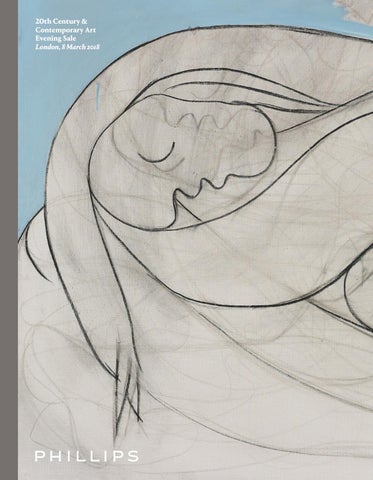

20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale London, 8 March 2018

20TH CENTURY & CONTEMPORARY ART EVENING SALE [Catalogue]

Issuu converts static files into: digital portfolios, online yearbooks, online catalogs, digital photo albums and more. Sign up and create your flipbook.