THE DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS BETWEEN THE PHILIPPINES AND FRANCE DID NOT MERELY BEGIN OVER 70 YEARS AGO.

H

sr

DO

&r

OB

2?

aif

»nwn B &)

50»

« 1* 0*

The

PHILIPPINES and FRANCE

DISCOVERY REDISCOVERY

gz n

El

THE PHILIPPINE EMBASSY IN FRANCE

pffi

THE PHILIPPINES AND FRANCE: DISCOVERY, REDISCOVERY

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 1

5/7/19 8:47:16 PM

THE PHILIPPINES AND FRANCE: DISCOVERY, REDISCOVERY © 2019 by the Embassy of the Republic of the Philippines in France Copyright for the various illustrations and documents rest with the institutions or individuals concerned.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage and retrieval system without permission by the respective copyright holder.

AILEEN S. MENDIOLA-RAU Editor

MAY TOBIAS PAPA Book Design

This book was printed and bound in APRIL 2019 by Imprimerie Chirat - Saint Just la Pendue 42540 - FRANCE

ISBN No. 978-2-9564741-1-1

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 2

5/7/19 8:47:17 PM

THE PHILIPPINES AND FRANCE: DISCOVERY, REDISCOVERY

Celebrating 70 Years of Philippines–France Relations

2019

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 3

5/7/19 8:47:17 PM

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 4

5/7/19 8:47:18 PM

Message by Ambassador Ma. Theresa P. Lazaro Message by Ambassador Nicolas Galey

Part

1

The Unknown and Known: Maps, Myths, Early Contacts, and Initial Cooperation I

INITIAL FIRST ENCOUNTER WITH THE ISLES PHILIPPINES From the Atlas Vallard (1547) to d'Anville's 18th Century Maps: Cartographers and Sailors

3

II

COOPERATION AND DREAMS From César de Bourayne (1807) to the Basilan Adventure (1844-1845)

20

III

THE PHILIPPINES' FIRST PARTNERSHIP WITH FRANCE The 'Chasseurs Tagals' (Tagal Rangers) and the French Conquest of Cochinchina (1858-1863)

39

Part

2 rance

José Rizal and the Filipino Elite in F JOSÉ RIZAL AND FRANCE The Pendulum of a Cultural Encounter

61

II

RIZAL'S NETWORKS IN FRANCE

71

III

RIZAL AFTER RIZAL IN FRANCE

81

IV

RETRACING JOSÉ RIZAL'S FOOTSTEPS IN FRANCE

90

Part

I

3

The Making of Bilateral Political Relations: 1824-1947 I

THE PREMISE: THE FIRST WESTERN CONSULATE AND FRENCH CONSULS IN THE PHILIPPINES 1824 AND 1836 AND BEYOND

141

II

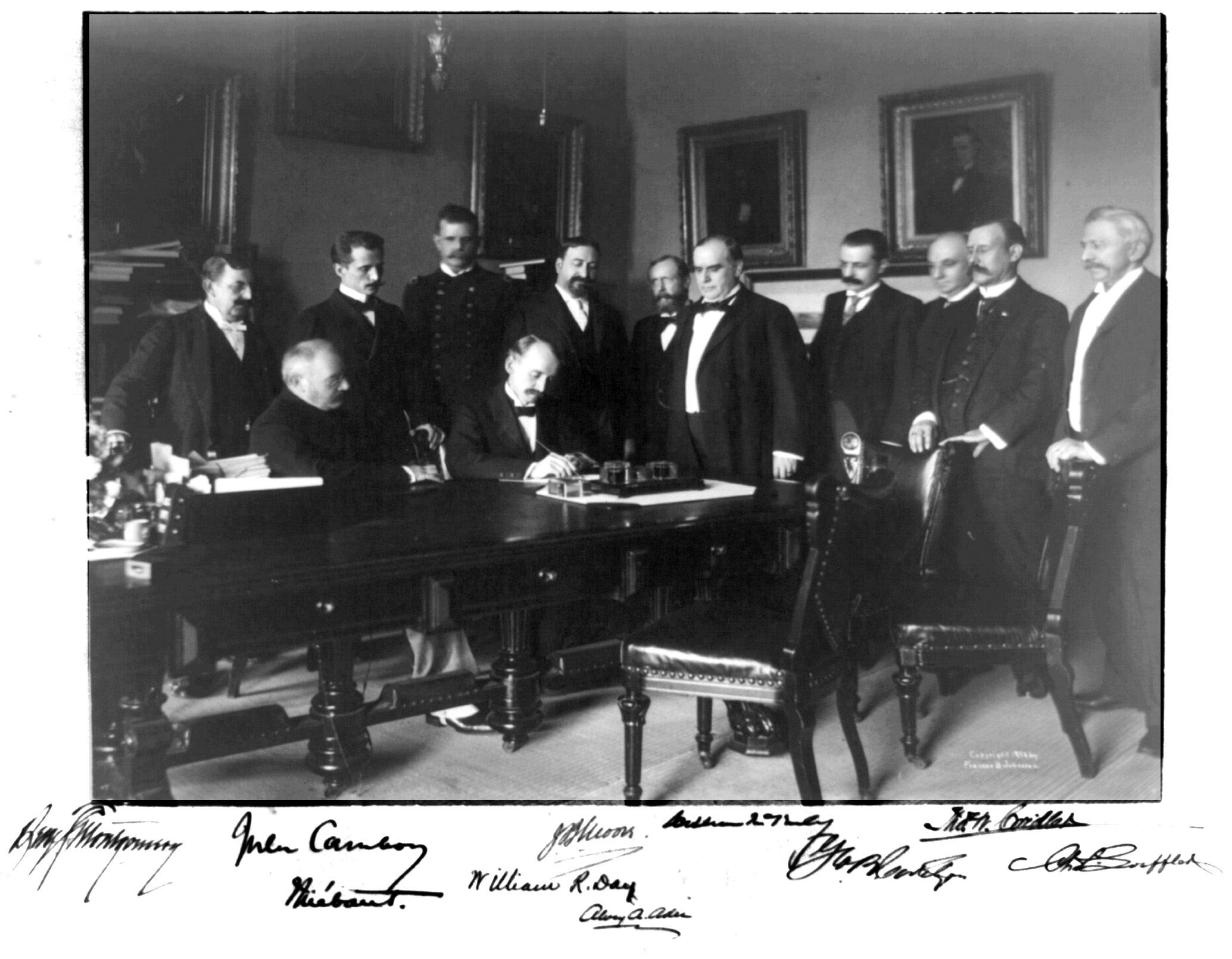

TREATY OF PARIS AND THE FILIPINO DIPLOMATS IN PARIS

151

III

THE INDOCHINESE STAKE AND THE 1947 TREATY OF FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THE PHILIPPINES AND FRANCE

169

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 5

5/7/19 8:47:19 PM

IV

MANILA AND THE END OF FRENCH INDOCHINA

177

V

SEATO, THE PHILIPPINES, AND FRANCE

180

Part

4

Nurturing Friendship: 1947-2017 I

THE ROAD TO FRIENDSHIP The Signing of the Philippines-France Treaty of Friendship

II

STEADY GROWTH IN THE RELATIONS

205

III

FRENCH AND PHILIPPINE RELATIONS (2012-2017) by Ambassador Christian Lechervy

242

the value added by france in the sustainable socioeconomic development in the philippines by Mr. Anton T. Huang, Chairman of the Philippines-France Business Council

264

IV

Part

195

5

Cooperation in the Global Arena: Shaping a More Just and Equitable World I

THE "SPIRIT OF PARIS" AS INSPIRATION FOR UNESCO

273

II

THE PHILIPPINES AT UNESCO 2015-2017

275

III

A CONSTITUTION FOR THE RIGHTS OF ALL

281

IV

JOINTLY FACING THE CHALLENGE OF OUR TIMES: CLIMATE CHANGE

286

v

AREAS OF CONTINUING COOPERATION

289

Part

6

Crossing Cultures: Filling Gaps and Bridging People I

GUSTAVE EIFFEL AND THE PHILIPPINES

295

II

PHILIPPINES AND PARIS EXPOSITIONS

315

III

INSPIRATION BEHIND THE NOTES OF THE PHILIPPINE NATIONAL ANTHEM

324

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 6

5/7/19 8:47:19 PM

IV

FRENCH INFLUENCES IN THE 1898 MALOLOS BANQUET

326

v

40 YEARS OF FRIENDSHIP IN BRITTANY: PAINTER MACARIO VITALIS IN PLESTIN-LES-GRÈVES by Mayor Christian Jeffroy and Ms. Jeanne Eliet (Translated into English by Ms. Laetitia Groszman)

333

VI

VITALIS AND THE PHILIPPINE EMBASSY

343

vII

PHILIPPINE ARTIFACTS AND ARTWORKS SHOWCASED IN HISTORIC EXHIBITION AT THE MUSÉE DU QUAI BRANLY

347

ART AND ENVIRONMENT: CAPTURING LIFE'S PERPETUAL FLUX Sculptor Impy Pilapil in Neuilly-sur-Seine

351

PHILIPPINE-FRENCH COOPERATION IN PREHISTORIC ARCHAEOLOGY by Omar Ochoa, PhD

356

UNIVERSITY EXCHANGES BETWEEN FRANCE AND THE PHILIPPINES by Fr. Pierre de Charentenay, SJ

360

T HE TEACHING OF THE FILIPINO LANGUAGE TO FRENCH NATIONALS by Prof. Elisabeth Luquin

362

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A COOPERATIVE PLATFORM BETWEEN THE PHILIPPINES AND FRANCE

364

T RACING THE HISTORY OF THE FILIPINO DIASPORA IN FRANCE

367

Epilogue: OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE

377

List of Agreements

381

Bibliography

391

Acknowledgements

411

Project Team

418

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 7

5/7/19 8:47:19 PM

It is

P write of it of

MA. THERESA P. LAZARO Ambassador of the Republic of the Philippines to France and Monaco Permanent Delegate to UNESCO

22

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 8

5/7/19 8:47:21 PM

It is evident that there is a dearth of published materials that chronicle Philippines-France relations from the pre-Hispanic times to the present. It is with this gap in mind that the Philippine Embassy in Paris has undertaken to write and publish this book about the history of Philippines-France relations and to launch it in time for the celebration of the 70th year of the establishment of diplomatic relations. The book begins with French perceptions of the Philippines from the 15th century onwards by way of cartographic works with French and Philippine history set as a backdrop. Thereafter, it continues with the progression of discussions on the life and works of Philippine National hero, Dr. José Rizal, as well as other Philippine reformists, intellectuals and ilustrados who lived in France in the late 19th century. The Philippine Revolution of 1896 provided the platform for the role of the Filipino diplomatic mission in Paris during the negotiations on the Treaty of Paris of 1898, and the eventual establishment of formal diplomatic ties on 26 June 1947. The book will also explore the myriad facets of diplomatic bilateral cooperation over the past 70 years which is intertwined with the Philippines and French interactions in the global multilateral arena. It is the hope of the Philippine Embassy in Paris that this well-researched book will serve as reference material for the future students, academicians as well as historians on Philippine–France relations. It is indeed the documentation of events of the two countries which will provide a better understanding between its peoples, though distant in terms of distance, but affectionate towards each other in terms of people-to-people relations. I wish to acknowledge Minister and Consul General Aileen S. Mendiola-Rau, who shepherded the completion of this book with the assistance of various Philippine and French institutions and personalities. Together, Philippines and France can face the challenges of the next seven decades by understanding each other, collaborating and creating synergies towards a better world.

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 9

5/7/19 8:47:21 PM

Je salue la réalisation de cet ouvrage dense et ambitieux qui met en lumière les liens développés entre la France et les Philippines depuis le XVème siècle jusqu’à nos jours. Ses différents chapitres illustrent la profondeur historique et la diversité des relations tissées entre nos deux pays dans tous les domaines, tant sur le plan institutionnel que sur celui des échanges intellectuels et humains. Sa lecture permet de mieux mesurer l’ancienneté des contacts entre Français et Philippins à l’époque des grands navigateurs comme durant la période coloniale française en Indochine. L’ouvrage montre aussi combien, au XIXème siècle, les jeunes intellectuels philippins épris de liberté ont été inspirés par les idées et les idéaux hérités des Révolutions de 1789 et de 1848. Ainsi José Rizal, héros national, et premier des « Illustrados » a-t-il, lors de son séjour à Paris, forgé les fondements de la revendication nationale et démocratique philippine. Aujourd’hui, la relation franco-philippine, portée par cet héritage humaniste commun, est caractérisée à la fois par de fortes affinités culturelles et un attachement partagé aux valeurs de l’État de droit, du multilatéralisme et du droit international. Cet attachement se manifeste concrètement face aux grands défis contemporains que constituent les questions environnementales et climatiques ainsi que la consolidation d’un développement humain durable. Dans ces domaines, la France et les Philippines ont démontré leur capacité à se mobiliser pour agir ensemble et faire progresser des causes essentielles. Un véritable partenariat s’est ainsi noué entre nos deux pays sur la question du dérèglement climatique, symbolisé par le lancement conjoint de « l’Appel de Manille à l’action pour le climat » à l’occasion de la visite d’État du président François Hollande aux Philippines en février 2015. Et c’est à cette occasion qu’est née « France-Philippines United Action » (FP- UA), initialement créée pour coordonner l’aide française au lendemain du terrible typhon Haiyan en novembre 2013. Cette fondation - la première du genre portée par une

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 10

5/7/19 8:47:21 PM

NICOLAS GALEY

Ambassadeur de France aux Philippines, en Micronésie, aux Îles Marshall et à Palau, en résidence à Manille

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 11

5/7/19 8:47:22 PM

Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie française - symbolise aujourd’hui la solidarité des entreprises françaises présentes aux Philippines et continue, cinq ans après la catastrophe, à agir pour inscrire son action dans la durée. Parallèlement, l’Agence française de développement conduit, fréquemment en partenariat avec l’Union Européenne, les agences de l’ONU ou la Banque asiatique de développement, des actions qui contribuent concrètement à la modernisation et au développement des Philippines. Au-delà des échanges d’État à État initiés dès 1824 entre nos deux pays, les relations entre la France et les Philippines bénéficient d’une dynamique forte dans de nombreux secteurs. Nos relations économiques et commerciales ont connu une progression spectaculaire au cours des dernières années, favorisée par une croissance philippine parmi les plus élevées d’Asie. Nos deux peuples partagent en outre la passion du cinéma, de la musique et de la danse, ainsi que de la cuisine. Ce patrimoine culturel commun nourrit une coopération diversifiée qui a vocation à s’élargir encore à la faveur du développement des technologies de l’information et de la communication. Les échanges entre nos deux sociétés civiles n’ont par ailleurs jamais été aussi denses. L’intérêt des Français pour les Philippines est fort, comme l’a démontré la grande affluence dont a bénéficié l’exposition du musée du Quai Branly à Paris consacrée, en 2013, à « l’Archipel des échanges ». De nombreux chercheurs français anthropologues, archéologues, sociologues, linguistes, océanographes, biologistes ou encore vulcanologues - consacrent leurs travaux aux Philippines. Dans ce contexte, et alors que se développent les communautés philippine de France et française des Philippines, la promotion de la francophonie aux Philippines, portée notamment par le Lycée français de Manille ainsi que les Alliances françaises de Manille et de Cebu, est plus que jamais une priorité. C’est un facteur-clé pour le développement de nos échanges d’étudiants et de chercheurs. Après plus de soixante-dix ans d’une relation franco-philippine qui n’a cessé de se densifier, je forme le vœu que nos deux pays continuent d’agir ensemble sur le plan institutionnel et que nos deux peuples approfondissent encore les liens amicaux et fraternels qui nous unissent depuis des siècles. Les échanges universitaires qui s’accroissent comme l’implication active de jeunes Français dans des actions de développement aux Philippines montrent que la relève est assurée et que les héritiers de Rizal et de 1789 sont toujours plus nombreux à se rencontrer et à partager pour relever les défis de ce siècle.

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 12

5/7/19 8:47:22 PM

1 THE UNKNOWN AND KNOWN: MAPS, MYTHS, EARLY CONTACTS, AND INITIAL COOPERATION

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 13

5/7/19 8:47:23 PM

2

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 14

5/7/19 8:47:25 PM

I

INITIAL FRENCH ENCOUNTER WITH THE ISLES PHILIPPINES From the Atlas Vallard (1547) to d’Anville's 18th Century Maps: Cartographers and Sailors

Centuries before the formal establishment of its diplomatic relations

with the Philippines in 1947, as early as a few decades after the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama’s successful circumnavigation of Africa, and more than half a century even before the British1 sailed the world, France had long already been engaged in developing trade opportunities with the New World and the Far East. The ports of Normandy were the first in France to engage in long distance oceanic trade due to their strategic location along the Atlantic coast and mouth of the river Seine, as well as their long-standing tradition of trade with Portugal, the Netherlands and Britain. France’s King Francis I ordered the construction of the port of Le Havre2 in 1517. His decision defied the Treaty of Tordesillas signed in 1494 that divided lands “discovered” by European explorers between the Portuguese and Spanish crowns along the meridian between the Cape Verde Islands and the West Indies. When Ferdinand Magellan set off for the Far East, his crew included seventeen Frenchmen. Unfortunately, none of them completed the circumnavigation. Throughout this period, the old ports of Dieppe in Normandy gained prominence, thanks to the business activities of Jean Ango,3 who was then the wealthiest French ship owner with a fleet of twenty-one ships. Three of the ships in his fleet were Spanish caravels captured from the command of conquistador Hernán Cortés. The vessels were transporting treasures of the last Aztec emperor Cuauhtémoc, en route to the Spanish King and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, when Ango’s Captain Jean Fleury intercepted them. 3

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 15

5/7/19 8:47:25 PM

Apart from funding numerous voyages to the New World, Aztec gold enabled several expeditions to East Asia. Jean and Raoul Parmentier4 were the first Frenchmen to pass the Cape of Good Hope and reach Southeast Asia by their own means. The brothers died in 1529 along the western coast of Sumatra. Portolan navigational charts and itineraries (roteiros in Portuguese) —navigational maps highly prized by traders, admirals, and most importantly, kings—were strategic items regarded as state secrets by both ship owners and political authorities. When France was at war with Spain between 1521 and 1559, French navigators obtained data from privateers licensed to attack enemy ships, Portuguese travelers, and tavern gossip5 to create the first French portolan charts6 in the port town of Dieppe. The first three quarters of the 16th century witnessed the height of the French school of cartography. Taking into account the number and scope of dissemination of maps and charts, France ranked only after Portugal and Germany in terms of importance in cartography. To date, around fifteen 16th century maps survived. Except for those made by Oronce Fine, professor at the prestigious and then newly founded Collège de France in Paris, cartographers from Normandy produced most of the French world maps. Jean Mallard of Rouen and Guillaume Le Testu of Le Havre were two of the renowned cartographers from the Normandy region.

A.

The appearance of the Philippine archipelago in French cartography The first French portolan chart that depicted the west coast of Borneo and parts of Mindanao’s south coast, including what could be interpreted as Palawan’s east coast, was drawn by Nicolas Desliens in 1541 (Figure 1). Although with a less accurate sketching than Deslien’s, Jean Roze7 of Dieppe mentioned—for the first time—the toponyms of Mindanao, Negros, and Sulu, in his 1542 atlas8 (Figure 2) which was dedicated to King Henry VIII of Britain, one of the main rivals of King Francis I. Due to the difficulties of communication and the resilience of the Ptolemaic imago mundi,9 French knowledge of Southeast Asia did not progress in a consistent manner. Guillaume Brouscon’s 1543 map, omitted the Philippines entirely, as did Jean Cossin’s10 1570 atlas. In 4

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 16

5/7/19 8:47:25 PM

Figure 1. Nicolas Desliens, Planisphère, 1541, extract. The North being at the bottom of the map (following ancient Arabic cartography).

Figure 2. Jean Roze, Boke of Idrography [Book of Hydrography], 1542-46 (f. 9v°-101), extract. Here the North is shown at the bottom of the map. Toponyms mentioned in the legend are written on the map. 5

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 17

5/7/19 8:47:28 PM

Figure 3. Extract of Atlas Vallard (1547). According to the original map, the North is at the bottom of the map.

1547, the beautifully illustrated Atlas Vallard,11 attributed to French navigator and cartographer Nicolas Vallard (Figure 3) included to the north of Borneo, a quadrangular island with several toponyms including ‘Balanpecan’ (Balambangan?), located next to a huge island called the Archipelago of San Lazaro—the name given by Magellan. The Atlas Vallard did not use the appellative ‘Filipinas’ given by Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos in 1544 to Samar or Leyte to honor the Crown Prince of Spain, the future Philip II. On the other hand, Pierre Desceliers’ nautical planispheres of 1546 and 1550,12 dedicated to King Henry II and the heads of the French army and navy,13 mentioned Mindanao, Sulu, and parts of Visayas. The ports of Normandy declined after 1570 and ceded their prominence to the ports of Brittany and La Rochelle, which then dominated oceanic trade. As a result, Paris became the center of French nautical science. Closer to the royal court and to intellectual Parisian networks, the French cartographers improved their knowledge of the Philippine archipelago. The 1575 map of François de Belleforest and the 1582 atlas of Lancelot Voisin de la Popelinière in 1582 only mentioned “Palohan”14 (Palawan), Mindanao and “Pauvodas”.15 However, it was the Franciscan priest and explorer Father André Thevet,16 Franciscan priest and explorer, who published in 1584 a planisphere that placed an island ‘Philipines’ (sic) in the middle of the Archipelago of ‘Saint Lazare’ (Figure 4). Following Thevet’s 6

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 18

5/7/19 8:47:29 PM

Figu

work, the cosmographic research ceased, with the publication of only three minor works between 1585 and 1601. The exhausting religious wars between Protestants and Catholics (1562- 1598) and the war with Spain (1595-1598) drained most of the resources of the French elite that financed cartographic works.

B.

17th century: The naming of the Philippines The 17th century ushered in a new era for navigation following the return of peace in the French kingdom and the creation of the short-lived Compagnie française des mers orientales (French Eastern Seas Company) in 1600. Friendly relations with the United Provinces (today the Netherlands) allowed the French cartographers to collaborate with the new masters of the art, the Dutch—who benefited from German scientific expertise and who founded the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Dutch East-India Company or VOC) in 1601. Despite these developments, French cosmography did not keep abreast of the times. In 1561, Italy’s Giacomo Gastaldi became the first geographer to have included a ‘Luzon’ island in his cartography. In 1592, Dutch scholars, such as Petrus Plancius,17 designated ‘Philipinae’ and ‘Luconia’ (Luzon) with Latin appellations in their

Figure 4. André Thevet, Carte des provinces de la grande et petite Asie (excerpt), 1584 (Bibliothèque nationale de France) 7

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 19

5/7/19 8:47:30 PM

maps. However, the two maps created for French publisher Jean Le Clerc in 1602 by the Dutch Jodocus Hondius18 had no reference to Luzon at all. Moreover, between 1603 and 1626, the French were unable to produce proper world maps. King Louis XIII’s19 young age and recurring conflicts with the Hapsburg monarchs who blockaded France between its Northeastern (Flemish) and southwestern (Spanish) borders were major factors. Dutch scholars eventually revived and revitalized French cartography, which had the support of the Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu. The Cardinal, who was also Prime Minister, signed the Treaty of Compiègne with The Netherlands in 1624, advocated free trade with both the West and East Indies, and who later formed a professional royal navy. Between 1627 and 1630, half a dozen atlases and planispheres were published in Paris in collaboration with Dutchtrained scientists such as Petrus Bertius,20 Cornelis Danckerts, and Jodocus Hondius. Thanks to their contributions, the toponym Luzon (as Luconia) finally entered French cartography, along with three dozen more toponyms, including Manila (Figure 5, Petrus Bertius, 1627). While the Philippines21 was now marked distinctly from the Archipelago San Lazaro (L’archipelage de S. Lazare, the future Marianas Islands, Figure 5), and the Paracel Islands were correctly placed, the shapes of its two main islands, Luzon and Mindanao, remained incorrect. Luzon lacked the contemporary provinces of Quezon and Camarines Norte, which were depicted instead as two distinct islands cut off from Luzon by an imaginary ‘Strait of Manila’. Meanwhile, Mindanao was drawn too close to Luzon on its eastern side. Moreover, the cartographer had used the name Solor instead of Solo (Sulu), confusing it with an island named Solor located in present-day eastern Indonesia. He also confused Samar (then called Achan22) with the southern part of Luzon. Driven by the European competition for long-distance trade, French cartographic production flourished well into the last years of Louis XIV’s reign. Twenty-seven world maps and atlases were created between 1631 and 1660; eighteen between 1661 and 1690; and twenty-two between 1691 and 1715—or an average of one publication per year. The 1659 Treaty of the Pyrénées, which heralded the peace between France and Spain, contributed to the foundation of the Compagnie des Indes orientales (East India Company) in 1664 and generated high demand for charts. 8

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 20

5/7/19 8:47:31 PM

Figure 5. Petrus Bertius, Carte de l’Asie corrigée, et augmentée, dessus toutes les autres cy devant faictes par P. Bertius – Melchior Tavernier, 1627 [Corrected and increased map of Asia, which supersedes all previous maps made by P. Bertius], extract, 1627.

9

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 21

5/7/19 8:47:32 PM

Figure 6. Pierre du Val, Carte universelle du commerce (1674), extract, showing Philippines as part of East Asia maritime roads.

Also in 1664, the scientist Melchisédech Thévenot23 published accounts of his travels in French. His second volume included four accounts relating to the Isles Philippines,24 which he translated from Spanish. Thanks to Thévenot, stories about the islands found their way into French travel literature, reaching a much broader audience than plain cartographic works. The Philippines inevitably became part of the Bourbons’ commercial ambition. Pierre du Val’s Carte universelle du commerce (Universal Map for Trade), published in 1674 (Figure 6), traced the sea lanes from the French ports to Manila. A few years later, Alain Manesson Mallet included the archipelago in his Description de l’Univers (1683), devoting several pages to his descriptions of the country,25 a map (Figure 7), and a sketch of Manila Bay (Figure 8). 10

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 22

5/7/19 8:47:33 PM

Although the French elite became increasingly interested in Eastern Asia, French mapping of the Philippines remained imprecise. Most cartographers either copied or completed the works of their predecessors, without updating their research. As an example, Alexis-Hubert Jaillot reproduced 40 years later in 1692, most of Nicolas Sanson’s 1652 Asia map in his L’Asie Divisée en ses Principales Régions (Main Regions of Asia).

Figure 7. Map of the ‘Isles Philippines’(1682) A. Manesson-Mallet, Description de l’Univers (Bibliothèque nationale de France) 11

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 23

5/7/19 8:47:34 PM

Figure 8. Sketch of the Manila Bay showing present-day Intramuros (id.) A. Manesson-Mallet, Description de l’Univers (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

12

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 24

5/7/19 8:47:37 PM

C.

The Philippines and 18th Century French Exploration of the South China Sea The works of Jean-Dominique Cassini, 26 an astronomer and mathematician of the Royal Observatory and the Academy of Sciences, and his father Jacques,27 introduced advances in geodetic calculations. Because of their scientific legacy, the quality of French cartographic works improved during the first half of the 18th century. The return of the first cargoes sent by the Compagnie des Indes from Canton (present-day Guangzhou, China) inspired in France a renewed interest in the South China Sea. In 1705, Noël Danycan de l’Épine, the wealthiest trader and privateer from Brittany, implored the Navy Minister—albeit without success—to send three ships to “Mindanao and other islands uncontrolled by European powers”.28 The 1705 Carte des Indes & de la Chine [Map of Indies and China] (Figure 9), published by Guillaume de l’Isle, a follower of JeanDominique Cassini, a member of the Académie des Sciences, and the King’s first geographer, displayed progress in the French knowledge of the Philippines. In de l’Isle’s map, the layout of the Visayas islands (in particular, that of Samar and Leyte), and the western part of Mindanao proved remarkably accurate. However, the size and location of the “Nouvelles Philippines” (Caroline Islands) remained a mere product of the imagination. The illustrated islands were smaller and farther to the east than their approximate location. The Manila Galleons, which remained the sole link between Spain and the Philippines until 1762, nurtured French ambitions, as illustrated by Nicolas de Fer’s 1713 map (Figure 10), presenting various routes between Manila and Acapulco. Capturing the fabulous galleons remained an elusive dream for the French. Not only did France forge an alliance with Spain and a Bourbon king, Philip V, ascended the Spanish throne in 1700, but also the cost of thirteen years of war with England, Austria, and the Netherlands drained the French treasury. Moreover, the Treaty of Utrecht ending the hostilities in 1713 forbade foreign ships from entering ports controlled by the Spanish crown.29 13

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 25

5/7/19 8:47:37 PM

Figure 9. Guillaume de l’Isle, Carte des Indes & de la Chine [Map of the Indies and China], extract, 1705 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Figure 10. Nicolas de Fer (1713) Carte de la Mer du Sud et des costes d’Amerque [sic] et d’Asie, situées sur cette mer [Maps of the Southern Sea and coast from America and Asia, located along this ocean …], extract showing sea lanes (Bibliothèque nationale de France) 14

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 26

5/7/19 8:47:39 PM

Yet, despite the various setbacks, the French cartographic school in the 18th century eventually took precedence in Europe largely due to the work of three great cartographers. The first one, Jean-Baptiste d’Anville,30 was appointed as king’s geographer in 1718 and revolutionized French cartographic production by systematically collecting available maps and documentation, and eventually assembled the biggest geographical database of the century. His collection included some 67 maps relating to the Philippines alone. In 1752, he published a detailed map of the archipelago (Figure 11) in his Seconde partie de la carte d’Asie… (Second part of the map of Asia…).

Figure 11. Jean-Baptiste d’Anville (1752), Seconde partie de la carte d’Asie … [Second part of the map of Asia...] (Bibliothèque nationale de France) 15

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 27

5/7/19 8:47:42 PM

The second world-renowned cartographer was Jean-Baptiste d’Après de Mannevillette.31 J. B. d’Après, who trained in mathematics and studied geography under Guillaume de l’Isle, worked as an officer for the Compagnie des Indes in India and South China. Using an octant, a navigational instrument first developed by the British that allowed for a more accurate measurement of longitudes, J.B. d’Après methodically created new nautical maps of the coastal regions that he had visited, which he gathered in 1745 into Neptune Oriental, a navigational atlas containing twenty-two charts. In 1762, J.B. d’Après became the director of l’Orient, a repository of maps and charts founded by the Compagnie des Indes in its main port, Lorient. In February 1763, the Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years’ War,32 where the French and Spanish colonial establishments were pillaged by the British. Manila fell to Britain in 1762. Alexander Dalrymple, who was then the hydrographer of the East India Company stayed in Manila until the dissolution of the company. On his way back to London, Dalrymple visited Sulu. Elected as a fellow of the Royal Society in 1765, Dalrymple started working on nautical charts, and published a first set thereof in 1772. During this period, Dalrymple and J.B. d’Après nurtured their scientific collaboration.33 J.B. d’Après’ Neptune Oriental34 was reprinted in 1775,35 having been updated and expanded to include sixty three maps. Four of the sixty-three maps were reproductions of A. Dalrymple’s works on the Philippines: “Chart of the China Sea inscribed to Monsieur d’Après de Mannevillette, the ingenious author of Neptune Oriental as a tribute due to his labours to the benefit of Navigation and in acknowledgment of his many signal favours to A. Dalrymple” (No. 52);36 “Maps of the Ports of Borneo and the Soloo Archipelago” (No. 54); “Chart of Felicia and the Plan of the Island of Balambangan” (No. 55); and “The Soloo Archipelago” (No. 56). Among J.B. d’Après’ own works included in the second Neptune Oriental were several maps of Philippines ports: “Plan de la baie de Manille [Chart of Manila Bay]” (No. 58); “Plan des principaux ports de la côte d’Illocos en l’isle de Luçon [Chart of the main ports of Ilocos coast on Luzon Island]” (No. 57); and “Plan du port de Subec [Chart of Subic port]” (No. 59, reproduced Figure 12), the latter having been first published separately.

16

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 28

5/7/19 8:47:42 PM

Figure 12. J.B. d’Après de Mannevillette (1766), Plan du port de Subec [Map of Subic Port] (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

17

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 29

5/7/19 8:47:43 PM

Figure 13. Jacques-Nicolas Bellin (1764), Carte des isles Philippines 2e feuille [Map of Philippine Islands, f. 2], Petit Atlas Maritime, vol. III n°66 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Figure 14. Map of the port of Zamboanga, manuscript, unpublished, January 1772, Collection d’Anville (Bibliothèque nationale de France) 18

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 30

5/7/19 8:47:43 PM

J.B. d’Après' main competitor was the French king’s hydrographer, Jacques-Nicolas Bellin. In 1751, Bellin edited J.B. d’Après’ first chart of the ‘Oriental Ocean’ in the former’s Atlas Maritime. Bellin’s Petit Atlas Maritime (1764, with 580 charts spread in five volumes) presented two detailed maps on the Philippines (North and South, Figure 13). These maps were based on Father Murillo Velarde’s cartographs, which appeared in inferior quality than those of J.B. d’Après' charts because of their less accurate measurements of the longitudes.37 Although Spain lifted in 1766 the prohibition for foreign ships to dock in Spanish colonies, trade with the Philippines remained a Spanish monopoly. However, détente with Britain provided the impetus for a number of major French scientific expeditions to the Pacific. For instance, Guillaume Le Gentil de la Galaisière, an astronomer and a member of the French Academy of Sciences, stayed in Manila from August 1766 to February 1768.38 While the first French circumnavigation of the world occurred between 1766 and 1769 under the helm of Count Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, this expedition did not anchor in the Philippines. Its success, however, paved the way for the launching of smaller ventures, one of which reached the Philippines in 1771. The aim of the voyage was to collect spices and cultivate them in the Isle-de-France (present-day Mauritius) in order to put an end to Dutch monopoly on highly valued spices like cloves and nutmegs. During the ship’s brief sojourn in Manila and its neighboring regions, naturalist Pierre Sonnerat39 collected plants and animals of various species. Thereafter, the expedition embarked on a journey to Mindanao. The hydrographer on board the ship Le Nécessaire drew the maps of Zamboanga (Figure 14) and Sulu, and presented them to Jean-Baptiste d’Anville. Thus, the French elite who read the writings of Sonnerat finally became familiar with the Philippines while a few French traders, such as Gilles and Hippolyte Sébire,40 moved from Macau to settle in Manila at the end of 1784.

19

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 31

5/7/19 8:47:44 PM

II

COOPERATION AND DREAMS From César de Bourayne (1807) to the Basilan Adventure (1844-1845)

A.

FRANCE’S FIRST COOPERATION WITH THE PHILIPPINES

Figure 15. Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Fuendetodos, 1746 – Bordeaux, 1828) L’Assemblée de la Compagnie royale des Philippines, 1815 Huile sur toile, 3,205 x 4,335 cm Legs Pierre Briguiboul 1894 (c) Ville de Castres—Musée Goya, musée d’art hispanique – Cliché François Pons

20

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 32

5/7/19 8:47:46 PM

François de Cabarrus and the Real Compañía de Filipinas

W

hen Spain joined France in supporting the American war for independence, it substantially increased the deficits of the royal finances. To support the borrowings by the Spanish Crown, the Franco-Spanish businessman François de Cabarrus41 aka Francisco de Cabarrús, developed promissory notes that were issued by the Spanish treasury in 1779, then rebuilt the Banco de San Carlos in 1782.42 A year later, he proposed to mitigate the losses of the Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas by linking Spain’s trade with America to that of the Philippines. In March 1785, King Charles III officially launched the Real Compañía de Filipinas43 (Compagnie royale des Philippines)44 which had a 25-year monopoly of the Philippines’ trade with China and Spain. Its commerce with Spain, however, was conducted only through the Cape of Good Hope. Although Real Compañía de Filipinas’ trade was thriving, it did not abolish the galleon to Acapulco because the company needed the port of Veracruz in Mexico.45 The company established its main offices in Manila and Madrid, and set up a factory in Canton. Manila traders firmly opposed the opening of the Real Compañía de Filipinas, vehemently refused to subscribe to the 3,000 shares allocated to them, and declined to avail of the shipping facilities offered by the company.46 A Renewed Interest in the Philippines: French Expeditions to the Pacific Ocean The creation of the Real Compañía de Filipinas increased the strategic and commercial allure of the Philippines. In 1785, Joseph Antoine Bruni d’Entrecasteaux47 was appointed head of the French naval forces in the Indian Ocean. He was instructed to send ships to the South China Sea, to assess the trade of each western nation with China, to explore the sea routes to Macao and Canton, and to try to establish cooperation with the Spanish forces in Manila. Spain was linked to France by the ‘Family Pact’ since branches of the Bourbon dynasty ran both kingdoms and had been allied to the United States in the recent war. 21

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 33

5/7/19 8:47:47 PM

The French naval squadron in the Indian Ocean comprised only four frigates, since a British-French agreement negotiated after the peace of 1783 stipulated that no large warships could be stationed by either nation east of the Cape of Good Hope. Joseph Antoine Bruni d’Entrecasteaux decided to sail to the South China Sea with two ships: his flagship La Résolution, a large frigate captured in 1781 from the British Navy, and the smaller La Subtile commanded by Scipion de Castries.48 Both left their base in Port Louis (Île-de-France, now the capital of Mauritius) in the summer of 1786. They stayed for some time in Pondicherry, on the Indian coast (north of today’s Chennai), which was the other French stronghold in the Indian Ocean, and sailed further to Batavia (now Jakarta). As adverse monsoon winds made it impossible to proceed straight to Macao across the South China Sea, d’Entrecasteaux decided to sail along the East coast of Borneo, then North of Sulawesi, then across the Moluccas archipelago, and northwards to the Carolines, and finally westwards to Macao via the Straits between Taiwan and Luzon. The frigates then took different routes: d’Entrecasteaux’s La Résolution sailed along the Vietnamese coast, following a French court's decision to initiate a cooperation with the Nguyễn dynasty in order to obtain information on the maritime surroundings of the Annam Empire. Castries’ La Subtile, on the other hand, headed straight to the Philippines. In Manila, Castries found two French ships, the La Boussole and L’Astrolabe whose expedition were under the command of Jean-François de La Pérouse and dispatched by the French king to complete James Cook’s last discoveries in the South Pacific. After crossing the North Pacific, La Pérouse anchored in Manila in February 1787. Castries decided to help La Pérouse, who had lost twenty-one officers and crew members in Alaska. Castries, thus, transferred his two officers and eight crewmembers to the La Boussole and L’Astrolabe. La Pérouse thereafter cruised north along the China Sea, between Korea and Japan, reached the Kamchatka Peninsula (in the Russian Far East), and returned towards Central Pacific before he disappeared in Vanikoro (currently Solomon Islands) around June 1788. In Manila, Castries found the Spanish authorities helpful and inclined to cooperate with the French Navy. He was impressed by the workers and the supplies of their shipyard and praised their land forces, in particular, the cavalry. The Spanish Navy 22

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 34

5/7/19 8:47:47 PM

seemed less promising since the warships were old and obsolete. Admiring the Philippine-bred horses, he bought three of them, which he would later offer to ladies in Port Louis. Then, after a few weeks in the “lovely city of Manila”, Castries and his crew left and sailed back to the French bases in the Indian Ocean. Joining La Pérouse’s expedition as a Russian interpreter was Barthélémy de Lesseps,49 the French Vice Consul in Cronstadt (seaport of St. Petersburg, Russia), who spoke fluent Russian, Spanish and German. Lesseps met La Pérouse’s deputy during a mission to the King’s court in Versailles and La Pérouse decided to bring him since the planned route of his expedition would go through Russian territory. Lesseps was François de Cabarrus’ second cousin, who belonged to the business and diplomatic network in Southern France interested in direct trade between the Philippines and Spain—through the ports of France. Lesseps left La Pérouse in Petropavlovsk (Kamtchatka) in September 1787, and brought to Versailles in October 1788 a secret report on the Philippines.50 In the dossier, Lesseps praised the inhabitants of the Philippines, while deploring the treatment they received from the Spaniards.51 Although the French Revolution caused an interruption on all maritime explorations for more than a decade, the Philippines had slowly become part of the political “worldscape” of the French authorities. The French Revolutionary Wars52 somehow drew a link between the Philippines and France. After the failed invasion of northern Spain by the French Republican armies in 1793 and the beheading of radical revolutionaries in Paris in the summer of 1794, France and Spain signed a peace treaty in Basel, Switzerland in July 1795. François de Cabarrus acted as Spain’s plenipotentiary for the said accord. The hostilities between France and Great Britain escalated when, in January 1795, France invaded the Netherlands and replaced the government of the former Stadhouder Prince Willem van OranjeNassau with an allied Batavian Republic. In retaliation, the British seized part of the Dutch Asian colonies. As the British settled along the banks of the Malacca Strait, French ships started using Batavia as their port of call prior to reaching Macau and Canton. The Treaty of Amiens, signed in March 1802 ended hostilities between France and Great Britain. However, war resumed in May 1803, due to Great Britain’s increasing concern over Napoléon Bonaparte’s political and geographic reshaping of continental Europe. Because of multiple alliances between the two branches of 23

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 35

5/7/19 8:47:47 PM

the Bourbon family, Spain supported France against Great Britain in December 1804. In May 1805, Lord Horatio Nelson defeated the Franco-Spanish fleet along the Cape Trafalgar,53 next to the port of Cádiz. The Dutch East Indies islands (today’s Indonesia), escaped the British subjugation, and passed nominally under French supervision. Former Dutch republican Herman Willem Daendels was appointed as the King of Spain’s Governor-General of the Dutch Indies. The Treaty of Paris of 1806 transformed the Batavian Republic into a subordinate kingdom, with Louis Bonaparte, the emperor’s younger brother, as its head. In May 1808, Ferdinand VII of Spain, who deposed his father Charles IV, was in turn, forced into abdication by Napoléon. A Castilian Council consisting of liberal pro-French elite installed Joseph, Napoléon’s eldest brother, as King of Spain. Although Joseph Bonaparte eventually abdicated in July 1813 in favor of Ferdinand VII, the Spanish war for independence and its atrocities would last until April 1814.

The Money from Acapulco and César de Bourayne’s Exploits At the turn of 19th century, the British became increasingly concerned over the possibility of a French conquest of the Philippines—a fear that was not unfounded. Driven by Louis XVI’s support of Monseigneur Pigneau de Behaine 54 and the restoration of the Nguyễn power in Cochinchina, which was located west of the Philippines, the French interest in Southeast Asia temporarily waned during the collapse of the Ancien Régime from 1789 to 1792. However, in 1793, France regained its interest in the Far East, especially on the Philippines. Three draft reports,55 which circulated among the officials of the Ministry for the Navy, analyzed the stakes and opportunities of a French conquest of the Philippine archipelago. The last of the three documents, dated September 1797 after the signing of the Treaty of Basel of 1795, detailed the most ambitious plan — entitled as the Projet d’établissement aux Philippines et à la Cochinchine (Project for a settlement in Philippines and Cochinchina).56 However, the French Expedition to Egypt in 1798 to 1801, and the losses during the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, prevented the French Navy from strengthening its presence in the Indian Ocean. However, Spain’s alliance to France, allowed French vessels, whose hub was the Isle-de-France along the Indian Ocean, to stop at the port of Manila frequently. 24

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 36

5/7/19 8:47:48 PM

When he arrived in Manila in 1790, Spanish GovernorGeneral Rafael María de Aguilar attempted to reorganize the city’s defense. In January 1804, Aguilar requested General Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen, the French governor of Isle-de-France, for expert artillery support; and he recruited Félix Renouard de Sainte-Croix,57 who arrived in Manila in September 1804, as his aide-de-camp. In response, General Decaen appointed Paul du Camper,58 as the agent for France in Manila, and dispatched the frigate La Sémillante, 59 under the command of Captain Léonard Motard.60 The annual budget of 1,921,000 piasters,61 allotted for the Philippines, was not enough to fund the affairs of the archipelago. Hence, 500,000 piasters were granted yearly by the King of Spain and facilitated through the Acapulco Galleon.62 However, due to the war with Great Britain, which deprived Spain of a large portion of its galleon fleet, Mexico was hindered from providing reinforcements to protect the galleon and other vessels and from remitting money to Manila in 1805. Motard reached Cavite Bay in May 1805, and left for Acapulco on 21 July 1805. However, due to the changing directions of the winds, Captain Motard decided to anchor in the San Jacinto Bay, on the East Ticao Island, the last port before crossing the Pacific,63 where two British ships attacked Motard and his men. Although he was able to repel the British ships and force them

Figure 16. Bourayne’s La Canonnière fighting The Tremendous, 1806 (Château de Versailles, Galerie des Batailles) (c) RMN – Grand Palais / Stéphane Maréchalle 25

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 37

5/7/19 8:47:49 PM

to retreat to Macau, Motard’s frigate sustained too much damage and was unable to continue its journey. Since the British blocked Cavite Bay, Motard returned directly back to the Isle-de-France, passing a new route through Gilolo, Moluccas, Alor, and the Ombay-Wetar Strait. Motard’s diversionary strategy allowed a ship from the Compañía de Filipinas to arrive safely in Manila from Peru, bringing with it 500,000 piasters from Spain. In 1806, General Decaen sent to Manila the La Canonnière, a frigate in a poor state following its encounter with the British ship The Tremendous in La Réunion Island (see Figure 16). The La Canonnière, which was under the command of Captain César de Bourayne,64 arrived in Cavite in February 1807 for much-needed repairs and replenishment of supplies. However, the ship struggled due to the scarcity of food and equipment. The new Spanish Governor-General Mariano Fernandez de Folgueras, asked Bourayne to escort the galleon and Compañía de Filipinas’s ship called the Santa Gertrudis to Mexico. Since the galleon slowed down the entire contingent, Bourayne proposed to escort the galleon and the Santa Gertrudis only up to 500 miles off Cape Engano, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, where a British attack need no longer be feared. Thereafter, Bourayne proposed to proceed to Acapulco as planned to immediately seek audience with the Viceroy of Mexico,65 and return to Manila with the money. Bourayne left Manila on 20 April 1807, reached Acapulco on 15 August 1807 where he sojourned for three months while waiting for the funds, and returned to Manila with three million piasters66 on the eve of Christmas. His crew, who were then not yet paid, started a rebellion.67 The insubordination only ceased when the Governor-General was able to collect 30,000 piasters (1% of the funds brought by the French) as donation from the Manila traders. Although he was not wealthy, Bourayne gallantly refused to participate in the sharing, accepting only a saber of honor from the hands of Governor-General de Folgueras. This initial Philippine-French partnership ceased with Napoléon’s eviction of Ferdinand VII, with Governor-General de Folgueras and the Philippine clergy remaining loyal to the Bourbons. In 1808, Governor-General de Folgueras even ordered the imprisonment of Alexandre du Crest de Villeneuve 68 and his crew, releasing them only three months later upon the intervention of the French warship Entreprenant under Pierre Bouvet. French vessels stopped using Manila as its port of call until the end of the Napoleonic era. 26

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 38

5/7/19 8:47:49 PM

B.

DREAMING OF BASILAN: FRANCE IN THE SULU SEA, WITH THÉODORE DE LAGRENÉ (1844-1845) Trade between the Philippines and France resumed after the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty in 1814. France dispatched numerous merchant ships, mostly from Bordeaux, and four major scientific missions to the archipelago. The scientific expeditions occurred in 1817 under the command of Achille de Kergariou;69 in 1824 to 1826 under Hyacinthe de Bougainville70 and Paul du Camper, General Decaen’s former agent in Manila; in 1832 under Cyrille Laplace;71 and in 1836 under Auguste-Nicolas Vaillant.72 In addition, Pierre-Henri Philibert73 was sent to Manila in 1819 by the French admiralty to recruit Filipino workers for the French Guyana after the abolition of the slave trade. The Spanish Governor-General opposed the objective of the mission. However, this did not deter France from deciding to open a consulate in Manila in 1824, thereby being the first foreign country to do so. Opportunities offered by the archipelago caught the interest of some French nationals. Such was the story of Paul Proust de la Gironière,74 a surgeon in the French Navy. According to his book published in 1855, de la Gironière settled in the Philippines between 1820 and 1839. When his wife and son died, he sold his sugar plantation in Jala-Jala and returned to France where he was bestowed the Légion d’honneur. De la Gironière remarried in Nantes and had two children. However, twenty years after returning to France, he decided to go back to the Philippines. He bought a new plantation in Calauan, situated in the south of Laguna de Bay and died there three years later. Paul de la Gironière’s book75 greatly helped promote the knowledge of the Philippine archipelago in France. During the first half of the 19th century, the relations between the Philippines and France intensified beyond military cooperation. France regarded Southeast Asia as significant to the resumption of her global diplomatic ambitions. The collapse of the Napoleonic Empire depleted French coffers and reduced her foreign policy to a bare preservation of the pre-revolutionary borders. At peace with the British, Spanish, and Dutch during the reign of King Louis-Philippe between 1830 and 1848, France then decided on the costly process of subjugating Algeria. Succeeding in her engagement in Algeria, France then became prosperous enough 27

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 39

5/7/19 8:47:49 PM

to prepare for long distance colonial expansion, as shown by its blockade of Argentina ports76 in 1838 to 1840 and the establishment in 1843 of two stations in the South Pacific Ocean—in Tahiti and in the Marquesas islands. Great Britain, France’s main historical competitor and now ally, emerged victorious from the First Opium War (1838-1842). The Treaty of Nanjing sanctioned the ceding of Hongkong to Great Britain, and allowed the opening of five Chinese ports—Canton, Shanghai, Ningbo, Amoy (now Xiamen), and Fuzhou—to Western trade. In view of these recent developments, King Louis-Philippe sent his first legation to China in December 1843.77 The legation was escorted by three warships from the South China Sea division, which used Manila as its stopover port. Reinforced by a frigate and two corvettes from Brest (major military port in Brittany), the fleet was under the command of Vice Admiral Jean-Baptiste Thomas Médée Cécille.78 Heeding the advice of then Foreign Minister79 François Guizot,80, the delegation included a high-ranking diplomat, Théodore de Lagrené,81 former minister plenipotentiary to the newly independent Greece. The delegation was successful, having obtained for France the signing of the Whampoa82 commercial treaty in October 1844, and the issuance in December 1844 of an imperial edict on religious freedom aiming to protect Catholic missionaries. Jean Mallat, Advocate of Basilan Aside from his role as extraordinary plenipotentiary, Lagrené received secret instructions from Foreign Minister Guizot to scout for and establish a permanent base in the South China Sea for the French Navy. The British already controlled Lower Burma and the Malacca-Singapore Strait, and the mouth of the Sarawak river since 1842, thanks to James Brooke. The Dutch managed the Netherlands Indies while the Spaniards had been in the Philippines for centuries for as long as the Portuguese were in Macau. The establishment of French bases in the Far East proved challenging. While the islands of Natuna and Anambas 83 (northeast Batam) were free from foreign control; however, their locations are too 28

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 40

5/7/19 8:47:49 PM

Figure 17. « Habitants des Montagnes, archipel de Solou [Mountain people, Sulu archipelago, Basilan Island] », in Jean Mallat, Archipel de Solou, face p. I. The people depicted in the painting are obviously not Muslim, proof that Mallat had probably never himself been to Basilan Island. Basilan’s indigenous and mountain people were Yakan, a tribe already under process of Islamisation in the 1840s, and some northern groups of which had also already been previously Christianized by Jesuit missionaries, who remained in Basilan till the second half of the 18th century. 29

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 41

5/7/19 8:47:51 PM

near the British and Dutch colonies. Inhospitable living conditions in Pulau Condor forced the British to abandon the island after five years of settlement; and Cu Lao Cham, present-day Hội An in Vietnam, did not seem a favorable location either. To remain within the vicinity of China, the only vantage position left for France would thus have been located in the Philippine archipelago, but in a place remaining outside Spanish sovereignty: Basilan Island.84 The choice of Basilan—called the Tajima Island in old western maps— was not accidental. On 23 April 1843, during an exploratory mission to Sulu by the corvette La Favorite, the first commercial agreement was entered into between the Sultan of Sulu Jamal- ul Kiram I and France, represented by Lieutenant Commander Théogène François Page. In his report,85 Page mentioned that Basilan was more or less a no man’s land, not being controlled by the Sultan of Sulu, his extended male relatives, or the Spaniards. Westerners observed that Basilan had agricultural potential, as the island annually exported to Sulu some thirty big prahu86 of rice grown by hinterland Yakans.87

Figure 18. Text of the commercial agreement between France and the Sultanate of Sulu dated 23 April 1843 (Archives du Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires Étrangères- La Courneuve) 30

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 42

5/7/19 8:47:56 PM

Another reason for Basilan’s appeal was based on the works of Dr. Jean Mallat88 who sojourned for eight years in the Far East, including Manila, before returning to France. Mallat published two preliminary works on the Basilan Island89 and the Philippines,90 which earned him full support from the Minister of Navy Rear Admiral Baron Armand de Mackau, and connections to the highest echelons of the State.91 The problem, however, was that Mallat’s information on Basilan were contradictory, having been gathered from various sources that were neither verified on site nor properly discussed. Explaining, for instance, “an attack from the people of Basilan on the people of Zamboanga was rare, especially on Westerners,” he wrote “as a precaution, in collecting water in the (Malosa) river, it is advisable to bring weapons and not to get close to the village to avoid an attack.” Unaware of the inaccuracies of Mallat’s accounts on Basilan, de Mackau requested him to join de Lagrené’s mission as a scientific and linguistic support for the secret operations in the Sulu archipelago. Together with the commercial delegation interested in textile trade,92 Mallat boarded the L’Archimède, which reached Macau in August 1844. Mallat was designated as the “colonial agent”, provided with a comfortable salary, and was promised 200 hectares (roughly 494 acres) in the new occupied territories.93

Escalating Conflict In October 1844, Admiral Cécille sent Mallat to Basilan aboard the corvette Sabine under the command of Captain Guérin. Unfortunately, Mallat could not speak Malay94 and had to require the assistance of a certain Hermann to interpret. Hermann was a fourteen- or fifteen-year old Dutch subject95 from Batavia whom Mallat hired in Macau96 while the latter was “busy in being taught the Malay languages.”97 On 24 October 1844, the French anchored in the perilous Malosa Bay in Basilan, a place that was prone to piracy—and where the French committed the first of their many mistakes thereby exposing the limits of Mallat’s abilities. During the first two days upon arrival in Malosa Bay, the French and the local inhabitants exchanged pleasantries and presents. A meeting in an islet called “Gowenen” (Gounan, in the middle of the bay) was arranged between Rajah Usuk, an ethnic Tausug local chief, and Captain Guérin. Adverse weather 31

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 43

5/7/19 8:47:57 PM

Figure 19. Map of Basilan, extract from the map ‘Archipel des Soulou’, in J. Mallat, loc. cit., 1843, last page.

Figure 20. À S.A.R. Monseigneur le Prince de Joinville, Hommage respectueux de l’auteur, son très obéissant et fidèle serviteur J. Mallat [To H.R.H. the Prince of Joinville, respectful regards from the author, his very obedient and faithful servant…]

32

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 44

5/7/19 8:47:58 PM

Figure 21. Map of the Malosa Bay, in J. Mallat, loc. cit. last page, mentioning (box, top right) “from the map drawn in 1764 by the British captain Walter Alves”98

conditions prevented the meeting from taking place, making the French impatient. Captain Guérin, Mallat and several of their crew members attempted to enter the mouth of the river, but their main boat ran aground. Instead of turning back, they took a dinghy and asked the men in a Malay prahu manning the entrance of the river if they could meet with the Rajah. The locals responded that the Rajah was indisposed; however, if Captain Guérin himself would venture upstream, the Rajah would receive him. Declining the proposal, the Captain sent four men, including the interpreter, on the dinghy. The group, under the supervision of Sub-lieutenant de Meynard, was tasked to conduct a reconnaissance of the river and collect water samples, which were needed by the French authorities in evaluating the feasibility of establishing their base in the island. The Tausugs resented the trip, viewing it as both insulting—owing to Captain Guérin’s refusal to meet personally with the Rajah—and threatening. Two Malay boats then approached the dinghy, and a local dignitary asked for Meynard’s gun. When Meynard refused, he and a crew member99 were struck down with a kris, while the interpreter and the ship’s boy were taken hostage in the chaos that ensued.100 Unable to wait for the arrival of the corvette La Victorieuse under 33

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 45

5/7/19 8:47:59 PM

the command of Rigault de Genouilly that would enable him to negotiate from a stronger military position, Captain Guérin sailed at once to Zamboanga to seek the assistance of Zamboanga Governor Cayetano Suarez de Figueroa. The Sulu archipelago, especially Basilan, was known for its economic activities that consisted primarily of raiding and slave trade conducted by the Balangingi population of its southern shores.101 Acting as the intermediary, Governor de Figueroa was able to bring Rajah Usuk and Captain Guérin to the negotiating table. Rajah Usuk demanded from Captain Guérin 2,900 piasters as ransom money, 10 guns, a hundred razors, and other sundries. The French initially refused to capitulate to all of the Rajah’s demands. However, they eventually paid the ransom and recovered their men who were treated surprisingly well.102 Apparently, Rajah Usuk only received 25% of the sum and some rifles, as it was customary to share the ransom with the local participants.103 After a brief stop in Basilan, and without encountering any aggression due to the acumen of her captain, the La Victorieuse joined the Sabine in Zamboanga. The captains of the two ships decided to make a blockade of Basilan104—against the advice of Governor de Figueroa, who could not prevent the operation for lack of proof of Spanish sovereignty over the island. Governor de Figueroa immediately informed Manila of the French’s action, sending to Basilan a few falhoas105 from the Marina Sutil as demonstration of Spanish warship over the area. The French then notified the Sultan of Sulu of the blockade. The Sultan explained that his sovereignty over the island was but nominal. Meanwhile in Basilan, two French boats rowing upstream in the Malosa river were fired upon by a cannon located at the fort. In retaliation, the French fired their cannons, wounding a dozen men, including Rajah Usuk. Arriving in Manila at the end of December 1844 with the Cléopâtre and the steamer Archimède, Admiral Cécille and Ambassador de Lagrené found themselves in the middle of a diplomatic deadlock. Spanish Governor-General Narciso Clavería y Zaldúa explained coldly that Basilan was part of the Philippines but that the Spanish had to abandon their garrisons on the island in 1762 due to the British attack in Manila and they never returned. After Lieutenant Commander Page completed his mission in Basilan in 1843, Governor-General Clavería y Zaldúa ordered 34

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 46

5/7/19 8:47:59 PM

Zamboanga Governor de Figueroa to go to Basilan and counter French influence. Governor de Figueroa secured for Spain an informal alliance with a number of northern datus who were willing to use the Spanish flag. However, the alliance—called the “Balagtasan League” (covering Lamitan, East Isabela)—was formed without signing any formal document.106 In December 1844, although Ambassador de Lagrené and Governor-General Clavería y Zaldúa agreed to entrust to their respective governments the legal determination of the sovereignty over Basilan, Governor-General Clavería y Zaldúa asserted Spanish right by sending the frigate La Esperanza to Zamboanga. On the other hand, Admiral Cécille waited in Manila for the construction of two barges capable of transporting troops along the shallow banks of Basilan’s rivers. On 8 January 1845, Admiral Cécille and his fleet dropped anchor in Malosa Bay. A few days later, the French were able to repel two falhoas that were attempting to force their way through the blockade. The French limited the blockade to Malosa Bay when the captain of the La Esperanza protested. Friendlier than Maloso’s datus, the same Balagtasan datus that had struck an agreement with the Spanish the year before explained to Admiral Cécille on 13 January 1845 that they were loyal neither to Spain nor to the Sulu Sultanate and that they merely used the Spanish flag on their way to Zamboanga and displayed another one when they went to Sulu. The Balagtasan League was composed of Panglima “Tiran” (Tairan), his brother- in- law Arak Tao Marayo, and Imam Baran.107 This hierarchical structure was characteristic of the Samal-Balangingi raiding groups where the Panglima was the local chief (who was, most of the time, a Samal tributary of a Tausug datu), and the imam or hatib was both the chaplain and judge accompanying the raiding or commercial fleet.108 On 22 January 1845, the Balagtasan, Bulansa,109 Bagbagon,110 and Pasanban (Pasangan, today’s Isabela) chiefs finally signed a treaty with the French. When asked why they preferred the protection of the French to that of the Spaniards’, these local chiefs111 answered that with the treaty, the Spaniards would not bother them. The Spanish were already permanently established a few miles from their island, while the French presence remained minimal. Three of the French warships left for Sulu on 4 February 1845. Admiral Cécille requested the Sultan of Sulu to rent the Basilan 35

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 47

5/7/19 8:47:59 PM

island. Three days after the French arrived, the British corvette Semarang, which came from Brunei to assist James Brooke in resisting his Bruneian opponents, anchored in Sulu on the pretext of rescuing British crew who were taken into slavery.112 The Sulunese resented French presence, and went into lengths to poison, using the fruits of the manchineel tree,113 the spring where the sailors replenish their water tanks. Because of this acrimony, the French reluctantly requested the mediation of William Wyndham,114 an English trader who had settled in Sulu and conducted business in Manila, Borneo, and Singapore.115 After a heated debate within the Rumah Bichara (the Council of Dignitaries), and a lot of bargaining between the French and the Sulunese, the price was fixed at 100,000 piasters for the first year and 80,000 piasters for every succeeding year for a 100-year lease period, under an impossible condition that the agreement be approved by the French authorities within six months. A memorandum of understanding was signed on 19 February 1845. In the meantime, the French granted asylum to 23 slaves, who were mostly Tagal, Spanish and Dutch, who had swum to their ships.116

Figure 22. Mohammed Yamalul Alam, Sultan of Sulu (circa 1870s). (Photo/Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais) 36

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 48

5/7/19 8:48:01 PM

Meanwhile, the ultimatum sent to Rajah Usuk on January 26, to produce 20,000 piasters as compensation for the families of the two murdered men, to deliver their assassins to the French, to release all Filipino and Western prisoners and slaves in his captivity, and to cease piracy remained, predictably, unheeded. On February 27, declining the Spaniards’ support, the entire French fleet assembled in Malosa to punish Rajah Usuk for his “treachery.” One group that went upstream lost three men. The remaining 400 soldiers were able to cross the mangrove and swamps, destroyed the small fort, burned about 150 houses, a whole flotilla of prahu and the materials of a small shipyard 117 in the vicinity, cut banana and coconut trees, and ransacked rice granaries—thereby destroying the livelihood of Rajah Usuk’s subjects. While the French were engaged in Malosa, the Spanish frigate La Esperanza attacked Balangingi Island, then the den of Samal slave raiders, without significant success.

Much Ado about Nothing After the destruction of Malosa, Admiral Cécille dispatched the steamer L’Archimède back to Suez post-haste. He instructed Captain Edmond Pâris and diplomatic attaché Alphonse MareyMonge to travel immediately from Suez to Paris because of the six-month deadline for the approval of the French authorities on the lease of Basilan. When Foreign Minister Guizot received Ambassador de Lagrené’s report in June 1845, the military and diplomatic conditions had already changed: France was involved in South America 118 and Madagascar,119 while Emir Abd-el-Kader led a major insurgency in Algeria. Foreign Minister Guizot remained skeptical of the project, while the Minister of Navy was supportive of the same. On 30 June 1845, the French Council of Ministers gave its approval for the establishment of its base in Basilan. However, on July 26, King Louis-Philippe decided to forego with the plan as constructing and maintaining a permanent outpost in Basilan would have required a strong military and naval support in the area and especially since the monarch was then in search of a Spanish spouse for his youngest son.120 The royal decision was transmitted to Ambassador de Lagrené on 5 August 1845, and to Admiral Cécille on 12 August 1845. He was instructed to convey France’s decision to the Spanish Governor-General and to the Sultan of Sulu. 37

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 49

5/7/19 8:48:02 PM

Staking Claims When the French left Basilan at the end of February 1845, the Spaniards arrived. Concerned with the growing appeal of the Sulu archipelago to European powers, the Spaniards built a small fort called “Isabela” in Pasangan (the core of present-day Isabela City), and entered into an agreement with the Balagtasan League that had previously signed a treaty with the French. The French operation in Basilan provided the impetus for putting the island under relative control of Manila, effectively preventing further attempts of colonization by other Western countries. Governor-General Clavería y Zaldúa, who had previously failed to purchase war steamers from the British, obtained three of them in subsequent years. These steamers were used in 1848, under the Governor-General’s command, to rid the Balangingi Island of Samal pirates.121 One of the steamers was the Elcano, which later sailed to Cochinchina.

38

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 50

5/7/19 8:48:02 PM

III

THE PHILIPPINES’ FIRST PARTNERSHIP WITH FRANCE The ‘Chasseurs Tagals’ (Tagal Rangers) and the French Conquest of Cochinchina (1858-1863)

D

espite the unsuccessful French expedition to Basilan, the issue of Cochinchina sparked a renewed relationship between the Philippines and France. Since 1676, Catholic missions in Tonkin were in the hands of the Spanish Dominicans based in Manila (Provincia del Santo Rosario)122 and the French from the Missions Étrangères de Paris (MEP) working mostly in Cochinchina. Although Emperor Gia Long (r. 1802-1820) and French Bishop Pigneau de Behaine shared a close relationship, the emperor issued an edict in 1804, which treated Buddhism and Catholicism with equal suspicion and forbade both religions from building or repairing pagodas and churches. The edict was issued to secure the support of the orthodox Confucian elite to legitimize the Nguyễn Imperial Dynasty and to secure Chinese recognition. Nonetheless, it was only Catholicism that was regarded as a proper threat, owing to a more organized Catholic community.123 To prevent the European powers that had settled in Manila, Macau, and Penang from using religion as a means to extend their influence, Gia Long’s successor, Minh Mạng aka Minh Mệnh (r. 1820-1841), increased pressure on the missionaries. Minh Mạng’s first edict, issued in 1825, forbade missionaries from entering the kingdom. A second edict was issued in 1833, outlawing Catholicism and ordering the arrest of missionaries and their exile to Huế. The second edict was promulgated following Lê Văn Khôi’s insurgency in Gia Định province (Cochinchina) where some Vietnamese Catholics called the Siamese for help. The third edict, declared in 1836, ordered the execution of all missionaries arriving on board Chinese ships and all missionaries detained in Vietnamese jails.124 Among those incarcerated were four Spanish clerics, including two bishops.125 Because of these developments, The Netherlands, Britain, and France refused to receive Minh Mạng’s ambassadors in 1840. 39

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 51

5/7/19 8:48:02 PM

Under Emperor Thiệu Trị (r. 1841-1847), persecutions of missionaries decreased for a while as Western powers remained close to Annam due to their intervention in China for the First Opium War. Without fighting, French warships were able to rescue imprisoned French missionaries in 1843 and 1845 (including Théodore de Lagrené). However, in 1847, two French frigates under the command of Captains Augustin de Lapierre (54-gun frigate Gloire) and Rigault de Genouilly (24-gun corvette Victorieuse) sank five Annamite ships on the Tourane Bay (today’s Đà Nẵng) during an outbreak of hostilities resulting from the breakdown of the negotiations to release French missionaries, which again included de Lagrené. In retaliation, Emperor Tự Ðửc (r. 1847-1883) promulgated in 1848126 and 1851 edicts on the persecution of Catholics. Ten Europeans and 115 Annamite priests were executed until 1862, around 5,000 Christians were killed, and around 5,000 people who took refuge in Siam were exiled. The situation escalated when the French warship Catinat shelled Tourane in 1856; Emperor Tự Ðửc refused to receive Emperor Napoléon III’s plenipotentiary in January 1857; and Spanish Bishop José María Díaz Sanjurjo, the apostolic vicar for Tonkin, was beheaded in July 1857. In September 1857, the Catinat returned to rescue missionaries; and in November 1857, Napoléon III decided to intervene in Cochinchina by asking the Spanish Ambassador in Paris for the support of 1,500 to 2,000 men from the Philippines.127 The French Empress Eugénie de Montijo was highly concerned about the situation in Cochinchina. A devout Catholic and a member of the Spanish nobility, sister of the Duchess of Alba, and with connections in the Philippines,128 Empress Eugénie de Montijo favored French intervention in Cochinchina. The French intervention was to be headed by Rear Admiral Rigault de Genouilly. Two days before Christmas, the Spanish government ordered Governor-General Fernándo de Norzagaray y Escudero to send to Cochinchina two companies—infantry and cavalry129—and some 1,200 to 1,400 men.130 This reinforcement was significantly smaller than what the French authorities requested. As the French forces in Asia were still engaged in China, the operation had to be suspended until the signing of the Treaty of Tianjin in June 1858. However, on 28 July 1858, Emperor Tự Ðửc ordered the Spanish Bishop Melchor García Sampedro to be chopped into pieces. 40

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 52

5/7/19 8:48:02 PM

Figure 23. From the Governor--General of the Philippines, instructions given to Colonel Bernardo Ruiz de Lanzarote, Sept. 8, 1858. Reproduced in L.A. Síntes, p. 457 (España. Ministerio de Defensa. Instituto de Historia y Cultura Militar. Archivo General Militar de Madrid.)

41

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 53

5/7/19 8:48:04 PM

Figure 24. State of the forces in Saigon by Lieutenant-Colonel Carlos Palanca Gutiérrez, May 15, 1860. As reproduced in L.A. Síntes, p. 484 (España. Ministerio de Defensa. Instituto de Historia y Cultura Militar. Archivo General Militar de Madrid.)

42

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 54

5/7/19 8:48:07 PM

The Philippines dispatched more than 1,000 men to Cochinchina: the whole infantry regiment Ferdinando VII No. 3 from Manila; two companies of rangers, including some cavalry from the King’s Regiment No. 1 in Manila and the Queen’s Regiment No. 2 from Cavite; two mobile and field artillery divisions and one for logistics. Although all officers were Spanish,131 nearly all troops were Tagal. On 20 August 1858, around 400 men boarded the French ship Dordogne under the command of Colonel Mariano Oscáriz, and around 100 men embarked on the Spanish aviso Elcano. They joined the French forces in the Yulikan Bay (present-day Hainan Island) where the Tagal soldiers were struck with cholera and dysentery, diseases that the French contingent contracted from China. The remaining 550 Tagals, together with Colonel Bernardo Ruiz de Lanzarote who headed the Spanish expeditionary corps, were brought to Tourane on 15 September 1858 on board the Durance. They were joined by five Spanish merchant ships that brought food and equipment. After the bombing of Tourane’s forts, several posts were occupied by the Tagals, who rested for a while and feasted reportedly on rice field rats—shocking their French counterparts who preferred less exotic fare.132 Assessing that a siege of Huế, Annam’s capital, would be too risky, Rear Admiral de Genouilly decided to attack Saigon instead, Cochinchina’s main port. Leaving a small detachment consisting of three infantry companies in Tourane, Rear Admiral de Genouilly left for Saigon on 2 February 1859. He was accompanied by 2,176 soldiers, including the Elcano and 300 Tagals under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Carlos Palanca Gutiérrez and Colonel Ruiz de Lanzarote.133 On 19 February 1859, the joint forces took control of the citadel of Saigon, which they destroyed in a few days later as they lacked sufficient number of troops to defend it. The Tagal soldiers took advantage of the victory break to train Cochinchinese fighting cocks.134 In March 1859, half of the troops were sent back to Tourane, leaving only 555 men in Saigon, including 223 Tagal fighters under the command of Captain Fajardo. Except for the 24-day ceasefire in September 1859 resulting from the three-month negotiations in June-August, the fighting in Tourane lasted until the final evacuation in March 1860. On 27 November 1859, 127 Tagals and most of the French sailed out of Tourane on 43

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 55

5/7/19 8:48:07 PM

Figure 25. The fight at the Pagode des Clochetons (3-4 July 1860)

board the French vessel Marne and the Spanish steamer Jorge Juan. The remaining forces left their bases on 22 March 1860 after the complete destruction of the fortifications. Meanwhile, Manila had sent 50 horses for artillery and 450 Tagal fighters to Saigon135 who camped with the French soldiers in a site close to the “Camp des Lettrés”136 (Figure 25). In April 1860, the frigate Europe that was transporting the Tagal soldiers was shipwrecked near Triton Island in the Paracels. The stranded soldiers were rescued by three French boats a few days later.137 The resumption of the war in China led to French troops based in Saigon being dispatched once again to China in April 1860. Thus, only two companies, 50 Tagal cavalrymen under the command of Second Lieutenant Le Maréchal,138 around 250 French soldiers and a small navy detachment remained in Saigon. To cut the lines between Saigon and Cây Mai Pagoda,139 Rear Admiral Page—who succeeded 44

DISCOV _INT PP 050719.indd 56

5/7/19 8:48:08 PM

Figure 26."Assaut de la citadelle de Saigon par le corps expeditionnaire franco-espagnol, le 5 février 1859 [Attack of the citadel of Saigon by the Franco-Spanish task force, 5 February 1859]" from the weekly L'Illustration, 23 April 1859. Tagal soldiers are on the right side.