23 minute read

Taking Action

Aswe explored in this landscape of a culture of health, one of the key questions that guided our listening was what are families already doing to improve their health? What was clear from the very first calls we made to begin organizing this listening is that the level of public understanding and awareness of health issues and what needs to be done to get healthy is substantial. People stepping forward in their families and in their communities see the relationships between diabetes, nutrition, weight and exercise, they know about stress, anxiety, and other social determinants of health. They understand that drug abuse, joblessness, and incarceration are all part of a seemingly never ending downward spiral of poor health.

So what are they doing? In every region we visited people are stepping forward because they see something they can do that will make a difference. We’ve written about this in the section on how change happens as well. What emerges from these individual efforts is a mosaic of practices which have the potential, if amplified, to create a culture of health.

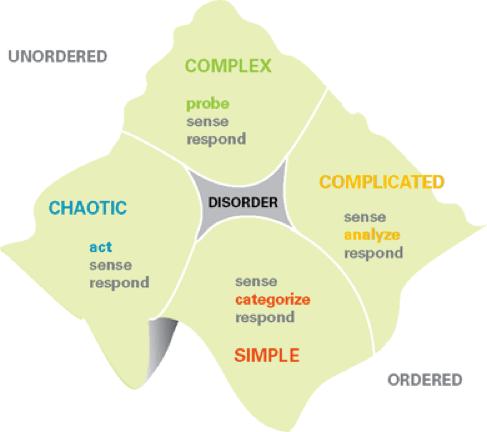

Throughout the tour people shared their stories about what they were doing to help members of their families and communities be healthy. We’ve mentioned some of these in the preceding section describing the landscape and we will risk being repetitive and include them here with more detail as well. We’ve used the four kinds of practices named in David Snowden’s Cynefin Framework to categorize what we heard: n Obvious (replacing the previously used terminology Simple from early 2014), in which the relationship between cause and effect is obvious to all, the approach is to SenseCategorize - Respond. Here we apply best practice. n Complicated, in which the relationship between cause and effect requires analysis or some other form of investigation and/or the application of expert knowledge, the approach is to Sense - Analyze - Respond. Here we apply good practice. n Complex, in which the relationship between cause and effect can only be perceived in retrospect, but not in advance, the approach is to Probe - Sense - Respond. Here we sense emergent practice. n Chaotic, in which there is no relationship between cause and effect at systems level, the approach is to Act - SenseRespond. Here we discover novel practice.

The Cynefin framework has five domains.

The fifth domain is Disorder, which is the state of not knowing what type of causality exists. In this state people will revert to their own comfort zone in making a decision. In full use, the Cynefin framework has sub-domains, and the boundary between obvious and chaotic is seen as a catastrophic one: complacency leads to failure.

We’ve seen many examples of all four of these kinds of practices and have tried to select some based on our understanding: n Best Practices are the things that can actually replicated elsewhere. The kinks are worked out, a lot has been understood. They will still vary from place to place -- but the core ideas are sound and they make a difference. They work. Let’s spread them. n Good Practices are things that have been around the block several times. Edges are still rough, but something powerful is starting to become visible. These practices can be improved in their current contexts and they are far enough along that others may find valuable starting points in their contexts. n Novel Practices are the new ideas which are being tried, tested and developed. They appear to have potential and are clearly worth watching and supporting. How they will evolve and what impact they will have is still unclear. n Emergent Practices are actions being taken in response to very specific situations. They’re working and can be improved. They are generally not something which can implemented elsewhere -- they are very context-specific -but they are important to notice.

Best Practices

The term Best Practices comes from the never-ending search for how to make things replicable and scaleable. Even if a best practice, most things grow in the unique conditions of particular communities or systems. Directly transplanting them elsewhere, without the flexibility to take on the local context, leads to very uneven results. Best practices we encountered are: n Spaces of Care - Gardens, Centers, Clinics n Handle with Care n Health Impact Assessments n School Based Health Centers n Keys 4 Healthy Kids n Healthy Nutrition in Institutionalized Settings n Bicycle Hubs n Local Partnerships

Spaces That Grow Community

In the Landscape of Health, on page XX we detailed some of what we heard about three kinds of spaces -- community gardens, centers of community and clinics in community. We wanted to bring them forward as part of the landscape because they are so important. And we need to emphasize here that they are, in fact, best practices. These three spaces are essential in communities where healing is taking place. They are literally the ground for that healing.

The mechanics and the particulars are different in community. But what we noticed across the country is that where people are taking health seriously, they are in fact an essential and best practice.

Handle With Care

There’s a lot going on for families all over this country. Lots of stress and dysfunction which lead to traumatized children. This is a particularly prevalent story in West Virginia where the rate of removal of children from birth families for either foster or institutional care is one of the highest in the nation.

Kids arrive at school after a night of horror at home -violence, drug abuse, visits from the police. Likely little or no food. Homework certainly not done. A sleepless scary night. Teachers and administrators don’t know what’s happened and just become irritated with Johnny or Sally not performing well. A simple practice was created. When police are called to a home at night -- or any person called into a tense situation -- one of the first things they do afterwards is fill out a simple form and send it to the child’s school. The principal and teachers know to handle with care. They don’t tell specifics, they just let people know to go easy and be supportive rather than doing more to traumatize the child.

Handle with Care is one of those things that doesn’t take much money. Is very straight-forward and has an important stabilizing impact.

Health Impact Assessments

Health Impact Assessments (HIA) are a frequently used tool in New Mexico where we discovered that they were used by many organizations and communities. We also heard about their use in Stockton and met, as well, with the Oakland-based nonprofit, Human Impact Partners, who have trained many organizations an individuals in New Mexico.

The HIAs are a compelling example of how people working to address a variety of health concerns in their communities can develop both clarity and and capacity to communicate to others. An HIA of a statewide ballot initiative in California reclassifies low-level nonviolent crimes to misdemeanors and redirects funding to treatment and prevention. An HIA of alternative school discipline policies in Oakland, Salinas, and Los Angeles, are improving health impacts. In New Mexico one of many HIAs is being conducted to analyze how uranium mining in McKinley County affected the physical, emotional, economic, and spiritual health of communities. (For more examples in NM or nationally follow these links.)

HIAs are the way that community can work from real issues and concerns, combining them with hard data, developing language that makes the landscape accessible to others, and formulating policies that will support future work.

HIAs have been around since the 1980s and there is a wealth of resources available about how to conduct them. What’s particularly significant in New Mexico is that HIAs are being carried out by enough people in enough communities that they are creating a common vocabulary for action and learning.

School Based Health Centers

In Oakland school health and wellness centers started in the 1980s and are now in 16 schools in the district. Triage services are now offered throughout the district. The centers offer medical and mental health services, education, dental and youth development, meaning health education, youth advisory and health care enrollment services for families. There are still a lot of unserved sites. The progressive health and wellness policy recently reorganized all the services to put the student at the center. It focuses on school gardens, safe routes to school, nutrition and movement, as well as indoor air quality. Capacity building and training is done with school staff, behavioral health services, including trauma support and restorative justice, are practiced widely, and parents are offered nutrition education. Work has been done on integrating sex education into different subjects like the arts or english and there are over 80 wellness champions across the district. The health policy has been translated into plain simple language, as well as translated into the 50+ languages present in the district, to make it more accessible for everyone.

KEYS 4 Healthy Kids

Dr. Jamie Jeffrey, knew that the work she did as a peditrician in Charleston to treat children was important. And she knew that she had to go upstream and figure out what could help them be more healthy before coming into her office. A researcher, she meticulously searched the web to find out what was working elsewhere to help children be more healthy. She knew she could not transplant those practices into West Virginia, but she could be informed by them.

Starting in one area in Charleston and then another, she set out to create a new program that would help kids be healthy, focusing on eating, exercise, and the spaces and support needed to facilitate improvement in these areas. KEYS provides education, toolkits, and ideas that can easily and immediately be implemented back at home to community leaders, as well as follow-up opportunities to ensure that practices don’t get forgotten. Given her success, she and her team are currently taking this initiative statewide. Dr. Jeffrey no longer serves as a pediatrician. She knows she can make more of an impact on child health by growing this program.

Child Nutrition in Institutionalized Settings

People working in childcare centers and schools are aware that the food they provide may well be the most nutritious children receive all day. Frazzled parent or parents -- stressed by not having a job, self-medicating on drugs, trying to get multiple kids where they need to be on time -- often result in a quick trip to McDonald’s or a stop at the corner convenience store or whatever happens to be in the fridge or cupboards. The school breakfast and lunch and a backpack of food to take home for the weekend is often most of the potentially good nutrition kids get all week.

Licensed childcare centers in West Virginia have completely revamped their feeding programs. They’re buying fresh fruits and vegetables and avoiding frozen and processed foods. They’re letting go of old cooks and hiring new ones and training them on how to prepare nutritious meals for their kids. Schools in Tulsa have recognized that it takes more time to eat carrot and celery sticks than twinkies and that kids need to be hungrier to eat something not sweet rather than just throwing it away. So they’ve changed the order of the school day, putting recess first so kids burn off energy and are hungrier, then added 10 minutes to eating time (up from the actual 7 minutes kids had after they went through the line and picked up their food) so that the kids go back to class with enough good calories to see them through the afternoon.

Much of what is going on in these feeding programs are promising practices -- more work and refinement is needed. What’s a best practice, however, is concentrating on nutrition in institutionalized settings as a way to improve child health.

Bicycle HUBs

We encountered only one, in Tulsa, but it immediately stood out as a best practice. The Adult Cycling Empowerment Earn-A-Bike Program, the only program of its kind in the state of Oklahoma, has helped over 600 adults gain reliable humanpowered transportation.Transportation was a key health issue in every area we visited. Housing costs force people with limited incomes further and further away from population centers. That means they have to travel further to get to stores where they can buy nutritional foods at all -- let alone at reasonable cost -- and they often have to travel further to get to any jobs they have. Many can’t afford cars. And public transportation in areas where we listened is very, very scarce. They collect old bikes wherever they can. People can pay $35 to buy a bike, or they can spend 5 hours helping to repair and rebuild bikes. One of the astonishing things the Bike HUB reports is that 50% of the homeless people they serve are able to change their status when they have a bike -- they can get and keep a job, and have the money to pay for housing again.

Real Local Partnerships

Finally, at a process level, we noticed that everywhere people know that they have to turn to each other to get the job done. In our experience there are two kinds of partnerships. One is where a bunch of people -- usually professionals -- sit around a table and say nice things to each other. They’re cautious and careful. Sometimes meaningful action emerges -- but often not. The other is where people are called together with clarity of purpose about a community problem or opportunity. Something needs to be done and it needs to happen now. Usually family members of those most affected are front and center. And people know they need each other. NOW.

Good Practices

When we grouped practices we had encountered into these four areas, we noticed that much of what we classed as good had to do with learning. Probably no surprise here. If our intent is to create a culture of health, we’ve got a whole lot of learning to do. And that includes learning how to learn in different ways.

Over the last 20 years or so there has been an explosion of PhD and Masters programs around leadership and systems thinking and entrepreneurship. Likewise there are numerous certificate program and seminars and workshops in the same territory. In our experience, these programs often don’t reach either people working at the grassroots or those working in health-related areas. But there is a need, and people are creating the learning opportunities themselves. Promising prototypes exist -- and there’s room for improvement.

These promising learning practices fall in several categories: n Annual events that convene people from many communities and systems. n Skill building n Professional development n Community conversations

Annual Events

As mentioned, we encountered them in West Virginia, Cherokee Nation and New Mexico. Each different with similarities as well. In West Virginia there’s the “Try This” conference where, for the third year in a row people from all across the state come together to share what they are doing to improve health in their community. This June about 400 people came. In Cherokee Nation, for many years, the Office of Community and Cultural Outreach has convened a Cherokee Community Leaders Conference -- about 400 people came this June. In New Mexico about 150 people came to the New Mexico Health Equity Partnership gathering, also in June. We were able to be present at all three. This report is not the place for a thorough exploration of each of these events. There is always room for improvement in terms of clarity of purposes, design of different tracks, creating conditions for self-organizing, and structures and processes for supporting people once they have returned to their home turf.

What’s clear is that there is a hunger to be together and to support each other and learn with each other. These annual affairs are important for exchange of information, for deepening clarity on values and principles behind cultures of health, for inspiring each other to just keep going. They create community and they deepen competence.

Skill Building

Everyplace we turned, people are coming together to learn skills.

n There is a program in Kentucky people in West Virginia want to bring into schools. The program works with teenagers who are pregnant or already have kids. Rather than stigmatizing them by ignoring them and turning an eye the other way, the program is a full on encounter -training them in all aspects of parenting and child health as well as providing childcare on-site during the school day. The program is now achieving a 97% graduation rate among girls who would have normally dropped out in the past with 90% going on to postsecondary education.

n In Stockton, through the Family Resource and Referral Center, stipends are being paid to teenagers to go out and do research in the community around different community issues. They are developing research and inquiry skills, improving their self-esteem, contributing to the community, getting paid and not getting into trouble!

n Schools are trying things in new ways -- like the ‘eat, exercise, and excel’ program in Kansas where they’ve made it a priority to give every child more water and vitamins, started to eat lunch family style in the classroom, and converted the cafeteria into a exercise center used for at least two physical exercises each day.

n At the Indian Health Center in Tulsa this takes the form of merging health care and community building. So they are offering cooking classes, wellness fun and family days, reintroduction of games from their indigenous culture, and other activities that begin with the belief that people here really care, want to be well-rounded, and will always do more than is absolutely required.

n This skill building takes place in different regions in “summer camps” where individuals and families come to build new skills around healthy living. In Vinita, Oklahoma, where Grand Nation focuses on drug abuse, the summer camps are to rediscover the fun of playing physically demanding games together while eating good food.

n One of the things that people running the many farmers markets that now exist is that people have to learn how to use fresh foods - especially those they have never seen before. Selling fresh food requires teaching people how to cook again.

n In Tulsa they’re giving kids things they can do when they get mad, rather than striking out, and tools to identify and manage their own anxiety.

n In New Mexico they are teaching teenage girls how to use entrepreneurial skills to improve health at their schools and in their communities.

Safe Spaces

After school programs create an intimate space to help children deal with trauma and other adverse experiences, rather than pulling them into magnet programs during the school day. The pullouts tend to be traumatizing because of the identification and separation.

Community Conversations

In all regions people are working to build community again. They are convening conversations because they know that their communities themselves have many of the answers about how to restore health. In Oakland, one participant remarked “when you have chronic disempowerment and little or no infrastructure, there is no community”. We don’t know what we don’t know and what some expert from the outside has to tell us usually falls on deaf ears. So a question like why should I go to a doctor when I am pregnant if I’ve never done that with my previous kids (immigrant mother, Stockton) becomes something that can then, perhaps, best be approached conversationally with peers rather than by listening to an expert.

In New Mexico an organization has recognized that wealth disparity is a bigger issue than income disparity and they regularly host mealtime conversations to help families build their assets -- social, skills, and physical -- to get ahead.

Novel Practices

Everywhere people are doing things that grow out of unique, complex, local situations. They create good outcomes locally and can be studied for inspiration.

The “Try This” movement in West Virginia is a prime example. We mentioned it above as a good practice because the annual conference is similar to ones in other regions. The overall movement is also a very novel practice. This movement is in its early stages and shows much promise About five years ago a reporter for the Charleston Gazette got disgusted with the ways in which people in West Virginia always put themselves down. She wrote a series of articles about the wonderful things happening all over the state -- things people had forgotten how to see. West Virginians have, for a long time, been the victims of negative narratives from the “Big City” newspapers. When one is told you’re dumb, poor, stupid, and backward so many times, it becomes internalized. Kate Long set out to offer a counter narrative that celebrated what was working in West Virginia. After the series was published, people started saying “we want to know more about these amazing things our neighbors are up to across this state.” In 2014 the first “Try This” conference was held and it has evolved into a movement -- an ecosystem of pride -- with mini-grants supporting local work and with people from across the state coming together to help each other take new action.

Deborah, mentioned before, moved to Las Vegas, New Mexico, and started paying attention to the stories she heard of corruption in the privatized prison and how the prison was basically a revolving door -- people went in, got out, and returned again. She led the successful effort to de-privatize the prison and to create local systems to help ex-cons lead more productive lives.

In Cherokee Nation, women are the ones who have the authority in families and communities and it is often the women who step forward when they see something that can be done. That’s where Lorraine Hummingbird in Locus Grove stepped forward to create a Free Store. A member of the Cherokee Elder’s Council, Lorraine visited many people in their homes and saw what was needed as well as what others had. In many ways the Cherokee are a tightly knit community that takes care of its own. She saw that some people had more than they needed -- clothes, housewares, furniture, food -- while others had less than they needed. She saw a Free Store as a place where surplus and scarcity could meet around Cherokee values of tribe and community.

Emergent Practices

All over the place, people are trying new things and seeing what will work. They may eventually lead to novel or promising or even best practices. The practices will change as those leading them make that journey. We will not try to list them all, but want to give you a flavor of what people are talking about and wanting to do -- things they see as intimately related to creating a culture of health, that require an emergent approach: n Coal’s not coming back. But we’ve now got more flat spaces in West Virginia, where mountain tops have been removed. Are mountain top farms the way? Can we use appropriate technology to rebuild the soil in one- to two-years rather than the four to five it would take naturally?How can we use that land and what training can help former coal miners find new prosperity? n Could there be an annual Culture of Health summit and lab where people from several different regions could be supported as they map both needs and assets developing more skills to make a difference? n Could we build community across different ethnic groups with cooking classes and shared food? n Let’s work from inspiration rather than working at replication. True innovation is local. n What would it take for us to build a community based on generosity to counter scarcity thinking? n Support the gatekeepers and guides who help people navigate bureaucracy. n Keep watching for the whole system. What is the relationship between lack of transportation and incarceration and childhood poverty?

These questions and principles, and ones like them, all need to be explored further as people keep trying new approaches and see where they will lead.

Inour listening, we heard content related to the HCHW team’s current learning questions, which is included previously in this report. We also heard a lot from participants about community engagement. These recommendations relate both to community engagement and grantmaking. Throughout the course of the tour, we also heard recommendations that elevate questions that the HCHW team may not be considering currently, recommendations that begin to look at the internal conditions that need to be present within HCHW (and more largely within RWJF) in order to continue the journey towards effective and continuous community engagement. We hope these recommendations will be helpful as the HCHW team considers the process we suggest for authentic community engagement, and the proposals we provide as paths towards that end.

1. Do place-based work and provide long-term funding

Do place-based work over a long period of time, providing consistent, flexible, and timely funding to address the intersections of health in specific communities and/or regions. Build relationships with people and places. Invest in integrity and alignment, not in proximity. Invest in the capacity of people, and fund people who know the ecosystems they are a part of. Know the communities that you engage with and their specifics. Health challenges can be population-wide and nation-wide, but solutions and approaches need to be community-based. u Support natural alliances that are already occurring. People are working with those they feel connected with. They find each other out of necessity and work together. Fund people to work together more in the connections they already hold. When you see an opportunity for two people or organizations to work together, provide the space for them to know each other. u Fund community healing work. There is a lot of pain and trauma in this country stemming back to colonialism that needs to be addressed as we build cultures of health. As of now, “healing [seems to be] a revolutionary act” (Sammy, Fathers & Families of San Joaquin). Conversation and sharing stories does not erase trauma or grief but it makes it easier to breathe. u Fund organizing. Organizing has been an important part of social movements historically. u Employ people within the communities themselves to be the links between communities and the foundation. u Know the communities in which you work. Even if you don’t fund all of them, know the actors and initiatives that are building a culture of health in the communities you are a part of. Find what’s already working in communities. Connect the dots. Help people see connections they might not see. u Get close to communities. The closer we get to our community the more humility we have when doing our work. u Provide multi-year funding so that communities may do the long-term work of building a culture of health.

“We know what needs to be done. We need power, and we don’t have it” (Oakland organizer). People need power to build a culture of health. Funding organizing efforts will help build power in local communities.

2. Fund people you trust and build shared accountability

The extra activities here at the clinic help us understand that people here really care. Being well rounded and doing more than necessary. It helps build my trust in them. The cooking classes, wellness fun and family days, playing cultural games like stickball, are all great ways to meet other families and build community. I feel less alone that way.

Laretha, Tulsa, OK

When someone trusts you, they will tell you anything. And then the stories get bigger!

Tina, Oakland

Trust is the result of many smaller actions that lead to healthy, honest, open, relationships. Therefore, build relationships with people that have similar goals as you. Create the relationships for people to bring their own experience and knowledge into the conversation so that the picture can be more complete. Be ok with people’s ideas being different than your own; have the necessary (and sometimes difficult) conversations to find the way forward, together. Be in relationship with people to understand what solutions they see. Listen to understand what more is possible. By taking actions such as these, the bond of trust will be built.

“We know what we need. You need to trust us and support us in finding our own solutions.” (Oakland community organizer) u Begin with the relationships you already have. Find logical entry points into communities, like regional funders, regional networks of funders, partners you already have, organizations you have already funded or worked with.

“Our job is to help our communities. We don’t always know what that means, but we know they’ll tell us.” Mark from Cherokee Nation Community Outreach u Be ok with people’s ideas being drastically different than your own. When they are, ask questions to better understand their perspectives and approach. u Ask questions to understand. Listen to the answers. u Convene people to share ideas and generate solutions collectively. u Be clear and honest about what you can and cannot do. u Be present yourselves. u Be clear about what you don’t want to fund. One participant in West Virginia shared that she had applied for support to address substance abuse in West Virginia, and received the response that the foundation wasn’t supporting substance abuse, but that wasn’t clear in the beginning. If they had known, they would have applied for another project. u Tell applicants why you didn’t fund them so that they can learn from it. “Don’t hide behind vague language - if you want us to take a risk and be truthful with you, model that behavior for us.”

Ͱ Study Otto Scharmer’s Levels of Listening.

“If the foundation wants to know what life is like here, they should come here themselves” (Phoenix organization and community leader). This wasn’t a message across all communities, but it was true across some. If the foundation wants to engage more deeply in communities, it can become a held value, and be practiced inside the organization. (We explore this view more in the community engagement model.)

3. Engage community members to be decision makers

“Community Health Centers in Tulsa have 50% of their boards made up of users of the centers. We often have the wrong people at the table. They are not the ones who need the services, they shouldn’t be deciding what happens.” (Community Health Worker, Tulsa)

“Sometimes the structures you impose don’t work for us, things are different here, for example, common evaluation. Can we develop that together so that it works for all?” (Funder, West Virginia) u Create advisory committees made up of community members to advise on projects and make funding decisions. u Engage community to make funding decisions. u Find ways to let the communities themselves decide how the money is used.

Many participants in conversations, from local foundation staff to community members to organizational leaders, spoke of shared decision-making as a way to bolster trust and amplify the good work already being done in communities.

“Let us decide how we use the money. It’s not my money, it’s not your money, it’s our money” (Community organizer, Oakland) “It’s just time to do this work. We know what to do about ACEs, social determinants of health, nutrition, equity. We know what else is possible and it’s time to get going!” (Community health worker, West Virginia)

4. Provide Flexible Funding

“If we raise an issue likes ACEs in a community, other needs will rise to the surface. If surfacing traumas like ACEs, organizations must be ready and able to respond to the consequences. They need access to funding to be able to respond, and not to have to go through the bureaucratic process of securing a grant.” (Director of a teen pregnancy program, West Virginia) u Have flexible dollars within the HCHW team that organizations already receiving grants can access easily in whatever structure makes most sense for the Team u Have line items in budgets that are for flexible purposes u Fund as movements happen – in the moment, and quickly.

Organizations are working in systems, they are not working on isolated issues. They need dollars that are not project-based, but rather dollars that respond to the present needs in a given time. Sometimes that is about bolstering a project, sometimes it’s about filling a gap, sometimes it’s about paying a debt to increase the financial health of the organization. Whatever the need, if the foundation funds based on trust and shared responsibility, the needs of the whole organization and the systems they are working to influence can be considered and addressed in a timely fashion.

During this tour, we also got to hear Alicia Garza of Black Lives Matter speak to a group of funders, during which she said: “Fund us to innovate and test and iterate and find out what works. And don’t ask us to define deliverables in advance -- support us in finding ways to notice what’s happening and to define the measurements that tell the story of the work we’re doing. Movements and organizations are responding to crises now and need funding to do that. Philanthropy in its current moment doesn’t know how to fund Black Lives Matter.” (Alicia Garza, Black Lives Matter)