HOUR MINUTE SECOND

The in nitessimal precision of ne watchmaking's many cra s

Panerai proves there's always another chance for a legend

HOUR MINUTE SECOND

The in nitessimal precision of ne watchmaking's many cra s

Panerai proves there's always another chance for a legend

Last time it was ‘innovation’. This spring, we’ve tentatively themed our special edition of 10:10 ‘endeavour’ – zeroing in on the sheer e ort demanded by ne watchmaking of its protagonists –anachronism, folly or otherwise.

But as we’ll probably concede come autumn – hopefully the following spring, too – 10:10’s common denominator may as well remain ‘humans’, plain and simple. Because humanity has always depended on horology to mete-out the seasons themselves (calendars came before clocks), as well as navigate to new climes (no chronometer, no longitude), and generally sing from the same global hymn sheet (1884’s 24-time-zone carve-up in other words, the establishment of GMT, intercontinental trains not crashing, transatlantic phone calls… the future!).

Editor-In-Chief

Dan Crowe

Creative Director

Astrid Stavro

Design

Astrid Stavro

Daniel Shannon

Editor

Alex Doak

Accessories Editor

Serene Khan

Senior Editor

Kerry Crowe

Sub-Editor

Sarah Kathryn Cleaver

Photography

Ivona Chrzastek

Nicholas Polli Baker & Evans

Cover Photography

Louis Vuitton

by Ivona ChrzastekSet Design

by Lucy BlofeldArt

Direction by Serene Khan Panerai by Nicolas PolliEditor's Letter Illustration

Alan Kitching

Publishers

Dan Crowe

Matt Willey

Associate Publisher

Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono

Advertising Director

Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono andrew@port-magazine.com

Typefaces

A2 Record Gothic

by A2-Type (A2/SW/HK)

Quadraat Pro by Type By

Pitchby

Contact

Every modern human endeavour has demanded machinery of ever-more-excruciating precision. If you thought the Y2K bug x was a worry, imagine how GPS operators feel every time astrophysicists sporadically add a ‘leap second’ to the world’s atomic clock whenever there’s a wobble in the Earth’s magma core, nudging our sight on humanity’s ultimate clock, the heavens.

So, it comes as a surprise that the old adage, “you can put a man on the moon, but [insert quotidian drawback here]” now relates to actually putting man on the moon. Again.

Billionaire space entrepreneurs, the ESA, NASA, they’re all shooting for the moon over 50 years since Armstrong made his giant leap. And, just like America’s 19th-century railroads, they need to agree on a common ‘Lunar standard time’ before their respective navigational satellites come a little too close for comfort.

The moon doesn’t spin – a lunar ‘day’ is an Earthbound lunar ‘month’, or 29.5 days – so a cycle that chimes with human circadian rhythms will help. Only, NASA engineers are now having to address a stickier issue they’ve known about since 1972’s technical note published in the wake of relativistic time corrections aboard the Apollo 12 and 13 missions: time moves di erently on the Moon. Thanks to gravity or lack thereof, a clock on the Moon gains around 56 millionths of a second per day compared to a terrestrial equivalent, and that rate changes based on whether the clock is in orbit or on the Moon's surface. It's not much, but with humanity hell-bent on a new ‘lunar gateway’, those millionths of a second will add up.

Klim Type FoundryPort Magazine

Somerset House

London, WC2R 1LA

+44 (0)20 3119 3077

port-magazine.com

Alex DoakTime will tell, and humans will always need to tell the time, regardless of the endeavour.

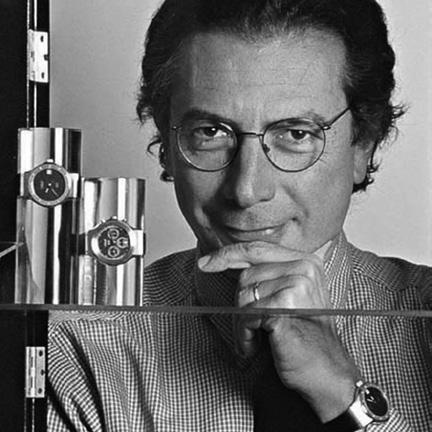

If ever there was a man who put humanity into horology, it's Svend Andersen. Where before, there were Switzerland’s go-to brands and our quotidian need to know the time, it was a er the ‘70s so-called ‘quartz crisis’ that traditional watchmaking had to reinvent itself as a curio; a luxury with legacy, its hands of time (plus dial, mechanics, et cetera) wrought by actual hands over a very long time.

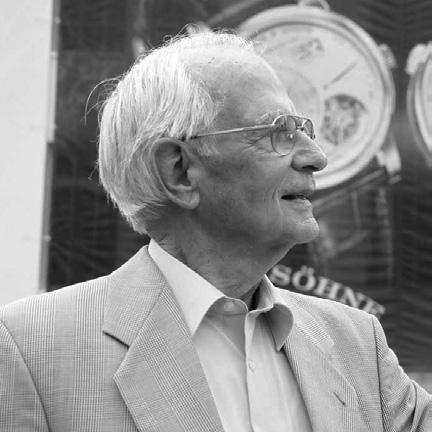

Mr Andersen, who kindly provides the Foreword for our ‘endeavour’ edition of 10:10, recognised this in the ’80s. A Danish-born Swiss master who cut his teeth in Patek Philippe’s complications ateliers, he mentored the man whose own enterprise was to become the original ‘it watch’ of the ’90s, Franck Muller. Moreover, he co-founded the Académie Horlogère Des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI) with Vincent Calabrese in 1985, declaring that, “here, you can touch the watchmaker who makes your watch.” The AHCI now boasts a roster of 33 horological rockstars, including ‘master of nish’ Philippe Dufour and purist’s purist François-Paul Journe. Svend Andersen continues to make his masterpieces under the banner ANDERSEN Genève in the titular Swiss city and holds the Guinness world record for smallest calendar watch ever made. Other notable creations include Heures du Monde, which tells the time in any of the 24 time-zones, as well as his ‘erotic’ automata.

This edition of Port’s 10:10 imprint is about ‘endeavour’ – the wilful anachronism that is the mechanical timepiece and the sheer human e ort that goes into creating it.

A er nine years cutting my teeth at Patek Philippe (literally, when it came to pro le-turning a brass wheel!) my own ‘endeavour’ came when I went solo in 1969. I made the ‘Bottle Clock’ and was nicknamed ‘the watchmaker of the impossible’. Since then, collectors have asked me, “can you do this or that?” At the end of the 1970s, I had a request to reconstruct and manufacture a gold case for an overly complicated pocket watch movement. Yes, I could, and I did!

Following the delivery, I received so many orders that I could start independently with casemaker William Perret in 1980, restoring old but highquality movements, o en with added ‘complications’ (functions additional to the time), whose gold cases had been melted down during the quartz crisis.

Once I was told, “you have a nose for discovering talents,” and my feeling about a promising young watchmaker named Franck Muller was good. Therefore, I could accept a request from Patek Philippe to restore watches from their collection

(watches that are today displayed in the Patek Philippe Museum). Why? Because Mr. Banbery and Mr. Huber were writing the brand’s catalogue raisonné and they needed pictures. Of course, Photoshop did not exist at that time, so the watches needed to be in top condition.

Restoring antique timepieces is to receive hands-on tutorage from the past’s masters, and Franck duly progressed to great things under his own name, almost singlehandedly re-establishing haute horlogerie as an innovative thing, as well as a fashionable thing.

Nowadays, the mechanical watch is not needed to indicate the exact time. Countless brands have whirring ‘tourbillons’ displayed through the dial, plus di cult-to-read indications, but no matter; the watch is now considered a status symbol. For the future, my crystal ball says that this will last.

The horological world continues to change, with digital technology and CNC manufacturing, while I, for one, continue with basic lathes and milling machines,

ideal for unique items and prototyping. Which isn’t to say I’m resistant to progress. Every cra sman has their own unique endeavour, which demands a di erent skillset every time.

At the beginning of the AHCI in 1985, I discovered some of the most notable members, such as Christiaan van der Klaauw, Matthias Naeschke or Kiu Tai You. Today, they rub shoulders with Konstantin Chaykin, Miki Eleta, Hajime Asaoka… a younger generation still de ning their talents, which is so gratifying and exciting. Plus – as you’ll glean from the names alone – not necessarily Swiss at all!

In fact, my horological hero will always be the Isle of Man and formerly London’s Dr George Daniels (1926-2011), because of his all-embracing knowledge and culture – and ultimately the fact his one-man, self-taught enterprise sparked the latterday notion of the ‘named’, independent watchmaker. In command of most of the 34 cra s required to make a watch from the raw metal – or all 34, in George’s case!

Ultimately, François-Paul Journe’s

slogan – the hallmark that every historic marque bore – is what any self-respecting watchmaker should strive for: ‘Invenit et Fecit’. ‘Invented and made’.

Sounds simple, doesn’t it?

Four new manoeuvres at the hands of watchmaking’s vanguard: a 1,100-part masterpiece, go-faster circles from a grandmaster, Bauhaus meets ghter jets, and your name engraved in Jazz Age perpetuity

An hour’s ear-popping drive north of Geneva takes you up into the Elysian heartland of ‘complicated’ haute horlogerie: the Vallée de Joux, aka the Silicon Valley of 19th-century Swiss watchmaking. It’s where, to the gentle soundtrack of cow bells, the world’s most tricky added extras in micro-mechanical form have been jigsawed together in singular watch form. Chiming ‘minute repeaters’ (sonorous to the minute, on demand), always-accurate ‘perpetual calendars’ (even on February 29th), duallaptime ‘split-seconds chronographs’, gravity-defying ‘tourbillons’… All impressive-enough feats of engineering and dexterity on their own. But together, in mindboggling ‘grande complication’ guise? Consider the Vallée de Joux your four-stop shop: Jaeger-LeCoultre, Blancpain, Breguet, then the daddy of them all: Audemars Piguet, still based in the Cupertino of its day, Le Brassus. AP is mostly in the business of celebrating the 30th anniversary of its

beefcake Royal Oak O shore sports watch in 2023, but the year kicked o with a searing reminder of its clout among a handful of historic Swiss brands, who can rightly claim a seat at the table named grande maisons. “Interweaving extreme complexity with simplicity of use”, in the words of AP’s Heritage and Museum Director, Sébastian Vivas, the Audemars Piguet’s Code 11.59 Ultra-Complication Universelle RD#4 pays tribute to 1899’s decidedly snappier L’Universelle pocket watch of 1899.

For a full seven years, Le Brassus’ nest minds have worked hand-in-hand to bring to life their RD#4. A full 1,100 components, 40 functions, including 23 complications. Even if you do happen to be a stickler that takes issue with the in-passing sonnerie’s ‘silence’ mode counted among said 23, along with ‘automatic winding’ (you’d hope it was powered from somewhere), no one can deny what a phenomenal achievement this is.

And it isn’t just a Joux revival boxed-up

in AP’s slow-growing new 11.59 architecture; it adds simpli cation to the hypercomplication, reducing the typical panoply of bristling buttons to just three crowns and three push-pieces – including the ‘supercrown’ at four o’clock, combining yback chronograph zero-resetting with forward or backward correction of the month.

Yes, at $1.2m, it is a plaything for the 0.1%. But see it instead as a crucible for centuries of heritage, and security for so many skills in centuries to come.

Its roots may thread the turf of Jaipur’s polo pitches, ever since the British Raj’s heyday, but the Jaeger-Lecoultre Reverso has galloped far beyond the original request from o cer players to be able to ‘reverse’ the delicate dial glass away from ailing mallets. The Reverso, in all its streamlined, rectangular, golden-ratioed perfection become an art deco icon. From 1931 to today, still as crisp as a freshly mixed Manhattan.

Which brings us to the Jazz Age capital itself, and the latest in Jaeger-LeCoultre’s series of collabs with creative spanning myriad disciplines outside watchmaking. Dubbed ‘Made of Makers’, it already counts consultations with the Institute of Planetology and Astrophysics in Grenoble in realising an astronomical timepiece with almost-unnecessary commitment to celestial observation.

A native of Barcelona and alumnus of

Catalonia’s esteemed Elisava school, based in New York for the past decade, Alex Trochut is JLC’s latest hook-up. And he’s bringing more deco to the Reverso than even the watchmaker could have thought possible. In short: a new, complete and boldly contemporary typeset, ‘1931 Alphabet’, is now an option when you personalise your new Reverso’s caseback engraving via JLC’s website.

Trochut attributes his special connection with typography to his grandfather Joan Trochut, who invented a revolutionary modular typographic and ornament system in the 1940s – recognised as a major contributor to the history of typography as a result.

Great Gatsby it may be in spades, but on the Reverso it is utterly, joyfully justi ed.

In 1987, French interior-architectturned-watch-designer Alain Silberstein unveiled his colourful, childlike Krono Bauhaus. Kandinsky, Miró and Ettore Sottsass’s abstract Memphis movement in miniature, wrist-worn form. To that list of modernism, M Silberstein can now add cubism, thanks to the strippedback utility of fellow Frenchmen, Bruno ‘Bell’ Belamich and Carlos ‘Ross’ Rosillo. Their Swiss-made watch brand has, since the ’90s, equipped bomb disposal squads, SWAT teams, naval air arms and deep-sea divers. But it speaks volumes of Bell & Ross’s design-forward nous that a watch inspired by – and intended to complement – any pilot’s squared-up cockpit instrument array can translate so e ortlessly to the whimsical primaries and playful geometries of Silberstein.

The latest from Revolution watch magazine’s publisher, Wei Koh and his collaborative ‘Grail Watch’ project, the Bell & Ross x Alain Silberstein BR 03-92 Klub 22 (£3,700) is pure jet ghter, outwardly, in matte-black ceramic case and jet-black dial.

“It was Bruno’s idea to take the very essence of each of our design languages and pare it down to its barest elements,” says the designer. “The purity of the black case and dial serves as a canvas for the primary colours of my hands.”

In ‘3,6,9’ array, the subdials of Rolex’s 6239 Daytona provoked immediate comparisons in 1963 to China’s premier bamboo gourmand: two black eyes and a mouth, staring out of a white face, doubling-up as 12-hour, 30-minute and 60-second counters. Meant prosaically as an aid to harried racing drivers needing sharper visibility, it was a joyful advance in chronograph (AKA stopwatch) dial design that caught on for design’s sake as well as cockpit practicality, from Heuer to Longines to Breitling. All the oilyragged, mid-century kings of high-speed horology, in other words.

So why on earth should Switzerland’s venerable Vacheron Constantin feel the need to pander to the panda? Surely, over 260 years tending to the nicky foibles and nesse of classical horology excuses you from the trend-led rat race? Truth is, VC’s veritable greyhound of 2023 – out of the traps’ months before the urry of newness that is Watches & Wonders in Geneva in March – was not only an irrefutable,

square-jawed hunk, regardless of dusty heritage, but it stems from a lineage that last year’s anniversary reminded us of.

The 222 of 1977 was Vacheron Constantin’s ironic riposte to the ’70s urry of (in themselves ironic) luxury sports watches in steel with steel bracelets. Still sporty, but still de antly all-yellowgold, the 222 was as rakish as Bond skiing in a tuxedo.

Rebooted and renamed ‘Overseas’ in 1996 as a collection in its own right, the crenelated, six-sided bezel tightened Jorg Hysek’s original ‘gnurled’ circumference, while cleverly referencing the brand’s Maltese Cross motif – the shape of the 12-month cam in a calendar mechanism. It’s just as aesthetically distinctive as Gérald Genta’s slavishly aped, octagonal triptych of Royal Oak (Audemars Piguet, 1972), Nautilus (Patek Philippe, 1976) and Ingenieur SL (IWC, 1976), but in 2023 with monochromatic, go-faster dots, the Vacheron Constantin Overseas Chronograph Panda feels like an icy blast of refreshment, with pedigree.

Bell & Ross × Alain Silberstein BR 03-92 KLUB 22

Bell & Ross × Alain Silberstein BR 03-92 KLUB 22

When watch brands start trading bragging rights, the old 200mph supercar argument kicks in: “yeah, but he’ll never actually take his diving watch down to 200 metres, will he?” That may be, but these watches certainly can, and unlike your average King’s Road Ferrari, they are relied upon to perform with surprising regularity, to every end of the Earth

"The most formidable challenges are only solved through visionary leadership... Environmental degradation is among the most critical challenges imaginable." Jean-Marc Pontroué,

Panerai CEO,

2021

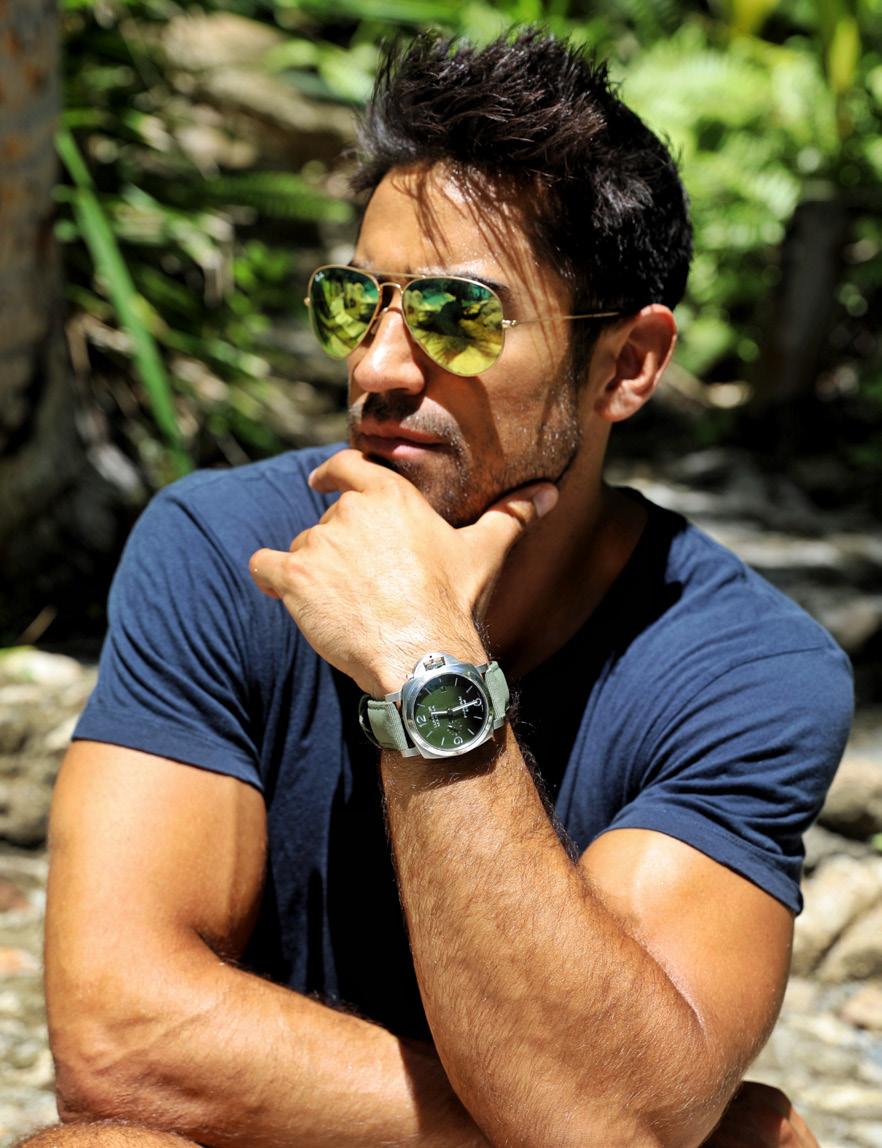

Back in the noughties, if you had the biceps to match (as well as the cash) then you probably had a Panerai clamped to your wrist. The commercialisation of the Italian navy’s steroidal diving watch by Vendôme Group and its endorsement by Sly Stallone et al. has become the very folklore of modern ‘it watch’ hype and hubris.

As was the case back then, we’re now witnessing another example of how things have moved on. Panerai is still a status choice, by dint of its creations’ he , and the derring-do of Italy’s subaqua saboteurs during WWII still as visceral. But manufacture is now 100% Swiss and 100% in-house – more than the incursori would ever need to time their limpet mines. Moreover, the expeditions a Panerai nds itself accompanying these days are resolutely peaceful.

Mike Horn’s Arctic, circumnavigational and pole-to-pole endeavours for one, revealing our planet’s fragility the hard way. And then, one Jeremy Jauncey, a multi-million-follower in uencer using his in uence for good.

The words ‘internationally recognised entrepreneur, investor, and business advisor’ might smart among longertoothed activists, but they comprise the top line of CVs that make a genuine di erence today. Engagement socially, then engagement industrially: a connect that’s been thus far a disconnect.

As founder of Beautiful Destinations, a strategic agency for travel businesses, Jauncey has become one of the most compelling voices in his industry, now leveraging a hook-up with Panerai to bolster the impact of his own, metaversal shop window. He’s a tireless champion of travel as a force for good for both travellers and the destinations they visit, rather than pursuing the impossible notion of a static humanity. Since sustainability and conservation are inseparable from

responsible travel, Jauncey has also earned ambassadorial roles with the World Wildlife Fund and GoldStandard.org.

Whether timely enough, we can’t know yet. But at least the timekeepers themselves are getting out there, on the right wrists.

“During a dive, one of these watches was lost at a depth of 53 metres. We found it 24 hours later … still running smoothly." Lt. Claude Ri aud, Commander of the Hubert Commando, 1955

Long before the ‘desk diver’ became forgivable boardroom attire, the Blancpain Fi y Fathoms sprang from real-world, lifesaving necessity. 70 years on, the fact it's still aiding as many PADI quali cations as approving looks from the boss cements the cult and clout of Switzerland's rst modern diving watch.

Purpose-built to thrive underwater, as opposed to reluctantly surviving in it, the Fi y Fathoms came along in 1953 when Blancpain unveiled a concoction of utilitarian features in one model, pipping Rolex's Submariner to the post by a single year.

CEO Jean-Jacques Fiechter was keen on the era's new ‘SCUBA’ – like so much emergent technology of the ’50s, honed fast by the pressures of war. Having had one too many hairy moments misjudging the oxygen le in his tank, all it took was a knock at the door from decorated founders of the French Navy’s ‘Nageurs de Combat’, Captain Robert “Bob” Maloubier and Lieutenant Claude Ri aud. Far from hobbying weekenders meandering the shallows of the Côte d’Azur, as was

Monsieur Fiechter’s persuasion, these black-ops frogmen were looking for a watch that could keep up behind enemy lines.

“The water resistance that we have tested to 100 metres is perfect,” Ri aud wrote to Blancpain’s distributors, of the early prototypes, “the operation is excellent, and the luminosity matches requirements."

This year's 70th-anniversay, hightech evolution keeps the Fi y Fathoms' de ning attributes intact, of course: luminous numerals, O-ring rubber seals, plus the headline innovation of 1953, the now universally adopted calibrated bezel allowing dive-time measurements according to your minutes hand – later upgraded as ‘uni-directional’; simply put, a bezel that can only be knocked anticlockwise as you brush past an outcrop, so only less oxygen can appear to be in the tank, rather than (fatally) more.

Committed to corporate social responsibility in ocean conservancy, let alone working hand-in-hand with its protagonists, for 10 years Blancpain has supported the work of diver, photographer and underwater biologist Laurent Ballesta. His ‘Gombessa’ expeditions' research involves long-duration deep dives in French Polynesia (hammerhead sharks) and the Indian Ocean (the coelacanth, a prehistoric sh once thought to be extinct for 70 million years). Ballesta’s extreme divers now bene t from a new Fi y Fathoms in titanium, the Tech Gombessa whose bezel times a dive up to three hours rather than one, by introducing a second minutes hand ticking three times slower.

Jeremy Jauncey, Panerai ambassador and corporate force for good in green initiatives, with a persuasion towards a 'Submersible'

It’s a wonder no one thought of it rst. But the simplest ideas seldom arise without hands-on, heads- rst experience.

“This is for the whole climbing community. If the younger generation and the Nepal climbing community see these achievements being done, it shows it can be done.” Nimsdai ‘Nims’ Purja, 2022

Mountains are literally at the heart of Germany’s Montblanc – the Rolex of penmaking, if you like, with Dunhill levels of sartorial accessorisation besides –taking its name from Switzerland’s famed Alpine peak, and capping every pen with a snowy-white summit. The newatchmaking side of Montblanc could only ever be Swiss, therefore.

By the same token, its watches couldn’t not go mountaineering eventually. With all horological nous duly mastered, then, Montblanc is exacting on nothing less than every alpinist’s ‘black belt’.

Climbing to 8,000 metres above sea level without supplemental oxygen is an exploit in itself, requiring great preparation, physical condition, technique, experience, and mental strength. When there is less oxygen in the air than in the blood and brain, serious health issues can occur. It is for this reason that alpinists organise acclimatisation stages to prepare.

The new Montblanc 8000 Capsule Collection puts the world’s 14 highest peaks in the spotlight. These mountains – all measuring over 8,000 metres above sea level – are challenging and dangerous to ascend as there is hardly enough oxygen

for a human body to physiologically survive for more than a few hours.

A luminary of Montblanc's illustrious 'Mark Maker' initiative, Reinhold Messner was the rst to climb all 14 peaks without supplemental oxygen between the years of 1970 and 1986. Another Mark Maker recruit is the ex-Gurkha and British specialops veteran-turned-celebrity mountaineer, Nirmal Purja: no less than the fastest person to climb all 14 peaks, in 2019. Normally a single expedition would take a trained climber, with all necessary authorisations, over 12 months to complete. 'Nims' achieved this feat in just six months and six days, breaking six records in the process. He would have been quicker, he says, if it wasn't for the aforementioned paperwork...

Following his next record-breaking ascent last year, up Everest without oxygen but with Montblanc's 1858 0 Oxygen a xed as rmly as a carabiner to his wrist, Nims inspired the Swiss watchmaker's latest edition – primed to accompany his next adventure.

Named as tortuously as a crevasse crossing, the '1858 Geosphere Chronograph 0 Oxygen The 8000 Limited Edition 290' features a worldtime complication manifest as two 3D rotating hemispheres – the Northern dome dotted by 14 orange dots, marking the >8,000m peaks. But it’s the titanium caseback where the full scale of Nims’ achievements hit home: laser engraved with all 14 peaks’ pro les, two motivational quotes from the man himself… but also, poignantly, a string of Himalayan prayer ags.

Louis Vuitton has played an unexpected song for just over 20 years, a rare example of fashion reaching beyond its comfort zone into hardcore horology

Back in 2002, no one was expecting Louis Vuitton to launch a watch. As a conglomerate, LVMH already had its watch bases well and truly covered, from the automotive sportiness of TAG Heuer to the bejewelled confections at Chaumet. What could a luggage brand bring to the table apart from maybe a new take on a GMT?

Louis Vuitton’s opening salvo was solid. The Tambour, with its drumshaped case, hence the name, translated some of the Maison’s design codes – its monogrammed canvas and the precise yellow of the waxed thread used on its leather goods – into a classic three-hander. It was a quietly con dent launch that in no way prepared everyone for the crazy creativity that was to follow. There were signposts. The brand launched brightly coloured Regatta watches, devised the Orientation with its two compasses so you can nd north in either hemisphere and used its Mysterieuse to debut its rst in-house movement, magically hidden from view. But it was 2009’s Spin Time where the fun really started.

Time and travel have always been the dual inspirations at the heart of Louis Vuitton’s adventures in watchmaking. For the Spin Time this came in the form of split- ap departure boards, whose clacking was the soundtrack of train stations and airports. It was in the latter where the inspiration for a new form of jumping hour came to Michael Navas, designer and founder of La Fabrique du Temps – a high-end movement maker spun-o from febrile mid-noughties complications skunkworks, BNB Concept, which Louis Vuitton went on to acquire in 2011.

Navas took the usual single hour module and replaced it with 12 spinning

cubes. Every 60 minutes, the hour cube with its numeral visible would spin back to neutral, while the next cube in the sequence would turn to reveal its number. It was an industry rst and a sign that Louis Vuitton didn’t want to be just another fashion house with a watch brand; it wanted to be taken seriously as a watchmaker.

Louis Vuitton, like other fashion houses who had become major players in the watch industry, creatively parlayed the maison’s aesthetic touchpoints into its watches. The Tambour Moon collection –the name referring to the newly concave dial that gives the design a crescentshaped pro le rather than the presence of a moonphase – was the epitome of this, with numerous references to Louis Vuitton iconography in its designs. Its star-shaped ower motifs had become spinning small seconds; the brand’s signature shade of yellow was used as the tip of a GMT hand, which was wittily shaped like a Vuitton ‘V’, and the ricegrain detail on the dial was a nod to the weave of its Damier Graphite canvas. The straps also took inspiration from the brand’s back catalogue, featuring iconic fabrics, such as its Monogram and Damier canvases, alongside more traditional leathers and rubber.

Given its ocean associations – Louis Vuitton hosts its own regatta, the Louis Vuitton Cup, which is seen as preparation for the America’s Cup – it seemed natural that the brand’s next move would be its take on a diving watch. Which it was, though not in the way anyone expected. What Louis Vuitton did with its 2021 Street Diver was understand that all the functional elements that comprise a diving watch – the tactile rotating bezel,

Tambour Horizon Light Up, launched 5 years ago: Louis Vuitton’s third-generation connected watch

Photography:

bubble-round indices, legible dials, luminescence – are the very things that make this design so desirable. With their futuristic vibe and bold colours, the Street Divers o ered a 21st-century take on a classic style, creating a timepiece that was just as comfortable in a dive bar as it was on a diving boat, a piece of high fashion for the jet set.

And it was the jet set, or rather the gentleman traveller, that was the inspiration when Louis Vuitton decided to dip its toe in more connected waters. When the Apple Watch launched back in 2015, many luxury watch brands rushed to jump on the virtual bandwagon, unveiling what appeared to be glori ed movement trackers packaged up in a traditional-looking watch case. Louis Vuitton’s Tambour Horizon was the exact opposite. This was a smartwatch that was a bona de travel companion. Rather than just check your heart rate through Louis Vuitton’s My Travel app you could, well, travel the world. It had city guides, could store your ight information, your boarding passes, and your hotel reservations. It was the ultimate synergy of travel and time, of Louis Vuitton’s origins and its future. Its second incarnation, the Light Up, now has a gorgeous in nity dial adorned with 24 LED lights that transmit glowin-the-dark animations, such as the Lunar New Year animal as an animated rabbit lantern jumping over handbags. It’s another incarnation of the Tambour that de nitively proves Louis Vuitton is a maison that marches to the idiosyncratic beat of its own drum.

It takes a mastery of 34 cra s to make a ‘simple’ mechanical watch from scratch, as Svend Andersen notes in our Foreword – and he of all people would know. But the tally ticks far further north of 34, when you take in everything else, from métiers d’art decoration to designing the thing in the rst place, rendering that 40-something millimetres of metal on your wrist a hyperoptic nexus of history, artistry, ingenuity and sheer dogged toil, more than any other man-made object. Ever-aided by technological advances, but never without that expert, human touch

In the ’80s Svend Andersen co-founded the esteemed Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants, and now the quiet rebels of indie watchmaking that the AHCI has inspired are less beholden to the collectors, more driven by their own attitude, but by no means less dextrous with tweezer or le. Take Helsinki’s Stepan Sarpaneva: he quit Switzerland’s most elite ateliers in 2003 to forge his own neogothic vision in steel, regardless of whether or not anyone knew Finland was a hotbed of horological talent in the rst place.

Husband-and-wife duo Rebecca and Craig Struthers nurture a comparably rebellious breed of modern watchmaker, their Victorian workshop located down a cobbled alley in Birmingham’s gentri ed Jewellery Quarter. Their work is characterised by hardcore cra and dedication. The AHCI might frown at Craig’s adoption of a scrapped Audi car’s screenwasher motor to jig-up one of their vintage 8mm lathes for decorating bridgework, but needs must in the miasmic world of watch restoration… and, more tellingly, bespoke commissions.

“Some purists would say what we’re doing is sacrilege,” says Craig, “but at least these old tools are being used. Ask that 19th-century lathemaker now whether he’d

rather his creations were rusting in a shed, or still being used!”

Having graduated from Birmingham City in parallel, the two are bonded in antiquarian horology: academia in which Rebecca recently earned a doctorate, making her the rst watchmaker in Britain to gain a PhD in Horology.

“We trained in restoration, with littleto-no spare-parts supply,” she explains. “Watch restorers have to learn to make every component for a mechanical watch. But a er years of doing it for other peoples' watches we decided it was about time we started making our own.”

Sure enough, C & R Struthers’ rst ground-up, 100% English baby is seeing the light of day – sold-out for the forseeable, on account of only ve being produceable annually. Called Project 248, because of those 8mm lathes, two watchmakers and four hands, it certainly looks historical from Craig’s beautiful drawings, but it’s by no means a historical modus operandi. They’re doing it their way, which is historic enough.

Rebecca Struthers’ rst book, Hands of Time, a Watchmaker’s History of Time, is scheduled for publication by Hodder & Stoughton in April 2023, illustrated by Craig.Champlevé, cloisonné, basse taille, grisaille, plique-à-jour, inquage... From the roster of ancient decorative arts mastered beneath the anachronistically modernist, curved roof of Vacheron Constantin in Geneva, you wouldn’t think decorative enamelling was nigh-on extinct as recently as the ’90s.

Tantamount to alchemy, it’s still just as nuanced a process as when pocket watches began adorning themselves with hair-thin-brushed paintings from the 16th century, and still – necessarily – exacted in the same tortuous fashion, by one artisan at a time.

Geneva’s horlogers were the rst to use it, mastering their own technique of miniature painting in grand feu enamel under a protective ux coating. Metallic oxide powders are applied to a metal base (copper, silver or gold) in thin layers then successively red in a small, benchadjacent kiln hovering between 820°C and 850°C.

“Enamelling is alchemy, a cra from another age that has its own secrets,” points out Vacheron Constantin's master enameller. “Despite experience, the ring process entails permanent uncertainty. [It] requires calm, serenity and a certain ability to distance oneself… All the enameller's art is revealed in the re.”

Experience, too, teaches him to merely shrug when a whole day's work shatters or blisters and must be led to the bin.

The pictured grisaille technique – part of VC’s ‘Métiers d'Art Hommage à l'Art de la Danse’ series – starts with a dark or black enamelled background, rst applied with Limoges white dots to obtain shades of grey and chiaroscuro e ects. Thanks to the historic brand’s nurturing and development of talent from (in this particular example) Limoges, even the slightest fold in the tutus, the velvety texture of a ribbon, or the transparency of the tulle is revealed.

The kiln process is always a magical experience that is di cult to control. All the enameller's art is revealed in the re, VC’s master artisan continues. "This is like a Damocles’ sword because, despite experience, the ring process entails permanent uncertainty.

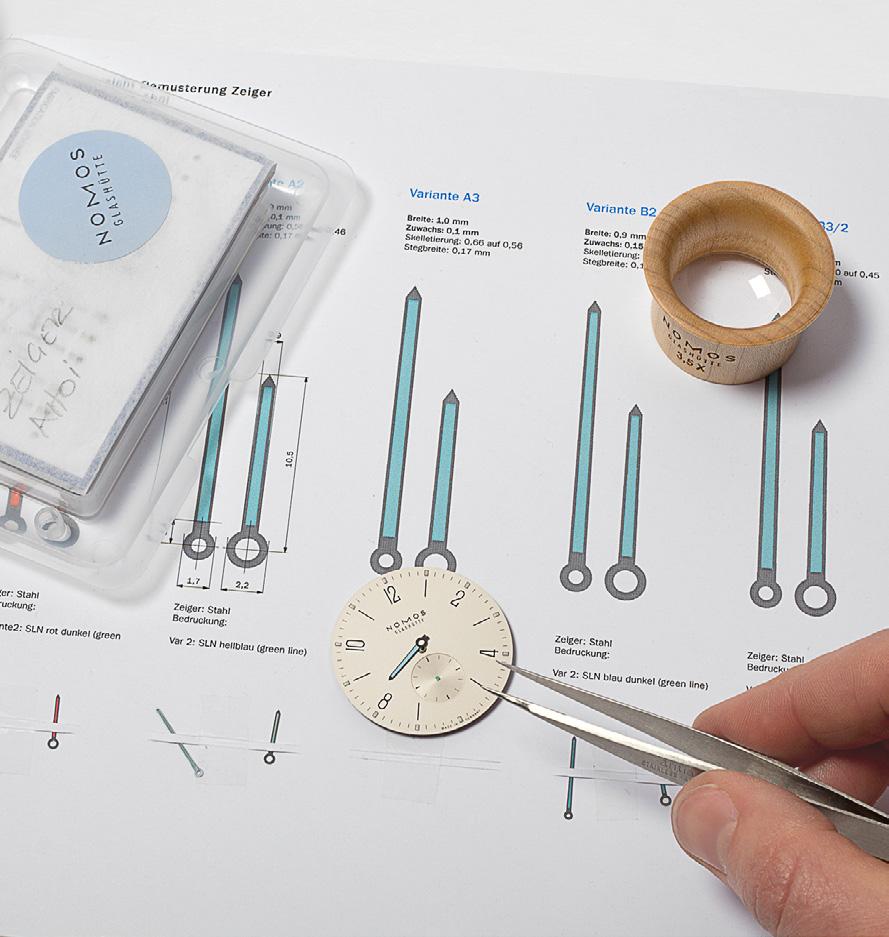

Here at 10:10, the exuberant arc of NOMOS Glashütte has been well-traced: not so much as a phoenix from the ashes as a brand-new phoenix, its nest built on the ashes of German watchmaking’s WWII ruination and the ensuing doldrums under the GDR. A er the Berlin Wall’s fall, NOMOS arguably brought mechanical watchmaking back to the Saxon village of Glashütte before anyone else, in cleanas-a-whistle Bauhaus guise, to suit its democratic commitment to quality.

However, chocolate-box-pretty villages in the Ore Mountains don’t see many live/work maker spaces, techno clubs or brutalist architecture. Watchmaking only settled there because A. Lange & Söhne’s titular founder persuaded Dresden’s palace to fund a social enterprise when he

noticed the local silver mines’ seams were tapped out. So while NOMOS is clever enough to keep building its formidable in-house manufacturing capabilities there, it’s even cleverer in rooting its designagency imprint where the hip-to-the-game creative talent remains: Ost-Berlin.

To visit Berliner Blau in Kreuzberg is to witness graphic exactitude on an excruciating scale. Inherently simple things like baton hands are reviewed in agonising detail; pure-white walls plastered with imperceivable iterations of a new Tangente model’s ‘12’ numeral or peppermint-green accent pondered and poured over.

It’s this devotion to balance and the contemporary, from a crucially metropolitan consideration, that keeps NOMOS so fresh.

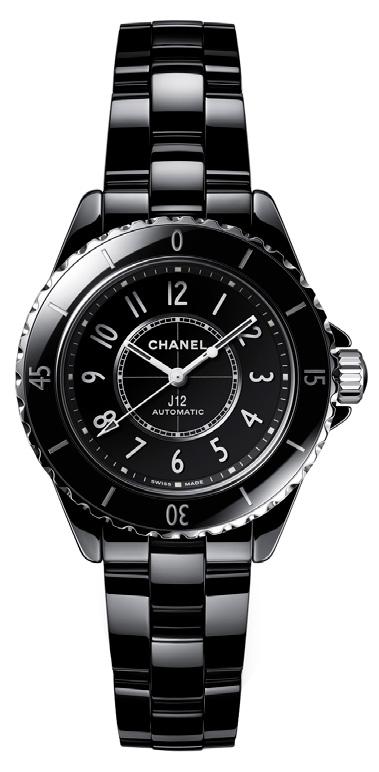

Even before the late, great Karl Lagerfeld immortalised himself, second only to Mademoiselle Gabrielle herself, very few appreciated how equally signi cant Jacques Helleu was to the latter-day Chanel brand. Which was probably how he liked it. Throughout his 40 years as artistic director for Chanel, familiarity with his work was what mattered.

What still feels odd is that the notoriously unstylish watch crowd are more likely to know of him than the fashion set – simply, as the man who in the early noughties made fashion a relevant player in watchmaking.

As if cementing Chanel No. 5 as fragrance royalty by putting Catherine Deneuve in a dinner suit in 1968 wasn’t enough, he also invented the J12 watch. And ‘invented’ is the right word, because brushing aside the Rolex-esque sports watch form that the target audience craved, nothing short of cutting-edge high-tech ceramic was the order of the day. Materials

bo ns G&F Châtelain were purchased lock-stock in La Chaux-de-Fonds and the crisp, quilted, monochrome gleam of Coco’s iconic 2.55 purse lived on in timepiece form.

What took him and his team a full seven years of R&D prior to launch in 2000 was the material. Helleu wanted it to be black (of course), scratch- and oxidisationproof and with a hardness close to that of diamond (all useful qualities for competitive yacht racing, which was his passion – in the J12 class of boat). The only successful protagonist of ceramic watchmaking had been Rado, whose technology was de nitively ring-fenced by parent group Swatch. So Chanel had to innovate solo, sintering furnaces, zirconium oxide substrates, the lot. As for G&F Châtelain’s hands at work, the notoriously nuanced, instinctive process of nal polishing had to be rethought and relearned to work with such a hard material.

For decades, ‘memento mori’ skull watches have been reminding us of our ever-encroaching death with every tick of the seconds hand. More recently, however, skulls have been preserving the memory of loved ones’ lives, which have already passed. We are talking, of course, of the moustachioed calavera and every autumn’s Dia de los Muertos – Mexico’s amboyant answer to All Souls Day.

The latest one-o piece from Chopard’s elite LUC horological hothouse, deep in Switzerland’s Val-de-Travers, literally plays along with the mariachi bands, as it is a chiming ‘minute repeater’: two tiny hammers ringing out the time on two circumferential ‘gongs’.

No ordinary minute repeater by a country mile, this is an extraordinary example of LUC’s already-extraordinary

Full Strike. Those hammers would usually strike two metal gongs xed to the movement, but here the hours, quarters and then minutes ring out with crystal clarity, since the whisper-thin gongs are machined from the same ‘monobloc’ of sapphire that covers the dial – resonant and intense, just like the calavera’s ghoulish stare.

Needless to say, hand-assembly is a suitably agonising undertaking for each movement’s dedicated watchmaker. Not least ne-tuning the ‘governor’ ywheel revealed on the Calavera’s right cheek, whose air-resistance acts as metronome to the cadence of the crystal gongs’ melody, in C# and F. Watchmaker as orchestral conductor – measuring our time on earth, just as the Mexicans do every November 2nd.

From clandestine special ops, strapped to wrists of Italian frogmen nning behind enemy waves, to sprezzatura Riviera élan: no wonder Panerai’s Radiomir commands such a cult

Sly Stallone, Arnie, Hugh Grant, Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson, Jason Statham… With perhaps the exception of Mr Grant, it’s safe to say O cine Panerai is the steroidal choice of men already plenty familiar with actual steroids. But this modern phenomenon of cult, oversize watchmaking was once a very di erent brand indeed. Not a brand at all in fact, on account of the Italian military secrets act.

A few years before being snatched from obscurity by the Richemont Group and given its own top- ight Swiss manufacturing facilities, it was a boutique Italian engineering rm on the ropes. If it wasn’t for a Japanese watch magazine running a nostalgic cover story in 1992, Panerai might never have been inspired to tentatively revive and commercialise a strangely shaped diving watch discontinued in the 1970s that was never known, let alone worn, outside elite naval circles.

A well-connected Croatian photographer called Monty Shadow might then have never spotted one of these Panerai reissues in a Milanese shop

window and been so bold as to doorstep Panerai with the promise of brokering some white-hot product placement on the wrists of two Hollywood friends in their respective blockbusters of 1996, Daylight and Eraser.

It all started as far back as 1860, at a tiny orologeria on Ponte alle Grazie in Florence. Giovanni Panerai’s workshop supplied all manner of equipment for the Royal Italian Navy. Long before its rst handful of watches were created for covert WWII scuba divers, O cine Panerai developed precision gun sights, illuminated by a radium-based paint that Giovanni dubbed ‘Radiomir’, and patented in 1915.

Radiomir's sub-aqua adhesiveness made it a go-to for glow-in-the-depths dial markings, when in 1936 Panerai started converting cushion-shaped Rolex pocket watches with screw-down crowns into diving wristwatches. (The less-lethally radioactive ‘Luminor’ superseded Radiomir in 1949, based on tritium – lending its name to Panerai's

chunkier generation of military-issue tickers, hatches rmly battened down by D-shaped crown guards.)

Cleverly, the Radiomir dial’s ‘sandwich’ construction meant the radioactive paint didn’t have to be painstakingly printed or written: the dial markings were simply stencilled-out, then riveted on top of a fully luminescent base dial. Brilliantly elegant engineering that was a little too brilliant: as they approached their target, riding the shallows aboard slow, torpedolike Siluro a Lenta Corsa mini-subs, the Italian Navy’s elite Incursore had to shroud their le wrists with cloth.

It was the chunky Luminor that Panerai rst marketed in ’92, in keeping with the era’s action-hero alpha culture. The original Radiomir design was only made public in 1997 when the Vendôme Group – today Richemont – acquired Panerai, moving production wholesale to the shores of Lac Neuchâtel in 2002 with a purpose-built, largely autonomous manufacture

The Radiomir’s cushion case contours

to a slender, rounded-out square, with only the easy-to-grip conical crown and wire lugs interfering with an otherwise perfect, smooth ‘pebble’ of steel or gold. A delicate balance of lines and facets that, like every industrial icon, never dates and always bears revisiting. Which brings us to the latest Quaranta evolution – ttingly revealed during Milan Design Week, marking Panerai’s debut as a partner of the 2023 Salone del Mobile.

Radiomir Quaranta retains all those mid-century features, only with a small seconds subdial and date now in the mix, and – as the nomenclature implies – pared down to a versatile 40mm in diameter. White dials, blue dials, alligator straps, unisex proportions… it’s all a far cry from cigar-chomping beefcakes at Planet Hollywood parties, but all the more progressive for it. That the Radiomir remains true to its 87-year-young utilitarian form says everything of good watchmaking’s ability to – ironically enough – transcend time itself.

It’ll be back.

It must have taken guts to set-out stall at 1980’s Basel watch fair, at the height of the quartz crisis, when no one had heard of you, let alone seen a timepiece like yours. But this is precisely what Carlo Crocco did. And despite failing to attract a single customer on the rst day, or delivering an actual watch till 1983, the rest is a history we all know too well, because Crocco’s brave venture was Hublot.

The scion of the Italian Binda Group dynasty, best known for making Breil watches, Carlo Crocco named Hublot a er the French word for his out-there ‘porthole’ case design – screws to the front, steampunk-goes-luxe. But it wasn’t the case that had consumed three years’ R&D previous. It was Crocco’s decision to t the rst-ever strap in Swiss history that combined natural rubber with synthetic. Not only that, but t rubber, whatever the origin story, to luxurious gold.

As Crocco was an avid sailor, he wanted

to create a watch that looked as good with a suit and tie as it did on a teak deck. The latex compound, most commonly sourced from the Pará tree, was the perfect mix of stretch, UV and sweat resistance. Reinforced by an inner steel blade to enable durability as well as thinness, the genius touch was to add vanilla scent to the mix, masking the slight acrid smell of the natural substrate.

The fact that we now see rubber so frequently throughout watches and jewellery – especially in rebellious ‘fusion’ with ostentatious gold – can be credited entirely to Crocco. He was ahead of his time, but luckily modern horology’s maven saviour, Jean-Claude Biver, saw Hublot’s long-overdue opportunity in 2004, pumping-up the Porthole and getting Big Bang – the new ‘it watch’ for Millennials –snapped up by LVMH in the process.

Playing the long game is the way of things in watchmaking. Here, short-

Building any brand takes vision, courage and belief. Building a watch brand, though? To that list you can add ‘patience’, for not only does a decent timepiece take years to realise, but customers aren’t in the regular habit of toying with new ones, least of all another of yours

term business plans, snap polls, market research and FMCG guerrilla tactics simply do not apply. Car brands look like microwave meals or washing detergents by comparison to Swiss brands; for their sheer, drawn-out product-development process; the time it actually takes for the requisite parts of a movement to be made, then land, at once, onto a watchmaker’s bench (up to a year). Then of course, the longest wait: for even the most loyal of customers to come back for more.

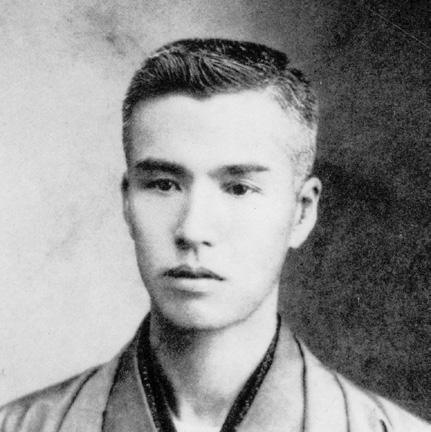

The quiet founder of Japan’s giant of watchmaking, Seiko, even embraced this steady tick of time, making “stay a step ahead, but just one step” the evenkeeled mantra of Kintarō Hattori at the turn of the century. This slow but steady spirit of innovation saw Seiko grow into the titan we know now, master of Argos-catalogue entry-level premium through to Brompton Road boutique-only masterpiece.

A week-long bullet train tour is required to appreciate the sheer extent of these capabilities, which feels doubly appropriate as, despite its space-age rolling stock and 200mph average speed, the rst rails were laid as far back as 1964 for the Tokyo Olympics – the same event for which Seiko, as o cial timekeeper, successfully reduced the size of a quartz timekeeper from cupboard proportions to a handheld box. Five years later, they’d shrunk the technology even more, and launched the world’s rst quartz wristwatch, Astron.

Around the same time, a self-admittedly wet-behind-the-ears Jack Heuer was in the business of not only rescuing his family’s historic marque, but taking a punt on Heuer’s sporting pedigree by leveraging precision timekeeping's visibility in motorsport's encroaching golden age. Seiko’s Astron sparked the aforementioned quartz crisis, throughout which Jack steered Heuer

Jack Heuer’s eponymous family firm distilled every crucial element of the driver’s watch into the Carrera of 1963 – reissued in this 60th anniversary year

Jack Heuer’s eponymous family firm distilled every crucial element of the driver’s watch into the Carrera of 1963 – reissued in this 60th anniversary year

devotedly and masterfully – at least until the ’80s, when he was unceremoniously dumped by new investors.

Opportunity, reactivity and, yes, patience was what it took. For a start, Jack had an eye for what Heuer’s speciality –the utilitarian chronograph – could grow into, post-war. Cue the ’60’s dashing triptych of driver’s watches (all stemming from the dashboard) with equally dashing names: Autavia, Carrera and then the square-jawed Monaco. Racy designs that – in Jack’s second stroke of brilliance – worked their way onto the wrists of actual F1 pilots, down to a wholesale deal with Swiss driver-cum-pitlane hustler Jo Si ert, resulting in Steve McQueen’s choice of wrist fodder for Le Mans (1971), then Scuderia Ferrari’s prancing horse sharing real estate on the nose cones of Mario Andretti et al.’s cars with the angular shield of Heuer (soon to be ‘TAG Heuer’).

All of which, to make it a hat-trick, teed-up Heuer perfectly for a collaboration with Breitling on 1969’s doggedly wrought ‘Calibre 11’ movement, mounting a Dubois-Depraz stopwatch module upon

a Büren micro-rotor-powered base calibre (the ‘micro’ meaning the spinning weight was ush with everything else), ultimately making the chronograph wristwatch self-winding, at last – plus, crucially, democratic over the same year’s upmarket El Primero from Zenith.

Hublot, Seiko, Heuer: respectively playing the long game, laying the grassroots, pivoting to rescue and renew… But how to breathe life into a formerly garlanded enterprise that’s been unceremoniously shut down in its prime, then dwindled to the point of forgotten? What sort of conviction and patience does it take to piece things back together, then profess convincingly without reducing your family’s heritage to a jumpstarted, badged-up cash-in?

Su ce to say, Adolph Lange’s greatgrandson Walter (1924–2017) did it right. It might have been easier if A. Lange & Söhne, and so many other watchmakers in Germany’s horological heartland, Glashütte, hadn’t been bombed on the very last day of WWII. Even easier if the Russians hadn’t raided the factory oors,

A. Lange & Söhne scion

Walter Lange came back from the West to revive his family firm after the fall of the Wall, stoically plying the exacting craftsmanship of trad’ Saxon horology, such as engraved ‘swan neck’ balance bridges and adjustors, pictured

The restless legacy of Seiko and Grand Seiko’s founding father, Kintarō Hattori means as much painstaking artisanship as volume-led market dominance

too, for machinery, tooling and drawings. But come the reuni cation of Germany a er the fall of the Berlin Wall, Walter – in cahoots with IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre’s brilliant and visionary boss Gunter Blümlein – falteringly, un aggingly rebuilt ‘the nest German watchmaker’ from the doldrums of Glashütte’s consolidated ‘Uhrenbetriebe’.

Monday 24th October 1994 was the day A. Lange & Söhne unveiled, in the form of four beautifully classical yet contemporary watches, its new era – to immediate raptures. And yet, it says everything of watchmaking and its prerequisite ‘patience’ that we’re still awaiting any of the above to cement themselves in the long term, given recent resurgence and revival relative to centuries-old heritage.

Time will tell. And that’s half the fascination.

James Bond and every single Apollo astronaut can’t be wrong: the sharpest kit at watchmaking’s cutting edge comes from a sleepy town called Bienne

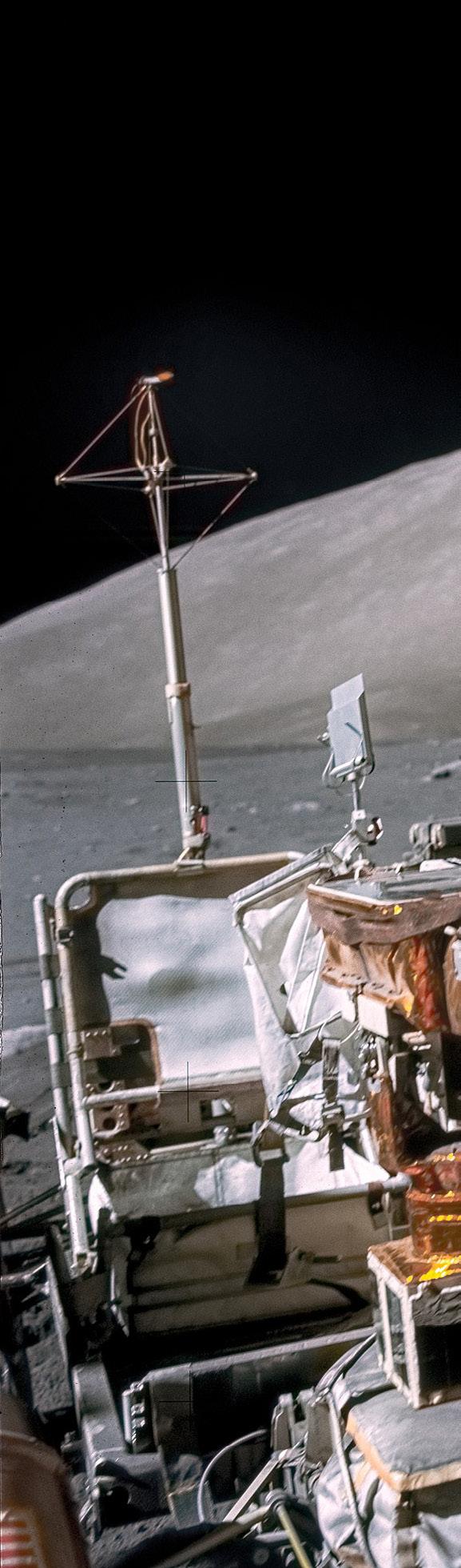

Until his death in 2017, Gene Cernan remained stoic in his belief in Omega’s commitment to, “make the nest watch piece,” as he would attest at countless appearances, quipping: “not only in the world, but in the entire universe.”

Of any earthly being, Cernan is best quali ed to make such a bold claim, given his hitherto unchallenged status as the ‘last man on the moon’. He helmed the Apollo 17 mission, which celebrated its 50th anniversary last December, spending 75 hours on and o the Moon buggy, always – as pictured on the previous page – with his trusty Omega Speedmaster chronograph velcroed around the right arm of his spacesuit.

To this day, the so-called ‘Moonwatch’ has been worn by astronauts on every lunar landing. It was quali ed by NASA for “all manned space missions” in 1965 and became o cial kit riding the nose of every Saturn V rocket, beginning with Apollo 11 in 1969, going on to prove invaluable aboard the “successful failure” that was Apollo 13 in 1970, timing a critical 14-second re-entry burn.

You can view Captain Cernan’s scu ed-up ref. ST 105.003 ‘Speedie’ in all its steely utility at Omega’s museum in Biel, Switzerland – now whole again, having had its manually wound innards scanned by cross-sectional ‘tomography’ X-ray technology, when Omega bowed to fanboy pressure back in 2019 and revived production of the original ‘Calibre 321’ movement, for a very-few special editions.

The museum itself is part of another innovative feat of engineering, albeit on a multi-storey scale. Dra ed by Japan’s Shigeru Ban in his signature biomorphic style, Swatch HQ crouches incongruously amidst bland downtown Biel/Bienne on the German/French-speaking border of Switzerland’s Jura; all undulating, interlaced wood, connected by a soaring and sinuous arch. Using the regenerative energy of groundwater from rain, collected via underground wells, rooms are directly cooled or heated by heat exchange, while grass helps the wells to lter and clean the rain as it descends to the ‘phreatic table’.

Omega’s commitment to innovation goes on and on. While this building is shot through with natural references, its heart is pure machine: rising 14m high and occupying a space 30m long and 10m wide, a roboticised stock delivery system shoots through its core, where every watch that leaves the building starts its life.

Some 30,000 boxes are distributed over four aisles, containing everything from movements to hands and cases to dials, all programmed by barcodes and shu ed in a mechanised ballet by Wall-E-like entities on a bungee. Only two acclimatised humans are allowed to enter this space, which maintains its atmospheric oxygen at 15% rather than 21%, so that it can’t burn.

That this is the ‘heart’ of the watchmaker’s home is only the start of the metaphor. For where Omega’s every other endeavour of the 21st century lies is at the ‘heart’ of every mechanical watch: its

pulsing, ticking escapement.

Even the elite of high-end horology are content to stick with the tried-and-true ‘Swiss lever’ escapement: 30 parts of steel, brass and ferrous alloy, alternately locking and unlocking the geartrain (powered at its other end by the mainspring) to which the hands are attached, four times a second, as dictated by the beat of a tiny, oscillating pendulum in wheel form. Fine-tuned to ‘chronometer’ level, it’ll beat with a precision that hovers between –4 and +6 seconds a day – more than adequate for most of us.

But not for Omega. In 1999, it exacted upon commuting its reputation for ultraprecision as timekeeper for the Olympic Games from trackside to, literally, by your side. And the answer lay in the Isle of Man’s one-man horological tour de force, Dr George Daniels.

Daniels had spent two decades –and plenty of prototypes besides – failing to convince the Swiss of his ‘co-axial’ escapement: nothing less than the greatest advancement in mechanical timekeeping since the above, dating back to the 1700s. By superimposing a second escape wheel and adding a third prong to the lever locking and unlocking it, Daniels’ invention of 1975 eliminates all sliding friction and therefore the need for mucky lubrication. Rolex and Patek Philippe may not have cared, but in movement-making giant ETA, and ultimately its Swatch Group stablemate, Omega, Daniels nally found a kindred spirit.

“ETA needed a forward-looking technology that would attract new blood back into the industry,” explains Michael Clerizo, author of George Daniels: A Master Watchmaker & His Art, speaking of a time when Switzerland’s engineering graduates were more likely to be attracted by local micro-tech than dusty old brands up in the mountains.

“The Omega Co-Axial, as it became known, turned a dead end into a highway,” Clerizo says, “it kickstarted a spirit of watchmaking innovation.”

As if it wasn’t enough integrating co-axial tech across its entire range, upping service intervals to eight years and warranties to ve, Omega still weren’t done. Launched in 2015, a new system of tests for anti-magnetism, accuracy and water resistance was unveiled in cahoots with the Swiss Federal Institute of Metrology (METAS).

The METAS test, conducted in-house by visiting METAS bo ns, was, and still is, open to other brands to use; but it's easy – or not as the case may be – to see why only Tudor has bitten too. To earn ‘Master Chronometer’ certi cation, amongst plenty more real-world wear and tear besides, the nished watch is exposed to

a whopping 15,000 Gauss magnetic eld, with the functioning of the movement (i.e. the escapement’s “tick, tick, tick”) checked audibly using a microphone.

To the humble mechanical watch, magnetic elds are still Public Enemy No. 1. Shocks, water and (thanks to the co-axial) lubrication have all been dealt with over the years, but proximity to a strong electrical charge or even the smallest ‘permanent’ magnet is still enough to magnetise the tiny ferrous components ticking inside your watch, causing them to stick together, repel each other, or behave erratically. More so these days, thanks to our crowded lives of devices. But, yet again, not content with just sticking to the “it’ll do”, Omega’s closely guarded new cocktail of silicon and metal-alloy materials deals with that too.

It is mechanical timekeeping with relevance and quotidian readiness, rather than rheumy-eyed anachronism for the sake of it. The reason for choosing 15,000 Gauss as a barometer is because, although it is the type of onslaught you’d get if you were having an MRI scan, anything from a fridge magnet to an iPad can stop a watch. So Omega’s Master Chronometer-rated co-axials are prepared for the worst – even

worse in fact, but that’d be more than could be said for the person wearing it.

Smoother running, electromagnetic resilience… and now? Nothing less than near-perfect precision, getting on for electronic quartz extremes of accuracy. Again, coming down to the ‘pendulum’ wheel pulsing at the heart of the escapement.

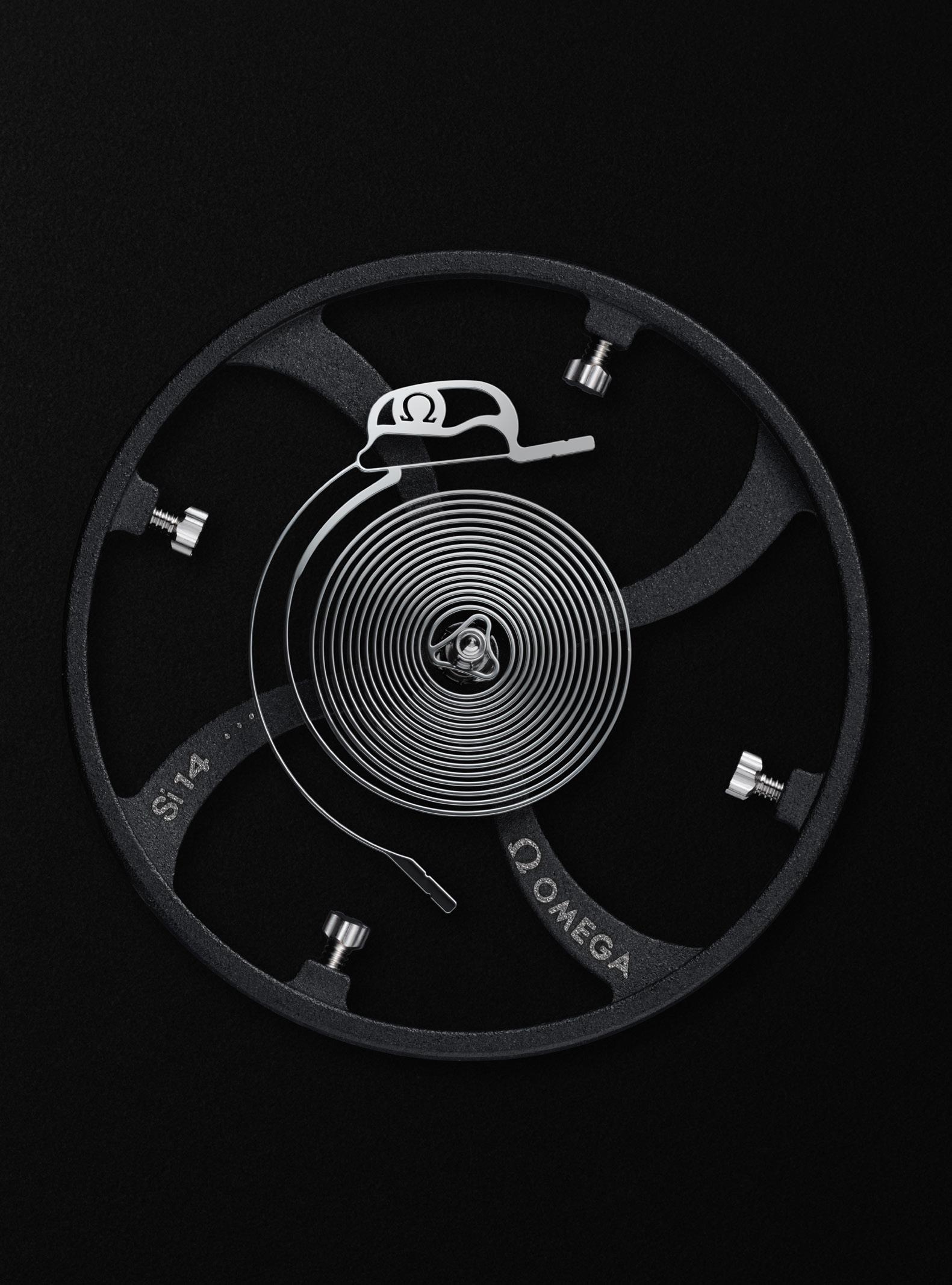

It pivots on a hairspring, whose coil ‘breathes’ with every contraction and expansion. The more evenly concentric those breaths are, the more stable and easily regulated it is (generally via moveable weights dotting the attached balance wheel). Omega’s surprise opener for 2023 was the silicon ‘Spirate’ balance spring – as technical and unsexy as the previous sentence implies.

Bottom line: thanks to an eccentric adjustment point at Spirate's outer terminal curve, Omega has whittled things down to an error rate of 0/+2 seconds a day by quite literally reinventing the wheel: a silicon spring allowing the watchmaker to act on the sti ness of the hairspring from both sides. Horological rocket science, of which Captain Cernan would surely approve, as well as NASA itself shooting for the moon yet again.

The 'Master' certification means METAS's visiting boffins reckon Omega's watches are good to leave the factory, fit to survive an MRI scan

'Spirate' is a new spiral geometry in etched silicon, allowing a watch's ticking 'pendulum' to be attached at two points for near-perfect precision

Mystique, cult-appeal, desirability and romance: all apply to the rose-red-and-whiteagged Swiss dynasty of watchmaking –bastions of hugely lucrative anachronism, which, nevertheless, cannot be caught napping, as our tenfold pick of plucky timepieces proves

Starwheel (previous page)

‘Wandering hours’ were invented as far back as 1656, for a nocturnal wanderer in human form, Pope Alexander VII. Rome’s Campani brothers conceived for his insomniac holiness a backlit clock readable without the hassle of lighting a candle, and it lives on in miniaturised form as Audemars Piguet’s latest adventure in stripped-back ‘techno’ watchmaking. A teacup ride in wrist form, three hours ‘satellites’ take it in turns to track across a 120º minutes scale. When it’s time for a disc to begin another arc at 0 as the other reaches 60, a ‘starwheel’ nudges it round to align the next hour numeral accordingly. Amen to that.

£49,700

Keeping alive the vision of three successive generations – Léon, Gaston and Willy Breitling – the ‘pilot’s pilot-watchmaker’ of La Chaux-de-Fonds, Breitling has with the Premier Chronograph embodied not only a formidable legacy as inventor of the modern ‘chronograph’, but also its lessknown duties dressing Civvy Street as well as cockpits and their occupants. As Willy Breitling insisted, the Premier was an “unmistakable stamp of impeccable taste”, launched in the ’40s as horological, sartorial respite from the wages of war proving so wearisome for gentlemen at the time. And regardless of demeanour today, let alone the rose-tinted looks, the stopwatch mechanics ying within remain the best of the best.

£7,150

The irrepressible charisma of Fabrizio Buonamassa-Stigliani was never going to be contained behind the closed doors or velvet ropes of press appointments and product launches. And the same goes for his famous sketches, o en dashed o with spontaneous, Roman verve. These e ortless, economical strokes of graphite have, since Buonamassa-Stigliani took the creative helm of Bulgari’s watch division, dra ed the 21st century’s only genuinely fresh, forward-looking family of watch design: the Octo. Its 100-plus facets in eight-sided form may be a headache for the case machinists, especially in 2.23mm-thin ‘Finissimo’ form, but they hold together poetically. And the dial, sketched by the man himself, now shows the lightness of touch this takes.

£13,800

Its breathless exploits timing every discipline at the Olympic Games, kittingout lunar landers, and leaping o buildings strapped to the wrist of 007 all distract from what Omega has mostly specialised in for over a century: quietly composed, classical design and re ned elegance; the go-to for any well-heeled white collar. In this particular case, a domed pine-green dial reminds its wearer of Omega’s other major, more domestic endeavour ticking beneath: extreme precision and total magnetic resistance, mastered – ‘master’ being the operative nomination – in a factory surrounded by conifer and r.

£4,700

Omega De Ville Prestige

Omega De Ville Prestige

There are worldtimers, and then there is the Patek Philippe World Time. A direct descendant of the ingenious conceit mastered in the 1930s by Louis Cottier, perfected by his immediate client in 1999, the user can simultaneously correct the 24-hour time in all 24 major timezones in one-hour increments, by simply pressing the pusher at 10 o’clock, notching-on the 24-hour ring adjacent to the 24 cities named circumferentially. For the rst time, Patek Philippe is interpreting this cosmopolitan icon in a platinum and blue combo, with a dial adorned in radiantly hand-guillochéed texture, only adding to the faded glow of travel’s golden age.

£59,050

It was on 8th July 1952 that the British North Greenland Expedition le Deptford docks near the home of time itself, Greenwich. It would be a two-year scienti c mission studying a decidedly chillier, rather less ‘Green’ land, and of its 700-tonne consignment, a full ve pounds was taken by 30 Tudor watches. 70 years on, all their vital tool-watch tropes haven’t just been revived with a sepia tint; the new 39-millimetre Ranger is everything an Arctic explorer would demand for a 2022 mission: chronometer precision, rugged build and absolutely no nonsense.

£2,370

Four concave quadrilaterals converging at a central vertex at right angles, with two tips pointing outward symmetrically: a heraldic symbol associated with the Knights Hospitaller of the Crusades, the city of Amal , the Prussian order Pour le Mérite, and of course a small island in the south Mediterranean. The Maltese cross is laden with poignancy through historical Europe, and that includes its duty as visual leitmotif for Switzerland’s oldest watchmaker, Vacheron Constantin. Prosaically, it relates to the shape of the wheel that nudges a perpetual calendar’s leap-year indicator every 364th or 365th day, but – rather more poetically – also inspires the design of another brand speciality: the balletic ‘tourbillon’ carriage.

£POA

Vacheron Constantin

Traditionnelle Tourbillon

Vacheron Constantin

Traditionnelle Tourbillon

Those 30 watches stowed aboard the British North Greenland Expedition – and indeed their modern evolution featured opposite – couldn’t have happened without Tudor’s mothership Rolex and its expedient e orts of the 1930s. That’s when Geneva’s watchmaking giant began to equip numerous expeditions with its Oyster watches, their case and crown both hermetically screwed down against dust and water. Badged as ‘Tudor’ post-war, then ‘Explorer’ following Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s Everest summit of 1953, the Oyster system protects pilots’, divers’, even ne-diners’ Rolexes. But the hardcore Explorer remains the true alpinist – even when blinged-up with ritzy yellow gold.

£9,900

First unveiled in 1996, the Française blended a metal bracelet with Cartier’s icon of horological art nouveau, the Tank –its bold links in perfect harmony with that case design of 1917, itself inspired (rather incongruously) by the footprint of the era’s war machines, crawling about the Western Front – from which, of course, Paris’s grande maison borrowed the Tank’s name. Despite its silky articulacy, the '96 reboot was so coherently realised as to assume a monumental, monobloc form, which Cartier is refreshing for 2023: tauter pro le lines, and com er than ever.

£5,200

Post-war, as the jet age began warming its engines, its pipe-smoking, lab-coated protagonists demanded ever-more precision and anti-magnetism. Something the pilots themselves bene tted from, in the shape of the iconic Mark 11 of 1948. It was a natural evolution of IWC’s contribution to the MoD’s war e ort – one of 12 brands answering the uncompromising specs of its ‘W.W.W.’ infantry watch – and forged the core DNA of a lineage that runs and runs. This year’s Mark XX is the latest and most faithful yet.

IWC Pilot’s Watch Mark XX

IWC Pilot’s Watch Mark XX

In 1975, the manager of Workshop 4 at Zenith’s historic HQ, deep in the valleys of the Jura Mountains, exacted upon a bold and brave enterprise. In doing so, Charles Vermot secured the future of Swiss watchmaking’s most pioneering ‘chronograph’.

For the past six years, the component parts of every El Primero chronograph movement – the rst wrist-worn stopwatch to wind automatically, and tick more precisely at 5Hz rather than 4Hz –had completed their nine-month journey through the factory, landing on Vermot’s team of watchmakers’ workbenches for nal assembly, a full 2,500 operations and 300 artisans down the line. Rightly so, Vermot was about to retire on a high, a er 40 years of service.

Dampening proceedings somewhat, an order came from Zenith’s American mothership, Zenith Radio Corporation (nomenclature purely coincidental) to cease all production of mechanical watches. All e orts were to be redirected toward novel quartz technology, which meant scrapping the very makings of

El Primero at the price of molten metal. Not to mention scrapping the IP of one of the most revolutionary chronographs conceived.

But Vermot had other ideas.

Refusing to see a decade of his life tossed on the scrap heap, over the next few evenings he furtively relocated the calibre’s pressing tools, cams and cutting tools to a dusty attic. He made sure each part was labelled and listed, and for good measure copied out the entire production process into an accompanying le.

Come the ’80s, with mechanical watches back in vogue, the Swiss consortium in charge of Zenith were struggling to nd that dustcover to triumphantly whisk away, knowing that El Primero should be its comeback hero. Being a tight-knit cottage industry, even in retirement it didn’t take long before old man Vermot was knocked up, no doubt by newcomers with caps clutched rmly in otherwise empty hands.

With a suppressed pride of his own, he retraced his commute back to Le Locle’s town centre and led the new management up the stairs, to a dusty attic…

There’s the patience of its practitioners, then the pluck of its protagonists. But horology as we know it wouldn’t be without another ‘p’: pride