18 minute read

9. Create policy from the lived experience

We collectively create results nobody wants. The disconnect between policy makers and their experiencing the impact of the decisions they make is part of the issue. Often policy makers don’t know about the lived experiences of communities, they lack context and have to make decisions based on generalized or incomplete data. We see great potential in creating policies from the lived experience. At the New Mexico the Health Equity u Engaging communities in policy making. People in communities feel the disconnection between policy makers and their awareness of the impact the policies that they create has on communities. Communities want to be involved in policy making. u Invitational vs punitive policies. In West Virginia the question arose if a higher tax on tobacco will actually make people stop smoking or if it will just mean less money for children’s food will be available. In Oakland community organizers were opposed to the tax on sodas. In both cases it felt to people like a solution imposed on them and not one they would feel supported by to make healthier choices. u Programs and policies are both important. Communities told us that foundations should not just focus on policy change. In Oklahoma, New Mexico, Oakland, and Stockton we heard many stories about the impacts of programs on people’s lives. For example how valuable summer camps are for children especially from poor families. Often that is the only place where kids get a meal during the summer when school is out. For example free cooking and parenting classes offered by the Indian Health Center in Tulsa were seen as invaluable by the parents.

Partnership gathering, 64 representatives of several community organizations from all across the state came together to do exactly that. Building on the breadth of advocacy, research and lived experiences, participants provided recommendations, that are rooted in community strengths/assets, to inform a statewide policy agenda that would lead to a healthier and more just New Mexico.

Ͱ One idea we heard was the formation of community boards that would vet local policies before they could be passed. Another idea was the need for capacity building of local policy makers especially around diversity and equity in policy making. It was felt that all policies should directly address poverty and equity and take the impact on families into consideration.

Ͱ In Stockton community organizations got together to propose to city council the “healthy by default kids’ beverage ordinance”, which means either water or milk shall be served as the default beverage in children’s meals. It was celebrated as a success and it is the second law of its kind adopted by an American city, following the city of Davis, California.

Policy

Thisproject has been an action-learning initiative from the very beginning. It is a listening tour that has been guided by deep listening throughout. At the outset of the project, NewStories and RWJF met to listen together for the deepest intentions behind the project and looked for what success would really mean. Based on those insights the NewStories team started to talk with colleagues across the country to find what regions were the right places to begin this listening.

How We Defined Success

In March, NewStories and the HCHW team came together to kick off this listening tour. We refined the objective of the tour, we explored what success and failure would look like, and we began to explore what authentic engagement meant as we designed and conducted a listening tour that aimed to learn from communities that experience hardship, aiming not to be extractive but rather additive.

After our initial meeting together in March, one main question rose to the top as the aim for the listening tour. The goal has been to learn, directly from parents and caregivers, how the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation can engage families to support a culture of health. Additionally, this national listening tour sought to answer the questions what is the living experience for all families, especially marginalized ones? What do marginalized families need to thrive? And finally, what issues are important to families in need?

Other things that were mentioned were both issue-based and process-based. For example, given the emergence of the HCHW team, there should be a deeper focus on obesity during this tour. And how do we listen to families in a regular way as a foundation? What are the conditions that need to be present to support that? How can engagement mean less about studying and more about understanding? And how do we engage affected populations versus having an issue-based objective?

n What you have read in this report relates to three different layers of this objective: n Stories that provide insights to the HCHW current learning questions; n Stories that provide insight as to how communities are building a culture of health, stories of everyday people interested in making change; and n Insights and recommendations from our experience as to how RWJF can deepen community engagement values and practices.

Authentic Engagement

RWJF and NewStories both shared the intention that this process not be extractive, but that it add value to communities we engage with. While designing and conducting this tour, we never lost sight of that. We thought creatively about what we could leave behind. As NewStories, our gift lies in process design and facilitation. And so, we offered that to communities. Instead of asking community leaders to convene focus groups for us, we asked what the conversations were that they already wanted to have with their communities that related to the goals of the tour. We also sat in on gatherings that were already planned. We offered our design thinking support, our facilitation support, and graphic recording. In some places, like Phoenix, given the short timeframe of the tour we weren’t able to have community conversations, but the seed has been planted and watered, and is waiting to grow.

We have also prepared this report knowing that we will share it with the communities themselves. It is a small step, but one we feel will give something back to the individuals and communities that shared so willingly with us. There is more work to be done, and we have offered our partnership to all of those who have been involved in this listening tour.

What would success look like?

At the daylong co-creation meeting between RWJF and NewStories we asked everyone to brainstorm how failure, success and epic success of this project could look:

epic SucceSS

q Diagnosis only and same old story: things are hard (food, money, jobs, transport etc) q Families don’t benefit and we inadvertently antagonize, alienate, marginalize, use & take advantage of them q Sessions and report don’t provide added value for partners we work with q We don’t make miss-steps or learn from them q Our process for authentically engaging families do not change ie report sits in the closet u Clear insights and expectations for how RWJF acts u Deliverable is more than stories of parents, learn new perspectives from diverse groups (geographically, income, race/ethnicity) u Families start to get a sense of empowerment from participating in these sessions u Outcome of those sessions includes a clear set of actions, not just diagnosis u Sharing valuable and useful info from the focus groups w community partners and participants u Triangulated insights from other engagements with partners (e.g., Southern States listening tour and Baltimore engagement) u We have new strategies & tools to do our work more effectively - increase our impact and make actual changes to our processes at the foundation that take lessons learned from this effort -> to better engage families in all our grantmaking steps/learning u Mixed results, a lot learned from missteps, a lot to do better next time p Great (meaningful & authentic) & valuable insights from families to inform our work p We get great real life stories p New relationships built and ongoing p Families walk away feeling heard and valued, and they have gained new skills/ knowledge/empowerment/solution p Clear immediate pathways for participants & partner organizations for the ‘now what?’. People are empowered and mobilized to act p RWJF start to set a new norm for how we engage with families directly and continue this kind of work with all themes, consistently, & intentionally p We have a process in place for continuously refining strategy based on parent & youth voice p This helps us to change the world

Epic Success

We have learned deeply about a model for engagement and include recommendations and proposals (as a separate document) as to how RWJF can deepen your engagement with communities, both in terms of building relationships and in terms of organizational practices and capacity building. Through existing relationships of our own, we have built and deepened relationships with local actors on the ground who are excited and interested in the questions that RWJF is asking and who are interested in engaging on a more consistent basis. Many are interested in partnership. We heard countless times that people felt grateful to be involved in these conversations. From the mouth of one participant in West Virginia: “This has been so cool. Probably the coolest thing I have done. To be involved in a national conversation about health? Really amazing.”

Success

Using a systems view, we have followed the people employing emergent strategies that are trying to build a culture of health in their communities. We have talked with parents and caregivers, and with individuals who are also community leaders, stepping into roles to help their larger communities be more healthy. We have spoken with individuals coming together to address ACEs across their state, government workers, nonprofits, activists, academics. We have spoken with grandparents who are worried about their children and the way their grandchildren are being raised. We have talked to young people who, with just $1,500, are building community gardens to address obesity and food access challenges. We will share this report back with them, as a way of supporting their interest in learning from one another.

Failure

We heard from some groups about their disregard and distrust of our efforts. In the words of one participant in West Virginia: “We’ve heard it all before. People come here asking questions and offering ideas, and nothing ever happens. The only good thing that’s happened here is this health center. The only thing.” We also had challenges engaging people who were in a more transactional engagement with the organizations that convened them. For example, when attending mobile food pantries, events where recipients had to register with their IDs, receive a number, and wait in line to get their food, the deeper questions around community health and challenges fell completely flat. We have learned from these mis steps, and will share insights throughout this report.

How We Engaged with Communities

This section details the community engagement process we used during this project.

income families towards a culture of health. In some cases we had contacts with community leaders directly. We started with people we are connected to/know best and moved from the ‘inside out,’ i.e., rather than starting with cold calls we started with the relationships we already had, and from there learned of relationships that already existed in communities. Relationships undergirded this whole tour. We started where we could, and followed threads where they took us. We worked to understand the ecosystem and context as much as possible in this initial phase.

Given ample freedom to choose locations, we knew this tour would not give us a representative sample of the U.S.. We chose locations as diverse as possible based on culture, demographics, as well as geography. We contacted more regions and locations than we ended up working in, due to our short timeline. We began considering ten regions, and ended up working in four.

Step 2: Outreach

We reached out to people in our networks - both professional and personal - and asked them to connect us with community leaders and organizations who are working with low

We created a short visual description of the project to share with our contacts, and had initial conversations about what we were hoping for. Where the conversations seemed to lead somewhere, we followed that. Our aim was to understand who the health leaders were in communities and what roles they filled. It ultimately turned out that these individuals ranged from community members who have stepped into both traditional and nontraditional leadership roles because that was needed in their communities, to nonprofit leaders, to healthcare professionals, to small business owners. Very often, these people were parents and caregivers themselves. And more often than not they had stories to share themselves. We quickly learned that labeling people “citizen leader” or “parent/caregiver” was an unnecessary distinction to make.

Communities and circles already exist. It began to make more sense to listen in circles where the trust had already been built, instead of creating new circles in which to listen. Circles did not need to be “identity-based,” unless defining identity as being a part of a certain community.

These initial conversations were done mostly at distance -- with in-person meetings when possible. As we identified community leaders and gatekeepers, we began to set up one-onone conversations for a first trip to the regions we were listening in. We did this in several locations in parallel. This way, we we were able to iterate and improve our approach as we progressed, making effective use use of the short amount of time available for the listening tour. In short, this phase of the tour consisted of:

1. Identifying potential regions/locations.

2. Having initial conversations with personal and professional contacts in regions from afar.

3. Amassing contact information of citizen leaders.

4. Setting up in-person meetings with citizen leaders.

5. Meeting in-person with citizen leaders. When possible, identifying opportunities where our facilitation could be of service or in synergy with conversations the community already wanted to have and we could help catalyze.

6. Reflecting and sharing learnings as a team. Identify what is similar across regions, and what is different.

7. Letting regions go as necessary, as it became clear that goals or timing did not align.

Ongoing: Learning about context, trust building, and authentic engagement

On our first trip to each region, we spoke one-on-one with community leaders and gatekeepers to learn more about the local context, build trust, and discuss how we could best convene families and caregivers directly. In this case, building trust meant listening, asking questions, sharing our goals, asking for reactions to those goals, and following the ideas and inspirations that emerged. Building trust meant acting in solidarity, which has a horizontal approach, honoring the knowledge and experience in the communities themselves.

Authenticity meant being clear about the scope and timeframe of the engagement, and clarity around what promises we could and could not make. With this listening tour, we were clear about the questions that RWJ was asking themselves about community engagement and grantmaking strategy, and that that there was no guarantee that funding would follow after the tour was over. We were clear about the timeline. This clarity also included being honest about not knowing what RWJ would do with the stories and information gathered from the tour, and what the future might look like. We could not promise continued relationships or engagement. What we could promise was to share the information back with the communities themselves. And we shared our own intentions with the project - to make this report something that would be alive and dynamic for the foundation, with information, models, and proposals that team members could work with and make sense of in different ways. We used an appreciative inquiry approach in this tour. Rather than focusing on diagnosing what was not working, we looked for what people are already doing to build a culture of health locally. Inherently, who, and what, is still falling through the cracks emerged as well, including what the continued challenges are. In our interactions, we paid attention to cultural and relational dynamics, being especially sensitive to power and privilege.

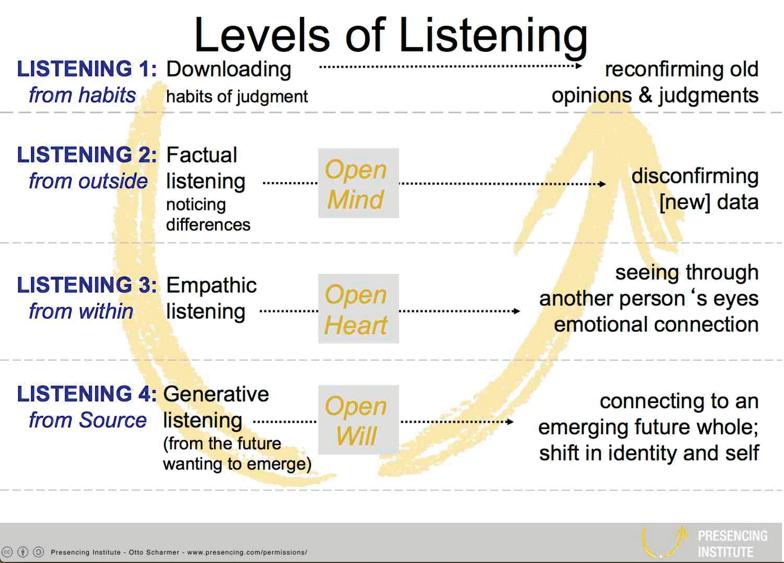

We listened deeply. There is much work to refer to on different levels of listening. If there is one central learning from this report, it is that listening is the most important central tenet to authentic community engagement. One model we work with is Otto

Scharmer’s Levels of Listening.

Listening is an important part of building trust and recognizing power and privilege. We can listen at different levels, as described in the image above, levels where we either bring or suspend our own perspectives and judgement. There are decisions that we can make about how we listen, and what goal we have with listening. As we work to learn about communities that we are not a part of, Factual Listening and Listening from Within (levels 2 and 3) are desired levels of listening. As we grow towards building possibilities together, a much deeper and longer-term commitment, we ideally move into Generative Listening, where solutions begin to emerge that we may not have imagined previously. (With this tour, we didn’t get to Generative Listening (level 4), given the time frame or the level of engagement in the communities.) incarceration, housing, in the language of foundations, but I can also talk about if from the grassroots voice. We need more of these translators” (Olis Simmons, Youth UpRising, Oakland). In our work, the initial work we did with our own contacts, and subsequently the citizen leaders and gatekeepers served in both building trust and working with and through individuals who were already a part of the communities in which we were conducting the listening tour. We didn’t always see success in this phase of the project. For example, in Oakland, in a circle with community organizers, while people were sharing very honestly and openly, some of the desire shared was that RWJ be present if they were going to convene another circle of community members. They didn’t want us as “translators.” “If RWJ is interested in deeper community engagement, then they should be here themselves.” “And what about employing people in the communities themselves as translators? We need jobs, and we know these communities, we are a part of them. Community engagement means investing here.”

Step 3: Location-specific interaction design and gatherings

We cannot expect to do this work of generating solutions or possibilities alone. Different circles and communities talk about a culture of health in different ways, and we all see both the challenges and potential solutions differently. Understanding the local context is a challenging piece of work, and is a critical piece in laying the foundation for continued work in community. Having translators who can speak both the language of the foundation and the language of the community is an added bonus if possible. “I can talk about all of this stuff - policy, mass

Through our conversations with community leaders we began to identify possible paths forward. Sometimes this meant attending a conversation that was already planned, for example, the Statewide ACEs Coalition in West Virginia, and paying close attention to the conversations about parents and caregivers. Sometimes it meant convening a group of patients at the only Federally Qualified Health Center in a region and conducting a more facilitated conversation. Sometimes it meant meeting with a group of community members in someone’s home. Given the short time frame of the project, we worked hard to sense what opportunities were arising, and followed those where we could. Flexibility was important during this stage. Our aim was to be smart with our use of resources and time.

Failures and Learnings

Time: Conducting this tour in a finite amount of time was a good thing, however, the short amount of time to prepare for the tour, including building relationships, learning about the context of a place, understanding if there was an opportunity to convene circles, and finally, convening circles of authentic engagement where the HCHW learning questions could be directly addressed would have taken much more preparation time and a much deeper level of engagement, however defined, for this project.

Sometimes, the gatherings didn’t work. Specifically, attending mobile food pantry distribution events with the hopes of talking with users did not work. These gatherings were very transactional and not conversation-based. People arrived, registered, picked up food, and left. Having conversations was nearly impossible. The setting of the events were not such that asking people invasive questions about the health of their families and communities was comfortable nor appropriate. We employed practices to try to invite people into conversation, and they rarely worked.

Ongoing: Harvesting

Throughout the entire tour, including the preparation stages, we were making note of insights and stories that would serve the larger purpose of this tour. During both the one-on-one conversations and the larger group gatherings, we took detailed notes ranging from direct quotes to insights to summarized stories. We trusted that we would all be making note of different aspects of conversations as a way to round out both the contexts and the stories we were listening into. We also had two graphic harvesters with us to capture the larger flow of conversations and reflect back the gatherings and the individual voices to those who had shared with us.

Step 4: Collective Sense Making

Throughout the two months of listening, both in the oneon-one conversations and the larger group gatherings, we came together as a team as often as possible to share our insights and learn with one another. From these conversations, we made adjustments to our community engagement approach.

At the end of the listening tour, we came together as a team to make sense of the stories we had heard in order to turn the tour into a digestible report and recommendations. We reviewed all of our notes, taking snippets of conversations and putting them onto Post-its on a large, open wall. We then began to cluster Post-its, coming to some sort of understanding of the different types of insights and stories we had. Through this clustering process, and the iteration involved, we built both a structure for the report, and found our red threads -- the themes that tied the report, and largely, the tour, together.

Step: 5 Feeding the Information back to Communities

Throughout the tour, both in designing and conducting it, we have been conscious of power and privilege, and not wanting to be extractive with the tour, but to have both the listening sessions and the end product be useful to the communities themselves. Participants in the listening sessions also shared how valuable it was to be able to learn from outside of their daily circles and communities. Throughout the tour, we have spoken as a team of the desire to bring all of the actors together across regions for them to share and learn from each other.

When writing the report, we held the communities and individuals in mind as an audience for that product. While we would ultimately like to bring people together physically to learn from each other, share ideas, and build relationships across regions, sharing the report is a first step in feeding the learning we have experienced back to the communities. We expect continued conversation around the report with those who receive it.

Questions we asked

n What are you seeing that’s making a difference in creating a culture of health that includes marginalized families?

n Who is falling through the cracks and how? Who is not getting access to nutrition or health care? Who has a set of disabilities that is making it hard for them to access services? Etc.

n What are the main challenges and obstacles related to health?

n What is the support you and others need?

n Who are some of the local people you are most inspired by?

n Who else should we talk to?

n How do we talk about this in a way that’s empowering and doesn’t turn people into subjects(objects) and applicants, ie leads to further marginalization?

n How do we best - in this context - engage families in a way that is generative and respectful of their story?

n What are some potential roadblocks we could face?

n What should we be aware of that we’re not?

n Would it be valuable for you to be part of a national gathering around a culture of health?

Who Did We Listen To and Where?

While the listening tour was not a comprehensive overview of the entire country, we did listen in a diversity of locations. And, while we don’t presume to know everything about the communities that we engaged with, but we did get a sense of what some of the challenges and bright spots are.

California

Arizona New Mexico Oklahoma West Virginia

Albuquerque

WestVirginia is a state blessed with the riches of a deeply interwoven community, and individuals who are hell-bent on making positive change. People are systems thinkers (and systems “doers”) working to transform entire communities, like the folks at Healthy in the Hills who are addressing the intersections of eating, physical exercise, community belonging, and income and employment. They are individuals who play different roles in their communities because they have to. They are individuals who love their state and want to tell positive stories to help shift the narrative of the current identity of the state. West Virginia is a state of incredible natural beauty - forest and rivers and mountains.

Albuquerque

Anthony

64 16-74 20% 80%

Since the founding of West Virginia in the 1860s, the economy has been based on coal mining. As coal begin to decline over the past 30 years, health and economic challenges have intensified, including obesity, diabetes, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary

Las

Race/Ethnicity: Mixed

Anthony

25 8-63 20% 80%

Race/Ethnicity: Mostly latino, indigenous and a few white

Disease. People are out of work. Substance abuse plagues West Virginian communities. On top of all of this, transportation is extremely difficult given the mountainous landscape making it hard to access the services that do exist, not to mention a job if there were one to be had. Broadband access is also extremely low. West Virginia is experiencing population decline, and many people who can are leaving the state. Communities are fragmenting, and families are broken. The economic identity of West Virginia is evolving, but it is not clear into what. Will it be tourism? Agriculture? Something else? New stories are being told, but the shame of “being number 1 on all the worst lists” is almost palpable.

7 5-75 15% 85%

40/60 African American and white 20 11-65 20% 80%

5 55-75 60% 40%

Race/Ethnicity: Mostly cherokee

Race/Ethnicity: Mostly native and white, 1 black

5 11-55 100%

20 14-65 30% 70% Vian

Race/Ethnicity: Black and native