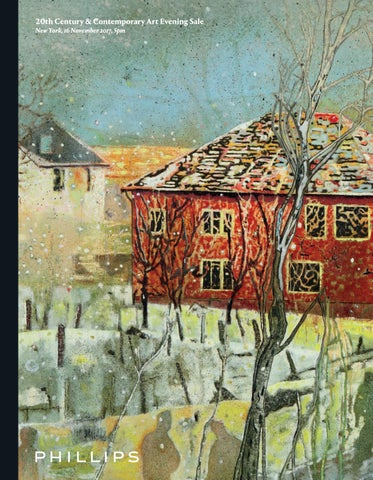

20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale New York, 16 November 2017, 5pm

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV17_Cover_BL2.indd 4

23/10/17 16:04

20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale New York, 16 November 2017, 5pm

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV17_Cover_BL2.indd 4

23/10/17 16:04