Modern & Contemporary Art Evening Sale

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

Sale Interest: 30 Lots

View Sale

How to Buy

View Sale

How to Buy

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

Sale Interest: 30 Lots

View Sale

How to Buy

View Sale

How to Buy

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

Auction and ViewingAuctionViewing

AuctionAuction14 May 2024 5pm EDT

ViewingViewing

4 May - 14 May

Monday-Saturday 10:00am-6:00pm Sunday 12:00pm-5:00pm

432 Park Avenue, New York, NY, United States, 10022

SSaleDesignationaleDesignation

When sending in written bids or making enquiries please refer to this sale as NY010324 or Modern & Contemporary Art Evening Sale.

Absentee and TAbsenteeTelephelephoneBidsoneBids tel +1 212 940 1228 bidsnewyork@phillips.com

20thC20thCenturentury & Cy & ContemporarontemporaryAryArtt DeparDepartmenttment

Carolyn Kolberg

Associate Specialist, Head of Evening Sale, New York +1 212 940 1206 CKolberg@phillips.com

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

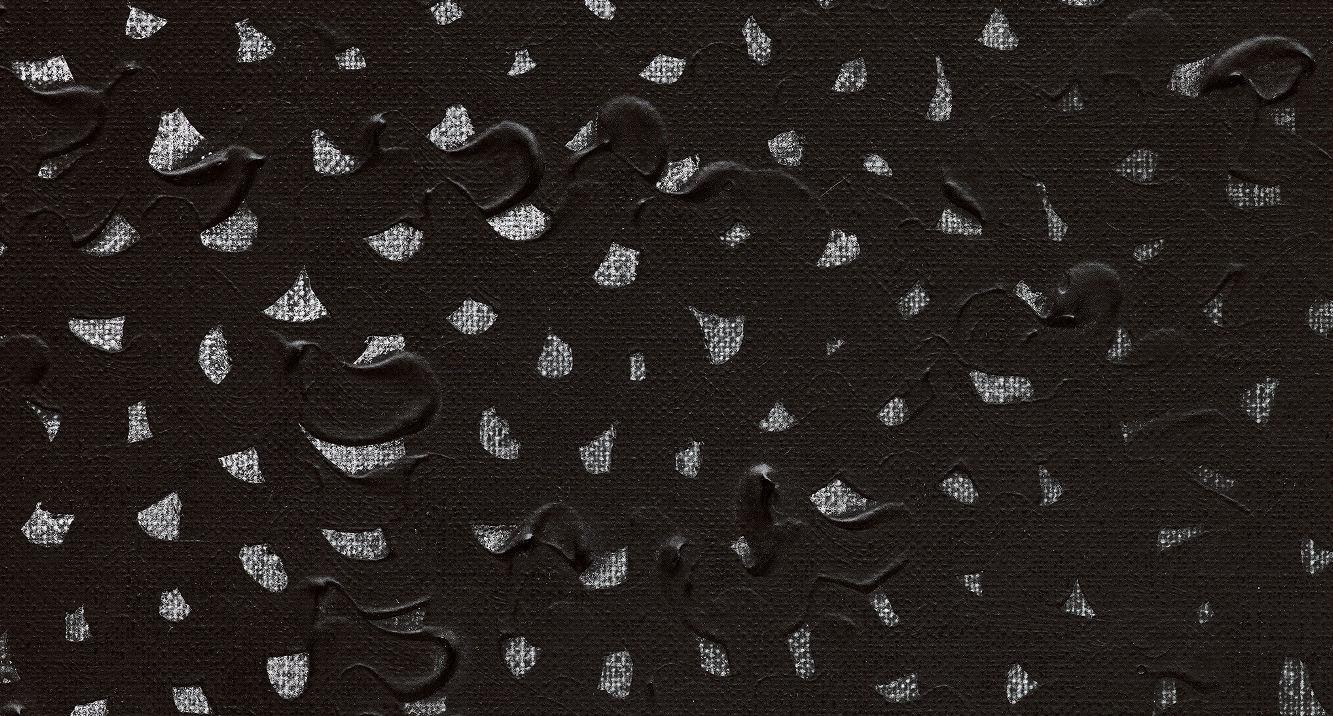

Yayoi Kusama

Nets in the Night (TPXZZOT)

EstimateEstimate

$1,500,000 — 2,000,000

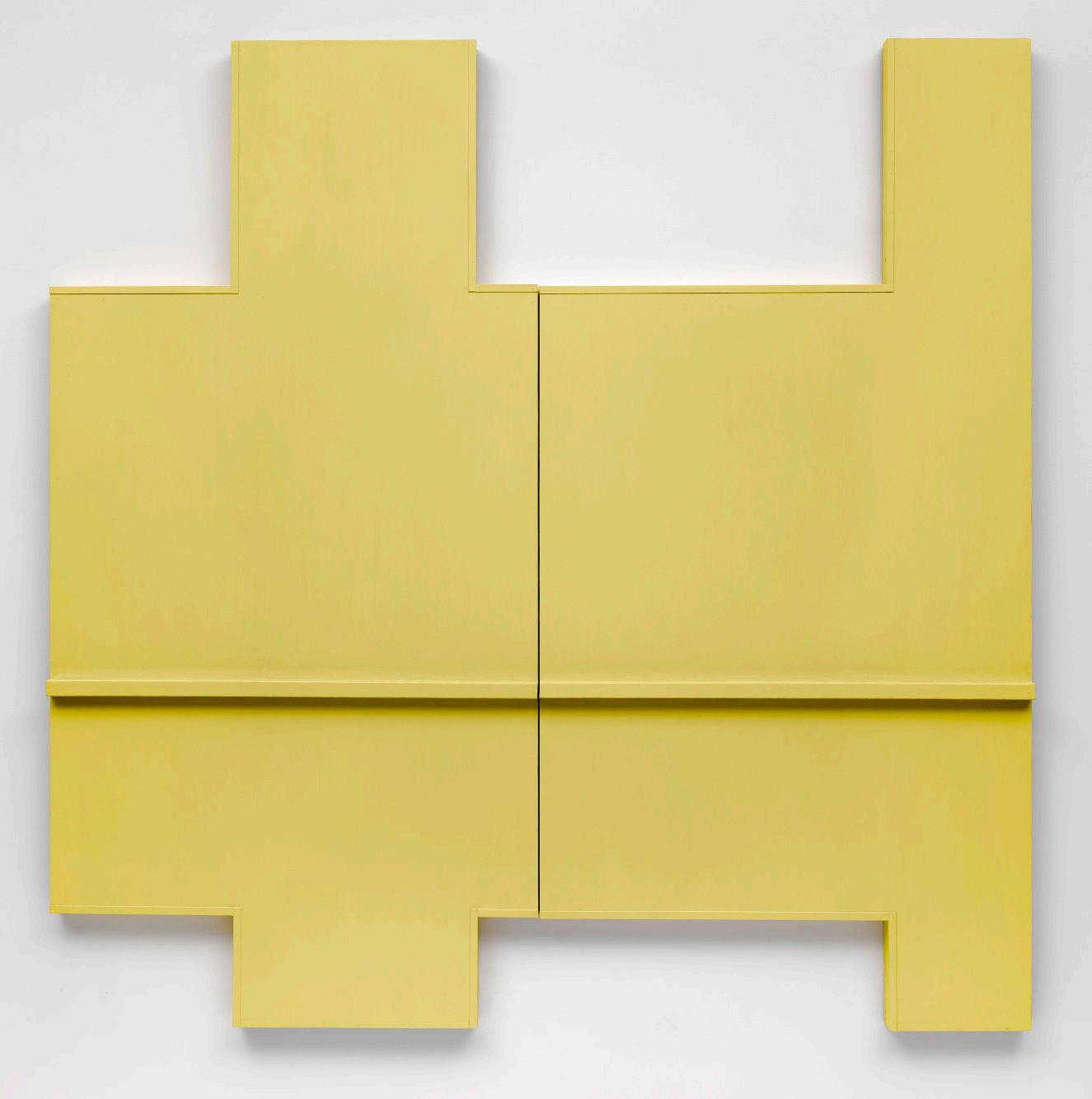

Donald Judd

Untitled

EstimateEstimate

$5,500,000 — 7,500,000

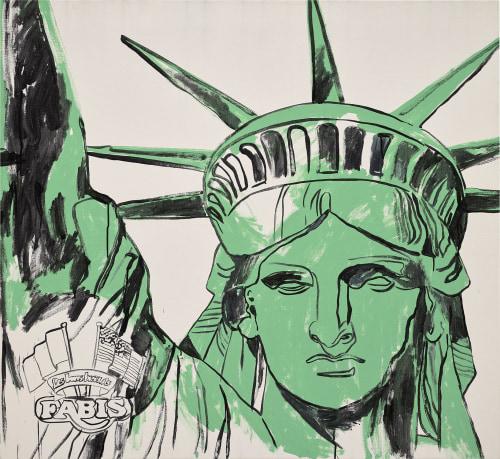

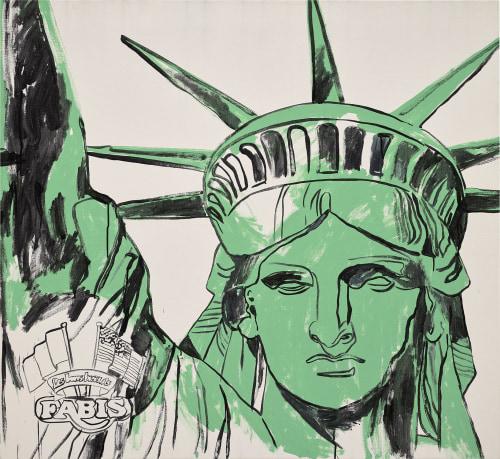

Statue of Liberty

EstimateEstimate

$800,000 — 1,200,000 17

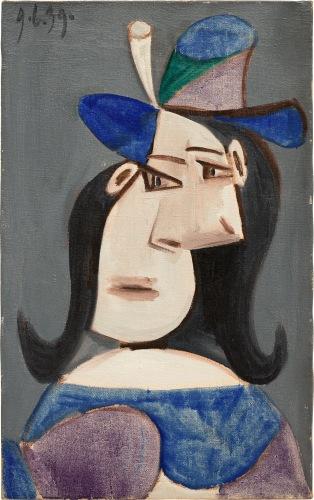

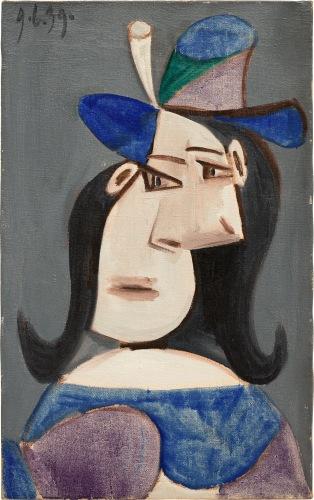

Buste de femme au chapeau

EstimateEstimate

$12,000,000 — 18,000,000

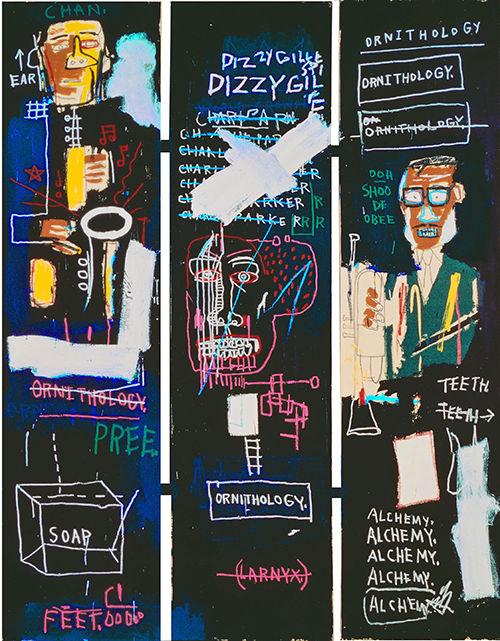

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Untitled (Grain Alcohol)

EstimateEstimate

$1,000,000 — 1,500,000

Robert Mangold

Three works: (i) 1/2 W Series (O…

EstimateEstimate

$600,000 — 900,000

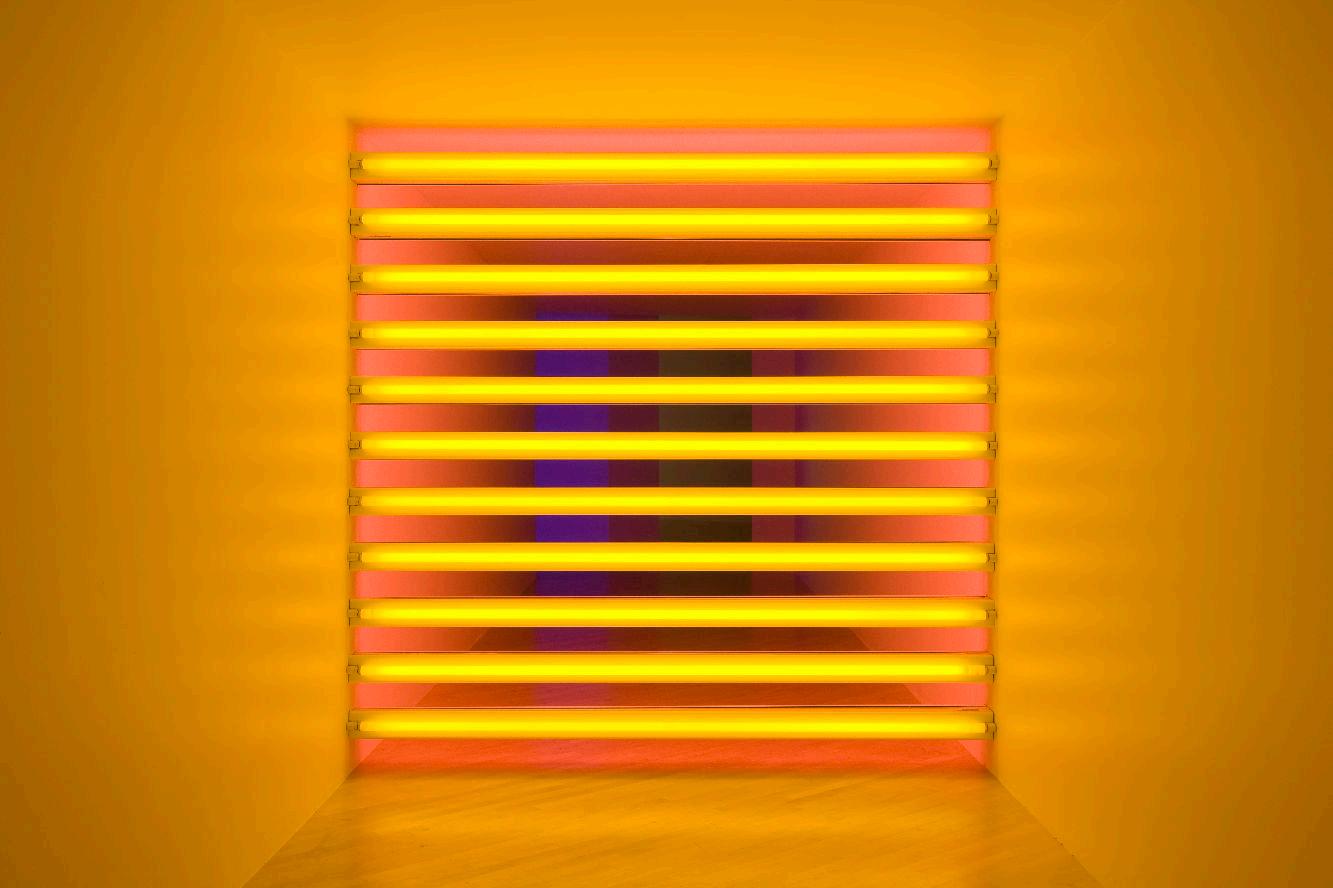

Anxious Red Painting Septembe…

EstimateEstimate

$1,000,000 — 1,500,000 15

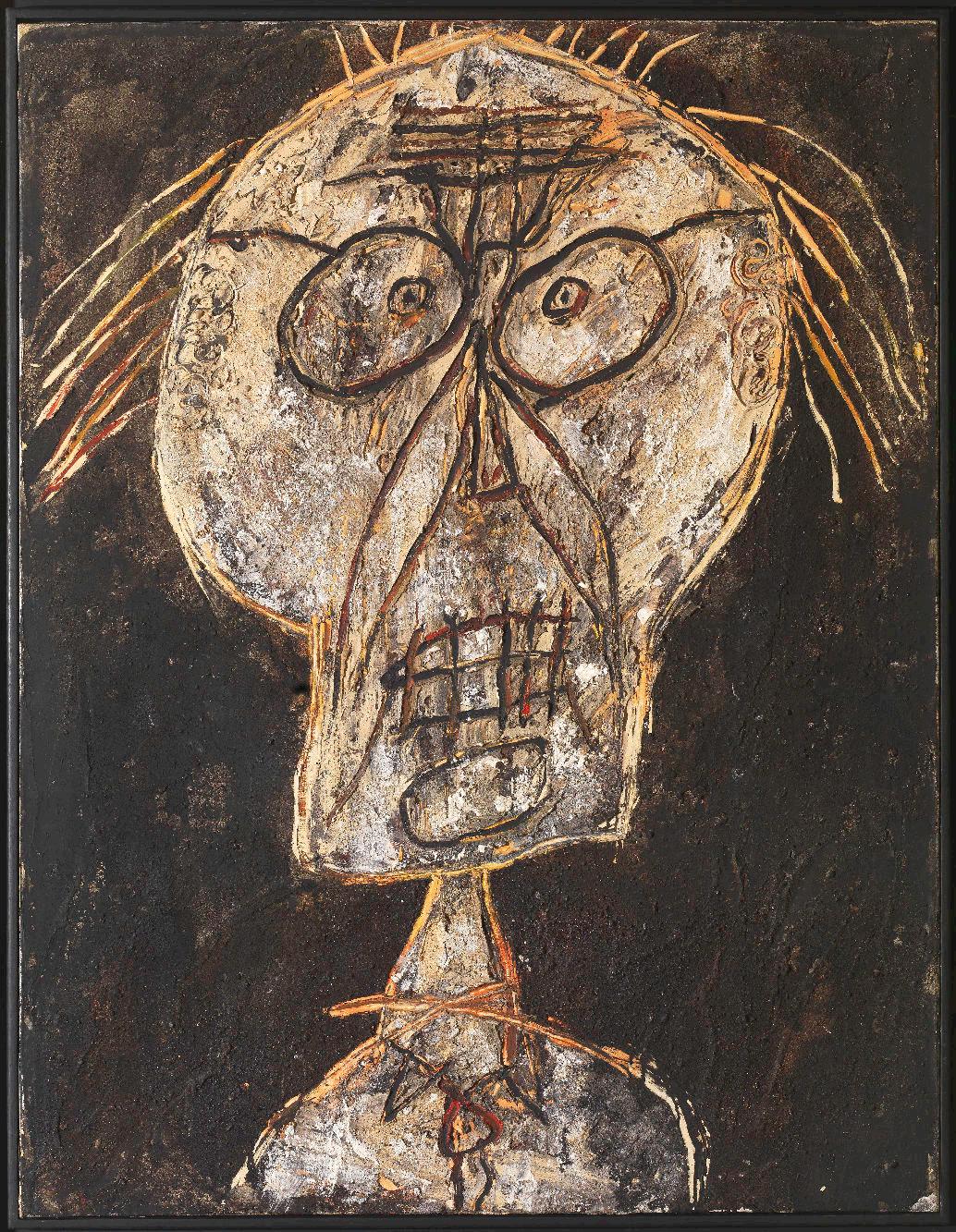

George Condo

Focusing on Space

EstimateEstimate

$1,000,000 — 1,500,000

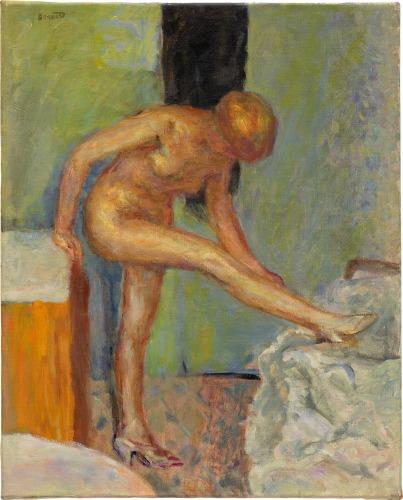

Nu de profil, jambe droite levée

EstimateEstimate

$600,000 — 800,000 20

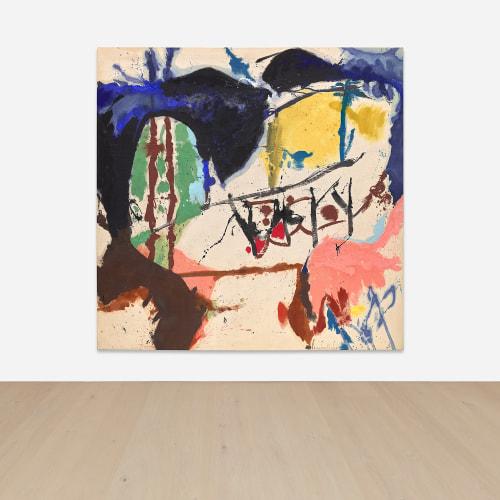

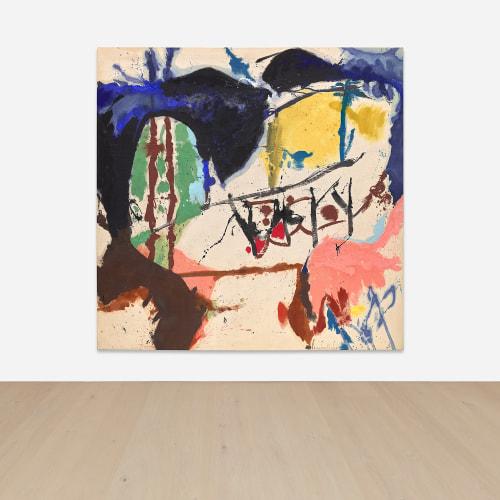

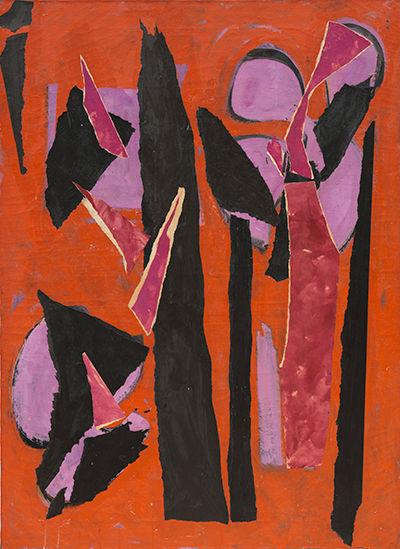

Grace Hartigan

Montauk Highway

EstimateEstimate

$700,000 — 1,000,000

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

Untitled (Boy with Glasses) signed “Noah Davis” on the reverse oil on canvas

10 x 10 in. (25.4 x 25.4 cm)

Painted in 2010.

EstimateEstimate

$150,000 — 200,000

Go to LotExecuted in 2010, Untitled(BoywithGlasses)serves as a poignant testament to Noah Davis’ mastery in capturing the essence of everyday life while infusing it with profound emotional resonance. This intimate portrait, executed with Davis’ characteristic blend of realism and introspection, encourages close looking. His small-scale paintings stand out as some of the artist’s most powerful works. As Helen Molesworth extolled, “Davis’ paintings are a crucial part of the rise of figurative and representational painting in the first two decades of the twenty-first century... His pictures can be slightly deceptive; they are modest in scale yet emotionally ambitious.”i Davis, recognizing the potency of his craft, intricately layers his painting—both in substance and concept. Employing a distinct dry paint application, he skillfully depicts a timeless portrayal of a single figure, in the tradition of classical portraiture masters such as Rembrandt and Velázquez, while also drawing inspiration from contemporary figurative artists like Lucian Freud and Alice Neel. There is a tenderness in the mundane and something familiar, imbued with an elusive, almost mystical aura.

“My paintings just have a very personal relationship with the figures in them. They’re about the people around me. I want people to read them like this whilst taking a meaning of their own from each work.” —Noah Davis

At first glance, the composition appears straightforward—a young boy, rendered in meticulous detail, gazes directly at the viewer through oversized spectacles. His expression, a delicate interplay of curiosity and vulnerability, invites contemplation, drawing us into his inner world. The scene is spare, and the palette subdued, leaving the viewer nowhere to look but into the boy’s eyes. Davis constructs a viewing experience that is intimate and without pretense. Yet, beneath the surface simplicity lies a subcurrent of narrative potential, as Davis deftly imbues each careful brushstroke with layers of meaning. Using a mostly dry paintbrush, Davis allows the texture of the canvas to push through, creating a soft and deeply atmospheric effect. This technique imbues the figure with a gossamer-like lightness that makes them seem as if they are not so much painted on the canvas as emerging from within its fibers.

The boy's glasses, the focal point of the composition, serve as a metaphorical lens through which Davis explores themes of perception and introspection. Through these lenses, the boy observes with apprehension and the hint of a smile, as if the looking goes both ways. Davis's nuanced handling of light and shadow further heightens the sense of intimacy, casting subtle nuances of emotion across the boy's features. In the quiet contemplation and understated elegance of the present work, Davis demonstrates his unparalleled ability to infuse the ordinary with a sense of profound significance. Through his masterful use of composition and color, he transforms a seemingly prosaic subject into a poignant meditation on youth, identity, and the human experience.

“[Davis’s] paintings are both figurative and abstract, realistic and dreamlike; they are about blackness and the history of Western painting, drawn from photographs and from life; they are exuberant and doleful in their palette… They tend toward the ravishing.” —Helen Molesworth ii

Alice Neel, ASpanishBoy,1955. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Artwork: © Estate of Alice Neel

Marlene Dumas, Cupid, 1994. Sammlung Moderne Kunst, Munich. Artwork: © Marlene Dumas

While Davis' subject remains anonymous, the idea for the painting was inspired by a high school yearbook photograph that achieved moderate viral acclaim. Davis has subtly altered the boy's clothing and youthful expression, making it challenging to recognize the early visage of Jonathan H. Smith before he became better known by his stage name, Lil Jon. This portrayal captures a less recognized phase of the now flamboyant American music producer and rapper, evoking a sense of personal history and transformation. Davis' canvases often depict Black figures in everyday scenes, drawing inspiration from family photographs, conversations with friends, pop culture, and literary sources. Despite these specific references, in paintings such as Untitled(BoywithGlasses),Davis intentionally leaves the sitter's identity open-ended, which is perhaps the very point; even in anonymity, the boy draws you in. Davis celebrates Black culture and creative legacy both close to

home and in the public eye, underscoring that even before fame, the subject was worthy of the spotlight.

Davis worked mostly from photographs, in the vein of artists such as Luc Tuymans and Marlene Dumas, reminding the viewer that images aren’t unequivocal. The painting intentionally muddies the source material, demanding it’s autonomy. In series like 1975, for instance, he drew from photographs taken by his mother, Faith Childs-Davis, during her teenage years on Chicago’s South Side in the 1970s.iii Other paintings reflect images of life in Los Angeles as captured by his wife, sculptor Karon Davis.iv Asked if his paintings are autobiographical, Davis responded, “They’re not necessarily from my life. They are a mix of things like an old painting I might like and something I’m obsessed with at the moment…Things will really come to me—a family member will come and give me a photo, or I’ll turn a page and just riff on something I see.”v

Davis has described his works as “instances where black aesthetics and modernist aesthetics collide,” and indeed, the present painting is rooted in traditional formal considerations such as line, color, and scale. However, while the anonymity of the subject and the lack of visual context imbue a permanence that allows them to exist outside of time and place, there is something decidedly contemporary in Davis' attention to materiality and the psychological resonance with which he infuses the Black figure. As writer Camila McHugh argues, “Davis’s paintings combine immediacy…with a timelessness—more precisely, a sense of being unstuck in time—that derives in part from his transtemporal source material.”vi

“The references are to things that are approachable and familiar, but the inferences are frequently quite mysterious. The images and figures are often familiar but unattainable, akin to futile attempts to recall a dream after waking.” —Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes

In 2016, Untitled(BoywithGlasses)was displayed at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle as part of YoungBlood:NoahDavis,KahlilJoseph,TheUndergroundMuseum—a two-person exhibition that placed Davis’ work in the context of an extended visual dialogue with his elder brother, artist and filmmaker, Kahlil Joseph. The title "Young Blood" originates from a name given to Davis by Joseph, serving as both an endearing term and a recognition of their shared beginning. The exhibition showcased the largest selection of their work ever displayed in a museum, spanning various mediums such as painting, sculpture, film, and installation. It delved into themes central to Davis's discourse, including access, class, and the establishment of independent art spaces.

The present work installed in YoungBlood:NoahDavis,KahlilJoseph,TheUndergroundMuseum,Frye Art Museum, Seattle, Washington, April 16 – June 19, 2016. Image: Mark Wood, Artwork: © Estate of Noah Davis

“Next to portraits of Charles and Emma Frye, and surrounded by a multitude of canvases of real and imagined worlds, is Davis’s paintingUntitled (Boy with Glasses)… It facesImitation of Wealthand The Underground Museum that would be founded in honor of Keven Davis.” —Helen Molesworth

Davis passed away in 2015 at the young age of 32. He played a pivotal role in the founding of The Underground Museum in Los Angeles, a groundbreaking cultural institution that has left an indelible mark on the city's art scene. In 2012, alongside his wife Karon, Noah envisioned a blackowned-and-operated art space that would transcend traditional gallery settings, providing a platform for underrepresented artists and fostering community engagement. “I like the idea of bringing a high-end gallery into a place that has no cultural outlets within walking distance,” he told the magazine Art in America the following year.vii With a commitment to showcasing museum-quality artwork in an African American and Latinx neighborhood, The Underground Museum became a beacon of inclusivity and creativity under the Davis’ visionary leadership, offering a vibrant space for artistic expression and dialogue. Through his dedication to democratizing access to art and culture, Davis' legacy lives on as an inspiration to artists and art enthusiasts alike, and works such as Untitled(BoywithGlasses)stand as a testament to the power

of his vision.

•In 2022, a selection of the artist's work was presented at the 59th Venice Biennale.

•Davis also featured in historic exhibitions such as 30Americans, organized by the Rubell Family Collection, Miami, which traveled extensively from 2008-2022, and Fore, the fourth in a series of emerging artist exhibitions presented by the Studio Museum, Harlem.

•His paintings are included in numerous permanent collections, including the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

•In September 2024, a retrospective of Davis’s work will be on view at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus, Potsdam, Germany.viii

i Helen Molesworth, “Noah Davis: Press Release,” DavidZwirnerGallery, New York, 2020, online

ii Helen Molesworth, “Noah Davis, An Introduction,” in NoahDavis. Exh. cat., New York, 2020, p. 7.

iii Exhibition text, “Noah Davis,” DavidZwirnerGallery, London, October 8—November 17, 2021, online.

iv Camila McHugh, “Noah Davis: David Zwirner, London,” Artforum, February 2022, online.

v Noah Davis, quoted in Ed Templeton, “Noah Davis,” ANPQuarterly, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 12-13, online.

vi Camila McHugh, “Noah Davis: David Zwirner, London,” Artforum, February 2022, online.

vii Noah Davis, quoted in Yael Lipschutz, “Links: Q+A with Noah Davis,” ArtinAmerica, March 7, 2013, online.

viii “Noah Davis: Biography,” David Zwirner Gallery, New York, Accessed April 12, 2024, online.

PrProovvenanceenance

Roberts & Tilton, Los Angeles

Acquired from the above by the present owner

ExhibitedExhibited

Seattle, Frye Art Museum, YoungBlood:NoahDavis,KahlilJoseph,TheUndergroundMuseum, April 16–June 19, 2016, pp. 7, 15, 127-128, 130 (illustrated, p. 15; installation view illustrated, p. 127)

LiteraturLiteraturee

“After an Untimely Death, an Artist's Legacy Lives On in the Museum He Founded,” HuffPost, May 1, 2016, online

Jeannie Yandel, “Why you should go see 'Young Blood' at the Frye (Hint: Beyonce),” KUOW, May 4, 2016, online (Frye Art Museum, Seattle, 2016, installation view illustrated)

NoahDavis, exh. cat., David Zwirner, New York, pp. 78-79, 173 (illustrated, p. 79)

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

Derek Fordjour

Numbers

signed and dated "Fordjour '18" on the reverse acrylic, charcoal and oil pastel on newspaper, mounted on canvas

72 x 48 in. (182.9 x 121.9 cm) Executed in 2018.

EstimateEstimate

$400,000 — 600,000

Derek Fordjour’s 2018mixed media painting Numberscritiques the commodification and exploitation of Black labor within the high-stakes arena of professional sports in the United States, serving as a poignant metaphor for the broader stratification of identity within American democracy. Numberswas prominently featured in the 2018 exhibition Sidelinedat Galerie Lelong & Co., New York, which was curated by artist Samuel Levi Jones and inspired by the 2016 protests of NFL players during the national anthem, spearheaded by quarterback Colin Kaepernick. The exhibition brought together artists responding to injustices experienced by people of color both on and off the sports field, including Melvin Edwards and Lauren Halsey, who engage with themes of race, representation, and the spectacle of athleticism throughout their larger practices. In Numbers, Fordjour eloquently illustrates the dichotomy of spectacle versus spectator, capturing a moment that, while seemingly routine, reveals the harsh realities of an industry that thrives on the physical assessment and valuation of its players.

“At an early age, a politician told me a sports analogy that exposed societal inequalities… Essentially, he explained that performance doesn't matter if there are two different sets of rules for the same game.” —Derek Fordjour

In Numbers, Fordjour employs a vibrant, celebratory palette that juxtaposes the darker implications of his subject matter. The scene depicted—an athlete being weighed in a room where men in suits scrutinize data on sheets of paper—transforms the canvas into a theater of power dynamics. These men, representatives of the managerial and evaluative class, hold sway over the athlete's professional fate, determining his value in a system where physical attributes are quantified and monetized. With his face turned away from the viewer, the athlete is stripped of individuality and reduced to numeric values such as weight, height, and sprint times, becoming a commodity within a highly lucrative sports industry.

Here, Fordjour not only captures the literal weighing of an athlete but also invokes the metaphorical weighing of human value within a capitalistic framework. The businessmen, distant yet controlling, embody a class that consumes and judges without partaking in the physical risks, much like the spectators in the stands or the broader electorate in a democracy. This separation between those who watch and those who perform—whether on the sports field or the socioeconomic stage—serves as a critical commentary on the roles and expectations that society imposes based on race, class, and other identities.

The present work comments on the spectator culture of American sports, where audiences consume performances without always acknowledging the personal and physical toll on the players. The bright colors and dynamic composition mask a moment of valuation, pointing to the wider societal obsession with rankings and metrics. Here, Fordjour reflects on the dual existence of athletes as both celebrated heroes and exploited laborers, their identities bifurcated by the public’s adoration and the industry’s dehumanization.

“Fordjour often depicts Black athletes and performers— dancers, riders, rowers,

Mickalene Thomas, ALittleTasteOutsideofLove, 2007. The Brooklyn Museum, New York.Artwork: © 2024 Mickalene Thomas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New Yorkdrum-majors —as strivers who navigate the ambiguities that come with their achievement, and the racial scrutiny that accompanies visibility in the mainstream culture.” —Siddhartha Mitter, New York Timesi

The metaphor extends to American democracy itself, a system purportedly founded on the ideals of equality and opportunity but often criticized for its hierarchical and exclusionary practices. Just as athletes are rewarded or penalized based on physical statistics, individuals in society are frequently assessed based on socio-economic metrics, racial profiles, and other arbitrary measures that dictate access to resources and power. Fordjour's use of sports as a lens to view these disparities highlights the performative and sometimes punitive nature of American social structures.

Moreover, Fordjour's choice of materials—acrylic, charcoal, oilstick and foil on newspaper mounted to canvas—adds another layer of critique. The newspaper, a medium that traditionally conveys information and authority, becomes the substrate for a narrative about the manipulation and control of information. By fragmenting and painting over this medium, Fordjour may be signaling the occlusion and manipulation of narratives, particularly regarding the labor and contributions of Black athletes.

Fordjour's painting process is characterized by its material complexity and rich textural elements. He begins with a foundational layer of paint on canvas or wood, then adds layers of cardboard tiles and newspaper. By alternating between the addition and subtraction of materials—by turns scraping surfaces, cutting and pasting shapes, and building up and the tearing away—Fordjour crafts his own unique topography in the vein of Mark Bradford’s monumental collages. He enhances these textured surfaces with charcoal and oil pastel, which results in multi-dimensional artworks that captivate and draw viewers into intricate visual narratives.

“Experimenting with ways to create more support ended up creating a new kind of surface. Now I react to something in every painting. I never just deal with the whiteness of the canvas. I'm always reacting to an embedded history in the work. There are about ten layers on every surface.” —Derek Fordjour

This textural technique also underscores the complexity of Fordjour’s themes. The physical layering of materials in Numbersserves as a metaphor for the multifaceted nature of human identity and societal roles. Each layer contributes depth while simultaneously obscuring the underlying elements, mirroring the way societal roles and labels define and often constrain individuals. Even Fordjour’s preferred periodical, TheFinancialTimes, is used not just for its distinctive pink color, but also for its content and implications in dialogue with Fordjour’s examination of commodification and racial inequity. “I was thinking about personal value and perceived value,” he says, adding that “The Financial Times is making an effort to differentiate itself from the pool of other newsprint with its distinctive color. The idea of individuation—the desire to distinguish oneself in the face of being stereotyped or grouped—has a tension that I identify with.”ii

Georges Seurat, CircusSideshow(Paradedecirque), 1887-1888. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.Image: © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Stephen C. Clark, 1960, 61.101.17

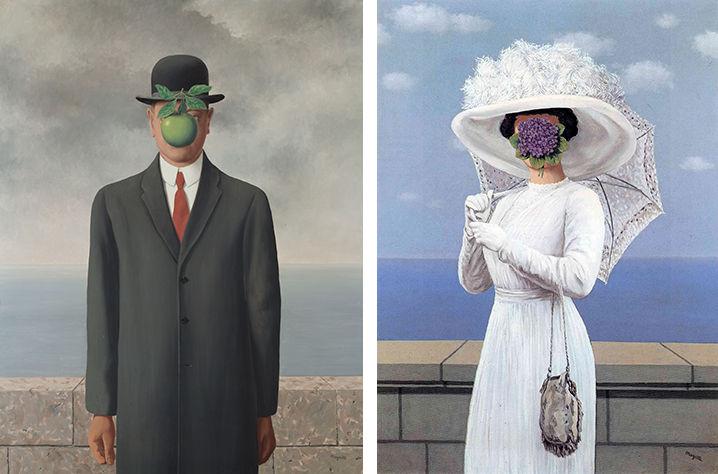

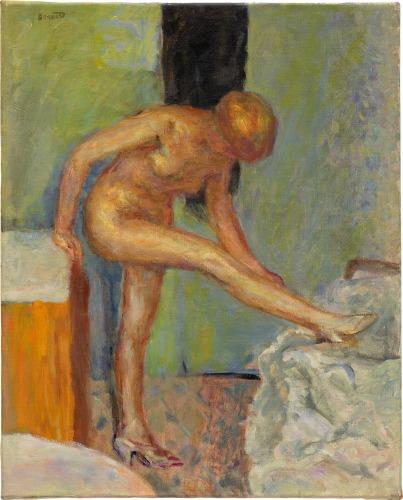

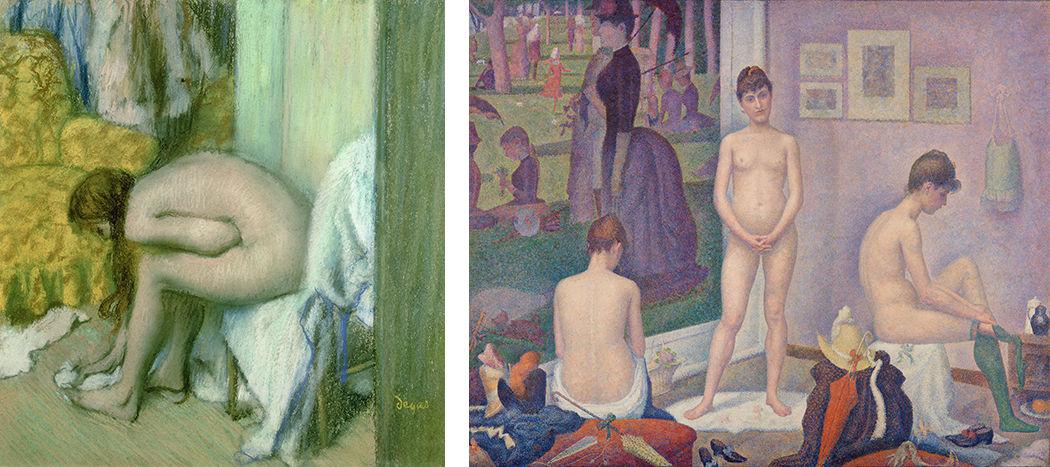

Pierre Bonnard, Lasortiedelabaignoire(GettingOutoftheBath), circa 1926-1930. Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation, Athens.Image: Bridgeman Images

Elucidating on his theory of optical color mixing, Fordjour credits much his works’ optical richness to his technique, saying “By working through various surfaces and allowing space for interaction, I can achieve a vibrancy. A lot of the colors in my work are situated next to each other. The eye does the work of putting them together.”iii Fordjour's mixed media painting technique mirrors postImpressionist strategies in its vibrant layering and juxtaposition of colors, which create vivid optical depth and dynamic interplay of light and shadow. This approach enriches the visual texture and evokes a strong emotional and sensory response, similar to that found in the works of artists such as Pierre Bonnard, whose broad, dry brushstrokes create a sense of dynamism, and Georges Pierre Seurat, known for his flickering colors and Pointillism. Fordjour’s nuanced synthesis of color and

form is strikingly illustrated in Numbers, where he blurs the lines between painting and collage, dream and reality.

“It’s in that space between real life and the unreal that we create.” —Derek Fordjour

i Siddhartha Mitter, “Derek Fordjour, From Anguish to Transcendence,” TheNewYorkTimes, November 19 2020, online

ii Paul Laster, “Derek Fordjour's Vibrant Interactions,” Ocula, June 23 2021, online

iii Ibid.

PrProovvenanceenance

Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

Private Collection

Acquired from the above by the present owner

ExhibitedExhibited

New York, Galerie Lelong & Co., Sidelined, January 5–February 17, 2018

LiteraturLiteraturee

Seph Rodney, “The Political Truths That Ground Our Athletic Heroes,” Hyperallergic,February 8, 2018, online (illustrated; dated 2017)

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

Freedom don't come for free

signed, titled and dated ""freedom don't come for free" 2021 Michaela Yearwood-Dan" on the reverse of the left canvas

acrylic, oil, gold leaf and Swarovski crystals on canvas, diptych

each 86 1/2 x 71 in. (219.7 x 180.3 cm)

overall 86 1/2 x 142 in. (219.7 x 360.7 cm)

Executed in 2021.

EstimateEstimate

$200,000 — 300,000

Executed in 2021, Michaela Yearwood-Dan’s Freedomdon’tcomeforfreeis the British artist’s largest work to come to market and explores the costs of liberty, both material and emotional. Through a diverse mix of acrylic, oil, gold leaf, and Swarovski crystals, Yearwood-Dan creates a visually striking representation that merges expressionism with contemporary mixed-media techniques. Both deeply personal and distinctly political, the present work embodies the artist’s expansive vision that reflects her own experience as a Black queer woman.

“My practice is oriented towards self-historicization, primarily through large-scale abstract painting… I create works that reference plants and poetry, and explore themes ranging from political dissection to personal narrative.” —Michaela Yearwood-Dan

Yearwood-Dan’s statement that her practice is "oriented towards self-historicization” reflects the artist’s commitment to exploring a range of themes: from political and collective to personal histories, she employs painting as a means to navigate and question the socio-political landscape and delve into the intimate corners of individual experience. Her preference for large-scale abstract painting, as evidenced in the present work, speaks to her ambition to confront and engage with vast topics, both spatially and conceptually. The sheer size of such works creates an immersive experience for the viewer, while also acting as a metaphor for the magnitude of the themes she tackles—here, the nature of freedom and the sacrifices it entails.

The references to plants and poetry within Yearwood-Dan’s works indicate a synthesis of the natural world with the literary.She merges the organic with the constructed to foster a dialogue about the transient nature of life and the quest for meaning. This intersection is particularly resonant in Freedomdon’tcomeforfree, where the presence of flora—as evinced by floral hues and sweeping brushstrokes that curve and swirl into organic shapes reminiscent of leaves, petals, and lush blossoms—connects to discussions around beauty and impermanence, as well as to

natural cycles of growth and decay. These elements serve as metaphors for human experience, while the extracts of poetry inscribed within speak to the human longing for liberation and the complexities of emotional expression. Like a call and response, fragments of loopy, disjointed handwritten cursive text question, “When will I finally figure out what it is to be free?” while others declare in capital letters “I’M STILL ME // MAYBE MORE SO THAN BEFORE / BUT I REFUSE TO / LEAVE ANY OF MY / IDENTITIES AT THE DOOR.”

The scattered lines of text, seemingly reflective and personal, introduce a narrative element and provide a glimpse into the artist's internal dialogue and emotional state. This textual component transforms the painting into a multidimensional expression, where the rhythm of twisting, spreading, swirling colors take on subtextual nuance in the context of language. Moreover, Yearwood-Dan’s use of contrasting colors and forms creates an almost landscape-like feel, offering a sense of depth and layering that one might associate with a densely packed garden or a crowded rose bush. This is turn contributes to the suggestion of plant-life and floral forms that is discernible through organic shapes and the way colors bloom and intermingle on the canvas, much like the natural growth patterns of flora.

Cy Twombly, TheRose(PartV),2008. The Broad, Los Angeles. Artwork: © Cy Twombly Foundation

Hilma af Klint, TheTenGreatest,No.3,YoungAge,GroupIV, 1907. The Hilma af Klint Foundation, Stockholm.

The addition of Swarovski crystals as surface elements serves as a form of what the artist calls “accessorization,” a technique that harkens back to Yearwood-Dan's upbringing in South London and her exposure to gold-inflected religious iconography within a Catholic educational setting. The embellishment is a nod to a broader art historical context that commenced with religious iconography and has since persisted across various cultures. Here, they signify affluence but also connect to a deeper history of spiritual and artistic expression. As seen in the present work, her compositions frequently feature a distinct void at their core, resembling a gateway. In a manner reminiscent of “grand frescoes and the Sistine Chapel and the movements of big skies and unearthly visions,” as she describes, her work echoes these majestic art forms while conveying a

far more intimate and personal sentiment. She articulates this personal aspect as the “diaristic, self-historicization of the emotions and feelings I’m going through.”i

Yearwood-Dan’s Freedomdon’tcomeforfreepossesses a Renaissance-like opulence. Her nuanced lines and sumptuous color evoke shades of Sandro Botticelli, while also revealing the influence of Black artists like Chris Ofili. In fact, it was her first encounter with Ofili’s work that inspired her to begin her journey as an artist. "Everyone talks about representation, but there are some moments of representation that do shake you to the core, and for me, it was discovering Chris Ofili at age 16 or 17," she explained.ii

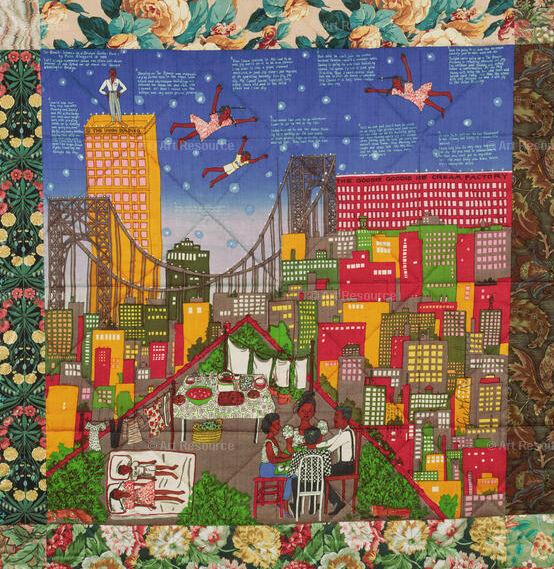

2024

Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Freedomdon’tcomeforfreeis not only a spectacle of visual and textual narrative but also a sophisticated interplay of the artist's personal and political insights, her cultural heritage, and her technical prowess. It is a vivid portrayal of the intrinsic, often exorbitant cost of freedom, both in a metaphorical sense and in its literal embodiment through the materials and labor that constitute the artwork. It challenges the viewer to introspect about the value of freedom in a world that often sees it as a commodity rather than an inalienable right. Through the layered abstraction and complex composition of this painting, Yearwood-Dan prompts us to contemplate the nature of freedom and the sacrifices made in its name, as conveyed by the visual stream of her consciousness.

CCollector’ollector’sDigestsDigest

•In October 2022, CopingMechanisms, 2021, sold through Phillips in London for £239,400 GBP, setting an auction record for the artist at the time of sale.

•Recent solo exhibitions include the 2023 presentation SomeFutureTimeWillThinkof Usat Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York and TheSweetestTaboo, staged in 2022 at Tiwani Contemporary in London.

•In Summer 2022, Yearwood-Dan created the site-specific installation LetMeHoldYou for QUEERCIRCLE charity in London, which provides a dedicated space for the LGBTQ+ community to gather.

•She has been awarded with and participated in a range of fellowships and residencies, including the third annual Great Women Artists Residency in 2021 at Palazzo Monti in Brescia, Italy, and Bloomberg New Contemporaries in Partnership with Sarabande: The Lee Alexander McQueen Foundation, London, in 2019.

•Yearwood-Dan's work is in the permanent collections of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami, and the Columbus Museum of Art.

i Tess Thackera, "Cultured | Beyond Their Lavish Aesthetic, Michaela Yearwood-Dan's Paintings Make You Feel," MarianneBoeskyGallery, New York, online.

ii Boesky, Ibid.

PrProovvenanceenance

Tiwani Contemporary, London

Acquired from the above by the present owner

ExhibitedExhibited

Nottingham, New Art Exchange, Laced:InSearchofWhatConnectsUs, October 30, 2021–January 8, 2022

LiteraturLiteraturee

Hannah Clugston, “Burps, branches and bold exploration – Laced/Cut & Mix review,” The Guardian, November 1, 2021, online (detail illustrated)

Lauren Dei, “The Black Feminine and Black Masculine Principles of Selfhood,” BlackBlossoms, December 9, 2021, online (New Art Exchange, Nottingham, 2021, installation view illustrated)

“‘Laced: In Search of What Connects Us’ at New Art Exchange in Nottingham,” TSAContemporary ArtMagazine, December 13, 2021, online (illustrated)

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

Barkley L. Hendricks Vendetta

signed "B. Hendricks" upper right; signed, titled and dated ""VENDETTA" 1977 BARKLEY L. HENDRICKS" on the overlap oil, acrylic and Magna on canvas 35 7/8 x 48 in. (91.1 x 121.9 cm) Painted in 1977.

EstimateEstimate

$2,500,000 — 3,500,000

“Everything is up for grabs in the creative arena, and I think it’s only a limited artist that limits his or her approach to using what’s available.” —Barkley Hendricks

From its attitude to its title,Barkley L. Hendricks’ Vendetta, 1977,makes a statement—one that is bold, straightforward, and decidedly provocative. Hendricks asserts his place within the lineage of the Old Masters with the very same gestures he uses to declare them obsolete. He takes their medium, their methods, and their ideas of memento, and flips the message, declaring a new order in which ideals of whiteness and its attendant notions of beauty are ancillary, and the Black figure—in this case, the Black female figure—is in the foreground. To do this within the framework of something so traditional—and what is more traditional in art than a single-sitter oil painting portrait—and to do it in 1977? To quote the artist, "How cool is that?"i

In Vendetta, Hendricks captures the essence of his artistic philosophy and technique, blending classical training with a contemporary flair that challenged and expanded the boundaries of portraiture. Hendricks, trained in both the United States and Europe, mastered and then redefined traditional oil painting techniques to celebrate the individuality and dignity of his subjects, often African Americans, with a bold, almost photographic realism. His use of vivid, unapologetic color and dramatic, life-sized presentation pulls viewers into a direct confrontation with the subject’s gaze, a hallmark of his style that reflects his deeper philosophies of presence and representation.

“I wasn’t a part of any “school.” The association I had with artists in Philadelphia didn’t inspire me in any direction other than my own. I spent my time looking to the Old Masters.” —Barkley Hendricks

Vendettafeatured in the artist’s first career retrospective, BirthoftheCool, which toured across the United States from 2008 to 2010. Originating at the Nasher Museum of Art in North Carolina and spanning a total of 5 major museums across the country, this major exhibition, organized by then-curator (now Nasher Museum Director) Trevor Schoonmaker, not only cemented Hendricks’ status as a pivotal figure in American art but also recontextualized works including Vendettawithin broader narratives of racial identity, aesthetics, and social commentary. The exhibition, and the continued study of his oeuvre, underscore Hendricks' lasting impact on challenging and expanding the conventions of portraiture, positioning him as a critical bridge between disparate artistic and cultural discourses.

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmDIqMtsV_o

Hendricks on Rembrandt

In 1966, while studying as an undergraduate at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Hendricks embarked on a transformative journey through Europe, visiting museums in the UK, Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands. In a 2009 interview with The Smithsonian, he reflected on this

trip and his admiration for the work of Old Masters like Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, and Johannes Vermeer. Highlighting the court portraits of Diego Velázquez and Anthony van Dyck, he cited the latter as an inspiration for his 1972 portrait entitled SirCharles,AliasWillieHarris. “There was a cardinal with his beautiful bed robe on,' he recalls, 'and subsequently, years later, I did a painting that’s now at the National Gallery [of Art, Washington, D.C.] where there were three views of a man with a long red coat.”ii

Hendricks was keenly aware of the scarce and often dehumanizing portrayal of Black figures in European art. Returning to the United States, he was determined to apply the Old Masters' techniques in a unique way, focusing on Black subjects. Asserting "It had to be done Barkley Hendricks style—no copies," he began creating innovative portraits from the late 1960s. These works not only redefined traditional portraiture but also enriched art history with a perspective that had been previously marginalized, laying the groundwork for a new generation of artists. In Vendetta, Hendricks masterfully adapts traditional techniques, showcasing his skill in paint and color through detailed textures, shadows, and depth. Set against a white backdrop, the focus shifts entirely to the sitter—to Vendetta, and who she is—emphasizing not only Hendricks' precise and nuanced handling of light, fabric, and hue, but also his ability to bring forth the peculiarities of a person that give them tangible presence.

“Any consideration of my work has to take into mind the work of Barkley Hendricks. He is completely foundational to my understanding of how you can make painting relevant today.” —Kehinde Wiley

Vendetta, the subject of the present portrait, was a friend of the artist and dancer based in New York. Not much is known about this enigmatic figure beyond what Hendricks captures in paint and provides in the work’s title. Yet, despite her mystery, Hendricks renders her in such a way that seems to transfer an almost intimate kind of knowing to the viewer. Much of what we know has been ascertained from Hendricks' many photographs—what he called his “mechanical sketchbook.”iii Hendricks employed photography in the way many painters use drawing: as a means of giving form to his ideas and documenting not only what he saw, but how he saw it. The paintings then are often a confluence of those images and his remembrances. In considering Vendetta, we can also rely on photographs of its subject, such as VendettainLotusPosition, 1977, and Untitled(NewLondon,CT), c. 1977. In doing so, it becomes apparent that Hendricks, while mostly remaining faithful to Vendetta’s likeness, took some artistic liberties with her fashion.

Untitled(NewLondon,CT)shows Vendetta with her arms bent and hands resting on her thighs. While in the painting, Hendrick’s cropping, the sitter’s pose, and her overall demeanor—an allwhite ensemble, micro-braided hair, and an air of self-assured poise—are closely derived from the artist’s photograph, the cross-body satchel she wears in life is absent.Most notably, her tank top, which is simple in the photograph except for a small cluster of rosettes at the neckline, has been altered in the painting to include the word "bitch" in lowercase gold lamé lettering across her

chest. Moreover, in the painted version, the letters "b" and "h" are enlarged and stylized to encircle and accentuate her breasts, and Hendricks has enhanced the contrast between skin and clothing for a more striking effect. The rosettes are also brightly colored, adding primary pops of yellow, red, and blue, creating a focal point that draws the eye directly to the word emblazoned on her chest. In Hendricks's work, clothing often represents power and self-awareness through selffashioning. In Vendetta, the woman occupies the central space of the canvas confidently, and her attire is simple yet bold. Hendricks's decision to keep her clothing neutral allows the viewer's attention to focus squarely on Vendetta, and the embellishment of the word “bitch” can be interpreted as a kind of challenge—to societal labels or as an assertion of her own control over such terms.

Transporting her to the flatness of a white-on-white painting, Hendricks foregrounds Vendetta as a physical being, showcasing not only her pose and the way she inhabits the pictorial space but also her particular features and expressiveness. The depths of contrast between her skin tone, hair texture, and clothing against the distraction-free expanse are striking. An early critic accused Hendricks of using the "same all-purpose brown" for his figures, to which the artist later responded, "Damn, even Stevie Wonder and Ray Charles can see a difference in the variety of skin handling I was involved with! The attempt on my part is always to address the beauty and variety of complexion colors that we call Black."iv

Nowhere is this more evident than in Hendricks’ white-on-white paintings. Perhaps the most famous set in his experiments with different shades of the same color, the white-on-white portraits were recently showcased at New York’s Frick Collection, where a room of the 2023-2024 exhibition BarkleyL.Hendricks:PortraitsattheFrickwas dedicated to these elusive limited palette works. Painting more than a hundred years earlier, the American artist James McNeill Whistler also experimented with form, limited palettes, and flesh color in his portraits. In the present work, one can easily see the influence of Whistler’s early 1860s series, collectively referred to as Symphonies inWhite, where the paintings' true subject was his handling of the thick white paint, its textures,

James McNeill Whistler, SymphonyinWhite,No.1:TheWhiteGirl,1861-1863. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Image: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Harris Whittemore Collection, 1943.6.2and subtle tonal contrasts. In Whistler’s time, paintings like the National Gallery of Art’s Symphony inWhite,No.1:TheWhiteGirl,1861-1863/1872 constituted a radical break with traditions of portraiture; in the 1970s, Hendricks took that subversion a step further. In his own white-on-white paintings, Hendricks demonstrates his masterful handling of color and the painted edge, not only in his machinations of one color against itself but also in that color against its opposite. In Vendetta, white is not only a compositional device, but also a signifier and a powerful element of social commentary. By using white in portraits of Black figures, Hendricks subtly addresses themes of visibility and identity. This approach invites viewers to consider how race is portrayed and perceived in art, encouraging a deeper reflection on both the medium and the message.

Hendricks's rich treatment of color shines through in Vendetta,evident in his choice of background, displaying an intimate relationship with the materiality of clothing with great attention to how they fold or reflect light, and in minute details like how he paints the weave and fade of fabrics. Hendricks' relationship to the minutiae of lived reality transcends visual perception, engaging viewers on a multisensory level that mirrors the tactile experiences of everyday life. By emphasizing textures like the cotton weave of Vendetta’s tank top, Hendricks evokes not just sight but the sensation of touch, inviting the viewer to experience the material as if it were tangible. This depth of sensory engagement allows viewers to connect more profoundly with his work, as Hendricks masterfully blurs the line between the painted image and real-world experience.

“No

one paints jeans like me, with the consciousness of the fact that jeans are a material that is worn rather than painted… The art of painting is not only about putting paint down. I like to use the texture of the canvas as a vehicle to get the illusion that I'm interested in.”

—BarkleyHendricks

In an interview with Thelma Golden, Hendricks called his white-on-white portraits "double whammies," referring to the combination of the figures’ strong personalities coupled with the bold formal aspect of his "limited palette series." In portraits like Vendettaand TuffTony,1978, Hendricks subjects confront the viewer with a direct gaze. The eye contact serves to draw the viewer in but also stimulates self-consciousness in viewing, speaking to the idea of viewing itself, of seeing and being seen. Hendricks captures performative attitudes in his subjects, as if they were self-conscious about the version of themselves they chose to convey. This self-consciousness comes across as much a part of Hendricks’ palette as his paint, working with tonal shades of attitude. TuffTonyframes a young man, centered in the composition, hands hung loose at his sides, his face a mask of calm and defiance, undergirded by the slightest hint of sadness. Similarly, Vendettasizes up her viewer. Her pose is confident, sitting with her legs wide and hands assertively placed below her hips. She extends outside the picture plane, seeming to spill over into the gallery space. This, combined with Hendricks’ construction of her eyeline such that she appears to be looking down at us from somewhere slightly above, contributes to the sense of monumentality that seems to far exceed the painting’s scale.

“I wanted [the image] to have some potency besides the scale element...if you get too small, you start to dwarf it. If you get too large, you get into a billboard sort of situation. But if you keep it pretty close to human scale, you have a better chance of having the human that’s looking at it interact with that... And adding the ingredient that would hopefully catch your eye, that I hope will make it linger.” —Barkley Hendricks

Hendricks’ white-on-white paintings masterfully elevate his sitters to iconic status through a simple yet potent visual strategy that mirrors the sacred aura of Byzantine and medieval religious icons. In Vendetta, Hendricks employs a monochromatic, all-white background that strips away contextual distractions, focusing the viewer’s attention solely on the figure. This deliberate sparseness and the halo-like effect created by the uniform color field not only draw parallels to the spiritual reverence of religious art but also frames the Black figure as both timeless and venerable. The lack of background emphasizes the intrinsic worth and dignity of the individual, positioning the subject almost as an archetype. In works like Vendettaand LawdyMama, 1969, at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Hendricks suggests that these women—his friend and cousin “who had a beautiful ’fro”—are akin to modern-day Madonnas.v Thus, his technique not only celebrates the individuality of his subjects but also asserts their universal significance in the broader iconography of art, readdressing historical omission and making “icons for a new era.”vi

“Using rich, bold colors, [Hendricks] documents the beauty and power of young African-Americans underrepresented in the mainstream, fromLawdy Mama, a 1969 painting of a woman on a gold background with an afro (it’s known as the Madonna of the Studio Museum in Harlem), toVendetta, a 1977 portrait of a fearless-looking woman with the word “Bitch” on her tank top. Cool, indeed.” —The Village Voice

Following his passing in 2017, Hendricks' legacy has experienced a notable resurgence, highlighted by significant exhibitions such as BarkleyL.Hendricks:PortraitsattheFrick, which ran from September 2023 to January 2024 at the Frick Collection in New York. The groundbreaking exhibition presented a selection of Hendricks’ figurative works in the context of the Frick’s holdings, emphasizing the dialogue between Hendricks’ vivid depictions of Black figures and the traditions of European art that he both drew from and challenged, and marking the first solo show for an artist of color in the collection’s 88-year history. As described by Trevor Schoonmaker, “[Hendricks] has defied easy categorization, and his unique individualism has landed him outside of the mainstream, but his bold and empowering portrayal of those who have been overlooked and underappreciated has positioned him squarely in the hearts of many…By representing the black body in new and challenging ways, Hendricks’ pioneering work has unwittingly helped pave the way for future generations of artists of color to work with issues of identity through representation of the black figure. Today his body of work is as vital and vibrant as ever, and it should prove him to be a lasting figure in the history of American art.”vii

“I like to feel that once you leave a show you remember my work either through what I’ve done with the paint or something that may have intrigued you or something that got your attention… if you’re gonna do it, you might as well be memorable.”

—Barkley Hendricks

i Barkley Hendricks, “Palette Scrapings,” pp. 105-107, in Trevor Schoonmaker, BirthoftheCool, Exh. Cat., Durham, North Carolina, 2008.

ii Anna Arabindan-Kesson, InterviewwithBarkleyL.Hendricks, 25 August 2016.

iii Arthur Lubow,What You Didn’t Know About Barkley L. Hendricks, TheNewYorkTimes, published May 14, 2021, updated May 15, 2021, online.

iv Zoé Whitley, ed., BarkleyL.Hendricks:Solid!, Milan, 2023, p. 76.

v Barkley Hendricks, quoted in Leila Pedro, “Barkley L. Hendricks with Laila Pedro,” TheBrooklyn Rail,April 2016, online.

vi C. Wiley, “Fashion and Politics in Barkley L. Hendricks’s Pictures,” TheNewYorker, May 28, 2023.

vii Trevor Schoonmaker, BirthoftheCool,Exh. Cat., Durham, North Carolina, 2008, p. 36.

PrProovvenanceenance

ACA Galleries, New York

Acquired from the above by the present owner in 2007

ExhibitedExhibited

Durham, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; Houston, Contemporary Arts Museum, BarkleyL.Hendricks:BirthoftheCool,February 7, 2008–April 18, 2010, no. 35, pp. 38-39, 41, 85, 131 (detail illustrated, p. 38; Vendetta with the present work in the artist’s studio illustrated, p. 39; illustrated, p. 85)

LiteraturLiteraturee

TheBarkleyL.HendricksExperience, exh. cat., Lyman Allyn Museum of Art, New London, Connecticut, 2001, pp. 6, 8 (illustrated, p. 6)

Richard J. Powell, CuttingaFigure:FashioningBlackPortraiture, Chicago, 2008, no. 78, pp. 156, 166, 169, 219, 270, 275 (illustrated, p. 156)

Amy White, “Barkley L. Hendricks’ Nasher show: Art history, honored and challenged,” INDY Week, March 5, 2008, online

Araceli Cruz, “Cool Cat,” TheVillageVoice, November 5, 2008, online

Kelly Klaasmeyer, “The Art of Cool,” HoustonPress, March 10, 2010, online

“At Home in New London with Artist Barkley Hendricks,” HartfordCourant, April 30, 2010, online

Trevor Schoonmaker, “Barkley L. Hendricks: Reverberations,” FreshPaint, 2012, p. 98

Robin Cembalest, “Reinventing the African American Portrait,” ARTnews, August 1, 2013, online (dated 1978)

Jared Bowen, “With his camera, artist Barkley L. Hendricks brought his world view into focus,” GBH.BostonPublicRadio,March 16, 2022, online

Jared Bowen, “New exhibit chronicles work of late painter Barkley Hendricks and his use of the camera,” PBSNewsHour,May 18, 2022, online

Zoé Whitley, ed., BarkleyL.Hendricks:Solid!, Milan, 2023, p. 79 (illustrated; dated 1978)

BarkleyL.Hendricks:PortraitsattheFrick, exh. cat., The Frick Collection, New York, 2023, fig. 83, pp. 108-109, 158 (installation view in the artist’s studio illustrated, p. 109)

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

BASQUIAT’S WORLD: WORKS FORMERLY FROM THE COLLECTION OF FRANCESCO PELLIZZI

Untitled (ELMAR) signed "Jean-Michel Basquiat" on the reverse acrylic, oilstick, spray paint and Xerox collage on canvas

68 x 93 1/8 in. (172.7 x 236.5 cm) Executed in 1982.

EstimateEstimate

$40,000,000 — 60,000,000

Video: https://www.youtube.com/embed/SgNWp6AuREQ

“Black and like a Jack Kerouac of painting, he was a true American artist-hero. Jean-Michel Basquiat is also, in a more general sense, one of the truly original Western artists of the 1980s. His paintings show, in retrospect, the necessity and the inevitability of all significant contributions to our poetic understanding of the world.” —Francesco Pellizzi i

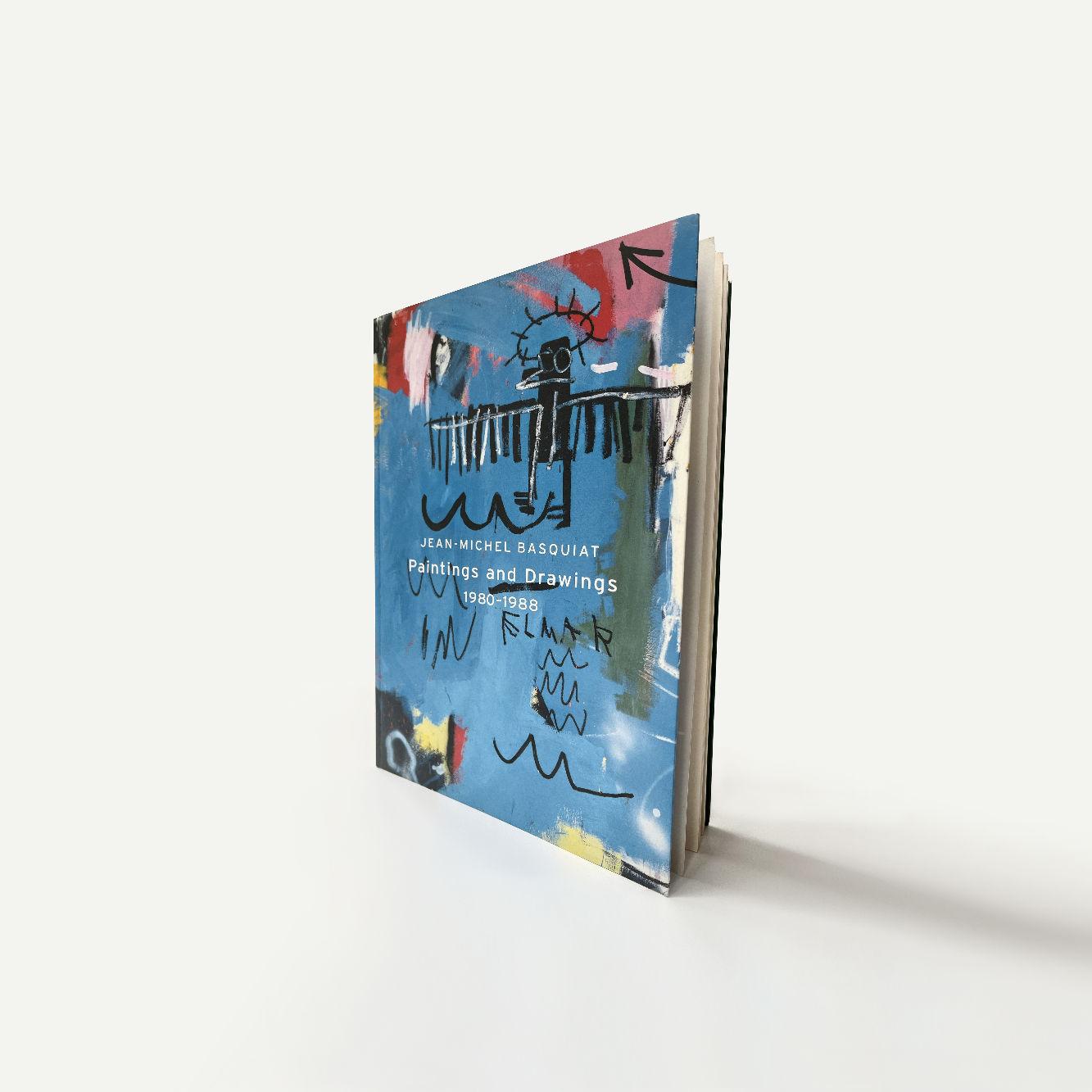

Jean-Michel Basquiat's monumental painting, Untitled(ELMAR), created in 1982, is a paradigmatic representation of the artist's genius, making its auction debut after remaining in private hands for four decades. At nearly eight feet wide, this tour-de-force is a cornerstone of Basquiat's golden year, during which he transitioned from street art to gallery success. Emblematic of Basquiat’s best works, Untitled(ELMAR)is rich with historic and mythical iconography, intertwined with the artist’s invented symbols and graphic marks that accentuate the physical, gestural nature of his creative process. Boasting an equally impressive provenance and exhibition history, the present work was exhibited at Gagosian Los Angeles in 1998, as part of a memorial exhibition commemorating the 10-year anniversary of the artist’s death. Untitled(ELMAR)was notably featured on the cover of the accompanying catalogue. More recently, the work was prominently exhibited in the artist’s historical 2018 retrospective at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. This sale marks the first time that this important work is being offered publicly.

Formerly part of the original collection of Francesco Pellizzi, the present work was acquired by the renowned historian and collector from Annina Nosei in 1984, just two years after its creation, and remained in his collection for decades. An inspired collector and friend of the artist, Mr. Pellizzi acquired timeless works that underscore Basquiat's enduring significance and artistic vision, as they continue to inspire and provoke thought forty years later. Reflecting on his 40-year friendship with Francesco and the acuity of his perceptiveness, American painter David Salle remarked, “Francesco [was] always full of vitality and interests and witty observations and warmth and engagement, the same sense of deep inquiry, and also imagination.[…] And there was something else too: a quality I can only call wisdom, a macro way of seeing things at the same time as the tiniest detail… he had the close-up view and the overview, he saw the particulate and the flow. He could combine 'like with like', and also 'like with not-quite-like', which is more rare, and all the more so when done seemingly without effort.”ii

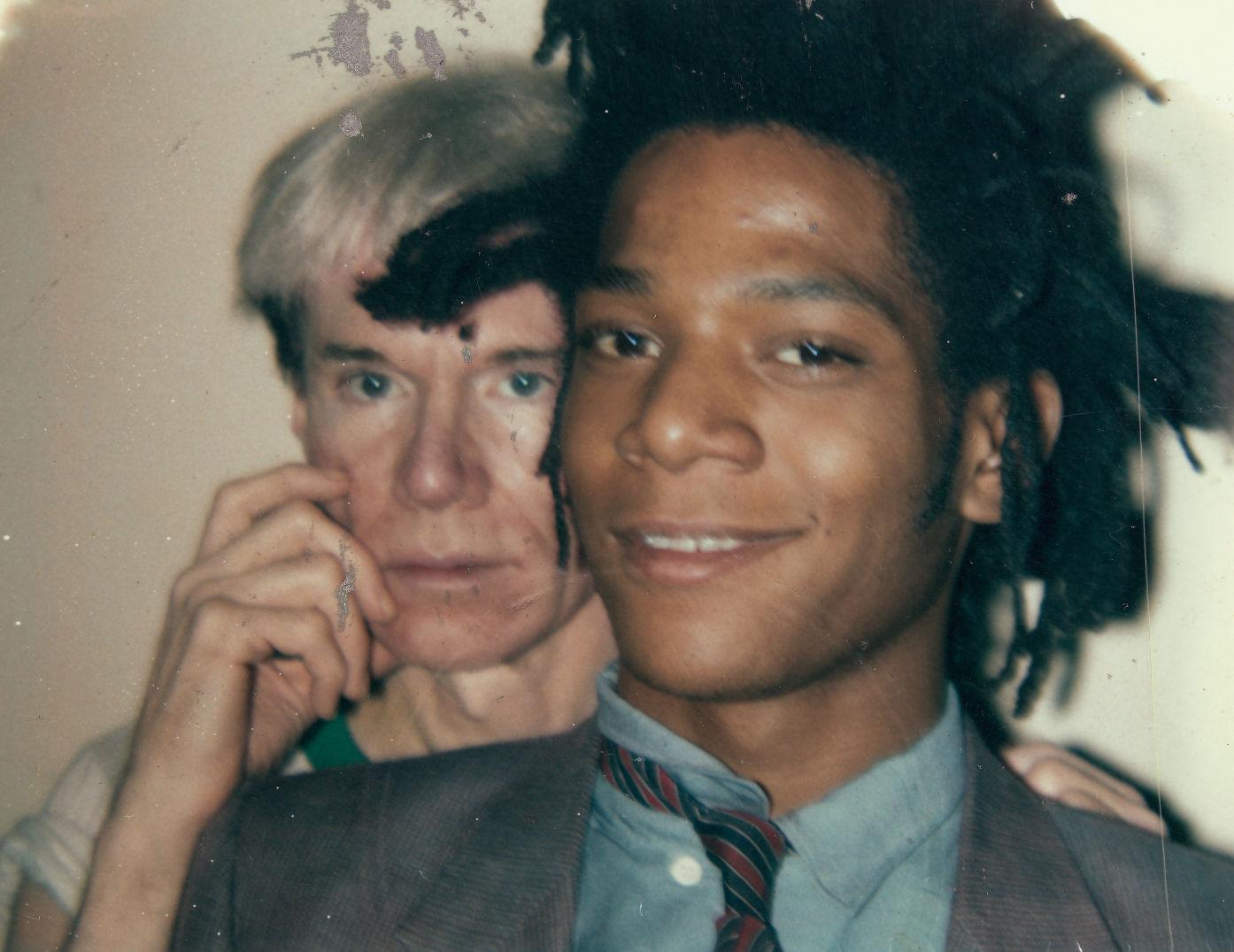

Francesco Clemente, Andy Warhol, and Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Pellizzi residence in New York, NY, 1984. Photo by Francesco Pellizzi.Image: © Francesco Pellizzi

The present work illustrated on the cover of Jean-MichelBasquiat:Paintings&Drawings 1980–1988,Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, 1998, exhibition catalogue.

Untitled(ELMAR)was first shown in an exhibition dedicated to the Collection of Francesco Pellizzi, which took place at the Hofstra Museum in New York in 1989. In an essay of same year, Pellizzi reminisced on his friendship with Basquiat and the artist’s insatiable hunger for absorbing information and history. Reflecting on their discussions about art and language, Pellizzi detailed the myriad ways in which Basquiat’s voracious appetite for knowledge, coupled with his unique rebelliousness and sense of freedom, manifested in the artist’s painting practice, ultimately contributing to his mastery of the medium. He contends that in Basquiat's work one finds traces of almost all the great painters of the previous two generations, though he cannot be termed a follower of any of them.

“For Basquiat, it all converges in 1982. Those of us who were there at the time and saw those paintings just couldn’t believe it…Everybody around him knew that these were extraordinary.” iii —Jeffrey Deitch

In 1982, often hailed as Basquiat's “Golden Year,” the 22-year-old artist produced approximately 200 significant works on canvas. Untitled(ELMAR), stands out for its raw, colorful, and direct style, epitomizing the lauded traits of this prolific period in Basquiat’s career. Characteristic of the work produced at this moment, the present painting constitutes a more confident prelude to the meticulous curation and self-consciousness of Basquiat’s later compositions, instead exuding an air of daring openness. Jeffrey Deitch, a prominent art dealer and friend of the artist, describes how, in 1982, “[Basquiat’s] peers had already anointed him as the best artist in the community, and he had the accolades of NewYork/NewWave.” According to Deitch, the newfound attention inspired “an increased confidence in the painting: in the strength, in the line.”iv This transformation can be partially attributed to its inception during a period of convergence, characterized by elements such as a steady supply of large-scale canvases from his new dealer, Annina Nosei, Basquiat's inaugural solo exhibition in the United States, staged at Nosei’s New York gallery, followed by a series of one-man shows worldwide, and acknowledgment from the mainstream arts establishment. These factors denoted a moment of artistic freedom and acclaim for Basquiat, preceding the onset of market pressures that would persist throughout his lifetime.

Andy Warhol, Self-PortraitwithBasquiat,October4, 1982. Private Collection.Artwork: © 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

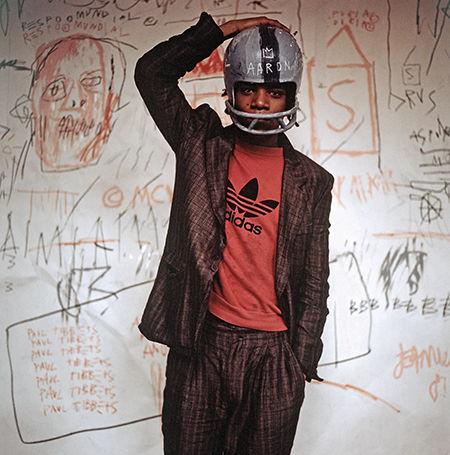

Significantly, Untitled(ELMAR)was executed in the same year Basquiat was first introduced to Andy Warhol, a paramount encounter that would later lead to collaboration between the two artists. 1982 also marked Basquiat's transition from “SAMO©”—the pseudonym under which he operated as a street poet and tagger, to an influential figure in the art world. On Monday, October 4th, 1982, an ordinary entry in Warhol’s diary concealed the remarkable convergence of two avantgarde art titans: “Down to meet Bruno Bischofberger (cab $7.50). He brought Jean-Michel Basquiat with him. He’s the kid who used the name “Samo” when he used to sit on the sidewalk in Greenwich Village and paint T-shirts… then Bruno discovered him and now he’s on Easy Street. And so I had lunch for them, and then I took a Polaroid, and he went home, and within two hours a painting was back, still wet, of him and me together.”v

Indeed, we see the influence of Warhol in Basquiat’s canvases from this year, the present work included.In contrast to the pictorial abundance of many of his earlier compositions, in Untitled (ELMAR), Basquiat allows ample breathing room in which the implied connections between his signs and symbols can be lucidly drawn. This sense of spaciousness engenders an ambiguity within the painting that lends it a distinctly Warholian effect in that, despite his use of bold colors, frenetic

brushwork, and dense layers of imagery, there is often an openness and expansiveness to Basquiat’s presentation. Untitled(ELMAR)incorporates space in unconventional ways, with areas of intense activity punctuated by less vigorously worked areas and even glimpses of raw canvas that can appear spare in comparison but are by no means passive. Basquiat orchestrates a dynamic tension that allows viewers to navigate through the artwork and interpret its various elements at their own pace. In doing so, he provides a space for pausing and, in turn, for emphasis.

In Untitled(ELMAR), Basquiat’s visual cadence akin to instinctive and visceral melodies, combined with his incorporation of handwritten text elements, is also evocative of Cy Twombly’s poetic incorporation of handwritten script and calligraphic marks. In its shared engagement with classical antiquity, Greek and Roman mythology, and the malleability of language, the present work exhibits intriguing parallels with a series Twombly produced in the 1960s featuring titles indicative of famous mythological couples. Here, Basquiat infuses urban culture with references to iconic figures and symbols of ancient lore, such as Icarus and possibly Apollo, the ancient Greek god of archery, weaving a cautionary tale that illustrates a similar fascination with the intersection of ancient myth and contemporary expression. Basquiat further blurs the boundaries between text and image, creating a richly layered work that evokes emotion, memory, and the timeless resonance of classical literature and history.

Born to Haitian and Puerto Rican parents, Basquiat spoke fluent Spanish and often incorporated

Jean-Michel Basquiat, BoyandDoginaJohnnypump, 1982. Private Collection. Formerly in the collection of The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut.Image: Archivart / Alamy Stock Photo, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New Yorkthe language into the text elements of his artworks as an extension of his career-long interest in the duplicity and obfuscation of meaning. In the present work, he writes “ELMAR” above a crest of waves. As one word, the meaning (perhaps a name) is obtuse but, as two, “el mar,” it takes on new resonance. In Spanish, “el mar” means “the sea,” stemming from the Latin, “mare.” Aside from reinforcing his interest in antiquity, the root of the word becomes important in Spanish as in Latin “mare” was neither masculine nor feminine but neuter. As Spanish evolved, the word was preserved in two forms: masculine and feminine, with each form being used differently. The feminine form describes the state of the sea, while “el mar” is used to give each sea a name. This kind of wordplay speaks as well to Basquiat’s thematic interest in duality and multiple states of being, which he returned to throughout his career in works such as Baptismal, 1982, in the Collection of Valentino Garavani, London, and one of his final paintings, entitled RidingwithDeath, 1988, private collection.

[Left] Cy Twombly, LedaandtheSwan, Rome, 1962. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.Image: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY, Artwork: © Cy Twombly Foundation [Right] Attributed to the manner of the Bowdoin Painter, TerracottaNolanneck-amphora (jar),ca. 480–470 BCE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1941, 41.162.114

“If Cy Twombly and Jean Dubuffet had a baby and gave it up for adoption it would be Jean-Michel. The elegance of Twombly is there [and is] from the same source (graffiti) and so is the brut of the young Dubuffet.” —René Ricard vi

From a technical standpoint, Untitled(ELMAR)is an incredible example of Basquiat’s early style

that incorporated visible pentimenti. Traditionally, a pentimento is a moment within a painting in which a previous compositional choice or image can be seen through the top paint layer.Basquiat utilized this concept to his advantage, frequently painting with a mixture of thick and thin layers that intentionally revealed the underlying strata. This is particularly evident in the anatomy of the warrior figure, where the body is composed of overlapping swathes of red and white paint, black oilstick, and gold spray paint. The expansive blue sea also provides hints of what lies beneath its surface, with indiscernible gestures peeking through. Moreover, Basquiat asserts his process and presence by incorporating visible footprints that metaphorically ground his artistic expression. He often worked his canvases horizontally on the floor, reminiscent of New York's earlier Abstract Expressionist painters like Jackson Pollock and Helen Frankenthaler.

Basquiat also credited Franz Kline as one of his most significant influences. Kline’s technique, using wide house-painter brushes loaded with paint on large canvases, inspired a freedom of mark-making evident in Untitled(ELMAR).Here, bold black lines define the warrior's frame, while broad, multidirectional strokes of color set the scene. Basquiat's use of acrylic, oilstick, and spray paint captures a flurry of gestures, showcasing his improvisational, fast-paced, and multilayered approach. Annina Nosei recalls her first encounter with the work at her SoHo gallery, sensing it as a true “painting about painting,” and the liberation that such action invites.vii

Franz Kline, Mahoning, 1956. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Image: © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY, Artwork: © 2024 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

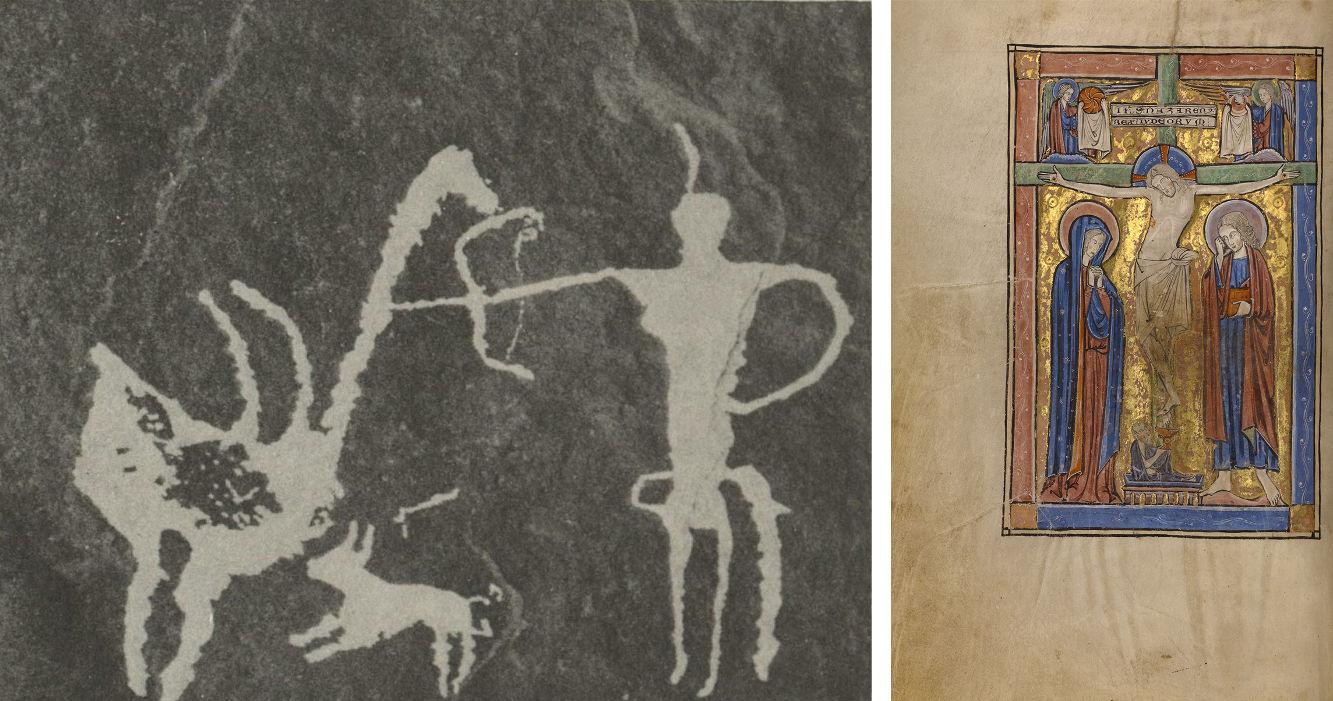

Basquiat took inspiration from a dizzying array of source material and his studio environment further reflected his immersion in the creative process, with open books and unfinished works strewn about, accompanied by a soundtrack of Jazz, Bebop, and television. Often combining a variety of influences, like Christianity, African rock art and hieroglyphics, and his own Puerto Rican and Haitian heritages into one piece, Basquiat’s canon of archetypal figures carry out their own ritualistic functions. In Untitled(ELMAR),Basquiat undertakes a pseudo-survey of human and art history, presenting a quasi-anthropological exploration that celebrates life and visual culture with rhapsodic fervor.

In Untitled(ELMAR),Basquiat conjures a large-scale warrior figure, using vigorous brushstrokes in the style of Jean Dubuffet's art Brut and subtly exposing its skeletal structure in a nod to his own enduring fascination with anatomy. Constructed with a mix of red flesh and oilstick bone, reinforced by metallic gold spray paint, Basquiat's creation resembles a modern-day Frankensteinian fighter, assembled with unmistakable strength. The figure is enveloped in a haloed aura (coming from the Latin “aurea” for “golden”), a vivid burst of yellow forming something loosely akin to a mandorla—an almond-shaped motif often associated with Christian iconography depicting scenes from the life of Christ—or an aureole. Adding to the sense of sanctity, Basquiat’s use of gold embellishments and a haloed figure set against a bright background mirrors the shimmering gold accents often found in similar scenes, as illustrated in Medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Extending from the warrior's raised arms are a flurry of arrows and a bow, complemented by a crown of thorns atop his head, establishing a delicate equilibrium between European monarchical and African tribal power symbols. Basquiat's inspiration here likely draws from Burchard Brentjes' 1969 text, AfricanRockArt, a volume he was known to keep in his studio. The rich array of photographs and diagrams therein appealed to Basquiat for their cultural significance, aligning with his preference for a raw and unschooled style of drawing, as well as his affinity for graffiti, with cave art arguably serving as its earliest manifestation.

“I get my facts from books, stuff on atomizers, the blues, ethyl alcohol, geese in Egyptian glyphs… I don’t take credit for my facts. The facts exist without me.”

—Jean-Michel Basquiat

vii

In a similar fashion to other large-scale single figure paintings from the period, such as Boyand

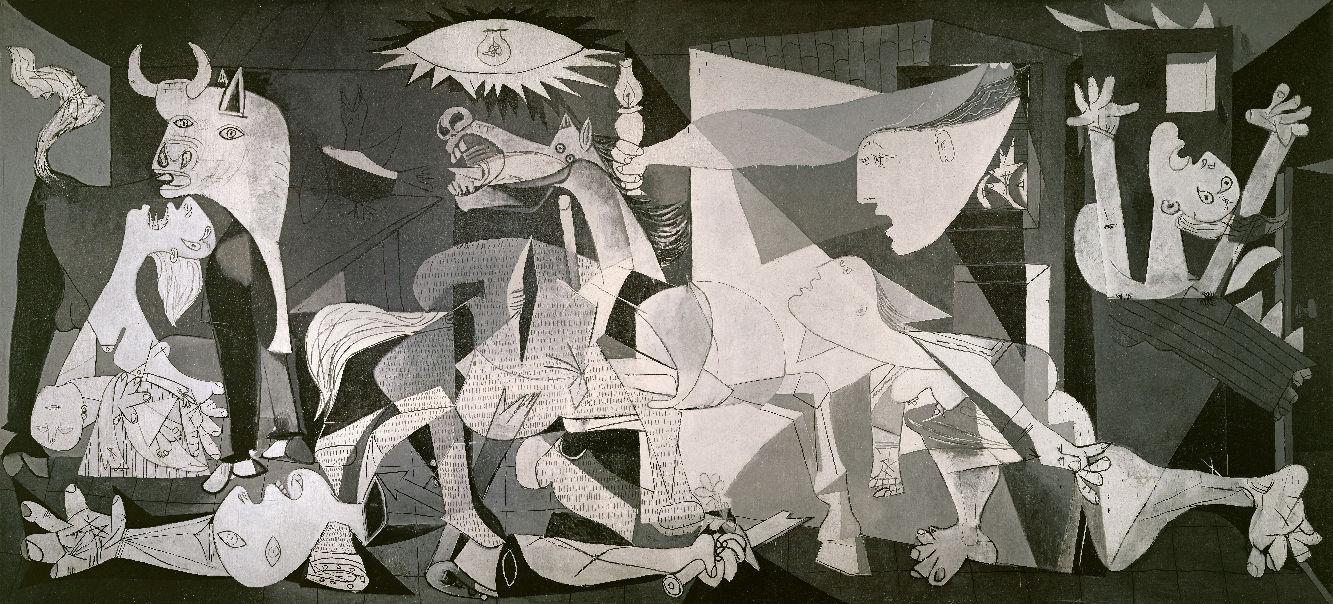

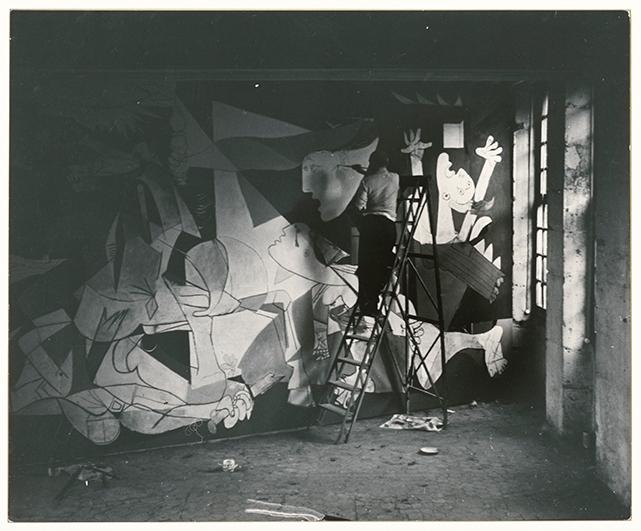

[Left]Rock art at Wadi Abu Wasil, Eastern Desert of Egypt, prior to 3000 BC. [Right]Unknown artist/ maker, TheCrucifixion, begun after 1234–completed before 1262, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.DoginaJohnnypump, 1982, formerly in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, in Untitled (ELMAR)Basquiat conveys his warrior's strength anatomically. Curator and art historian Richard Marshall suggests that Basquiat may have been influenced to incorporate such boldness and aggression into his canvases upon encountering Picasso's "Avignon" paintings, displayed at the Pace Gallery in New York in the winter of 1981. In the works on view, Picasso returned to drawing anatomically graphic and distorted figures in bold colors, an expressive style Basquiat undoubtedly felt an affinity for, given his lifelong admiration of the Spanish artist. Reflecting on his early exposure to Picasso’s work, Basquiat once stated that, “seeing Guernicawas my favorite thing as a kid.”ix Indeed, a parallel can easily be drawn between the figure at the far right of Guernica, crying out to the heavens with arms raised, illuminated by the jagged light of a burning house behind them—along with the faded dove, a symbol of peace obscured amidst the unfolding violence—and the heroic figure in the present work, confronting their winged target.

In the present work, a “fallen angel” figure at left, birdlike and adorned with the recurring crownof-thorns motif—which doubles as a halo—hovers above a luminous blue sea of scribbled waves and the text “ELMAR”, suggesting a modern-day Icarus on the verge of descent. Through this lens, Basquiat’s archetypal warrior at right takes on an additional layer of meaning, signaling the angel’s imminent downfall. Basquiat often used variations of the fallen angel motif in his art to delve into themes of identity, power dynamics, and societal alienation. Throughout art history, artists have employed this image, notably seen in Alexandre Cabanel's eponymous painting, TheFallenAngel, 1847, at the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, to depict a majestic yet sorrowful figure symbolizing rebellion, spiritual downfall, and the eternal struggle between divine and mortal realms. In Untitled (ELMAR),Basquiat continues this tradition, portraying the figure caught between heaven and earth, poised for a fall. This concept reflects his own experiences as a Black artist navigating a

white-dominated art world, where he felt a perpetual sense of alienation and a fear of losing relevance.

New York

The winged figure in Untitled(ELMAR)also resonates with Basquiat’s recurring bird motif, notably observed in his monumental painting created the same year, Untitled(LAPainting),1982. Basquiat's birds embody bravery and freedom, doubling as messengers from celestial realms. They evoke symbolism akin to ancient Roman culture where open-winged birds represented power and divine communication, their movements believed to reflect the will of the gods. Additionally, the bird figure may be a veiled reference to one of Basquiat’s heroes, the prominent American jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker. Parker, nicknamed “Bird”, was a leading figure in the development of bebop, whose improvised style greatly influenced Basquiat.x The artist was known to listen to Parker's music in the studio.

One of the key motifs in the present painting is a depiction of a skull or human head, which originates from an important oilstick on paper drawing entitled Untitled(IndianHead). Now in the collection of Museo Jumex in Mexico City, this image later became a recurring feature in several of Basquiat’s major works. In his poem titled J.M.B.’sDehistories, Trinidadian-Bahamian poet Christian Campbell provides insightful interpretations of recurring visual motifs, such as the skulls and human heads that inhabit Basquiat’s oeuvre. He asserts that, “Basquiat’s heads are cartooned, spooked, fried, shocked, damaged. Strange as it may seem, I hear these heads laughing.” He describes them as if cackling in a mad chorus but concludes that, “They see us to the bone, just as we see them. They are witnesses. They are messengers. They have something true to tell us.”xi

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937. Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid.Image: Bridgeman Images, Artwork: © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled(L.A.Painting),1982. Private Collection.Artwork: © Estate of JeanMichel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar,

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled(IndianHead),1981, Museo Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico.Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

In Untitled(ELMAR),Basquiat’s replacement of the painted head with an intricate, additive rendering marks a stark complexity compared to the gestural lines created through painting, spraying, and drawing. Alongside his use of fragmented written language, inspired by William Burroughs' cut-up technique, Basquiat employed collage elements to counteract both formally and materially with his intense painterly work. This integration of collage evokes parallels with the Constructivist and Cubist movements, particularly in the way Picasso and others utilized fragmented imagery to challenge traditional notions of representation. Similarly, Basquiat's approach resonates with Robert Rauschenberg's combines, where disparate elements are amalgamated to blur the lines between painting and sculpture. By incorporating collage into his

oeuvre, Basquiat not only expands upon the rich legacy of assemblage but also engages in a broader artistic dialogue that spans across movements and generations.

Moreover, Basquiat's strategic use of collage in Untitled(ELMAR)reflects the fragmentation within diasporic narratives due to migration, highlighting the complexities of personal histories amidst received ones. In the present work, where the only collaged element is the head of the central figure, the act of severing the head from the body takes on poignant symbolism. This detachment may symbolize the fragmentation and dislocation experienced by individuals within diasporic communities, where identity and history are often separated and reassembled in complex ways. It also resonates with a Basquiat-ism that originates in a painting from the same year, CharlestheFirst, 1982: "MOST YOUNG KINGS GET THEIR HEADS CUT OFF," which speaks to the systemic erasure faced by marginalized groups, particularly young black men, in society. By isolating the head in Untitled(ELMAR), Basquiat highlights the vulnerability and precariousness of identity, as well as the pervasive violence and oppression faced by those who dare to assert their agency and cultural significance. Thus, the act of cutting off the head serves as a potent metaphor for the struggles and resilience of marginalized communities in the face of historical and contemporary injustices.

“It is only in writing these notes that I realize how difficult it is to describe Basquiat’s paintings as representational objects. Just when we think we have seized something essential about them, the essence evaporates. The paintings seem to slip away right and left, despite their remarkable compositional strength—a centripetal tension between all the elements that seems to owe more to a conceptual and poetic toughness than to Basquiat’s obvious gift for formal harmony.”—Francesco Pellizzi

In Untitled(ELMAR),a torrent of imagery—ranging from symbols and diagrams to words—dances across the canvas against a backdrop of boundless blue and electric yellow. This chaotic yet controlled display manifests Basquiat's recurring themes of identity, existentialism, and societal disillusionment. It synthesizes life, death, history, and mythology into a vibrant tapestry, where Basquiat's insatiable hunger for knowledge and boundless creativity blur the lines between street art and the established norms of the traditional art world.

While rooted in New York City, Basquiat transcended his environment, grappling with a history and identity extending beyond its confines. This duality extends beyond personal identity, reflecting complex social, political, and cultural dynamics, particularly the struggle for equilibrium between black and white worlds. Basquiat explores duality through various lenses, juxtaposing people and objects, words and images, and reimagining concepts of black and white, light and dark, challenging conventional notions of good and evil.

Central to Basquiat’s practice was representing seemingly conflicting aspects of human experience within a single work. Whether contrasting opposing colors, depicting scales of justice, or exploring themes like “God and Law,” the artist was consistently concerned with duality and reconciling

opposing forces. In Untitled(ELMAR),Basquiat portrays the duality of the hunter and the hunted, alongside the notion of ascent followed by inevitable decline, echoing his own rise in the art world. Basquiat’s fascination with stardom and "burnout" becomes apparent in references to artists like Charlie Parker. Caught between a desire for fame and a fear of being consumed or exploited, the present work captures Basquiat’s apprehension of flying too close to the sun, symbolized by the pregnant moment before the hero’s downfall. Here, the winged figure soars like Icarus toward the heavens, defying limitations in pursuit of freedom. "Only one thing worries me," Basquiat once told his father, "Longevity."xii

i Francesco Pellizzi, “Black and White All Over: Poetry and Desolation Painting,” pp. 9-17, Tracy Williams, ed., Jean-MichelBasquiat, New York, 1989, p. 15.

ii David Salle, quoted in private correspondence, n.d.

iii Jeffrey Deitch, quoted in Alexxa Gotthardt, “What Makes 1982 Basquiat’s Most Valuable Year,” Artsy, April 1, 2018, online

iv Jeffrey Deitch, quoted in Ibid.

v Andy Warhol, quoted by Pat Hackett, ed., TheAndyWarholDiaries, New York, 1989, p. 462.

vi René Ricard, “The Radiant Child,” Artforum, vol. XX, no. 4, December 1981, p. 43.

vii Annina Nosei, quoted in interview conducted by Scott Nussbaum at Phillips, New York, April, 2024.

viii Jean-Michel Basquiat cited in: Exh. Cat., London, Barbican, Basquiat:BoomforReal, 2017, p. 189

ix Jean-Michel Basquiat, quoted in “Interview by Becky Johnston and Tamra Davis,” TheJeanMichelBasquiatReader:Writings,Interviews,andCriticalResponses, Berkeley, 2021, p. 52.

x Olivier Michelon, “Time is Now,” Jean-MichelBasquiat, exh. cat., Paris, 2019, pp. 202 -208.

xi Christian Campbell, “J.M.B.'s dehistories,” pp. 209-210, Dieter Buchhart, Jean-MichelBasquiat: Now’stheTime, Ontario, Canada, 2015.

xii Jean-Michel Basquiat, quoted in Lexi Manatakis, “Jean-Michel Basquiat in his own words,” Dazed, November 21 2017, online

PrProovvenanceenance

Annina Nosei Gallery, New York

Elaine Dannheisser (acquired from the above)

Francesco Pellizzi, New York (acquired from the above via Annina Nosei Gallery in 1984)

Acquired from the above by the present owner

ExhibitedExhibited

Hempstead, Hofstra Museum, Hofstra University; Bethlehem, Lehigh University Art Galleries, 1979–1989American,Italian,MexicanArtfromtheCollectionofFrancescoPellizzi,April 16–November 2, 1989, no. 4, pp. 6, 19, 58 (illustrated, p. 19)

Los Angeles, Gagosian Gallery, Jean-MichelBasquiat:PaintingsandDrawings1980-1988, February 12–March 14, 1998, no. 13, n.p. (illustrated; detail illustrated on the front and back cover)

Houston, The Menil Collection, 17Contemporaries:ArtistsfromAmerica,Italy,andMexico-the Eighties, June 11–August 15, 1999, n.p.

New York, Gagosian Gallery, Jean-MichelBasquiat,February 7–April 6, 2013, pp. 88-89, 203 (illustrated)

Paris, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Jean-MichelBasquiat, October 3, 2018–January 4, 2019, no. 66, pp. 181-183 (illustrated, pp. 182-183)

LiteraturLiteraturee

Ted Castle, “Jean-Michel Basquiat,” ArtistesRevuebimestrielled’artcontemporain, no. 14, January-February 1983, p. 29 (illustrated)

Richard D. Marshall and Jean-Louis Prat, Jean-MichelBasquiat,Paris, 1996, no. 3, pp. 90-91 (illustrated, p. 90)

Tony Shafrazi, Jeffrey Deitch and Richard D. Marshall, eds., Jean-MichelBasquiat,New York, 1999, p. 129 (illustrated)

Richard D. Marshall and Jean-Louis Prat, Jean-MichelBasquiat, vol. II, Paris, 2000, no. 3, pp. 138-139 (illustrated, p. 138)

Léa Di Michele, “La Fondation Louis Vuitton Rend Hommage à Jean-Michel Basquiat,” Femmes Magazine, February 8, 2018, online (illustrated)

Hans Werner Holzwarth, Benedikt Taschen and Eleanor Nairne, eds., Jean-MichelBasquiatandthe ArtofStorytelling, Cologne, 2018, pp. 138-139, 494 (illustrated, pp. 138-139)

Nazanin Lankarani, “Egon Schiele & Jean-Michel Basquiat,” GagosianQuarterly, Spring 2019, p. 76

Dieter Buchhart, ed., Jean-MichelBasquiat:Xerox, Berlin, 2019, fig. 9, pp. 18, 21 (illustrated, p. 21)

New York Auction / 14 May 2024 / 5pm EDT

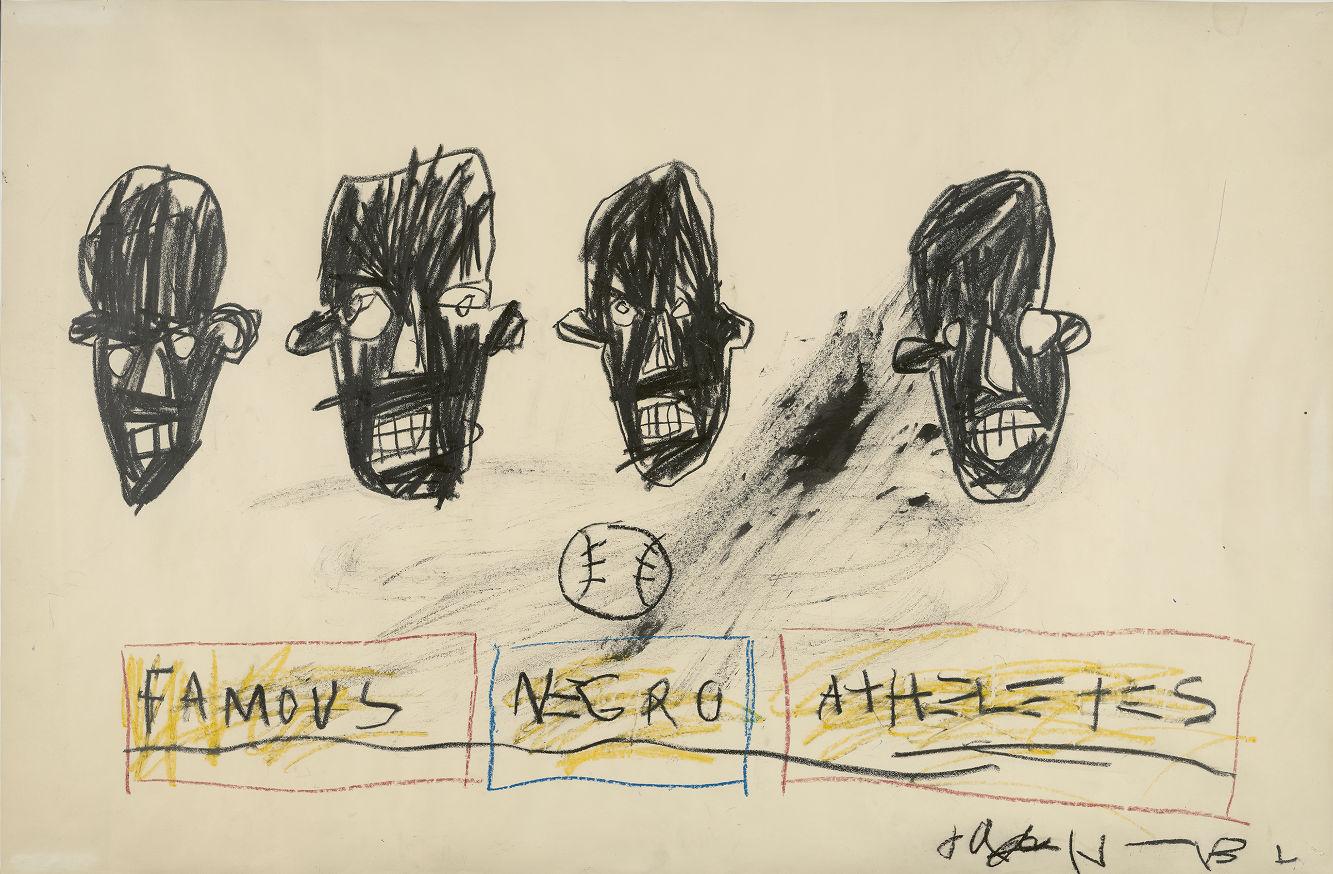

BASQUIAT’S WORLD: WORKS FORMERLY FROM THE COLLECTION OF FRANCESCO PELLIZZI

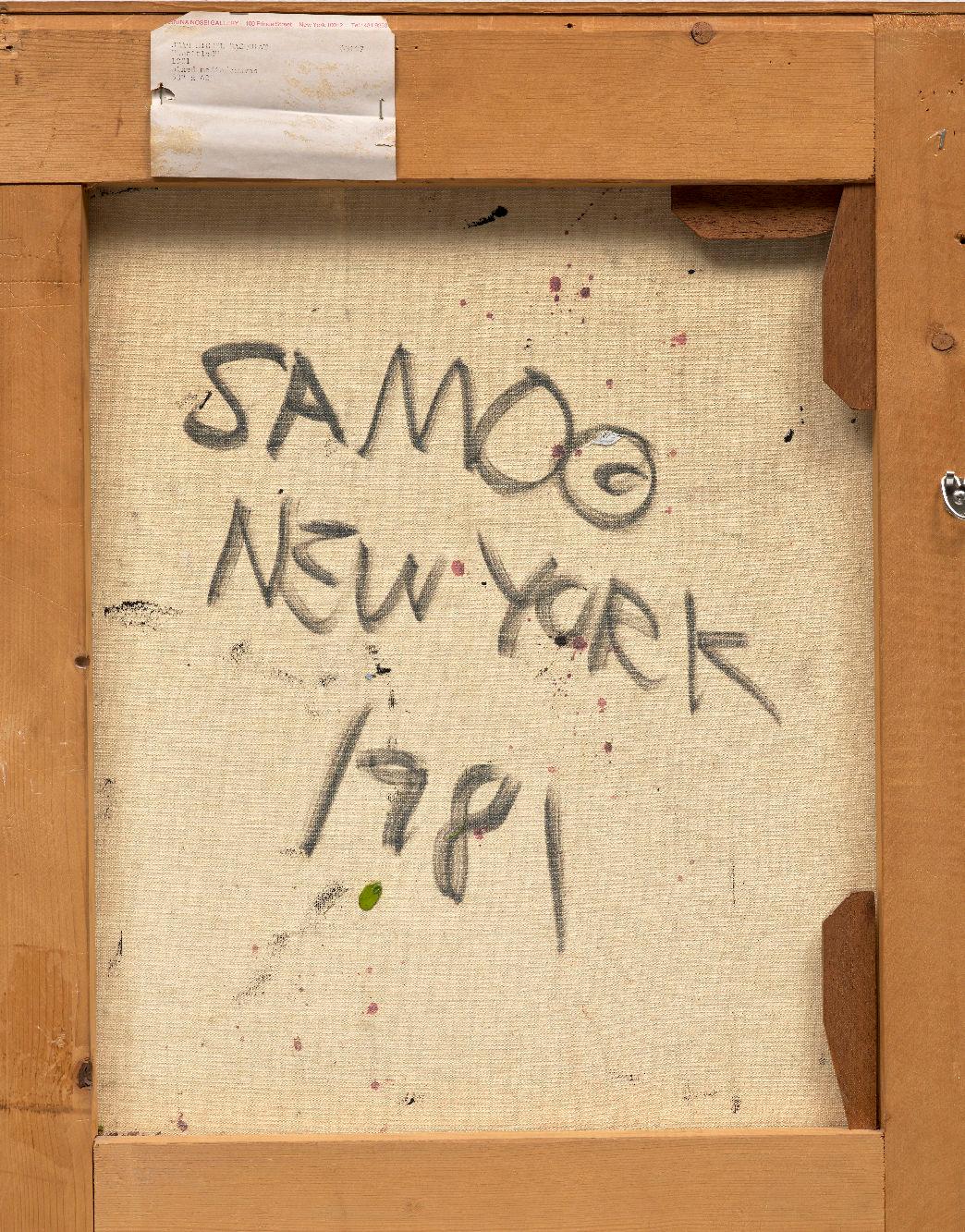

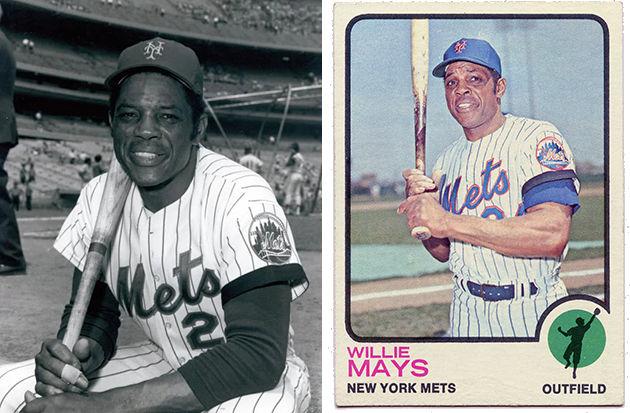

Untitled (Portrait of Famous Ballplayer) signed with the artist's tag, inscribed and dated "SAMO© NEW YORK 1981" on the reverse acrylic, oilstick and Xerox collage on canvas

50 1/8 x 43 1/2 in. (127.3 x 110.5 cm) Executed in 1981.

EstimateEstimate

$6,500,000 — 8,500,000

Video: https://www.youtube.com/embed/SgNWp6AuREQ