A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF HOUSING ALLOWANCE DESIGN:

Policy Reforms to Reduce Administrative Burden in the Housing Choice Voucher Program

January 2023

Policy Reforms to Reduce Administrative Burden in the Housing Choice Voucher Program

January 2023

Participants in the Housing Choice Voucher program experience significant administrative burden throughout the program’s three main phases: demonstrating applicant eligibility, finding a rental unit and receiving unit approval. The consequences of administrative burden’s learning, compliance and psychological costs throughout this process are significant: the percentage of households successfully leasing a unit with their issued voucher is below 50%.1

This report uses comparative analysis to make recommendations to reduce administrative burden in the Housing Choice Voucher program. The authors utilize evidence from housing allowance programs in Germany and the United Kigdom — alongside policy innovations in the United States — to ground recommendations in examples of policies that have worked elsewhere. When possible, we prioritized reforms through the executive branch over the legislative branch and focused on reducing administrative burdens faced by program beneficiaries over administrators.

Our recommendations align with the program’s three phases:

‣ Public Housing Agencies (PHAs) should streamline the application process for vouchers to ensure applicants do not need to provide duplicative or unnecessary information. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) should publish streamlined application templates.

‣ HUD should enable PHAs to issue vouchers prior to receiving third-party verification of eligibility information. HUD can enable PHAs to use self-attestation, fact-based proxies or categorical eligibility to screen for initial eligibility.

‣ Congress should expand the Housing Choice Voucher program to make it a means-tested entitlement program in which every household with an income at or below 30% of the area median income receives a voucher.

‣ Congress should expand eligibility for housing choice vouchers to all U.S. residents including immigrants without legal status, especially if the program were made universal.

‣ Congress should eliminate categorical exclusions for those with criminal convictions, especially if the voucher program became universal. In advance of that change, HUD should update its guidance to PHAs on criminal background screening, limiting their ability to reject applications from those with criminal justice involvement, beyond the minimum requirements mandated by current law.

‣ HUD should eliminate the requirement that PHAs reduce the initial payment standard if a family rents a unit with less bedrooms than initially scoped.

‣ HUD should prorate for noncitizens at voucher issuance and investigate feasibility of eliminating proration all together.

‣ PHAs and local government entities should provide voucher holders with resources for their housing search, including providing navigators or a directory of voucher-affordable rental listings in a variety of neighborhoods. Congress should appropriate funding for HUD to increase administrative fees to facilitate providing search assistance.

‣ Congress should appropriate funding for PHAs to test and strengthen enforcement of existing fair housing and source of income discrimination laws.

‣ HUD should issue guidance that names source of income discrimination as a potential fair housing issue for jurisdictions to consider. HUD should mandate and fund PHAs to collect data on whose housing applications are rejected by landlords, which would strengthen PHAs’ ability to determine how source of income discrimination is disproportionately impacting protected classes.

‣ HUD should provide additional administrative fees to PHAs to implement landlord incentives, including providing security deposits for tenants and repair funds for landlords to address damages.

‣ HUD should permit PHAs to pre-inspect units and allow move-ins to units requiring non-lifethreatening repairs.

‣ HUD should limit the number of scheduled re-inspections by PHA inspectors to once every two to three years. PHAs should limit the number of unscheduled inspections to limit the potential for punitive action.

‣ HUD, state governments and local governments should invest in new and existing tax rebates or other incentives for rental home improvements, conditional on accepting housing choice vouchers, to provide additional incentives for landlords.

‣ HUD should create a new “Cash Assistance for Housing” cohort in their Moving to Work (MTW) expansion program to assess the efficacy of a cash-based, direct-to-tenant payment mechanism on reducing administrative burden.

The United States faces an affordable housing crisis with millions of households struggling to pay their rent. In 2021, more than half of all renters nationwide (nearly 21 million people) spent over 30% of their income on rent.2 And the need for affordable housing is heavily concentrated among people with low incomes and people of color: more than 60% of people in low-income households who pay more than half their incomes on rent are people of color.3

The nation’s largest form of rental assistance is the Housing Choice Voucher program (known colloquially as Section 8).4 More than five million people in 2.3 million families with low incomes use vouchers each year to help pay rent on the private market, generating a total program cost of $25 billion in 2020.5,6 The Housing Choice Voucher program is federally funded and administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which disburses funds to about 2,170 public housing agencies (PHAs) that administer the program at a local level. The program has three goals: to improve housing affordability for eligible households, to provide better living conditions and to allow voucher recipients to move to neighborhoods with lower levels of race and poverty concentration.7 Participating households receive a voucher to rent a home below a “payment standard that is the amount generally needed to rent a moderately-priced dwelling unit in the local housing market.”8 Renters must contribute 30% of their income toward rent, and the government subsidizes the remainder of the cost through payments sent directly to landlords.

This report limits its scope to one consistent category of challenges associated with the Housing Choice Voucher program: administrative burden. The existence of administrative burden in the Housing

Choice Voucher program is well-documented, with participants experiencing long waitlists and challenges finding units.9,10 This report uses a comparative analysis framework to make explicit recommendations to reduce administrative burden within the program. Our recommendations are based in lessons learned from innovations in rental assistance across the United States and from two international case studies, the United Kingdom and Germany. To this end, the report authors conducted interviews with housing experts in these two countries, and the findings from these interviews are referenced throughout the report. As this report was prepared in discussion with the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, New York City is acknowledged as a reference point throughout this analysis. However, the recommendations for this report are not specifically targeted to a New York context. Instead, the recommendations consider broadly how HUD, PHAs and local government entities can reduce administrative burden within the Housing Choice Voucher program.

This report analyzes the end-to-end process of securing and utilizing federal rent assistance, from application through voucher payment. First, the report defines administrative burden in its relation to the Housing Choice Voucher program in the United States. Second, it outlines the contexts of our primary international comparative cases: Germany and the United Kingdom. Third, it offers comparative analyses across these contexts to highlight how to reduce administrative burden across each phase of voucher program participation: applicant eligibility, unit search and unit approval. Lastly, it consolidates recommendations based on this analysis.

Households navigating the Housing Choice Voucher program go through a multi-step process, as pictured in Figure 1, across three main stages: applicant eligibility, unit search and unit approval.11,12 In the applicant eligibility stage, households complete a voucher application, are typically placed on a waitlist and participate in two interviews with a PHA after acceptance off the waitlist. During the search phase, households identify units that fall within an acceptable rent threshold, as well as landlords willing to accept them as tenants, within 60 days (although PHAs may allow longer). Finally, in the unit approval phase, PHAs determine whether the unit is reasonably priced and meets quality standards before executing contracts and issuing payments to the landlord. Throughout this process, households face substantial difficulty using their issued vouchers.

Recent estimates suggest success rates – the percentage of households successfully leasing a unit with the voucher they are offered – are below 50% on average and even lower for Black households and seniors.13

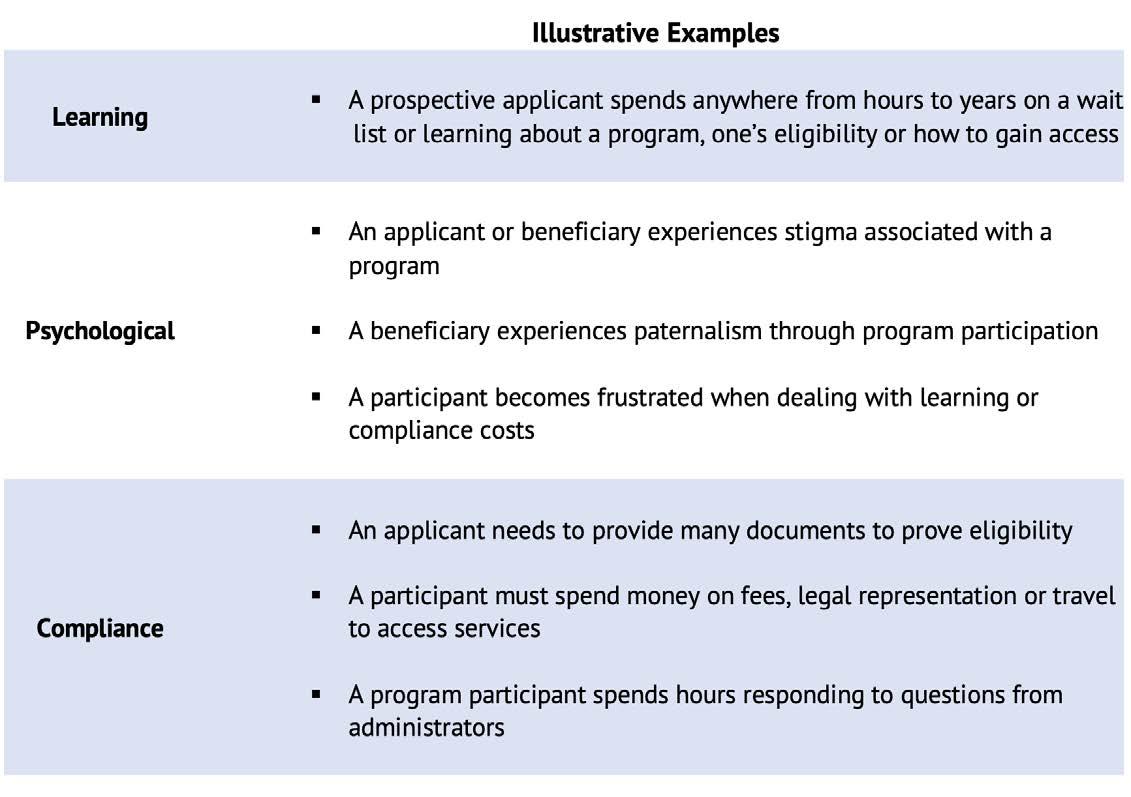

Across each of these three phases, the Housing Choice Voucher program is administratively burdensome for participants. Researchers from the Georgetown McCourt School of Public Policy define administrative burdens as “the learning, psychological and compliance costs that citizens experience in their interactions with government,” described in more detail in Table 1.14

In the applicant eligibility phase, there are substantial learning and compliance costs: households must

ApplicantEligibility

1.Household completes a voucher application

2.If application is accepted, the applicant is placed on a waitlist

3.Applicant participates in two interviews with the Public Housing Agency (PHA) after being moved off the waitlist

Unit Search (60+ days)

1.Household identifies units that fall within the acceptable rent threshold

2.Applicants must ensure landlords are willing to rent units to voucher holders

Unit Approval

1.PHA determines whether the unit meets price standards

2.Unit is inspected for quality

3.Voucher holder leases unit and PHA issues payments to the landlord

learn about the program, assess their eligibility, apply to the program (if the PHA has opened its waitlist) and provide documentation on income and citizenship status. Most of this phase involves waiting to apply and waiting to get to the top of the waitlist: among the 50 largest PHAs, the average family spends 2.5 years on the waitlist.15

In the search phase, households face the psychological costs of navigating the private rental market to find eligible units and facing substantial discrimination. In the largest, most comprehensive test of voucher discrimination to date, HUDsponsored researchers found that finding eligible units is time-consuming: for every 39 ads screened across five large cities, just one was potentially eligible based on size and rent requirements.16 They

also found that denial rates were substantially higher for voucher holders.

Finally, in the unit approval stage, landlords face substantial learning and compliance costs related to inspection and paperwork processes. Among a small sample of landlords with units in low-rent markets in Baltimore, Dallas and Cleveland who do not rent to voucher holders, their most commonly cited reasons for not participating were any inspection issues (51%), paperwork and bureaucracy (41%) and lack of PHA support during tenant conflict (41%).17

Our policy recommendations are rooted in an analysis of housing allowance implementation in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. International comparisons are valuable as we imagine how the Housing Choice Voucher program might be reformed and what aspects of this program should be maintained. The strengths and limitations of each nation’s rental assistance programs are highly dependent on the housing markets and regulatory landscapes they operate within. This context is essential to understanding how international service delivery strategies might be successfully adapted to the United States. The following basic comparison of each nations’ housing market characteristics, tenant protections and housing assistance programs will contextualize the analysis that follows.

While most households in the United States and United Kingdom own their homes, Germany is a country of renters. As seen in Figure 2, more than half of German households rent their homes, and the proportion is as high as 80% in some German cities.18 In contrast, nearly two thirds of households in the United Kingdom and United States own their homes. New York City, where only roughly a third of households in the city own their home, deviates from this national trend.19

Compared to renters in Germany and the United States, renters in the United Kingdom are much more likely to rent social housing or residential rental accommodations provided at sub-market prices that are targeted and allocated according to specific rules.

Though all nations built social housing after World War II and then disinvested in such housing in the modern era, the United Kingdom has maintained a more robust social housing stock given their larger initial investment. Nearly two thirds of tenants in the United Kingdom rent subsidized social housing. In contrast, almost all renters in the United States and 87% of renters in Germany rent on the private market.20

German renters spend less of their disposable income on housing than their peers in the United Kingdom or United States. As seen in Figure 3, roughly half of low- and middle-income tenants renting on the private market in the United States and United Kingdom spend more than 40% of their disposable income on rent. Low-income renters in the United States and United Kingdom are at least twice as likely to face rent burden than their German counterparts across sectors.21 While housing affordability varies in each nation, all three countries have experienced rising real rent prices and affordable housing supply constraints in the modern era. Demand side housing assistance is a primary policy response to housing affordability issues in all three nations.

Germany generally has more robust tenant protections and stronger enforcement institutions for such measures than the United States and United Kingdom. Germany is the only nation in our comparative analysis with a rent control system that

is mandated by federal law and instituted at the local level, offering tenants protection against exorbitant rent increases. Federal usury laws stipulate that rent increases cannot exceed 20% in three years for any rental unit, and this rate is lowered to 15% in localities with tight rental markets.22 Maximum rents are set for localities through the Mietspiegeln, local rent indexes established using rental prices for all new leases signed in the last six years. This rent control system sets hard limits on how much landlords can increase the rent of their existing tenants. New rental contracts can be negotiated more freely, but rent must not exceed the index price by more than 10%. This system, which slows rent growth while still being rooted in market conditions, is unique among OECD countries.

In contrast, there is no national rent control in the United Kingdom or United States. While the United Kingdom’s substantial social rental market is priced below market rate, there is no rent control on Britain’s private market at the federal or local level. While the United States has no federal rent control, as of September 2022, two states, four counties and

more than 160 municipalities regulate rents within their boundaries.23 Most rent control laws are second generation policies limiting rent increases to a certain percentage, often tied to inflation, or a level set by a government body. Many policies only apply to a subset of dwellings and exempt new construction to limit disincentives to construct new housing. New York City has implemented what is considered one of the strictest rent regulation systems in the United States.24

Germany additionally has more robust eviction protection than the United States and United Kingdom. Most German tenants sign leases with indefinite lengths and have much more flexibility to cancel these contracts than their landlords. Tenants may only be evicted for failure to pay their rent for two consecutive months, subletting the unit without permission, occupation of their unit by the landlord or the planned demolition of the building. Tenants can appeal their eviction if they are likely to become homeless as a result and cannot be evicted if the building is sold.25 In contrast, typical lease terms are much shorter in the United States (one year) and

the United Kingdom (six months), and landlords can generally freely elect not to renew a lease at lease end. Landlords in both nations can also generally evict tenants mid-lease for failure to pay rent or other violations of lease terms.26 Though some cities in the United States have instituted stronger eviction protections, including right to counsel in eviction proceedings and just cause eviction requirements, these policies are uncommon.

Germany and the United Kingdom have national housing quality regulations, whereas the United States does not federally regulate housing quality for all units. In the United States, highly variable regulations are instituted at the state and local levels and on units participating in federally funded housing programs like the Housing Choice Voucher program. Rental units inhabited by voucher-assisted households must meet basic housing quality standards dictated by the federal government. While housing quality regulations are theoretically enforced by local governments across all nations studied, housing researchers, advocates and policymakers from all three countries indicated their governments’

enforcement capacity is generally limited and inconsistent across localities.27

Although tenant advocates and unions exist in each country, German tenant associations help enforce tenant protection laws, while the United States and United Kingdom have no comparable private sector enforcement institutions. Tenant associations play an important role in ensuring rent control, eviction and housing quality regulations are enforced in Germany. These organizations, which tenants must pay dues to join, offer members legal advice and draft legal notices to support tenants in resolving disputes with their landlords.28 Issues these highly professionalized organizations might help members with include rent reduction advocacy or efforts to resolve building maintenance issues. These organizations also provide insurance to cover the litigation costs of members in the event issues cannot be settled through less formal negotiations. There are hundreds of tenant associations operating in various localities in Germany. Dr. Lisa Volmer, a researcher focused on tenant movements, characterized these institutions as an important source of tenant power

given they offer an effective enforcement mechanism for existing tenant protection laws. Several other countries, including the Netherlands, have similar tenant organizations offering legal and advocacy services, but there are no comparable institutions in the United States or United Kingdom.

Each nation designs and implements housing policy at multiple levels of government. While Germany and the United States are federal systems and the United Kingdom is a more fiscally centralized unitary system, in all three nations, the federal government helps fund private market rental assistance, which is then implemented at lower levels of government.29 While the United States and United Kingdom provide most demand-side housing assistance through a single federally funded program, Germany offers housing assistance through multiple social safety net programs with costs shared between the federal and state governments. As described in the introduction, the United States’ Housing Choice Voucher program is the primary tool for subsidizing the housing costs of low-income families. Though all programs seek to promote housing affordability, the scope and implementation of programs vary widely. Spending on direct, demand-side housing allowances as a proportion of GDP is much smaller in the United States than Germany or the United Kingdom. In 2020, the United States spent 0.13% of GDP on meanstested housing transfers while Germany spent 0.7% and the United Kingdom spent 1.4%.30

to lower rent burdens for a large subsection of the population; while the United Kingdom has a large subsidized social housing stock, Germany institutes federal rent control. The United States arguably has no supplementary affordability programs or policies that match the magnitude of these interventions. The excess demand for Housing Choice Vouchers and the burden this puts on families on waitlists might fairly be considered a function of both limited program funding and a failure of the United States to institute more robust housing affordability and tenant protection policies.

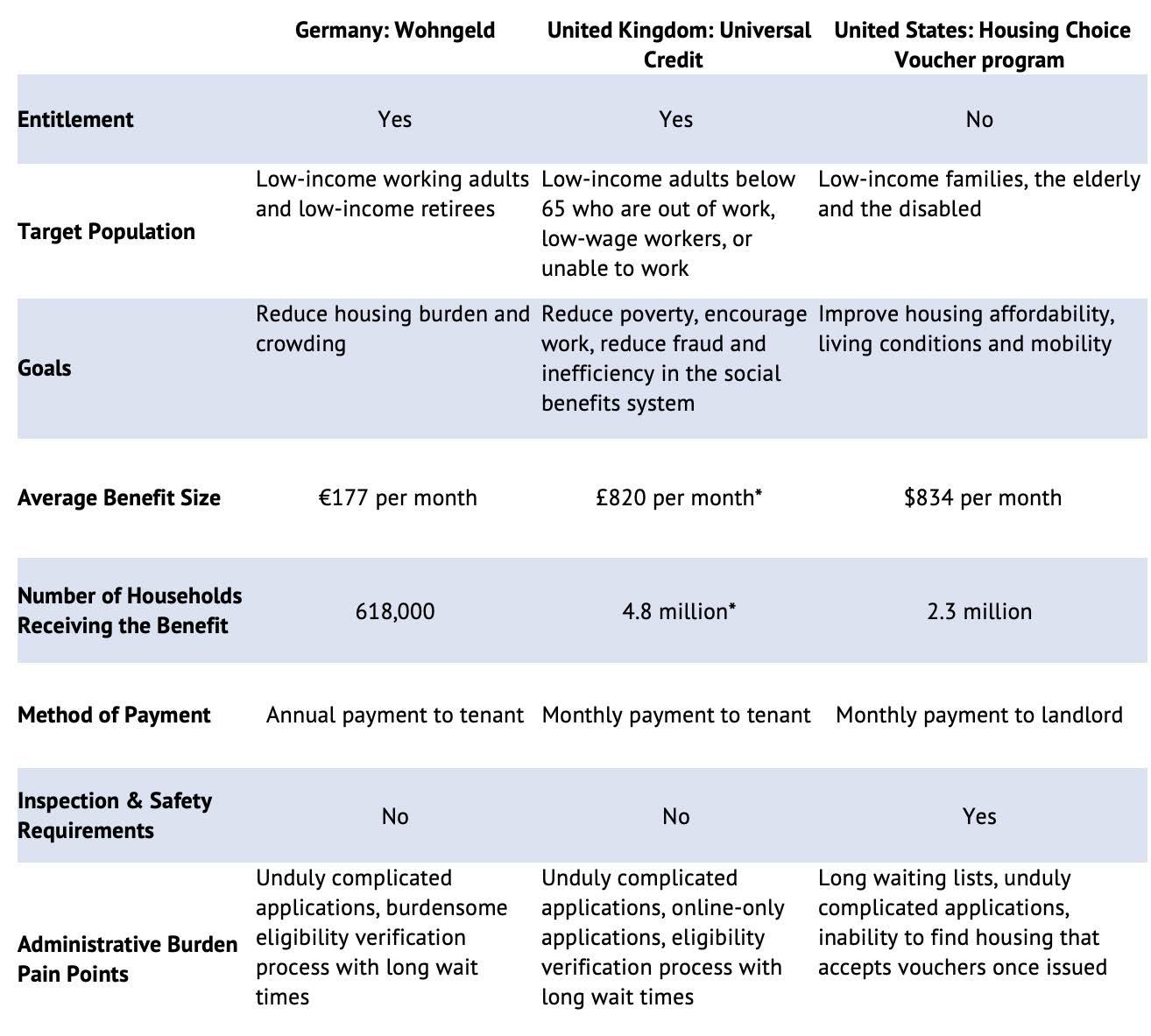

The Housing Choice Voucher program stands apart for the expansiveness of its goals. In seeking to improve housing quality and foster mobility, this program seeks to address the lack of consistent housing quality regulation across localities, racial segregation and the concentration of poverty. While imperfect enforcement of housing quality regulations and inequitable access to opportunity may very well be issues across all nations studied, neither Germany nor the United Kingdom seeks to address these issues through their housing assistance programs. The broad goals of the United States program create program intricacies that burden participating households and other stakeholders in many ways that will be explored throughout this report. The major features of the respective housing allowance programs are summarized in Table 2.

The broader housing policy of each nation shapes the participant experience, design and goals of their respective housing assistance programs. Germany and the United Kingdom both have other major federal housing affordability initiatives in place

In Germany, housing assistance payments are available to renters of private housing, renters of social housing and homeowners. In 2022, more than 8% of the population claimed social benefits that include housing assistance administered through a standalone housing subsidy (Wohngeld), the unemployment insurance system, the general welfare system and the social housing system.31 More than

618,000 people received Wohngeld benefits in 2022.32

Roughly 5.4 million Germans received social or unemployment benefits in 2022, which often include rent support.33 There are also 1.1 million subsidized social housing units dispersed to low-income German households using a voucher system as of 2020.34 Through this system, households that might otherwise face housing market discrimination are pre-approved for units and matched to social housing

based on their needs.35

Wohngeld is the only standalone housing benefit available to private market renters, and thus is most comparable to the Housing Choice Voucher program. The goals of Wohngeld are to help lowincome Germans reduce their housing cost burden and prevent overcrowding.36 This benefit primarily serves low-income working adults and retirees.

*Includes social benefits other than housing assistance

Individuals who are very low income, out of work or are unable to work typically do not receive Wohngeld, and are instead supported through unemployment and other more comprehensive social benefits systems. Wohngeld benefit levels are based on region of residence, household size, household income and amount of rent or homeownership costs; the average benefit size is 177 euros per month.37 Program participants receive their benefits through annual direct cash payments. While Wohngeld seeks to lower the housing cost burden of participants, unlike the Housing Choice Voucher program, there is no consistent limit to the proportion of income participants spend on housing in the determination of benefit size. There are also no housing quality rules or inspections directly tied to program implementation.

Though an entitlement, only 40-50% of Wohngeld eligible households participated in 2007.38 Low take-up rates may be driven by the administratively burdensome nature of the program or the relatively low benefit levels some program participants receive. Interviews with German policymakers and service providers indicated the Wohngeld application form is unduly complicated and the eligibility process conducted through mail is arduous. As of fall 2022, a significant expansion of Wohngeld is being negotiated in the German Bundestag. This expansion may both significantly increase rent subsidies and triple the households entitled to benefits.

The housing allowance program in the United Kingdom is currently undergoing major structural changes. Prior to 2013, the government operated a standalone housing allowance program known as Housing Benefit, which was designed to ensure that renters had an income that was no less than the social assistance benefit rate after paying rent.39 Landlords

were paid directly under this system, mirroring the Housing Choice Voucher program. In 2012, the coalition government introduced the Universal Credit program to replace six existing social assistance benefits for working-aged people, including the Housing Benefit and income and child support tax credits. This single benefit program was intended to simplify and streamline social assistance provision, encourage work and reduce fraud in the system.40 Initially, Universal Credit was set to be rolled out beginning in 2013, but administrative issues required the implementation date to be pushed back multiple times. Ultimately, full implementation of Universal Credit is now set to be completed in 2023. After that point, the Housing Benefit will not be available as a stand-alone program.

The Universal Credit system is now the primary source of housing affordability support in the United Kingdom. The goals of this program are to reduce poverty, encourage work and reduce fraud and inefficiency in the social benefits system.41 The program’s target population is low-income residents of the United Kingdom age 18 or over but younger than the state pension age. Participants below an income threshold will receive a maximum benefit based on household size (assuming unit size restrictions are met) which, depending on actual rent, may cover all or part of their housing expenses. The benefit amount is calculated based on family size and additional cash support is available for food, childcare and other basic needs. Total benefits decrease with increasing earned income.42 The average benefit size was £820 per month in August 2022.43 The transition to Universal Credit has led certain groups to receive less generous overall benefits than they received previously under the host of social safety net programs offered.44 Program participants receive their benefits through direct monthly cash payments, a change compared to the legacy Housing Benefit. Like Wohngeld, there are no housing quality rules or inspections embedded in the program.

Our comparative analysis is divided into subsections, which mirror the three stages that Housing Choice Voucher program participants go through to utilize their vouchers, each of which has elements of administrative burden. First, a household faces substantial learning and compliance costs when learning about and applying to the Housing Choice Voucher program. Second, once a household is issued a housing choice voucher, it faces the psychological cost of having just 60 days at a minimum to find and secure a rental unit. Three factors shape a voucherassisted households’ ability to find a unit: (1) the voucher amount; (2) the availability of units in neighborhoods that meet households’ needs; and (3) the availability of units owned by landlords willing to participate in the Housing Choice Voucher program. Third, once a household has found a unit, landlords and households face learning, compliance and psychological costs in the inspection process. Finally, households face an additional psychological cost in that the payment goes to the landlord, not through them.

The most important eligibility requirement for Germany’s Wohngeld, the United Kingdom’s Universal Credit and the United States’ Housing Choice Voucher program is income. Each program targets low-income populations and provides benefit amounts that phase out as earnings rise. However, in all three settings, applicants face an administratively burdensome process for determining their eligibility,

completing applications, providing documentation to verify their eligibility and maintaining assistance over multiple years. Thus, evidence from two pandemicera housing programs in the United States, the Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) program and the Emergency Housing Voucher (EHV) program, are also considered as case studies of implemented policy innovations that have reduced administrative burden in rental assistance programs. This section recommends streamlined applications and documentation flexibility — as well as universality and expanded eligibility — to address the burdens associated with proving one’s eligibility for the program.

Wohngeld in Germany and Universal Credit in the United Kingdom are means-tested entitlement programs where any household that meets the eligibility requirements receives a housing benefit. In contrast, the Housing Choice Voucher program in the United States is means tested but not an entitlement program, which means many eligible Americans do not receive vouchers. A main finding from the comparative analysis below is that the application processes for Wohngeld and Universal Credit are administratively burdensome, involving substantial learning and compliance costs.

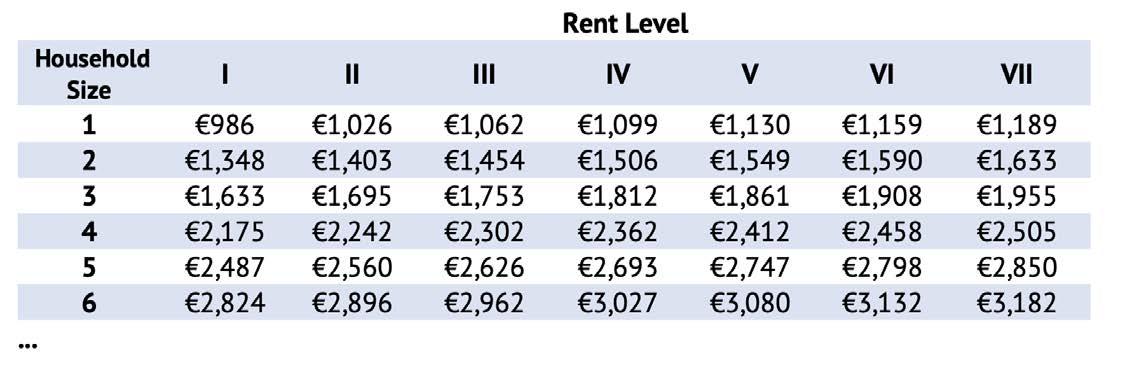

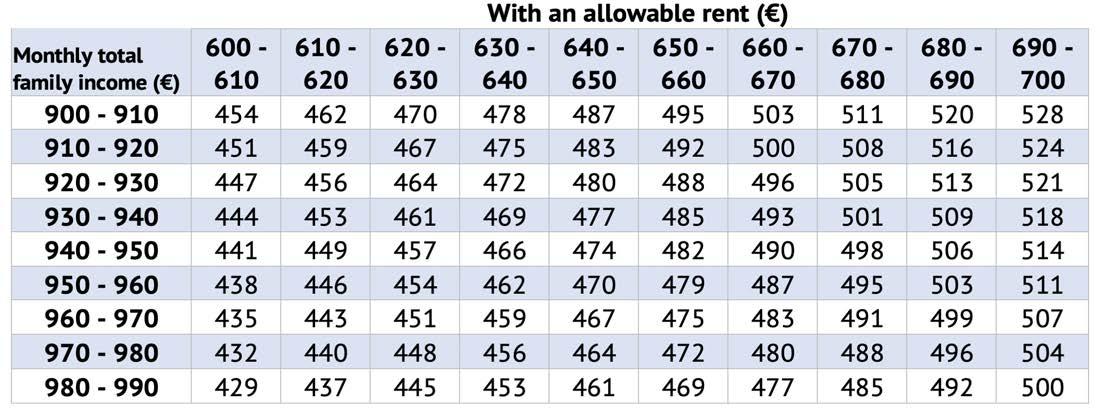

Germany’s Wohngeld program has a complicated income eligibility scheme, with monthly income ceilings that are specified based on the applicant’s

household size and rent level (Mietstufe). Rent levels are set for each municipality by comparing rental prices in that region to rents across Germany. The levels range from I to VII, with average rents being lowest in rental level I and highest in rental level VII. For example, Berlin is classified as rental level IV whereas Munich is classified as rental level VII, reflecting lower average rental costs in Berlin than Munich (€879 vs. €1,125 for a one-bedroom apartment).45 Income eligibility for Wohngeld depends on the rent level to reflect differential housing costs across municipalities. Household monthly income is determined after accounting for allowable income deductions for each earner in the household. Deductions range from 10-30% and are based on income tax payments and/or compulsory contributions to pensions or health insurance.46 The end result is the complicated scheme pictured in Table 3.

In addition to the income ceilings, Wohngeld has income floors. Wohngeld cannot be combined with other social assistance programs, such as unemployment benefits. Because of that, the program has minimum income requirements to ensure that it targets the working poor and middle-income

Germans, not the neediest subset of the population who have their housing costs covered by other forms of social assistance. As of 2022, the monthly minimum income requirement for Wohngeld is €449 (for all rent levels) plus the applicant’s rental costs (including utilities). In other words, the applicant must be earning at least €449 per month in afterhousing income to qualify to receive the housing allowance.47

For Germany’s Wohngeld program, the primary obstacle to using the housing benefit is navigating the detailed eligibility requirements. Field research interviews emphasized that Wohngeld eligibility is a “black box.” Many low-income Germans do not know whether they qualify for the program, resulting in wasted effort for ineligible applicants and financial harm for those who did not apply but would have qualified. In addition, some eligible Germans who know they qualify for the program choose not to apply because the benefit amount they would receive is nominally small due to the gradual tapering off of the program (which is described in more detail later in this report), and not worth the administrative effort.

Even after a Wohngeld applicant determines that they are eligible to apply for the housing allowance, there are additional obstacles to verify their eligibility, such as projecting their future income. To demonstrate that their income is below the ceilings given in Table 3, applicants must project their annual income. If their actual earned income, as reported in their tax records, differs from their projections, Wohngeld recipients are responsible for paying back the excess benefit they received. Since Wohngeld is paid annually as a cash transfer, recipients may have spent their allowance and no longer have those funds available to repay. This retrospective income reassessment, which results in benefit repayment and uncertainty about whether to save, is a deterrent to program participation.

Further, Wohngeld applicants apply directly through their local housing benefit office and all communication is by mail. Applicants need to provide the following documentation for each member of the household when applying for Wohngeld: identification with confirmation of registration, rental agreements which show monthly rents, current proof of rental payments (from bank statements or receipts), proof of last change in rent, utility bills and proof of income (salary certificate or pension notice).48 To successfully complete these applications, applicants often enlist the help of nonprofit social service organizations, like religious charities. Interviewees claimed that the government does not help applicants with the process because even answering minimal questions can be perceived as a conflict of interest. Because applications are submitted through the mail, applicants can sometimes wait months before learning whether they submitted the correct supporting documentation and whether their application was successful, delaying the receipt of needed benefits for low-income rental households.

Although an entitlement, the Universal Credit system in the United Kingdom places burdens on recipients through its goal to incentivize work. In general, anyone living in the United Kingdom between the age of 18 and 66 (the state pension age) with less than £16,000 in money, savings, or investments is eligible to receive Universal Credit. Anyone who meets these initial eligibility requirements is entitled to receive Universal Credit, but the benefit amounts gradually phase out as income rises. For example, a person with low savings but a high income would qualify for Universal Credit but receive a monthly benefit amount of £0. Households have a maximum amount of weekly income that they can receive before income begins to affect the housing portion of Universal Credit. An explicit goal of Universal Credit is to incentivize work, so claimants are also subject to certain job search requirements depending on their income level, care responsibilities and disability status. These requirements include actively searching for work, participating in work preparation activities and attending periodic interviews to discuss plans to return to work. When applying to Universal Credit, beneficiaries who are temporarily unemployed need to demonstrate that they intend to satisfy the program’s work requirements. As a first step to fulfilling those conditions, applicants are required to schedule a preliminary interview at their local Jobcentre with their assigned work coach. Applicants are expected to meet regularly with their work coach during the duration of the time they receive benefits to ensure they are completing their assigned jobsearch activities. The interview can be conducted in person or via the phone, but if applicants do not schedule the initial interview within a week of completing their Universal Credit application, they may be required to restart the application process.

Many of the obstacles facing Universal Credit

applicants are the same as those faced by Wohngeld applicants. For example, determining eligibility can be challenging as the main government website for Universal Credit simply directs applicants to “contact their local council” to apply for the program or to report a change in circumstances. Additionally, Universal Credit recipients are required to apply for the program online, with no exceptions made for those with limited or no internet access, or other barriers. During the online application process, prospective Universal Credit recipients need to provide the following documentation: their landlord’s contact details; their bank, building society, credit union or Post Office card account details; the amount they earn from work (such as recent pay slips); and receipts documenting any income that’s not from work (for example a pension or insurance plan).49 In general, individuals who receive Wohngeld, Universal Credit or a Housing Choice Voucher are responsible for recertifying their eligibility for the program annually. This means that, in all three programs, households need to provide income documentation and will have their benefit amounts adjusted according to their updated income. In extreme cases, program beneficiaries can suddenly lose all benefits as their circumstances change from year to year. In addition to the annual recertification process, Universal Credit recipients in the United Kingdom are under strict requirements to report any “change of circumstance” at the time it occurs. Changes in circumstances can affect how much recipients receive for the entire annual assessment period, not just from the date they are reported onward. Recipients who do not report a change of circumstance can be taken to court or face a financial penalty. Changes of circumstance include finding or finishing a job, having a child, moving in with a partner, starting to care for a child or disabled person, changing mobile number or email address, moving to a new physical address, changing bank

details, changing rental amounts, changes to health, becoming too ill to work or to meet with the work coach, changing earnings, changing savings amounts and changing immigration status (for noncitizens).50

In Germany and the United Kingdom, determining and verifying eligibility to receive a housing allowance is burdensome for prospective applicants. That burden falls disproportionately on traditionally marginalized groups such as very low-income individuals and non-native language speakers. Given the limitations of drawing policy recommendations from international contexts to ease eligibility verification requirements, early evidence from pandemic-era rental assistance programs in the United States may instead be used as a case study to consider how to reduce administrative burden in the Housing Choice Voucher program eligibility process.

In the United States, applying to receive a housing choice voucher is similarly burdensome. Prospective voucher recipients apply for the program through their local PHA who maintain some discretion over the exact application criteria and documentation required to apply for vouchers. All PHAs require some form of income documentation for every adult in the household (which is then verified with a third party) and citizenship documentation for every member of the household. In addition, applicants may be subject to criminal background and credit checks to ensure they comply with the rules surrounding previous felony or drug convictions and rental history. In many cases, PHAs applications are over 30 pages long, requiring duplicate or superfluous information from already time-burdened applicants.

Because PHAs maintain some discretion over

their application process, they can streamline the requirements to reduce administrative burden. HUD can assist with this process by publishing simplified sample applications which can serve as templates for PHAs. This process has already been piloted with the EHV and ERA programs, which were federally funded programs that provided emergency rental assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. To ensure that the application process did not place an undue burden on those already at risk of experiencing homelessness or eviction, HUD published a simplified application for PHAs to use as a template for administering the EHV program.51 The template application was less than four pages long and required applicants to produce information and documentation satisfying only the most basic eligibility criteria: household composition information, income information and documentation and citizenship status information.

Even without using templates designed by the federal government, PHAs can take independent action to simplify and streamline the applications they use for housing vouchers, centering applicants in the design process. For example, in 2018 Washington, D.C. hosted its first “Form-a-palooza” which brought residents, government employees and experts in usercentered design together for a day-long workshop.52 The workshop helped governments identify residents’ pain points with applications for government services and developed solutions to those problems. Similar workshops, designed to explicitly consider applications for housing choice vouchers, could help PHAs streamline their application processes to reduce administrative burden.

Recommendation: PHAs should streamline the application process for vouchers to ensure applicants do not need to provide duplicative or unnecessary information. HUD should publish streamlined application templates.

Flexibility in both the EHV and ERA programs helped reduce administrative burden in the application processes. First, for the EHV program, HUD waived the third-party income verification requirement prior to issuing the voucher, allowing applicants to instead submit an affidavit attesting to their reported income and asset amounts. After receiving that affidavit, PHAs issued the emergency voucher and applicants were given an additional 60 days to provide third-party verification. It is worth noting that HUD required PHAs to take punitive action, including the potential revocation of the voucher, if families made mistakes in their self-attestation or failed to provide the verification within the timeframe; any future use of self-attestation as a tool should avoid measures that become punitive towards families. Second, for the ERA program, the Treasury Department allowed flexibility in the documentation required to verify program eligibility in order to decrease administrative burden and increase take-up. The following are examples of how ERA programs increased documentation flexibility:53

‣ Self-attestation. Treasury explicitly allowed programs to use self-attestation of income, housing instability, amount of back rent owed and demonstration of COVID-related hardships. In a 2021 survey, over 80% (N=99) of program administrators surveyed accepted an applicant’s self-attestation of income.

‣ Fact-based proxies. 29% of respondents reported using fact proxies like the median income for an applicant’s census tract to infer households’ incomes.

‣ Categorical eligibility. Over 70% of program administrators reported using applicants’ eligibility in other income-verified programs to document their income.

‣ Accept more kinds of documentation in more formats. For example, an applicant

could use a text message that a gig had been canceled as proof of COVID-19 income related loss. In some programs, applicants could use photos of eligibility documents rather than scans, or electronic rather than wet signatures.

Data on the ERA program suggest that these changes reduce the time it takes to issue relief to renters and landlords without leading to a significant increase in fraud. There is evidence that the flexibility in these programs enabled them to get relief to renters quickly. Among eight states’ ERA programs, the two states that offered the least burdensome applications — Illinois and Virginia — had the highest disbursement rates.54 Also, evidence suggests these programs had little fraud. For example, evidence from Maine, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Texas reported little to no fraud in their administration of the ERA program.55 A similar process where HUD allowed selfattestation initially and gave applicants additional time to provide third-party income verification would ensure vouchers are distributed quickly and efficiently through the Housing Choice Voucher program.

Recommendation: HUD should enable PHAs to issue vouchers prior to receiving third-party verification of eligibility information. HUD can enable PHAs to use self-attestation, fact-based proxies or categorical eligibility to screen for initial eligibility.

One aspect of housing allowance administrative burden that is unique to the U.S. context is the “time tax” of families remaining on waiting lists. Wohngeld and Universal Credit are entitlement programs, which means that anyone who meets the

eligibility requirements receives rental assistance from the government. Conversely, The Housing Choice Voucher program in the United States provides assistance to approximately 2.3 million households, representing only one-fourth of the eligible households.56 According to a recent analysis by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), families that eventually received vouchers spent, on average, two and a half years on wait lists, exposing many to homelessness, overcrowding, eviction and other hardships.57 That average wait period understates the true demand for the program because many families never rise to the top of the waitlist and many others live in jurisdictions where PHAs have closed their waitlists entirely.

Academics, advocates, policymakers, politicians and think tanks have convincingly argued that a universal Housing Choice Voucher program – in which all households eligible for the program receive a voucher to subsidize their rent on the private market – is a necessary tool to improve the functioning of the program and address the United States’ housing affordability crisis. The Housing Initiative at Penn estimates that universal expansion of the program, in which every household with an income at or below 30% of the area median income received a voucher, would grant eligibility to 10.4 million renter households.58 This program expansion would have the potential to lift 3.9 million households out of poverty, of which 59% would be households of color.

At an average voucher payment size of $834 per month or $10,008 per year, expanding the voucher program to cover all eligible households would cost an estimated $81 billion dollars. Although costly, this level of federal investment in housing assistance is not unprecedented. For comparison, the mortgage interest deduction cost over $66 billion in 2017 prior to reforms and $30 billion in 2020. This deduction

primarily benefits high-income households, with 62% of claimants in 2020 earning over $200,000 per year.59 A universal housing voucher program would be significantly more progressive than spending on existing federal programs that accrue benefits primarily to the highest income quintiles.

Recommendation: Congress should expand the Housing Choice Voucher program to make it a means-tested entitlement program in which every household with an income at or below 30% of the area median income receives a voucher.

In addition to the capacity constraints in the Housing Choice Voucher program, two broad groups are prohibited from receiving housing choice vouchers regardless of their income eligibility: undocumented immigrants and those with past disqualifying criminal activity. Germany and the United Kingdom have similar rules prohibiting noncitizens from using their housing allowance programs. In Germany, to qualify for Wohngeld, applicants must be a German citizen or have a valid German residence permit. In the United Kingdom, only residents with one of the following immigration statuses are allowed to claim Universal Credit: United Kingdom or Republic of Ireland citizenship, settled status from the European Union (EU) Settlement Scheme, indefinite leave, refugee status or humanitarian protection or right of abode.60 All other citizenship statuses are not eligible to claim Universal Credit.

status create administrative burden for applicants to the Housing Choice Voucher program by creating uncertainty about eligibility and benefit amounts, especially for households with mixed immigration status. These rules were first specified in Section 214 of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1980 and would require Congressional action to change.61 However, cities and states can expand upon the federal housing voucher program by issuing additional vouchers that are funded with their own revenue streams and, thus, not subject to federal guidelines such as immigration documentation. In that case, those additional vouchers can cover federally excluded groups, such as undocumented immigrants. For example, this year legislators in the New York State Senate and Assembly proposed a Housing Access Voucher Program (HAVP) which would create a state-funded rent voucher for New Yorkers experiencing or at-risk of homelessness, including immigrants without legal status.62

Recommendation: Congress should expand eligibility for housing choice vouchers to all U.S. residents including immigrants without legal status, especially if the program were made universal.

In the United States, most noncitizens with permanent legal status are eligible to receive housing vouchers, but temporary and undocumented immigrants are not. Families with at least one person who has an immigration status that makes them ineligible to receive a voucher can receive prorated assistance based on the number of family members that are eligible. Exclusions based on immigration

In addition to the categorical exclusions based on immigration status, federal law in the United States permanently ban any household with a member who has ever been required to register as a sex offender or ever been convicted for manufacturing methamphetamine on federally assisted property from receiving housing vouchers. Additionally, households with a member who was evicted from federally assisted housing for criminal drug activity receives a temporary admission ban of at least three years. PHAs have discretion to admit the household if the member successfully completed a drug rehabilitation program and have discretion to prohibit admission for longer than the three-year

standard.63 PHAs are required to conduct criminal background checks as part of the application process for housing choice voucher. However, HUD’s guidance on screening tenants gives PHAs broad discretion over the “look back” period and the categories of criminal activity to prohibit (over and above the federally mandated prohibitions described above). In April 2022, HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge issued a memo directing staff to review its programs and propose regulatory changes that would reduce barriers to entry for HUD-assisted housing for those with criminal justice system involvement.64

Germany and the United Kingdom do not have similar rules prohibiting people with criminal histories from accessing housing benefits. In the United Kingdom, citizens are excluded from Universal Credit only while serving a prison sentence or being held in pre-trial detention and are immediately eligible to begin or resume receiving benefits upon their release.

Exclusions based on prior criminal records create administrative burden for prospective applicants and current voucher holders by creating uncertainty about their eligibility status, especially because local PHAs have broad discretion over the look back periods for considering criminal offenses, as well as the ability to include additional categories of criminal activity or arrests in their background check. In addition to the uncertainty they create, these exclusions impose a psychological administrative burden for current voucher holders who fear that their vouchers would be revoked if a member of their household is accused of a potentially disqualifying offense.

Recommendation: Congress should eliminate categorical exclusions for those with criminal convictions, especially if the voucher program became universal. In advance of that change, HUD should update its guidance to PHAs on criminal background screening, limiting

their ability to reject applications from those with criminal justice involvement, beyond the minimum requirements mandated by current law.

For housing allowance programs in the United States and elsewhere, the size of the benefit directly impacts the amount of rent that families pay from their own earned income (i.e., rent burden) and what units are available to them. This section finds that, comparatively, the subsidy calculation under the Housing Choice Voucher program yields greater neighborhood choice, a goal unique to the United States program. However, the system could be improved if a family’s payment standard did not vary by unit size and benefit proration for household members without eligible immigration status was clearer and less punitive.

The calculations undergirding the subsidies paid through the Housing Choice Voucher program, Wohngeld in Germany and the housing element of Universal Credit in the United Kingdom each consider similar factors like family income, gross rent and market characteristics. However, the details of the calculations reflect key differences across the programs’ objectives, implied values and theories of impact, generating substantially different results on the affordability and availability of units to beneficiaries. The details of the Housing Choice Voucher subsidy calculation are described in Box 1.

In each country, the relative need of the target populations is a key determinant of housing subsidy calculations. Due to the lack of other social supports and shortage of vouchers in the United States, PHAs often prioritize very low-income families

that are currently unhoused (in the shelter system) and subsidies are therefore much larger. German allowances are much smaller, but they target a less high-need portion of the population, as there are separate robust social assistance programs available for those with no or very low incomes. Similarly, rental support in the United Kingdom is also an entitlement situated within a larger system of social supports with a broader base.

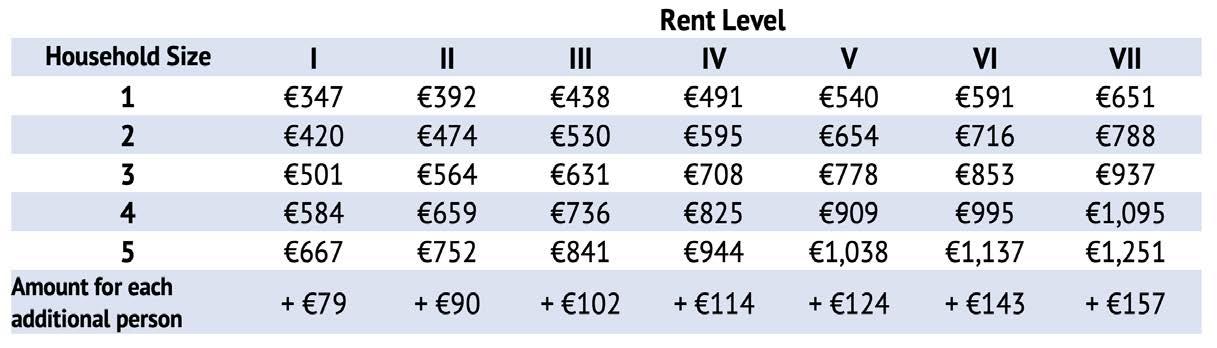

Like the Housing Choice Voucher program, Germany’s Wohngeld system offsets rental costs for low-income households to prevent them from being overly cost burdened by housing expenses. The amount of rent subject to subsidization, “allowable rent,” is the lesser of a program defined rent ceiling and the total rent. The rent ceiling is a concept comparable to Fair Market Rents (FMRs) in the United States. As described in the prior section, German municipalities are classified across seven rental levels (Mietstufen). In addition to income eligibility, each rental level specifies allowable rent ceilings which vary by unit size (Table 4).

Like in the United States, the size of the subsidy relative to the rent ceiling depends on income. For a given family renting a given unit, increases in household income lower Wohngeld benefit and

increase the family’s payment responsibility, with the benefit tapering off until the income ceiling is reached. This gradual reduction incentivizes people to work and earn more, as they still see after-housing income increases.

A household’s actual total housing costs also inform the size of their Wohngeld subsidy, but the relationship is different than in the United States. Wohngeld benefit never covers the entire difference between two differently priced dwellings. In the Housing Choice Voucher program, as rent increases, housing assistance payment (HAP) increases dollar for dollar and total tenant payment (TTP) stays constant until rent exceeds the payment standard. Under Wohngeld, the benefit always increases by a percentage of each increase in allowable rent. Thus, German beneficiaries see increases in after-housing income if they rent smaller and less expensive units, whereas housing choice voucher holders typically do not.

While Wohngeld’s calculation limits neighborhood choice and incentivizes low-cost housing, there are no actual restrictions on what types of units Wohngeld recipients can occupy. As long as beneficiaries meet income requirements, they will receive a Wohngeld benefit based on their allowable

rent. Within the Housing Choice Voucher program, voucher-assisted households cannot rent dwellings that are overcrowded or require tenants to contribute more than 40% of their income on rent.

Choice Voucher program. Low-income Wohngeld beneficiaries may still spend up to 50% of their income on housing even if renting at or below the rent ceiling.66

Although Wohngeld does not prevent recipients from renting high- and low-cost units, it is paternalistic in that it encourages renters to select lower cost units to avoid “overconsumption” of housing. In the Housing Choice Voucher calculation, participants are theoretically empowered to choose housing that best meets their needs regardless of cost. However, the Housing Choice Voucher calculation is also paternalistic on the margins, prohibiting beneficiaries from renting “low quality” units or units that require high relative tenant contributions.

In general, Wohngeld recipients spend a lower proportion of their income on housing than do U.S. voucher holders. The Housing Choice Voucher program is designed so that rent burdens are between 30-40% of income, whereas the average rent burden for Wohngeld recipients is 27%.65 However, there is more variability in Germany. Because of the tapering of Wohngeld payments in accordance with rent and income, the impact of Wohngeld on housing cost burden is less uniform than the Housing

The Wohngeld system is incredibly difficult to understand and predict, even for those well-versed in housing policy and bureaucratic language. The benefit scheme is based on nuanced economic assumptions about marginal incentives to work and consume housing. The resulting system is a series of economist-derived tables. (See Table 5 for an excerpt of the benefit table for a household of four.)

Wohngeld benefit is identified in the table based on the household’s monthly income and allowable rent, with maximums for these parameters varying by the metropolitan area’s rental level. To the recipient, Wohngeld payments are unpredictable and confusing, presenting a real disutility for beneficiaries managing their household budgets. Compared to Germany’s Wohngeld, voucher holders in the United States have a clearer sense of their defined contribution for rent and subsidy amount.

Although the transition from Housing Benefit to Universal Credit is still ongoing, the subsidy

The Housing Choice Voucher benefit amount is calculated at two phases in the search process: at voucher issuance and when a unit is secured. When issued a voucher, a family is given information about the payment standard, which is an approximation of typical rent for a quality unit based on their household size and rental location. The maximum subsidy amount is estimated as the payment standard minus a family’s required contribution, known as total tenant payment (TTP). TTP is generally 30% of monthly income, a level which ensures families are not overly burdened by housing.

After a unit is secured, the actual subsidy, known as the Housing Assistawnce Payment (HAP) is calculated. HAP is the lesser of the maximum subsidy and actual rent minus TTP. When rental costs are at or below the payment standard, the family contribution is always TTP and does not change with rental costs. Families then pay 100% of the rental costs that exceed the payment standard, up to a maximum family contribution of 40% of monthly income.

PHAs are required to set payment standards based on Fair Market Rents (FMRs). FMRs are an index of typical rents in an area, which HUD updates annually. Data comes from the Census and Community Population Survey, but PHAs have the option to appeal federally calculated FMRs using evidence from their own rigorously conducted surveys. In general, payment standards must fall within a “basic range” of 90-110% of the 40th percentile FMR, but PHAs can apply for exceptions to set higher or lower payment standards. Payment standards must be reviewed and updated within 90 days of the publication of new FMRs.

The rational for this methodology, where family contribution does not change with rent (up to the payment standard), is to provide families with enhanced flexibility and choice in choosing their unit. In theory, voucher holders can rent homes that best meet their needs, without incentivizing families to rent in more or less expensive units due to family contribution requirements that fluctuate between units, neighborhoods or metropolitan areas.

calculation is similar for both programs. Beneficiaries below a certain income threshold receive an allowance that is intended to cover their full housing cost. However, this presumed total housing cost is lower in the United Kingdom than in the United States. In the United Kingdom, maximum subsidies, known as local housing allowances, are set at the 30th percentile of market rents for units of a given size (as measured by number of bedrooms). The rates have been adjusted over time in response to a desire to limit the social safety net, especially for large families.67

As in the United States, the composition of a household determines the unit size an applicant is entitled to, but the United Kingdom allocates fewer bedrooms per person than in the United States. Couples in households are expected to share bedrooms, as are any two children under the age of 10 and any two children of the same gender under the age of 16. The maximum number of bedrooms is four. Most recipients under the age of 35 (in the absence of dependent children) are allocated to a “Shared Accommodation” rate and are expected to share units with other renters. By comparison, PHAs

in the United States have the flexibility to set their own frameworks for translating household size to unit size as long as the household does not have more than two people per bedroom. In New York City, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development allocates one bedroom is allocated per child.

In the United Kingdom, there is a maximum amount of weekly income that households can earn before income begins to affect their housing benefit and other entitlements. This limit, known as the “applicable amount,” varies by age, number of dependent children and ability to work. If weekly income is at or below the applicable amount, the full amount of housing support is received. For each dollar of income greater than the applicable amount, housing benefit decreases by 55%. This framework, which is similar to that of the United States and Germany, reduces program cost while also incentivizing work. However, a dollar of income above the allowable amount increases the tenant responsibility by 55%, rather than 30% as it does under the Housing Choice Voucher program.

After the above benefit is calculated, households may still be subject to some benefit deductions. If the household includes non-dependent adults, like grown children or the elderly, as well as undocumented immigrants, the benefit will be reduced. Additionally, if a household rents a unit with more bedrooms than allotted based on household composition, the benefit will be decreased further (below the initial local housing allowance for the smaller unit size) to discourage overconsumption of housing. Large families and households with elderly people or undocumented immigrants are also particularly burdened by these penalties, as they are either overcrowded in a small unit or penalized for an appropriately sized one.

Considered together, the benefit calculation in the United Kingdom does not reduce administrative burden for families. The value of the housing benefit has increasingly failed to expand housing affordability. One consequence of this lack of affordability is overcrowding. Research has shown that the 2011 and subsequent reforms increased overcrowding by 5% (75,000 households).68 Singleparent households, households with a disabled person and racially marginalized families are disproportionately impacted by overcrowding.

Until recently, Fair Market Rents (FMRs) were calculated and payment standards were set at the metropolitan level. However, in 2018, HUD introduced small area fair market rents (SAFMRs) which promote neighborhood choice in metropolitan areas where cost of living varies substantially by zip code. Compared to metropolitan area FMRs, SAFMRs yield higher payment standards in higher rent zip codes and lower payment standards in lower rent zip codes. Along with the introduction of SAFMRs, HUD also established that there will not be more than a 10% decline in FMRs or SAFMRs from one year to the next. This helps protect against volatility, especially in low-income neighborhoods that are transitioning from metropolitan FMRs to SAFMRs, where decreases in the FMR and payment standard will result in an increased family contribution.

Empirical analysis of the impact of SAFMRs indicates that the reform has been effective at increasing the number of affordable units available in high-opportunity neighborhoods, while lowering the availability of units in low-opportunity neighborhoods. Studies show that, though SAFMRs do not impact the rate at which families moved, those families who did move were more likely

to move to higher opportunity neighborhoods, with a 6.7 percentage point increase of movers to neighborhoods that rank at least one decile higher on a ZIP code opportunity index.69 Figure 4 shows that the shift to SAFMRs increased the number of rental units in high-rent neighborhoods that were affordable to voucher holder families (or renting under the applicable FMR cap) in the seven SAFMR PHAs.

The process for establishing metropolitan FMRs and SAFMRs in the United States is preferable to comparable processes for setting benefit amounts in Germany and the United Kingdom. The data that informs FMRs in the United States is more robust and comprehensive, representing housing costs for all rents based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau. This is similar to the data used to set local housing allowances in the United Kingdom, but payment standards in the United States are set higher (up to 110% of the 40th percentile FMR without exceptions) compared to 30th percentile rents in the United

Kingdom. Further, the United Kingdom does not uprate consistently nor does it account for variation within metropolitan areas.

Germany’s system is the least robust. Geography is less specific, with seven rental levels spanning many different areas in different parts of the country. Instead of each municipality (or zip code) having its own rental levels, localities are grouped into a rental level based on how their rents compare to the national average, with each rental level encompassing a range of actual rents. For example, Berlin is in Mietstufe IV, along with other localities that have rents 5-15% above the national average.70 Compared to SAFMRs, this framework does not promote neighborhood mobility or efficiently allocate resources as the level of assistance is not as sensitive to geographic changes in housing costs. However, the German program does not have a stated (or implied) goal of enhancing mobility and neighborhood choice.

Beyond geographical considerations, the process for establishing FMRs and Mietstufen differ in other

Notes: FMR = Fair Market Rent. SAFMR = Small Area Fair Market Rent. High-rent ZIP Codes are those in which the median rent is at least 10% higher than the metro area median (that is, the ZIP Code rent ratio is greater than 110%). In medium-rent ZIP Codes, the rent ratio is between 90% and 110%, while in low-rent ZIP Codes, the rent ratio is less than 90%.

fundamental ways. Mietstufen are calculated based on the 50th percentile of the last two years of rental data for Wohngeld recipients, not rents paid by all renters. Thus, by design, rent ceilings are lower than rents paid by half of program beneficiaries and substantially lower than market rates. Because renters will receive no subsidy against the housing costs that exceed allowable rent, they are incentivized to seek less expensive housing.

Compared to the restrictive system in the United Kingdom, the German system for calculating the allowance amount based on household size is less administratively burdensome. While Germany subsidy amounts are lower, they are only based on household size, not unit size. Interviewees agreed that this was a beneficial part of the program, both due to increased flexibility and less need for administrative oversight. The United Kingdom is notably even more restrictive in this regard, mandating single adults to the Shared Accommodation rate, doubling up all children and reducing the benefit if families rent units that are larger than initially scoped for.

While the Housing Choice Voucher program does not penalize “overconsumption,” it does not allow families to make their own tradeoffs about number of bedrooms versus other unit and neighborhood characteristics. Currently, HUD publishes FMRs (including SAFMRs) for each unit size, as measured by number of bedrooms. It is then the responsibility of local PHAs to translate FMRs into payment standards for each bedroom size category. As mentioned previously, PHAs also have the flexibility to determine how household composition informs the size of a unit on a family’s voucher. Regardless of the PHA’s policy, HUD mandates that if a family selects a unit that has less bedrooms than the amount on the initial voucher, the payment standard will be lowered

to match that of the smaller unit.

Within the confines of the current system, New York City’s allocation of one bedroom per non-partnered household member (including children) is quite generous compared to policies in other PHAs and international programs. This allows families to choose between the larger units or smaller ones. However, the federal requirement to lower the payment standard if a family rents a smaller unit ultimately constrains choice and, in turn, mobility. Down-rating of the payment standard is paternalistic in that a dwelling’s quality is judged solely based on number of bedrooms, without accounting for other characteristics that may make the unit desirable to all or some families. Indeed, number of bedrooms is a good proxy for quality that HUD and PHA can use to set FMRs and payment standards. However, an individual family should be able to select units within those quality parameters (as measured by cost) based on their own specific needs. For example, families might prefer that children share bedrooms, or families could value other characteristics, like communal space and proximity to local amenities.

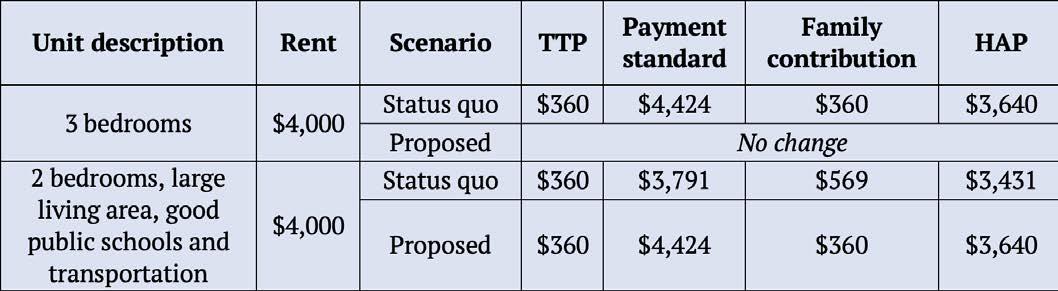

HUD’s current rules that prohibit voucher holders from living in overcrowded units should stay in place. According to the federal government’s Housing Quality Standards, a unit is overcrowded if there is less than one bedroom or living/sleeping room for each two persons. While voucher holders can select units with fewer bedrooms than initially allocated, they cannot live in an apartment that is overcrowded. Box 2 provides an example of how this change would affect impacted families.

Recommendation: HUD should eliminate the requirement that PHAs reduce the initial payment standard if a family rents a unit with less bedrooms than initially scoped.

Suppose a New York City family of four (two partnered adults and two children) is issued a voucher. Their voucher will be for a 3-bedroom unit, with a payment standard of $4,784. If the family has a monthly income of $1,200, the total tenant payment (TTP) will be $360/month (30% of monthly income) and the maximum subsidy will be $4,424.

If this family were to find a 3-bedroom unit for $4,000, below the payment standard. They will contribute $360/month and the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) will be $3,640/month. However, if this family prefers a similarly priced 2-bedroom apartment, their required contribution and HAP will be different. Under current rules, the payment standard would be lowered to the 2-bedroom rate of $3,791 and the maximum subsidy would be $3,431. The family would pay the full difference between the payment standard and total rent ($209) for a total contribution of $569/month.

If the recommendation in this report were adopted, the family described above would be able to rent a 3-bedroom unit with a payment standard of $4,424. A three-person household (two partnered adults and one child) would also be able to rent this unit, but with a payment standard of $3,791.

One feature of payment standards that are particularly burdensome to the Housing Choice Voucher program is the requirement that PHAs prorate assistance for households that include members that are not citizens and do not have eligible immigration status. These constraints are similar in comparison countries, particularly in the United Kingdom where oversight, though inconsistent, is potentially harsh. While it may not be feasible to remove this proration step altogether due to legal and political constraints, it could be altered to still provide mixed families with more flexibility.

Families with mixed citizenship (i.e., some household members have citizenship or legal immigration and some do not) are still eligible for the Housing Choice Voucher program. At voucher issuance, total household income and total tenant payment are calculated based on earnings from everyone in the family, regardless of immigration status. The number of bedrooms on a voucher and thus the payment standard also includes all household members. Proration of the HAP (based on the percentage of eligible household members) occurs after a family selects a unit and families are required to pay the total tenant payment plus the value of the HAP lost to proration.

Box 2. Illustrative example: Eliminating the reduction of the payment standard for families that rent smaller units than initially scoped increases subsidy amount and choice.

Box 3. Illustrative example: Prorating the payment standard at voucher issuance would increase assistance for mixed families and allow them to search with clear information.

Suppose a New York City family of four (two partnered adults and two children) is issued a voucher. Their voucher will be for a 3-bedroom unit, with a payment standard of $4,784.

If the family has a monthly income of $1,200, the total tenant payment (TTP) will be $360/month (30% of monthly income) and the maximum subsidy will be $4,424. If one partnered adult does not have eligible immigration status, these initial calculations are unchanged. However, if the family finds a unit at this maximum subsidy, the housing assistance payment will be prorated by a factor of 0.75 (because three of four household members are eligible) and would yield subsidy of $3,318. The family contribution would be TTP plus the loss due to proration ($1,106) for a total of $1,466 – 122% of family income.

The family can only use a voucher if the subsidy lost to proration (initial subsidy x 0.25) does not exceed 10% of income, or $120 in this example, in order to keep the total family contribution below 40% of monthly income. Thus, this family could currently rent units that would yield an initial subsidy of $480, which when prorated to $360, leaves a family contribution of 40%. The total cost of these units (family contribution plus prorated HAP) would be $840, far below the payment standard.

If proration instead occurred at voucher issuance (as recommended), this family would be subject to a payment standard would be $3,588 ($4,784 x 0.75 proration factor). The maximum subsidy would be $3,228 (payment standard minus $360 for TTP). The family can then rent units up to this prorated payment standard without increasing their family contribution. They can rent units up to a maximum total cost of $3,708 with a 40% family contribution.

Prorating in this last step is burdensome for several reasons. Mixed families are still not allowed to spend more than 40% of their family income on rent, so they must ensure that the amount of the HAP lost to proration does not exceed 10% of gross income. When searching for an apartment, determining which units are in scope thus requires a difficult calculation and severely limits choice.

information (i.e., maximum subsidy) that non-mixed households do. It would also provide them with a larger benefit amount, increase the amount of units eligible for rent and eliminate the need for mixed families to contribute more than 30% of their income, which is inherent to the current calculation. See Box 3 for an example of how this change would affect impacted families.

The most direct and impactful way to address this burden and inequity would be to expand eligibility to noncitizens without legal status, as recommended in the prior section. In the absence of this policy change, an alternate approach would be to prorate the payment standard at voucher issuance. Doing this earlier would allow mixed families to navigate the search process with the same straightforward

Recommendation: HUD should prorate for noncitizens at voucher issuance and investigate the feasibility of eliminating proration all together.