3 minute read

Ques T ions

that brings young children into community gardens with their kids. It happens with Keys 4 Healthy Kids in WV where child obesity clinics work with both children and caregivers, and where the organization provides education, toolkits, and follow-up to community organizations. These are hyperlocal and very nuanced efforts.

2. Kids neglected and abused in their family of origin, or by relatives, or by formal systems of foster care. We heard about this everywhere, particularly in the context of the child abuse and neglect that follows from parental drug addictions. The stories we heard in West Virginia were most pervasive and poignant. Simply put, the number of kids who need different care is staggering.

Programs like Handle with Care, mentioned later in this report, help to reduce the inadvertent deepening of trauma when kids arrive at school unafraid and unprepared after a hard night at home. Quite honestly, mostly what we encountered was people shaking their heads and saying they just didn’t know what to do.

3. Children for whom their formal childcare system is main source of continuity and health. In West Virginia we had the opportunity to meet with a coalition of formal childcare providers that is convened and supported by the Universitybased County Extension Service. They’ve been meeting for several years and have had a chance to build trust and learn how to listen to each other. They told us, for example, about the many challenges they had met and overcome as they followed guidelines from Keys 4 Healthy Kids to improve childhood nutrition. They showed what happens when there’s an alchemy of external knowledge -- the guidelines -- and a committed community of people who will figure out how to make it work. They know they have to figure out how to work more with the families of their children. They know, for example, that if they can help a family have three dinners together a week, there’s a 65% less likelihood of drug abuse. The only way they can provide this support is through daily, informal conversation with parents. They also know they are the one source of consistence in the lives of many children -- 70% of their kids are from at-risk families with no transport and living in food deserts.

From our perspective what’s necessary is listening and convening and trusting that good and caring people will make good choices. Knowledge and ideas can be provided to help, but the people who have the direct contact with children are the ones who have to figure out how to use their resources to make a difference.

HCHW T H eme Learning

Ques T ions

Given the growing funding and subsequent action in the PreK movement (age 3-5) and the significantly less funding and action in the P(pregnancy) to 2 space, and the importance of quality across systems, how should this factor into our focus area(s)? From a systems perspective, where are our resources best allocated to have greatest impact?

In general we heard stories about how important prenatal nutrition is and the importance of support for teenage moms. In one West Virginia community we heard, on the one hand, the story of one high school that simply turned a blind eye to the significant levels of teen pregnancy among its students. No, we’re not going to make contraception available or increase sex education, or provide support for young moms. That contrasts with a story about Chandler High School in WV or the Teenage Parent Program (TAPP) in Kentucky, where the school made a commitment to pregnant moms and brought them further into community -- achieving both an unheard of 97% graduation rate and a high rate of college placement.

People in the Indian Health Center in Tulsa talked about how they needed to support mothers in being healthy as the first step in preventing childhood obesity -- without blaming or shaming them. In New Mexico people talked about how essential it was to help young moms who didn’t know anything about good nutrition from their family of origin learn how to take good care of themselves and their babies.

“One of the moms I work with drank 10 -12 liters of soda per day and her kid wouldn’t stop crying. Instead of dropping soda, she stopped breastfeeding.” (Community Worker, Lincoln, West Virginia)

You’ll find that we keep coming back to the same principles and values in this report. Convening the people who care. Helping them talk and learn with each other. Nourishing them with good ideas from outside their immediate experience. Sharing their own stories widely for inspiration as well as information.

Child Health

What are the bright spots where children’s health and health care systems are connected to and integrated with services and supports that families need to improve child health and reduce disparities?

These bright lights are everywhere and you will find them highlighted throughout this report. Years ago in a U.S. Presidential Campaign one of the slogans that developed prominence was “It’s about the economy, stupid.” On this listening tour, what people said time and time again in many ways was “it’s about the children, stupid.”

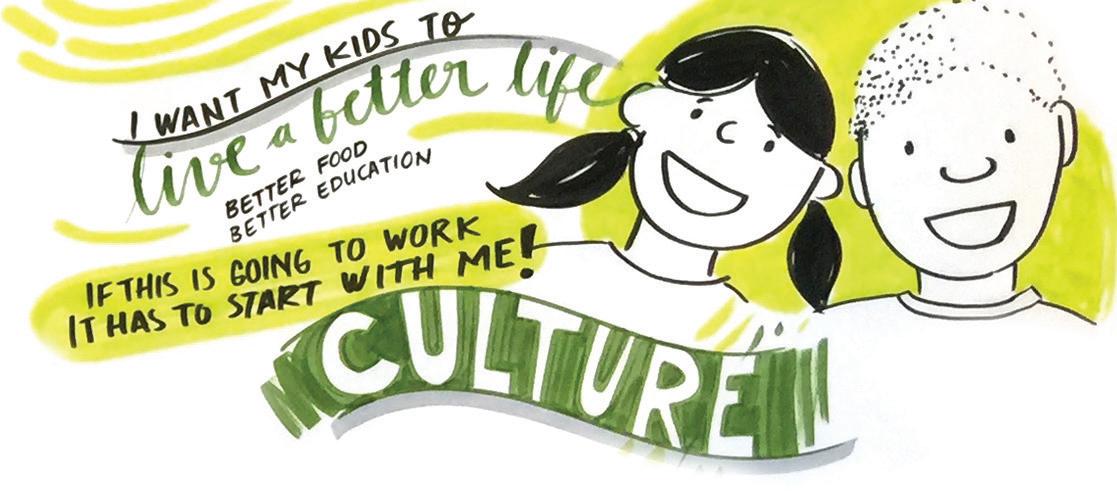

Growing food, preparing food, exercising, having spaces to exercise, seeing others making wise choices, finding hope, getting role models, respecting each other, trusting human goodness and compassion. The people we encounter are not new age idealists. Some were, but most were not loud and passionate social activists. They were solid folk who stepped forward because they saw an opportunity and a need and they knew they could make a difference.

They are changing the landscape of community by creating a culture of health.