1

2

4 Forewords

前言 14 Timeline (1906 - 2019)

時序 16

1906: A Child Emperor 天子誕生

20

1919: Mentor to an Emperor 西學蒙師 30

1932: The Puppet Emperor

34

1945: The Emperor & the Interpreter

42

1946: A Testament to a Friendship

The Red Fan

50

1950: A Parting Gift: The Watch

56

Farewell Forever

58

An Emperor's Eye-View of China 御筆遺稿

64

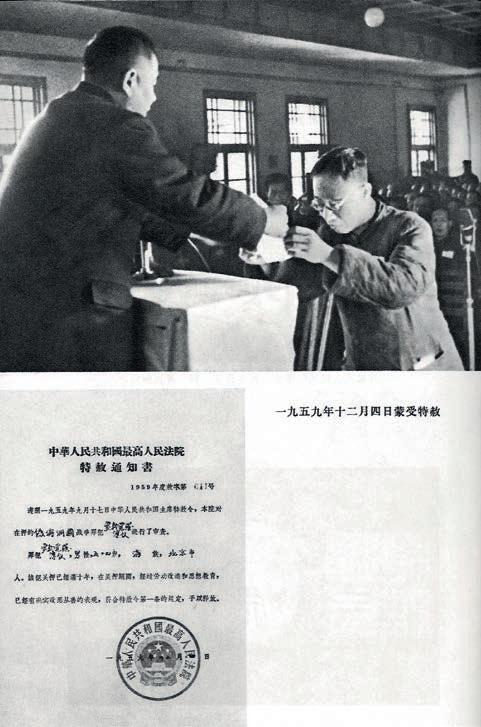

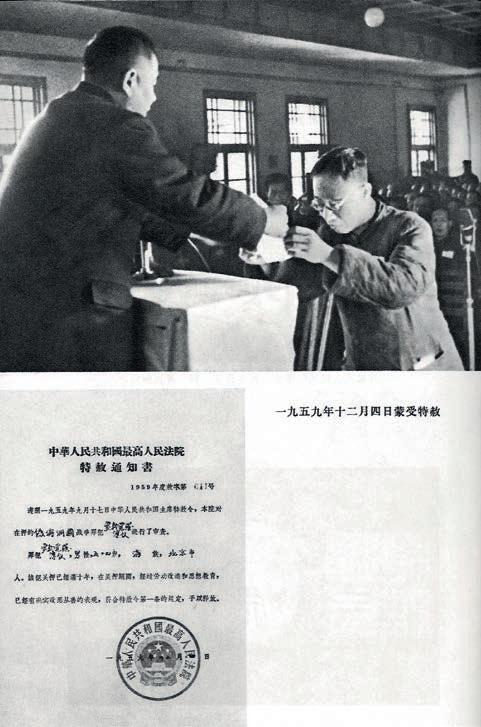

1959: A New Citizen

68

3

傀儡皇帝

獄中翻譯

扇中摯情

饋贈名錶

後會無期

新中國人

考據報告 78 Biographies 簡介 87 Acknowlegments 鳴謝

The Research Journey 研究之旅 73 ArtDiscovery Report

Foreword

by Aurel Bacs Senior Consultant, Phillips in Association with Bacs & Russo

Quite literally, the number of watches in the world are countless and by today also the number of collectors. And equally, the number of reasons why collectors search for their impossible-to-find collector’s watch: sometimes it is the mechanics, sometimes the aesthetics, the rarity, the condition, and in many cases, all of them and more. Who can wholeheartedly say when picking up a vintage watch that they have never, quite literally, asked the watch “if only you could tell me your life”. And to those who wondered where and with whom a watch has been during the past decades, including myself, provenance and the human histories behind a particular watch are another key-reason to be attracted to this world.

Throughout the years, when handling watches with a history, I caught myself thinking of the love stories they must have witnessed such as with the Joanne Woodward Paul Newman Daytona, Hollywood history with Marlon Brando’s bezel-free GMT-Master worn in Apocalypse Now, sports history with Jack Nicklaus’ gold Day Date, and the course of history such as Bao Dai’s iconic reference 6062, to name a few. Through research in archives, especially when talking to friends and families of the previous famous owners, but also scholars and witnesses, one builds a relationship with those who wore these watches and in a certain way, starts getting to know them.

Puyi’s spectacular Patek Philippe reference 96QL in platinum with full calendar is no exception and over the course of the last three years I have started to discover, once again, the most irrational but by far most interesting and emotional aspect of watch collecting: the histories they can tell us, the friendships they stand for, and all the highs and lows of mankind. The present Calatrava has seen an imperial lifestyle as well as witnessed captivity, indescribable luxury and hardship, but most importantly, the friendship and respect that Puyi and Permyakov built in a matter of less than five years. By all means, I do not wish to sound overly dramatic, nor will I recite John Lennon’s “Imagine”, but throughout the journey with research lasting into late nights and weekends, I was often reminded that the two men could not have been more different with their opposite upbringing, languages, religions, politics and belonging to different nations, yet they became friends and respected each other until the time they parted in 1950. This watch has witnessed their relationship and I often caught myself asking this Patek Philippe “if you could only tell me your story”.

Whatever to you the most captivating aspect of this iconic museum-quality wristwatch is, I wish you endless hours of deep-diving into history when studying the catalogue that you are holding in your hands and hope that you experience the same indescribable emotions when discovering the watch, its history and the friendship between the two men as we experienced while researching it.

‘One builds a relationship with those who wore these watches and in a certain way, starts getting to know them.’

Aurel Bacs

前言

世上名錶浩如煙海,如今藏家數量也不相伯仲。同樣,鐘錶愛好者 對各自追求的夢想藏錶也有千萬情結——有的渴求機械超卓,有的 鍾情美學、珍稀、品相等優越條件,但更多時候,眾人理想中, 總有一應俱全,甚至錦上添花的絕世佳品。當古董錶盈於掌心,

誰能誠心保證未曾暗自私語:「假若錶能帶我窺探它的過去,那有 多好呢。」我和許多沉迷鐘錶藝術的同好一樣,對一枚手錶的歷程、 所涉的人和事,一概深感著迷。藏品來源、藏家故事,往往是一件時計 精品何以令舉世趨之若鶩的終極原因。

我鑒賞鐘錶多年,每當經手來源深刻的錶品時,總對它所見證的 故事產生無限遐想,比如影壇頂級銀色夫妻鍾安.活華(Joanne Woodward)及保羅.紐曼(Paul Newman)的「地通拿」(Daytona)

所銘刻之不渝愛情;馬龍.白蘭度(Marlon Brando)在《現代啟示錄》

佩戴無錶圈「GMT-Master」所烘托的好萊塢盛景;傑克.尼克勞斯 (Jack Nicklaus)金色「Day Date」所編織的體壇神話;越南保大帝經

典「型號6062」所敲響的歷史回聲。追源溯始的過程十分寶貴,尤其是 訪問藏家親友、咨詢學者、搜索時人等各方互動,讓我們仿如置身 歷史時刻,與諸多名人錶主隔空對話。

溥儀超絕的百達翡麗「型號96QL」鉑金全曆腕錶,固然是一次蕩氣迴 腸的溯源之旅。過去三年,我埋首在鐘錶鑒藏史上最令我拍案稱奇, 又最為激蕩人心的一次奇遇。一件時計巨作,同時見證歷史、譜出友 誼,走過人間的高山低谷。這枚經典雋永的「卡拉卓華」(Calatrava), 承載溥儀從一朝天子到身陷囹圄、由享盡帝皇榮華到飽嘗落難辛酸 的傳奇章節。但最為重要的是,它印證著溥儀與別兒面濶夫五年間 建立的友誼和尊重。即使實情的確如此峰迴路轉,我也無意渲染戲劇 色彩,更不會濫調式引用約翰.列儂(John

Lennon)《Imagine》

的經典名句。但無數通宵達旦、廢寢忘食的苦研日子裏,我不時領悟 到兩個出生、成長、語言、宗教、政見和國籍迥異的人,原來可以如此 親近,成為朋友,相互敬重,直至故事中兩位主角1950年分道揚鑣為 止。每當沉思這枚百達翡麗,我不禁幻想:「假若它能帶我窺探 其過去,那有多好呢。」

無論這枚曠古絕倫的頂級名錶對您而言洵為何物,我都希望閣 下能夠細閱手中圖錄,沉浸在珍藏記載的壯闊歷史,在認識腕錶、 其時代背景,以至兩位歷史人物的寶貴情誼之時,能像我們在經年 累月的求索旅程一樣,體驗到筆者溢於文辭的情感思潮。

5

富藝斯鐘錶部資深顧問

「我和許多沉迷鐘錶藝術的同好一樣, 對一枚手錶的歷程、所涉的人和事, 一概深感著迷。」

Foreword

by Thomas Perazzi

Head of Watches, Phillips in Association with Bacs & Russo, Asia

In 2019, when I received a telephone call in my Hong Kong office informing me of the existence of a certain Patek Philippe watch in platinum, I almost fell off my chair out of excitement. However, when the caller informed me of the provenance of this venerated model my initial excitement soon turned to become one of my most significant and memorable moments in my years as a watch specialist.

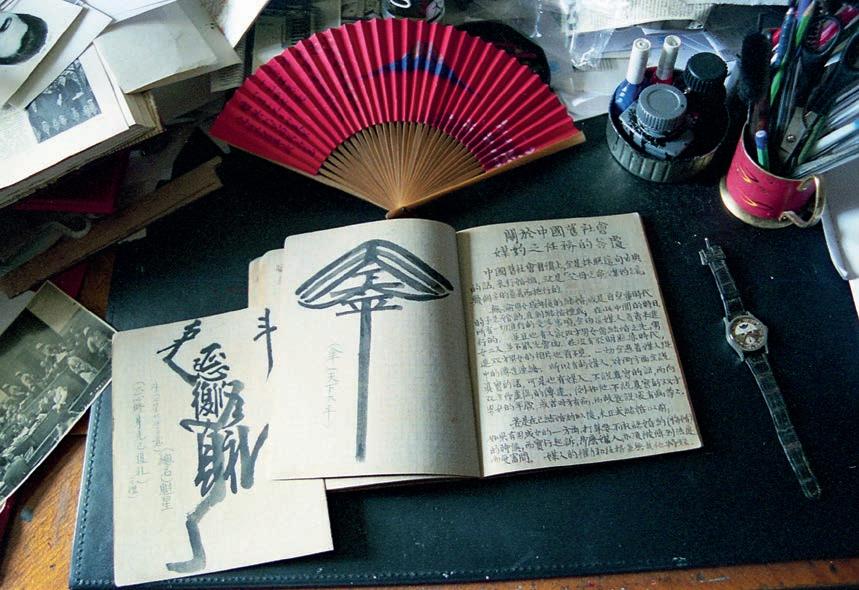

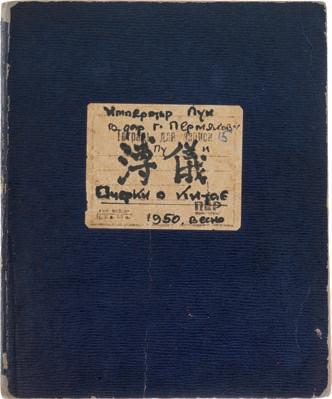

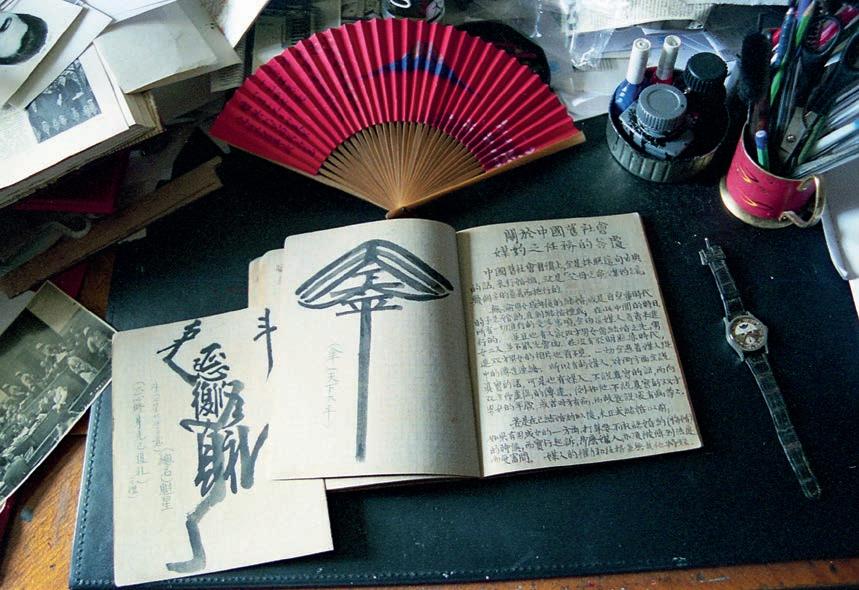

The watch in question was the Patek Philippe Ref. 96QL with triple date and moon phase in platinum. It came to Phillips accompanied by an antique red fan, a notebook carefully filled with personal observations, watercolour paintings, and a leather-bound edition of Confucius’s Analects. More auspicious and surprising was the provenance of this collection, being the one-time possessions of Aisin-Gioro Puyi, known throughout the world as "The Last Emperor."

One of the crucial conditions for Phillips to be entrusted with the sale of this watch was to provide iron-clad proof of the provenance of the watch and its accompanying artefacts. Thus, begun my mesmerising journey to a bygone era of unimaginable luxury of the Forbidden City, to a tumultuous and war-ridden China, and on to the Russian Far East, retracing decades of Puyi’s life to uncover the remarkable story of the watch and artefacts.

Three years on, after working closely with our team of specialists in scientific tests and historical research, I am proud to present to you our findings in this catalogue.Through the narratives of our different commentators, you will experience the momentous emergence of a new China, the lives disrupted and transformed by history. Most important, we will document a touching friendship that developed in spite of a vast divide in the cultural, racial and social backgrounds between the two main figures in this little-known story, one between Puyi and his Russian translator Permyakov.

I look forward to welcoming you to Phillips’ Hong Kong watch preview and auctions in May at our new Asia headquarters in Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District.

‘My initial excitement soon turned into one of the most significant and memorable moments as a watch specialist.’

Thomas Perazzi

彭博時

前言 彭博時

富藝斯鐘錶部亞洲區主管

2019年,我在富藝斯香港辦公室接到電話,得知一款百達翡麗鉑金腕 錶仍然存世,雀躍不已。當來電者向我訴述藏品的顯赫出處時,起初的 興奮頓成我的鐘錶鑒賞職業生涯中沒齒難忘的重要時刻。

上述時計正是本圖錄的主題:百達翡麗型號96QL鉑金腕錶,搭載全曆 和月相顯示,附有一把紙扇、一本筆記本、一組水彩畫和一本皮質封面的 《論語》。它們皆來自末代皇帝愛新覺羅.溥儀。

富藝斯受託拍賣這枚名錶附帶關鍵條件,考證手錶和上述藏品的來源, 追源溯本的過程亦由此而起:從紫禁城內鐘鳴鼎食的奢華盛世,到戰火 紛飛的動盪時代,再到苏联的東北角落。當中歷經溥儀幾十年的滄桑 人生,揭開了御用手錶和藏品的非凡典故。

在此期間,富藝斯團隊與科學考證專家和歷史研究学者通力合作。

三年飛逝,本人誠意呈獻我們的努力成果,一一收錄於本圖錄之中。

這通過不同對談者的敘述,閣下將會體驗到新中國的誕生為不少人士 帶來深遠改變,在文化、種族和社會的巨大差異下,溥儀和他的翻譯 別兒面濶夫(Permyakov)在亂世中仍然建立了深厚友誼,難能可貴。

本人誠邀閣下在五月蒞臨富藝斯位處香港西九文化區的亞洲新總部, 到訪香港鐘錶拍賣和預展,欣賞末代皇帝的曠世遺珍。

7

「起初的興奮頓成我的 鐘錶鑒賞職業生涯中 沒齒難忘的重要時刻。」

Foreword

by Wang Wenfeng

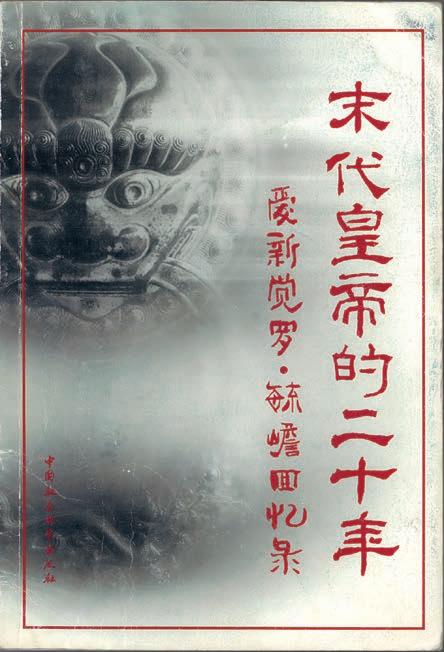

Aisin-Gioro Puyi is a unique figure in history. From the last emperor of imperial China, to a puppet ruler of Manchukuo, to a war criminal, and eventually to an ordinary citizen, there is hardly another example in history, whether in China or elsewhere. Puyi's unparalleled story itself is an epitome of historical changes in China during the first half of the 20th century. It is such uniqueness of Puyi’s life that has drawn enormous attention and enthusiasm for his study.

In 1982, the Palace Museum of the Manchurian Regime, an institute specialising in Puyi’s studies, reopened. During the restoration of the Palace, which is where the museum was situated, an interview project with members of the Aisin-Gioro family and witnesses of the related histories began. It was this year that I graduated from university and landed a job at the museum, where I became very passionate in understanding and researching Puyi. It was a rare opportunity to be involved in interviewing members of Puyi's family relatives and the concerned, all of whom were still alive. I interviewed Pujie, Runqi, Puyi's second, third, fourth and fifth younger sisters, as well as his nephews including Yuyan, Yuzhan and Yutang, his personal attendant Li Guoxiong, and his wives, Li Yuqin and Li Shuxian, who were both alive at that time. The conversations allowed me to learn about many interesting stories that had never been revealed to the public. After years of studies and research, I conceived the book The Last Emperor Puyi and National Treasures, a true representation of the secrets and stories concerning Puyi and national treasures

When I saw the collection of artefacts, I recalled some of the details of the interview, such as Puyi's platinum calendar watch. Yuyan vividly recalled, "I was loyal to Puyi during our time in the Soviet prisons, so he rewarded me with a calendar-embedded platinum watch. Right before we were extradited by the Soviet Union to China, our belongings were inspected. Puyi whispered asking if I still have the watch, I confirmed it was with me. When I gave it to Puyi, he turned around and handed it to the Soviet interpreter, Permyakov, who was inspecting us."

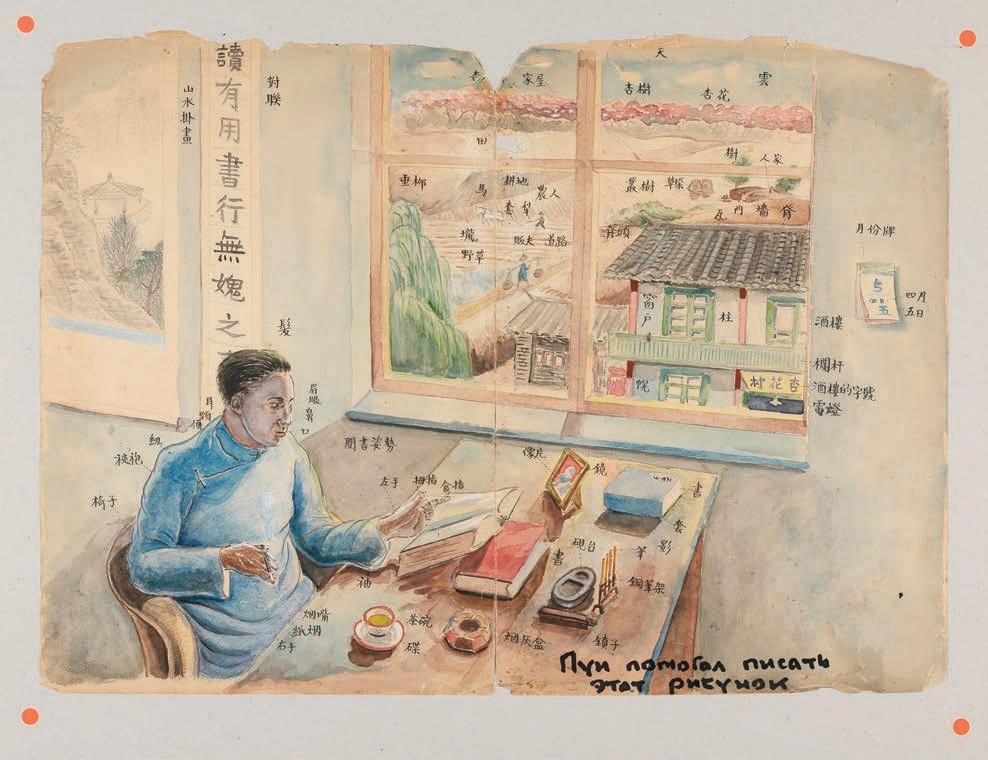

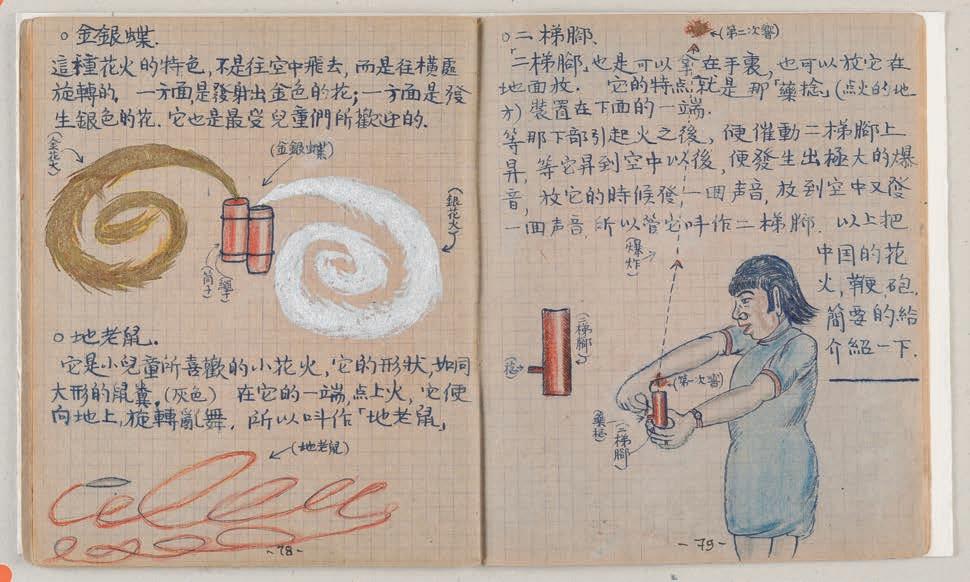

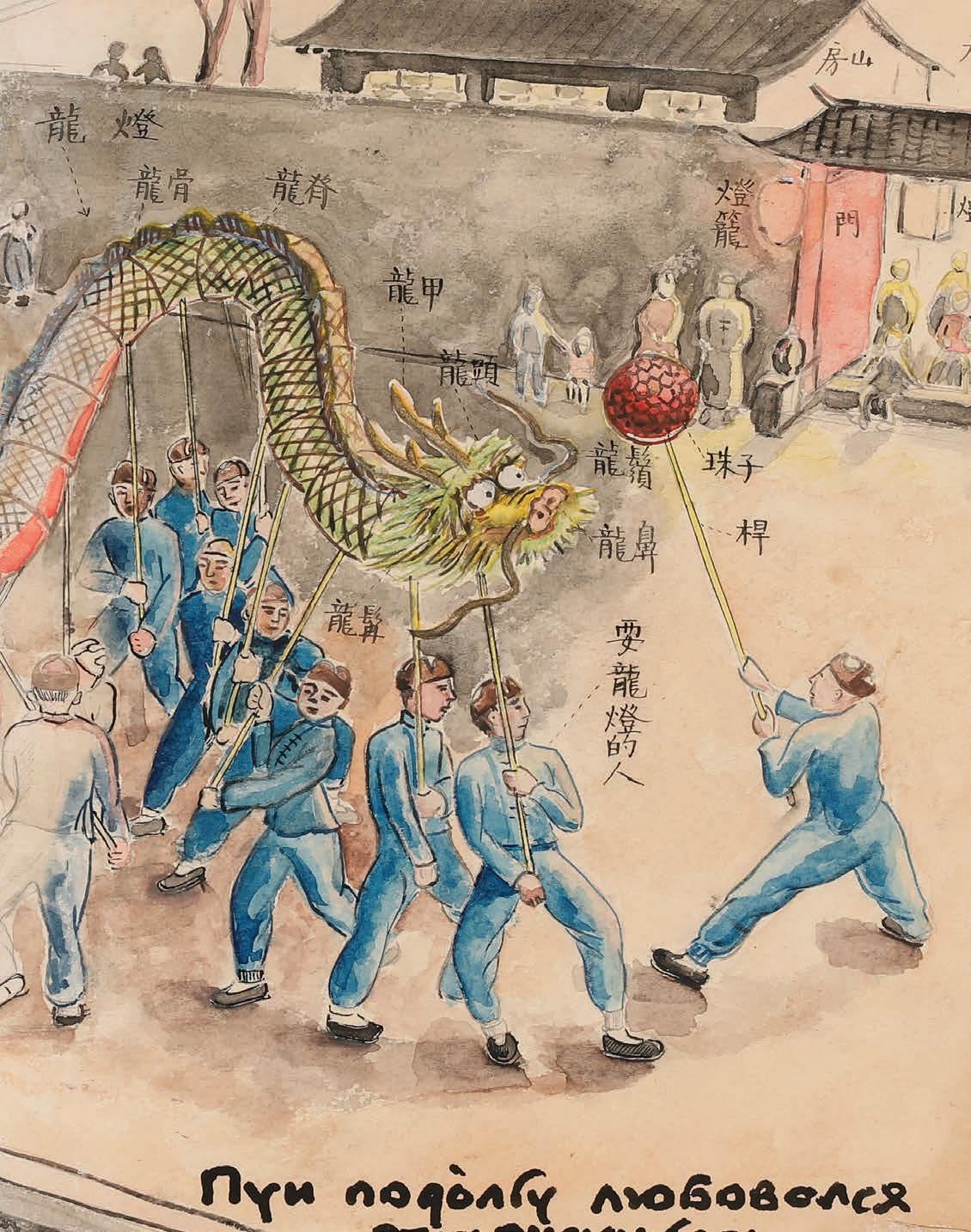

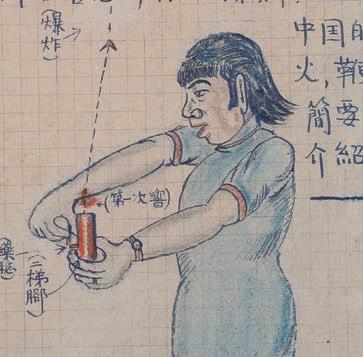

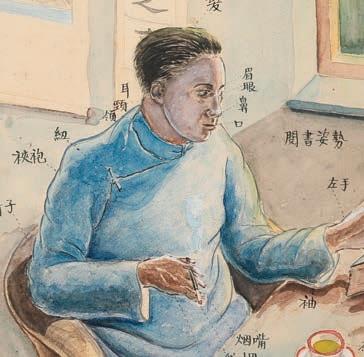

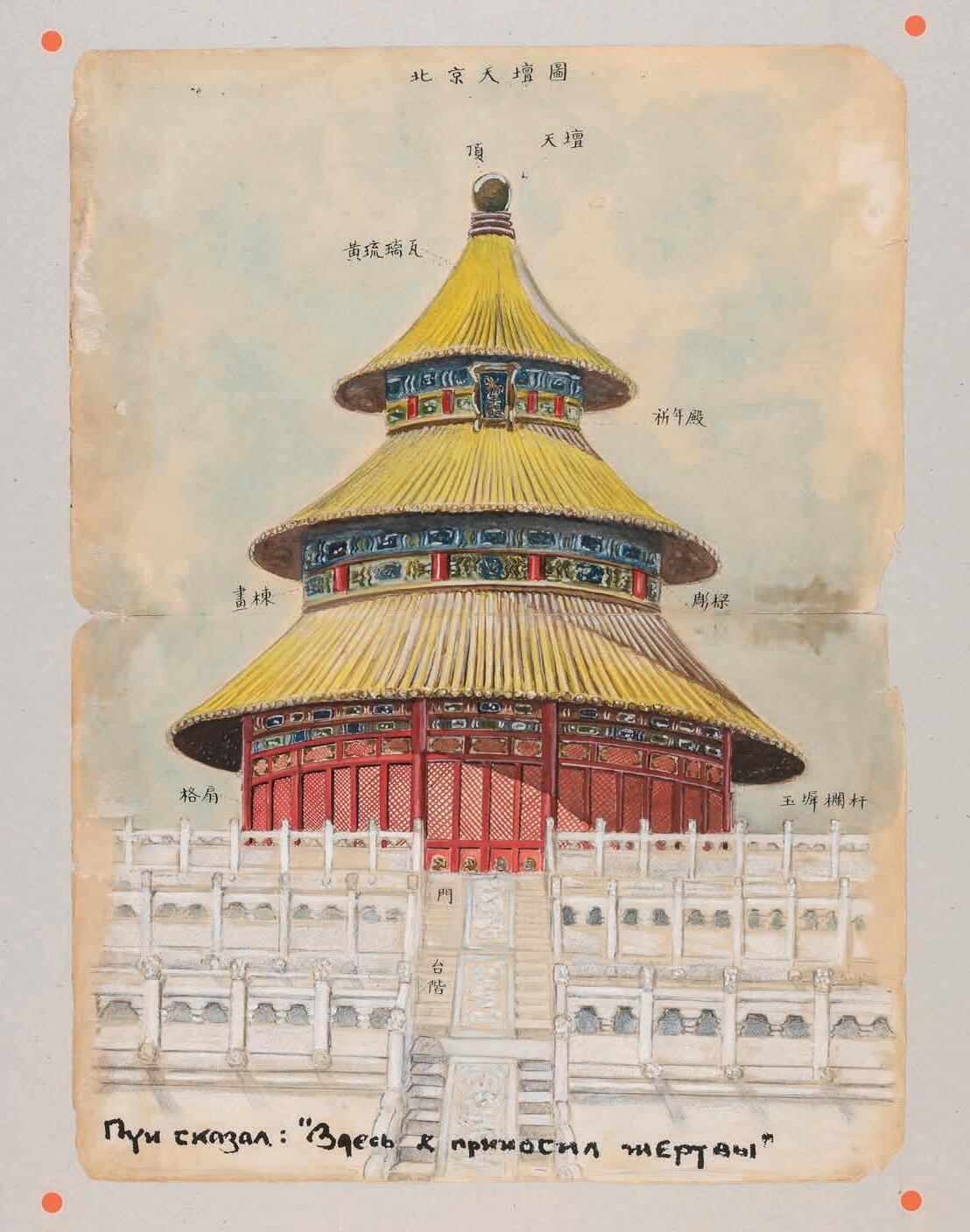

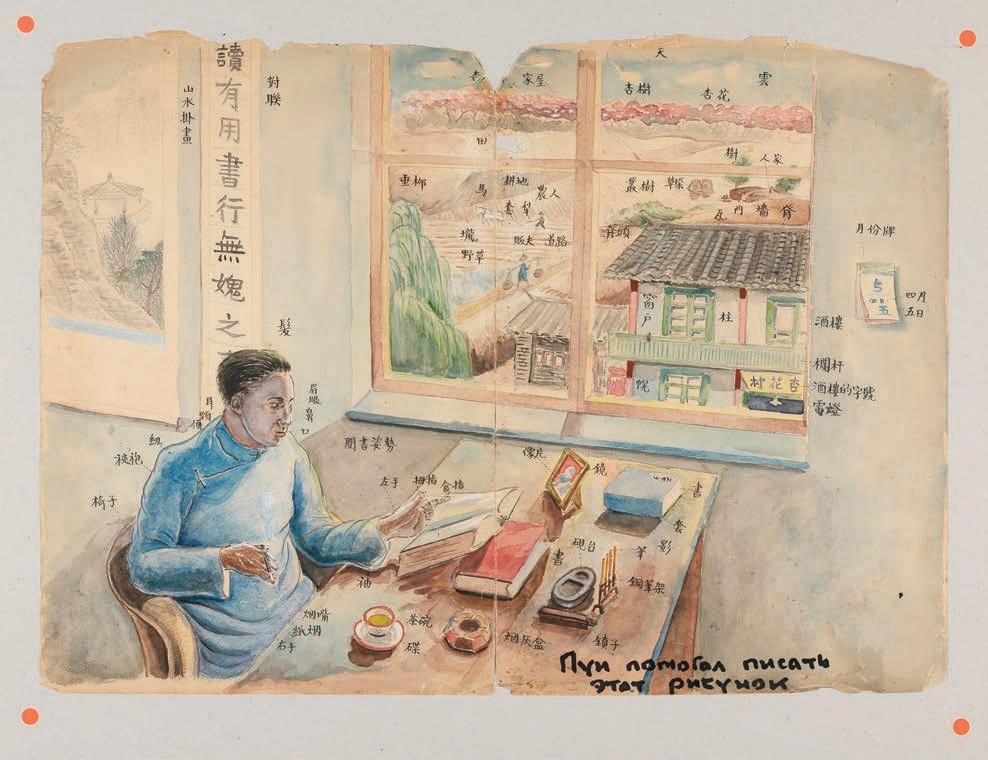

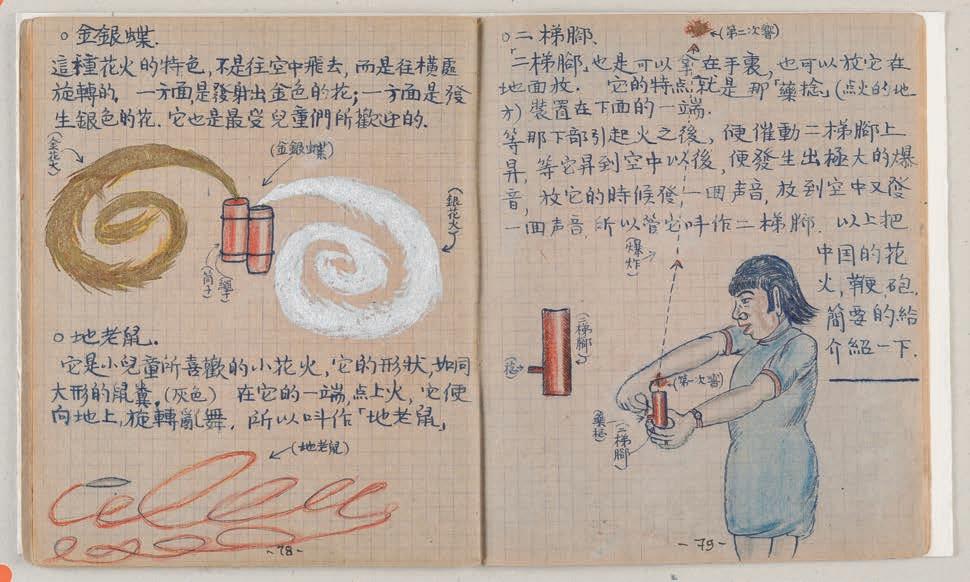

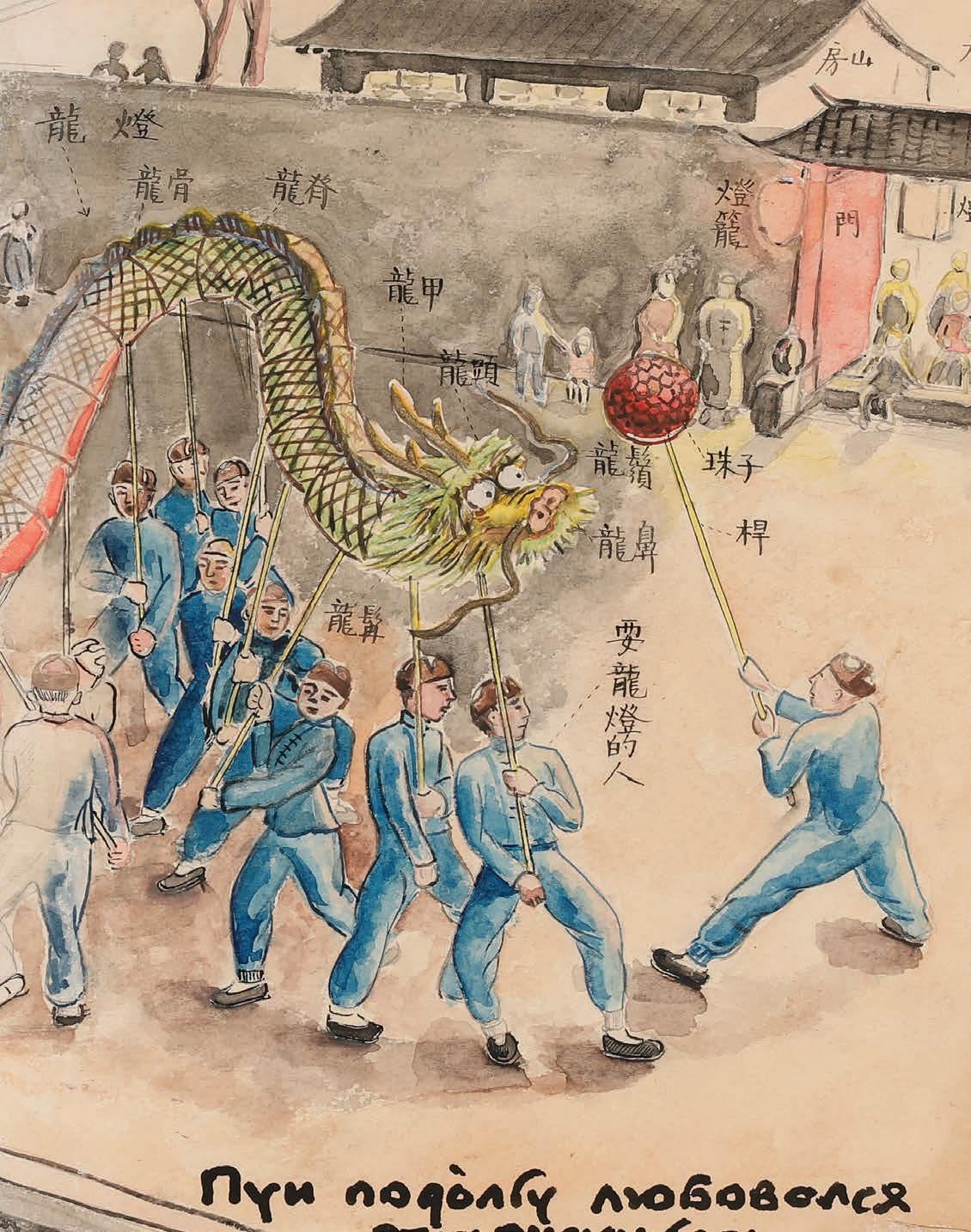

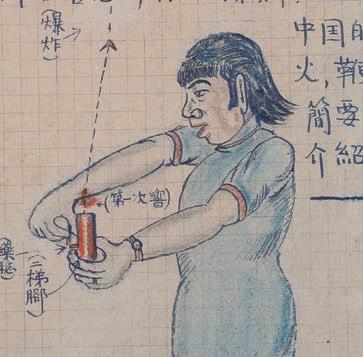

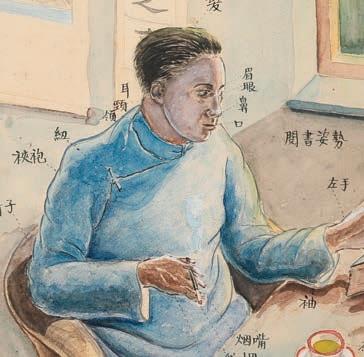

Li Guoxiong also mentioned how he repaired Puyi's glasses and camera while in the Soviet camp, and how he was asked to take apart the watch and remove the surface of the dial to check if it was made of platinum. Regarding the manuscripts of Puyi, Runqi's recollections can be evidence. ‘I am Puyi's brother-in-law on two levels, one as his wife’s younger brother, another as his third younger sister’s husband. Because of this strong tie, I have been living closely with Puyi since I was a child. Life in the Soviet Union was rather boring, I therefore killed time by drawing. As my drawing skill was better than Puyi’s, I drew and Puyi wrote inscriptions, and so we became a prolific duo. Looking back, it was such a fun time!’ The fan, which Puyi gave to Permyakov at the Tokyo Trial, is inscribed by the latter, the last emperor, in terms of handwriting, style and brushwork. Puyi’s calligraphic work has hardly survived to this day, to say nothing of the even rarer fan inscriptions. All these contribute to the high value of such unique examples.

‘When I saw the collection of artefacts, I recalled some of the details of the interview, such as Puyi's platinum calendar watch.’

Wang Wenfeng

Former Researcher of the Palace Museum of the Manchurian Regime, Founder and Former Secretary General and Chief of Staff of Puyi Research Society

王文鋒

前言 王文鋒

前偽滿皇宮博物院研究員 「溥儀研究會」前任秘書長兼辦公室主任

愛新覺羅.溥儀是一個特殊的歷史人物,他從中國封建社會最後 一個皇帝,到偽滿洲國傀儡皇帝,又到戰犯,最後到普通老百姓,這是 古今中外僅有的特例。溥儀自身獨特的人生經歷折射出了20世紀上 半葉,中國社會的歷史變遷。正是由於溥儀這種特殊性,激起了人們 對研究他的興趣和熱情。

1982年研究溥儀的專門機構偽滿皇宮博物院恢復了,在修復偽滿 皇宮舊址的同時,開始採訪愛新覺羅家族成員和歷史當事人知情者 的工作。也就在這一年,我大學畢業來到偽滿皇宮工作,對溥儀的了 解和研究,自然激起了我的興趣。參與了對溥儀家族成員及當事人 的採訪工作。那時候這些人都健在是難得的機遇。我多次採訪了溥 杰,潤麒,溥儀的二妹,三妹,四妹,五妹,以及溥儀的侄子毓嵒,毓嶦, 毓嵣,親信隨侍李國雄,和當時在世的兩位妻子李玉琴和李淑賢。通 過採訪,我知道了很多不為人知的宮中趣聞趣事。

經過多年的積累和研究,我寫了《末代皇帝溥儀與國寶》一書,真實的 再現了溥儀與國寶之間的秘密與故事。

當我看到這批文物時,便回想起了當年在偽滿皇宮博物院 採訪的一 些細節,比如溥儀那塊鉑金日曆手錶。毓嵒曾清楚地回憶道:在蘇聯 期間,由於我對溥儀的忠心,溥儀賞給我一塊鉑金日曆手錶,在我們 被移交回國前,蘇聯對我們攜帶的物品進行了檢查,溥儀小聲對我 說,那塊鉑金日曆手錶你戴了嗎?我說戴著呢,溥儀說拿過來,等我把 這個表交給溥儀時,溥儀轉身交給了正在檢查我們的蘇聯翻譯 別兒面濶夫。

李國雄也曾提到,在蘇聯期間,為溥儀修眼鏡,修照相機,以及拆卸 手錶,在錶盤上除下一些粉沫,檢驗是否是鉑金的情景。

關於溥儀那些手稿,潤麒的回憶可以得到驗證:「我是溥儀的小舅子, 還是他的三妹夫,由於這種特殊的關係,我從小就和溥儀在一起玩。 在蘇聯的時候由於閒著沒事可幹,我便隨手畫了些畫,我畫畫的手藝 比溥儀好,溥儀便在我畫得畫上添了許多字,這樣我們就合作完成了 很多作品,回想起來,真是好玩兒啊!」

溥儀在東京作證期間,寫給蘇聯翻譯別兒面濶夫的那幅扇面,無論 從字跡,風格,用筆等方面來看,確是溥儀所寫,溥儀流傳在世的墨跡 十分有限,扇面作品更是罕見,所以足見此扇面之珍貴。

9

「當我看到的這批文物時,便回想起了當年 偽滿皇宮博物院採訪的一些細節,比如溥儀 那塊鉑金日曆手錶。」

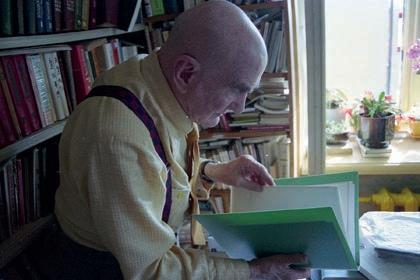

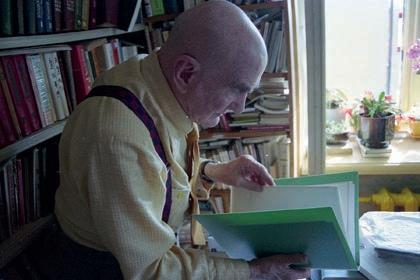

Foreword

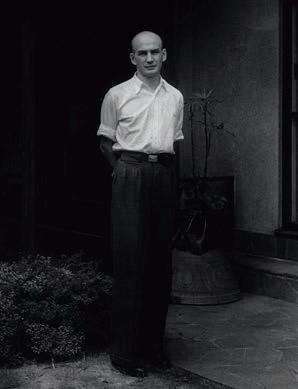

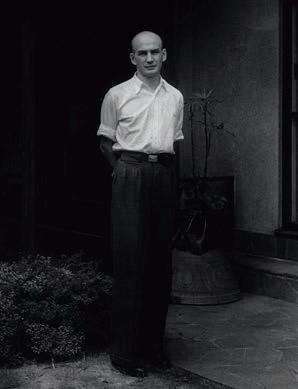

by Russell Working Journalist

The old man said he had proof. He’d known the last emperor of China. Look, he said, right here. Georgy Permyakov cleared the clutter on his desk and opened drawers to produce a beautifully painted fan, a notebook filled with essays in Chinese writing, and a priceless platinum Patek Philippe calendar watch. The essays were interspersed with whimsical figures formed out of Chinese characters.

‘You know who drew these? Henry Puyi, the last emperor of China,’ Permyakov said, referring to Aisin-Gioro Puyi by his English name. ‘That fan, he inscribed himself.’

These items, along with a lovely series of watercolours by Puyi’s brother-in-law, formed a unique collection that Permyakov had held after the former emperor’s imprisonment in the Soviet Union from 1945-1950. The year was 2001, and my wife, Nonna, had tracked down Permyakov—then 83 years old—in the Russian Far Eastern city of Khabarovsk. We were there to interview him for an unrelated story. What we hadn’t anticipated was Permyakov’s connection to Aisin-Gioro Puyi—also known as Emperor Xuantong—who ascended the Dragon Throne as a toddler in 1908. The elderly translator had interpreted for Puyi and taught him the Russian language and communist doctrine. Permyakov’s artifacts revealed a unique relationship. He and Puyi knew each other as captor and captive, yet there was evidence of a friendship between the two men. Puyi inscribed the fan as a gift for Permyakov when the two were in Tokyo in 1946, composing a poem in Chinese.

Puyi ascended the throne in 1908 at the age of 2 (3 years old for norminal age). After he was ousted in Beijing, the Japanese installed him as ruler of the puppet state of Manchukuo. When the Soviet army entered China and captured him in 1945, he spent five years in Soviet Union.

A home without a phone

It was a roundabout path that led us to Permyakov. As freelance writers based in Vladivostok, we travelled widely in Russia, as well as other Asian countries. In 2001, after a visit to Permyakov’s former hometown in Harbin, China, we caught the train to Khabarovsk, an Amur River city of about 600,000 people. Nonna ran across Permyakov’s name while paging through bound volumes of old, yellowed newspapers, looking for information on a post-war trial of Japanese prisoners in the Soviet Union. She asked reporters at a local paper if the interpreter was still around.

They said sure. He doesn’t have a phone, they said, but write him a letter and leave it at the post office. He comes and picks up his messages there. If he’s willing to talk, he’ll reply. The next day Permyakov had left a note for us. The answer was yes. We found him in a dreary apartment block, but his bookshelves were crammed with a lifelong author and linguist’s books and papers.

Why no phone? Well, they were hard to get in Soviet times, and he never requested a line anyway. This was one of the ways he kept a low profile. Although he had worked for the NKVD—the dreaded secret police later known as the KGB—government agents followed him throughout the Soviet era. He feared for his life. Bald-headed and full of infectious enthusiasm, Permyakov was a former athlete, teacher, and writer who remained robust into his eighties. As I wrote at the time:

Georgy Permyakov is 83 years old and so fit he will spring to his feet and pound his stomach to prove he retains some of the strength of his youth as a boxer. He never drinks or smokes, speaks six languages, and sleeps on his balcony in Khabarovsk most nights, even in Russia’s winter. He chatters in Japanese and Putonghua and is a little gleeful when visitors stare blankly back.[1]

The former interpreter cheerfully watched my jaw drop when he told me of his connection to China’s last emperor. I had learned about Puyi from The Last Emperor, a 1987 movie directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. The film portrayed Puyi’s capture by the Soviet Red Army in 1945 as he tried to flee for Japan. What the movie left out was the years Puyi subsequently spent in Soviet Union, relying on Permyakov for all his interactions with his captors. Some subjects you report on have a way of staying with you. Permyakov was one of them. In late 2001 Nonna and I left Russia. After freelancing from Cyprus, we ended up in Chicago, where I worked for the Tribune. But we sometimes reminded each other of the charismatic old interpreter. On bitter winter nights, we marvelled at Permyakov’s habit of sleeping out on his balcony in Khabarovsk, where temperatures can dip as low as minus 40 degrees. But more than two decades after we had interviewed Permyakov, I was surprised when the old story resurfaced in 2022. A researcher for Phillips messaged me. They were interested in talking to us. Oh, and did we have any photos of Permyakov, Puyi’s watch, the fan, and the other objects?

After so many years I said we almost certainly did not. But I had underestimated my wife’s organizational skills. It turned out she had stashed away a bound volume of the negatives I had shot of Permyakov and his treasures. And so we find ourselves involved once again telling the story of one of 20th-century China’s most fascinating figures. The artefacts themselves whisper tales of a fallen dynasty and of the transformation of its ruler from ordinary to citizen.

And while the collection hints at the tumultuous forces that created modern China, it also tells a more human tale—of the comradeship of an emperor and the interpreter who gave him his voice and helped him find his way in a foreign land.

11 [1] “His Last Translator,” South China Morning Post, 6 May 2001, accessed at http://khv9923.narod.ru/His_last_translator.pdf, 6 April 2023.

‘You know who drew these?

Henry Puyi, the last emperor of China... that fan, he inscribed himself.’

Georgy Permyakov

記者

那位老人說他認識中國末代皇帝,還有證據在手。

他說:「看,就在這裏。」

格爾基.別兒面濶夫(Georgy Permyakov)清理桌上雜物,打開抽屜,

拿出一把繪畫精美的紙扇、一本寫滿中文的筆記本,還有一枚名貴的 百達翡麗Quantieme Lune鉑金腕錶。

筆記本穿插著由許多漢字組成的怪誕圖案。

「你知道這是誰畫的嗎?是亨利.溥儀,中國末代皇帝」,別兒面 濶夫說。亨利(Henry)的是愛新覺羅.溥儀的洋名。「那把扇由他 親自題字。」

這些物品,加上溥儀妻舅兼妹夫創作的一系列水彩畫,自他們被關押 在蘇聯之後,一直由別兒面濶夫收藏。

那是2001年,我的妻子羅娜在俄羅斯遠東城市伯力,找到年屆83歲 的別兒面濶夫。當時我們對他進行與本故事無關的採訪工作。

始料不及的是,別兒面濶夫竟然認識鼎鼎大名的末代皇帝溥儀。

這位年老的翻譯家曾為溥儀擔任翻譯,並教導他俄語及共產主義 學說。

別兒面濶夫的藏品,籠罩著一股耐人尋味的神秘氛圍。他和溥儀, 一個是監營工僕,一個是戰爭俘虜,本該對立敵視。但證據顯示, 兩人不但沒有結仇,竟還譜出友誼。1946年,溥儀和別兒面濶夫身在 東京。溥儀在扇面上以漢字題詩,作為送給別兒面濶夫的禮物。

1908年,年僅三歲的溥儀登極稱帝。溥儀被逐出紫禁城後,由日本關 東軍扶植為滿洲國的傀儡皇帝。1945年,蘇聯軍隊攻入中國境內俘虜 溥儀,把他關押在蘇聯監營,囚禁歷時五年。

離群索居:不用電話的老人

拜訪別兒面濶夫的路途十分崎嶇。我和羅娜同是駐海參崴的自由 撰稿人,周游俄羅斯以及亞洲各國。2001年,我們參觀別兒面濶夫在 哈爾濱的故居後,便乘搭火車前往人口只有六十萬、位於黑龍江及 烏蘇里江交界的小鎮——伯力。

某天,羅娜翻閱舊報紙,尋找戰後蘇聯境內的日本囚犯受審資料。

閱讀期間,偶遇「別兒面濶夫」(Permyakov)這個名字。她到一家當地 報館,查詢這位翻譯是否尚在人間。

記者們說:「他當然健在。你要找的人沒有電話,但可以寫信,拿去 郵局便是。他習慣到郵局取信。如果他願意和你交談,便會回信。」

翌日,別兒面濶夫給我們留下了一張字條。答案是:「願意」。

我們在一棟殘舊的公寓找到別兒面濶夫。他藏書極富,書架塞滿書籍 和論文。那是一位年邁作家兼語言學家的畢生閱讀匯集。

為什麼不安裝電話?電話在俄羅斯並不流通,而且他也沒有這個需 要。別兒面濶夫深居簡出,多年來保持低調。這位沉實老翁身經百戰, 曾受聘於斯大林時代的內務人民委員部(NKVD),即國家安全委員會 (KGB)、俗稱蘇聯秘密警察的前身。退休後他仍對人生安危保持 警惕,謹慎隱藏行蹤。

前言 羅素.華京

別兒面濶夫光頭,活力十足,曾是一名運動員、教師兼作家。即使年過 八十,依然聲如洪鐘,精力充沛。正如我當時記述:

別兒面濶夫年屆八十三歲,還是非常壯健。他健步如飛,還刻意捶打 小腹,以證昔日拳擊技術。他不煙不酒,精通六種語言,天天在陽臺 就寢,嚴冬如是。他以流利日語和普通話喋喋不休,面對驚異得目瞪 口呆的訪客,則表現得格外雀躍。

眼前老人親述一段巧遇末代皇帝的奇聞,我被嚇得張皇失措。這位 翻譯界老前輩卻從容不迫,樂此不疲。

我對溥儀的認識,毫不意外地源自1987年貝托魯奇的經典電影 《末代皇帝》。電影重現了溥儀在1945年逃亡日本時被蘇聯紅軍俘虜 的一幕。但它所留白的,是溥儀在蘇聯伯力收容所的五年,以及鮮為 人知的一章——與別兒面濶夫合寫的異鄉情愫。

作為記者,職業生涯上總會遇到一些令你念念不忘的人物。別兒面 濶夫正是佼佼者,那光環在我記憶內縈繞不去。2001年底,羅娜與我 離開了俄羅斯,移居塞浦路斯從事自由撰稿,其後搬到芝加哥, 在《芝加哥論壇報》任職記者。寰球半圈,我們仍舊不時想起那位談笑 風生的傳奇老人。

無數嚴寒夜晚,我們總是想起別兒面濶夫席睡陽臺的習慣。

一想到氣溫低至攝氏零下40度的伯力如何冰冷刺骨,頓然嘖嘖稱奇, 非常佩服。

闊別這位老前輩二十多年後,更神奇的是,2022年我們竟重溫這則 奇幻迷離的故事。一天,富藝斯拍賣行一名研究員聯絡上我,說有意 與我們交談。我馬上想:「哦,我們還有別兒面濶夫、溥儀手錶、紙扇和 其他藏品的照片嗎?」

事隔那麽多年,我本能地認為答案必然是「沒有」。實情是,我低估了 我太太儲物成編的能力。原來她把我為別兒面濶夫及其寶物拍攝的 底片裝訂成冊,一直收藏至今。

就這樣,我們突如其來地再度走進這段歷史奇聞。這些藏品,承載著 一個盛世王朝的沒落,還有一朝天子脫變成社會公民的變幻人生。

藏品見證著現代中國的動盪時期,同時側寫了一個情味盎然的人間 故事——末代皇帝流落異鄉,在彷徨無助之際,一位翻譯雪中送炭。

13

「你知道這是誰畫的嗎?是亨利.溥儀, 中國末代皇帝…那把扇由他親自題字。」

13

格爾基.別兒面濶夫

1906—2019

1919, Scottish diplomat Sir Reginald Johnston is appointed as tutor to 13-year-old Puyi.

1919年,13歲的溥儀由蘇格蘭外交官莊士敦爵士擔任導師。

Aisin-Gioro Puyi is on born 7 February in the Prince Chun Mansion, residence of his father, located at Houhai (the ‘back water’) of the Shichahai lakes in Beijing.

1906年2月7日,愛新覺羅.溥儀生於北京什剎後海醇親王府。

On 12 February, 6-year-old Puyi abdicates at the outbreak of the Xinhai Revolution, ending the Qing Dynasty that had ruled China since 1644.

辛亥革命爆發,推翻清朝統治。1912年2月12日, 六歲的溥儀被迫退位。

1919 1922 1908

1917

On 2 December, upon the death of the childless Guangxu Emperor, Empress Dowager Cixi elevates Puyi, to the throne, era name Xuantong. 光緒皇帝駕崩後,溥儀按慈禧太后懿旨繼承大統,於1908年12月2日登基, 改元「宣統」。

In July, viceroy and Qing loyalist Zhang Xún attempts to reinstate the 12-year-old Puyi as emperor. This restoration lasts only 12 days before Puyi abdicates a second time.

1917年7月1日,張勳復辟,12歲的溥儀當了12天皇帝,宣佈二次退位。

1 December 1922, Wenxiu as his consort.

1922年12月1日,溥儀於娶婉容為妻,納文繡為妾。

1906 1912

On 15 August, Japan announces its surrender in World War II. On 19 August, Puyi hastily flees the dissolved state with close relatives including his brother, brother-in-law and nephews. On his way to board a flight to Japan, the Soviet Red Army captures the former emperor at the airport of Mukden (Shenyang). After his detention by Soviet troops, Puyi is imprisoned as a war criminal at Chita, Siberia, and Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East for a total of five years.

1945年8月15日,日本在二次大戰戰敗,宣佈無條件投降。四天後,溥儀帶同弟弟、妹夫、侄兒及幾位親信 逃亡日本,在奉天(瀋陽)機場被蘇聯紅軍俘獲,其後被囚禁在蘇聯赤塔及伯力收容所共五年。

Puyi is expelled from the Forbidden City 5 November 1924. He flees to the Japanese Legation in Beijing, then finds refuge in the Japanese concession in Tianjin in February of 1925. He lives in exile without an official title for seven years.

1924年11月5日,溥儀被逐出紫禁城。1925年2月,溥儀秘密前往天津,尋求日租界庇護, 渡過七年寓公生活。

1924 1931

Shortly after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria following the Mukden Incident on 18 September 1931, Puyi throws his lot in with the occupiers. Controlled by Japan’s Kwantung Army, Puyi is appointed chief executive of the new state using the era name of “Datong”. Few foreign countries recognize his Manchukuo realm.

1931年「九·一八」事變後,溥儀受日本扶植意圖復辟帝 國,由關東軍操縱,就任偽滿洲國執政。惟少數國家視滿洲 國為合法政權。

1945 1950

Puyi is declared emperor of the puppet state of Manchukuo on 1 March 1934 with the era name “Kangde”.

1934年,滿洲國改行帝制。3月1 日,溥儀正式登基為偽滿洲帝國 皇帝,年號「康德」。

Puyi marries Wanrong, consort.

1922年12月1日,溥儀於娶婉容為妻,納文繡為妾。

斯大林命頒令引渡溥儀及其他偽滿戰犯回國。1950 年8月1日,溥儀等人抵達綏芬河,被關押在撫順戰犯 管理所。

1922

Stalin orders Puyi and other prisoners from the Manchukuo regime to be returned to China. They arrive 1 August in the border town of Suifenhe. Puyi and others are detained at the Fushun War Criminals Management Centre.

tutor

1959

In 1946 August, Puyi testifies for the prosecution at the International Military Tribunal of the Far East. Permyakov accompanies him to Tokyo.

1946年8月,溥儀以歷史見證人身份出席遠東國際軍事法庭作證,由別兒面濶夫陪同。

April 30th 1962, Puyi marries Li Shuxian. 1962年4月30日,溥儀和李淑賢結婚

1960

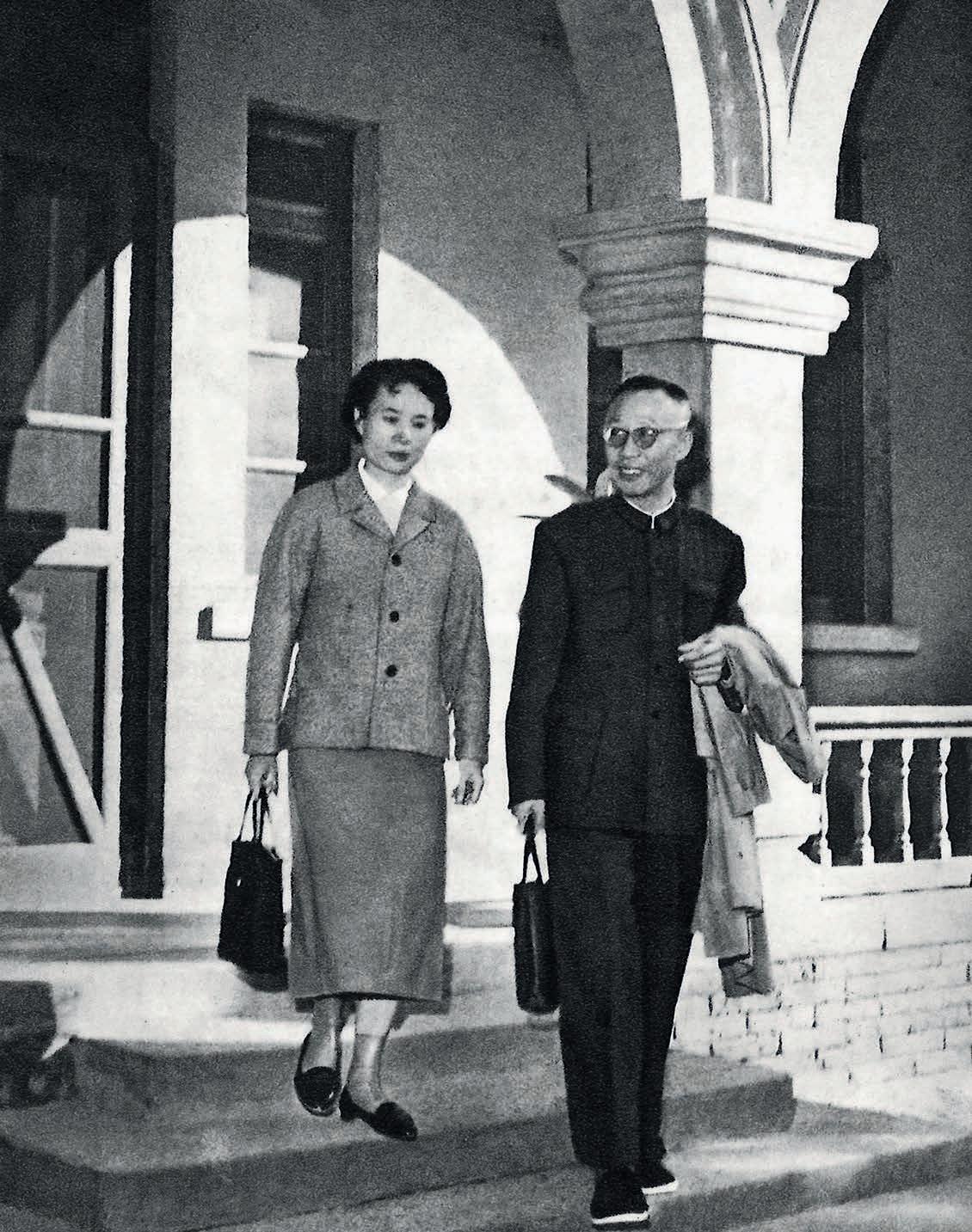

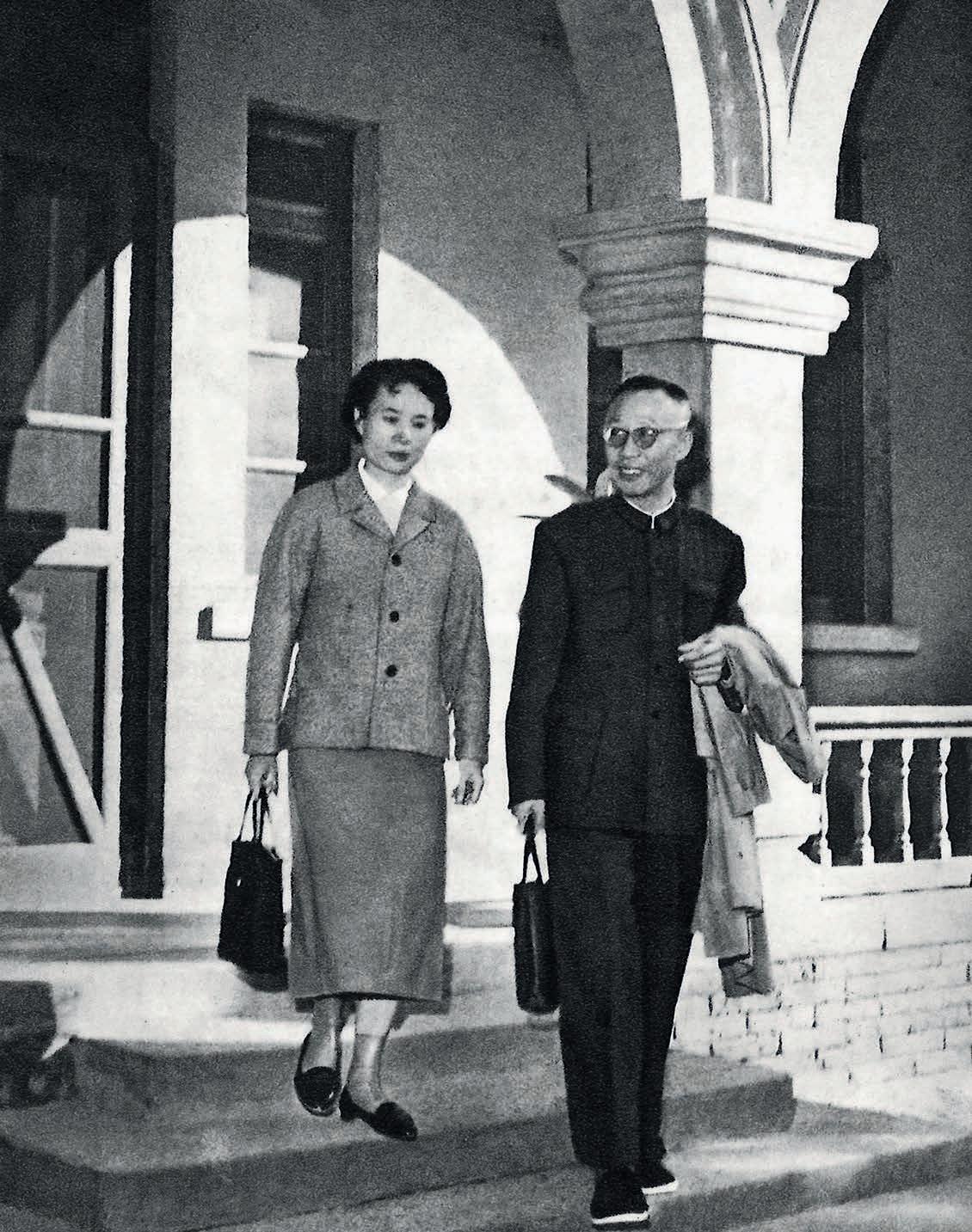

After 10 years of ‘intensive thought reform,’ he receives a special pardon on 4 December 1959. Puyi is among the first to be pardoned. After arriving in Beijing, Puyi takes up life as a common citizen of the new China.

1959年12月4日,經過十年思想改造的溥儀成為首批獲特赦的 戰犯,回京後成為新中國公民。

1962

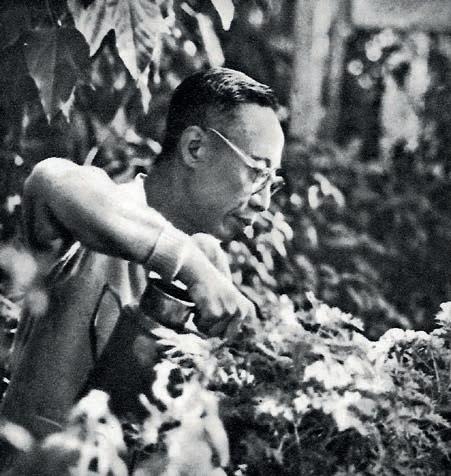

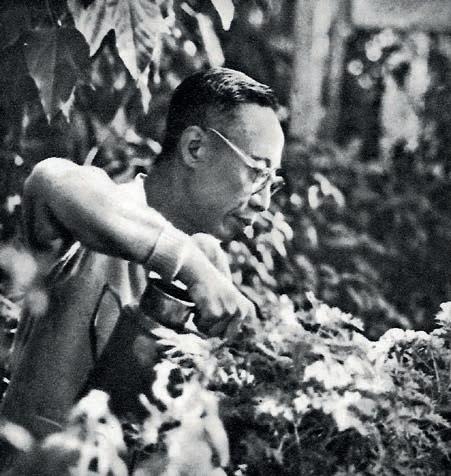

Puyi works as a gardener at the Beijing Botanical Gardens, then becomes a member of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. He works as an editor and writes his autobiography.

溥儀在北京植物園任職園丁,其後成為全國政協 文史資料研究委員會專員,期間從事編輯工作,並 撰寫自傳。

Puyi's Russian interpreter: Georgy Permyakov 溥儀的蘇聯翻譯格爾基.別兒面濶夫

1967

Russell and Nonna Working interview Georgy Permyakov in Khabarovsk, viewing the fan, watch, and notebook that Puyi gave him.

羅素.華京 及羅娜.華京在伯 力訪問別兒面濶夫,查看溥儀 送贈的紙扇、手錶及筆記本。

2001 2005

On 17 October, Puyi dies at the age of 61 of kidney cancer and uremic syndrome in Beijing.

1967年10月17日,溥儀因腎癌及尿毒症病逝於北京, 享年61歲。

富藝斯受委託拍賣末代皇帝愛新覺羅.溥儀遺珍。

2019

Permyakov passed away at the age of 88. 別兒面濶夫逝世,享年88歲。

Phillips was entrusted with the collection of the last emperor of Qing dynasty, Aisin-Gioro Puyi.

© Getty Images: Hulton Archive, De Agostini, ullstein bild

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇

Photo Courtesy Rubezh

Time

‘All his life a helpless tool of one agency or another... Puyi has longed to dodge the trappings of state and lead the life of a normal western youth.’ [2]

magazine

A Child Emperor 天子誕生

Zaifeng,

Pujie 淳親王載灃與他的孩子溥儀和溥傑。 © Getty Images: Hulton Archive 17 1 9 0 6

Prince Chun with his children Puyi and

A Child Emperor 天子誕生

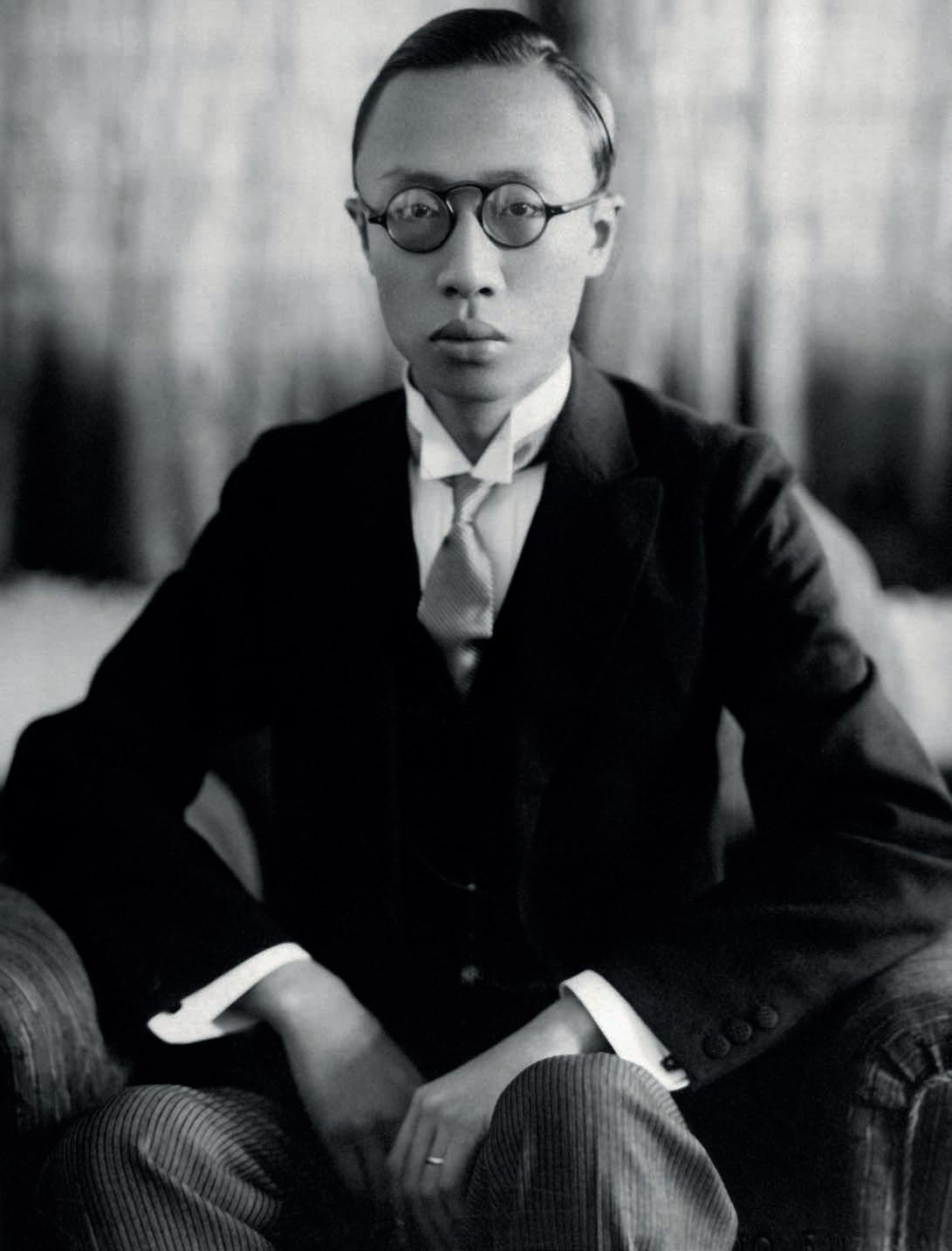

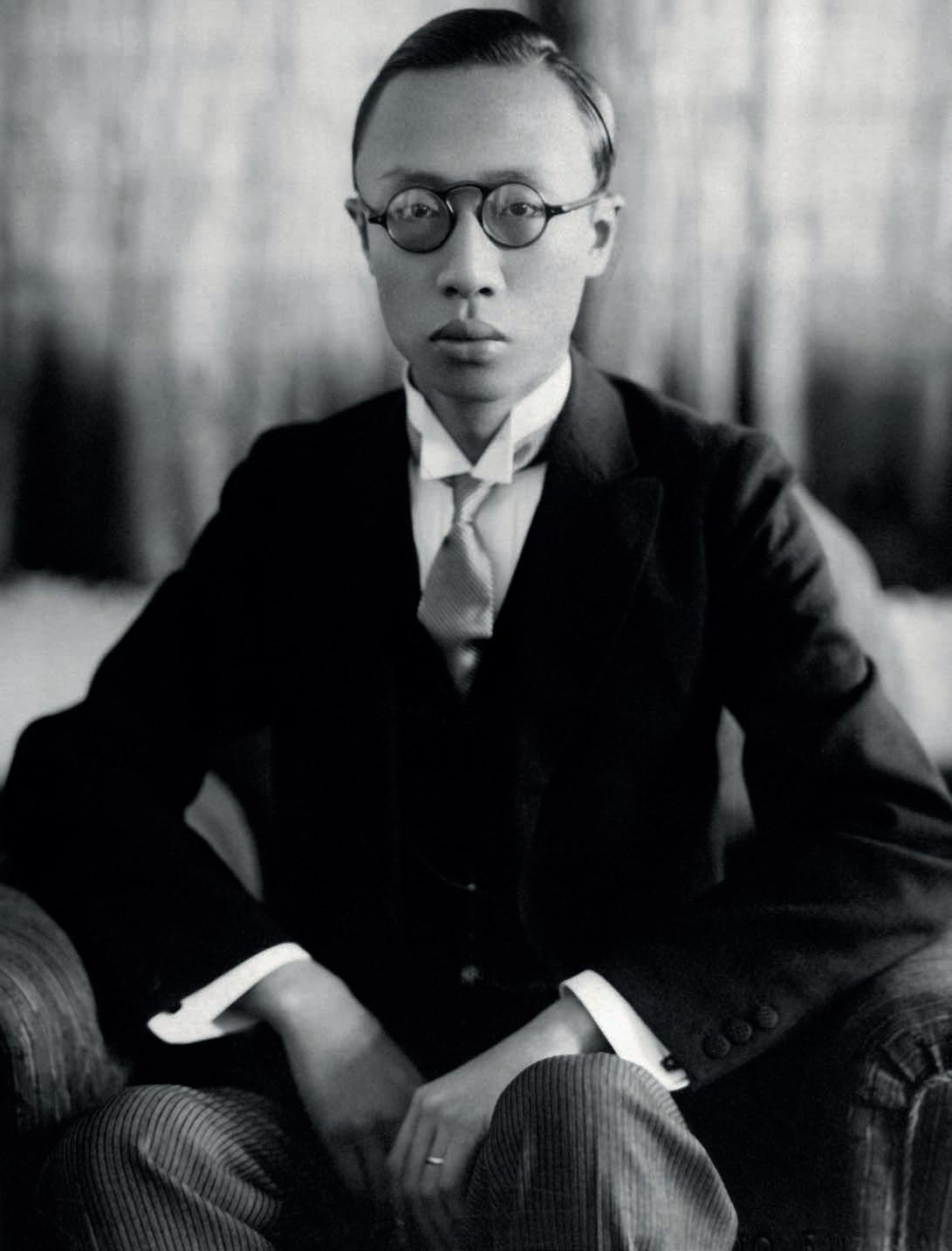

Aisin-Gioro Puyi was born 7 February 1906 in the residence of his father, Prince Chun. Upon the death of the childless Guangxu emperor, China’s shadow ruler, Empress Dowager Cixi, elevated the boy to the Dragon Throne 2 December 1908 as the era name Xuantong. He was 2 years old (3 years old for nominal age). This announcement caught the family unprepared. The grand chancellor simply showed up at the home of Prince Chun, accompanied by ornately dressed dignitaries and a retinue of cavalry and foot soldiers. The toddler scampering about, the family was told, had been appointed Son of Heaven. As the edict was read, Puyi’s grandmother fainted. He later had no memory of the event, but he was told that he threw a tantrum when the eunuchs of the court tried to take him away. The new emperor howled, writhed, and hit the strange men who tried to capture him. At last ‘the confusion was ended by my wet nurse who gave me the breast,’ Puyi writes.[3]

Brought to the palace, he would later retain a memory of ‘an emaciated and terrifyingly hideous face’ surveying him through a gauzy curtain. It was the empress dowager herself.

The boy trembled and screamed, ‘I want nanny, I want nanny!’

‘What a naughty child,’ Cixi snapped. ‘Take him away.’

Thus he entered a life lived by no other child on earth. Eunuchs carried Puyi about in a palanquin. Even a simple walk in the park required a retinue of servants and functionaries. He never left the Forbidden City and seldom saw other boys except when his brother and two or three other children from the imperial clan visited. He didn’t see his own mother for six years. Overnight, Puyi was treated as a god and was no longer able to behave as a child. The adults in his life, except for his wet-nurse Mrs. Wang, were all strangers; remote, distant, and unable to discipline him. Wherever he went, grown men would kneel to the floor in a ritual kow-tow, averting their eyes until he passed. Soon the young Puyi discovered the absolute power he wielded over the eunuchs, and frequently had them beaten for small transgressions.[4] The palace employed a thousand eunuchs to serve him. At every meal they laid out a banquet: six tables full of main dishes, cakes, rice, porridge, and preserved vegetables.

The Xinhai Revolution forced the child monarch’s abdication in 1912, ending the 267year Qing dynasty and an imperial system dating back two millennia. (An attempted restoration of the monarchy in 1917 lasted only 12 days.) Yet he was allowed to remain in the Forbidden City with a substantial subsidy from the state. In 1922 a 16-yearold Puyi married two women he barely knew. He had to choose from photographs of candidates presented by the imperial court. He picked Wenxiu, but the high consort said she wasn’t beautiful enough and instead designated a Manchu princess named Wanrong as his empress, with Wenxiu as his consort.

[2] Time magazine, ‘MANCHUKUO: Orchid Emperor,” 5 March 1934. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,747105,00.html.

[3] Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi, From Emperor to Citizen. Translated by W.J.F. Jenner, Oxford University Press, 1987, 31.A

[4] Behr, Edward, The Last Emperor. Toronto: Bantam Books, 1987, 63.

Left: Puyi as a child and Empress Dowager Longyu in the 3rd year of Xuantong.

左: 宣統三年時的溥儀和隆裕。

Right: Puyi in 1917.

右:丁己年的溥儀。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

「他一生都身不由己,任人擺佈」,《時代雜誌》在1934年報導說: 「溥儀一直渴望逃離國事,擺脫皇族枷鎖,像個西方青年般自由 生活」。

1906年2月7日,溥儀在醇親王府出生。無後嗣的光緒皇帝駕崩, 年僅三歲的溥儀由長期垂簾聽政的慈禧太后擁立繼位。1908年12月 2日,溥儀登極,改元宣統。

消息傳來之始,醇親王府上下措手不及。軍機大臣在衣著華麗的 貴族、騎兵、步兵隨行下,步入府中,宣佈隨處亂跑的溥儀被欽定 為天子。

攝政王宣讀慈禧太后懿旨之時,溥儀祖母老福晉嚇至暈倒。年僅 三歲的溥儀,對此事毫無印象,長大後聽人憶述,得知當時府內充滿 他的哭叫和大人的哄勸。攝政王、軍機大臣和內監手忙腳亂,把嚎啕 大哭的小孩抱走。溥儀在自傳《我的前半生》中寫道:「老人們說, 幸虧有乳母結束那一場混亂。乳母看我哭得可憐,拿出奶來喂我, 這才止住了我的哭叫。」

溥儀敘述進宮後,對慈禧太后的第一印象:「在我面前有一個陰森 森的幃帳,裏面露出一張醜得要命的瘦臉——這就是慈禧。」

溥儀顫抖著叫喊:「要嫫嫫!要嫫嫫!」

慈禧太后很不痛快地說:「這孩子真彆扭,抱到哪兒玩去吧!」

自此,溥儀踏進一個沒有其他孩子的大人世界。他出入每寸,都由 太監抬轎代步。即使在公園散步,也有多人同行。他從未離開過 紫禁城,也絕少見到其他男孩,僅有弟弟和其他兩至三名皇族小孩 到訪。他六年未見生母。

「一夜間,溥儀被捧為神,再也無法渡過正常童年。即使成年後, 除了乳母王連壽外,身邊都是疏遠、無法管教他的陌生人。無論溥儀 走到哪裡,成年男子都會跪地磕頭,避免直視,待他走開才起身。 很快,年輕的溥儀發現他對太監擁有絕對權力,常會因為瑣事而毆打 他們。」

宮內雇用了一千名太監侍奉他。每頓飯都有如酒席,以六張桌子擺滿 主菜、糕點、米飯、粥和鹹菜。

1912年,辛亥革命迫使溥儀退位,結束國祚長達267年的清朝, 推翻沿用兩千年的帝制。(1917年復辟令溥儀二度稱帝,但歷時僅十 二天。)然而,他被允許留在紫禁城,領受到國家俸祿,維持奢華生活。

1922年,十六歲的溥儀與兩位素未謀面的妙齡少女成婚。他從朝廷 準備的一批候選佳麗照片中,挑選了文繡。但有太妃嫌她樣貌遜色, 最終安排溥儀封滿族公主婉容為皇后,納文繡為妾。

19

‘Imitating Johnston I bought all sorts of trinkets to hang about myself: Watches and chains, rings, tiepins, cuff-links, neckties and so on... I asked him to give foreign names to myself, my brothers and sisters, my “empress”and my “consort”: I was called Henry and my empress Elizabeth.’

Aisin-Gioro Puyi

21

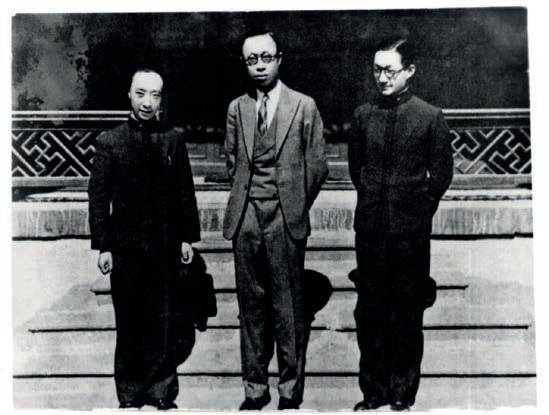

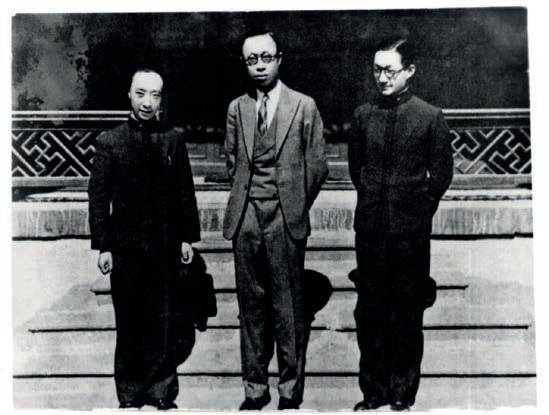

Sir Reginald Johnston with Puyi,Pujie and Runqi in the Forbidden City. 莊士敦與溥儀、溥杰和潤麒在紫禁城。

1 9 1 9

西學蒙師

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

Mentor to an Emperor

Mentor to an Emperor

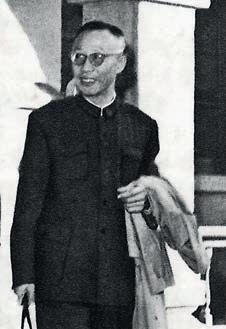

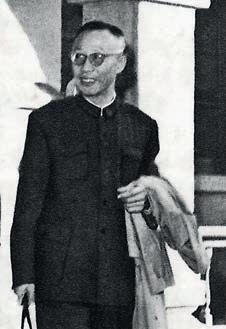

Early in 1919 Puyi was introduced to a new tutor who would change his life and influence his entire outlook on the world—including his personal aesthetics. This was a 44-year-old Scottish scholar and diplomat named Reginald Fleming Johnston. Like the actor Peter O’Toole, who played Johnston in the 1987 film The Last Emperor, Johnston had blue eyes and fair hair fading into grey.

Born in 1874, Reginald Johnston was educated at the Edinburgh and Oxford before entering the British colonial service. By the time he met Puyi, he was an experienced China hand who had travelled widely in the Middle Kingdom and published scholarly works on the language and culture.

It was Puyi’s first relationship with a foreigner. Until his 13th year the young monarch had had four tutors: three Chinese and one Manchu. In the old system, imperial teachers were so venerated, ‘They were not required to kneel in the Emperor’s presence, and the Emperor himself was allowed to stand when his tutors stood,’ Johnston would later tell The New York Times [5] With the Scotsman’s appointment, controversy embroiled the court over whether the foreigner should be regarded as a simple foreign language instructor, or granted the revered status of imperial tutor.

The emperor met his new tutor in the Yuqing Palace. Johnston recalls that the boy emperor wore imperial court dress and was attended by ‘functionaries in uniform.’ Puyi says his father and Chinese tutors also were present.

‘On being conducted into the audience-chamber I advanced and bowed three times,’ Johnston writes. ‘He then descended from his seat, and walked up to me and shook hands in the European fashion.’ [6]

Johnston withdrew, then re-entered the hall. This time Puyi bowed to this strange new figure in his life: ‘this was the way in which I acknowledged him as my teacher.’ [7]

Puyi’s earliest impressions of foreigners had been drawn from magazines and brief encounters in the imperial court. He was frightened by these odd people with their curling moustaches and hair and eyes of an alarming variety of colours. Johnston, however, was less disturbing. The boy emperor found the Scotsman’s Chinese easier to understand than some native dialects. Johnston stood so stiff, he seemed to have a steel frame under his clothes. But his hair and blue eyes did make the youth feel uneasy.

西學蒙師

[5] Price, Clair. ‘AS PU-YI APPEARS TO HIS OLD ENGLISH TUTOR; Sir Reginald Johnston, Who Saved the Boy Monarch's Life, Tells His Experiences.’ The New York Times, 17 July 1932, Section XX, 2.

[6] Reginald F. Johnston, Twilight in the Forbidden City. Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1934, 166.

[7] Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi, From Emperor to Citizen. Translated by W.J.F. Jenner, Oxford University Press, 1987, 109.

溥儀和婉容在天津張園接見庄士敦引荐的加拿大總督威靈頓夫妻。

23

Canadian Governor General Viscount Willingdon and his wife meet Puyi and Wanrong through Johnston's referral in Tianjin 1931.

© Gettyimages: De Agostini

Puyi in tennis outfit. 溥儀網球照。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

Puyi with bicycle in the Forbidden City 溥儀騎自行車。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

Puyi in tennis outfit. 溥儀網球照。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

Puyi with bicycle in the Forbidden City 溥儀騎自行車。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

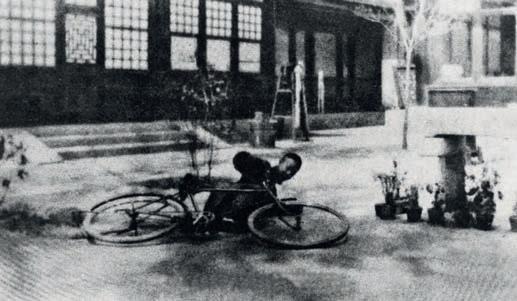

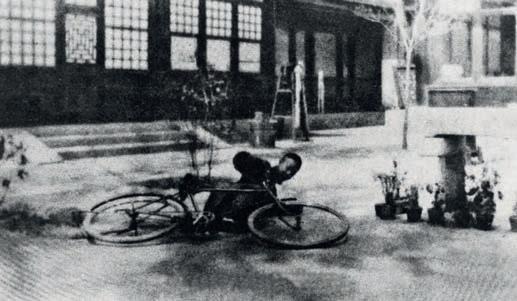

Johnston’s influence on the 13-year-old emperor went far beyond teaching English grammar. He opened a world beyond the Forbidden City. He got Puyi a bicycle to clatter about on. In class the teacher noticed that his pupil couldn’t read a clock on the desk right in front of him. Overcoming resistance from traditionalists who said an emperor shouldn’t wear glasses, he demanded an eye exam for the boy. Puyi received his first pair of spectacles.

Johnston’s influence extended to clothing. Admiring the Scotsman’s garb, Puyi began doubting the value of silk, and he embraced the Western styles of the Roaring Twenties. Woollen suits were in vogue, or tuxedos for formal wear, with jackets cut close to the waist. Fedora hats, braces, pinstriped fabrics, sportswear, and other European and American styles found their way into the monarch’s closets.

The emperor would later write: ‘Imitating Johnston I bought all sorts of trinkets to hang about myself: Watches and chains, rings, tiepins, cuff-links, neckties and so on,’ Puyi writes. ‘I asked him to give foreign names to myself, my brothers and sisters, my ‘empress’ and my ‘consort’: I was called Henry and my empress Elizabeth.’ [8]

While introducing Puyi to Western tastes, Johnston reinforced a centuries-long royal fascination with precious timepieces. From the late Ming to the Qing dynasties, hornate European mechanical clocks and watches became all the rage, overshadowing traditional Chinese clocks. In the nineteenth century, the imperial workshop commissioned similar models.

An offhand remark from his mentor caused Puyi to change his traditional hairstyle. When Johnston called Chinese queues ‘pigtails,’ the impressionable youth cut his off. This enraged his Chinese tutors and caused high consorts to weep, but within a few days a thousand queues disappeared from the imperial staff. Only his three Chinese tutors and a few senior officials defiantly kept theirs.[9] Puyi would wear his hair cropped in a Western style for the rest of his life.

In a court where eunuchs bore royals about on palanquins, Johnston introduced Puyi to the physical activity of Western sports, among them cycling and tennis. When the Palace of Established Happiness burned down in 1923, Puyi had a tennis court built on the site. On 22 October 1923, ‘the game of lawn-tennis was for the first time played within the walls of the Forbidden City,’ the Scotsman writes. The emperor and his brother partnered to take on Johnston and empress’s brother.[10]

25

[8] Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi, From Emperor to Citizen. Translated by W.J.F. Jenner, Oxford University Press, 1987, 113. [9] Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi, From Emperor to Citizen. Translated by W.J.F. Jenner, Oxford University Press, 1987, 114. [10] Reginald F. Johnston, Twilight in the Forbidden City. Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1934, 343.

‘The game of lawn-tennis was for the first time played within the walls of the Forbidden City.’

Sir Reginald Johnston

1919年初,溥儀開始跟隨一位新來的導師學習。這位導師將改寫他 的世界觀、品味,以至人生。他是四十四歲的蘇格蘭學者兼外交官 約翰.弗萊明.莊士敦(Reginald Fleming Johnston)。與1987年電影 《末代皇帝》中扮演莊士敦的演員彼得.奧圖爾(Peter O’Toole) 一樣,莊士敦擁有一雙藍眼睛,以及一頭略帶花白的銀髮。

莊士敦生於1874年,愛丁堡大學及牛津大學畢業後,被派駐出任 英國殖民地官職。當他赴京擔任溥儀導師之時,已周游中國多年, 是一位經驗豐富的中國通,曾出版有關漢語及中華文化的學術著作。

莊士敦是溥儀首位接觸的外國人。十三歲前的溥儀受教於四名帝師, 都是漢、滿族的翰林學士。帝師地位超然,「在皇帝面前無需下跪。 當皇帝站著,帝師可以坐下。」莊士敦在《紐約時報》的一篇訪問中 如是說。即使莊士敦極受溥儀重視,宮內大臣對應否向其頒受帝師名 銜存有爭議。

莊士敦在毓慶宮會見身穿朝服的溥儀皇帝,後來在書中憶述現場 尚有「穿著各式官服的官員」。據溥儀自傳所述,當時他父親醇親王及 其他傳統帝師也在場。

莊士敦在回憶錄《紫禁城的黃昏》中寫道:「我被帶入毓慶宮覲見 皇上,上前行了三鞠躬禮。皇上走下來到我面前,作歐式握手。」

莊士敦行鞠躬禮後退出門外。溥儀在自傳中寫道:「然後,他再進來, 我向他鞠個躬,這算是拜師之禮。」

溥儀對洋人的最早印象,來自雜誌圖片,以及以往在宮內的短暫 接觸。他對這些長滿粗鬍、一頭捲髮、眼珠異色的怪人感到恐懼。 然而,莊士敦卻不那麼令他不安。小皇帝發現這位蘇格蘭學者的流利 京話,比一些中國方言更容易理解。溥儀這樣形容莊士敦:「他的腿 也能打彎,但總給我一種硬梆梆的感覺。特別是他那雙藍眼睛和淡黃 帶白的頭髮,看著很不舒服。」

莊士敦對這位少年皇帝的影響,遠遠超越教授英語文法。他為溥儀 開啓了知識大門,讓他了解紫禁城外的精彩世界。他給溥儀買了一輛 單車,讓他在城內自由騎行。課堂上,莊士敦發現溥儀無法讀出桌上 時鐘顯示的時間。宮內傳統大臣認為一朝天子不能佩戴眼鏡,最終 還是被莊士敦說服,讓溥儀接受眼科檢查。患上近視的溥儀,得到 人生第一副眼鏡。

莊士敦對溥儀的衣裝打扮有著深遠影響,如溥儀筆下「教育我像 他所說的英國紳士那樣的人」,令末代皇帝開始欣賞著蘇格蘭人的 服裝,懷疑中國絲綢的價值,崇尚起席捲歐美之「咆哮的二十年代」 衣著潮流。時髦的羊毛套裝、高貴宴會的燕尾服、貼腰的外套、費多 拉帽、吊帶褲、細條紋織物、運動服和其他歐美風格服飾通通進入 皇帝的衣櫥。

溥儀寫道:「我按照莊士敦的樣子,大量購置身上的各種配飾:懷錶、 錶鏈、戒指、別針、袖扣、領帶,等等。」莊士敦更為溥儀及同輩起了 洋名。溥儀:「我請他給我起了外國名字,也給我的弟弟妹妹們和我的 『后』、『妃』起了外國名字,我叫亨利,婉容叫伊莉莎白。」

莊士敦把各式各樣的西方文化傾囊相授,令溥儀眼界大開,如癡 如醉。云云西洋珍寶中,有一樣令溥儀情有獨鍾。那說不上是新事物, 皆因清宮早已對它趨之若鶩。那就是西洋鐘錶。自明末到清朝, 華麗的歐洲機械鐘和手錶風靡宮廷貴族數百年,使傳統的中國鐘錶 黯然失色。十九世紀,清宮奉皇帝御旨仿照西洋技術製作鐘錶。

莊士敦甚至改變了溥儀的髮型。溥儀記述:「只因莊士敦譏笑說中國 人的辮子是豬尾巴,我才把它剪掉了。」此舉令太妃們痛哭,帝師們 多天不悅。可是,經末代皇帝一剪,「千把條辮子全不見了」,只有三位 帝師及幾位內務府大臣仍留辮。自此,溥儀終生蓄著西式短髮。

宮內太監慣用轎子為溥儀代步。莊士敦向溥儀介紹西方體育活動, 包括單車和網球。1923年紫禁城內的建福宮被燒毀後,溥儀在原址 興建了網球場。莊士敦寫道:「1923年10月22日,紫禁城的高牆內 第一次有人打起了網球。」溥儀等人組隊對打——他和溥傑成一隊, 莊士敦和潤麒成一隊。

「我按照莊士敦的樣子,大量購置身上的各種配飾: 懷錶、錶鏈、戒指、別針、袖扣、領帶,等等… 我請他給我起了外國名字,也給我的弟弟妹妹們 和我的『后』、『妃』起了外國名字,我叫亨利,婉容 叫伊莉莎白。」

愛新覺羅·溥儀

Puyi and Reginald F. Johnston. 溥儀和約翰.弗萊明.莊士敦。

© Getty Images: ullstein bild

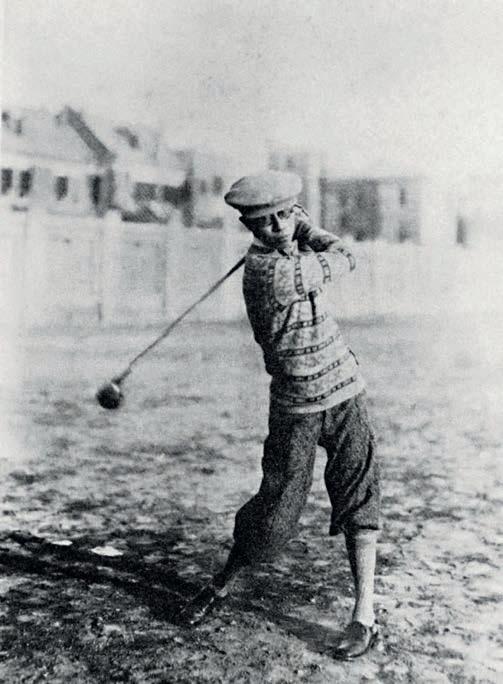

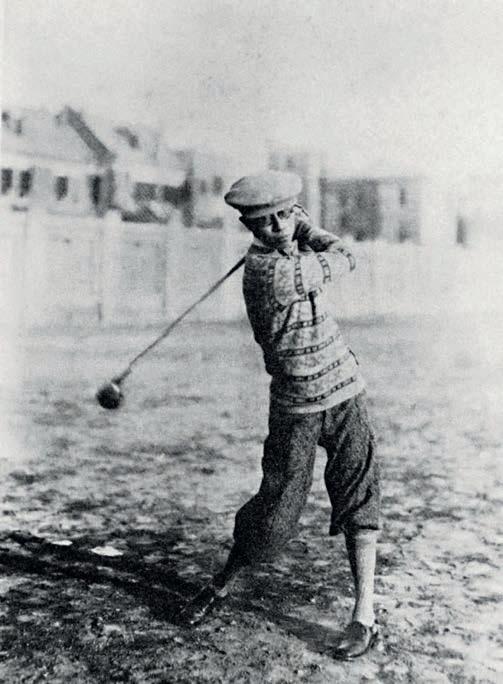

Puyi takes a swing on a golf course in Tianjin. 溥儀在天津打高爾夫球。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

Puyi and his sisters playing a game of golf in Tianjin. 溥儀和其二妹,三妹等人 在天津打高爾夫球。

Puyi takes a swing on a golf course in Tianjin. 溥儀在天津打高爾夫球。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

Puyi and his sisters playing a game of golf in Tianjin. 溥儀和其二妹,三妹等人 在天津打高爾夫球。

27

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

Puyi with Imperial Preceptor Zheng Xiaoxu and Reginald F. Johnston. 溥儀與帝師鄭孝胥和約翰.弗萊明.莊士敦。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

Puyi with Imperial Preceptor Zheng Xiaoxu and Reginald F. Johnston. 溥儀與帝師鄭孝胥和約翰.弗萊明.莊士敦。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

Flight from Beijing

In 1924 government troops expelled the imperial family from the Forbidden City, forcing Puyi to take up residence with his father. Fearing for his life, and egged on by Johnston, the former emperor decided to flee Beijing.

Interestingly, given the items in this collection, a watch, clock, and camera store played into his scheme to escape. As Johnston and his pupil set out for the Legation Quarter where foreign representatives were located, Puyi’s father—who opposed leaving the capital—sent along a steward to keep an eye on them, Puyi writes.[11]

Johnston suggested that he and his royal pupil slip into the store, hoping his father’s spy would grow bored waiting outside and head home. Puyi ‘dillied and dallied,’ and eventually bought a French gold watch. Puyi was traveling incognito, but Johnston slipped and called his fledgling by his imperial title, huang shang, the tutor writes in his memoir, Twilight in the Forbidden City. Customers and employees started, and one of them rushed out to spread the word. Soon a crowd gathered to gawk.

‘They were gazing upon their former emperor for the first time,’ Johnston writes.[12]

Unable to get rid of the steward, Puyi pretended he was ill. Johnston escorted him to a German hospital where they managed to ditch the determined servant. As a blinding yellow sandstorm descended upon Beijing, a carriage met Puyi at the back door and spirited him to the Japanese embassy.

Puyi found refuge in the Japanese legation in Tianjin, where he lived in exile without an official title for six years.

1924年,馮玉祥等領軍包圍紫禁城,把溥儀逐出宮外,結束遜清 皇室小朝廷。溥儀到父親載灃的宅邸醇親王府暫住,但擔心危機 在前,加上莊士敦的勸告,最終決定逃離北京。

無獨有偶,溥儀逃亡期間,與本珍藏遙相呼應的事物——手錶、時鐘和 照相機店,發揮了關鍵作用。莊士敦協助溥儀出洋,尋找大使館庇護, 載灃卻主張留京。溥儀記述:「我們剛上了汽車,我父親偏要派他的 大管家張文治,陪我們一起去。」

為擺脫監視,莊士敦想了個辦法。溥儀寫道:「我們先到烏利文洋行 停一停,裝作買東西,打發張文治回去。」二人走進烏利洋行,一家 「外國人開的出售鐘錶、相機的鋪子」。莊士敦也有記下此一幕, 說溥儀在店內「磨磨蹭蹭」,最終挑了一隻法國金懷表。當天這位末代 皇帝喬裝平民,但據莊士敦描述,他不小心喚了溥儀一聲「皇上」。 於是店內顧客員工紛紛竊竊私語,出門把話傳開,引來大量市民 圍觀。

莊士敦寫道:「他們生平第一次這麽目不轉睛注視著這位過去的 皇上。」由於無法擺脫張文治,溥儀假裝生病。莊士敦護送他到德國 醫院,成功甩掉這位管家。一場刺眼的沙塵暴籠罩北京,馬車在後門 迎接溥儀,把他送到日本大使館。

溥儀逃至天津日租界,過了六年寓公流亡生活。

29

[11]

Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi, From Emperor to Citizen. Translated by W.J.F. Jenner, Oxford University Press, 1987, 160. [12] Johnston, Reginald F., Twilight in the Forbidden City. Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1934, 419.

離京之路

Puyi and his family in The Zhang Garden, Tianjin.

溥儀和其家人在天津張園。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博

物院

‘The puppet emperor was crowned on a bitter March day in 1934. As court dignitaries in dragon gowns and fur hats bowed low, he sat on an ornate, bejewelled throne of ebony carved with dragons and orchids.’

30

Time Magazine

偽滿洲國時期溥儀武裝照片。 © Palace

Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院 31 1 9

Puyi in uniform during the Manchuria period.

Museum of The

3 2

The Puppet Emperor 傀儡皇帝

1945年10月2日溥儀在瀋陽機場被蘇聯

The Puppet Emperor

By 1932 Puyi had increased his dependency on the Japanese, agreeing to serve as ‘chief executive’ in Changchun, capital of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. Two years later the Japanese elevated him to ‘emperor,’ but he was little more than a figurehead.

Changchun was a far cry from the Forbidden City. In 1932 a New York Times reporter described the town as a single street stretching three miles from the railroad station and disappearing into ‘the endless Manchurian prairie.’ Puyi’s ‘none-too-elegant’ palace showed above prison-like walls.

‘In contrast to the royal barges on the great marble-bridged lotus lakes of Peking, the theatre whose orchestra pit was a pool designed to mellow the voices of actors and Chinese instruments, the polo and football courts, the riding paths, the rock and flower gardens, the towering artificial hills, Pu-yi has here for recreation facilities only a dirt tennis court,’ reporter Upton Close wrote. [13]

The puppet emperor was crowned on a bitter March day in 1934. As court dignitaries in dragon gowns and fur hats bowed low, he sat on an ornate, bejewelled throne of ebony carved with dragons and orchids. Yet the Japanese regarded him as nothing more than ‘a hollow-eyed figurehead to distract Manchurian peasants with the pomp of a royal court,’ Time magazine reports.[14]

Thus he aligned himself with what would be the losing side in World War II. On 15 August 1945, Japan announced its unconditional surrender, marking the dissolution of Manchukuo. Three days later Puyi abdicated a third time. He fled with several close relatives, including his brother, brother-in-law, and nephews. On their way to board on a flight to Japan, the Soviet army captured him at the airport of Mukden (Shenyang).

Despite the Chinese government's demands that the Kremlin return Puyi as a war criminal, the Soviet Union held him, first in the Siberian city of Chita, then in Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East.

傀儡皇帝

[13] Close, Upton. ‘AMID ALARUMS THE LAST MANCHU “RULES”: A Picture of Pu-Yi Against the Drab Background of the Capital.’ The New York Times, 11 Dec 1932, 126, 138.

[14] Time magazine, ‘MANCHUKUO: Orchid Emperor,” 5 March 1934. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,747105,00.html.

Puyi being transported by plane at Mukden (Shenyang), having been captured by the Soviet Red Army, 2nd October 1945.

紅軍截獲。

© Gettyimages: Hulton Archive

Aisin-Gioro Puyi as Emperor of Manchukou 滿洲國皇帝愛新覺羅·溥儀 Photo Courtesy Rubezh

1932年,靠攏日本的溥儀已完全依賴對方,期望有復辟皇權的 一天。溥儀答應為滿洲國的傀儡政權出任「執政」,在長春舉行就 職典禮儀。兩年後,日本當局讓溥儀登極成為「皇帝」,年號康德。衆所 周知,所謂皇帝,不過是由關東軍操控的傀儡君主而已。

長春離紫禁城甚遠。1932年,一名《紐約時報》記者形容長春為一條 「街道」,由火車站延伸三英里,消失在「一望無際的滿洲大草原」。

溥儀棲身的皇宮「設計庸俗」,猶如建築在監獄圍牆之上。

「與北京宏偉的大理石橋、荷花池上的皇家駁船、設計巧妙的 大劇院、馬球場、足球場、騎馬道、山水園林,以至千奇百趣的庭院賞

石相比,溥儀在這裏的娛樂設施,只有一個泥地網球場。」記者厄頓. 卡洛斯(Upton Close)這樣描述滿洲國皇宮。

1934年3月1日,寒氣凜冽,溥儀在當時改名「新京」的長春舉行登極典 禮。溥儀坐在烏木雕龍紋嵌寶寶座上,接受身穿龍袍、頭戴皮帽的 皇室貴族行鞠躬禮。然而,日本人認為溥儀不過是個「有名無實的 戲偶」,舉辦典禮的目的是「借用皇家盛事來分散滿洲農民對社會的 不滿。」《時代週刊》如此報導。

就這樣,在命運驅使下,末代皇帝與二次大戰的戰敗國結盟。1945年

8月15日,日本宣佈向同盟國無條件投降,滿洲國旋即瓦解。三天後, 溥儀在倉皇中宣讀滿洲國皇帝退位詔書,經歷他人生中第三次退位。

他與數名近親,包括弟弟溥傑、妹夫、侄兒、醫生和隨侍一起逃亡。 他們原打算登機前往日本,結果被蘇聯紅軍在奉天(瀋陽)機場截獲。

中國政府要求蘇聯把溥儀作為戰犯歸還,但當局沒有聽從,終究 把他關押起來。溥儀先後被囚禁在西伯利亞的赤塔,以及蘇聯遠東的 伯力。

33

‘I introduced myself in the Beijing dialect and said I would be the interpreter for emperor Puyi ... From the corner came a tall, thin Chinese man in glasses. He smiled showing wonderful teeth, ivory coloured, and stretched out his hands with very long fingers.’

Georgy Permyakov

The Emperor & the Interpreter 獄中翻譯

9 4 5

Puyi's Russian interpreter: Georgy Permyakov 溥儀的俄語翻譯格爾基.別兒面濶夫

35 1

Photo Courtesy Rubezh

©

偽滿皇宮博物院

Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime

The Boy in The Pond

In Tianjin Puyi lived a cosmopolitan life in the Japanese concession, out of the reach of Chinese authorities.

During that time, a curious twist of fate would bring about a meeting with his future Russian interpreter. At some point in the mid-1920s, Puyi met Georgy Permyakov, who was then a boy.

Born in the Soviet Far Eastern city of Ussurisk 7 December 1917, Permyakov and his family were among thousands of Russians who took refuge in China after the Russian Revolution in 1917. After the Bolsheviks seized his wealthy father’s business, the family fled to China in 1921, living first in Tianjin and then Harbin.

Permyakov grew up playing with Chinese children. ‘Therefore, the Eastern language for him was almost like a native language,’ MKRU Khabarovsk notes.[15]

During his Tianjin years Permyakov liked to play in a park near his home. One day while walking along the rim of a pond, he slipped and fell in the water. As he clambered out, soaking, he heard laughter. A young Chinese dressed in strange clothing was watching with glee, Permyakov later told his family. Hearing the young man’s laughter, Permyakov hammed it up and deliberately flung himself into the water again.

He came home ‘as wet as a chicken’ and explained what had happened, his family later said. And his mother told him, ‘You saw the Chinese emperor.’

Permyakov was not the only foreign child to glimpse the former emperor in Tianjin. In contrast with Puyi’s cloistered existence in the Forbidden City, he seems to have been out and about. Puyi biographer Brian Power, who was born in Tianjin in 1918, saw the emperor several times when he lived there as a boy. [16]

[15] MKRU Хабаровск , Гостайна переводчика последнего императора Китая Пу И, [Gostaina perevodchika poslednego imeratora Kitaya Puyi, The State secret of the translator of the last emperor of China Pu Yi], https://hab.mk.ru/articles/2014/10/10/gostayna-perevodchikaposlednego-imperatora-kitaya-pu-i.html, 10 October 2014, accessed 6 April 2023 [16] Power, Brian.

溥儀避居天津日租界期間,不受中國政府干預,有如身在小型國際 大都會。此時,命運讓末代皇帝與一位異國平民的人生軌跡首次 交曡。1920年代中期某日,溥儀與尚未成年的別兒面濶夫相遇。

1917年12月7日,別兒面濶夫在蘇聯遠東城市烏蘇裏斯克(雙城子)出 生。1917年俄國爆發革命,別兒面濶夫和成千上萬的俄羅斯人一樣, 逃往中國避難。別兒面濶夫父親本為一位成功商人,但被布爾什維克 搶奪生意,一家於1921年投奔中國,先住天津,後往哈爾濱。

別兒面濶夫自小就和中國孩子一起玩耍。「因此,東方語言對他來說, 可謂與母語無異」,《MKRU Khabarovsk》撰述。

別兒面濶夫在天津居住時,喜歡到離家不遠的一個公園裏玩耍。有一 天,他沿池邊行走,不小心滑倒,掉進水裏。渾身濕透的他爬出來時, 聽到笑聲。別兒面濶夫後來告訴家人,一個穿著奇怪衣服的年輕中國 人,高興地看著。別兒面濶夫聽到年輕人的笑聲,打起精神再次跳入 水中。

家人形容別兒面濶夫回家時「像掉進水塘的鴨子」一樣全身濕透,並 講釋了當時的情況。母親告訴他,「你剛遇到中國皇帝」。

別兒面濶夫並不是唯一在天津瞥見末代皇帝的外國孩子。溥儀在 天津期間可自由外出,與紫禁城的宮禁生活迥然不同。溥儀傳記作者 布萊恩.鮑爾(Brian Power)在1918年生於天津,童年時曾多次見過 溥儀。

37

池中男孩

The Puppet Emperor: The Life of Pu Yi, the Last Emperor of China. Peter Owen Publishers, 1986, 2.

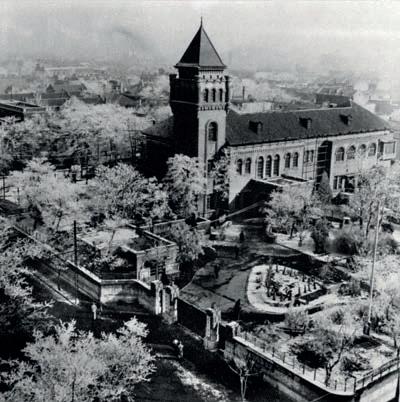

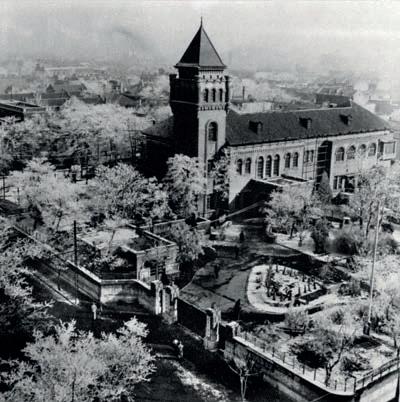

The Zhang Garden, Tianjin. 天津張園 © Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

The Emperor & the Interpreter 獄中翻譯

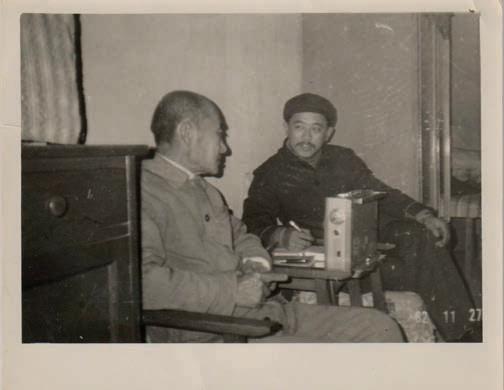

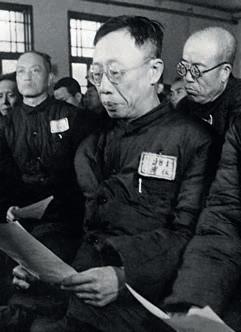

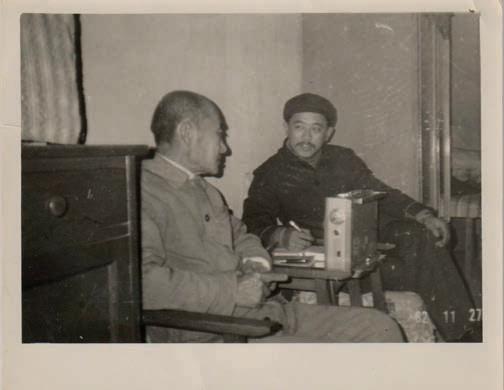

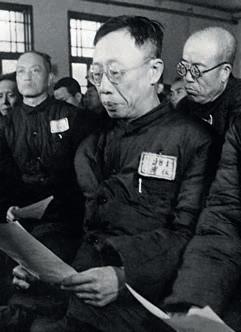

An encounter with a royal tends to leave an impression, and six decades later Georgy Permyakov still recalled the day he met Puyi in a Soviet prison camp.

It was December 1945. Permyakov—who was fluent in Chinese and Japanese— was working at Special Object No. 45 in Khabarovsk. This was not a nightmarish gulag of the sort memorialized by Soviet Nobel Prize-winner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn; rather, it was a spare facility in which Puyi was granted extraordinary privileges.

Permyakov found the imperial prisoner in a spacious room with flowerpots on the windowsill.

‘I introduced myself in the Beijing dialect and said I would be the interpreter for emperor Puyi,’ Permyakov writes. ‘From the corner came a tall, thin Chinese man in glasses. He smiled showing wonderful teeth, ivory-coloured, and stretched out his hands with very long fingers.’ [17]

Puyi wore an expensive brown woollen suit, and his hair was perfectly parted. Although he was approaching 40, his face was wrinkle-free and his posture as erect ‘as if he’d swallowed a ruler,’ Permyakov writes.

At 28 years old, the interpreter’s entire life had prepared him for this moment. After several years in Tianjin, his family had moved in 1927 to Harbin, where the expatriate Russian population ran in the tens of thousands. There he studied Chinese and Japanese, and from 1939-1945 he taught the two languages in the Soviet consulate.

As the Soviet Army entered northern China in August 1945, the Japanese arrested the consulate staff, planning to murder them, Permyakov recalls. But the quick victory of the Red Army save them.[18]

With the war’s end Permyakov moved to Khabarovsk. In Stalin’s time thousands of Russians who returned from Harbin ended up in the Gulag, but Permyakov possessed valuable linguistic skills. Upon his arrival at Special Object No. 45, the camp director, Maj. Anatoly Denisov, stunned the interpreter with the news that they held a special prisoner: the former emperor of China. Permyakov would interpret for him.

When the two men met Permyakov reminded the prisoner of the scene at the pond in Tianjin. Puyi said that he indeed recalled the boy, the interpreter’s family said. Because of that, trust was established between them.

In the camp Puyi did not live the life of a typical Soviet gulag prisoner, felling timber in the taiga, or sleeping in lice-infested barracks. Rather than march out before dawn to build canals or dig in mines, he got up at a leisurely 7:30 a.m. and breakfasted at 9 a.m. Privileged even in this unique camp, he was allotted his own room with a bed, a desk, a wardrobe, and even a phonograph, according to the Puyi Museum in Khabarovsk.[19]

[17] Permyakov, Georgy, Император пуи: пять лет вместе (‘Imperator Puyi. Pyat let vmeste’; ‘Emperor Puyi: Five Years Together’), Rubezh, No. 4 (2003), 292. [18] Permyakov, 'Emperor Puyi: Five Years Together’, Rubezh, 279. [19] Pu Yi Museum, Khabarovsk, Russia, “QR-12 Daily Routine,” https://puimuseum.ru/en/daily-routine/, accessed 4 March 2023

39

Puyi with Permyakov (right) and other Soviet officials. 溥儀,別兒面濶夫(右)和其他蘇聯官員們。

Photo Courtesy Rubezh

Puyi being transported by plane at Mukden (Shenyang), having been captured by the Soviet Red Army, 2nd October 1945. 1945年10月2日溥儀在瀋陽機場被蘇聯紅軍截獲。

© Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

He practiced tai chi chuan, offered Buddhist prayers, and washed his face and hands frequently. In his free time he read books and journals. From 2 p.m. to 6 p.m., he napped. At 6 p.m. he had dinner and chatted with others in the yard gazebo.

The prison administration gave Puyi and his household a garden to tend ‘in order to make us parasites do a little light labour,’ Puyi writes. He was mesmerized by the growth of his tomatoes, beans, eggplants, green peppers, and other crops.[20]

Because of his special status, Puyi was allowed to keep two suitcases and some European clothes, the museum notes. His companions, however, were not allowed this privilege and had to make do with minimal clothing.

If Johnston steered Puyi toward being a British gentleman, Permyakov’s focus was on teaching him to make his way in a communist state. Under Permyakov’s tutelage Puyi studied Russian and the communist doctrine. The former emperor delighted in learning lullabies and a drinking song called, ‘Kalinka,’ Permyakov writes. Permyakov assigned the prisoner him books to read, among them Problems of Leninism and History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Just as he had done in Manchukuo, Puyi shaped himself according to his new captors’ demands. He did not question Permyakov’s lessons about the evils of kings and capitalists, but certain communist teachings bewildered him.

‘Why don’t you like intellectuals?’ Puyi asked. ‘These people create the wealth of the country.’ [21]

Terrified of extradition to China, Puyi sought to stay in the Soviet Union. He hoped ultimately to migrate to the United States or the United Kingdom, as these were Soviet allies, Permyakov writes.[22] During the five-year confinement in the Soviet Union, Puyi made several verbal requests and three written applications to the local authorities, asking for permanent asylum.

[20] Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi, From Emperor to Citizen. Translated by W.J.F. Jenner, Oxford University Press, 1987, 326. [21] Permyakov, Georgy, Император пуи: пять лет вместе [‘Imperator Puyi. Pyat let vmeste’; ‘Emperor Puyi: Five Years Together’], Rubezh, No. 4 (2003), 293. [22] Permyakov, Georgy, ‘Emperor Puyi: Five Years Together,’ Rubezh, 293.

‘If Johnston steered Puyi toward being a British gentleman, Permyakov’s focus was on teaching him to make his way in a communist state.’

會見皇室成員,對一般人來說總是沒齒難忘。六十年後,別兒面濶夫 回望蘇聯監營中對溥儀的第一印象,仍是記憶猶新。

1945年12月,操流利中、日文的別兒面濶夫在伯力第45號收容所 工作。有別於諾貝爾文學獎得主亞歷山大.索贊尼辛(Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn)筆下極度殘酷的古拉格群島勞改營,溥儀所處的收容 所舒適得多,而且能讓他繼續享受皇帝的待遇。

別兒面濶夫發現溥儀在窗臺擺放盆栽花卉。別兒面濶夫憶述: 「我用北京腔自我介紹,告訴溥儀我是他的翻譯員。迎我而來的, 是一位高挑纖瘦、佩戴眼鏡、笑容可掬、牙齒白皙、十指幼長的 中國人。」

溥儀穿著昂貴的棕色毛料西裝,頭髮清晰分界。雖已年近四十歲, 但臉上毫無皺紋,腰背也很挺拔。別兒面濶夫寫道:「就像吞下了 一把間尺」。

這位負責為溥儀翻譯的二十八歲青年,仿佛前半生都在準備迎接 此刻。別兒面濶夫在天津居住數年後,隨家人於1927年搬到俄國僑民 達數萬人的哈爾濱。他在當地學習中文和日文,在1939–1945年於 蘇聯領事館任職導師,教授這兩種語言。

別兒面濶夫憶述,1945年8月蘇軍進入中國東北時,日軍逮捕了蘇聯 領事館的工作人員,計劃謀殺他們。幸好援軍及時趕到,保住使館 人員的性命。

戰後,別兒面濶夫移居至伯力。在斯太林時代,成千上萬從哈爾濱 回國的俄羅斯人,最終被關進勞動改造營管理總局(古拉格)。 但別兒面濶夫擁有非凡的語言能力,因此受到重用。當別兒面濶夫抵 達伯力第45號收容所時,營長阿納托利.傑尼索夫(Anatoly Denisov) 少校告訴他,營內關押了一名特殊戰犯——中國皇帝。

別兒面濶夫大為吃驚,但也準備就緒進行翻譯工作。

兩人見面時,別兒面濶夫重提他童年在天津池塘的狼狽一幕。別兒 面濶夫後人記述:「溥儀說他確實記得那個男孩。」二人冥冥中重遇, 立刻建立互信。

身處伯力收容所的溥儀,與古拉格囚犯的生活大相徑庭。他無需在 北方針葉林砍伐木材,也不用睡在長滿蝨子的監倉。據伯力溥儀 博物館介紹,溥儀沒有在黎明前出門修渠或挖礦,而是在早上 七時半悠閒地起床,九時吃早餐。即使被收監,這位末代皇帝也享有 特殊待遇。他有自己專屬的房間,內有一張床、一張書桌、一個衣櫃, 還有一台留聲機。

溥儀練習太極拳,虔誠拜佛,經常洗臉洗手。他在餘暇閱讀書籍、 雜誌,下午二至六時午睡,晚上六時吃飯,然後在操場涼亭與人聊天。

溥儀在自傳中寫道:「為了使我們這批寄生蟲,做些輕微的勞動, 收容所給我們在院子裏劃出了一些地塊,讓我們種菜。我和家裏人們 分得一小塊,種了青椒、西紅柿、茄子、扁豆等等。」種植過程讓他感到 「新奇」、「很有趣味」。

博物館指出,由於溥儀地位特殊,因此被允許保留兩個手提箱和 一些歐製服裝。然而,溥儀同被關押的其他近親沒有被賦予這種 待遇,只能穿著粗衣麻布。

若說莊士敦把溥儀塑造為一名英國紳士,那麼別兒面濶夫的角色, 就是為溥儀鋪砌共產主義之路。別兒面濶夫教授溥儀俄語及共產 主義理論,寫道:「末代皇帝樂於學習搖籃曲,以及一首名為《卡林卡》 (Kalinka)的下酒歌。」別兒面濶夫為溥儀選書閱讀,包括《列寧主義 問題》(Problems of Leninism)及《蘇聯共產黨歷史》(History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.)。

正如在不由自主的滿洲國,溥儀只能按照主人的要求來改造自己。 他沒有質疑別兒面濶夫口中皇帝、資本家的罪惡,但對某些共產主義 概念感到困惑。溥儀問:「你為什麼不喜歡知識份子?他們為國家 創造了財富。」

溥儀害怕被引渡回中國,試圖留在蘇聯。「他希望最終能遠渡蘇聯盟 友美國或英國」,別兒面濶夫寫道。在蘇聯的五年內,溥儀向蘇聯當局 提出多次口頭及三次書面要求,希望能獲得永久庇護。

41

若說莊士敦把溥儀塑造為一名英國紳士, 那麼別兒面濶夫的角色, 就是為溥儀鋪砌共產主義之路。

‘It is not dawn yet in the courtyard, the moonlight seeps through the south window. Sitting together by the lamp, the long silent mood endures. Dedicated to my comrade Permyakov in Tokyo on 19 August 1946

by Aisin-Gioro Puyi.’

Puyi's arrives Tokyo to testify at the Tokyo Trial in 1946. 1946年溥儀到達東京,在遠東國際軍事法庭出庭作證。

Courtesy Rubezh 43 1 9 4 6 A Testament to Friendship The Red Fan 扇中摯情

Photo

Puyi testifies at the Tokyo Trail in 1946. (Georgy Permyakov sat behind) 1946年溥儀到達東京,在遠東國際軍事法庭出庭作證。(別兒面濶夫坐在後面)

Photo Courtesy Rubezh

Photo Courtesy Rubezh

‘Bald-headed even in his twenties, Permyakov can be seen with Puyi and other Russians in video from the trial.’

A Testament to Friendship The Red Fan 扇中摯情

‘It is not dawn yet in the courtyard, the moonlight seeps through the south window. Sitting together by the lamp, the long silent mood endures. Dedicated to my comrade Permyakov in Tokyo on 19 August 1946, by Aisin-Gioro Puyi.’

With those words, Puyi turned a simple fan into a unique collector’s item of extraordinary value. Decorated with white flowers and a peak that resembles Mount Fuji, the Puyi fan’s central motif is (with a dash of historical irony) typically Japanese.

This is because Puyi inscribed the fan as a gift to Permyakov while they were in Tokyo. ‘The handwriting, brushwork, style and manner of the inscribed literature confirmed that it was written by Puyi,’ Mr. Wang Wenfeng, author and researcher for the Palace Museum of the Manchurian Regime, writes in an internal report for Phillips. ‘Little of Puyi’s calligraphy is known to exist. This fan serves as an extremely rare—and in all aspects marvellous—example.’

The fan has its origins in one of the major events of post-war Japan: the International Military Tribunal of the Far East, known as the Tokyo Trials. From 1946–1948, the Allied victors, including the Soviet Union, tried 28 Japanese Imperial Army officers and government officials on charges of war crimes.

A Soviet delegation that included Permyakov accompanied Puyi to Tokyo in August 1946. Bald-headed even in his twenties, Permyakov can be seen with Puyi and other Russians in video from the trial.[23] In his testimony Puyi portrayed himself as a powerless pawn of the Japanese, forced to adopt the Shinto religion and unable to rule his ostensible realm.

This collection includes a note, dated 4 April 2003, in which Permyakov relates the origins of the fan. After Puyi’s second day of testimony, on the evening of 19 August 1946, the interpreter sat with the prisoner in the garden of the Soviet embassy villa in Tokyo. Puyi was a ‘decent poet,’ Permyakov would recall. He asked the deposed emperor to compose poems on two fans.

Puyi inscribed a red fan for Permyakov and a blue one for the interpreter’s wife, Rimma. The couple eventually gave Rimma’s fan to the USSR Academy of Sciences, but they kept the red one.

Puyi inscribed the surface with a wuyan jueju (five characters quatrain), a classical Chinese poetry format with four lines to a stanza, each line consisting of five characters, Mr. Wang Wenfeng says.

By this time Puyi had spent only a year in the Soviet Union and had little understanding of the government’s attitude toward him, Wang states. No doubt he sought to curry favour by offering precious gifts such as this fan with his personal inscription.

45

[23] ‘Exclusive video of Emperor Puyi's Testimoy [sic] At The Tokyo Trials,” YouTube, uploaded by 298, 6 December 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=49NY-KZBdis.

Despite his lofty status as emperor, Puyi had been known to take a pen or brush in hand on other occasions in his life. During the Tokyo trials, the ex-emperor, eager to please his Soviet masters, agreed to sell his autographs. According to the Russian documentary Kitayskaya Igrushka Diktatora (‘Chinese Toy of the Dictator’), the Russians sat their prisoner at a table and had him sign his name, like a sports celebrity, for anyone willing to fork out cash.[25]

Composing poetry—as well as inscribing a fan—was not out of character for Puyi. Johnston notes that his former pupil ‘has an inherited poetic gift and has written much classic verse and even some of the modern verse.’ Puyi himself notes that from childhood he had loved writing poetry. And it was not unlike him to try to flatter the powerful figures in his life by composing verses. In April 1935, while traveling by ship to Tokyo, a seasick Puyi wrote a ‘toadying poem’ on Sino-Japanese friendship.[26]

More significantly, Puyi used the gift of fan to commemorate a turning point in one of the most important relationships in his life. As he would later do for Permyakov, Puyi inscribed a fan for his Scottish mentor and friend, Reginald Johnston, when the imperial tutor left China. In September 1930 Johnston travelled to Tianjin to bid his former pupil farewell. Early on the morning of the 15th, Puyi dropped by Johnston’s hotel bearing a fan on which he had copied an ancient Chinese poem of farewell. Puyi took his former teacher in his motorcar to the wharf. He even went aboard and sat in the Scotsman’s cabin until the last moment. The young man then returned to his vehicle. During the half-hour it took the steamer laboriously to turn around in the harbour, Puyi ‘sat in his car on the wharf and remained there as long as the ship was in sight.’

The farewell poem, as translated by Johnston, carries hints of the poetic view of friendship Puyi would later express on the Permyakov fan:

The road leads ever onward,

And you, my friend, go this way, I go that.

Thousands of miles will part us—

You at one end of the wide world, I at the other.

Long and difficult is the journey—

Who knows when we shall meet again? [27]

[25] ‘The Chinese Toy of the Dictator’ Китайская игрушка диктатора, [Kitaiskaya igrushka diktatora], YouTube, uploaded by Аманжол, [Amanzhol] 10 June 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GJmH3my7jhI

[26] Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi, From Emperor to Citizen. Translated by W.J.F. Jenner, Oxford University Press, 1987, 280. [27] Reginald F. Johnston, Twilight in the Forbidden City. Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1934, 447."

小院夜未央,明月透南窗。 相伴燈前坐,清意正悠長。

一九四六年 八月十九日於東京 贈與別兒面濶夫同志 愛新覺羅溥儀

一首言淺意深的詩句,令紙扇搖身一變,成為極具意義的非凡瑰寶。 此扇以紅地為背景,中心繪有一座貌似日本富士山的山峰,一邊 以迎風飄揚的櫻花襯托。種種圖案,構成一道典型的日本風景 (卻隱含歷史的諷刺意味)。溥儀在東京時,把紙扇作為禮物贈送 別兒面濶夫。近代史學者兼偽滿洲皇宮博物院副秘書長王文鋒, 為富藝斯撰寫了一份內部研究報告,當中指出:「從字跡,用筆習慣, 風格上來看確是溥儀所寫。溥儀傳世的墨蹟十分有限,足見此扇面之 珍貴。」紙扇見證轟動全球的歷史時刻——遠東國際軍事法庭,亦即 東京審判。從1946至1948年,包括蘇聯在內的盟軍戰勝國以戰爭 罪名,在東京向二十八名日本皇軍軍官及政府官員進行審判。

1946年8月,由別兒面濶夫在內的蘇聯代表團陪同溥儀前往 東京。從審判的錄影片段中所見,二十多歲光頭的別兒面濶夫、 溥儀以及其他蘇聯軍官在一起。在溥儀在陳詞中以日本人的棋子 自居,聲稱被迫改信神道教,是個沒有權力的皇帝。

藏品中涵蓋一張別兒面濶夫寫於2003年4月4日的筆記,當中記載了 紙扇的由來。據筆記所述,溥儀在1946年8月19日晚,即第二天作證後 的夜晚,與別兒面濶夫於東京的蘇聯大使館別墅花園內坐在一起。

別兒面濶夫形容溥儀為一位「儒雅的詩人」。他邀請這位愛好作詩的 末代皇帝在兩把扇子上題詩。溥儀欣然答應,分別在一把紅地紙扇上 為別兒面濶夫題詩,以及一把藍地紙扇上為其妻莉瑪(Rimma)題詩。

夫婦二人最終把莉瑪的藍扇捐贈蘇聯科學院,只保存了紅扇。

扇面題字的內容,如王文鋒所說:「是一首五言絕句」。他又分析溥儀 此舉背後動機,提出「溥儀此時方到蘇聯一年時間,尚未完全弄清 蘇聯方面對他所持有的態度,也許是出於討好奉承的心裏為他的 蘇聯翻譯別兒面濶夫寫下了這個扇面。」

溥儀雖貴為“天子”,卻有著書生文人的行徑,習慣隨身帶備紙筆。 在東京審判期間,這位末代皇帝急於取悅蘇聯,樂意出售他的親筆 簽名。根據俄羅斯紀錄片《獨裁者的中國玩具》(Kitayskaya Igrushka Diktatora)拍下一幕,溥儀坐在桌前,像體育名人滿足球迷一樣, 為願意掏出鈔票的蘇聯人簽上大名。

作詩、題字,對溥儀來說順理成章。莊士敦曾經形容溥儀「與生俱來 的賦詩才華,能駕馭古典與現代詩體,創作甚豐」。溥儀曾說,他從小 就喜歡寫詩。若說他用詩歌來奉承權貴,也不無道理。1935年4月, 溥儀成偽滿洲國皇帝後首次訪日,當船隻從大連開往橫濱時,溥儀 為「日滿親善」作詩。溥儀在《我的前半生》中憶述「記得我在這次暈頭 轉向、受寵若驚的航程中,寫下了一首諂媚的四言詩」,幾天後「又在 暈船嘔吐之中寫了一首七言絕句」。 更重要的是,早在為別兒面濶夫題字贈扇的許多年前,溥儀已作過 類似的舉動,在人生極為重要的關頭,向亦師亦友的恩人道謝。 1930年9月,莊士敦在返回英國的前夕,特意到天津向他的前學生 告別。15日清晨,溥儀帶著一把紙扇來到莊士敦下榻的飯店。莊士敦在 《紫禁城的黃昏》記述道別一幕:「皇上一大早就來到我住的飯店, 一直和我在一起,直到我必須登船的時候為止。我們一起乘他的汽車 去碼頭……航行將近半個小時,他一直坐在停在碼頭的汽車上, 直到船隻從他的視野中消失為止。」這首離別詩正像莊士敦翻譯的, 承載著相似於別兒面濶夫扇面的友情詩意:

行行重行行,與君生別離。

相去萬餘里,各在天一涯。

道路阻且長,會面安可知。

47

Permyakov Memories

惜別後記

In his quest to stay in the Soviet Union, Puyi eagerly took on whatever chameleon disguise his captors required. He petitioned Stalin to be accept him in the communist party, allowing him to help build socialism in the USSR. Permyakov writes that the prisoner suggested a new role he might play.

‘Is the Soviet communist party a big party?’ Puyi asked. ‘Many millions.’

‘Are there any emperors in your party?’

‘Not a single one.’

‘Fantastic! I will be the first communist emperor.’ [28]

Unsurprisingly, a government that had executed its own royal family—the Romanovs— was uninterested in elevating a foreign ‘communist emperor.’

One curious aspect of Puyi’s life was his inability to care for himself. He had always relied on an army of servants for his every need. Lacking his retinue in Khabarovsk, he required his family to wait on him. They did not dare call him ‘emperor,’ Permyakov writes, but referred to him as ‘the Upper One.’ (By contrast with the imperial family’s caution, Permyakov did not hesitate to refer to Puyi by his royal title, huang shang. This was daring in these Stalinist times, even if his fellow Russians did not understand what he was saying in Chinese.) Puyi’s family paid him their respects when they entered his room each morning.

‘They bathed him,’ Permyakov writes. ‘They massaged him. They dried him. They almost spoon-fed him.’ [29]

Soon rumours spread that Puyi and the nephew who washed him were gay lovers, Permyakov writes. A hidden camera in the bathrooms disproved the gossip, but prison authorities banished most of Puyi’s entourage, leaving him without his primary servants—only his father-in-law and brother-in-law. Permyakov was away from the camp during this time. When he returned to Khabarovsk, he found the once-fastidious emperor in a dishevelled state, his shirt wrinkled and tie askew.

‘Puyi came to me and took my hand and put it to his lips and said, “Please return them,”’ Permyakov writes. ‘He was almost crying. Only then did I realize what had happened.’

Another Chinese reported that Puyi had been going to an upper floor and gazing out the window with a melancholy expression, as if considering throwing himself out. Permyakov felt a chill down his spine, for a scandal had ensued a year earlier when a Japanese general hanged himself. Puyi’s suicide would have caused an international uproar.

Permyakov urged the camp commandant to bring back Puyi’s nephews. ‘He has not learned how to comb himself, how to bathe, how to take care of himself,’ he told his superior. ‘He has a sick stomach. His nephew cooks special food for him.’

The authorities brought Puyi’s relatives back to Special Object No. 45. Permyakov gave Puyi two bottles of vodka to celebrate their return.

[28]

Permyakov, Georgy, Император пуи: пять

лет

вместе [‘Imperator Puyi. Pyat let vmeste’; ‘Emperor Puyi: Five Years Together’], Rubezh, No. 4 (2003), 304.

[29] Permyakov, ‘Emperor Puyi: Five Years Together’, Rubezh, 291.

溥儀積極尋求蘇聯庇護,欣然接受各式各樣的妥協。他請求斯大林 批准他加入共產黨,表示會協助蘇聯建設社會主義。別兒面濶夫記 述,溥儀曾構想他可扮演的新角色。

溥儀問:「蘇聯共產黨是一個龐大政黨嗎?」

別兒面濶夫答:「有好幾百萬黨員。」

溥儀問:「你們黨內有皇帝嗎?」

別兒面濶夫答:「一個也沒有。」

溥儀問:「太棒了! 我將成為首位共產主義皇帝。」

對於曾經處決羅曼諾夫王朝的蘇共來說,「共產主義皇帝」當然是 匪夷所思。

溥儀生為天子,婢僕成群,從未學過如何自理。在蘇聯時期,由於缺乏 侍從,他要靠家人伺候。別兒面濶夫寫道,在囚家屬都不敢稱他 「皇上」,而只叫「上邊」。(別兒面濶夫則不像他們小心謹慎,毫不猶豫 地稱呼溥儀「皇上」。雖然所內其他官員聽不懂漢語,但在斯大林的 專制時代,如此舉動相當大膽。)溥儀家屬每天早上進入他的房間 請安。

別兒面濶夫寫道:「他們給溥儀洗澡、按摩、乾身,而且幾乎是用 勺子喂他進食。」

別兒面濶夫又述:「很快便有謠言說,溥儀和給他洗澡的侄兒是同性 戀戀人。」這些流言蜚語,被浴室裝有的一個隱蔽攝錄機推翻,但所方 仍是調走了溥儀大部分隨行親屬,只留下岳父和妹夫。 此時,別兒面濶夫短暫離營。當他回到伯力,即發現曾經神采飛揚的 獄中皇帝蓬頭垢面,衣衫不整,領帶歪斜。

別兒面濶夫再述:「溥儀走到我面前,拉著我的手放到他唇上說: 『請把家人還給我。』他幾乎要哭。直到那刻,我才意識到發生了 什麼。」

據說獄中一名中國囚犯曾經目睹溥儀多次走上高處,神情憂鬱地 凝望窗外,似乎在考慮著一躍而下。別兒面濶夫聽得脊背發涼。 一年前,一位日本前軍官上吊自殺。假若溥儀輕生,國際社會定會 一片譁然。

別兒面濶夫懇求所長把溥儀的侄兒送返同一監營,說:「他不會梳髮, 不懂洗澡,完全不能自理。他有胃病,需靠侄兒特別照料膳食。」

當局同意把溥儀親屬調回第45號收容所。別兒面濶夫給了溥儀 兩瓶伏特,慶祝大家重逢。

49

Examination of the handwritting of Puyi at the USSR Embassy Tokyo, 1946.

Photo Courtesy Rubezh 1946年在東京遠東國際軍事法庭驗證溥儀的字迹。

Puyi turned to Yuyan.

‘Do you still have the calendar-embedded platinum watch with you?’ he whispered.

‘Yes, I am wearing it,’ Yuyan answered.

‘Please take it off,’ Puyi said.

Aisin-Gioro Yuyan

51

1 9 5 0

The

A Parting Gift

Watch 饋贈名錶

A Parting Gift The Watch 饋贈名錶

From the day it was sold in 1937, Puyi’s Patek Philippe Ref. 96 Quantieme Lune wristwatch was of immense value. It is one of only eight such timepieces known (five of them platinum, two gold). Phillips researchers have traced the watch to a sale in Guillermin, a Parisian luxury store then located on Place Vendome, home of some of the world’s leading jewellers. Aurel Bacs, senior consultant with Phillips in association with Bacs & Russo, has a theory: that it reached China through Sennet Frères and allied businesses importing luxury goods to the Far East (see the auction catalogue).

The documentation is clear that Puyi brought this watch to a Khabarovsk prison camp known as Special Object No. 45 and gave it to Permyakov. This was where the deposed emperor and his entourage were held, along with Japanese officers and Manchurian ministers captured by the Soviet Red Army in 1945. Puyi, as well as the other ranking officials, was accused of being a war criminal.

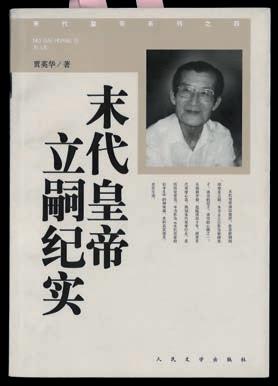

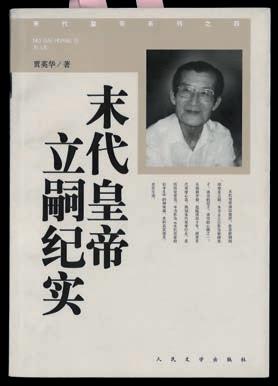

In his memoir, Yuyan, Puyi's nephew, states:

‘I was loyal to Puyi during our time in the Soviet prisons, so he rewarded me with a calendarembedded platinum watch which I was, undoubtedly, very familiar with. Back in the Manchukuo period, Puyi wore this exceptional watch day to day. I was particularly fond of it, not only because of its superb quality, but also the fact that it was such a personal item of Puyi!’ [30]

On 31 July 1950, two senior officials approached the former emperor’s cell. As Yuyan recalled, Permyakov interpreted, ‘The Soviet government has decided to let you return to China. You must swiftly pack your belongings and get set now. Hurry up!’

Puyi turned to Yuyan.

‘Do you still have the calendar-embedded platinum watch with you?’ he whispered.

‘Yes, I am wearing it,’ Yuyan answered.

‘Please take it off,’ Puyi said.

53

[30]

Jia Yinghua, Aisin-Gioro Yuyan: A Written Record of Heir Appointment by the Last Emperor, 124

‘Back in the Manchukuo period, Puyi wore this exceptional watch day to day. I was particularly fond of it, not only because of its superb quality, but also the fact that it was such a personal item of Puyi!’

Aisin-Gioro Yuyan

Aisin-Gioro Yuyan: A Written Record of Heir Appointment by the Last Emperor by Jia Yinghua. 《末代皇帝立嗣紀實》愛新覺羅‧毓嵒 作者:賈英華。

Without hesitation, Yuyan removed and returned his cherished platinum watch to Puyi, who passed it to Permyakov.

The Russian slipped the watch into his pocket.[31] Upon his death, he bequeathed the watch to his heirs.

The lower part of the dial of this watch had its coating removed. But why would someone do this to such a precious timepiece?

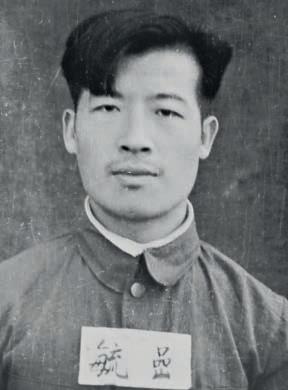

In 1982 Puyi’s long-time servant, Li Guoxiong, discussed this in an interview with Mr. Wang. (Puyi repeatedly mentions ‘Big Li’ in his autobiography, From Emperor to Citizen.) In 1924 the 13-year-old Li started working in the imperial palace as Puyi's servant, writes Mr. Wang, who interviewed Li more than 20 times in 1982. Li attended his master for 33 years, until 1957. A versatile craftsman, Li was Puyi's trusted handyman. The multitalented attendant knew how to take photographs, develop film, and repair cameras. His knowledge of mechanics and machinery also enabled him to fix Puyi’s watches and glasses.

In the Soviet Union, Puyi had too much time on his hands and was often bored, Li told Mr. Wang. He would idle away the time by painting, practising calligraphy, and copying literary allusions from folklore he had learnt. One day Puyi asked Li to open the watch and study its internal mechanisms.

Wondering if the dial was made of platinum, Puyi instructed Li to remove the surface to examine the layers. After Li removed the lower half of the dial, Puyi stopped him, commenting that the base colour suggested that the material was not platinum.

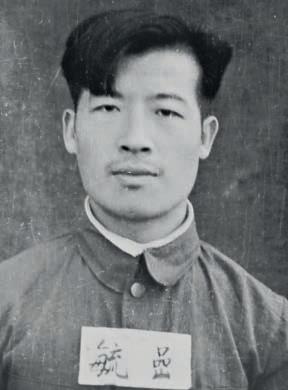

Yuyan and Li Guoxiong "Big Li" in prison camp. 毓嵒和李國雄(大李)在伯力 收容所。 © Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇 宮博物院

[31] Jia Yinghua, Aisin-Gioro Yuyan: A Written Record of Heir Appointment by the Last Emperor, 137

Yuyan and Li Guoxiong "Big Li" in prison camp. 毓嵒和李國雄(大李)在伯力 收容所。 © Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇 宮博物院

[31] Jia Yinghua, Aisin-Gioro Yuyan: A Written Record of Heir Appointment by the Last Emperor, 137

這枚百達翡麗型號96 Quantieme Lune腕錶,自1937年售出那天起, 已具驚人價值。它是目前所知傳世僅有的八例之一(五例為鉑金製, 兩例為黃金製)。富藝斯研究員經深入調查,追蹤到腕錶當時的交易 記錄,是來自專營奢侈品的法國高級名店Guillermin。該店坐落雲集 全球頂級珠寶商的巴黎凡登廣場(Place Vendome),是歷史悠久的 國際名錶舞臺。

富藝斯資深顧問Aurel Bacs推斷,腕錶疑經利威洋行及相關的歐美奢 侈品進口商引入中國。(請參閱拍賣目錄)

文件明確顯示,溥儀把這枚腕錶帶到伯力第45號收容所,最後交給別 兒面濶夫。1945年,蘇聯紅軍攻陷東北,打敗日本關東軍。溥儀宣讀退 位詔書,與近親及隨從計劃逃亡日本,途中被紅軍截獲俘虜,連同一 些日本軍官、滿洲國部長送入此收容所,以候審戰犯身份關押。

溥儀侄子毓嵒在回憶錄《末代皇帝立嗣紀實》中記述:

「在蘇聯時由於我對溥儀忠心耿耿,溥儀親手賞給找一塊鉑金日曆 手錶。這塊手錶我當然很熟悉,那是溥儀在偽滿皇宮時常戴在手上 的,不僅是那塊手錶品質非常好,我特別喜歡,那可是溥儀親自帶過 的啊!」

回憶錄又說,1950年7月31日,蘇聯伯力45號收容所所長及副所長 突然進入溥儀監倉,由別兒面濶夫傳譯:「蘇聯政府決定讓你們返回 中國。你們現在就收拾行裝,準備出發。你們可要動作迅速些。」

毓嵒記錄他們的如下對話。

溥儀輕聲問:「那隻鉑金日曆表,你還帶著嗎?」 毓嵒:「我帶著呢。」

溥儀:「那你先摘下來。」

「隨之我毫不遲疑的把那只帶著日曆的心愛的鉑金手錶摘了下來, 交到了溥儀手中。沒想到溥儀竟轉手把這手錶遞給了那位蘇聯翻譯 別兒面濶夫。他沒有拒絕,悄悄地擱在了口袋裏。」

腕錶錶盤的下半部塗層被移除。可是,為何有人這樣做呢? 1982年,王文鋒與李國雄進行的訪談中,對此有過交代。李國雄,是 溥儀自傳《我的前半生》多次提及的隨從「大李」。1924年,13歲的他入 宮被聘為溥儀的隨侍,直到1957年33年間,一直緊隨溥儀。王文鋒在 1982年內訪問了李國雄逾20次,形容他「心靈手巧,是溥儀身邊的 能工巧匠。他會照相、洗相、修理照相機、修手錶、修眼鏡,凡是修理 的活溥儀都會找到他。」

王文鋒引述李國雄:「在蘇聯期間,溥儀無所事事,閑極無聊,便去畫 畫,寫藝術字,抄寫一些世俗典故,來打發日子,還做出了許多無聊 怪異的舉動。有一天,溥儀拿著這塊鉑金手錶要李國雄打開來研究 研究它的構造功能。」

「手錶打開後,溥儀就問這錶盤是鉑金的嗎?並讓李國雄拿工具, 探個究竟。移除了涂層的下半部之後,溥儀說底盤都出來了,不是 鉑金的。」

Wang Wenfeng (on right) interviewing Li GuoXiong "Big Li"(on left) in 1982. 1982年,王文鋒(右 )採訪李國雄(大李) (左)。 © Palace Museum of The Manchurian Regime 偽滿皇宮博物院

55

Farewell

Puyi was no fool. He knew that giving his interpreter a wristwatch—however valuable— wouldn’t halt the repatriation process or change a superpower’s international policy regarding a prisoner wanted as a traitor and collaborator in his homeland. Rather, the gift, like the fan Puyi gave to Johnston, was clearly a thank-you to Permyakov for teaching him and protecting him—an expression of friendship.

‘Hurried by the Soviet officials while waiting for other inmates to pack up their luggage, Puyi was eventually hustled to the car parked by the camp entrance,’ Mr. Wang says. ‘The group was driven straight to the train station, where they soon boarded for the ride back to China. This farewell showed the relentless side of Permyakov as he strictly served his duties.’

Permyakov, however, says the good-bye was friendlier than that. Prison officials threw a farewell banquet for Puyi and his entourage in the cafeteria that evening. The emperor and his relatives sat at their own table, drinking beer and vodka as the camp’s new director, Capt. Asnis, thanked them for their discipline.

At the train station the Russians separated Puyi from his family and the Manchukuo ministers. Permyakov remained with the emperor. A convoy of soldiers guarded the train, fearing that the Soviet Union’s Cold War adversaries would create an exaggerated propaganda campaign if the emperor came to any harm. Despondent about his return, Puyi said nothing. Permyakov did his best to cheer up the prisoner.

‘The new Chinese authorities are totally different from Chiang Kai-shek,’ Permyakov told him. ‘The previous one liked shooting people. Mao Zedong is kinder. You’re facing a few years of re-education, and then freedom.’ [32]

Permyakov and Captain Shkuro, who commanded the military guard, dined with Puyi. Dinner came with a bottle of Cahors wine. The emperor and his interpreter sat at a foldable table by the window. Permyakov did his best to lighten Puyi’s spirits, singing Russian lullabies and telling funny stories in broken Russian and pidgin Chinese.

The next day, 1 August 1950, Permyakov rose early and found Puyi standing by the window in the corridor, staring out at the forest they were passing through. They breakfasted together and drank more Cahors. The two sang the drinking song ‘Kalinka.’ Permyakov again told a fable in broken Russian, drawing laughter from Puyi.

That evening, after passing Grodekovo station, the train rumbled through tunnel after tunnel until it reached the border station at Suifenhe.[33]

‘In the morning I told Xuantong that we are already in China,’ Permyakov writes. ‘He became pale.’ A colonel from the Soviet Ministry of Foreign affairs entered and asked Puyi to come out to the platform.

There, the Chinese surrounded their former emperor and led him away.

Recalls Permyakov: ‘Puyi was walking among them, proud and straight like a mast. He was holding his hands behind his back.

‘I never saw him again.’

Forever 後會無期

[32]

лет вместе

Permyakov,

Georgy,

Император пуи: пять

[‘Imperator Puyi. Pyat let vmeste’; ‘Emperor Puyi: Five Years Together’], Rubezh, No. 4 (2003), 307.

[33] Permyakov, ‘Emperor Puyi: Five Years Together’, Rubezh, 308.

溥儀即使留蘇心切,但也只能面對現實,明白饋贈諸如這枚名錶 瑰寶,也無法買通對方叫停遣返。更遑論當前面對的,是超級大國的 外交政策——協助盟國遞捕賣國叛徒。因此,這份厚禮,就像溥儀昔日 贈別莊士敦那把紙扇一樣,是末代皇帝向獄中恩人致謝,感激對方的 教導和保護,紀念一段誠摯友誼。

王文鋒講述「溥儀等人收拾完畢,在蘇聯人催促下,當即坐上了停在 門口的汽車,一直到了火車站,踏上了回國的路程」,從宣佈遣返、 監視離營、沒收財物,以至押解出境,「別兒面濶夫是公事公辦毫 不留情的。」

然而,別兒面濶夫的版本卻帶著一份親和。據他憶述,當晚收容所 官員在食堂為溥儀等人舉行了告別晚宴。溥儀及親屬、侍從們坐 在他們專屬的餐桌,喝著啤酒和伏特加,新任所長阿斯尼斯(Asnis) 對他們的良好紀律表示感謝。

在火車站,蘇聯局方把溥儀等人與同被遞送中國的滿洲國戰犯 分成兩批。別兒面濶夫被安排留在溥儀那邊。大批蘇聯隊軍守衛著 火車,以免溥儀一旦受到任何傷害,冷戰對手會借勢煽動輿論。

溥儀歸國的大局已定,在列車上惶然惆悵,默不作聲。別兒面濶夫 盡力開解他說:「新中國與蔣介石政府完全不同。國民黨人喜歡槍斃 異己。毛澤東則比較仁慈。你將接受幾年教育,便會重獲自由。」

別兒面濶夫、指揮軍事衛隊的史庫羅(Shkuro)上尉,與溥儀共度 晚餐,並享用一瓶法國卡奧爾葡萄酒。溥儀與別兒面濶夫坐在窗邊, 以打開著的摺疊桌作為餐桌。別兒面濶夫費煞思量,唱起俄羅斯 搖籃曲,用幽默的俄語、漢語說著故事,努力緩解溥儀的不安情緒。 翌日,即1950年8月1日,別兒面濶夫早起,看見溥儀倚在走廊窗邊, 盯著列車飛馳的廣漠原林。二人同吃早餐,又喝著卡奧爾酒,還哼起 下酒歌《卡林卡》。別兒面濶夫又用俄語講述一則寓言故事,引來 溥儀大笑。

當晚,列車經過蘇聯遠東濱海邊疆區的格羅捷科沃站,轟轟隆隆地穿 越一條又一條隧道,最終抵達中蘇邊境車站綏芬河。

別兒面濶夫聚述:「隔天早上,我告訴宣統皇帝,我們已經到達 中國了。」說後,「他馬上臉色蒼白。」蘇聯外交部的一位上校進來 車廂,請溥儀移步至月臺。

隨即中國人包圍了這位前皇帝,帶走了他。別兒面濶夫續說: 「末代皇帝走在人群中間,像參天桅杆一樣,鶴立雞群。他握著雙手, 放在背上。」

「他從此一去不返。」

57

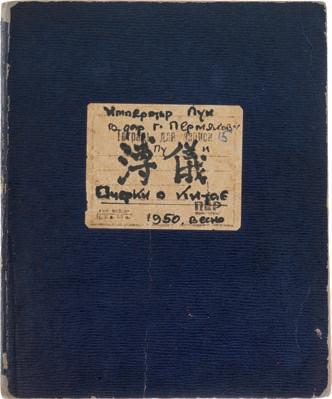

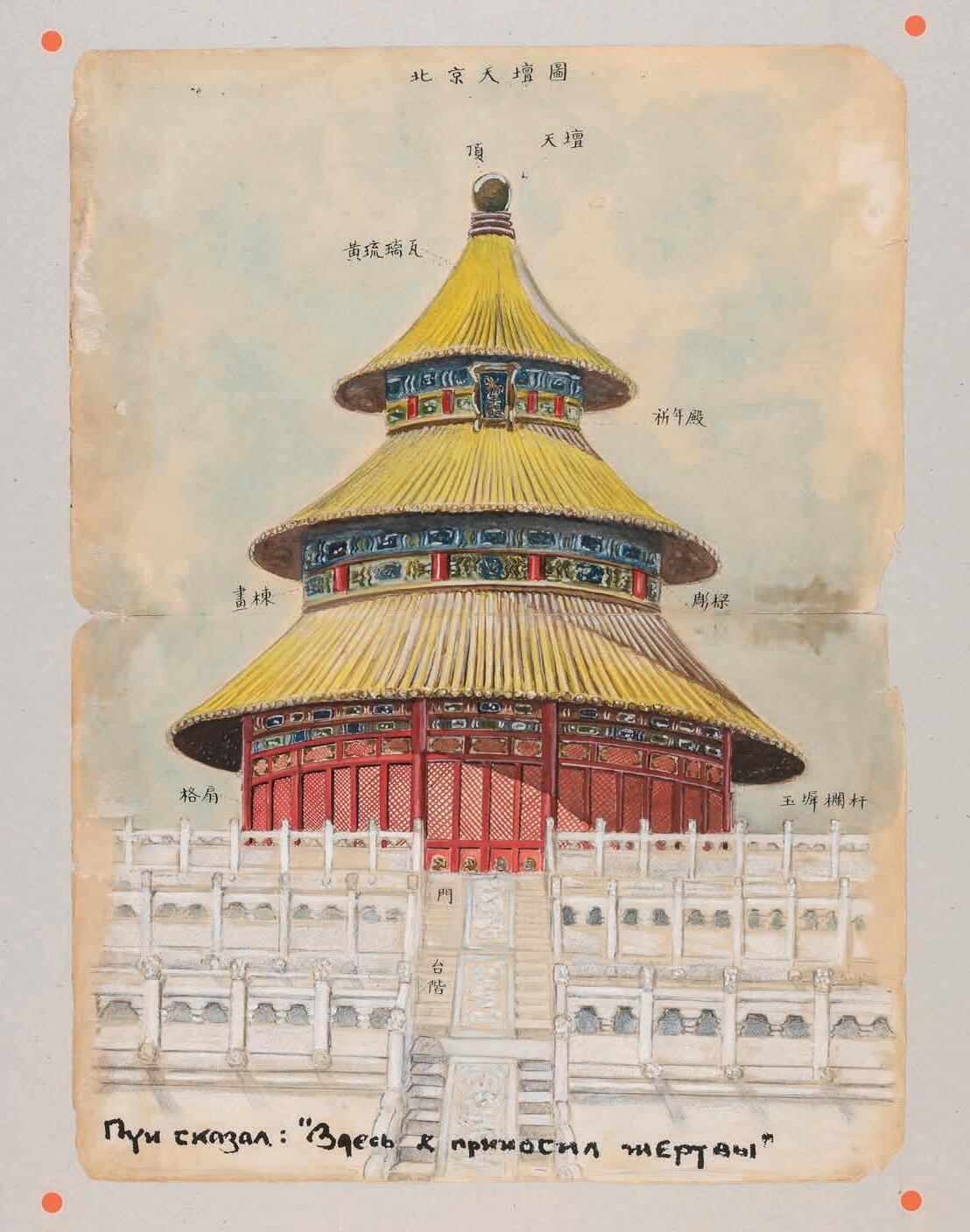

An Emperor's Eye-View of China 御筆遺稿

The collection includes a notebook in which Puyi discusses numerous aspects of Chinese culture, from childbirth to old legends. It is a fascinating window into Puyi’s thought, as if the emperor were peeking out a fortress arrow slot at what he knows or imagines to be the daily life of his realm.