14 minute read

of a c u Lture of Hea Lt H

People depend on them. They deliver medicine and care and love and dignity. They are there, solid, providing ground on which their patients, their community members, can stand.

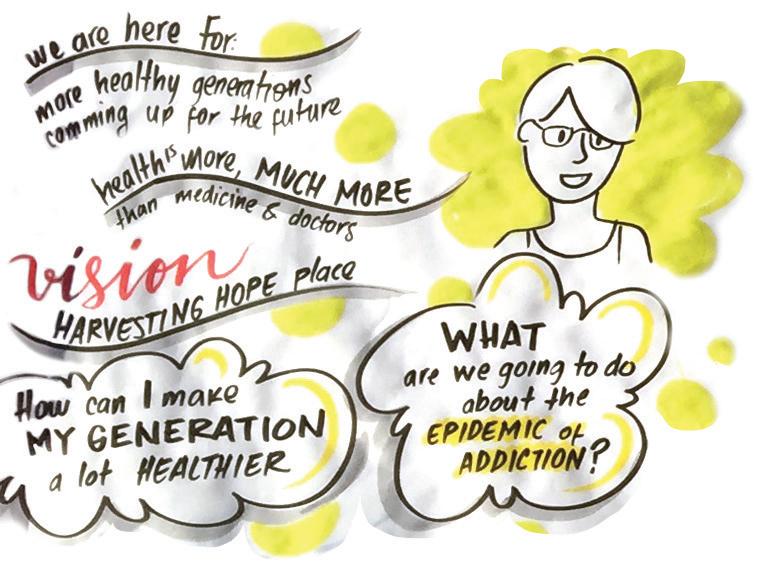

Christina in Anthony New Mexico knows that food is important. Growing it. Tending it. Harvesting it. Preparing it. Her mission in life is to reintroduce people to food at La Semilla Food Center. Her passion for people and the land and that which grows from it guides La Semilla. She is teacher, an organizer, and farmer. She is one of several core staff who lead this vibrant organization.

Sammy in Stockton, California, founder of Fathers and Families of San Joaquin, an open-hearted, inspiring man full of passion and energy, was convicted for gun violence at age 18 and is now giving back to his community in any way he can. He’s a leader, political activist, and mentor who knows that healthy families and communities are the cornerstone of a healthy society. That protecting children, honoring women, and respecting elders is essential. And that safe, strong, and resourceful communities treat individuals and families equitably and honestly; promote positive family images and recognize family strengths; and create opportunities for individuals and families to achieve health, wellness, and their human potential.

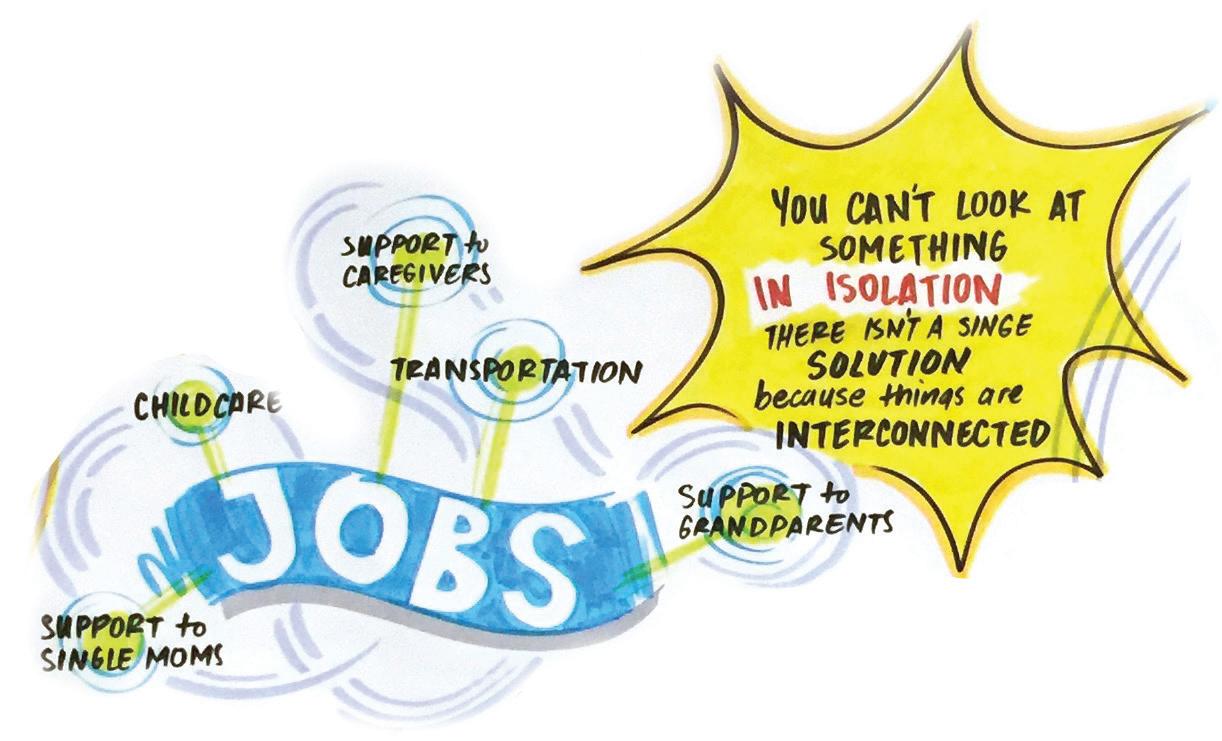

Our lives have filled with these people and their stories. What do they have in common and how are they part of this landscape of a culture of health? They are each people who build and serve community from a place of calling. They create this culture of health. Most are not trained in systems thinking -- but they each are systems doers. They know everything is connected. We kept being reminded of this in encounter after encounter. Drug abuse, nutrition, lack of income, transportation, housing, obesity, incarceration, medical care -- they are all connected. They know they can only work on one part of the system at a time, but they carry an awareness of it all.

And not surprisingly, children are always at the center of the system. The licensed child care providers who know that what they feed their children is likely the only solid nutrition they will receive all day. The grandfather raising his son’s children. The mom raising her deceased sister’s children. The people who create foster homes so children can be saved from abuse. The ones who say with sadness that we must forget about the adults and care for the children. Standing in the contradiction that true child health requires healthy families but how to move forward when families are seemingly irreparably broken.

If we want to build a culture of health, these are the ones we need. They need to be trusted and supported. They know what work needs to be done. The somewhat astounding good news is that it doesn’t take rocket science to build a culture of health. The issues and principles and practices are widely recognized and understood. People know what’s important. They know how to do it and where to turn. They understand. They need to be listened to and witnessed. They benefit from being connected to one another. Sometimes they need particular kinds of learning to guide them into even deeper work. They don’t need to be told what to do. They are action learners. They stumble and they fall and they pick each other up. They are in this work together.

Values

Certain values -- speaking the truth, doing one’s part, welcoming others, making a path together, taking a risk, respecting both self and each other -- are the threads which weave together a culture of health.

You know this, of course, given your own prior work on making health a shared value point. Let us share a little of how it has been most alive in our listening. These are simply the values of healthy community. Perhaps they are more present in communities where money is often scarce and people know they must turn to each other. How do they treat each other?

because no way can this be done alone. They find those they can trust.

They speak the truth and share deeply personal stories with each other. Some shame may be there, but it is mingled with pride. They have been beaten down and they are surviving. There really isn’t room for posturing here. The petty politics of boardrooms and committee meetings don’t have much of a chance. Lives are at stake -- and they know it because they see it every day and it breaks their hearts. They turn to each other,

Welcoming others is essential and it is what people in community know how to do. They know that they need each other. Even if they don’t particularly like this person or that, mostly they know they are all in it together. This welcoming happens at multiple levels. It is the welcoming of community folk in Williamson, West Virginia, who come together for a morning to talk about a new “health passport” program being launched through the Health And Wellness Center. They don’t talk so much about will this work, but rather about what they will do to make it work. It is also the welcoming of top professionals from across the state who come together in a newly formed statewide coalition on ACES. The energy is a bit different -- they have budgets and people they report to. And, there is a deep welcoming and appreciation that we must work on ACEs together.

When people come together with this spirit of welcome, they know they must make the path forward, together. There’s no single master plan. Of course, there is much to be learned from the work of others. But programs that help to create a culture of health must be planted in local soil. People must come together and try and fail and succeed and keep coming back. Some get worn out and step aside. Others step forward. The programs need to be funded, but they do not stop when the funding disappears. People just keep looking for another way. They know the direction they want to head and they find the next step and the next. The work of Grand Nation in Vian, Oklahoma is one example. Community folks, no longer turning a blind eye to the rising tide of drug abuse in this small rural community, turned to each other and said we gotta do something. They didn’t where to begin. But they figured it out and now, five years later, work in many aspects of the life of their community.

They take a risk, both in terms of speaking of their own personal frailties, and by their willingness to do something they have no idea about how to do. The woman who now runs the food pantry at the Welcoming Table in Turley, Oklahoma, didn’t even want to be there. But she sighed and agreed to come for one afternoon a week.

Now, she tries to get one afternoon a week off! She uses the small resources they have to drive her big truck to food banks and stores and restaurants and farms to find the healthiest food she can to share with her neighbors. She took the risk of having her heart opened even further and the risk of doing many things she had never done before.

She has come to respect herself and each other. She is not alone in this. The work of building a culture of health is based on respect. It is based on helping people regain their pride and their confidence. Restore dignity and health will follow. A young man from Santa Fe lives in the house built by his grandfather and where his father grew up as well. He sees how his neighbors are plowed under by gentrification and pushed further away to places that are food deserts with no jobs and dwindling hope. So three times now he has organized the opposition to the City’s increase of bus fares, which just increase the cost and decrease the likelihood of people getting good food and good jobs. He names what the city tries to do as disrespectful and unkind.

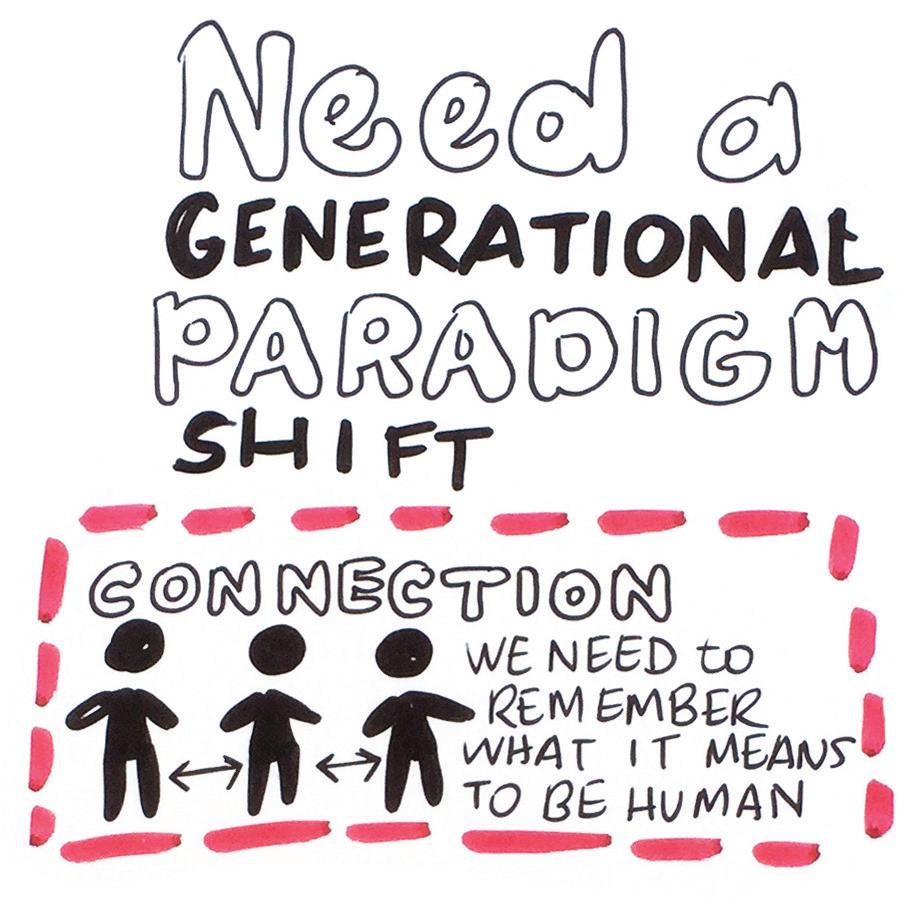

These phrases only begin to describe values which are present when a culture of health is restored. They reach into this sense of people connecting with each other and with the land and with the very nature of life. A culture of health emerges from a lived experience of caring and being cared for. Really, it is just what community is truly about.

Built Environment

A built environment which provides easy access to the beauty of nature that is walkable and bikeable and sensitive to the needs of those with mobility challenges provides the pathways that connect community. What are the characteristics of a built environment that define this landscape?

Bikeways and pathways. Affordable housing. Parks. Art. Beauty. Nature. Farmers Markets. Stores with real foods. Buses and bikes.

It all exists together.

At the Welcoming Table in Oklahoma, the volunteer staff pay attention to the details: noticing the family that consistently overlook good available food choices and engaging them in a

I used to take three meds for blood pressure. Then I moved from east to south Charleston where I could ride my bike and walk, I had a grocery store and everything changed. It’s not just about treatment, it’s about assessment of causes.

Deshaun, Charleston

conversation that eventually reveals those foods require water to prepare them as well as a way to heat that water -- something they lack in their ramshackle home. It’s hard to be healthy without affordable housing.

In Williamson, West Virginia, people are walking again. Walking clubs and keeping track of personal achievements -- and doing so with others. In New Mexico, the health councils created walking maps with safe routes for pedestrians that doctors can use to prescribe walking. Nothing new was built, just re-using those same old town streets and byways.

How do we construct build environments that support a culture of health? What is the combination of public will and public policy that creates cities and towns and villages that are both livable and healthy? What are the questions and opportunities we must pay attention to?

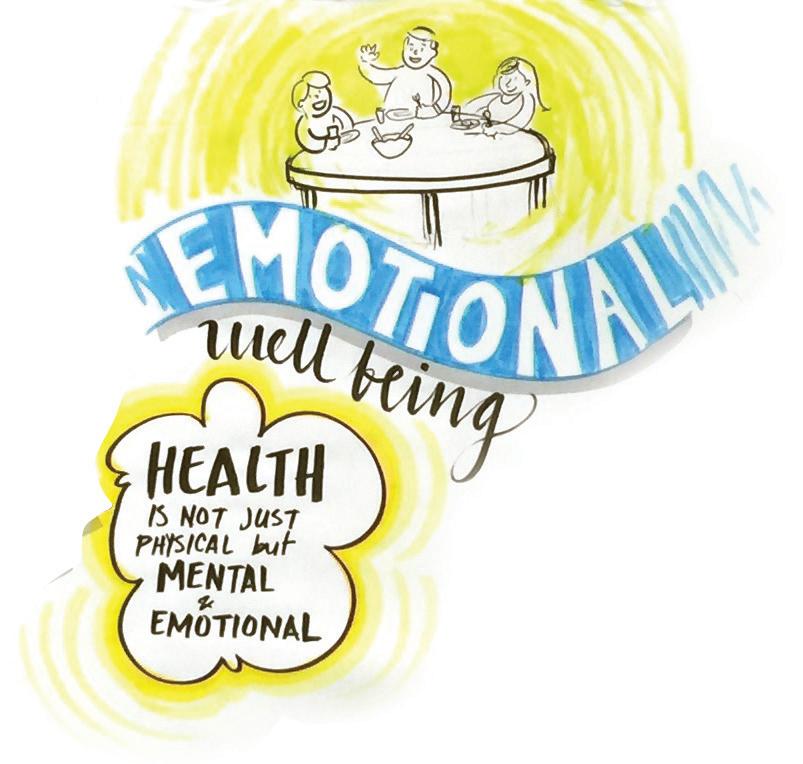

Critical Health Issues

In each community we visited, people were coming together around particular pressing health issues. What was most striking was that people -- moms and dads, teachers, government workers, health professionals, community members, children -- knew what the issues were and knew what needed to be done, even if they were not completely sure what to do next. A West Virginian doing her doctoral dissertation at Johns Hopkins on community health expressed it eloquently: what’s going on in every community is exactly the same and totally different. Concern about diabetes, and also shortness of breath, tiredness, and lethargy are entry points for working on nutrition and exercise as antidotes for obesity.

It’s not long before conversation turns to the economy and lack of jobs. People without income don’t have the cars or money for gas to drive 30 miles to the store that has fruits and veggies they can’t afford to buy. Their esteem is low and stress is high and it gets taken out on the spouse and the kids, perpetuating cycles of trauma and abuse. Helpless leads to just one more drink or hit, a longing for escape.

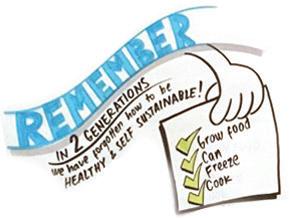

The quest for nutritious foods leads to a recognition of food deserts, the decision to grow community gardens, work to create farmers markets and other public/private partnerships, operation of food banks and mobile food pantries that are at least trying to improve nutritional quality.

A glance at drug abuse reveals families and communities where hope is short supply -- no jobs, isolation, no vision of any future in particular, sometimes chronic pain and sometimes making meth the only visible path making money and getting temporary release from despair.

My mom was an addict and she chose addiction over me before I was a year old. It floors me that addiction can have such a stronghold over you that you can abandon your own child.

Jennifer, Oklahoma

Then the conversation turns to who’s in jail and who’s out and likely headed back. The revolving door of incarceration makes it easy to blame someone until that someone is a cousin or neighbor or son and you know that when they come out they can’t get a job and even if they find one, they can’t get a loan for a car or a home. --

I was in and out of jail. That’s what I knew. I was born into this world, I didn’t create it. People take their lives when they don’t believe change is possible. It’s a mental health issue. I spent most of my life angry. The circumstances in our lives shape us. Trauma is poison. Now my life is about creating power, about caring and seeing each other as people.

John, Oakland, CA

And always people talk about children. Grandparents raising grandkids. Older siblings raising the youngsters. Agencies trying to improve the quality of foster care and foster homes because it’s the only chance kids have. Parents trying to recover dignity and their role as parents. Childcare centers that are the only points of stability in stressed and overworked households. How can all these, and more, be supported in the struggle to raise healthy children.

I do volunteer work to keep busy. I want to understand more about my community. I just got my kids back. It’s not easy, but I’m taking them to the park to spend quality time. I also take them to the library and they love it. I try to do more for my kids than I do for myself. I’ve been sober for 2 years now.

Larinda, Stockton

In communities where a culture of health is growing, community members know they can only do one thing at a time -- but they also know the restoration of health requires the transformation of life. They see the interconnected system and they reach out across all boundaries to form relationships with others who are making a difference as well. Some are content to focus on one particular issue or opportunity and do more good than harm as they try to keep things from getting worse while unsure of how to make things better.

A Call To Healing

There’s an acceptance of how both historical trauma as well as stresses and adverse experiences encountered in life play a critical role in well-being. People just know that these traumas don’t vanish but can be seen and acknowledged in ways which diminish their power.

Vicki Downey, a Pueblo elder in New Mexico, knows that health cannot be restored until trauma is released. She simply goes where called. Working mostly with women and mostly with native populations, she shows up. She spoke of a particular trauma circle developed in Pueblo communities where women sit in a circle, each holding a rock. The first woman, from the oldest of times, speaks of the oppression of the European colonialist who excused their egregious behavior with a papal decree that natives were less than human. And she places her rock in the sack and passes it to the next woman in the circle. They each tell a story of exploitation and disregard as the sack passes, getting heavier and heavier. Finally, the woman of our current times is presented by this heavy sack of rocks, overflowing.

Another hispanic elder we met a little later says there’s too much focus on historical trauma -- people just need to get out and exercise and eat better. But she says these words with kindness and respect. People are different, yes, and when members of community find the place they can step forward -- not trying to do everything, but just doing what is theirs, health happens. When they turn to each other and do it together, a culture of health becomes visible.

Convenings

Creating a culture of health requires that we come together as communities, having conversations that matter -- exploring, wondering, synthesizing as we learn from our own experiences, hear about the experience of others, and work together to co-create a host of new possibilities.

We need each other to create a Culture of Health. Community is required and community learns about itself when it is convened. We have witnessed two levels of convening and would love to see more of a third: 1) Local; 2) Regional; and 3) Translocal.

Of course, local. Within systems and organizations. Across communities. This listening tour itself was a context for more convenings. We helped to bring people together who had a hunger to hear each other’s stories and to also tell them to people like us, from “away.” In a connected community, people turn to each other and they listen, learn, and cocreate. Some of these convenings are the meetings we’re familiar with -committees and groups and community gatherings. Others are a little less visible -- the conversations side-by-side in the community garden or while nibbling on a handful of berries in a farmer’s market.

We saw one stark contrast to these kinds of convenings when we were in West Virginia. We were invited to show up one morning in a small town where a mobile food pantry would deliver foods. There was no convening. There was just a sense of helplessness. People waiting in line to get their number -- arriving hours early so they could be first. People waiting in line for their number to be called. Some conversation, but mostly waiting. Subdued voices. Waiting. The mobile pantry provides an important service. Is there a simple convening around things like a mobile pantry that also helps to build community? What else might be done that helps to restore a sense of dignity and possibility? Can pressing immediate needs be met in a way that also restores hope?

The gathering we hosted at the Church of the Restoration in Tulsa was one memorable example. Reverend Davis, a black elder now blind, called his people together. Until June they did not sit in the same room with each other. Because of Reverend Davis’s dual career as minister and health department official, several ranking members of the city and county departments of health were there. Because his church is a sanctuary,

Landscape of a c u Lture of Hea Lt H members of the community with little or no money were there. One woman reminded us that since she had a garden, she was not poor -- she just didn’t have money. Others came because they heard something interesting might happen. Sitting in circle with each other, one after another shared part of their story with each other. Their hope and their longing and their frustration and anger.

As our three hours drew to a close, one woman said we need to keep doing this. I didn’t know all of you before and there are more out there like us. What if we start to have a potluck meeting once a month to be with each other and think together about what we can do here? A date and time were selected. They will meet again.

When this kind of engagement is present, there is a chance health will be restored.

We didn’t know of three regional convenings when we selected the regions for the listening tour. But once we started reaching out to people we were immediately invited to join the Cherokee Community Leaders Conference, the Try This West Virginia Conference, and the New Mexico Health Equity Partnership gathering. In each case, a region wide system was being convened. To support each other, to learn with and from each other, to find information, solidarity, and inspiration in each other’s presence.

When creating something new, it is so easy to feel alone and isolated. And that can lead to despair and to giving up. The people at these gatherings were not giving up, they were going deeper with each other as they gained strength. As meeting designers, we were both impressed and noticed areas of possible improvements. Bringing our graphic recorders and sometimes a little of our design skill was a welcome addition. A culture of health is hard to build or sustain without these kinds of connections.

And, we also found ourselves yearning for the next level. We call this level translocal and it is where people from very different local systems over a wider geography gather from time to time to share and learn. We did not encounter such gatherings on this tour, but we know them from our prior experience in extended communities we have helped to convene. While it is very important and inspiring to gather together with people from West Virginia, it goes one step further when one sees that what we face and how we face it in West Virginia is not all that different than what people face in New Mexico or Oklahoma or Oakland or Stockton. We are in this together.