Kieran Culkin Diego Luna Torrey Peters Will Sharpe Leila Mottley George Saunders Jasper Morrison

£10

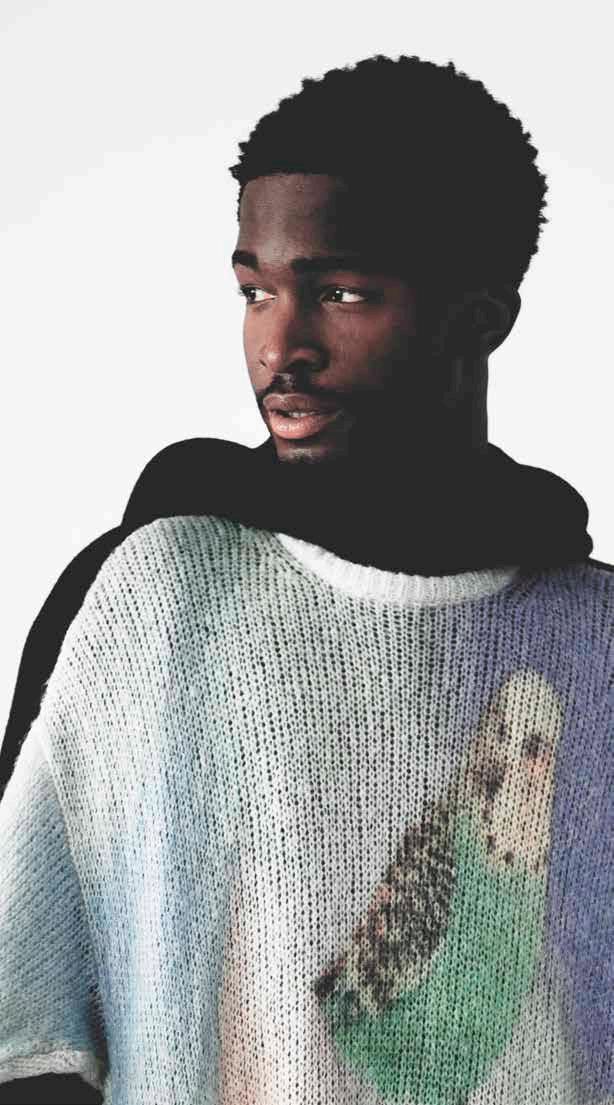

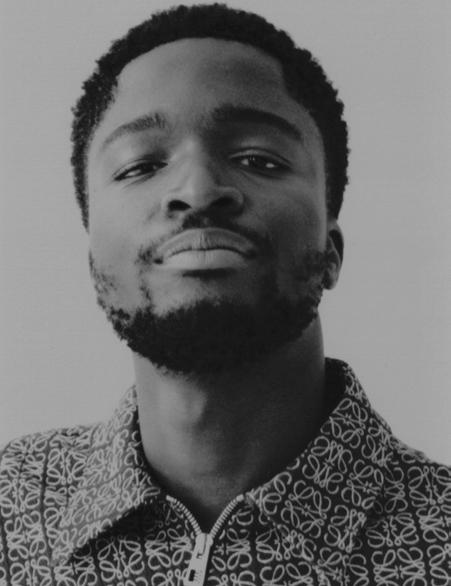

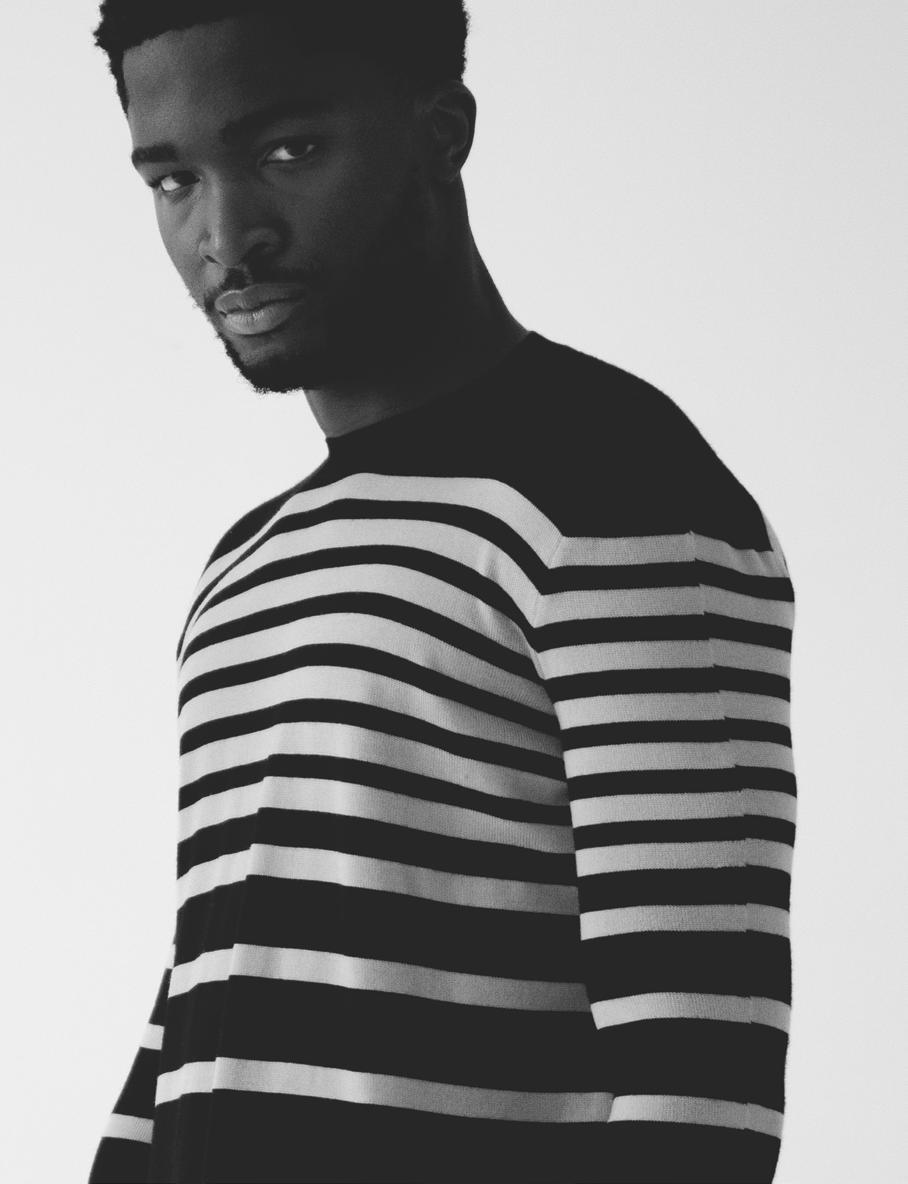

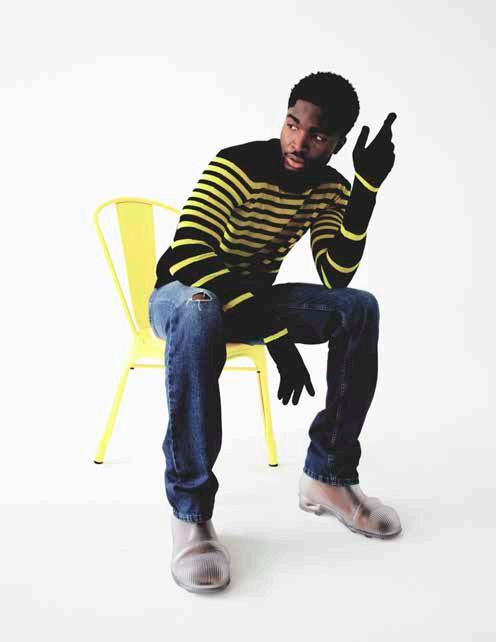

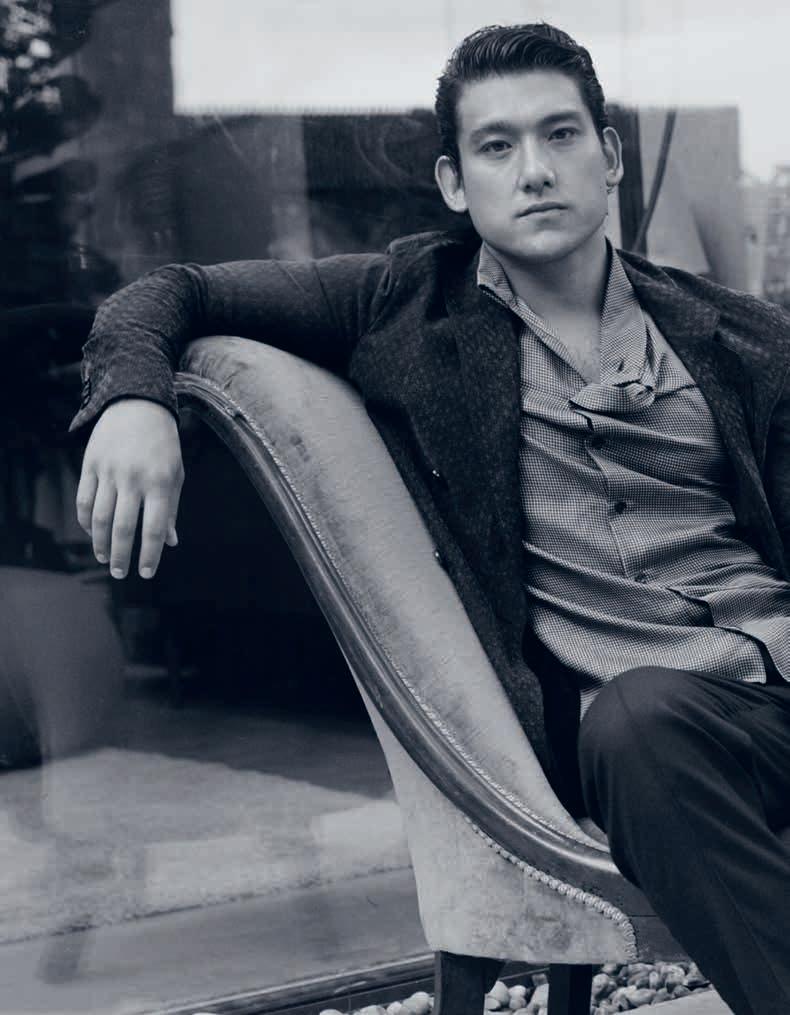

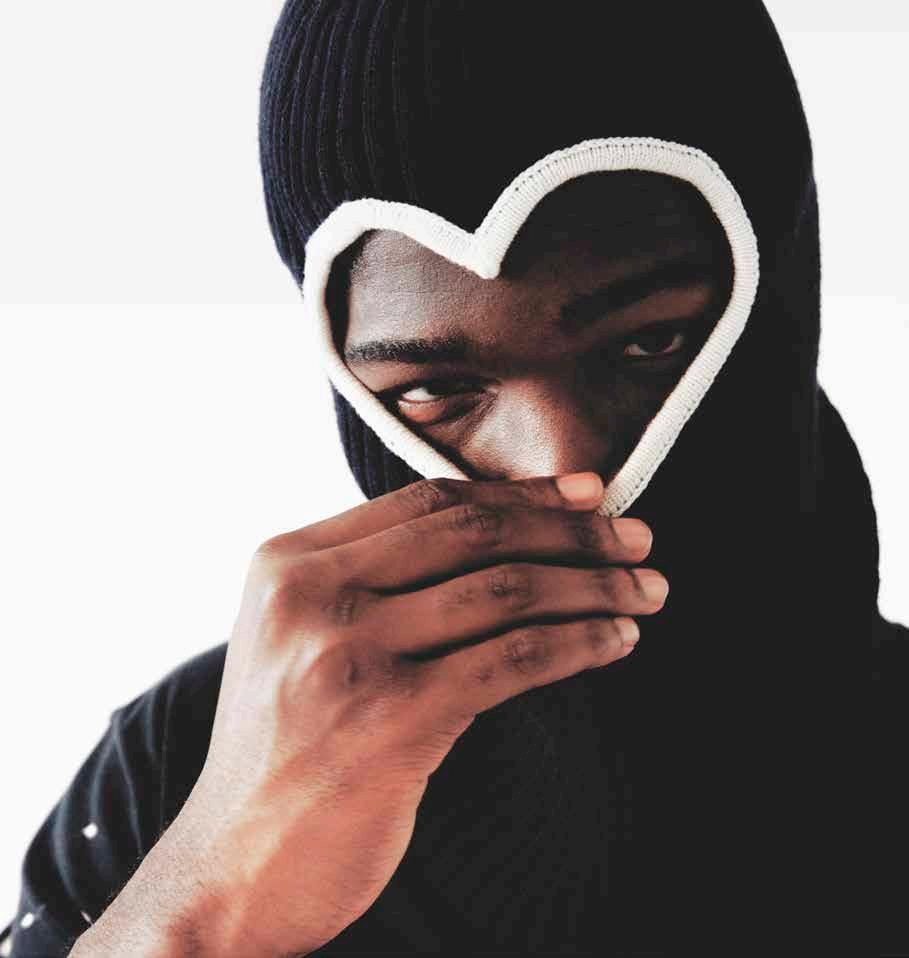

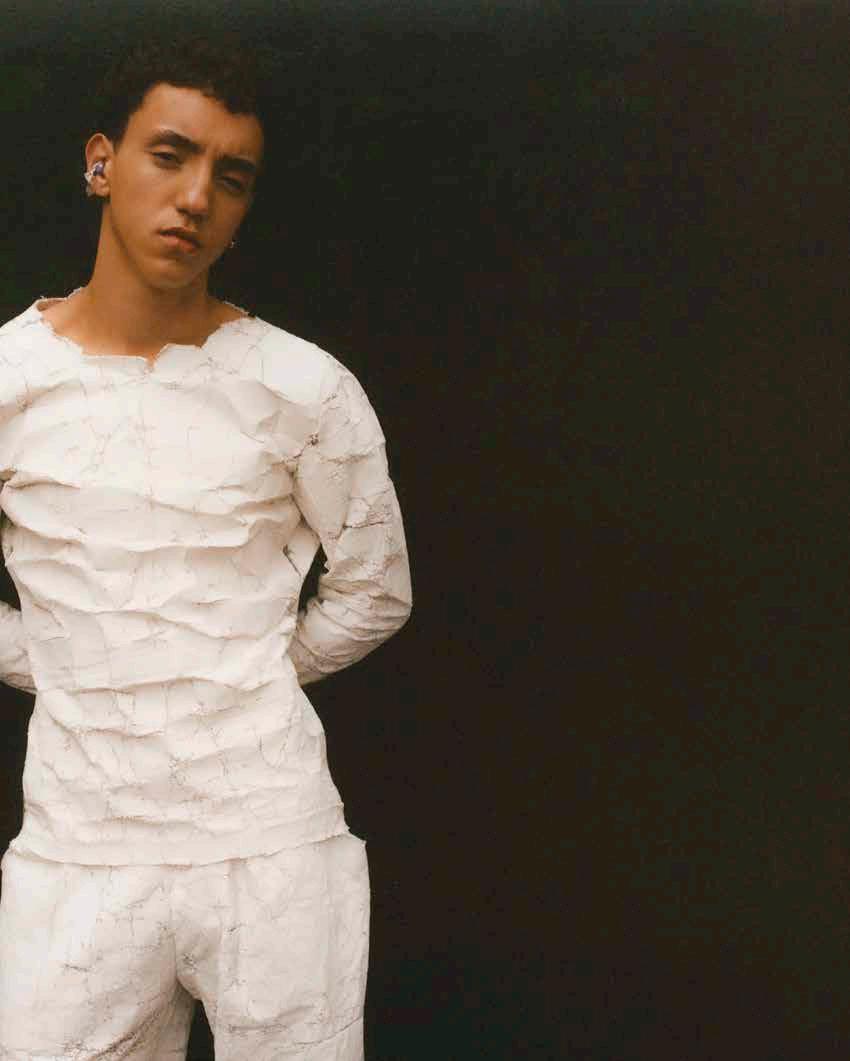

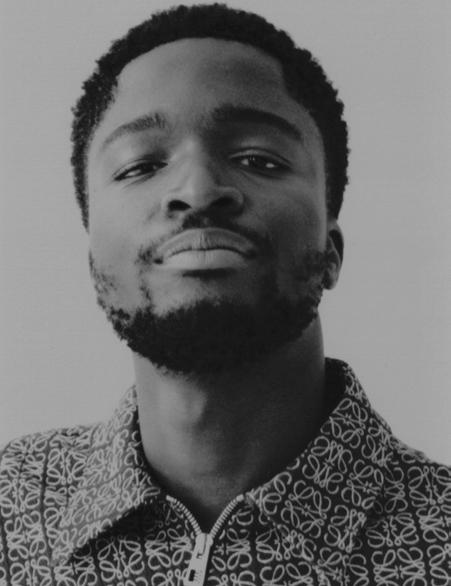

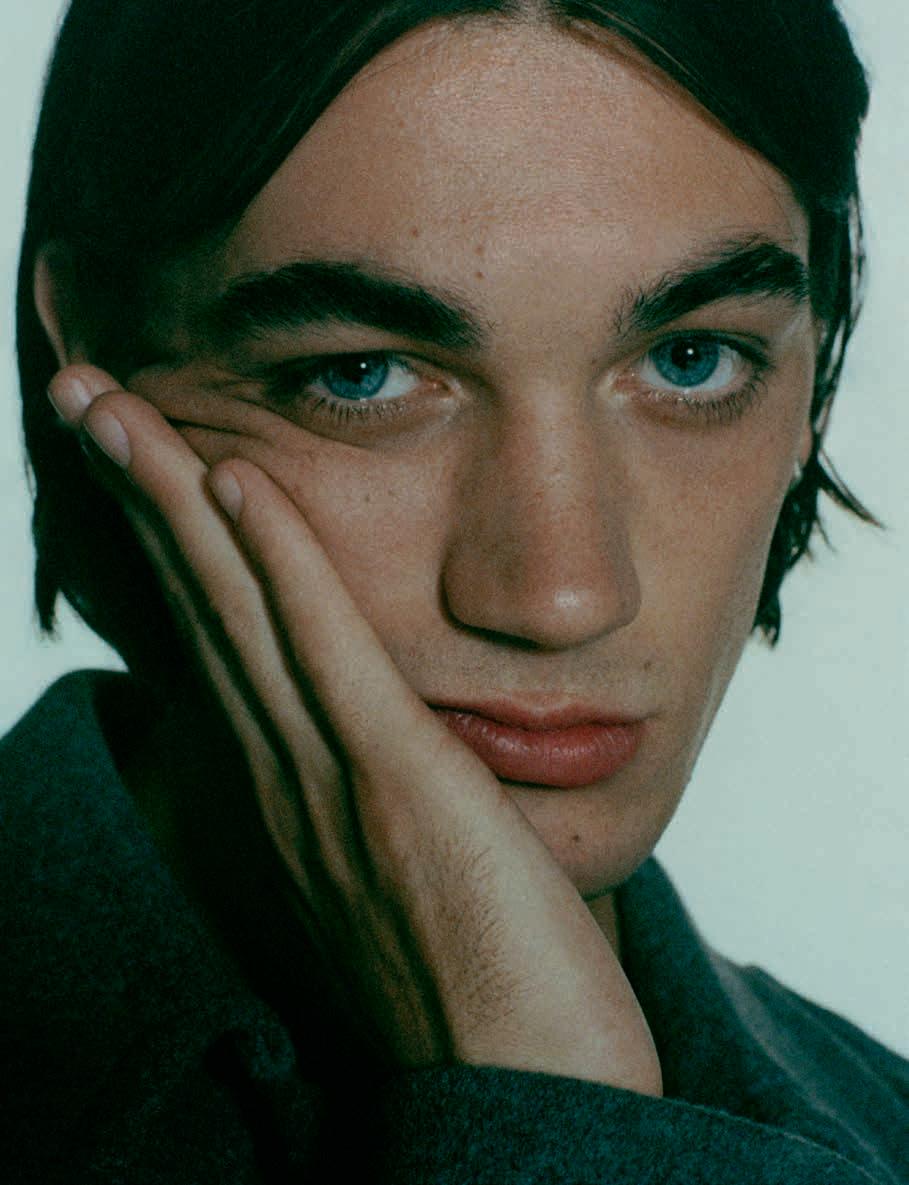

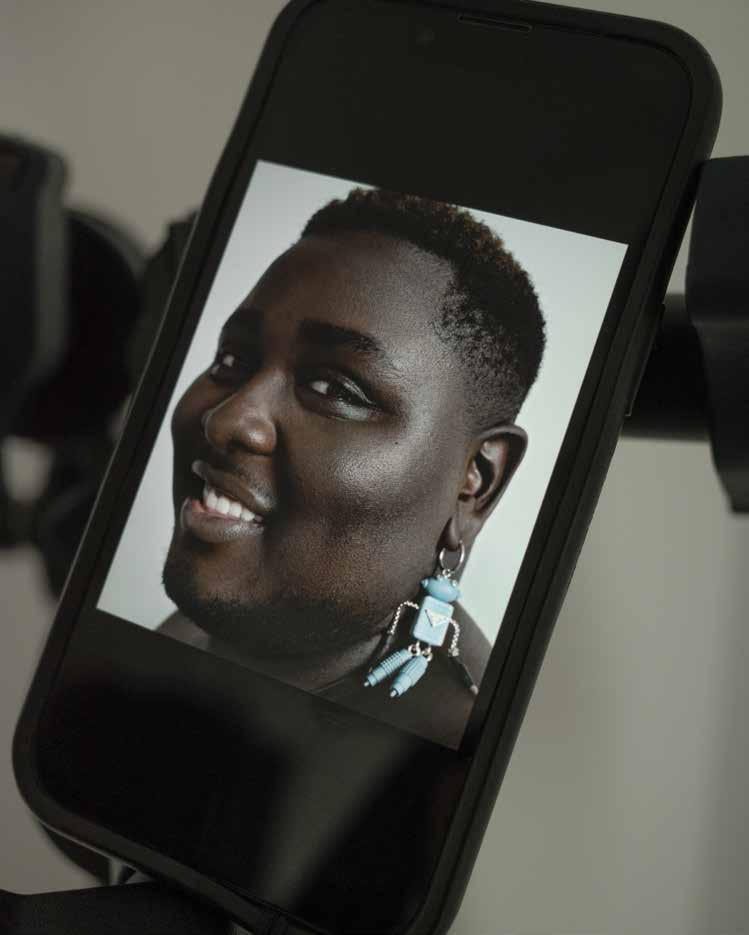

Stéphane Bak

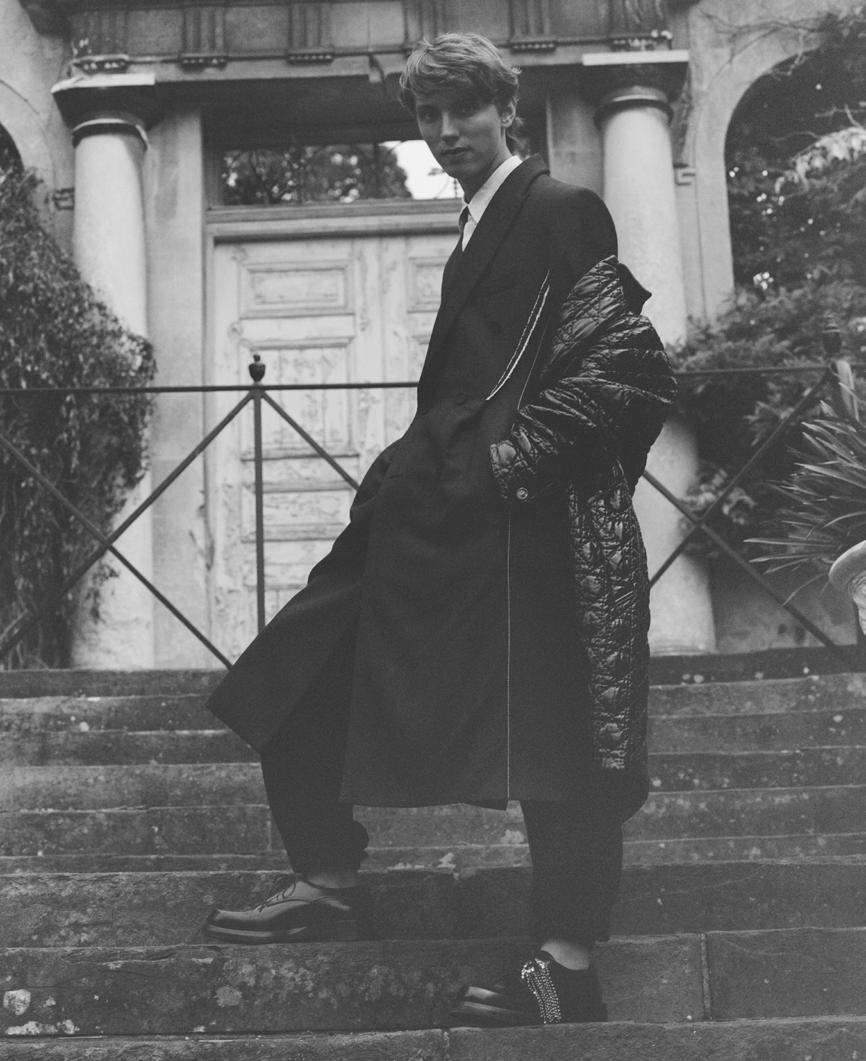

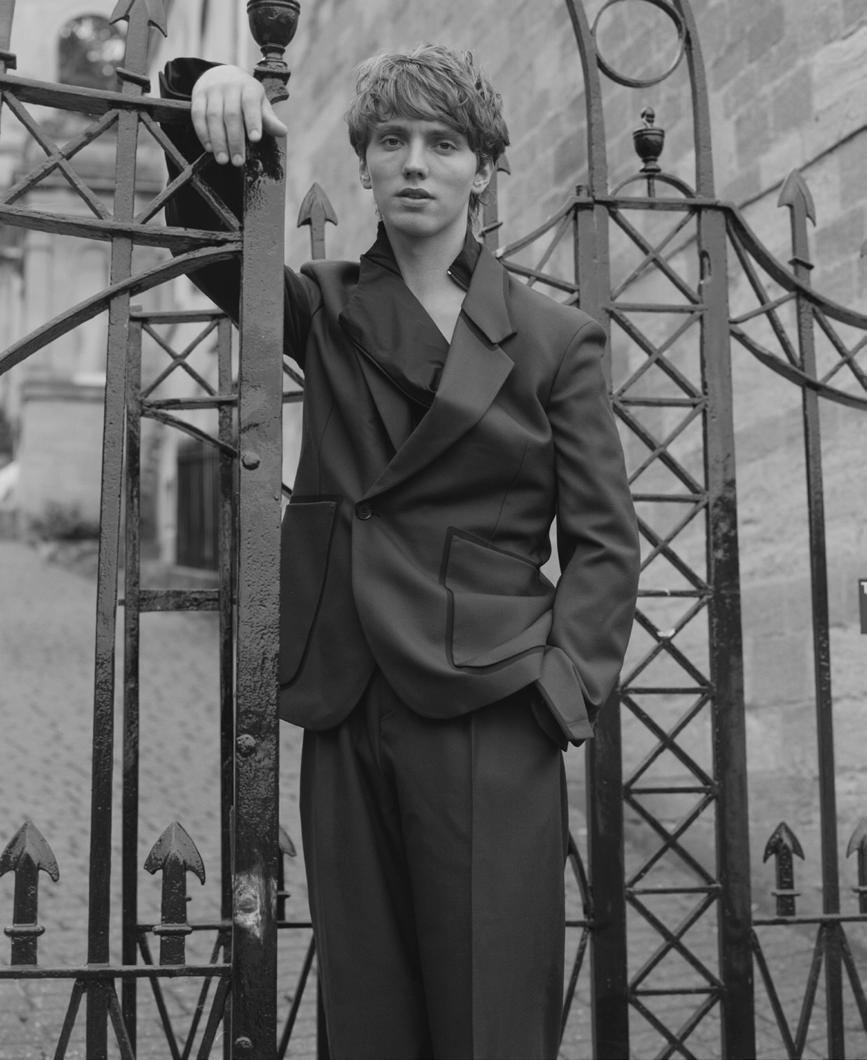

dior.com

dior.com

bebitalia.combebitalia.com

design Mario Bellinidesign Mario Bellini

design Mario Bellinidesign Mario Bellini

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Dan Crowe

DESIGN DIRECTOR Astrid Stavro

FASHION DIRECTOR Mitchell Belk

DEPUTY EDITOR Tom Bolger

FASHION EDITOR Julie Velut

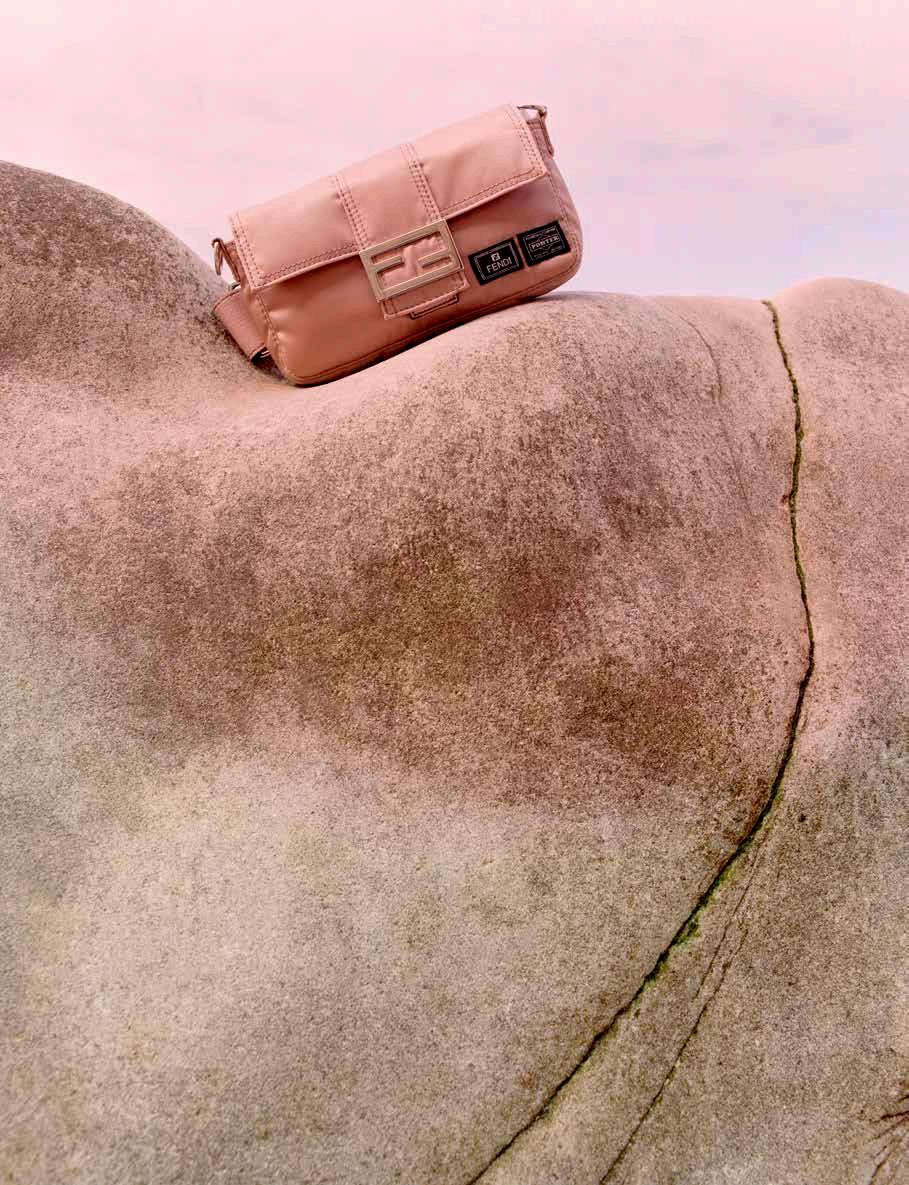

ACCESSORIES EDITOR Lune Kuipers

DESIGN Astrid Stavro, Sophie Dutton, Alessandro Molent

ART EDITOR Sophie Dutton

PHOTOGRAPHIC DIRECTOR Rachel Louise Brown

JUNIOR PHOTO EDITOR Jodie Michaelides

SENIOR EDITOR Kerry Crowe

HOROLOGY EDITOR Alex Doak

INTERIORS EDITORS Huw Griffith, Tobias Harvey

SUB-EDITOR Sarah Kathryn Cleaver

EU CORRESPONDENT Donald Morrison

US CORRESPONDENT Alex Vadukul

JAPANESE CORRESPONDENT Ryo Yamazaki

WORDS

Simran Hans, Michael Cera, Antonio Ortuño, Torrey Peters, Leila Mottley, Will Sharpe, Aleks

Cvetkovic, Tara Joshi, Elizabeth Fullerton, Tom Bolger, Ethan Price, Billie Muraben, Hannah Williams, Rion Amilcar Scott, Philip Hoare, Deyan Sudjic, Alex Doak, Laura McCreddie-Doak, Nabil Al-Kinani, Jeanette Winterson, Orhan Pamuk, Anthony Anaxagorou, Steven Pinker, Dylan Holden, Chloe Sells, Andrew Edmunds

PHOTOGRAPHY

Anatheine, Clément Pascal, Mitch Zachary, Hugo Mapelli, Eric Chakeen, Scott Gallagher, Arno Frugier, Sabine Hess, Megan Mechelle Dalton, Sacha Bowling, Benjamin McMahon, Pablo Escudero, Rachel Gordon, Gaëtan Bernède, Nola Minolfi, Thomas Martin, Pat Martin, Howard Sooley, Jonathan Baron, Stefan Armbruster, Iringó Demeter, Olya Oleinic, Cornelius Käss, Grace Difford, Thomas Rousset, Nicolas Kern, Valentin Hennequin, Benjamin Swanson, Leandro Farina, Phil Dunlop, John Gribben, Baker & Evans

ARTWORK

Chloe Sells, Frank Bowling, Nick Drnaso, Salvatore Fiorello

HEADLINE TYPEFACE

A2 Record Gothic by A2-Type (A2/SW/HK) www.a2-type.co.uk

“The living is merely a type of what is dead, and a very rare type.”

SENIOR EDITORS

Dan May, Fashion

Samantha Morton, Film

Hans Ulrich Obrist, Art Rick Moody, Literature

John-Paul Pryor, Music Brett Steele, Architecture

Deyan Sudjic, Design

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Kabir Chibber

Robert Macfarlane Albert Scardino

SPECIAL THANKS

The Production Factory Everyone who has ever worked at, or with, Port

COVER CREDITS

Kieran Culkin, photographed in New York by Clément Pascal, wears ANEST COLLECTIVE AW22

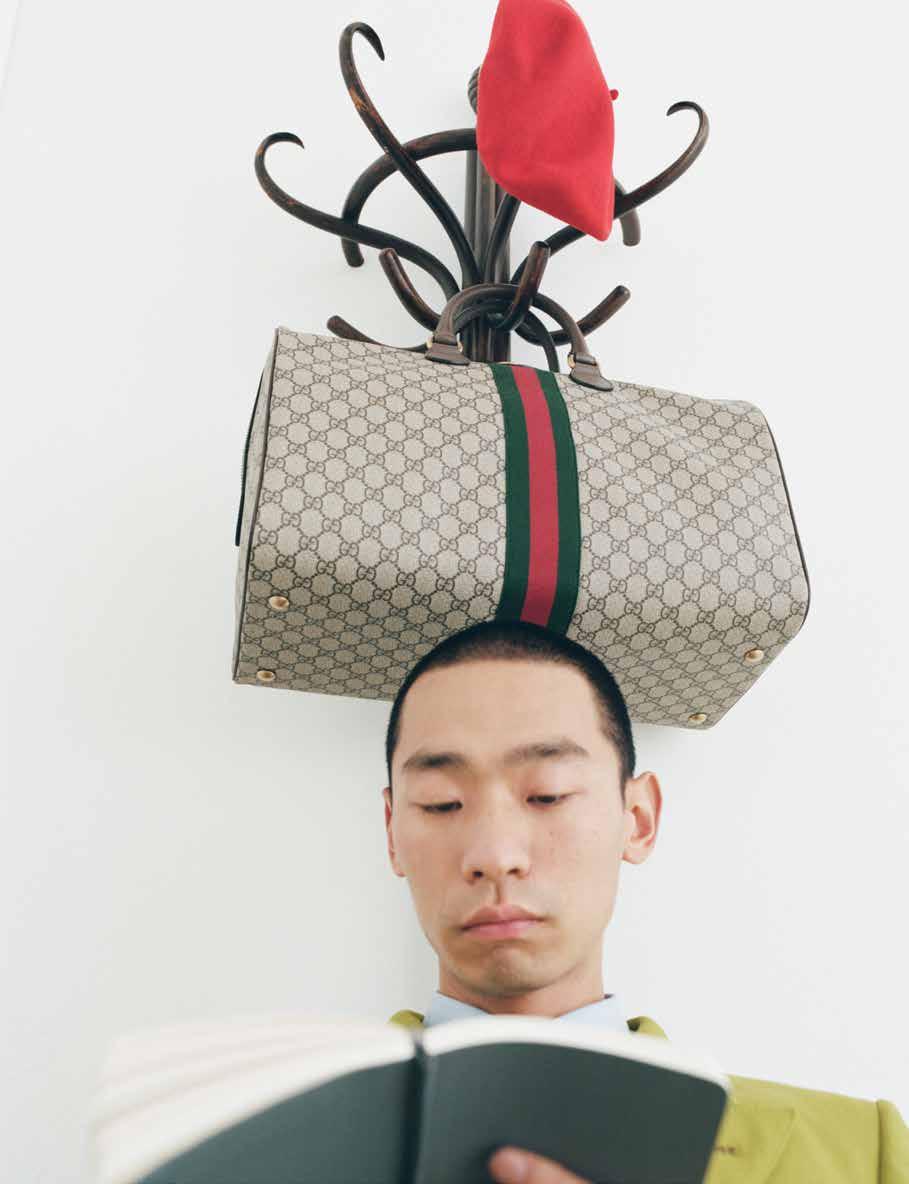

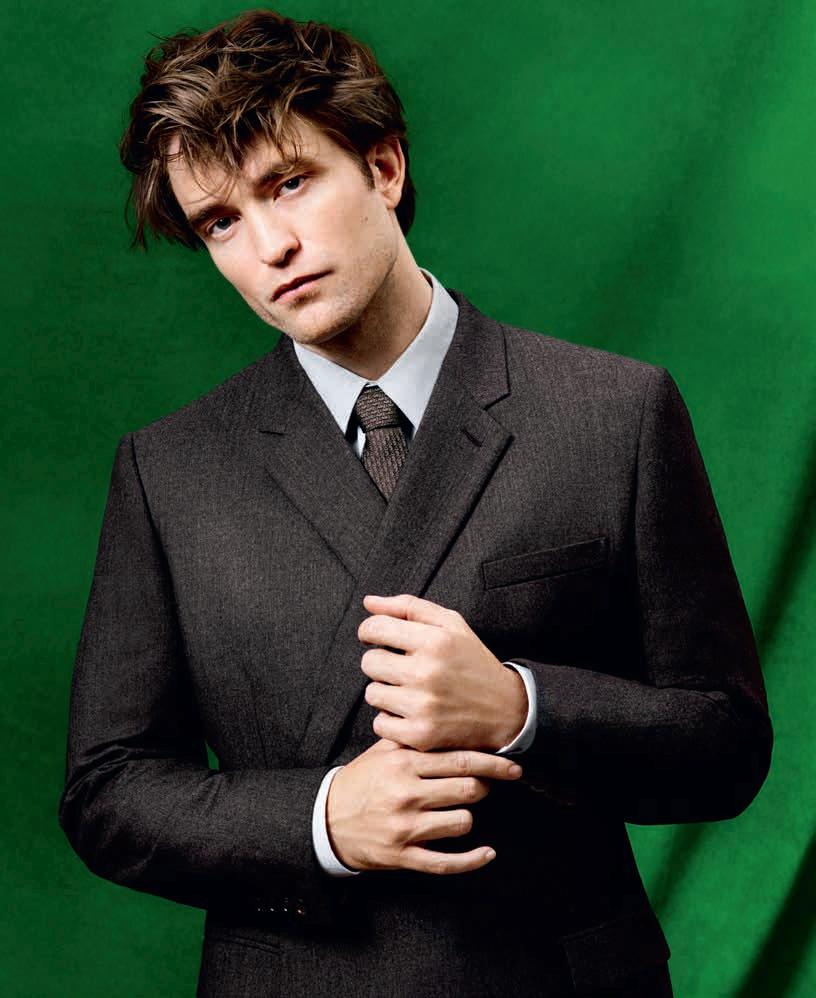

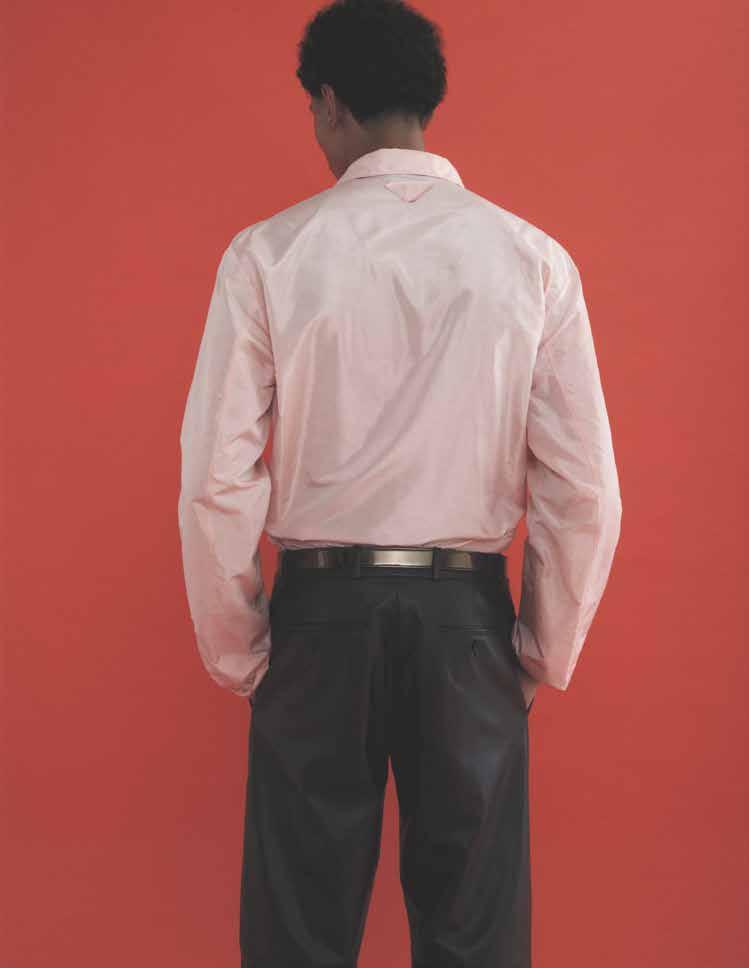

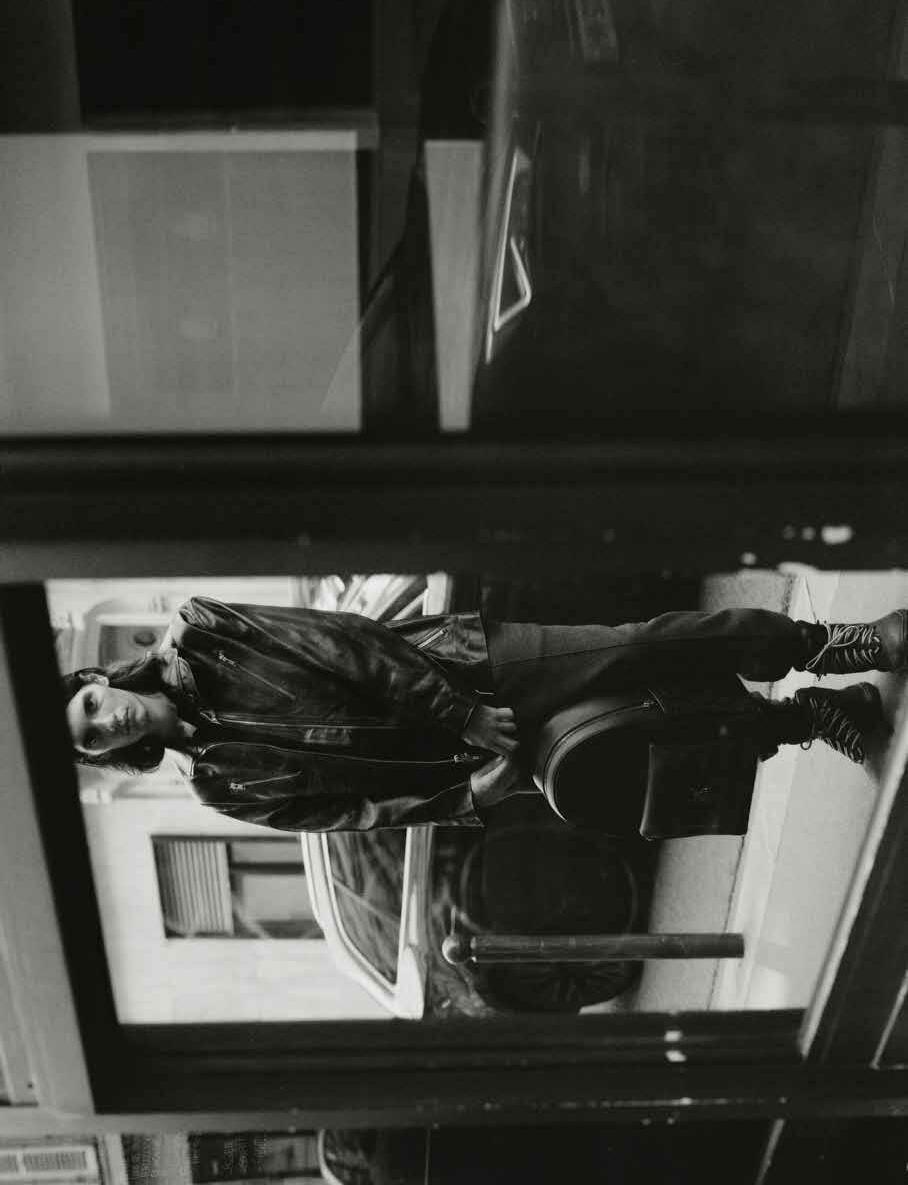

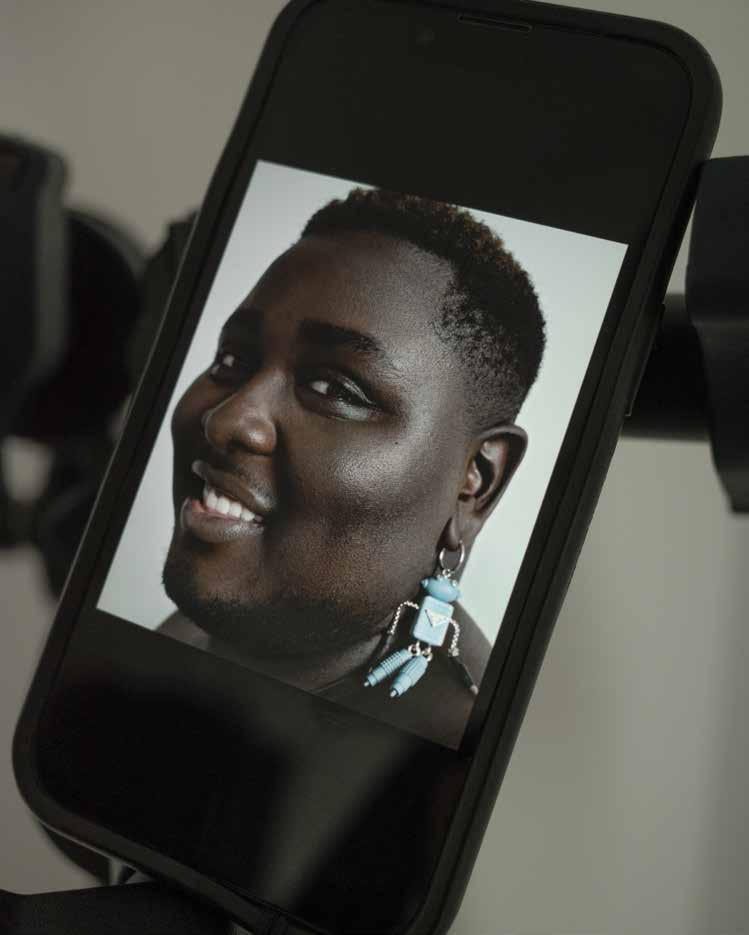

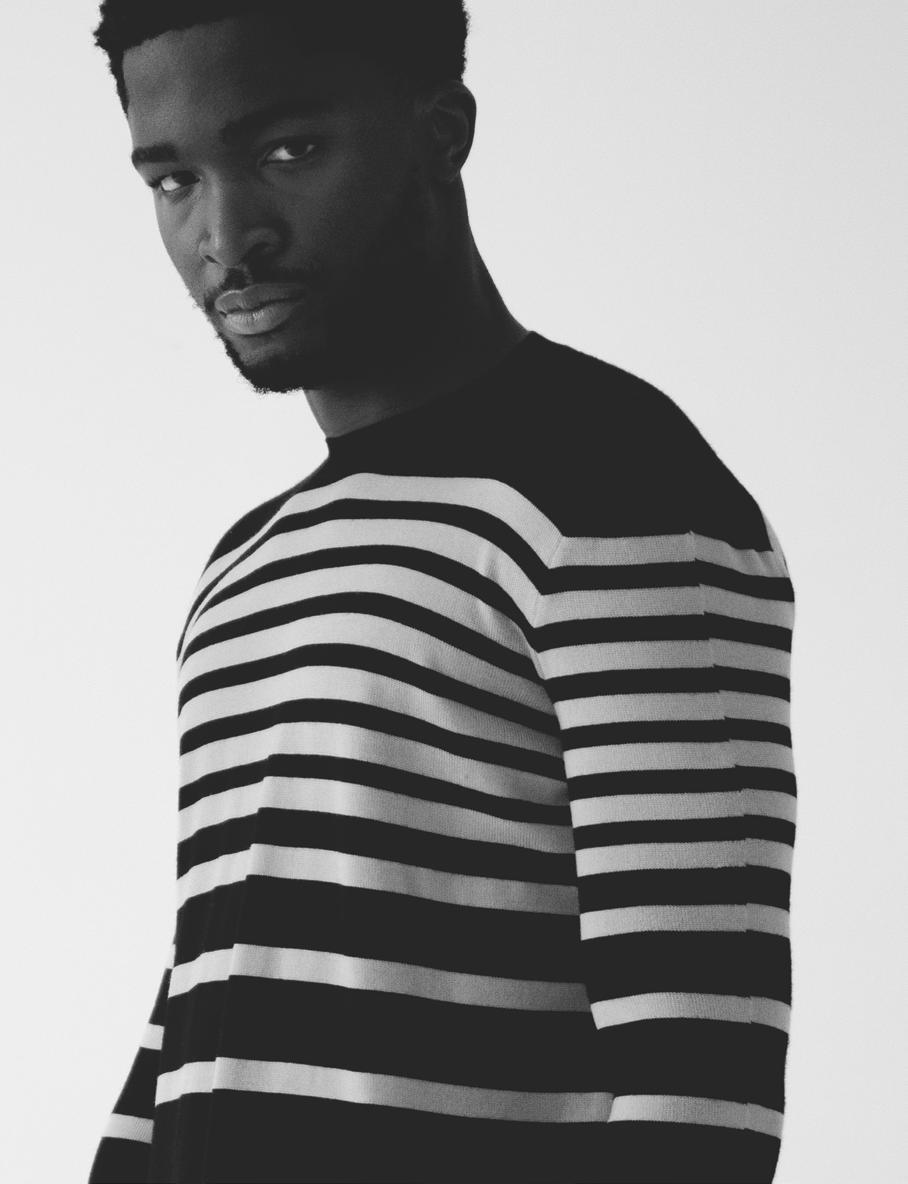

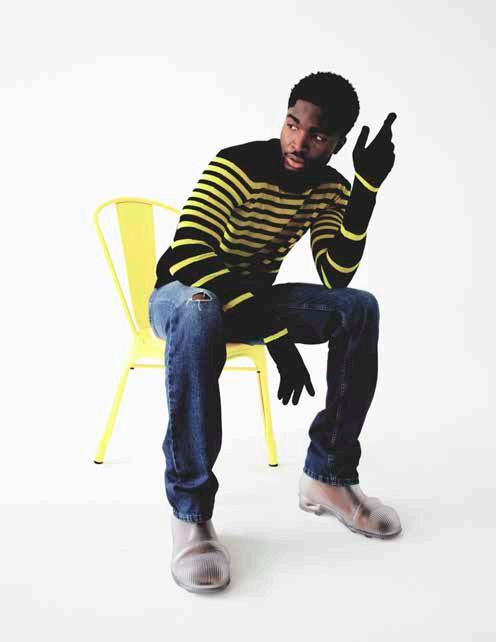

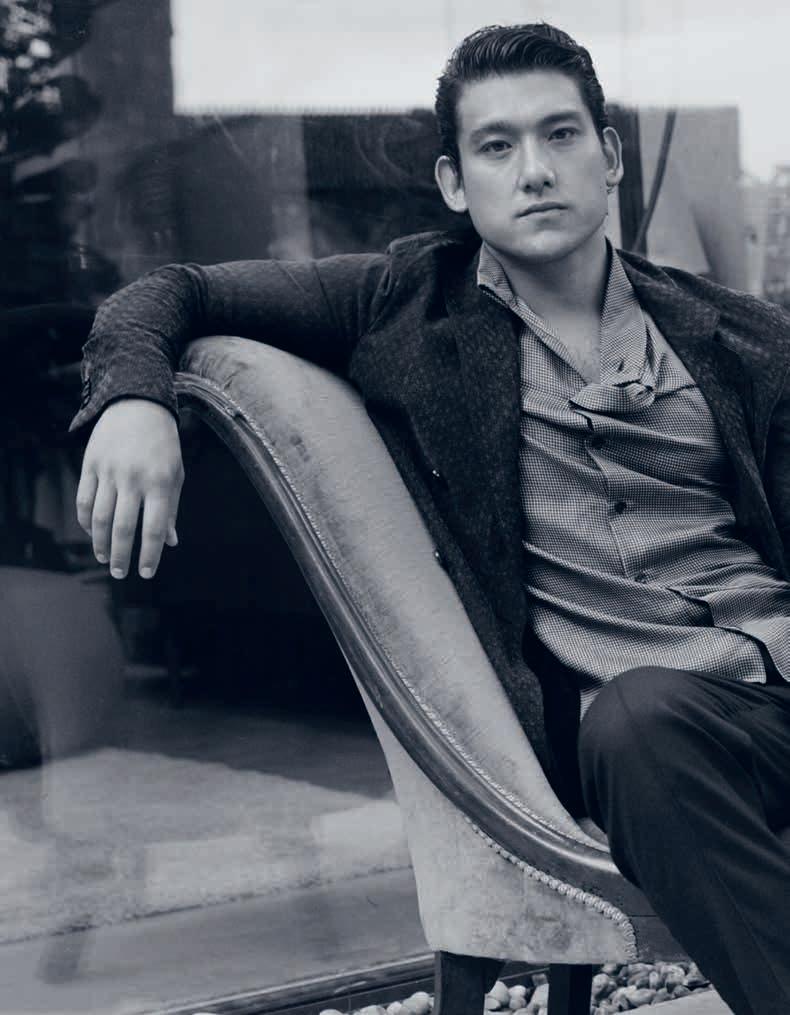

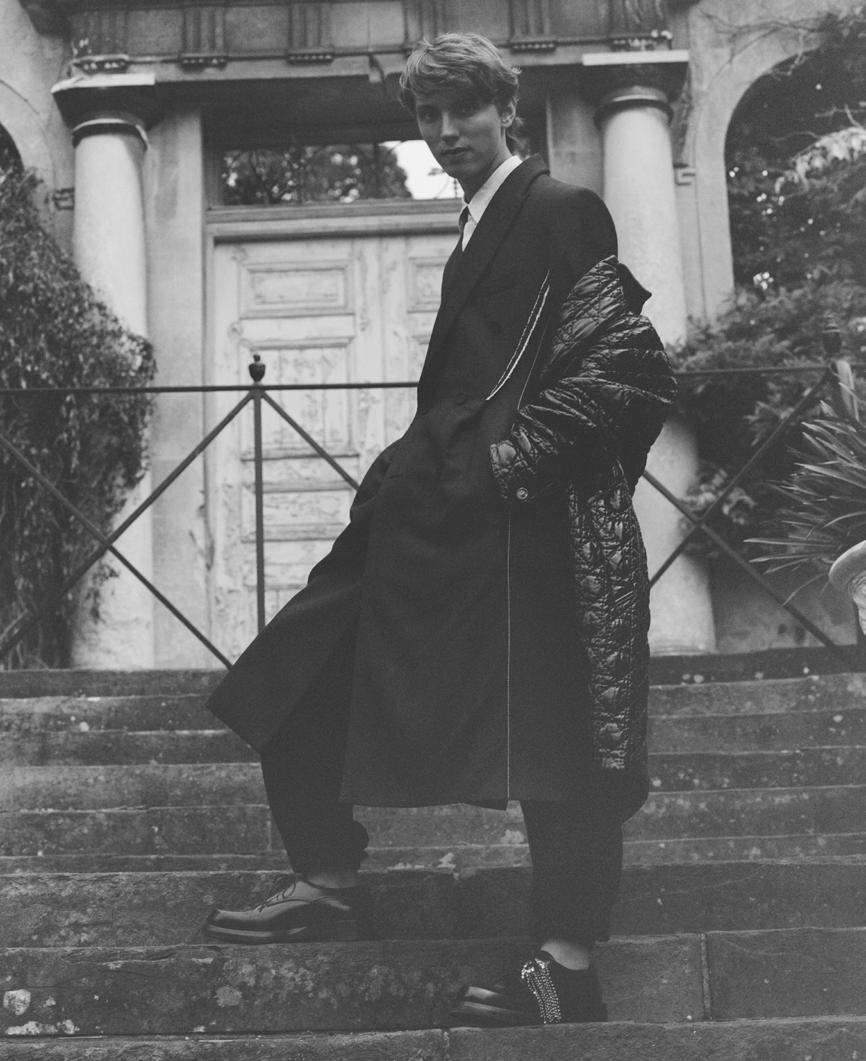

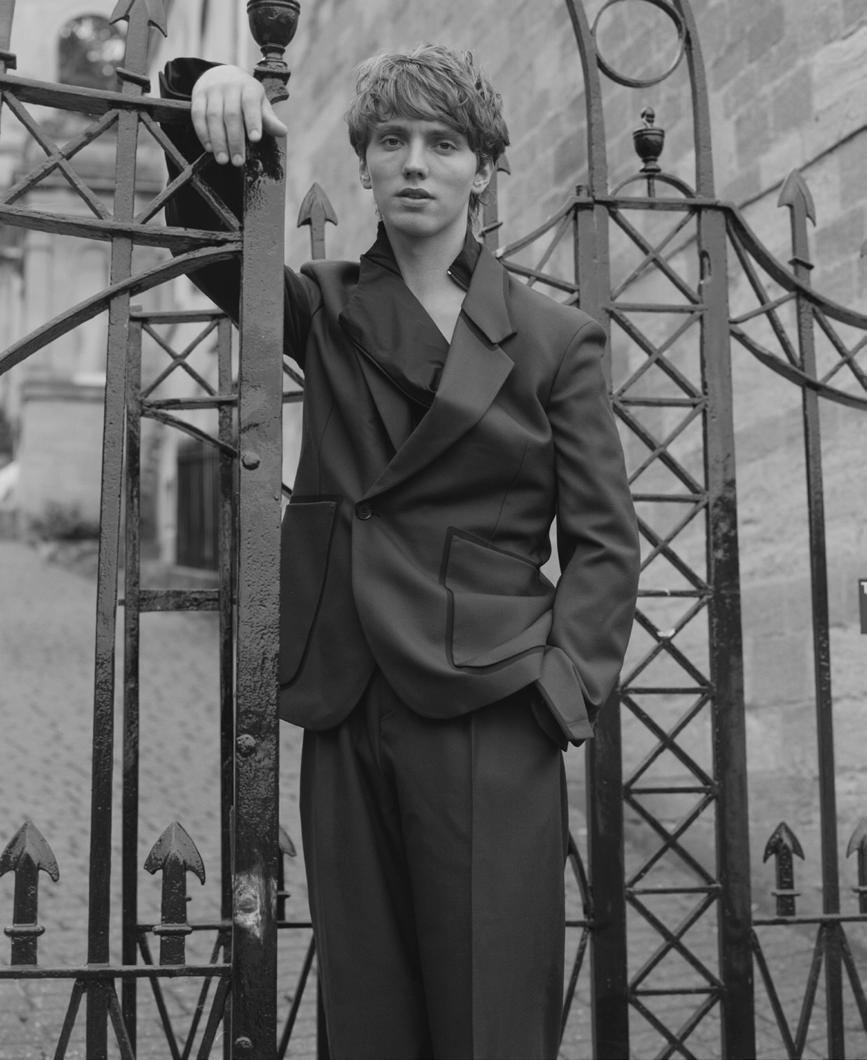

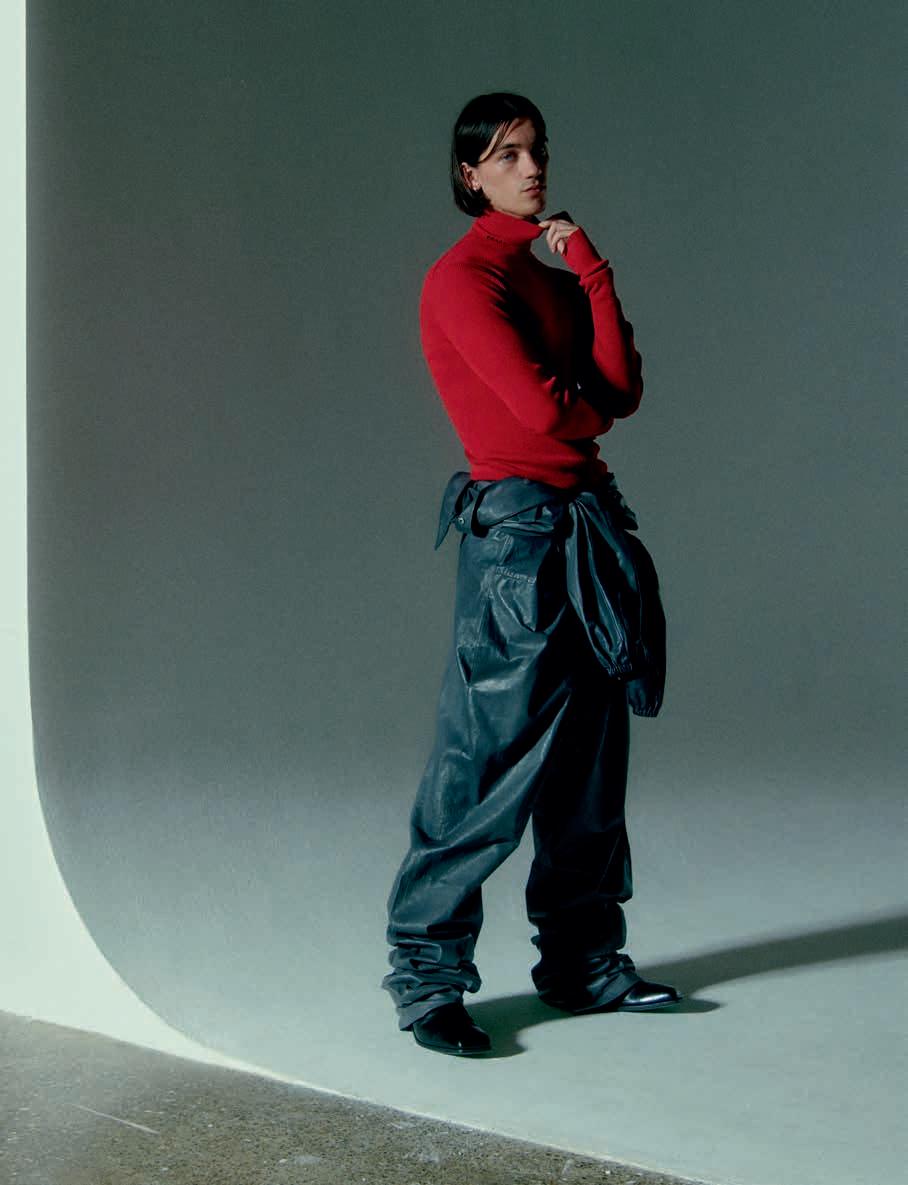

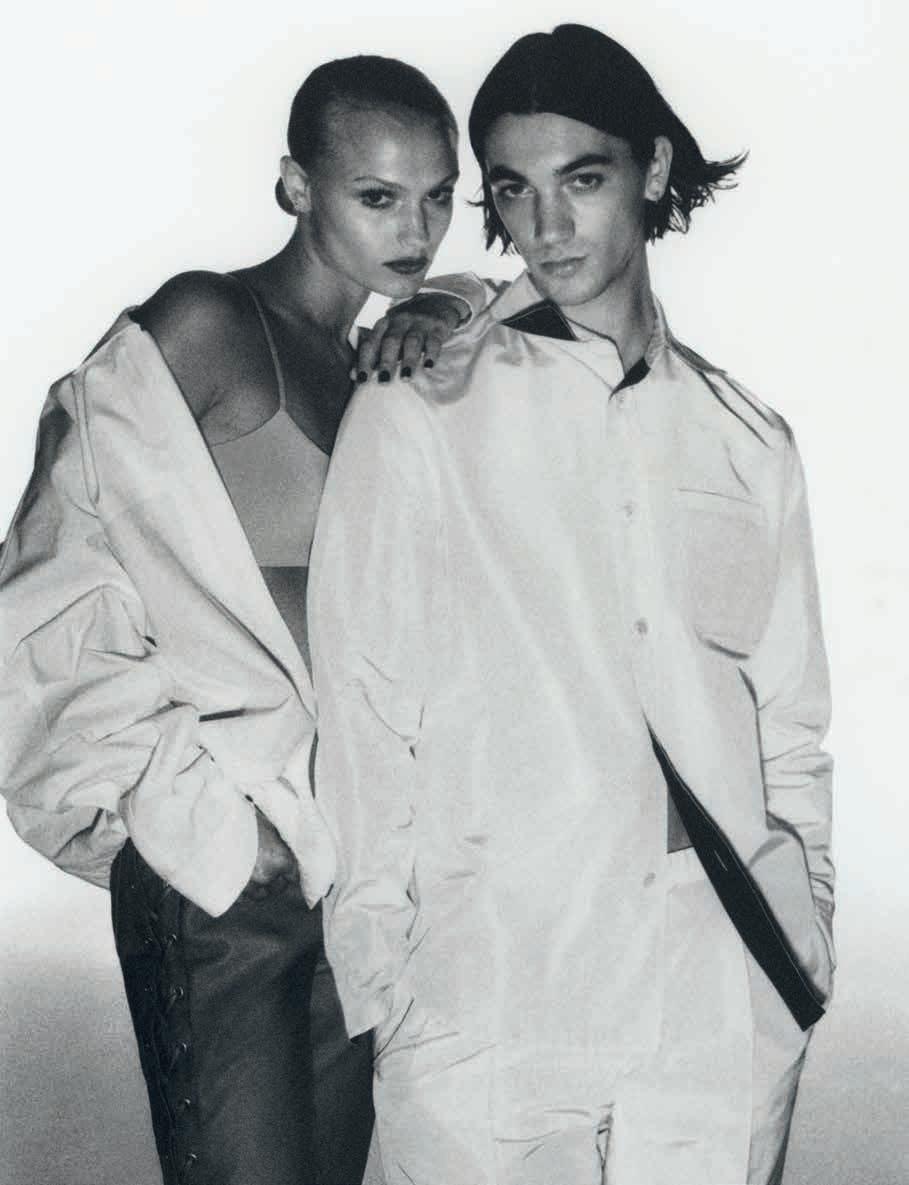

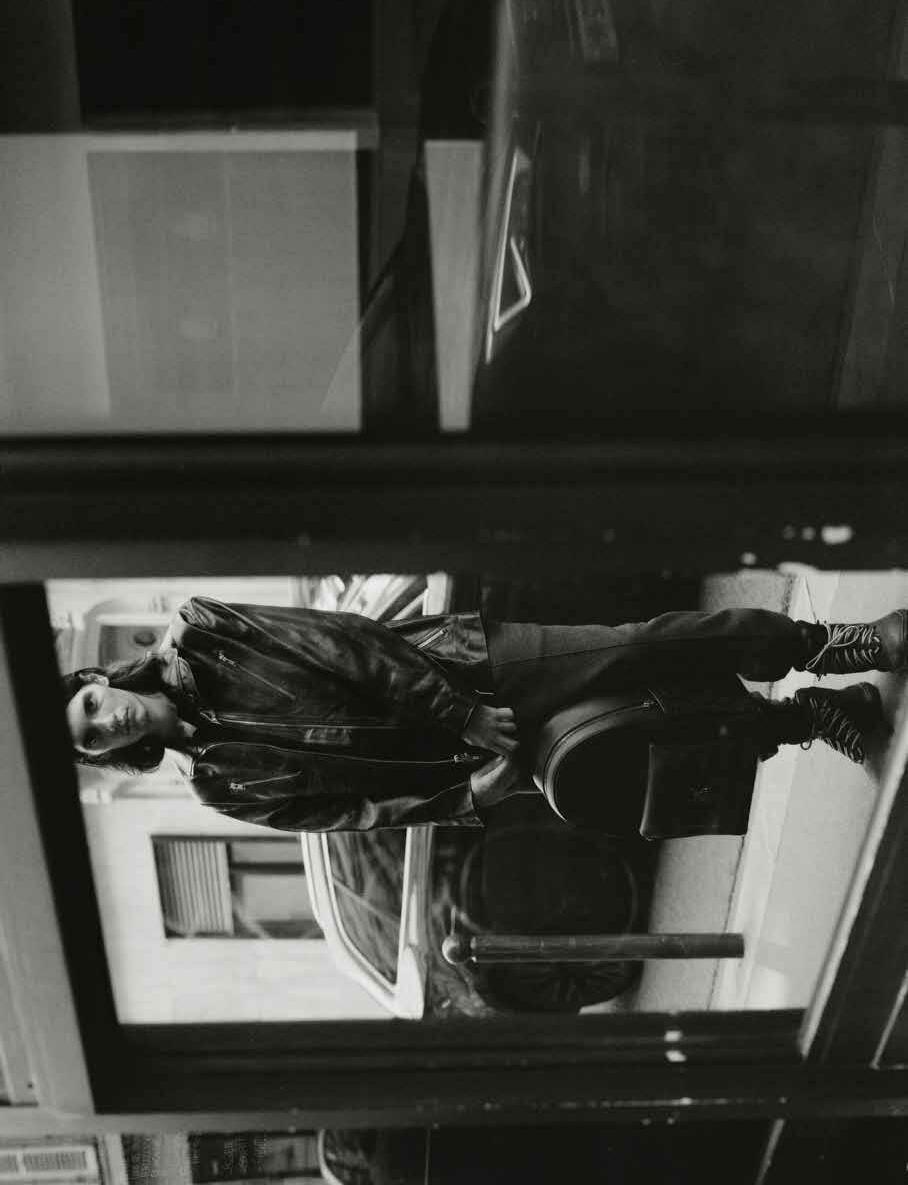

Stéphane Bak, photographed in Paris by Anatheine, wears LOEWE

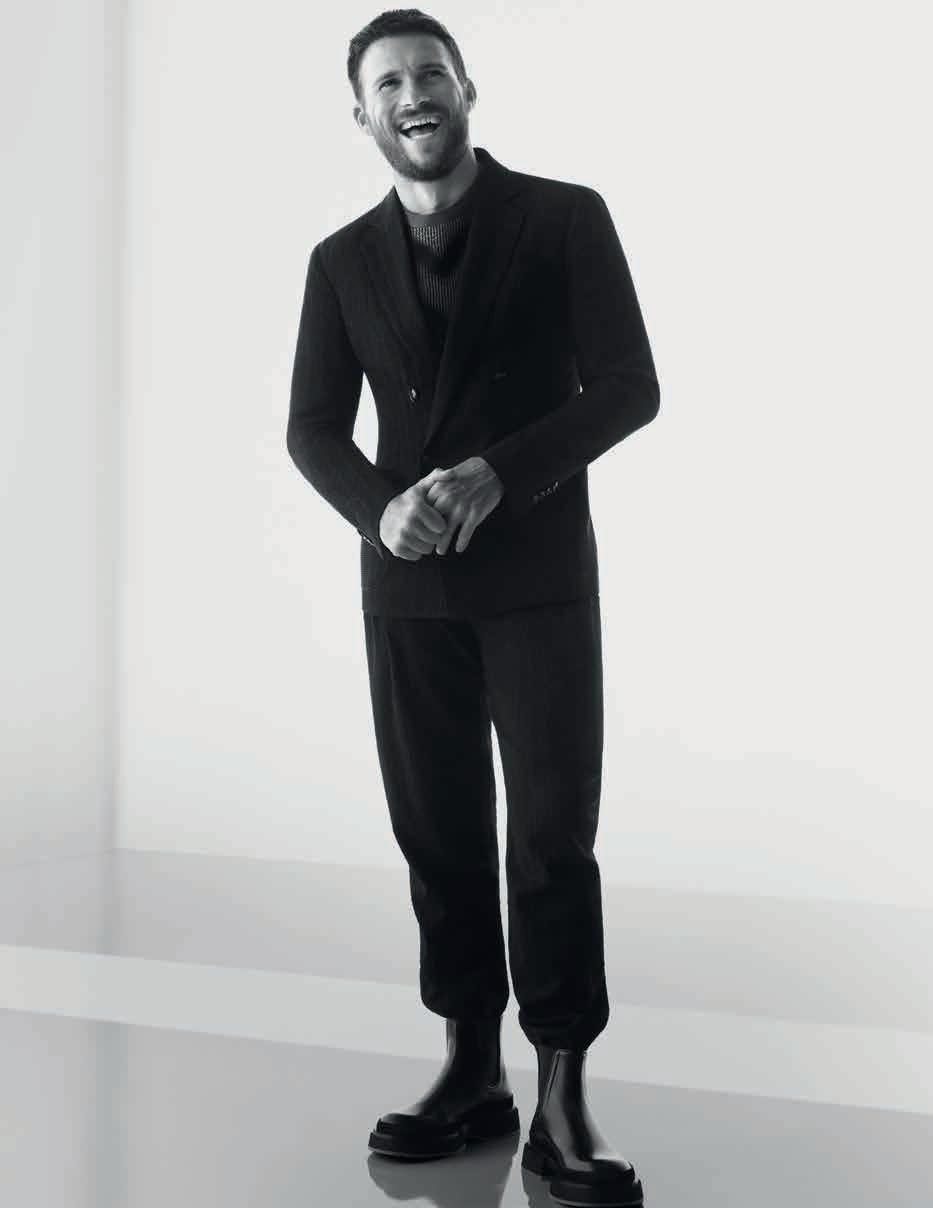

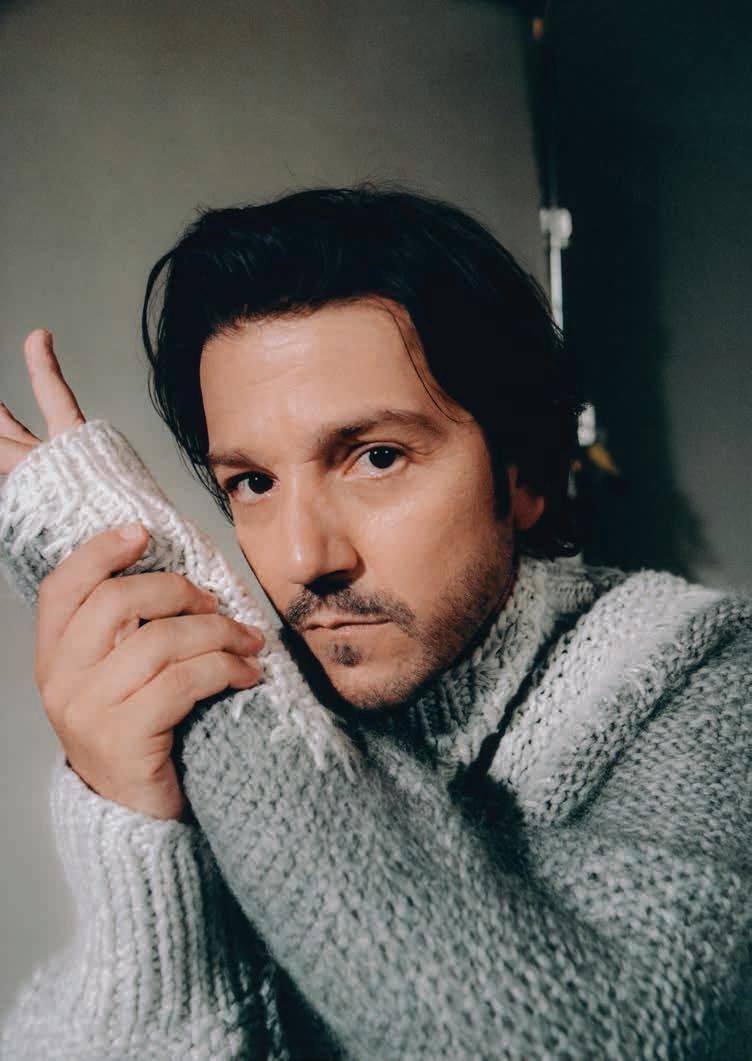

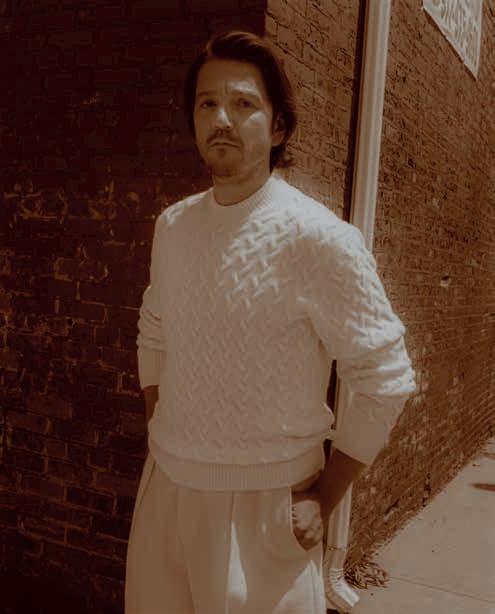

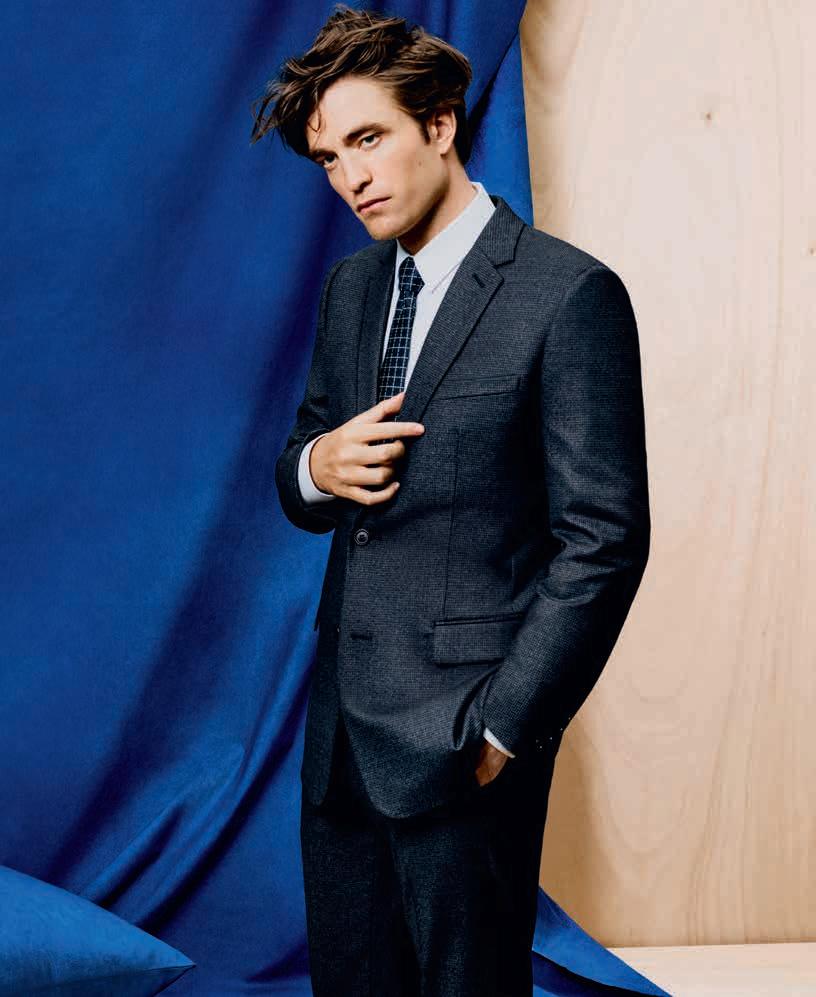

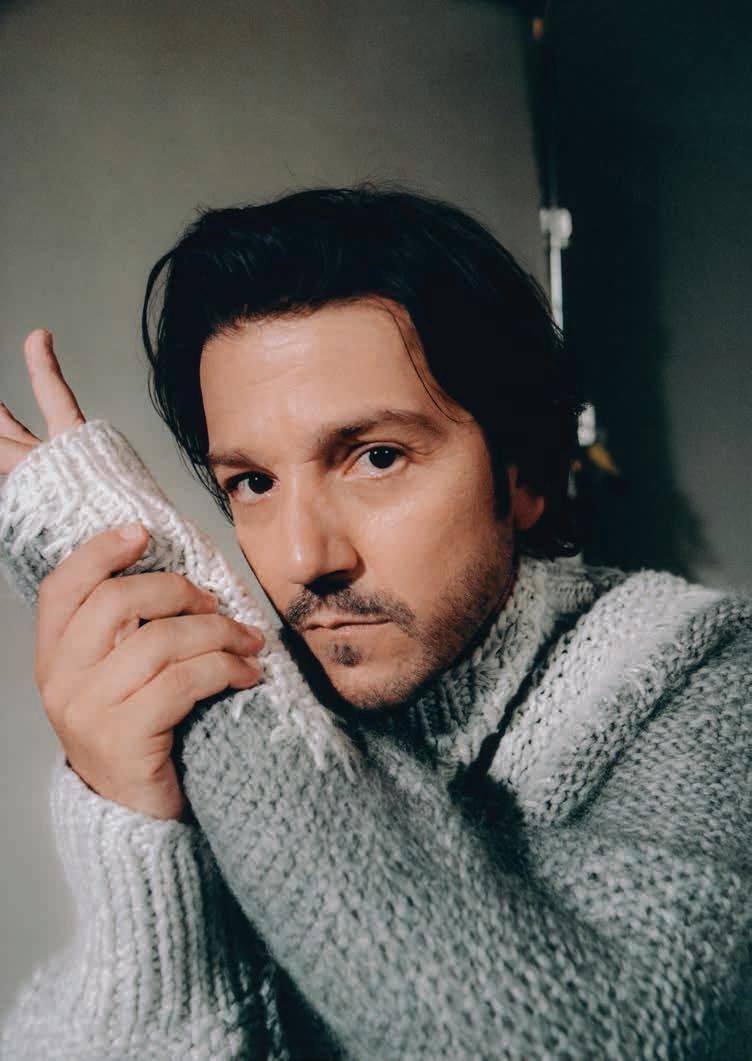

Diego Luna, photographed in New York by Mitch Zachary, wears ZEGNA AW22

Torrey Peters, photographed in Vermont by Eric Chakeen, wears VALENTINO PINK PP FALL/WINTER 22-23 COLLECTION

Leila Mottley, photographed in Paris by Hugo Mapelli, wears VALENTINO PINK PP FALL/WINTER 22-23 COLLECTION

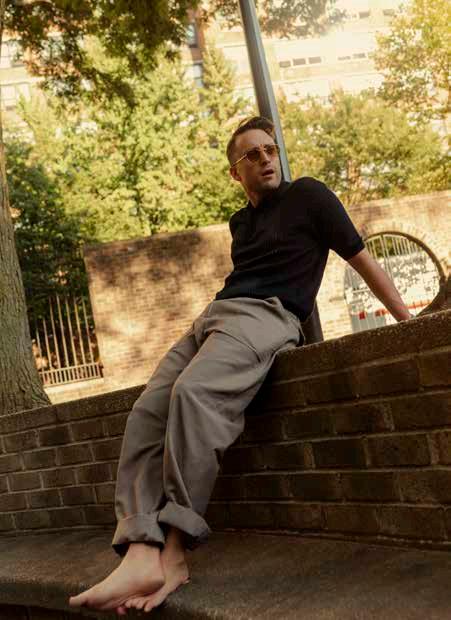

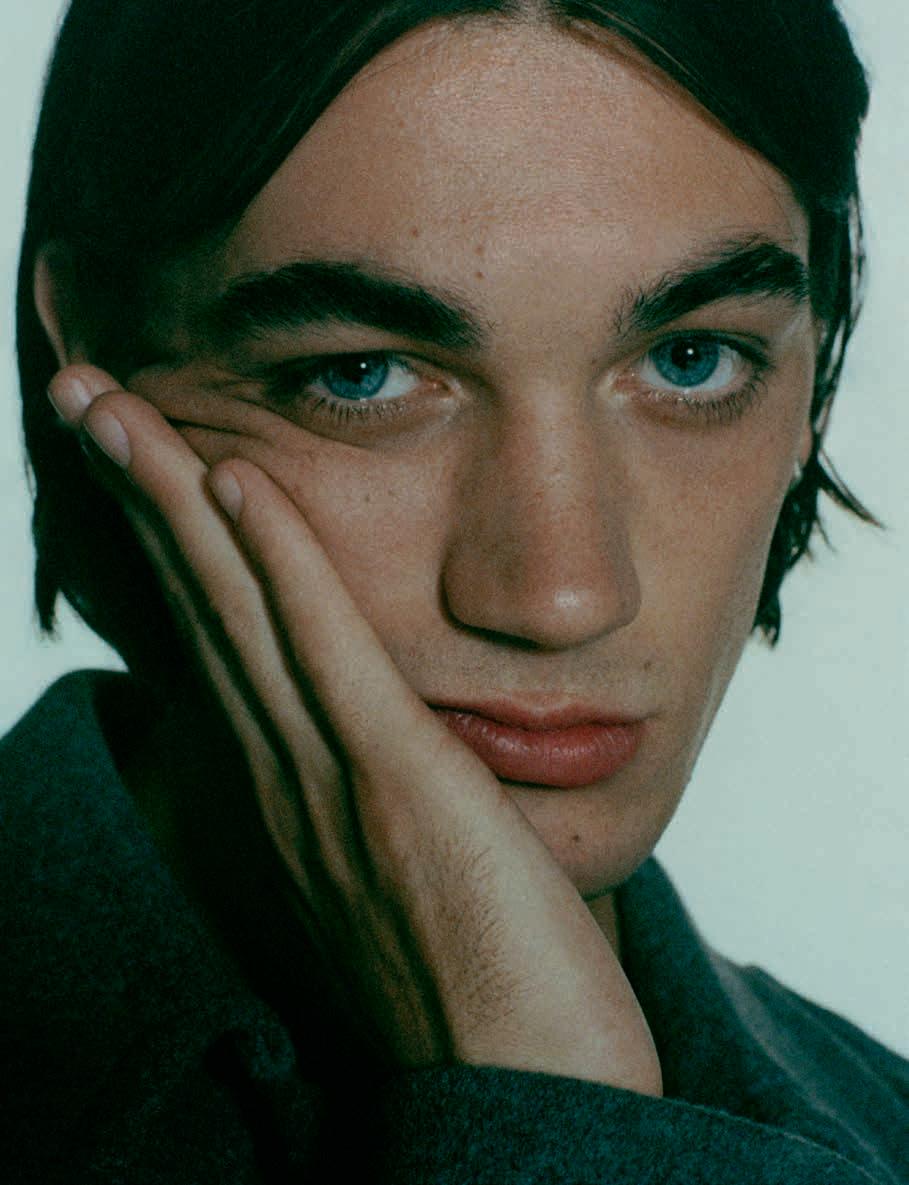

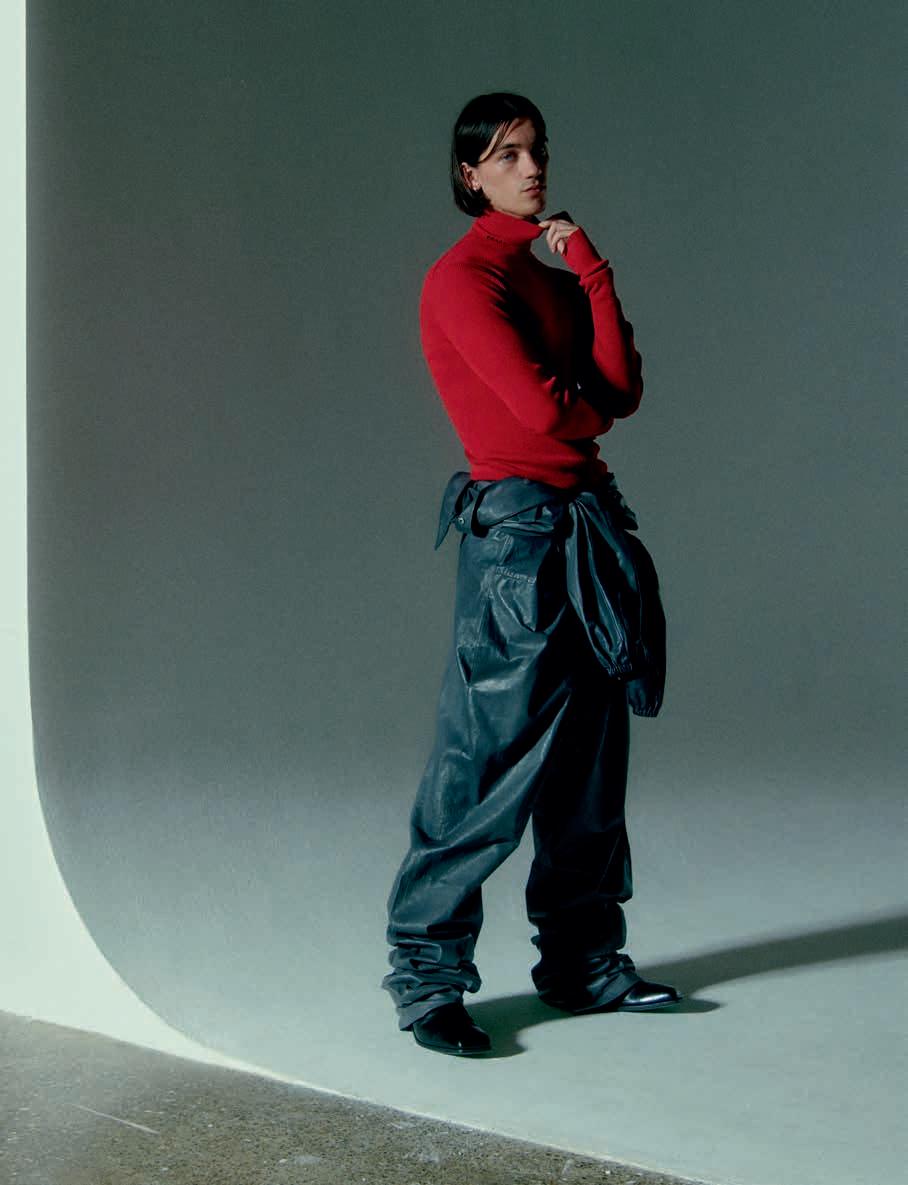

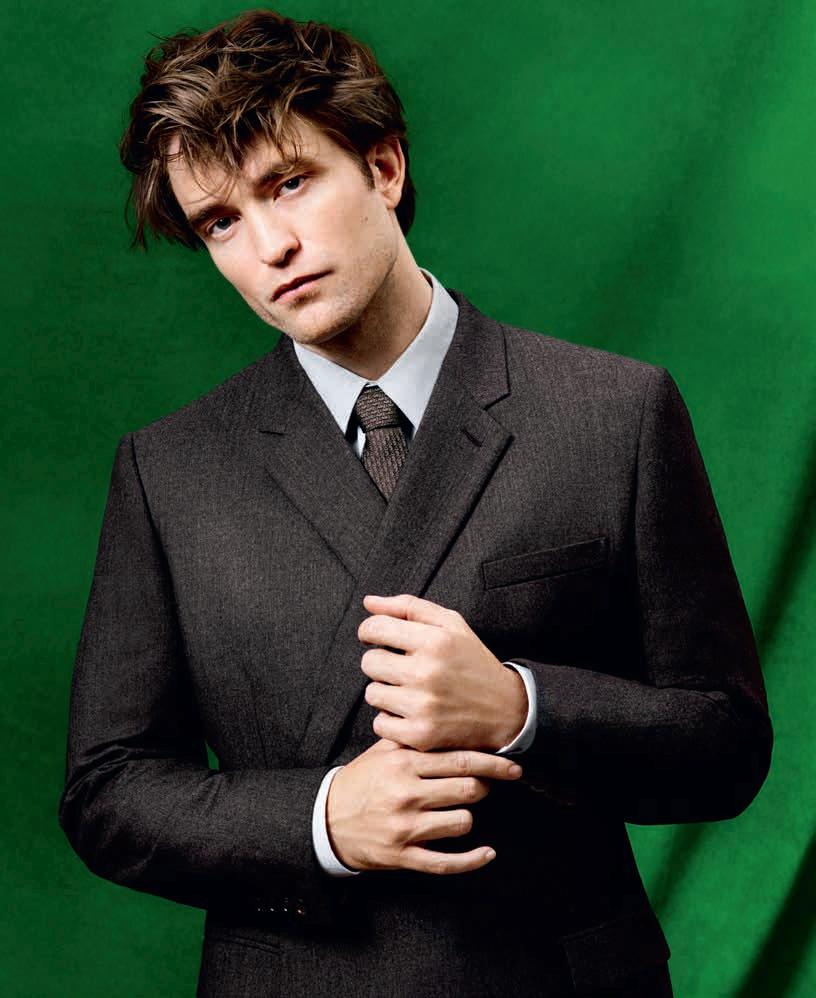

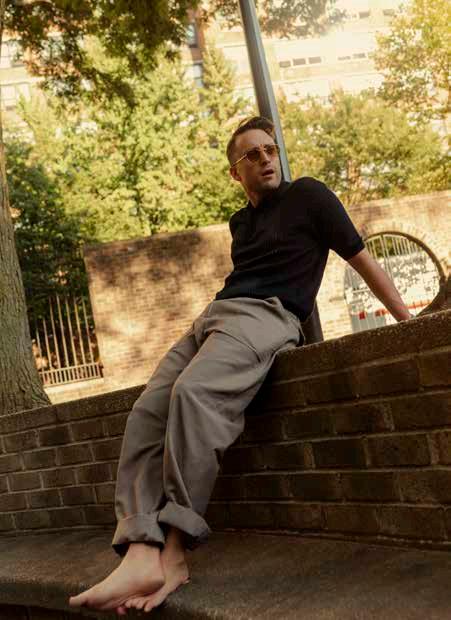

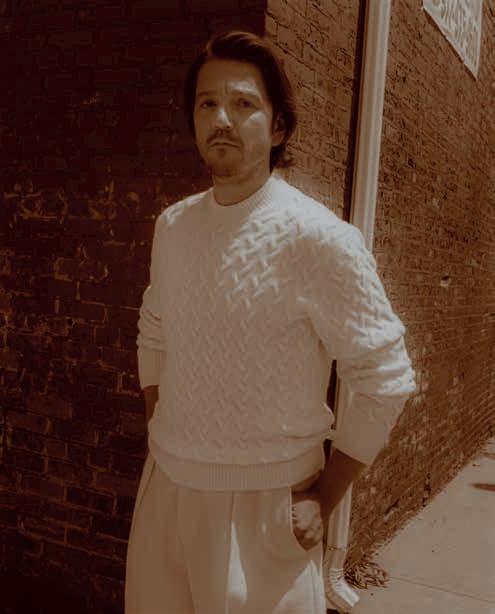

Will Sharpe, photographed in London by Arno Frugier, wears GIORGIO ARMANI AW22

PUBLISHERS

Dan Crowe, Matt Willey

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono

MANAGING DIRECTOR Dan Crowe

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono andrew@port-magazine.com

ACCOUNTS

Charlie Carne & Co.

CIRCULATION CONSULTANT

Logical Connections

Adam Long adam@logicalconnections.co.uk

CONTACT info@port-magazine.com

SYNDICATION syndication@port-magazine.com

SYNDICATED ISSUES

Port Spain portmagazine.es

Port Turkey port-magazine.com.tr issn 2046-052X

Port is published twice a year by Port Publishing Limited Somerset House Strand London WC2R 1LA port-magazine.com

Port is printed by Park Communications

Founded by Dan Crowe, Boris Stringer, Kuchar Swara and Matt Willey.

Registered in England no. 7328345

All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is strictly prohibited. All prices are correct at time of going to press but are subject to change. All paper used in the production of this magazine comes, as you would expect, from sustainable sources.

Friedrich Nietzsche

MASTHEAD

It’s a golden age for literature and the arts in general: never before have we had access to such staggering amounts of exciting new work, from all directions, and yet our actual global dramas also seem to be in creasing and unfolding at a similar pace... It’s hard to comprehend where we are at (are we collapsing as a global society? Are we about to hit rock bottom, bounce back and figure everything out?), and so for this issue, we decided to bring in the theme of ‘mirrors’ to explore self, reality and context. Somehow, reflected back to us through this subject, material gathered and got in line, as if urgently wanting to comment on the incredibly strange times we find ourselves living through: motherhood, fatherhood; the power of art to interrogate reality; home as a place of refuge, and working, from a young age, on a particular craft... All these concepts are considered from various po sitions over the following pages, from an astonishing array of talents.

Six phenomenal cover stars from the worlds of film, TV and literature front this issue of Port. Kieran Culkin catches up with

old friend and fellow actor Michael Cera to consider their craft and the unexpected joys of fatherhood, while best-selling author Torrey Peters has an in-depth conversation with Booker-longlisted writer Leila Mottley on the incredible power of fiction. Mexican actor Diego Luna discusses with compa triot novelist Antonio Ortuño his determi nation to keep producing vital stories in their home country (whilst also being the lead in the new Star Wars saga Andor); and rising French actor Stéphane Bak reflects on the beauty of the diasporic stories he embodies. Finally, BAFTA Award-winning writer, director and actor Will Sharpe writes a letter to writing itself: the solace, pain and belonging it has brought him from childhood, and where it might take him next. It’s incredibly charming and beautiful. Elsewhere, historian and biographer Philip Hoare pens a sublime ode to Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage (paired with gorgeous photographs from Jarman’s friend and collaborator Howard Sooley), a place which remains somewhat out of time, yet still talks to us: “Prospect Cottage

was created for Derek Jarman a hundred years before he arrived. It was waiting for him, like a UFO. The tarry fisherman’s cot tage stood naked and alone at Dungeness, surrounded by a dozen or more like it, in their varying shapes and sizes, facing out to the English Channel. This beach was the last of England, the fifth quarter, since it was new land, stolen from the sea. It now receives refugees. You might say Jarman was one of them...”

Alongside our seventh annual supple ment devoted to horology, 10:10, we have also photographed autumn/winter collections and accessories the world over. It would be hard to deny that this is some of the finest styling and fashion photography we have ever produced, accompanied by some of the best writing. The entire issue reflects clearly the hard work and brilliance of those who contributed to it, as well as the beau ty, wonder and mystery of our dauntingly complex world. As a good mirror should.

— Dan Crowe

EDITOR’S LETTER

45 90

102 114 134

Portfolio

Aleks Cvetkovic, Tara Joshi, Elizabeth Fullerton, Tom Bolger, Dylan Holden, Ethan Price, Billie Muraben, Hannah Williams, Chloe Sells, Andrew Edmunds

Stéphane Bak Words Simran Hans Photography Anatheine

Kieran Culkin

Words

Michael

Cera Photography Clément

Pascal

Diego Luna

Words Antonio Ortuño Photography Mitch Zachary

Torrey Peters & Leila Mottley Photography Eric Chakeen & Hugo Mapelli

CONTENTS

146

173

PORT 31

154

232

George Saunders: Still Evolving

Words Rion Amilcar Scott Photography Pat Martin

The Last of England Words Philip Hoare Photography Howard Sooley

Commentary

Will Sharpe, Jeanette Winterson, Nabil Al-Kinani, Orhan Pamuk, Anthony Anaxagorou

Split Screen

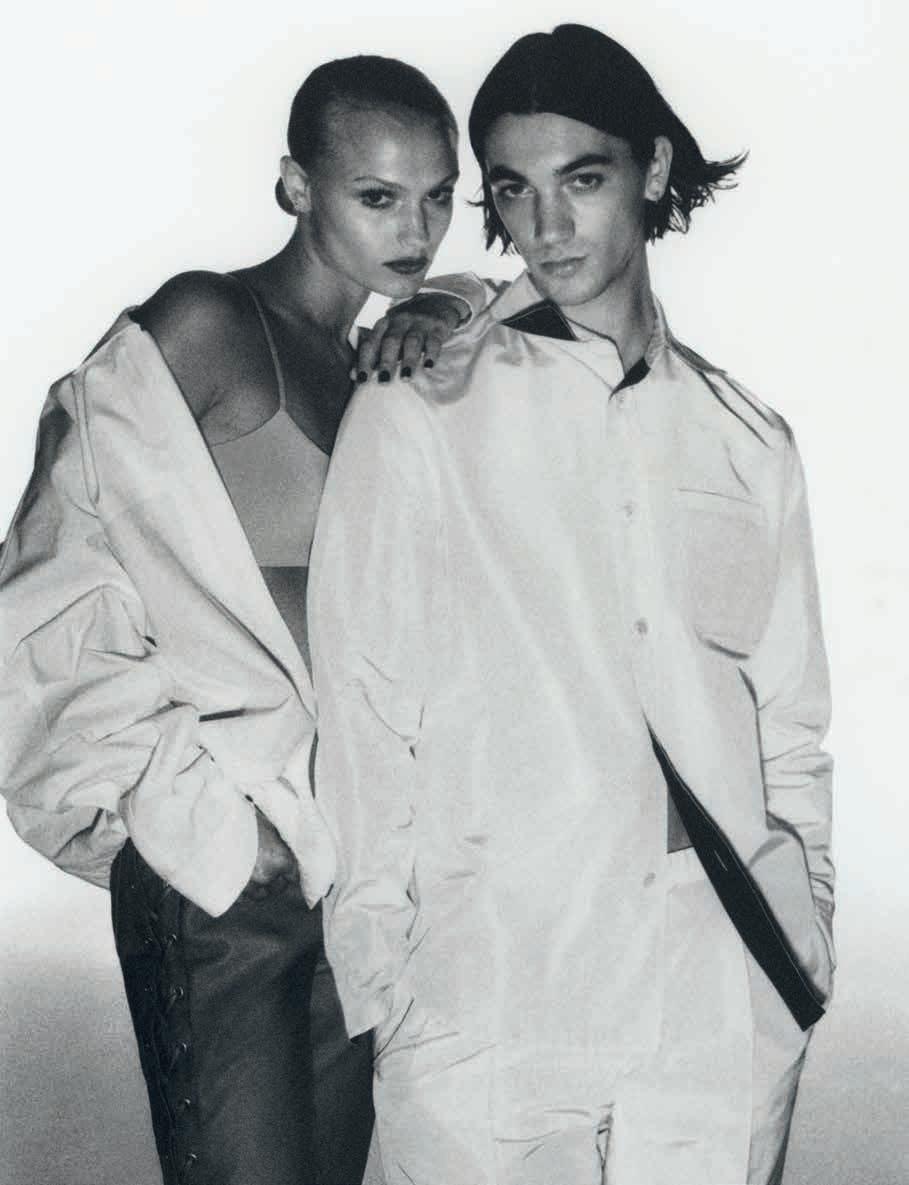

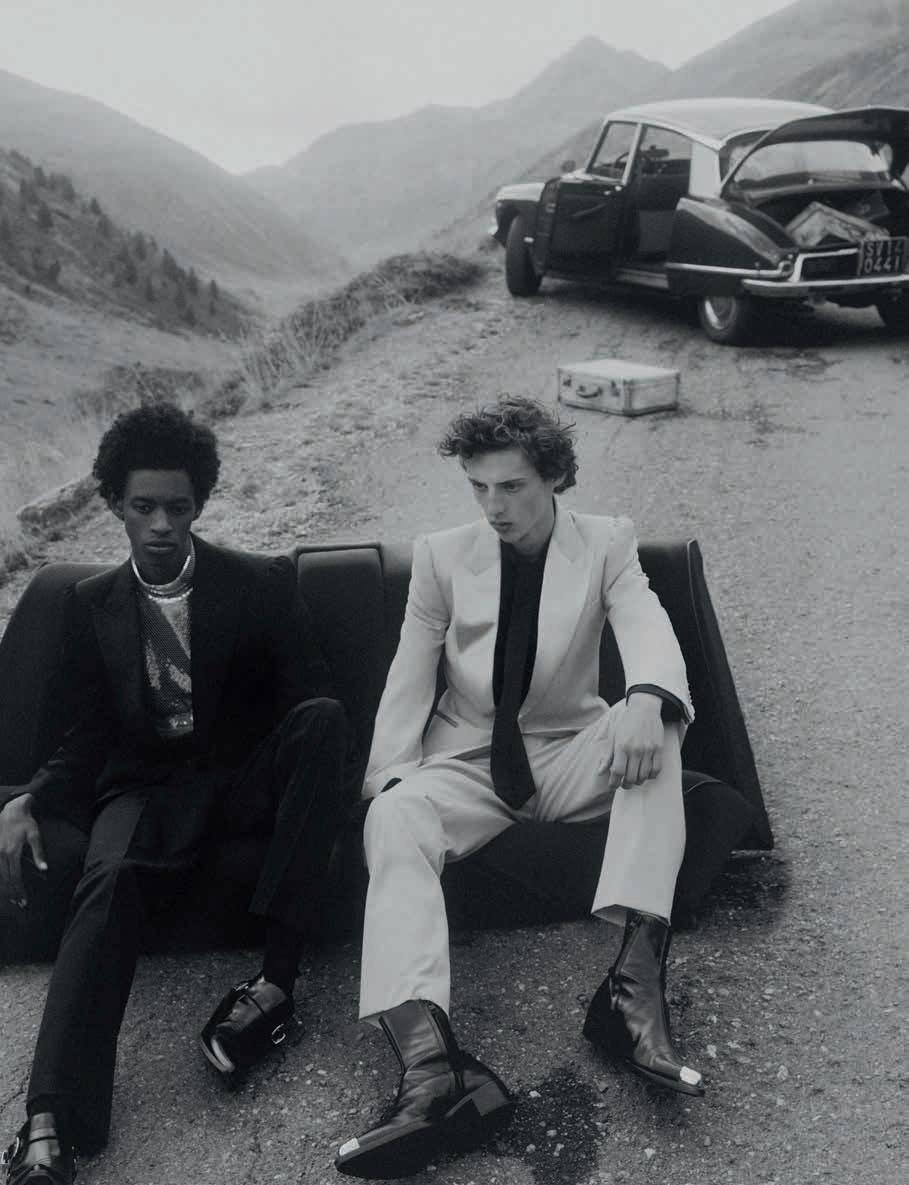

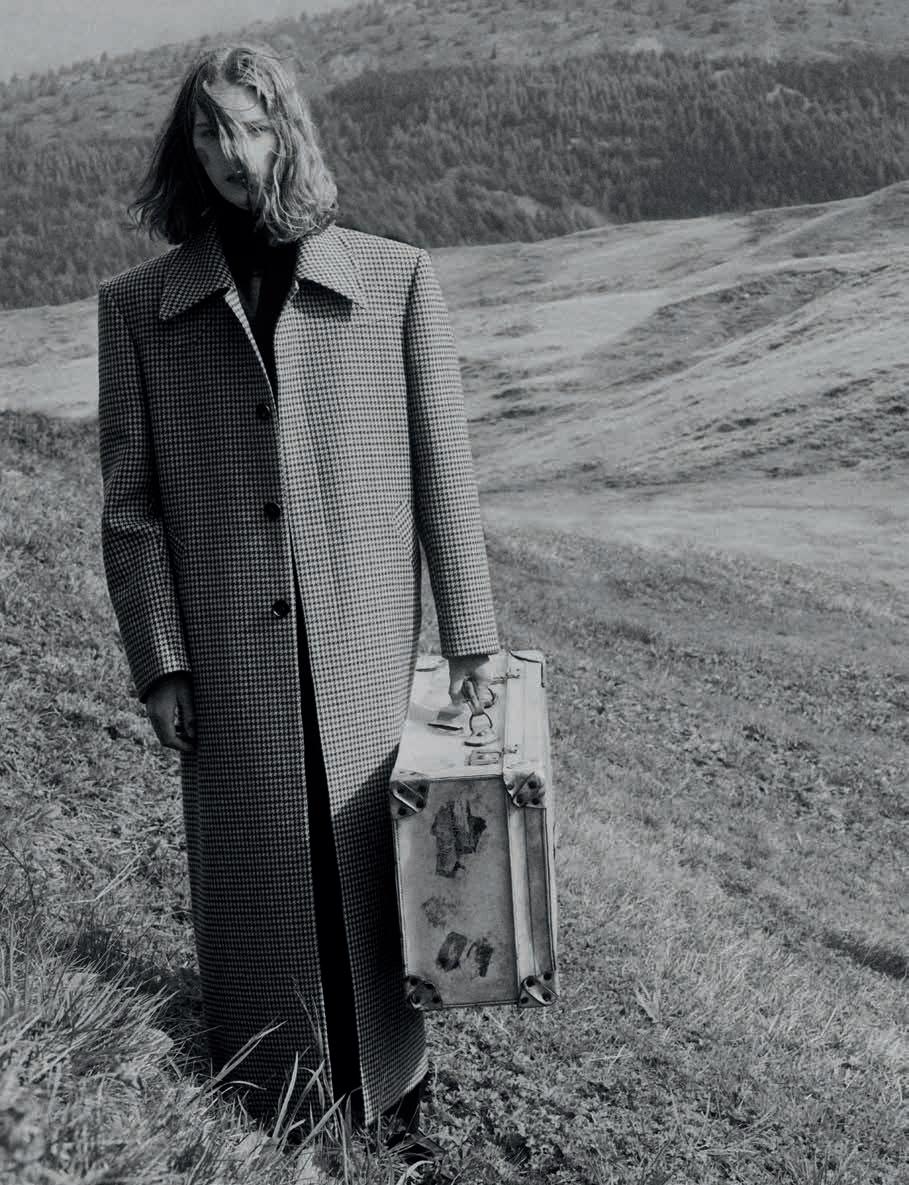

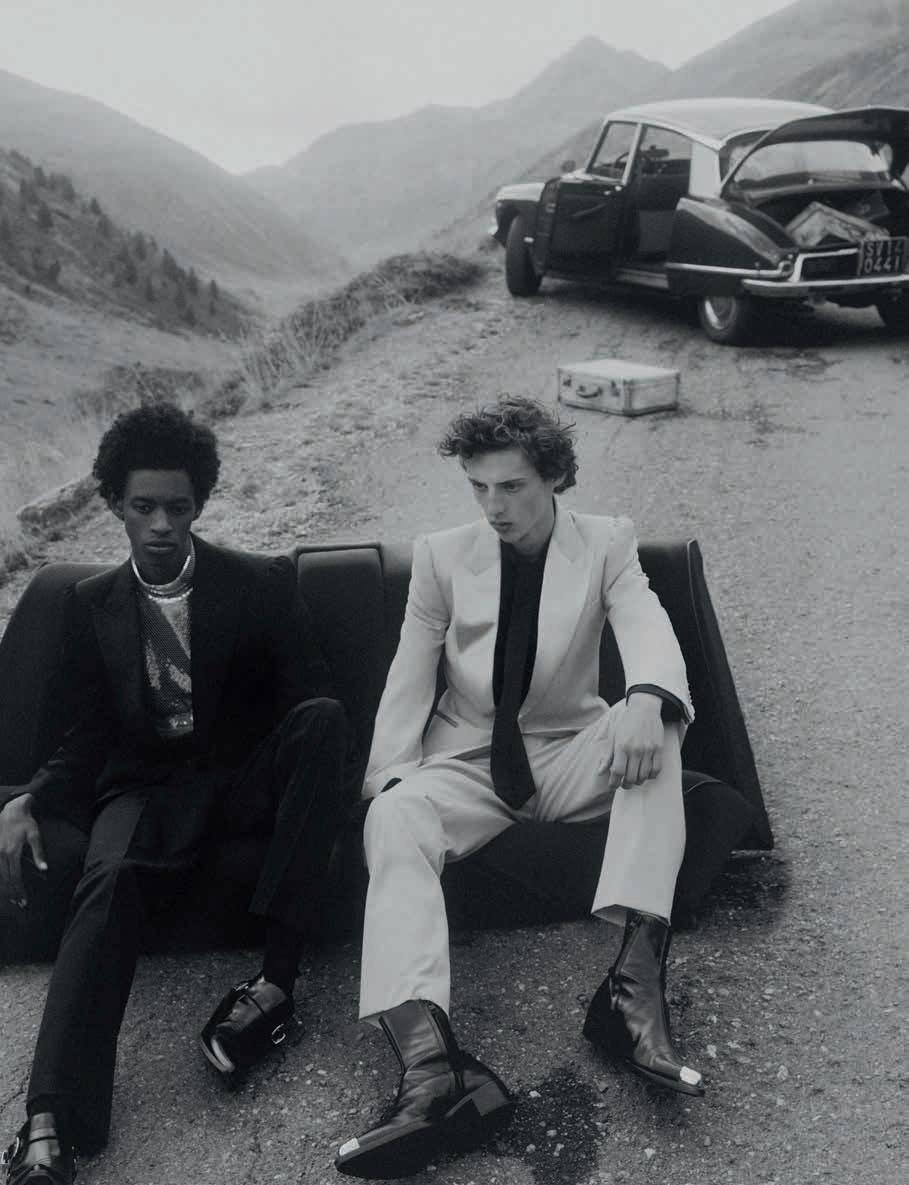

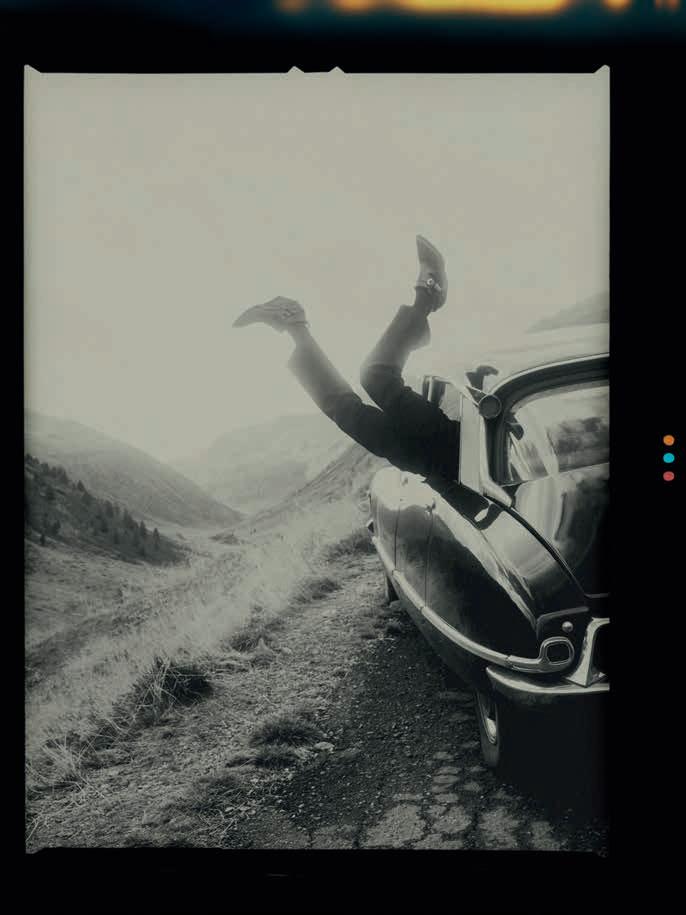

Photography Grace Difford Styling Mitchell Belk

Narcissus

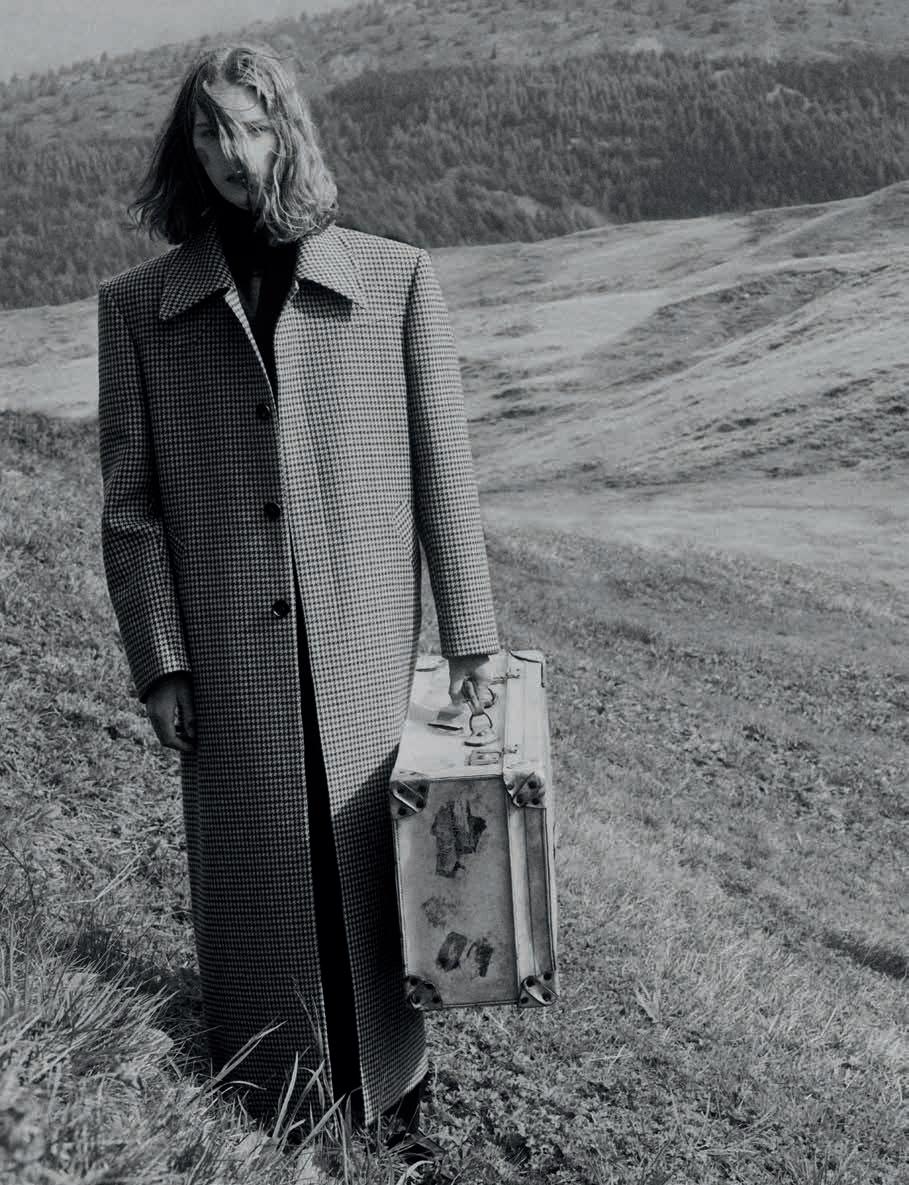

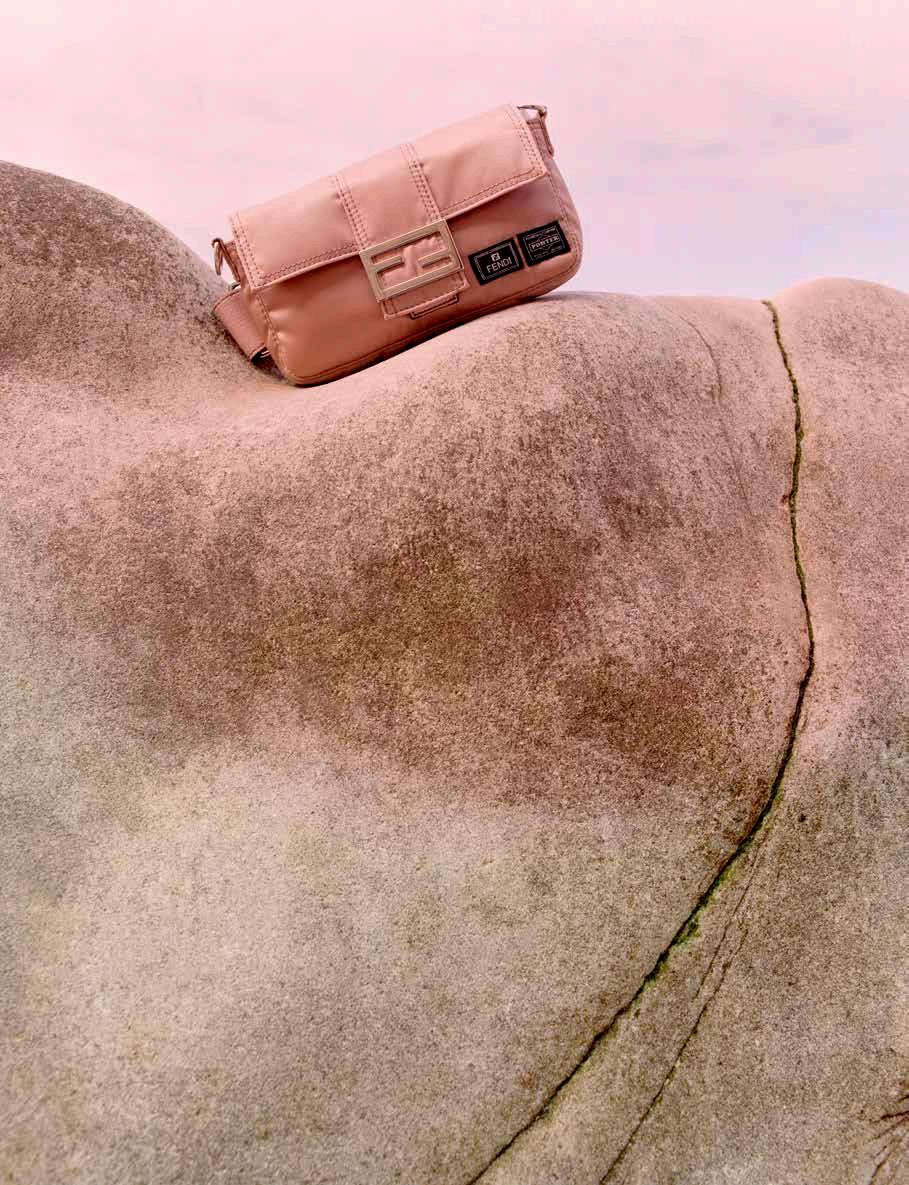

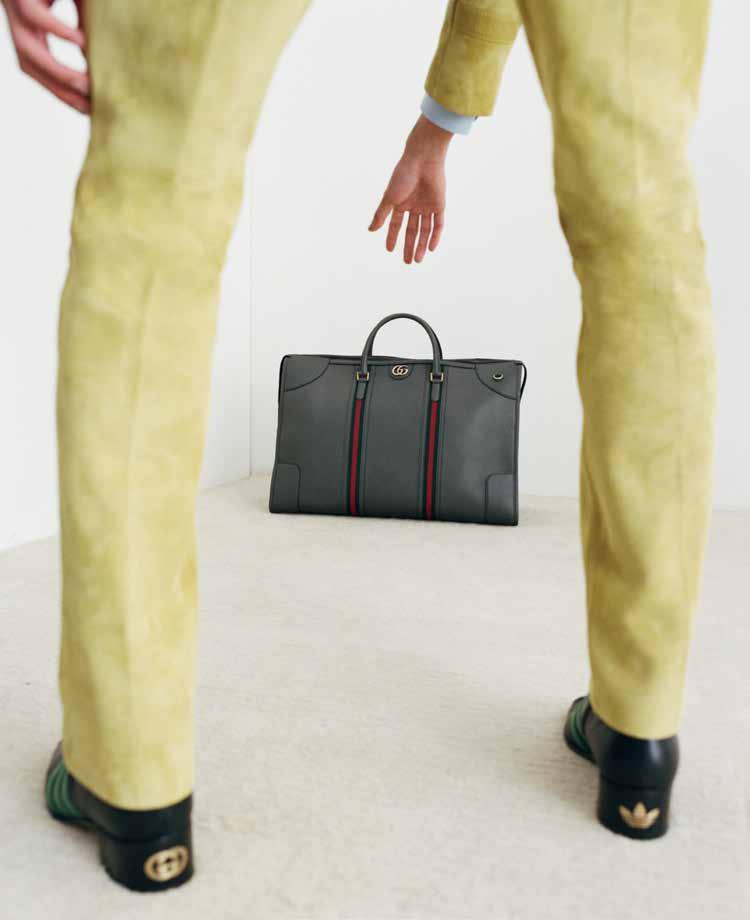

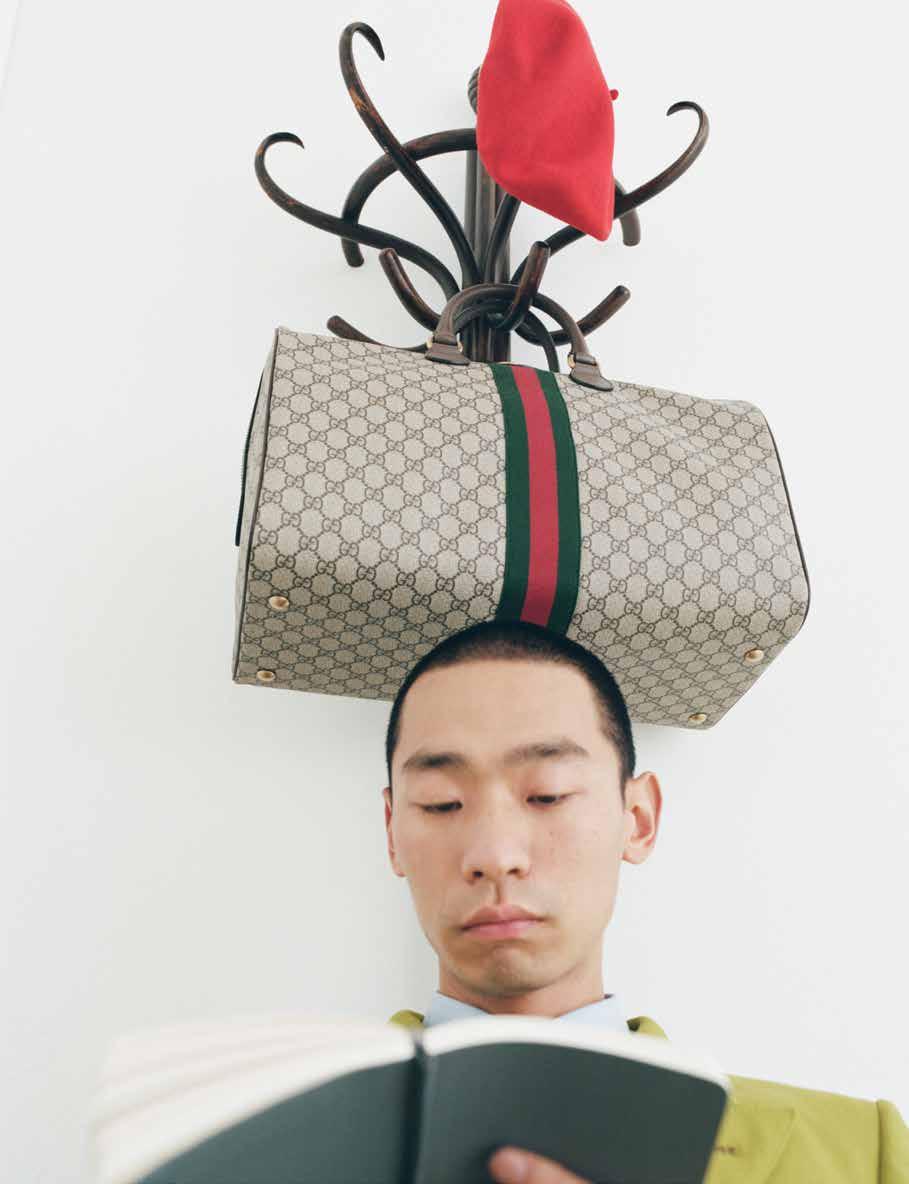

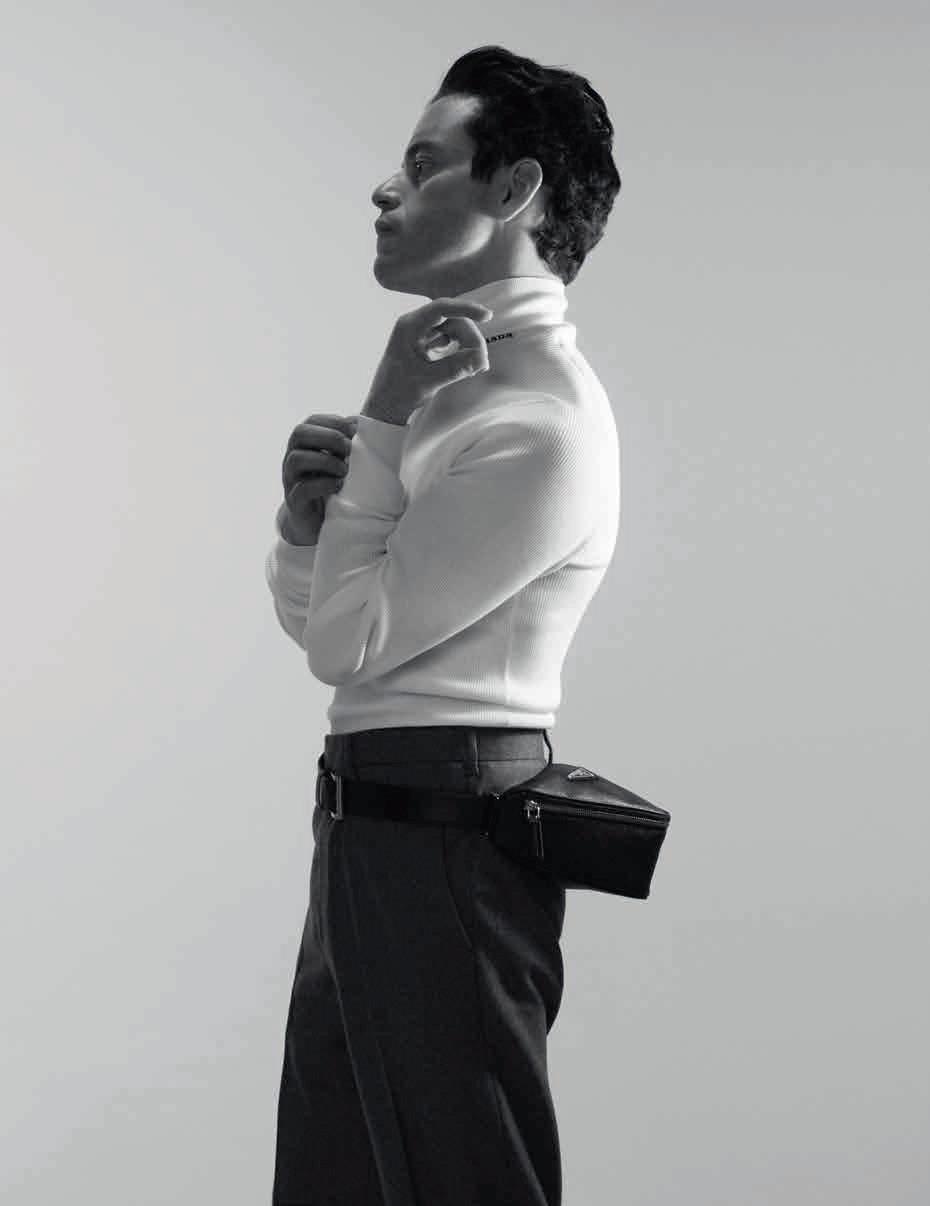

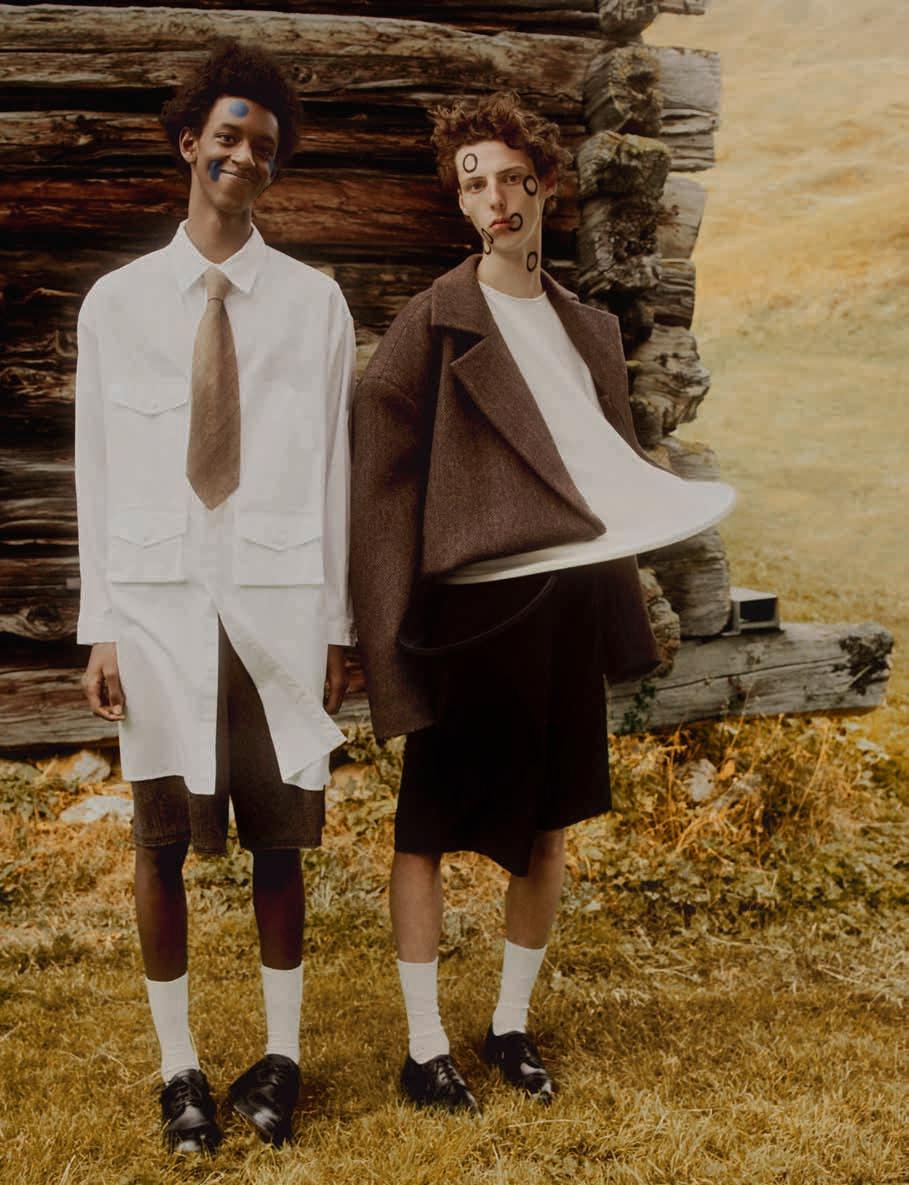

Photography Stefan Armbruster Styling and set design Lune Kuipers

246

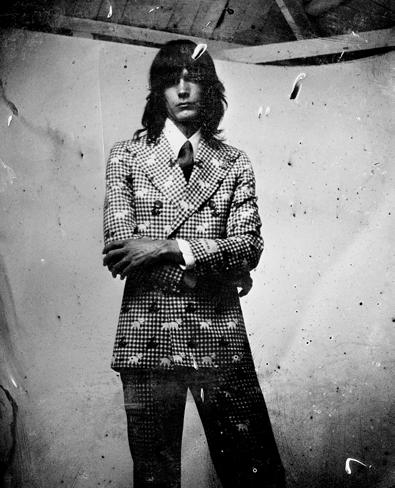

“Sometimes the scenes that aren’t published are actually the places where you find the character. In the past, when I used to see guys on Grindr, I used to make them – to see if they truly wanted to come over –buy me sushi beforehand. Not crazy fancy, just a simple tuna roll. I wanted to know how much did they really care? It was like

sending a knight on a quest before you give them your favour – you must go to the restaurant and conquer one Tekkamaki roll! When I was writing Detransition, Baby and laughing about this specific request, I realised that was the voice of my character Reese, that sort of logic and the gender roles that speaks to. In a certain way, that

was a touchstone moment of building the character. It's not at all in the book, but I had to write it to discover who Reese was. Same with the character Ames; so much of them came out of things that just never made it in.”

Read Torrey Peters’ profile starting on p114.

OUT–TAKE

TORREY PETERS, PHOTOGRAPHED IN VERMONT BY ERIC CHAKEEN, WEARS VALENTINO PINK PP FALL/WINTER 22-23 COLLECTION

RION AMILCAR SCOTT

RION AMILCAR SCOTT

Rion Amilcar Scott is the author of the story collections The World Doesn’t Require You and Insurrections, which was awarded the 2017 PEN/Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction and the 2017 Hillsdale Award from the Fellowship of Southern Writers. He teaches creative writing at the University of Maryland. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, the Kenyon Review, Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2020 and Crab Orchard Review, among other publications.

JEANETTE WINTERSON

Jeanette Winterson CBE is a British writer. After graduating from Oxford University, she published her first novel at 25. Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit is based on her own upbringing but using herself as a fictional character. She scripted the novel into a BAFTA-winning BBC drama. Twenty-seven years later she re-visited that material in her internationally bestselling memoir Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?. She has written 13 novels for adults, two collections of short stories, as well as children’s books, non-fiction and screenplays. 12 Bytes is her latest book.

Grace Difford is a fashion and portrait photographer based in London. Having studied at Central Saint Martins, she went on to work for Purple magazine under Olivier Zahm, and at Interview in New York. After a protracted period away working in the music industry, Grace then returned to London, where she assisted some of London’s most prestigious photographers. This formative time culminated in her position as studio manager and first assistant for Charlotte Wales. Exposed to the eccentricities of a musical upbringing, it became second nature for Grace to document the transient and robust lives in orbit around her. Her work imbues the everyday with performative, cinematic flourish.

STEVEN PINKER

Steven Pinker is an experimental psychologist who conducts research in visual cognition, psycholinguistics, and social relations. He grew up in Montreal and earned his BA from McGill and his PhD from Harvard. Currently Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology at Harvard, he has also taught at Stanford and MIT. He has won prizes for his research, his teaching, and his books, including The Language Instinct , How the Mind Works , The Blank Slate , The Better Angels of Our Nature, and Enlightenment Now. He is an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences, a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist, a Humanist of the Year, a recipient of nine honorary doctorates, and one of Time’s “100 Most Influential People in the World Today.” He was Chair of the Usage Panel of the American Heritage Dictionary, and writes frequently for the New York Times, the Guardian, and other publications.

His twelfth book is called Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters

CONTRIBUTORS

GRACE DIFFORD

Keeping Iceland warm since 1926

66north.com

Follow us @66north

WILL SHARPE

Will Sharpe is a multi-BAFTA nominated and BAFTA Award-winning English Japanese writer, director, and actor. Set to star in the latest season of HBO/Sky’s The White Lotus, Sharpe’s critically acclaimed writing and directing for both the big and small screen includes Landscapers, The Electrical Life of Louis Wain and Flowers. The latter – a black comedy on Channel 4 tackling mental health – earned him a nomination for a Best Scripted Comedy BAFTA, while Sharpe’s role in the BBC thriller Giri/Haji won him a BAFTA for Best Supporting Actor.

MICHAEL CERA

Michael Cera has appeared in the FOX series Arrested Development, and in feature films Superbad, Juno, Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist, Youth in Revolt, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, Crystal Fairy and the Magical Cactus, This is the End, and Molly's Game. Cera made his Broadway debut in Kenneth Lonergan’s This is Our Youth, and also starred in Lonergan’s Lobby Hero, for which he received a Tony Award nomination for Best Featured Actor in a Play. He recently completed the Lonergan trilogy on Broadway with a starring role in The Waverly Gallery opposite Elaine May, Lucas Hedges and Joan Allen. Cera can be seen starring alongside Amy Schumer in the critically acclaimed series Life & Beth on Hulu. Currently, Cera is filming Greta Gerwig’s Barbie opposite Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling.

OLYA OLEINIC

Olya Oleinic is a visual artist whose work is mainly based in photography. Her photographs share a vision unbound by the conventions of an expected aesthetic. Each body of work is rooted in research, each choice considered to suit its character, then tied together with the tailored, always evolving sense of visual direction. Oleinic's images speak through their confident subtlety, the sensitivity of a personal relationship to her subjects, and reflect an embrace of daily observations amidst the climate of complex and ever-shifting social and cultural matters. The themes within Oleinic's work, as well as the means and choices of her practice are based on the ambition of developing a strong community, one with a sustainable progression and a healthy climate within. Born and raised in Republic of Moldova, she currently lives and works in Paris.

ORHAN PAMUK

Orhan Pamuk is the author of 11 novels, the memoir Istanbul, and three works of nonfiction, and is the winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature. The Swedish Academy praised Pamuk, ‘who in the quest for the melancholic soul of his native city has discovered new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures.’ One of Europe’s most prominent novelists, his work has been translated into over 60 languages. His latest novel, Nights of Plague, was recently published by Faber.

CONTRIBUTORS

01

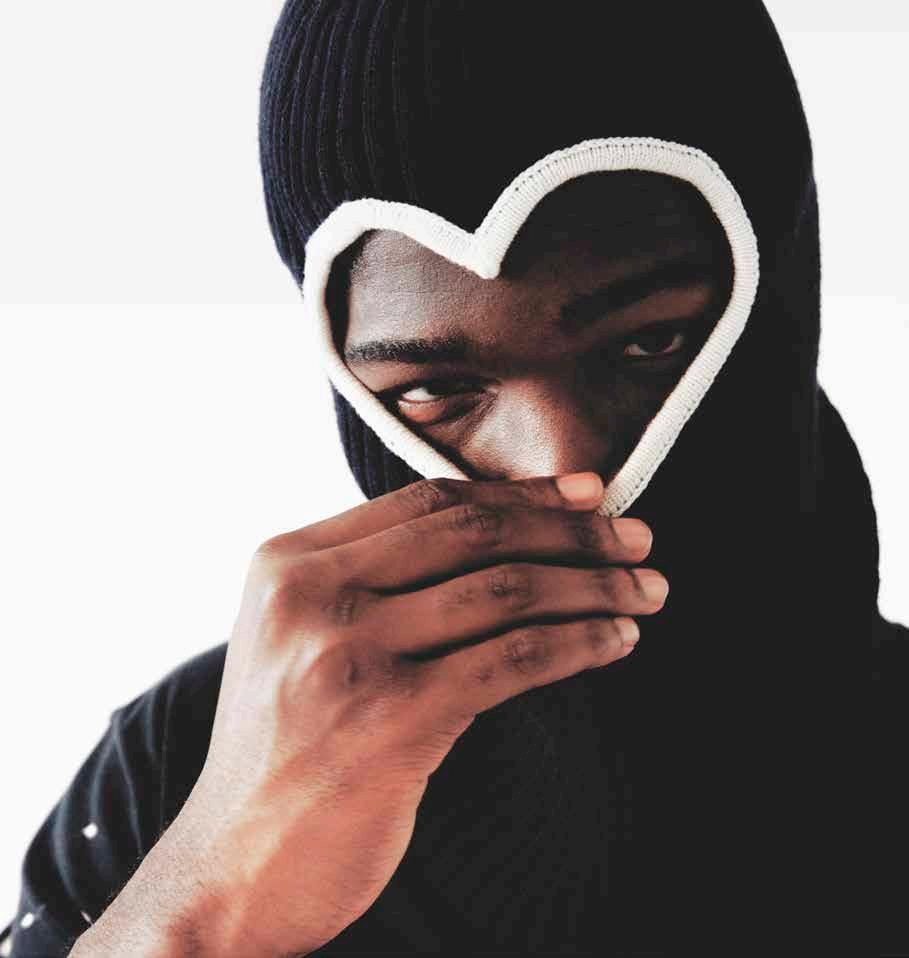

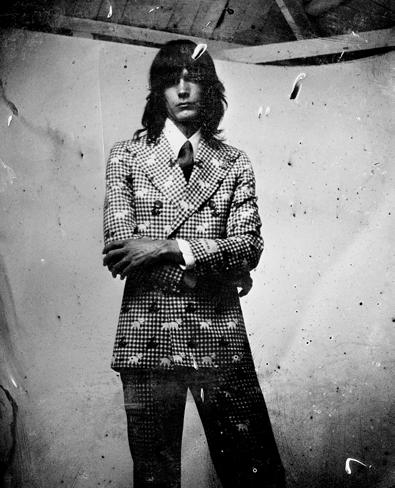

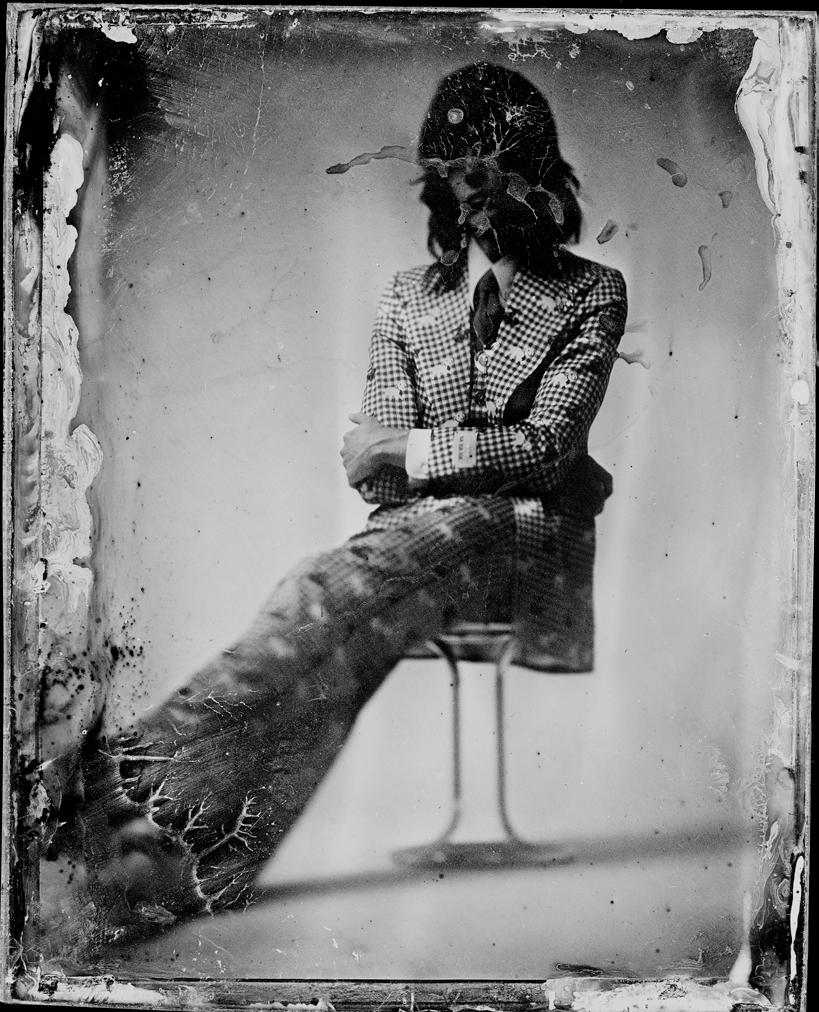

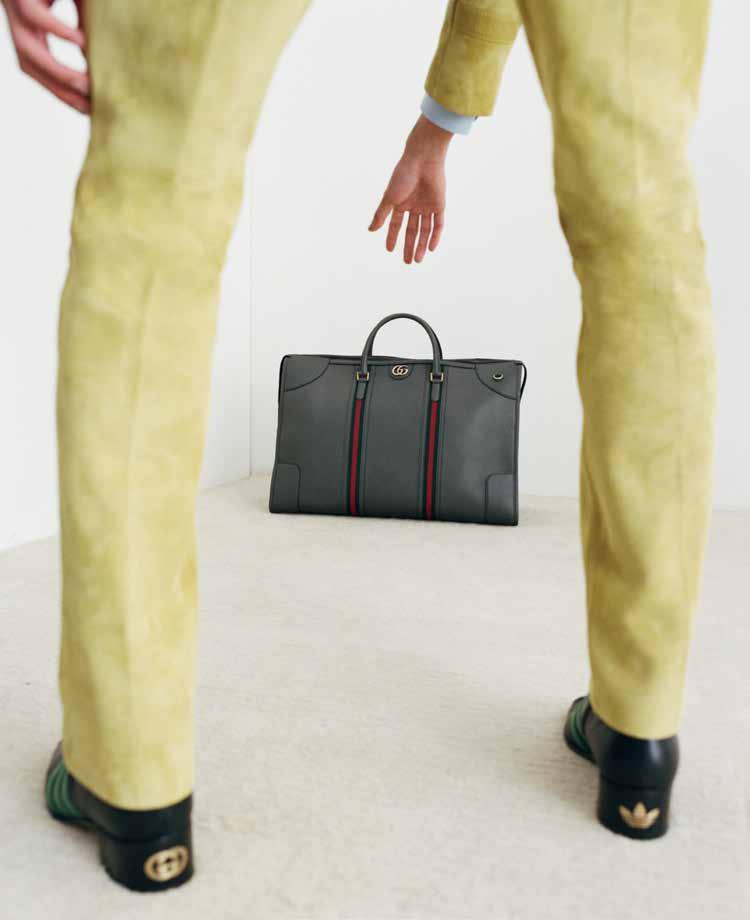

WHEN HARRY MET ALESSANDRO

By Dylan Holden. Harry Styles creates a dream wardrobe with Gucci

Alessandro Michele had just become Gucci’s creative director when Harry Styles asked to meet him. Ready to dismiss the plucky pop star who had just started his solo career, all Michele’s reticence disappeared when Styles rocked up in a “fabulous” fake fur coat. They hit it off immediately, and in the subsequent years their friendship has blossomed through creative exchange, the musician-turned-actor now celebrated as a Gucci guiding star.

If you were to review the pair’s WhatsApp messages, you would see a tableau of shared references to chic 1970s menswear, iconic fits, and all things vintage. You may also notice that their sign off is always the same: “hahaha”. Their first official collaboration together neatly references this neological expression that is both pure joy and a clever combination of their forename initials –

45Photography Gaëtan Bernède

Gucci HA HA HA. Born from Michele’s proposal to create a “dream wardrobe” with Styles, the collection draws on the deluge of snippets and “small oddities” they often send one another. Nevertheless, despite the clear fun they had playing together in the creative sand pit of ’70s pop and bohemian silhouettes, it’s a seriously smart collection.

Mischievously nodding to significant formal devel opments in menswear, velvet suits with peaked lapels sit alongside the unexpected – printed pyjamas, bowl ing shirts, and pleated kilts. Traditional English tailoring has more than a dash of dandyism thrown in. Prince of Wales patterned double-breasted coats and tweed blaz ers are eccentrically accessorised with houndstooth caps, bow ties and neck scarves, whilst whimsically bold prints of cherries, grumpy bears, lambs, and now something of a recurring motif between the two – a big red heart – are found printed or appliquéd on everything from suits to a striking pair of two-tone Chelsea boots. This flamboyant and flared sea of checks, daisy-yellow, plum and chocolate-brown never feels costume-like due to the artisanal processes glimpsed; the delicate construction of a patchwork leather jacket, the hand-knitted sweater vests, or the mother-of-pearl button detailing on shirts.

“Harry has an incredible sense of fashion,” says Michele. “Observing his ability to combine items of cloth ing in a way that is out of the ordinary compared to the required standards of taste and common sense and the homogenisation of appearance, I came to understand that the styling of a look is a generator of differences and of powers, as are his reactions to the designs I have cre ated for him, which he has always made his own; these reactions restore me with a rush of freedom every time.”

Set to be released in October, the 25-look collection was officially presented within Cavalli e Nastri, one of the oldest vintage stores in Milan. There is something rather amusing about the fact Michele had to double check the capsule’s labels on the shop’s storied rails, momentar ily unsure where the retro collection began and ended.

Portfolio46

Styling Karlmond Tang

Model Harry Westcott at Select

Grooming Charlie Cullen

Casting Marqee Miller

Photography assistant Eduardo Guida

47

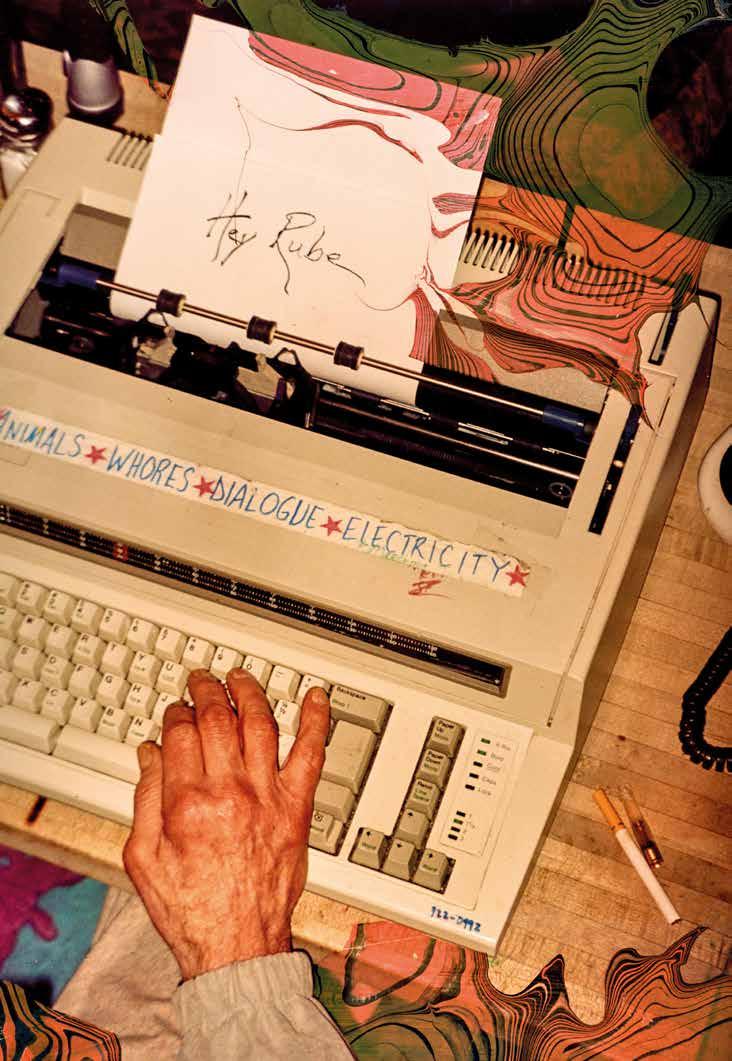

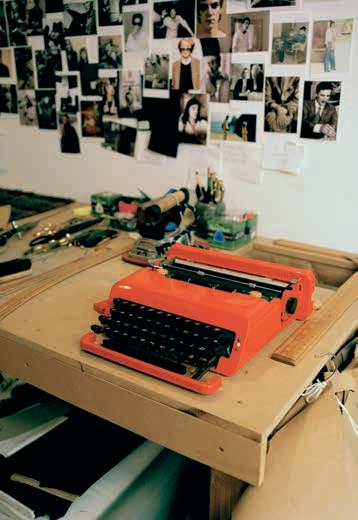

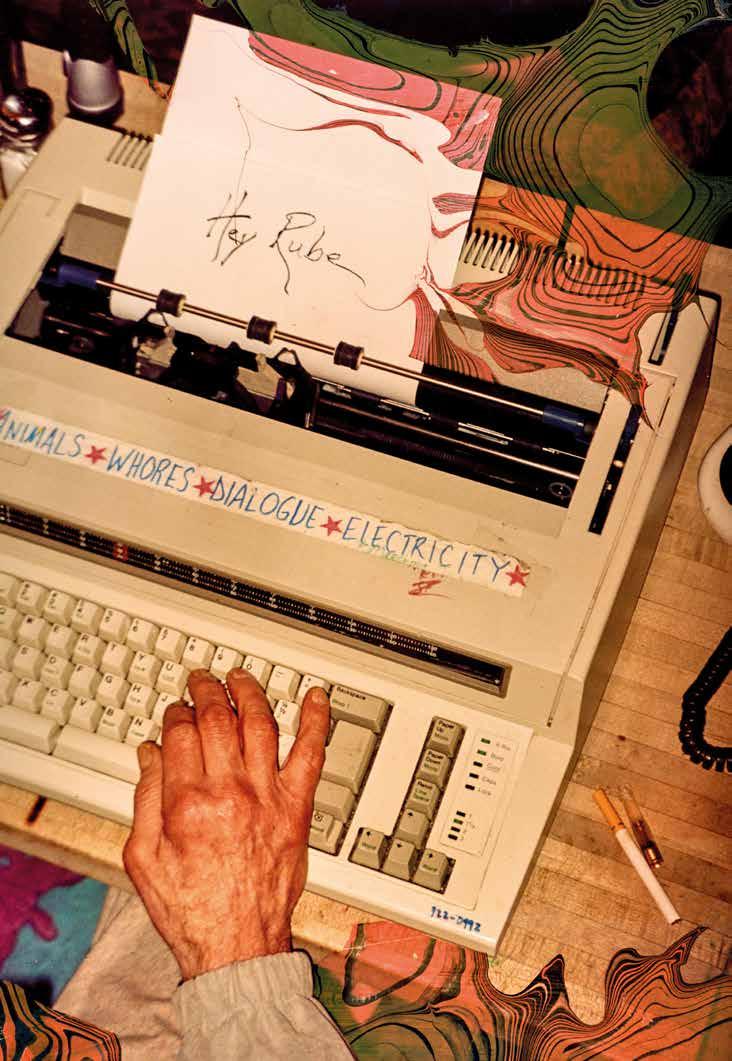

OWL FARM

By Chloe Sells. A window into Hunter S. Thompson’s home

I grew up in Woody Creek, Colorado, where Hunter’s house was. My mother had owned a restaurant for dec ades that everybody went in and out of, so I knew the cast of local characters well. One evening, at the after party of the documentary Breakfast with Hunter, I bumped into his wife. Anita looked me up and down and asked, “Are you a night owl?” Yes, absolutely. “Would you like to be Hunter’s personal assistant?” I said of course.

Hunter’s home – Owl Farm – was his lair of creativ ity, his nest of security. He had lived there for over 40 years. It was an old rambling cabin set back in a beau tiful part of the Aspen valley, receiving 300 days of sun. All that nature unfolding in your backyard calms the spirit. For somebody like Hunter, who was completely frenetic, coming back to those mountains centered him. You could go outside in the snow and the whole world would light up inside of you with one breath of fresh air. He once wrote that, “It was a very important psychic anchor to me, a crucial grounding point where I always knew I had love, friends and good neighbors. It was like my personal lighthouse that I could see from anywhere in the world – no matter where I was, or how weird and crazy I got, everything would be okay if I could just make it home. When I made that hairpin turn up the hill onto Woody Creek Road, I knew I was safe.”

Inside, the walls crawled with scrawls of writing, quotes and notes on every spare inch, while small holes from ricocheting bullets penetrated the wood pane ling. At Owl Farm you were surrounded by language. His wild and outsized lifestyle would’ve been impossi ble any place else; he needed the space to run around shooting guns, host celebrity friends, and essentially to do whatever he wanted. His best friend was the sher iff, so in some ways, he was the law. He also knew my bohemian family was as weird as he was, so he trusted me, completely. I was at home there.

I would clock out from my day job at 11pm and go work for Hunter (he was nocturnal) doing everything and anything that needed doing until sunrise, then I would get some sleep, hike, work on my photography, day job, repeat. Knowing that I was a young artist trying to make it in the world, one day he teased me that Taschen was making a book of his photographs, and wasn’t it funny that I thought I was a photographer? Cue mocking laugh ter. He immediately felt bad – because really, he was a gentleman – and told me that the only thing in his life that hadn’t been photographed was his home. “Have at it,” he said, “it’s yours.”

The reason this project has seen the light of day is a combination of events, but mostly from being completely overwhelmed six years ago when my husband died and I was pregnant. Amidst everything I still wanted to keep my artistic practice going, as I had worked so hard for it to be viable. I dusted off my Owl Farm negatives from all those years ago, thinking that it would be a quick and easy project to make a book, but I found I was reluctant to put them out in the world. They felt private, and I didn’t want to be reduced to ‘the photographer who was Hunter S. Thompson’s PA’. They were also not enough on their own, they didn’t have any life to them. I took a course in Italian marbling and fell down a rabbit hole, later experimenting with the Japanese technique of sum inagashi, which is more psychedelic. Suddenly, I had found a language that allowed a conversation between the two different types of interior and exterior images. After the marbling, the work popped and made sense, the images had an energy to them.

The photograph of the mountains I’ve shared on the next page is very personal to me. Set within the image is an old ghost town called Ashcroft, formerly home to a silver mine, now deserted. As a kid I would visit its old saloon and late-19th-century buildings. I took that

Portfolio48

02

49Artwork Chloe Sells

photograph in the middle of high summer, and if you look closely, the colours in the marbled over-painting pick up all the wildflowers that have spread across the field. It’s a beautiful moment in time at a power ful place in the valley.

I don’t remember the moment when I took the image of Hunter’s desk. I was lucky though, because you have everything there, the cigarette, his iconic holder, and primary tool for writing: his hands. This was not long before he died, and you can see the arthritis creep ing into his fingers. He sat in front of his typewriter every day but was not particularly prolific; there was always an outstanding paper due, a half-finished book, always behind, forever late. It was messy when I was there, and his publishers often pulled their hair out because they couldn’t get him to perform. But here, in this intimate shot (I would have had to stand over him for this angle) you can see his intensity, joy and commitment to writing.

Hunter never got to see my photographs, but I like to think he would have said “hot damn!” which is what he would often declare when revisiting his favourite work, or when someone read it back to him. He has a whole world of lore around him; reams and reams of stories have been published since his death. How ever, I feel this is a real and true slice of his life, and that is ultimately why I pulled it out of the closet. I fig ured Hunter had gifted me this assignment because he was such a narcissist. Ironically, given his suicide, he wanted to live forever. I feel I’ve contributed to that desire.

As told to Tom Bolger

Hot Damn! by Chloe Sells is published by GOST books, out now

Portfolio50

Artwork Chloe Sells

51

LEAVE ROOM FOR PUDDING

By Billie Muraben. Practicing ecology with Cooking Sections

Muhallebici – pudding shops named after an Ottoman speciality of shredded chicken thickened with rice water, sprinkled in sugar and rose water – serve profiteroles, baklava, sütlaç (rice pudding, with a burnt top), and kay mak (a rolled, sour, clotted cream) throughout Istanbul. They are traditionally made with buffalo milk, which has a consistency more akin to cream than cow’s milk, making for full flavour, rich puddings. The use of buf falo milk in Turkey has declined due to the complex ity and cost of keeping water buffalo, as their habitat is compromised by urban development. As part of their research for ‘Climavore: Seasons Made to Drift’ – an exhibition and public programme that considered how to eat as humans change the climate, shown at Istan bul art institution SALT – spatial practitioners Cooking Sections (Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe) looked into the disappearance of the wetlands in the north of Istanbul, which had been home to water buf falo since they migrated with Bulgarian herders during the Ottoman period. “We wondered: What could be an interesting move to protect the wetlands as free roam ing space for buffalo? And for the herders, who have been taking care of them for centuries.”

The wetlands were formed among the ruins of aban doned coal mines, in flooded pits that became wallows for water buffalo to rest while roaming the landscape. Now the land has been reclassified for real estate, and the wetlands drained. “There has been a cultural shift in the perception and understanding of how traditional dishes like sütlaç or kaymak are made, and how they need the free roaming of buffalo for the production of milk, and for the ecosystem to function.” Cooking Sections met with buffalo herders, and dug a new wallow along a stream, turning the extracted clay into pots for sütlaç and yoghurt. They collaborated with muhallebici, serving buffalo milk dishes (in some cases from the 1,000 pots made with ceramicist Başak Gökalsın), introduced buf

falo milk to the curriculum at the Culinary Arts Acad emy, and produced a new edition of mapping project Between Two Seas, charting the network of buffalo wal lows. “We were looking into different, or new possible seasons that are emerging in the Anthropocene,” says Cooking Sections. “Over the last few years, we have been working on what it would mean if instead of the four seasons in Europe, we identified new seasons in action; periods of drought, periods of flash floods, or alterations to the sea shore, which are non-sequential yet repetitive and underpin contemporary food infra structure and eating habits.”

For this year’s Istanbul Biennial, Cooking Sections elaborated on their research in Wallowland, a project that seeks to preserve the wetlands, and highlight the cul tural and ecological role of water buffalo. “It manifested in two ways, as a series of metabolic surveys, for which we commissioned experts to help us understand the digestive or metabolic relationships between buffalo, and other ecologies – the birds interacting with buf falo on the wetlands, the struggles and dependencies within the context of drought, the grasses, and songs about buffalo written in Turkish, Kurdish, and Bulgar ian. These studies will manifest as an installation in Istanbul’s Beyoğlu district, and as a manda festivali (buf falo festival) – the first edition of what will be an annual event – which took place in the outskirts of the city, cel ebrating these interactions.” Visitors enjoyed perfor mances, cooking demonstrations, research presenta tions, and an ‘open house’ led by the herders, “almost like a field work day”.

Cooking Sections are known for their ability to com municate the complex narratives and systems that organ ise the world through familiar settings involving food. Their first collaboration, with Forensic Architecture, Modelling Kivalina, The Coming Storm, took place above the Arctic Circle on the northwest coast of Alaska and

Portfolio52

03

53Cooking Sections –

Daniel Fernández Pascual ( R) and Alon Schwabe (L). Photography Rachel Gordon

sought to support the people of Kivalina, an Iñupiaq village on the frontier of the climate emergency. “Their food practices organised a lot of the yearly cycles. As the climate changes, it postpones the formation of sea ice, and exposes the shore to storms, changes the terrain, and impacts the seasons.” Cooking Sections interviewed village residents, scientists, and political representatives, making a film and a series of models, seeking to pro duce a new negotiation platform supporting residents in their fight for oil and gas companies to contribute to their forced relocation costs, as the area became inhabit able. “Food becomes a lens that allows you to chart these places in transformation” says Cooking Sections. “It is also a practice that touches every living being of this planet. Food cuts across so many constructed strata of society, and between species. It becomes very effective.”

As their practice progresses, Cooking Sections have maintained their interest in the overlaps between art, architecture, ecology and geopolitics. This focus has for malised in their ongoing, site-responsive project CLIMA VORE, which has manifested as an exhibition in Istan bul; an installation and performance – of a dining table at low tide, and an oyster table at high tide – exploring the environmental impact of aquaculture on the inter tidal zone at Bayfield on the Isle of Skye; a series of dishes served at museum restaurants across the UK, made with ingredients that improve soil and water quality, and cul tivate marine habitats; a series of interventions and per formances delving into a holistic health model for the human body, the bodies of mussels, and the body of the city of Los Angeles; and a “salmon trilogy”, explor ing the gap between the appearance and the reality of salmon, and their inability to escape intensive farming.

Multi-year investigations have proved integral to Cooking Sections’ intention of practicing ecology, rather than discussing it for one project. “We have been on a big journey in the cultural sector, and there is a certain expectation to respond to the climate crisis. Raising awareness is important, but for us the growing ques tion has been, ‘what does it mean to practice ecology?’

Not only for the duration of an exhibition, a biennial, or other inherited formats, which are in many ways counter intuitive to and ill-equipped for addressing these ques tions”, they note. “We are focused on how we can use the infrastructure available for us to develop ecological

projects in a rooted way. That requires us to continue asking the same question, in order to go beyond the level of highlighting harmful or violent practices, and transform them, or develop alternatives to them. It is a process that takes a lot of time.”

While they tackle complex, intersecting issues, across a breadth of contexts and practices, Cooking Sections settle their work in familiar settings – a festival, a dining table, a shop – with a light touch that makes multi-sca lar investigations accessible and enjoyable to interact with. “The way we work is we start looking into ques tions that we find relevant or, at least for us, urgent to address, and from there we start having conversations with people. As questions emerge, we think about how to communicate those messages to other people, or reformat them into a platform.” For Wallowland, along side the studies and festival, Cooking Sections worked with muhallebici, serving buffalo milk sütlaç and kaymak: “We thought the format of the pudding shop was inter esting, because it interacts with the street, and is in people’s imagination.” During their research, Cooking Sections found that only a few of Istanbul’s muhallebici still source buffalo milk from small-scale producers in the local area, and they wanted to convey the impor tance of local pudding shops supporting the ecology of the wetlands.

There is a long tradition of supportive ecology in Istan bul, with Ottoman bird pavilions – grand mosques and palaces in miniature – built high on the walls across the city; cat houses – made from wood or cardboard boxes – in parks or settled along alleyways; and bostan (com munal urban allotments) for growing and sharing food, and maintaining soil for microbes, insects, and birds. Building and maintaining habitats for other species is thought to bring luck; the practice is also grounded in a belief in the importance of treating animals well, as we can’t ask for their forgiveness. The muhallebici sup port the herders, the water buffalo, the wetlands, the birds who gather there, the people savouring rice pud ding and clotted cream in the afternoon heat, and the stray cats curling themselves around chair legs, purr ing until a prize spoonful is dolloped onto the floor.

Caring for other species, and practicing ecology, is nothing new: “It has been common sense for centu ries. It is just within cities that it has been forgotten.”

Portfolio54

55

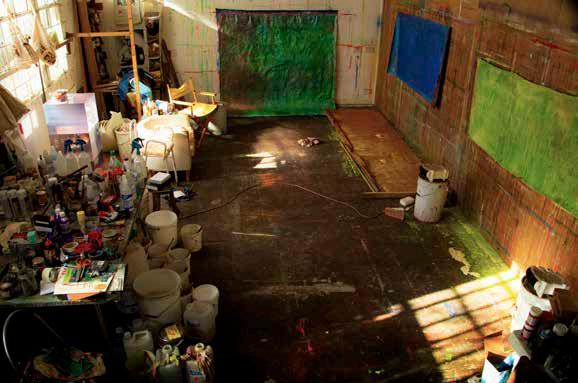

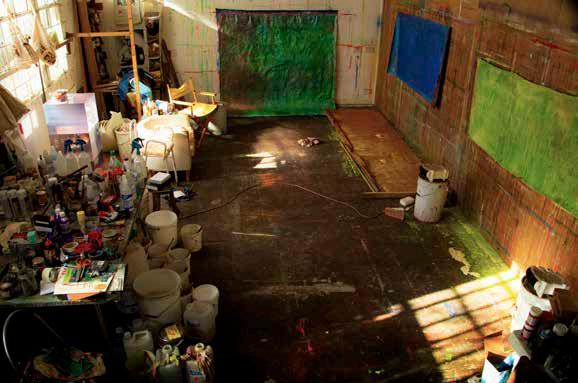

EVERYTHING IS WRONG, EVERYTHING IS RIGHT

By Elizabeth Fullerton. Exploring the possibilities of colour and geometry with legendary artist Frank Bowling

It’s not often one meets a modern master; Frank Bowl ing, at 88, undoubtedly is one. In the course of his multifaceted six-decade career straddling Britain and America, the British, Guyana-born painter has moved between figuration, Pop and Abstract Expressionism to create a painting style that is uniquely his own. Watching him at work in his South London studio, chemistry, cooking and magic come into play. Years of experimentation have given him the assurance to use unorthodox ingredients such as Fairy Liquid – it breaks up the surface tension – or Vim, which soaks up the water and liquid paint that typically drench his canvases, leaving a cratered, encrusted effect. A favour ite is ammonia for the way it eats into the canvas and turns gold powder paint indigo. “I can’t pre-read or predict what’s going to happen next. It’s always sur prising,” Bowling says. Only in the last decade has Bowling’s boundary-stretching inventiveness been fully recognised. A major show in 2017 at Haus der Kunst in Munich, curated by the late Okwui Enwezor, marked a turning point and triggered a flurry of acco lades, culminating in a long overdue retrospective at Tate Britain in 2019 and a knighthood from the Queen. Now the exhibitions are coming thick and fast: the second half of this year alone sees two that home in on under-explored areas of his career. ‘Frank Bowling and Sculpture’ at The Stephen Lawrence Gallery in London is the first to consider the connections between his sculptures and his sculptural paintings, and ‘Frank Bowling’s Americas’, opening this month at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), is the first major survey of the artist’s work by an American institution in more than 40 years and focuses on the crucial period between 1966 and 1975 when the artist lived in New York. Bowl ing left England after feeling pigeonholed in a race box he never wanted to be defined by, despite gradu

Portfolio56 04

57

Frank Bowling. Photography Sacha

Bowling

Portfolio58

ating from the Royal College of Art with flying colours, being awarded the silver medal to David Hockney’s gold. Guyana has always been a touchstone in his paintings, but Bowling resists lazy identarian readings. What trou bles him even now, he says, is that “because I wasn’t born in England, people make a case for me expressing this painting with a Caribbean eye. Well, I’m still wait ing to see this Caribbean eye.” In America he found his voice, taking inspiration from the “daring of the Abstract Expressionists”. New York was buzzing with artists argu ing about art in bars and on the streets. “You could feel it,” says Bowling. “You somehow bounced the energy from that experience, if you were lucky, straight down on the canvas, say going for a walk down Broadway.” In New York, Bowling became friends with the influential critic Clement Greenberg, who encouraged his focus on formal concerns. Even now he sometimes hears the Abstract Expressionist champion in the night. What does he say? “You nearly had it if you hadn’t fucked it up. You put that blue in the corner over there,” Bowling jokes. Soon after Bowling’s arrival in New York, he had a revelation. While pouring paint on the floor, he fol lowed the light coming through the window and “the paint flowed into a kind of map of South America.” He called his friend, the artist Larry Rivers, who suggested he should use an epidiascope to trace the map outlines more accurately. The discovery propelled Bowling on the path towards abstraction, fusing stencilled maps with spectacular colour field washes and dapples of light and shadow in his acclaimed Map Paintings. Bowling rev elled in the limitless possibilities of abstraction, its refusal to be pinned down by reductive interpretations.

Against the backdrop of the civil rights movement, Black Power leaders were calling for African American artists to make work that represented the Black experience. Bowling played an important role in the debate, con tributing magazine articles defending Black artists’ right to engage with any form of artistic expression, and curated a show of abstractionists including Jack Whit ten and Melvin Edwards at the State University of New York, Stony Brook. In the early 1970s Bowling moved into a new phase, using a tilting apparatus to create what he called “controlled accidents” that discharged paint onto the canvas in multiple directions and at dif ferent speeds in his Poured Paintings series. For the Lon don show ‘Frank Bowling and Sculpture’, the curator Sam Cornish brought together a small group of Bowl ing’s unpainted steel sculptures made in the late 1980s and early 1990s alongside canvases from the 1970s to the present to demonstrate the sculptural thinking behind the artist’s painting. “There definitely is a dia logue there,” Bowling tells me. “It’s obvious that sculp ture is principally concerned with form, structure and geometry. But so is painting!” He points to Dutch paint ers he’s looked at, from the 17th-century master Pieter de Hooch to Mondrian: “Those artists used structures in their work that helped me to get to a position where I understood much more clearly what I was trying to do.” While Bowling’s magnificent sculptural reliefs from the 1980s containing everyday detritus from children’s toys to shells are renowned, few people even know of his forays into sculpture. His first was in New York in the early 1970s, a rickety stack of wooden crates. “Don ald Judd lived just around the corner from my loft on

59

Ziff, 1974 © Frank Bowling. All Rights Reserved, DACS/ Artimage 2022 Frank Bowling’s studio. Photography Sacha Bowling

Broadway,” he explains. “His famous minimalist boxes displayed a simplicity and regularity of form that I found engaging, but I wanted to take the idea somewhere else.” (One of his sculptures – resembling a frame for a table stand surrounded by a cube – has the tongue-in-cheek title ‘What Else Can You Put in a Judd Box’.) Back in the UK from 1975, Bowling struggled to get shows despite success in America, where he had a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Yet these long years in the wilderness gave him valuable opportunity for cre ative risk-taking. At that time he was employing pack ing materials and acrylic foam combined with gel, shells and thick paint to build up the surfaces in monumen tal, seething landscapes such as his Great Thames paint ings, which evoke the majesty of JMW Turner and radi ance of Monet. “I’m moved to chuck in anything that’s to hand in the studio,” he says. “I never throw anything away: it adds to the material drama of the painting.” Plastic bags, a visitor’s dress, even his wife’s car keys have all found their way into his canvases at different times. In 1988, he was offered a show at Castlefield Gal lery in Manchester and asked what sculptor he would like to exhibit with. Bowling suggested making some sculptures himself. He scavenged scrap metal from an engineering firm next to his studio and got help with welding. “Doing sculpture and painting at the same time seemed like an interesting way to work out some geomet ric ideas in two and three dimensions. In both the paint ings and the sculptures, it’s about geometry, the way that squares and circles and triangles interact to create stability in form,” he says. Many of Bowling’s sculptures from that period have disappeared or returned to scrap. One, ‘The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat’ after

the neurologist Oliver Sacks’ famous book, sat in Bowl ing’s living room for years, accumulating miscellanea such as a pith helmet and a pair of green woolly socks. He talks of the sculptures as “a bit of fun”, a way of exploring three-dimensional form. “You should have fun with your work,” he insists. “All this business about angst as the only area out of which art can come doesn’t sit well with me.” These are words Bowling lives by. In his studio lined with abstract canvases exploding with colour and myriad pots of paint, brushes and assorted tools, I witnessed the artist bring a painting to life, all the while enjoying himself immensely. Wearing his cus tomary attire of fedora, jacket and cane, Bowling directed family members from his wheelchair with the precision of an orchestra conductor – his health being too poor for the physical labour of his brand of action painting. “Put gel on the edges. No, no, no, you’ve gone putting it on the flat,” he admonishes his son Ben, as he points his green laser pen to a spot on the surface of a vast hal lucinatory canvas thinly stained with rivulets of blue over a layer of red streaks. “Pull the spatula across, you’ve got that right. It’s the imprint of what was left behind that I want,” he says, spraying jets of water from a bot tle. Another canvas was pinned below to catch drips and runs that would mark the start of the subsequent paint ing. Reactions between the materials happen fast and Bowling has to be ready to respond to the unforeseen. Do things ever go wrong? “Everything is wrong, everything is right,” he says. “It depends entirely on the kind of confidence you bring to the work.”

‘Frank Bowling’s Americas’ at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston runs October 22, 2022–April 9, 2023

Portfolio60

Texas Louise, 1971 © Frank Bowling. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022 Three Palms and Dawn, 2020 © Frank Bowling. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022

61

Portfolio62 05

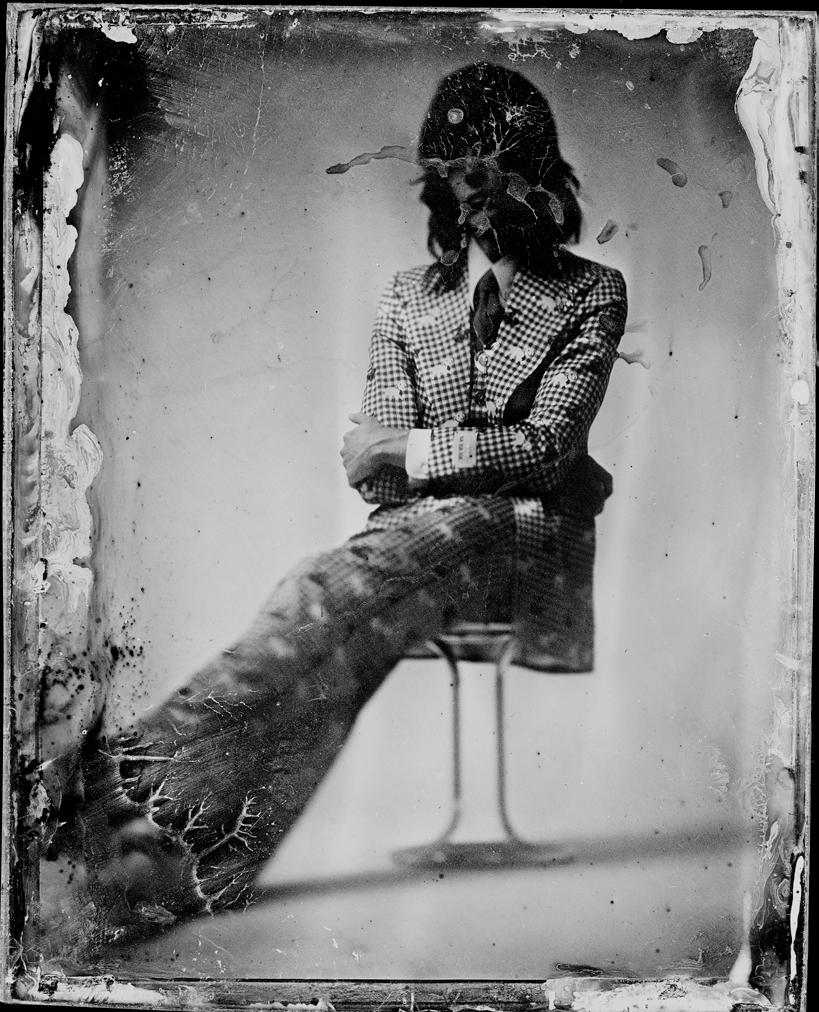

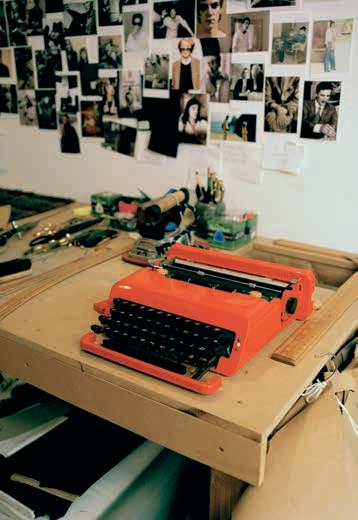

EXILE ON ST. JAMES’S PLACE

By Aleks Cvetkovic. An intimate visit to Tom Arena’s tailoring atelier

By Aleks Cvetkovic. An intimate visit to Tom Arena’s tailoring atelier

What kind of image do the words ‘bespoke tailor’ bring to mind? In London at least, traditional tailoring con jures up a little old man in a fusty suit, shuffling about a mahogany-lined workshop with a tape measure around his shoulders and a prickly ‘suits you, Sir’ attitude.

To 45-year-old self-employed tailor, Tom Arena, who’s been cutting and making suits by hand since he was 18, tailoring means something quite different. Pay a visit to his atelier in a quiet corner of London’s St James’s, and you’ll be greeted with rails of sweeping, floor-length suede coats, sharp looking suits in emerald green and burgundy, and a wall above his cutting table plastered with vintage photographs of everyone from Charlotte Rampling to Serge Gainsbourg. It’s an antithetical expe rience for most of Arena’s customers, who are used to having suits made at Savile Row’s oldest and most tra ditional tailors – and that’s the point.

“I want to give clients a relaxed, enjoyable experience,” he says, as we sit together in the front room of his stu dio. “The atmosphere in tailors’ shops can sometimes be quite stuffy. That’s not what I’m about.”

Not that Arena hasn’t done his time working in the hallowed halls of ‘the Row’. He got into tailoring by chance, when he responded to a newspaper advert for a position at Huntsman, one of Savile Row’s most famous (and expensive) bespoke tailors, just as he was gearing up to leave school. “I was just looking at the Evening Standard, clocked an advert for an apprentice cutter and I’d always loved clothes. I thought ‘this could be inter esting’ and I went for it.”

Arena got the job, and as a working-class boy from southeast London who was into “football and indie music,” it was a shock to the system. “It was completely alien to

me, that kind of atmosphere,” Arena says. “Back then, it wasn’t like a tailor’s shop is now. You weren’t allowed to talk – it was totally silent. All you could hear was the clock ticking. You could only address the customers as ‘Sir’, and only when they spoke to you.”

At Huntsman, Arena learned how to measure custom ers, draft their unique paper patterns and cut suits from their chosen fabrics under Brian Hall, one of the legends of the trade. In the 1970s, he and another renowned tai lor, Colin Hammick, were at the very peak of their pro fession, and between them they’d forged an interna tional reputation for quality.

While Huntsman was far from Arena’s dream place to work, starting on Savile Row accelerated his learn ing and taught him to cut a suit using ‘The Thornton System’, the pattern-making methodology that he still uses today. It also gave him his first taste of dealing with VIP clients; Gregory Peck and Gianni Agnelli were both Huntsman customers at the time. “I look back and laugh at some of it. But a lot of it you do remember – the eti quette and lessons like that. It was a great grounding,” Arena says, with a nostalgic grin.

In need of a change, after five years Arena was head hunted to be the new cutter for Paul Smith’s bespoke tai loring service, which was based out of Smith’s legend ary Westbourne House store in Notting Hill. It’s those 18 years at Paul Smith, he says, that turned him into the tailor he is today. “It was far more creative there, and I had much more freedom. Paul [Smith] didn’t get involved too much and just left us to it. They were fun times.”

Cutting at Paul Smith introduced Arena to a differ ent kind of clientele, whom he found more relatable – “younger guys and creatives in their 20s, 30s and 40s”

63

Photography Sabine Hess

– and it also helped him to build out his celebrity client list. He cut suits for Paul Weller, Chris Hemsworth and Liam Neeson, and remembers Gary Oldman and Dan iel Day-Lewis with particular fondness.

“I made the evening suit for Day-Lewis when he won both the BAFTA and the Academy Award for There Will Be Blood. I also made the evening suit for Gary Oldman’s BAFTA and Academy Award nominations for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Then, I was lucky enough to make the suit for his BAFTA win for Darkest Hour. All those projects were extremely special to me. Both are from the same part of London as me and people I admired greatly.” DayLewis even spent a week working alongside Arena in his cutting room, before stepping into the role of cou turier Reynolds Woodcock in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread

This expertise in celebrity dressing has stood Arena in good stead to do his own thing. He decided to establish himself as Atelier Arena in September 2021, and found his St James’s studio. “I felt like I was the right age, and I wanted the freedom to create the kind of clothes that mirrored me and my own personality,” he explains.

So, what can you expect if you pay him a visit? Quite apart from a warm welcome and some beautiful mid-cen tury furniture, music is a huge passion for Arena, and the stereo is always on. “The ’60s and ’70s are always a source of inspiration. The music and the attitude of the Stones, The Seeds, Bowie and Scott Walker are very important to me too, as well as bands like The Smiths, Joy Division and Wire, which were a big part of my life growing up.”

This perspective feeds into Arena’s creations, which range from handsome grey flannel suits to rock-star-wor thy black-and-gold check jackets cut in vintage cloth.

His preferred approach to cutting, as well as his pas sion for hunting out unusual fabrics, sets him apart. “I learned to cut The Thornton System as an apprentice. It was first published in 1885, and it derives from the old English hacking coat,” Arena says. “It’s all about cut ting a jacket with long, clean lines, high armholes and an accentuated waist.”

These principles make for simple, svelte jackets and trousers, but Arena’s deft use of colour and cloth ensures that his clothes stand out. “I like clients to think ‘wow, where did you get that [fabric] from?’” he explains. “It’s about choosing something that’s not garish and not ostentatious, but just a little bit different.” Beyond suit ing, Arena also makes casual suede overcoats, bombers and blousons, and his studio is filled with chic pieces in tobacco and aubergine.

“I always wanted to introduce something else,” Arena says, thumbing an off-cut of suede. “I love suiting and blazers, but there’s only so much you can do with them, whereas you can have a lot of fun with a suede trench or leather bomber.” Clearly, his clientele agrees. He’s only been in business for a year, but already he’s dressed Jack Lowden, Stephen Graham and Gary Oldman. He’s achieved a lot in a short space of time, which begs the question, where does he plan to take Atelier Arena?

“I want to be known for beautifully made clothes,” he says, as our conversation draws to a close. “It’s all about doing interesting things for me – collaborating with peo ple that I admire, whether that’s artists, actors or musi cians. I want my clients to feel elegant, and sometimes to help broaden their horizons a bit. Tailoring should be about creativity. As Georgia O’Keeffe said: ‘I found I could say things with colour and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way – things that I had no words for.’”

Portfolio64

65Tom Arena working in his St James’s Pl studio

AN UP-HILL CYCLE

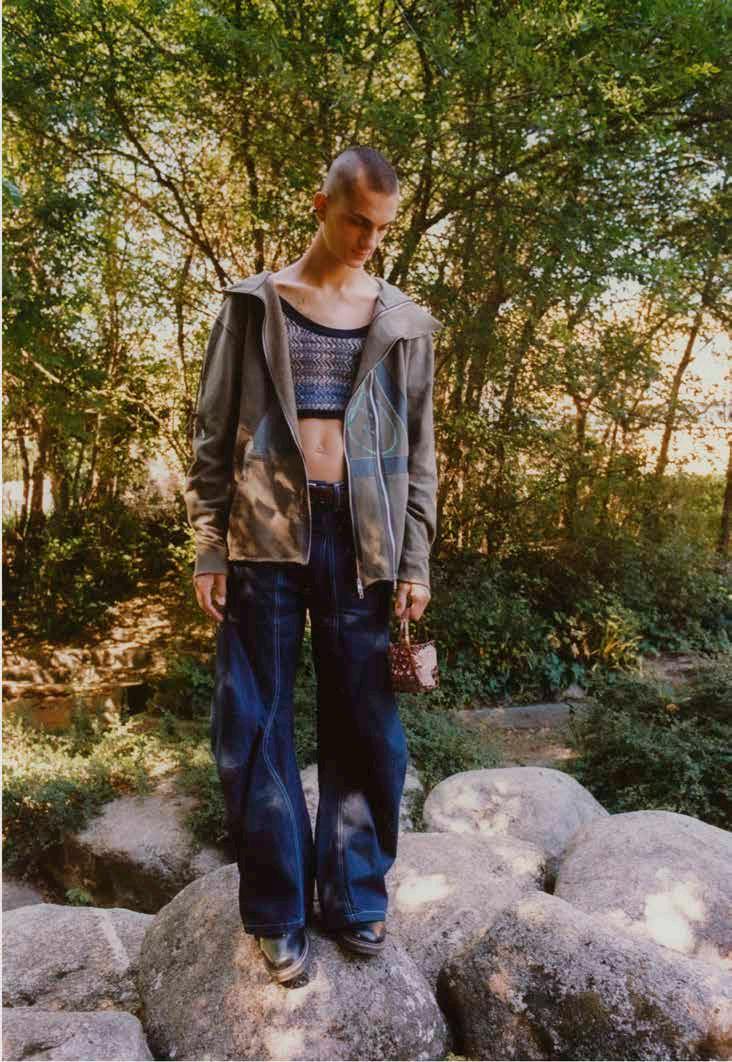

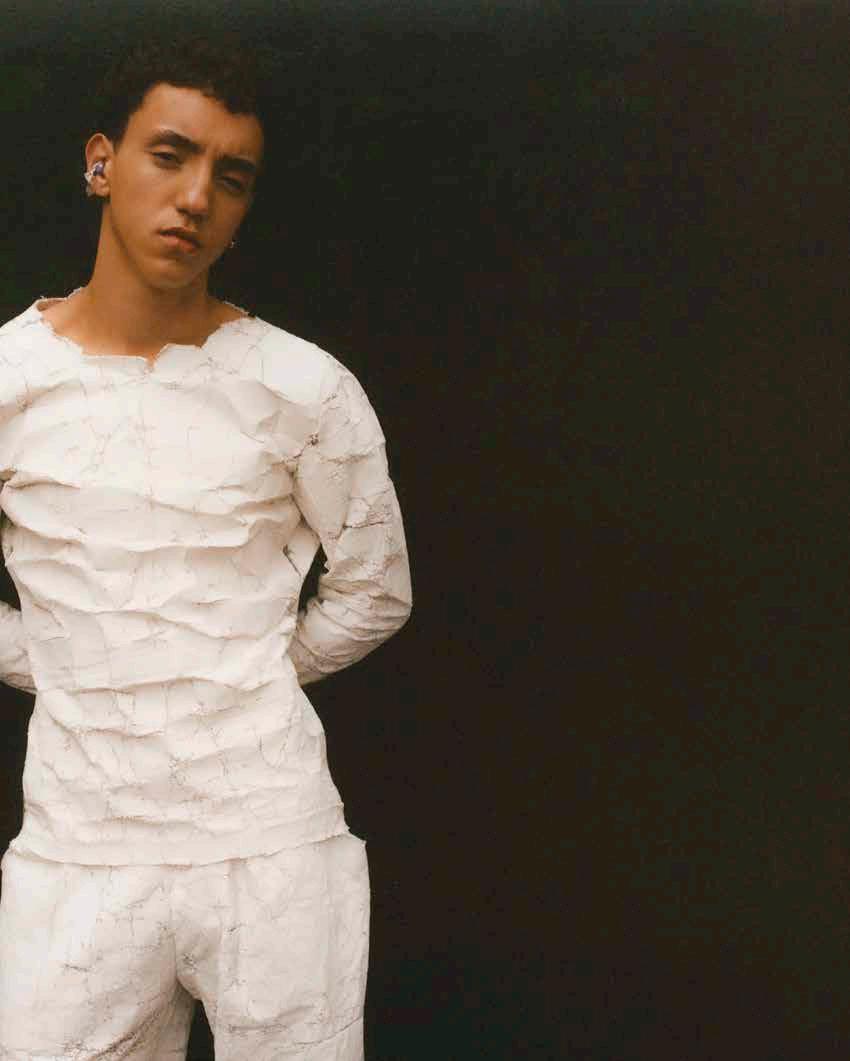

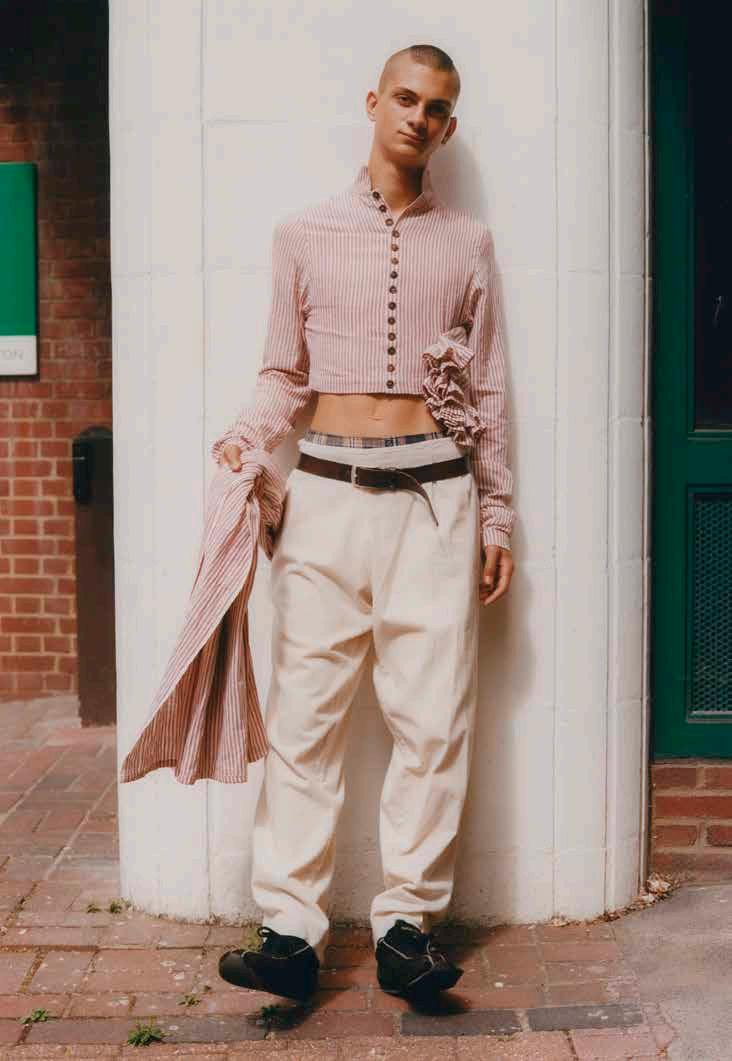

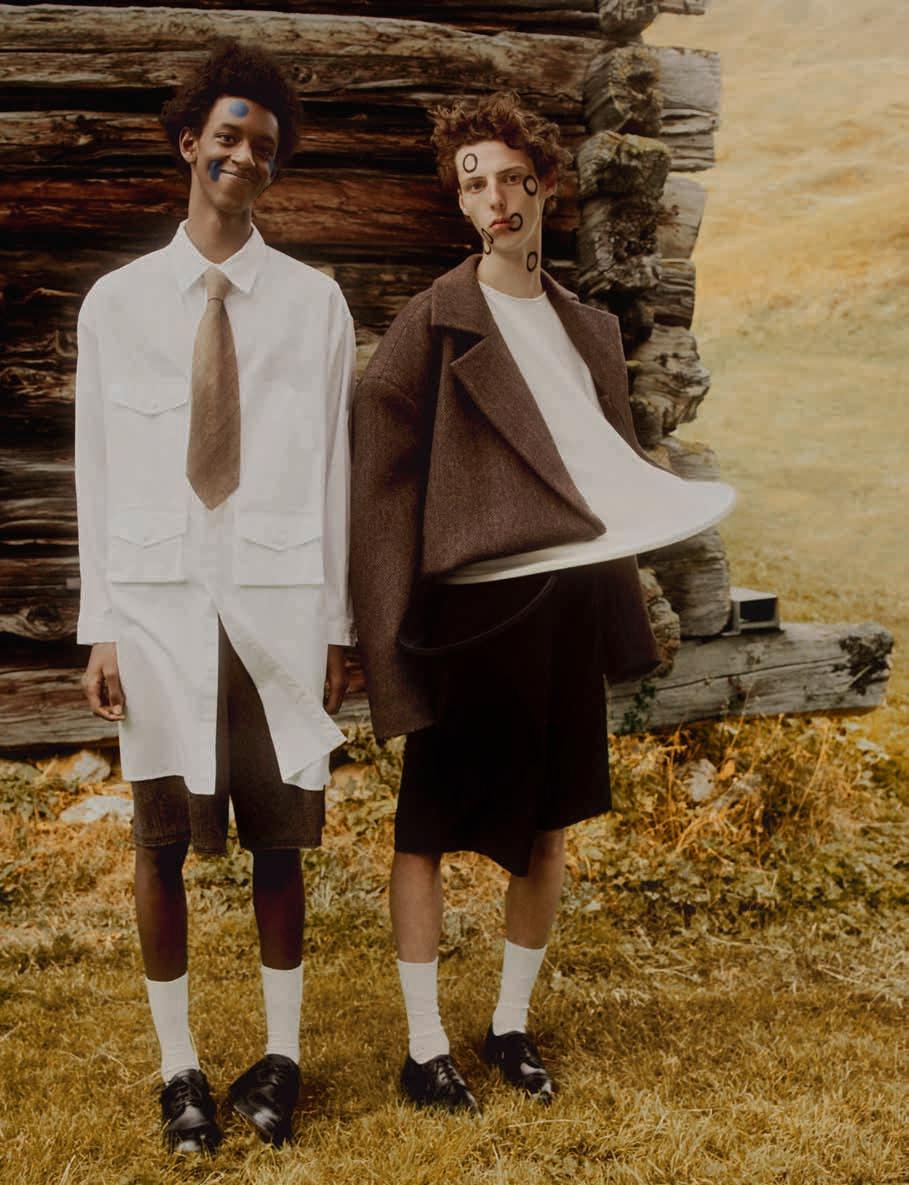

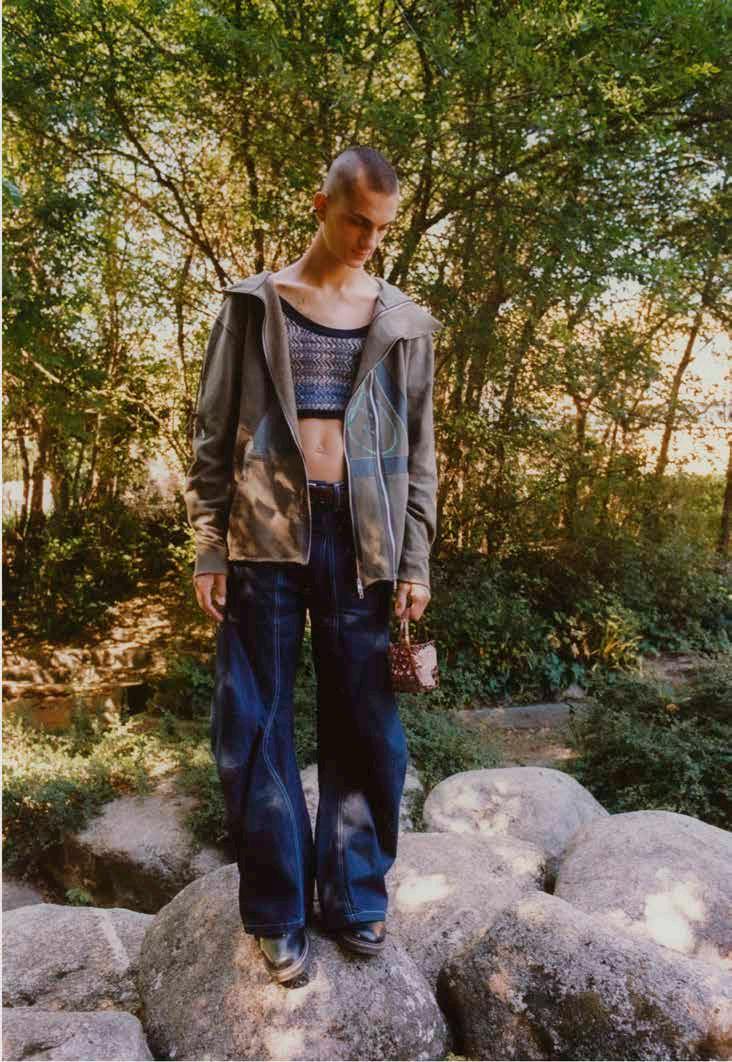

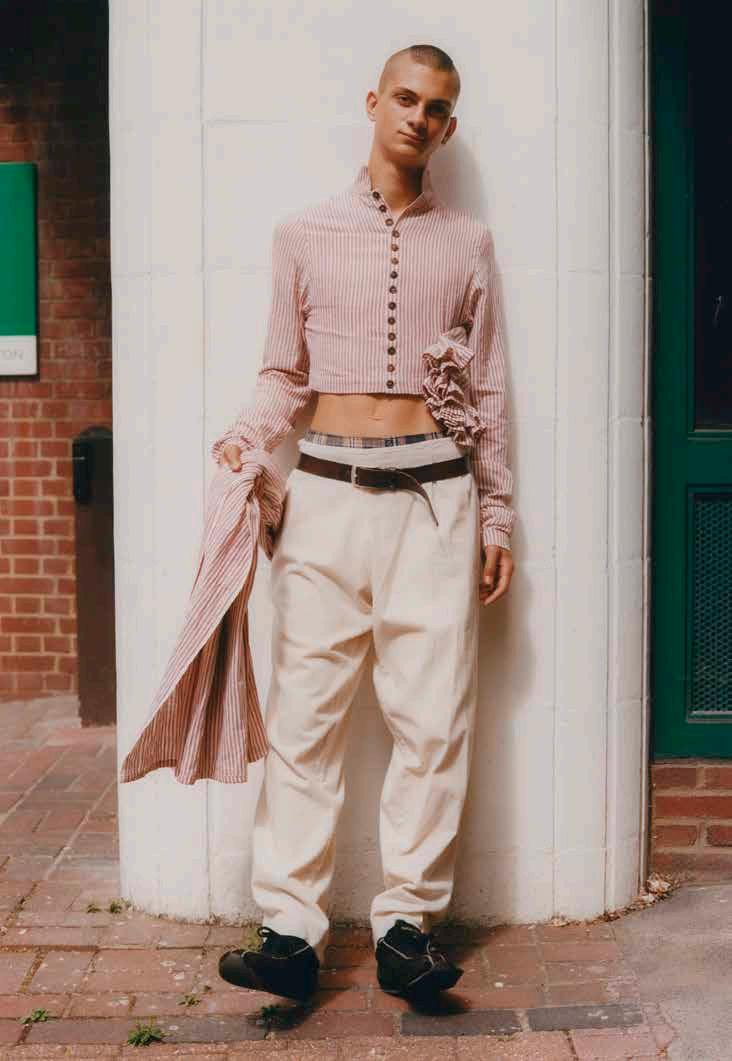

By Ethan Price. The next generation of sustainable fashion designers

Sillage: it’s a word used in perfumery to describe what is left behind when you walk by. The impact – it’s what keeps people talking when you leave the room. In fash ion, making an impression is everything. A good out fit should “change the way you walk; change the way you see yourself in car windows”, Central Saint Mar tins graduate Alec Bizby tells me. The main task of a fashion designer is to provide the wearer with impact –glamour, sexiness, absurdity – but this is rarely condu cive to having a lack of impact on the planet. Fashion is silly, whilst sustainability is serious (rightly so, on both accounts). The pairing is often uncomfortable, like sit ting on a bar stool while wearing a very short skirt. But designers Marie Lueder, Rina Hayashi and Alec Bizby manage to resolve this conflict.

With a desire for the “highest amount of creativity with the lowest amount of environmental impact”, Biz by’s entire MA collection cost no more than £100, made entirely from “thrifted curtains, curtain linings and bed sheets”. The used fabric came with its own personal ity – “stains, rips, wear and tear all add to the beauty of

the final garments” – and what emerged was a process that instead of hindering Bizby’s creativity, enhanced it. “Thrifting material means you have to make changes to your plans… It keeps the designs fluid until the final stitch.” Bizby draws inspiration from historical peasant clothing and farmers’ workwear, folk dancing costumes and Welsh ladies’ hats. All pieces are one-of-a-kind, with Bizby having no intention of creating duplicates. “My final goal is to have a tiny brand that makes oneoff pieces for people, which can then be turned into something else afterwards.” He believes this approach is the way to a sustainable future for fashion, but noth ing will change unless large corporations begin to make proper steps towards sustainable practices. “They have to be dedicated to sustainability root and branch, small changes within these huge companies are not enough to make a difference. Capitalism and profit will turn this planet to ashes.”

Also abandoning mass production and focusing on traditional Japanese craftsmanship, Rina Hayashi’s Cen tral Saint Martins’ BA collection inhabits a space between

Portfolio66

06 Photography Pablo Escudero Styling Julie Velut Casting Ethan Price

67All clothing MARIE LUEDER

Portfolio68

Jacket MARIE LUEDER Trousers MARIE LUEDER Top RINA HAYASHI Ear cuff KKRREEIISS x MARIE LUEDER Bag RINA HAYASHI Shoes DR MARTENS

clothing and the unexpected sculptural forms that appear in everyday objects. During a road trip across her native Japan, Hayashi became “fascinated by tra ditional crafts rooted in each area”. The resulting gar ments feature dead-stock and second-hand materials from both Japan and the UK (rice paper, sasawashi paper and bamboo for garment construction, alongside Brit ish hand-spun merino wool and viscose) and a focus on techniques that are rapidly being forgotten. “For my sakabukuro chaps, I up-cycled 50–60-year-old Japanese seamless bags which are used for making sake”, she tells me. Hayashi sourced the bags from her grandfa ther’s family, and dyed them using kakishibu, a tradi tional persimmon tannin varnish which continues to darken over time when exposed to sunlight, highlight ing the beauty within the ageing process, and Hayas hi’s love for the old and used. Garments are already ‘fixed’ before being broken or aged – “I use the ikkanbari technique on my sculptural pieces which is a tra ditional way to fix bamboo baskets, like darning on the basket with rice paper.” For Hayashi, sustaina ble practice is linked with taking care of what already exists and the ability to repair and remake from used materials – she loves knitwear for its inherent flexibil ity (it can be deconstructed, re-knitted, and “reborn as new”). Hayashi’s grandmother was a freelance knitter, encouraging and pushing Hayashi with her BA collec tion when the designer wanted to give up, but it was their talks that Hayashi valued the most – ultimately, they were “just girls who love knitting”.

69

Top: Top RINA HAYASHI Trousers RINA HAYASHI Skirt Stylist’s own Bottom: All clothing MARIE LUEDER

“As I grew up in the countryside,” notes Marie Lueder, “I feel very connected to nature and mother earth in a spiritual way and think about the loss of the connec tion between Gaia and us humans.” Lueder considers the environment throughout every level of her design process – using CLO 3D instead of paper or calico in order to prototype, up-cycling and using dead-stock –while also balancing the emotional and physical desires of her customers. The outcome of a practice that cen tres “passion rather than survival, asking rather than knowing”, Lueder’s clothes are intended as physical creations that provide the wearer with the “mental armour for their survival – for every day and our future.”

Lueder began up-cycling during the first lockdown of 2020, taking models’ unwanted garments and creat ing fresh, one-off pieces. Lueder describes the restric tion of up-cycling as a thrill: “You had just one chance to make the garments rather than working from scratch and making multiple toiles.” Lueder trained as a tailor at Hamburg State Opera, before studying at the RCA and going on to an accelerator programme for sus tainable leadership at Cambridge University in 2021. Lueder believes up-cycling can be the way forward for the industry – “using what is already there but still feeding into that desire to buy something new.” I men tion sillage, already knowing that Lueder created a per fume with Paul Guerlain and IFF; what impact does she want her garments to have? “I want the people to gather, to be able to rethink and regenerate (gender, bodies...) if they feel scared and depressed about the future. A super-positive and excited outlook into their future… that’s what I want them to feel.”

Portfolio70

Hairstyling Tommy Taylor

Make up Iga Wasylczuk

Models Harry at Head Office MGMT, KC at Head Office MGMT, Medea at TIDE Agency

71Top ALEC BIZBY Trousers ALEC BIZBY Ear cuff KKRREEIISS x MARIE LUEDER

Portfolio72 Top ALEC BIZBY Trousers ALEC BIZBY Belt Stylist’s own Shoes Stylist’s own

73All clothing RINA HAYASHI Earrings Stylist’s own Shoes Stylist’s own

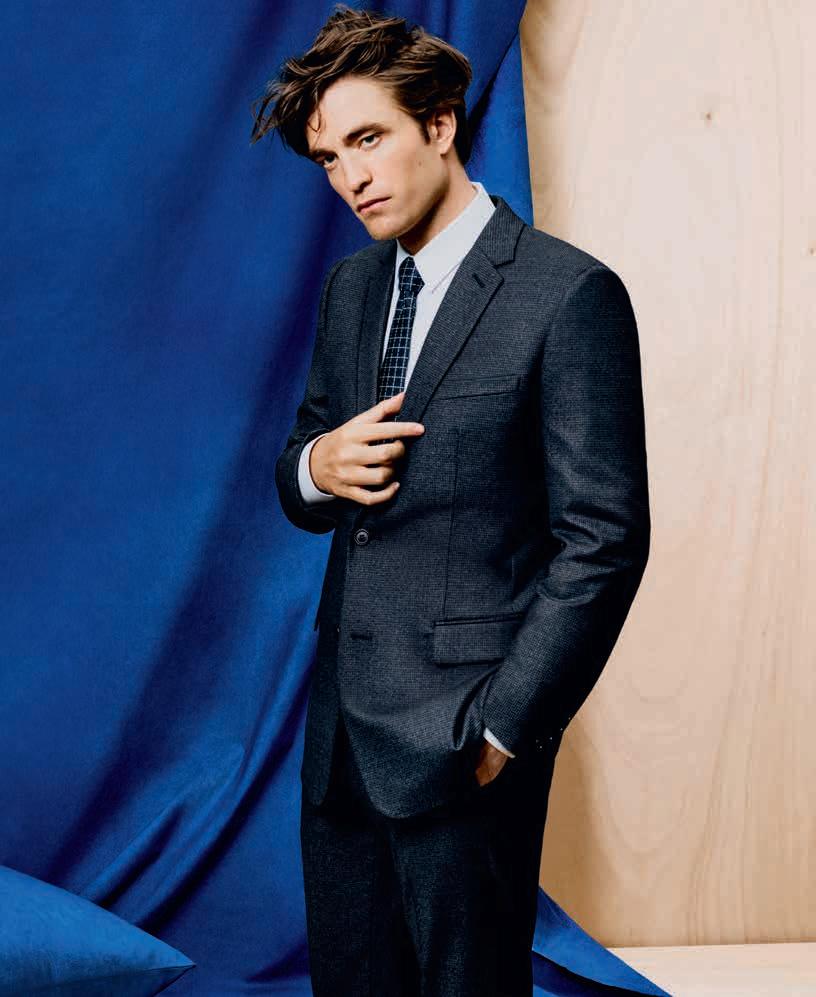

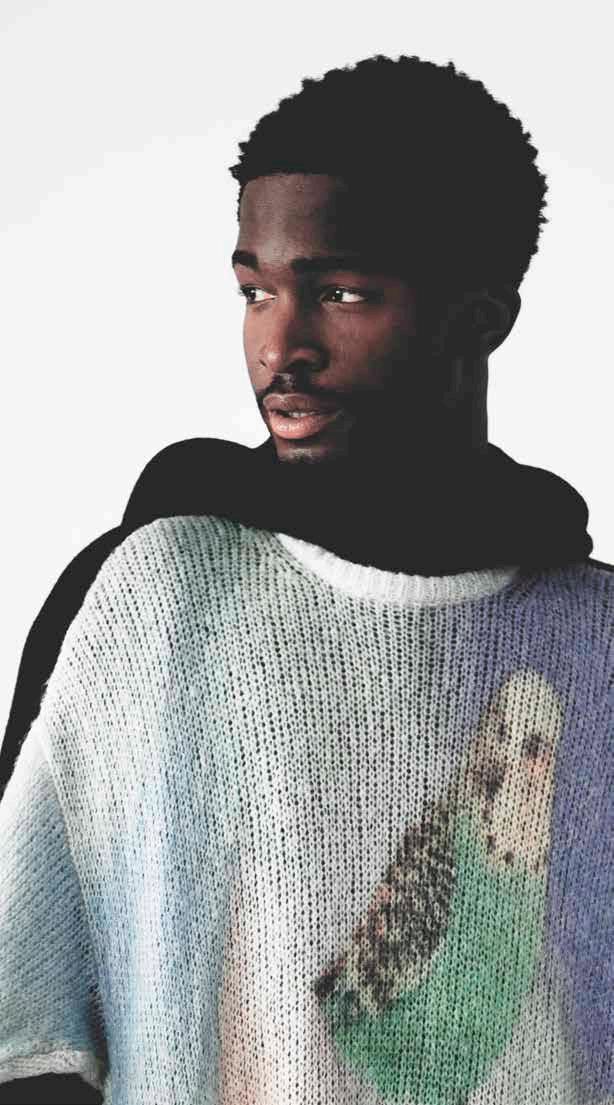

CALIFORNIA COUTURE

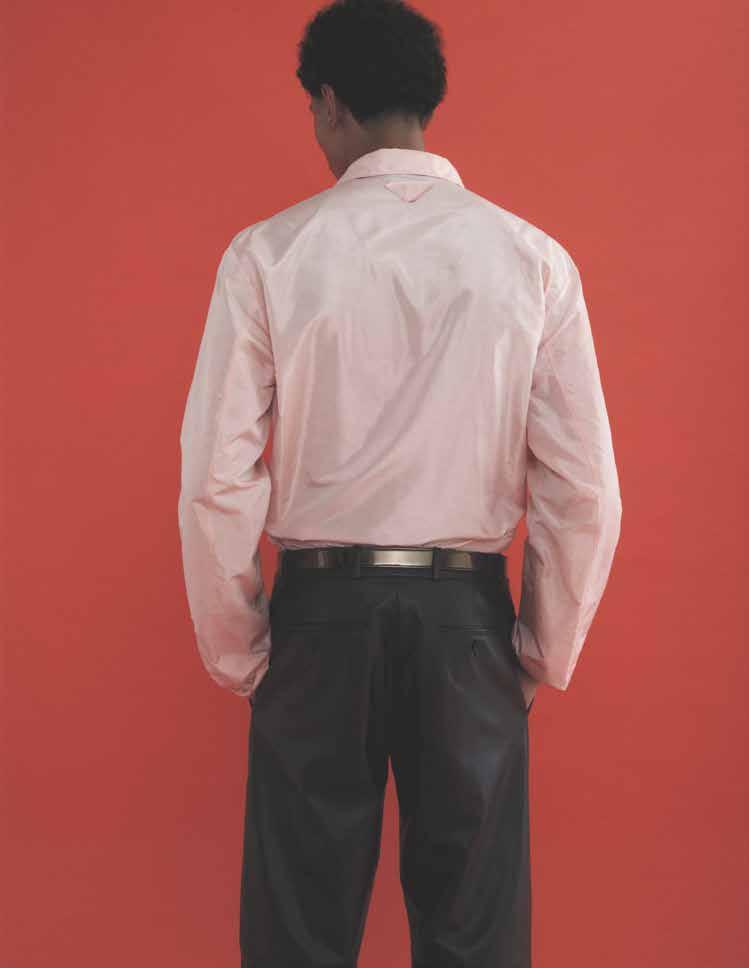

By Hannah Williams. Paris meets LA in Dior and ERL’s SS23 collaboration

It is a Thursday evening in Venice Beach when the Dior x ERL Spring 23 collection is shown, and a nylon wave is rolling, languid and cerulean, down Windward Ave nue, towards the ocean. In the crest of the wave, the audience watches models walk down its parted centre: hot-pink shorts, bare chests, fur saddlebags, logo tube socks pulled far up above untied skate shoes. Suspended above them the Venice sign glitters in the twilight, the words ‘ERL’ and ‘DIOR’ strung underneath.

Emblazoned in green and orange glitter on the fronts of slouchy polo-necks, ‘California Couture’ acts as both a title and mission statement for the collection. It’s Par is-meets-LA, Dior-grey satin suits teamed with crystal brooches and embroidered sweatshirts, quilted jackets slung over pearl-encrusted knits. There’s a playfulness here, a winking irreverence that nevertheless pays sin cere tribute to the history of Dior. This desire to push boundaries is in keeping with Kim Jones’ tenure as artis tic director of Dior Men’s, with previous collections tak ing inspiration from references as eclectic as the Beat poets, Travis Scott and Parisian statues. Jones talks about how, for this collection, he “wanted to work with some one in a different way; I wanted somebody to see Dior from a different angle.”

In this light, a collaboration with Eli Russell Linnetz, creative director of ERL, feels entirely natural. Born and raised amongst the surfers, skaters and starlets of Ven ice Beach, Linnetz’s chameleon-like ability to turn his

hand to anything he desires – assisting David Mamet on Broadway, directing the music videos for Kanye West’s ‘Famous’ and ‘Fade’, designing the set for Lady Gaga’s Enigma tour, or voicing a character in The Emperor’s New Groove – makes him the perfect choice to embody Jones’ vision of a Dior Men’s that fuses old and new, high art and pop culture, street fashion and couture. Linnetz describes how he and Jones began by exploring the 1991 Dior archive, the year of his birth. As he puts it, “this was during Gianfranco Ferré’s period as artistic director and was a part of the history of Dior that felt completely fresh for both Kim and me.” It’s here that the collection’s maximalism originates: “a coming together of chaos and perfectionism. There’s a collision of moments in time and history throughout the collection, of cross-gener ational and spatial meetings in time.”

The result is a synthesis of downtown Venice Beach spontaneity and 8th arrondissement refinery, an all-Amer ican dream of Paris: surf-inspired shorts, lived-in knits and loose, silky fabrics in the colours of a beach sunset – pale pink, dusky blue, and an intense, heart stopping fuchsia. Yet all the facets that make something unmis takably, quintessentially Dior – an unparalleled flair for tailoring, the iconic Cannage motif – are there, ren dered this time in satin and leather quilting, in flowing pastel suits and padded skate shoes. It is, as Jones says, “both familiar and revelatory; reaffirming why we both dreamed about working in fashion in the first place.”

Portfolio74

07

75

Styling Karlmond Tang Model Feranmi Ajetomobi at Wilhelmina Grooming Charlie Cullen Casting Marqee Miller Photography assistant Eduardo Guida

Photography Gaëtan Bernède

IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

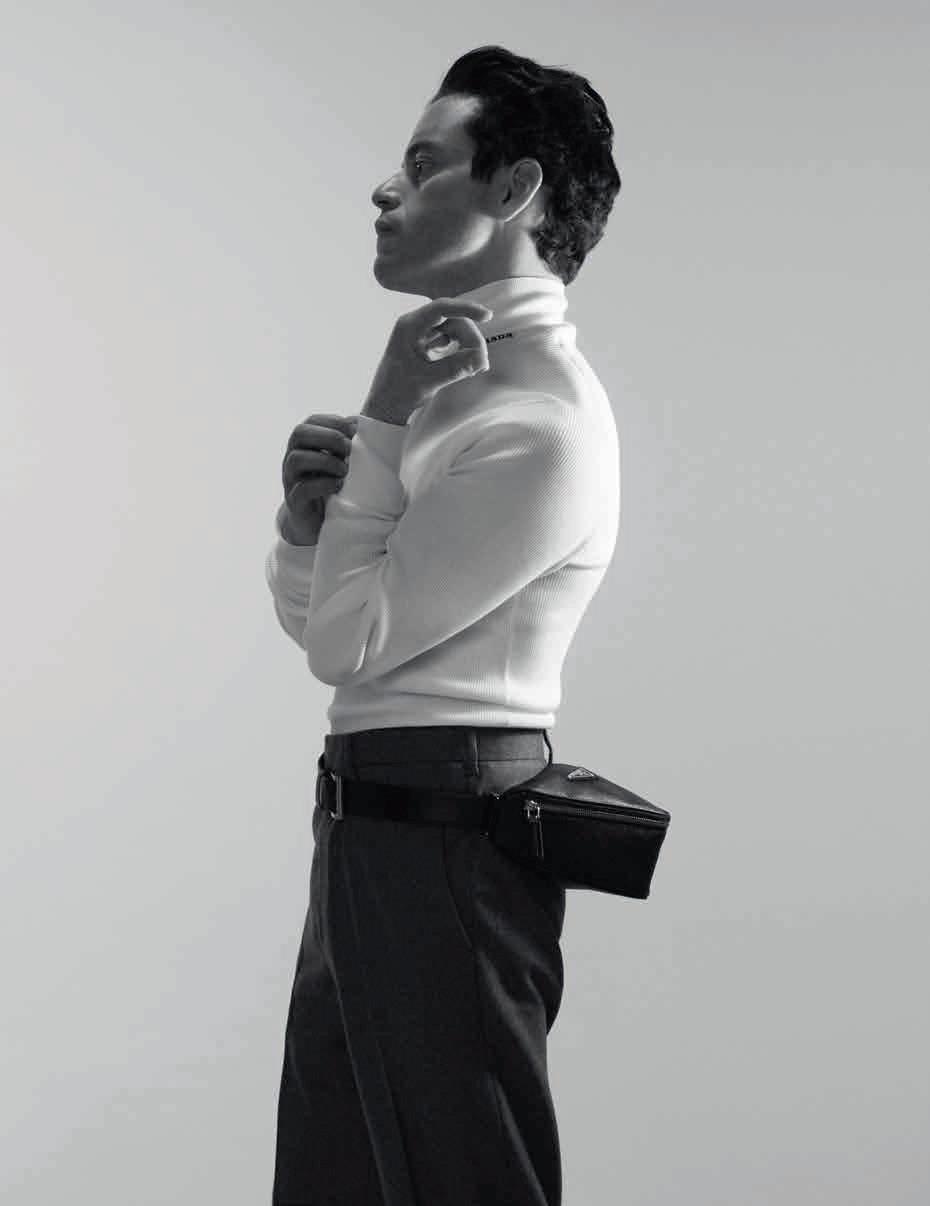

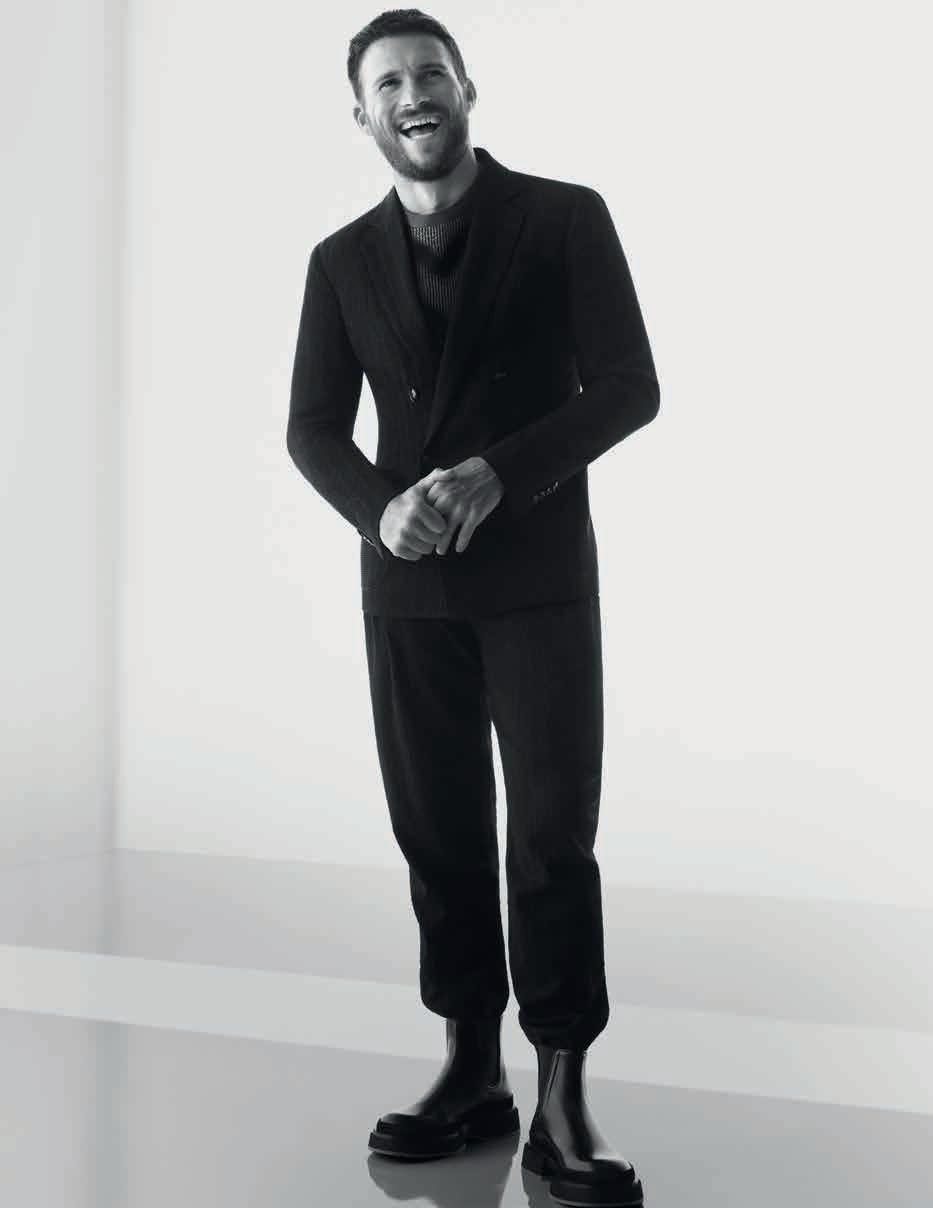

By Dylan Holden. Stefano Canali on modern masculinity and inner beauty

Portfolio76 Styling Georgia Thompson

08

“Though we travel the world over to find the beautiful,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson, “we must carry it with us, or we find it not.” Found in one of the American poet’s many essays on art, this line touches on an aphorism that although may sound mawkish to the jaded cynic, rings true. Namely, that inner beauty illuminates the individual from within, leading them to encounter so much more of life. This concept lies at the heart of Canali’s AW22, a modern take on masculinity that celebrates beauty in the broadest sense of the term, both its “intrinsic and extrinsic values.” With this collection, the storied Ital ian house is dressing the gentleman of today; one who is kind, confident and composed, choosing dialogue over monologue. An accompanying campaign titled ‘Through His Eyes’ has selected talent expanding on these values – acting as ambassadors for Canali’s vision – and begins with CEO Stefano Canali. To mark the editorial series, Port spoke to the head of the family-run business about the hidden treasures of Torino and his hopes for the next generation.

How do you think social media, with its proliferation of images, has impacted ideas of beauty, inner or otherwise?

This is a controversial topic. Social media is an extremely powerful medium. The accessibility of information has spread the concept of ‘inner beauty’ by generating greater awareness, activism, and participation on the part of new generations on very important issues that promote inclusivity. However, we cannot deny that it can also create and spread unrealistic aesthetic ideals.

How does AW22 inform and interpret the new phase of modern masculinity we’re in?

The AW22 collection, with its new, more relaxed approach to sartorial sensibility, introduces innovative items into the male wardrobe such as the cuff jacket with knitted details, which combines the softness of knitwear and the cleanness of tailored shapes. Or the new sahariana safari jacket in cashmere – that paired with matching trousers creates one of the many ‘smartorial’ suits. I feel it is this casualness, this deconstruction, that runs through the collection and conveys both softness and character that can be considered the sartorial expres sion of the new masculinity. Where suiting no longer needs to be armour.

What are some non-fashion causes close to your heart?

Anything related to environmental sustainability. My personal curiosity and sensitivity lead me to take an interest in technological innovations involving experi mental alternative energy sources, from deep geother mal to nuclear fusion to recycling plants.

Who are some of the ambassadors for this project?

For our ‘Through His Eyes’ project we have selected those who devote part of their lives to beauty in the broader sense. They describe how in their business or in their personal lives they promote beauty, positivity, kindness, care and respect. These include, among oth ers, Thomas Ermacora, a regeneration architect and tech-for-good entrepreneur focused on urban sustain ability and community resilience. Having worked with key iconoclasts in urban futures such as Frank Gehry, Jan Gehl, and John Norquist, he stands as one of the new strategic leaders helping transition cities towards more socially inclusive and resource intelligent designs – paving the way for increasingly distributed and opensource societies. Giampaolo Grossi is another, the Gen eral Manager of Starbucks Italy and co-founder of ‘Lusso

Gentile’, an editorial project that has “care, respect and love” as its mantra and which aims to inspire – young and old – through the words and works of visionaries who have shown great talent in their professional and personal spheres. Our photographer for the campaign, Oddur Thorisson, is also part of the series. Oddur is best known for his work with Condé Nast Traveler and he lives with his wife, their eight children, and nine dogs in Piemonte, Italy. His life is devoted to beauty in his photographs and to his family, above all.

Has anyone close to you – family or friends – expanded your understanding of inner beauty?

I was fortunate enough to have parents and friends who taught me through daily examples what really counts in life, the real source of happiness: gestures of love, sol idarity and respect that give meaning to our work and relationships with others, far beyond success and finan cial well-being.

Why was Torino chosen as the backdrop for AW22’s campaign?

What better backdrop for a campaign revolving around the concept of inner beauty than Torino, the city of hid den treasures. Only a city like Torino, that manages to hold so many jewels in its bosom and make such a dis creet and gracious gift of them to its citizens every day, can call itself rich. But rich in rare treasures coloured by all the nuances of the human soul: from spiritual ones, like the Holy Shroud, to aesthetic and cultural ones, such as Guarini’s architecture. There are even treasures that delight the senses, the Turin inventions of gianduia and bicerin

What do you think reveals a person’s inner beauty?

I think two things above all others: care and respect. In everything we do. For other people, for the planet. In business and in one’s personal life. There cannot be inner beauty without these.

How has your understanding of masculinity changed over the years?

I believe that masculinity has gradually softened, is less authoritarian and more authoritative in its assertion. Less bound to clichés of the past, of a phantomatic alpha male. More open to considering kindness as a strength, instead of a weakness.

At the moment, ideas around beauty and masculin ity can be warped and weaponised. What gives you hope for the future, and the next generation?

Precisely the next generation is what gives me hope. Our children, despite the countless sources of disturbance, are also in contact with many positive stimuli; from a very young age they are confronted with the whole world, with cultures and disciplines different from their own. And this helps them to develop greater understanding, discernment, and awareness much earlier. This is then reflected in better capacity of taking responsibility when it comes to issues that affect our lives, such as ecology, gender equality, body positivity, minority rights – to name but a few. Obviously, it is up to us to ensure that our young refine their analytical capacities and sensitiv ity, but my hopes are high.

77Photography Scott Gallagher

SELLE ROUGE

By Dylan Holden. The latest chapter in Hermès’ illustrious equestrian history

Thierry Hermès’ first customer was a horse. So goes the long-running joke at the eponymous French house, which first began creating harnesses and bridles in 1837. The gifted leather worker’s distinction was twofold; his deft dual needle stitching with waxed linen threads could only be done by hand, and the custom harnesses were as light, exact and respectful to the animal as possible, uncommon at the time. Soon, the family-run work shop was winning first-class accolades at Paris’ exposi tions universelles, as well as fielding the needs of noble men, emperors and tsars. And, while Hermès went on to gift the world with ready-to-wear and accessory icons – the carrés silk scarf, the Birkin, the Kelly – it remains synonymous with equine élan

No item better encapsulates both its storied past and progressive advance than the saddle. For over a century, artisans at 24 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré have per fected the point of osmosis between rider and beast. Today, the bespoke service begins with an expert observ ing the latter’s character, temperament and mobility. To harmonise the pair’s anatomy and morphology, a skel etal measurement tool then records a hundred contact points on the horse’s back. This precise, unique “foot print” will be adjusted and adapted to encourage the most natural movement, alleviating any possible ten sion and trauma. Crafted by a single person, each one takes roughly 30 hours to complete, and like all good design, their engineering is so intuitive they feel inevi table, almost imperceptible. Yet, how striking a Hermès saddle is, none more so the new Selle Rouge

Oiled in the house’s emblematic colour, then anointed with glycerine soap to nourish the sustainably sourced leather, the ‘Red Saddle’ marks the sum of the atelier’s knowledge.

Created for show jumping and working on the flat –informed by numerous discussions with partner rider and Belgian Olympian Jérôme Guéry – the slim fork of its tree is the result of three years of tests, with car bon losing out to the noble material of beech wood for its suppleness and shock absorbency. Illustrating that its inside is equal to its outside, its mastery is revealed through a visible interior assembly.

“Closeness, balance, stability, comfort and safety are constant challenges when designing a saddle,” notes Ly Lallier, equestrian métier director. “Thanks to a series of innovations, the Selle Rouge rises to them all… It has a deep seat, very open to ensure a comfortable position; the skirt is incorporated into the flaps and the blocks are recessed to avoid any superfluous thickness hampering movement. The single seam punctuated by backstitch ing in saddle-stitch, known as ‘fil-au-trait’, also avoids any unnecessary friction and contributes to its techni cal and aesthetic prowess.”

Émile-Maurice, the grandson of Thierry, summa rised the business’ ethos in the 1920s as “leather, sport, and a tradition of refined elegance”. Much has changed since those words were uttered, but thankfully, Hermès hasn’t cantered far.

Portfolio78

09

79Photography Gaëtan Bernède

THE LAST BASTION

By Andrew Edmunds. The late, great proprietor of the eponymous Soho haunt looks back at over 35 years of business

I rather accidentally bought number 46, Lexington Street. My prints and drawings business was next door, and my landlord since 1973 – Sutton Estates – looked after their parcels of London with paternalistic and benevolent neglect. Before moving in I had to be inter viewed by a gentleman resembling a country solici tor, in a short black coat and striped trousers, to see if I was a ‘suitable’ tenant. They owned the half of Soho where there were no sex shops and they were very wor ried about the fact I was also a book dealer. Presuma bly they thought I had a plan to sell rare pornography. I had originally ended up buying 46 as well as 44 because of complicated fire escape routes with the rear build ings. Simply wanting to secure the print shop I ended up with four freeholds – one of the only sensible things that I have ever done.

In 1985, 46 was a bar called The Last of Cheri. It had the Lincrusta wallpaper which survives to this day, but everything was painted bright pink. The predecessor only sold German wine, so, although they had some surpris ingly good Auslese, it too hadn’t been a huge success. One Friday the young woman who owned it said, “if you give me £10,000 for the lease it’s yours.” I exchanged with her on the Monday. She used the money to get a pitch on Berwick Street Market for a fruit and veg stall, but it didn’t last long either. That’s how Andrew Edmunds Res taurant began.

I have plenty of stories about the restaurant but not all of them can be printed. I remember someone’s trousers being eaten by one of the manager’s dogs, regular inci dents of hair going up in flames during the ’80s, and a louche moment when two customers thought they were being discrete when they disappeared into the lavato ries, only to emerge to a full round of applause. A child has been christened Andrew, in homage to a first date here. One member of staff has been with us for 25 years. A particularly sweet memory stands out; one evening our framed William Hogarth etching – a knife and fork flanking a pie, which acts as our logo – was pinched. 20 years later, days after a review in the Guardian, it turned up in a jiffy bag with a Cambridge post mark. It would have been funnier if it was from Oxford, courtesy of some guilty imbecile from the Bullingdon.

We remain one of the last bastions of ‘Old Soho’. For some, the term wistfully calls to mind watching Francis Bacon get extremely drunk at The Colony Room. But for

many, it meant artisans and specialist shops; solid pro duce stalls that supplied the restaurants. The small 18th-century buildings nearby were multiple occupa tion and once filled with outworkers for Bond Street and Savile Row. We had four butchers, a game dealer, and a large fishmonger within walking distance. Tom Scott, the jeweller, is one of the few survivors from that time. The fundamental change over the years, I suppose, has been landlords being motivated by greed, rather than any sense of community.

We’ve kept our decor close to how we found it for two reasons: idleness and economy. It’s so shabby now that high fashion wants to use it for photo shoots; we’ve gone full circle. I’m happy to say there is an extraordi narily wide age range, a new generation who find us romantic, and old farts like me who simply come here because the meals are sensibly priced. A good top and tail. Our offering is modern European and what one would cook at home, pulled from the bottom of the AGA. Whole baked mackerel, calf’s liver, roast fennel and celeriac, ox tongue or heart. Right from the begin ning, we’ve been using animals almost in their entirety –like St. John – without thinking about it as anything par ticularly unusual. We also boycott all Scottish salmon, because the farms are destroying wild spots.

Suppliers have changed over the years. Nothing comes from the market anymore, except for milk from Soho Dairy, who have single handedly saved the Berwick Street Market. We still use Algerian Coffee Stores & Ger ry’s in Old Compton Street, otherwise I am afraid that everything is delivered now rather than walked round.

Our reputation for wine in part comes from the fact we mark almost as though it was a corkage. Unlike other establishments we do not simply times the price by four, because there is nothing sadder than having gorgeous food and only ever being able to buy the third wine on the list. We try to counter increasingly idiotic prices, but I am afraid that the more you spend the cheaper it gets!

I would be spoilt for choice if I were to have a final meal here. Perhaps a summer pudding, and following in the footsteps of Napoleon in exile, a bottle of Klein Constantia.

As told to Tom Bolger. Mr Edmunds sadly passed away shortly after the interview. We will be raising a glass to him in his won derful restaurant

Portfolio80

10

81Andrew Edmunds. Photography Benjamin McMahon

Ingredients

Braised Lamb

1 lamb shoulder

4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

1 onion, peeled and roughly chopped

2 carrots peeled and in 2.5cm chunks

4 sticks of celery in 2.5cm chunks

2 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed Rosemary, chopped

300ml chicken stock

300ml red wine

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Buttered Celeriac Medium celeriac 50g butter Oil

Handful of thyme, chopped 5 sliced garlic cloves

Salsa Verde Sauce

Small bunch of chervil

2 small bunches of flat-leaf parsley

1 small bunch of mint

1 small bunch of dill

3 tsp Dijon mustard

40g small capers, drained, rinsed and roughly chopped 200ml extra virgin olive oil

40g chopped cornichons

Heat the olive oil in a tray, season the lamb with salt and pepper and then brown it off. Remove it from the tray with a slotted spoon.

Add more olive oil to the tray and fry the onion to soften, but not brown. Next add the carrots and celery and lightly brown. Then add garlic and rosemary. Put the lamb shoulder back in the tray, pour over the stock and wine and bring to bubbling. Season with salt and freshly ground black pepper. Cover with parchment and foil and cook in the oven for 4 hours at 1500C.

Before the lamb is ready, peel the celeriac and cut it into chunks. Heat half the butter in a deep frying pan and let it brown a little, add the rest of the butter, thyme and garlic, then the celeriac, and fry it, stirring the pieces often until they are golden and tender in the centre, about 20 minutes. Season well.

Chop all the salsa verde herbs, add into oil, with capers, cornichons and mustard. Season to taste.

Plate everything up and finish with a good dollop of salsa verde.

Portfolio82

Photography Benjamin McMahon

Braised Lamb with Buttered Celeriac

83

By Tara Joshi. Mali comes to Texas in Vieux Farka Touré and Khruangbin’s new collaboration

For years, singer and guitarist Vieux Farka Touré had been wanting to create a project in tribute to his late father, Ali.

Depending on your areas of interest when it comes to music, Ali Farka Touré’s name is one that will either be deeply familiar to you, or perhaps one you’re not aware of at all. For the uninitiated: Touré was a Malian multi-instrumentalist and singer who is largely con sidered to be one of the greatest guitarists of all time; often called “the African John Lee Hooker”; sometimes even “the godfather of the desert blues”, he played with a rich, melismatic sound which would resonate across the globe like wind sweeping over sand dunes.

Vieux had been hoping to approach a band in the West to collaborate with on a record of reinterpretations and help to share the music with a wider audience than ever before. It was Vieux’s manager who suggested he check out psych-tinged Texas trio Khruangbin, who have long been known for their lush channelling of sounds from around the world. Soon after, Vieux caught one of their shows in London and was convinced they were the per fect group for the project. It was a sentiment which was solidified when he met them: “They met the criteria of what Ali himself looked for in collaborators in his life,” Vieux tells me, “Their popularity did not prevent them from being kind, humble and courteous.”

Ali is not your standard album of cover songs. For starters, Vieux did not show the band the music they would be recording before they entered the studio. “I met Vieux for the first time and we just kind of hit the ground running,” explains Khruangbin bassist Laura Lee. “He didn’t want us to know what we were play ing before we played them, because he wanted it to feel raw.” Although Khruangbin had all been inspired by Ali’s work, that was largely irrelevant to the process: Vieux didn’t give them the song titles until they were done, and it transpired some of the tracks were unre leased: “Towards the end we heard the actual songs and were like, ‘whoa!’” Lee laughs, “Because they were very different tempo and feel-wise – but I’m happy we did it the way we did.”