9 minute read

Global model risk incurred by the LIBOR transition By Patrick Toolis

global model risk incurred by the LIBOR transition

by Patrick Toolis

Advertisement

At first glance, the interest-rate migration away from the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), which is scheduled to begin by December 2021 in the United States and the United Kingdom, is little more than a market-data issue 1 .

Rates such as three-month LIBOR will be replaced by their equivalents in SOFR, SONIA, etc, depending on the currency involved 2,3,9,10 . However, the revised underlying instruments, calculation methods, and collateralization underlying the rates means that the levels of these interest rates may deviate from those of comparable LIBOR. In addition, uncertainty about which new reference rate is the standard for a given tenor and the lack of established derivatives products based on the new rates may introduce both new arbitrage opportunities and interest-rate risk.

Lastly, the operational overhead of modifying existing derivatives contracts which will still be in effect during the rollover such that the contractual term LIBOR can be replaced with some permutation of the new reference rate and a spread may be non-trivial. While these changes to the current trading workflow pose several risks, the model risk induced by creating models taking as input reference rates which did not exist during the time periods spanned by historical training data sets may be a more substantial long-term danger.

new overnight benchmark risk-free rates

SOFR (United States)

SOFR is an acronym meaning Secured Overnight Financing Rate and is an average of interest rates paid on US Treasury repurchase agreements 2,4 . This standard was proposed as a replacement for LIBOR in 2017 by the Alternative Reference Rates Committee of the US Federal Reserve Bank. It is published daily by the US Federal Reserve Bank of New York 2 . This rate is used, along with the longestablished US Effective Federal Funds Rate, as the reference rate for overnight index swaps (OIS) 2,8 .

SONIA (United Kingdom)

This acronym stands for Sterling Overnight Index Average, a benchmark published by the Bank of England (BOE). It represents an average of rates used in unsecured sterling overnight interbank loans reported to the central bank. The BOE estimates that about thirty trillion GBP in assets are valued using SONIA annually, and Wikipedia indicates that about twenty-one percent of the floating rate bond market referenced SONIA in 2018 9,10 .

derivatives valuation under the new rate regimes

Eurodollar/Other Money-Market Futures

The Eurodollar futures contract (CME) and Short Sterling contract (ICE) are exchange-traded futures directly

tied to the three-month LIBOR quote in US dollars and pounds sterling 6,11 . Plans exist for the Eurodollar

contracts to be converted to SOFR as needed, and a similar translation of Short Sterling to SONIA could

likely occur 5 . Whether liquidity in the new contracts is sufficient to enable a smooth transition is one issue,

but a key concern to those using quantitative models to price the contracts and pair them with other securities in strategies is whether the yield curve models will translate between benchmarks (assuming that traders ultimately will transition to futures on the alternative rates). The collateralization of the loans underlying SOFR, and the discrepancies in calculation and reporting for all of the new rates may induce permutations in the correlations of the rates to other macroeconomic data or financial metrics. Since these rates were not prominently featured in the past, obtaining datasets which allow them to be considered alongside factors such as employment, GDP, or news sentiment may be a challenge.

Swaps

A vanilla interest rate swap involves exchanging fixed-rate interest payments (the swap rate defined at contract initiation) for floating-rate interest payments (based on a benchmark such as LIBOR). Thus, the primary goal of a model is to estimate a sequence of forward interest rates (from which forward yield curves can be derived). In addition, some credit risk may need to be taken into account, depending on the counterparty, clearing method, and collateralization. The change from LIBOR to SOFR/SONIA/€STR means that any data input into models based on the risk-free spot rate or any forward rates quoted/implied in the market will need to be drawn from different sources and possibly spread-adjusted. In addition, any forward rate models based on historical data, such as neural networks or decision trees, would need to be trained, in most cases (some historical SONIA data may be available), on an older analog of the rate now used (e.g. train using an adjusted LIBOR rate as SOFR).

Swaptions/Caps/Floors

These three products are interest rate derivatives with a contingent claim. For example, a fixed payer swaption gives the owner the right to enter into a swap in the event that the swap rate is above the strike rate at maturity. A cap pays if the floating rate is above the strike rate, and a floor pays if the floating rate is below it. These options might be valued with a variant of the Black-Scholes model where the underlying is either the swap rate or the floating rate. Tree-based models to approximate the possible movements of the short rate are also well-documented. However, parameters such as the volatility of the swap rate or the probability density of interest rate moves over a given time period may depend on models requiring historical data. Should this data be culled from times prior to the creation of the new rates, model risk could be incurred (e.g. if historical Treasury repo rates somehow deviate from SOFR).

A vanilla pass-through mortgage-backed security has the cash-flow characteristics of a normal corporate bond (interest payments, default risk, principal return). In addition, the amortization of principal return and the substantial volatility in this principal remittance due to prepayment risk make the models for these securities somewhat distinct. Prepayment is historically linked to interest rates such as the effective federal funds rate, suggesting that models taking a narrow position on prepayment will use a rate such as SOFR/ SONIA/€STR as an input. The default modeling might be influenced by the current and forecast spread above the (term-adjusted) overnight rate reflected in the MBS weighted average coupon. Discounting of payments to arrive at valuation will of course involve an application of a new risk-free rate as well. More exotic collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) instruments, involving inverse floating-rate notes, tranching of the securities, and planned amortization classes, might involve more complex models with more subtle adjustments due to the interest rate change.

Credit Derivatives

Credit derivatives are instruments where both interest rates and the default risk of an issuing party are factors in the valuation. For example, in a credit default swap (CDS), the CDS premium is the quarterly amount (percentage of notional) paid to ensure that the discounted expected value of the premiums equals the discounted expected value of all amounts received over the life of the swap. The premium, though, is also the credit spread above the risk-free rate (traditionally LIBOR) for the appropriate tenor, as the “protection buyer” of a CDS is purchasing insurance against ratings downgrades, defaults, and other credit events. Thus, as the overnight rate fluctuates, the term-compounded rate used as the risk-free rate over the premium period also moves. If the risk-free rate rises and the premium remains the same, arbitrage opportunities involving the CDS and corporate bonds may arise. Cash flows paid and received under the swap need to be discounted using the current yield curve, as well. Historical macroeconomic models designed to determine relatively strong and weak firms for credit investment may depend on the short-term rate, so training such models with the correct approximation of SOFR/SONIA/Estr will be critical.

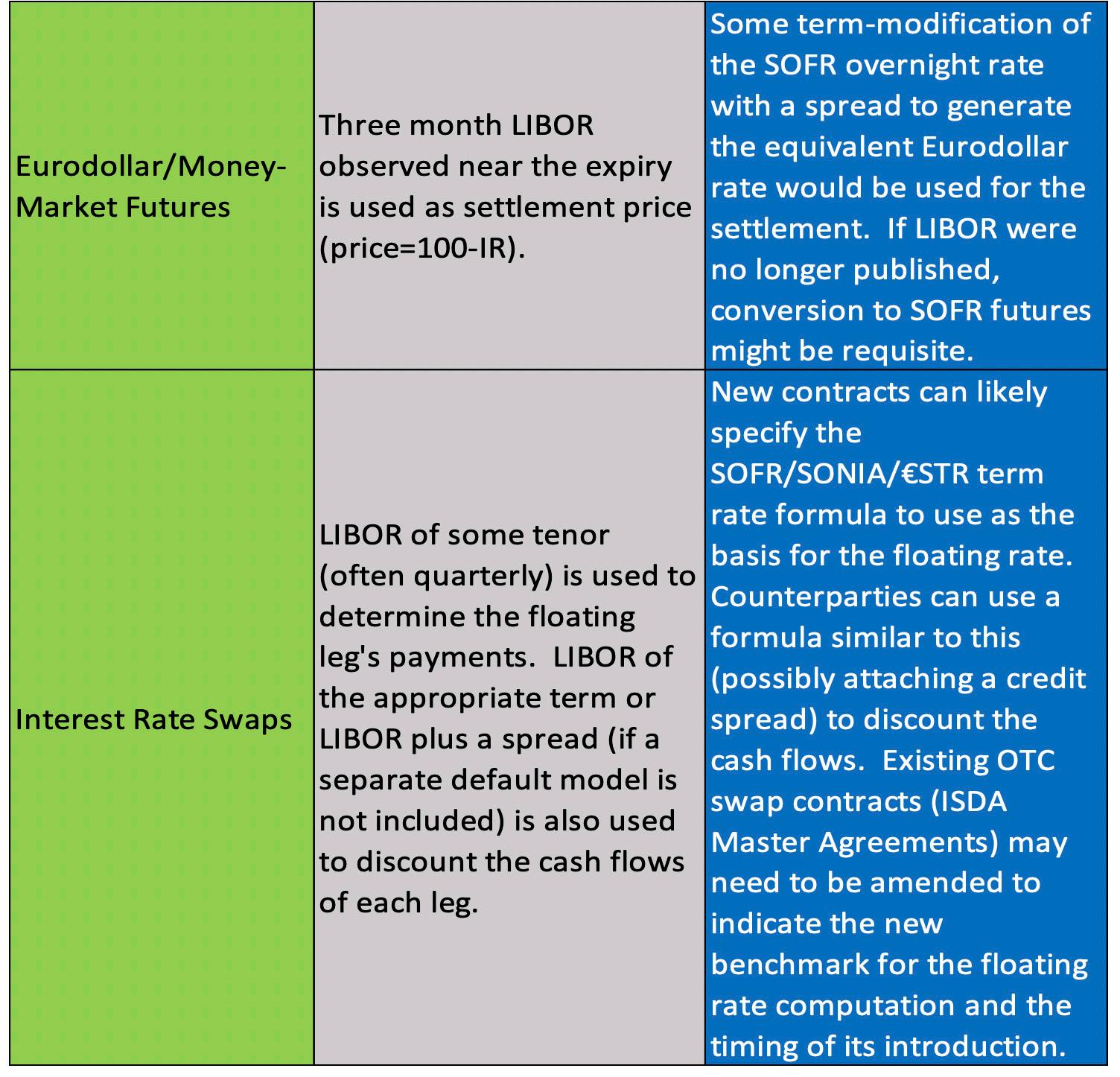

Figure 1: Impact of LIBOR transition on major derivatives products

On the surface, the LIBOR migration is primarily one of nomenclature with some minor calculation adjustments. Three-month averaged SOFR and three-month LIBOR do seem to follow similar trajectories 2 . However, given the enormous notional of exchange-traded and OTC derivatives tied directly (e.g. Eurodollar futures) or indirectly (e.g. MBS) to short-term interest rate levels, the impact of any change to this data point can be significant. Portfolio credit risk and interest-rate risk, both components of Basel capital requirements, might need to be reconsidered in light of the change in reference rates. In addition, any machine-learning or statistical models which are calibrated using historical data might have to consider the disconnect between the rates available in the past and the rates used to value today’s derivatives. Validation and modification of models to accommodate the new benchmark rates may be critical to effective risk management across asset classes.

references

1. Wikipedia contributors. (2020, February 13). Libor. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Libor

2. The Alternative Reference Rates Committee. A User’s Guide to SOFR. April, 2019. Bank of the Federal Reserve and New York Fed. Retrieved February 21, 2020 from https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/Microsites/arrc/files/2019/Users_Guide_to_SOFR.pdf

3. Thomson Reuters. Factbox: The global benchmarks replacing Libor. Reuters.com. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-libor-transition-factbox/factbox-the-global-benchmarks-replacing-libor-idUSKBN1WN0HN

4. Wells-Fargo Research Team. Get Ready for SOFR: A Primer. FXStreet. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.fxstreet.com/analysis/get-ready-for-sofr-a-primer-202001311413

5. Stanton, Elizabeth. LIBOR’s Demise will Upend How Hugely Popular Derivatives Work. Bloomberg. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-11-12/how-libor-s-demise-impacts-a-hugely-popular-derivatives-contract

6. CME Group. Eurodollar Futures Contract Specs. Futures and Options Trading for Risk Management-CME Group. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.cmegroup.com/trading/interest-rates/stir/eurodollar_contract_specifications.html

7. European Central Bank. Euro short-term rate (€STR). European Central Bank, Eurosystem. Retrieved on February 24, 2020 from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/financial_markets_and_interest_rates/euro_short-term_rate/html/index.en.html

8. Feeney, John. SWAP VOLUMES: SOFR V FED FUNDS. clarusft.com. Retrieved February 25, 2020 from https://www.clarusft.com/swap-volumes-sofr-v-fedfunds/

9. Bank of England. SONIA interest rate benchmark. Bank of England. Retrieved February 25, 2020 from https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/sonia-benchmark

10. Wikipedia contributors. (2020, January 10). SONIA (interest rate). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 25, 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SONIA_(interest_rate)

11. Intercontinental Exchange. Three Month Sterling (Short Sterling) Future. Intercontinental Exchange. Retrieved February 25, 2020 from https://www.theice.com/products/37650330/Three-Month-Sterling-Short-Sterling-Future

Patrick Toolis

Patrick Toolis has spent twenty years involved in theoretical computer science applications in five countries. After co-founding J-Surplus.com, one of the first business-to-business e-commerce auction sites for excess inventory in Japan, Mr. Toolis worked in the system integration realm at Iona Technologies, dealing with major customers in telecommunications and semiconductors. He then helped develop the order and execution processing at JapanCross Securities, one of the first electronic crossing networks for Japanese equities (later merged with Instinet, which is now a part of Nomura Holdings). As a consultant, he wrote significant machine learning implementations on mobile computing platforms for Sears Holdings Corporation. At The American Express Company, he designed parallel algorithms for risk mitigation and decision optimization. Most recently, he has focused on independent financial engineering work which he aspires to grow into a hedge fund, software vendor, and liquidity pool and has consulted for a private trading firm and a new exchange. Mr. Toolis holds BS and MS degrees in Computer Science from Stanford University.