CONSTRUCTING OF MUMBAI’S URBAN FORESTS

THE RISKS OF GREEN GENTRIFICATION

Pooja Wagh

MLA Year 2 Studio 9

BARC0119: Landscape Thesis Thesis Supervisor: Kirti Durelle Module Coordinator: Tom Keeley

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL July 2022 (word count: 7493)

Abstract

1. Introduction 2. Green Gentrification 3. History of Mumbai and it’s slums

4. Governance Structure

4.1. Central Government

4.2. The Mumbai Action Climate Plan

4.3. Nagar Van scheme (Urban Forest Scheme)

5. Setting Dangerous Precedent For Climate Action - Cases from Mumbai.

4.1. Coastal Road Development

4.2. Industry Setup without Environmental Clearance.

4.3. Dharavi and its Mangroves 6. The Predicament of Slum Residents. 7. Conclusion

CONTEXT

ABSTRACT

The government of Mumbai recently launched the city’s Climate Action Plan (MCAP). It analyses the vulnerabilities of Mumbai and proposes strategies to achieve the action plan’s goals of reaching nee-zero by 2050. The four crucial of success outlined by the MCAP include ‘equity’- equitable access to all. It is the first time for any city from Mumbai to officially include and give importance to inclusivity in their development proposals. Mumbai – a city known for its slums and informal settlements, has always faced gentrification issues. The economic and social gap between the varied income groups of the city is widening. The stakeholders involved in Mumbai’s development are a complex relationship between the authorities, highincome business owners and developers, and middle-class or high-er class residents. The new developments have always aimed to displace slums and price out the poorer population from a neighborhood. There is a lack of detail in planning policies, making it easier for the developers to find loopholes and push out the poor. Whether this is done intentionally or intentionally is as good as a guess. This issue persists not only in Mumbai but also in the Central authority planning in India. The pattern observed throughout governance history is the exclusion of equitable rights to land and public amenities, inadequate data on planning policies, and not following through on launched policies. In times like today, where we are already feeling the effects of climate change, and as cities worldwide are getting ready to plan actions against this change, how do these gaps in planning policies affect the already inherent gentrification in the city? Gentrification brought out due to the ‘greening’ policies against climate change is termed green gentrification and is an eminent problem city worldwide is solving. This thesis aims to critique the risks of green gentrification brought about by the lack of appropriate planning in the MCAP while looking at some examples in the recent past of how authorities and developers can push out the poor. These new green policies can become a tool to gentrify the poorer settlements and widen the gap between socio-economic groups. Greening increases inequality without policies that pay attention to social justice components of sustainability, which supports the notion that environmentalists are elitist and that environmentalism is inherently unjust. This thesis aims to highlight the risks of gentrification that come with green development plans and asks to consider equitable access and inclusion as essential factors in city infrastructure and landscape development.

Introduction

Green gentrification and Mumbai

The world is facing a climate crisis. Globally, the temperature is up by 0.18 degrees per decade, 13 percent of the ice caps are melting per decade, cities and villages are flooding two times more frequently and intensely, the earth has lost one-third of its green cover, and more than 90 percent of the air is toxic, biodiversity is down to 68 percent (2022). The list of these disastrous effects goes on, and most of them are permanent damages, if not all. Various international and local organizations worldwide have been working on mitigating these problems for quite some years now. These international organizations have made it possible for countries to come together and form action plans to work towards one common goal – “a global temperature rises this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the

temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius.” (ClimateChange, 2015). According to the data from climate watch, human-caused greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) drive climate change. Just ten countries in the world together cause 60% of these GHG emissions, out of which India is ranking the third top-most country. (ClimateWatch, 2019).

In India, Mumbai is the second-largest source of GHG emissions, contributing equivalent to 105800 tonnes of emissions per day. (EnergyReviews). The Brihan Mumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) launched the city’s first Climate Action Plan (MCAP) in March 2022, setting a goal to reach a net-zero and climate-resilient Mumbai by 2050. Launching this Plan is the first big step in a very long but necessary journey for

01 Introduction

the city toward mitigating the climate crisis. The profound importance of this step makes it necessary to carefully evaluate and critique this Plan, as it will play an essential role in shaping the future of this megacity. Mumbai is home to more than a 22million people, the most densely populated city in the country, with 25,357 per sq. km. (census, 2022). However, not only this, but Mumbai is also home to more than An estimated 6.5 million people, around 55 percent of Mumbai’s population that lives in slums. Moreover, informal settlements have become an essential part of the urban fabric that makes this city what it is. With statistics like that, it is no surprise that Mumbai has seen gentrification throughout its history, right from when it was no

more than a group of seven islands with small settlements to today, when it is easily one of the most popularly known cities in the world. The urban gentrification in Mumbai is driven due to various factors, and it has kept changing as per what has been an ‘urgent matter’ for the country or the city’s needs. The latest crisis the city is facing (not only in Mumbai but the world) is the climate crisis.

Coastal and Urban Flooding and an increase in urban Heat levels are the two most urgent and intense climate risks Mumbai is facing right now. The immediate solution to these risks proposed by various governmental action plans, including the MCAP, is to increase the urban green cover

Introduction 02

Figure 2. Kids playing on train tracks due to lack of access to green and play spaces in Mumbai’s slums. (Charlton, 2022)

of the city. These plans beg the question if the ‘greening’ of the city will be the next primary driver of gentrification in the city. The concept of green gentrification is not a new one; many cities like Brooklyn, Cairo, and Mexico have faced these challenges in their development, although the characteristics of Mumbai will bring in its kind of green gentrification risks for the city. Still a relatively new term, Barcelona defines green gentrification as ‘Green gentrification refers to processes started by implementing an environmental planning agenda related to green spaces that lead to the exclusion and displacement of politically disenfranchised residents.’ (ref). As the world is dealing with one crisis after the other, more and more people realize the value of

living with access to nature. This new demand makes people want to move to a riverfront or seafront apartment, closer to a park, or even include building new parks in the neighborhood. Since now, access to greens has become a sign of luxury, driving up the land value and rent prices. This forces the low-income residents to displace as they can no longer afford the higher rates. While positive for the environment, such projects tend to increase inequality, and this undermines the need for social and environmental justice. The state government of Mumbai plays a direct role in the development of the city, but they are not the only stakeholder involved in these decisions. High-income business owners and developers play the most crucial role in all developments in

03 Introduction

Figure 3. A landscape photograph showing the difference in infrastructure of Mumbai with slums in the foreground and tall buildings in the background. (Unequal Scenes - Mumbai, 2022)

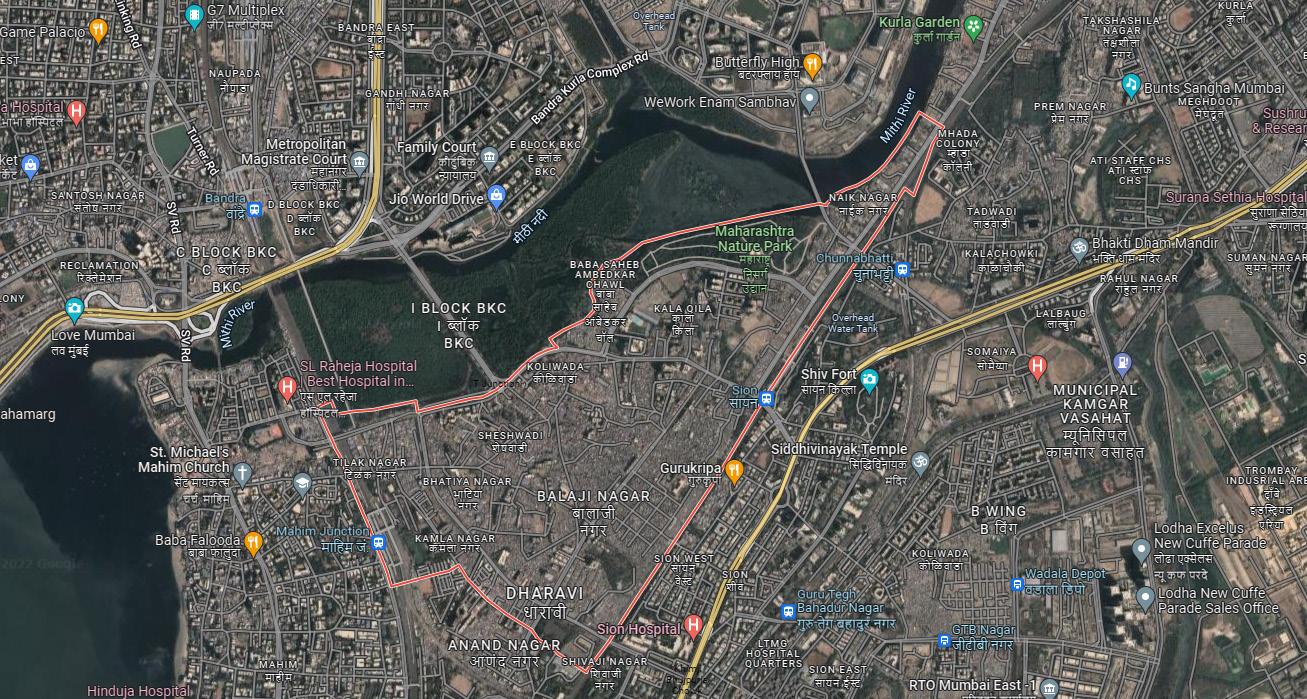

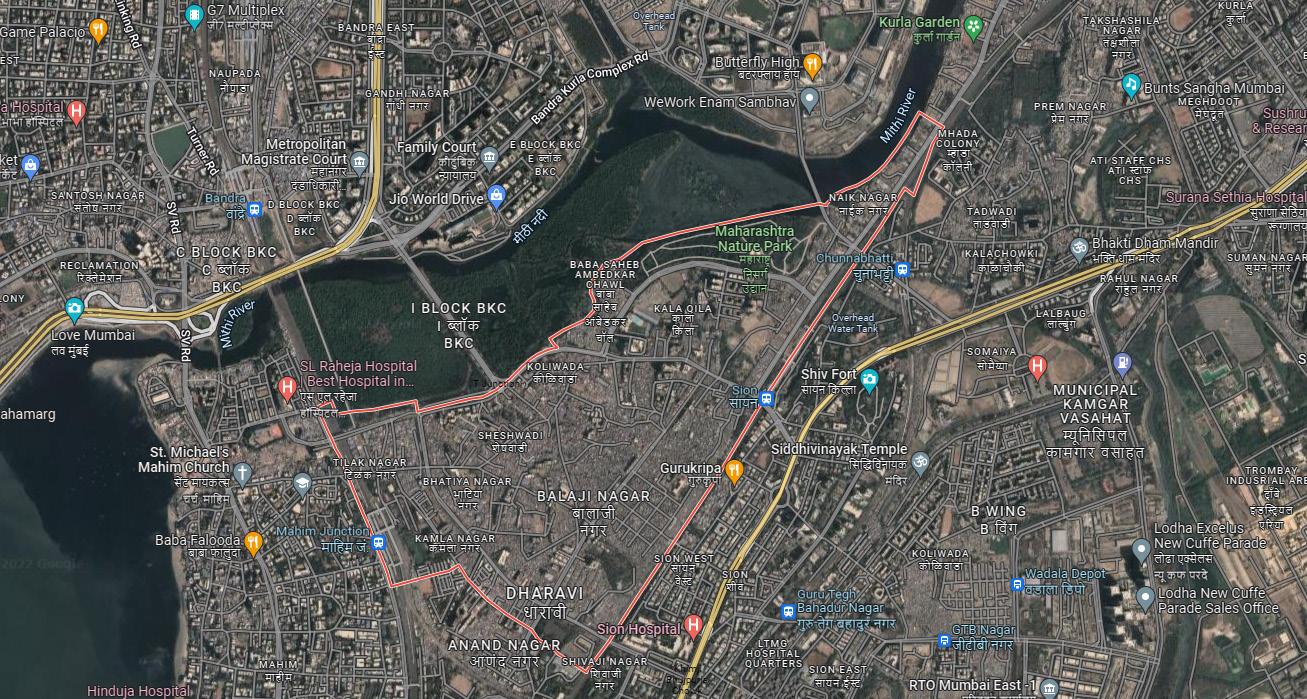

Figure 4. Google earth image showing he location of BKC along the Mithi river. The slums of Dharavi can be seen on the right of the river channel.

Mumbai. These developers have a tight hold on what projects will or will not go through in the city, and most of the time, they manage to get their way no matter how dire the consequences. One example of such is the construction of the Bandra-Kurla Complex (BKC). This complex is located on the edge of the creek that narrowed the river flow. Many city environmentalists opposed the construction of this complex, but they managed to find ways through the policies and went ahead with its completion. The devastating floods of 2005 hit the city of Mumbai brutally, killing 1000 people (Nation, 2022) and the destruction of settlements. The blame for this flood was mainly put on the land of BKC- the narrowing of the river slowed down the outlet of river water into the sea. Clearing of slums to build new developments is not a new concept for the people of Mumbai; settlements were removed for the construction of BKC, Worli slums were removed for the compound, and the latest big project of Mumbai, the coastal road development has displaced 55 communities along the coast, destroyed more than 100 trees, taken away 9.9km long seafront recreation and endangered the lives that depended on fishing. The project will be an essential driver in the redevelopment of the slums of Dharavi- a slum that has become the heart of Mumbai and fought through decades of displacement threats. Sustainable Development is essential today. Protecting natural resources, rejuvenating urban

Introduction 04

natural pockets, increasing green cover locally, nationally, and internationally is essential if the planet must survive this increase in global warming. However, it is equally vital that this is done through the lens of social justice. While climate improvement strategies are good for the environment, they simultaneously push out the low-income resident population and the urban poor. The primary beneficiary of improvement is frequently the higher income group. This increases the already widening social gap between the rich and the marginalized regarding access to nature. This thesis argues that if significant attention is given to the gentrification risks that come with planning the climate action policies, the risks could be significantly lowered, and the city and ensure an environmentally and sustainable just development. As this and this say in the book Green Gentrification, early public policy interventions aimed at neighborhood stabilization can create more just sustainability outcomes (Gould and Lewis, n.d.). Whenv

designed for inclusion, climate actions can help solve many other issues in addition to climate emergencies, such as increasing socioeconomic benefits, improving health conditions, bridging social gaps, and strengthening governing institutions.

To further build my argument in this thesis, I use critiquing the government plans and methods that operate in the city and elaborate on examples of projects already underway that have triggered the displacement of slums. I start by showing the history of Mumbai and its ‘slums’ to understand better how they were formed and what role they play in the city and digging indepth to try and define green gentrification for the city of Mumbai. This thesis is not trying to provide solutions for green gentrification risks in Mumbai; it is an attempt to present another reality of our cities, the one that we must comprehend before we propose solutions. Without such an understanding, even the most well-intentioned efforts prove unworkable.

05 Introduction

Introduction 06

Figure 5. A Dharavi Portrait. (Ambwani, 2022)

Green Gentrification

The term ‘gentrification’ was coined by Ruth Glass, an English Marxist sociologist in the 1960s. (Rodgers, 1964). However, the term only became famous in 1990 when Neil Smith published his research in the field of critical geography in 1960/the 70s. (Velázquez, 2017). They defined gentrification as “a process of neighborhood changes through which the demographic, real estate and business characteristics of a place reveal a transition towards a more educated, wealthy, whiter population, able to afford new or renovated pricier properties while also fomenting new cultural and consumption practices .”(Cole, Triguero-Mas, Connolly, and Anguelovski, 2022) Green gentrification is relatively a new term that has gained light in the recent past. It can be understood as a gentrification process that occurs primarily because of ‘greening of a city’ programs

for climate and environmental restoration. In an article written by Maria Hart, Jillian Du, and Caroline Coccoli in the WRI Blog, they define green gentrification as “when investments in sustainable infrastructure and initiatives in a city push out and price out lower-income residentsThese kinds of unintended consequences are called “green gentrification.” Unaddressed, these barriers can limit climate action and policies from reaching their full potential.” (Maria Hart, 2019)

Green, climate, and environmental gentrification are all terms that specifically talk about the social injustice and displacement of the poor that occurs because of activities or developments carried out by a state for the greening of the city, climate change mitigation, and environmental disaster mitigation respectively. These may often overlap,

07 Green Gentrification

but the intended or unintended consequences that come with such plans remain the same. Due to the increasing seriousness of climate crisis in every individual and changed lifestyles due to the ongoing covid19 pandemic, the desire to live within nature has increased. The desire to have easy access to natural surroundings, to have a park at a stone’s throw distance, to be able to bring nature inside is increased, and in such scenarios, the greening of a neighborhood makes the neighborhood more desirable to everyone and prepares them for gentrification. This drives up the prices of development, and those with resources benefit from this having more accessible access to such planned greens pushing out the existing lower-income groups. (Gould and Lewis, n.d.)

In her analysis of green gentrification, Aparna Nathan says that green gentrification “will not only exacerbate inequality in cities already plagued by housing shortages and socioeconomic inequity but also puts vulnerable populations right in the path of impending natural disasters.” (Nathan, 2019). As weather resilient neighborhoods come up, the home prices will increase, and it will be easier for those with more resources to adapt, leaving the urban poor to deal with climate change’s worst effects. She also

emphasizes that scientific studies are essential to improve our natural disaster response, but there is also important work that must be done to understand the social impact of our responses. It is important to study “how weather can work synergistically with other socioeconomic forces. (Nathan, 2019).”

To avoid green gentrification, Austin Allen, the principal landscape architect in DesignJones, LLC in New Orleans, said it is key to “understand the history of each place. The design has to be grounded, and history is compelling.” He also insists on community participation and involving everyone to ‘envision a future together. By involving the community groups in planning activities, they happily accept the developments and work with you to make the improvements happen. We, as architects and landscape architects working on neighborhood and natural regeneration projects, can emphasize involving the neighboring communities in the planning process. Their years of knowledge of the land can be of immense help in designing for context. In contrast, dialogue between everyone can help them articulate their issues, provide equitable solutions, and promote connections within the community. (Phillips, Smith, Brooking and Duer, 2021)

Green Gentrification 08

History of Mumbai and it’s Slums

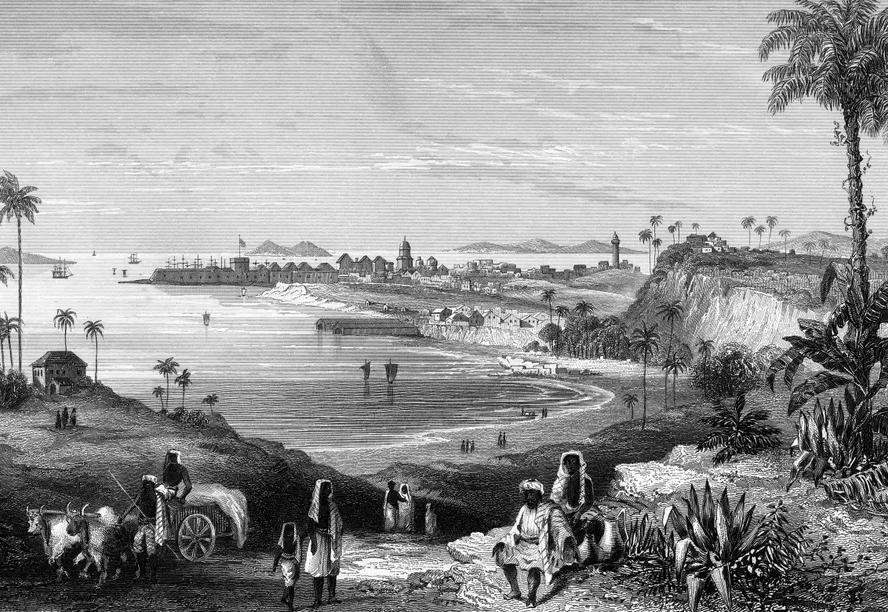

Three hundred years ago, the megacity of Mumbai was nothing but a group of seven islands. In 1670 the British took over the islands, saw an opportunity for a port for trade business access into India, and decided to make a port city. At every high tide, the water would rise to the lower parts of the islands. The landscape of Bombay has changed since then, the seven islands made of hills, marshy lands, and mangroves were dug up a flattened, and soil from hills was used to reclaim the marshes and form this island. Reclamation has been a big part of Mumbai’s history and is also a big part of its future. The city’s population is over 22 million, and the density is 25,357 people per sq. km. (census, 2022). Being the most densely populated city in India and the 3rd highest in the world, reclamation still goes on every day for new infrastructure needs. Flooding

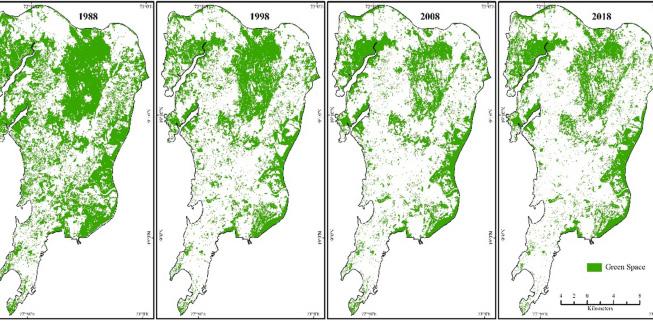

risks- the most vulnerable climate risk rises with every piece of land reclaimed and a combination of the cutting down of mangroves that protect the city from floods with narrowing the river and water channels, Mumbai is looking at irreversible damage to its landscape. The city’s second most vulnerable problem is its increasing urban heat levels. They have gone up significantly only in the last decade. As the urban infrastructure increases and the city’s green cover decreases, the urban heat traps have increased, warming up the city.

Although the most urgent, these are not the only problems Mumbai faces. The city has been home to various groups of slums since its inception. Dharavi is today at the heart of Mumbai, one of the world’s largest slums (though not THE LARGEST as commonly misunderstood). The

09 History of Mumbai and it’s Slums

word “slum” was first used in London at the beginning of the 19th century to describe a “room of low repute” or “low, unfrequented parts of the town” but has since undergone many iterations in meaning and application. (UNHABITAT, 2003a). In India, “The word “slum” is used to describe informal settlements within cities with inadequate housing and miserable living conditions. They are often overcrowded, with many people crammed into small living spaces. Slums are not a new phenomenon as they have been a part of almost all cities, particularly

during urbanization and industrialization.” (hand rise, 2022). Today there are over 50 slums in Mumbai, without about a total of 30000 people living in them. These slums are often an incredible example of community living. It is common in India to find settlements divided based on religions and castes; Several historical events have led to these divisions. But the people of slums have a common enemy that they fighttheir economic State and, ironically, that brings them together where they strive by helping each other in the most precarious conditions. While

History of Mumbai and it’s Slums

History of Mumbai and it’s Slums

10

Figure 6. An areial shot of the slums of Dharavi. (Unequal Scenes - Mumbai, 2022)

Figure 7. An illustrated map of Mumbai showing the current city on Background and overlayed with the size of original seven islands of Mumbai.(Sumedh, 2022)

11 History of Mumbai and it’s Slums

History of Mumbai and it’s Slums 12

Figure 9. The Hornby Vellard, completed in 1784, is said to have given shape to the modern city of Mumbai. (theGuardian, 2022)

Figure 8. Bombay’s famous fort, circa 1850: by this time, the seven islets had been connected to form a contiguous city. (theGuardian, 2022)

this is one side of the story, Mumbai is also home so some of the wealthiest families in India. A clear socioeconomic gap persists in the city, and multiple agencies are responsible for widening this gap. This had resulted in gentrification issues even when Mumbai was just Bombay.

To take an example of this, let’s discuss the history of Dharavi. Today, the location of Dharavi has become one of the most popular and indemand parcels of land. Close to Bandra, the new BKC complex, easy access to the future coastal road development, and views of the sea, developers are fighting over how to take over this land for new developments. No one is against development, but the problem is with how these developments take place, and there is less to no consideration of the low-income groups during the process and in the product of these schemes. A slum is not a chaotic collection of misplaced structures; it’s a dynamic collection of a diverse group of people who have figured out how to survive in the most adverse circumstances. There is so much more to learn from a group of communities like that than there is to hate this type of settlement. At the same time, as tempting as it is to romanticize the slums, we cannot forget that there is nothing to celebrate about

living in a cramped space without natural light or ventilation, clean running water, and poor sanitation. No one should have to live in such conditions. But we must carefully understand the history, growth, and needs of the community and all aspects of its reality before we find solutions. Without such an inclusive understanding, even the most well-intentioned efforts prove unworkable.

There are three major stakeholders in this scenario, the governmental bodies which have a direct hand in the forced displacement of these slums, the developers and their highincome investors who have very high power in influencing even the governments and their decisions, and third the middle-income groups who collude with the development proposals in hopes of having the same income or slumfree neighborhood. The government has in place the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme tailormade for Mumbai. But there are loopholes and conveniently left out details of policies that make it possible for the rich builders and governments to displace these residents to another location under the ‘SRA scheme’ with promises of shelter instead of including them with the plans and ensuring a just development. The wealthy citizens

13 History of

Mumbai and it’s Slums

Figure 10. Google earth image showing the spread of Mumbai slums. (Mumbai slum segmentation, 2022)

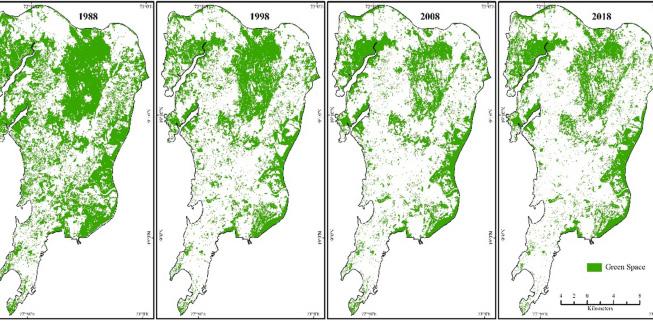

Figure 11. A series of map showing the difference in green cover in Mumbai from 1998 to 2018. . (Sumedh, 2022)

Figure 12. A series of map showing the difference in urban heat from 1991 to 2018. (Sumedh, 2022)

History of Mumbai and it’s Slums 14

Ward & Village wise Slum Cluster Map of Greater Mumbai Showing area Boundaries of Competent Authority- GPS Survey 2015-16

Figure 13. An official document- map showing the official demarcation of slum occupied land in Mumbai. (WRI India, 2022)

15 History of Mumbai and it’s Slums COLABA MALAD-II BORIVAL -II BHANDUP CHEMBUR-I MALAD-II MULUND BANDRA-I BORIVALIMALADBANDRA-I ANDHER -I GHATKOPAR CHEMBUR- I DHARAVI ANDHERI- I BOR VAL -I MALAD-I KURLA-I KURLA-I BORIVALIANDHERIMALAD GORA V KHROL TULS MALVAN MAHUL MAGATHANE DAH SAR AAREY FORT AN K PO SAR EKSAR KANJUR-E DEONAR MULUND-E CHEMBUR MAH M MANOR SALT PAN NAHUR JUHU PASPOL GUNDHGAON AKURL COLABA SAA KAND VAL TURBHE KLERABAD K ROL MULUND-W LOWER PAREL MAROL -S DHARAV ERANGAL PAHAD GOREGAON VERSOVA BOR VAL OS S ON SAHAR G O BYCULA MANDALE V LE PARLE MAZAGAON KANJUR-W MAJAS BORLA KOLEKALYAN MOH L U G AMB VAL MALABAR H LL KURLA - 2 ANDHER V LE PARLE WORL CHARKOP KOLEKALYAN MANOR VALNA BANDRA-EAST POWA BHANDUP-W TARDEO MOGRA MADH BHANDUP-E MANKHURD KURLA - 3 MARAVAL EKSAR GOREGAON MAROL MAROSH KOLEKALYAN MALAD G RGAUM DARAVAL HAR YAL -E SAK VADHAVALI TUNGWE CHAND VAL DADAR-NA GAON KANHER PRAJAPUR GHATKOPAR K ROL MALAD MULGAON BHULESHWAR BANDRA-F MANDV BANDRA-C PAR GH KAR AAREY CHAKALA BANDRA-B GUNDAVAL MARVE KURAR BANDRA-E BANDRAVYARAVLI BANDRA-G BAND VAL D NDOSH ASLAPE JUHU KOPR SMAL A WADHWAN D NDOSH MALAD SH MPAWAL KURLA - 1 HAR YAL -W T RANDAZ KURLA - 4 PR NCESS DOCK AAKSE KOND VATE BANDRA-A MAROL DADAR-NA GAON BANDRA-H BANDRA-D CH NCHAVAL V KHROL ANDHER MANDPESHWAR-M KOND VATE MALAD D NDOSH BAPNALA PAHAD EKSAR BAND VAL CH NCHAVAL PAHAD GOREGAON MAJAS WADHWAN CH NCHAVAL BRAMHANWADA MOGRA BAND VAL BRAMHANWADA PAHAD GOREGAON MANDPESHWAR-N MANDPESHWAR-S T S N P N R/C L P S M/E A K/E K/W R S E D H/E M/W R/N F N F/S G S G/N H/W B C

µ 1:40,000 Scale : 0 2 5 5 7 5 10 1 25 Kilometers

WARD

VILLAGE/DIVISION

( 1 ( 2 ( 3 ( 4 ( 5 ( 6 ( 7 ( 8 ( 9 ( 10 ( 11 ( 12 ( 13 ( 14 ( 15 ( 16 ( 17 ( 18 ( 1 ( 2 ( 3 ( 4 ( 5 ( 6 ( 7 ( 8 ( 9 ( 10 ( 11 ( 8 ( 11 ( 5 ( 12 ( 13 ( 14 ( 15 ( 16 ( 17 ( 18

Legend

BOUNDARY

BOUNDARY SLUM CLUSTER Competent Authority COLABA DHARAVI BANDRA-I BANDRA-II ANDHERI-I ANDHERI-II MALAD-I MALAD-II MALAD-III BORIVALI-I BORIVALI-II MULUND BHANDUP GHATKOPAR KURLA-I KURLA-II CHEMBUR-I CHEMBUR-II

have an image of wanting to live around only their status people, and thus they do not oppose the various schemes that builders and government agents come up with. To make this possible, environmental reasons are conveniently used to remove these settlements and clear the land. Increase in pollution, increase in insanitation, and to fight these problems the proposal of parks and trees that will include with the new complex development the kind of fake promises given to make these projects ‘sustainable’ so that it passes through the approval boards. With the new Climate action plan and a sense of urgency of planting more greens, it will become easier to propose these fake intentions of greening the city, which will soon become a green gentrifying force in the city.

For a city like Mumbai, there is no available space left. Instead there was none, to begin with. Mumbai was reclaimed part by part as demands kept increasing. Even today, vast stretches of land are being reclaimed for various infrastructure projects, the latest being the coastal road development. In such scenarios, developers turn to land occupied by slums for their projects; as Mumbai keeps growing economically, the need for commercial and recreational spaces is increasing. Also, migrating to Mumbai in search of a better life has been a continued hope for many rural citizens of India. This migration continues at a tremendous rate even today. The housing needs to occupy so many individuals keep increasing, giving the developers more opportunity for housing projects.

History of Mumbai and it’s Slums 16

Figure 14. A day in Dharavi photograph. (Ambwani, 2022)

Governance Structure

An appropriate governing structure is vital in maintaining social equity and ensuring social justice is provided in all new proposals that come from the government. If the correct public policy planning considers all economic groups, environmental justice can be achieved. While planning for urban greening policies, the planning authority must consider the social consequences from environmental justice and sustainable development point of view. Cities and mayors are leading the way in responding to the global ecological crisis, especially in addressing threats stemming from climate change. While greening initiatives improve the environmental quality of neighborhoods, they do not do so equitably.

In her paper on Nature and Urban citizenship, the senior researcher Marie-HélèneZérah argues that the Right to equitable access to nature in the urban context is embedded in the larger question of the Right to the City. She argues that different processes are undertaken for urban growth either lead to the growth or shrinking of a forested area, which is associated with a differentiation of the Right to a City rather than a general claim on space. (Zérah and Landy, 2022). The immigrants from other states looking for a better life and those that belong in Mumbai for years but have been living in slums for decades are not seen as citizens who have an equal right to public amenities by the government.

17 Governance Structure

Central Government

The central government of India shows a constant lack of detail in planning and in the policies that are presented to the country and the world. The lack of inclusion about environmental justice at a mid level leaves door open for irregular planning and risks of state government or local developers to make decisions based on their requirements. These are almost always economically motivated; providing affordable housing to the poor or consciously considering gentrification risks is never going to come from a developer’s Plan unless it is involved as a mandatory policy from the authorities. This is further motivated by the high-income groups of residents who do not want lower-income families living in the same neighborhood. Making new riverfront developments, green spaces, and public parks will always benefit the rich unless policy level changes are brought to by the respective authorities.

National Action Plan for Climate Change (NAPCC)

is a Government of India program launched in 2008- the first ever after the formation of The Prime Minister’s council of Climate Change (PMCCC) was formed in 2007 by Manmohan Singh, the then Prime Minister. It was then reconstituted by Narendra Modi (Current PM) in 2014 when he became the PM, and the first meeting was held in Jan 2015.

01, 2021 (one stage improved as compared to previous ‘highly insufficient). The tracker also comments that these goals lack detailed update and is not a good plan for climate action for the country. It says- “The updated 2030 target is comprised of four elements, but few details were given, making our assessment difficult and uncertain. It is unclear whether any elements are conditional on international support.” (India - Target update - 01/11/2021, 2022)

According to a report written by Reporter Akshit Sangomla published by DownToEarth, a magazine that focuses on India’s politics of environment and development. PM Modi’s climate change council has not met in almost seven years. The council has not met, at least not

This year at the World Leaders Summit at COP26 in Glasgow, The Indian PMO (Prime Minister’s Office) announced updated targets for the country. The goal of achieving the net-zero target is postponed to 2070 rather than as previously announced in 2030. The PMO announced these online, only a few details were given by the PMO as to how these targets were going to be achieved and what actions were being taken, leaving the country in doubt. ‘The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) that tracks government climate action and measures it against the globally agreed Paris Agreement aims given an overall rating of ‘insufficient’ to India’s actions- as of November according to the publicly available information. In the first and only council meeting, The PM called for a paradigm shift in global attitudes from ‘carbon credit’ to ‘green credit’ – but did not explain what he meant by green credit. All these instances beg the question of the lack of seriousness and expertise involved in planning some of the significant decisions that will drive the country’s development for the next 50 years. (Akshit, 2022)

The NDC (Nationally determined contributions), which is the most critical part of the Paris Agreement, highlights national plans for climate-related targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions; India has promised “to create an additional carbon sink of 2.5 billion to 3 billion

Governance Structure 18

tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent through forest and tree cover by the year 2030.” (Sinha, 2022), This promise was also made by the PMO at COP26 in Glasgow. Nowhere does the Forest department have an analysis of how they came to these figures of forest cover planning, nor is there any data available to indicate the sites of these forest plantations. Hastily making decisions right before appearing for a World Conference is a pattern the central government has shown for years. The lack of information and mandatory considerations leave these policies open to interpretation and can be used to paint a project ‘green’ while increasing the country’s environmental and social justice risks. Mumbai is one of the country’s most important cities, and the decisions made at a central level affect the city immensely. Smaller cities and towns look to the country’s metro cities for the application of all implemented policies.

The Plan’s origin in 2007 was also claimed to be a hasty formation, formed right before the ‘group of eight countries summit in July 2008. It was criticized for being only a theoretical approach and no implementable strategy. The question of detailed and correct work arises because of

the rapid formation of policies. The inclusion of appropriate experts and their expertise is also minimal. Urban planners, architects and landscape architects, researchers, environmental experts, and such should all be included in the planning authorities groups to ensure all climate and urban policies are environmentally and socially inclusive. Instead, the government is popular with promoting their political party representatives with no experience of the subjects at the table to maintain their power structure.

In November 2020, the PM announced a new Apex Committee to work on implementing the Paris agreement with similar objectives as the PMCCC, again coordinating in time with the COP26 Summit, which looks like another hasty decision to only show policies for meetings. The lack of publicly available info on the work or meetings is constant. Every Summit or conference brings in new committee formations and schemes, but no data on what the committee has worked on is available. The information always ends the formation of such groups and does not proceed to implement the strategies.

19 Governance Structure

The Mumbai Action Climate Plan

The BMC and Maharashtra government announced the city’s first-ever climate action plan, MCAP, on March 24, 2022. Its primary goals are to eliminate carbon emissions by 2050 and limit global warming to 1.5 degrees in line with the Paris Agreement goals. (Maharashtra, 2022) Mumbai’s first-ever climate action plan was the only city from India present at the COP26 conference in Glasgow. The Plan outlines its vision of a net-zero climate-resilient Mumbai by 2050 and states the four pillars of the success plan- Economy, engagement, environment, and equity. The Plan recognizes five critical areas of Climate vulnerabilities for the city – Urban Heat, Urban Flooding, landslides, coastal risks, and Air pollution. It then outlines six strategic areas to meet its goals – Sustainable waste management, Urban greening & biodiversity, Urban flooding & water resource management, Energy & buildings,

Air Quality, and Sustainable mobility. This is the first time ‘equity’ is considered at an equal level of importance in climate change policies in the country. The MCAP team is closely associated with the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (C40 Cities, 2022) and World Resources Institute (WRI INDIA, 2022) to create a comprehensive plan for a climate-resilient future for Mumbai.

The C40 cities climate action planning gives particular importance to inclusive climate action planning as an essential effort for climate action, hence the inclusion of the equity pillar in the planning of MCAP. The report says that “Climate change is inextricably linked to the challenges of eradicating poverty and creating an equal world.” (C40 Climate Action Planning Resource Centre, 2022) The report goes on to propose three goals to be ensured for inclusivity. At the same time, the planning process includes a wide range of communities and stakeholders in the process

Figure 15. Snapshots from MCAP showing the 4 pillars of MCAP’s vision (above) and the 6 strategies by which the MACP aims to meet its goals. (MCAP, 2022)

Governance Structure 20

21 Governance Structure

Figure 16. Ecological Landscape of Mumbai as shown in the MCAP. (MCAP, 2022)

of planning, inclusion in a fair and accessible design and delivery of the policy, and the impact and benefits that come from these actions. (C40 Climate Action Planning Resource Centre, 2022). C40 and WRI, in their capacity, also provide a set of resources that paves a roadmap for cities to access the equity in their climate action planning process. (Levin, Boehm, and Carter, 2022) Unfortunately, the Plan only mentions that equitable access should be considered while implementing the greening strategies. In the Urban greening and biodiversity section of MCAPa detailed analysis of existing data, the needs of biodiversity, temperature analysis, native

Nagar Van scheme (Urban Forest Scheme)

The central government has announced the implementation of the Nagar Van Scheme on the occasion of World Environment Day (June 05, 2020). (Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change,2020). The aims outlined in this Plan are - to develop 200 Urban Forests across the country in the next five years. These urban forests will primarily be on the existing forest land in the city or any other vacant land offered by local urban local bodies. While talking about this, Prakash Javadekar, the then Minister of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (20192021), talked about how gardens in cities will not be considered urban forests, and according to this scheme, new forests will be planted and designated as ‘urban forests’ functioning as ‘urban lungs.

The problem with this scheme was that Mumbai had no vacant land to offer for large, targeted forest plantations, and the only land that could be given by the local bodies if demanded was the land upon which slum settlements encroach. These options can also be ‘legally’ accepted as the ownership of land is still with the government

species, Priority actions, stakeholders involved, and different bodies of government involved is given. This lack of inclusion at the policy level puts the urban poor at risk, and the probability of green gentrification increases. This has also left the interpretation of rights of slum residents to the groups who will further implement these urban greening strategies. From past examples of Mumbai, it is not a stretch to predict that the slum residents will only be deemed a nuisance and displaced to another neighborhood instead of designing an equitable greening plan. Further detailed analysis of such past examples is elaborated in the thesis. while the support of developers and high-income neighborhoods is with them to ‘clean up slums. If approached in this manner, the slums will be removed without giving them proper alternate housing and access rights to these new green forests. That is a predictable outcome. But another primary issue that persists with this is that the Minister who launched this scheme is no more a part of the Ministry, and since his step down, there has been no follow-up on the plans of planting urban forests. In the context of Mumbai, as the government in charge is the opposition party of the central government, no importance will be given to these central schemes, and if forced upon, the state government will establish a local team to re-plan.

This political game is a constant pattern in India and Mumbai’s governance. The disregard for the opposition party’s proposals or the previous government’s proposal is so high that every time the new Minister in charge tries to reinvent the wheel. This results in nothing but wastage of time and resources in only planning various policies and establishing teams but leaves no time and money to implement these.

Governance Structure 22

Cases from Mumbai

1. Coastal Road Development

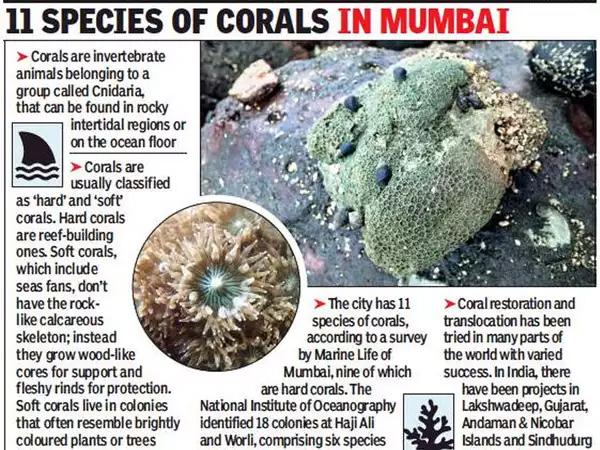

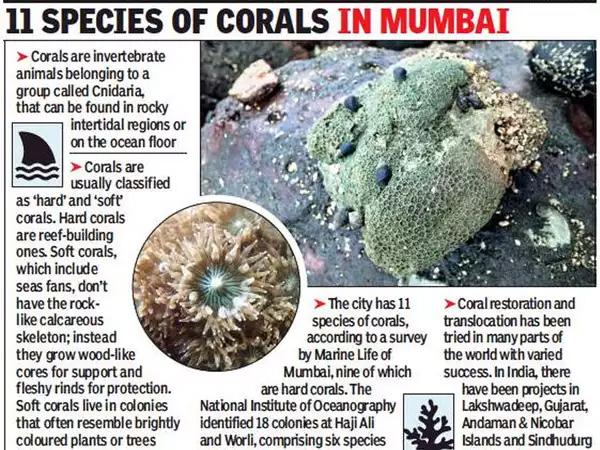

The Mumbai coastal road project is a 9.98km freeway road connecting Marine Drive -in the south of Greater Mumbai to Bandra in the north of Greater Mumbai. As the name suggests, this is being built along the coast on a combination of newly reclaimed land, bridges, and underwater tunnels. The planning and implementation of this project were one of the most controversial processes in the city. Serious environmental concerns were raised about this project right from the inception of its idea. The project planning fails to recognize the eco-sensitive nature of this coast; more than 90 coral colonies had their habitat along this coast- these were removed and transplanted, out of which 15 percent of

colonies did not survive the new habitat. Several environmental experts have claimed that there were more coral colonies than the government has disclosed through the surveys while trying to paint a picture of sustainable construction and planning. (Sushmita Panda, 2022). Experts have identified significant coastal sediment deposit structure risks due to this development and an increase in significant flood risks. The government’s Plan to make provision for flood control structures along this freeway comes as a substantial additional cost to a problem that was created. More than 600 trees have been cut all along this stretch, some permanently removed and some to be relocated. Removal of these ageold trees weakens the ground structure, and it’s absolute to hold flood water and sequester

23 Cases from Mumbai

Setting Dangerous Precedent For Climate Action

Cases from Mumbai 24

Figure 17. A snapshot from the video launched by the Mumbai government for the proposal of Coastal road Development. The visuals tell a story of the green and sustainable design of the freeway. (dept, 2022)

carbon furthering climate risks.

The list of Environmental risks goes on, but this project also comes with social risks. This coast was home to several informal settlements, some as old as when the city was Bombay. “Over 55 slums on Mumbai’s coastline are set to undergo redevelopment under the joint venture of Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) and Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA), in one of the biggest redevelopment drives in the city.” (Deshpande, 2022). These slums were the fishing communities of Mumbai, living, and fishing there for decades. This development has taken away their land and their livelihood. While promises of appropriate rehabilitation were made, there were no guarantees given to them for the possibility of being able to resume their fishing occupation leaving the communities with an unsure future. Reports have also claimed that the MHADA authority responsible for this rehabilitation is out of funds to provide adequate alternatives. “MHADA has run out of money. As a minister, it

is my responsibility to ensure MHADA becomes financially strong and the government gets revenue at a time when finances are hit due to the pandemic” (Deshpande, 2022).

Since the inception of its idea, the project has been promoted to be a ‘sustainable’ and ‘green’ urban development. Huge hoardings of visual graphics showing large patches of green gardens were the promotional images pasted all around the city. While its launch, the Speaker said, “The plan instead looks at prioritizing walking, cycling, adding green cover and restoring wetlands and use of natural landscaping among other measures - instead of concrete embankments to address chronic flooding” (Foundation, 2022). This project is a significant example of how a lack of equitable policy planning can change the demographic of an area. This project’s coastal stretch included several sea-facing promenadesfamous in Mumbai for their inclusivity. After a long day of work, every resident would come here with their families, and you could see beautiful chaos of people from all backgrounds co-existing

together and looking at the sunset over the horizon. Sea promenades are an important cultural identity of Mumbai and a virtual inclusive public space. This project is proof of green gentrification already taking place in Mumbai.

The issues do not stop here; special considerations were made by easing CRZ (coastal regulation zone) norms to make this project happen. The regulations set especially for environmental and social problems as such were waived; this brings out the question of the importance of these policies in the first place and proves that the lack of appropriate policy regulation leaves out loopholes to bend the rules.

25 Cases from Mumbai

Cases from Mumbai 26

Figure 19. Images from the construction of The Coastal Road. (dept, 2022)

Figure 18. Snapshots (aerial view top and Map bottom) from the video launched by the Mumbai government for the proposal of Coastal road Development. The visuals tell a story of the green and sustainable design of the freeway. (dept, 2022)

27 Cases from Mumbai

Figure 20. Figure 17. A snapshot from the video launched by the Mumbai government for the proposal of Coastal road Development. The visuals tell a story of the green and sustainable design of the freeway. (dept, 2022)

Cases from Mumbai 28

Figure 22. Imgaes from the protest by fishermen community of the Worli slum showing their oppose to the project. (Mumbai’s Koli folk decry coastal road project | SabrangIndia, 2022)

Figure 21. News excerpts about the environemntal harm caused to coral habitat in the coastal road development project. (News and News, 2022)

2. Industry Setup without Environmental Clearance

In March 2022, the court granted an environmental clearance with an acceptable monetary compensation after the industry is operational in exceptional circumstances. The industry Pahwa Plastics Pvt Ltd of chemical manufacturing was set up and started operations without environmental clearances on the land. The land was later deemed not environmentally fit for usage, but as the operations had already begun, the court granted permission to run operations for a fee. This sets a bad precedent for the commencement of a project without obtaining the necessary clearanceenvironmental or otherwise. “The concept of “ex post facto clearance” provides a way for project proponents to implement projects without obtaining prior clearance, and then apply for retrospective clearance.” (Lopes, 2022). Such precedents are not very uncommon in the city. Business owners who have the financial reach have known to bend the rules according to their needs. This increases the risks for low-income group citizens and of protecting their Right to their land. For future green developments that will be brought into the city, how can equitable access to nature be ensured in this ever-widening economic gap?

3. Dharavi and its Mangroves

The slums of Dharavi existed long before the reclamation of the seven islands. The community first residing as fishermen and potters in the south were pushed to the north- edge of the city by the British while they were developing the city to become their Port and Economic hub. The community settled in the place and grew where it is Dharavi, with over 1 million residents today. One of the world’s largest slums, Dharavi today, is at the heart of Mumbai, as the city grew around it. More than half of small-scale industries come from here and are an essential part of the city’s existence. The low prices compared to the city drives more immigrants to Dharavi. Over the past decade, a lot of significant developments have come around this area, and what once was the edge of the city, this part of town is now the new place to be. The land values are increasing, developers are racing to acquire new land, and the new commercial capital BKC has doubled the demand for this zone. Dharavi is one of the slums

always under the radar of redevelopment risks. Various experts have studied the gentrification risks of this scale. (Quint, 2022) Once again, the risks have increased as the surrounding neighbors have gained more demand. These combined factors put Dharavi at a high risk of being displaced for business/ luxury housing projects – supported by the government’s lack of planning regulation.

The new risk that Dharavi is under is that of green gentrification – the Mangroves that surround this settlement have been now taken over by the forest department and the Mangrove protection Cell and have been termed as a protected area. (Express, 2022) While this is a positive decision welcomed from an environmental perspective, the risks of using environmental protection to displace Dharavi are at an all-time high.

The mangrove cell is a new body set up by the state government to plan and execute innovative programs for conserving coastal and marine biodiversity. The Mangrove Cell was created by the Government of Maharashtra on January 05, 2012,

29 Cases from Mumbai

Cases from Mumbai 30

Figure 23. Google earth view showing the location and spread of Dharavi slums along the Mithi river and the Dharavi Mangroves. (Zoomed out image:above, Zoomed in image: below) (Overview – Google Earth, 2022)

31 Cases from Mumbai

to protect, conserve and manage the mangroves of the State. While the creation of the Mangrove Cell is an important step in the conservation and management of mangroves in the State, the cell carries out accidental destructions of illegal structures without an appropriate alternate accommodation. “1,296 illegal structures were removed from a 7.6- hectare reserved mangrove forest area. The idea is to protect the city’s coastline, ecosystem.” (Hindustan Times, 2022) These destructions were not carried out ethicallyno notices were given to the residents, and no SRA housing provisions were offered. “More than 5,000 people are homeless because of this destruction.” (Hindustan Times, 2022) There are plans for similar kinds of demolitions – “There are about 100 illegal homes which have been built in the Kopri mangroves, and more demolition drives are being planned in coming days,” said Virendra Tiwari, additional principal chief conservator of forests, mangrove cell. (Times, 2022). the forest department-initiated prosecution against seven people for erecting six shanties on CRZ-1 land, and action has been planned against another 100 such structures.

While on the other side, The Maharashtra State Road Development Corporation is planning to ax 1,800 mangroves to make way for the project. Similarly, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) plans to transplant mangroves on 87 acres of land from Mumbai to Thane for its proposed sewage treatment plant (STP) in Malad. The Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA), undertaking the Mumbai Trans Harbour Link (MTHL), will take over 47 hectares of mangrove land in Raigad. A significantly large chunk of Mangroves was destroyed in Navi Mumbai at the site of the new International Airport. (Adimulam, 2022). The authorities are bending the rules to their discretion to further the development plans at the cost of the destruction of mangroves. At the same time, demolishing slums simultaneously to showcase the ‘protection’ of mangroves seems like a strategy to compensate. Under such precedents, The newly given protection to the Dharavi mangroves, while positive for the environment, could also prove to be a gentrifying force for the settlement.

Cases from Mumbai 32

The Predicament of Slum Residents

The SRA- Slum Rehabilitation Authority is the authority responsible for taking over land from slums and providing them with affordable housing. The scheme works where a builder or developer buys that plot of land and promises to offer a particular portion of the new development as housing to the displaced slum residents. Only specific minimum considerations are made mandatory under this scheme. With their power and wealth, the builders bend the rules and end up providing only a percentage of housing to the residents. This does not enable adequate housing – and the selection is made on a random lottery basis leaving the others homeless and displaced to find shelter in other slums. (Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA), 2022) These alternate housing, while equipped with kitchen and sanitation services, are very poorly designed. Budget cuts are extreme because the builders want to put money in their own pockets, and very few resources are dedicated to the SRA houses. Large families crammed into tiny oneroom houses and less than minimal light and

ventilation. The builders usually implement the designs so that common public places like gardens and community centers are designed for the new development, thus restricting access to the SRA residents. When possible, the builders manage to displace communities away from their original site, and the displaced locations are usually far or unsanitary. The communities of Ambedkar Nagar were given alternate SRA housing located next to chemical plants and a refinery, and residents there had already fallen ill. (Chandrashekhar, 2022). The ignorance in making equitable public policies and ensuring the proper implementation keeps the residents away from their Right to amenities and is subjecting them to serious health hazards. Suppose this goes on in the same manner. In that case, the climate action development that Mumbai is supposed to see in the next 30 years will only increase the risk of green gentrification in the city and put more than half its population at life-threatening severe risks.

33 The Predicament of Slum Residents

The Predicament of Slum Residents 34

Figure 25. A portrain from slum demolition. (Demolition drive in Mumbai’s Ambedkar Nagar, 2022)

ConclusionSome of the current issue may have been avoided if the State and industry, which had supported Mumbai’s rise, had made proper plans for migrant workers and their need for affordable accommodation. The government’s policy has instead been inconsistent and loosely structured. A city must consider the geography, climate, and local context when developing its climate action plans, but what they often overlook is how crucial it is to implement fair and inclusive climate action measures.

The idea is to put the needs of people first and consider which communities or frontline groups in my city are most affected by climate change. Who has access and who doesn’t when it comes to taking action on climate change? To create policies that reach the widest possible audience, especially those who are most in need, city planners must be aware of how access to services and policies varies among segments of the urban population.

Unintended effects of green gentrification might happen as a result of a climate action plan’s greening measures when equity is not taken into account. Lower-income citizens may be

priced out of a city by investments in sustainable infrastructure made by high-income company owners and developers combined with a lack of equitable planning rules. If left unattended, these catastrophes may prevent the full range of benefits from climate action.

Mumbai’s climate change inequities may be addressed through environmentally fair urban climate action, but only if local governments prioritise putting people at the centre of their planning process. Although the absence of natural light and ventilation, the terrible quality of the housing, and the lack of sanitary facilities do not merit celebration, practitioners might merely pause to consider how squatters had already conquered so much before our ideas were ever developed. Everyone has a right to the natural world and the environment. Fighting for these equitable rights and constructing cities that are really sustainable and climate resilient should be our purpose as architects and landscape designers.

34 Conclusion

Conclusion 36

Figure 26. A street graffiti on the streets of Mumbai as an opposition to the government activitiesthe graffiti says ‘ There is a limit to your Hypocrisy ‘ (Not green, but greenwash, 2022)

Bibliography

C40 Cities. 2022. C40 Cities - A global network of mayors taking urgent action to confront the climate crisis and create a future where everyone can thrive.. [online] Available at: <https://www.c40.org/> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Climateactiontracker.org. 2022. India - Target update - 01/11/2021. [online] Available at: <https:// climateactiontracker.org/climate-target-update-tracker/india/2021-11-01-2/> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Cole, H., Triguero-Mas, M., Connolly, J. and Anguelovski, I., 2022. Determining the health benefits of green space: Does gentrification matter?.

Downtoearth.org.in. 2022. PM’s climate change council has not met in almost 7 years. [online] Available at: <https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/climate-change/pm-s-climate-change-councilhas-not-met-in-almost-7-years-80369> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Jelks, N., Jennings, V. and Rigolon, A., 2022. Green Gentrification and Health: A Scoping Review. Levin, K., Boehm, S. and Carter, R., 2022. 6 Big Findings from the IPCC 2022 Report on Climate Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. [online] World Resources Institute. Available at: <https://www.wri. org/insights/ipcc-report-2022-climate-impacts-adaptation-vulnerability?utm_medium=cpc&utm_ source=google&utm_campaign=ipcc2022&gclid=CjwKCAjwwo-WBhAMEiwAV4dybXxTBmEGK2QQ2 6uOUExH92ETYA6Izp8LRNzTzpla30aEYNLIOQ_HbhoCNG8QAvD_BwE> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Nathan, A., 2019. Climate is the Newest Gentrifying Force, and its Effects are Already Re-Shaping Cities - Science in the News. [online] Science in the News. Available at: <https://sitn.hms.harvard. edu/flash/2019/climate-newest-gentrifying-force-effects-already-re-shaping-cities/> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Phillips, M., Smith, D., Brooking, H. and Duer, M., 2021. Re-placing displacement in gentrification studies: Temporality and multi-dimensionality in rural gentrification displacement. Geoforum, 118, pp.66-82.

Resourcecentre.c40.org. 2022. C40 Climate Action Planning Resource Centre. [online] Available at: <https://resourcecentre.c40.org/resources/inclusive-climate-action> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Rodgers, H., 1964. Book Review: London : Aspects of Change, Centre for Urban Studies Report No. 3, MacGibbon & Kee, 1964, pp. 342, 55/-. Urban Studies, 1(2), pp.208-210.

Sinha, A., 2022. Explained: Reading India’s announcement on climate targets. [online] The Indian Express. Available at: <https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/india-announcement-climate-

Bibliography

targets-7608525/> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Velázquez, B., 2017. Neil Smith: Gentrificación urbana y desarrollo desigual [Neil Smith: Urban gentrification and uneven development] ed. by Luz Marina García Herrera and Fernando Sabaté Bel. Journal of Latin American Geography, 16(3), pp.174-177.

WRI INDIA. 2022. WRI INDIA. [online] Available at: <https://wri-india.org/> [Accessed 5 July 2022]. Zérah, M. and Landy, F., 2022. Nature and urban citizenship redefined: The case of the National Park in Mumbai. [online] Academia.edu. Available at: <https://www.academia.edu/ es/74229706/Nature_and_urban_citizenship_redefined_The_case_of_the_National_Park_in_ Mumbai> [Accessed 5 July 2022].2022. [online] Available at: <http://spaenvis.nic.in/index1. aspx?lid=5305&mid=1&langid=1&linkid=1591> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

2022. [online] Available at: <https://www.census2011.co.in/census/city/365-mumbai. html#:~:text=Although%20Mumbai%20city%20has%20population,males%20and%20 8%2C522%2C641%20are%20females.> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Adimulam, 2022. Only 12% of 5,000 hectares notified land encroached: Mangrove authority. [online] Free Press Journal. Available at: <https://www.freepressjournal.in/cmcm/only-12-of-5000-hectaresnotified-land-encroached-mangrove-authority> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Chandrashekhar, V., 2022. Climate Change Is Stretching Mumbai to Its Limit. [online] The Atlantic. Available at: <https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2022/02/mumbai-flooding-climatechange/621471/> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

deshpande, a., 2022. Mumbai’s coastline set for a sea change. [online] Thehindu.com. Available at: <https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/mumbai/mumbais-coastline-set-for-a-sea-change/ article34055839.ece> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Express, 2022. Forest dept to take over mangroves in Dharavi area. [online] The Indian Express. Available at: <https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/forest-dept-to-take-over-mangrovesin-dharavi-area-7726874/> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Foundation, T., 2022. Flood-prone Mumbai digs deep to turn climate change tide. [online] Longreads. trust.org. Available at: <https://longreads.trust.org/item/Mumbai-C40-cities-network> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Hindustan Times. 2022. More than 1,000 illegal structures on mangrove area in Mumbai razed. [online] Available at: <https://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/more-than-1-000-illegal-structureson-mangrove-area-in-mumbai-razed/story-c8lAYfiDjTtPOPJVapNUdJ.html> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Bibliography

Lopes, F., 2022. How A Case Sets A Dangerous Precedent For Environmental Protection. [online] Indiaspend.com. Available at: <https://www.indiaspend.com/governance/how-a-case-sets-adangerous-precedent-against-protecting-the-environment-816090> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Nation, T., 2022. Mumbai’s monsoon misery. [online] Frontline.thehindu.com. Available at: <https:// frontline.thehindu.com/the-nation/article28881845.ece#:~:text=Since%20the%20deluge%20of%20 2005,the%20devastation%20when%20it%20occurs.> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Pib.gov.in. 2022. Urban Forest scheme to develop 200 ‘Nagar Van’ across the country in next five years. [online] Available at: <https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1629563#:~:text=On%20 the%20occasion%20of%20World,bodies%2C%20NGOs%2C%20Corporates%20and%20local> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Quint, T., 2022. QMumbai: Dharavi to Be Revamped; Coastal Road Plans Revealed. [online] TheQuint. Available at: <https://www.thequint.com/news/india/mumbai-news-today-coastal-road-dharavirevamp> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Sra.gov.in. 2022. Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA). [online] Available at: <https://sra.gov.in/ dashboard> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

The Sunday Guardian Live. 2022. BMC completes corals’ translocation process for controversial road project - The Sunday Guardian Live. [online] Available at: <https://www.sundayguardianlive. com/news/bmc-completes-corals-translocation-process-controversial-road-project> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Times, H., 2022. Mangrove cell starts demolition drives in newly-acquired areas. [online] Hindustan Times. Available at: <https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/mumbai-news/mangrove-cell-startsdemolition-drives-in-newly-acquired-areas-101649854517577.html> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

2022. [online] Available at: <https://hindrise.org/resources/slum-dwellers-in-india/> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

Gould, K. and Lewis, T., n.d. Green gentrification.

ClimateChange, U. N. (2015). Adoption of the Paris Agreement. Paris: United Nations.

ClimateWatch. (2019). Global Historical Emissions. ClimateWatch. Retrieved from https://www. climatewatchdata.org/ghg-emissions?end_year=2019&start_year=1990

David Eckstein, V. K. (2021). Global Climate Risk Index 2021. Germanwatch. Retrieved from https:// www.germanwatch.org/en/19777

Bibliography

Donovan, G. H. (2020). The politics of urban trees: Tree planting is associated with gentrification in Portland, Oregon. ScienceDirect.

EnergyReviews, R. a. (n.d.). GHG footprint of Major cities in India. Energy and Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences(CES), Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, T.V. Ramachandra, Bharath H. Aithal, K. Sreejith. Retrieved from http://wgbis.ces.iisc.ernet.in/energy/paper/GHG_ footprint/discussion.html

Fernando, B. (2014, March 31). Dharavi Biennale on Mumbai. The Guardian.

Jina, M. G. (2019). Report on Climate Change and Heat-induces Mortality in India. TCDU. Retrieved from https://tcd.uchicago.edu/insight/report-on-climate-change-and-heat-induced-mortality-inindia/#:~:text=Six%20states%2C%20Uttar%20Pradesh%20(402%2C280,rises%20caused%20by%20 climate%20change.

Maharashtra, G. o. (2022). Mumbai Climate Action Plan 2022. Retrieved from https://mcap.mcgm.gov. in/

Maria Hart, J. D. (2019, 12). How to Prevent City Climate Action from Becoming “Green Gentrification”. WRI, World Resources Institute. Retrieved from https://www.wri.org/insights/how-prevent-cityclimate-action-becoming-green-gentrification

MCAP, G. o. (2022). Mumbai Climate Action Plan 2022. Mumbai. Retrieved from https://drive.google. com/file/d/1gU3Bnhk3UJ_wCFaMC1ognZBdsdDkQBY1/view

Nathan, A. (2019, July 15). Climate is the Newest Gentrifying Force, and its Effects are Already ReShaping Cities. SITN, Harvard Graduate School of the Arts and Sciences. Retrieved from https://sitn. hms.harvard.edu/flash/2019/climate-newest-gentrifying-force-effects-already-re-shaping-cities/ Sharma, K. (2000). Rediscovering Dharavi. Delhi: Penguin.

Un-Habitat. Slums of the World: THe face of urban poverty in the new millenium? 2003b.

Bibliography

List of Figures

FIGURE 1. THE UNEQUAL SCENES OF MUMBAI’S DEMOGRAPHIC UNEQUALSCENES.COM. 2022. UNEQUAL SCENES - MUMBAI. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://UNEQUALSCENES.COM/ MUMBAI> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 2. KIDS PLAYING ON TRAIN TRACKS DUE TO LACK OF ACCESS TO GREEN AND PLAY SPACES IN MUMBAI’S SLUMS CHARLTON, C., 2022. THE SLUM IN INDIA WHERE CHILDREN PLAY ON ACTIVE TRAIN TRACKS. [ONLINE] MAIL ONLINE. AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW. DAILYMAIL.CO.UK/NEWS/ARTICLE-3097192/THE-FILTHY-DANGEROUS-LIFE-INDIA-S-POORESTSLUM-CHILDREN-PLAY-TRAIN-TRACKS-PARENTS-COOK-BAMBOO-SHELTERS-JUST-FEET-AWAYONRUSHING-CARRIAGES.HTML> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 3. A LANDSCAPE PHOTOGHRAPGH SHOWING THE DIFFERENCE IN INFRASTRUTURE OF MUMBAI WITH SLUMS IN THE FOREGROUND AND TALL BUILDINGS IN THE BACKGROUND UNEQUALSCENES.COM. 2022. UNEQUAL SCENES - MUMBAI. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS:// UNEQUALSCENES.COM/MUMBAI> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 4. GOOGLE EARTH IMAGE SHOWING HE LOCATION OF BKC ALONG THE MITHI RIVER. THE SLUMS OF DHARAVI CAN BE SEEN ON THE RIGHT OF THE RIVER CHANNEL. GOOGLE EARTH. 2022. OVERVIEW – GOOGLE EARTH. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.GOOGLE.COM/ EARTH/INDEX.HTML> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 5. A DHARAVI PORTRAIT AMBWANI, K., 2022. INDIA: DHARAVI SLUM. [ONLINE] MONTREAL PORTRAIT, EDITORIAL, DOCUMENTARY & HUMANITARIAN PHOTOGRAPHER KIRAN AMBWANI. AVAILABLE AT: <HTTP://EN.KIRANAMBWANI.COM/INDIA-DHARAVI-SLUM.HTML> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 6. AN AREIAL SHOT OF THE SLUMS OF DHARAVI. UNEQUALSCENES.COM. 2022. UNEQUAL SCENES - MUMBAI. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://UNEQUALSCENES.COM/MUMBAI> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 7. AN ILLUSTRATED MAP OF MUMBAI SHOWING THE CURRENT CITY ON BACKGROUND AND OVERLAYED WITH THE SIZE OF ORIGINAL SEVEN ISLANDS OF MUMBAI. 2022. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.RESEARCHGATE.NET/FIGURE/SEVEN-ISLANDS-ALONG-WITHFLOOD-SPOTS_FIG5_338391464> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 8. BOMBAY’S FAMOUS FORT, CIRCA 1850: BY THIS TIME, THE SEVEN ISLETS HAD BEEN CONNECTED TO FORM A CONTIGUOUS CITY. THE GUARDIAN. 2022. STORY OF CITIES #11: THE

List of Figures

RECLAMATION OF MUMBAI – FROM THE SEA, AND ITS PEOPLE?. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.THEGUARDIAN.COM/CITIES/2016/MAR/30/STORY-CITIES-11-RECLAMATIONMUMBAI-BOMBAY-MEGACITY-POPULATION-DENSITY-FLOOD-RISK> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 9. THE HORNBY VELLARD, COMPLETED IN 1784, IS SAID TO HAVE GIVEN SHAPE TO THE MODERN CITY OF MUMBAI. THE GUARDIAN. 2022. STORY OF CITIES #11: THE RECLAMATION OF MUMBAI – FROM THE SEA, AND ITS PEOPLE?. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW. THEGUARDIAN.COM/CITIES/2016/MAR/30/STORY-CITIES-11-RECLAMATION-MUMBAI-BOMBAYMEGACITY-POPULATION-DENSITY-FLOOD-RISK> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 10. GOOGLE EARTH IMAGE SHOWING THE SPREAD OF MUMBAI SLUMS. MUMBAI-SLUMSEGMENTATION. 2022. MUMBAI SLUM SEGMENTATION. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS:// CBSUDUX.GITHUB.IO/MUMBAI-SLUM-SEGMENTATION/> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 11. A SERIES OF MAP SHOWING THE DIFFERENCE IN GREEN COVER IN MUMBAI FROM 1998 TO 2018 2022. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.RESEARCHGATE.NET/FIGURE/ SEVEN-ISLANDS-ALONG-WITH-FLOOD-SPOTS_FIG5_338391464> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 12. A SERIES OF MAP SHOWING THE DIFFERENCE IN URBAN HEAT FROM 1991 TO 2018. 2022. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.RESEARCHGATE.NET/FIGURE/SEVEN-ISLANDSALONG-WITH-FLOOD-SPOTS_FIG5_338391464> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 13. AN OFFICIAL DOCUMENT- MAP SHOWING THE OFFICIAL DEMARKATION OF SLUM OCCUPIED LAND IN MUMBAI. FACEBOOK.COM. 2022. WRI INDIA - #WRIINDIAGEOANALYTICS THIS MAP SHOWS THE.... [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/WRIINDIA/ PHOTOS/A.760022914081302/3486349728115260/?TYPE=3> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 14. A DAY IN DHARAVI PHOTOGRAPH. AMBWANI, K., 2022. INDIA: DHARAVI SLUM. [ONLINE] MONTREAL PORTRAIT, EDITORIAL, DOCUMENTARY & HUMANITARIAN PHOTOGRAPHER KIRAN AMBWANI. AVAILABLE AT: <HTTP://EN.KIRANAMBWANI.COM/INDIA-DHARAVI-SLUM.HTML> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 15. SNAPSHOTS FROM MCAP SHOWING THE 4 PILLARS OF MCAP’S VISION (ABOVE) AND THE 6 STRATEGIES BY WHICH THE MACP AIMS TO MEET ITS GOALS. 2022. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://MCAP.MCGM.GOV.IN/> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 16. ECOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE OF MUMBAI AS SHOWN IN THE MCAP. 2022. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://MCAP.MCGM.GOV.IN/> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 17. A SNAPSHOT FROM THE VIDEO LAUNCHED BY THE MUMBAI GOVERNMENT FOR THE PROPOSAL OF COASTAL ROAD DEVELOPMENT. THE VISUALS TELL A STORY OF THE GREEN AND

List of Figures

SUSTAINABLE DESIGN OF THE FREEWAY. YOUTUBE.COM. 2022. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS:// WWW.YOUTUBE.COM/WATCH?V=VYM_RAQ77KW> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 18. SHAPSHOTS (AERIAL VIEW TOP AND MAP BOTTOM) FROM THE VIDEO LAUNCHED BY THE MUMBAI GOVERNMENT FOR THE PROPOSAL OF COASTAL ROAD DEVELOPMENT. THE VISUALS TELL A STORY OF THE GREEN AND SUSTAINABLE DESIGN OF THE FREEWAY. YOUTUBE. COM. 2022. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.YOUTUBE.COM/WATCH?V=VYM_RAQ77KW> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 19. IMAGES FROM THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COASTAL ROAD. YOUTUBE.COM. 2022. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.YOUTUBE.COM/WATCH?V=VYM_RAQ77KW> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 20. A SNAPSHOT FROM THE VIDEO LAUNCHED BY THE MUMBAI GOVERNMENT FOR THE PROPOSAL OF COASTAL ROAD DEVELOPMENT. THE VISUALS TELL A STORY OF THE GREEN AND SUSTAINABLE DESIGN OF THE FREEWAY. YOUTUBE.COM. 2022. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS:// WWW.YOUTUBE.COM/WATCH?V=VYM_RAQ77KW> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 21. NEWS EXCERPTS ABOUT THE ENVIRONEMNTAL HARM CAUSED TO CORAL HABITAT IN THE COASTAL ROAD DEVELOPMENT PROJECT. NEWS, C. AND NEWS, M., 2022. CORALS MAY NOT SURVIVE SHIFT FROM COASTAL ROAD PROJECT SITE: EXPERTS | MUMBAI NEWS - TIMES OF INDIA. [ONLINE] THE TIMES OF INDIA. AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://TIMESOFINDIA.INDIATIMES. COM/CITY/MUMBAI/CORALS-MAY-NOT-SURVIVE-SHIFT-FROM-COASTAL-ROAD-PROJECT-SITEEXPERTS/ARTICLESHOW/78965071.CMS> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 22. IMGAES FROM THE PROTEST BY FISHERMEN COMMUNITY OF THE WORLI SLUM SHOWING THEIR OPPOSE TO THE PROJECT. SABRANGINDIA. 2022. MUMBAI’S KOLI FOLK DECRY COASTAL ROAD PROJECT | SABRANGINDIA. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://SABRANGINDIA. IN/ARTICLE/MUMBAIS-KOLI-FOLK-DECRY-COASTAL-ROAD-PROJECT> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 23. GOOGLE EARTH VIEW SHOWING THE LOCATION AND SPREAD OF DHARAVI SLUMS ALONG THE MITHI RIVER AND THE DHARAVI MANGROVES. (ZOOMED OUT IMAGE:ABOVE, ZOOMED IN IMAGE: BELOW) GOOGLE EARTH. 2022. OVERVIEW – GOOGLE EARTH. [ONLINE] AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.GOOGLE.COM/EARTH/INDEX.HTML> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 24. THE DEMOLITION OF ILLEGAL STRUCTURES FROM MANGROVE PROTECTED AREAS. SINGH, V., 2022. SOUTH MUMBAI SLUMS RAZED, MANGROVES SAVED. [ONLINE] DNA INDIA. AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.DNAINDIA.COM/MUMBAI/REPORT-SOUTH-MUMBAI-SLUMSRAZED-MANGROVES-SAVED-2429809> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

FIGURE 25. A PORTRAIN FROM SLUM DEMOLITION. SINGH, V., 2022. SOUTH MUMBAI SLUMS

List of Figures

RAZED, MANGROVES SAVED. [ONLINE] DNA INDIA. AVAILABLE AT: <HTTPS://WWW.DNAINDIA. COM/MUMBAI/REPORT-SOUTH-MUMBAI-SLUMS-RAZED-MANGROVES-SAVED-2429809> [ACCESSED 5 JULY 2022].

Figure 26. A street graffiti on the streets of Mumbai as an opposition to the government activities - the graffiti says ‘ There is a limit to your Hypocrisy ‘ Thehindu.com. 2022. Not green, but greenwash. [online] Available at: <https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/not-green-but-greenwash/article29717161. ece> [Accessed 5 July 2022].

List of Figures

History of Mumbai and it’s Slums

History of Mumbai and it’s Slums