THE ART ISSUE

I DON’T EXACTLY RECALL WHEN I FELL IN LOVE WITH ART, BUT IT’S always been a part of my life. I grew up in a home filled with art books, paintings, and parents who insisted that I knew the difference between Monet and Manet by the time I was 12. When my family left the Soviet Union, we spent six months in Italy as we waited for our entry visas to Australia. It was a formative time, cementing my awe of art and artists. One glimpse inside St. Mark’s Basilica, one peek at the Sistine Chapel, one eyeful of the chiseled contours of David, and it was impossible to imagine a world where such things didn’t get created. Thankfully, we don’t have to.

As always, what you have in your hands is just a small sampling, a snapshot, of the many stories of art and artists in Indianapolis and its environs. Speaking of beyond, if you haven’t been to Fort Wayne recently, please make a point to journey there for a day of exploring their public art trail and profusion of murals.

AND NOW, TWO UPDATES FOR PATTERN FANS IN THE KNOW:

FIRST, YOU MAY NOTICE THAT THE COVER PRICE OF THE MAGAZINE HAS BEEN BUMPED TO $20. This hike reflects the increasing costs of…well, everything...but also reflects what we see as the mag’s mounting value to this city, state, and region. The good news is that if you subscribe, the price increase will have no bearing on you at all, as the price of an annual subscription will remain at $30. #winning

AND SECONDLY, WE’RE UPDATING THE MAGAZINE’S TAGLINE. OUR ORIGINAL TAGLINE, “FASHIONING A community,” was and remains central to our ethos of building an ecosystem of creatives. That said, over the past twelve years our community has continued to grow, and we found ourselves spending more and more time on helping creatives in all fields do what they do best—create! The new tagline “We help people create,” will serve as a reminder to all of us about why PATTERN exists.

I’M SO GRATEFUL FOR ANOTHER OPPORTUNITY TO CELEBRATE INDIANA’S ARTMAKING PEOPLE WITH ALL of you. My hope is that once you’ve perused this issue, you’ll be inspired to seek out the creative hotspots and allow yourself to be stoked by the myriad of styles and flavors of art available in Indianapolis and beyond.

THANKS FOR READING AND SUPPORTING!

P.O.

POLINA OSHEROV EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

BRAND PARTNERSHIPS

info@patternindy.com

DISTRIBUTION

Contact us at info@patternindy.com to stock PATTERN magazine.

Printed by Fineline Printing, Indianapolis, IN USA

PATTERN Magazine

ISSN 2326-6449

Proudly made in Indianapolis, Indiana

PATTERN DIGITAL

Managing Editors

Cory Cathcart

Katie Freeman

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Melanie Allen

Michael Ault

Alan Bacon

Isaac Bamgbose

Casey Cawthon

Michelle Griffith

Freddie Lockett

Lindsey Macyauski

NaShara Mitchell

Yemisi Sanni

Sara Savu

Micah Smith

Barry Wormser

Ace Yakey

SUBSCRIPTION

Visit patternindy.com/subscribe

Back issues, permissions, reprints info@patternindy.com

FASHIONING A COMMUNITY

EDITORIAL

Editor & Creative Director

Polina Osherov

Design Director Emeritus

Kathy Davis

Design Director

Lindsay Hadley

Managing Editors

Cory Cathcart

Katie Freeman

Editorial Intern

Destany Long

Copy Editor

Anne Laker

DESIGNERS

Carrie Kelb

John Ilang-Ilang

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Jennifer Wilson-Bibbs

Wil Foster

Kelsey Matthias

Jacob Moran

Polina Osherov

Andre Portee

Liam Rogers

Leo Soyfer

Jeanie Stehr

Brooke Taylor

Photography Intern

Cecil Mella

WRITERS

Milan Ball

Philip Barcio

Alexa Carr

Cory Cathcart

Anne Laker

Shauta Marsh

Richard McCoy

Polina Osherov

Liam Rogers

Adam Thies

Jenny Walton

Emily Wray

PATTERN IS GRATEFUL TO THE FOLLOWING FUNDERS AND PARTNERS FOR THEIR SUPPORT:

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 22

patternindy.com

EDITOR’S LETTER, 2 CONTRIBUTORS, 8

ART IS THE QUESTION WITH ARTUR SILVA AND SAMUEL LEVI JONES, 20

LONG LIVE FIRST FRIDAY, 24

MEET THE ARTISTS, 31

CASEY ROBERTS

TAYLOR SMITH

TOM DAY

JAY PARNELL

LYNDY BAZILE

BEATRIZ VASQUEZ

KEEP GOING TO 10 EAST, 50

Q+A JULIAN JONES, 58

FORT WAYNE OVERFLOW, 62

Q+A MARK BRASTER, 66

THE JUBILANT JOY OF JANAY, 78

NICKEL FOR YOUR THOUGHTS, 92

MEXICAN ART IN FLUX, 94

Q+A MÓYÒSÓRÈ MARTINS, 98

NASREEN KHAN, 102

ART IS THE QUESTION WITH WALTER LOBYN

HAMILTON AND DANICIA MONÉT MALONE, 106

BLOCKCHAIN OR IT DIDN’T HAPPEN, 110

I would paint giant, hyperrealistic murals on both sides of the OneAmerica Tower, recreating and restoring the view down Indiana Avenue through to Monument Circle that once existed in our city.

SARAH URIST GREEN is a curator and art educator seeking to demystify the worlds of art, artists, and museums for wide audiences. She is consulting producer of Ours Poetica, a YouTube series brought to you by the Poetry Foundation that captures the experience of holding a poem in your hands and listening as it’s read aloud. Green is also author of the book You Are an Artist, an outgrowth of the educational web series The Art Assignment, which Green developed in partnership with PBS. A former curator of contemporary art at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Green holds a bachelor of arts from Northwestern University and a master of arts in modern art history from Columbia University.

theartassignment.com

@theartassignment

I want a giant mural painted by Shadé Bell on one of the huge buildings downtown where everyone can see and experience it.

LEO SOYFER is a commercial portrait and fashion photographer, with a degree in Marketing from the University of Indianapolis. He has previously worked closely with PATTERN magazine, and has even printed his own small magazine, titled KPACOTA (krasoh-tah). In his free time, Leo enjoys playing piano and producing hip-hop music.

leosoyfer.com

l_soyfer

If I could paint a mural on a building, it would be a painting of influential photographers of the past. This is so that people will know the history of photographs and how vital it actually is inside and outside of the art world.

CECIL MELLA is a fashion and portrait photographer based in Chicago and is a past intern for PATTERN magazine. He has been studying and photographing for seven years. He is interested in photographing subjects in colorful backdrops and lighting to help outfits and models stand out.

cecilmella.com

cecilmellaphoto

I would choose to have a mural painted on the Salesforce building. With Salesforce being the tallest building in downtown Indianapolis, I think it would make a good statement by showing that Indianapolis is more creative than people may think.

DESTANY LONG is a freelance writer, born and raised in the heart of Indianapolis. Since she was a child, Destany has enjoyed bringing her vivid ideas to life through her writing. Her ideal career plan is to work for an online music publication writing stories about notable musicians. When she’s not glued to her laptop, you can most likely find her listening to music, hanging out with friends, and trying new local eateries.

desquisite

If I could paint a mural, it would be to restore the Roland Hobart mural on Delaware St, across from the City County Building that was originally created in 1973. If it were restored on the two walls it would easily be the best public artwork in the city.

RICHARD MCCOY is the founding Executive Director of Landmark Columbus Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to caring for, celebrating, and advancing the world-renown cultural heritage of Columbus, Indiana. He has a long history of creating unique solutions to complex cultural heritage challenges and occasionally writes about arts culture.

richardmccoy richardmccoy

I’d love to see a mural on The Pyramids. Such a largescale piece would be hard to miss, drawing much-needed attention to the arts on the north side!

KATIE FREEMAN is a Creative Fellow and Managing Editor at PATTERN. She can often be found in a state of overcaffeination, click-clacking away on her laptop and enjoying some variety of spicy snack.

notkatiefreeman

The mural I would choose would be of Gordon Parks the photographer. I would have it painted on a building in Fountain Square–the most visible building–not in an alley. Gordon captured the stories of social injustice through photojournalism.

JENNIFER WILSON-BIBBS of Life Through

Jenns Eyes Photography is a local Indiana photographer. She started photographing professionally in 2018 discovering that she had a passion for capturing her vision of what she sees through her eyes. She has photographed some amazing people and places throughout her journey. She has a way of bringing comfort to her photoshoots and bringing out the best in her subjects.

lifethroughjennseyes.com

lifethroughjennseyes

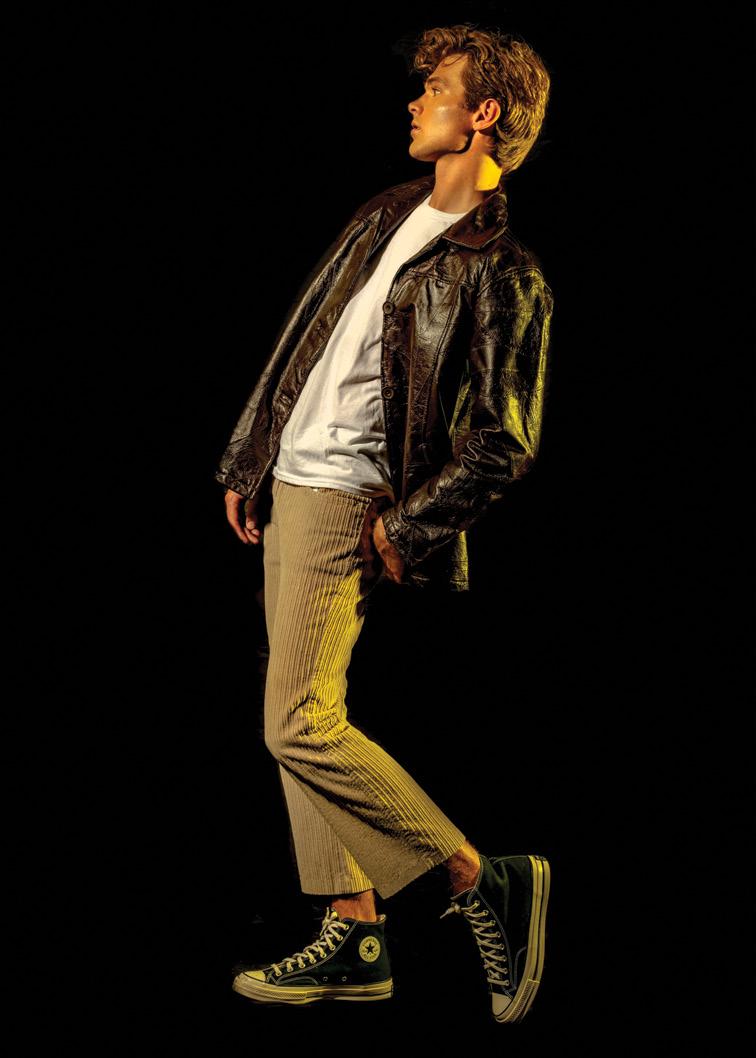

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEANIE STEHR

STYLE BY MACKIE SCHROETER

HAIR BY CAROLYN CINA

MAKEUP BY COREY CRYSLER

MODEL: ALYSSA L

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEANIE STEHR

STYLE BY MACKIE SCHROETER

HAIR BY CAROLYN CINA

MAKEUP BY COREY CRYSLER

MODEL: ALYSSA L

BLACK FAUX LEATHER COAT STAND STUDIO RHINESTONE FISHNET TIGHTS NASTY GAL BLACK PLATFORM HEELS ASOS DESIGN

BLACK FAUX LEATHER COAT STAND STUDIO RHINESTONE FISHNET TIGHTS NASTY GAL BLACK PLATFORM HEELS ASOS DESIGN

RED SEQUIN DRESS SOLACE LONDON BLACK PLATFORM HEELS ASOS DESIGN

RED SEQUIN DRESS SOLACE LONDON BLACK PLATFORM HEELS ASOS DESIGN

GREEN TRENCH COAT NASTY GAL BLACK KNEE HIGH BOOTS STYLIST OWNED

LONG SLEEVE GREEN DRESS ZARA

GREEN TRENCH COAT NASTY GAL BLACK KNEE HIGH BOOTS STYLIST OWNED

LONG SLEEVE GREEN DRESS ZARA

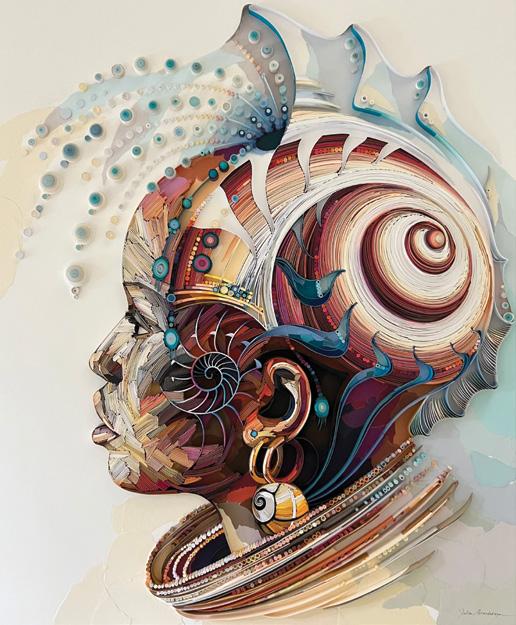

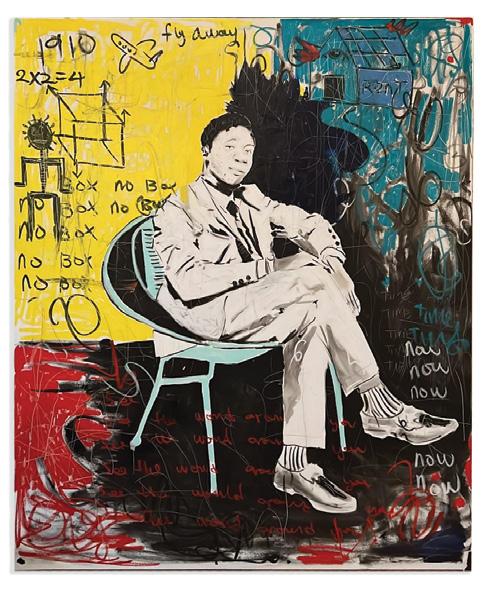

ARTISTS SAMUEL LEVI JONES AND ARTUR SILVA GO DEEP ON USING ART TO QUESTION ALL THINGS.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY POLINA OSHEROV

SAMUEL LEVI JONES is an Indianapolisbased multidisciplinary artist born and raised in Marion, Indiana. His work explores power structures and equality through deconstructing historical objects and using them to create his art. Jones specifically uses the pieces that expose flaws in history and what authorities have declared “truth.” He is currently preparing to exhibit at Galerie Lelong in New York and Paris and a residency in New York at Dieu Donné.

ARTUR SILVA: Hi! Great to see you. What’s new with you?

SAMUEL LEVI JONES: This past week, I started an artist residence at Indiana University in Bloomington. I’m going into it open-minded–not sure what I will create or research. One of the things that I’ve picked up on is that the departments are extremely siloed. An example is how the museum has an exhibition right now with a number of artworks by artists of color, yet the African Cultural Center, located next door, didn’t know about the programming and vice versa.

I'm wanting to have conversations about disrupting that, building larger community, and breaking down those walls.

AS: I’m one hundred percent with you. This vision in the art schools that programs are siloed. I think Bauhaus was way ahead of their time in the early part of the twentieth century thinking about a school that has no walls. An architect is also learning about film, and a painter is learning about music. We need that back.

SLJ: Yeah. I think a part of institutions is that they've been around so long that people tend to think everything must be okay, because if not, how do they still exist? Also, even if you are involved in something, there’s nothing wrong with being critical of it. It’s a job of the participants to be critical of that space in order for it to grow and expand.

AS: Absolutely. I think that the corporatization of education comes with all of that. This streamlined approach where you have to find more money constantly. And this hyper-reactionary approach to students’ concerns about what they're seeing and learning in school is to the detriment of the institution. We live in an era where we do everything to avoid discomfort. In this process, we reproduce inequality, we reproduce oppression by sweeping that under the rug and avoiding those conversations.

Art should be the complete opposite. Art should be a safe place to be uncomfortable, to be confused, to not know what's going on. Education has become about finding a job instead of seeking truth, and acquiring and transforming knowledge.

SLJ: Existence has deviated from the fullness of being human. We've lost sight of that. We’ve created this system of desensitization to what it means to be a well-rounded, grounded person. We have to get to a place where we’ve become fearless and are willing to take risks in order to change the system, so that it doesn't continue to spin out of control.

AS: It’s so complicated. If you think of art as a profession, then there's all sorts of traps that are bound to capture you. There's absolutely nothing wrong with people making a living off art. I have for fifteen years. You do too. But when that's the sole end goal, you miss opportunities to discover meaning within your own practice that can be truly transformative.

When Colin Powell went to pitch the war in Iraq to the United Nations, some folks from the media were bothered by a reproduction of Picasso's Guernica painting in the room. It's a powerful piece about the destruction of a city that was created during the civil war in Spain. The media covered the painting because it was not tasteful to be pitching a war while this work of art watches over. One that we now know was completely fraudulent. Art was there, bothering, in the middle of that. We little by little forget that, and we want to play with safe themes. I mean specifically in art schools where people are being trained, hopefully, to think critically about the world. It's lacking on that end. We ignore the importance of art in life and in the discovery of what it's like to be conscious and alive and have a beautiful, productive life. Art is in the center of that, of all of those questions. To me, art is a question mark.

“It’s a job of the participants to be critical of a space in order for it to grow and expand.”

ARTUR SILVA is a multidisciplinary artist as well. He focuses on different media such as installation art, video, sculpture, painting, and large-format printing. Silva grew up in Brazil, and has lived in Indianapolis for most of his adult life. Silva’s work centers around resistance to oppression, questioning everything, and using art to find the beauty in the human experience. One of Silva’s recent pieces, 136 Images from the Collection, is installed at the Indiana State Museum. He is currently working on a piece for Gainbridge Fieldhouse and prepping to be part of a show in Philadelphia in 2023 with four other artists.

SLJ: I agree. It's important to be open to question anything and everything, whether you're an artist or not. Things are nuanced. They're not binary. We treat things in a very binary way, it's either right or it's wrong.

You mentioned war; taking history classes and the way these conflicts were presented, everyone else was the enemy and everyone else was wrong. For a long time I never questioned that. But now I'm engaged with people who are willing to have that conversation. It's important that we try to stay true to that as much as possible. If we're in a place of residence as an artist, we're not there to play it safe. We're there to get people to think and to question. It's not so much that we're trying to upset people. It's not that at all. We’re trying to get people to think and exist in a way that's deeper, conscientiously, to create something better.

AS: I think curiosity is at the center of that. I was a curious child which landed me in rivers of trouble but the same curiosity that has brought me so much trouble has in some way liberated me. And if at any point in my journey I can share one piece of art with someone that will engage them in this journey of liberation. That's it, then I'm done, that's the work. Obviously these works don't exist in a vacuum. They exist in precious, long traditions of questioning that go back way before mass media existed. With subtleties, artists from the past—like Velázquez, Goya, and many others—have played with this questioning.

Through codified language and beautiful nuance, artists have questioned authority and hierarchies that preceded their existence but were impactful in their lives. I think that you do that brilliantly with your work. It's like we were talking before—the combination of materiality and the histories that material carries is beautiful. To see the way you do it, the way you compile these ideas and you index

them into complete thoughts—I find that amazing about your work.

SLJ: Thank you. How is it that you maintain the desire to question? I think a lot of people find it easy to give in, do what's expected, go with the flow and not go against the grain. Can you talk a little bit about the way in which you don't do that?

AS: My childhood was a preparation for all of this. I grew up in this incredibly strict cult; it was a doomsday cult. The end of the world was always coming next week, so why study? That was an actual thing that I heard. I had to acquire that desire to know more on my own. If I didn't do it I would just be absorbed by this group and be another mindless person in there. That, for me, was training on how to think, on how to seek the things that sometimes were uncomfortable discoveries.

Those in authority often don't know what the hell they're doing. These dynamics became an integral part of my work, of everything I think about in my research, no matter what the topic of the research might be. Behind it, there's always a relationship with a power dynamic of some kind.

Paulo Freire, a thinker from the 20th century. He said that education or knowledge comes with the transformation of information, and the very act of making art is transforming material and ideas into different formalizations and configurations. For me, this is where art is. It's seeking this transformation, and through the transformation is how you generate the possibility of affecting someone. As a child questioning everything was almost a matter of survival. There was one thing that none of those people could get to: my head. That's a sealed spot that only I have access to. I survived that. It continues to be part of my daily thinking about everything, including art.

“We live in an era where we do everything to avoid discomfort. In this process, we reproduce inequality, we reproduce oppression by sweeping that under the rug and avoiding those conversations.”

WORDS BY CORY CATHCART

PHOTOGRAPH BY CALEB JOHN SMITH

WORDS BY CORY CATHCART

PHOTOGRAPH BY CALEB JOHN SMITH

Like a lot of kids with divorced parents, I spent my childhood living in two totally different worlds. Life at my dad’s was your standard suburban setup. It was where I went to school, ran cross country, and made the majority of my friends. My mom, on the other hand, lived a more eccentric life in Indy. I would visit, and then report back to my suburban middle school friends about how weird her life was in the city. Oh, how I lied.

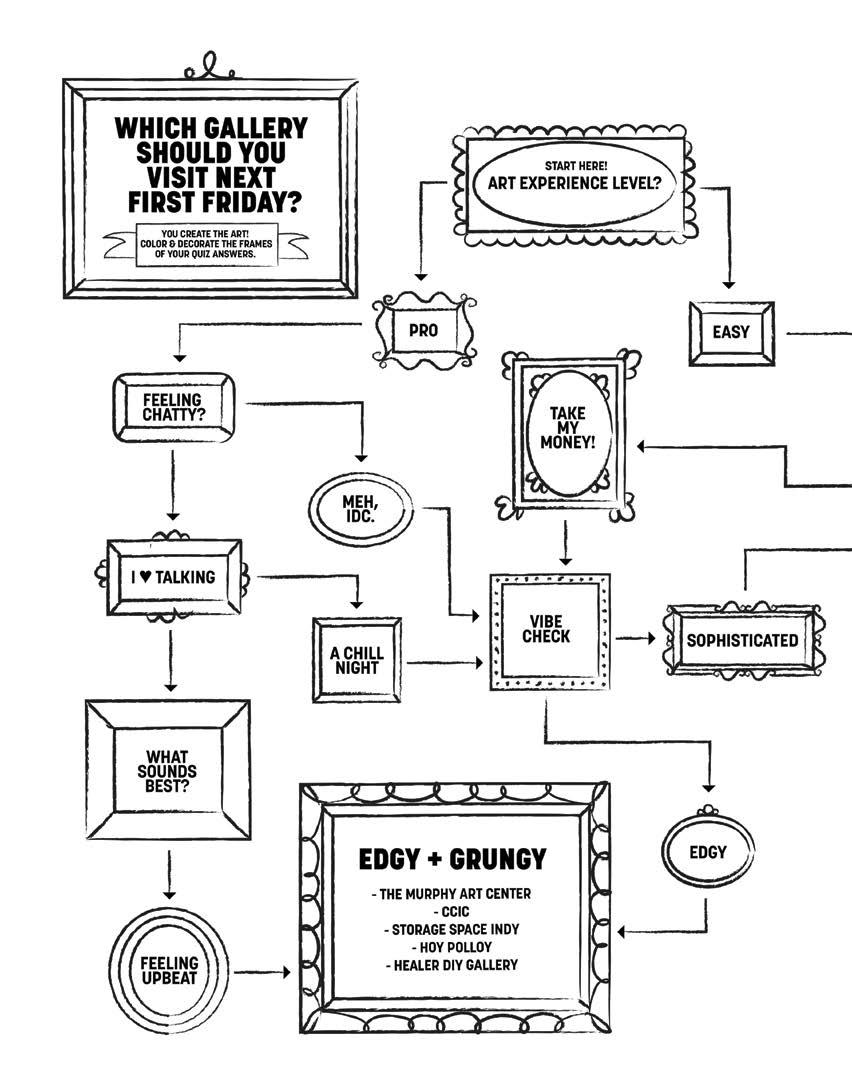

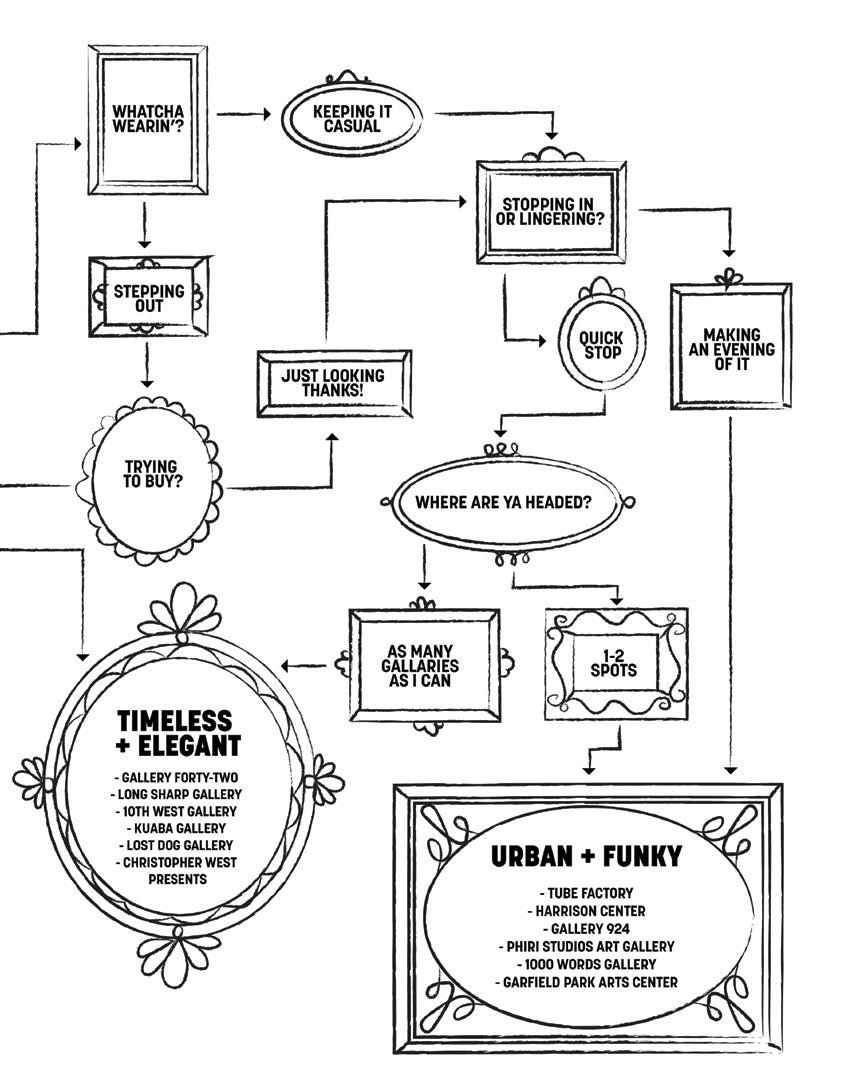

I loved how my mom lived, and these visits meant the world to me.

There was literally nothing better than cruising First Fridays with my mom. We’d saunter through the hallways of The Murphy Art Center and The Wheeler, and for me, it was like we’d walked into a movie. Music called from ’round the corner and each doorway opened into a new world of color and faces. These were my mom’s people. This was her life, and I was in awe of it.

Fast forward through my teens and early twenties, and we’re in the middle of a global pandemic. First Friday, an incredible creative and urban lifeblood, was now just another day on the calendar. The studio doors were locked. The stages were closed. The emptiness was unnerving.

I wondered if anyone else felt the loss of this longstanding community ritual the way I did, and I worried that it might not quite recover. One more beautiful thing ruined by COVID-19.

Obviously, I wasn’t the only one concerned about the comeback of First Fridays.

In the earliest days of the pandemic, the Arts Council of Indianapolis launched the #IndyKeepsCreating program and proceeded to distribute nearly $14M over the course of the next two years. These funds allowed artists and arts organizations to stay afloat despite the total shutdown of their primary revenue sources. These funds saved some of my favorite places and made it possible for some of my favorite people to stay here in Indy.

I can’t help but be overwhelmed with gratitude for the entire community coming together to ensure that the arts survived during those months. As a Creative Fellow at PATTERN, it’s possible I have a front-seat view of the show, but I know the impact has been made across Indy.

Now, First Fridays are most definitely back. And I’m experiencing a renewed appreciation for what they mean to me. Stepping into those halls again—this time in The Harrison Center and the Circle City Industrial Complex— my life feels a little like a movie set all over again. ✂

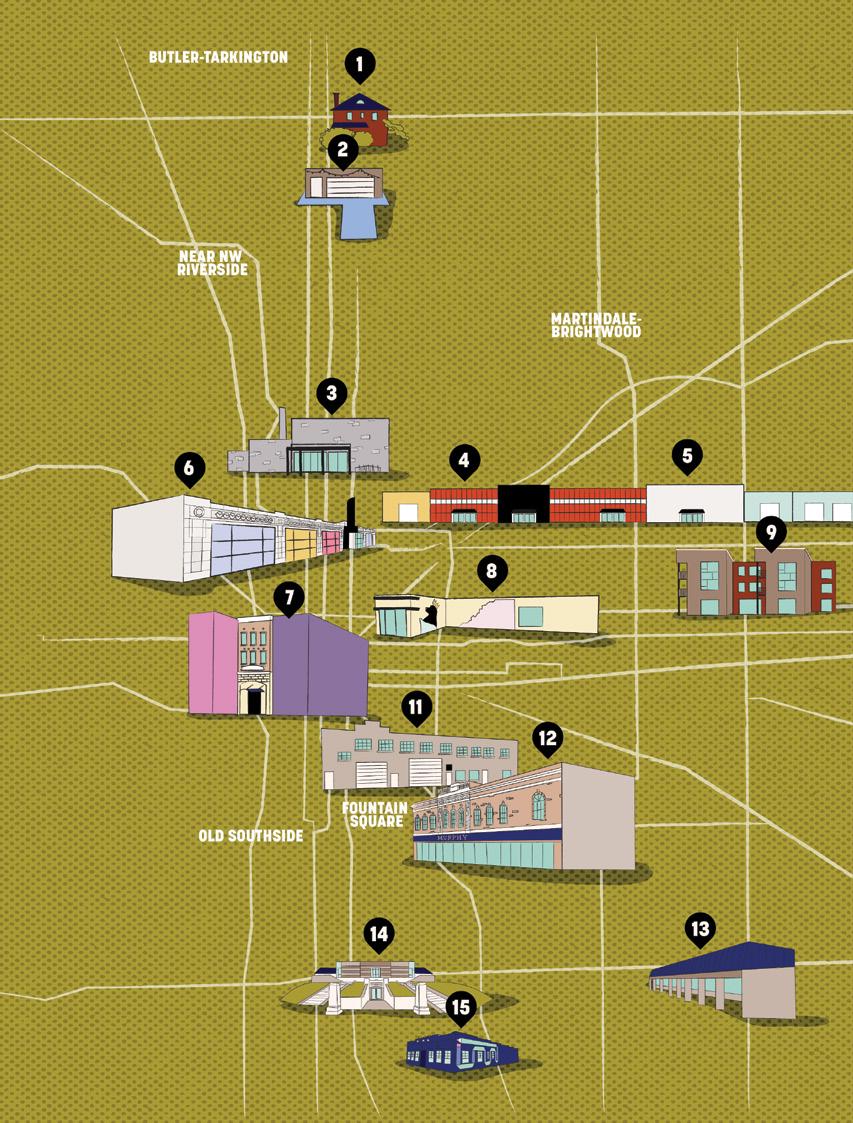

1. COMPANION 3715 N WASHINGTON BLVD.

2. STORAGE SPACE 121 E. 34TH ST.

3. HARRISON CENTER FOR THE ARTS 1505 N DELAWARE ST.

4. FULL CIRCLE NINE GALLERY 1125 E BROOKSIDE AVE. B21

5. CITY CIRCLE INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX 1125 E BROOKSIDE AVE.

6. GALLERY 924 924 N PENNSYLVANIA ST.

7. GALLERY FORTY-TWO 42 E WASHINGTON ST.

8. LOST DOG GALLERY 1040 E NEW YORK ST.

9. HOY POLLOY ART GALLERY 3125 E. 10TH ST. SUITE J + SUITE L

10. 1000 WORDS GALLERY 3328 E 10TH ST.

11. FOUNTAIN SQUARE CLAY CENTER 950 HOSBROOK ST.

12. MURPHY ARTS CENTER 1043 VIRGINIA AVE.

13. HEALER DIY 3631 E. RAYMOND ST.

14. GARFIELD PARK ARTS CENTER 2432 CONSERVATORY DR.

15. TUBE FACTORY/BIG CAR 1125 CRUFT ST.

Outdoor opera, a Black fine art fair, suffragette theater, Jerry Garcia’s guitar, Brahms’ piano, ghostly art, a “Send Nudes” art exhibition—and much, much more. Discover fun & unexpected things to do this season by visiting our curated calendar of events at Explore.IndyArts.org.

IN BOTH METROPOLITAN AND RURAL AREAS, INDIANA IS HOME TO A PLETHORA OF FULL-TIME ARTISTS. Their studios are here, they exhibit their work here, and they understand the ins-and-outs of the industry. Indiana isn’t well-known for its quality art scene despite funding, galleries, and artist communities existing. Getting to know the artists that live and work here, one-by-one, is how we can start to change the community and funding for the better. Six artists living and working in Indiana reveal their insight about the creative economy, what it feels like to work in their studios, and what art means to them.

WORDS BY CORY CATHCART

Cyanotype is a photographic printing process that was first discovered by astronomer, scientist, and botanist John Herschel in 1842. A year later, Anna Atkins first used the cyanotype process for photography development. Though cyanotype is known for its signature Prussian blue, the chemical process can be manipulated with other elements to produce different colors. Casey Roberts is an Indianapolis-based artist working out of Circle City Industrial Complex who has been creating visual art with cyanotype for more than twenty years. Through his experimentation with the process over the years, he’s found different ways to manipulate the process to make different colors, like yellows and greens, and designs in his work. He makes simple images that feel comforting and clever

CORY CATHCART: Tell me about your process of creating.

CASEY ROBERTS: It's called cyanotype. It's one of the very first photographic color processes. The photographic process only prints out blue. In later years, it was used as blue line drawings for architecture. That's a more modern use for it. I paint with the chemicals like a watercolor. I expose it to light and when I wash it out it turns blue. I get a blue and white image, and then I can alter the image with baking soda. Several different things, like peroxide, have an effect. There's a lot of different ways to use it. I've been doing this for twenty plus years. Over those years, I’ve figured out different ways to manipulate the blue to get different effects. The plants, the animals–they all get painted on top. The work you’re seeing here is really simple technique-wise. It’s very fortunate for me that like when the blue is altered, the colors that it changes to are complimentary. There are things that fall in line to help me as an artist and make for a pretty image.

CC : Nature is very prominent in your work. How does nature inspire you?

CR: Nature is more pure and simple than we are. A lot of my work is just an attempt to be quiet. I don't get out nearly as much as I'd love to. It's a shame really, but I do love national parks and hiking. I did an artists program at UNLV. I was there for a week and fell in love with the desert. As an Indiana kid, I’d never really been out there. I loved it. The quiet is so eerie. That hasn't quite creeped to my work yet.

CC: Is there someone who inspired you to begin cyanotype?

CR: I went to Herron here in town. I was a printmaker. At Herron, you have access to all these printmaking tools. It was amazing. But once you graduate, you're kind of stuck. Right as I was graduating–I was dating at the time and am married to now–my wife, who is a photographer, and she introduced me to cyanotype. She's an amazing photographer and does her own great work, but I saw the chemicals as a process which appealed to my printmaking brain. From there, it kicked off exploring this technique, this process. You see a lot of great cyanotype work out there. Each artist is gonna bring something different to it. If you would have asked me at the time, I don't think I would have said I'd still be doing it. I thought it was just a brief thing, but it really has developed into its own thing.

CC: You have a lot of records in your studio. How does music inspire you and when did you start collecting?

CR: I started collecting in college in the mid-nineties. Back then records were cheap. No one really wanted records. It really worked out. Now everything's so expensive. At the time, you could buy collectible records really cheap. I’d spend my rent money on vinyl. Over the years sometimes you get poor and you have to sell some of your collection. [I’ve] been through that. Now I try not to buy as much, but I do love it. It's very inspiring. It kind of works out, you put on a record and you've got about twenty to twentyfive minutes to work, and then you have to flip it. That little break is great while you're working on a piece, so the timing works out really well.

CC: What do you think Indianapolis is doing well for artists and what do you think they could do better?

CR: I appreciate PATTERN for approaching this topic. It's something I think a lot about actually. Indianapolis is a great town. It's got its problems; every town does. But there are so many creative people here. There are so many great artists and musicians; music has really taken off. Indianapolis musicians are fantastic. Things that can be better… I think we need a gallery scene. I think the people who buy art are here. I know, because they come to my First Friday. I know that people are hungry for good art, and Indianapolis has great art. I think making the connection could be better. The buyers have to do more work to find an artist they like. First Friday is great. I spend most of my First Friday just talking about the work, the process, and making connections.

CC: Do you have a favorite piece that you've made?

CR: I have to say that the beaver piece I did cracks me up. I like things with a little sense of humor. I'm here in my studio all by myself. And if I can crack myself up while I'm working on a piece of art, I feel like I've won. A lot of these paintings start out with asking, “Can I make that with my process?” If I can figure something out, that's what keeps me motivated. Sometimes I geek out on technical stuff, sometimes I like funny conceptual things, and when they can both meet together it makes me laugh. ✂

“I KNOW THAT PEOPLE ARE HUNGRY FOR GOOD ART, AND INDIANAPOLIS HAS GREAT ART. ”

Beatriz Vasquez is an activist and visual artist inspired by papel picado, a Mexican folkloric art that focuses on the manipulation of cut paper. Raised in Southern Texas, they moved to Indianapolis to attain a degree from Herron School of Art and Design. Since graduating in 2006, Vasquez has been a full-time artist and active member of Indianapolis’ creative scene, and has had work featured in exhibitions across the globe. The artist’s work often finds its basis in their Mexican-American heritage and current pressing social issues that disproportionately affect vulnerable communities.

my family’s home, but we’re treated like we don’t belong here. My creative process was born from my diaspora.

EW: What project are you most proud of, and why?

to teach me, but he wouldn’t, because I was a girl. His work was impeccable. I wonder what he would think of me now that I’m an artist. I hope that he’s watching me.

EW: What does “creativity” mean to you?

EMILY WRAY: Tell me about your process of creating.

BEATRIZ VASQUEZ: The paper is traditionally cut with chisels, nails, and hammers, but I create with an Exacto knife, and I barely ever illustrate prior to cutting. I want to let my mind and my experiences and my culture guide me through my creative process. I start cutting and then layer and layer and layer, if that’s what I want to do. My work is starting to move into sculptural form, and a lot of it is suspended and organic, very much full of storytelling. My art has to connect with people. My art has to tell a story. My art has to bring awareness to social issues, the things I faced growing up, the things my parents faced growing up. We’re still dealing with racism, with the language of “You’re not from here. You don’t speak English.” Well, I am from here! But we’re all also from somewhere else. When I’m cutting the paper, I feel like I’m cutting the negatives from my own life and filling them with color. Every day when I’m creating I’m tapping into my healing process. I’ve always wanted to be an artist, and I’ve always wanted to create something significantly culturally-based here in Indy, because it’s

BV: There’s so many! I was invited to do an exhibition with the United States Art in Embassies program. I’m super proud of that, because my art was exhibited for three years in Sierra Leone. It was in the American embassy and in the American ambassador’s home. Now, a second residency has come my way through them, with an ambassador from Lesotho! For me, it’s always been about putting my mom and dad’s name on the map. Everything that I do is in honor of my parents, of my ancestors, of all those people who came before me and saw more injustices than I will ever know. I’ll tell you about another project that’s equally important. My mother was a domestic worker for many years. She would say that when she put her uniform on, it was like an invisible cape. In 2020, I was invited by the California Domestic Workers Coalition in San Francisco to create something to put on t-shirts for people to wear when Governor Newsom signed a bill to protect the health and dignity of domestic workers. I created myself (because I look just like my mom) with a COVID mask that was a monarch butterfly. The monarch butterfly is very significant in Latinx and migrant communities, because they can fly where they want to, but people can’t. I made this, and they went out and made hundreds of t-shirts! I felt so empowered, and I felt like my art empowered those women.

EW: Who is an artist that initially made you want to create?

BV: The very first person that taught me to love art was my sister, Hilda. She started working for a grocery store in South Texas as the store artist. I had never heard of that before in my life! She taught me that art is very important and got me my first job. When I turned fifteen, I became the store’s artist in another location. Also, my grandfather. He was a master carpenter, and he taught all the young men in our family to be masters. I always begged him

BV: Creativity means healing. If you love it and it’s helping you heal from whatever trauma, even the smallest thing, that’s creativity. Growing up, my parents couldn’t ever afford a Barbie doll, but I learned to create them. I learned how to hand sew, to draw their faces and make them brown with black hair. Creativity brings me a lot of satisfaction, but I don’t care about how the work looks sometimes. I care more about the process. What incited my creativity? Was it a bad memory that I turned beautiful? Was it a good memory I turned into something more beautiful? Creation is embedded in all of our humanity. Every time I teach kids, I say, “Hello, fellow artists.” And they go, “Artists?” And I go, “Yes, you are!” We’re all artists, because we have something important to say. It’s a connection to culture, to memory, to ancestral homes and beliefs and the things we’re starting to lose.

EW: How does creativity and art impact the development of Indiana?

BV: I felt lonely in the art world here in Indianapolis for a long time. Only recently have people here in Indianapolis really started to connect with me. I feel that Indiana needs more culturally-based artists, because that enriches culture and diversity. It promotes beneficial humanity among everyone. I’m elevating my culture and saying this is what I have to offer. Indiana benefits from artists like me, artists of color that will tell their stories from wherever they are. There’s so much richness for these rural and urban communities. Indiana has come a long way, but coming from someone who has traveled around the world, it has a long way to go. We need to bring these communities into the art world and invite them diligently and purposefully. ✂

Lyndy Bazile is a local artist that’s all about inclusion. The feminine vibrancy that exudes through her numerous paintings puts emphasis on the strength and diversity of all women. Bazile’s art has been featured at festivals and art fairs in several states within the Midwest. Although her hometown is Fort Wayne, Indiana, her desire to connect with her Haitian ancestry is another big inspiration behind her artwork. From computer animation to largescale paintings, Bazile uses her craft to support and inspire marginalized groups and celebrate diversity.

DESTANY LONG: Tell me a bit about your background. When did you get into art and how did it lead you to where you are today?

LYNDY BAZILE: From a very young age, I enjoyed making art. In my early twenties, I taught myself how to animate with a tablet and I got a job in Massachusetts animating a web series with some comedians for a few years. That experience was a pivotal moment where I realized that I could do art as a career. After that job ended, I went to school and got my degree in animation and computer art. After I graduated in 2018, I started painting instead and never opened my computer. I started experimenting with paint and developing a studio practice. I've never taken a studio painting class, but I am a painter now.

DL: What project are you most proud of and why?

LB: I do lots of large-scale murals and smaller paintings. This piece that I did most recently for BUTTER is a mixture of the two. It's a very large scale; it's eight feet by eight feet, but it can also be broken down into smaller pieces and separated. This most recent piece is my proudest piece because it took a lot of deep diving into the history of Haiti, which is where my dad is from. A lot of my work circles around trying to connect with my Haitian ancestry and explore those roots. This piece was next level for me. I learned so much while doing it and so much came out of me intuitively that I didn't even know about Haiti. The whole concept of it being a larger piece but also able to exist in smaller fragments and being intended to do that felt like a big accomplishment for me.

DL: What does creativity mean to you?

LB: Creativity to me means making the conscious effort to try and think of new ways to be better, to make things better, or to envision a better future. It’s making a conscious effort to think about

those things in different ways and being able to manifest something that will help that vision come to fruition. Creativity for me has to be a positive thing—something that moves humanity forward in the right direction. If it's something that's bringing harm, I don't think that's creating. It’s destructive.

DL: What organizations or people have helped you financially as an artist?

LB: The first organization that made a huge difference for me was the Friends and Family Fund in Fort Wayne. I needed help, and they came at the perfect time. They were giving grants to creatives and entrepreneurs in the southeast side of Fort Wayne that the Board thought could use it. It was out of the blue for me. They found me and they wanted to support me. The grant was substantial and it really made a difference. I don’t think I could've continued in art at that time if I hadn't had that support. That was about two years ago.

Another one is the Community Foundation in Fort Wayne. They have supported me recently with a grant to help engage with my community and build out my studio. They are helping me to support the community through my art, which is what I really want to do. Not to mention GANGGANG making such a huge impact as far as creating value in the market and creating action and excitement around this thing that we all want to share in this culture. That's extremely valuable.

DL: How does creativity and art impact the development of Indiana?

LB: I hope that art can pave a way for people to get more politically involved in Indiana. Residents who have been pushed to the margins in many ways can be united by public art and work towards establishing a shared vision of what the future could look like for Hoosiers. ✂

"WITH MY ART, I HOPE TO CHANNEL NEW PERSPECTIVES, SUPPORT PEOPLE WITH SHARED IDENTITIES, AND EXPAND EMPATHY AMONGST OTHERS.”

Jay Parnell has been an accomplished member of Indiana’s creative community in different facets for decades. The selftaught narrative painter’s distinctive work in portraiture incorporates Christian iconography and historical elements with incredible precision, and has been showcased in collections across the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean. Though painting is his calling, Parnell’s family is his top priority, and he maintains a part-time position to support them in addition to his artistic pursuits. His experiences are a testament to both the need for and the unsteady nature of the Hoosier State’s creative economy, and the contemplative nature of his work is both haunting and captivating.

EMILY WRAY: Tell me a bit about your background.

JAY PARNELL: Well, long story short, I’ve always been an artist. My father was a visual artist, my mother was a poet, and my brother is a muralist. I’ve been painting and drawing my whole life. After I graduated from college, I had my first professional artistic job at Ball Corporation in Muncie, where I worked as a photographer and, later, an illustrator.

EW: What project are you most proud of, and why?

JP: I really enjoyed the last show I did at the Harrison Center, This Valley of Tears. It was a show of some of my best work, and I pulled it together over the course of six months.

EW: Tell me about your process of creating.

JP: I always try to be brainstorming. The process of creation is a perpetual thing. I’m always thinking about titles, reading essays and poems and listening to music, and looking for things that can help me in my journey. I may be inspired by a painting from another contemporary artist, or maybe even an abstract artwork or a fashion spread. Any number of things can spur my creativity. I’m a big concept person, and I always have an idea that I’m thinking about. I take my thoughts and put them down on paper, and then I start doing sketches, and then I allow myself to develop the sketches into drawings or a full composition to be transferred to a painting panel to begin my painting.

EW: How can Indianapolis become a place that is better suited for artists to live in?

JP: Indiana hasn’t been that good at developing the creative class. Unfortunately, that’s why most people in the creative class leave Indiana—I stayed because my primary goal in life is to build a loving family, and creating my work comes after that. I think we seriously lack a dedicated financial base. We do have a financial base—let me be clear on that—but it’s not large enough to sustain very many careers for artists in Indiana. I’m a tribute to this. I have a part time job, but I really love to paint, and I do a good job at it. If there was a larger base of

local collectors and sponsorships, that would help creators stay in Indiana. Not just foundations, but individual people coming in and saying, “Hey, I like what you’re doing, I want to support you on your project.”

EW: How does creativity and art impact the development of Indiana?

JP: We need to be talking to young people and helping them understand the value of art, because it’s a lifelong pursuit. It’s a lifestyle, and it’s foundational. All kids are artists when they start out, but they’re not taught to appreciate the creative process. By the time they’re adults, it’s about making money and doing other things. But creativity is important, because it’s about life. Artists say, “This is where we’ve been, this is what we do, this is who we are, and that’s why it’s important.” The artists, the writers, the dancers, the performers, the musicians—we are your signposts. When history looks back, they’ll be able to hear the music and see the artwork. Creating beauty is important because it is our conversation with the divine. And artists are the most responsible for creating beauty in this world. If we’re not creating beauty, what are we doing? That’s why it’s important to have our focus on the long game and not short, disposable solutions. ✂

"WE NEED TO BE TALKING TO YOUNG PEOPLE AND HELPING THEM UNDERSTAND THE VALUE OF ART, BECAUSE IT’S A LIFELONG PURSUIT. IT’S A LIFESTYLE, AND IT’S FOUNDATIONAL."

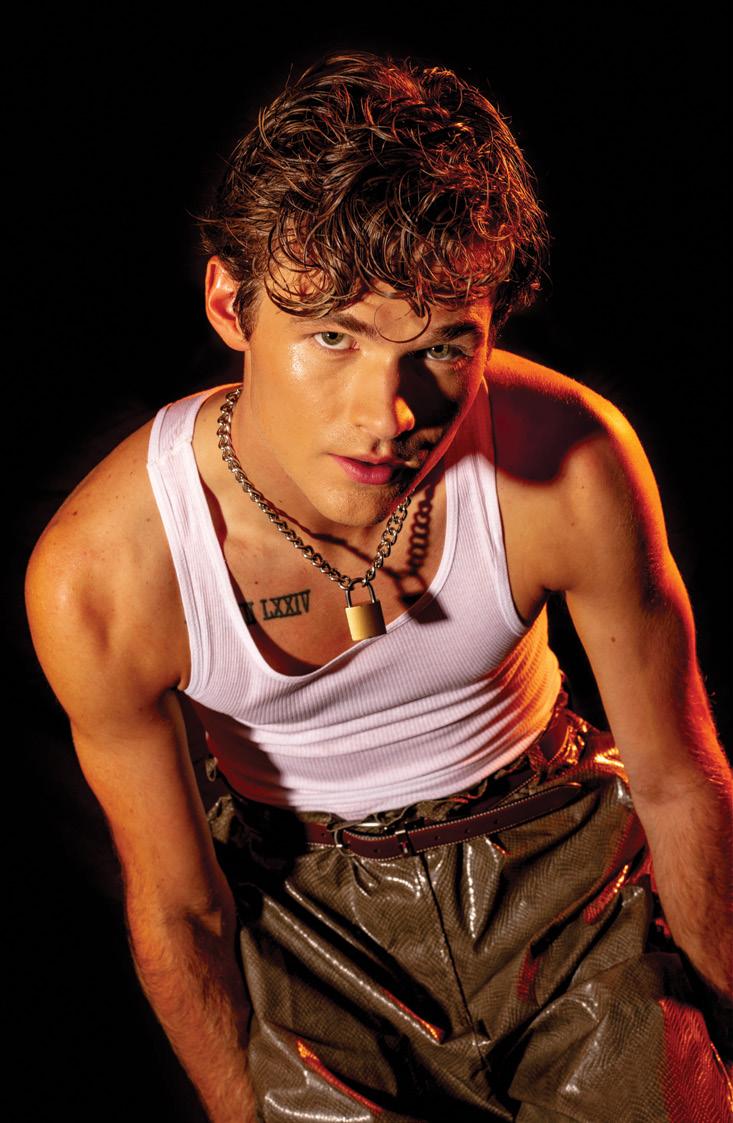

INTERVIEW BY KATIE FREEMAN

PORTRAIT BY LEO SOYFER

INTERVIEW BY KATIE FREEMAN

PORTRAIT BY LEO SOYFER

Indianapolis-based artist Tom Day has been creating art since he could hold a pencil, but what started out as a fascination for classroom cartoon doodles has evolved into a portfolio full of portraiture. His paintings and digital artworks spark conversations surrounding social justice, which he navigates through the lens of his own privileged perspective. Day feels as though he’s got a responsibility to use his spotlight to speak on things he sees as harmful, whether it’s politics, racism, or toxic Christianity. His most recent solo exhibition, “Condition,” largely centered around these themes and invited the viewer to question existing social structures and issues such as hostile architecture and price gouging.

These ideas of heavy artistic investment from larger corporations and other large grants give a sense of accessibility to consumers, artists, and creatives that are really important.

KF: Where is your studio and how would you describe its design?

TD: It's a studio apartment at the Harrison Center. It looks like a studio or a gallery space. I've got gallery lights in there and a big white brick wall. It's always been a balance to figure out how I can make it look approachable and accessible to the average art admirer while still finding a way to use it as my living space. I don't want anyone coming into my space to ever feel like they're intruding. Finding a way to disguise it as just a studio space is important to me, and over the course of the four years I've been at the Harrison, I've done a really good job.

KF: How does that impact your work-life balance between living and creating?

creating more spaces for artists is really important.

KF: Tell me about your process of creating. What does creativity mean to you?

TD: I grew up learning traditional mark-making, proportion, shading, and line. My parents signed me up for art lessons when I was in kindergarten with a local artist named Carol Conrad. That baseline propelled me forward and allowed me to explore that creative side and make work that is conceptually imaginative and visually representational. I wasn't constrained with trying to make sure everything was just right. Everything has come really naturally to me, and because of that groundwork, I work really quickly. I work very representationally and I owe a lot of that to who she was to me and a lot of other kids at the time.

KATIE FREEMAN: What project are you most proud of and why?

TOM DAY: As an individual piece, “Previously Known” was a groundbreaking work for me. It wasn't as representational as some of my other pieces. It was silhouetted, it wasn't a person, and that pushed my boundaries artistically and conceptually.

Collectively as a project, my solo exhibit “Condition” is something I'm really proud of. I put together work that again pushed those boundaries for me artistically and conceptually but also invited other people into what's going on in my brain and what I'm passionate about. I hung the show, looked around, and thought “I haven't had that gratification or sense of pride in my work in quite a long time.”

KF: How can Indianapolis become a place that is better suited for artists to live in?

TD: The biggest thing right now is accessibility. We're on our way with the second annual BUTTER Art Fair and what that has spurred in the Stutz Building: a sense of investment and revitalization of something that was once amazing and is on track to be that again.

TD: It's tough. That's why I have such a hyperfixation on working outside of my space. I'll go to different coffee shops or spaces where I feel comfortable to be away from where I sleep in order to create this newer environment and sense of inspiration. I do a lot of finishing touches or any larger-format hardware projects in my studio space. But ultimately, I like to go out and work using digital mediums, like working on my iPad. It has a special place in my heart because I'm not confined to just working with traditional media at that point. I can do just about anything—not that you can't use traditional media outside of your studio space—but this allows me to take my art wherever I go. I'm super grateful for that.

KF: What do you think our current art gallery situation is like? Do we need more visibility for them or more galleries in general?

TD: I would always advocate for more gallery spaces. I think those innately attract more people and allow space for community. There are a lot of bigger “powerhouses” in the artistic community in Indianapolis but there are smaller galleries popping up that have done an incredible job. Justin Vining opened up his own gallery space, Vining Gallery on 10th Street, and it is incredible. There's a sense of modernity that comes from that sort of space. People are oftentimes seeking a space that's new. We're always looking for something fresh. I don’t think it’s one or the other. Having more visibility for artists and

Creativity is allowing yourself and your authenticity to enter spaces not previously imagined by the outside world or by others. While it can be inventive, it’s also heavily rooted in the creator itself. That's what's so beautiful about art, being able to use your talent and passion to say something you're thinking that others might not be thinking, or use your voice to have others create these ideas in their head.

KF: How does creativity and art impact the development of Indiana?

TD: There's a lot of money that comes from art. We just saw that with BUTTER 2. We're seeing communities that have been brushed to the side for so long coming into the spotlight. As a pretty progressive city, a lot of people are loving that and wanting to participate in that revitalization. This access to Black art and culture has created a whole new spotlight on what we can do in the city to make everything more equitable. That's what the power of art can do.

I'm learning about all these communities that have been completely destroyed in our time. I learned about IUPUI and how it completely obliterated Black communities through its construction and its implementation. It is important to not only recognize and be mindful of that, but take action to see a more beautiful future. BUTTER is the best example of that right now in Indianapolis. It's one of the coolest artistic fairs that I've ever experienced, especially in the Midwest. Having that collective passion and community is something that I want to see across the board in Indianapolis. ✂

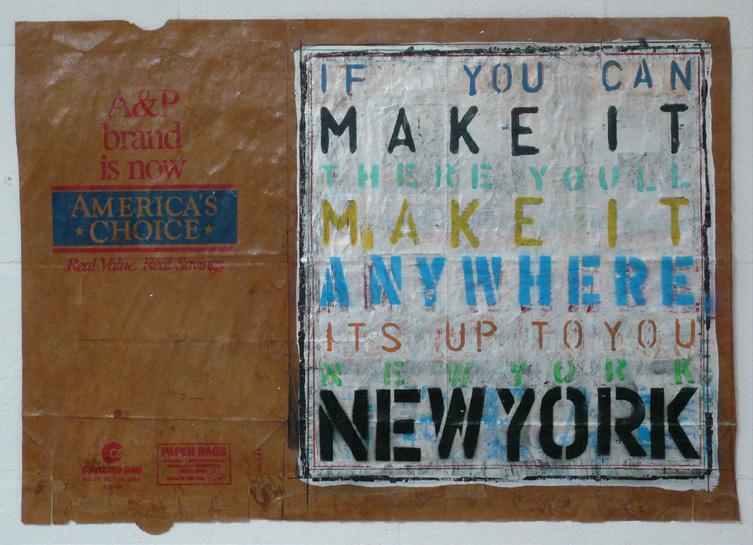

On the third floor of the labyrinthine Stutz Building, Taylor Smith is re-interpreting the pop art she grew up with in the seventies. Her work incorporates unique mediums like silk screen frames and spray-painted floppy discs to create funky, colorful visual art pieces. Mickey Mouse, Marilyn Monroe, and Abraham Lincoln are just a few examples of the famous figures featured in Smith’s artwork, which combines oil paints and screen printing to focus on themes of nostalgia and consumerism. Society’s fascination with fame, wealth, and tragedy is communicated through Smith’s works, which have been featured across North America, in Europe, and in high-profile collections.

KATIE FREEMAN: You’ve had a studio in the Stutz Building for fifteen years. How would you describe your space?

TAYLOR SMITH: When we used to have open-house studios, everybody would come in here and say “This is the most comfortable, coolest studio.” I have some carpets here and there, I painted my walls black, I always have music going, and the lighting is right. When I moved in here, this was just a white box. The floor was white and I painted it to look like an old factory floor, like the rest of the building. I painted all the columns and I scraped all the paint off the brick walls to make it look aged. I put two weeks of work into this before I moved in. It's extremely personal to me. I want the right vibe if I'm going to be in a space that makes me feel creative.

KF: Who is an artist that initially made you want to create?

TS: I would say Warhol was probably one of my biggest influences. This summer I was asked by the Cleve Carney Museum of Art up in Chicago to be in a show and lend a couple of my works that were influenced by Warhol. They hung them directly next to the original Andy Warhols in their collection. They had a dialogue between Warhol’s paintings and mine, and they’re acquiring one of my pieces for their permanent collection now. That was a big honor for me, having my work intentionally compared to his.

KF: Tell me about your process of creating. What does creativity mean to you?

TS: A lot of my ideas are from things I see every day in media and things in the back of my mind from my education studying art history. Whether it's Renaissance painters or pop artists or abstract expressionists, I try to blend a lot of what I've learned into my work because it's familiar. It's good for a reason, and I use that as a stepladder to stand on and keep going. I will originally come up with an idea I want to incorporate, sketch things out, and then translate that into a final work. I use a combination of screen printing, drawing with pencil, and painting for that.

To me, creativity means the freedom to be able to interpret what you see and express yourself. I love working for myself. Every day I can wake up and decide “I want to do this,” and hope that it works— but you don't know. That's part of the creative process. It's experimentation. When it pays off, it's very rewarding.

KF: Are there any organizations or people that have helped you financially as an artist?

TS: The Arts Council and the Lilly Endowment. I've had a few really nice fellowships and grants there and that's been very helpful. The Lilly Endowment and Eli Lilly have purchased and collected my work.

KF: How does creativity and art impact the development of Indiana?

TS: The more a city has a really strong creative foundation, whether it's visual arts or music or performance arts, corporations are attracted to that as quality of life. Honestly, the quality of life has gone down a bit with the local government cutting funding for the arts. That really hurts. It affects companies like Salesforce and Lilly, and they don't want to have people in a city that doesn't have a flourishing creative scene.

KF: How can Indianapolis become better suited for artists to live in?

TS: With the Stutz Building being under construction, a lot of artists have had to move out. I've been looking around to see what is available in the city, and this city needs more affordable and beautiful studio space, not like an office with popcorn ceiling. I'm talking about really cool buildings that are—instead of being turned into offices—more like a creative loft-type space. But in general, the art scene is great. There's hardly any galleries anymore. That's kind of depressing, but I don't know that the business model really works. That's why they're not here.✂

"TO ME, CREATIVITY MEANS THE FREEDOM TO BE ABLE TO INTERPRET WHAT YOU SEE AND EXPRESS YOURSELF. I LOVE WORKING FOR MYSELF."

WHETHER OR NOT WE ARE AWARE, ART IS PRESENT in nearly every choice we make. Design, color, and composition influence our daily experiences. A few years ago, I learned the importance of judging an album by its cover. The artwork of an album influences who buys it and why. The first thing you notice about a record is what it looks like–some catch your eye, some don’t.

The same could be said for a cocktail. The food and drink industry is a place where art is present and is a determiner of how successful the business is. Indianapolis is home to chefs, and bartenders, who make our dining experiences photo-worthy. We asked five local bartenders to combine the artistic appeal of fancy cocktails with the nuanced influence of album artwork, and the era-defining music inside.

WORDS BY CORY CATHCART PHOTOGRAPHY BY BROOKE TAYLOR RECORDS SELECTED& PROVIDED BY SQUARE

CAT VINYL

BY ELTON JOHN

+

BY ELTON JOHN

+

1.5oz Hi & Mighty Big Fuss gin

.75oz Giffard pamplemousse liqueur

.75oz champagne/corn cob simple syrup

1 egg white

.5oz lemon juice

Pink Himalayan sea salt and dill garnish

“My tribute to Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is a riff on a gin fizz. I chose the ingredients based on the palette of the album art. The champagne and corn cob simple syrup really sums up the theme of the album. Sir Elton sings how he’s tired of the big lights, glitz, fame, and fortune associated with his celebrity life, and how he’d likely be more fulfilled by a modest, peaceful life back on the family farm.”

-JAKE JOHNSON

2oz Hotel Tango ‘Shmallow toasted marshmallow bourbon

1oz fresh pineapple juice

.75oz fresh lime juice

.5oz chipotle-cinnamon syrup

Rainbow ice cubes

Dragon fruit aquafaba foam

“The bright colors in this cocktail are heavily inspired by the album artwork. I really enjoyed the funky jazz fusion journey the music took me on, so I wanted to create a flavor to match the energy: a little spicy, a little smokey, a little sweet. The colors combined with the exciting palate led me to name this cocktail Funky Fusion.”

-HOLLEH MATLOCK

BY PRINCE AND THE REVOLUTION

BY PRINCE AND THE REVOLUTION

1.5oz St. George raspberry brandy

.5oz dry orange curaçao

.25oz lemon juice

Topped with prosecco and dry shaken beet aquafaba

“I decided to go with a lighter spritz riff. The incorporation of the beet aquafaba creates a Purple Rain situation as it cascades through the ice. I found this quote that brought me to the purple froth garnish that really brings home the cocktail for me. Prince explained the meaning of Purple Rain as follows, ‘Purple rain pertains to the end of the world, and being with the one you love and letting your faith or god guide you through the purple rain.’”

-MARCUS SWAFFORD +1.5oz mezcal

.75oz lemon

.5oz strawberry-infused Montenegro

.50z agave

.25oz strawberry sage balsamic shrub

4 dashes of chocolate bitters

3 dashes of saline

1 egg white

BY THE ROLLING STONES

+

BY THE ROLLING STONES

+

“My cocktail was inspired by the album cover. I took reference from the cake. I wanted to make something fruity and incorporate egg white as a nod to the icing on the cake. I used a levitation device to display the cocktail in reference to the cake stand. The Rolling Stones were known for their tequila sunrises, so that helped me pick out my spirit. Mezcal has gained popularity in recent years, and I really enjoy the smoked quality from it.”

BY COREY EWING FOR STRANGEBIRD @STRANGEBIRDINDY

BY COREY EWING FOR STRANGEBIRD @STRANGEBIRDINDY

3 drops of 20% saline solution

3 dashes Black Walnut Bitters

1oz Averna

2oz Appleton 12 year

“I put a twist on this cocktail for Billie Holiday’s album, Stay With Me, not only for its name, but for its vibe of comfort and joy. The album was recorded in the early years of the Civil Rights Movement and released only the year before The Federal Bureau of Narcotics targeted her, hastening her death in New York City. It was her calm before the storm. As a final nod, Appleton Rum is blended by Joy Spence, the first woman to become a Master Blender in the spirits industry.”

-COREY EWING

KEEP GOING EAST ON 10TH STREET. Past Bottleworks District with its lusciously-restored white tile and gold lettering naming each of the tenants in the $300 million development. Keep going east, past the spot where the Monon Trail and the Indianapolis Cultural trail connect, underneath the torn-up interstate bridges, past the Circle City Industrial Complex where many artists and entrepreneurs are incubating inside that cavernous space.

Keep going. That is not the end of the interesting parts of Downtown Indianapolis.

Arrive at the corner of 10th and Jefferson, which is probably the start of 10 East Arts. But there’s no need to get so specific here—you can say it starts where you want it to.

10 East is just as much a place as it is an attitude, a state of mind, maybe even a vibe. It’s for you to visit, or not. It’s an area made for and by its residents. You are welcome here, but you’re not likely to see a citywide marketing campaign for this district that bridges Downtown to the east side of the city.

This is a place where residents and entrepreneurs are placing multi-hundred and multi-thousand dollar bets. A place where the arts and cultural experiences are authentic centerpieces of a community redevelopment strategy. This is a place where you can see people personally investing in their futures.

Such as The Mad Griddle at 2127 East 10th Street, a restaurant that Amanda and Tim Jones opened in September 2021 with about $100,000 from their own savings. They remodeled an old nightclub into a place that has its own style, a “mad” one, and they each work in the restaurant—Tim in the kitchen and Amanda out on the floor, offering up Sunday morning live jazz brunches, pizzas with names like “Overweight Lover,” and Mad Wine Slushies.

Next door, there’s Rabble Coffee Shop with its dark brews and vegan pastries. (The side of their building once bore a mural by the famous Louisiana-based artist Muck Rock, but the community quickly tired of it and painted over it with a kind of gallery of murals, each made by residents). Go into the bodega Dear Mom and check out the small-run art publications, the kombucha in the cooler, the mix tapes, local produce, clothes, and whatever surprises are on hand that day.

Keep going. It’s all here: Burger King, Clark Gas Station, apartments, boarded-up storefronts, motorcycle parts, an old gas station transformed into something called Re:Public. Yes! The pop-up art space at 2301 E. 10th Street is managed by the John Boner Neighborhood Centers. It’s a venue you can rent for a half day, full day, or up to five days, at cheap AirBnB rates ($75 - $150 a day). The only requirement is that you have to do something “creative” there. According to Joanna Nixon, an independent arts administrator and leading 10 East dreamer, the venue has been rented more than 75 times for arts and culture events already in 2022.

Churches, appliance stores, houses and for sale signs foreshadowing change, residents greeting you from their porches, Wednesday night Karaoke at the Tick Tock Tavern, Vining Gallery (home to Justin Vining’s signature landscapes and paintings), a watch repair shop, and what was for a short while the home of the Israelite School of Universal Practical Knowledge.

Look it all up. And keep looking, because this area is ever-changing.

There’s a new taproom, the 18th Street Brewery, near the corner of Rural and 10th. What Indy hipster is coming out to 10 East Arts to drink beer here? The owner of the brewery, Drew Fox, is betting on building a new community here around beer and food. If Upland has created a community of dads riding bikes and drinking beers at 49th and College, then of course there’s a community of beer enthusiasts at this corner. It’s just different.

More gas stations, boarded-up buildings, liquor stores, the old Rivoli Theater, more churches, Tim and Julie’s Another Fine Mess (an architectural salvage joint) and the Teeny Statue of Liberty Museum, another Muck Rock mural, barber shop, the well-hidden Cat Head Press. Look it all up and check it out.

Now arrive at the 10 East Arts Hub … a new place, a centerpiece, a community arts space. The Boner Center owns and renovated the building, which was a 1920s ice cream shop and in the early 2000s, a coin laundromat. The aforementioned Nixon oversaw its renovation which was supported by a special grant from Lilly Endowment Inc. This grant allows, among other things, the Boner to program the space and occasionally rent it out for a fee. It’s used all the time: by emerging musicians playing jazz, hip hop, R & B. Or young artists experimenting with different ideas from fashion to painting, or whatever gallery show someone can dream up and trot out. Advocacy, community discussions, the film “Iron Giant” playing in the little park next door. Kids dancing.

The 10 East experiment begs questions and dangles answers. What does it look like to have a community that has places for young creatives to show and sell their work? What does it look like for a community to create its own type of events? What does it look like to have art for and by a community that calls this place home?

"THE 10 EAST EXPERIMENT BEGS QUESTIONS AND DANGLES ANSWERS. WHAT DOES IT LOOK LIKE TO HAVE A COMMUNITY THAT HAS PLACES FOR YOUNG CREATIVES TO SHOW AND SELL THEIR WORK?"

ARTS + CULTURE

10 East Arts HUB

1000 Words Gallery

Beyond Barcodes Bookstore

Cat Head Press

Guide and Anchor

Hoy Polloy Gallery

Re:Public Pop-up artspace

Streetly

Vining Gallery

INDEPENDENT RESTAURANTS

10th Street Dinner

18th Street Brewery

Beholder

Chucks Coney Island

Gomez BBQ

MayFair Taproom

Rabble Coffee

Sidedoor Bagel

The Mad Griddle

Tick Tock Lounge

RETAIL

Audrey’s Place Thrift Store

Dear Mom

Tim and Julie’s Another Fine Mess

Come look. I’m sure you can find someone who could put a dollars-and-cents return-on-investment number to this, to tell the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce-ish story of economic development impacts. But. With only that, you may not see what value is being created here. You may not see that this is just getting started. This is all just a shot, a trial, a chance to see something become itself.

Keep going east. Get lost in Audrey’s Place and find the lamp you probably don’t need, but should buy. Have a vegan reuben and a cold beer at the 10th Street Diner. Stop in to Guide and Anchor to get your new venture branded, check out 1000 Words Gallery, or look next door into Streetly and grab some of Gordo’s fresh streetwear at his first brick-and-mortar store. Stop at Beyond Barcodes Bookstore, and read everything on Barack Obama’s Summer Reading List, even this winter.

All of these words: it’s interesting. Don’t mess this up, keep going. ✂

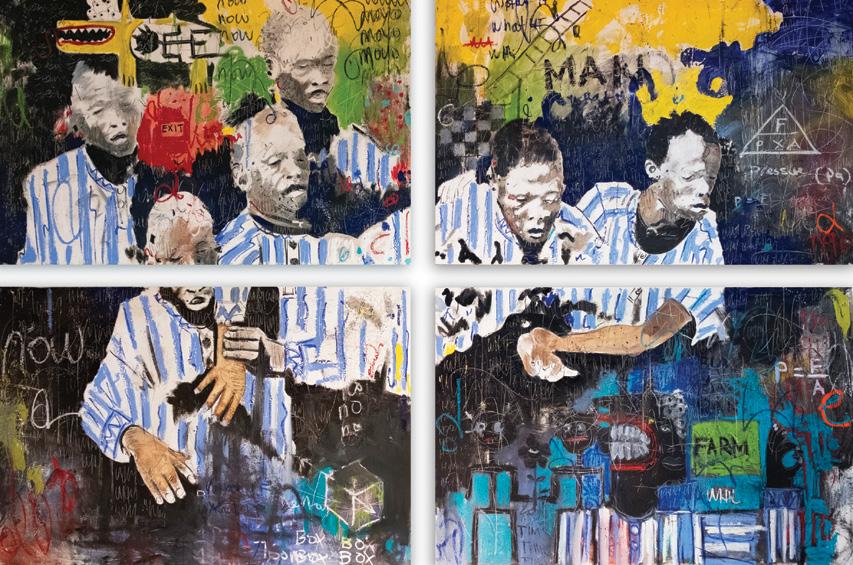

Julian Jamal Jones is an interdisciplinary artist born and raised in Indianapolis. After specializing in fashion photography for nearly five years, Jones switched gears while receiving his MFA at Cranbrook Academy of Art. Though his MFA was in photography, Jones gravitated towards fabric and textile art and began creating quilts based on corresponding oil pastel sketches. Together his drawings, textiles, and sculptures are used to contextualize Jones’ Black identity and memorialize Black culture. Whether he’s coding language through the use of abstraction or opening up a conversation on his Black experience via sketches, art serves as his most direct form of communication. This past September, Jones took his talents to Detroit to display his solo exhibition, “MARKINGS.” Before heading up to the show, he sat down with PATTERN to talk all things art.

KATIE FREEMAN: You’ve shifted focus from fashion photography to create textile art. Tell me about this new medium.

JULIAN JAMAL JONES: With my fashion background, I still have inspiration from fashion and construction. It’s more about my Black identity in America and where I belong. It also connects to my family history as well. My grandmother quilted and my great-grandmother quilted. It’s like a clash of all our inspirations and family roots. It’s rewriting what a quilt can be. It can be functional, it can be nonfunctional, it could be a fine art piece, it could be something that you cuddle with in bed. I’m trying to break that boundary.

KF: Your work incorporates both oil pastels and textiles as mediums. What originally drew you to those art forms?

JJJ: I’ve always liked art. I think I was born to be an artist. Working in abstraction is one thing that I really capitalize on. It’s not literal; it’s open to interpretation. I’m not forcing a narrative. So it’s like I’m drawing in code and symbols, coding language. I might know what the work is about, but the audience might not know. It’s for me to be open-ended and do what I want to do without being judged. I make sketches, and then turn them into textiles. It’s a two-step process for me. What attracts me to drawing is the beauty behind it.

KF: Your solo exhibition “MARKINGS” uses both those art forms. How do they come together to express your experience as a Black artist?

JJJ: A lot of my work starts off with music as inspiration: hip hop culture, jazz, even gospel. I listen to all forms of music. My dad was a big jazz person, so I remember listening to jazz music in the car. He was a DJ as well, so I was always surrounded by different forms of music as a child. That body of work is like a continuation of what I’m doing.

The work is darker, it’s heavier, but in a way, it’s more open to who I am as a person now versus my previous work. This work was more heavily influenced by music. You can tell by looking at the textiles. They’re more freehanded. The quilts have a black base, so it’s a black background with vivid colors on it. That’s the first time I’ve ever explored the color black within my work. Black can open so many doors into what black means. You can take black as a new discovery, depression, darkness or an exploration.

KF: As a recent graduate from Cranbrook Academy of Art, how has receiving an MFA in photography impacted the way you create art?

JJJ: I’m more critical. I feel more comfortable opening up now. I feel more confident as an artist. The MFA has really helped me to explain my work and think through my process. I can ask myself, “Does this make sense? Does this not make sense?” Having an MFA has opened many doors. I’ve met a lot of curators and collectors, which is huge. You want people to buy your work!

KF: Craft, composition, color theory, textile design— these elements all play into your artistic process. Are any of those most important to you, and why?

JJJ: Composition is big for anything. It’s big for photographers, painters, textile artists, etc. It’s important to me because if you don’t have good composition, then the work is not good. Color plays a big role, too.

KF: What’s your process for approaching composition?

JJJ: It’s a therapeutic process. I meditate a lot. Whatever speaks to me or makes sense to me—I just go for it. I don’t question anything. I just let it talk to me. The fabrics talk, the colors talk, the textiles talk to me. I think I have a natural eye for what looks good and what doesn’t, so I just go with what my gut tells me.

KF: It sounds like a lot of your work comes from artistic intuition. What does that intuition feel like and how does it bring ideas to life?

JJJ: With my current educational background, I can sense what people like and don’t like, in a way. Looking at other successful artists—and this is where it gets tricky—you don’t want to compare yourself to them or defeat yourself because you’re not where

they are. But I look and study historic painters and photographers, what they’ve done, and what people have accepted them into. The intuition comes more from my experience and my education. I know what is not hot and what is.

KF: Your work was featured in BUTTER 2. What was it like to have pieces on display in a space specifically meant to highlight Black art?

JJJ: It was a great experience. I’m from Indianapolis, but I’ve never had work exhibited or on display here. People know me as a fashion photographer, so it was my first time introducing myself as a textile artist here. I had two pieces purchased. I don’t know who bought the second piece, but the first piece was bought by the Richmond Art Museum in Richmond, Indiana. I’m really excited. It is in their permanent collection.

KF: You spend a lot of time in Detroit because of its larger arts community and platform for representation. What are some notes Indianapolis can take from other cities like Detroit?

JJJ: Indiana needs more spaces. It needs more galleries that participate in national art fairs. It needs more galleries in general. We need more shows. There’s definitely talent in Indiana, but I wish there were more opportunities for up-and-coming artists to show off their work.

KF: What’s the best part about being an artist?

JJJ: No one can tell you what to do. You can do whatever you want. It can be a full-time career if you’re in it long enough, take the right steps, and know the right people. You can travel. It’s you living your own life. You don’t have to work for anybody, which is the ultimate goal for me. You create your own language. You create your own world. That’s why I like being an artist. ✂

“YOU CREATE YOUR OWN LANGUAGE. YOU CREATE YOUR OWN WORLD. THAT’S WHY I LIKE BEING AN ARTIST.”

WHAT STARTED AS A ONE-TIME GIFT THAT FUNDED A SINGLE PUBLIC ART PROJECT HAS CHANGED THE ENTIRE LANDSCAPE OF DOWNTOWN FORT WAYNE IN LESS THAN A DECADE.

WORDS BY JENNY WALTON + PHOTOGRAPHY BY KELSEY MATTHIAS

“Leaders have come to fully understand the economic impact of having this much art in our downtown space.”

SINCE 2005, FORT WAYNE HAS FUNCTIONED AS A GEOGRAPHICAL REFERENCE POINT FOR ME. I WENT TO COLLEGE IN UPLAND, INDIANA, WHICH IS OFF OF I-69 HALFWAY BETWEEN INDY AND FORT WAYNE. FOR YEARS, I’VE BEEN TELLING PEOPLE TO GO TO HYDE BROTHERS BOOKSELLERS—ARGUABLY THE BEST BOOKSTORE IN INDIANA— AND THE FOELLINGER-FREIMANN BOTANICAL CONSERVATORY, AS I THOUGHT THAT SUMMED UP WHAT THERE WAS TO SEE IN FORT WAYNE.

In the summer of 2021, when my partner and I took a day trip to Indiana's second-largest city, I was floored by a downtown practically overflowing with murals. After speaking with artist and community organizer Alexandra Hall of Art This Way—the engine behind many of these projects—I’ve learned that my reaction is pretty common.

Hall was approached in 2015 by the Fort Wayne Downtown Improvement District to help utilize funds that had been earmarked for a creative project to encourage the walkability of a downtown that Hall describes as “very gray and taupe.” According to Hall, that first installation was just the beginning.

“The art came first, which was followed by this overflow of visitors and then this reinventing of the space that goes beyond the public art,” Hall says. “You could maximize that by putting up seating and allowing restaurants to serve people out of these spaces or allowing people to bring their takeaway to these alley spots.”

While the private sector was initially hesitant, local firms and businesses were still quick to appreciate the value of the impact. Hall reflected, “These leaders know that the young people they need in order to stay competitive were finding these

new spaces downtown enticing and something that was encouraging them to stay or to move to our city. And while they might not have liked every piece of art, they have come to fully understand the economic impact of having this much art in our downtown space.”

You could say the rest is history. What started out as a single project has blossomed into a culture where new developments have begun including future murals in the building plans. Art This Way provides funding to support at least one community-driven mural each year, but the business community is funding others and individual artists are making their own projects. Visit Fort Wayne features an online interactive map to guide people through the rapidly growing collection of installations across the city.

This open invitation to participate excites Fort Wayne-based artist Theoplis Smith III, who goes by Phresh Laundry. Smith speaks to the opportunity to be a bridge for the future of art and the generations who will be making it. Increasingly, this art is moving out of frames and onto the streets, and studies affirm the positive impact this public art is having on communities.

Smith’s proud of the work that’s happening, “Sometimes, you just gotta do something that’s never been done before to get where you need to go. You gotta give yourself permission to be great. We don’t just want to have these witty ideas, these dreams. We want to have tangible, accessible realities.”

Data collected by Americans for the Arts suggests that cities with an active and dynamic cultural scene—public art being a key factor—attract both individuals and businesses. But I think Hall says it best: “It can be difficult to quantify the impact of a mural, a clean alley, a new public park, a music festival, sidewalk improvements, and even the existence of a trash bin, but these elements within a public space impact our overall impression of a community. That matters because it’s our impression of a place that can determine whether we choose to invest ourselves in that place.”

So, the next time you’re near Fort Wayne, make sure you stop by the downtown district to see the murals–and the new Riverfront park and the pedestrian block at The Landing. In addition to, obviously, the Botanical Conservatory and Hyde Brothers Booksellers. ✂

What started out as a single project has blossomed into a culture where new developments have begun including future murals in the building plans.

MARK BRASTER IS A SELFTAUGHT GRAPHIC DESIGNER BASED IN FORT WAYNE, INDIANA WHO SPECIALIZES IN HELPING MUSICAL ARTISTS OPTIMIZE THEIR BRANDS THROUGH MERCH AND PROMOTIONAL ASSETS. BRASTER HAS WORKED WITH ARTISTS LIKE LIL WAYNE, KANYE, DJ KHALED, DMX, YOUNG MONEY AND MANY OTHERS, AND IS CURRENTLY THE LEAD DESIGNER FOR THE ROLLING LOUD MUSIC FESTIVAL. AS IF THAT WASN’T ENOUGH, BRASTER IS ALSO THE OWNER AND FOUNDER OF BRAST STUDIOS, A STREETWEAR BRAND. I BRIEFLY CAUGHT UP WITH HIM TO LEARN MORE ABOUT HIM AND HIS WORK.

POLINA OSHEROV: Growing up in Fort Wayne, where did your love of fashion come from?

MARK BRASTER: My mom was always very particular about this needs to match, or this and that, and it just stuck from when I was a kid. Then maybe my freshman or sophomore year of high school, I made up my mind that I wanted to get into fashion. I had no idea how, but I knew I’d figure it out..

PO : What are some of the challenges of running a fashion brand in Indiana?

MB: I’d love to be able to source fabrics and have the clothing cut and sewn locally. That’s the biggest thing. Also, I love doing oversized prints on shirts and the printers here tell me that they can’t do it. I get it done all the time, just not in Fort Wayne. No one seems to have the right equipment here.

PO : You’re completely self-taught. And you have the aesthetics and the taste, the hustle, and the work ethic, so what do you think drives you?

MB: I just always want more. I don’t want this to come out the wrong way, but I just want to be the best, and the best version of myself. And the more placements, the further I progress, it just literally energizes me and pushes me to go even harder and I’ve always been like that. I ran track, I played football, and I was the same way with that. That’s just how I am.

PO : I understand that you are a guy who is really good at last minute projects.

MB: Yeah. Honestly, the majority of the projects that I’ve been given were completely last minute. And they

always say, “I’m sorry” but, I’m used to it at this point. It is what it is, whatever it takes to get it done.

PO : I think that that’s maybe a small part of your success, right? Because I think that there’s a lot of people who would be put out being asked to work really hard at the last minute and turn down gigs, but you seem to thrive on it.

MB: It is frustrating at times, but like I said, whatever it takes to get it done. I’m willing to do the work. I know that it’ll pay off in the long run, and I feel like that’s the most important thing. You know, it’s easy to focus on the now but the long run is what really matters.