PARALLAX PARALLAX

Life happens in liminal spaces, the in-between, the not-quite-there. We are often in TRANSITIONS, whether physically making a long commute or growing between childhood and adulthood. Instead of focusing on the here and now, we find ourselves LOOKING FORWARD and LOOKING BACK, wondering, planning, and yearning for another time, another space. Sometimes the liminal means that we are not quite in reality, lost in DREAMSCAPES. These thoughts inspire our cerebrations and our creativity. Open our book and see what ensues when we enter those liminal spaces.

This publication is dedicated in loving memory to Edith Schrank. For more than a decade, she taught English in a distinguished and distinctive fashion. She had the capacity to impart to her students a sense of urgency about reading and an appreciation for the written word.Daniela Woldenberg

Tova Solomons

Solomon Taragin

Joyce Salame

Olalla Levi

Lauren Goodman

Sasha Dunst

Tova Solomons

Daniela Woldenberg literary, Dr. Edith Lazaros Honig art & design, Ms. Barbara Abramson photography, Ms. Sari Goodfriend

Parallax is the creative writing club of Ramaz Upper School, as well as the name of our literary & art magazine. The club meets every Thursday after school. Parallax is a juried publication that comes out in June in time for distribution at our annual Celebration of the Arts. Parallax 2023 was printed by Allied Printing on 80 lb. bond. Copy and layout were prepared by students on Apple Macs in InDesign. 350 copies were printed. All rights belong to Ramaz Upper School, 60 E 78th Street, New York, NY, 10075.

Alissa

Josh

Charlotte

Daniela

Charlotte

Charlotte

Sasha Dunst

Jem Hanan

Joyce Salame

Alissa Rose

Sasha Dunst

Manie Dweck

Aravah Chaiken

Charlotte Newhouse

Alissa Rose

Shulamit

Joyce

Alissa

Alissa

Thea Katz

Solomon Taragin

Sasha Dunst

Olalla Levi

Haim Heilborn Nigri

Leo Eigen

Shulamit Tarnovsky

Daniela Woldenberg

Olalla Levi

Hannah Kanbar

Ari Porter

Manie Dweck

Daniela Woldenberg

Sasha Dunst

Talia Larios

Tamar Sharon

Olalla Levi

Lauren Goodman

Tamar Sharon

Alissa Rose

Thea Katz

Olalla Levi

Charlotte Newhouse

Daniela Woldenberg

Tova Solomons

Leo Eigen

Joyce Salame

Ari Porter

Alissa Rose

Daniela Woldenberg

Photograph

Rose

Sasha Dunst

Tova Solomons

Gianna Goldfarb

Solomon Taragin

Joyce Salame

Sasha Dunst

Alissa Rose

Sasha Dunst

Haim Heilborn Nigri

Sasha Dunst

Gianna Goldfarb

Grace Cohen

Solomon Taragin

Alissa Rose

Daniela Woldenberg

Sasha Dunst

Jem Hanan

Sasha Dunst

Alissa Rose

Hannah Kanbar

Lauren Goodman

Sasha Dunst

Solomon Taragin

Sasha Dunst

Sasha Dunst

Lauren Goodman

Sasha Dunst

Josh Chetrit

Sasha Dunst

Joyce Salame

Ari Porter

Ari Porter

you stand in the center of it all, being pushed both forward and backward, further in and further out.

there is the magnetism, the inexorable urge to be farther away from those with whom you align, but as you’ve heard, opposites attract, somehow.

so there you are in the center of it all, plagued with the inescapable desire to remain there, to never return home; and with such a desire to remain, becoming who you once were has been redacted from the manual of life; you no longer exist before this moment, the moment when you stand in the center of it all, unable to return home no matter your longing because the desire to remain there is all the greater.

in the center of it all you are nothing but electrons, merely potential to be. you are the pebbles by a stream. you are the wrath of your father and his father before. you are the ripened fig of the lost garden. you are the bed beneath you. you are nothing.

the honeyed magma in the center of it all encases you, but you too are the magma. you close in on yourself. it closes in on itself. you and it slowly run yourselves in circles. you are churned by the earth.

Ren had forgotten what time meant. He knew what it was, like when he checked his wristwatch to see when his next class started. But the substance and articulation that came with the notion, the edge of time, had dulled. Oftentimes, Ren didn’t know when it was yesterday or tomorrow or if today had happened at all. It all blended together in some crude imitation of an amateur painter’s palette. His life was bookmarked not by time, but by landmarks, the places he needed to be. His bedroom, the subway, the school, and always, his mother’s house.

There was something of a routine at his mother’s house. Ren would walk in through the front door, and immediately the bitter smell of bleach and synthetic lilac would hit him. He never got used to it. “Ren, is that you?” his mother would say, and Ren wouldn’t even bother to answer. He’d make his way through the kitchen, the living room, and the dining room. He thought there would be some sense of sentimentality seeing the now-empty rooms, that he’d get visions of his childhood, but he never felt anything. He didn’t know why he expected it. Rather than memories, there was only disappointment.

It was a mystery to Ren what the room his mother stayed in now had been before. The windows that let in faded sunlight and the stained, carpeted floor

felt unfamiliar to him, though he knew the room must have been used for something. Perhaps a playroom. Now, his mother laid in a chalky bed right at its center, unmoving. It was an island that nobody else could access. Or maybe they could; Ren hadn’t bothered to try.

“Ren, come back and live with me,” she’d whisper to him from the bed, featherlight fingers brushing his knuckles. “Look how pale you’ve gotten.”

You’re selfish! he wanted to scream the first time she had said it. The second too if he was being honest. After the third, Ren’s expression remained blank. The fourth, and the words hollowly entered his consciousness before drifting out untouched. He’d give his mother’s hand a comforting squeeze filled with fallacy. He’d straighten out the covers that seemed to swallow her frail body whole. He’d replace the water in the chipped vase at his mother’s bedside.

“What a good boy,” his mother would murmur, disregarding Ren’s dismissal of her offer. Ren would sit in the chair in the corner of the room and watch his mother, silently. Even if he did speak to her, she would never answer. The only sound that would fill the room was her labored breathing and the occasional tone from one of the machines that had become more a part of his mother than her own body. At five in the afternoon, he’d stand, his mother would say goodbye, and he’d leave. He would rub his eyes and feel the skin beneath them sag. Heavy exhaustion would painstakingly seep out of his bones while he walked away from the house and his mother, only to be replaced by a barbed, bitter guilt.

Lauren Goodman

Lauren Goodman

We open on a hot, humid night on the beaches of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, otherwise known as the ass-crack of the east coast. It is regarded by many as one of the trashiest areas in the American South - a region well known for its trashy areas - but don’t be fooled. Through the endless columns of smoke rings, reckless spring breakers, and staggering drunks of the city, one may find a love story for the ages at the center of it all.

It’s a tale as old as time. They meet under a yellow streetlight. It flickers a little, signaling to bystanders and clueless tourists like me that the show is about to begin. He tells a joke. She laughs. He motions towards his motorbike, which he had recently tricked out with millions of flashing LEDs. She squints at it, nods, and believes the cheapness of the light fixtures to be out shone by the richness of all their colors.

My mother does not agree. We sit at a restaurant across the street from the impromptu roadside attraction. She rolls her eyes at all of the motorbikes, the LEDs, the seedy characters cloaked in the night. She remarks, in her snarky Bronx accent, “I’m so glad we’re able to take you to such high-class places.” I don’t really hear her.

When one dines outside on a Florida beach, dinner always comes with a show - and this one does not disappoint. In an instant, she is defying gravity in her lover’s arms, locked in an embrace under that yellow spotlight, bathed in technicolor hues, electric pinks and reds. Across the street, I watch - aghast, in awe, and, eventually, wildly impressed. I can’t help but admire how they refuse to conceal any part of their smoke-bomb passion, letting it waft into the evening air and mix with other vapors almost as intoxicating.

I am too wrapped up in the story across the road, waiting with bated breath for the next scene. I know what is going to happen. At this moment, I am more curious about whether I will actually get to see it, or if a godly censor will strike the two lovers, leaving them in an unintelligible mess of pixelated passion and bleeped-out sentimentalities.

I get to see some of it, of course.

My mother notices, too, and makes a side plot of her own to go along with our main story. She gasps, almost choking on the billowing clouds of audacious love. I look around the restaurant and observe all the pearl-clutching vacationers covering their children’s eyes, pleading with them to look away from an act that begs to be seen. I look across the street again. As he lets her down, I wonder what it must be like to be shameless, to possess the kind of fearlessness it takes to put on a show without realizing it. To feel the gaze of a thousand scandalized Jewish mothers like a feather against my back, paling in comparison to an offensive, explosive joy colored with eye-straining neons and flickering yellow streetlights.

With that rumination, the story comes to a close. He secures a helmet on her head. She hops on the back of his majestic, seizure-inducing motorbike. They speed away, leaving me in the dust, still watching, hands aching to give a standing ovation.

A pastel pink stains my fingertips, as I crouch near an abandoned hop-scotch, sloppily scratching slanted letters, with dusty, cylindrical chalk. I look up from the pavement and meet my mother’s elated eyes.

My knees sink as the warm sand beneath me scrunches. With a snapped twig, I swiftly sign my name on the surface and watch the sand part, making way for careful calligraphy, before the ocean washes over its mountains and valleys, stealing (from) me.

In one hand, his fingers are intertwined with mine, and in the other, he holds a blade. Roughly carving our initials into the bark of a tree, he unites them with a simple ‘+’, circumscribes them in a heart, and extends Cupid’s arrow on each end, promising me “always and forever.”

But we lie beside each other, beneath the earth, returning to dust, our names carved in stone above our heads, asking us to “Rest in Peace.”

Through writing, I introspect. The process initially, frequently has proven to produce a discombobulated collection of thoughts echoing endlessly – each a deformed shadow of an idea that I cannot quite put into words – until some revelatory, unpredictable moment of inspiration leads to clarity, to synthesis. And once I have captured some semblance of “me” on the page – or, at least, who I understand myself to be – I scrutinize that fragment, considering her flaws and her virtues, her actions and her compulsions— the ways in which she engages with herself and her society.

Tova SolomonsSuppose life was not an orchid petal:

Perched, staring at lonely flower corpses

Littering the fractured soil beneath

The observatory to which it clung, Knowing it would one day lie among them –That regardless of its bloom and beauty, Its creases and stains and its bowing spine, It, too, would submit to evanescence, With the dry dirt its only certainty –Otherwise vague, incomprehensible –So it would hug its origin tightly, Blossom and wear multitudinous hues –Clutching what it could, the fathomable, Its mind abandoning the dirt, until…

When sheer desperation would not suffice, And its straining body wilted on the vine, Its gaze would again fix on the fallen… Faded husks – crumpled and solitary –Barely a whisper in its memory, Amidst a din of indistinct whispers… And regret would further sag the petal, Recalling water so undervalued And sunlight not savored, ephemeral…

So, consumed with despair, its grasp weakened, It could hold on to its stem no longer And softly swayed to the petal graveyard…

Eyes mere moments from closing, it answered: Alas, life would not have been worth living If it had not been an orchid petal.

Tova Solomons Tova Solomons

Tova Solomons

I am grateful for the flowers that bloom in my lungs, For the moss growing on my bones, For the vines that replace my veins.

I am grateful for the sighing wind in my throat, For the thump of wings against my chest, For the craters of night that allow me to see my slow decay.

Life is but a passing moment, spanning a thousand years in only a second, the universe so vast that my gratitude may as well be a shout into the void, but at least I am shouting, breathing, living one more second.

And that is enough.

When the wrath of winter seems eternal, And the sky is cold and black and glum, The night so long that the world’s nocturnal, Know that winter will end, and spring will come.

The seeds deep in the ground will turn into stems, The bees and the bugs will scare us again, The rays of the sun will fully descend, The sky will fill with finches and wrens, The flowers will grow into jewels and gems, The days so pretty you can’t comprehend, The troubles and worries and doubts will mend, Winter will end.

And spring will always come.

I’m currently undergoing the ultimate form of a joyride: running away from my problems. Oh, and I’m with a friend. It was his idea. Tyrion has many good ideas. Backtrack – why did we go?

Things have been pretty shitty of late. For a while now, things just haven’t been working out in my favor. It’s 2022 and in 2022 the real form of failure doesn’t come from failing in a pursuit of accomplishing something worthwhile: the true failure is failing to be popular –and on that account, I’ve failed beyond measure. Things used to be relatively okay. I was a pariah, perhaps, but I was still in the room. Now I don’t even know where the room is. My parents and siblings participated in a joint suicide without me. In the end, even my own family did not want me with them. Now they’re dead, though.

My school expelled me because – in their words – I wasn’t spreading “positive vibes.” I hadn’t even known that lacking “positive vibes” could warrant expulsion.

With a tragic downfall there’s only one silver lining: you discover who your true friends are. In my case it wasn’t “friends” but only “friend.” Tyrion was by my side the whole time. He sat next to me at my family’s funeral and told me that they were idiots for not wanting me to be involved, but that he was glad they hadn’t asked me because he prefers me alive. That made my

day. When I got kicked out of school, he even dropped out in solidarity! He told the principal that the grounds of my expulsion were preposterous. Tyrion’s family are generous donors of the school, so they will regret their decision soon enough. Tyrion is a true, loyal friend. And then came the final, and undeniably, worst blow of all. After waking up one day at 2:30 PM – as school was a nonfactor – I walked over to the TV to turn on the XBox, only to discover a tragic truth: it would not turn on. My Xbox was broken. Right then and there I knew that I had to get out. I couldn’t bear to live in a home without my XBox.

I called Tyrion, crying. “Please come pick me up,” I begged over the phone. “This loss is too heavy. I need you.”

“I’ll be right over,” Tyrion replied. As I said, a true friend. He picked me up in his parents’ Maserati. “Over the phone you sounded like you needed to get out of town for a bit. And you know how I love to travel in style.”

I smiled for the first time since my Xbox stopped working. I hopped in the car and we sped off. After a long while of peaceful driving, I began to notice that the road was leading us towards the middle of nowhere.

“Tyrion,” I said. “This road doesn’t lead anywhere.” “That doesn’t matter,” he replied. “What does?” I asked, after a little while. “Just that we’re on it, dude. Just that we’re going forward.”

Suppose the leaves never fell to the ground, never turned and twirled in the air into a crunchy yellow and brown path. Suppose there was an infinite amount of chlorophyll pumping through the trunks of New York City. That the sun felt hooked, anchored to rest finally on the western hemisphere, forgoing its old habit of just staying for three months. After August the warm air and ice cream trucks couldn’t bring themselves to say goodbye, and so they stayed indented into the city streets. The twinkle of sunlight became tattooed across the tri-state area bodies of water. The innate presence of beauty in all of summer’s limbs— the sunset, the fields, the sweat, the thrown back head, the trails of laughter, the friendly eyes, the duality of delicate hair (tangled in seawater and gently swept away by the wind), the fascination of berries and other washed fruit— became a permanent fixture of the cityscape.

The sticky consistency of summer hardens into a crystal. I look into it now and see the glimmer it reflects into my eye. I want to transport into that magic ball or let what it’s projected into my eyes become more than an imaginative utopia.

You stand there in conflict. Unable to decide.

You’ve realized that it is time to move on, to mature. To become an adult. But you cannot. Gone will be the birthday parties and cupcakes and pizza. There will be no more mindless hours in the backyard on late summer afternoons, nor will the tooth fairy ever visit you in your sleep again. The melody of the ice cream truck won’t be the peak of excitement. The A+ grade on a spelling quiz will no longer be displayed proudly on the refrigerator.

Now, life will be full of burdens, of responsibility and of work.

“What do you want to do when you grow up?” This will no longer be an annoying question adults ask you, but something serious to be considered. Sleep each night will become a coveted gift, not an insufferable chore. Now words like “career” and “salary” will not just be abstract. Soon you will have to restrain your selfish ego when talking to peers. And your schedule will always be full, with no time to unwind. And so. You stand there on the brink, unable to bring yourself to cross the boundary.

You have already realized it is inevitable. It must happen. It will happen. There is a season for everything, a time for all experiences under the sun.

Before you had time to wonder, it happened thus.

I hope you get better In all the ways that you do And the vines that Curl around you and Hold their grip–I hope they don’t.

When does the snow start falling? When does the cold air come so that it can leave? It feels like we’re trudging along here but we’re only still at the beginning.

You

Hannah KanbarHow are you the way you are?

And why do you inspire such intricate disillusionment Or oblige me to defend false scenarios?

Each time you change an octave you coerce me into dissecting your tone.

I feel compelled to look for something to prove me right

Or maybe for something to prove our spite.

You could speak one syllable

And another piece of who you are would disintegrate.

I know I am being manipulated,

Only I can’t tell if it’s your doing or my own.

Of course, you abandon me to guess

Until finally you become a stranger.

You achieve precisely what you intended.

You get to live in your all-encompassing bliss

While I remain under your interminable torment, Unable to stop asking the question, Why are you the way you are, And how do you instill the delusion That somehow you are still my you?

Tears line the bags under her eyes

Provoking her strong will,

Inciting her to release them so they can Trek across her cheek

She distracts herself, running her hand

Repeatedly, almost violently

Through her shoulder-length hair

And when she looks up with those sad eyes

I haven’t seen in over a year, I avert my eyes and turn to the ceiling,

Blinking back the water welling in them

But she clutches my head and angles it down

Because even though she may risk revealing her grief, She cannot let me suppress mine

So I meet her gaze

And we both start crying hysterically,

And when she lets go, I let out a laugh

And then she does too.

Daniela Woldenberg

It scares me that I can’t remember anything from before two years ago

Maybe the overwhelm of emotion

Overshadows the monotonous existence when everything I felt was muted

But not negatively so Picture a beach as the day winds away

And don’t assume my more recent existence riddled with sunlight has been pleasant I want to turn your attention to the burdensome boils that have scorched my back

And my pruney hands that can barely write

Daniela Woldenberg

She longed for a new experience

One as fresh as the citrus on the night table

Flesh bursting with the potential to feel again.

Hair sprawled on the silk pillowcase

Her eyes stung

Fixated on the ceiling

Cracks in the yellowed paint.

It was too discolored for her to bear

Yet she could not find the strength to repaint it.

Time was passing by

The sun still rose in the east and set in the west

The citrus was at peak ripeness

Untouched, unexplored, uncontaminated

Its exterior perfectly firm

A vivid, glistening yellow.

She could practically taste the inside

Superbly sweet

The fruit was ready

And so was she.

Arm’s length away

It would rot soon

But under that yellowed ceiling, a bed of quicksand clutched her

The more she struggled to break free, the farther she sank.

Slowly, slowly

One small movement at a time

She was able to sit up

She froze.

“You are not ready yet.”

All she wished to do was to lie down

To disappear into the quicksand

But this time would be different.

Crowding out the voices

The fear

She grabbed the citrus from the nightstand

And broke the skin.

Sinking her teeth into the flesh

She pursed her lips.

It wasn’t ready yet.

I remember her stem standing, proud and ripe It was arrogant and rash and reckless I remember her leaves drooping, limp and gauche A green blush tinting their tender, round cheeks

I remember her petals beaming, mirthful Gilded veins of innocence within each I remember wondering if the naming Of beauty was worth its desolation

I forgot my answer

i tried to remove the space between us by digging through the sand–fine grains of gold lodged behind my fingernails, uncomfortable and unmoving, suffocating in a place they never belonged yet chose to adhere to–until, i felt His blue (or maybe green) twine wrap around me like rings. and i pulled, and His twine became mine, and i pulled, and i destroyed His creation, and i pulled, and His tide came undone.

i tried to remove the space between us but the twine remained behind me anyway, threaded on itself endlessly, a planet in the sand, as i ventured on a bed of seashells and seaweed and sea stars, all so i could see You again. and i walked, chasing Your footprints, and i walked, for You were several miles ahead and i walked, while You were nowhere to be found. but i don’t understand… i unraveled his ocean for You.

let us live like flowers, wild and free and drenched in sunshine. let us anger like the sea, a tempest of crashes, untouchable. let us love like time, infinite, eternal, intangible. let us be human.

Human Alissa Rose Sasha Dunst Aravah Chaiken

Aravah Chaiken

I stared at the empty whiteboard. Into the vacuum of the clean slate, my body separated from the moment like I was some kind of parade balloon looking down on my own life. I was the first to arrive at class, which I immediately regretted as I sank into a chair in the middle somewhere.

“Welcome to Calc.” The sleeves of Mr. Jessup’s tweed blazer crept up his arms as he leaned forward on his desk. “How are you?”

I panicked. Blurred images drifted in fragments that failed to fit together. Everyone had danced around the question for months. “How’s she doing,” they asked my parents. But I attempted to do the work. Weekly meetings with a therapist where I pretended I was fine and she pretended that she believed me. Sometimes I could connect words to feelings, but most of the time I went back to the same three words: good, fine, and better. Those sounded like things I should be feeling. More and more, though, there was no feeling. Just nothing. I was numb, stuck in a Groundhog Day loop, waiting for her. Like I’d go to sleep and wake up and she’d be there. But I couldn’t say that out loud. That wouldn’t be progress.

Each day I was supposed to do the exercises, get better and then cured, so life could go back to normal. How was I doing? My tongue just sat there, stuck in my mouth. Like I had contracted lockjaw.

“I’m good, Mr. J.” T.J. sauntered in and sat right in front of me, claiming the attention for himself. Making himself useful, for once. He bantered about sports games and wins and losses. I stared into the blankness of the whiteboard.

Around me a current of classmates flooded in, mostly ignoring me, the chitchat drowning out the quiet. The blank whiteboard soon became overwhelmed with symbols and equations, the curved integrals like the kelp that hid in the water and ensnared me with its slimy fingers. I tried to escape their grasp, but they kept pulling me back - back a whole ten months. That weekend we visited our cousins in New Jersey. My sister Dalia never properly blended her sunscreen, appearing like a ghost, yet so alive in any park or forest, chasing fireflies and calling each of them “Steve.”

Our uncle had tied the canoes, “Twilight” and “Dawn,” onto the top of their Dodge using bungee cords when he drove us to Lake Tarlo. It took all of us to unload them from the car and push them into the water. “Twilight’s” white dots over midnight purple appeared to twinkle in the harsh sunlight. Dalia loved it. She begged for a ride and since it seated two, I was deemed the responsible older sibling and deputized “canoe captain.” Aunt Audrey and cousin Milo, barely four, took the other one, “Dawn.”

We jostled the oars in our hands until we figured out how to hold them comfortably. And even then it took us a little while to figure out how to coordinate the rowing. We spent the first fifteen minutes rowing in circles. The temperature hit 90. A typical July heat wave, the wispy clouds an empty promise of a respite from the sun. The water glistened in all its sun-drenched glory, giving us a blinding light show of sparkles. Dalia was enraptured.

The wind began to pick up a little, and we welcomed the natural air conditioning. We lagged behind our aunt who single-handedly rowed several boat lengths ahead of us. Cousin Milo’s oar hovered in the air, his pretend strokes not even grazing the water.

The wind pushed against us. We dug our strength into deeper strokes, but the wind kept pushing us back, preventing us from making any progress at all. Dalia laughed at the game, her ringlet curls escaping her headband and fluttering against her forehead. It was pure summer fun. Her tiny frame didn’t quite fit the youth lifejacket. The neon padding stuck up around her shoulders which exaggerated her giggles, bouncing under the blocky foam. Petite for her age, she was used to having clothes hang off her small body. After a whole production of tightening the straps, the adults had decided she’d be fine.

“What if we capsize?” I asked. At least I think I asked. Hadn’t I asked?

“That just won’t happen. These are too sturdy,” Aunt Audrey had assured me, even shaking her canoe back and forth, to Milo’s distress, just to demonstrate. “See? They’ll never capsize.”

And then we coasted, letting the wind carry us along. Our canoe glided along as the water rippled around us. It was a glorious moment. And it haunted me. Every day since, I see Dalia’s face alight, the shimmering water behind her, the wind tousling her curls. We were lake queens for one brief moment.

What happened next is a jumble of memory fragments, like a shredded photograph where the pieces never quite fit back together again. We hit the water. We were city kids. We didn’t know how to swim. I flailed my arms frantically, floating by the grace of my lifejacket; around me my flipflops floated nearby along with my Yankees cap. The overturned canoe began to sink. There was shouting. Aunt Audrey paddled over.

I see her mouth moving, but I can’t hear anything. Water splashes into my eyes, distorting my vision. I see blobs, but no distinct images. The sparkling water has turned murky and dark. Somewhere inside me an alarm goes off; it is chaos. My arms and legs slap the water, raging against it like a cage fight. I don’t remember when my feet found the ground beneath me. Just a strong arm lifting me up still kicking and slapping the shore. This weird shard of memory stands out — I am trembling in the 90 degree sun, grasping one of my flip-flops, with a bizarre pattern of purple figs. I am clutching this because it is something to hold on to — an anchor. Someone throws a towel around my shoulders and I am still shivering.

Everyone always said Dalia was the cheerful one. She wanted to be president. There is still her first grade picture on the wall, at home. She misunderstood the instructions for picture day and insisted on wearing a business suit and bright pink tie. Dalia and her suit, always fighting, swimming toward her future.

Sitting there on the dock, I see my mother running toward me from the picnic table where they are eating warm potato salad and tuna sandwiches. She hugs me. I can feel her heart warm and fast through my towel as the water begins to drain off me. And then it goes gray with a few drops of color. The bright red of the towel. The blue of my mom’s sandals.

“Where’s Dalia?”

Ten months later the question still

hangs, like Christmas lights in March. I can feel each individual drop of water clinging to my skin, staring at the dead water. There is no more wind. No more ripples on the surface. No more twinkling. The adults cup their hands over their eyes and scan the lake’s surface until they spot it—neon straps still buckled, drifting towards the shore. Audrey sprints into the water, but when she grasps it in her hands, it is empty.

“Dalia!” They called for her. But the lake is empty. It doesn’t call back.

I can’t breathe. The screams rush through my ears. I am completely submerged. The ambient sounds come through muffled as if filtered through ear muffs. That is my new life. Those moments rehashed again and again, in an infinite Mobius strip.

Chaos had taken her. And chaos is a fickle god. Why had I fought him? I imagined I felt her arm reaching for me. Had I slapped it away? Could I have reached out? Held her? We could have slipped together beneath the mysterious water and drifted into the calm world beyond. Time has ceased to crawl forward. Each excruciating moment, a tug backward. I see her hand reaching for me and I reach back. I tug at the plastic tabs holding my life jacket in place. I release it and watch it glide past.

“Do you have an answer?”

Mr. Jessup is standing in front of me, so close I can now make out the equations scrawled on his tie. It is silent. They are staring. I am ensnared in their attention. Yes.

I am drowning.

“That is my new life. Those moments rehashed again and again, in an infinite Mobius strip.

I turn on the light, illuminating the dim office. Papers are stacked in every corner, an occasional book or binder peeking out between the sheets. The leather chair hugs me as I sit and inhale the old smell. They are already here.

Some sit on the floor, while others stand awkwardly, leaning on whatever they can. They saved the chair for me; I am the oldest. I start with the youngest, only five if memory serves me right. She is nervous, afraid to do something wrong. If Mama were here, the girl would hide behind her leg. I give her a smile. She blushes, and I decide to move on, not wanting to embarrass her. I look around the room at all the others. There is so much I want to say to everyone here, but I don’t have the time.

One of the girls giggles. She is fourteen and the most confident she’s ever been. I don’t tell her that will fade.

“Do you miss us?”

I turn to the source of the voice, finding the girl in the fifth grade. She wears colorful pants and a flower in her hair, which she will chop off at the end of the year.

“Sometimes,” I say.

“I think I miss the gentle way people treat you. Now all they do is demand things. But I never want to be you again. No.”

The best and worst thing about the past is that it stays.

The fragments left behind by autumn were swept away in a single gust. They beat against the blacktop until they were inexorably drawn up to the gray clouds, like a child’s released balloon. Those crimson leaves have never appeared more dull. The time of nature’s confetti was gone.

And just like that, in a moment so fleeting, so insignificant, winter had taken its place. The clouds were less of cloud and more of a great, looming mass that was slowly caving in on itself, liquid and gas bending both forward and backward, sinking in and protruding out–preparing for something martial.

They lowered themselves down to the tip of my nose, over my eyes. That damp air sent dew drops to the exposed skin from my coat onto my hair.

Encased by the fog, I was safe. But there was a battle above me–the civil war of the great mass, the slamming of gaseous bodies and the baritone shouts they released. The fire from winter’s guns flashed before I knew they ever went off.

The fog no longer felt as safe as it once had, but now there was nowhere to run. Under the weather there was no escape; the only moment of relief was when its soldiers began to cry.

It’s almost as if it draws you in.

Like you were meant to be there.

Like it wants you.

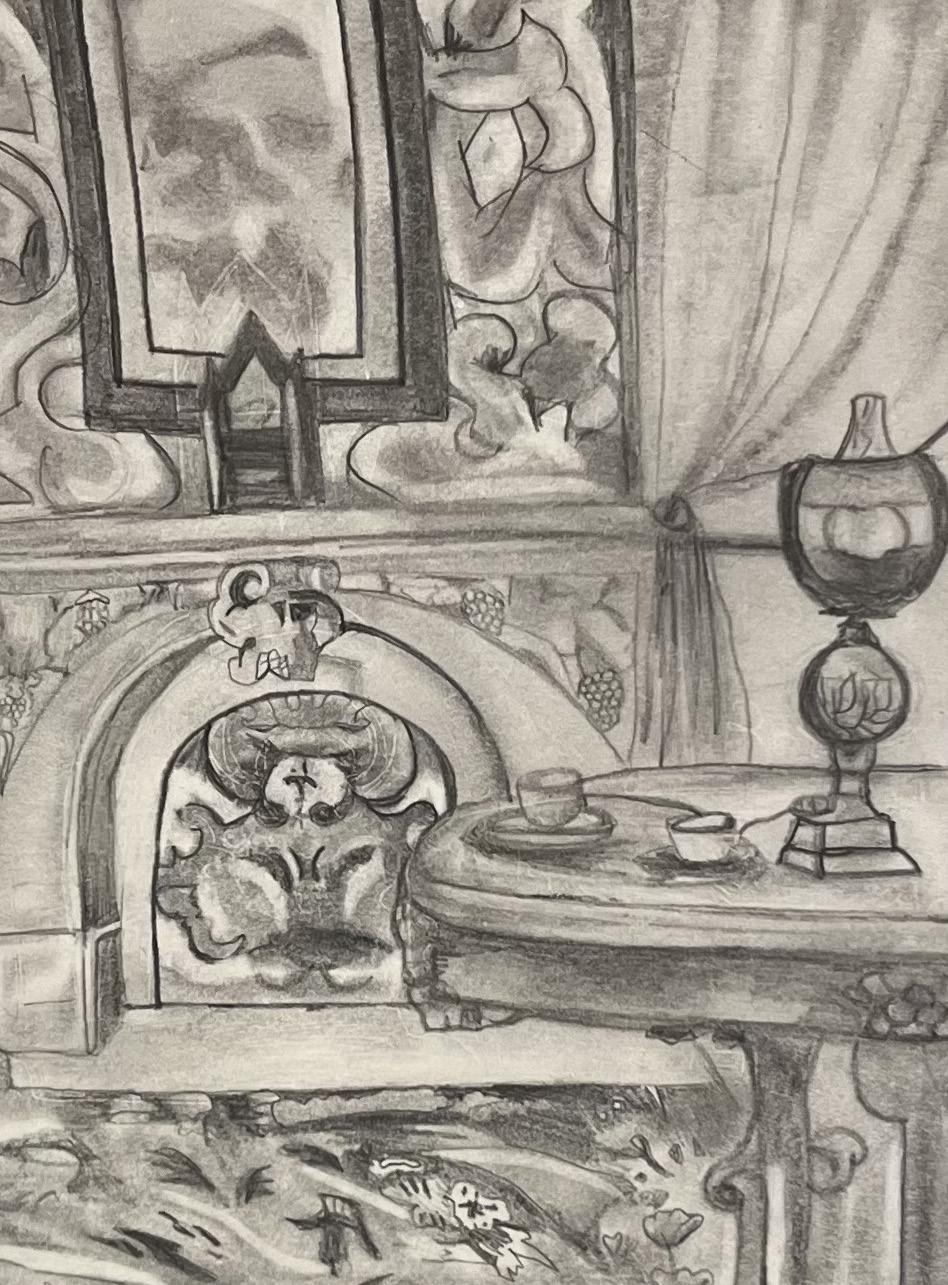

Stacks and stacks of vellum paper are covered in a scrawling hand, scattered all over the walls. The words are in a language you don’t understand, but that looks like something you recognize. As you step through the doorway you get hit with the faint smell of coffee. You slowly let your hands trail across the dusty cover of a book, creating an intricate pattern. The title is in the foreign language. Deep breath in, deep breath out. Breathe. This room radiates calm, a feeling you haven’t felt in who knows how long. It’s almost as if you’ve finally made it home. As you continue your tour of the room, you notice faint ambient lighting, coming from nowhere in particular. You turn a sudden corner, and you find in front of you a round, stuffed armchair, with a mahogany desk sitting right in front of it. On the desk lies a vintage typewriter in a beautiful cream color. You orient yourself in the comfortable chair and begin to think of what to write. You start with ‘hello.’ You continue on like a diary entry, detailing your name, the date, and what’s happened so far that’s been vaguely interesting. You do not mention the room. When you get to the end of the page, the ink starts to disappear and the typewriter resets itself. “How strange…” you think, before getting up and continuing on. You come to a part of the room where it’s noticeably warmer, and find yourself in front of a fireplace. There is a fluffy quilt set out, and a soft looking pillow. All of a sudden you find yourself overcome with sleepiness, and think to climb under the quilt and curl up on the floor. You feel safe, with the crackling fire and the smell of coffee, and as your eyes drift closed, you find yourself content. You are warm, and safe, and happy.

What more could one want?

My grandfather was tucked inside a couch cushion, folded inside Tuscan hills with only blueberries to eat. Nonna was a Christian who fell in love. Together they were two doctors who seeped through the tight gossip of florentine thread.

Opapa and Grandmama, Brooklyn and Farwackway, were both Black sheep who cut edge into their softly baked challah community. They connected on a retreat for young awkward adults looking for a match.

I wrote the typical rendition in freshman year. That Lyon poem in which I articulated my bookshelf and said everything as mentioned above. It was a mad lib then, as I described where I was from, making some earth-shattering connection between the triello in my living room and the rhythm in my voice.

How can we fully be what’s on our living room bookshelf

How can we be where we are from or merely the DNA attributed to us

How can we say we are fully what others gave to us

When our life is set on a much more personal stage

We exist and live in the forest frolicking amongst Hawthorne’s leaves and Shakespeare’s trees

I had this realization last year in the molded beige seat of a 307 chair

On a Thursday evening parallax air

I hate the idea of filling my prose with I am’s, Prickling with the past.

I know exactly where I’m from, Yet that’s not who I am entirely because you and I both have no idea where I’m going. You miss the shadow that followed me around in second grade, not the natural phenomenon but the person.

Falling into the vastness and infinity of a T.S. Eliot poem is proof that we are different from a rug of “I am’s” gifted by our relatives we describe in elementary poems. I transcend my double Ls, seep through Madrid, the place of my birth, and through the memories, my parents included me in all those years, even though I wasn’t born for them yet.

In truth, though, it is there.

So I guess it is as The Great Gatsby’s Nick Carraway re marked: we are “both within and without.”

I hate the idea of filling my prose with I am’s “

My mother tells me that I will grow into myself later in life. As that promise leaves her lips, I feel a dotted-line silhouette expand on the wall behind me. I look up and notice that it is vaguely me-shaped, save for its grand stature. As I gaze upon its blankness, I am transported back to a simpler time: a time when there weren’t enough shades of pink in the crayon box for my taste. A time when my teachers would scold me for leaving countless little white spaces on my page, and I would color more to please them, color until my hand cramped up. Even now as I look up at the massive, me-shaped space I have yet to fill, the nerves in my fingers ache with the urge to close the gaps. I begin with the hands. I fill the palms with ingenuity and ink stains, promises, and paper cuts. I leap up to the skull and split it in two, loading one half with sparklers and the other with storm clouds. I draw thunder ringing in my ears and fireworks filling my veins. I draw myself hazel eyes unafraid to look the world square in the face and to roll themselves in defiance. I draw myself the lips I inherited from my mother - full, slightly chapped, always prepared to cut someone down to size in between Aquaphor applications. I cover the space where my heart would be in all the shades of pink I wish to carry in my chest: soft rouge, bright bubblegum, flaming fuchsia. I take a step back, resolving to leave the me-shaped silhouette with gaping white gaps still present. I decide to let the world color me how it will.

On a hazy afternoon in late August, the last day before school started, I sat on the front steps, my bare feet on the hot concrete, the sun shone down and burned my shoulders. I turned to look behind me as I heard the squeak of the window opening, to see my mother stick her head out the open window, beads of sweat on her flushed face.

“Come inside, honey, it’s too hot out there!” she yelled.

“It’s hotter inside,” I said, “because you won’t turn on the air conditioner.”

She signed. “I only turn it on when we absolutely need it. I opened the windows,” she said.

“But it’s one hundred degrees,” I said, and I grabbed my hair–overgrown and blonde from weeks of sun–off of my neck and put it into a high ponytail.

“And tomorrow it might be one hundred and one degrees,” she said crossly.

“Whatever you say, mom.”

“Don’t speak to your mother like that.”

“Sorry.”

“Are you wearing sunscreen?”

“No.”

I watched through the window as she turned and walked through the living room, stopping at the couch to yell at my whining brother who sat watching TV and eating dry Cheerios out of a plastic cup. I grew bored and turned back around, stared at the empty road in front of me, and jumped when I heard a thud. I saw a bottle of sunscreen lying on the porch and my mother’s head back in the window.

“Reapply every hour, and be back inside for dinner,” she said.

I turned back around and smiled reluctantly.

“Thanks,” I said, and she walked back.

I looked down at the grass on the front lawn, which was yellow and dry. I looked up at the sky, which was completely cloudless. I looked ahead at the empty road. I sat like that for a while. I don’t know how long it was, but long enough that the sun started to go down. The sky turned shades of deep blue and light pink, and the heat had become slightly more bearable.

With the heat now less extreme, the street slowly came back to life as the neighbors went for their evening walks. Mrs. Blake came around the bend, walking her small white dog, who always growls at me. This time was no different. She tugged on the leash. “Stay back, Murphy,” she scolded the dog, who somehow seemed to glare back at her.

“Hello, Molly,” she said, nodding politely. “How was your summer?”

“It was good,” I said. “How was your summer?”

“It was lovely,” she said. “I just spent a week in Greece with my husband. Beautiful country.”

“That sounds very nice,” I told her.

“Thank you,” she said, tugging on Murphy’s leash, “What did you do this summer?”

I gestured around me. “This,” I admitted, grinning.

She sighed and shook her head. “Now, Molly, you are getting older. How old are you now? Thirteen?”

I had a feeling this was coming. I braced myself. “Sixteen,” I said.

“Sixteen!” she gasped. “You should be spending your summers more productively. At your age, I had a job.”

“Maybe next summer,” I said.

“Well, I must get home to make dinner,” she said.

“Murphy is hungry.”

“Okay,” I said. “Have a nice evening, Mrs. Blake.”

“Have a nice evening, Molly,” she said, “And tell your mother I say hi.” She walked away, Murphy grumbling behind her.

It was darker now. The crickets had started to chirp softly. I could feel my foot falling asleep, so I got up and walked to the tree on the front lawn. I bent down and carefully picked up a cicada shell. I looked at it in my hand for a moment, at the little details of its eyes and antennae and its hollow interior. I crushed the shell, and its remains fell to the grass below me.

I went back to my spot on the porch. I had started to absentmindedly pull out the grass

below the step when Mr. Jackson from down the street walked by with his cane. I called out to him when he was about ten feet away.

“Mr. Jackson!” I said.

He squinted. “Sharon?” he asked.

I had heard about Sharon. Apparently, she had been living in our house before we moved in and before I was born.

“No, Mr. Jackson! Sharon doesn’t live here anymore! It’s me, Molly!”

He walked a few steps closer and smiled when he recognized me.

“Of course! Silly me. How could I forget?”

“Well, I’ll best be getting home. Good night!”

“Goodnight!” I said, as he slowly walked away.

It was then that I considered going back inside since I supposed most people were having dinner, and because I didn’t want my mother coming back out to yell at me, but something told me to risk it and stay outside. There was silence, except for the now louder chirping of crickets, and the soft sounds of the wind whistling in the trees. The sun was almost down, but there was still a soft glow of light remaining. I realized that I was no longer hot.

Then, I heard the soft scraping of wheels on concrete, which I immediately recognized as Jake, my next-door neighbor, and classmate since the beginning of time. I had barely seen him this summer because he had spent most of it staying at his grandparents’ house. A few seconds later he appeared around the bend, his bright blue bicycle and shock of red hair making him unmissable in the dark.

“What are you doing out here, Molly? Does your mother know you’re outside in the dark?” he said with a playful smirk.

I smirked back. “Does your mother know you ride around without a helmet?”

He got off his bicycle and sat down next to me on the step.

“Tomorrow is the first day of school,” he said.

“I know.”

“Have you done the summer homework?”

“I did it on the last day of school.”

“Well, that was smart.”

I rolled my eyes. “No, it wasn’t. I forgot everything I read.”

“Oh.”

“Have you done it?”

“Not yet.”

I raised my eyebrows. “Really?”

He started laughing. “I also did it on the first day of summer.”

“I knew it. I would never buy you as a rebel,” I said.

“Did you do anything interesting this summer?” he asked.

“No.”

“Neither did I.”

“Oh.”

He smirked like that again. “Am I annoying you?”

I smiled. “Only a little.”

“Apologies.”

“Don’t worry, I forgive you.”

Then, I heard my mother call from inside the house, “What are you doing out there, Molly? It’s been three hours! Come back inside!”

“Give me five minutes!” I called. I turned to Jake. “I should probably go inside.”

“Yeah,” he said, “you probably should.” He got up to leave. “I’ll save you a seat next to me in math,” he said.

“Why? So you can copy off of me?”

“Exactly.”

“I’ll see you tomorrow, Jake.”

“See you tomorrow, Molly. Goodbye.” He got back on his bike and rode away.

I looked up and the sky was black, the stars had come out, the heat was gone, and the summer was over, so I stood up and went inside.

My first heartbreak happened as I slid the Bananagrams squares off the living room table in a tantrum. I was in third grade then and had just lost for the fourth Saturday in a row. More than just the wound to my ego, the camaraderie I had with my mom during the momentum of the game was stripped from me. She’d connected her last square to transform the word sin to sing, and suddenly we were not in something together.

Charlotte Newhouse

Charlotte Newhouse

My sister talks of the sassy Lunch ladies

And my cousins lose interest.

It’s been 10 minutes since I’ve been asked a Question,

But I don’t mind because they are all About college anyway.

Then I get a new one. Do you know how to drive?

I say no,

And my cousin emphatically celebrates. That’s one point for him

And none for me.

Unsure how to react,

I stare down at my pumpkin soup

And notice that it has curdled.

At this point, I’ve had 3 rolls,

But I begin to pull another apart.

As Sarah Leah talks about teaching Shemos in Monsey,

I wonder if she’s qualified. She looks young.

I study her face as she talks about the Pyramids of Giza, And notice a sheen of foundation. I wonder if the redness

Around my eyes

Has subdued.

I slide my phone out

From underneath my leg

And open up photos. Grandma catches me

In this moment of indulgence, And squeezes me tightly anyway.

For me, going to synagogue has always meant sitting in the large sanctuary with its soaring ceiling and stained-glass windows. It meant listening intently to the weekly sermon and worshiping in an environment of grandeur, magnificence, and formality.

The summer of 2020 offered another perspective. I was in Upstate New York staying at my grandparents’ house. We had been there for a few weeks, fortunate to have the opportunity to spend time with loved ones while the pandemic was at its height. Our long days were filled with the typical activities of a summer in the countryside, and while there was certainly a serenity to being away, the uncertainty, anxiety, and fear about the world at large clouded our daily lives even as we settled into a comfortable routine.

As my family and I sat down to eat dinner one night, the phone rang. Usually, we would just let the call go to voicemail and listen to the message after the meal, and, more often than not, the caller was a telemarketer we could ignore. But this time there was no message, and the phone rang again. Someone needed to reach us, so my grandmother walked to the phone and answered it. We were all curious and watched her as she held the receiver to her ear. She listened mostly and at one point replied with a definitive, “Absolutely.” Though we were able to pick up on a few words on the other end, nothing gave away any clues as to who was speaking or what was being discussed. My grandmother hung up after a few minutes and turned to my parents and me: “That was the Rabbi who lives down the block. He called to let me know that he is holding a service in his backyard so that one of his congregants can say the mourner’s kaddish [a memorial prayer] on the occasion of his father’s yahrzeit [the anniversary of a relative’s death]. He wanted to ask me if you would be kind enough to come and make the minyan [the minimum number of people required to say certain prayers]. I hope you don’t mind that I said yes for you.”

My first thought was to wonder why my grandmother ever thought we would mind, but there was almost no conversation and even less time to get ready. Within five minutes, my parents and I began to head out. My grandfather would have come with us in the past. These days he is not well, and we knew that the Rabbi

would understand his absence. We stepped out onto the street and began to walk down the block to the Rabbi’s house. It was dusk and the sun was setting in the sky. I watched across the street as a neighbor rode her bike into her driveway and as some little children played in the grass in front of their house. It didn’t feel as if we were going to synagogue. But soon enough, we walked past the front of the Rabbi’s two-story house and looked around to the side where we noticed a group gathered in the backyard. My parents and I made our way to the yard and realized that the service was going to be conducted right there: in the mild early-evening warmth, amid the grass and trees, on folding chairs. I had been to services outside before, but this was different. It wasn’t summer camp by the lake with swarms of kids jumping with energy, nor was it a fancy Bar Mitzvah with carefully curated flower arrangements. It felt authentic – a service conducted right then and there in the middle of day-today life, and at a time when the ability to come together as a community was not to be taken for granted.

The Rabbi waved from his porch, his face covered by a mask. We said our hellos and helped set up some more folding chairs. As a few more people arrived, the service began. We opened our prayer books, and the pages flipped slowly as a breeze passed through the yard. The rickety chairs teetered on the uneven terrain of grass and dirt, and it began to darken outside while the insects’ chirping intensified slowly. Though the setting was different, it was comforting to say the same prayers as always and to bow at the same times. Soon it was time for the mourners’ kaddish. The age-old Aramaic words permeated the air around us. I wondered if the blades of grass we were sitting on had ever heard the kaddish before, or any of the prayers. My reverie was broken as the service concluded. We weren’t sure exactly what to do, but we folded up our chairs, gathered our prayer books, and brought them back to the terrace. The books were placed in a neat pile next to a grill and there were some extra prayer shawls placed on top of a patio chair. We said quick goodbyes to the group and started our short walk home. I realized it was the first time I had ever walked on that street, in all my years of going to my grandparents’ house, in complete darkness.

You were bent back over the balcony with strings of gold falling from you; falling from you and almost— but never— reaching the concrete beneath. The diamonds on your neck dripped past you, looping as a crescent by your nape. Swans circled down the Seine behind you, and when they spread their wings, you became an angel. The moon sunk into your champagne flute as you put it beside the twinkling tower. And everything then was gold against gold— a thousand little candle lights scattered across a city.

“ And everything then was gold against gold—a thousand little candle lights scattered across a city.

The sun has set, The moon is nigh, Here comes the night

In the star sprinkled sky

Children tucked in, With a kiss on the head, A whispered “good night” To the little one in bed

Crickets are chirping, The adults snore, The TV is still on, But what’s on is a bore

The moon watches over Little critters of night, Keeps them safe while they scurry To their hearts’ delight

The birds take their rest

In their quaint pine trees, And everything is just As it is meant to be.

An oblivion of untenable exposure, Of my depths unraveling, leaving a chaotic abyss — Where too much everything feels like nothing —

And I am falling into myself, withdrawing Corporeally, psychologically — engulfed

By panic, tears, and nakedness That drive my need for secluded silence,

For the quiet intimacy that begets candor.

“

And I am falling into myself, withdrawing

I went to Sarah’s house with my family one night for dinner. One of Sarah’s friends came too. Sarah’s friend was breathtakingly beautiful. Pri was her name. Pri had wavy, slightly frizzy blonde hair, which made her look as if she’d come straight from the beach. A thin sundress revealed her long skinny legs, and her blue eyes made me wish that I went to a non-Jewish school. I felt exposed when she glanced at me, as if she saw right through my soul.

Dinner was delicious, but I couldn’t eat much with Pri sitting just across from me. Am I an ugly eater? I kept thinking. Not worth the risk. Sarah and Pri were talking a lot, and I would chime in with some short remark every now and then. The adults spoke about Trump and Biden and how nothing is normal these days. I was bored by that because it’s always the same. Sarah and Pri spoke extensively about how Sarah had just landed in the Lacoste catalog. I didn’t care much about that either. Why did Sarah need to put on a charade even in front of one of her closest friends?

I was in love with Pri midway through the first course. She seemed genuinely happy for Sarah, without any hint of jealousy or resentment. I respected her for that. After about an hour of the adults discussing, Pri’s mom addressed me.

“It’s nice to meet you, young man. What is your name?”

She was just a regular woman, yet for some reason I couldn’t seem to find my voice. I wanted to say something witty and mature even though she had simply asked for my name. Eventually, I built the courage to respond.

“I’m… I’m Harrison. It’s nice to meet you.”

“How are you enjoying Westhampton, darling?” she inquired.

“It’s awesome,” I replied. “I love the Hamptons.”

“You mean Westhampton. Westhampton isn’t authentically The Hamptons. The Hamptons only truly start in Southampton. But yes… Westhampton is quite nice, I suppose.”

What is this pretentious woman talking about?

It’s literally called West-Hampton, so how the hell is it not in the Hamptons? All I could respond with was, “Oh, I didn’t know that. That’s interesting.”

“Your parents tell me that there are always disturbing, very loud parties next door to you guys. Have you attended any yourself?”

Suddenly Pri interjected.

“You live next door to Luke Silver?” My cousin Sarah bit her lip and looked down at the table timidly when Pri said the name.

“Well,” I said. “I don’t know the name of the host. But yes, there have been a couple of huge parties next door to us. I haven’t gone to any because I don’t really know anyone there, and I have never been invited.”

Pri laughed.

“People aren’t invited to Luke Silver’s parties; they just go. I’ve been to a few myself,” she said, as if it sounded impressive. “They are crazy; I will say that.”

“Well, maybe I’ll go to the next one,” I said.

When we were all leaving the house later that night, I said goodbye to Pri, while blushing profusely. She told me that maybe we’d see each other at one of Luke’s parties. I told her that I hoped so.

He didn’t see me, but I was there — watching as he dragged the garbage bag across the wet concrete, up the stairs, and into his Fifth Avenue brownstone. He didn’t see me when he flicked on the light in his living room, which shone through a large window, causing a plot of rain-soaked sidewalk to glow a faux shade of sunshine yellow amidst the gray night. Nor did he see me when he looked out said window and eyed the black streets while somehow continuing to maintain that gens du monde attitude that he so often carried himself with — the way his arms extended overhead to grip the top of the window frame, how his pressed suit remained in perfect condition despite the damp, the manner in which his lips were pursed ever so slightly so that his visage remained enigmatic. He then turned with that same sense of grace and took the red plastic strings on the garbage bag once again and dragged it through a hallway until he disappeared into its shadows. I stood there, listening to droplets fall from red leaves and onto the nylon of my raincoat, until he came back to shut the light. For that sole brief moment, when he wasn’t there, I finally felt truly alone.

I tucked my hair under the back of my coat and pulled the hood taut around my head. The rain fell hard. And although the skies grew exponentially murkier, I could still see the glow of a Cheshire smile hidden beneath the clouds.

It was already the end of the latest hour when I started home. I walked past those leaving what appeared to be a black-tie event held at the Metropolitan Museum. Women with silks and black umbrellas and mink furs kissed their partners, or nestled their heads in the crevices of their necks.

With their manicured hands they held their Parisian purses and whispered to one another — the heat of their breath transforming into a visible vapor as it escaped their red lips; all the while their partners checked their watches or spoke, most likely, a forced business talk with one another. An ashy residue on the sidewalk marked where the crepe cart had stood earlier that day and where it would be on the next; but slowly it disintegrated beneath the storm.

I walked past the sleeping buildings and those that remained awake. And from an open window, a Bon Iver song played like a fleeting memory. I walked past the nocturnal dog walkers, the sort who allow their Great Danes (or even their Malteses) to dictate where they go and when they go. I walked past the Madison shop windows displaying mannequins porcelain white and naked — an omen of the season change. I walked past a bar where the day begins at night; and if Manhattan had roosters the night would only end when they sounded their morning call. Last and certainly least, I walked past the rows of empty or wilted flower beds leading up to my house, a place where I could no longer exist through the lives of others.

“

Last and certainly least, I walked past the rows of empty or wilted flower beds leading up to my house, a place where I could no longer exist through the lives of others.

ink drips from my lips, midnight in complexion. it overflows my body, running through my veins, sinking into my thoughts. words swim across my vision like darkened skies until they are all i can think about.

words and ink, what a beautiful way to bleed.

Swords clash in the mountain wind

Flurries hail from afar in a sudden din

Lightning flashes across the once clear skies

The truth tells me that this will be my demise

Hungering away and bearing streaks of pain

Screaming and shouting worlds away

I tried to be evil’s bane

But now bloody and doomed here I lay

No more than a remnant of a long-ago day

Before the darkness, I get up to fight

Hurling all of my remaining might

Tears unshed now flow away

Regret and guilt now rule the day

With my enemy’s blood on my hands

I can die peacefully and dream of faraway lands

Lands where people don’t slay each other

Lands where people love each other

Lands where peace roams on sunny hills

Where people don’t just live for the kill

With a tear and a smile, I exhale my final breath

The world goes dark

But in darkness, I grow light

As I step onto the slimy rocks that align themselves along the boundless sea, I become minuscule. The booming sound of the waves pounds against the boulders while cold water splashes my face. I was told there would be a powerful, rough current today, but that didn’t stop me from letting the wind tangle my curly brown hair into one big knot. I begin to soak up the view. As I look up at the sky, salt water stinging my eyes, I notice that I’m just in time to see the sun begin to shift in size. Developing into the shape of a ripe, shriveling lemon, all while sinking into the earth, the sun becomes smaller. It has begun harmonizing with the hue of salmon, the pale blue mirage of the sea, and the taste of a juicy, fresh orange tingling on your tongue. Each spark of color its own unique melody.

I wake up and realize that my eyeballs are gone. Where could they be? It's annoying because I've always thought my eyeballs and I had a good and healthy relationship. Now I know that it was just one-sided. If I had eyes, it would be much easier to find my eyes, but alas, I do not. I guess all I can do now is go and look for them; I will not live life without my eyes. The first place where I think they may be is the beach. My eyes love seeing beautiful girls, the wavy ocean, and the golden sand.

I leave my apartment and use the wall to guide me through the hallway. I know I am in the lobby when I hear a shrieking scream.

"That man has no eyeballs!"

I get offended. "Relax, woman."

I ask the building doorman to take my phone and order an Uber. I would tell you about the drive, but some stories are only interesting with imagery. Finally, I arrive at the beach, where I follow the sound of people's voices to ask if anyone has seen a pair of hazel eyes. Most people scream, horrified, but I try not to let it get to me. Someone approaches.

"Excuse me?"

Irritated, I ask what he wants because it has been a terrible day, and I'm not in the mood for more problems.

"No," the man says. "It's just that I saw your eyes; they were here earlier. They were admiring the beauty and seemed truly at peace. Eventually, one of them said, 'Alright, Mclovin, it's time to go.' When I asked them where a pair of eyes had to go so urgently, they replied, 'It's time for us.'"

I cut the kind man off. "My eyes are about to kill themselves! I gotta help them!"

For the longest time, I haven’t understood why my eyes seem to force me toward the edge whenever I drive across the bridge. Now

I know what it has meant all along. I ask the man to call me an Uber to get to the bridge. He tells me that the bridge isn’t enough of an address. I ask him to order it anywhere.

I urge the driver to go faster. “If you see a pair of eyes, tell me!” I yell, panic rising.

He laughs like I’m an idiot. A couple of minutes go by, and the driver gasps. “Oh my god,” he says. “There are literally just two eyes on the edge of the bridge.”

"Drive me to them," I say pressingly.

"Okay, we are right in front of them," he says. I rush out of the car.

"My eyes, my precious, beautiful eyes. Come back to me."

The eyes answer in unison. "Everything has become horrible. We must go around with you daily, watching firsthand as the world crumbles. The planet is dying, and we don't want to be here when it does. We can't stand it any longer."

I respond, careful not to spark any impulse. "Look," I say. "I need you guys. My life would be pointless without you. I love you both so much. I don't think I could go on without either of you. Please."

There is silence, and I feel my eyes climbing up my jeans. They lie in my hands, and I place them softly back into my sockets. Tears are streaming down my face. As I look around, I feel deep sadness.

"You guys are right. The world is completely falling apart. I guess I just never saw what was right in front of me."

With tears still spilling from my brilliant eyes, I say, “We all go together.” We jump, liberated.

AlissaI study the cracks and chasms along her brilliant face

And when she flashes a smile

She reveals her teeth

No longer straight, nearly sharpened

The creases in her crow's feet pronounce themselves

But somehow she’s young again

And I remember she’s human

When she tells me she’s glad I’m here

Her eyes begin to glaze over

But I tell myself they

Are beady in nature

And when water rolls down her cheeks

I tell myself that it’s just from the splash

Of her morning routine

I convince myself that

It’s insincere

That I come around enough

And that she’s crying crocodile tears

Leaves of fire

From sap-filled forearms

Reaching to embrace the misty air

Their flames do not spread

My gaze breaks from the autumn tree

Pealing bells in the morning

Stained glass in the afternoon

Embers return in the night

Fluttering to the frostbitten ground

I crush them beneath my fledgling feet

They chip like china

This is what God must feel

It is a futile thought

For I am just a girl

And there is pavement beneath me

And God doesn’t feel

Trees to pages, pages to words

Words to thought

Thought to action

Actions built the church

And the church is trees

Rain grew the trees

Had God been weeping?

“For you are dust

And to dust, you shall return”

Imbued in every one of His creations

Fires and girls and churches

I said I would burn the world for you, so you handed me a match.

I didn’t know what I should do, and the flame started to catch.

I felt the fire singe me, and so I dropped the flame.

Now the world is burning, and you’re the one to blame.

Alissa Rose

After sunset, a darker, ghostlike version of myself settles into my skin. “Meet me at midnight,” she says, and already I am preparing for the worst. By nightfall I feel myself becoming her – a mist created from rapid gusts of hysteria and hyperventilation. Craving an escape, I leave my mortal body behind and retreat into the areas of my mind that the sunlight keeps at bay.

I arrive first at the grand altar. I summon the spirits of all my closest friends into the room, cursing their names one by one while simultaneously mourning their wounds bleeding before me, praying feverishly for them to heal. I expel them and, with blood still staining my shirt, I vanish.

At the witching hour, I travel again to the town of Salem to burn myself at the stake. As she cries out, I feel my own flesh being scorched, skin and bone seared by the hot blaze of contrition. Taking pity on us both, I kiss her forehead with a grin that holds a subtle type of magic, a blasphemy not to be named or erased.

I take to the night skies, searching for the dark side of the moon. When I find it, I land my aching spirit in one of its craters and release guttural screams and sobs into the wide expanse of space. I am only finished once I scream loud enough to make the gleaming star in front of me explode into a cloud of galactic dust and debris. Unafraid of the damage, I tuck the iridescent shards into my pocket and let myself fall back down to earth.

In a flash, I am brought back into my skin as the sound of twilight rustling reminds me of my own body. I reach into my hands like gloves and step into my feet like broken-in shoes. I listen closer, hearing my mother’s footsteps in the kitchen, her coffee brewing and bubbling in the machine. The sounds are soft, almost inaudible over the noise of the night I have had. Yet they remind me that I was born and made from midnight rain, with thunder in my throat and lightning at my fingertips, that the storm inside me is both my curse and my greatest gift to bear. At that revelation, I do not go to sleep. Instead, I lie awake, waiting to break the dawn myself and harvest all the golden hour hope bleeding into the sky.

The other day I walked up to a group of girls and asked “how’s your day?”

They said “ewww, go away, you're not timmy chalamet”

I told them to lower their expectations because they weren't

Lily Rose

After an hour of persuasion, they were like “yeah, I suppose”

So one agreed to let me take her out

You won't believe what came about

We went to a club downtown

I ordered us a round

And who walks through the door but timmy-tim himself

No longer at eye level with my date, it was like I was an elf

The glow in her eyes made me want to walk into the ocean

I couldn’t understand why this skinny kid was causing such a commotion

An imbalance in human behavior

Like the messiah in our midst: oh my lord and savior

The rest of the night my date tried to get into vip section

To pursue her dreaming misconception.

My Dearest Light, I have heard what the earthlings have said about me. To them, I am no longer a planet in your solar system – just a hunk of rock too small to be worth any other title. I know how this disturbs you as I have sensed an unusual apprehensiveness in your rays of late. You worry that I may be too small for you to hold onto much longer – that your gravity will not be enough to bridge the gap of light years and that I will float away from you. Fear not, my ultraviolet star, for you have a hold on me in the truest sense. In the cold, uncertain expanse of space, it is your warmth that I always reach for, your undeniable orbit that keeps me steady. Earth turned its back on me before I could even circle you fully, but that did not keep me from continuing to revolve around you. How could I have stopped? I would have been mad to pass up the opportunity to observe your heavenly body from every angle. And yes, I know I am small. Compared to the likes of Jupiter, with its flashy red jewel, I am nothing but a mere asteroid needlessly speeding through space, completely inconsequential. This may be true, but the love that aches in my core for you is big enough to swallow you entirely. It is a black hole, a gravitational pull of my own that sucks you in and holds you just as I long to do. This is why – my love, my everlasting flame – you need not feel afraid. As long as you are not swayed by Saturn’s rings or Mars’ sensual red shade, I will keep to our celestial bond. I will let you pull me in as close as you wish, even if I burn – for thoughts of you are already the flames that engulf my soul. Let the earthlings call me what they will. Let them name me illegitimate, name me dwarf. I do not vie for their approval. Your radiating heat, your light –indeed, your love – is all I need to feel big.

Forever yours, Pluto

And I am falling into myself

Josh Chetrit

Josh Chetrit

Parallax n. fr. Gk parallaxis, the apparent displacement of an object due to a change in the position of the observer.

Parallax n. fr. Gk parallaxis, the apparent displacement of an object due to a change in the position of the observer.