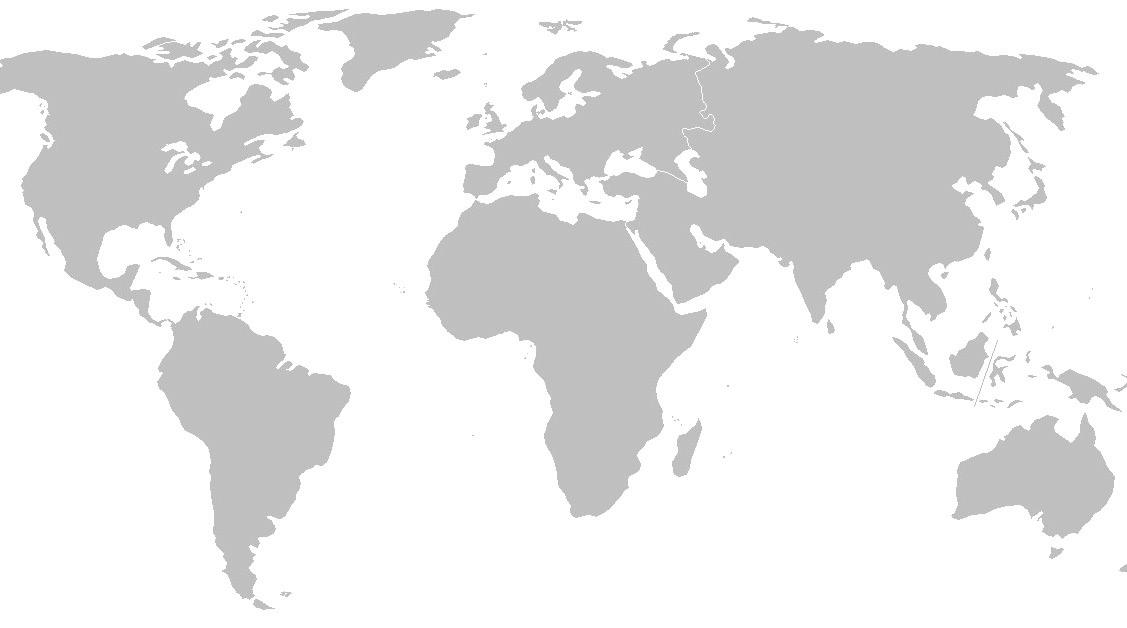

7 continents | 161 countries | 496 years combined experience

WE ONLY KNOW THINGS WHEN WE LIVE THEM

PUBLISHER AND CHAIRMAN Scott Brady

DIRECTOR OF DESIGN Stephanie Brady

CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Christian Pelletier

CHIEF BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT OFFICER Brian McVickers

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Andre Racine

DIRECTOR OF EUROPEAN OPERATIONS Michael Brailey

EDITOR IN CHIEF Tena Overacker

SENIOR EDITOR Ashley Giordano

SENIOR EDITOR Matt Swartz

MEDICAL EDITOR Dr. Jon Solberg, MD, FAWM

ARCHAEOLOGY SENIOR EDITOR Bryon Bass, PhD

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Graeme Bell, Åsa Björklund, Antonia Bolingbroke-Kent, Cody Cox, Rocky Donati, Susan Dragoo, Paul Driscoll, Roger Gaisford, Dan Grec, Jennie Kopf, Jack Mac, Karin-Marijke Vis, Kirk Williams, Lisa Williams, Michelle Francine Weiss

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER Bruce Dorn

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Chris Burkard, Kasper Høglund, Coen Wubbels

COPY EDITORS Arden Kysely, Jacques Laliberté

TECHNICAL EDITOR Chris Ramm

CARTOGRAPHER David Medeiros

PODCAST HOST Matthew Scott

PODCAST PRODUCER Paula Burr

VIDEO DIRECTOR Ryan Keegan

OPERATIONS MANAGER Garrett Mead

CONTACT

Overland Journal, 3035 N Tarra Ave, #1, Prescott, AZ 86301 service@overlandjournal.com, editor@overlandjournal.com, advertising@overlandjournal.com, 928-777-8567

MOVING?

Send address changes to service@overlandjournal.com. Include complete old address as well as new address. Allow two to four weeks for the change to become effective. Overland Journal is not forwarded by the US Postal Service. It is the subscriber’s responsibility to inform Overland Journal of an address change.

Overland Journal is a trademark of Overland International, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Overland Journal is a wholly owned subsidiary of Overland International.

We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.

SPARE PART PUZZLE

Thank you for your recent podcast on overland expedition campers; it was very interesting. One question that I don’t think you addressed is how suitable for international travel are campers based on American trucks (F-350, etc.)? Some people seem to think that getting spare parts for them in Zambia or Mongolia would be difficult compared to, say, a Fuso-based vehicle.

Jeff Kinney

RESPONSE

The original Fuso is an excellent choice for international travel, as the chassis and drivetrain were shared with global offerings. Unfortunately, newer Fusos now use domestic engines and transmissions and no longer benefit from that worldwide serviceability. In general, most large expedition campers of any make suffer from parts obscurity

and often require parts and even technicians to be flown in for significant repairs. -Publisher and Podcast Host Scott Brady

INTRIGUED

Fall 2021’s “Purchasing an Overland Icon” was a fun article about [Cody Cox’s] journey finding and purchasing the Toyota. Please consider incorporating specific aspects of this class/model vehicle that make it particularly well-suited for overlanding.

Also, is the way the snorkel mounted to the airbox in the engine compartment a screwup with the OEM canister design that would normally spin dust out of ingested air? Or is it a factory-supplied snorkel?

Mark Grunenwald

ROW 1

@wagon_life

Chronicles of summer.

@theroadtozero

A Balkan backroad at its finest, somewhere in North Macedonia.

@overlandsite

Coffee and a good read in the morning.

ROW 2

@somewherewilder

We don’t know anyone who takes snuggling as seriously as Henry.

@autoturisti

Set in a beautiful Apurímac valley and at 3,700 meters above sea level, Q’eswachaka is the only remaining handwoven Inca bridge.

@yakoverland

Still finding sand in our shoes two days later.

ROW 3

@bicycle_touring_apocolypse

Jannis, aka @coco.overland, is the owner of this @expeditionportal featured vehicle, a BMWpowered 1987/1997 Defender featuring a 1969 Land Rover Series II ambulance body and a suspension setup that would make Dakar drivers blush.

@suboverland

Food always tastes better when it’s cooked on a Coleman stove out in nature. Our family does Shiner Night, where we take the labels off a bunch of canned food, and you eat what you get—it’s always memorable.

@offgridtrek

The weekend is getting closer.

RESPONSE

The air intake system is largely stock with only two exceptions. First, the pre-cleaner for this older, square-bodied factory snorkel would normally have been a cyclone style. The second modification required a bit of cutting and welding to connect the air filter housing to the turbo crossover pipe. The Troopy is currently undergoing a full engine rebuild and interior revamp. Upon completion, an in-depth article will be written detailing the mindset behind modifications. -Cody Cox

SHARE

Use #overlandjournal on Instagram or Facebook.

WHERE HAS YOUR OVERLAND JOURNAL BEEN?

Send us a photo, along with your name, the location, make/year of your vehicle, and a brief description. editor@overlandjournal.com

Kirk Williams is an adventure photographer, overlander, dreamer, and quadriplegic. He has traveled the entire United States of America numerous times, making his way as far north as Fairbanks, Alaska, and as far south as Ushuaia, Argentina. While traveling, Kirk sets an example for other wheelchair users to learn from. He uses photography to showcase the high moments as well as the challenges faced with being on the road while being a quadriplegic. In 2018, Kirk founded Impact Overland. Impact Overland’s goal is to teach others about adaptive overlanding while also raising awareness and fundraising to help bring mobility to those who can’t afford such equipment as a wheelchair.

Antonia Bolingbroke-Kent is a travel writer and broadcaster with a particular love of wandering alone through remote regions. The author of three books, she’s raised more than £60,000 for charitable causes and once held the highly competitive Guinness World Record for the longest-ever journey by auto-rickshaw. Her latest book, Land of the Dawn-lit Mountains, was Shortlisted for the 2018 Stanford’s Travel Book of the Year. Antonia writes for the Telegraph, Financial Times, Wanderlust, the Guardian, and Radio 4’s From Our Own Correspondent. Her first radio documentary was aired on BBC Radio 4 in early 2020. In 2019, she was the recipient of the Royal Geographical Society’s prestigious Neville Shulman Challenge Award. She used the grant from this award to fund her latest Naga expedition.

Graeme Bell was born in Johannesburg, South Africa. Together with his wife and two children, he has spent much of his adult life chasing momentous experiences and campfire smoke across five continents. He has traveled overland to Kilimanjaro from Cape Town, circumnavigated South America, explored from Argentina to Alaska, Europe to Asia, and across the entirety of coastal Western Africa, all in a trusty Land Rover. Graeme and the family are now encouraging their self-built Defender livein camper (and permanent home since 2012) to find a way from Cape Town to Vladivostok. Graeme is a member of The Explorers Club, the author of five excellent books, and an Overland Journal contributor since 2015.

Freelance writer Karin-Marijke Vis, along with her partner, photographer Coen Wubbels, combine their love for adventure with work they enjoy. Sometimes described as being the “slowest overlanders in the world,” they believe in making connections and staying in a place long enough to do so. In 2003, the couple purchased an antique BJ45 Land Cruiser and began a three-year trip from their home in the Netherlands to Asia. Terminally infected by the overland bug, they traveled in South America for nine years, and in Japan and South Korea for two years. They are currently making their way through Russia and Central Asia. They’ve been published in magazines around the world, and in 2013, Expedition Portal awarded the pair the coveted Overlander of the Year award.

No money in the bank, but gas in the tank. Our resident Expedition Portal Bikepacking Editor Jack Mac is an exploration photographer and writer living full time in his 1986 Vanagon Syncro. He spends most days at the garage pondering why he didn’t buy a Land Cruiser Troopy. If he’s not watching the Lord of the Rings Trilogy, he can be found mountaineering for Berghaus, sea kayaking for Prijon, or bikepacking for Surly Bikes. Jack most recently spent two years on various assignments in the Arctic Circle but is now back in the UK preparing for his upcoming expeditions—and looking at Land Cruisers. Find him on his website, Instagram, or on Facebook under Bicycle Touring Apocalypse.

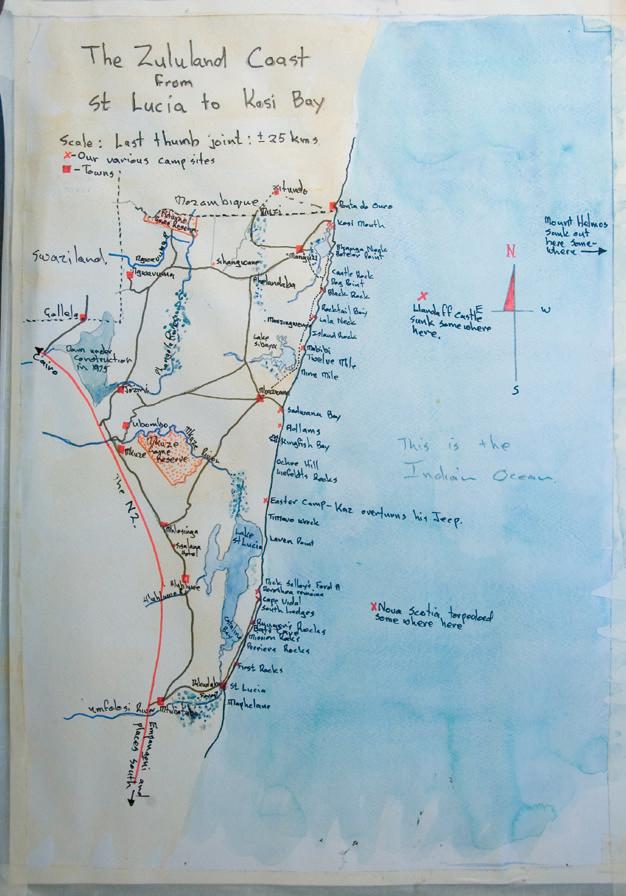

I am a somewhat aged South African who grew up and went to school in Pretoria. After military service in the South African Navy, I completed a BA degree at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, majoring in history, archaeology, and African languages. I worked as a mineral prospector in South Africa and Botswana before marrying Anne Louise. We settled in Eshowe, Zululand, where I took up a teaching post. I have a son, John, and daughter, Lizzie, and a passion for boats and old Willys Jeeps. I am now retired and spend most of my time rebuilding jeeps, enjoying wild travels in Southern Africa, and writing.

Dan Grec is an adventurer, snowboarder, and photographer who now hails from Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada. Growing up in Australia, family camping trips gave Dan a passion for wilderness exploration in remote destinations. After studying and working as a software engineer, Dan went in search of a more vibrant life. Eventually driving 40,000 miles from Alaska to Argentina, he became inspired by the characters he met along the way and is now dedicated to helping others realize their own overland dreams. To this end, Dan created and maintains WikiOverland—the community encyclopedia of overland travel. After years of planning and preparation, in early 2019, Dan completed a circumnavigation of the entire African continent in his Jeep Wrangler Rubicon.

At the age of 22, Kasper sold everything, including a city apartment, and cut all ties to normal life. As a photographer, he wanted to be as free as possible. And that’s when a Land Rover came into the picture. Kitted out, Kasper headed for the Arctic, where he lived out of the truck for more than a year. Now he’s back in Norway, having built out the vehicle for greater adventures. The photographer didn’t really plan for the traveling to become this frequent. Nor did he think he’d be doing it for this long. But now, it is hard to go back. Some big trips and a second build are already in the works.

Rocky has a quirky sense of humor, the mouth of a sarcastic sailor, and talks supersonic fast. Her insatiable drive and knack for creative problem-solving meant a decade of spearheading high-level business strategies for the outdoor industry. Now she manages her own consulting firm, Donati Agency, but more often than not, elects to play hooky with her partner in crime and two Aussie pups. From wheeling to jet-setting out of a remote Park City chalet at 8,000 feet, she and her husband are constantly in search of the perfect pocket water for fly fishing. This decade, she’s embracing the hermit lifestyle, writing gibberish for hire, and renting out the adventurous getaway of your childhood dreams, The Treehouse Utah, on Airbnb.

Chris Burkard has seen more of the world than most of us could hope to see in several lifetimes. He has always gone his own way, impelled by his idiosyncratic desires. Often referred to as a surf photographer, Burkard describes himself as a landscape photographer with a peculiar relationship to the sea. He has published several books including The California Surf Project (co-author Eric Soderquist), The Boy Who Spoke to the Earth, High Tide: A Surf Odyssey, Distant Shores, Under An Arctic Sky, and his latest, At Glacier’s End. Burkard’s work has been published in National Geographic, the New Yorker, GQ, Men’s Journal, Vogue, and Surfer Magazine. Chris and his wife, Breanne, live on California’s Central Coast with their two sons, Jeremiah and Forest.

Shedding light on the obscure, especially at the juxtaposition of man and nature, drives Susan Dragoo to explore the historical treasures of the American Southwest. On wheels or afoot, an old trail and a camera are her key ingredients for a fulfilling adventure. A writer, photographer, and student of history since youth, Dragoo’s work is found in motorcycling, 4WD, hiking, and other travel publications, and her scenic photography in state park lodges and cabins in her home state of Oklahoma. Gallivanting in their Toyota “Tacoma GS” is a favorite pastime for Susan and her husband, Bill, when they are not at home in Norman, Oklahoma, enjoying their family and running Dragoo Adventure Rider Training (DART).

Born and raised in southwest Montana, Paul Driscoll has lived and worked throughout the West as a newspaper reporter, technical writer, editor, illustrator, and website manager. He is a fair backcountry skier, a passable dry-fly fisherman, and a damn poor elk hunter. He currently lives outside of Helena, where he develops natural history and travel articles for regional and national publications, including New West, the Washington Post, and Weber—The Contemporary West. Paul is currently working on a collection of natural history essays, due out soon. He has owned a 1965 Series IIA Land Rover for almost 35 years and estimates that many of its 250,000 miles have been racked up on two-track dirt roads to nowhere.

Cody Cox is a driver and an aficionado of the inline-six engine. He thrives on the creative environment surrounding vintage vehicles and the stories they often help create. Through his travels, he has become an acquaintance of roadside breakdowns and tow trucks. Behind the wheel of an analog vehicle is where he feels most comfortable. As a member of the Toyota Troop Carrier ranks, he relishes each occasion to open the engine bay and turn a wrench on his 1985 HJ75. The mingling scents of sagebrush and diesel are the fuel that drives him as he explores the high deserts of the American West.

Swedish-born, Åsa has roamed the globe working as a waitress, a factory employee, and a dozen other odd jobs “that made life more interesting.” As a human rights lawyer, she worked with development aid in Central America. When she escaped the office, she explored the remote areas of Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, and Honduras in a Land Rover. With a desire to write full time, she switched careers to journalism before returning to the nonprofit sector. Her work includes topic articles for international magazines covering overland travel, wildlife, current affairs, and social issues. Åsa has a love for animals and a particularly soft spot for horses. Whenever she can, she explores the Colorado backcountry with the help of Desert Daisy, a 1987 Land Cruiser FJ60.

Lisa Williams is an Arizona native that spent much of her childhood exploring backroads with her family in whatever project vehicle her father was wrenching on at the time. She has traveled the continental United States by foot, by Ford Econoline, and most recently, by Jeep Cherokee. All her passions center around driving, connecting with nature, and a deep love for adventure. Though a practicing weekend warrioress, she aspires to write, photograph, and eventually rally race around the globe and share her journeys through photojournalism. Upcoming goals include competing in the Rebelle Rally, the Baja 1000, and an immersion into the less-traveled roads of New Zealand in her 2019 Toyota Tacoma.

I love to cook and grew up on a resort in northern Minnesota. We fed our summer employees, and when I got old enough, my Mom gave me the option to cook or clean up—I cooked. I started catering over 25 years ago when my kids were very young, and my little cottage industry bloomed into a full-blown biz when they got older. My family enjoys having great food when we are out under the stars, and I enjoy making that happen. We own Colorado Backcountry Trailers, and I helped design the kitchen for the off-road trailer—it allows everyone to come together to create something spectacular, the perfect recipe for dining en plein air.

Michelle is an architect; partner Roy is a businessman. But when work inside four walls no longer provided them much satisfaction, they took courage and dropped normal life in their home country of Brazil. They decided to search for their true passions and left for two round-the-world expeditions by truck. The wealth of information provided by the six years away from home led them to the decision to share their experiences in the most diverse ways. And so, they became photographers, writers, and speakers—disseminating the cultural diversity of our planet. They are the authors of Mundo por Terra or World by Land, detailing their travels and adventures.

Overland Journal is the original publication for environmentally responsible, worldwide vehicle-supported expedition and adventure travel.

SUBSCRIPTIONS AND BACK ISSUES

5 issues/year, online at overlandjournal.com or 3035 N Tarra Ave, #1, Prescott, AZ 86301

DOMESTIC & CANADA (USD)

1 year $45, 2 years $80, 3 years $112

EUROPE (EUR)

1 year €45, 2 years €80, 3 years €120

INTERNATIONAL (NON EU) (USD)

1 year $75, 2 years $140, 3 years $202

DIGITAL

Available on iTunes, Google Play, and the Zinio newsstand.

It’snot an exaggeration to say that the Flex Canvas pants from Livsn Designs have quickly become my go-to apparel choice for just about anything other than winter sports. They are made from 7.3-ounce EcoFlex duck canvas which is 58 percent GOTS certified organic cotton, 40 percent recycled polyester, and 2 percent spandex. The name Livsn comes from the Swedish saying livsnjutare, which basically means one who loves life deeply—an enjoyer of life. While I certainly feel like this phrase describes me well, the bigger story here is the sustainable approach and smart features behind the Flex pants.

Starting with a mix of environmentally conscious stock materials, Livsn creates garments that are designed to last. Their prices are not what I would call inexpensive, but they reflect a more responsible supply chain and labor practices. Unlike an $18 pair of fast-fashion pants that will only last you a few months of regular use, a $99 pair of Flex Canvas pants will last you for years. And if they wear out prematurely, the company’s rock-solid warranty guarantees a refund, repair, or replacement for free. If you happen to be extra demanding of your clothing and need some repairs from normal wear and tear, Livsn also has you covered with repair services at cost (no markup).

A pair of Flex Canvas pants will last you for years. And if they wear out prematurely, the company’s rock-solid warranty guarantees a refund, repair, or replacement for free.

Upon initially receiving the Flex pants, I was surprised to find that they were stiffer and more robust than I anticipated. But after one wash, they took on a more supple, comfortable-on-the-skin quality. Their tailored fit is both flattering and functional, and they don’t restrict my movement during activities like hiking or scrambling. While they do have a very minimal stretchy quality to them, they haven’t stretched out over time like many natural-fiber garments I’ve tried. Because of their comfort and fit, I often find myself wearing them for an extra day or two instead of reaching into the dresser for a clean pair of pants.

The overall design of the Flex feels well-thought-out, with reinforced heel cuffs, strategic bar-tacks, a gusseted crotch, and plenty of pockets. The interior of the front pockets is constructed with a synthetic mesh which breathes nicely and reduces bulk. Additional partitions within the front pockets help keep a cell phone or keys from bouncing around excessively. I especially appreciate the EDC pockets that sit just outside both thighs, the perfect place to unobtrusively stow a small knife or pen. Recessed zippers on the rear pockets provide heightened security for a wallet but aren’t uncomfortable for sitting. The only feature that I found difficult to use is the roll-up leg system which feels uncomfortably snug on my calves.

$99 | LIVSNDESIGNS.COM

Practical, durable comfort in an environmentally friendly package.

Asoverlanders, we are determined to leave little physical evidence of our interaction with nature. We seek to preserve the beautiful spaces we are fortunate enough to visit, and hopefully, leave them better than when we arrived. Fireside Outdoor, founded in 2016 in Phoenix, Arizona, shares these goals and aims to help others Leave No Trace. For heat, cooking, or just for ambiance, the Pop-up pit lets you add fire to your adventures while leaving no impact on the ground.

This attractive fire pit is designed so you take the remnants of your fire away, ashes and all. Once your fire is extinguished, the innovative materials of the pit cool quickly, making fire dispersal hassle-free. It can be used with an existing fire ring or in places without access to a designated fire area such as remote camping, on a deck or patio, at a beach cookout, glamping, or even on a multi-day rafting trip. The included heat shield prevents heat from reaching the ground and causing damage to other surfaces.

Though devised for repeated heating and cooling cycles, some discoloration is expected over long-term use of this product. I noticed the fire mesh had permanent burn marks after the first use, but this adds to the unit’s character. Constructed with durable aluminum and stainless steel, the fire pit is lightweight at 8 pounds, despite its size of 24 x 24 x 15 inches.

For heat, cooking, or just for ambiance, the Pop-up pit lets you add fire to your adventures while leaving no impact on the ground.

The frame expands with little effort but remains sturdy once opened. No tools are needed for assembly, though I found the fire mesh somewhat difficult to place. Lifting the individual corners was not easy, and the mesh does not stretch, but it does provide a sturdy base to build a fire up to 100 pounds, including fuel and ash. The mesh provides the fire better oxygenation, and in turn, produces less smoke.

Four ember guards reduce the risk of errant sparks causing wildfire. The ember guards are lightweight aluminum and are compliant with Bureau of Land Management, United States Forest Service, and National Park Service guidelines. Each ember guard is L-shaped and 24 x 4 inches; the fire should be kept an inch or more away to allow air to flow properly.

A convenient black carrying case with a shoulder strap makes for easy storage and transport. It will protect your ve-

Keep your campfire off the ground with this compact, portable solution.

hicle from any residual ash or soot, though I would prefer the same material as the case for the optional 24-inch Tri-fold Grilling Grates.

The stainless steel Tri-fold grates can hold up to 75 pounds of food and provide a 23.5- by 16.25-inch cooking space; boil water for pasta while simultaneously grilling vegetables or meat on the side. My first setup took around three minutes through trial and error, with one minute designated to reading the instructions; setup is possible in less than a minute, though. Cleanup is a cinch, and an included vinyl carrying case packs the grill grates to 23.5 x 5.5 inches.

POP-UP FIRE PIT/$120, TRI-FOLD GRILLING GRATES/$80 | FIRESIDEOUTDOOR.COM

Setting up the Pop-up pit is straightforward and protective of any terrain. Right: The heat shield effortlessly protects Arizona’s arid forest ground.

Simple, well-thought-out tools that improve our cookhouse experience, both outdoors and in.

WhenI think about ways to add enjoyment to my cooking experience, it’s nearly always about a new recipe or a fresh set of knives. Maybe even some new pans, but a spatula was never on the list. Earlier this year, I had the opportunity to test out Dryad’s lightweight titanium spatula, and I was pleasantly surprised at the experience. The off-centered design seemed slightly odd at first, but it quickly became apparent this was a purpose-built tool. The flat tip slices right under food when stirring, and the offset 20-degree ergonomically designed lift handle provides access to a whole new way of scooping food onto your plate. When you are really going at it on a cast-iron pan, the spatula has the perfect amount of flex. It’s available in three colors with options for both left- and right-handed users. The spatula set rounds out nicely with the addition of a Dryad leather skillet handle cover. The material is quite stiff upon arrival, but a few minutes of working it by hand results in a pliable grip. The leather conforms nicely to the handle and is thick enough to attenuate the heat of even the hottest pan. And since they are made of leather, you know they will age nicely. (CC)

SPATULA/$54, HANDLE COVER/$15 | DRYADCOOKERY.COM

A dash of reality with a sprinkling of research and backcountry access is unlocked.

Iamnot an experienced backpacker, but I enjoy high-alpine fishing, and if my truck can’t get me sleeping next to water for prime-time dawn strikes, out comes the inevitable. Like any new hobby, I often allow the (not so accurate) influencer interpretation of myself to buy gear for its never-used fancy features, but not this time. I recognized that I was never going to be Cheryl Strayed tackling the PCT; I only wanted 35 pounds to feel like 25 pounds. So here is my self-proclaimed pro take on why Mystery Ranch should be every woman’s trail life genesis.

Because no two ladies’ curves twin, the hip belt is the sole makeor-break attribute. Cushy is crucial to prevent hot spots and minimize pressure points, but only a custom-tailored fit can ensure it doesn’t get sloppy under load and retains that magical weight reduction capability. Mystery Ranch solves this primary requirement instantly because you can swap out the belt for different sizes, mak-

ing a stock pack feel like a bespoke kit. All other decisions are pure seasoned preference, and newbies shouldn’t stress any of it. I will say, however, that since my conditioned need to never be without a purse doesn’t end while traversing the wilderness, I truly dig the Stein’s detachable daypack, which acts as a lid when connected, but doubles as a smaller grab-and-go transporter. It’s fantastic for ditching anything heavy while on my quest for cutthroat. And that’s your official green light from a fellow rookie on how to get outside without feeling like an overburdened mule. (RD)

$299 | MYSTERYRANCH.COM

TheE-Clik starts with a Made-in-USA shock, manufactured and assembled by SDi using a combination of in-house (and locally machined) parts, and adapted electronic components. Next is the proprietary touch-screen controller that replaces the transfer case shifter on the Jeep JL, incorporating a touch screen and dial configuration to review and change settings. The system is controlled by an ECU that gathers data from 12 different inputs, including the supplied eight-axis inertial measurement unit. The system adjusts the damping of all four shocks in real time, autonomously and transparently, with no input needed from the user. Additionally, there is a user-selectable Road Mode and Trail Mode. For advanced users, the system allows extensive manual (via the touch screen) adjustability and sensitivity biasing.

To accommodate for a heavy overland load, the E-Clik has a provision to adjust the rear valving based upon a percentage of available payload. It’s a significant advantage for backcountry travel as the Jeep can run daily driver duties with little gear onboard and then be adjusted for a travel load.

Another use case that immediately came to mind is a dynamic roof load. During my testing of the E-Clik, I conducted a series of tests to help simulate dynamic handling scenarios and body

Proprietary electronics and tuning offer seamless adjustment and control.

control conditions, which included higher speeds on the dirt with the sway bar disconnected. With a loaded roof rack or a roof tent (hopefully, never both), the E-Clik is able to adjust the dampers automatically to limit sway and help keep the hood flat through transitions at speed. It is particularly noticeable with the rear suspension, as most roof loads will have a rear bias. I was able to adjust the system by increasing the pitch sensitivity and upping the rear load percentage.

In cross-axle terrain with the sway bar disconnected, it was impressive to watch the system actively adjust throughout an articulation event, firming a corner as it dropped into a hole and loosening a lightly loaded corner. This was also evident during side slopes, where the system would firm the downslope dampers to minimize compression of the loaded (downslope) springs. We pushed right up to a 30-degree side slope at various speeds to gauge effectiveness, and it was confidence-inspiring.

The system adjusts the damping of all four shocks in real time, autonomously and transparently, with no input needed from the user.

In a high COG, lifted 4WD with largediameter tires, the result is usually some degree of “lively” handling and a lot of driver fatigue. This is where the E-Clik shines, providing relaxed valving while cruising along but adapting within 1/250 of a second during an emergency lane change. I pushed the JL through multiple limit handling situations, including hard braking in a turn, lift-throttle events, lane changes, and more. During each of those scenarios, the Jeep remained predictable and composed. The E-Clik cannot overcome physics, but it does move the limits much closer to the edges.

Overall, the SDi E-Clik system is genuinely revolutionary, incorporating technology not currently available in the segment. As a last consideration, the Pro system is an investment, something that should always be weighed against the goals of the traveler. Technology at the fringe of the future is never cheap—but it can make all the difference.

$4,999 | ECLIKSHOCKS.COM

Integrating the controller into the 4WD shifter is an impressive result, putting adjustability at your fingertips. Due to the adaptive nature of the shocks, they can be paired with nearly any lift spring and alignment bracket combination.

Dwarfed by the rock formations of Kazakhstan’s Mangystau region.

By Karin-Marijke Vis

LIMESTONE ROCK FORMATIONS REFLECTING IN THE WATER, islands rising from the salt plains, mountains streaked with greens, purples, and reds, and spherical rocks spread all around us for hundreds of meters. This is the Mangystau Oblast, arguably the most surprising part of Kazakhstan and a true paradise for overlanders.

The Mangystau Region is bordered by the Caspian Sea on the west, the Aral Sea in the northeast, and Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan in the east and south, and has never been a densely populated region. Although there is some evidence of sites dating from the Neolithic Period, the first written records date only from the 9th century AD. From then on, the Mangystau Region has been inhabited by Turkmens, Mongols, Kazakhs, and Russians.

Testimony to those early days of settlement includes the underground mosques that may once have been remote locations for Sufis to be closer to God. Cemeteries are scattered across the dry plains, varying from tombs of a few rocks to boastful mausolea and fairytale domes. From the immense necropolis of Koshkar Ata just outside Aktau (the capital of the Mangystau Region) to cemeteries of just 25 graves, all have eye-catching kulptyas. These carved stone columns or decorated stone tombstones tell us whether the deceased was a good Muslim, a young woman, or a warrior. Unattended for many centuries, many of the tombs and kaytas tombstones in the form of stylized sheep—have partly sunk into the ground or have been eroded by the fierce winds that howl across the plains.

With the discovery of oil and gas deposits, the region has attracted an influx of new habitants. Donkey pumps nod in formation as you drive the few asphalted roads that cut through the plains. You will be driving nearly exclusively on unpaved roads, though. For hours, days even, you may be shaken apart on rutted tracks that cut through the clay desert covered with low-growing scrub with the sporadic appearance of a small tree. Distraction in the sometimes monotonous terrain is found in the camel herds; these fierce animals are most beautiful when enveloped in their thick winter fur.

Wild horses also dot the landscape and scatter as soon as our drone leaves the ground. The noise cuts through the silence of the Ustyurt Plateau, which covers a large part of the Mangystau Region (77,000 square miles). Suddenly the plateau ends, and you may find yourself on a cliff edge looking out over limestone deposits that have been transformed into

spellbinding rock formations; it’s hard to tear yourself away from such sweeping views. Trails and unpaved tracks zigzag up and down the valleys, taking you deeper into the dried-up bottom of the sea and through the Valley of Balls, where thousands of spherical rocks lie scattered across the desert land.

Amidst all this beauty lies the Ustyurt National Preserve. Far away from any habitation, going there requires a GPS and detailed satellite maps, as well as a careful calculation of how much fuel and water to take. Bring proper recovery gear because if your vehicle breaks down here, you are on your own since you may not have a cell phone connection for days. A digital detox, however, can’t get much grander than here, amidst a Martian panorama of solitary mountains rising from a massive salt depression and the Boszhira Tract. We set up camp below Boszhira’s towering limestone peaks among the extraordinary rock formations and pillars and discovered a sublime wonderland.

OUR LAND CRUISER, SLOWLY RUMBLING AWAY AT 1,500 RPM ACROSS THE SEEMINGLY ENDLESS DRIED ARAL SEA. BOTH TIME AND LANDSCAPE PASS BY AT A SLOW SPEED. WE ARE IN OUR ELEMENT, WITH NO TRAFFIC OR SETTLEMENTS IN SIGHT AND NO OBSTACLES ACROSS THE PATH.

WE FOLLOW TRACKS AROUND THE ARAL SEA, WITH SPORADIC VIEWS OF THE WATER’S LARGE BLACK SURFACE. A DRONE SHOT REVEALS THE MAGNIFICENCE OF THE DRIED, GRASSY ISLANDS WHICH SEEM TO BE FLOATING IN A VAST WHITE OCEAN.

SALTING AND DRYING MEAT IS COMMON PRACTICE TO ENSURE IT WILL LAST THROUGHOUT THE WINTER SEASON; THE TRADITION IS STRONGLY INFLUENCED BY THE NATION’S BYGONE NOMADIC WAY OF LIFE.

AS WE STROLLED ACROSS A CEMETERY JUST OUTSIDE BOZOY, WE WERE PUZZLED AS TO WHY ONLY CERTAIN TOMBS WERE COVERED IN A THIN LAYER OF ICE, GLISTENING BEWITCHINGLY IN THE SUN. DOES IT HAVE TO DO WITH THE TYPE OF STONE THEY WERE MADE OF? THERE WAS NOBODY TO ASK.

TESTIMONY OF THE DISASTER PLAYED OUT DURING SOVIET TIMES, WHEN THE RUSSIANS PURPOSELY DRAINED THE ARAL SEA TO FULFILL AN INCREASING NEED FOR WHEAT AND COTTON. HARBORS DRIED UP, AND SHIPS WERE LEFT TO RUST IN THE DESERT. MOST HAVE BEEN BOUGHT UP FOR THE VALUE OF THE METAL, WHILE THE HANDFUL THAT REMAINS TODAY SERVE AS A MEMORIAL.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF A DAM BETWEEN THE NORTH AND SOUTH ARAL SEA TURNED THE TIDE, THE NOW SLOWLY EXPANDING SEA GIVING HOPE TO FISHING VILLAGES SUCH AS KARASHALAN TO FLOURISH AGAIN.

(OPENING SPREAD):

THREE DAYS OF UNPAVED, FROZEN TRACKS LIE AHEAD OF US ACROSS THE DRIED-UP PART OF THE ARAL SEA. A SPRINKLE OF FRESH SNOW HAD US WORRIED AS THE STILL-VISIBLE TRACKS MIGHT HAVE DISAPPEARED UNDER HEAVIER SNOW.

MORE THAN 80 PERCENT OF THE CAMELS IN KAZAKHSTAN ARE THE DOUBLE-HUMPED CAMELUS BACTRIANUS. WITH THEIR FINE PHYSIQUE AND SHAGGY COATS, THE BACTRIAN CAMELS ARE FAMOUS FOR THEIR MEAT AND HAIR, WHILST MILK PRODUCTION IS HIGHER IN THE DROMEDARY OR SINGLE-HUMPED BREEDS.

KAYTAS ARE STYLIZED SHEEP TOMBSTONES CONSISTING OF A HORIZONTAL CYLINDER ON A PEDESTAL, MANY OF WHICH COME WITH THE CARVING OF A DAGGER. MANY HAVE BEEN LARGELY EATEN AWAY BY THE ELEMENTS, BUT THIS LITTLE POCKMARKED ONE STANDS WITH PRIDE AT THE SHAKPAK ATA NECROPOLIS.

BUILT INSIDE A LIMESTONE ROCK, THE 800- TO 1,100-YEAR-OLD UNDERGROUND MOSQUE OF SHAKPAK ATA HAS A FLOOR PLAN SHAPED LIKE A CROSS AND DRAWS LIGHT FROM HOLES IN

THE DOMED CEILINGS. SMALL NICHES IN THE WALLS CAN HOLD CANDLES FOR EXTRA LIGHTING.

WE ARE GRATEFUL THE ZILLIONS OF TRACKS ARE FILLED WITH ICE INSTEAD OF KNEE-DEEP MUD. IT IS ONE OF THE PERKS OF DRIVING THE DRIED-UP ARAL SEA DURING WINTER.

THE RENOVATED ENTRANCE TO SHAKPAK ATA’S UNDERGROUND MOSQUE ALLOWS EASIER ACCESS TO THE INCREASING NUMBER OF VISITORS. NOW ISOLATED FROM THE ELEMENTS, YOU CAN STILL SEE HOW WIND EROSION SCULPTED THE LIMESTONE WALLS INTO A HONEYCOMB STRUCTURE.

SCATTERED THROUGHOUT SHAKPAK, AS WELL AS IN OTHER CEMETERIES, ARE THESE LITTLE LIMESTONE OFFERING BOXES, WHICH FACILITATE

A PAYMENT SYSTEM FOR THE CARETAKER TO UPKEEP THE GRAVES AND RECITE SUTRAS FOR THE WELL-BEING OF THE DECEASED.

THE EARTH IS SCARRED BY A LABYRINTH OF ROUTES PLYING AMONG DRILLING STATIONS, OIL TESTING FIELDS, AND A RECENTLY BUILT GAS PIPELINE TO CHINA. AS WE DISCOVER ON A NON-FROZEN STRETCH, TRACKS EASILY BECOME QUAGMIRES, WHICH WE ASSUME IS THE REASON DRIVERS CREATE NEW TRACKS.

FROM ABOVE, THE ELABORATE AND TIGHTLY PACKED MAUSOLEA OF KOSHKAR ATA APPEARS TO RESEMBLE A TOWN WITH PROPER STREETS. IT IS UP CLOSE THAT YOU ARE CLUED IN, AS STREET SIGNS AND ELECTRIC WIRES ARE MISSING, AND THE HOUSES SEEM AWFULLY SMALL. THIS NECROPOLIS, WHICH ONCE BEGAN AS A SMALL CEMETERY FOR NOMADIC PEOPLE, NOW PRIMARILY HOSTS ETERNAL HOMES FOR URBAN KAZAKHSTANIS, INCLUDING HUGE, EXTRAVAGANT MAUSOLEA FOR THE WEALTHY.

AMIDST THE VASTNESS OF GRASSY PLAINS RISE THREE HUMUNGOUS MONUMENTS, MAUSOLEA OF FAMILY MEMBERS THAT LAY BURIED AT THE KENTY BABA NECROPOLIS. IMPRESSIVE AS THE LARGE STRUCTURES ARE, WE ARE PARTICULARLY ATTRACTED BY THE SMALLER DETAILS OF SOME OF THE TOMBSTONES’ CARVINGS, SUCH AS THIS FLOCK OF SHEEP.

EXITING THE SHAKPAKATASAY CANYON INVOLVES SEARCHING FOR THE PROPER (FAR FROM OBVIOUS) ROUTE. LUCKILY, THE LAND CRUISER LAUGHS AT THESE KINDS OF TRIALS.

AMIDST THOUSANDS OF OTHERS, WE COME ACROSS A MINI BALL NEXT TO ITS GRANDFATHER VERSION SOME 3 METERS HIGH IN THE VALLEY OF BALLS—TORYSH IN KAZAKH. AMONG THE THEORIES SURROUNDING THEIR CREATION IS THAT THE CURRENTS OF ANCIENT SEAS MAY HAVE FORMED THEM.

FUNERARY STONES ARE USUALLY ADORNED WITH CARVINGS THAT GIVE INSIGHT INTO THE LIVES OF THE DECEASED. WEAPONS ARE FREQUENTLY USED FOR MEN AND COMBS OR KETTLES FOR WOMEN. OTHER CARVINGS ARE LESS EXPLICIT IN THEIR SYMBOL OR REMAIN A MYSTERY TO US, LIKE THIS ONE.

A SWORD AND AX INDICATE THE GRAVE OF A WARRIOR AND ARE AMONG THE MOST COMMON CARVINGS ON MALE FUNERARY STONES, SUCH AS ON THIS KULPYTA, A CARVED STONE COLUMN.

THE FREQUENT SLIDING OF THE CARPET MAKES THE ENTRANCE TO SULTAN EPE’S UNDERGROUND MOSQUE A HAZARDOUS ONE. THE SUBTERRANEAN COMPLEX CONSISTS OF SEVERAL ROOMS SUPPORTED BY PILLARS AND DATES FROM BETWEEN THE 9TH AND 12TH CENTURIES.

THE SUNSET CASTS LONG SHADOWS ACROSS THE VALLEY OF BALLS, WHERE A MULTITUDE OF THREE- TO FOUR-METERHIGH ROCK FORMATIONS FILL THE VALLEY, AS IF THE GIANTS JUST LEFT THEIR GAME OF MARBLES FOR US TO FINISH.

EONS OF EROSION HAVE TURNED THE REMOTE MANGYSTAU REGION INTO A SURREAL DESERT LANDSCAPE WHERE SUPERLATIVES RUN SHORT OF THE MAGNIFICENT SCENERY. IN THE USTYURT NATURE RESERVE, WE JOURNEY AMONG WHITE LIMESTONE ESCARPMENTS, ISOLATED BLUFFS, TAKE IN THE THREE BROTHERS ISLANDS RISING FROM A BRACKISH LAKE, AND SET UP CAMP UNDER THE TOWERING BOSZHIRA ROCK FORMATION.

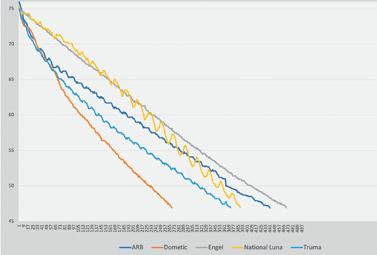

Testing the latest fridge-freezers to their limits.

By Scott Brady

Clockwise from top: We gathered power data via an inline PowerWerx meter and a Bluetooth-enabled Fluke clamp meter. The Fluke generated both graphical and CSV data logs. Heat output is an important consideration for both mounting and venting when the fridge is installed in the vehicle. Dual temperature data loggers were used to ensure accuracy and redundancy during the tests. These units are accurate enough for medical use and are certified for that purpose. Opening page: There are few accessories so universally loved as the 12-volt fridge/freezer, usually occupying a place of convenience and admiration in the vehicle.

Having interviewed hundreds of overlanders, we often ask what their favorite piece of kit is, and almost sheepishly, many reply “my fridge.” The reasons vary, like making ice for margaritas, keeping ice cream frozen for the kids, or preserving that fillet of wild Atlantic salmon for a BBQ in the Maze District. Regardless of why, the 12-volt fridge is a much-loved accessory for the vehicle-based traveler.

Each overlander is different, some eschewing nearly all comforts, crossing continents on a motorcycle with the most minimal of equipment, and there are four-wheeled counterparts that bring everything, including the Nespresso coffee maker. Both have their merits, but few luxuries match the fridge for pure homeyness, improving culinary outcomes paired with a breathtaking view. I have found that a fridge stocked with food and drinks makes the campsite feel like a home away from home, allowing me to cook healthy, plentiful portions for my travel companions, and prepare the proper sundowner for the end of a dusty day.

While fridges have become more technology-heavy in recent years, Bluetooth, remotes, and USB ports have little benefit for their intended use, and should be considered a secondary influence on the decision set. Primary attributes are matching the size in liters to the number of travelers (or the days remote), and pairing the insulation and compressor efficiency to the available battery/solar capacity.

Selecting the correct-sized fridge is the most important decision, as travelers often purchase too large of a model that unnecessarily robs the vehicle of interior volume. A solo traveler can easily use a 25- to 35-liter unit, and a couple with children can manage with only a 50-liter. The trick is to avoid refrigerating items that do not need cooling (like eggs, most cheese, and a surprising number of fruits and vegetables), and to only cool drinks needed for the day. A smaller fridge takes up less space, costs less to purchase, and typically uses less amps to run. Fridges larger than 60 liters are challenging to integrate in most vehicle layouts, and are best reserved for large 4WDs, trailers, or campers. As this test focuses on newer models to market, we do evaluate a wide range of sizes.

Primary attributes when selecting a fridge are matching the size in liters to the number of travelers (or the days remote), and pairing the insulation and compressor efficiency to the available battery/ solar capacity. PLEASE

Another important decision point is the efficiency of the motor and the insulation. While tests like these will often praise higher performance units, those successes come at a cost in both purchase price and overall volume efficiency. If the traveler tends to move each day, then efficiency is far less important. High insulative values require thicker, more expensive injected foam, which requires more labor to assemble, and the walls of the fridge will be thicker. Which in turn

either makes the unit larger for the same interior volume, or costs interior volume for the same exterior dimensions. We suggest not buying performance you don’t need.

Through our travels, we have found a few things worth investing in, including a cabinet temperature gauge, a lowvoltage cutoff, and a freezer unit. The temp readout puts the user at ease, and helps prevent spoilage or frozen radicchio; fortunately, all of the units in this test have some form of gauge. A low-voltage shutoff preserves starting power in the battery and also helps prevent battery damage. The right lowvoltage cutoff can even reduce the need for a dual battery in some configurations. However, there are units like the Engel that will run all the way down to 9 volts, which can permanently damage expensive house batteries. It is best to find a fridge with an adjustable cutoff, which lets the user adjust the shutoff point to the system configuration. For example, I run a much higher shutoff voltage when the fridge is running on the starting battery. Lastly, we prefer a unit that includes a freezer compartment, for the simple reason that a freezer makes ice, which will support additional food in a cooler, or cool warm drinks that do not need to take up space in the fridge. Meat can keep for months in the freezer, and there is just something special about unwrapping an ice cream treat in the Gobi Desert.

Our evaluation relied on good system design, repeatability, environmental controls, and vigilant oversight. The objective data was collected by our Operations Manager Garrett Mead, who coordinated with me on the testing methods and controls. Each test started with a digital scale weight before moving on to determining start-up amperage, cooldown amp hours and effectiveness (time to 46°F), steady-state amp hours (maintaining 46°F), and time to warm up (to 56°F).

To measure start-up and running amps (which allows for amp hour calculations), we captured the current with a Fluke data logger paired to Garrett’s iPhone. This permits exporting the data as a comma-separated values file (CSV). The data was validated with interval readings from our PowerWerx inline power analyzer. For temperature measurements, we purchased two identical certified data loggers with +/- .6°F accuracy. Both loggers ran during each test to ensure accuracy and to identify possible logging errors. These data loggers export to CSV for analysis and charting. Interestingly, obtaining these units proved quite challenging during Covid as they are used for vaccine storage monitoring. For a fluid thermal load of 423 ounces, we used 38 cans of S.Pellegrino flavored water, arranged without touching the interior sides, placing the temperature sensor probes deep within the center of the load (but not touching the cans) to ensure that the thermal mass achieved our benchmark temp of 46°F.

Additional tests included a decibel measurement of the compressor during peak cooling to determine fan, vibration,

and other sounds that contribute to a noisy sleeping environment. We also took four cooling vent temp checks with a thermal IR gauge to determine how hot the units ran (to help the buyer consider required cooling spacing and airflow), and we captured Forward Looking InfraRed (FLIR) thermal images of the fridges to look for concentrated heat zones and potential cooling loss areas (for example, around the lid).

Subjective tests included lifting, moving, mounting, loading, and lashing the units, and using them in the field. Considerable insight only comes with adequate use, so all of these fridges have been used on long trips to expose design benefits or flaws. These subjective observations are reflected in the individual reviews and contribute to the final rankings.

from

has designed the most intuitive and comprehensive app in the test. The ARB fridge app is easy to use and accurate. The Truma app is functional yet lacks some of the interface design and logic of the other solutions. Using a FLIR camera provides critical insight into the data the loggers capture, like the poor sealing of the ARB lid. This undoubtedly contributed to its reduced performance. The Engel has a massive venting area which helps it to work effectively in more confined spaces. Good airflow also helps improve efficiency.

ARB has become legendary in the overland market, providing quality components for a wide range of vehicles and a laundry list of accessories. This brings several benefits to a product like fridges, including a global distribution network and economies of scale, driving down costs while improving service and support. When it comes to 12-volt coolers, ARB has regularly outsourced their production, starting with rebranded Engels, then in-housedesigned units produced by Dometic. More recently, they have sourced the Zero line from Asia, with an emphasis on the durability of the packaging (i.e., impacts and vibration) and their on-unit and app interfaces.

PROS

Serious volume for large parties

Durable construction 12-volt inputs on both fridge sides

CONS

Less space-efficient than others in the test

Heavy

Below-average performance

The Zero’s size is further enhanced by the thickness of the insulation and plastic case, mass of the handles, and sturdy corner guards. It all feels robust in a genuine way, and at nearly 70 pounds, could almost use two people to carry it. All of this mass and volume results in it being the fridge for large families or larger vehicles. It is roughly twice the size of the Engel in overall dimensions, which results in a huge freezer zone and a fridge-side that swallows whole gallons of milk. It is also possible to remove the freezer divider and improve space efficiency even more. Another advantageous feature is the basin drain, which makes cleanup so much easier. This model has the best lashing solution of the test, with stamped stainless steel clip-in brackets and four heavy-duty integrated tie-downs to keep it in place. The phone app is useful and lets you keep tabs on the contents from your beach chair. A few other items I like are the reversing lid and the brilliant idea of putting the 12-volt input on both sides of the case. Accessories are numerous, including mounting kits, wiring kits, covers, and slides. In use, the weight and size of the ARB are immediately noticeable and will require the right application to fit properly. The performance of the fridge is below average, with faster cooling initially, followed by slower performance as the temperature closes in on the benchmark of 46°F. Interestingly, the resolution of the data logger showed a less than optimal cooling profile, with the controller idling the compressor for short periods despite it being set to maximize cooling. The warmup was also below average, with the ARB warming 10° faster than any other unit in the test (albeit similar to the Truma as expected). The volume of the fridge is a serious benefit; and the larger volume, when compared with others in the test, will have an impact on cooling and warming efficiencies.

$1,526 | ARBUSA.COM

DOMETIC | CFX3 55IM

55 LITERS, 47 POUNDS

multiple features.

Dometicis a powerhouse of the RV, marine, and overland markets, generating everything from stoves to mobile air conditioners. They have also been producing chest, drawer, and upright fridges for decades, and it shows in the level of refinement and features. We have watched the Dometic units evolve, and the current incarnation presents their most travelfriendly model yet, with rounded and reinforced corners, a waterproof LCD user interface packed with information, and one of the best Bluetooth apps in the test.

Best display (and location) in the test

Best overall performance

Lowest weight in the test

Lack of traditional freezer (which might be a pro for some)

Plastic case and lid will be less durable against scratches

The CFX looks like a fridge designed for the 2020s, with a modern soft-touch matte finish, sculpted corners, and smooth lid integration. The handles are all that protrude, and lack sharp edges to cut or mar vehicle surfaces. They are also the primary lashing point, and are more than up to the task. When picking up the fridge, it is clearly different, being the lightest in the test, despite average interior volume. This is primarily due to the extensive use of reinforced plastics, but that technology has proven to provide several benefits, including insulation. The downside is scratches and scuffs in the plastic, something the stainless units never show.

The Dometic provides the most useful app in the test, including amp hour usage by hour, day, or week. We noticed that the graph does not have enough upper limit range, with the unit using above the 5 amp hours shown on the app graph. Despite this, the daily graph is helpful for gauging power consumption. It is possible to change the set temperature in the fridge from the app and see the current temperature, both of which are convenient to the passenger while driving—no more spoiled or frozen food. The last feature of note is the lack of a true freezer, but the ability to make ice. For many travelers, the layout is perfect, providing more fridge space, as well as evening libations on the rocks.

For performance, the Dometic gave an impressive result, with the fastest cooling rate of the test. In fact, the effectiveness was so notable, that we tested the unit multiple times to validate the results. Power consumption was also modest at 4.6 amp hours under rapid cooling, owing to the design of their compressor and condenser/evaporator capacity. Dometic did not skimp on insulation either, having the second-slowest warm-up rate in the evaluation, keeping the drinks cooler for longer than all but the National Luna.

$1,099 | DOMETIC.COM

Top to bottom: The Engel is the most compact unit in the test, which will be a benefit for some. As the first Engel fridge-freezer combo, it uses a simple insulating design. While still very analog, this model is the most advanced of any Engel model. We see that as an advantage for many users.

The

first 12-volt fridge I encountered was owned by my neighbor, an old Engel that had served as his garage beer fridge for more decades than he knew. He had only turned it off once—when he moved just down the street from me. I acquired it and used that fridge for years before selling it to a friend. The fridge is still running in their garage, filled with drinks. There is one critical thing to know about an Engel, and that is the swing motor technology. The Sawafuji compressor has only one moving part, the piston, which slides back and forth inside the cylinder, self-lubricating as it runs. The other benefit of this technology is the industry’s lowest start-up amperage (by more than half in some cases), which allows the Engel to be plugged into OEM 12-volt sockets (which have small-diameter wire).

Upon initial review, the Engel’s modest appearance belies its strengths, with a stamped, powder-coated steel shell and molded plastic interior. The unit is notably compact for the volume, lacking anything non-essential (no bulky bumpers or bottle openers, etc.) The handles, from our experience, are only suitable for carrying the unit, not proper lashing. For that, there are robust brackets (sold separately) that affix to the factory captive inserts. This new-model Engel features significantly more detail on its display, including the temperature of the cabinet, the set temp, and the battery state. Another notable feature is an adjustable low-voltage disconnect, which is a first for the brand. The cooling function is simple and robust, with the fridge zone factory set to 0-5°C, and the freezer adjustable from -18°C to +10°C. The size of the fridge can be adjusted to three different volumes, including fridge only.

Lowest start-up amperage

Lowest amp hour draw in the test

Most space-efficient for volume

Coil configuration is less effective when used as a fridge

Handles not robust enough for rough terrain lashing

Average cooling and warming performance

The performance of the Engel is toward the middle of the pack but should not be considered slow. The data logger showed how steady and consistent the cooling rate was, complemented by the lowest power consumption in the test. On the warm-up, the Engel beat out the ARB and Truma for a mid-pack finish. The strength of the Engel is its reliability and efficiency, including the low start-up amperage and average running draw. Engel addressed many of the upgrade desires we have expressed through the years, including more precise temperature control and an adjustable low-voltage disconnect. The release of a combination fridge-freezer is a win for Engel lovers, although the cooling plate/coil configuration undoubtedly impacted the cooldown times for the thermal load we selected.

$1,099 | ENGELCOOLERS.COM

50 LITERS, 55 POUNDS

Top to bottom: The National Luna is arguably the most classic and attractive of all available fridges, with a dimpled stainless steel case and quality materials throughout. The layout is a traditional combi layout, with a large fridge and smaller freezer with a lid. To ensure a good seal, the Legacy uses two lid latches.

The

South Africans have been overlanding for a long time and en masse, which resulted in some of the earliest and most notable market innovations for the vehicle-based traveler. This includes the ZA manufactured National Luna fridges, which have been made in Africa for over 30 years, and won the previous two Overland Journal fridge-freezer tests. They have a wide range of options to suit the needs of the traveler, including models with over 70-millimeter-thick walls filled with premium injected insulation. More recently, they introduced a new Legacy line of fridges that found the optimal confluence of performance, material quality, and value.

High quality and attractive materials throughout Lid can be mounted in multiple directions

Precise, independent compartment controls Class-leading insulation performance

CONS

Slower to cool than previous models

Two latches to access chest

The Legacy line incorporates a proprietary “off-road” compressor (still similar to the Danfoss-style) and several improvements in useability, like a fully selectable temperature range for both compartments. This is clever, as the buyer may choose to have a large freezer, and a small fridge, or vice versa. The display is easy to read but can be bright in a sleeping area. The control panel allows easy adjustment to the threeposition low voltage cutoff and activation of the turbo mode. It is important to note that this fridge in turbo mode will pull significant power (upward of 7.2 amps), so wiring should be sized accordingly. The fridge is genuinely handsome and classically styled with a dimpled 430-grade stainless steel shell and three-way configurable lid. The handles are robust and fold tight against the body and thoughtfully include a channel to run a strap for lashing. The interior is assembled from aluminum panels and is cooled with copper piping (all contributing to fewer cold or hot spots, an attribute we validated with the FLIR).

The performance of the Legacy compressor is notably different from National Luna units in the past. Despite bottoming the set temperature and selecting turbo mode, the cooling profile would not keep the system at a steady rate. This may be to maximize efficiency (this unit did have one of the lowest amp-hour draws) or to protect the compressor, but it did slow the rapid cooling rate when compared with their past units. Warm-up, however, was right in alignment with the past products, keeping food colder than any of the other models in the test. The thermal load took over 18 hours to warm up 10° in our test environment of a controlled 78°F. The Legacy benefits significantly from the precise and independent control of the two storage chambers. The National Luna switching system actively cools the larger or smaller compartment depending on the user’s needs, which can even change during a trip, like starting with a larger freezer and then shifting to a larger fridge as the trip progresses.

$1,295 | NATIONALLUNA.COM, EQUIPT1.COM

Truma appears to be new to the market, but they are one of the oldest companies in the test. The business was started in 1949 as part of the Marshall Plan for German economic development after World War II. As a way of honoring US President Harry S. Truman, the founder, Philipp Kreis, called it Truma. The company’s first product was a gas lamp, followed by 70+ years of camping and RV equipment for the European market. In 2013, Truma opened its North American operations, providing hot water heaters, air heaters, combi-units, and more recently, portable refrigerators like the 69-liter unit in this test.

The lineup of Truma fridges is impressive, offering everything from 36 liters to 105 liters. Their adventure line of dual-zone units includes 69- and 96-liter models, so we selected the unit closest to the test size range. Initial inspection reveals robust construction with reinforced rubber corners and handles that fold flat against the sides. Connecting the 12-volt power supply is available on both sides of the fridge, which is a clever solution shared with the ARB. The lid can also be reversed to allow for more placement options. The on-unit display allows for the adjustment of compartment temperatures, along with a turbo mode for rapid cooling. The display shows the current temp or set temp for the individual compartments. Using the smartphone app allows for additional adjustments, including battery voltage at the unit and adjusting the low-voltage cutoff settings.

Robust, reinforced plastic 12-volt inputs on both ends

Dual control over the 69-liter volume

Lower space-efficiency with bulky walls and rubber corners

The Truma fridge is a solid performer, providing the secondfastest cooling time of the test. It just bests the National Luna Legacy, with a similar cooling cycle to the ARB, featuring short waves of slightly faster and then slightly slower cooling intervals. The cooling rate was generally consistent, which speaks to the compressor performance and the support of the fan and overall coil and condenser surface area. The freezer configuration uses a lid and insulation barrier, combined with increased coil density on the freezer side of the chest. Its modular solution allows for less control of the freezer compartment temperature, but it also allows the entire unit to be used solely as a fridge.

Average insulation performance, despite wall thickness

Heavy

For the warm-up, the Truma demonstrates a lower insulation effectiveness than all other units, with the exception of the ARB (which performed similarly). It is difficult to assess the type of insulation used without destroying the test unit, but it warmed the contents almost 40 percent faster than the supremely well-insulated National Luna. The Truma benefits from a robust, stylish case and a feature-rich display and app control. This unit is a great choice for travelers with more vehicle space and the desire for a larger fridge volume.

$1,549 | TRUMA.NET

This is Overland Journal’s third comprehensive fridge test, the first completed nearly 13 years ago. In the previous two tests, the National Luna was the standout performer, showcasing the company’s near solitary focus on vehicle-based fridge-freezers. A lot has changed in the subsequent decade, with fridges becoming extremely popular, even in the general consumer space, allowing for significant investment in technology, design, and manufacturing. All of the fridges are improved, and the gap closed around our reigning champ. There are now solutions for every buyer.

For the Value Award, it comes down to the Engel Combi and the Dometic CFX3. They are both priced at $1,099, and are outstanding performers in their own right. Beyond that, each unit is quite different in the benefits they provide.

The Engel is the most space efficient (exterior versus interior volume) and the most power efficient in the test. I especially like the classic and simplified metal case and easy-to-remove lid. Having used Engels for over two decades, their reliability cannot be understated. The Dometic packs class-leading overall performance, along with light weight and the best display of the test. It is worth noting that the National Luna is a great value too, with premium materials and class-leading insulation, albeit at a higher price. Objectively, they are all exceptional values, but the Engel epitomizes the spirit of value and minimalism, requiring less power (start-up and running amps), less space, and a modest purchase price. It also benefits from one of the most important value predictors of all—reliability.

For this test, the Editor’s Choice was a surprise, the result only possible because of the resolution, diversity, and controls of the testing process. We have found it important to have repeatability in the testing model, at least as much as possible within reasonable constraints. This effort demonstrated how good fridges have become, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of each model. While all of the subjective and objective criteria are important, there are a few

criteria that matter on nearly every day of an overland journey, like unit weight (which impacts payload), cooling efficiency, insulation, and average amperage draw. There are also more subjective considerations, like ease of use, interior layout, and straightforward cleaning. All of these elements culminated with the Dometic and National Luna vying for our Editor’s Choice.

In past tests, the National Luna has dominated both cooldown and warm-up results, a combination of both insulation and coil construction/density. For the first time, a National Luna model was bested in cooldown performance, the Dometic cooling rapidly and smoothly down to our benchmark 46°F. The Dometic cooled down nearly twice as fast as the slowest unit in the test, and did so with an average of 4.6 amp hours. On the insulation test, the National Luna was better, resulting in the best-in-class warm-up performance. However, the Dometic was the second-best warm-up result. From here, the Dometic won out on usability, having an excellent app, the lightest weight in the test, a high-mounted display (which I prefer), and efficient power usage. While I have also personally used National Luna fridges for almost two decades, I have selected the Dometic CFX as my Editor’s Choice because of its near optimal execution of the functions most needed in a 12-volt fridge-freezer.

DISCLOSURES Even our best attempts to control variables and ensure repeatability of our tests results in a degree of falsifiability. Disclosures surround the function of how fridges determine their case temperatures, and any competitive advantage around compartment design.

As a control, we set each fridge to their lowest possible set point, and then monitor the temperature of the thermal load by the display on the data logger. The load cools much more slowly than the walls of the fridge, and thereby the fridge’s temperature probe. While most fridge controllers compensate for this effect, it is possible for unusual cooling profiles to present themselves as the fridge is tricked by its own probe data. This could be represented in the National Luna cooling profile, as the unit attempts to gauge the rate it is actually cooling the fluid load in the cabinet. Cooling over 400 ounces of liquid from room temperature to 46°F is a particularly challenging expectation of a fridge.

Each of these fridges have a freezer capability, but the Dometic only freezes ice in two small trays. As a result, the Dometic has some design advantages toward rapid cooling of a single compartment. We tested the Dometic by also including room temperature ice trays, effectively increasing the total fluid it needed to freeze. Despite this, it still performed faster than others in the test, and the slower of the test results are reflected in the chart. The opposite is true for the Engel, which uses a unique coil plate design, which allows for a combination fridge-freezer. This design is less efficient at cooling fluids quickly, but was still tested in accordance with the unit’s published use case as a fridge or a freezer.

We intentionally selected newer models that incorporate a freezer function and brands that are known for reliability.

The cooldown chart shows how quickly the fridge cooled the load from 75°F to 46°F. Warmup performance is a greater indicator of long-term effectiveness than any other attribute.

A secret world, turning back the clock to a better time.

By Graeme Bell

Wehad been warned by European friends and the US government travel advisory not to travel to Turkey. The government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was said to be sliding towards totalitarianism while struggling with terrorism and the war in Syria. The relationship between NATO allies Germany, the United States, and Turkey was particularly strained for many well-documented reasons. Though we are not German or American, we are large and blonde and may be mistaken for either nationality. A month earlier in 2018, while waiting out winter on a friend’s island in Greece, we decided that we would travel to the country but be careful of our statements on social media while there and cautious of our activities, particularly near military installations. We had to make the same decision when we entered tumultuous Venezuela four years earlier, determined to overland through northern South America and complete our circumnavigation of that continent. Our goal in Turkey was to explore a country that many international travelers consider one of, if not the best, overland destinations on the planet.

In late February 2018, our family of four entered northern European Turkey from freezing Greece and made our way rapidly south, seeking sunshine and blue skies. An ice-cold wind blew us to Gallipoli, where Churchill’s 1915 strategy to sacrifice the aging, redundant British naval fleet for control of the Dardanelles—thereby securing the Suez Canal and year-round warm water supply routes to Russia—was ignored by nostalgic

admirals who had dithered for weeks before the attack. The element of surprise was lost, allowing the waning Ottoman Empire precious time to fortify, resulting in the slaughter of thousands of brave Australian and New Zealand soldiers (and an equal number of Turks, 250,000). We crossed the Dardanelles on an old ferry, one of many that weaved confidently through crowded shipping lanes of oil tankers and colossal, surging container ships, and rolled the Defender onto Asian soil. It was our fifth continent overland.

The ancient city of Troy, site of the Trojan Wars, guarded access to Mount Ida (Goose Mountain) which stood tall, fighting to hold back the European winter, the sun shining warmly on her southern slopes. We travelled as far as the coastal town of Burhaniye, where the beleaguered Defender decided it was time to refuse further passage. The motor had developed a debilitating misfire since Greece, and it took a few weeks of speculative daily mechanical inspection, fault finding, and repair before we eventually opened the engine (in camp) and replaced the injector seals and washers. It was a delicate task which solved our mechanical problems despite a large, obnoxious dove divepooping in cylinder three. During this period of forced immobility, we learned a few important Turkish words and phrases and immersed ourselves, at least partially, in the community. Serendipitously, we had asked Turkish immigration for the maximum three-month visas; the cost was 100 euros for the four of us. With two months left to explore the large nation, we headed south past Izmir, the wealthy Mediterranean city. Using the app Wikiloc, we found a little peninsula that was almost an island where we could free camp near an isolated rocky beach. We cleaned the beach of plastic litter and lost shoes (probably, but hopefully not, the lost apparel of Syrian refugees who braved the sea to reach Greece and Europe). Local fishing boats bobbed nearby, a sheepdog left his shepherd to become our new friend, and a military helicopter conducted rescue drills, training navy swimmers. Nearly every island surrounding Turkey belongs to Greece, thanks to a long history of dispute and the involvement of the Western powers, and refugees need only reach one of those islands to be granted asylum in Europe.

Turkish hospitality is legendary, as we would soon experience. Upon leaving the island, the Defender again developed an infuriating misfire. While working on the electrical system outside a roadside restaurant, we met Khan, a young entrepreneur who diagnosed a bent pin on the crank position sensor and invited us to his home. We enjoyed a meal of olives, pastries, cheese, and tea before being offered a night’s accommodation, a shower, and 90 large brown eggs. Accepting 30 eggs and a family photo, we left our new friends, drove 200 kilometers, and camped next to a park that serviced a beach with a view of a military base and an oil refinery. Later a head-scarfed woman approached the Land Rover and offered us a still-steaming, freshly baked cake and a bottle of cold Coca-Cola. When my girls returned the washed cake dish to her, they were invited to indulge in two hours of pastries and conversation before the woman offered us all a bed for the night in her large modern home. Her daughter was a famous television and social media

personality who offered to fly home from Istanbul to show us around the area and teach us about Turkey. Not since the USA had we experienced such hospitality.

Pamukkale is a town in western Turkey known for mineralrich thermal waters flowing in perfect blue, rolling over sparkling travertine terraces. Pamukkale neighbors Hierapolis, an ancient Roman spa city founded around 190 BC. Ruins there include a well-preserved theater and a necropolis with sarcophagi. The Antique Pool is famous for its submerged Roman columns, the result of an earthquake. We needed a place to camp for the night and were surprised to find ourselves driving up a little-travelled

We had driven up into a secret world far from the beaten track, far from tourism, back in time to a better time.

4WD track to an area overlooking the terraces, ruins, town, and the River Menderes, the ideal location for a hotel. The muezzin called the azan at sunset, and lights flickered across the valley. Below, buses bustled, and visitors ate cold plates of hot food while we made a barbecue and quietly witnessed the various transactions below. A large dog joined us and enjoyed a meal of bones and rice; he lay at the door of the camper and protected us until dawn before being called away to another purpose. Of the million annual visitors to Pamukkale, I am positive that very few had the opportunity to enjoy the World Heritage Site quite as we did, and I would not have it any other way. As we would later discover in Cappadocia, the Turks allow freedom of movement, and few fences prohibit exploration.

In Turkey, unique experiences are common, which is uncommon indeed. After a brief stay in Fethiye, a tourist hotspot favoured by the British, we continued south, where we found a place to camp next to a small white beach and crystal clear sea near Kaş. We felt perfectly safe. Chinese sightseers stopped to have their photo taken with us, and a Turkish wedding party pulled over to dance, the bride dressed in an explosion of white silk and lace. We swam in the sea and relaxed completely; a fishing boat took advantage of the small bay to anchor and wash the deck as the sun set over the islands of Greece, a short boat ride away.

Only a few days later after Luisa filmed a hipster barber abusing me with hot wax and a cool attitude (the resulting video has had over 100 million views), we found ourselves having breakfast in the Taurus Mountains that separate the Mediterranean coast from the Anatolian Plateau. Luisa, our navigator, had plotted a route through the Taurus Mountains to Cappadocia, and we were amazed that there was an endless supply of trails which we were free to travel, and that we could camp almost anywhere. Driving through rural villages, the population would stop and stare as we passed. It seemed that this paradise was not explored by many of our kind, the kind of people who would rather be free in the mountains than standing in a ruin queue. We felt like we were back in Peru. Although the Taurus Mountains are not nearly as impressive as the Andes, the peaks and valleys and blue rivers have an indelible charm. We had driven up into a secret world far from the beaten track, far from tourism, back in time to a better time.

With dusk approaching, we exited the mountain range and emerged onto the Anatolian Plateau after a week of exploring— tired, thrilled, and dusty. Luisa pointed to rolling hills in the shadow of the 3,916-metertall Mount Erciyes, “There is a national park there, apparently. Maybe we can find a place to camp.” She guided us into the hills, but instead of finding a national park, we found only a small rural village and a network of dusty trails looping up and around the hills. We drove on, following our instincts until we found a perfect, level site to camp—the snowcapped mountain before us and a valley spread below. Wherever we looked, we saw only beauty. The sun set too soon, and we ate a meal, chatting about our experiences and our plans for Cappadocia.

A full moon rose from behind the mountain, and a flashlight swayed across the hills that flanked us. A voice called out, “HA, HAA.” The voice grew closer until I decided to step out and meet the man with the flashlight and booming voice. A dog, the size of a lion, surprised me as I walked towards the walking light. I approached the man who shone the light in my eyes, blinding me until I greeted him, “As-salamu Alaikum.” Immediately the light dropped to shine a circle on the ground. “Wa-Alaikum-Salaam.” We shook hands as the shepherd smiled at me inquisitively, “Where are you from? Africa?”

After a short chat, the shepherd moved on, but the large dog remained, settling down in front of the Land Rover, keeping an eye on both us and the herd of scraggly sheep which were the same colour as the Kangal dog (or it might have been an Anatolian shepherd, I can’t tell the difference). The Kangal is a fascinating breed that serves as excellent flock guardians, known to care for their charges for up to a year without human contact, never eating from the flock but surviving on rodents and ground squirrels. Throughout the night, the Kangal protected us as well, occasionally barking if he spotted something in his territory. There were two more Kangals in the pack, and between them, they surrounded and secured the flock. Safe from harm, we slept as if in a fortress and woke to a clear blue sky.

Cappadocia is unlike any other natural tourist site we have encountered in our seven