Fifty

10:10 Magazine Issue 7 2022

years on, Audemars Piguet’s acorn has grown into a phenomenon Who needs a calendar when you could wear a Vacheron Constantin? How Chanel’s Première opened the stopper on the chicest horological legacy FINE DATE CHRONO COCO MIGHTY OAK 10 10

FROM ICON OCLAST TO ICON AUDEMARS PIGUET BOUTIQUES LONDON : SLOANE STREET · HARRODS FINE WATCHES AP HOUSE LONDON : NEW BOND STREET FROM ICON OCLAST TO ICON AUDEMARS PIGUET BOUTIQUES LONDON : SLOANE STREET · HARRODS FINE WATCHES AP HOUSE LONDON : NEW BOND STREET

“ ONCE

I DREAMED TO BECOME THE FASTEST DRIVER. TODAY, I AM A DRIVER OF CHANGE. I AM A BIG PILOT. ”

LEWIS HAMILTON, 7

TIME

FORMULA 1 TM WORLD CHAMPION

THE BIG PILOT.

Bold, iconic and genuine: The Big Pilot’s Watch is the timepiece of choice for individuals driven by passion, purpose and a desire to create.

For the first time, IWC’s most essential aviator’s watch is available in a 43-millimetre case, combining the purity of the original cockpit instrument design with superior ergonomics and pronounced versatility.

138, NEW, BOND ST, LONDON W1S 2TJ, UNITED KINGDOM

BIG PILOT’S WATCH 43

EDITORʼS LETTER

Editor-In-Chief

Dan Crowe

Creative Director

Astrid Stavro

Design

Astrid Stavro

Alessandro Molent Editor

Alex Doak Fashion Director

Mitchell Belk Accessories Editor

Serene Khan Sub-Editor

Kerry Crowe Sub-Editor

Sarah Kathryn Cleaver

Photography

Benjamin Swanson Leandro Farina

Phil Dunlop

John Gribben Baker & Evans

Cover Photography

Vacheron Constantin by Benjamin Swanson Chanel by Phil Dunlop

Audemars Piguet by Leandro Farina

Publishers

Dan Crowe, Matt Willey

Associate Publisher

Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono

Advertising Director Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono andrew@port-magazine.com

Typefaces

A2 Record Gothic by A2-Type (A2/SW/HK) Quadraat Pro by Type By Pitch by Klim Type Foundry

Contact

Port Magazine

Somerset House London, WC2R 1LA +44 (0)20 3119 3077 port-magazine.com

Is it 10:10, or do you read it as 22:10?

This issue of Port is themed around ‘mirrors’, and just as this seventh annual 10:10 supplement devoted to horology finishes with a reflective moment in Amélie (figuratively in the case of a painter’s quest to mirror an elusive subject of Renoir’s), the masthead that forms our other bookend reflects something of you, the reader.

Typographically, ‘10:10’ is neater. For watchmakers, the minutes and hours hands photograph better in that position – an optimistic ‘V’ for victory. But what time is it? Are you more optimistic about life around 10 in the morning? Or 12 hours later in the day?

It’s just one of the many things a watch reflects of its wearer. A tiny, round looking glass on your wrist, projecting your style, mood and status (humble or otherwise). It’s always by your side, anticipating and measuring your every quotidian activity, often with astonishing precision – but time itself is a human construct, whose passing speed we freely admit is in the eye of the beholder, despite that steadfast ‘tick’ from inside.

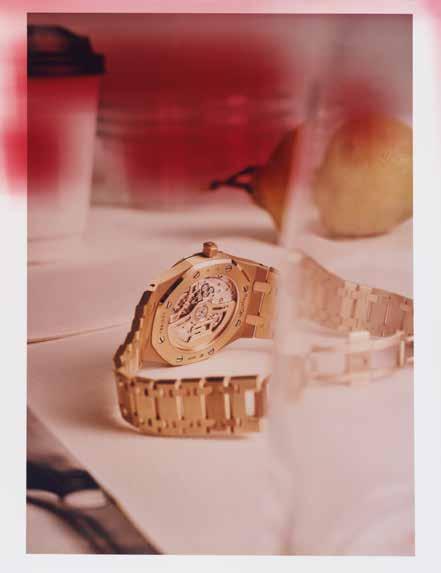

Turn it over, and the finer mechanical creations from Switzerland or Germany offer another looking glass: a window into their minuscule works, which in turn reflect centuries of human endeavour in micro-engineering and machining, finetuning and restless innovation.

If you haven’t already, it’s about time you invested in a decent watch. For the simple reason that it’s not about time at all.

Alex Doak

10:10 Magazine Editor's Letter

8 Issue 7

9 Editor's Letter

Illustration: Indgila Samad Ali

10 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 Contents WINTER WATCH TOP CRUCIFORM OVER THE RAINBOW SPACES ACES TO (BOTH) ENDS OF THE EARTH ARCHITELIER MAKING A DATE SAFE PAIR OF HANDS FIRST TIME TICKIN’ JOY RICH TAPESTRY DRESS CODE CAMERA OBSCURA CONTENTS p.11 p.14 p.12 p.16 p.18 p.20 p.24 p.30 p.40 p.44 p.50 p.54 p.64

WINTER WATCH

Normally in the business of airborne utility, Paris’s Bell & Ross breaks the ice with cool, breezy élan

A professional pilot’s wristwatch needs to be three things: trusty, barefacedly functional, and talismanic – pilots being superstitious sorts. A wilfully anachronistic, yet dogged mechanical timepiece ticks all those boxes.

If a watchmaker finds itself particularly successful in the air, expanding into Civvy Street by association with high-altitude derring-do is a no-brainer.

But where to go when every variation of white-on-black, luminescent, instrumentally circular design has been explored? IWC is sticking to the script with its Pilot’s collection, born of both RAF and Luftwaffe enlistment during WWII; the same chez Breitling, its Navitimer feeling the need for speed for 70 solid years now. All evergreen classics, both in the air and on the high street.

Back in the ‘90s, it fell to magnificent messieurs Bell & Ross and their flying micro machines to prove there was elbow room on the design front, while maintaining cockpit credentials. It

helped that the design studio was in Paris, not far-from-fashionable Switzerland, where the watches are made, but also that founders Bruno ‘Bell’ Belamich and Carlos ‘Ross’ Rosillo took cues from the instruments a pilot depends on, rather than going wilfully abstract.

To whit, the BR 01/03/05 ‘Instrument’ line: square with four screws at each rounded corner like an altimeter or virtual horizon, and most importantly, big

What you see here, the just-dropped BR X5 Ice Blue, is probably the most ‘fashion’ that Bell & Ross will allow its BR 05 to go, before tipping into non-utility. There’s a sporty, integrated bracelet topped by a steely colourway, taken into ‘X’ territory by a more avant-garde case construct.

Piercing dial luminescence and failsafe mechanical precision ensure things pass muster at the officer’s mess, but let’s face it: wouldn’t you rather wear it on leave?

Out now, priced at £5,900 on rubber, £6,500 with steel bracelet

11

Words: Alex Doak

Winter Watch

TOP CRUCIFORM

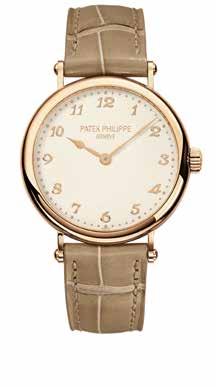

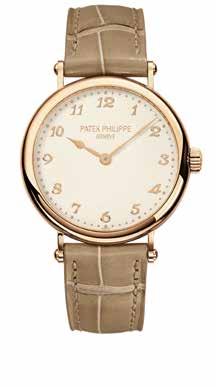

Geneva’s grandmaster of horology has always flown the Calatrava cross, so it’s only fitting Patek Philippe named its most iconic model after the house’s crowning motif. Still every purist’s purest ‘grail’ dress watch, the Calatrava takes its name from the ornate symbol used on the marching banners of the knights who defended the Calatrava fortress against the Moors in 1158. This same symbol was registered as a trademark in 1887, spurred by a wave of brazen counterfeits, plus the dubious practice of signing watches with names easily confused with ‘Patek Philippe’ –‘Pateck & Cie’ among them, adorning a dial exhibited at Antwerp’s world fair in 1885 by A. Schwob & Frères, despite them knowing full-well Jean Adrien Philippe was on the panel of judges. First denoted by reference number ‘96’, every Calatrava design is simplicity itself: sober bezel encircling two central-axis hands, hours marked by batons or numerals, small sub-dial at six o'clock indicating passing seconds (as well as whether it needs a wind). Exactly what a wristwatch should look like, and would continue to look like… until this year’s shock drop.

1932

Timepieces had always been identified by their case numbers; never accorded catalogue names or model designation. Times were changing however, and younger, more marketing-savvy brands were dreaming up product names, which customers could specifically request (‘Oyster’ from recently launched Rolex was particularly notable). The ‘96’ Calatrava was launched in steel in 1932, powered by LeCoultre mechanics until 1934, when PP were urged by the popularity of wrist over pocket watches to develop its own small movements. Inspired by the Bauhaus principle of form following function, 96 remains a stone-cold classic, its minimalist lines virtually unchanged for 90 years.

1982

Reference 3796 was Patek Philippe’s last original-size Calatrava – measuring a dainty 31mm across, almost inconceivable as a man’s watch today. It replaced 96 until the ’90s, differing only with its sapphire crystal dome, plus the new, manually wound calibre 215 PS (petite secondes) ticking inside.

1953

It says everything of how perfect the 96 was that it took over two decades before Calatrava changed in any major way. The 2526’s ‘double-baked’ enamel dial covered Patek Philippe’s debut self-winding movement, 22 years after Rolex first perfected the weighted ‘rotor’ system, spinning and winding with every arm movement. PP’s 12.600 AT calibre was the future of watchmaking – still regarded as one of the best-ever automatics.

1985

In production till 2006, the Calatrava ref. 3919 nonetheless sported a diminutive 33.5mm-diameter case, whose most distinguishing feature is of course that ‘Clou de Parisʼ, or hobnail-engraved bezel. A relatively ritzy embellishment, recently reintroduced to the upscaled Calatrava collection with dazzling effect, this double ring of polished, miniature pyramids reflects eye-catchingly (while hiding the odd scratch), while justifiably demanding Roman numerals over batons.

12 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 Top Cruciform

2006

Now with a lacquer dial, rather than enamel, and upped to a positively stately 36mm, ref. 5119 took the 3919 firmly into the 21st century. Lengthening the numerals to grandfather-clock proportions was the clincher, complementing the hobnail bezel better than ever. (The current-catalogue evolution, ref. 6119, has batons instead, a 39mm case, and is – whisper it –1010’s favourite.)

2006

By the mid-noughties, watchmakers were finally waking up to women; they didn’t just want ‘shrink, pink’ versions of their husband’s watch, covered in diamonds with a token quartz movement inside. Enter ref. 4896: ticking with Patek’s wafer-thin ʻ16-250’ mechanics (just 2.5mm high), capped by a dial of guilloché-engraved waves and sumptuous midnight-blue lacquer.

2013

You need to de-wrist to note the defining characteristic of ref. 5227 – front-on, a Calatrava like any other. Rear side, it has an officer’s style case with a hinged back plate that reveals the sapphire-crystal display window into the calibre 324 SC mechanics – the ‘S’ denoting a ‘Spiromax’ balance spring made with antimagnetic silicon. Outwardly, classical as it gets; inwardly, as deceptively future-forward as Patek always has been.

2019

Five hands in total, their cylindrical axes all Russian-dolled about the same, central point. It’s an extraordinary feat of micro-engineering in its own right, let alone a departure for the inherently pared-back Calatrava. But that wasn’t what people were talking about at 2019’s spring fair: it was the dial’s typography. Created explicitly for ref. 5212, it’s the handwriting of one of Patek’s own designers – a poetic flourish recalling paper journals, being its first calendar piece indicating week of the year, as well as day, date and month.

2013

Half of this year’s novel output from Switzerland’s prima donna of watchmaking was devoted to women, and ref. 7200 was undoubtedly the diva – albeit a self-effacing diva. Without a small seconds sub-dial, things were even subtler thanks to the use of calibre 240, whose winding rotor comes in micro form, embedded flush with the 10-pence movement’s bridges and plates.

2022

Ref. 5226G-001 White Gold, to give it its full name (£31,430 to give it its RRP; good luck elsewhere) was quite the curveball of Geneva’s Watches & Wonders spring trade show. A contemporary redux of watchmaking’s most classic design, with trendy, ‘vintage’ pilot vibes? Cynical purists may balk, but anyone who knows Patek – or anyone who enjoyed in-themetal wrist time in April – knows that it will entertain an instant, salivating wait list. The Calatrava saga ticks on…

13

Words: Alex Doak

Top Cruciform

OVER THE RAINBOW

In 1963, a now-household name from New Jersey revolutionised the printing industry by creating a lexicon of colour: selectable and communicable worldwide, guaranteed tone-correct every time. Today, we’re all social-media aesthetes, and with that Pantone has become as much of a lifestyle choice as a publisher’s choice of 3,060 ‘spot’ colours, plus 6,732 ‘process’ colours mixed from printing’s usual font of cyan, magenta, yellow and black ink – all selected from that doorstop of a fan book of swatches.

It’s why anyone who doesn’t know their C or M from their Y and K may nonetheless own a mug purchased from a museum shop broadcasting their favoured shade of tea; it’s also why the interiors pages of fashion glossies draw so keenly from 2022’s hotly anticipated ‘Colour of the Year’ (for the record: ‘Very Peri’ blue, no.17-3938).

Thanks to a particularly involved partnership with historic Swiss brand IWC, and recent strides in materials engineering, Pantone’s sensitivity

to product as well as pigment is now benefitting wristwatch ownership.

“The colours we wear and the colours we surround ourselves with reflect who we are and how we want others to perceive us,” said Laurie Pressman, vice-president of the Pantone Colour Institute during April’s Watches & Wonders gala in Geneva.

“[Crucially for brands] colour is the first thing we see and the first thing we connect to, influencing up to 85% of product purchasing decisions… How brands put their colour themes and stories together is so important.”

At the same talk, IWC’s creative head Christian Knoop reminded us of how the brand was a pioneer of white and black ceramic watches as early as in the 1980s, around the time Rado was coining its own monochromatic visions of the future. Behind the scenes, IWC’s boffins were also toying with prototypes in blue, green and even pink.

As is still the case in ceramic watchmaking, zirconium oxide is mixed with other metallic oxides, shaped and

14 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 Over the Rainbow

IWC’s elite ‘Top Gun’ aviator watches are feeling the need, the need for chic –co-piloting with colour mavericks, Pantone

‘IWC Woodland’ is one of two new Pantone colours coined in ceramic watch form, AKA ‘PQ-5605C’. It now has a permanent place in Pantone’s Plastic Standard Chips colour system for fashion, home and interiors. The chips have two levels of thickness and are made using polypropylene resin, denoted by a ‘PQ’ followed by a dash and the three — or four — digit colour number (corresponding to the Pantone Matching System) plus a ‘C’.

then sintered at around 900ºC – shrinking by a third in the process, giving you some idea of how tricky it must be turning out components that always fit together to the tolerances demanded by a water-resistant watch case.

Since then, advanced materials have been the hallmark of IWC’s ‘Top Gun’ chronograph collection (yes, as in officially endorsed by Maverick’s real-life alma mater in Fallon, Nevada). More interestingly for Pantone, there’s been more and more experimentation in between the black and white bookends of the spectrum. In 2019 for example, IWC cased up its classic Pilot’s Watch Chronograph in ‘Mojave Desert’ guise – the first-ever ceramic coloured in sand.

IWC has clearly got this on the engineering front. In collaboration

with Pantone though, a creative journey has led to two intriguing new colours: ‘IWC Woodland’ green and ‘IWC Lake Tahoe’ white. Both are inspired by the landscapes flown over by the US Navy’s Strike Fighter Tactical Instructor students; and both are duly included in the core swatch book, available to any one of the 10 million-plus creatives subscribed to its system.

“It was an incredibly elaborate process,” Knoop explains of the difficulties in finding the right mixture of raw materials, then fine-tuning a repeatable production process of consistent tone.

“Colour engineering at this level has never been seen at IWC before,” says Knoop, with rare candour. The sky’s the limit, it seems.

15

Words: Alex Doak

Over the Rainbow

The Omega Speedmaster x Apollo moon shot story is interstellar marketing gold. From those Hasselblad shots of Buzz Aldrin bounding about the lunar dust in 1969, black chronograph faithfully Velcro-ed around his spacesuit, to Kevin Bacon’s Jack Swigert depending on his trusty ‘Speedy’ to time the 14-second burn that aligned the stricken Apollo 13 craft for re-entry (1970 in real life, 1995 as dramatised by Ron Howard), Omega couldn’t buy this sort of PR.

It was NASA who bought it, actually. Omega’s chronograph plus a handful of other Swiss stalwarts were called in by Houston and tested to ruination, the Speedy being the only man standing; ultimately certified fit for manned flight missions. As standard-issue kit, the Swissmade stopwatch was also the only nonbespoke item aboard the lunar module –purchasable by any Tom, Dick or Harry from their friendly local jeweller.

What was to become the Moonwatch was bound for cult status. But March this year saw a switch-up in the Speedmaster story so fanatical that it even caught Omega’s president, Raynald Aeschlimann and Marc Hayek Jr, CEO of mothership Swatch Group by surprise. They never expected weeks-long queues snaking around 110 select Swatch boutiques dotted around the globe at 9am on March 26th.

These are the only places you can buy the MoonSwatch: a £207 quartz Swatch watch that flippers were fetching thousands for the very next day. Bearing the official Speedie logo, its iconic tachymeter scale, and on an astronautspec Velcro strap, it comes in a variety of case colours inspired by our neighbouring planets, made in ‘Bioceramic’ – a 1:2 amalgam of castor-oil polymer with zirconium-oxide ceramic. The result is a silky matte finish that’ll barely scratch, with a killer aesthetic. The fact the

The curveball hypewatch of 2022 and an anniversary reissue are bookending a celestial myth of man and horology itself

16 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 Space Aces

Right: Omega X Swatch Opposite: Breitling Navitimer Cosmonaute SPACE ACES

TO (BOTH) ENDS OF THE EARTH

That is, the top and bottom ends: first adventured respectively by Rolex’s Explorer and Blancpain’s Fifty Fathoms in the very same year. Still conquering Everests and plumbing abysses, it says everything about this brace of plucky Swiss timekeepers that, nigh-on 70 years later, both are still going strong – ticking to pioneering micro-mechanical formulae that’ve barely needed a tweak, from 1953 through 2023

ALTITUDE FITNESS

Like most folklore surrounding Switzerland’s biggest brand, you mention the Rolex vs Smiths debate at your risk anywhere near the internet. If you must (and we really must, for the Rolex in question: the Explorer II is a masterpiece regardless, boasting a sleek new upgrade this year), then it is always best to start with what we know.

Which is: on 29th May 1953, two young men fired with extraordinary determination were the first to reach Mount Everest’s 8,848metre summit. The not-yet-Sir Edmund Hillary and his sherpa, Tenzing Norgay achieved the goal that dozens of other earlier expeditions had failed to accomplish. Also, unlike today’s strictly monitored brand ambassadors, Hillary managed something else extraordinary: to be sponsored by two competing watch brands.

Rolex was the most heavily publicised, and Mr Norgay was dutifully wearing his rugged ‘Oyster Perpetual’ as he stepped onto the top of the world, inspiring the first ‘Explorer’ that same year. Hillary himself

had quietly left his Explorer back at base camp, choosing instead to wear a Smiths watch to the summit – one of 13 that Britain’s biggest watchmaker had issued for the journey. Nonetheless, Hillary was impressed enough by his Rolex’s delicate mechanics’ imperviousness to sub-zero temperatures to feed back to Geneva with the words, “it performed splendidly”.

Who wore what to the summit is academic; anything hoping to survive from base camp upwards must meet untold demands, whether human or timepiece. Which is why ’53’s Explorer endures, now also in ultra-desirable Explorer II guise – souped-up with a bright-orange and oversize 24-hours ‘GMT’ hand, whose modular mechanism connects to the base mechanics (the chronometer-rated Calibre 3187) via a star wheel and click spring for definitive adjustment via the crown, no matter how thick and ice-clad one’s gloves are.

Smiths is long dead and buried. Let us plant a thin-aired flag for Rolex’s skyscraping pluck, grit and stiff upper lip.

18 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 To (Both) Ends of the Earth

Above: Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay

Right: French Naval frogman

Robert

Maloubier

DEPTH CHARGING

Meanwhile in 1953, with the advent, advancement, even glamorisation (merci, M. Jacques Cousteau) of new-fangled ‘SCUBA’, frogmen and hobbyists alike were diving deeper and deeper. Watertight and luminous diving watches became essential kit, simply to keep an eye on how long their gas tanks would last. Enter historic maison Blancpain and its Bathyscaphe: the refreshingly crisp iteration of one of Switzerland’s oldest, most classical brands and its Fifty Fathoms game changer. It’ll never hold a torch to the Submariner’s commercial success, launched the very same year by Rolex, but as the modern take on 1952’s agenda-setting, black-ops prototype, it’s the insider’s diver.

It was commissioned for the Nageurs de Combat unit by the recently deceased Bob Maloubier, a dashing Frenchman who worked for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) during the war. It beat Rolex to the punch with a world-first rotating bezel, allowing dive time to be recorded by aligning its zero marker with the minutes hand, wherever it was on the dial.

Its uni-directional rotation was revolutionary: only turnable anticlockwise, therefore only displaying less remaining dive time should you accidentally knock it on a bit of passing coral – rather than a deceptive surplus of oxygen reserves. This feature was directly informed by then-coCEO (and passionate amateur diver) JeanJacques Fiechter's epiphany following an emergency ascent: he lost track of time and ran out of air, almost lethally.

The Submariner may be the one everyone wants, then duly waits for. But if you’re taking the plunge, isn’t it worth considering a crack operative that flies under the sonar, let alone radar?

19

Words: Alex Doak

To (Both) Ends of the Earth

The most venerable practitioners of haute horology may nurture their craft in necessarily classical fashion, but forget about chocolatebox, timbered chalets with painted shutters –the modern watch manufacture is more likely to be a starkly modernist affair, wedged into the Jura mountain’s rolling slopes, conforming to Switzerland’s eco-forward, net-zero ‘Minergie’ construction standards. Some increasingly grand designs are housing the creation of these miniature masterpieces – juxtaposing their bucolic setting as wilfully as their output is archaic

Maison Vacheron Constantin Photography Maud Guye-Vuilläme 20 Architeliers 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

PLAN-LESWATCHES

Drive southwest out of Geneva’s medieval Old Town and things rapidly yield to scrappy concrete edgeland. Then suddenly: a spotless industrial park in the suburb of Plan-les-Ouates appears, plastered with gleaming überfactories belonging to some of Switzerland’s top brands. Most significantly, Patek Philippe on Chemin du Pont-du-Centenaire, fronted by its famous Spirale sculpture. Next door, there’s Rolex’s mammoth 11-storey building, which covers the area of five football pitches yet solely focuses on the manufacture of cases and bracelets, even operating its own gold foundry on-site.

On the western edge of the park, you’ll find within walking distance of each other Piaget’s jewellery, haute horlogerie and case-making facility, along with Frédérique Constant’s manufacture and Harry Winston’s too. But nestled on the outskirts of the appropriately named Chemin du Tourbillon, you’ll find the most spectacular: Vacheron Constantin.

Designed and built by Swiss-born French architect Bernard Tschumi and his practice (2001–2005), a metal envelope is biomorphically folded over a concrete structure, strangely harmonious with the surrounding parkland and reminiscent of Marc Newson’s early-’90s chrome furniture.

The curved metal envelope is supposed to serve as a levelling, common denominator for both manufacturing and management: traditionally, bluecollar machinists have toiled in gloomy basements, while white-collar artisans and execs were housed in the sunlit upper storeys. The CNC machines will always be street level, given their sheer tonnage, but their operators can hold their heads rightly high.

21

Words: Alex Doak

Architeliers

BOLD AS BRASSUS

Le Brassus is a tiny village in the Vallée de Joux: a meandering 60-minute drive up from Geneva airport into an Elysian field of high-altitude horology. Home also to Blancpain and Jaeger-LeCoultre (all connected by the same spinal road), it was the Silicon Valley of its age, over 150 years ago, pioneering micro-mechanical supercomputers and attracting the finest minds.

Social geography is everything for Swiss watchmaking, and while the Joux is no longer reliant on 19th-century dairy farmers hanging up their cattle prods come the first flurry of winter, pivoting to crafting tiny screws from iron ore mined from the surrounding hills, watchmakers remain proud homebodies. So Audemars Piguet stays stoically put in Le Brassus, where they’ve been since 1875; modernising nevertheless, furtherflung employees doggedly applying snowchains to their tyres every November.

This aspic-preserved industrial model, not to mention AP’s breathless feats of mechanical innovation, are celebrated by a new Musée Atelier annexe (2014–2020), bedded organically into the adjoining valley as a spiral in architectural form –the shape of every mechanical timekeeper’s ticking heart. Bjarke Ingels and his Danish practice BIG have housed the Audemars family’s priceless collection, as well as their most elite watchmakers’ benches, all within cleverly delineated ‘swoops’, supported by curved glass walls. A widescreen temple to timekeeping, the building is topped by a lusciously grassed winding roof just out of reach from the cows outside.

BIG architect practice's spiral marvel, set into the slopes of Vallée de Joux

BIG architect practice's spiral marvel, set into the slopes of Vallée de Joux

22 Architeliers 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

V.I.PP6

Five years of massively ambitious construction work came to completion at the start of 2020: Patek Philippe’s superyacht-style ‘PP6’, immediately next door to 1996’s building, which the watchmaker had outgrown within eight years. All despite a production of just 66,000 tiny timepieces a year.

Its monochrome Stormtrooper aesthetic stretching 200 metres, the 10 storeys (four of them underground) unite every one of the house’s Genevan manufacturing ateliers – a great advantage given the growing complexity of production operations (final assembly of the parts remains housed over the road). Moreover, PP6 offers ample space for the rare métiers d’art handcrafts being preserved for the future by Patek Philippe, and by the same token, training of employees across the board.

Donning starched-white lab coats and funnelling through the ‘boulevard’ that feeds every employee up and outwards to their respective workspace, what immediately strikes us is the breadth of every corridor. This is because, unlike the industrial MO mentioned above, huge multi-axis CNC milling and turning machines occupy every floor, not just the basement. And they need to be easily moved around.

It’s not all starchitect swagger then – the art of watchmaking itself is being modernised as well as rehoused.

23

Architeliers

Words: Alex Doak

24 Making a Date 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

Switzerland's most historic watchmaker is crafting whole horological calendars – the most exacting and exquisite ones on the planet

A DATE

a Date

25 Making

Words:

Alex Doak Photography: Benjamin Swanson

More than 260 years of uninterrupted production and profit doesn’t happen because of heritage and nostalgia; it comes from constant preparation for your 261st year, then your 262nd, the 263rd… It’s why the salmon-pink masterpiece depicted on the previous page is the perfect embodiment of its maker, Vacheron Constantin, being a calendar perpetuelle

Perpetual, thanks to a 48-toothed cam just behind that gorgeous dial, rotating a full 360º every four years, guaranteeing you never need adjust the date, even on February 29th. (Except on secular, or centurial years – but not those divisible by 400 – thanks to Pope Gregory XIII’s calendar not quite syncing with the Earth’s solar orbit, so do remember to adjust your perpetual calendar on the 1st of March in 2100.)

Then ‘perpetual’ in a second sense, since the seeming anachronism of this watch’s elaborate, over-engineered mechanics belies the “what next?”, “why not?” mindset to get here – regardless of better time (and a slightly more reliable date) kept by your iPhone. Thanks to Vacheron Constantin’s broader-thanmost outlook from 1755 onward, the brand itself has gone the distance; to the point where the 324-part movement inside the Traditionelle Perpetual Calendar Chronograph is considered the finest of its kind, befitting a 43mm case of pure 950 platinum.

The overarching vibe of any Vacheron watch is more Latin – rangy, even – than its handful of contemporaries. Reflecting this classical élan is Jean-Marc Vacheron himself, who in 1755 opened his atelier on an island in Geneva’s arterial Rhône. He was something of a Renaissance man, interested in literature, history and philosophy – plus, in a perfect horological storm, fascinated by the rising potential of micro-mechanics in astronomy, chronometry and connoisseurial grandstanding.

These were passions inherited by his son Abraham and grandson JacquesBarthélemy, ensuring their ornately decorated pocket watches made it into the right hands, throughout the era’s emerging, further-flung markets. Its guiding motto, “Do better if possible and that is always possible," first appeared in a letter François Vacheron wrote to Jacques-Barthélémy Vacheron – the former a hotshot marketeer brought aboard in 1819, the latter proving particularly clever at the helm, going on to navigate the company through some choppy waters. The French Revolution for a start, followed by the Napoleonic Wars, then France’s annexation of Geneva itself. How did the family firm stay afloat, cut off from so many of its elite clients? A temporary diversification into textiles, for one. And cherry brandy.

Such far-sightedness is rare in watchmaking; the fact every major Swiss marque remains voluntarily ringfenced by mountains is metaphor made real. So it probably helps that Vacheron Constantin has always based itself just outside the Jura, down in cosmopolitan Geneva – a hub on the global stage, let alone European. The rather ’80s velvet-lined, walnut-veneered retail experience remains, but flick back a couple of pages and remind yourself of what the Richemont Group’s flagship watchmaker’s actual flagship resembles. A furled spaceship in factory form, poised for lift-off, light years from its anodyne Genevan suburb.

The batteries of million-franc milling machines populating the ground floor of no.10 Chemin du Tourbillon, feeding the hushed floors of finishers, decorators and watchmakers upstairs – the elite artisans bringing things to life – are the latest generation in a technology embraced by VC since the mid-19th-century. Other stoic practitioners of the Swiss craft turned their nose up, but not GeorgesAuguste Leschot, who saw the potential

Post production The Wizard Retouch26 Making a Date 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

27 Making

a Date

Words: Alex Doak

Photography: Benjamin Swanson

28 Making a Date 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

30 Safe Pair of Hands 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

Many a fine watchmaker nurtures a heroic side – whether it be rugged exploration, deep-sea diving or high-altitude manoeuvres on the horizon – but this need never be at the expense of elegance or élan, as our pick of 10 technicolour adventurers from 2022’s horological sweep proves

31 Safe Pair of

Hands

Styling: Ciara Rapple

Photography: John Gribben

Montblanc 1858 Iced Sea diving watch £2,785 Panerai Submersible QuarantaQuattro eSteel Grigio Roccia diving watch £9,700

32 Safe Pair of Hands 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 Oris ProPilot X Calibre 400 aviator chronometer £3,200 IWC Pilot’s Watch Mark XX aviator chronometer £5,050

33

Safe Pair of Hands

Styling: Ciara Rapple

Photography: John Gribben

Rolex Oyster Perpetual Air-King aviator chronometer £6,150 34 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 Safe Pair of Hands

Grand Seiko ‘Hotaka Peaks’

Spring

Drive GMT time-zone watch £5,360 35

Safe Pair of Hands

Styling: Ciara Rapple

Photography: John Gribben

36 Safe Pair of Hands 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 Tudor Ranger tool watch £2,170 TAG Heuer Aquaracer Professional 1000 Superdiver diving watch £5,500

37

Safe Pair of Hands

Styling: Ciara Rapple

Photography: John Gribben

38 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 Safe Pair of Hands

39 Safe

Pair of Hands

Styling: Ciara Rapple

Photography: John Gribben

Hublot Square Bang Unico Titanium chronograph £3,400 Bulgari Aluminium Amerigo Vespucci GMT time-zone watch £3,280

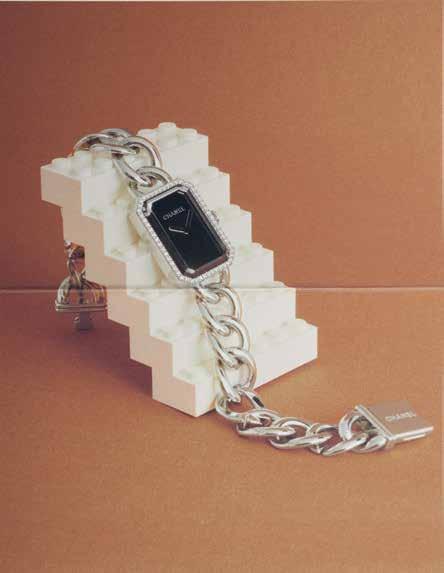

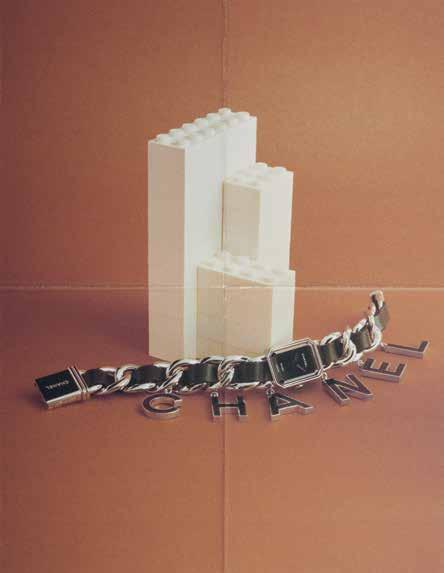

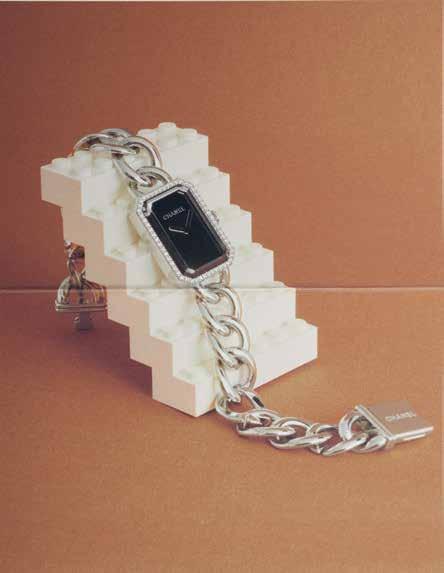

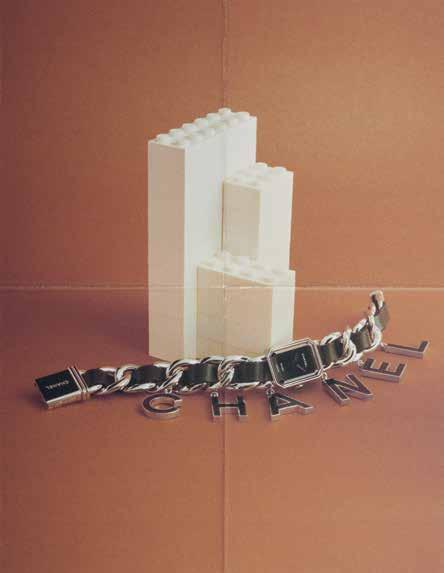

Celebrating the redesign of its fine watch and jewellery division’s Parisian home, Chanel has returned to the cocktail piece that started it all – both named and shaped all too appropriately

40 First Time 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

Creative and set design Serene Khan 41 First

Time

Words: Laura McCreddie-Doak

Photography: Phil Dunlop

‘Première’: the first; the most exclusive; the female director of an atelier.

Chanel’s late, great artistic director Jacques Helleu must have had confidence in his creation, the first-ever watch to bear the maison’s name, in order to choose a moniker with such power.

“I fought to make a design that was strong, that was unique, that – more than just launching a single collection – would become an eternal reference," he said at the time. And it certainly was unique.

It’s easy to forget but back in 1987, women’s watches, as in watches designed specifically for women rather than downsized men’s watches, didn’t really exist. The fashion landscape was also not one into which a timepiece like the Première should have been launched.

This was the 1980s. Ostentation was the name of the fashion game; minimalism meant maybe taking out your shoulder pads. However, the Chanel catwalks tell a slightly different story. In 1983, Karl Lagerfeld joined a business in need of a revamp, having become a brand that, in Lagerfeld’s words, was only worn by “Parisian doctors’ wives”. Charged with updating its look but not to alter its character, he went back to the archives, reviving the use of wool jersey for suits, bringing back the braid-edged suit, but subtly altering its proportions, bringing those recognisable elements of iconograph – the camelia, the double C motif, the chains – into the catwalk, where they hadn’t been before. This was restrained ostentation, “modern and

chic-sexy, not Las Vegas sexy,” as Lagerfeld described it.

By 1987, Lagerfeld was comfortable playing with convention. The Chanel woman was no longer a doctor’s wife, but young, confident and sleekly sexy, as embodied by the new face of Chanel: Inès de la Fressange. This woman didn't want a man’s cast-off, she wanted a watch designed just for her. Just being a timepiece created for women would have been enough to make the Première revolutionary, but everything about this watch was a radical alternative.

There was the octagonal case mirroring both the shape of the Place Vendôme and the top of the Chanel No5 bottle stopper; the decision to use the chain of the famous 2.55 bag as a strap;

Post production Marisa Canelas at Red Yolk Studio42 First Time 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

TICKIN’

1,184 days after 2019ʼs big trade show in Geneva, we returned in April to find that things were in even ruder health, perhaps even because of the pandemic. Given the years-long R&D lead-time on a mechanical wristwatch, maybe Switzerland's watchmakers were feeling as playful, pre-covid, as 2022ʼs burst of joyous cocktail, travel and plain-quirky timepieces imply. We pick five, gloriously overengineered horological creations to fly the flag of fun, at long last

44 Tickin ’ Joy 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

TO JOY

As our Audemars Piguet cover story recounts (see page 50), the early ’70s were particularly challenging for traditional, mechanical watchmakers, with the advent of cheap, battery-powered quartz technology. Not for lack of trying, to give Switzerland its due. A collective effort gave as good as it got, neck and neck with Seiko ’til the last gasp developing the ‘Beta 21’ quartz movement. The clue is in the name, and that writing was on the wall, since corralling 21 competing enterprises more used to tweezing together cogs and levers would always prove a recipe for disaster. Meanwhile, venerable maison Girard-Perregaux took it upon itself to develop at huge cost its own quartz movement, the Calibre 350. In doing so, it singlehandedly established in 1971 the now-world-standard vibrating frequency for quartz crystal regulators: 32.7kHz. Appropriately, the 350's leftfield launch hit ‘Battlestar Galactica’ on the scale of retro-futurist thrust, powering the now-reissued digital beauty you see here: the Casquette. A reminder of how devastatingly cool digital displays – especially push-to-illuminate, Cylonvisor-red LED displays – can be.

DIODE

45

Tickin ’ Joy

Words: Alex Doak

CÔTE D’ALLURE

Baume & Mercier is doing the same as Zenith and Audemars Piguet this year: harking back to its most fabulous and flashy heyday, which will always be the ’70s when it comes to luxury watches, and most everything else interiors and fashion-wise. Created in 1973, just one year after Gérald Genta ripped up the rulebooks with his octagonal Royal Oak design for AP, long-historic B&M went four better with its own 12-sided sports watch in steel, with flowing ‘integrated’ bracelet – named, perfectly, ‘Riviera’. This year’s playful debutante sets its gradated midnight blue lacquer dial with 63 diamonds, which eagle-eyed boulevardiers (who read their atlases 90º anticlockwise) will recognise as the sweeping Côte d’Azur, from Monaco to Saint Tropez. A sparkling call to sundowners on a teak deck. Santé.

46 Tickin ’ Joy 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

MAGICAL METEORS

Given that so-called ‘watchmaker’s watchmaker’ Jaeger-LeCoultre places locked-down, autonomously crafted precision timekeeping at the core of its history and future, a so-called “experiment in randomness” was always going to raise eyebrows. After all, how can anything mechanical and in the business of repetitive reliability manage to throw randomness into the mix? Well, it certainly delivered with the latest complication to join Jaeger’s constellation of gorgeous Rendez-Vous women’s watches: the ‘Dazzling Star’, across whose twinkling, blue aventurine dial shoots a gold star, four to six times an hour. It’s down to sheer luck whether you spot it happening, though. Using the kinetic power supplied by your wrist movement –what keeps every automatic watch wound, via a spinning rotor inside – a secondary rotor is in the constant business of winding the star mechanism up to its critical level of charge and release, which of course depends on how active you are at any one time of day.

47

Tickin ’ Joy

Words: Alex Doak

DISCO TECH

Zenith, finally, seems to have reached its summit. Sporadic product lines and confused brand identity – all despite pioneering the Swiss model of in-house manufacture since 1865, plus inventing the self-wound chronograph in 1969 – have yielded to unmatchable demand from well-heeled aesthetes seeking connoisseur bragging rights in combination with designer brio. Cannily, under zippy new CEO Julien Tornare, Zenith has doubled down on aforementioned automatic chronograph tech, the ‘El Primero’. And had fun with it. Even ramping-up its high-frequency ticktock from 10Hz to 100Hz with a secondary regulator whipping the seconds hand around the dial once a second, allowing timing to a hundredth of a second. This latest version of the DEFY 21, ‘Chroma’ is Saturday Night Fever in watch form, in keeping with El Primero’s prime era: a ‘flare’ of white ceramic for the case, picked out with ‘grooved’ markers in all the colours of the rainbow.

INSPECTOR DECK

Do not adjust your specs. This from micro-tech disruptor Ulysse Nardin is an extraordinarily abstract, breathtakingly executed totem of horology itself; a reminder of where the mechanics ticking inside your entry-level Rolex originate. In other words, an exploded, sci-fi take on a deck clock: historically kept level on gimbals in the captain’s cabin, keeping precise ‘home time’ to determine one’s longitude at sea. Exactly 175 years back, Ulysse Nardin’s prize-winning marine chronometers were in the business of keeping 45 admiralties on course, but the Swiss brand was never going to wallow in nostalgia. “We wondered what a marine chronometer designed in 2196 would be like,” said Patrick Pruniaux, CEO. Sure enough, the ‘UFO’ lives up to its name, as well as the brand’s historic repute, with a ‘listing’ (i.e. always upright, as if on gimbals) hemispherical base, tripledial time zones and an aesthetic with as much of an eye on the stars as the sea.

48 Tickin ’ Joy 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

49

Tickin' Joy Words: Alex Doak

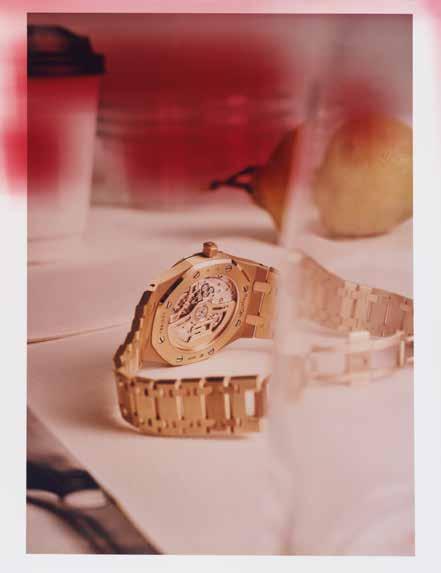

Fifty

RICH

TAPESTRY

years on, the mighty Royal Oak’s woven dial and octagon form are still utterly up-to-the-minute 50 10:10 Magazine Rich Tapestry Issue 7

51

Photography: Leandro Farina

Rich Tapestry

Words: Alex Doak

Apparently, it was the decade that style forgot. But clearly the watchmakers dotting the valleys of the Swiss Jura –where, if not in Geneva, you’ll find the world’s finest –missed that memo.

The ’70s was a challenging decade on many fronts, from fuel crises to equally challenging plaid shirts. Those in the business of mechanical timekeeping can be added to that list too, given the devastating toll of 60,000 jobs and 1,300 companies by 1980, entirely at the hands of East Asian quartz technology –first looming onto wrists in 1969 in the guise of Seiko’s Astron (hardly cheap from the outset, launch-price famously matching that of a Toyota Corolla, but swiftly industrialised to cereal-packet freebie status).

Just as the ’60s ran from 1964 into 1972 or thereabouts, the ’70s watchmaking revolution started in 1969. Only, it was a revolution with many faces, both technical and design wise. For a start, before quartz had even got its hooks in, 1969 witnessed the three-

pronged birth of a long-gestated form of mechanical wristwatch: the selfwinding chronograph. Three of them from Breitling, Heuer and Zenith, in a single year.

So how, to the backdrop of quartz ruination, global economic crises fuelled (or not, as the case may be) by oil shortages, as well as tanked-out R&D departments, did the ’70s see such an exuberance of creativity? Not only that, but lasting creations, far more resilient than the fickle increase of flares we’re seeing in high-street windows this season.

If nothing else, we’re talking about Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak of course, whose 50th anniversary is being marked this year with admirable reserve: a hen’steeth clutch of period-correct, if novel colourways, given away by the stencilledout “50” in the gold winding rotor, which you can watch spinning through the sapphire caseback.

It was penned by original horological disruptor Gérald Genta (now regarded as

watchmaking’s Andy Warhol) in response to AP’s sudden request for a sporty but luxurious number that would appeal to the era’s young, Italian, well-to-do Riviera gadabouts. It cemented Genta as a chalethold name and evolved into his other two enduring masterpieces for Patek Philippe (the Nautilus) and IWC (the Ingenieur).

The mighty Oak was named after an old Royal Naval boat whose octagonal portholes inspired a circumferential bezel and its eight exposed screws. An ‘integrated’ steel bracelet flows in seamlessly – but so tricksy was it to machine and finish with alternating polish and brushed facets that it was prototyped in gold, then advertised, literally, as “the costliest stainless steel watch in the world”.

Were it not for Audemars Piguet’s blue-blooded pedigree – still the only Swiss behemoth that remains in the hands of its founding family – the Royal Oak might have eaten itself, with a profligacy and stratification worthy of a brand in its own right.

Creative and set design Serene Khan52 Rich Tapestry 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

The pumped-up ’90s ‘Offshore’ phenomenon singlehandedly coined the oversize ‘It’ watch, as mediated by Arnie et al.; then the sci-fi ‘Concept’ series formed an eight sided crucible for AP’s skunkworks, Renaud & Papi and their horological alchemy. You wouldn’t have Richard Mille, MB&F or anything with an open-dial flea circus for a movement, otherwise.

The new, golden-anniversary Royal Oaks – in admirably restrained, faithful fashion, stoking the feverish wont of collectors and flippers – leans back on one of its oft-overlooked aesthetic motifs: the guilloché-etched ‘Tapisserie’ dial.

Most of the 2022 Royal Oak novelties in 34, 37, 38 and 41 mm are endowed with a ‘Grande Tapisserie’ pattern achieved through a complex manufacturing process based on a rare know-how no longer taught in horology school: a ‘pantograph’ machine whose ‘finger’ runs across a manhole-scale template of Genta’s cross-hatched relief pattern, feeding the movement back to an etching

tool via a series of precisely ratio-ed gears.

For every watch, a matrix of hundreds of small, truncated pyramids with square bases are carved out on the dial’s thin metal plate by a battery of these antique ‘guilloché’ copying machines, chattering away in a darkened workshop at Audemars Piguet’s remote Le Brassus factory.

It’s not all rheumy-eyed nostalgia, though. The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak ‘Jumbo’ tribute (it says everything of watch sizes now that 39mm seemed ‘jumbo’ in 1972) may be faithful outwardly but this year sees the wholesale replacement of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s ultrathin calibre 2120 of 1967 with an all-new, future-proof and powered-up movement, calibre 7121.

Five years in gestation, 7121 is selfwound by the only gimmicky nod to the Royal’s Oak’s milestone birthday: a rotor skeletonised into 2022’s ‘50 years’ logo. The 2120 remains the thinnest-ever automatic movement with full-width rotor at 3.05 mm high, invented by Jaeger-

LeCoultre in 1967 and supplied whitelabel ever-since, to the great and the good of Geneva and the Vallée de Joux, AP’s bucolic, high-altitude nest since.

Measuring just 3.2 mm in thickness, the new 7121 isn’t out for Slimmer’s World bragging rights; it’s been specifically conceived in AP’s mountain eyrie to fit the 8.1mm Jumbo case without altering its aesthetic and thickness.

Furthermore, the driving stem is now endowed with a rapid date-corrector, the balance wheel ticks robustly from beneath a dual-anchored bridge rather than a ‘cock’ – gleaming in parallel with the handfinished bridges – plus a bigger spring barrel means that power’s up to 55 hours.

Those 39 or 41-millimetre diameters may not be ‘jumbo’ anymore by watchmaking’s modern standards, but its bulletproof design coherence means the Royal Oak Extra-Thin will surely reign for many more half-centuries to come. Forget about investment value, this is what fine watchmaking is all about: legacy in integrity.

53

Rich Tapestry

Words: Alex Doak

Photography: Leandro Farina

Pandemics, athleisure and nomadic desk space have all relaxed men’s formal attire to the point of horizontal. But with every revolution comes a backlash and, sure enough, a leather-soled, sartorial élan is creeping in again, on wrists as well as heels

54 Dress Code 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

55

Dress Code Words: Alex Doak

Photography: Baker & Evans

56 Dress Code 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

Previous page: Audemars Piguet Code 11.59 Selfwinding Chronograph

Launched in 2019, Code 11.59 was a long-awaited contemporary evolution of a classic round watch, from a storied maison many feared had become overshadowed by a singular, decidedly non-circular cash cow (see our feature on the Royal Oak’s big five-oh, if in doubt). It seemed like a compromise at first, given the tension of round upper and lower, sandwiching a case-middle of Royal Oak octagonality. Vapours now dispersed, the sense and long-termed intentions are now crystallising; viz. double curved sapphire crystal, in combination with AP’s historic complications: tense, arched profile playing with depth, perspective and light for a unique optic experience. £46,500

Patek Philippe Ref. 5905R

“Never brown in town,” they say –an adage clearly lost on Patek Philippe’s current generation of designers, given this sumptuously chocolate-toned update of its flyback chronograph in combination with annual calendar, which only need be adjusted on March 1st. A gleaming rose-gold case frames a brown sunburst dial, gradated to black where it meets the bezel – an aesthetic cleanliness that might have been compromised by conventional chronograph counters, on top of day, date and month windows, were it not for Patek’s ingeniously hybridised hours/ minutes subdial at 6 o’clock.

Of course we’ve included a Cartier. Just as ‘Rolex’ is a synonym for ‘aspirational sports watch’, Cartier is your default, blue-blooded dress option. It has been since the turn of the century, practically inventing the practical notion of a wristwatch, over the onerously pocket-born timepiece. The serial-produced ‘Santos’ of 1911 took its flamboyant, Brazilian aviator namesake’s request to Louis Cartier for a hands-free cockpit timekeeper, then flew with it. It’s still inspired by both friends’ home city of Paris’s nouveau stylings, yet now proportioned contemporarily and adorned (in this case) with PVD-coated go-faster striations that Señor Alberto would certainly approve of.

Cartier Santos de Cartier

57

Dress Code

Words: Alex Doak

Photography: Baker & Evans

Omega De Ville Trésor

The Trésor line was first launched by Omega in 1949, and all those restrained, classical lines feel as effortless as ever –a tough design brief to pull off when all you have is a circle and three hands to work with. What’s even harder is legitimately combining such traditional heritage with one of today’s most advanced mechanical movements.

8910 not only resists MRI-scanner levels of magnetism, while maintaining chronometric precision, but service intervals are relatively glacial thanks to a lubrication-free ‘Co-Axial’ escapement ticking at the heart of things.

Calibre

£6,100 58 Dress Code 10:10 Magazine Issue 7

NOMOS Glashütte Tetra neomatik

Two years back, the tiny but tough village of Glashütte celebrated the 175th anniversary of its recovery and renewal as Germany’s hub of fine watchmaking – when Adolf Lange officially set up his workshop and began recruiting out-ofwork miners at the behest of Saxony’s government. It’s Nomos who remain the most disruptive and representative, arguably, basing their main factory within the old railway station, over the road from more reminiscent concerns, pushing things forward on the affordably mechanical front, but also design-wise, thanks to its ice-cool Bauhaus design DNA. Saluting the 175th, this piece is enamel-glossed in an off-white shade, because… Nomos chose to.

£3,060

Piaget Polo Date

The horological king of ultra-thin applies its in-house Calibre 1110P movement to one of the most – if not the most – elegant sports watches on the luxury scene. ‘Polo’ by name, polo by nature, this squared-circle update of the ’80s jetset’s must-have is like a fresh pony for a new chukka: substantial on the face of things, but deceptively lithe and relentless, thanks to 1110P’s 4mm slenderness and its super-efficient winding rotor spinning flush atop.

£9,400

59

Dress Code

Words: Alex Doak

Photography: Baker & Evans

Jaeger-LeCoultre Master Control Calendar

The sleek lines of J-LC’s Master Control collection draws from the classic designs of the golden age of watchmaking –in a word, the ’50s. Pop may not have yet exploded, but the well-to-do were well ahead of their young in post-war exuberance. Echoing the colour of the calfskin strap, the dial’s shimmering contour of royal-blue shades are all the more captivating in the evening, when the dots of the minute track and Dauphine hands glow luminescently in the night. Enough to make you forget about the autonomously crafted complexities ticking beneath.

£12,400 60 10:10 Magazine Dress Code Issue 7

Vacheron Constantin Patrimony Retrograde Day-Date

This exquisite, entirely original conceit of date display combines a ‘retrograde’ or fly-back ‘pointer’ day display, as well as date. Both of these hands as well as the hours hand are gently contoured to follow the shallow camber of the dial. The applied gold hour markers and minutes hand are curved too, slipping between the mere onemillimetre void between dial and sapphire crystal dome. This delicate 3D jigsaw is entirely hand formed and adjusted, making an otherwise tricky operation – dial making being second only to watchmaking itself in complexity – particularly painstaking. Visually imperceptible, almost, but subliminally sublime.

£39,300 61 Dress Code Words:

Alex Doak

Photography:

Baker

& Evans

Chopard L.U.C

The hours and minutes hands of Chopard’s purest ‘tuxedo’ watch seem to echo the architectural silhouettes of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, but like the aforementioned Omega Trésor, the texture of this dial is like the virgin wool of its strap: a nod to the gentlemanly codes of Savile Row and its tailors. It’s a navy cashmere flannel suit in wristwatch form, but certainly not style over substance; for over 20 years, Chopard’s co-president Karl Friedrich-Scheufele has nurtured his ambitious vision for reviving Louis-Ulysse Chopard’s enterprise, and something as pure and simple as this creation is all the validation he needs.

£7,720

Chanel J12 Wanted de Chanel

Twenty years after its creation at the hands of Jacques Helleu, Arnaud Chastaingt, director of the Chanel Watch Creation Studio, gave the J12 a makeover while managing to not undermine what made this such a phenomenon in the first place: a fashion watch with horological clout that also brought something to the table. In 2019, almost nonchalantly, ceramic cases and bracelets were tabled for fashion’s sake (resemblance to quilted handbags not entirely coincidental) and now we have high-level precision mechanics thanks to Chanel’s characteristically canny investment in Kenissi Manufacture, alongside Tudor – Rolex's blossoming sister brand. For once, the shameless sloganeering can be justified here.

XP

£6,700 Post production Sam Stuller at Stilletto 62 10:10 Magazine Dress Code Issue 7

63

Dress Code Words: Alex Doak

Photography: Baker & Evans

CAMERA OBSCURA

Twenty-one years on, Amelie (2001) retains all its power to charm and inspire selfreflection in its whimsical depiction of a loner in Paris, secretly spreading joy among her fellow Montmartre misfits. One being the elderly Monsieur Dufayel, whose annual quest to replicate Renoir’s masterpiece ‘Luncheon of the Boating Party’ (1881) remains frustrated by his inability to capture a female outsider within his painting. Meanwhile, his clocks are kept silenced by his video camera, filming a jeweller’s shopfront clock keeping time on an outside world from which his brittle bones keep him separate.

M. Dufayel: Je vois que vous regardez ma caméra à la fenêtre. C'est un cadeau de ma belle-soeur. Oh, je l'ai mis là, comme ça, plus besoin de remonter mes pendules. [returning to his easel] Après toutes ces années, le seul personnage que j'ai du mal à cerner, c'est la fille au verre d'eau. Elle est au centre et pourtant, en dehors.

Amélie: Elle est peut-être seulement différente des autres.

M. Dufayel: Et en quoi?

Amélie: Je sais pas.

M. Dufayel: Petite, elle ne devait pas jouer souvent avec les autres enfants. Peut-être même jamais.

M. D: Ah, you’ve noticed my video camera at the window. It’s a gift from my sister-in-law. I put it there so I don’t need to wind my clocks… After all these years, the only person I still can’t capture is the girl with the glass of water. She’s in the middle, yet she’s on the outside.

A: Maybe she’s just different from the others.

M. D: In what way?

A: I don’t know.

M. D: When she was little, she can’t have played much with other children. Maybe never.

64 10:10 Magazine Issue 7 Camera Obscura

Anti-magnetic. 5-day power reserve. 10-year warranty.

The new ProPilot X is powered by Oris Calibre 400.

Play & Win

BIG architect practice's spiral marvel, set into the slopes of Vallée de Joux

BIG architect practice's spiral marvel, set into the slopes of Vallée de Joux