9 minute read

en el corazón del imperio

Cusco y el origen de los caminos

in the heart of the empire Cusco and the origin of the trails

Advertisement

En las tradiciones orales cusqueñas, el proceso de expansión del Imperio se inició, a gran escala, con la intervención de un personaje particularmente significativo en la memoria de los incas: Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui. Su nombre, Pachacuti, apela a un pensamiento mítico de profunda significación asociado a los ciclos de la historia que finalizan dando origen a nuevas épocas. Pachacuti es un evento o un proceso en el cual el mundo y el orden cósmico se invierten, dan un “vuelco” o se transforman radicalmente.

La memoria de los incas recuerda con especial énfasis el papel que jugó este soberano y lo describe como quien, previamente a iniciar la gran expansión, diseñó o volvió a diseñar la arquitectura del mundo. Este Inca encarna al héroe civilizador, al modelo político ejemplar, al gran “ordenador”, y es además, el arquetipo de la divinidad solar. Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui se enfrentó o más bien “desplazó” a su padre, el Inca Viracocha, que representaba a la antigua divinidad creadora del mismo nombre. Volvió a fundar la ciudad del Cusco y la organizó en los cuatro suyus, inaugurando el ciclo mítico del Tawantinsuyu bajo el patrocinio de Inti, el dios solar. Este Inca dio inicio a un nuevo tiempo primordial relacionado con la organización política y administrativa del Estado, con su expansión y con la construcción de sus caminos.

According to the Inca oral tradition, the large-scale expansion of the empire began with the actions of a single person who figured prominently in the Inca collective memory: Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui. The name Pachacuti carries great significance in mysticism, referring to ending periods in history that give rise to new eras. Pachacuti is thus an event or process in which the world and the cosmic order are inverted, flipped, or radically transformed.

Inca oral history emphasized the role that this sovereign played, describing him as the one who, before the great expansion, designed or redesigned the architecture of the world. This Inca incarnated the hero of civilization, the exemplary politician, the great “regulator”, and is also the archetype of the Sun God. Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui confronted, or rather “displaced” his father, the Inca Viracocha, who represented the old creation divinity of the same name. He re-founded the city of Cusco and organized it into the four suyus; he initiated the mythical age of Tawantinsuyu under the aegis of Inti, the Sun God. He gave rise to new era of the political and administrative organization of the State, along with its expansion and the construction of its vast trail network.

Cuenta la tradición que Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui trazó nuevamente el diseño de la ciudad del Cusco. Mandó a hacer una maqueta de barro y luego convocó a todos los “principales” o autoridades y a los habitantes de la ciudad y les repartió sus tierras y viviendas. Días después, los principales del Cusco se reunieron y decidieron visitar al Inca y se sorprendieron al encontrarlo:

Legend has it that Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui laid out the new design for the city of Cusco. He commissioned a clay model and convened the “principals” or main authorities and the inhabitants of the city, and bestowed lands and homes upon them. Some days later the principals of Cusco met and decided to visit the Inca and were surprised to find him:

“…pintando y dibujando ciertos puentes y la manera que habían de tener y cómo habían de ser edificados; y así mismo dibujaba ciertos caminos que de un pueblo salían e iban a dar a aquellos puentes e ríos. Como esto fuese ajeno del entender de aquellos señores… le preguntaron ¿qué era aquello que así dibujaba? A los cuales respondió… ¿Qué es lo que me preguntais? Cuando sea tiempo yo os lo diré y mandaré que así se haga…

(Juan de Betanzos, 1551)

“… painting and drawing certain bridges and showing how they should look and how they were to be built; and he had also drawn certain trails that went out from a town to those bridges and rivers. As this was beyond the understanding of those gentlemen … they asked him what he was drawing. He answered them … “What is it that you ask me? When the time comes I shall tell you and send you to do it this way ...

(Juan de Betanzos, 1551)

El Inca diseñó la cartografía de los cuatro Suyus a través del trazado de los caminos del Inca.

Los caminos del Inca simbolizan la presencia del poder y la autoridad estatal hasta en los más remotos confines del Imperio; pero también, reflejan una forma de organizar culturalmente el espacio geográfico, el espacio social y la representación del orden cósmico. Así lo expresan las tradiciones orales sobre la ubicación, organización y orientación de los caminos. Los relatos sobre los cuatro grandes caminos que nacían del Cusco nos remiten, una vez más, a la cuatripartición simbólica del mundo.

Thus did the Incas map out the four suyus by tracing the Inca trails.

The Inca trails symbolize the presence of the state’s power and authority in even the most distant corners of the Empire; but they also reflect the Inca culture’s way of organizing geographical and social space and representing the cosmic order. This is expressed in the oral history of the location, organization, and orientation of the trails. The stories about the four great trails that originate in Cusco returns time and again to the symbolic division of the world into four.

Desde la plaza del Cusco, escribía el cronista Pedro Cieza de León en 1553:

The chronicler Pedro Cieza de León wrote from the plaza of Cusco in 1553:

“…salían cuatro caminos reales; en el que llamaban Chichasuyo se camina a las tierras de los llanos con toda la serranía, hasta las provincias de Quito y Pasto. Por el segundo camino, que nombran Condesuyo, entran las provincias que son subjetas a esta ciudad y a la de Arequipa. Por el tercero camino real, que tiene por nombre Andesuyo, se va a las provincias que caen en las faldas de los Andes y a algunos pueblos que están pasada la cordillera. En el último camino destos, que dicen Collasuyo, entran las provincias que llegan hasta Chile. De manera que, como en España los antiguos hacían división de toda ella por las provincias, así estos indios, para contar las que había en tierra tan grande, lo entendían por sus caminos... ”

“ there departed four royal trails: the one that was called Chichasuyo led to the land of the plains with all of the mountain ranges, all the way to the provinces of Quito and Pasto. By the second trail, which they called Condesuyo, one came to the provinces that are subject to this city and to Arequipa. By the third royal trail, which goes by the name of Andesuyo, one goes to the provinces that lie at the foot of the Andes and to some towns beyond the mountains. The last of these trails, which they call Collasuyo, goes to the provinces that extend to Chile. Thus, as the ancients in Spain divided everything up into provinces, here these Indians, in order to take account of everything that existed in this great land, made sense of them by their trails ”

Además de los relatos sobre los cuatro caminos del Cusco, destacan otras versiones que hablan de dos grandes caminos o arterias principales que recorrían longitudinalmente el territorio del Tawantinsuyu desde el sur de Colombia hasta el río Maule en Chile: el camino “de la Sierra”, que corría por el cordón montañoso de los Andes y el camino “de los Llanos”, por las tierras occidentales más bajas.

In addition to accounts of the four trails of Cusco, there are other notable versions that tell of two great trails or main arteries that ran the length of the territory of Tawantinsuyu from Southern Colombia to the Maule River in Chile: the trail “of the Mountains”, which ran along the Andes Mountains, and the trail “of the Plains”, passing through the western lowlands.

Si bien estas dos grandes arterias existían, el Qhapaq Ñan era en realidad una compleja red vial de variada importancia, funcionalidad y jerarquía. En ese contexto, el Cusco fue un eje de irradiación y de concentración de todo un sistema vial que integraba y comunicaba a las provincias, a sus centros administrativos y ceremoniales y a las zonas de producción de los diferentes pisos ecológicos. Desde el centro de la ciudad se distribuían los caminos del Inca hacia los cuatro suyus, como una verdadera columna vertebral de la organización del Imperio.

Los cronistas de los siglos XVI y XVII señalan la existencia de varios caminos, a los que atribuyeron diferentes autorías según los distintos perío-

Although these two great arteries did exist, the Qhapaq Ñan actually was a complex network of major and minor trails with different functions and levels of importance. Cusco was the center point from which this network of trails radiated, connecting with and articulating the ‘provinces’, their administrative and ceremonial centers and areas of production in different ecological zones. Indeed, the Inca trails led from the city’s centre towards the four suyus, forming the backbone of the Empire’s transportation system.

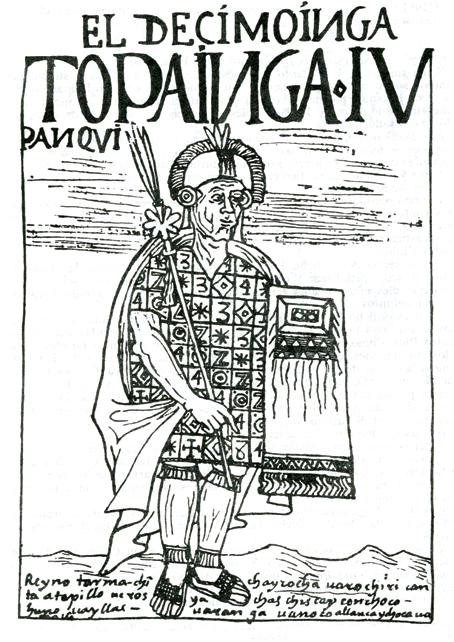

The chroniclers of the 16th and 17th centuries mention the existence of several trails, which they attributed to different builders at different times and under different rulers. For instance, they dos y gobernantes. Se reconocía, por ejemplo, un conjunto de caminos de la época de Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui y a otros de la de Tupac Inca. En el período español, el camino que más se utilizaba era el que se consideraba que había mandado a hacer Huayna Capac (padre de los incas Huascar y Atahualpa), que llegaba cerca del río Angasmayo en Colombia hasta algo más al sur de los valles centrales de Chile. En realidad, se trataba de un largo proceso de construcción, reparación y restauración cuyos principales artífices fueron Tupac Inca Yupanqui y Huayna Capac.

El Cusco y las cuatro partes del Imperio unidos por cuatro caminos. Esta ilustración de Martín de Murúa (1615), representa la mirada indígena sobre el orden del Tawantinsuyu, y sobre la organización cósmica del mundo andino. Con su centro en el Cusco, el espacio se divide en cuatro partes, las que a su vez se componen en dos pares de opuestos. Hacia el noreste (representado aquí en el extremo inferior izquierdo) el Chinchaysuyu. Su contrario, en el ángulo superior derecho es el Collasuyu. El Ande o Antisuyu y el Conde o Cuntisuyu representan los otros dos extremos orientados hacia el este y el oeste.

Cusco and the four sectors of the Empire, joined by the four routes. This 17th Century illustration represents the indigenous perspective on the ordering of Tawantinsuyu and on the cosmic organization of the Andean world. With its center at Cusco, space is divided into four parts, comprising two pairs of opposed sectors. To the northeast (shown here on the lower left) is Chinchaysuyu Its opposite, the upper right corner, is Collasuyu. Ande or Antisuyu and Conde or Cuntisuyu represent the other two extremes, oriented to the east and west.

Sin duda, existió un sistema vial mucho más complejo de lo que nos relatan las crónicas más tradicionales, que superó con creces el esquema simbólico de los cuatro suyus, comunicando y articulando, a través de una red de caminos recognized a number of trails from the period of Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui and others from the time of Tupac Inca. During the Spanish period the most widely used trail, which stretched from near the Angasmayo River in Colombia almost as far south as the central valleys of Chile, was thought to have been commissioned by Huayna Capac (father of Incas Huascar and Atahualpa). Actually, the trail network involved a long process of construction, repair, and restoration that was mainly undertaken during the rule of Tupac Inca Yupanqui and Huayna Capac.

A trail system of far greater complexity than that described by the most traditional chroniclers certainly existed, one that far surpassed the symbolic scheme of the four suyus and that connected and articulated all of Tawantinsuyu’s locales, transversales y longitudinales, a todos los pueblos que conformaban el Tawantinsuyu. Existen documentos y memorias de los caciques principales de la jurisdicción del Cusco que dan cuenta de esta intrincada red vial, describiendo un sinnúmero de rutas solo en un radio de 150 kilómetros. Cada uno de estos caminos, además, tenía un nombre propio con el que era identificado y frecuentemente se bifurcaba o ramificaba más de una vez en su trayecto. En la actualidad solo pueden identificarse algunos de los caminos troncales o principales en las cercanías del Cusco, como es el caso del camino del Cuntisuyu. settlements through a web of local transverse and longitudinal trails. Documents and reports from leading caciques in the Cusco district refer to this elaborate trail network, describing innumerable routes within a mere hundred-mile radius. Each of these trails had a name and often bifurcated or split more than once along its length. Today, only a few of the principal trails near Cusco can be identified, such as the trail of Cuntisuyu

El Qhapaq Ñan cumplía distintas funciones y sus caminos se trazaban, en ciertos casos, con objetivos específicos de tipo militar, administrativo o de comunicaciones. Pero aunque siempre revestía un carácter sagrado, existían ciertos caminos proyectados específicamente para recorridos rituales.

Aríbalo cusqueño, para el transporte y consumo de chicha (Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino).

Globular flask from Cusco, for transporting and consuming chicha (Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino).

The Qhapaq Ñan fulfilled different functions and its trails were sometimes laid out for more specific military, administrative, or communicative purposes. And although all of the trails were considered sacred, some were built specifically for ritual journeys.

En la ruta del camino ritual de Chacán en Sacsayhuaman se pueden apreciar, en el margen izquierdo del río, los muros y plataformas que formaban parte de este recinto construido desde la roca viva.